- Institute for Language Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

Introduction: One of the bilingual advantages often reported in the literature on typically-developing children involves advantages in foreign language learning at school. However, it is unknown whether similar advantages hold for bilingual pupils with learning disabilities. In this study, we compare the performance of monolingual and bilingual primary-school children with developmental language disorder (DLD) learning English as a school subject in special education schools in the Netherlands.

Methods: The participants were monolingual (N = 49) and bilingual (N = 22) children with DLD attending Grade 4−6 of special education (age 9–12). The bilingual participants spoke a variety of home languages. The English tests included a vocabulary task, a grammar test and a grammaticality judgement task. The Litmus Sentence Repetition Task and the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test were used as measures of, respectively, grammatical ability and vocabulary size in Dutch (majority/school language). In addition, samples of semi-spontaneous speech were elicited in both English and Dutch using the Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives. The narratives were analysed for fluency, grammatical accuracy, lexical diversity, and syntactic complexity. A questionnaire was used to measure amount of exposure to English outside of the classroom.

Results and discussion: The results for Dutch revealed no differences between monolinguals and bilinguals on the narrative measures, but monolinguals performed significantly better on both vocabulary and grammar. In contrast, bilinguals outperformed monolinguals on all English measures, except grammatical accuracy of narratives. However, some of the differences became non-significant once we controlled for amount of out-of-school exposure to English. This is the first study to demonstrate that foreign language learning advantages extend to bilingual children with DLD. The results also underline the need to control for differences in out-of-school exposure to English when comparing bilingual and monolingual pupils on foreign language outcomes.

Introduction

Being bilingual is more than just a sum of two languages, since bilingual development may be associated with additional benefits, including cognitive (Bialystok, 2017; Chamorro and Janke, 2022) and socio-emotional advantages (Sun et al., 2021). One of the bilingual benefits documented in the literature pertains to advantages in foreign language (FL) learning at school, also known as third language (L3) advantages (see review in Hirosh and Degani, 2018). There is indeed a growing body of evidence demonstrating that bilingual learners tend to outperform their monolingual peers in novel language learning (Thomas, 1988; Swain et al., 1990; Cenoz and Valencia, 1994; Lasagabaster, 2000; Sanz, 2000; Brohy, 2001; Sagasta Errasti, 2003; Clyne et al., 2004; Keshavarz and Astaneh, 2004; Abu-Rabia and Sanitsky, 2010; Rauch et al., 2011; Maluch et al., 2015, 2016; Mady, 2017; Maluch and Kempert, 2017; Hopp et al., 2019; Salomé et al., 2021). For example, in one of the first studies on this topic, Cenoz and Valencia (1994) focused on secondary school bilingual students learning L3 English in the Basque Country, where both the L1 and L2 (Basque and Spanish) are socially relevant and supported in schools. They used a composite score of English proficiency (comprising vocabulary, grammar, listening and reading comprehension, speaking and writing ability) and compared the performance of Spanish-Basque bilinguals and age-matched Spanish monolingual peers. The results revealed that bilinguals outperformed monolinguals, and the effect of bilingualism did not interact with other predictors (intelligence, age, SES, motivation, amount of instruction). Abu-Rabia and Sanitsky (2010) compared English skills of monolingual (Hebrew) and bilingual (Russian-Hebrew) sixth-graders after 3 years of English lessons. Whereas no differences in Hebrew (majority language) proficiency were found, the bilinguals outperformed the monolinguals on English (FL) vocabulary, grammar, reading and spelling. More recently, Hopp et al. (2019) found bilingual advantages in FL (English) vocabulary and grammar in German primary-school children speaking a minority language along with German. Proficiency in both the L1 and L2 predicted L3 English outcomes.

However, there are also studies that found no differences between monolingual and bilingual FL learners (Jaspaert and Lemmens, 1990; Sanders and Meijers, 1995; Schoonen et al., 2002; Edele et al., 2018; Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood, 2019; Lorenz et al., 2020), or even found that bilinguals were outperformed by their monolingual peers (Van Gelderen et al., 2003). For instance, Jaspaert and Lemmens (1990) measured L3 Dutch proficiency of Italian-French immigrant bilinguals in Brussels and compared it to that of French monolinguals. No significant group differences were found. Van Gelderen et al. (2003) compared English reading skills of Dutch monolinguals and immigrant bilinguals with various language backgrounds growing up in the Netherlands. Results showed that the Dutch monolinguals outperformed the bilinguals, which could be explained by the fact that the groups were not matched on SES. Edele et al. (2018) investigated English learning in German monolingual students and their Turkish-German or Russian-German bilingual peers. After controlling for social and cognitive factors, L3 advantages were found only for balanced bilinguals who had high proficiency levels in both the majority language (German) and the heritage language (Russian or Turkish).

Even though the literature on bilingual FL learning advantages is growing rapidly, evidence so far is limited to pupils with typical language development and it is unclear whether such advantages also extend to bilingual children with learning disabilities. This paper aims to address this gap by comparing English as a foreign language (EFL) skills of monolingual and bilingual children with developmental language disorder (DLD) attending special education schools in the Netherlands.

Bilingual FL learning advantages in pupils with typical language development

Bilingual advantages in learning novel languages have been attributed to both (i) direct transfer of previous language knowledge and skills and (ii) indirect effects of bilingualism, such as enhanced cognitive and metalinguistic skills (Hirosh and Degani, 2018). There is ample evidence that second language (L2) learning can be facilitated by positive transfer from the first language (L1) (Odlin, 1989; Zdorenko and Paradis, 2012; Siu and Ho, 2015; Van de Ven et al., 2018). For example, if a child knows how to talk about past events in Dutch (e.g., stop-stopte, eet-at), the acquisition of English past tense forms (e.g., stop-stopped, eat-ate) is facilitated (Blom and Paradis, 2015). Likewise, cognate words that are similar in form and meaning between the two languages (e.g., English apple and Dutch appel) are learned and retained more easily than noncognates (Sheng et al., 2016; Mulder et al., 2019). Bilinguals have two systems to transfer from, and are more likely to recognize more cognate words and similar grammatical constructions in a new language. This being said, it is still a matter of debate whether positive transfer is only possible from the language that is most similar to the L3 (Rothman, 2015) or whether both languages of a bilingual are available for transfer (Slabakova, 2017; Westergaard, 2021).

Although transfer has been given sufficient attention in the L3 literature, it cannot be the only source of L3 advantages. Importantly, stronger FL skills of bilinguals have also been reported in cases where the home language (Russian or Turkish) did not predict L3 outcomes, and where the bilinguals’ skills in the majority language (German or Dutch) were weaker than those of monolinguals (Hopp et al., 2019). Another potential source of L3 advantages pertains to the transfer of skills. For instance, early experience with two phonological systems appears to facilitate subsequent phonological learning later in life (Kaushanskaya and Marian, 2009). At the lexical level, young bilinguals are more likely to override the mutual exclusivity assumption because their vocabularies always contain double labels for the same concepts (Kalashnikova et al., 2015), which leads to higher flexibility in word learning (Hirosh and Degani, 2018). There is also evidence that bilinguals are better at suppressing interference from the previously acquired languages when learning a new language (Kaushanskaya et al., 2014), presumably due to their life-long training with inhibiting one of the languages.

Bilingual FL learning advantages have also been attributed to metalinguistic awareness, i.e., the ability to reflect on language structure and to see similarities and differences between languages. There is plenty of evidence that bilingualism is associated with enhanced metalinguistic skills (e.g., Jessner, 2006; Foursha-Stevenson and Nicoladis, 2011; Hofer and Jessner, 2019; Dolas et al., 2022). Rauch et al. (2011) found that biliterate children who could read and write in both German and Turkish had higher levels of metalinguistic awareness; metalinguistic awareness, in turn, predicted stronger L3 English skills. The finding that the mediation effect was partial reveals that enhanced metalinguistic awareness is only one of the mechanisms underlying bilingual advantages in FL learning.

Advantages in FL learning can also be due to enhanced language processing abilities resulting from more general cognitive benefits of bilingualism, including better developed executive control, working memory and attention (see reviews in Giovannoli et al., 2020; Monnier et al., 2022). A widely accepted explanation of this phenomenon is that bilinguals constantly hold two languages in mind and have to select one language while at the same time suppressing the other. This continuous cognitive practice presumably leads to increased attentional control and greater cognitive flexibility. Cognitive advantages have been reported for both simultaneous and sequential bilinguals, of high and low SES, with and without language disorders, acquiring typologically distant and genetically related languages (e.g., Engel de Abreu et al., 2012; Blom et al., 2014, 2017; Park et al., 2019; Hofweber et al., 2020; Treffers-Daller et al., 2020). However, there are also plenty of studies reporting no cognitive differences between monolinguals and bilinguals (e.g., Duñabeitia et al., 2014; Paap et al., 2015; Scaltritti et al., 2015; Blom et al., 2017). These conflicting findings may explain some of the controversy in the literature on linguistic advantages of bilingualism: if bilingual acceleration (partly) hinges on cognitive advantages and such advantages are not ubiquitous, this could explain why L3 advantages have been found in some populations but not in others. Bilingual groups that display advantages in cognitive skills are also likely to have advantages in novel language learning because cognitive skills play an important role in language acquisition. To give an example, bilingual advantages in orienting (Park et al., 2020) presumably make bilingual learners more efficient in attending to informative (e.g., grammatical or prosodic) cues in the input.

The mixed results in the L3 literature might also be due to differences between proficiency levels and varying ages of the participants in previous studies. For example, balanced bilinguals appear to be more likely to reap the benefits of bilingualism than children who have one dominant and one weaker language (Rauch et al., 2011; Edele et al., 2018). Bilingual advantages also appear stronger in primary-school children than in secondary-school pupils, probably due to the fact that monolinguals develop multilingual competence through FL lessons and gradually close the gap in the course of secondary education (Maluch et al., 2016; Hopp et al., 2019). Bilingual benefits are also more likely to be found in additive contexts (where both first languages are maintained, as in Spain or Canada) than in subtractive contexts (where L2 is acquired at the expense of L1) (Cummins, 2000). Other relevant factors that have been proposed in the literature to explain the controversial findings include typological proximity between L3 and the previously acquired languages (Swain et al., 1990; Schepens et al., 2016), levels of bilingual proficiency (Lasagabaster, 2000; Muñoz, 2000; Sagasta Errasti, 2003; Edele et al., 2018; Lorenz et al., 2020), language use in the home (Maluch et al., 2016), code-switching practices (Maluch and Kempert, 2017) and literacy in the home language (Swain et al., 1990; Keshavarz and Astaneh, 2004; Rauch et al., 2011).

Crucially, previous research on this topic appears to have overlooked one important variable – amount of FL exposure outside of school, also known as extracurricular or extramural exposure (Sundqvist, 2009). Specifically for English, there is robust evidence that out-of-school exposure is one of the strongest predictors of EFL proficiency (Lindgren and Muñoz, 2013; Sundqvist and Sylvén, 2016; De Wilde and Eyckmans, 2017; Peters, 2018; Puimège and Peters, 2019; De Wilde et al., 2020; Leona et al., 2021). Across Europe, the most frequent types of extramural exposure are listening to songs, watching videos and films, playing computer games and surfing the Internet (Sundqvist, 2009; Lindgren and Muñoz, 2013; Peters, 2018; Muñoz, 2020). It is then surprising that prior research comparing EFL performance of monolinguals and bilinguals did not take differences in exposure into account. Some bilingual groups (e.g., in heterogenous expat communities) may have more exposure to English than monolinguals because in transnational families English is often used as lingua franca (Pietikäinen, 2017; Soler and Zabrodskaja, 2017). In contrast, in larger and more homogenous bilingual communities, such as the Turkish community in the Netherlands, bilingual children may receive less exposure to English because the heritage language is used for communication with family and friends, and media in the heritage language are preferred to English-spoken media (Bezcioglu-Goktolga and Yagmur, 2017; Smith-Christmas et al., 2019). Hence, not controlling for differences in extramural exposure may mask bilingual advantages for bilinguals with less EFL exposure or reveal differences between monolingual and bilingual FL learners that are not due to bilingualism as such. Therefore, the present research will carefully control for individual differences in the amount of informal exposure to English outside of the classroom in comparing EFL performance of bilingual and monolingual pupils with DLD.

Developmental language disorder and foreign language learning

DLD is one of the most common learning disabilities, affecting 7–8% of children. It is thus as prevalent as dyslexia and more prevalent than autism (Bishop, 2017). Children with DLD have language deficits in the absence of hearing, intellectual and emotional impairments or frank neurological damage (Leonard, 2014). Grammar appears to be an area of core difficulty (Leonard, 2014), but problems in word-learning (Adlof et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2021) and deficits in discourse-pragmatic abilities (Norbury et al., 2014) have also been reported. There is also a growing body of evidence that DLD is associated with deficits in procedural learning ability (Ullman and Pierpont, 2005), working memory (Ellis Weismer et al., 1999; Jackson et al., 2020) and processing speed (Windsor, 2002; Ebert, 2021; Zapparrata et al., 2023), suggesting that the impairment is not specific to language.

The world-wide tendency towards inclusive education and early onset of FL instruction inevitably affects children with DLD (Pesco et al., 2016). For example, in the Netherlands, English lessons became mandatory at the primary level of special education in 2012. Special education schools, including the so-called cluster-2 schools for children with language disorders and hearing impairments, are now obliged to teach English from Grade 5 (age 10–11) onwards, but schools are free to introduce English lessons earlier. This being said, many children with DLD are enrolled in mainstream schools, where they can start EFL instruction as early as in kindergarten (age 4) (Thijs et al., 2011).

Research on bilingual and multilingual development of children with DLD has so far mainly focused on language acquisition in naturalistic settings, where an L2 is acquired with plenty of exposure (e.g., acquiring English in the United Kingdom). Research in these settings generally shows that even though bilingual children have reduced exposure to each of their languages, the negative effects of the disorder are rarely aggravated by bilingual exposure (Paradis et al., 2021). Surprisingly, very little is known about the mechanisms of (E)FL learning by children with DLD in instructed (classroom) settings. The distinction between naturalistic and instructed settings is particularly important in the context of DLD because the disorder is associated with language processing difficulties (Leonard, 2014) and procedural learning disadvantages (Ullman and Pierpont, 2005). Compared to typically-developing learners, children with DLD need at least twice as much input to learn patterns based on statistical information in the input (Tomblin et al., 2007; Evans et al., 2009). In school settings, language processing difficulties associated with the disorder are aggravated by the fact that exposure to the target language is limited, even in countries where children have relatively more frequent exposure to English through media.

In contrast to the rich literature on FL learning by typically-developing pupils, there are only a few studies focusing on pupils with DLD learning English as a school subject (Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood, 2019; Tribushinina et al., 2020, 2022, 2023a,b; Stolvoort et al., 2023). Their findings suggest that pupils with DLD learn English slower and attain lower scores than peers without DLD (Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood, 2019; Tribushinina et al., 2020), even though their EFL learning can be enhanced by using teaching methods tailored to the specific needs of this population (Tribushinina et al., 2022, 2023b; Stolvoort et al., 2023).

Thus far, Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood (2019) is the only study that compared foreign language (English) skills of monolingual and bilingual pupils with DLD. The study was conducted in the Netherlands. The participants were in the 6th grade of a special education school and had started learning English in the 5th grade (30–45 min a week). The participants spoke Dutch as the majority/school language, but a subset of the participants also spoke another language at home. The results revealed no significant differences between monolingual and bilingual pupils on any of the EFL measures, including listening, reading and vocabulary skills. However, the bilinguals were outperformed by monolinguals on receptive vocabulary and language comprehension in the majority language (Dutch), which is in line with the ample literature suggesting delays in bilingual learners associated with a later onset of and reduced exposure to the majority language (see review in Paradis, 2023).

Based on their results, Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood (2019) suggest that bilingual “advantages do not extend to children with DLD or children with learning disabilities” (p. 10). Notice, however, that this study, like other previous studies comparing bilingual and monolingual EFL learners, did not take into account that bilingual and monolingual children might have differed in the amount of exposure to English outside of school. As explained above, out-of-school exposure is one of the strongest predictors of EFL performance in typically-developing pupils (Lindgren and Muñoz, 2013; Leona et al., 2021). For children with DLD, there is recent evidence that the amount of extramural English is also a positive predictor of EFL vocabulary and grammar outcomes (Tribushinina et al., 2020; Stolvoort et al., 2023). Interestingly, Tribushinina et al. (2020) found that some of the differences between Russian-speaking EFL learners with and without DLD could be explained by differences in exposure. In their study, children with DLD scored worse than their typically-developing peers on English receptive grammar after 1 year of English lessons, but this difference proved non-significant once extramural exposure was controlled for.

The present study

As explained above, there is a growing body of evidence of bilingual advantages in FL learning, but the results are inconclusive. Furthermore, the literature on L3 advantages is largely limited to typically-developing populations. This study extends this line of research to pupils with learning disabilities by comparing EFL skills of monolingual and bilingual primary-school pupils with DLD attending a special education school in the Netherlands. One study thus far has explored differences between monolingual and bilingual EFL learners with DLD (Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood, 2019), but it did not take the amount of extramural English into account. The present study will address this methodological problem and pursue the following research question: Do bilingual pupils with DLD outperform their monolingual peers with DLD on EFL skills, if amount of out-of-school exposure to English is controlled for?

Previous studies conducted in the Netherlands revealed no L3 advantages in either children with DLD (Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood, 2019) or pupils with typical language development (Sanders and Meijers, 1995; Schoonen et al., 2002; Van Gelderen et al., 2003). In the Netherlands, the second language (Dutch) is usually acquired at the expense of the heritage/minority languages because minority languages are generally not supported in mainstream education (Extra and Yağmur, 2006; Wallace et al., 2021)1. Such subtractive contexts are less likely to lead to cognitive and linguistic advantages of multilingualism compared to more favorable additive contexts where (societal) bilingualism is cherished and supported in the school system, such as in Spain or Canada (Cummins, 2000). Furthermore, some of the potential sources of L3 advantages may be less accessible to pupils with DLD compared to typically-developing peers. More specifically, there is some evidence suggesting that DLD may impede positive cross-language transfer (Ebert et al., 2014), particularly in the domain of morphosyntax (Blom and Paradis, 2015; Tribushinina et al., 2020). Thus, bilingual children with DLD may have more difficulty using their previous language knowledge in learning new languages at school. Finally, children with DLD have more difficulty developing metalinguistic (particularly, morphosyntactic) awareness (Kamhi and Koenig, 1985), which again limits the possibilities to reap the benefits of bilingualism, since metalinguistic awareness is considered to be an important mechanism underlying positive effects of bilingualism on novel language learning. Therefore, our hypothesis is that no bilingual advantages will be found in EFL learners with DLD speaking Dutch (majority language) and a minority language.

Method

Participants

Seventy-two 9- to 12-year-old children with DLD were recruited from special education schools (cluster-2 schools for children with language disorders and hearing impairments) in the south-eastern part of the Netherlands. Data from one participant was not included in the analyses because English was one of the languages spoken in the home (and therefore, this child did not qualify as an EFL learner). The final dataset included 71 children (13 female), of whom 49 participants were raised monolingual, and 22 were raised bilingual. The monolingual participants spoke only Dutch at home, and the bilingual participants spoke Dutch and one of the following languages: Turkish (n = 6), Polish (n = 4), Arabic (n = 2), French (n = 2), Mandarin (n = 2), Armenian, Berber, Bosnian, German, Kurdish and Thai. The mean age of the monolinguals was 137.4 months (range: 111–161) and the mean age of the bilinguals was 131.6 months (range: 111–170). This difference was not significant (t(69) = 1.68, p = 0.098). The children had been independently diagnosed with DLD following a standardized protocol (Stichting Siméa, 2014), which requires an overall score of at least 2 SD below age-appropriate norms on a standardized Dutch language test (usually CELF-4-NL) or scores of at least 1.5 SD below the age-appropriate mean score on at least two of the four subscales of a standardized language test. A hearing impairment and intellectual disability (IQ scores <70) constitute exclusion criteria in the diagnostics of DLD. In line with recently adopted guidelines, the children are diagnosed with DLD if their non-verbal IQ is “neither impaired enough to justify a diagnosis of intellectual disability nor good enough to be discrepant with overall language level” (Bishop, 2017: 679). The non-verbal IQ scores of the participants (retrieved from the school records) ranged between 76 and 113.

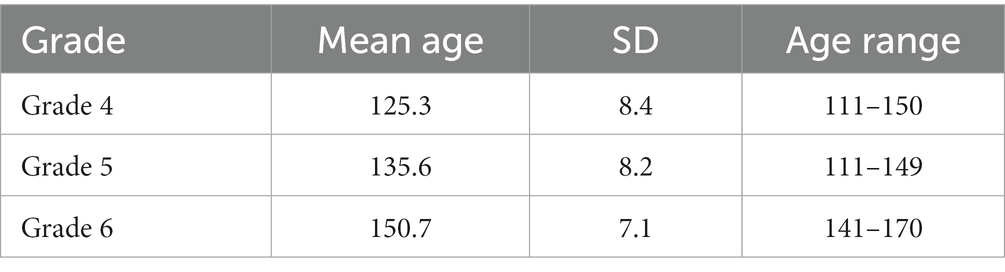

In the Netherlands, primary schools (including special education schools) are obliged to teach English starting in Grade 5, but they are also free to introduce English lessons earlier. The participants of the present study attended one of the three final grades of primary education (Grade 4–6), see Table 1. These grades were selected because the participating schools taught English from Grade 4 onwards. All participants received one 45-min English lesson a week. The children were tested halfway through the school year, which means that by that time the 4th graders had followed English lessons for half a year, and the 5th and the 6th graders, respectively, for one and a half and two and a half years.

Test instruments and scoring

Prior research comparing monolingual and bilingual FL learners with typical language development revealed bilingual advantages in vocabulary (e.g., Keshavarz and Astaneh, 2004; Hopp et al., 2019), grammar (e.g., Abu-Rabia and Sanitsky, 2010; Hopp et al., 2019), oral skills (e.g., Cenoz and Valencia, 1994; Brohy, 2001), writing proficiency (e.g., Sagasta Errasti, 2003; Abu-Rabia and Sanitsky, 2010) and reading comprehension (e.g., Rauch et al., 2011; Maluch and Kempert, 2017). For the purpose of comparability, the present study targeted the same subcomponents of EFL proficiency as much as possible. Language proficiency in Dutch and English was operationalized as performance on a receptive vocabulary test and several tests measuring grammatical ability. These skills are generally considered reliable indicators of overall proficiency (Hulstijn, 2010). In addition, oral proficiency in both languages was assessed using the so-called CAF measures (complexity-accuracy-fluency), which are well-established descriptors of L2 proficiency in instructed settings (see review in Housen and Kuiken, 2009), and are also used in research on bilingual FL learning advantages (Sagasta Errasti, 2003). Oral language samples in Dutch and English were elicited by means of picture narratives, which is a common method used in child L2 research and research on bilingual children with DLD in particular (Gagarina et al., 2015). Writing and reading skills were not assessed because Dutch primary schools mainly focus on oral EFL skills and because DLD has a high comorbidity with dyslexia.

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dutch)

A standardized Dutch version of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-III-NL) (Schlichting, 2005) was used as a measure of receptive vocabulary. In this test, children hear a word and see four pictures; their task is to match the word to one of the pictures. In this study, we used the test scores retrieved from the school database. The test was administered by the school-based speech and language therapists as part of the yearly progress monitoring, following a standardized procedure described in the test manual. The basal set was determined by the age of the participant. The test stopped after the ceiling set was reached, which was defined as a set containing 8 or more errors. Standardized quotient scores were calculated, which are scores corrected for age (Lam- De Waal et al., 2015).

Litmus Sentence Repetition Task (Dutch)

Sentence repetition tasks measure language proficiency at multiple levels, but they mainly tap grammatical ability (Klem et al., 2014). The rationale is that the test sentences are long enough to disallow passive parroting. To repeat a sentence, children need to process it through their grammatical systems and reconstruct using their active knowledge of the lexicon and grammar. The Dutch version of the LITMUS Sentence Repetition Task (SRT) developed within the COST Action IS0804 (Marinis and Armon-Lotem, 2015) for the purposes of diagnosing DLD in multilingual children was used to test the participants’ grammatical ability in the majority language. The Dutch SRT consists of 30 sentences of varying length and complexity. The structures included in the test are those that are known to be difficult both for Dutch children with typical language development and children with DLD (e.g., complements, modal verbs, short and long passives) (de Jong et al., 2021).

The task was designed as a “Treasure hunt” and administered by means of a PowerPoint presentation. The task started with two practice sentences. Next, the child was presented 30 slides, each playing one of the 30 pre-recorded sentences that they were asked to repeat. The child was allowed to hear each sentence only once. A repetition of the recorded sentence was allowed only if a loud sound interrupted the audio or when the child did not attempt to repeat the sentence after hearing it. Each child was tested individually in a quiet room in their school. The responses were recorded and later transcribed by trained research assistants. The task took approximately 8 min.

The Litmus SRT can be scored in several different ways (Marinis and Armon-Lotem, 2015). For this study, we implemented four different coding schemes: (i) 0–1 score, (ii) 0–3 score; (iii) grammaticality of the response; (iv) preservation of the target structure. Since the analyses based on these scoring methods provided the same results, for reasons of space, we only report the results of the first scoring procedure, where one point was assigned to each correct verbatim repetition of the stimulus sentences. By this scoring method, the maximum score was 30.

Vocabulary test (English)

In our prior work, we used the English versions of PPVT to trace EFL progress of pupils with DLD (Tribushinina et al., 2020). A disadvantage of such standardized tests is that they were designed for children acquiring English as their first language rather than for FL learners in classroom settings. For one, it is difficult to control for cognate effects as Dutch-English cognates are unevenly distributed across complexity sets, and children (with and without DLD) perform better on cognates than on noncognates (Tribushinina et al., 2023a,b). Therefore, we developed a word translation task that allowed us to control for cognate relationships and contained words that are included in EFL curricula at the primary-school level. The task consisted of 40 English words. These words included 20 Dutch-English cognates (above, climb, cost, deep, honey, jealous, light, loud, medal, rich, sand, shadow, sharp, sheep, sing, sneeze, swim, toe, tower, train) and 20 noncognates (after, angry, beach, belt, blanket, brush, button, clean, cloud, count, curtain, empty, healthy, meat, proud, ready, share, shout, taste, yawn). The cognates and the noncognates were matched on frequency and word length in both English and Dutch. The frequency of the words was derived from the CELEX lexical database2. Word frequency was determined by requesting the occurrence of the lemma in one million words in the COBUILD database for the English words and the Institute for Dutch Lexicology database for the Dutch words. There were no significant differences between cognates and noncognates on word length in English [t(38) = −1.58, p = 0.123] and Dutch (t(38) = 0.23, p = 0.817), and on frequencies in English [t(38) = −0.85, p = 0.401] and Dutch [t(38) = −0.66, p = 0.513].

The test was administered by means of a PowerPoint presentation and started with three practice items. The words were presented both auditorily and visually (in writing). The task of the child was to translate the English words into Dutch. It took the participants about 15 min to complete the test.

One point was awarded for each correct answer. Since we assessed the understanding of English vocabulary, a point was also awarded if a child gave a correct description/definition of the meaning of the word or if the meaning was acted out. For example, the following responses to the word sneeze were scored 1 point: niezen ‘sneeze’; dat doe je wanneer je aan peper of stof ruikt ‘this is what you do when you smell pepper or dust’; hatsjoe! (onomatopoeia). The results are presented as proportion of correct responses.

Grammar test (English)

Grammar knowledge in English was assessed with a written test based on the Pearson Longman English Language Placement Test. We included this test because it allowed us to assess the participants’ productive grammar knowledge using a test format that is commonly used in EFL classrooms. The test included 30 English sentences with a gap. Targeted structures included verb and noun morphology, prepositions, word order and negations. For each sentence, four options to fill the gap were provided, as shown in the examples below. The task of the participant was to circle the option that made a correct English sentence.

(1) We ______ English books.

(a) always reads (b) reads always (c) always read (d) read always.

The test was administered on paper during an English lesson. The participants were given 20 min to complete the test, but most of the pupils finished the task within 10–15 min. One point was allocated to each correct answer. The results are presented as proportion of correct responses.

Grammaticality judgement task (English)

To gain a deeper insight into the participants’ grammatical ability, we used a self-designed grammaticality judgment task. Grammaticality judgement tasks are often used to study language development of children with DLD. The performance on such tasks is known to be a strong predictor of language production: children are more likely to detect errors that they do not make and less likely to notice errors that they themselves make in their language production (Rice et al., 1999). Even more importantly, grammaticality judgments hinge on metalinguistic reasoning, which will give us an insight into the role of metalinguistic awareness as a potential source of bilingual FL learning advantages (cf. Abu-Rabia and Sanitsky, 2010).

The test included 54 sentences (half incorrect) and targeted subject-verb agreement, word order, determiners, and tense and aspect forms. The task was administered using PowerPoint and started by introducing a bear who was learning English and sometimes made mistakes. The child was asked to point out which of the sentences pronounced by the bear were correct and which were incorrect. For the sentences judged incorrect, the child was asked to explain what was wrong and/or correct the error. Each slide contained an image of the bear as well as the written version of the target sentence accompanied by a pre-recorded sentence. We chose to present sentences both visually and orally because children with DLD have deficits in verbal working memory.

The test started with three practice trials. The children were allowed to take four short breaks during the experiment. The responses were audio-recorded and later transcribed for further coding. The test took, on average, 20 min. Each grammatical sentence judged correct was awarded 1 point. In case the child correctly indicated the sentence was ungrammatical, a point was only awarded if the correction or the explanation of the mistake was appropriate. The results are presented as proportion of correct responses.

Narrative task (Dutch and English)

Narratives were elicited using the Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives (MAIN) (Gagarina et al., 2012). This instrument contains parallel sets of four picture stories (comprising 6 pictures each), which makes it possible to assess the multiple languages a child speaks. In this study, the instrument was used to elicit a narrative in both the majority language (Dutch) and the foreign language (English). Two different MAIN stories were used, the Cat Story and the Dog Story. If the child told the Cat Story in Dutch, they produced the Dog Story in English, and vice versa.

The narratives were elicited following the procedure as outlined in the guidelines provided by Gagarina et al. (2012) for the English narratives and the translated guidelines by Blom et al. (2020) for Dutch. The child was allowed to scrutinize all six pictures before telling the story and was asked not to show the pictures to the experimenter. Most of the Dutch stories were told without many questions or concerns. The English stories were more challenging for the children. Most comments concerned not knowing words in English. In these cases, the children were instructed that they could use a word they thought was the right one, make one up or use the Dutch counterpart.

The narratives were recorded and transcribed by trained research assistants using the CHAT (Codes for the Human Analysis of Transcripts) transcription system in CLAN (Computerized Language Analysis) (MacWhinney, 2000). The transcribed utterances were then transformed to C-units taking the guidelines described in Curenton (2004) as a starting point. The first step in this process was to remove all the material that was not relevant to the narrative. This meant that only narrative-related comments by the child were retained, either spontaneous or responses to the standard probes. Furthermore, retraces and false starts were deleted from the transcripts, as well as untranscribable utterances that were not part of a bigger utterance. According to Curenton (2004), the C-units had to contain a subject-verb proposition, though it was not clear whether the subject was also allowed to be a null-subject. In this study, we decided to treat utterances containing a null subject as a C-unit, as long as a predicate was present. This approach was taken because variability in the production of grammatical subjects is common in children with DLD (Grela, 2003). In cases where an utterance started with a coordinating conjunction but did not contain a predicate, if appropriate in the context, the utterance was annexed to the previous utterance and regarded as one C-unit. An example of this is given in (2), the underlined section indicating the annexed utterance.

(2) en de ballon glijdt van zijn hand en die in boom.

‘and the balloon slips off his hand and that one in tree’.

Similarly, an utterance that started with a subordinating conjunction was added to the previous utterance and regarded as one C-unit in cases where the content of the subordinate clause clearly modified the content of the main clause. Separate utterances were also added to previous C-units in the case that the child interrupted their utterance (i.e., because they were thinking out loud about the correct word) and then only produced the one word they were thinking of and did not repeat the entire sentence. An additional guideline that was adhered to specifically for the English narratives concerned C-units containing code-switches. If a C-unit contained only code-switches, then this C-unit was removed from the transcript. In all other cases, even if the C-unit contained only one word in English, the C-unit was kept as part of the transcript to give credit to all the English produced by the children. A narrative was used for further analyses when a combination of Dutch and English together formed at least one C-unit.

The narratives were analyzed for fluency, lexical diversity, grammatical accuracy and syntactic complexity (Housen and Kuiken, 2009). Fluency was operationalized as the total number of word tokens and lexical diversity as the total number of word types (lemmas) in the target language per narrative. Analyses of grammatical accuracy involved counting the number of grammatical errors per transcription and dividing them by the number of word tokens, producing error rates per narrative.

Finally, syntactic complexity was operationalized in two different ways: as a mean length of C-unit (MLCU) and a ratio of elaborate noun phrases (ENPs). MLCU was established by dividing the number of target language tokens by the number of C-units in the narrative. ENPs are groups of words with a noun as its head, and with additional words modifying the noun. The number of ENPs children use gives an indication of the extent to which they are able to be explicit about characters, objects and events (Curenton and Justice, 2004). A simple ENP is an ENP modified by a single modifier as in (3), whilst a complex ENP is modified by two or more modifiers as in (4). Several word classes were considered modifiers: articles, possessives, quantifiers, demonstratives, wh-words and adjectives.

(3) the boy, the balloon, yellow balloon, his bag, the ground.

(4) the yellow balloon, his first fish, the little kid, a beautiful day.

Each simple ENP was allocated one point, each complex ENP was allocated two points. Noun phrases with post modification, as in (5), were allocated an additional point, regardless of the length of the post modification. Noun phrases which were postmodified by a relative clause, as in (6), were allocated additional two points, as the production of such clauses is more challenging than regular post-modification of noun phrases.

(5) the boy with the fishing rod.

(6) een jongetje die van boodschappen klaar was met een ballon.

‘a boy who was done doing groceries with a balloon’.

The following guidelines regarding the scoring of ENPs were adhered to: (a) direct repetitions of ENPs were not allocated points twice, (b) for phrases similar to a mouse and dog only a mouse was considered an ENP, (c) instances where the meaning was unclear no points were allocated (e.g., the dog’s happen), (d) English relative clauses were given two points only if at least 50% of the C-unit was in English, (e) English simple and complex ENPs were only given points when they were completely in English. In the case of postmodified ENPs containing Dutch, English simple and complex ENPs within the ENP or post-modification were allocated points. For example, in (7) one point is given for the simple ENP the fish as well as one point for the post-modification, but no point is given for the second ENP the emmer@s:nld.

(7) the fish in the emmer@s:nld.

‘the fish in the bucket’.

The total number of points per narrative was divided by the number of C-units in the narrative, thus adjusting the total score to the length of the narrative.

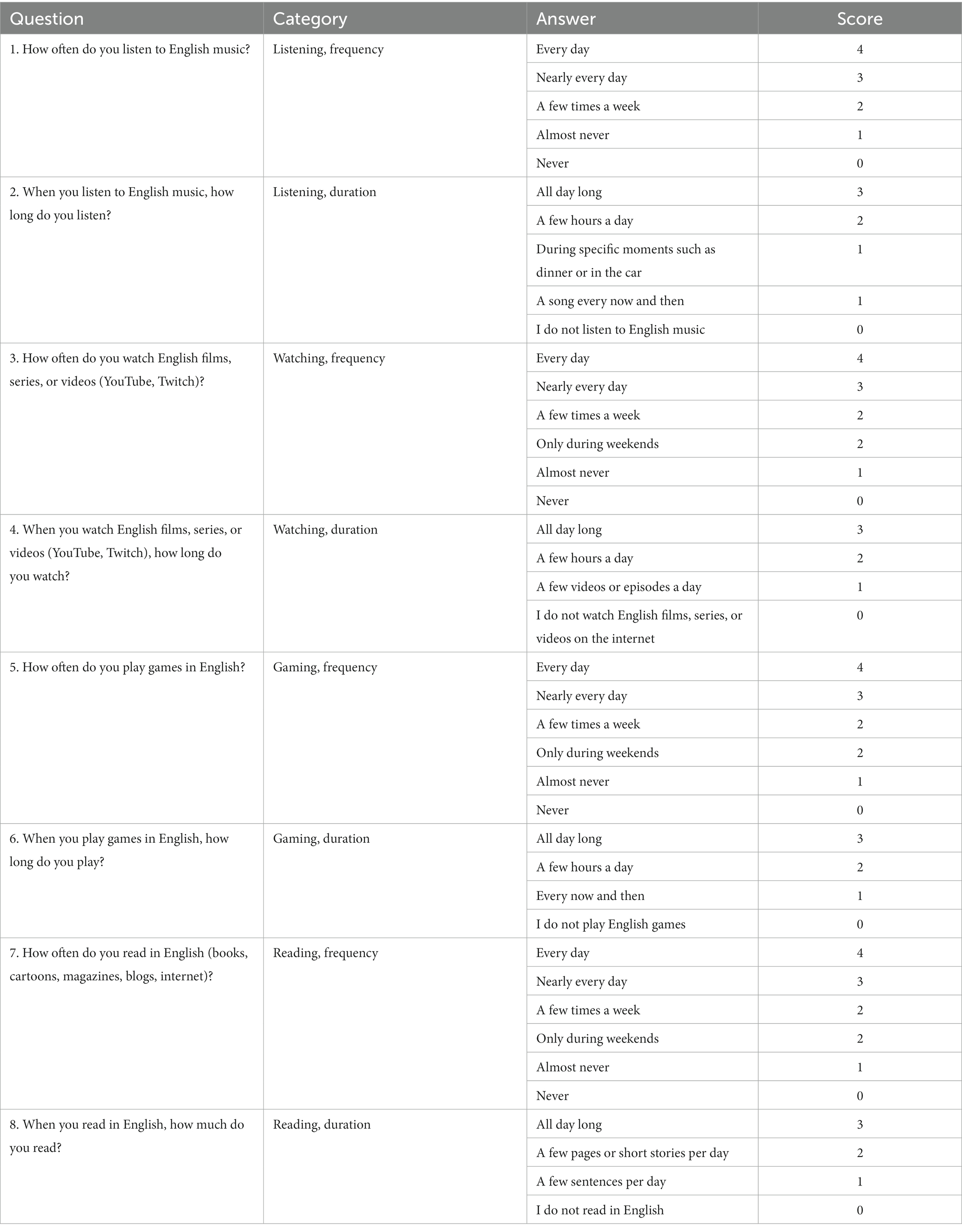

Exposure questionnaire (English)

To measure out-of-school exposure to English, we used a questionnaire that gauged exposure to English in four different categories: listening (to music), watching (series, television and films), gaming and reading (books, cartoons, magazines, blogs and Internet). These categories cover seven of the eight types of extramural English as proposed by Sundqvist (2009). Prior research revealed these are the most frequent types of out-of-school exposure to English outside of the classroom (Sundqvist, 2009; Lindgren and Muñoz, 2013; Peters, 2018; Muñoz, 2020; Leona et al., 2021). Notice that these exposure categories mainly pertain to receptive exposure even though playing computer games may involve some productive use of English with co-players. Previous studies that focussed specifically on the role of exposure and administered more elaborate questionnaires (particularly to older children and adults), also included productive use of English with foreigners or friends (Muñoz, 2020; Leona et al., 2021) and writing through Internet (email, Whatsapp, blogging) (e.g., Muñoz, 2020; Rød and Calafato, 2023). Since such types of extramural EFL exposure are fairly infrequent even in typically-developing pupils under age 12 and particularly in FL learners with DLD (Tribushinina et al., 2020), we did not include questions about productive use of English in our questionnaire not to overburden and/or demotivate our vulnerable participants. For brevity, we use the terms ‘extramural’ and ‘extracurricular’ exposure throughout the paper, even though our operationalization does not include productive forms of extramural English.

The questionnaire was designed in a way that would allow primary-school children with language learning difficulties to understand the questions and to give accurate estimates. This questionnaire has been shown to be suitable for guided administration to primary-school children with DLD and to be a good predictor of vocabulary and grammar outcomes in English as a FL (Stolvoort et al., 2023).

The score for each exposure category consisted of one score for frequency and one for duration. The answer options for the questions regarding frequency were translated to a Likert-scale from 0 points (never) to 4 points (every day). For the questions on duration, the answer options were customized depending on the activity, but these too were translated to fixed Likert-scale scores ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (all day long). By adding up the Likert-scale score for frequency (max. 4) and duration (max. 3) per exposure category, the score for the total amount of exposure per activity (max. 7) was calculated. The total exposure score (max. 28) was determined by adding up the amount-of-exposure scores from each category. The questions in the questionnaire (translated to English for convenience) as well as the Likert-scale scores per answer option can be found in the Table A1.

Procedure

All tests, except the multiple-choice grammar test and the exposure questionnaire, were administered individually, in a quiet room in the child’s school. The grammar test was a paper-and-pencil test administered during an English lesson. The exposure questionnaire was read out aloud by the teacher (in Dutch) and the pupils filled in the paper-and-pencil questionnaire individually. The order of the tasks was counterbalanced across participants. Dutch and English were tested on separate days. The English tasks were conducted in two separate sessions. The experimenters were all Dutch native speakers with a university degree in English linguistics.

Statistical analyses

The data of the English tests were analysed by means of generalised mixed-effects logistic regression analyses using the glmer function in R (Bates et al., 2015; R Development Core Team, 2022). In all analyses, we started off with a base model including only Group (monolingual; bilingual) as a predictor. Subsequently, we added Grade (4;5;6) and after that Exposure to the model to control for differences in, respectively, the amount of prior EFL instruction and amount of out-of-school exposure to English. For the vocabulary test, we also added Word Category (cognate; noncognate) and the interaction between Group and Word Category in the last steps. The predictors were retained in the model if they significantly improved the model fit. Participant nested in Class (Class:Participant) and Item were included in the random part of all the models. The bilingual group was used as the baseline.

Narrative data and the scores on the Dutch tests were analyzed by means of multilevel linear regression analyses performed using the lmerTest package in R (Kuznetsova et al., 2017). Participant nested in Class (Class:Participant) and (for the narrative task) Story (Cat; Dog) were included in the random part of the model. We started off with a base model in which only Group (monolingual; bilingual) was included in the fixed part. Subsequently, we controlled for age (on the Dutch SRT and narrative measures) and Grade and Exposure (for the English narrative measures). These predictors were only retained in the final model if they significantly improved the model fit. For the Dutch PPVT, the base model was the final model because we used the quotient scores corrected for age. The bilingual group was used as the baseline.

Results

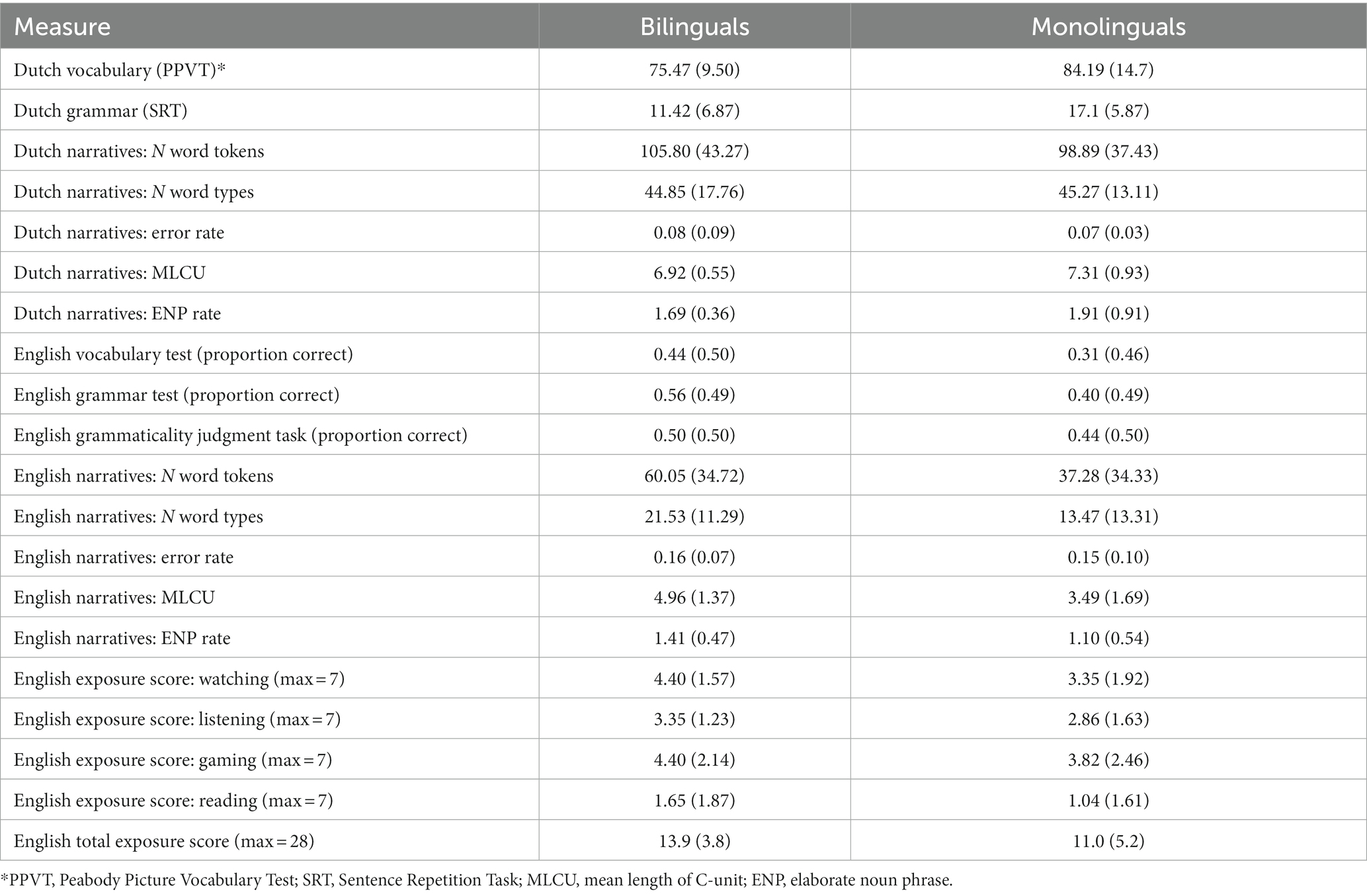

The descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for the monolingual and bilingual group are presented in Table 2.

The figures in the table show that bilinguals tend to have lower scores in Dutch and higher scores in English. The types of out-of-school exposure to English were similar for bilinguals and monolinguals, with watching (films, series, videos) being the most prominent category followed by gaming and listening to music. Amount of exposure was not significantly related to participants’ age in any of the categories. Monolinguals had significantly less out-of-school exposure to English compared to bilinguals (B = −2.67, SE = 0.14, t = −20.80, p < 0.001), which underlines the need to control for differences in exposure when comparing monolinguals and bilinguals on EFL measures.

Dutch measures

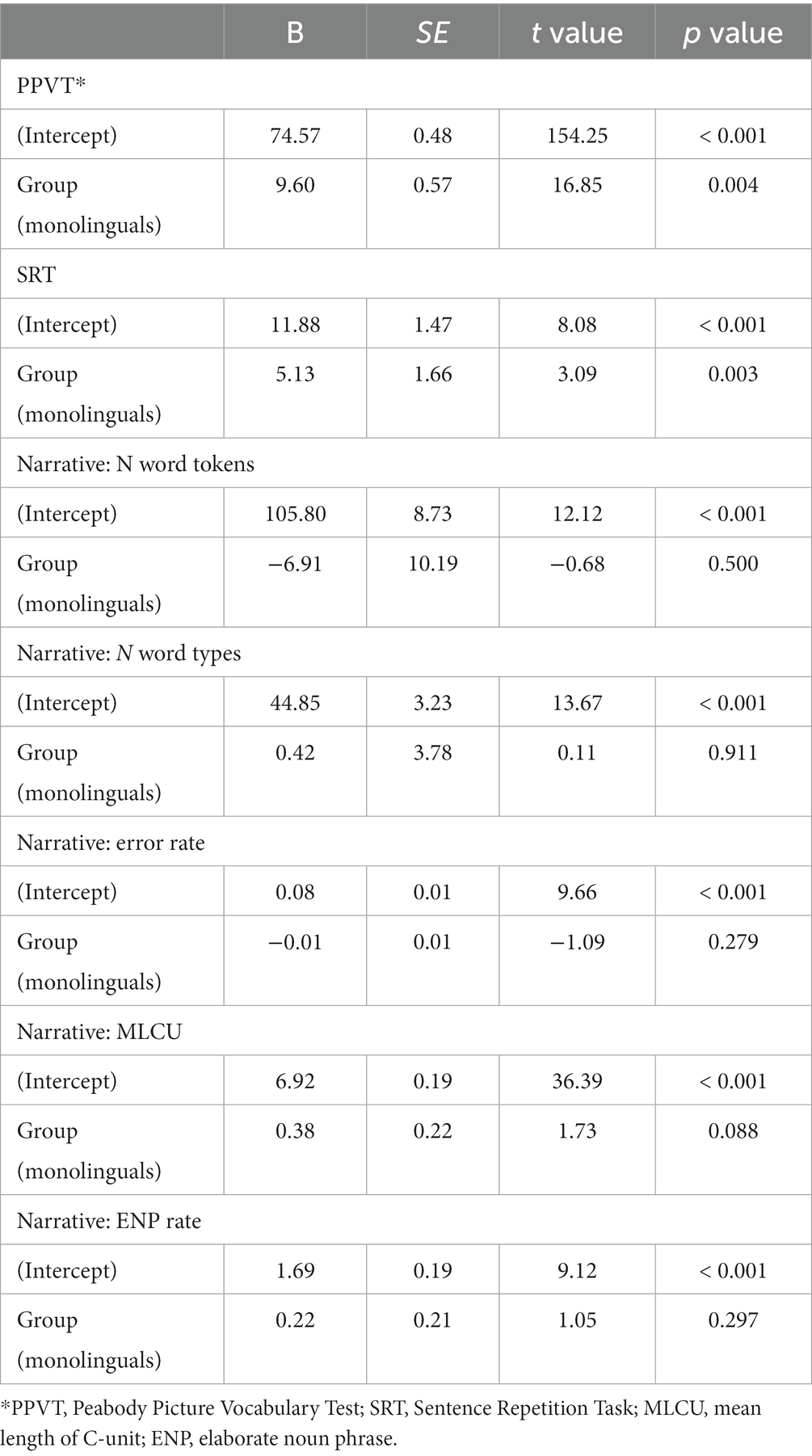

Table 3 reports coefficients of the optimal models. Age did not improve the model fit in any of the models. Therefore, the final models only included Group (monolingual; bilingual) as a main effect.

As is evidenced from Table 3, there were no differences between bilinguals and monolinguals on the narrative measures, but monolinguals scored significantly higher on both vocabulary (PPVT) and grammar (SRT).

English measures

Vocabulary test

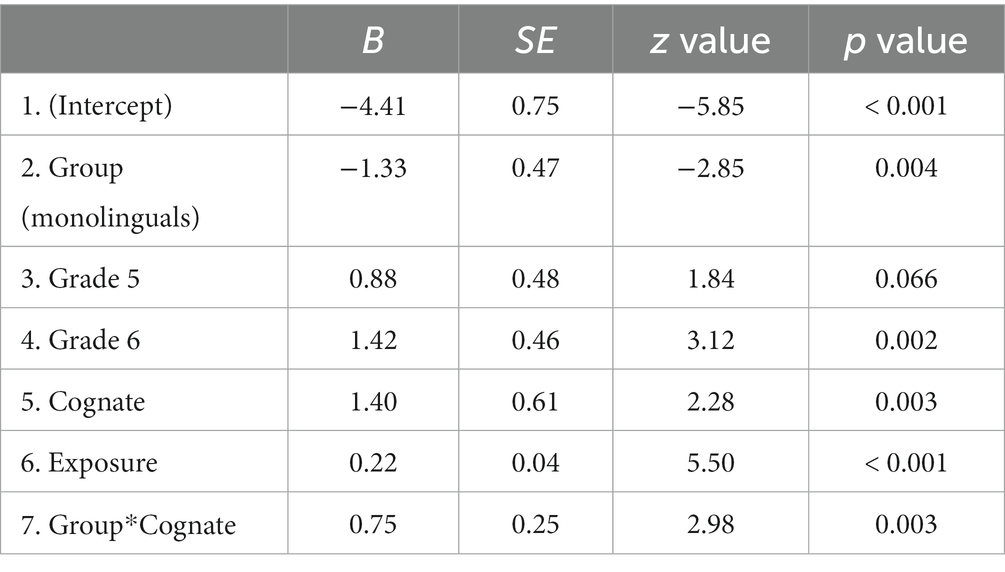

The base model (model 1) with Group (monolingual; bilingual) as a fixed effect revealed that bilinguals performed significantly better than monolinguals (B = −1.06, SE = 0.50, z = −2.12, p = 0.034). Adding Grade to the model (model 2) significantly improved the model fit [x2 (1) = 10.20, p = 0.001]. In model 3, Exposure was also added to the model, which again increased the fit to the data [x2 (1) = 25.66, p < 0.001]. Adding Word Category (cognate; noncognate) to the model (model 4) again significantly increased the fit [x2 (1) = 8.20, p = 0.003]. Finally, in model 5, we added an interaction between Word Category and Group, which significantly improved the model fit [x2 (1) = 8.54, p = 0.003]. Hence, model 5 is our final model (see Table 4).

Table 4. Coefficients of the optimal model for the English vocabulary test (treatment coding was used for the categorical variables).

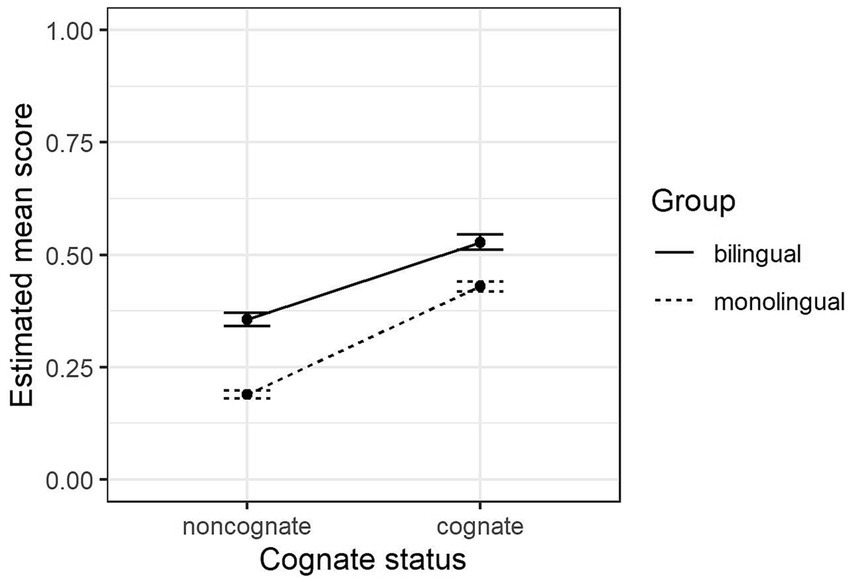

The model coefficients in Table 4 reveal that 6th graders performed better than 4th graders (predictor 4), but no difference between 4th and 5th graders was found (predictor 3). Amount of out-of-school exposure to English positively predicted performance (predictor 6). Monolinguals performed worse than bilinguals (predictor 2). Bilinguals performed better on cognates than non-cognates (predictor 5), but the cognate advantage was stronger in the monolingual group (predictor 7). This interaction is visualized in Figure 1, which suggests that monolinguals benefit from Dutch-English cognates more than bilinguals.

Grammar test

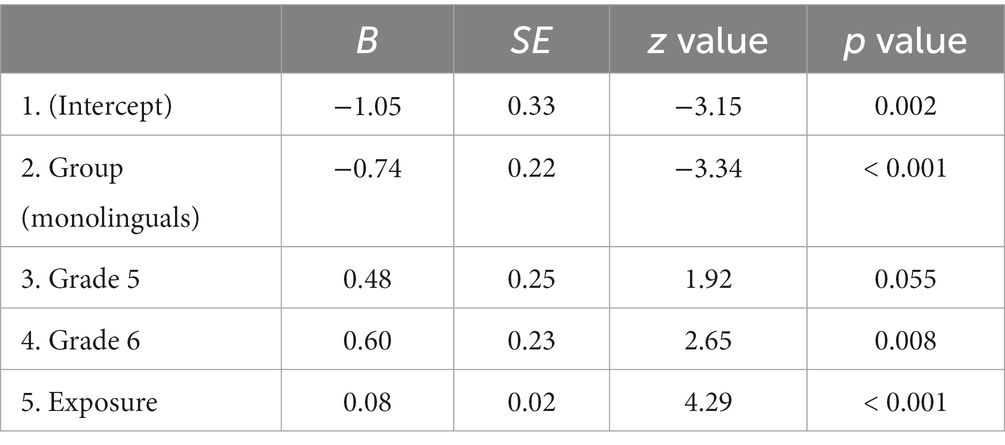

Again, we started with a base model including only Group (bilingual; monolingual) as a fixed effect. In this model, bilinguals performed significantly better than monolinguals (B = −0.76, SE = 0.24, z = −3.19, p = 0.001). In model 2, we added Grade, which significantly improved the model fit [x2 (1) = 9.87, p = 0.007]. Finally, Exposure was also added to the fixed part as a control variable in model 3, which again significantly increased the fit [x2 (1) = 16.60, p < 0.001]. The coefficients of model 3 are presented in Table 5. The bilingual advantage observed in the base model is retained after controlling for Grade and Exposure. Exposure positively predicted performance, and 6th graders (but not 5th graders) outperformed 4th graders.

English grammaticality judgment task

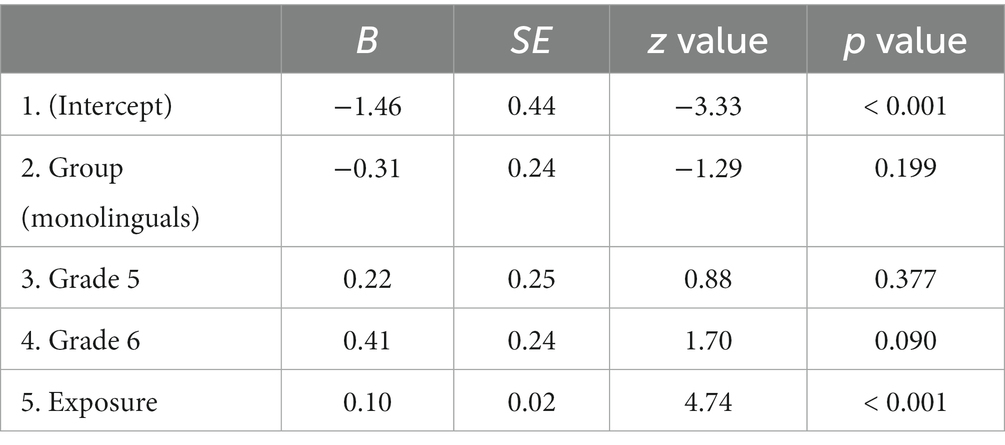

The base model with only Group (bilingual; monolingual) showed no significant group differences (B = −0.36, SE = 0.24, z = −1.49, p = 0.138). However, when controlling for Grade in model 2, the effect of group became significant (B = −0.70, SE = 0.25, z = −2.75, p = 0.006). Model 2 had a better fit to the data than model 1 [x2 (1) = 7.37, p = 0.025]. Finally, in model 3, Exposure was added as a control variable, which again significantly increased the model fit [x2 (1) = 19.74, p < 0.001]. In this final model, the effect of Group became non-significant (see Table 6). The only significant predictor of performance on the grammaticality judgment task was exposure to English outside of the classroom.

Narrative measures

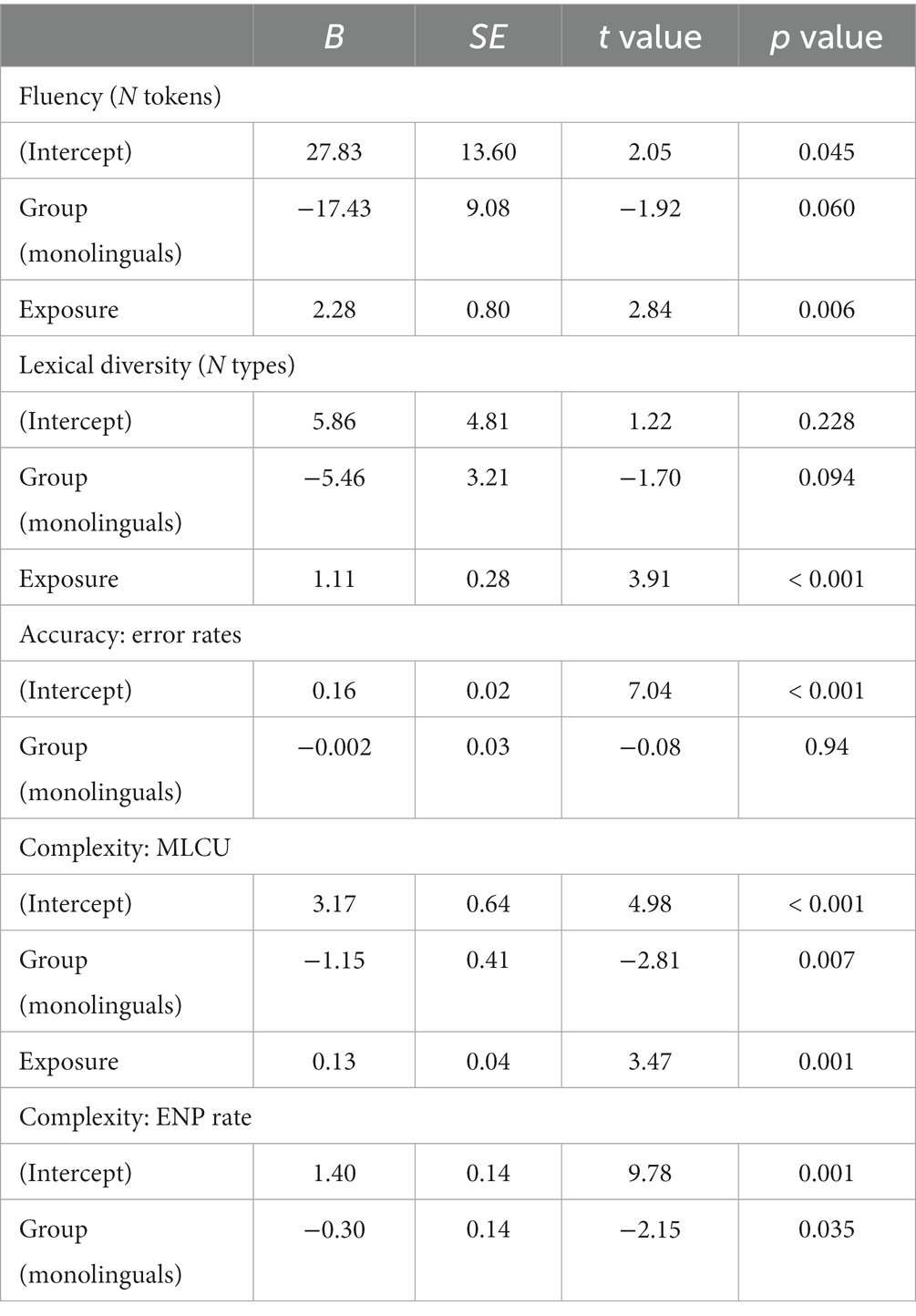

We conducted separate multilevel linear regression analyses for each narrative measure. In all of the analyses, we started with a base model comparing bilinguals and monolinguals. After that we added Grade and Exposure as control variables. Adding Grade did not significantly improve the fit of any of the models. Adding Exposure did not result in an increased fit for the models targeting accuracy [x2 (1) = 0.13, p = 0.715] and ENP rates [x2 (1) = 0.72, p = 0.395], but Exposure did improve the fit for the models targeting fluency (x2(1) = 7.95, p = 0.005), lexical diversity [x2 (1) = 14.33, p < 0.001] and MLCU [x2 (1) = 11.25, p < 0.001].

As evidenced by the model coefficients in Table 7, bilinguals outperformed monolinguals on both measures of syntactic complexity (MLCU and ENP rate). There were no differences between bilinguals and monolinguals on accuracy (error rates), lexical diversity (N word types) and fluency (N word tokens). Notice, however, that in the base models not controlling for differences in exposure, the effect of bilingualism was significant for both lexical diversity (B = −8.05, SE = 3.47, z = −2.32, p = 0.024) and fluency (B = −22.78, SE = 9.36, z = −2.43, p = 0.018). This stresses the importance of controlling for extramural exposure to English when comparing bilinguals and monolinguals.

Discussion

Bilingual advantages in FL learning, albeit not uncontroversial, have been repeatedly reported in the literature on typically-developing pupils. This paper has extended this line to research to primary-school pupils with learning disabilities by pursuing the question whether similar advantages hold for primary-school children with DLD in special education. Our main findings are: (i) bilingual pupils with DLD perform worse than their monolingual Dutch-speaking peers with DLD in the majority/school language; (ii) bilinguals with DLD outperform their monolingual peers with DLD on (some of the) foreign language measures; (iii) bilingual advantages can be overestimated if differences in out-of-school exposure to English are not taken into account.

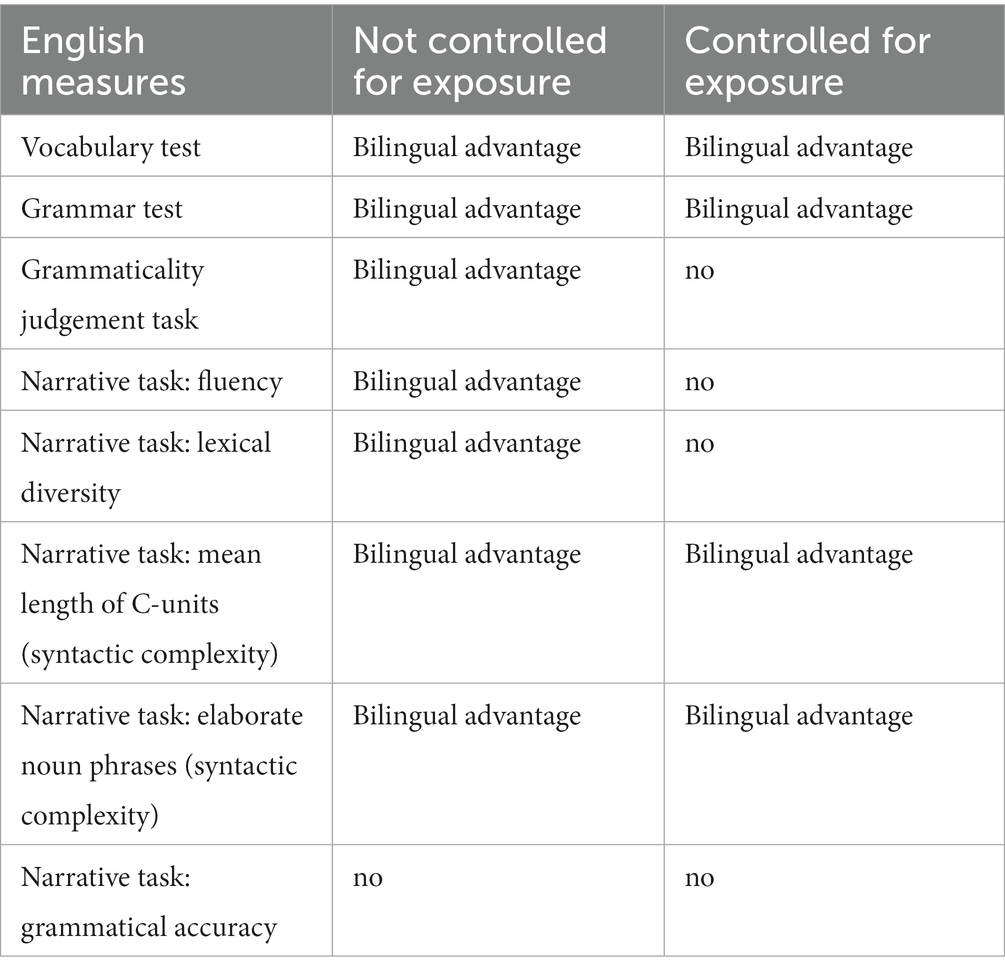

Differences in extramural exposure to English

Although amount of out-of-school exposure to English is known to be one of the strongest predictors of EFL performance, previous studies comparing bilingual and monolingual EFL learners have not controlled for possible differences in exposure. To the best of our knowledge, Sanz (2000) is the only published study that has taken both formal and informal EFL exposure into account in comparing EFL skills of Spanish monolinguals and Spanish-Catalan bilinguals. However, their measure of informal exposure only included the number of activities pursued in English (e.g., reading and watching providing a score of 2) and was not sensitive enough to predict performance in English. The results of the present study demonstrate that not taking differences in exposure into account may skew the results. Without controlling for differences in extracurricular exposure, we found bilingual advantages on all EFL measures except grammatical accuracy of narratives (see Table 8). However, three of the attested differences disappeared when amount of extramural exposure was included in the analyses. These results demonstrate that the extent of bilingual advantages can be overestimated if extramural English is not taken into account, which underlines the need to control for differences in exposure in future work on this topic. Based on the current results, we suggest that future studies should pursue a more rigorous recruitment procedure by matching bilinguals and monolinguals on out-of-school exposure to English at the outset of research.

Interestingly, the bilingual advantage observed in the receptive vocabulary test did not translate into greater lexical diversity of the narratives, i.e., productive vocabulary in use. Similarly, bilinguals’ enhanced performance on the multiple-choice grammar test was not reflected in greater accuracy rates in the narratives. This pattern is in line with earlier findings on children with DLD revealing greater problems in expressive language skills than in receptive skills (e.g., Bruinsma et al., 2023). Furthermore, narrative tasks are known to be conceptually and linguistically demanding because they require parallel organization of the narrative at the macrolevel (e.g., episode structure, referential coherence) and at the microlevel (word choice, sentence structures). Based on teacher reports, we know that the participants in the present study never practiced story-telling tasks in their English lessons even though they did so in their Dutch lessons and in language therapy. This might suggest that bilingual learners need to have sufficient practice in a particular skill before they can reap the benefits of bilingualism. At the same time, the bilingual advantages were found in the syntactic complexity of the English narratives: Bilinguals produced longer sentences and more elaborate noun phrases. This disparity seems to reflect the well-known trade-off between accuracy and complexity: learners producing longer and more complex utterances are more likely to make errors (Housen and Kuiken, 2009; Piggott, 2019). Finally, bilingual advantages were not observed in the grammaticality judgment task, which might be due to the fact that the ability to detect ungrammaticality is particularly vulnerable in learners with DLD (Kamhi and Koenig, 1985) and even multilingual experience does not help children with DLD to develop more advanced morphosyntactic awareness.

The bilingual paradox

A robust finding in the literature is that pupils’ skills in the school language positively predict their FL outcomes (Sparks and Ganschow, 1993; Sparks et al., 2009; Siu and Ho, 2015; Sparks, 2016; Tribushinina et al., 2020), particularly when the school language and the FL are typologically similar (e.g., Dutch-English, German-English) (Edele et al., 2018; Van de Ven et al., 2018; Lorenz et al., 2020; Tribushinina et al., 2021). School language proficiency has been shown to predict FL skills in both monolingual (e.g., Siu and Ho, 2015; Van de Ven et al., 2018; Tribushinina et al., 2020) and bilingual (Edele et al., 2018; Lorenz et al., 2020; Tribushinina et al., 2021) pupils. Such cross-language relationships have been attributed to positive cross-linguistic transfer of language knowledge and skills (Cummins, 2000; Sparks, 2016), as well as to the fact that the majority language is used as a medium of instruction in the English lessons (Edele et al., 2018; Lorenz et al., 2020).

Our bilingual participants scored worse than monolinguals on Dutch vocabulary and grammar, which confirms previous findings that bilinguals may have smaller vocabularies and lag behind their monolingual peers in the acquisition of grammar (e.g., Nicoladis and Marchak, 2011; Unsworth, 2013; Unsworth et al., 2014). We would then expect them to also score worse on EFL vocabulary and grammar because, following the general trend emerging from the literature, children with lower skills in Dutch are expected to obtain lower scores in English. However, the situation in English is reversed, with bilinguals outperforming monolinguals on four of the eight measures (see Table 8). This finding not only shows that bilingual FL learning advantages extend to pupils with learning disabilities (contra Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood, 2019), but also leaves us with an intriguing paradox. As pointed out by a reviewer, it might be the case that proficiency in the school language predicts FL outcomes within but not across groups: Bilinguals with stronger skills in the school language may have stronger English skills (compared to other bilinguals) and monolinguals with higher proficiency in the school language may have higher FL proficiency (relative to other monolinguals). And yet it is remarkable that our bilingual participants performed worse than monolinguals in Dutch, but the same children outperformed the monolinguals in English. A similar asymmetry was reported by Hopp et al. (2019). In their study, typically-developing bilinguals attending primary education in Germany were outperformed by monolingual German-speaking children on German vocabulary and grammar, but performed better than monolinguals in English, even though L3 advantages abated with age. Likewise, Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood (2019) demonstrate that bilingual primary-school children with DLD have lower vocabulary and comprehension skills in Dutch, even though no differences between monolinguals and bilinguals were found in English (but recall that differences in exposure were not controlled for).

Given the typological similarity between Dutch and English, knowledge of Dutch vocabulary and grammar should be a catalyst in the development of the corresponding skills in English. Indeed, the results of our vocabulary test showed that both monolinguals and bilinguals benefitted from the knowledge of Dutch-English cognates, but the cognate advantage was larger in the monolingual group. A plausible explanation of this differential relationship is that bilinguals have smaller vocabularies in Dutch (as evidenced by the PPVT scores) and, therefore, recognize fewer cognates in English. In this respect, monolinguals might be said to have an advantage in learning EFL. However, given the overall pattern of results, this bilingual disadvantage is presumably counteracted by several benefits of bilingualism that render bilingual pupils better FL learners.

Possible underlying sources of L3 advantages

As explained in the Introduction, L3 advantages attested in typically-developing learners have been attributed to enhanced cognitive skills, better developed metalinguistic awareness and positive transfer of language knowledge and skills (Hirosh and Degani, 2018). Given the typological properties of the home languages included in our sample and language-learning mechanisms in DLD, positive transfer of vocabulary and grammar knowledge from the home language does not seem to be a likely source of bilingual EFL advantages. Firstly, compared to Dutch, the number of, for example, Turkish-English cognates is very limited due to a larger typological distance (Blom, 2019). In the domain of grammar, the home languages in our sample could potentially lead to accelerated acquisition of some aspects of the English grammar. For example, Dutch is a non-aspectual language (Boogaart, 1999), whereas all the home languages (except German) have the category of grammatical aspect, which could potentially facilitate the acquisition of the progressive-simple distinction in English (The children swim in the river vs. The children are swimming in the river). Similarly, both Turkish and Polish, like English, make a distinction between adjectives (e.g., beautiful) and adverbs (e.g., beautifully), whereas Dutch does not mark adverbs explicitly. This being said, there is evidence that children with DLD cannot make efficient use of cross-linguistic similarities in the acquisition of L2 grammar (Blom and Paradis, 2015; Tribushinina et al., 2020), which makes it less likely that the EFL advantages observed in the present study are due to positive transfer of L1 grammar knowledge to L3. However, based on our data, we cannot resolve this issue because we only focused on the pupils’ outcomes in the majority language (Dutch) and in the FL (English) (cf. Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood, 2019) and did not study their exposure to and proficiency in the heritage languages. It is plausible that bilingual advantages are particularly strong in bilinguals with sufficient exposure to the heritage language (cf. Maluch et al., 2016) and/or relatively strong heritage language skills (cf. Keshavarz and Astaneh, 2004; Rauch et al., 2011). Future research should test this possibility by sampling more homogenous bilingual groups of children with DLD and relating their proficiency in the heritage language to FL outcomes.

Bilingual advantages in English vocabulary and grammar are also not likely to stem from enhanced metalinguistic awareness because metalinguistic awareness (more specifically, morphosyntactic awareness) has been shown to be problematic in children with DLD (Kamhi and Koenig, 1985). Even though our study did not include an independent measure of metalinguistic awareness, the performance on the grammaticality judgment task is quite informative in this respect because such tasks are commonly used to measure metalinguistic awareness and to compare metalinguistic skills of bilinguals and monolinguals (e.g., Bialystok, 2001; Foursha-Stevenson and Nicoladis, 2011; Bialystok and Barac, 2012). Although bilingual children outperformed their monolingual counterparts on the grammar test and on syntactic complexity of narratives, there were no significant differences on the grammaticality judgment task once controlled for differences in exposure. This might suggest that bilingual children have better grammatical skills in English in the absence of enhanced metalinguistic skills.

This leaves us with transfer of language skills (as opposed to language knowledge) and cognitive benefits associated with bilingualism as potential sources of L3 advantages of children with DLD. There is evidence that bilingual children with DLD may have advantages over their monolingual peers with DLD in allocation of attention (Park et al., 2020) and in verbal working memory (Blom and Boerma, 2017). These skills are important in the language learning process and may be used as a compensatory mechanism in DLD. It has also been suggested that bilingualism plays a protective role when it comes to deficits in lexical retrieval associated with DLD. Degani et al. (2019) found that both bilingualism and DLD negatively affected lexical retrieval. However, the performance of bilingual children with DLD was better than would be expected based on the cumulative effects of bilingualism and DLD. The authors hypothesize that bilingual children may be equipped with more scaffolding mechanisms that facilitate word retrieval, such as supporting cues from the corresponding lexical entry in the other language. Such advantages are seen as consequences of dual language experience and may play a role in enhanced L3 learning skills of children with and without DLD (Hirosh and Degani, 2018).

Limitations and future directions

This study has revealed that bilingual pupils with DLD outperform their monolingual peers with DLD in special education on (some of the) EFL outcomes. This is an important finding demonstrating that L3 advantages are not limited to pupils with typical language development; even children with severe language disorders may reap the benefits of bilingualism in learning new languages. However, the design of our study did not allow us to unravel the underlying sources of such advantages since this study did not include cognitive or affective measures. An important avenue for future research in this field would be to test whether differences between monolingual and bilingual (E)FL learners are mediated by language learning skills (e.g., lexical retrieval, fast mapping) and cognitive skills (e.g., general intelligence, interference suppression, cognitive flexibility, working memory). Another potentially relevant factor that was not considered in the present study is language learning motivation since bilinguals may experience more positive attitudes towards novel language learning (Merisuo-Storm, 2007; Mady, 2017).

We compared bilinguals with monolinguals sharing the same school and the same classroom. This approach has a number of advantages because pupils sharing the same environment are likely to have more in common than students enrolled in different classes and schools (Hox et al., 2017). This pertains to similarities in teaching approaches, teacher quality and group dynamics. In the Dutch context, pupils attending the same school are also similar in terms of socio-economic status (Sykes and Musterd, 2011). This being said, a significant disadvantage of our approach is that we could not recruit sufficient numbers of pupils sharing a specific home language (e.g., Turkish or Polish), which did not allow us to investigate the role of positive L1 transfer. Given the prevalence of DLD (7–8%), it is difficult to sample sufficient numbers of relatively homogenous bilingual groups. This notwithstanding, future research will benefit from studies that could give more nuanced insights into the relationships between specific L1 knowledge and skills, and the ease with which bilinguals acquire similar phenomena in a novel language. It is also crucial to study the extent of bilingual advantages in relation to heritage language exposure and proficiency (cf. Sagasta Errasti, 2003; Maluch et al., 2016; Lorenz et al., 2020).

Our exposure questionnaire involved all frequent types of extramural English that have been reported in the studies conducted in similar contexts and that have been shown to predict FL outcomes (Sundqvist, 2009; Lindgren and Muñoz, 2013; Peters, 2018; Muñoz, 2020; Leona et al., 2021). However, we did not collect data on productive use of English outside of the classroom (e.g., talking to friends/foreigners, using English abroad, writing messages) because we reckoned that such types of contact with English would not be common in 9- to 12-year-old children with a severe language disorder (cf. Tribushinina et al., 2020). This being said, future research would benefit from more detailed exposure questionnaires documenting both receptive and productive contact with English, as well as language diaries (Sundqvist, 2009).

Finally, our study only included pupils with DLD. As explained above, the underlying mechanisms of L3 advantages may be different in children with and without DLD. For one, positive cross-language transfer of grammar knowledge and metalinguistic awareness that have been put forward as important sources of bilingual advantages in typically-developing populations are presumably not/less available to EFL learners with DLD. Hence, bilingual advantages may be weaker in the DLD group. Alternatively, indirect effects of bilingualism (enhanced cognitive skills and language-learning skills) may weigh more in the absence of direct transfer mechanisms. Future studies directly comparing bilingual effects in children with and without DLD will be crucial to resolving these issues.

Conclusion

This study is the first to reveal that bilingual foreign language learning advantages extend to pupils with DLD. Bilingual children with DLD learning English as a school subject in primary special education outperformed their monolingual peers with DLD on four of the eight EFL measures included in this study (vocabulary, grammar and two measures of syntactic complexity in narratives). At the same time, the bilingual group had smaller vocabularies and poorer grammatical skills in the majority language that was also the language of instruction. Without taking differences in amount of extramural exposure to English into account, we would have overestimated the extent of L3 advantages. Analyses without amount of exposure returned significant differences between bilinguals and monolinguals on all EFL measures except grammatical accuracy of narratives. However, the differences in narrative fluency, lexical diversity and grammaticality judgments became non-significant once exposure was taken into account. Hence, our results demonstrate that it is crucial to control for differences in out-of-school exposure to English when comparing EFL performance of monolinguals and bilinguals.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics assessment committee of the Faculty of Humanities at Utrecht University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

ET: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MM: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (Grant 015.015.061) to ET.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the reviewers for their constructive feedback. We also would like to thank the participating schools, parents, and children that made this investigation possible. Joyce Meuwissen, Desiree Mastellone, Esther Paasman, and Anna Drukker kindly helped with data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Heritage language support is sometimes available to newcomer pupils attending specialized language classes/schools (Le Pichon et al., 2016). In addition, there are many complementary schools teaching heritage languages and cultures, usually during the weekend (e.g., Palmen, 2016). More recently, the national policy regarding multilingualism and heritage language use at school has changed towards a more inclusive approach (e.g., https://www.curriculum.nu), but implementations of this policy are still scarce (e.g., Stolvoort et al., 2023). The participants of the present study did not receive any heritage language support at their school.

References

Abu-Rabia, S., and Sanitsky, E. (2010). Advantages of bilinguals over monolinguals in learning a third language. Biling. Res. J. 33, 173–199. doi: 10.1080/15235882.2010.502797

Adlof, S. M., Baron, L. S., Bell, B. A., and Scoggings, J. (2021). Spoken word learning in children with developmental language disorder or dyslexia. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 64, 2342–2749. doi: 10.1044/202_JSLHR-20-00217

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1406.5823

Bezcioglu-Goktolga, I., and Yagmur, K. (2017). Home language policy of second-generation Turkish families in the Netherlands. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 39, 44–59. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2017.1310216

Bialystok, E. (2001). Metalinguistic aspects of bilingual processing. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 21, 169–181. doi: 10.1017/S0267190501000101

Bialystok, E. (2017). The bilingual adaptation: how minds accommodate experience. Psychol. Bull. 143, 233–262. doi: 10.1037/bul0000099

Bialystok, E., and Barac, R. (2012). Emerging bilingualism: dissociating advantages for metalinguistic awareness and executive control. Cognition 122, 67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.08.003

Bishop, D. V. M. (2017). Why is it so hard to reach agreement on terminology? The case of developmental language disorder (DLD). Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 52, 671–680. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12335

Blom, E. (2019). Domain-general cognitive ability predicts bilingual children’s receptive vocabulary in the majority language. Lang. Learn. 69, 292–322. doi: 10.1111/lang.12333

Blom, E., and Boerma, T. (2017). Effects of language impairment and bilingualism across domains. Linguistic Appr. Biling. 7, 277–300. doi: 10.1075/lab.15018.blo

Blom, E., Boerma, T., Bosma, E., Cornips, L., and Everaert, E. (2017). Cognitive advantages of bilingual children in different sociolinguistic contexts. Front. Psychol. 8:552. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00552

Blom, W. B. T., Boerma, T. D., and de Jong, J. (2020). Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives (MAIN) adapted for use in Dutch. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 64, 2–41. doi: 10.21248/zaspil.64.2020.557

Blom, E., Küntay, A. C., Messer, M., Verhagen, J., and Leseman, P. (2014). The benefits of being bilingual: working memory in bilingual Turkish-Dutch children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 128, 105–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2014.06.007

Blom, E., and Paradis, J. (2015). Sources of individual differences in the acquisition of tense inflection by English second language learners with and without specific language impairment. Appl. Psycholinguist. 36, 953–976. doi: 10.1017/S014271641300057X

Boogaart, R. (1999). Aspect and temporal ordering: A constrastive analysis of Dutch and English. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Brohy, C. (2001). Generic and/or specific advantages of bilingualism in a dynamic plurilingual situation: the case of French as official L3 in the school of Samedan (Switzerland). Int. J. Biling. Edu. Biling. 4, 38–49. doi: 10.1080/13670050108667717

Bruinsma, G., Wijnen, F., and Gerrits, E. (2023). Language gains in 4–6-year-old children with developmental language disorder and the relation with language profile, severity, multilingualism and non-verbal cognition. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 58, 765–785. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12821

Cenoz, J., and Valencia, J. F. (1994). Additive trilingualism: evidence from the Basque Country. Appl. Psycholinguist. 15, 195–207. doi: 10.1017/S0142716400005324

Chamorro, G., and Janke, V. (2022). Investigating the bilingual advantage: the impact of L2 exposure on the social and cognitive skills of monolingually-raised children in bilingual education. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 25, 1765–1781. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2020.1799323

Clyne, M., Hunt, C. R., and Isaakidis, T. (2004). Learning a community language as a third language. Int. J. Multiling. 1, 33–52. doi: 10.1080/14790710408668177