- 1Department of Teaching and Learning, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States

- 2Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, United States

Introduction: The personal and societal benefits of providing quality early education experiences are well supported by research. While there is growing evidence as to the specific features and experiences that define quality and effective early education classrooms, there remain open questions as to whether these features and experiences differ as a function of grade level.

Methods: Using a behavioral-based observation system, researchers conducted day-long classroom observations in 98 prekindergarten through 2nd grade U.S. classrooms. Key features of these classrooms were examined to determine the extent to which features vary (or remain consistent) across grade levels.

Results: This study found that across the early school years, instruction tends to focus on basic skills provided in whole-class groupings that were related to passive participation from students. Across all grades, there was a predominant focus on language arts.

Discussion: These findings highlight the need to consider the appropriateness of pushing down the academic demands typical in 1st grade into prekindergarten and kindergarten classrooms in the U.S.

1. Introduction

The personal and societal benefits of providing quality early education experiences are well supported by research and indicate the importance of providing children with a strong foundation for subsequent learning and development in the early grades (e.g., Pianta et al., 2008; Chetty et al., 2011; Watts et al., 2014). However, there remain open questions about the features and experiences that define quality and effective early education classrooms (e.g., Farran et al., 2017; Burchinal, 2018; Christopher and Farran, 2020) and if these features and experiences differ as a function of grade level. The current study aims to extend the current understanding by examining how key features of prekindergarten (PreK) through 2nd grade U.S. classrooms vary (or remain consistent) across grade levels when accounting for school-level variance. We examine if children’s instructional experiences vary by grouping practices (whole group, small groups, centers, individual child seat work), academic content area mathematics (language arts, science, social studies), teachers’ pedagogical methods (amount and quality of instruction, behavior approving, behavior disapproving, emotional tone, listening to children), and children’s learning behaviors (social learning, passive instruction, sequential goal-oriented learning, level of involvement, and talking). Moreover, we explore associations between these various aspects of learning experiences and children’s level of involvement and teachers’ instructional quality to support higher-order mental processing.

1.1. Impacts of the early years

Estimations of literacy, mathematics, science, and social studies performance trajectories across kindergarten to 12th grade in the U.S. highlight the vital importance of the early years (Bloom et al., 2008). Standardized estimates of annual progress based on nationally normed assessments show great variability based on grade level, with the largest effects observed across the early years with incrementally decreasing magnitude of growth through the end of high school in the U.S. For example, the average standardized annual growth in literacy was estimated to be 1.52 standard deviations (SD) from kindergarten to grade 1, 0.97 SD from 1st to 2nd grade, and 0.60 SD from 2nd to 3rd grade, compared to an annual growth from 11th to 12th grade of only 0.06 SD. Similarly, annual gains in mathematics were 1.14, 1.03, and 0.89 SD for kindergarten to 1st grade, 1st to 2nd grade, and 2nd to 3rd grade, respectively, while grade 11th to 12th grade gain was only 0.01 SD. These effects coincide with other work examining achievement trajectories from PreK to 5th grade which found about 76% of the total change in math scores from this timeframe occurred by 1st grade and nearly 100% by 3rd grade (Pianta et al., 2008). Similar effects were found for reading with 80% of the total change in reading scores occurring by 1st grade and 98% occurring by 3rd grade for typical readers. With substantial learning occurring in the early years, it is essential to understand the features of early childhood education settings that contribute to children’s learning and development, including how these features might evolve and change throughout the early elementary grades. Enhancing knowledge of these processes will inform efforts to sustain and build on children’s early learning.

1.2. Alignment of instructional practices across early years

Coordination or alignment of PreK through 3rd grade standards, curricula, and instructional practices is a key consideration for improving early childhood education among developmental scientists, educators, and policymakers in the U.S. (e.g., Bogard and Takanishi, 2005 Stipek et al., 2017 Kauerz, 2018). The concept refers to a broad array of policies and practices designed to launch children on a positive developmental pathway in the early grades in hopes of sustaining and building on and ensuring that gains typically made in PreK (e.g., Gormley et al., 2005; Yoshikawa et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2017; Weiland et al., 2020) do not fade out (e.g., Hill et al., 2015; Bailey et al., 2017; Durkin et al., 2022).

Coordination of PreK through 3rd-grade instructional practices does not imply that the practices should remain constant over the course of the early school years or that practices that might be developmentally appropriate or effective for one grade are appropriate for another. For example, there has been a growing concern in the U.S. about the pushing down of instructional practices, in particular, the academic demands typical to 1st grade and above into PreK and kindergarten classrooms (Alford et al., 2016; Bassok et al., 2016; Markowitz and Ansari, 2020). The concern is that the heightened focus on rote-constrained academic instruction in the early years is not developmentally appropriate or effective (e.g., Magnuson et al., 2007; McCormick et al., 2021; Burchinal et al., 2022), and could lead to redundancy in the content being taught from grade to grade (Cohen-Vogel et al., 2021), and reduce children’s enthusiasm to learn (Farran and Lipsey, 2015). A clear example of the need to consider coordination across the early years is evidence that suggests children who have attended PreK are often re-taught information they were previously exposed to Claessens et al. (2014), Bassok et al. (2016), and Cohen-Vogel et al. (2021). While learning standards such as the Common Core State Standard Initiative in the U.S. aims to facilitate this alignment for literacy and math from kindergarten to 12th grade, evidence of redundancy indicates more needs to be done to support alignment and the progression of content from grade to grade.

To understand how best to provide children with a set of coordinated learning experiences, ranging from child-directed centers and exploration to teacher-directed passive instruction across the early primary grade that contributes to children’s learning and development, there is a need to first understand the current instructional experiences provided across this timeframe (e.g., National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2002, 2005; Pianta et al., 2007; Engel et al., 2021; Justice et al., 2021).

1.3. Instructional experiences in the early years

While greater gains in academic achievement occur in the early years compared to subsequent years, there is variability in the academic gains children make, variability which is associated with the instruction experiences provided to children (e.g., Mashburn et al., 2008; Weiland et al., 2013; Farran et al., 2017; Burchinal, 2018). Prior work has indicated the importance of grouping practices, academic content area, teachers’ pedagogical methods, and children’s learning behaviors.

1.3.1. Grouping practices

Grouping practices capture how children are grouped into learning experiences and commonly include differentiation between teacher-directed whole group instruction small group instruction, child-directed centers (or group work) where children are allowed to collaborate and individual work (e.g., National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2020). Grouping practices differ based on teachers’ goals and objectives. Whole group is beneficial for providing a common learning experience to all children, including the facilitation of class discussions and transmission of information all students need to receive. On the other hand, small group instruction is beneficial for supporting differentiated instruction and allows for greater child–child and teacher-child interactions under the guidance and facilitation of the teacher. Centers and individual work provide unique opportunities for hands-on active learning and provide opportunities for children to work deeply with content either with others or alone.

There is currently an open question as to the optimal balance between how much class time should be dedicated to child-directed learning experiences (Zosh et al., 2018; Skene et al., 2022) and more structured teacher-directed learning experiences (Fuller et al., 2017) with little empirical evidence to inform how much time in different groupings is best and if that varies depending on children’s grade level. An initial step to reaching this understanding is knowing the frequency of use of different grouping practices and how they vary across the early school years (e.g., Baines et al., 2003; Pianta et al., 2007; Vitiello et al., 2020; Engel et al., 2021; Justice et al., 2021). For example, Justice et al. (2021) found that there was an increase in whole class instruction and individual child work from PreK to 3rd grade, with 48% of groupings in 3rd grade being whole class instruction and 36% being individual child work. This corresponded with a general decrease in the use of small groupings and dyads which were most common in PreK (28 and 15%, respectively). It is currently not clear if this shift to more whole group and teacher-directed experiences in the later elementary grades is appropriate and conducive to greater learning.

1.3.2. Academic content

Regarding how much time is devoted to different academic content areas across the early school years, there is evidence of an evolution in focus from PreK to 3rd grade with most instructional time spent on literacy content followed by mathematics with little time spent on science, social studies, and the arts (e.g., National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2005; Fuligni et al., 2012; Vitiello et al., 2020; Engel et al., 2021; Justice et al., 2021). For example, Vitiello et al. (2020) found that 41% of instruction focused on literacy in kindergarten compared to 21% for mathematics and less than 5% each for science and social studies. Moreover, these percentages represented a significant increase from PreK. Similarly, Justice et al. (2021) found an increased focus on academic content from PreK to kindergarten with relative consistency between kindergarten and 3rd grade. The focus on literacy and mathematics instruction is not unsurprising as prior research has indicated that the amount of instructional time spent in a given content area is related to learning gains in that content area (e.g., Connor et al., 2006; Donat and Donat, 2006; Wang, 2010; Christopher and Farran, 2020).

1.3.3. Teacher pedagogical methods

In early childhood classrooms, teachers engage in a variety of tasks to effectively support the learning and development of children. The primary task of teachers is to provide instruction on the knowledge, content, and skills that children need to be successful in school and life. As previously noted with regards to time spent in content area instruction, it is not surprisingly the time in instruction has been shown to relate positively to children’s learning gains while increased time in non-instructional transitions is negatively related to gains (e.g., Pianta et al., 2008; Sonnenschein et al., 2010; Christopher and Farran, 2020).

The quantity of instruction is only part of the picture. The quality of the instruction provided has also been shown to be a significant predictor of children’s learning and development (e.g., Hill et al., 2007; Mashburn et al., 2008; Baumert et al., 2010; Kunter et al., 2013; Tompkins et al., 2013). Of particular importance is the use of literal versus inferential questions (Chen and Liang, 2017). Quality inferential instruction supports deep processing and high cognitive demands that “include questions and statements that require children to think deeply and offer opportunities to develop higher-order mental processing skills [while] low cognitive demands are characterized as those that contain closed questions that require a one-word response and minimal additional information from the students” (Durden and Dangel, 2008, p. 260). While the content being taught across the early years may vary, the quality of instruction and the level of cognitive challenge are important predictors of student learning from PreK (Farran et al., 2017) to high school (Kunter et al., 2013).

One means by which teachers facilitate effective instruction is through their verbal interaction with children or teachers’ linguistic responsiveness to children (e.g., Gonzalez et al., 2014; Hollo and Wehby, 2017; Justice et al., 2018). Prior research in PreK classrooms found that teachers spend the majority of their day talking (Nesbitt and Farran, 2021). This trend has also been found in elementary grades (kindergarten to 4th grade) where teachers have been observed talking significantly more than students (Hollo and Wehby, 2017). The quality of instruction is also related to how much teachers listen to children as it reflects teacher responsiveness. Evidence suggested that extended wait-time or silence during teacher-student interactions was associated with a greater quality of verbal interactions and was associated with student achievement among kindergarten students (McKay, 1988). Moreover, teacher listening has been shown to be positively related to children’s language development (Mascaerño et al., 2016) and student involvement (Cadima et al., 2015).

In addition to being facilitators of the acquisition of content knowledge, teachers also facilitate the emotional climate and tone of their classroom. A positive emotional climate is associated with positive outcomes for young children (e.g., Pianta et al., 2005, 2008; Early et al., 2007; O’Connor, 2010; Christopher and Farran, 2020). Teachers’ use of positive techniques to engage children in learning predicted greater learning gains across the elementary school for both math and literacy (Pianta et al., 2008) though rating of the quality of the emotional environment tends to be higher in 1st grade than 3rd grade (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2005) Such techniques include the use of positive reinforcement and approval, refraining from disapproving comments and expressions, and generally providing a pleasant and vibrant emotional tone (e.g., Farran et al., 2017; Christopher and Farran, 2020). It is theorized that positive emotions assert that a mindset broadened by positive approvals is linked to the “discovery of new knowledge, new alliances, and new skills” (Fredrickson, 2013, p. 815).

1.3.4. Children’s learning behaviors

The learning experiences of children are not only shaped by teachers but by the children themselves. For example, the level of children’s participation in learning experiences is the result of the dynamic interactions between the individual child and their classroom environment (e.g., Skinner and Belmont, 1993; Shonkoff and Phillips, 2000). For children to benefit from their learning experiences they must engage in learning tasks and activities (Fredricks et al., 2004). As early as PreK, children’s level of involvement in their classrooms has been found to be related to current and future achievement (e.g., Ponitz et al., 2009; Williford et al., 2013; Portilla et al., 2014; Robinson and Mueller, 2014; Nesbitt et al., 2015). Moreover, evidence indicates that greater levels of involvement were consistently associated with greater learning across 1st to 3rd grade (Ladd and Dinella, 2009) and with engagement being higher in 1st grade compared to 3rd grade (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2005). It is unknown how consistent levels of involvement are in PreK and kindergarten.

One factor that can impact children’s level of involvement is their ability to engage in social learning experiences (c.f., teacher-directed passive instruction). Learning experiences that have often been shown to contribute to academic success are marked by co-learning or engagement with peers and teachers (Ladd, 1990; Wentzel, 1999; Montroy et al., 2014; Nesbitt et al., 2015; Christopher and Farran, 2020). The ability to collaborate and co-engage in learning is positively related to students’ level of involvement in learning (Goble and Pianta, 2017). Moreover, social learning experiences also provide children the opportunity to talk with others which is related to PreK children’s early literacy skills (Nesbitt and Farran, 2021); unfortunately, prior research notes that PreK children only spend 6% of the day in conversations (Early et al., 2010). While the previously described grouping practices indicate incremental greater use of individual or solo tasks from PreK to 3rd grade that lessens the opportunities for social learning (Justice et al., 2021), it is not clear if children’s actual engagement in social learning experiences also changes over the early years. Namely, children could be in a grouping arrangement that would allow for collaboration but not be engaged in an activity that allows for collaboration. For example, a child could engage in a solo activity during centers or passively receive direct instruction from a teacher in small groups. In general, the amount of direct instruction has been found to increase from PreK to kindergarten and remain consistent through the end of 3rd grade (Justice et al., 2021).

It is not only whether children are involved in learning experiences that matters but also the cognitive demands of those experiences that matter to their learning gains. Greater cognitive demands are required and reinforced when children engage in goal-directed mastery tasks with a recognizable goal that requires a sequential series of steps to be completed (Bronson, 1994). Engagement in goal-directed tasks is predictive of greater literacy and mathematics gains across PreK (Nesbitt et al., 2015; Farran et al., 2017) and kindergarten (Cheung and McBride, 2017; Christopher and Farran, 2020). It is not known how the frequency of children’s engagement in goal-directed tasks might vary across the early school years might vary.

1.4. Current study

The current study has two key aims. Firstly, we aim to describe how the instructional experiences of PreK through 2nd grade U.S. classrooms vary (or remain consistent) across grade levels. A key means by which we extend the extant literature is using a dynamic observational approach that quantifies learning experiences via the behaviors of teachers and all students within a classroom (c.f., a smaller random selection of children) across the entire school day. The observational approach also allows for the coding of a wide variety of instructional practices and experiences, including aspects of grouping practices, academic content area, teachers’ pedagogical methods, and children’s learning behaviors. Secondly, we aim to further understand if potential variability in learning experiences across grade levels reflects misalignment rather than developmental-appropriate coordination. We explore associations between the identified aspects of learning experiences and children’s level of involvement as well as teachers’ instructional quality to support higher-order mental processing. The focus on these associations was guided by the consistent evidence across grade levels that greater involvement by students and better quality of instruction by teachers are predictive of children’s learning and developmental gains.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and inclusion criteria

Twenty-five schools were selected across Tennessee that house PreK, kindergarten (K), 1st, and 2nd grade classrooms. For schools with multiple classrooms for a given grade, participating classrooms were randomly selected with a few caveats. We avoided enrolling classrooms with teachers who were (1) new to teaching or (2) had recently switched from teaching to their current grade level. Further, to support the comparability of schools in terms of grades they serve, schools that served grades beyond elementary were excluded from the study. Schools were representative of the state in terms of geographic division (West, Middle, East), locale (urban, suburban, town, and rural, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2005–2006 locale classifications), comparable in terms of size (number of students, number of classrooms per grade), and representative of the state in terms of percent minority and economic disadvantage.

We partnered with the Tennessee Education Research Alliance (TERA), an organization with a formal research-policy-practice partnership between Vanderbilt University and the Tennessee Department of Education. Using state administrative data, TERA identified 437 elementary schools that met the current study’s inclusion criteria. The study sample schools were randomly selected from the list of eligible schools. We oversampled slightly for schools in rural areas given that we have little recent research on instructional practices outside of our urban areas.

The final sample comprised 25 schools: seven from the East, ten from the middle of the state, and eight from the Western region of Tennessee. Seven schools were located in cities/urban areas, three were in suburbs, six were in towns, and nine were in rural areas. Four classrooms per school were included in the study sample (i.e., one from each of grades PreK, K, 1st, and 2nd grades) leading to a total of 100 classrooms from the 25 schools.

2.2. Observation tools and procedures

In the Fall of 2019, the 100 study classrooms completed an all-day classroom observation to capture grouping practices, academic content area, teachers’ pedagogical methods, and children’s learning behaviors. The Teacher Observation Protocol in Primary Grades (TOPG; Farran et al., 2019a) protocol was used to measure observable aspects of kindergarten teachers’ classroom behaviors. The TOPG protocol was completed in tandem with the Child Observation in Primary Grades (COPG; Farran et al., 2019b) used to measure observable child behaviors.

The TOPG and COPG capture classroom behaviors across an entire school day by taking repeated snapshots or sweeps of teachers and children. Observers would complete 20–26 rounds of classroom sweeps for a given observation. Observers first coded the teacher followed by each individual child in the classroom before returning to the teacher to start another round of the observation and coding process. At the onset of the observation, observers would document unique characteristics of children’s clothing to allow for tracking. For each sweep, a classroom member was located and then observed for approximately 3 s (internal count by coder), after which the observer immediately coded 9 areas of behaviors before moving onto the next member of the classroom. While in isolation a given snapshot is a finite piece of information, taken together, this collection of snapshots provided a picture of how individuals spent their time in the classrooms. Coding was done continuously throughout the day, except for outdoor recess, indoor gym, and nap time. All children from a classroom were anonymously observed (no identifiable information was collected) and their data contributed to the classroom’s aggregated scores. The PreK classrooms had one lead teacher and an assistant teacher. All K, 1st, and 2nd-grade classrooms had only one lead teacher. For continuity across grades, we present TOPG data based on only the lead teacher. The observation tool and protocols were identical across all grade levels.

2.2.1. COPG variables

The COPG captures children’s classroom experiences across an array of codes. Verbal codes capture if a child was talking during a given sweep. The schedule codes were used to document the grouping practice used by 75% or more of the class (whole group, small groups including pairs, centers, or individual child work) experienced by a child during an observed sweep, including the lack of an instructional setting (i.e., a transition). Interaction State captures the degree to which children were working together in the context of a learning experience, including associative (mutual activity without a common goal) and cooperative (collaboration toward a shared goal) interactions. The learning demands of the task and the child’s behavior with the activity determine the Type of Task coded. Codes of interest include passive instruction and sequential activities (i.e., activities that require active participation and planning on the part of the child). Lastly, observers collected information on Content focus to see not just what content teachers were presenting, but rather the actual content in which each child was engaged (e.g., mathematics, English Language Arts (ELA), Science, Social Studies, Art). If an activity had more than one content focus, the observer coded the primary focus of a given child at the moment they were observed. Variables from behavior counts were computed as a proportion of sweeps in which the behavior occurred out of the total number of sweeps observed. Data across all the children in a classroom were averaged to estimate the average proportion of sweeps for a given classroom.

In addition to behavioral count data, observers rated students’ Involvement across the day on a 5-point scale from low (0), medium-low, medium, medium-high, and highly involved (4). For example, if a student is in an activity and looks away from time to time but returns to the activity, they would be rated as medium. If they are intensely focused on an activity and seem oblivious to the noises around them, they would be rated high. If a child is off task (e.g., fiddling with another child’s hair), they would be rated as low. A classroom’s average involvement was based on approximately 360 ratings from across the entire school day, with the observer providing a rating of level of involvement each time they swept a child.

2.2.2. TOPG variables

To capture teacher pedagogical methods, codes related to verbal/listening behaviors, teacher task, level of instruction, and teacher tone were collected. The Verbal category captured the behavioral counts of the number of sweeps for which a teacher was observed listening to children. Teacher Task captured the task or activity in which the teacher is engaged and was coded independently of what children are doing, and included instruction, behavior approving, and behavior disapproving. Level of Instruction captured the instruction that is occurring during a specific sweep. It is a rating that ranges from 0 (none) to 4 (high inferential learning). When instruction occurred, it was rated on a scale ranging from 1 (interaction with child and activity) to 4 (high inferential instruction). A rating of 2.0 signified basic instruction (e.g., “What color is this? What letter is this?”). Finally, the Tone code reflects the positive or negative affect of a teacher, ranging from extremely negative (1) to flat (3) to vibrant (5).

2.2.3. Observer training and reliability

COPG/TOPG codes are quantified as either behavioral counts or ratings. To achieve certification, observers attend a two-day training followed by classroom observations completed in tandem with an anchor observer to achieve reliability. Acceptable reliability was defined as 80% exact agreement on codes within each of the seven areas of behaviors. Observers have up to three attempts to achieve reliability and all observers achieved reliability with an experienced anchor observer. Kappa coefficients for COPG interrater reliability ranged from 0.83 to 0.96. TOPG interrater reliability Kappa coefficients ranged from 0.80 to 0.91. For the COPG and TOPG variables based on rating scales, we defined inter-rater reliability as 70% exact agreement. Kappa coefficients for inter-rater reliability on ratings were as follows: 0.74 for student involvement, 0.82 for teacher tone, and 0.89 for level of instruction.

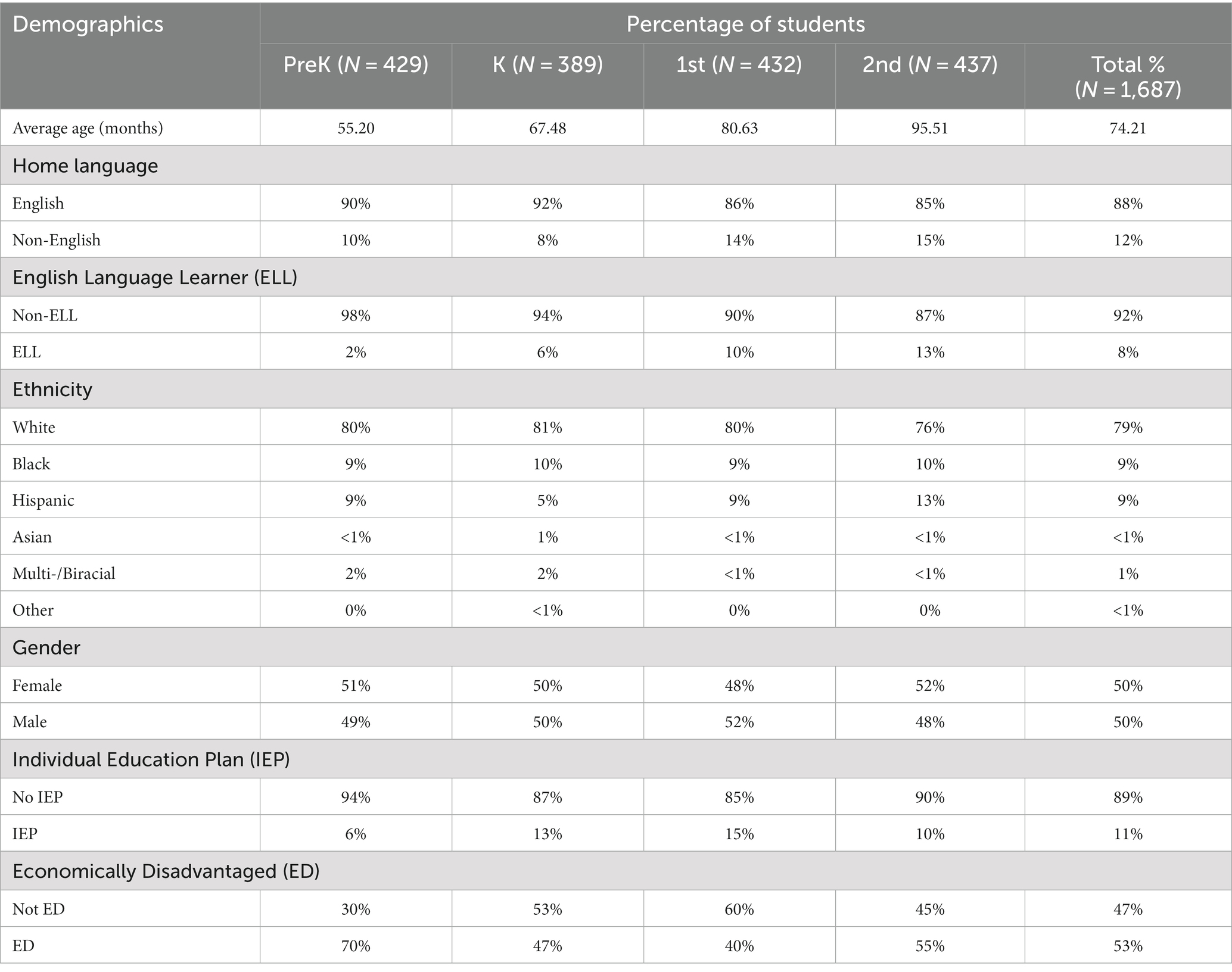

2.3. Demographic data

We received demographic data from each school at the beginning of the study including students’ age, home language, English Language Learner status, race/ethnicity, gender, Individual Education Plan status, and economic disadvantage status, which was defined as qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch. Descriptive statistics by grade level are presented in Table 1.

2.4. Analytic approach

The goal of our analyses was to provide a detailed description of the instructional practices, academic content, and types of activities and opportunities for student interactions that students experienced during the day-long classroom observations.

Prior to running prediction models, the correlations between classroom demographics and classroom process variables were examined. Based on the magnitude and significance of the correlations, final analytic models include percentage economic disadvantage (range r = |0.01 to 0.15|) and percentage minority (range r = |0.03 to 0.22|) as covariates.

To examine the main effect of grade on classroom practices drawn from the COPG (child-level data), we conducted multilevel prediction models to account for children nested in classrooms. We then used covariate-adjusted means derived from the multi-level models to calculate Cohen’s d standardized mean difference effect sizes (MDES) to quantify the magnitude of differences across grades. Estimates of the significance of multiple comparisons included a Bonferroni correction for familywise Type 1 error. To examine the main effect of grade for variables drawn from TOPG (classroom-level data), we conducted univariate ANOVAs. Effect sizes for TOPG were calculated based on classroom-level covariate-adjusted means. We then explored grade as a moderator of the effect of classroom practices on teachers’ level of instruction and students’ involvement using multi-level prediction models (children nested in classrooms). We ran separate models for each of the classroom practices predicting teachers’ level of instruction and children’s level of involvement.

3. Results

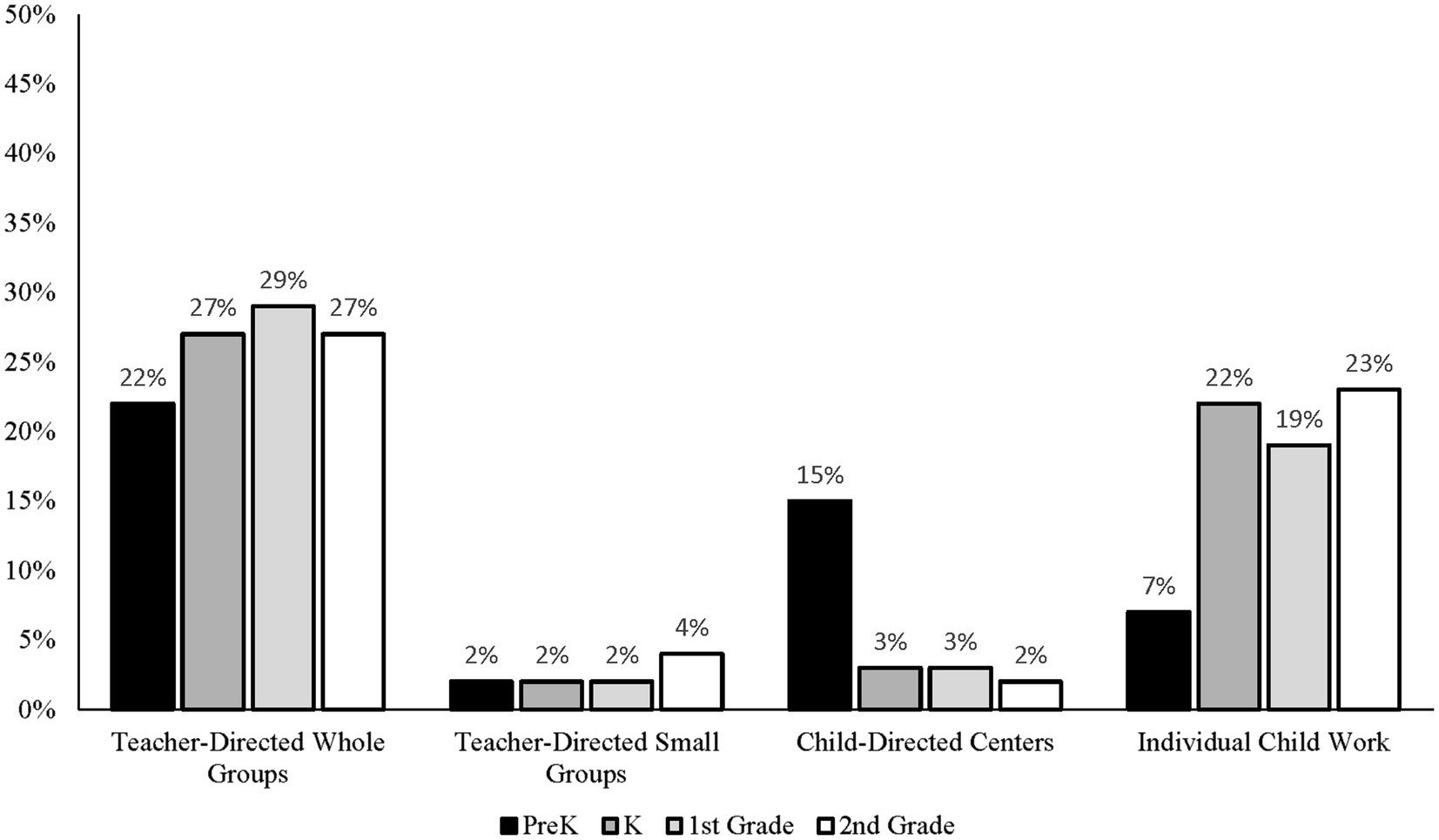

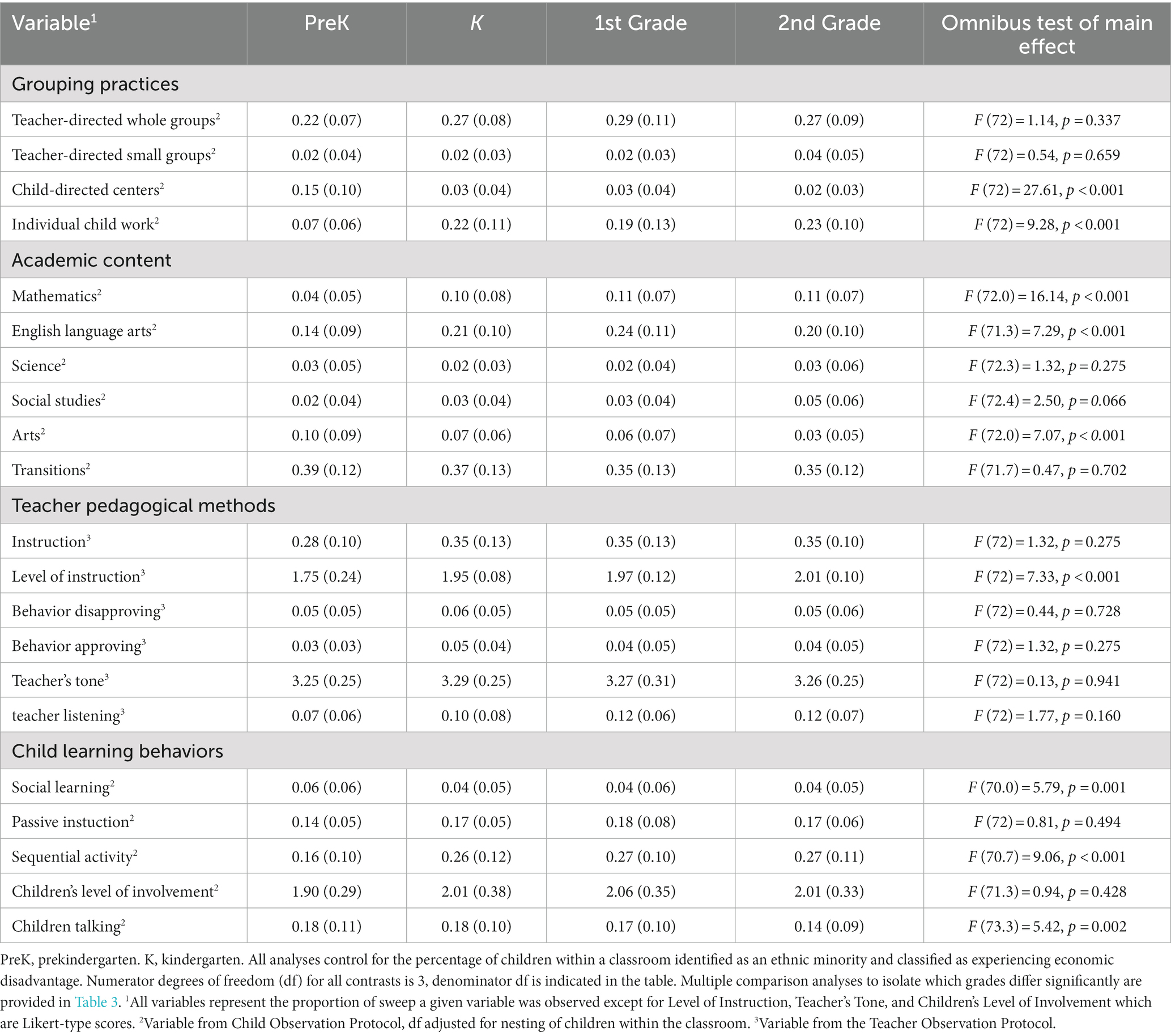

Descriptive statistics (presented in Table 2) revealed that, across grades, over a third of the day is spent in transitions, with average time in transitions ranging from 35 to 39%. Another third of the day is spent in instruction, with the lowest amount in PreK (28%). Most of the time spent in instruction was driven by teacher-directed whole groups, with much spent in passive instruction.

Table 2. Classroom practices and behaviors means (standard deviations) and tests of main effect of grade.

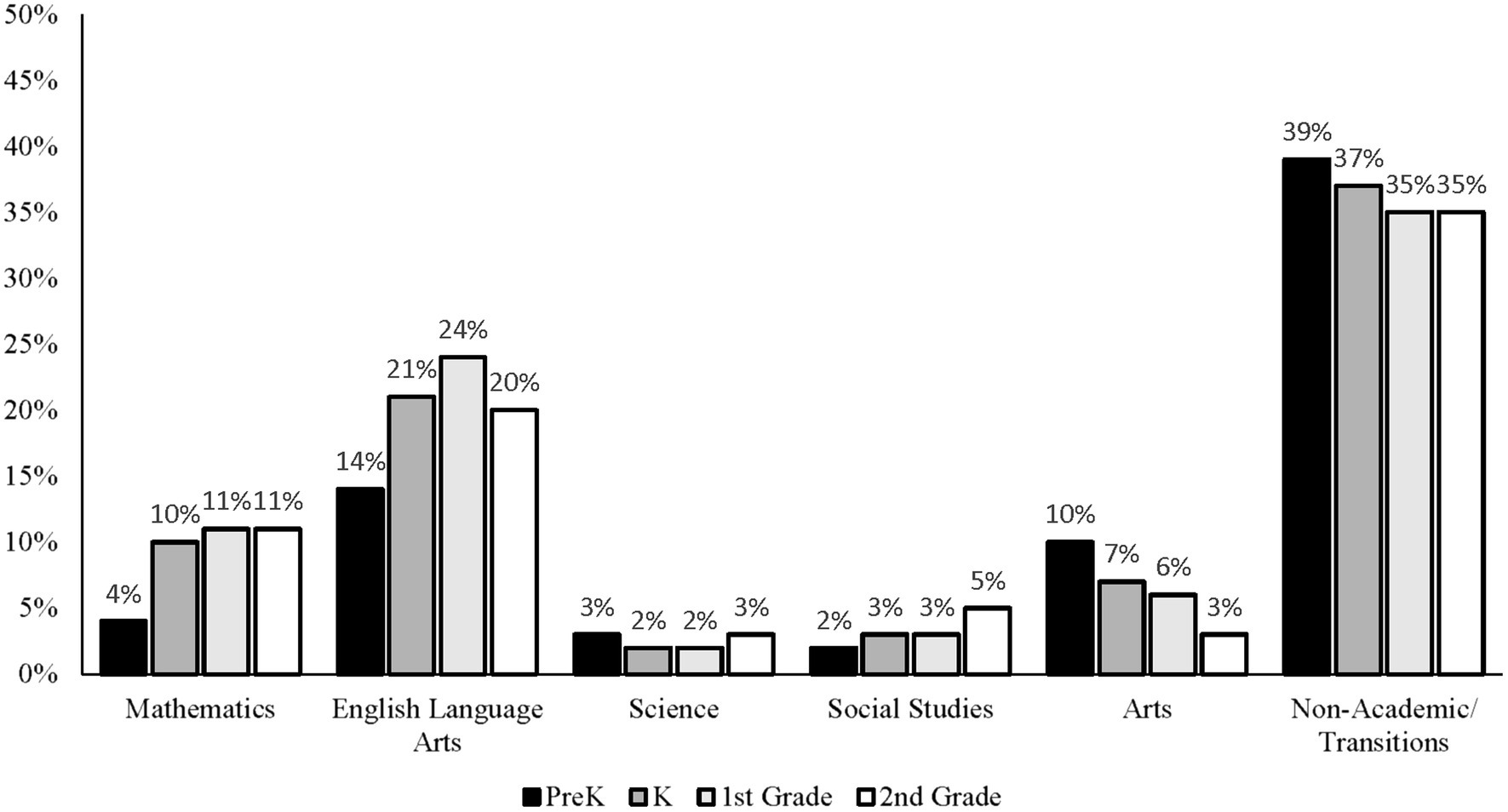

In terms of academic content, the most common focus was on ELA. In fact, in K through 2nd grade, students spent 20% or more of their time focused on ELA. The amount of science and social studies content was small and stable across each grade.

When instruction was happening, the level of instruction was typically at basic skills, with the lowest level of instruction occurring in PreK. Teachers’ behavior approving, disapproving, and tone are stable across the grades, with tone ratings hovering between flat and pleasant. Finally, children’s level of involvement across the grades was mildly engaged to engaged.

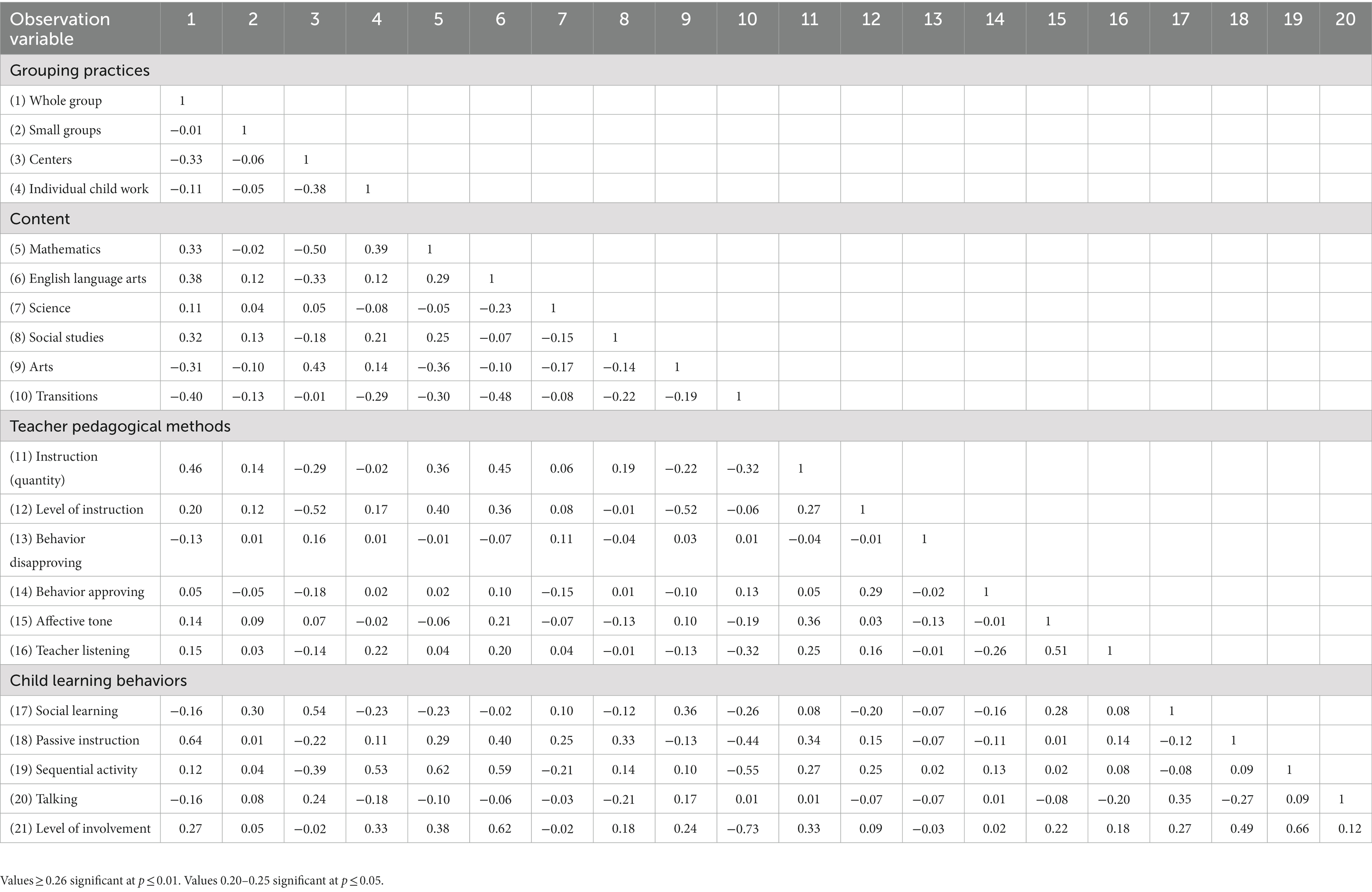

Correlations among study variables indicate a strong relationship between time spent in whole group and passive instruction (r = 0.64***). Level of involvement was highly correlated with ELA content (r = 0.62***) and sequential activities (r = 0.66***) and was negatively associated with time in transitions (r = −0.73***). There was also a strong relationship between math content and sequential activities (r = 0.62***). Correlations are presented in Table 3.

3.1. Grade-level differences in learning experiences

3.1.1. Grouping practices

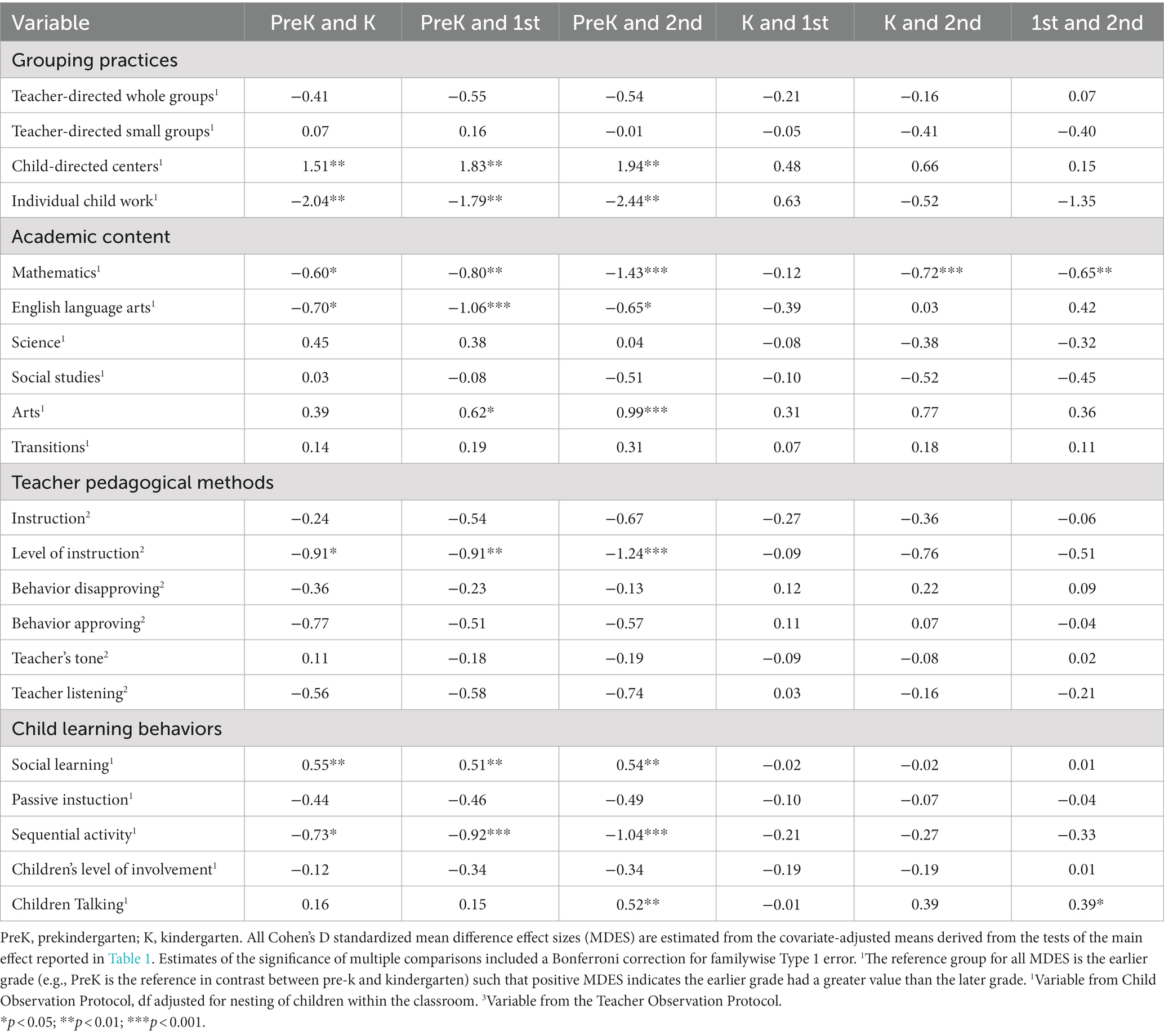

Descriptive statistics for the classroom practices indicate that, compared to the later grades, PreK students have less time in individual activities and more time in child-directed centers (see Table 2). In fact, individual work in K through 2nd grade was three times that of PreK, whereas students in K through 2nd grade were in child-directed centers for just 2–3% of the day as compared to PreK students, who spent 15% of the day in centers (see Figure 1). Multiple comparisons to highlight where significant differences emerge demonstrate that the largest differences between grades were between PreK and K, PreK and 1st, and PreK and 2nd grades, with effect sizes ranging from d = |1.51 to 2.44|. Differences between K and 1st, K and 2nd, and 1st and 2nd grades were not significant (see Table 4).

3.1.2. Academic content

Figure 2 shows academic content by grade. In terms of academic content, there were main effects of grade on the amount of math, ELA, and art, with a higher amount of math and ELA in K, 1st, and 2nd grade as compared to PreK, and a lower amount of art in grades after PreK. Multiple comparisons indicated that there were significant differences in the amount of math and ELA when comparing PreK and K, PreK and 1st, and PreK and 2nd grades. Among those differences, the largest was for the difference between the amount of time PreK students were engaged in math compared to 2nd-grade students (d = −1.43). If we contextualize this finding by summarizing differences in minutes (i.e., taking the average duration of the day for each grade and computing the proportion of the day in math for each grade level) PreK students spent an average of 15 min in math, whereas 2nd grade students spent over 45 min in math. In addition, there were significant differences in math for K (41 min) as compared to 2nd grade and for 1st grade (46 min) as compared to 2nd grade (d = −0.72 and − 0.65, respectively). The differences in the amount of art were significant comparing PreK to 1st grade (d = 0.62) and PreK to 2nd grade (d = 0.99), with PreK students spending over 37 min in art, 1st-grade students spending 25 min, and 2nd-grade students spending only 12 min in art.

3.1.3. Teacher pedagogical methods

Examination of cross-grade differences in teachers’ pedagogical methods resulted in few significant differences except for teachers’ level of instruction, which was higher in K, 1st, and 2nd grade compared to PreK. PreK students experienced lower levels of instruction compared to each of the other grades, with effect sizes ranging from d = −0.91 to −1.24.

3.1.4. Child learning behaviors

Finally, there were differences in children’s learning behaviors, including their social learning (i.e., the amount of associative and cooperative interactions), the amount of sequential activities, and the amount of child talking that was observed. PreK students spent significantly more time in social learning as compared to K, 1st, and 2nd grades, and less time in sequential activities. For child talking, PreK students talked significantly more compared to 2nd-grade students (d = 0.52), and 1st-grade students also talked more compared to 2nd-grade students (d = 0.39).

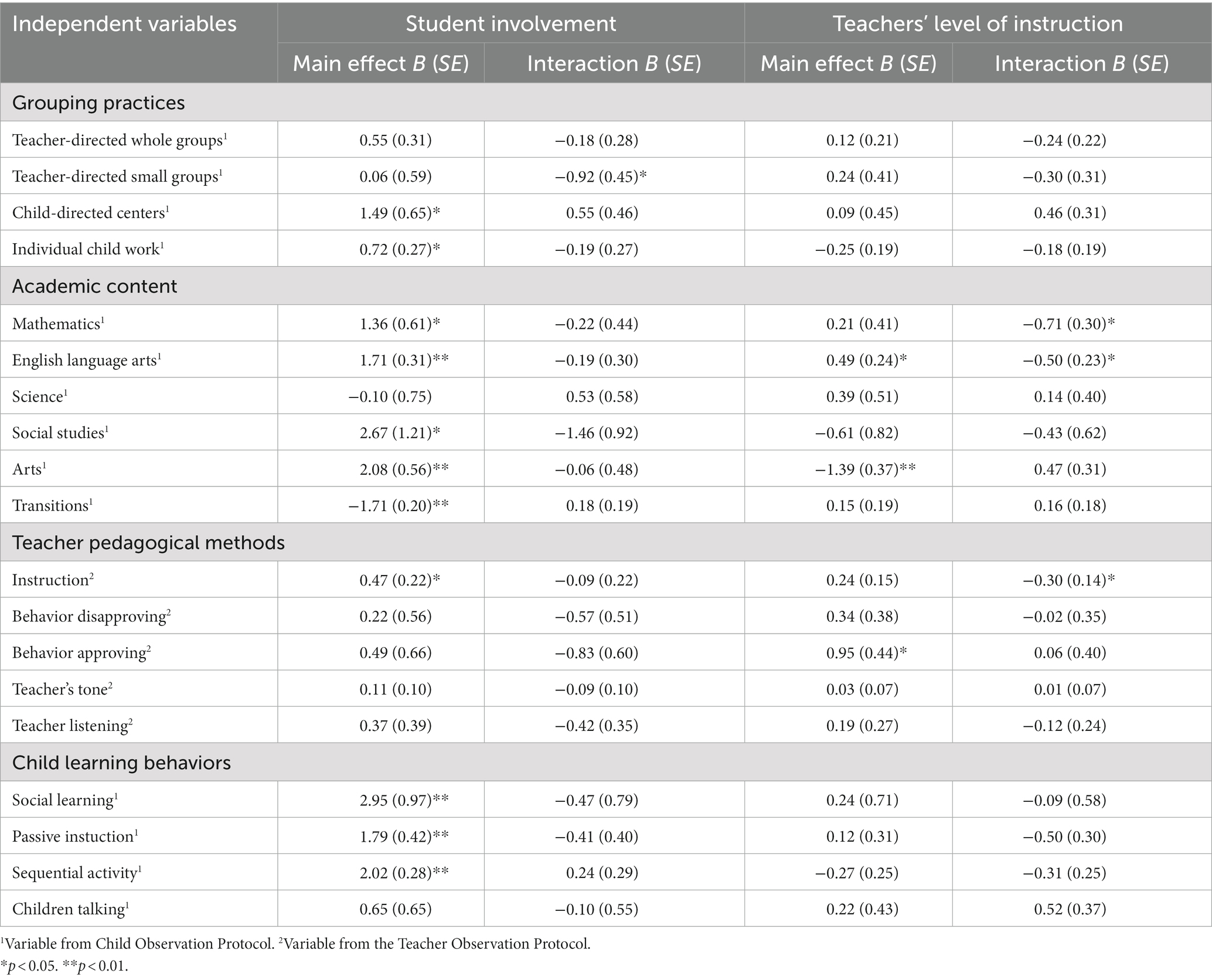

3.2. Associations with student involvement and teachers’ level of instruction

To further understand the grade level differences in learning experiences, our next aim was to explore the associations between the identified classroom practices and both student involvement and teachers’ level of instruction, which have been found to be predictive of children’s learning and developmental gains.

3.2.1. Main effects

Significant main effects revealed that across grade levels higher amounts of child-directed centers and individual work were associated with higher student involvement (B = 1.49, p = 0.026, and B = 0.72, p = 0.010). In terms of content, across all grades more math (B = 1.36, p = 0.028), ELA (B = 1.71, p < 0.001), social studies (B = 2.67, p = 0.030), art (B = 2.08, p < 0.001), and lower amounts of transitions (B = −1.71, p < 0.001) were associated with higher involvement. In addition, more teacher instruction was related to higher involvement (B = 0.47, p = 0.038). Finally, more time in social learning (B = 2.95, p = 0.003) and sequential activities (B = 2.02, p < 0.001) was associated with higher involvement regardless of grade level. Passive instruction was also associated with greater student involvement (B = 1.79, p < 0.001), but to a lesser degree than social learning and sequential activities. See Table 5 for full results.

Table 5. Tests of grade as a moderator of the effect of classroom practices on student involvement and teachers’ level of instruction.

There were main effects of ELA, art, and behavior approving on teachers’ level of instruction, such that across all grade levels more ELA instruction (B = 0.49, p = 0.043), less art (B = −1.39, p < 0.001), and more behavior approving (B = 0.95, p = 0.034) were associate with the level of instructional quality observed. While the amount of ELA instruction was associated with quality (i.e., teachers who did more ELA instruction tended to do higher quality instruction), the relations for math, science, and social studies were not significant (e.g., there was no relation between how much math instruction was observed and the quality).

3.2.2. Grade level moderation

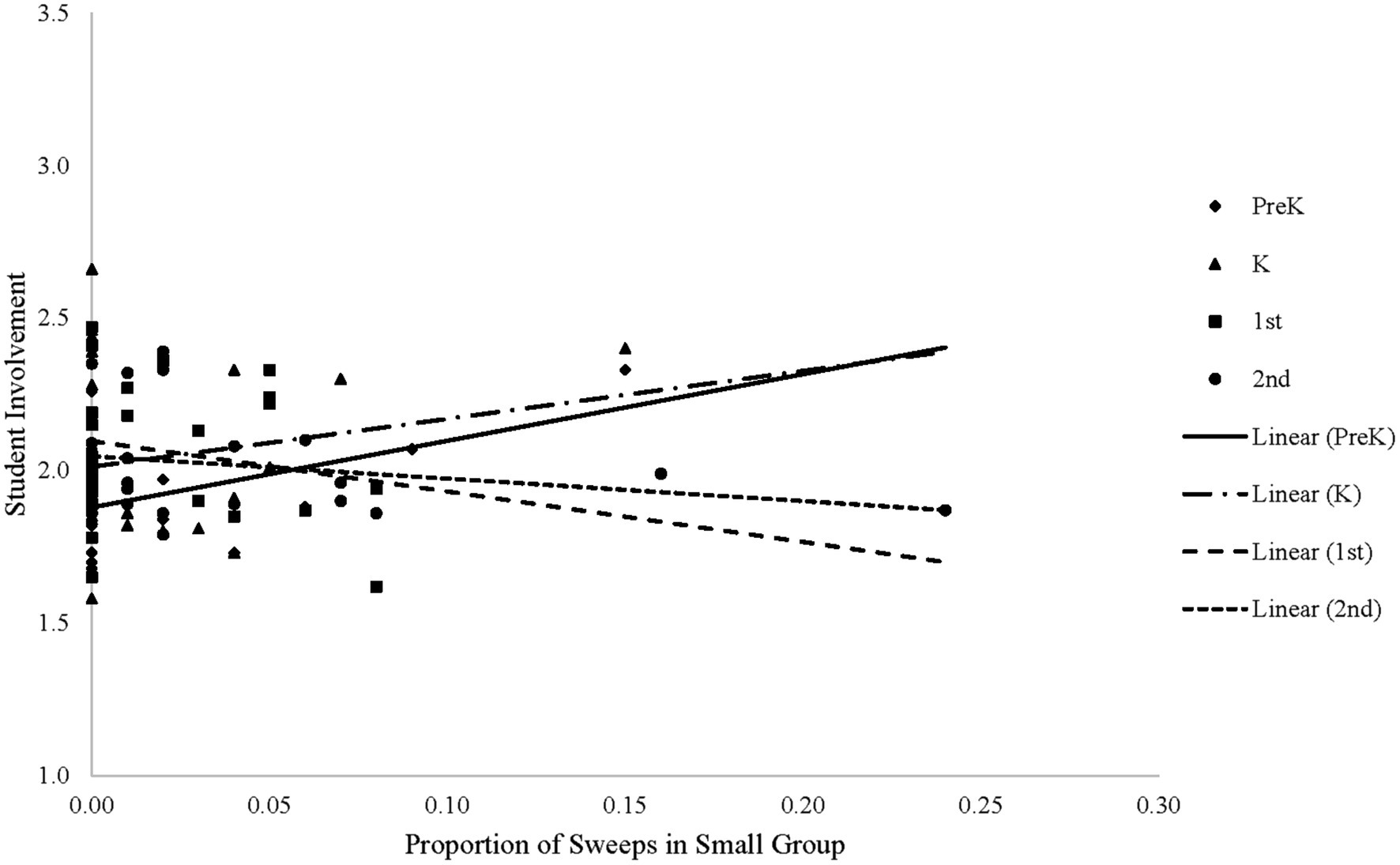

We conducted moderator analyses to determine whether grade moderated the relationship between classroom practices and two key predictors of students’ learning: student involvement and teachers’ level of instruction. While several of the classroom practices were predictive of student involvement, only one significant interaction emerged. Students in higher grades who spent more time in teacher-directed small groups had lower involvement, whereas students in early grades (PreK and K) had higher involvement if they had more time in teacher-directed small groups (B = −0.92, p = 0.043, see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Interaction of grade and the proportion of sweeps in small group predicting student involvement. Each dot represents an individual classroom. Small groups were positively related to students’ level of involvement in prekindergarten (R2 = 0.13) with greater usage of small groups associated with greater student involvement. The relation was not significant for Kindergarten (R2 = 0.04), 1st Grade (R2 = 0.03), and 2nd Grade (R2 = 0.05). The possible range of involvement ratings is 0–4.

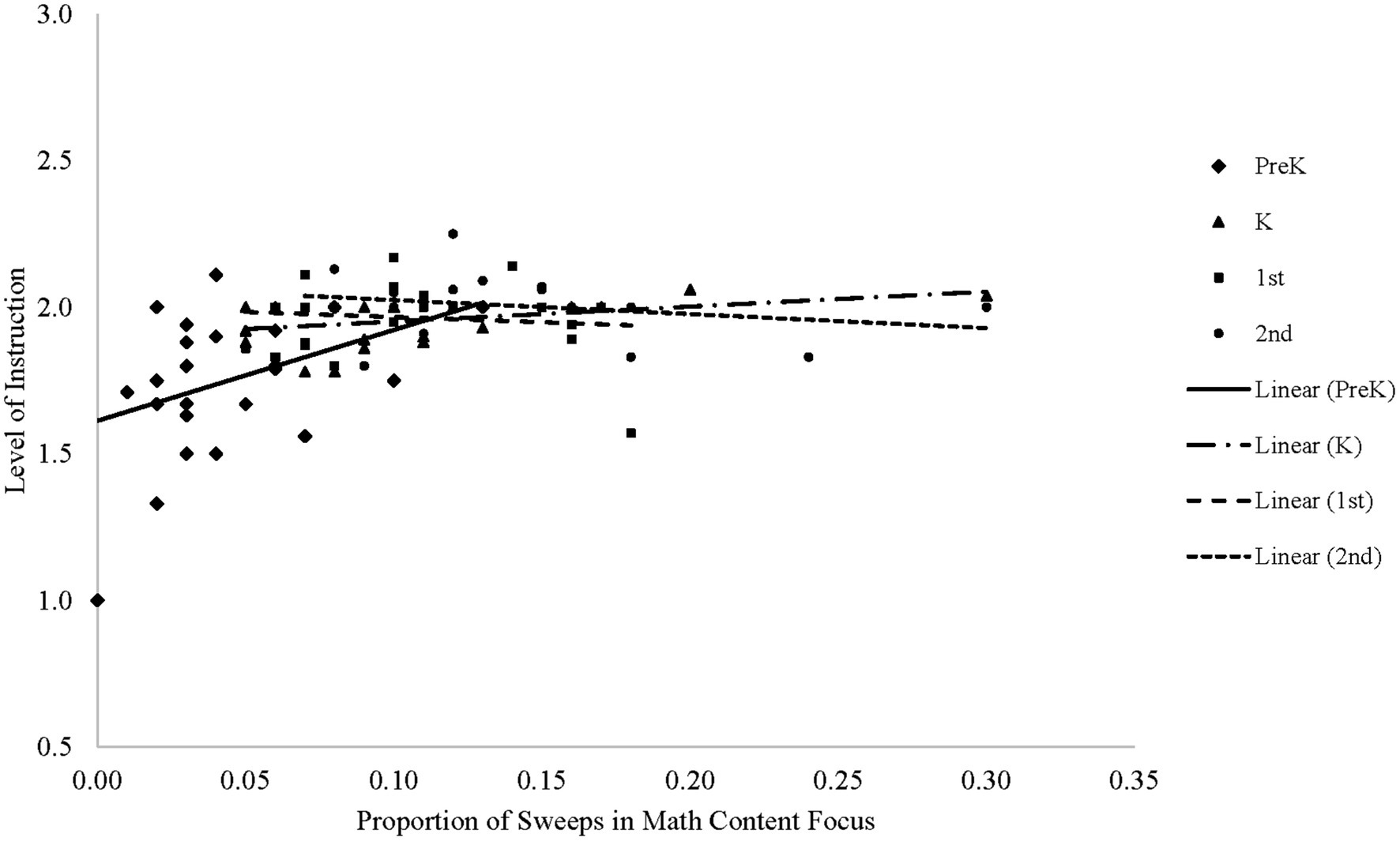

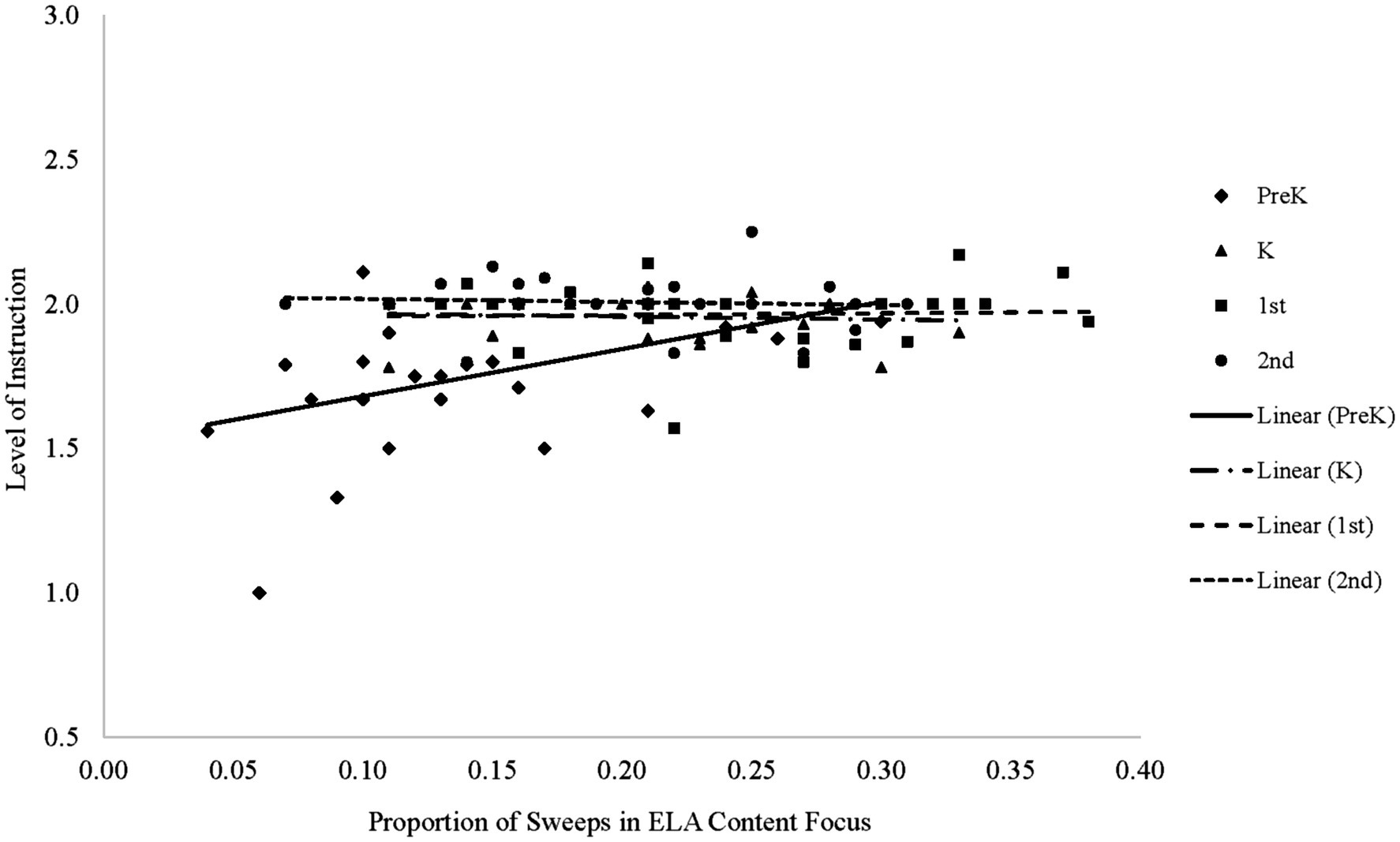

Results revealed three significant interactions of classroom practices by grade predicting level of instruction, two under the academic content grouping and one under pedagogical methods. Students in lower grades that experienced more math showed higher levels of instruction, and students in lower grades that experienced less math experience lower levels of instruction (B = −0.71, p = 0.021). A plot of the proportion of math and level of instruction by grade reveals that this result is largely driven by PreK (see Figure 4). In addition, students in lower grades that experienced more ELA had higher levels of instruction (B = −0.50, p = 0.030). Similarly, this finding seems to be driven by PreK (see Figure 5). Finally, while there was no main effect of amount of instruction on level of instruction, a significant interaction revealed that students in PreK that received less instruction had lower-level instruction (B = −0.30, p = 0.039, see Figure 6).

Figure 4. Interaction of grade and the proportion of sweeps in math content focus predicting teachers’ level of instruction. Each dot represents an individual classroom. Math content was positively related to the teacher’s level of instruction in prekindergarten (R2 = 0.13) and kindergarten (R2 = 0.14) with classrooms observed with more math content having higher levels of instructional quality. The relation was not significant for 1st Grade (R2 = 0.01) and 2nd Grade (R2 = 0.06). The possible range of level of instruction ratings is 0–4.

Figure 5. Interaction of grade and the proportion of sweeps in ELA content focus predicting teachers’ level of instruction. Each dot represents an individual classroom. English Language Arts (ELA) content was positively related to the teacher’s level of instruction in prekindergarten (R2 = 0.18) with classrooms observed in more ELA content having higher levels of instructional quality. The relation was not significant for Kindergarten (R2 = 0.01), 1st Grade (R2 < 0.01), or 2nd Grade (R2 < 0.01). The possible range of level of instruction ratings is 0–4.

Figure 6. Interaction of grade and the proportion of sweeps in which the teacher was instructing predicting teachers’ level of instruction. Each dot represents an individual classroom. The amount of overall instruction was positively related to teacher’s level of instruction in prekindergarten (R2 = 0.11) with classrooms observed in more instruction having higher levels of instructional quality. The relation was not significant for Kindergarten (R2 < 0.01), 1st Grade (R2 = 0.04), and 2nd Grade (R2 = 0.02). The possible range of level of instruction ratings is 0–4.

4. Discussion

The present study extends the current understanding of the instructional experiences in PreK through 2nd grade through a cross-sectional grade-level comparison of aspects of grouping practices, academic content, teachers’ pedagogical methods, and children’s learning behaviors. We intend this work’s foundational descriptive understanding of U.S. students’ classroom experiences in the early grades to inform ongoing efforts to coordinate standards, curricula, and instructional practices across PreK to 3rd grade (e.g., Bogard and Takanishi, 2005 Stipek et al., 2017 Kauerz, 2018). We used a behavioral-based observational system to collect detailed data across the full school day. This system is designed to capture the behaviors of all members of the classroom. Moreover, the study’s exploration of associations between various aspects of learning experiences, children’s level of involvement, and teachers’ instructional quality provides initial insights into the potential appropriateness and effectiveness of various grouping practices, academic content, teachers’ pedagogical methods, and children’s behaviors across PreK to 2nd grade.

4.1. Grouping practices, passive instruction, and social learning

In line with prior research (e.g., Vitiello et al., 2020 Justice et al., 2021), we found that whole group instruction was the most common grouping practice consistently across all grades with approximately a quarter of the day spent in this mode of instruction. A common characteristic of whole group instruction is the presence of didactic, passive instruction which aligns with the finding that students across all grade levels were most likely to be observed engaged in passive learning. While whole-group instruction was common across all grades, there was a noticeable grade-level difference between the grouping practices used for child-directed activities. In PreK, centers that allow for interactions with other students were more often observed than individual child work (e.g., desk work) while the opposite pattern was observed for K, 1st, and 2nd grade. The shift from centers to individual student work aligns with an observed decrease in social learning interactions from PreK to K. This shift away from center-based instruction where children typically have agency in hands-on learning in K aligns with the prior work of Justice et al. (2021) which found that the instructional practices of K classrooms resembled 1st and 2nd grade more than they resembled PreK.

It is currently an open question as to the optimal use of child-directed learning and teacher-directed instruction. Yet, it is important to acknowledge the wealth of evidence as to the benefits of active learning where students are directly contributing to their learning (Schwan and Riempp, 2004; Hausmann and Van Lehn, 2007; Roscoe and Chi, 2007; DeCaro and Rittle-Johnson, 2012; Yannier et al., 2021; Skene et al., 2022) and social learning where students collaborate with peers and teachers (Ladd, 1990; Wentzel, 1999; Hargrave and Sénéchal, 2000; Ramani, 2012; Montroy et al., 2014; Nesbitt et al., 2015; Christopher and Farran, 2020). We also found that across grade levels centers and social learning was significantly related to higher rates of student involvement, with effects being more robust compared to whole group and passive engagement, respectively. While active and social learning can occur across content areas and groupings, findings that whole-group and passive instruction dominate the learning experiences in the early grades raise important questions about the appropriateness of current instructional approaches.

4.2. Academic content and quality

Regarding the content that is being taught, consistent with prior research (e.g., Justice et al., 2021), across grade levels most learning experiences were dedicated to English language arts. Language arts were observed approximately twice as often as mathematics and even more so compared to science and social studies which occurred minimally across grades. Like grouping practices, comparisons of grade levels showed a dichotomy between PreK learning experiences compared to K, 1st, and 2nd grade. The proportion of the observation dedicated to language arts and math was significantly lower in PreK.

Our findings provide further support for the need to consider the appropriateness of a heightened focus on constrained academic skills in PreK and K (Gullo and Hughes, 2011; Alford et al., 2016; Bassok et al., 2016; Markowitz and Ansari, 2020) as it might not be developmentally appropriate, lead to redundancy in content being taught from year to year, and reduce students’ motivation for school (Farran and Lipsey, 2015; Cohen-Vogel et al., 2021; McCormick et al., 2021; Burchinal et al., 2022). The need for longitudinal research on the appropriate sequence of the specific content being taught (i.e., not just the indication that a given type of content is occurring) across the early grades is much needed as there are demonstrated associations between the amount of instruction on a given content area and learning gains in that content area (e.g., Connor et al., 2006; Donat and Donat, 2006; Wang, 2010; Christopher and Farran, 2020), and as this study demonstrated mathematics, language arts, social studies, and art content from PreK to 2nd grade were all positively associated with student involvement.

It is also important to consider the quality with which the content is being delivered by teachers and received by children. We found that the overall level of instruction provided by teachers was lower in PreK (e.g., more focus on basic skills and less focus on inferential thinking) compared to K, 1st, and 2nd grade, which did not differ. Similarly, children were less likely to be observed engaging in goal-directed learning experiences in PreK compared to all other grades. As the quality (Hill et al., 2007; Mashburn et al., 2008; Baumert et al., 2010; Kunter et al., 2013; Tompkins et al., 2013; Chen and Liang, 2017) and cognitive expectations (e.g., Nesbitt et al., 2015; Cheung and McBride, 2017; Farran et al., 2017; Christopher and Farran, 2020) of instruction are related to children’s learning, future work examining the coordination and alignment of early grades’ standards, curricula, and instructional practices must consider not only what content is being present but how the content is delivered to support deep understanding and content expertise.

4.3. Classroom emotional climate

Examination of the elements of the emotional climate of the classroom found that there was little variability in teachers’ use of positive techniques to engage children in learning (i.e., positive tone and behavior approval) and their disapproval of children’s behaviors across grade levels. This was a departure from prior work that found the positive emotional environment tended to be higher in 1st grade than in subsequent grades (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2005). Across grades, teachers in the study were observed showing a neutral affect (e.g., showing no expression or little indication of positive interest or excitement), and this coincided with slightly fewer observations of behavior approving compared to behavior disapproving and low amounts of teachers listening. The emotional climate of a classroom is associated with students’ learning and development in PreK and kindergarten (Pianta et al., 2005, 2008; Early et al., 2007; O’Connor, 2010; Christopher and Farran, 2020), and there are established associations between emotions and cognitions across the lifespan (e.g., Fredrickson, 2001, 2013; Blair, 2002; Phillips et al., 2002; Diamond and Ling, 2016). Future research is needed to understand how the emotional climate of the classroom contributes to the coordination of instructional experiences across the early grades.

4.4. Limitations and future directions

It is important to note the limitations of the present study. First, our data are cross-sectional. The study was initially designed as longitudinal, with researchers planning to collect additional classroom observations in the spring along with end-of-year student assessments. This would have allowed us to explore causal relationships. Unfortunately, with the onset of COVID-19, we had to suspend data collection and explore descriptive analyses and associations of classroom practices with students’ involvement and teachers’ level of instruction rather than testing causal relationships. Moreover, with a longitudinal design involving two or more time points for data collection, we could have tested the direction of effects. It may be that key practices lead to greater student involvement, or that the level of instruction moderates the effects of classroom practices on student involvement. Despite this limitation, the present study provides evidence that several classroom practices are associated with greater student engagement and teachers’ level of instruction.

In addition, we were not able to look at the effects of either the focal practices or student involvement and level of instruction on students’ learning and achievement. Without assessments collected over time, we were not able to gauge whether particular teacher behaviors are more likely to bring about positive outcomes (greater assessment gains) for students and whether these vary across the early grades.

It is also important to note that while we found that children across the early grades spend a significant amount of time in whole group activities, we should not assume that whole group is inherently bad. Experiential learning can happen in any activity grouping. However, we also know from the literature that level of instruction (Cerezci, 2020) and student involvement (Reyes et al., 2012; Roorda et al., 2017; Lei et al., 2018) are consistently predictive of positive outcomes, including academic achievement. And, while our observation data do not allow us to determine whether experiential learning was happening during whole group, we do know that involvement tends to be lower in whole group settings as compared to child-directed activities (e.g., Qi and Kaiser, 2004). The field would benefit from future research focused on exploring indicators of the quality and focus of instruction in the different grouping activities to help educators maximize the instructional experiences for students in the early grades and to determine how these experiences may look different from one grade to the next.

In addition to exploring specific questions related to continuity across the early grades, more broadly this study highlights the benefits of establishing research-practice partnerships (RPPs) in education, which provide an infrastructure to produce sound and actionable evidence that is focused on issues that are of interest to the field (i.e., problems of practice). By partnering with the Tennessee Education Research Alliance and the Tennessee Department of Education, we designed a study to examine questions that are a priority for educators and have implications for policy and practice. Indeed, advocates point to the value of RPPs in promoting greater use of research to inform decision-making to improve child outcomes (e.g., Donovan, 2013). Future research built from shared goals within research-practice partnerships will be particularly important as we tackle questions about how to improve educational experiences for young children. In recent years, researchers have sought to understand the characteristics of effective RPPs (e.g., fostering trust, creating a shared language, etc.) to form guidance for new partnerships seeking to learn from existing partnerships (Coburn and Penuel, 2016; Wentworth et al., 2017). Thus, to maximize the potential of RPPs to lead to positive change, there should also be ongoing work focused on defining best practices in these partnerships.

5. Conclusion

In summary, the learning experiences observed in the present study are consistent with other recent work examining learning experiences across the early grades in the U.S. The findings indicate that across the PreK to Grade 2 instruction tends to focus on basic skills provided in whole-class groupings that elicit passive participation from students. Across all grades, there was a predominant focus on language arts. These learning experiences are similar to observations made of 1st and 3rd-grade classrooms at the beginning of the century (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2002, 2005) and provide further support for the need to consider the appropriateness of pushing down the academic demands typical to 1st grade into PreK and K classrooms in the U.S. (Alford et al., 2016; Bassok et al., 2016; Markowitz and Ansari, 2020). Overall, the findings presented here extend the current literature by providing rich data to understand the experiences of children in the early grades. These findings provide a foundation for considering how instructional practices are coordinated over the early grades and indicate a need for not only the creation of standards, curriculum, and policies founded on the science of how children learn but also support for educators to effectively implement developmentally appropriate learning experiences across the early school years.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset is kept by the Principal Investigator for internal use. The PI will review data requests on a case-by-case basis prior to making the data available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Y2Fyb2xpbmUuaC5jaHJpc3RvcGhlckBnbWFpbC5jb20=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Vanderbilt University Internal Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because research involved normal educational practices that are not likely to adversely impact students’ opportunity to learn required educational content or the assessment of educators who provide instruction.

Author contributions

CC: Writing – original draft. KN: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (UWSC10509 and OPP1195942) awarded to CC.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through a grant awarded to CC with conceptual contributions from Dale C. Farran. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Gates Foundation. Special contributions were provided by Rachel Kasul and Easton Stone Dawson to the implementation of the project. The greatest appreciation is also extended to the administrators, teachers, families, and children who opened their schools and classrooms to us.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alford, B., Rollins, K., Padrón, Y., and Waxman, H. (2016). Using systematic classroom observation to explore student engagement as a function of teachers’ developmentally appropriate instructional practices (DAIP) in ethnically diverse prekindergarten through second-grade classrooms. Early Childh. Educ. J. 44, 623–635. doi: 10.1007/s10643-015-0748

Bailey, D., Duncan, G. J., Odgers, C., and Yu, W. (2017). Persistence and fadeout in the impacts of child and adolescent interventions. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 10, 7–39. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2016.1232459

Baines, E., Blatchford, P., and Kutnick, P. (2003). Changes in grouping practices over primary and secondary school. Int. J. Educ. Res. 39, 9–34. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00071-5

Bassok, D., Latham, S., and Rorem, A. (2016). Is kindergarten the new first grade? AERA Open 2, 233285841561635–233285841561631. doi: 10.1177/2332858415616358

Baumert, J., Kunter, M., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Voss, T., Jordan, A., et al. (2010). Teachers’ mathematical knowledge, cognitive activation in the classroom, and student progress. Am. Educ. Res. J. 47, 133–180. doi: 10.3102/0002831209345157

Blair, C. (2002). School readiness: integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. Am. Psychol. 57, 111–127. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.2.111

Bloom, H. S., Hill, C. J., Black, A. R., and Lipsey, M. W. (2008). Performance trajectories and performance gaps as achievement effect-size benchmarks for educational interventions. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 1, 289–328. doi: 10.1080/19345740802400072

Bogard, K., and Takanishi, R. (2005). PK–3: an aligned and coordinated approach to education for children 3 to 8 years old. Soc. Policy Rep. 19, 1–24. doi: 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2005.tb00044.x

Bronson, M. (1994). The usefulness of an observational measure of young children’s, social and mastery behaviors in early childhood classrooms. Early Childh. Res 9, 19–43. doi: 10.1016/0885-2006(94)90027-2

Burchinal, M. (2018). Measuring early care and education quality. Child Dev. Perspect. 12, 3–9. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12260

Burchinal, M., Foster, T., Garber, K., Cohen-Vogel, L., Bratsch-Hines, M., Peisner-Feinberg, E., et al. (2022). Examining three hypotheses for pre-kindergarten fade-out. Devel. Psychol. 58, 453–469. doi: 10.1037/dev0001302

Cadima, J., Doumen, S., Verschueren, K., and Buyse, E. (2015). Child engagement in the transition to school: contributions of self-regulation, teacher–child relationships and classroom climate. Early Childh. Res. Q. 32, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.01.00

Cerezci, B. (2020). The impact of the quality of early mathematics instruction on mathematics achievement outcomes. J. Childh Educ. Soc. 1, 216–228. doi: 10.37291/2717638X.20201248

Chen, J., and Liang, X. (2017). Teachers’ literal and inferential questions and children’s responses: a study of teacher-child linguistic interactions during whole-group instruction in Hong Kong kindergarten classrooms. Early Childh. Educ. 45, 671–683. doi: 10.1007/s10643-016-0807-9

Chetty, R., Friedman, J., Hilger, N., Saez, E., Schanzenbach, D., and Yagan, D. (2011). How does your kindergarten classroom affect your earnings? Evidence from project STAR. Q. J. Econ. 126, 1593–1660. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjr041

Cheung, S. K., and McBride, C. (2017). Effectiveness of parent–child number board game playing in promoting Chinese kindergarteners’ numeracy skills and mathematics interest. Early Educ. Dev. 28, 572–589. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2016.1258932

Christopher, C., and Farran, D. (2020). Academic gains in kindergarten related to eight classroom practices. Early Childh. Res. Q. 53, 638–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.07.001

Claessens, A., Engel, M., and Curran, F. C. (2014). Academic content, student learning, and the persistence of preschool effects. Am. Educ. Res. J. 51, 403–434. doi: 10.3102/0002831213513634

Coburn, C. E., and Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education: outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Res. 45, 48–54. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16631750

Cohen-Vogel, L., Little, M., Jang, W., Burchinal, M., and Bratsch-Hines, M. (2021). A missed opportunity? Instructional content redundancy in pre-K and kindergarten. AERA Open 7, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/233285842110061

Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., and Slominski, L. (2006). Preschool instruction and children’s emergent literacy growth. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 665–689. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.665

DeCaro, M. S., and Rittle-Johnson, B. (2012). Exploring mathematics problems prepares children to learn from instruction. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 113, 552–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.06.009

Diamond, A., and Ling, D. S. (2016). Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Dev. Cogn. Neuros. 18, 34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.11.005

Donat, D., and Donat, D. (2006). Reading their way: a balanced approach that increases achievement. Read. Writ. Q. 22, 305–323. doi: 10.1080/10573560500455745

Donovan, M. S. (2013). Generating improvement through research and development in educational systems. Science 340, 317–319. doi: 10.1126/science.1236180

Durden, T., and Dangel, J. (2008). Teacher-involved conversations with young children during small group activity. Early Years 28, 251–266. doi: 10.1080/09575140802393793

Durkin, K., Lipsey, M. W., Farran, D. C., and Wiesen, S. E. (2022). Effects of a statewide pre-kindergarten program on children’s achievement and behavior through sixth grade. Dev. Psychol. 58, 470–484. doi: 10.1037/dev0001301

Early, D. M., Iruka, I. U., Ritchie, S., Barbarin, O. A., Winn, D. M. C., Crawford, G. M., et al. (2010). How do pre-kindergarteners spend their time? Gender, ethnicity, and income as predictors of experiences in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childh. Res. Q. 25, 177–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.10.003

Early, D., Maxwell, K. L., Burchinal, M., Bender, R. H., Henry, G. T., Iriondo-Perez, J., et al. (2007). Teachers’ education, classroom quality, and young children’s academic skills: results from seven studies of preschool programs. Child Dev. 78, 558–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01014.x

Engel, M., Jacob, R., Claessens, A., and Erickson, A. (2021). Kindergarten in a large Urban District. Educ. Res. 50, 401–415. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211041586

Farran, D. C., Kasul, R. A., and Anthony, K. (2019a). Teacher observation protocol: primary grades (pre K to grade 2 adaptation) Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Farran, D. C., Kasul, R. A., and Anthony, K. (2019b). Child observation protocol: primary grades (pre K to grade 2 adaptation). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University.

Farran, D. C., and Lipsey, M. W. (2015). Expectations of sustained effects from scaled up pre-K: challenges from the Tennessee study (evidence speaks reports, Vol. 1, #3). Brookings institution. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/expectations-of-sustained-effects-from-scaled-up-pre-k-challenges-from-the-tennessee-study/

Farran, D., Meador, D., Christopher, C., Nesbitt, K., and Bilbrey, L. (2017). Data driven quality in prekindergarten classrooms: a partnership between developmental scientists and an urban district. Child Dev. 88, 1466–1479. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12906

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., and Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. of Educ. Res. 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. (2013). Updated thinking on positivity ratios. Am. Psychol. 68, 814–822. doi: 10.1037/a0033584

Fuligni, A. S., Howes, C., Huang, Y., Hong, S. S., and Lara-Cinisomo, S. (2012). Activity settings and daily routines in preschool classrooms: diverse experiences in early learning settings for low-income children. Early Childh. Res. Q. 27, 198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.10.001

Fuller, B., Bein, E., Bridges, M., Kim, Y., and Rabe-Hesketh, S. (2017). Do academic preschools yield stronger benefits? Cognitive emphasis, dosage, and early learning. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 52, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.05.001

Goble, P., and Pianta, R. (2017). Teacher-child interactions in free choice and teacher-directed activity settings: Prediction to school readiness. Early Edu. Devel. 28, 1035–1051. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2017.1322449

Gonzalez, J. E., Pollard-Durodola, S., Simmons, D. C., Taylor, A. B., Davis, M. J., Fogarty, M., et al. (2014). Enhancing preschool children’s vocabulary: effects of teacher talk before, during and after shared reading. Early Childh. Res. Q. 29, 214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.11.001

Gormley, W. T. Jr., Gayer, T., Phillips, D., and Dawson, B. (2005). The effects of universal pre–K on cognitive development. Dev. Psychol. 41, 872–884. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.872

Gullo, D. F., and Hughes, K. (2011). Reclaiming kindergarten: part I. Questions about theory and practice. Ear. Child. Educ. J. 38, 323–328. doi: 10.1007/s10643-010-0429-6

Hargrave, A. C., and Sénéchal, M. (2000). A book reading intervention with preschool children who have limited vocabularies: the benefits of regular reading and dialogic reading. Early Childh. Res. Q. 15, 75–90. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(99)00038-1

Hausmann, R., and Van Lehn, K. (2007). Self-explaining in the classroom: learning curve evidence. Proceedings of the 29th annual conference of the cognitive science society (pp. 1067–1072). Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum

Hill, H. C., Ball, D. L., Blunk, M., Goffney, I. M., and Rowan, B. (2007). Validating the ecological assumption: the relationship of measure scores to classroom teaching and student learning. Measurement 5, 107–118. doi: 10.1080/15366360701487138

Hill, C. J., Gormley, W. T., and Adelstein, S. (2015). Do the short-term effects of a high-quality preschool program persist? Early Childh. Res. Q. 32, 60–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.12.005

Hollo, A., and Wehby, J. H. (2017). Teacher talk in general and special education elementary classrooms. Elem. School J. 117, 616–641. doi: 10.1086/691605

Justice, L. M., Jiang, H., Purtell, K. M., Lin, T. J., and Ansari, A. (2021). Academics of the early primary grades: investigating the alignment of instructional practices from pre-k to third grade. Early Educ. Dev. 33, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2021.1946762

Justice, L., Jiang, H., and Strasser, K. (2018). Linguistic environment of preschool classrooms: what dimensions support children’s language growth? Early Childh. Res. Q. 42, 79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.09.003

Kauerz, K. A. (2018). “Alignment and coherence as system-level strategies: bridging policy and practice” in Kindergarten transition and readiness. eds. A. Mashburn, J. LoCasale-Crouch, and K. Pears (Cham: Springer), 349–368.

Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., and Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: effects on instructional quality and student development. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 805–820. doi: 10.1037/a0032583

Ladd, G. W. (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: Predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Devel. 61, 1081–1100. doi: 10.2307/1130877

Ladd, G. W., and Dinella, L. M. (2009). Continuity and change in early school engagement: predictive of children’s achievement trajectories from first to eighth grade. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 190–206. doi: 10.1037/a0013153

Lei, H., Cui, Y., and Zhou, W. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 46, 517–528. doi: 10.2224/sbp.7054

McCormick, M., Weiland, C., Hsueh, J., Pralica, M., Weissman, A. K., Moffett, L., et al. (2021). Is skill type the key to the prek fadeout puzzle? Differential associations between enrollment in prek and constrained and unconstrained skills across kindergarten. Child Devel. 92, 599–620. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13520

Magnuson, K. A., Ruhm, C., and Waldfogel, J. (2007). The persistence of preschool effects: do subsequent classroom experiences matter? Early Childh. Res. Q. 22, 18–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.10.002

Markowitz, A. J., and Ansari, A. (2020). Changes in academic instructional experiences in head start classrooms from 2001–2015. Early Childh. Res. Q. 53, 534–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.06.008

Mascaerño, M., Snow, C. E., Deunk, M. I., and Bosker, R. J. (2016). Language complexity during read-alouds and kindergartners’ vocabulary and symbolic understanding. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 44, 39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2016.02.001

Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D., et al. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Dev. 79, 732–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x

McKay, M. J. (1988). Extended wait-time and its effect on the listening comprehension of kindergarten students. National Reading Conference Yearbook. 37, 225–233.

Montroy, J. J., Bowles, R. P., Skibbe, L. E., and Foster, T. D. (2014). Social skills and problem behaviors as mediators of the relationship between behavioral self-regulation and academic achievement. Early Childh. Res. Q. 29, 298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.03.002

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2020). Developmentally appropriate practice position statement. Available at: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. (2002). The relation of global first-grade classroom environment to structural classroom features and teacher and student behaviors. Elem. School J. 102, 367–387. doi: 10.1086/499709

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2005). A day in third grade: a large-scale study of classroom quality and teacher and student behavior. Elem. School J. 105, 305–323. doi: 10.1086/428746

Nesbitt, K. T., and Farran, D. C. (2021). Effects of prekindergarten curricula: tools of the mind as a case study. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child 86, 7–119. doi: 10.1111/mono.12425

Nesbitt, K. T., Farran, D. C., and Fuhs, M. W. (2015). Executive function skills and academic achievement gains in prekindergarten: contributions of learning-related behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 51, 865–878. doi: 10.1037/dev0000021

O’Connor, E. (2010). Teacher–child relationships as dynamic systems. J. School Psychol. 48, 187–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.01.001

Phillips, L. H., Bull, R., Adams, E., and Fraser, L. (2002). Positive mood and executive function: evidence from stroop and fluency tasks. Emotion 2, 12–22. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.2.1.12

Phillips, D., Lipsey, M. W., Dodge, K. A., Haskins, R., Bassok, D., Burchinal, M. R., et al. (2017). Puzzling it out: the current state of scientific knowledge on pre-kindergarten effects. A consensus statement. Brookings Institution. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/puzzling-it-out-the-current-state-of-scientific-knowledge-on-pre-kindergarten-effects/

Pianta, R. C., Belsky, J., Houts, R., and Morrison, F. (2007). Opportunities to learn in America’s elementary classrooms. Science 315, 1795–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.1139719

Pianta, R., Belsky, J., Vandergrift, N., Houts, R., and Morrison, F. (2008). Classroom effects on children’s achievement trajectories in elementary school. Am. Educ. Res. J. 45, 365–397. doi: 10.3102/0002831207308230

Pianta, R., Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Bryant, D., Clifford, R., Early, D., et al. (2005). Features of pre-kindergarten programs, classrooms, and teachers: do they predict observed classroom quality and child-teacher interactions? Appl. Dev. Sci. 9, 144–159. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0903_2

Ponitz, C. C., Rimm-Kaufman, S., Grimm, K. J., and Curby, T. W. (2009). Kindergarten classroom quality, behavioral engagement, and reading achievement. School Psychol. Rev. 38, 102–120. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2009.12087852

Portilla, X. A., Ballard, P. J., Adler, N. E., Boyce, W. T., and Obradovi’c, J. (2014). An integrative view of school functioning: transactions between self-regulation, school engagement, and teacher-child relationship quality. Child Dev. 85, 1915–1931. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12259

Qi, C. H., and Kaiser, A. P. (2004). Problem behaviors of low-income children with language delays: an observation study. J. Speech Lang. Hear. R. 47, 595–609. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/046)

Ramani, G. B. (2012). Influence of a playful, child-directed context on preschool children’s peer cooperation. Merrill Palmer Q. 58, 159–190. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2012.0011

Reyes, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., White, M., and Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 700–712. doi: 10.1037/a0027268

Robinson, K., and Mueller, A. S. (2014). Behavioral engagement in learning and math achievement over kindergarten: a contextual analysis. Am. J. Educ. 120, 325–349. doi: 10.1086/675530

Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). Affective teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: a meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychol. Rev. 46, 239–261. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3

Roscoe, R. D., and Chi, M. T. H. (2007). Understanding tutor learning: knowledge-building and knowledge-telling in peer tutors’ explanations and questions. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 534–574. doi: 10.3102/0034654307309920

Schwan, S., and Riempp, R. (2004). The cognitive benefits of interactive videos: learning to tie nautical knots. Learn. Instr. 14, 293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.06.005

Shonkoff, J., and Phillips, D. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: the science of early childhood development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Skene, K., O’Farrelly, C. M., Byrne, E. M., Kirby, N., Stevens, E. C., and Ramchandani, P. G. (2022). Can guidance during play enhance children’s learning and development in educational contexts? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Dev. 93, 1162–1180. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13730

Skinner, E. A., and Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. J. Educ. Psychol. 85, 571–581. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571

Stipek, D., Franke, M., Clements, D., Farran, D., and Coburn, C. (2017). PK-3: What does it mean for instruction? Social Policy Report. 30, 1–23. doi: 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2017.tb00087.x

Sonnenschein, S., Stapleton, L. M., and Benson, A. (2010). The relation between the type and amount of instruction and growth in children’s reading competencies. Am. Educ. Res. J. 47, 358–389. doi: 10.3102/0002831209349215

Tompkins, V., Zucker, T. A., Justice, L. M., and Binici, S. (2013). Inferential talk during teacher–child interactions in small-group play. Early Childh. Res. Q. 28, 424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.11.001

Vitiello, V. E., Pianta, R. C., Whittaker, J. E., and Ruzek, E. (2020). Alignment and misalignment of classroom experiences from pre-K to kindergarten. Early Childh. Res. Q. 52, 44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.06.014

Wang, A. H. (2010). Optimizing early mathematics experiences for children from low-income families: a study on opportunity to learn mathematics. Early Childh. Educ. J. 37, 295–302. doi: 10.1007/s10643-009-0353-0359

Watts, T., Duncan, R., and Davis-Kean, P. (2014). What’s past is prologue: relations between early mathematics knowledge and high school achievement. Educ. Res. 43, 352–360. doi: 10.3102/0013189X14553660

Weiland, C., Ulvestad, K., Sachs, J., and Yoshikawa, H. (2013). Associations between classroom quality and children’s vocabulary and executive function skills in an urban public prekindergarten program. Early Childh. Res. Q. 28, 199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.12.002

Weiland, C., Unterman, R., Shapiro, A., Staszak, S., Rochester, S., and Martin, E. (2020). The effects of enrolling in oversubscribed pre-kindergarten programs through third grade. Child Dev. 91, 1401–1422. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13308

Wentworth, L., Mazzeo, C., and Connolly, F. (2017). Research practice partnerships: a strategy for promoting evidence-based decision-making in education. Educ. Res. 59, 241–255. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2017.1314108

Wentzel, K. R. (1999). Social-motivational processes and interpersonal relationships: implications for understanding motivation at school. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 76–97. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.76

Williford, A., Maier, M., Downer, J., Pianta, R., and Howes, C. (2013). Understanding how children’s engagement and teachers’ interactions combine to predict school readiness. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 34, 299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2013.05.002