- 1Centre for Research in Autism and Education (CRAE), IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Ambitious about Autism, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: In 2014, changes to special educational needs and disability (SEND) legislation were introduced in England and Wales. These reforms aimed for young people and their families to receive the help and support they need, have a say regarding their support needs, and achieve better outcomes.

Methods: We examine the views of parents of autistic young people (16–25 years) regarding the impact of the reforms, several years after their introduction. In total, 115 parents of autistic young people (16–25 years) in England and Wales took part in our research: 84 completed an online survey, one took part in an interview, and 30 participated in both the survey and interview. Quantitative data, collected via the online survey, were analyzed descriptively. Qualitative data, collected via the survey and interview, were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results: Parents overwhelmingly reported that their experiences had not improved since the introduction of the SEND reforms. This experience impacted their own, and their children’s, wellbeing. Parents felt that the reforms were simply delaying the inevitable, and there was still limited support for them or their children as they transitioned to adulthood.

Discussion: Despite promises of a radically different system, and the potential of these reforms, parents reported that little had changed for them or their children since the introduction of the Children and Families Act.

Introduction

Parents/carers (henceforth, parents) can play a crucial role in supporting and advocating for their autistic1 children from a very early age. Given the lengthy, stressful, and time-consuming autism diagnostic process (Carlsson et al., 2016; Crane et al., 2016, 2018; Eggleston et al., 2019), parents feel a sense of urgency with regard to accessing appropriate educational support for their children (Boshoff et al., 2018). Yet several challenges have been reported in this regard. First, determining the most appropriate educational setting2 for autistic young people is ‘notoriously difficult’ (McNerney et al., 2015, p. 1096), as well as stressful, bureaucratic and time consuming (Tissot, 2011). Second, parents express a desire to work with, rather than against, education providers; yet their negative experiences, and sometimes conflicting priorities, often challenge this desire (Renty and Roeyers, 2006; Azad and Mandell, 2016). Third, while parents are considered ‘essential partners’ (Azad and Mandell, 2016, p. 435) in the education of autistic young people, they often have little influence in educational decision-making (Bacon and Causton-Theoharis, 2013). Eliciting parental views is crucial, as the support young people receive is strongly associated with whether they have parents who can advocate on their behalf (Sales and Vincent, 2018). While challenging for all parents, the reliance on parental advocacy may disadvantage families from certain cultural (Jegatheesan et al., 2010) and/or socio-economic (Lalvani, 2012) backgrounds, in particular.

Little is known about parental views and experiences of the educational support provided to autistic young people during a particularly critical time in their lives: the transition to adulthood (16 to 25 years). During this time, parents take on the dual roles of coordinator (e.g., arranging meetings with relevant organizations; planning and securing post-school options; applying for financial support; researching necessary supports and services) and life-supporter (e.g., ensuring the young person is occupied; organizing leisure activities; taking responsibility for domestic tasks; supporting financial management) (Spiers, 2015). While parents welcome the opportunity to play a key role in their children’s lives, these roles can take a huge emotional toll, impacting parents’ mental and physical health (Spiers, 2015). Parents also lament how this situation often arises from a lack of support from statutory services (Mitchell and Beresford, 2014; Cribb et al., 2019).

In England and Wales, the landscape of post-16 education for young people with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND), including autism, changed significantly with the introduction of the Children and Families Act 2014 (Department for Education, 2014) and the associated SEND Code of Practice (Department for Education and Department of Health, 2015). Norwich and Eaton (2015) summarized the key principles of the legislation as: (1) involving children, young people and parents in decision making, (2) early identification of need and provision, (3) more choice and control for young people and parents about support, (4) collaboration between education, health, and social care providers for support, and (5) excellent provision. Key changes included the potential for SEND services to be extended to 25 years of age, and the introduction of Education Health and Care (EHC) plans. EHC plans are documents that detail a young person’s education, health and care needs as well as the support that they are legally entitled to, and are designed to be a collaborative effort between education, health, and social care services. However, in practice, the onus for EHC plans falls disproportionately on education staff (see Boesley and Crane, 2018). Notably, autism is the most common primary need listed on EHC plans (Department for Education, 2022), despite education professionals experiencing challenges in accessing EHC plans for this group. For example, research has shown that when autistic young people are achieving academically, their needs in other areas may be overlooked by the professionals who work with them (Boesley and Crane, 2018).

Few studies have sought parental views on the impact of these legislative reforms on children and young people with SEND, including autism. Early research with families who participated in a ‘pathfinder’ pilot program was encouraging. In a sample of nearly 700 families (whose children had a range of SEND), Thom et al. (2015) reported improvements for families across a wide range of areas, particularly in terms of their views being sought, listened to, and acted on (see also Adams et al., 2017). Likewise, parental satisfaction with the overall process of getting an EHC plan was fairly high and was reported to lead to the provision of appropriate support (Adams et al., 2017). Less positive feedback was obtained via a survey conducted by the National Autistic Society (2015), which focused exclusively on autistic children and young people. Here, parents emphasized the potential of the reforms and commended the principles behind them but explained how they were still having to ‘fight’ to access timely support for their children. While this sample was self-selecting (which may have led to parents with particularly negative experiences taking part), it is notable that a high number of tribunals (whereby parents appeal against decisions made by Local Authorities, i.e., local governments) feature cases involving autistic children and young people (Sales and Vincent, 2018), suggesting that this group may have particularly challenging experiences of accessing appropriate educational support.

The aim of the current research was to examine stakeholder perceptions regarding the impact of the SEND reforms on 16- to 25-year-old autistic people. In two previous studies, we reported on the perspectives of young people themselves (Crane et al., 2021a) and educators in specialist settings (Crane et al., 2021b). Here, we examine the perspectives of parents, who autistic young people have reported to be crucial advocates in facilitating access to support (Crane et al., 2021a). We structured our research questions around three key aspects of the reforms:

Help and support

1. Do parents know what support is available to them and their children up until the age of 25 years, and where to access this?

2. Do parents of autistic young people feel they and/or their children get the support they need?

3. What are parents’ experiences regarding the barriers and facilitators to useful support for their children?

Having a say

1. Do parents of autistic young people feel they get a say in the choices and support that their children are offered up until the age of 25 years?

2. What are parents’ experiences regarding EHC plans?

3. Do parents of autistic young people feel their problems are taken seriously and that any problems get resolved?

Getting better outcomes

1. Are parents of autistic young people satisfied with their children’s educational journeys and final destinations?

2. Do parents feel that schools and school staff (including specialist autism staff) have the skills to support autistic young people in achieving their ambitions?

Methods

Design

Parents were invited to participate in an online survey (comprising closed and open-ended questions) to address their views on the impact of the SEND reforms. Upon completion of the survey, parents could register their interest in taking part in a follow-up interview. Interviews afforded the in-depth exploration of perceptions and experiences, with the researchers able to probe ‘beyond the surface’.

Participants

To take part in the study, participants needed to be the parent of a child that was (1) 16–25 years of age, (2) autistic (whether formally diagnosed or self-identifying) and (3) in England or Wales. The research was advertised via national autism charities, social media, and personal contacts of the research team, for eight weeks between January and March 2020.

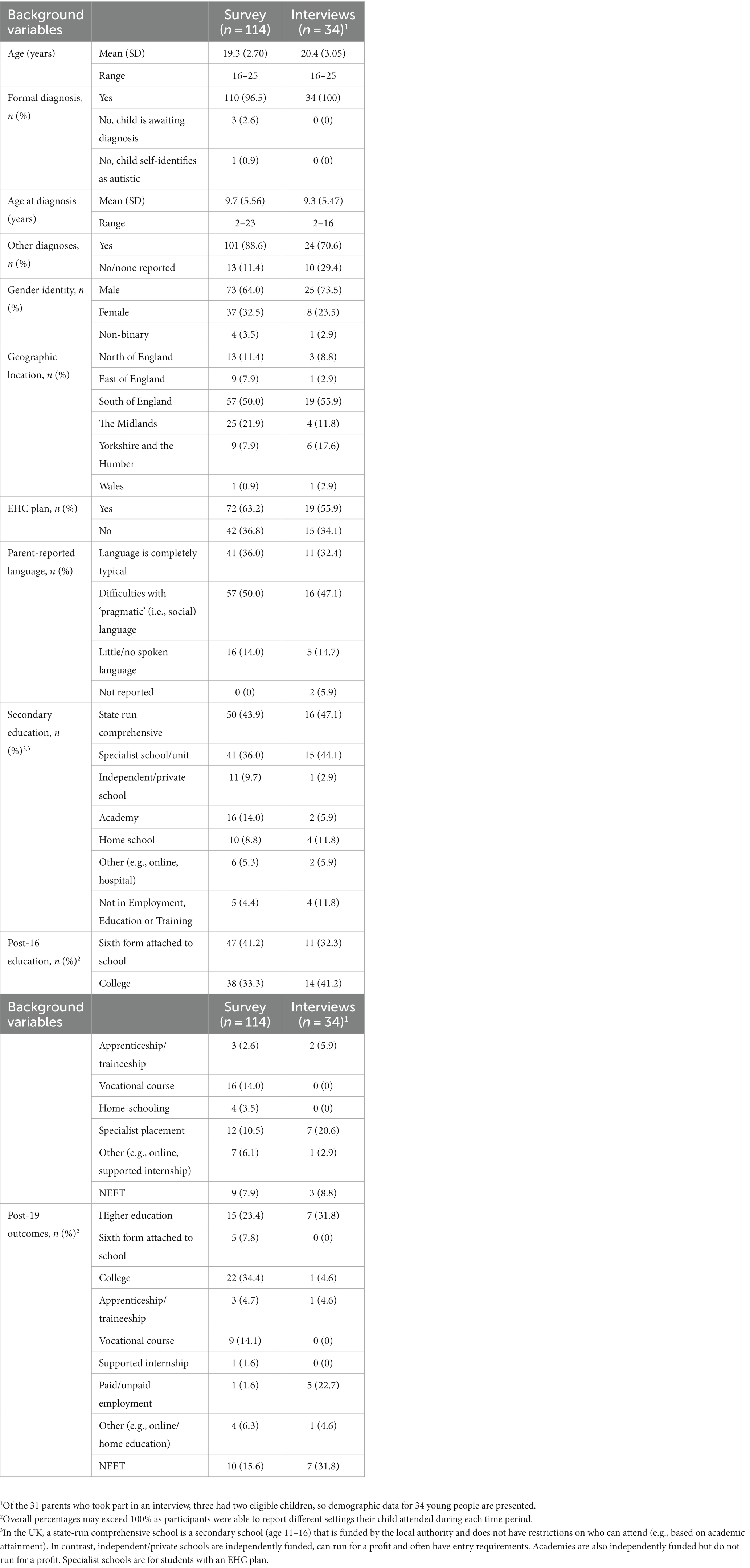

In total, 145 parents engaged with the survey, yet 31 (21%) cases were removed during data screening: 29 parents (20%) did not proceed past the demographic information and two (1%) had children who had not yet finished their secondary education. The final survey sample comprised 114 parents. Of these, most had children with a formal autism diagnosis (n = 110, 96%) and at least one additional diagnosis (n = 101, 89%). Most common additional diagnoses included affective conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression) (n = 56, 55%) and learning difficulties (e.g., dyslexia) (n = 48, 48%). Sixty-four children (56%) were 19 years or older and had experienced post-19 education.

Thirty parents who completed the survey also participated in a semi-structured interview (along with one further parent, who saw the advertisement for the research and requested to participate in an interview but not complete the survey). The final interview sample therefore comprised 31 parents (of 34 autistic young people). Of these, all children had a formal autism diagnosis (n = 34, 100%) and most had at least one additional diagnosis (n = 24, 71%). Most common additional diagnoses included affective conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression) (n = 10, 42%) and intellectual disability (n = 7, 29%). Twenty-two young people (65%) were aged 19 years or older and had experienced post-19 education.

Demographic data of the parents’ autistic children are presented in Table 1. We did not collect demographic data of the parents since we were keen not to make our data collection overly onerous for parents, and we were especially interested in ensuring that a range of autistic young people were reported on in the research.

Materials

A survey and interview guide were developed in collaboration with a group of autistic young people from the UK charity Ambitious about Autism.3 The survey collected top-level qualitative and quantitative data, while the interviews allowed for more in-depth exploration of parents’ views and experiences. Both the survey and interview guide were organized into four sections. Section One asked parents for demographic information about their child (e.g., age, gender identity, location, diagnostic information, parent-reported language abilities), to characterize the sample of young people that were being discussed. Section Two asked parents to reflect on the help/support they and their children received post-16 (e.g., support in deciding what to do post-16, the transition to post-16) and, where applicable, post-19 (e.g., support available, whether they experienced any barriers to accessing support and any particularly useful support). Section Two also focused on parents’ experiences with their Local Offer4 (whether they know what is in it, whether they are happy with it, and whether they have received any additional support via it). Section Three focused on parents’ understanding of the rights and entitlements that young people with SEND and their families have access to, because of the Children and Families Act 2014. Specifically, parents were asked about their experiences with their Local Authority (e.g., if they are told about their Local Offer, if they feel listened to, if their problems are taken seriously and fixed, and if they get a choice in the support offered to them). Where applicable, participants were asked about their experiences with EHC plans (e.g., knowledge of/satisfaction with content, degree of involvement, whether it has been updated). Section Four asked parents about how satisfied they are with their children’s post-16 provision (whether they are satisfied, whether their children’s educational outcomes align with their ambitions, and whether they feel that staff working with their children have the right skills to support them). Survey and interview questions are presented as Supplementary material.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained via the Research Ethics Committee at IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society, with research conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was gained from all parents prior to participation. The online survey was administered by Qualtrics and took approximately 30 min to complete. Interviews were conducted over the phone (n = 27, 87%), via instant messenger (n = 2, 6%), face-to-face (n = 1, 3%) or via video call (n = 1, 3%) depending on the interviewees’ preference and availability. Verbal interviews lasted an average of 48 min (SD = 14.07, range = 27–80 min) with instant messenger interviews taking longer. Verbal interviews were digitally recorded with participants’ prior consent and transcribed verbatim. Due to overlap in the qualitative data from the online survey and semi-structured interviews (which was expected given that the questions in both the survey and interviews covered the same topics), all qualitative data were considered together. Adopting a critical realist framework, analyses involved identifying both semantic and latent meanings in the dataset, following an inductive approach to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2013, 2019). Analyses involved recursively proceeding through the stages of data familiarization, coding, theme development and review. Analysis was led by two authors that conducted the interviews (JD & AF), with KP also reading a subset of the open-ended survey responses and independently coding the data. With support from LC and AR, JD and AF reviewed the results, merging and refining broader semantic themes to agree on a final set of distinct themes and subthemes. Quantitative survey data are presented descriptively (n, %).

Results

Quantitative (survey) data

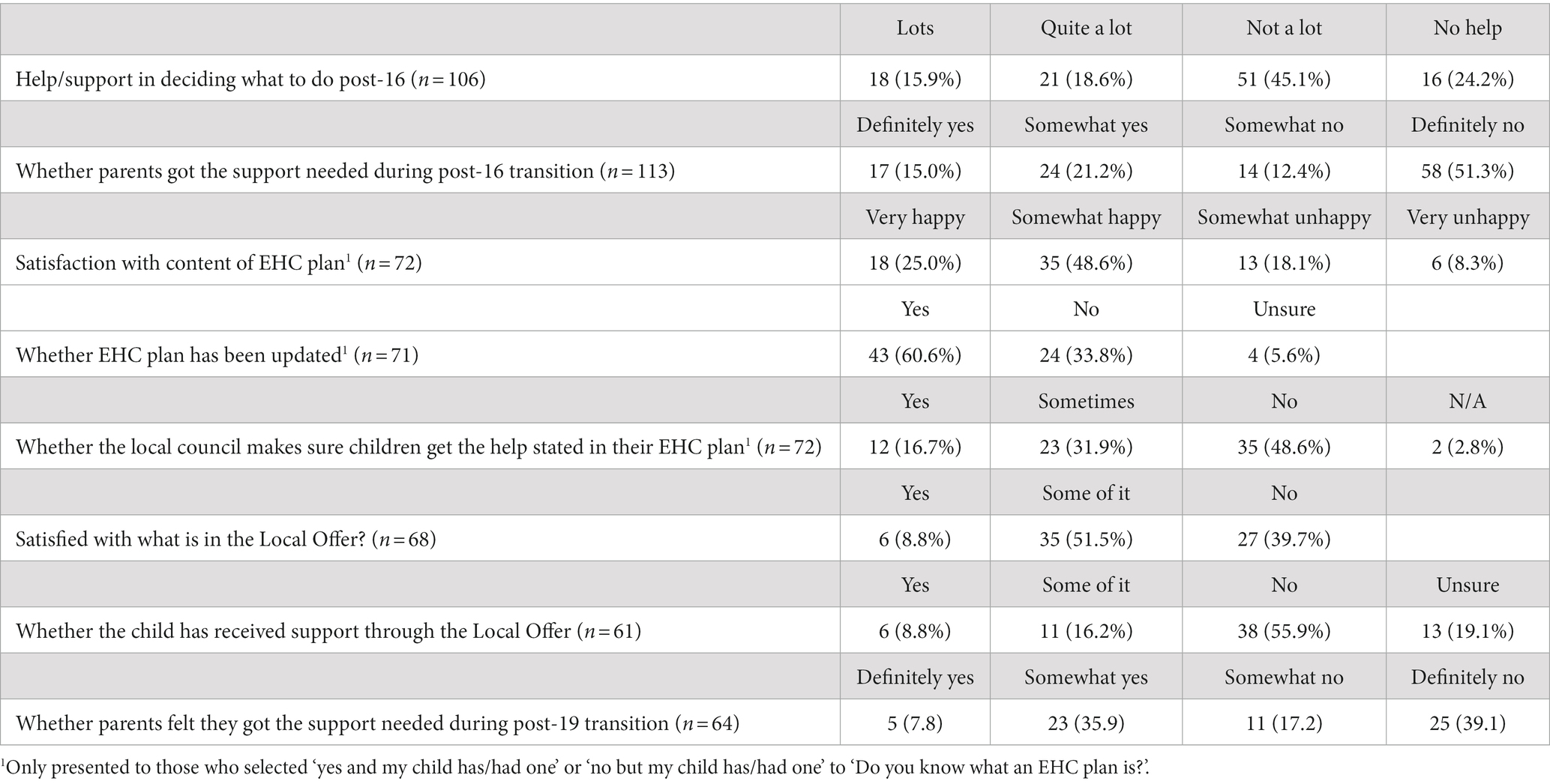

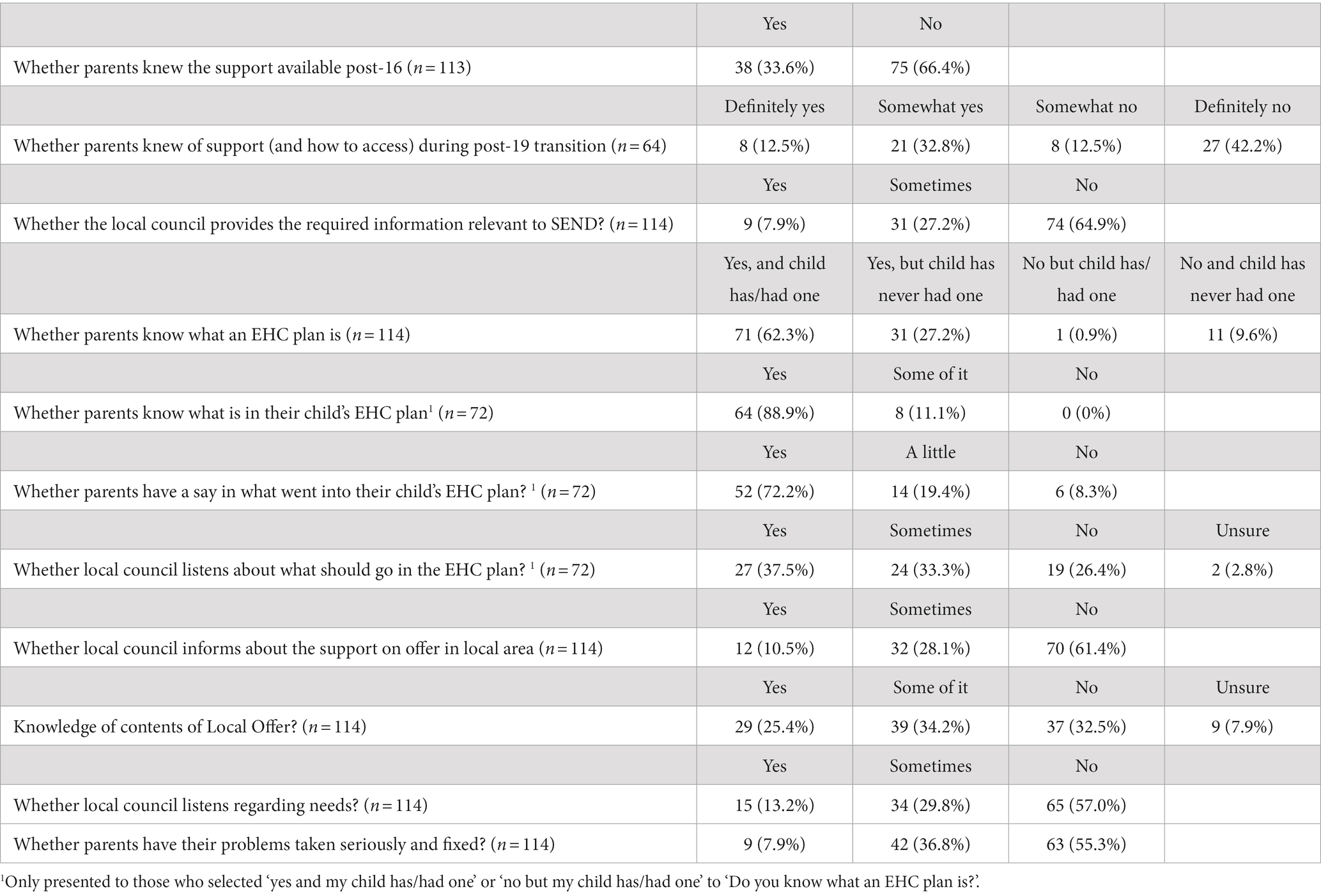

Parents’ experiences of help and support in post-16 education (see Table 2)

Almost two thirds of parents reported that they (n = 72, 64%) and their children (n = 67, 63%) had little or no support when deciding what to do post-16. Regarding EHC plans, 53 (74%) were at least somewhat happy with what it contained. Most (n = 43, 61%) reported that the EHC plan had been updated since it was first made, yet 35 (49%) said that their Local Authority did not ensure that their child received the support set out in their plan. Regarding the Local Offer, just 6 (9%) were happy with what it comprised: 35 (52%) were positive about some of the Offer, but 27 (40%) were not happy with it at all. Only a quarter (n = 17, 25%) reported their child(ren) accessing support in the Local Offer. Sixty-four parents were able to comment on the help and support they and their child(ren) received when transitioning from post-16 to post-19 education. Less than half of these participants (n = 28, 44%) felt that they and their children got the support they needed during this time.

Parents’ experiences of having a say in their child’s help and support (see Table 3)

Two thirds of our sample did not feel well-informed about the post-16 support on offer to their autistic child(ren) (n = 75, 66%). For parents whose child(ren) experienced post-19 provision, 35 (55%) additionally reported not knowing what was available to help their young person transition from post-16 to post-19. Approximately two thirds of parents did not feel that their local council gave them the information they needed about their young person’s SEND (n = 74, 65%) or the support available in the local area (n = 70, 61%). Further, almost a third of participants (n = 37, 32%) did not know what was in their Local Offer (a further nine participants, 8%, were unsure).

Parents were more informed about their children’s EHC plans: most knew what an EHC plan was (n = 102, 89%) and all parents whose child(ren) had an EHC plan (n = 72), knew at least some of what was in it. Most parents reported having at least some say in what went into their child(ren)‘s EHC plan (n = 66, 92%), and felt that their views on the plan were listened to (n = 51, 71%). More generally, over half did not feel that the Local Authority listened to them and their child(ren) (n = 65, 57%) nor that their problems were taken seriously or fixed (n = 63, 55%).

Qualitative (survey and interview) data

Parents’ views were centered around the broad message that nothing has changed. Within this overarching message were three themes: (1) there is still a lack of appropriate provisions and accompanying support; (2) parents still feel they are fighting the system and (3) the onus still lies on parents. [Note: interviewee respondents are denoted with an I; survey respondents with an S.]

Theme 1: there is still a lack of appropriate provisions and accompanying support

Sub-theme 1: ‘There is Nothing Available Locally’

The general perceived lack of appropriate, local post-16 support led to added pressure for parents and sometimes resulted in young people dropping out of school. Even when parents were able to secure a local educational provision for their children, they explained that the setting(s) their children attended (often in mainstream education) were not always able to provide all the support required. The support was seen as ‘very generic and not specific to your young person’ (I5), with the need for individualized, person-centered support emphasized.

Sub-theme 2: lack of key transitional support

Parents noted that during transitions, their children were rarely given information about their options or time to prepare for their new settings: ‘We do not know what’s out there and nobody is helping us find out’ (I5). Parents suggested that young people may benefit from attending taster days at prospective settings, allowing them to familiarize themselves with the environment and make informed choices.

Sub-theme 3: the school environment as a barrier to accessing help and support

Parents perceived schools to have too large of a focus on academic outcomes, resulting in: (1) less academically able students feeling left out (‘the children who were not going to university were pushed to one side and felt that nothing was offered to them’; I12); and (2) academically achieving young people slipping through the net of support: ‘No one gave a monkeys about my child’s suffering because their academic achievement was still on track’ (S76). These issues were attributed to a general lack of knowledge surrounding specific autism-related matters, as well as a lack of funding: ‘[Education settings] do not have the money, they do not have the people to actually dedicate to a small group of children with autism when they are focused on 400 people’s exam results for that year’ (I12).

Sub-theme 4: lack of support outside of education

Even parents who were pleased with the resources that their children’s educational setting provided noted issues in accessing support more generally, highlighting that education cannot support young people alone: ‘My son’s independent ‘school’ has been amazing but then it understands my son’s condition perfectly. Interactions with government departments and our GP during [his post-16 education] were uniquely stressful and unhelpful’ (S5). Partnership between different stakeholders was often deemed unsuccessful, particularly regarding EHC plans: ‘it’s more of an E than an H, C and a P’ (I3). As a result, self-financing support was reported: ‘We have had to pay for private therapy for anxiety and OCD’ (S38). For some families, this involved ‘taking out a loan to pay for them’ (I15).

Parents reported being particularly disappointed with the support that the Local Offer afforded, describing their quality as a ‘postcode lottery’ (I7). The Local Offer was reported to be ‘all aimed at young children’ (I15), leaving those in post-16 with very little provision. This was particularly true for autistic young people: ‘it’s a big effort to try and get [my son] to go to [support groups] because the very nature of the condition means that he does not want to go and meet these new people and join in’ (I12). Parents noted that even if their child(ren) did receive support during their educational journey, the outside world appeared not understanding enough of autism: ‘I almost feel like, well, what was the point of pushing them through this education system? It was almost like torturing them and what use is it in the outside world? It is no use at all, really’ (I6).

Theme 2: ‘I’d Like to Feel Like I Was Working With the Local Authority, Rather Than Against Them’: parents still feel they are fighting the system

Sub-theme 1: ‘The Council See Our Young People as Second Class’

Parents felt that there was a ‘conflict between person-centered planning versus resource-centered planning’ (I30) as local authorities were perceived to have ‘no money to fund anything’ (I26). This experience was felt to have direct ramifications for the support and provisions that young people were able to access. High levels of advocacy were felt to be needed to engage with the Local Authority:

‘I went into the local education office and I said ‘Right, I have researched this and my son is entitled to this, and you have broken this and this and this and this,’ well, the colour drained out of their face and it was suddenly ‘my goodness, we have got one who understands what her rights are and we cannot mess with her” (I6).

Sub-theme 2: ‘[It] Doesn’t Really Carry Any Substance’: the promise versus the reality of EHC plans

Parents welcomed the prospect of an EHC plan and the legal right to support it afforded. However, some parents felt discouraged from applying for an EHC plan and, as a result, reported that their children did not receive the support they needed (and likely would not, given their age): ‘He has limited opportunities due to no EHC plan and stands little chance of getting an EHC plan at 20 years old’ (S31). Consequently, many parents resorted to taking legal action to ensure that their child received adequate support, lamenting: ‘I’d like to feel like I was working with the Local Authority, rather than against them’ (I26). Parents who had managed to secure an EHC plan for their child explained that the agreed support was often not provided: ‘Empty words on a piece of paper that gets filed away, and the points not actioned. The promises broken. The child left hanging’ (S54). While some parents did feel listened to by their Local Authority, this was often perceived to be tokenistic: ‘the EHC plan is just for show but does not really carry any substance’ (S33).

Sub-theme 3: ‘She Really Cared’: specific individuals made a big difference

Those with positive experiences often attributed this outcome to a ‘key champion’, either within the school setting or Local Authority, who was able to meaningfully connect with the family and/or young person. Positive experiences often involved gaining practical support (‘he even did some of his coursework at home, and the school sent out two teachers to literally sit in our dining room to adjudicate. Everyone was amazingly helpful’; I11) or emotional support (‘his Personal Tutor was actually very nice to him that year, very nurturing and gave [him the] confidence to do the second and third term’; I18). Parents also acknowledged the importance of stakeholders understanding autism: ‘There was a member of staff who just seemed to understand…he came to the house and was perfectly accepting that [my child] did not come down and see him’ (I11). Yet, it was also acknowledged that autism training alone was not enough:

‘There’s some people that have all the training with autism that just don’t know how to communicate, and then you’ve got other people that have got no sort of training with autism that just have it, they just know how to communicate with people’ (I28).

Participants explained that when these champions left the system (which was common, given that staff turnover was high), experiences were often tainted: ‘we had whoever it was in our Local Authority who was understanding, then she left…and this is the theme; it goes on, and on…it’s happened a couple of times…a number of changing staff’ (I11).

Theme 3: ‘You have to Be Not Just a Mum, but a Manager’: the onus still lies on parents

Sub-theme 1: advocating on young people’s behalf during, and beyond, transition

Parents felt that they had to advocate on the young person’s behalf during the transition process, as little or no formal support was provided: ‘do not wait for professionals to do stuff, because it’s just not going to happen…I just do it myself’ (I21). Parents highlighted that even if their child had a positive transition experience, it was their own hard work that enabled this. While educational support potentially being extended up until the age of 25 was perceived as helpful, parents felt that this simply delayed the inevitable: ‘it’s created a bit of a safety buffer, which is good, but you have still ultimately got this cliff edge at 25’ (I30). As a result, parents succumbed to the idea that they will have to continue to fight and advocate on their children’s behalf. Parents expressed their apprehension about their child(ren)’s more distant future, when they were no longer around:

‘My husband and I are already having to look at how we can earn as much money as we possibly can so we leave [him] enough to live on for the rest of his life, and it’s terrifying’ (I20).

Sub-theme 2: ‘It Was All Very Confusing and Distressing’: lack of clarity

Many parents did not feel well-informed about their child(ren)’s needs and the support that they could receive, which made advocating on their child(ren)’s behalf challenging: ‘I’m like the blind leading the blind’ (I25). Parents that were aware of their rights felt this was ‘only through personal research and really looking into it, following other people and asking for advice from other places’ (I23). Parents questioned why their rights were not made clearer, sooner. Those who were aware of their rights, questioned their utility: ‘I think we feel we know our rights, but actually when you tell them your rights, nobody pays any attention. Unless you want to go to a lawyer and fight that way, you have had it’ (I5).

Parents recommended that the Local Authority should provide parents with more ‘truthful’ information about their options during transitions:

‘Rather than build-up expectations, it’s about managing the expectations and saying ‘Look, let’s be honest. This is what we’ve got.’ It would be more helpful, and it would then help with the transition’ (I30).

A lack of clarity in the Local Offer was also noted. For example, parents felt that information on the Local Offer was often: (1) out of date: ‘It’s great having a website, only if you can update it’ (I30); (2) unclear: ‘it does not tell you what your child can access or what’s available, because it’s very generic and very woolly’ (I5); (3) hard to navigate: ‘it takes too many clicks to get to where you want’ (I22); and (4) not functional: ‘the links did not work’ (I6). As a result, parents relied on their own research. This research was often conducted via the internet (‘The internet is a marvelous source of information’; I21), conversations with charities, and/or other parents or support groups (‘The best source of information is from other parents, preferably parents who have a child with similar needs’; I19).

Sub-theme 3: ‘Sometimes I’m Too Tired to Fight’: parents are exhausted, and it impacts their wellbeing

Parents explained that advocating for their child(ren) required vast amounts of time, knowledge, skills, support, and money; expressing concern for others who did not have such resources: ‘people who are working and they might have more than one child, they will not have time to do this’ (I13). Advocacy negatively impacted parents’ wellbeing and the constant ‘fighting’ left many parents exhausted: ‘You’ve got to choose your battles. You have not got the energy to fight every single battle’ (I28).

Discussion

In 2014, ambitious reforms were introduced to improve the experiences of pupils with SEND and their families in England and Wales. Focusing specifically on parents of autistic young people (16–25 years), our analyses demonstrated that most parents’ felt that their experiences had not improved since the introduction of the reforms. Parents feel that there is still a general lack of help and support for their children, that they still have to fight to gain access to any support that is available, and that the onus still lies on them to find, secure, and provide support. Years of fighting for access to help and support, however, meant that many parents reached a point of exhaustion, impacting not only their own, but also their children’s, wellbeing. This was particularly concerning at this critical time in their children’s lives. Parents felt that the reforms were simply delaying the inevitable: the ‘cliff-edge’ had been pushed back (potentially up to 25 years), and there was simply no formal support for their children as they transitioned to adulthood.

Our findings align closely with previous research that has considered parental views on the impact of the SEND reforms. Our data demonstrated that some aspects of the reforms were perceived favorably by parents: parents felt that they, and their children, had a say in their education, and that their views were listened to (cf. Thom et al., 2015), particularly in relation to EHC plans (cf. Adams et al., 2017). Yet several areas of dissatisfaction were noted. These included general issues, such as a lack of support provided to young people and their families, a lack of effective partnership between different sectors (education, health, social care), and the burden of advocating for support falling on parents (cf. National Autistic Society, 2015). Further, there were issues specific to particular aspects of the SEND reforms, including dissatisfaction with the Local Offer (with parents noting that it tended to be out of date, unclear, hard to navigate and not functional) and the EHC plan process (with parents lamenting how their children did not always receive the support set out in their plans).

A key question is whether these results are specific to autistic young people. Many of the issues noted in this research have been documented in relation to young people with broader SEND (e.g., Adams et al., 2017), yet some aspects may be particularly pertinent for those who are autistic. First, our parents discussed the need for more transitional support, given the challenges autistic young people may experience in relation to change. While there has been growing interest in identifying ways to support autistic young people at earlier transition points (e.g., primary to secondary school; Mandy et al., 2016), there is a need for evidence-based holistic support during the move to adulthood. Second, our sample emphasized the need for support to be more individualized, to address the needs of all autistic people. Particularly for young people in mainstream settings, parents explained how several subsets of autistic young people were having their needs overlooked: if young people were performing well academically, their needs were not recognized (irrespective of the toll this could be taking on them and their mental health); if their children were struggling academically, no support or guidance was available to them (meaning they were not able to achieve the same outcomes as other pupils) (see also Boesley and Crane, 2018).

A further important consideration is whether these challenges for autistic young people are unique to post-16 education. The difficulties that autistic young people face throughout education have been well-documented (e.g., Brede et al., 2017; Sproston et al., 2017), and the current findings suggest that these challenges continue into post-16 education. This includes difficulties accessing help and support, young people’s individual needs not being addressed, and a lack of clarity regarding young people’s entitlements. Previous research has demonstrated that parents’ key concern for their autistic children regards their futures, especially given the paucity of adult services (Cribb et al., 2019) and worries about who would be able to support children when parents were no longer around (Wittemeyer et al., 2011). Our sample of parents felt that the reforms had simply delayed the inevitable: parents told us that their children would still leave school unprepared for the next stages of their lives, and the limited formal support received meant that young people will still have to rely heavily on parental support as they transitioned to adulthood. As well as the needs of pupils being unmet, this issue was also felt to impact on the wellbeing of parents. Although parents of autistic children are known to have particularly high levels of stress and mental ill-health (e.g., Lai et al., 2015; Bonis, 2016), these issues may be particularly pronounced in post-16 education, when the prospect of life after school becomes an impending reality. It is, therefore, essential that age-appropriate support is available, accessible, and clearly signposted for autistic young people in the transition to adulthood.

Our current data presents a bleak picture in terms of the experiences of, and support provided to, autistic young people and their families. Yet it is crucial to focus not only on the challenges they face, but also what works well. In this regard, parents emphasized the importance of having a ‘key champion’ who meaningfully connected with the young person and their family. Indeed, the importance of building professional relationships based on trust and mutual respect has been well-documented in relation to several areas of good autism practice (e.g., Sproston et al., 2017; Crane et al., 2019). Parents emphasized the importance of this ‘key champion’ understanding autism; indeed, autism training is commonly advocated as a crucial facilitator to best practice for those working with autistic young people (e.g., All Party Parliamentary Group on Autism, 2017). Yet, it was acknowledged that autism training may be less important than having excellent communication skills; as one parent in our sample noted, some people ‘just have it, they just know how to communicate with people’. This observation may relate to how autism training often focuses on facts about autism, rather than how to build empathetic relationships with autistic people and their families. Given that other key characteristics of these champions were the ability to provide practical and emotional support, it is apparent that training on supporting autistic people and families must move away from generic autism awareness and more toward relational aspects of support. A link between success stories and individual champions is concerning, however, as it suggests there is a lack of consistency in approach: any positive outcomes are fragile and transient, all dependent on the involvement of one person. Further, the high staff turnover noted by parents demonstrated that reliance on one individual was not a viable long-term solution. To address this issue, we must learn from successful outcomes and aim to distil the components that lead to this success; using these case studies as best-practice examples to encourage others.

The constant figures in the lives of many autistic young people, and often their most continual champions, are their parents. As a result, our sample of parents explained how the burden for the provision of support was falling on them. This situation is troubling for two reasons: first, due to the huge emotional toll providing this support takes; and second, due to the huge inequalities this situation causes (since not all parents are in a position to be able to advocate for their children’s needs, and not all young people have traditional parental support). Parents discussed how those who managed to achieve successful outcomes and be awarded support were likely to be those in privileged situations, allowing them the time, energy, and influence to champion their children’s needs. Great empathy was shown for those who may not be as fortunate.

The situation is further complicated because parents are fighting incredibly hard, but it is unclear whether Local Authorities in England and Wales can actually offer parents what they want. Many parents spoke about the high expectations they had of radical change, but these changes did not transpire. Parents urged to be told the truth, even if it was unpalatable, rather than being overpromised. This situation could have knock-on effects on parental mental health and wellbeing too; if parents know that services are unavailable, they may not internalize failures to access help and support for their young people.

This research is not without its limitations. First, our data were collected in early 2020, meaning they may not reflect the most recent developments and changes in the implementation of the Children and Families Act. Second, our sample was self-selecting, meaning that those who participated may have been those most dissatisfied with the SEND reforms. Yet highlighting negative examples is essential to better understand how and why issues arise, ensuring that lessons are learnt (and not repeated). Third, our sample comprised parents who were able to access an online survey and/or participate in a written/verbal interview. As such, some of the most vulnerable groups in terms of accessing help and support (e.g., those who could not communicate in English) were not represented in our sample and we may have underestimated some of the barriers faced by these parents of autistic young people. Targeted research addressing underrepresented groups will be an important future direction.

To conclude, our evaluation of the impact of the SEND reforms highlights that parents of autistic young people in England and Wales were promised a radically different system yet felt that little has changed: parents are still struggling to access help and support for their children, feel that their concerns are not being addressed and, ultimately, that this hinders their children from achieving optimal adult outcomes. Based on our findings, we recommend: (1) prioritizing transitional support for autistic young people from an early stage in their educational journeys; (2) the provision of clear guidance regarding what help and support autistic young people are eligible for, and what pathways are available to them, with Local Authorities setting realistic expectations for parents; (3) the provision of high quality training for staff in mainstream and special schools, to ensure that all children get appropriate support (irrespective of academic achievement); (4) moving away from a focus on key ‘champions’ toward learning from these success stories and using these to encourage and train others (e.g., in more relational forms of support); and (5) a system designed on the basis of equity - ensuring that every autistic young person, irrespective of family background, can access high quality support and achieve their goals.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because consent was not sought to share data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bC5jcmFuZUB1Y2wuYWMudWs=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the UCL IOE Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LC: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition. JD: investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. AF: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. KP: methodology, formal analysis, and writing – review & editing. SO’B: writing—review and editing. AW: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. AR: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was commissioned and funded by the Department for Education and the Autism Education Trust.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Amy, Ibrahim, and Robbie (from Ambitious about Autism) for their contributions to this research, as well as the parents who shared their experiences.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1250018/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^We use identity-first (i.e., autistic) rather than person-first (i.e., with autism) language, as this is preferred by most autistic people in the United Kingdom (Kenny et al., 2016) and is less associated with stigma (Gernsbacher, 2017) and ableism (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2020).

2. ^In England and Wales, there are a variety of educational options available for autistic young people, including mainstream schools (where autistic young people, as well as those with other special educational needs and disabilities, are educated alongside non-autistic peers), special schools (where autistic young people are educated alongside other autistic young people, or those with other disabilities) or specialist bases within mainstream schools (where autistic young people benefit from both access to inclusive classes, as well as specialist input for autistic/disabled young people).

3. ^Ambitious about Autism provide a range of services to autistic young people and their families in the UK, including information, practical support, and specialist education and employment program. Central to their work is the involvement of autistic young people, such as through their Online Youth Network and Youth Council.

4. ^A Local Offer gives children and young people with SEND and their families information about what support services the Local Authority think will be available in their local area.

References

Adams, L., Tindle, A., Basran, S., Dobie, S., Thomson, D., Robinson, D., et al. (2017). Experiences of education, health and care plans: a survey of parents and young people. London: Department for Education.

All Party Parliamentary Group on Autism (2017). Autism and education in England 2017. London: All Party Parliamentary Group on Autism (APPGA).

Azad, G., and Mandell, D. S. (2016). Concerns of parents and teachers of children with autism in elementary school. Autism 20, 435–441. doi: 10.1177/1362361315588199

Bacon, J. K., and Causton-Theoharis, J. (2013). ‘It should be teamwork’: a critical investigation of school practices and parent advocacy in special education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 17, 682–699. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.708060

Boesley, L., and Crane, L. (2018). ‘Forget the health and care and just call them education plans’: SENCO s' perspectives on education, health and care plans. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 18, 36–47. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12416

Bonis, S. (2016). Stress and parents of children with autism: a review of literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 37, 153–163. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1116030

Boshoff, K., Gibbs, D., Phillips, R. L., Wiles, L., and Porter, L. (2018). Parents' voices: ‘our process of advocating for our child with autism.’ A meta-synthesis of parents' perspectives. Child Care Health Dev. 44, 147–160. doi: 10.1111/cch.12504

Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., and Hand, B. N. (2020). Avoiding Ableist language: suggestions for autism researchers. Autism Adulthood 3, 18–29. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.0014

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013) Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exer. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676x.2019.1628806

Brede, J., Remington, A., Kenny, L., Warren, K., and Pellicano, E. (2017). Excluded from school: autistic students’ experiences of school exclusion and subsequent re-integration into school. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2:239694151773751. doi: 10.1177/2396941517737511

Carlsson, E., Miniscalco, C., Kadesjö, B., and Laakso, K. (2016). Negotiating knowledge: parents’ experience of the neuropsychiatric diagnostic process for children with autism. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 51, 328–338. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12210

Crane, L., Adams, F., Harper, G., Welch, J., and Pellicano, E. (2019). ‘Something needs to change’: experiences of mental health in young autistic adults. Autism 23, 477–493. doi: 10.1177/1362361318757048

Crane, L., Batty, R., Adeyinka, H., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., and Hill, E. L. (2018). Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 3761–3772. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3639-1

Crane, L., Chester, J. W., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., and Hill, E. (2016). Experiences of autism diagnosis: a survey of over 1000 parents in the United Kingdom. Autism 20, 153–162. doi: 10.1177/1362361315573636

Crane, L., Davies, J., Fritz, A., O’Brien, S., Worsley, A., Ashworth, M., et al. (2021a). The transition to adulthood for young autistic people: the views and experiences of education professionals in special schools. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 48, 323–346. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12372

Crane, L., Davies, J., Fritz, A., O’Brien-Quilty, S., Worsley, A., and Remington, A. (2021b). Autistic young people’s experiences of transitioning to adulthood following the children and families act 2014. Br. Educ. Res. J. 48, 22–48. doi: 10.1002/berj.3753

Cribb, S., Kenny, L., and Pellicano, E. (2019). ‘I definitely feel more in control of my life’: the perspectives of autistic young people and their parents on emerging adulthood. Autism 23, 1765–1781. doi: 10.1177/1362361319830029

Department for Education. (2022). Special educational needs and disability: An analysis and summary of data sources, GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sen-analysis-and-summary-of-data-sources (Accessed August 4, 2023).

Department for Education and Department of Health. (2015). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. London: HMSO.

Eggleston, M. J., Thabrew, H., Frampton, C. M., Eggleston, K. H., and Hennig, S. C. (2019). Obtaining an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis and supports: New Zealand parents experiences. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 62, 18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.02.004

Gernsbacher, M. A. (2017). Editorial perspective: the use of person-first language in scholarly writing may accentuate stigma. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 859–861. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12706

Jegatheesan, B., Miller, P. J., and Fowler, S. A. (2010). Autism from a religious perspective: a study of parental beliefs in south Asian Muslim immigrant families. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 25, 98–109. doi: 10.1177/1088357610361344

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., and Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism 20, 442–462. doi: 10.1177/1362361315588200

Lai, W. W., Goh, T. J., Oei, T. P. S., and Sung, M. (2015). Coping and well-being in parents of children with autism Spectrum disorders (ASD). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 2582–2593. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2430-9

Lalvani, P. (2012). Parents' participation in special education in the context of implicit educational ideologies and socioeconomic status. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 47, 474–486.

Mandy, W., Murin, M., Baykaner, O., Staunton, S., Hellriegel, J., Anderson, S., et al. (2016). The transition from primary to secondary school in mainstream education for children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 20, 5–13. doi: 10.1177/1362361314562616

McNerney, C., Hill, V., and Pellicano, E. (2015). Choosing a secondary school for young people on the autism spectrum: a multi-informant study. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 19, 1096–1116. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2015.1037869

Mitchell, W., and Beresford, B. (2014). Young people with high-functioning autism and Asperger's syndrome planning for and anticipating the move to college: what supports a positive transition? Br. J. Spec. Educ. 41, 151–171. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12064

National Autistic Society (2015). School report 2015: A health check on how well the new special educational needs and disability (SEND) system is meeting the needs of children and young people on the autism spectrum. London: National Autistic Society.

Norwich, B., and Eaton, A. (2015). The new special educational needs (SEN) legislation in England and implications for services for children and young people with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. J. Emotl. Behav. Diff. 20, 1741–2692. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2014.989056

Renty, J., and Roeyers, H. (2006). Satisfaction with formal support and education for children with autism spectrum disorder: the voices of the parents. Child Care Health Dev. 32, 371–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00584.x

Sales, N., and Vincent, K. (2018). Strengths and limitations of the education, health and care plan process from a range of professional and family perspectives. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 45, 61–80. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12202

Spiers, G. (2015). Choice and caring: the experiences of parents supporting young people with autistic spectrum conditions as they move into adulthood. Child. Soc. 29, 546–557. doi: 10.1111/chso.12104

Sproston, K., Sedgewick, F., and Crane, L. (2017). Autistic girls and school exclusion: perspectives of students and their parents. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2:2396941517706172. doi: 10.1177/2396941517706172

Thom, G., Lupton, K., Craston, M., Purdon, S., Bryson, C., Lambert, C., et al. (2015) The special educational needs and disability pathfinder programme evaluation. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/448156/RR471_SEND_pathfinder_programme_final_report.pdf (Accessed August 4, 2023).

Tissot, C. (2011). Working together? Parent and local authority views on the process of obtaining appropriate educational provision for children with autism spectrum disorders. Educ. Res. 53, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2011.552228

Keywords: autism, parents, policy, reform, post-16 education

Citation: Crane L, Davies J, Fritz A, Portman K, O’Brien S, Worsley A and Remington A (2023) ‘I can’t say that anything has changed’: parents of autistic young people (16–25 years) discuss the impact of the Children and Families Act in England and Wales. Front. Educ. 8:1250018. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1250018

Edited by:

David Lansing Cameron, University of Agder, NorwayReviewed by:

Lila Kossyvaki, University of Birmingham, United KingdomDario Ianes, Università Bolzano, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Crane, Davies, Fritz, Portman, O’Brien, Worsley and Remington. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Crane, bC5jcmFuZUB1Y2wuYWMudWs=

†Present addresses: Anne Fritz,King’s College London, London, United Kingdom; Sarah O’Brien, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

Laura Crane

Laura Crane Jade Davies1

Jade Davies1 Kerrie Portman

Kerrie Portman Anna Remington

Anna Remington