- 1LE@D, Universidade Aberta, Lisbon, Portugal

- 2CIES, ISCTE, University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

- 3Atlântica, University Institute, Oeiras, Portugal

- 4CIEd, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

- 5CIPEM-INET-Md, Escola Superior de Educação do Porto, Porto, Portugal

Introduction: UNESCO has sparked interest in the study of happy schools and, through its Happy Schools Project (HSP) framework, provides tools that enable the teaching and learning community to work towards making “happy schools” a reality. Since the understanding of happiness is culturally influenced (HSP studied Asian countries), we sought to identify parallels between the HSP framework and Portuguese schools through the eyes of students.

Methods: We asked a group of Portuguese students to rate their happiness at school and answer three open questions: What makes you happy at school? What makes you unhappy at school? What is a happy school? Using an online survey, 2708 students participated in this study. We coded the answers with variables derived from the HSP framework, aiming to understand what characteristics students value most when referring to their happiness or unhappiness at school and what features a happy school should have.

Results: Findings show that most Portuguese students consider themselves to be reasonably happy. No relevant difference exists between boys’ and girls’ self-reported happiness levels, and their happiness decreases as age increases. Children emphasized relationships with friends and teachers and teachers’ attitudes, competencies, and capacities as elements of a happy school. We found that school unhappiness is related to excessive workload and bullying.

Discussion: Even though there are cultural differences between countries, when we identified the characteristics of a happy school from the perspective of Portuguese students, we found similarities with the HSP framework guidelines.

1. Introduction

The study of school happiness has gained momentum driven by UNESCO guidelines that foster peace through education and fundamental pillars of learning such as learning to live together and learning to be. These guidelines include qualities based on relationships, including empathy, tolerance, respect for diversity, communication, and teamwork (UNESCO, 2014, 2016).

Indeed, happiness is one of the aspects that the OECD studies consider by analyzing subjective well-being (OECD, 2021), a term associated with happiness (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Alexander et al., 2021). Despite this association, it is not agreed upon that the two terms reflect the same thing, as well-being could be interpreted as “a conglomerate of many aspects of life and one’s physical and mental being, while happiness [is] more mental and more fleeting” (Jongbloed and Andres, 2015).

Interest in happiness has increased significantly in the last decade (Dantas, 2018). Its importance led to the World Happiness Report (Helliwell et al., 2012), which described the state of happiness worldwide, the causes of happiness and misery, and the political implications highlighted by case studies. According to the report, happiness differs from society to society, and over time, for identifiable reasons, and can even be alterable through public policies. Concerning adults, professionals’ and companies’ happiness has been studied (e.g., Dutschke, 2013), with conclusions indicating that the organizational environment influences workers’ performance. These studies identified the dimensions and variables contributing to individuals’ organizational happiness, informing the design of the Job Design Happiness Scale (Dutschke et al., 2019). This scale makes it possible to identify workers’ happiness levels and what makes them happy in the company where they are employed. Because teachers are also workers, the organizational happiness of teachers in Portugal was studied (Gramaxo, 2013), with the conclusions indicating that they are happier in their job than in the organization where they work, and that they are happy because of the students and the way they do their job. They are also happy because they achieve their goals and have autonomy and responsibility, and because they can be creative and enterprising, which are important aspects of organizational happiness. On the other hand, they are unhappy because they do not share the vision of the organization, and because there is no job rotation; having little time to share opinions and make decisions and being underpaid also makes them unhappy, as does the existence of too much bureaucracy. Colleagues can be a cause of happiness, but also of unhappiness (Gramaxo, 2013).

Regarding children, what contributes to their happiness is a set of different dimensions, as found in the literature: health, family, friends, and school (Giacomoni and Hutz, 2008; Holder and Coleman, 2009; Lavalle et al., 2012; Giacomoni et al., 2014; Badri et al., 2018; Mínguez, 2020; Gómez-Baya et al., 2021). When constructing and validating a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children, Giacomoni and Hutz (2008) found that family, friends, school, and non-violence were dimensions that should be integrated into a scale measuring children’s life satisfaction.

Health-protective behaviors such as participation in sports, eating fruit and vegetables, and not smoking were associated with happiness in adolescents (Booker et al., 2014). In line with this finding are those reported by a Portuguese study of adolescents, which found that 25% of happiness is explained by practicing healthy behaviors (sports and good nutrition) (Ferreira, 2018).

Regarding family, the amount of fun they have with their family, how family members get along, and how much time parents spend with their children impacts children’s happiness (Badri et al., 2018). Adolescents’ perceptions about the involvement and support they receive from their parents are associated with their performance and well-being (OECD, 2017b).

School is also crucial to children’s happiness (Giacomoni and Hutz, 2008; Badri et al., 2018; Gómez-Baya et al., 2021). Children are happy at school because of their classroom colleagues, the things they learn, and their relationships with teachers; inversely, bullying is significantly negatively associated with happiness at school (Aunampai et al., 2022). Positive (or unfavorable) social interactions with friends explain variance in children’s happiness (Holder and Coleman, 2009; O'Rourke and Cooper, 2010; Ince et al., 2022). Children spend most of their time at school; therefore, studying what makes children happy at school and what makes a school happy is relevant to inform policy and practice.

The individual gains of education are transposed into better and better-paid jobs, work, skills valuation, personal independence and social relations, reduced risk of unemployment, and increased well-being. Learning acquired at school also generate better decisions on a health level, encourage civic participation, and reduce the probability of developing risky or delinquent behaviors (Oreopoulos and Salvanes, 2011).

Schooling is vital because it prepares students for life both in the labor market and at a personal level; those who spend more years in school tend to be happier than those who spend less time there (Veenhoven, 2012). A synergy exists between happiness and learning (Seligman et al., 2009). Happy students achieve more (Gilman and Huebner, 2006; OECD, 2017a; Ferreira, 2018), so happiness should be one of the goals of education, and a good education should contribute significantly to personal and collective happiness (Noddings, 2003).

1.1. Studying happiness at the school level

The school became an object of study despite a trend of study advocating “schools do not matter” (Coleman et al., 1966), which assigned successful learning to the socioeconomic context. We follow the trend clarifying that “school makes a difference” (Bolívar, 2012). But how? From the seventies onwards, several researchers aimed to study “school effectiveness.” The characteristics of an “effective school” started to be analyzed to investigate the school-related facts that directly or indirectly explain students’ results (Bolívar, 2012). To sum up the main conclusions of what contributes to an effective school, the research uncovered: strong leadership, an orderly and conducive environment for learning, an emphasis and focus on learning, high expectations for students, student performance monitoring, student success valuing, shared goals and values, and parent involvement (Gaziel, 1997; Engels et al., 2008; Dumay, 2009). Socioeconomic background and family structure have also been identified as determinants of successful learning (Björklund and Salvanes, 2010; Parey et al., 2013).

Another perspective is anchored in “school climate,” which identifies the social, emotional, ethical, academic, and environmental dimensions of school life (Cohen and Michelli, 2009). This area of study underlines the importance of affective and cognitive perceptions regarding social interactions, relationships, values, and beliefs held by students, teachers, administrators, and staff within a school (Rudasill et al., 2018), while concurrently guaranteeing safety in a social and physical sense (Zullig et al., 2010). This school climate approach is associated with happy schools (Talebzadeh and Samkan, 2011; Huebner et al., 2014).

We stand before a critical paradigm driven by UNESCO’s study of a happy school (UNESCO, 2016). Creating school rankings from a simplistic analysis of best or worst results is an ineffective way to analyze education. Instead, we should add more complex layers from the understanding of happiness characterized by how each individual feels at school, and how school organizations can improve individual happiness levels. The decision maker should focus on more than pressure, academic results, tests, and competition. Areas such as the joy in learning, friendships and relationships, a sense of belonging, and recognizing the relevance of values should be strengthened, as they help enhance happiness and well-being.

Regarding children’s perspectives, López-Pérez and Fernández-Castilla (2018) found that from children’s point of view, happiness at school means having free time, helping and being helped in their difficulties, being with their friends, and being praised. López-Pérez et al. (2022) compared English and Spanish pupils’ views on happiness at school and found that English children defined happiness at school as experiencing autonomy, non-violence, and having a positive relationship with teachers, while Spanish children privileged harmony and having leisure time. Finally, compared to boys, girls mentioned emotional support, positive relationships with teachers, and experiencing competence more frequently in their definitions of happiness.

For children to feel happy at school, they must spend time with their friends, have fun, have self-esteem, and feel safe. On the other hand, tiredness, confusion, nervousness (Mertoğlu, 2020), and bullying contribute to their unhappiness (Calp, 2020; Mínguez, 2020; Aunampai et al., 2022).

1.2. A happy school

All students appreciate a school environment where bullying is rare, making friends is relatively easy, and establishing genuine and respectful relationships with teachers is the norm (OECD, 2019). A happy school is one where management, teachers, and students are open to innovation; students learn content necessary for life, and acquire self-related skills; students highly value teachers because they are knowledgeable, attentive, helpful, sufficiently demanding, and able to explain their subject well (Kuurme and Heinla, 2020). A happy school is also a school where students, teachers, administrators, and staff feel happy (Calp, 2020), and one that offers students a happy learning environment, enabling them to feel happy and excited about going to school and learning from their teachers (Giản et al., 2021).

Other variables associated with a happy school are: praising students for their success and progress; active teaching methods; group thinking and work; teacher happiness and interaction with students; course content; training facilities; and school organizational climate (Talebzadeh and Samkan, 2011). By promoting a favorable climate, schools can ensure more equality in educational opportunities, diminish socioeconomic inequalities, and enable social mobility (Berkowitz et al., 2017). Understanding what makes children happy at school might be relevant to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 - Quality of Education as defined by the United Nations Resolution 2022. This goal aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education, and promote lifelong opportunities for all. However, there are gaps in terms of what socioeconomic background is concerned; therefore, to improve the performance of all students, countries must become high-performers and achieve SDG 4 and its targets (OECD, 2017a).

1.3. Happy school framework

The goal of a happy school is to improve learning experiences. Seeking to achieve this goal, UNESCO (2016) conducted a study named the Happy School Project (HSP). The authors reviewed the literature on happiness and well-being and gathered data through an online survey of students attending private and public schools and adults with responsibilities or who work in those schools: students, teachers, school support staff, parents, the general public, and school principals. The findings allowed for the design of a framework that considers three dimensions contributing to a happy school: people (referring to social relationships), process (referring to teaching and learning methods), and place (referring to contextual factors).

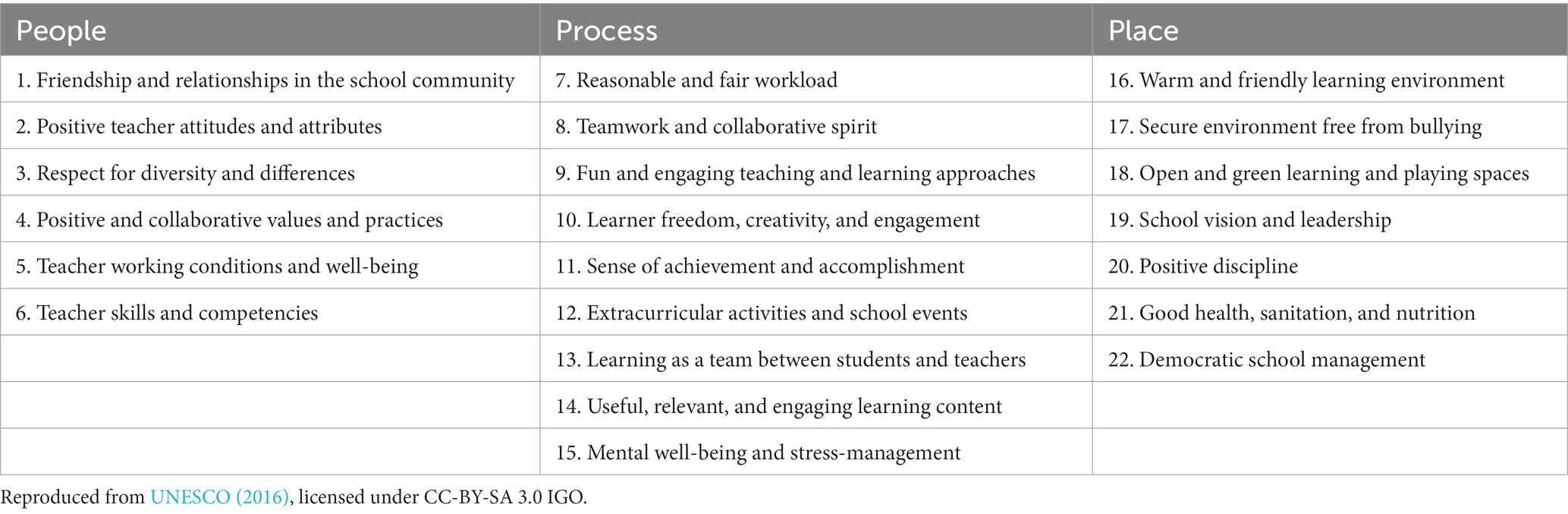

According to the project, these dimensions rely on 22 variables (Table 1).

These findings are consistent with those of other studies: one claims that the dimensions contributing to a happy school are (1) individual, (2) social/emotional (people), (3) instructional (process), and (4) physical (place) (Talebzadeh and Samkan, 2011). Another revealed that the dimensions contributing to school environment are (1) quality of interactions with teachers and peers (people), (2) instructional practices in the classroom and students’ perceived and actual academic performance, as well as opportunities to participate in extracurricular activities (process), (3) students’ perceptions of safety (place), and (4) parental involvement in schooling (Huebner et al., 2014). Another study, conducted by the Philippines Department of Education in 2021 (integrated into the national project Happy Schools Movement), focused on three interrelated dimensions: (1) relationship, (2) teaching-learning experiences, and (3) physical environment and atmosphere, similar to the HSP framework. We can conclude that aspects such as the relationships between people, the processes through which teaching/learning takes place, and the spaces where learning takes place together, are the basis of a happy school.

1.4. An unhappy school

The HSP framework study (UNESCO, 2016) clarifies what makes students unhappy at school: (1) an unsafe environment prone to bullying, (2) high student workload and stress provoked by exams and grades, (3) a hostile environment and school atmosphere, (4) negative teacher attitudes and attributes, and (5) bad relationships.

Characterizing the variables associated with happy and unhappy schools informs policymakers about measures to be implemented or avoided to reduce unhappiness and adverse feelings.

1.5. Objectives

HSP was developed mainly in Asian countries, which are culturally very different from the Portuguese reality. There can be cultural differences involved in determining what is valued for a happy school. Our global objective is to understand the concept of a happy school from the Portuguese students’ perspective. We have already studied the concept from the parents’ perspective (Gramaxo et al., 2023). Our goal with this present study was to uncover Portuguese students´ perspectives concerning a happy school. The following research questions were investigated:

1. What is the level of happiness at school reported by students? Are there differences according to age and gender?

2. What makes Portuguese students happy at school?

3. What makes Portuguese students unhappy at school?

4. What are the characteristics of a happy school from the perspective of Portuguese students?

2. Materials and methods

We have conducted a descriptive and correlational exploratory study, given the absence of previous studies about happy schools in Portugal. We have first proceeded with a qualitative approach through content analysis of the questionnaires, aiming to categorize and quantify the concepts and items identified. Then, with the finding data, we proceeded with a quantitative analysis. The questionnaire was first sent to school directors for their approval. After that, the questionnaire was formally disseminated by the school, involving the directors, teachers, and parents. Parents and students were informed about the study’s objectives and that data would be used only for research purposes. Their collaboration was voluntary, and they could drop out of the study at any time. The questionnaires were anonymous. Ethical concerns were, therefore, present in the research process (AERA 2011). Ethical and methodological review and authorization to apply this questionnaire in the school context were obtained from the Portuguese General Directorate of Education (protocol number 0694400004) and the Ethics Committee of the Laboratory of Distance Learning and eLearning (CE-Doc. 23–03).

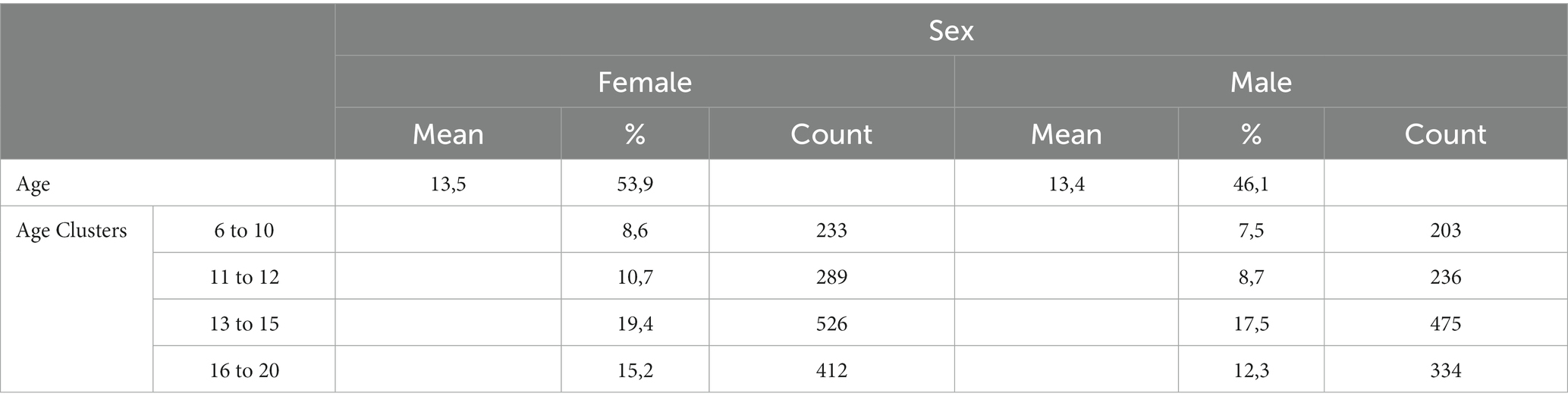

We collected 2,858 responses. Among these, 2,708 responses were validated (94,7%), while 150 participants were excluded from the research because their forms were incomplete. In the study reported in this paper, the sample consisted of 2,708 Portuguese students (1,460 girls and 1,248 boys), aged between 6 and 20 years old, attending 32 public schools concentrated in the central region of Portugal, but representing a variety of contexts. All the students were enrolled in mandatory education.

We have segmented the students’ ages into clusters, corresponding to the expected ages for each of the cycles and levels of education: 6–10 (First Cycle of Basic Education), 11–12 (Second Cycle of Basic Education), 13–15 (Third Cycle of Basic Education), and 16-above (Secondary Education). The resulting characterization of the participants, according to their age and gender, is presented in Table 2.

Students were asked to rate their happiness at school on a Likert scale from 1 (very unhappy) to 5 (very happy). They also answered three open questions: (a) What makes you happy at school? (b) What makes you unhappy at school? (c) What are the characteristics of a happy school? The questionnaire was filled out online and is presented in Appendix A.

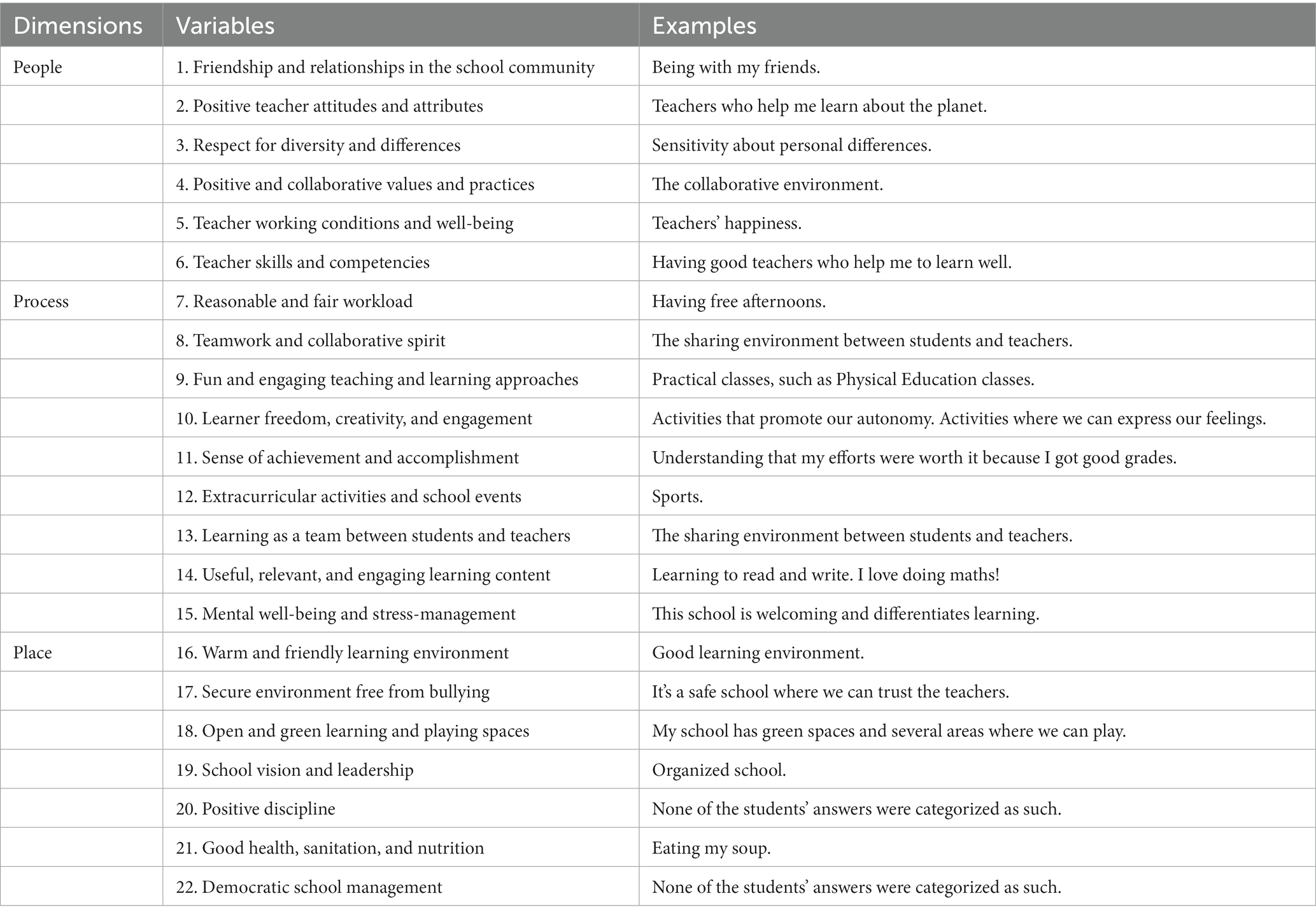

The resulting data were primarily qualitative. For the answers on happiness (personal and school level), an a priori category scheme was constructed based on the 22 variables of the HSP framework (Mayring, 2014; UNESCO, 2016; Gizzi and Rädiker, 2021). The response regarding what makes students unhappy was coded according to five variables: Too many classes, Bullying, Negative attitudes from teachers, Bad learning environment, and Bad relations with peers or teachers, which are negative counterparts of some of the variables directly derived from the HSF. The 2,708 responses were coded using MaxQda 11.2.5 (software for qualitative data analysis in academic research) (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). The responses were coded through keywords/expressions, and a nominal scale was used to quantify the variables (0 = not evident or not valued in the answer; 1 = valued in the answer). The research team was involved in the creation of the coding grid and the data codification. This analysis was used to validate (or not) the 22 variables of the HSP framework (UNESCO, 2016) as they apply to Portuguese students (see Table 3).

The resulting quantitative data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics, including hypothesis testing (t-tests, ANOVA, Sheffé test, Cohen’s d. Effect size was calculated by partial eta squared [ηp2], considering 0.02 as a small effect, 0.13 as a medium effect, and 0.26 as a large effect). Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS v.29.

3. Results

3.1. Portuguese students’ level of happiness at school

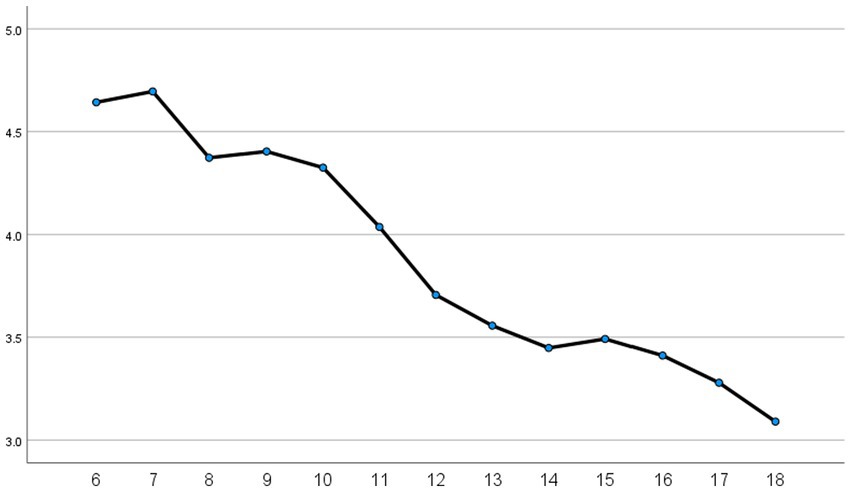

The global happiness level in our sample is 3,67 (0,95), showing that the students are moderately happy. The mode of happiness is four (4), with 12% of students declaring level one (very unhappy) and two (unhappy). In total, 88% of students are on the positive spectrum, with 41% declaring level 4. Differences between the age clusters proved to be significant, with a medium effect size (F = 172.15, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.16). A posthoc Sheffé test revealed significant differences among all four age groups considered (p < 0.001).

Age differences are evident, as the students declare themselves unhappier as they grow older. Six- and seven-year-olds report being very happy at school, while 16-year-olds and above report only slightly above 3.

No significant differences between female and male students were found (t = −88, p > 0.05) (see Figure 1).

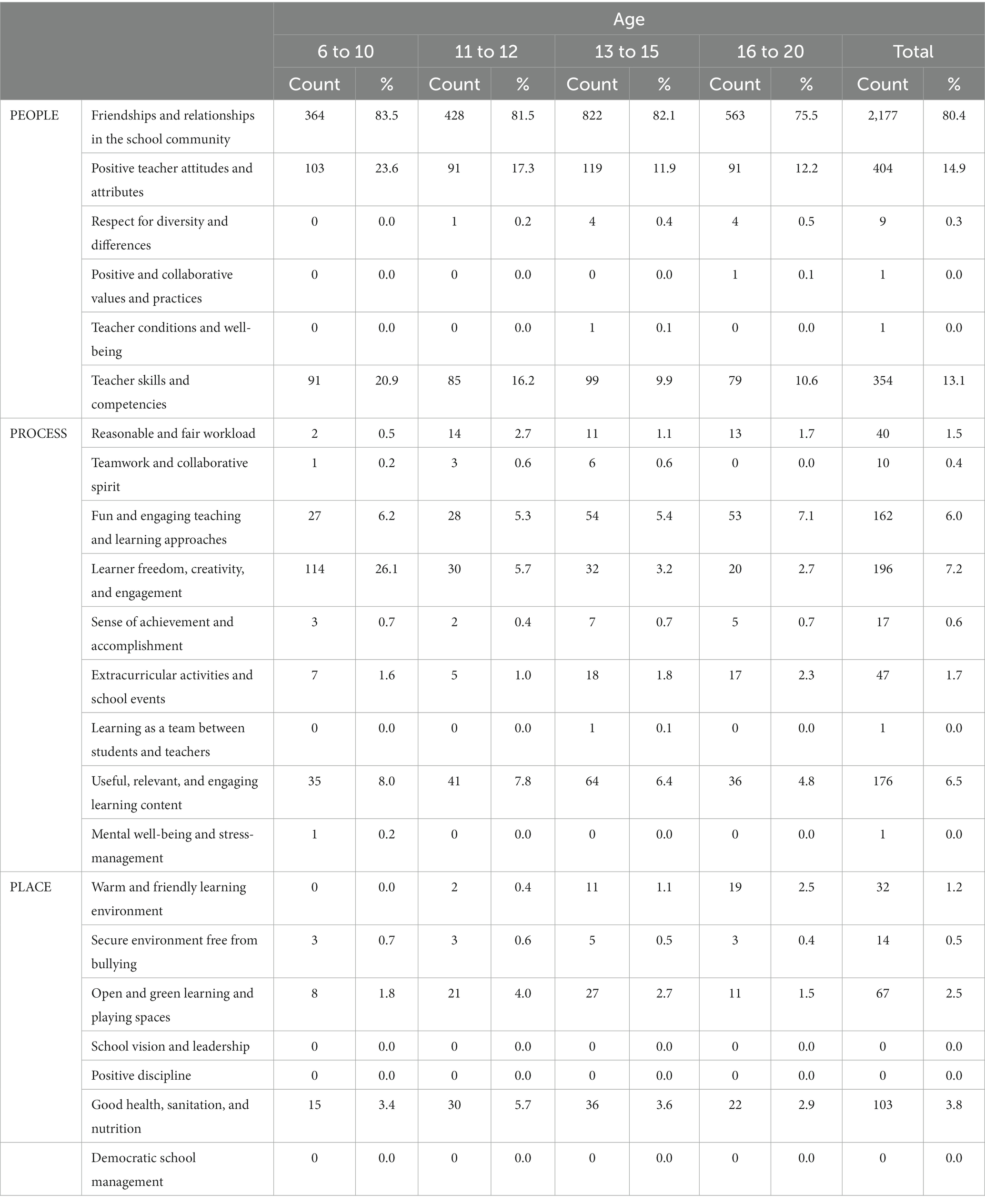

3.2. What makes Portuguese students happy at school?

When we asked “What makes you happy in school” as an open question and then codified the answers against the HSP framework’s 3 dimensions and 22 variables (Table 4), the pattern that emerged was obvious: The dimension “people” was referred to by 83.8% of students, with a relevant emphasis on friendship, and relationship with peers, clearly the most important aspect for students feeling happy at school (80.4%), as can be seen in Table 4. There is an association between feeling happier and reporting friends as an aspect of feeling happy at school (t = 5.53, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.294). The t-test shows a significant difference with a small effect size. We remark, however, that the importance attributed to friends seems to decrease as age increases (as determined by an ANOVA: F = 5.5, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.001), although the effect size is small.

Teachers emerge as the second most crucial variable in the “people” dimension, with attitudes being referred to by 15% of students, and 13% referring to their competencies and teaching capacities. Relations with teachers are also significantly correlated with the self-reported level of happiness (t = 8.55, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.41) as well as teacher competence (t = −7.34, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.42).

The “process” dimension was referred to by 21.9% of students with particular highlights of the learning process: creativity (7.2%) and fun learning activities (6.0%), as well as relevant content (6.6%). All the other variables were seldom referred to, or not referred to at all.

Finally, “places” was referred to by 7.6% of students, particularly with regard to the quality of outdoor spaces and health and nutrition.

Age has a significant impact on the dimension “people” (ANOVA, F = 15.12, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02) with a decreasing level of importance, and “process” (ANOVA, F = 30.98, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03) as younger respondents, in the first three cohorts, value this aspect more than secondary-age students.

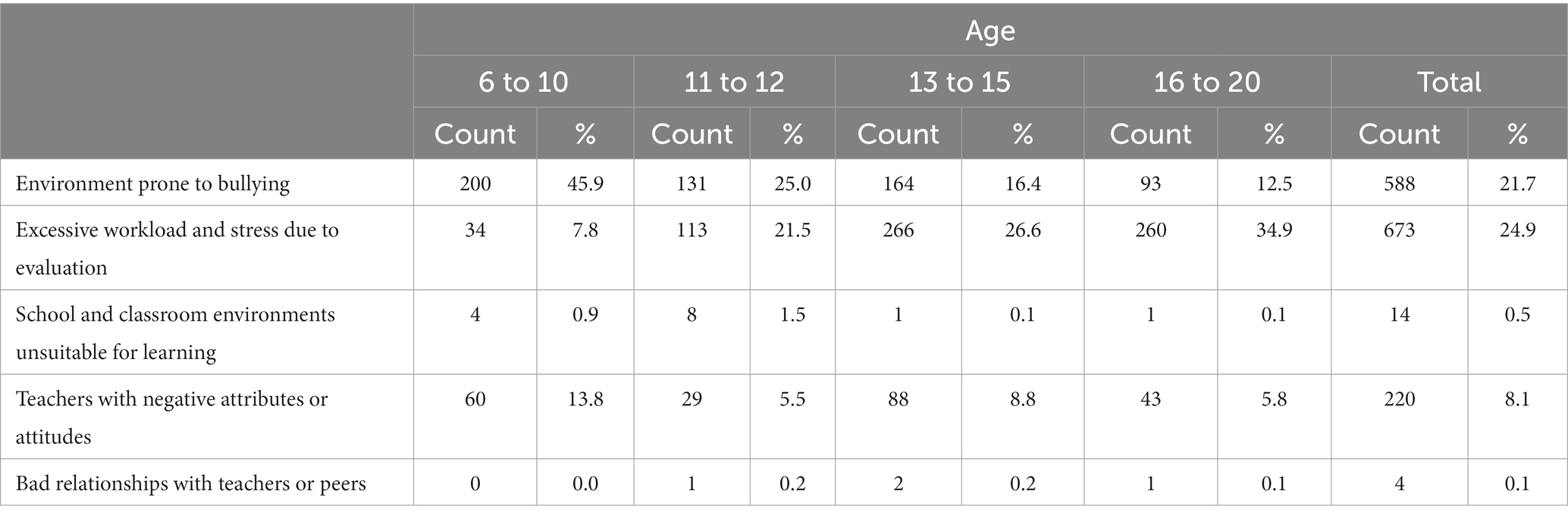

3.3. What makes Portuguese students unhappy at school?

When students were asked about what makes them unhappy, their responses highlighted excessive workload (24.9%) and bullying (21.7%) as the primary sources of discomfort at school (Table 5).

Four of these five variables show significant differences with age group: bullying (F = 74.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08), workload (F = 39.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04), classroom environment (F = 5.77, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), and teachers’ attitudes (F = 9.92, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), with the most relevant impacts pointing to a decrease in bullying with age, and an increase in concern with the workload.

In total, 50.5% of students mentioned at least one aspect that contributed to their unhappiness.

Mentioning bullying as something that makes them unhappy negatively affects the overall happiness reported (t = 5.35, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.25). Being concerned about an excessive workload (t = −5.33, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.24) and teachers with negative attributes (t = −2.22, p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = −0.16), on the other hand, seem to go hand in hand with higher levels of overall happiness.

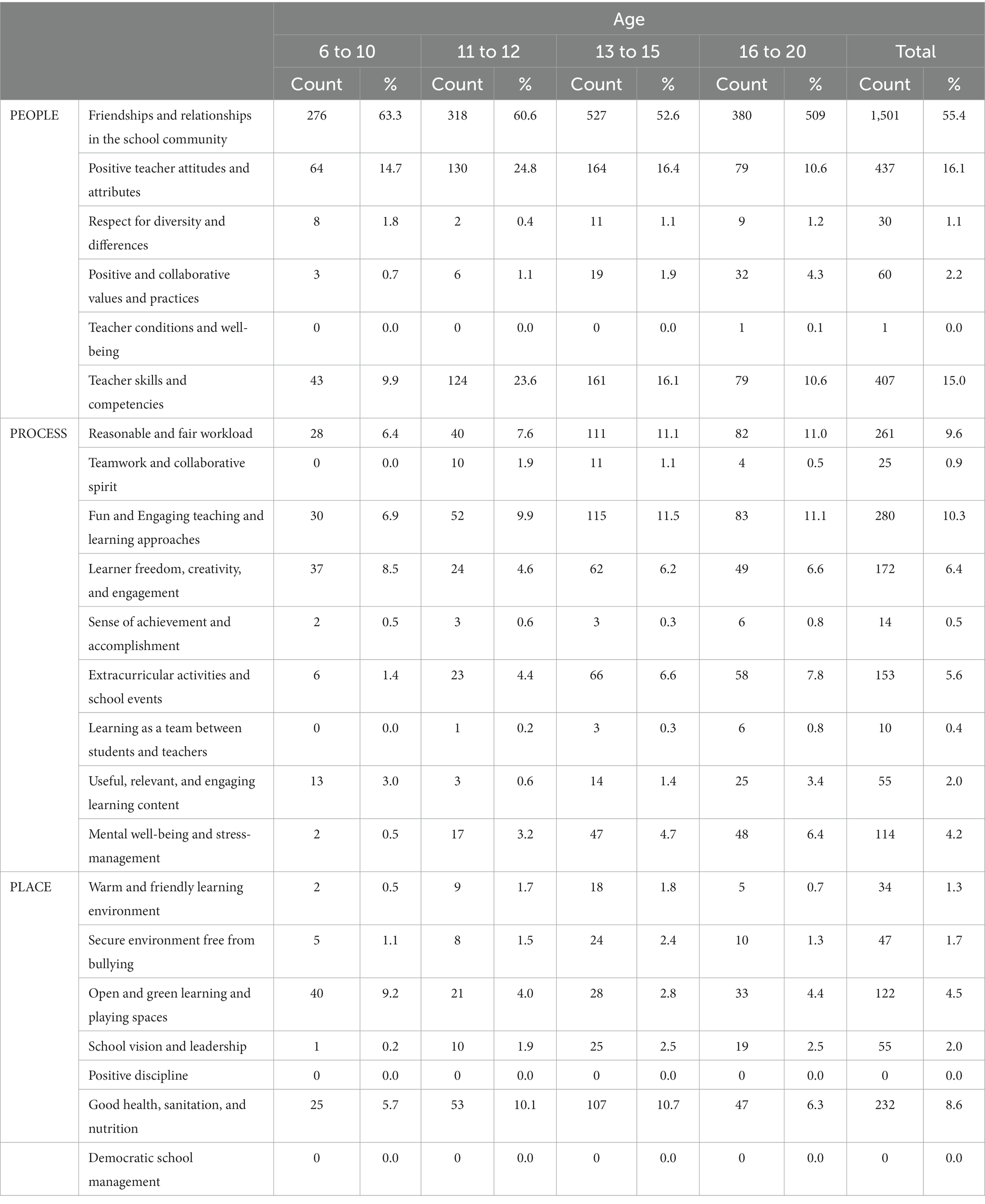

3.4. What are the characteristics of a happy school?

62.3% of the surveyed students referred to “people,” with friends taking the lead (55.4%), followed by teachers concerning both their relation capability (16.1%) and competence (15.0%).

“Process” is equally valued at the school level (21.9%) and the individual level, with particular emphasis on fun teaching approaches (10.3%), fair workload (9.6%), creativity (6.4%), and extracurricular activities (5.6%). At the school level, 4.2% of students also refer to a school that is concerned with stress-management.

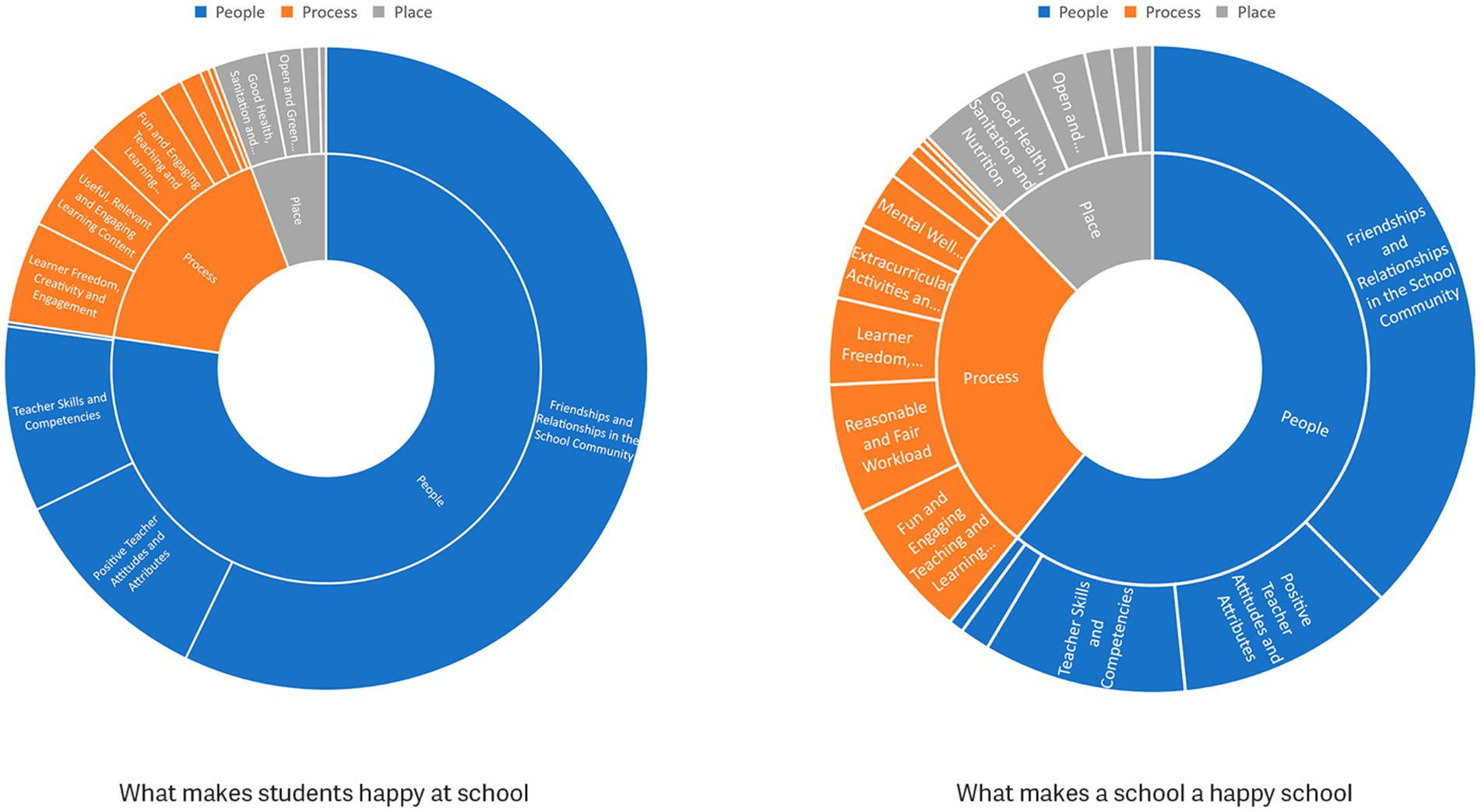

Finally, 16.2% of students referred to the context level (“place”), highlighting food and health concerns (8.6%) and outdoor spaces (4.5%). These results, depicted in Table 6 and particularly in Figure 2, highlight the similarities between their appraisal of what contributes to their personal happiness, and what constitutes a happy school.

Figure 2. Comparison between factors identified as contributing to personal happiness vs. happiness at the school level, % of answers per category.

Age showed significant effects (p < 0.001) on how much the students valued some of these variables, including friendships (ANOVA, F = 8.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), teacher attitudes and attributes (ANOVA, F = 15.77, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02), collaborative practices (ANOVA, F = 7.64, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), teachers’ skills (ANOVA, F = 17.59, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02), learning as a team (ANOVA, F = 2.02, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.002), extracurricular activities (ANOVA, F = 2.02, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), mental well-being (ANOVA, F = 8.80, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), open and green spaces (ANOVA, F = 9.83, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), and health and nutrition (ANOVA, F = 5.59, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01), although with small effect sizes.

4. Discussion

One of the goals of our study was to identify students´ happiness levels at school. We found that the students in our sample were moderately happy, although happiness decreases with age. This finding aligns with others’ (Giacomoni and Hutz, 2008; Huebner et al., 2014; Uusitalo-Malmivaara, 2014; Badri et al., 2018; Mertoğlu, 2020). We found no differences between the levels of happiness reported by girls and boys, which others pointed out (Gómez-Baya et al., 2021). For our population, happiness at school is independent of gender.

We organized data analysis by a category scheme based on the framework established by the HSP framework (UNESCO, 2016). We found that not all the variables that the HSP identifies as characteristics of a happy school are valued by Portuguese students.

4.1. People

Our findings show that friendships and relationships in the school community are the most fundamental reason for students to feel happy in school, which is consistent with other studies claiming the central importance of interpersonal relationships in school in determining the subjective well-being of students (Huebner et al., 2014; Mertoğlu, 2020; Gómez-Baya et al., 2021). Our findings are closer to Díaz (2019), which found that variables making children happy at school are mainly friends and classmates, activities that include games and recreation, learning (specifically when it does not involve feelings of frustration), and achievement and good performance. A happy school is where students have friends, fun and engaging activities, learning opportunities, achievement and good performance, largely because of teachers´ characteristics.

Portuguese students valued having teachers with positive attitudes and attributes. Having this kind of teachers makes students happy because they directly affect the way students learn, what they learn, and the way they interact with each other (Badri et al., 2018; Stronge, 2018; OECD, 2019; Calp, 2020; Gómez-Baya et al., 2021). Having teachers who listen to them and are fair makes them happier, which has also been pointed out as a relevant aspect of happy schools (Mínguez, 2020). This has direct implications for teacher training and lifelong learning, preparing them to promote the inclusion of all students (Inês et al., 2022) and ensuring supervision processes that contribute to reflection about their practices and collaboration among teachers directed to pedagogical improvement (Foong et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2019; Seabra et al., 2021). To be a happy school is to ensure there are teachers like this teaching at school.

In our study, the variable of respect for diversity and difference was rarely pointed out; this might be due to the low “diversity” of students in schools, or the fact that the children consider their friends as equals and do not identify “differences” in them. Nevertheless, this is somewhat contradictory because students responded that bullying is the leading cause of unhappiness at school, i.e., diversity and difference are not fully respected because there are cases of bullying at school (Calp, 2020; Aunampai et al., 2022).

The respondents identified positive and collaborative values and practices as relevant, although infrequently. Therefore, the results of this study do not fully support the results reported by the HSP and others (Talebzadeh and Samkan, 2011). The students’ discourse also failed to identify a concern for teachers’ working conditions and well-being; teacher happiness influences their interactions with students (Talebzadeh and Samkan, 2011). These aspects are essential in combating teacher burnout (Capone et al., 2019). However, it appears that the students are unaware of variables relating more directly to teachers. Future studies considering teachers’ perspectives might further illuminate this aspect. Just as the HSP values teacher skills and competencies, so do the respondents in this study: teachers’ characteristics impact the teaching process (Talebzadeh and Samkan, 2011). Parents agree corroborate this feeling (Feraco et al., 2023).

4.2. Process

Students did not value a reasonable and fair workload, which could mean that it does not make them happy at school. However, it could also mean that they have an unfair workload and that this aspect would be necessary for their happiness in school, which would match the findings of the HSP framework (UNESCO, 2016). Further research into this dimension, potentially including in-depth interviews, is necessary to discriminate between these possibilities.

Also, teamwork and collaborative spirit were not highly valued, although group activities with colleagues contribute to students´ happiness (Lee and Yoo, 2014). This might mean that working in a group or collaboratively in Portuguese schools is not common.

Learning through fun and engaging teaching and learning approaches makes students feel happy in school, which agrees with the findings of HSP (UNESCO, 2016). Students assigned importance to learning freedom, creativity, and engagement – one of the characteristics of a happy school found in other studies (Soleimani and Tebyanian, 2011). This means that, for the youngest, a happy school encourages students to engage in interesting teaching practices, and also allows them to be creative.

The HSP pointed out that one of the variables contributing to a happy school is having a sense of achievement and accomplishment, which matches others´ findings (Talebzadeh and Samkan, 2011); our study confirms this variable, although in a tenuous way. This may mean that, although Portuguese legislation allows for the recognition of students, not all schools do so.

The existence of extracurricular activities and school events is reported as being relevant for students to feel happy at school (Huebner et al., 2014), in line with parents ‘perspectives (Feraco et al., 2023; Gramaxo et al., 2023). Participating in extracurricular activities relates to students´ life satisfaction (Feraco et al., 2023) and it’s a characteristic of a happy school (UNESCO, 2016). In Portugal, schools attended by students up to the age of 12 often have extracurricular activities.

Portuguese students did not consider learning as a team between students and teachers essential to feeling happy at school. Although it was not valued by the respondents of this study, the HSP points out that learning as a team between students and teachers is a variable that contributes to a happy school (UNESCO, 2016). This may mean that it is not usual for Portuguese students to work together with their teachers.

The current study found that useful, relevant, and engaging learning content is important for happiness in school; students feel happy with what they learn (Gómez-Baya et al., 2021), which draws attention to curricular issues involved in promoting happy schools (Pacheco and Seabra, 2013). Portuguese students say that what they learn at school should be useful in their daily lives.

The respondents did not refer to mental well-being and stress-management in relevant numbers, although the HSP values this dimension (UNESCO, 2016). We might think that students do not realize the difficulties that teachers might have in terms of stress and well-being.

4.3. Place

A warm and friendly learning environment was reported as necessary for students to feel happy at school, consistent with those who argue that students with better results on standard tests attend schools with a learning-friendly environment (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006; Macneil et al., 2009; UNESCO, 2021). A happy school has an orderly environment, conducive to learning.

Our study has identified a weak appreciation of a secure environment free from bullying, although it is considered necessary when we analyze a happy school (Huebner et al., 2014; Calp, 2020; Mertoğlu, 2020). Children are more likely to reach their social, emotional, and academic potential in a safe, supportive, and collaborative school environment (OECD, 2019). Children who perceive their school environment as safe and supportive are likelier to achieve expected academic and social outcomes (Huebner et al., 2014). This can mean that respondents know that, in a happy school, there’s no room for bullying, and a happy school is a safe place.

Our respondents valued the existence of open and green learning and playing spaces, consistent with the HSP and others, who claimed that, during the pandemic, the fact of having or not having an outside area was noted (Quay et al., 2020). Physical space is essential, and in a dream school, it should be large (Ince et al., 2022). In a happy school, students learn outdoors, making the playground and nature their classroom.

Despite being less valued by the students in our sample, school vision and leadership is a variable that contributes to a happy school from the HSP perspective (UNESCO, 2016). School vision and leadership promote good learning conditions (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006; Dumay, 2009; Heck and Hallinger, 2010; Bolívar, 2012); hopefully, this variable will emerge with a bolder emphasis when the teachers´ opinion is taken into account.

Our respondents do not refer to positive discipline, despite the HSP considering this a variable contributing to a happy school; it could mean that Portuguese students are used to a more traditional form of discipline.

Respondents consider good health, sanitation, and nutrition relevant, in line with the HSP (UNESCO, 2016). For them, a happy school has good food and clean areas. Students do not value the existence of democratic school management, unlike the HSP (UNESCO, 2016). This can mean that Portuguese school do not involve students in school management decisions.

5. Conclusion

We can conclude that most children in the sampled Portuguese public schools feel at least moderately happy at school, although the level of happiness at school decreases with age, and some children report feeling unhappy or very unhappy, stressing the need for adequate intervention to help schools effectively be happy for all students.

The main results of our analysis, which involved 2,708 students from different educational levels, show that happiness is linked to friends and people, with students amply referring to this dimension. Happiness positively correlates to creativity, friends, learning strategies, and teachers’ attitudes, competencies, and capacities. These findings are in line with parents’ perspectives (Gramaxo et al., 2023), which reinforces our conclusions. On the other hand, negative attitudes from teachers or bullying can put happiness at risk. When students refer to unhappiness, they also state that “people” are what can make them unhappy through bullying. A relevant aspect that was referred to was the excessive number of classes, which keeps children inside a classroom for long hours.

In summary, we found parallels between HSP and Portuguese students on what a happy school should look like. We have not validated “Teacher Conditions and Well-Being”, which means we validated 5 out of 6 variables in the “people” dimension: (1) Friendships and Relationships in the School Community; (2) Teacher Skills and Competencies; (3) Positive Teacher Attitudes and Attributes; (4) Respect for Diversity and Differences; (5) Positive and Collaborative Values and Practices.

We have validated 9 out of 9 variables in the “process” dimension. We have also validated 5 out of 7 variables in the “place” dimension: (1) Good Health, Sanitation, and Nutrition; (2) Open and Green Learning and Playing Spaces; (3) School Vision and Leadership; (4) Secure Environment Free from Bullying; (5) Warm and Friendly Learning Environment. In this dimension, we have not validated “Positive Discipline” and “Democratic School Management.”

When we build the bridge between the individual and the institutions, i.e., schools, we realize that “people” is the most relevant aspect on both levels. However, when answering the question of “what makes a happy school,” students were more pragmatic. They focused on the external elements susceptible to policymakers’ intervention: better teaching strategies, more organized timetables, and creative and extracurricular activities. Context-level variables such as food and outdoor spaces were also referred to at the school level. These aspects should, therefore, be priority targets of policymakers’ and practitioners’ efforts for school improvement.

Our study has some limitations. We acknowledge that the fact that we have studied a non-probabilistic sample limits the possibility of generalizing the results to the national population. Therefore, our conclusions apply only to the studied sample.

Despite these limitations, this study was pioneering in addressing the happy schools construct in Portugal. We gathered data from students of all levels of mandatory education and multiple regional contexts, representing a variety of student realities. Also, despite collecting data from a large number of participants, we gathered qualitative data in children’s own words, which allowed us to develop a more naturalistic and unprompted understanding of what children value in their school experience. The framework was built upon a study conducted in a very different cultural reality, impacting how aspects of happy schools are valued (Stearns, 2019). Therefore, assessing what features are relevant to Portuguese children and youth is valuable.

This study obtained original knowledge to understand the happiness dimension of the Portuguese student population, while providing clues on how to foster happier schools and avoid unhappiness.

Further research is needed, questioning teachers, school staff, and principals. Only by considering the perspectives of all those involved will we fully understand happiness at school and clearly define which HSP (UNESCO, 2016) variables are relevant to the Portuguese reality.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the LE@D, Open University (CE-Doc. 23–03), and the General Directorate of Education (Portugal), under the number 0694400004. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

PG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GD: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was financed by national funds through FCT—Fundação Para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP, in the projects UIDB/04372/2020 and UIDP/04372/2020. Publication financed by the Scientific Research Incentive Award of the Universidade Aberta, attributed to FS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Luís Borges for his help with data visualization.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alexander, R., Aragón, O. R., Bookwala, J., Cherbuin, N., Gatt, J. M., Kahrilas, I. J., et al. (2021). The neuroscience of positive emotions and affect: implications for cultivating happiness and wellbeing. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 121, 220–249. doi: 10.1016/J.Neubiorev.2020.12.002

Aunampai, A., Widyastari, D. A., Chuanwan, S., and Katewongsa, P. (2022). Association of bullying on happiness at school: evidence from Thailand’s National School-Based Survey. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 27, 72–84. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2021.2025117

Badri, M., Al Nuaimi, A., Guang, Y., Al Sheryani, Y., and Al Rashedi, A. (2018). The effects of home And school on Children’s happiness: a structural equation model. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 12:17. doi: 10.1186/S40723-018-0056-Z

Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R., and Benbenishty, R. (2017). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, And academic achievement. Rev. Educ. Res. 87, 425–469. doi: 10.3102/0034654316669821

Björklund, A., and Salvanes, K. (2010). “Education And family background: mechanisms and policies” in Handbook of the economics of education. eds. E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, and L. Woessmann (The Netherlands: Elsevier), 201–247.

Bolívar, A. (2012). Melhorar Os Processos E Os Resultados Educativos: O Que Nos Ensina A Investigação. Translated By Mónica Franco. Vila Nova De Gaia: Fundação Manuel Leão.

Booker, C. L., Skew, A. J., Sacker, A., and Kelly, Y. J. (2014). Well-being in adolescence - an association with health-related behaviors: findings from understanding society, the UK household longitudinal study. J. Early Adolesc. 34, 518–538. doi: 10.1177/0272431613501082

Calp, Ş. (2020). Peaceful and happy schools: how to build positive learning environments. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 12, 311–320. doi: 10.26822/Iejee.2020459460

Capone, V., Joshanloo, M., and Park, M. S.-A. (2019). Burnout, depression, efficacy beliefs, and work-related variables among school teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res. 95, 97–108. doi: 10.1016/J.Ijer.2019.02.001

Cohen, J., and Michelli, N. M. (2009). School climate: research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 111, 180–213. doi: 10.1177/016146810911100108

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., Mcpartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., et al. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington: National Center for Educational Statistics.

Dantas, A. R. (2018). Life is what we make of it: Uma Abordagem Sociológica Aos Significados De Felicidade. Sociol. Line 18, 13–34. doi: 10.30553/Sociologiaonline.2018.18.1

Díaz, A. S. L. (2019). Happiness at school ¿what do the children say? Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Y Valore Vi 2:17.

Dumay, X. (2009). Origins and consequences of schools’ organizational culture for student achievement. Educ. Adm. Q. 45, 523–555. doi: 10.1177/0013161x09335873

Dutschke, G. (2013). Factores Condicionantes De Felicidade Organizacional: Estudio Exploratorio De La Realidad En Portugal. Rev. De Estud. Empresariales 1, 21–43.

Dutschke, G., Jacobsohn, L., Dias, Á., and Combadão, J. (2019). The job design happiness scale (Jdhs). J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 32, 709–724. doi: 10.1108/Jocm-01-2018-0035

Engels, N., Hotton, G., Devos, G., Bouckenooghe, D., and Aelterman, A. (2008). Principals in schools with a positive school culture. Educ. Stud. 34, 159–174. doi: 10.1080/03055690701811263

Feraco, T., Resnati, D., Fregonese, D., Spoto, A., and Meneghetti, C. (2023). An integrated model of school students’ academic achievement And life satisfaction: linking soft skills, extracurricular activities, self-regulated learning, motivation, And emotions. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 38, 109–130. doi: 10.1007/S10212-022-00601-4

Ferreira, A. R. (2018). “Comportamentos De Saúde E Felicidade Em Adolescentes: Um Estudo Exploratório.” Dissertação De Mestrado, Departamento De Psicologia E Educação, Universidade Da Beira Interior - Faculdade De Ciências Sociais E Humanas.

Foong, L. Y., Yean, M. B., Nor, M., and Nolan, A. (2018). The influence of practicum supervisors’ facilitation styles on student teachers’ reflective thinking during collective reflection. Reflective Pract. 19, 225–242. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2018.1437406

Gaziel, H. H. (1997). Impact of school culture on effectiveness of secondary schools with disadvantaged students. J. Educ. Res. 90, 310–318. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1997.10544587

Giacomoni, C., and Hutz, C. (2008). Escala Multidimensional De Satisfação De Vida Para Crianças: Estudos De Construção E Validação. Estud. Psicol. 25, 25–35. doi: 10.1590/S0103-166x2008000100003

Giacomoni, C., Souza, L., and Hutz, C. (2014). O Conceito De Felicidade Em Crianças. Psico-Usf 19, 143–153. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712014000100014

Giản, P., Bảo, Đ., Tâm, T., and Tặc, P. (2021). Happy schools: perspectives and matters of organization-pedagogy in School’s building And development. Int. Educ. Stud. 14, 92–102. doi: 10.5539/Ies.V14n6p92

Gilman, R., and Huebner, E. S. (2006). Characteristics of adolescents who report very high life satisfaction. J. Youth Adolesc. 35, 293–301. doi: 10.1007/S10964-006-9036-7

Gizzi, M. C., and Rädiker, S. (2021). The practice of qualitative data analysis: research examples using Maxqda. 1st. Berlin: Maxqda Press.

Gómez-Baya, D., García-Moro, F. J., Muñoz-Silva, A., and Martín-Romero, N. (2021). School satisfaction and happiness in 10-year-old children from seven European countries. Children 8:370. doi: 10.3390/Children8050370

Gramaxo, P. (2013). A Felicidade Organizacional Dos Docentes: Mais Felizes Na Função Que Desempenham Do Que Na Organização Onde Trabalham Dissertação De Mestrado Tese De Mestrado Em Ciências Da Educação Não Editada, Universidade Nova De Lisboa - Faculdade De Ciências Sociais E Humanas.

Gramaxo, P., Seabra, F., Abelha, M., and Dutschke, G. (2023). What makes a school a happy school? Parents’ perspectives. Educ. Sci. 13:375. doi: 10.3390/Educsci13040375

Heck, R. H., and Hallinger, P. (2010). Testing a longitudinal model of distributed leadership effects on school improvement. Leadersh. Q. 21, 867–885. doi: 10.1016/J.Leaqua.2010.07.013

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., and Sachs, J. (2012). World happiness report. New York: UN Sustainable Development Solutions Net-Work.

Holder, M., and Coleman, B. (2009). The contribution of social relationships to Children’s happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 10, 329–349. doi: 10.1007/S10902-007-9083-0

Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., Xu, J., Long, R. F., Kelly, R., and Lyons, M. D. (2014). “Schooling and Children’s subjective well-being” in Handbook of child well-being: theories, methods and policies in global perspective. eds. A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, and J. E. Korbin (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 797–819.

Ince, N. B., Kardas-Isler, N., Akhun, B., and Durmusoglu, M. C. (2022). The dream school: exploring Children’s views about schools. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 18, 90–104. doi: 10.29329/Ijpe.2022.459.7

Inês, H., Seabra, F., and Pacheco, J. A. (2022). Inclusive curriculum management And teacher training in the 2nd cycle of basic education in Portugal: perceptions of coordinators of initial training courses. Rev. Port. De Educ. 35, 310–330. doi: 10.21814/Rpe.21952

Jongbloed, J., and Andres, L. (2015). Elucidating the constructs happiness and wellbeing: a mixed-methods approach. Int. J. Wellbeing 5, 1–20. doi: 10.5502/Ijw.V5i3.1

Kuckartz, U., and Rädiker, S. (2019). Analyzing qualitative data with Maxqda: text, audio, and video. Cham: Springer.

Kuurme, T., and Heinla, E. (2020). Significant learning experiences of Estonian basic school students at a school with the reputation of a “happy school”. US-China Educ. Rev. A 10, 245–259. doi: 10.17265/2161-623x/2020.06.001

Lavalle, I., Payne, L., Gibb, J., and Jelicic, H. (2012). "Children’S experiences and views of health provision: a rapid review of the evidence.” London: National Children’S Bureau.

Lee, B., and Yoo, M. S. (2014). Family, school, and community correlates of Children’s subjective well-being: an international comparative study. Child Indic. Res. 8, 151–175. doi: 10.1007/S12187-014-9285-Z

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 17, 201–227. doi: 10.1080/09243450600565829

López-Pérez, B., and Fernández-Castilla, B. (2018). Children’s and adolescents’ conceptions of happiness at school and its relation with their own happiness and their academic performance. J. Happiness Stud. 19, 1811–1830. doi: 10.1007/S10902-017-9895-5

López-Pérez, B., Zuffianò, A., and Benito-Ambrona, T. (2022). Cross-cultural differences in Children’s conceptualizations of happiness at school. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 19, 43–63. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2020.1865142

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., and Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness Lead to Sucess? Psychol. Bull. 131, 803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

Macneil, A., Prater, D. L., and Busch, S. (2009). The effects of school culture and climate on student achievement. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 12, 73–84. doi: 10.1080/13603120701576241

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis - theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Austria: Klagenfurt.

Mertoğlu, M. (2020). Factors affecting happiness of school children. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 8, 10–20. doi: 10.11114/Jets.V8i3.4674

Mínguez, A. M. (2020). Children’S relationships and happiness: the role of family, friends and the school in four European countries. J. Happiness Stud. 21, 1859–1878. doi: 10.1007/S10902-019-00160-4

O'Rourke, J., and Cooper, M. (2010). Lucky to be happy: a study of happiness in Australian primary students. Aust. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 10, 94–107.

OECD (2019). “Pisa 2018 results (volume iii): What school life means for students’ lives.” Paris. OECD Publishing.

Oreopoulos, P., and Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Priceless: the nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. J. Econ. Perspect. 25, 159–184. doi: 10.2307/23049443

Pacheco, J. A., and Seabra, F. (2013). “Curriculum field in Portugal: emergence, research, and Europeanization” in International handbook of curriculum research. ed. W. Pinar (London: Routledge), 397–410.

Parey, M., Carneiro, P., and Meghir, C. (2013). Maternal education, home environments, and the development of children and adolescents. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 11, 123–160. doi: 10.1111/J.1542-4774.2012.01096.X

Quay, J., Gray, T., Thomas, G., Allen-Craig, S., Asfeldt, M., Andkjaer, S., et al. (2020). What future/S for outdoor and environmental education in a world that has contended with Covid-19? J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 23, 93–117. doi: 10.1007/S42322-020-00059-2

Rudasill, K. M., Snyder, K. E., Levinson, H., and Adelson, J. L. (2018). Systems view of school climate: a theoretical framework for research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 35–60. doi: 10.1007/S10648-017-9401-Y

Seabra, F., Mouraz, A., Henriques, S., and Abelha, M. (2021). Teacher supervision in educational policy and practice: perspectives from the external evaluation of schools in Portugal. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 29:27. doi: 10.14507/Epaa.29.6486

Seligman, M., Randal, E., Jane, G., Karen, R., and Mark, L. (2009). “Positive education: Positive Psychology and classroom interventions.” Oxford Review of Education. 35, 293–311. doi: 10.1080/03054980902934563

Soleimani, N., and Tebyanian, E. (2011). A study of the relationship between principals’ creativity and degree of environmental happiness in Semnan high schools. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 29, 1869–1876. doi: 10.1016/J.Sbspro.2011.11.436

Stearns, P. N. (2019). Happy children: a modern emotional commitment. Front. Psychol. 10:2025. doi: 10.3389/Fpsyg.2019.02025

Talebzadeh, F., and Samkan, M. (2011). Happiness for our kids in schools: a conceptual model. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 29, 1462–1471. doi: 10.1016/J.Sbspro.2011.11.386

UNESCO (2014). “Learning to live together: education policies And realities in the Asia-Pacific.” Paris: UNESCO Digital Library.

UNESCO (2016). “Happy schools! A framework for learner well-being in the Asia-Pacific.” Paris: UNESCO Digital Library.

UNESCO (2021). “Happy schools: capacity building for learner well-being in the Asia-Pacific; findings from the 2018-2020 pilots in Japan, Lao Pdr, and Thailand.” Paris: Unesco Digital Library.

Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L. (2014). Happiness decreases during early adolescence - a study on 12- And 15-year-old Finnish students. Psychology 05, 541–555. doi: 10.4236/Psych.2014.56064

Veenhoven, Ruut. (2012). Evidence based pursuit of happiness: What should we know, do we know and can we get to know? Munich: University Library of Munich.

Wright, T., Nankin, I., Boonstra, K., and Blair, E. (2019). Changing through relationships and reflection: an exploratory investigation of pre-service teachers’ perceptions of young children experiencing homelessness. Early Childhood Educ. J. 47, 297–308. doi: 10.1007/S10643-018-0921-Y

Zullig, K. J., Koopman, T. M., Patton, J. M., and Ubbes, V. A. (2010). School climate: historical review, instrument development, and school assessment. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 28, 139–152. doi: 10.1177/0734282909344205

Appendix A

Questionnaire applied to the students:

1. How old are you? (Open answer).

2. What is your sex? (Possible answers: Male/Female/Other or prefer not to answer).

3. How happy do you feel at school? (Possible answers: 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very unhappy) to 5 (very happy)).

4. What makes you happy at school? (Open-ended question).

5. What makes you unhappy at school? (Open-ended question).

6. In your opinion, what are the characteristics of a happy school? (Open-ended question).

Keywords: education, students, students’ happiness, happy school, happy school framework

Citation: Gramaxo P, Flores I, Dutschke G and Seabra F (2023) What makes a school a happy school? Portuguese students’ perspectives. Front. Educ. 8:1267308. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1267308

Edited by:

Soledad Romero-Rodríguez, University of Seville, SpainReviewed by:

Gül Kadan, Cankiri Karatekin University, TürkiyeJ. Roberto Sanz Ponce, Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Gramaxo, Flores, Dutschke and Seabra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Patrícia Gramaxo, cGdyYW1heG9AZ21haWwuY29t; Filipa Seabra, RmlsaXBhLlNlYWJyYUB1YWIucHQ=

Patrícia Gramaxo

Patrícia Gramaxo Isabel Flores2

Isabel Flores2 Georg Dutschke

Georg Dutschke Filipa Seabra

Filipa Seabra