94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 18 October 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1239619

This article is part of the Research TopicSexuality education that prioritizes sexual well-being: Initiatives and impactView all 11 articles

Introduction: Poor ovulatory menstrual (OM) health experiences and low levels of OM health literacy compromise the future adult health and wellbeing of female adolescents.

Methods: This qualitative study sought reflections from secondary school staff on an intervention adopting the Health Promoting School (HPS) approach which aimed to enhance wellbeing through improving OM health literacy.

Results: Twenty female school staff from ten schools participated: three deans, 11 Health and Science teachers and six healthcare professionals. Five interviews and three focus groups were conducted, and 12 anonymously notated booklets of the program were returned. Reflective thematic analysis identified six themes: a need for OM health literacy; curricular challenges; teaching perspectives; school socio-emotional environment; community engagement; and resourcing needs.

Discussion: Alignment with a HPS-framework may resolve some barriers to future program implementation, such as curricular restrictions, interprofessional co-ordination and community engagement. Additional barriers, relating to menstrual disdain, knowledge gaps and an absence of professional development, may be addressed with training to ensure that OM health education is framed positively and addresses student wellbeing.

The public health significance of childhood and adolescence is immense because these years of biological, psychological and social transition are foundational to future adult health (Langford et al., 2015). For female adolescents specifically, the ovulatory menstrual (OM) cycle is imperative to growth (Brown et al., 2022) and has been recognized as a vital sign of good health (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2015).

However, there are OM health difficulties. Biologically, prevalence amongst 15–19-year-old Australian adolescents for premenstrual symptoms, period pain, mood disturbances and atypical bleeds have been identified as 96%, 93%, 73% and 41%, respectively, (Parker et al., 2010). Psychologically, studies have found poor OM health was associated with mental health difficulties (Bisaga et al., 2002; van Iersel et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017), including poor self-esteem (Drosdzol-Cop et al., 2017), body dissatisfaction (Ambresin et al., 2012), eating disorders (Ålgars et al., 2014; Drosdzol-Cop et al., 2017), and self-harm (Liu et al., 2018).

Acquiring OM health literacy is valuable. It can be defined as firstly: the discipline of applying OM cycle knowledge and skills to maintain personal health by reference to ovulation which drives menstruation and with due cognizance of life stage and/or stressors; and secondly: confident engagement and active co-operation with healthcare providers to restore good OM health as needed (Roux et al., 2023a, 2023b). OM health literacy is useful over the lifespan since OM cycles usually last for about 40 years (Vigil, 2019). As the OM cycle is a biopsychosocial phenomenon (Chrisler and Gorman, 2016), OM health literacy offers confidence to address menstrual shame and stigma (Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler, 2013). This may bode well for the liminal and healthy experiences of menarche, fertility, breastfeeding (Johnston-Robledo et al., 2007) and menopause.

However, studies have noted low levels of OM health literacy. For example, a narrative review of 61 studies highlights poor menstrual health literacy amongst adolescents in low-, middle-, and high-income countries (Holmes et al., 2021). A Turkish study concluded that 922 10–17-year-old girls had unsatisfactory knowledge of acceptable cycle parameters (Isguven et al., 2015). Similarly, of 442 15–18-year-old British girls, 27% were unsure about period duration and 30% about regularity (Randhawa et al., 2021). Finally, a qualitative study of 28 14–18-year-old Australian girls found a poor understanding of ovulation (Roux et al., 2023a, 2023b). Given the OM cycle’s longevity and health impact, a review of OM health education has been recommended (Isguven et al., 2015; Armour et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2021; Randhawa et al., 2021).

Schools are an appealing setting for OM health education and promotion for several reasons. Firstly, students spend much of their child and adolescent years at school (Burrows and Johnson, 2005; Li et al., 2020). In addition, health and education are intrinsically linked (Langford et al., 2017) and the organisational potential of schools lends itself to a comprehensive, sustained, efficient and cost-effective realisation of various public health initiatives (Langford et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020). Finally, schools can be agents of change (Turunen et al., 2017), by helping students develop skills to live well (Wyn, 2007), promoting wellbeing (Powell et al., 2018; Raniti et al., 2022), and influencing perceptions of menstruation (Burrows and Johnson, 2005). Furthermore, it is in schools’ interests to address the absenteeism and compromised academic performance which are associated with poor OM health (Armour et al., 2019).

For Australian schools, health literacy underpins the Australian Curriculum for Health and Physical Education [HPE; Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), 2023]. It uses the Health Outcome Model which sequentially organizes health literacy acquisition beginning with basic fundamentals (functional health literacy), proceeding to application and communication skills (interactive health literacy) and culminating in capabilities to discern broader health-related matters impacting self and others’ wellbeing (Nutbeam, 2000). These progressive levels of health literacy offer increasing autonomy and personal empowerment (Peralta et al., 2021). It has been argued that the Model is suited to adolescents because its accumulative progress from functional to critical health literacy aligns with the trajectory of their cognitive and social development (Sansom-Daly et al., 2016).

Over three decades ago, the concept of a “health-promoting school” (HPS) was advocated by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (World Health Organization, 1986). Briefly, the WHO’s HPS-framework is a holistic whole-school approach to promoting both health and educational outcomes and recognizing their intrinsic relationship (Langford et al., 2015). A HPS can be considered as a school which consistently strives to be a healthy setting for learning, teaching and working (World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2021). The WHO defines eight aspirational standards for HPS which are intended to function as a system. These are as follows:

- Standard 1: government policies and resources;

- Standard 2: school policies and resources;

- Standard 3. school governance and leadership;

- Standard 4: school and community partnerships;

- Standard 5: school curriculum;

- Standard 6: school social–emotional environment;

- Standard 7: school physical environment; and

- Standard 8: school health services.

The HPS-framework therefore captures the details of school systems and functions within a broader context. Ideally, health literacy is embedded throughout the HPS-framework (World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2021).

A range of interventions adopting the HPS-framework have been implemented. Langford’s global review of cluster-randomised controlled trials of 67 interventions documented two sexual health and two wellbeing interventions (Langford et al., 2015). A subsequent reflection noted that evidence was lacking for outcomes of mental or sexual health particularly among older adolescents and engagement with families and communities was weak (Langford et al., 2017). The absence of families is particularly regrettable given their influence on health-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviours (Peralta and Rowling, 2018).

Specifically for OM health education, a systematic literature review found the dominant approach of 16 interventions was deficit-oriented (Roux et al., 2021). Deficit models begin with identifying a problem (Gharabaghi and Anderson-Nathe, 2017), then emphasize difficulties and devise programs using problem-focused language (Joseph, 2008). By focusing on problems (such as period pain, mood disturbances or atypical bleeds), deficit-oriented programs may risk perpetuating the stigma of menstruation as a negative function (Roux et al., 2021). Furthermore, such programs lack the ability to promote and build on positive qualities (Noble and McGrath, 2008).

This study forms part of a broader formative research project to develop and trial an OM health literacy intervention program which is centered on the Whole Person; positively frames the OM cycle as an intrinsic sign of good health; maps health literacy outcomes to the HPE curriculum; and engages parents and external healthcare professionals (Roux et al., 2019). To the best of our knowledge, this program is the first to address OM health literacy within a HPS-framework. This article reports on the study’s aim to face validate this proposed intervention program by collecting qualitative data from a variety of secondary school staff.

Throughout this manuscript, terms such as females/males, girls/boys, and women/men are used in relation to sex (i.e., biological characteristics or reproductive organs), which may differ from gender identity.

Diverse methodological approaches were used to inform different stages of the OM health literacy program development (Roux et al., 2019), as is considered best practice (Duggleby and Williams, 2016). Firstly, a systematic literature review of school-based menstrual health education interventions informed the elements of program (Roux et al., 2021). A Delphi panel of 35 health and education professionals then provided the program’s content validation (Roux et al., 2022), which was simultanesouly mapped to the Western Australian HPE curricula for Years 8 to 10 (School Curriculum and Standards Authority, 2017). Face validation of the program was then conducted with 28 girls aged 14–18 years from 11 schools and five mothers (Roux et al., 2023a,b), who voted for the name “My Vital Cycles” (MVC).

The strengths-based approach of MVC begins with its emphasis of the Whole Person, whereby the physical, social, emotional, intellectual and spiritual or meaning-making aspects are addressed in equal measure. For example, the program is punctuated with guided conversations on rites of passage, future fertility and using the OM cycle for different aspects of life such as individualizing athletic training regimes (Oleka, 2019). The program’s holistic orientation then seeks to build competency (Noble and McGrath, 2008) in curricular-mapped OM health literacy skills.

Table 1 provides an outline of MVC lessons and delivery location. Nine lessons are offered, of which six are taught within the HPE curriculum, one is a school event involving parents, and two lessons are completed at home. OM health literacy is assessed using a validated questionnaire (Roux et al., 2023a,b).

The qualitative study design employed written reflections, interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) with school staff, including HPE and Science teachers, counsellors (such as psychologists and chaplains) and nurses. The study was conducted in 2020 and was guided by COREQ (Tong et al., 2007). Ethics approvals were provided by Curtin Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2018-0101) and Catholic Education Western Australia (RP2018/44).

The school principals of 39 Independent and Catholic schools in the Perth Western Australia metropolitan area were approached for permission to invite their teachers and healthcare professionals to participate in the study. Ten school principals consented for their school to be involved. Individual participants who expressed interest were given an Information Statement which described the study’s aims, participation requirements and data management. Interested participants signed their own Consent Form.

Prior to interviews and FGDs, a MVC booklet containing all lessons and assessments was given to each participant. Participants were given three weeks to write their anonymous reflections directly onto the booklet and to return it to the research team.

The school health literacy literature (Peralta and Rowling, 2018) informed the development of a semi-structured discussion guide (see Table 2). The discussion initially focused on the school’s current provision of menstrual health education and care. Participants’ opinions about the MVC program were then discussed. Open questions and prompts were used to guide participant-led discussions (Gill et al., 2008; Galletta and Cross, 2013).

Interviews of ≈45 min and FGDs of ≈50 min were conducted face-to-face at each school. They were facilitated by author FR, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Notations in the booklets were copied verbatim in table form against each lesson, and indicated school staff role and school type. Codes de-identified participants and are based on staff role, data collection points and school type (co-educational or girls-only).

Reflective thematic analysis provided flexibility for inductively-developed analysis, which enabled descriptive and interpretative accounts of the data (Braun and Clarke, 2022). A six-phase protocol was followed to analyze the transcripts thematically (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Data familiarisation occurred by rereading transcripts with the recordings to ensure accuracy. The cleaned transcripts were then imported into QSR International NVivo® Release 1.4(4), and coded line-by-line. Data units (words, expressions or sentences) were categorized into common codes which represented participants’ experiences and reflections (Willis et al., 2016). Constant comparison analysis strategies were used to analyze the transcripts which involved continually comparing and sorting the codes as more data were collected (Fram, 2013; Braun and Clarke, 2021). FR and JH undertook this initial analysis by reviewing each code. Hard-copy printouts of preliminary codes were shared with the research team, who questioned interpretations and conclusions. Coding was revised and connections amongst code categories were explored to find relationships that generate themes and subthemes (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Data dependability was maintained by reference to the cleaned transcripts. Bias was minimised by constant comparative data analysis (Bryman, 2016) and the continuous evaluation of FR’s and JH’s roles within the study (Biggerstaff and Thompson, 2008).

The 10 participating schools comprised five co-educational and five girls-only schools within the Independent and Catholic sectors. All were located in Perth metropolitan, Western Australia. Their Indices of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) ranged from 906 to 1,193 [Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), 2013]. The ICSEA is a value which reflects the levels of socio-educational advantage a given school’s student population enjoys relative to other schools. The benchmark average is 1,000, with values above or below indicating students’ level of socio-educational advantage. This value is influenced by students’ family background (such as parental occupation and education) and school-level factors (such as geographic location and proportion of Indigenous students). It does not measure academic performance or school wealth [Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), 2013].

There were 20 female participants of whom 14 were educators (specifically, three Deans, eight HPE teachers and three Science teachers) and six were healthcare professionals (specifically, two counsellors and four nurses). Five interviews and three FGDs with 15 participants were conducted. Twelve anonymously notated booklets returned, giving a return rate of 60%. No participants took up the offer to review their transcript. Table 3 summarizes the composition of participating school staff and lists the deidentification codes in the footnote to reflect individual school staff’s profession; the data collection point; and the school type.

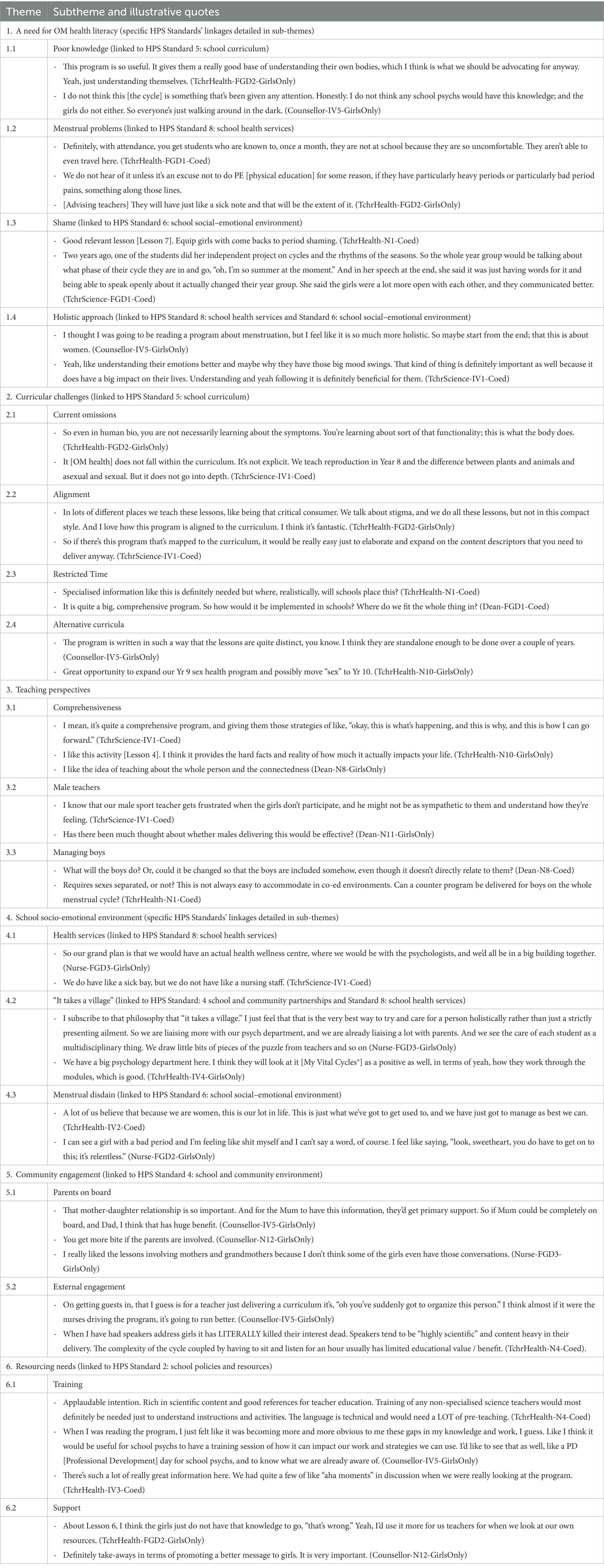

Six themes were identified: a need for OM health literacy; curricular challenges; teaching perspectives; holistic school environment; community engagement; and resourcing needs. These and 18 subthemes are presented with illustrative quotes in Table 4.

Table 4. Illustrative quotes linking the WHO’s Health Promoting School Standards to My Vital Cycles®.

The theme of a need for OM health literacy included the subthemes of poor knowledge (1.1), menstrual problems (1.2), shame (1.3), and holistic approach (1.4).

There was unanimous agreement that girls lacked functional OM health literacy which includes basic anatomy and cycle processes (subtheme 1.1), as relayed by one nurse:

We've had situations where we've even said, “this could be ovulation pain” and they look at you like they have never heard of ovulation before. If we ask, “do you know where your ovaries are; do you know how this works?”, it’s like we’re speaking a foreign language to them. Yeah. And we think, “oh my gosh, how could they not be learning this?” (Nurse-FGD3-GirlsOnly).

Teachers observed that girls’ menstrual problems (subtheme 1.2) impacted their schooling negatively, as one explained:

They're vomiting they're in so much pain and they're unable to focus. So it affects their attendance (TchrHealth-IV2-Coed).

One nurse reflected how having OM health literacy would enable girls to manage dysmenorrhea better:

And I guess if you know your cycle very well and you can chart it, then you know you're probably going to get your period tomorrow. And then you can start on your Ponstan®, Midol™, whatever, the day before or two days before. But [sighs], no. So we've got one next door at the moment. Well, she's taken Panadol® this morning, but of course that's worn off. And it’s gotten so bad now that she just wants to lay in bed, vomiting and curled up, doubled over in pain. And then that takes her out of class for probably the rest of the afternoon. (Nurse-FGD3-GirlsOnly).

Relatedly, girls’ shame was raised (subtheme 1.3) as follows,

You have to keep it secret, or you only talk with your best friends in a hushed little circle. So I think there's a fear of saying something's wrong (TchrHealth-IV2-Coed).

A typical reaction to how MVC managed shame was expressed as follows,

I really like the way that it's giving the girls just that openness to talk (TchrHealth-IV4-GirlsOnly).

The holistic approach of MVC was valued (subtheme 1.4), as notated,

I like the idea of the ‘whole’ person paradigm (TchrHealth-N10-GirlsOnly).

Others volunteered,

What I liked about it is its life skills (TchrHealth-IV4-GirlsOnly).

Another reflected on menarche’s liminality:

I actually think it's lovely to go back to where the first period was something significant and something to be, I don't know, celebrated isn't the right word, but certainly acknowledged that something has happened. (TchrHealth-FGD1-Coed)

Participants agreed that girls’ management of menstrual problems is hampered by their poor OM health literacy and shame. A holistic approach was considered a positive way to address this.

The theme of curricular challenges included the subthemes of current omissions (2.1), alignment (2.2), restricted time (2.3), and alternative curricula (2.4).

Teachers agreed that both within HPE and Science (subtheme 2.1),

There’s definitely ways to teach the menstrual cycle better (TchrHealth-FGD2-GirlsOnly).

As one teacher emphasized:

I do think that we do need to start teaching the girls not just puberty in Year 7 and leave it at that, because that doesn't cover everything. And there are a lot of misconceptions. How else do they get their health information? And part of the Health curriculum is looking at developing health literacy. And this is a big part for women's health literacy: to know how to speak about their periods and how to seek help when they need it. And what they're reading online: is that true or is that not true? How do they work that out? What's really important is if they have a good foundation. Then they can discern that. (TchrScience-IV1-Coed)

It was confirmed that teachers do not want to reinvent wheels (TchrScience-IV1-Coed). The fact that MVC covers so many areas of our curriculum (TchrHealth-IV4-GirlsOnly) was attractive (subtheme 2.2).

However, time restrictions prevented it being accommodated in the HPE curriculum (subtheme 2.3), because:

… of the bigger picture of everything that we've got to cover: sex, drugs, alcohol, fitness, yeah, it's really squished (TchrHealth-FGD2-GirlsOnly).

Quite simply, we cannot take anything else on, until it’s mandatory (TchrHealth-IV2-Coed).

Alternative ways to accommodate the program were suggested (subtheme 2.4). For example, within a wellbeing curriculum, or any of the following alternatives:

a separate series after schools as a community event (Dean-FGD1-Coed); co-curricular slash events (Nurse-FGD2-GirlsOnly); and as part of our girls’ camp (TchrHealth-IV3-Coed).

One HPE teacher also suggested that the program could also be split across different years within the same curriculum as follows:

There's a couple of things that we could even slide into our Year 8 program so that when they get to Year 9, it's not all new to them. Yeah, in Lesson 3 there's two options of activities. I thought, well, option one would fit nicely at Year 8, and then option two we'd do in the Year 9s. So they see both. Yeah, I like it. (TchrHealth-IV4-GirlsOnly)

Another alternative was dividing the program across the HPE and Science curricula, as one teacher explained,

So it's not like you have to teach it through Health, but you can … The Year 8 Science curriculum is when they do reproduction. The main focus is on body systems and how they work together. So that could definitely be moved later to when they're more mature and that wouldn't have a big impact. And then the Health curriculum is quite flexible. So that, I guess wouldn't really need to be changed too much. I think you could kind of pull it together. (TchrScience-IV1-Coed)

Although the value of teaching OM health literacy and MVC’s alignment with the HPE curriculum were recognised, restricted time was the reason for not accommodating it. Alternative ways of delivering the program included alternative curricula, or across multiple years of the HPE curriculum, or across both the HPE and Science curricula.

The theme of teaching perspectives included the subthemes of comprehensiveness (3.1), male teachers (3.2), and managing boys (3.3).

Participants understood that the program’s in-depth OM cycle science facilitated the instructions on charting (subtheme 3.1). One HPE teacher reflected that the discipline of charting:

… would give them [girls] so much insight into their own cycles (TchrHealth-FGD1-Coed).

Furthermore, a school nurse explained that this form of personalized learning is better remembered since:

… you never forget because it’s going on in you (Nurse-FGD2-GirlsOnly).

However, reservations were expressed regarding lessons being delivered by male teachers (subtheme 3.2), for example:

I just don't know how the girls would respond to a male staff member trying to teach them about something they know zero about. (TchrHealth-FGD2-GirlsOnly)

One school healthcare professional countered this as follows,

Yeah, I think if the guys were invested in this, it would be a lot different for the girls. Definitely, because it's like receiving information from a doctor. They wouldn't blink an eye. I mean, a lot of them would probably prefer seeing a female doctor. But it depends on how it's approached, yeah, and their demeanour. (Nurse-FGD2-GirlsOnly)

With regard to teaching boys and girls together (subtheme 3.3), it was generally accepted that:

… girls would feel uncomfortable with the boys around (TchrHealth-IV2-Coed).

Equally however, it was also agreed that it would:

… be great for boys to have a part of these lessons (Counsellor-N12-GirlsOnly).

As one teacher explained,

A couple of months ago, one of the Year 11 boys came to me and he said, “I've got a lot of questions about ovulation”, and I just loved that. Yes, I understand that girls would like to talk by themselves, and boys might not behave in an understanding way. But this is important because if boys don't understand ovulation, then it puts a lot of the contraception stuff onto the girls, which isn't fair. They need to understand what's happening for the girls if they're going to enter into a relationship with them. (TchrHealth-FGD2-Coed)

MVC was considered a comprehensive education of OM health, and was important for boys’ learning too. However, circumspection may be required for its delivery by male teachers.

The theme of the school socio-emotional environment included the subthemes of health services (4.1), “it takes a village” (4.2), and menstrual disdain (4.3).

There were differences between the healthcare facilities in schools (subtheme 4.1): ranging from a Wellness Centre with nurses (Counsellor-IV5-GirlsOnly), to a first aid room (Dean-FGD1-Coed). In schools with healthcare professionals, nurses were keen to be included in teaching, as follows:

We haven't historically been included [in the HPE curriculum]. We are always open to be included and have offered our support and services before. (Nurse-FGD3-GirlsOnly)

This contrasted with the account of another school, which suggested that their experience could be used similarly for delivering MVC (subtheme 4.2), as follows:

We traditionally have always been involved in teaching … We used to run the FRIENDS program with Year 7s. And we found that model works really well because we knew the whole cohort had those basic lessons. And then if they come and see us individually, we're like, “okay, do you remember what we did in the FRIENDS program?”, and then we build on from there. And it is so useful to have that model where everyone's got a basic knowledge, and then whoever needs something more, you're there to help them with that next step. And I can see this [MVC] working in a very similar way. (Counsellor-IV5-GirlsOnly)

Participants pointed out the value of distilling the efforts of all school staff into the program, for example:

If we worked the program together, it’s lots of different disciplines on board. Just many heads is better than one; yeah, helps with compliance, longevity, information, all that type of thing. (Nurse-FGD3-GirlsOnly)

Some participants expressed negative attitudes towards the cycle (subtheme 4.3). Statements included dismissal of the cycle’s intrinsic value and resentment as the following quotes illustrate:

… really, when you look at it, there’s not a lot to be positive about (TchrHealth-FGD1-Coed)

I hate it, and it’s unfair (Dean-FGD1-Coed).

One notation conveyed disgust,

OMG. Just looking at this makes my stomach churn – just YUCK! (TchrHealth-N4-Coed).

Schools offered health service facilities of varying types. One notable example was the involvement of healthcare professionals in teaching. However, in terms of a healthy social–emotional environment for OM cycle education and care, it was apparent that stigma persisted as menstrual disdain.

The theme of community engagement included two subthemes of parents on board (5.1) and external engagement (5.2).

There was explicit support for including parents in the program (subtheme 5.1), specifically because:

Mum wants to be on board (TchrHealth-IV2-Coed).

As one teacher explained:

I think it is good thing to have that parent event because this is sensitive. It's personal. Yeah, it’s sensitive; especially if you have conservative parents. (TchrHealth-IV4-GirlsOnly)

However, some participants offered a realistic perspective by observing,

… where we get parent support, that’s a bonus (TchrScience-IV1-Coed).

In another school with a similar experience, one HPE teacher added the following:

… there are some parents that don’t engage, or very minimal engagement (TchrHealth-FGD1-Coed).

With regard to community engagement with external healthcare professionals (subtheme 5.2), a number of participants perceived possible barriers for getting guests in (Counsellor-N12-GirlsOnly). One teacher explained the possible reasons:

I think getting the health professionals to come in might be a little bit challenging, especially for rural or remote schools like us. Yeah. We do have a GP [General Practitioner] down the road, which is handy. But availability? Yeah, that would require planning and coordinating. (TchrScience-IV1-Coed)

Overall, the participants maintained that including parents was important, albeit challenging. However, barriers to engaging external healthcare professionals were their availability and teachers’ efforts to organize their visits.

The final theme of resourcing needs included two subthemes of training (6.1) and support (6.2).

Most participants admitted that MVC presented them with new knowledge, including one Science teacher who notated,

I am picking up so much enlightening info that I will use in my Human Biol lessons (TchrScience-N9-GirlsOnly).

Consequently, it was recognised that training is needed (subtheme 6.1), as noted by a HPE teacher:

There would have to be substantial pre-training for those teachers over and above what they are expected to know, but also in terms of the actual delivery practice. (TchrHealth-N1-Coed)

In addition, support was recommended (subtheme 6.2) given the following reason:

… the cycle is arguably the most complex system for ADULTS to get their heads around – let alone girls (TchrHealth-N4-Coed).

As one HPE teacher further explained,

I think it's an area that even for some female teachers, they don't want to touch on … whereas, if this was a learning package that schools could buy, I think teachers would feel more comfortable that they've got backup. (TchrHealth-IV4-GirlsOnly)

Given the complexity of OM cycle science in addition to its stigma, participants recognised the need for training and ongoing support for MVC to be delivered in schools.

The results have revealed two important findings. Firstly, school staff understand girls’ OM health difficulties and the impact on their schooling. This has been similarly reported elsewhere. For example, in the United Kingdom (UK), 88% of teachers surveyed (n = 789) perceived that girls’ cycles affected school attendance, personal performance, confidence, mood and attitude (Brown et al., 2022). Equally in the United States of America (USA), 81% of teachers (n = 209) believed that menstrual embarrassment and poor OM health impacts learning because of difficulty with focusing, absences, and anxiety (Huseth-Zosel and Secor-Turner, 2022).

Secondly, participants confirmed that although puberty is taught, OM health literacy currently is not taught in their schools. Studies elsewhere have similarly suggested that health education needs to extend beyond puberty lessons (Koff and Rierdan, 1995; Li et al., 2020) to cover ovulation (Roux et al., 2021), OM health dysfunction and seeking medical care (Li et al., 2020).

Although MVC received remarkable support in principle, barriers to its implementation were highlighted, specifically menstrual disdain; school staff’s knowledge gaps; absence of professional development; curricular restrictions; interprofessional co-ordination; and community engagement.

Similar to a UK survey of teachers (n = 789), some participants framed their personal menstrual experiences variously with resentment or disgust, which may have influenced their delivery of care or education (Brown et al., 2022). This UK study further reported that less than 50 per cent of educators were comfortable teaching the cycle irrespective of their years of teaching experience (Brown et al., 2022). MVC intentionally adopts a strengths-based approach (Wilding and Griffey, 2015). Its lessons comprehensively present all of the OM cycle as an intrinsic sign of good health whilst pragmatically addressing common OM dysfunctions. Using the HPS-framework, its positive message can be taught through the HPE and Science curricula, and embedded in complementary healthcare practices, parent workshops and instructions for guest speakers. Since information alone is insufficient to address reviled or stigmatised subjects (Bulanda et al., 2014), these multiple support layers of the HPS-framework offer the possibility of collectively redressing menstrual disdain, including its shame and stigma (Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler, 2013).

Whilst a strengths-based approach may neutralize menstrual stigma, knowledge gaps are possibly another reason for educators’ discomfort in teaching the cycle (Brown et al., 2022). This study has shown that a correct understanding of the OM cycle is not guaranteed simply by membership of the population which commonly experiences it. The fertility literature confirms this, where only 12.7% of women (n = 282) motivated to get pregnant struggled to identify their most fertile time (Hampton et al., 2013). It has been suggested that current menstrual education is overly focused on science rather than symptom management or lived experience (Brown et al., 2022). In contrast, this study highlighted the need for better-quality science teaching. Participants recognized the innate complexity of the OM cycle, including their own lack of OM health literacy. It is only when this has been comprehensively addressed can school staff be reasonably expected to guide discussions on symptom management and lived experience.

Similar to this study, an absence of professional development was reported by a UK study in which 80% of teachers (n = 789) maintained that training would improve menstrual education (Brown et al., 2022). Equally, a USA study emphasised educating teachers on how to positively address menstrual experiences to foster a more supportive learning environment (Huseth-Zosel and Secor-Turner, 2022). In Australia, even teachers with experience in sexual health education described the need for regular training to enhance knowledge, update skills and master innovative teaching strategies (Burns and Hendriks, 2018). Furthermore, comprehensively designed training programs would appropriately equip male teachers with the knowledge, skills and confidence to deliver menstrual education positively. The HPS-framework explicitly draws attention to the need for school policies and resources which include the development of school staff (HPS Standard 2).

The challenge of limited curricular time highlighted in this study is similar to the findings of a UK study (Brown et al., 2022). The biopsychosocial nature of the OM cycle itself might hold the key to effectively addressing this challenge. Based on participants’ reflections, MVC lessons could be shared between biology in Science, and psychosocial wellbeing in the HPE curricula. The lessons could also be spread across years, and in extracurricular activities such as camps. Firstly, this may help students become convergent thinkers because they would process, merge and interchange their thought-processes across subjects (Peralta et al., 2017). Secondly, achieving a balance of comprehensively teaching a mixed gender class whilst providing opportunity for conversation and openness in a single gender class (Brown et al., 2022) becomes more realistic. Furthermore, tying functional (knowledge-based) OM health literacy to academic outcomes may hone the attention of otherwise disruptive male students. These novel approaches are best facilitated through the HPS-framework because Standards 3 and 5 capture the cross-discipline collaboration that would be needed amongst HPE and Science teachers.

Standards 3, 5 and 8 of the HPS-framework facilitate interprofessional co-ordination because a school’s healthcare team would work alongside the teachers in curriculum planning and assessment in delivering uniform and timely health interventions. This process also recognizes that a school’s healthcare team may wish to be involved in health education (Burns and Hendriks, 2018), which was endorsed by this study’s healthcare participants. School nurses particularly are uniquely placed as possible mentors because they are trained in therapeutic communication and health promotion (Moore et al., 2022). Although Australian school counsellors are less frequently involved in sexual health education (Mitchell et al., 2014), the holistic approach of MVC necessitates their inclusion.

Standards 3, 4 and 5 of the HPS-framework facilitate the development of a support network into the broader community. Not only do students value lessons from external health professionals (Isguven et al., 2015; Pound et al., 2016; Ezer et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020), such arrangements could offer continuity of care for sufferers of menstrual dysfunction. They can also build capacity within a school. For example, New Zealand schools are mandated to consult biannually with their community for health education, which includes collaboration within and across schools and with external services. It has been noted that this collaboration has shaped sexual health education delivery and professional development of teachers (Dixon et al., 2022). The HPS-framework drives active collaboration rather than “one-off” presentations by external providers as a substitute for teachers’ lack skills or confidence (Goldman, 2011; McCluskey et al., 2019). Addressing these becomes a priority because teachers’ knowledge of their students and the learning environment positions them well for providing sexual health education (Goldman, 2008).

Standards 3, 4, 5, and 8 of the HPS-framework explicitly recognize the importance and role of parents in caring for the health of students, their children. Particularly in OM health education, the literature recognizes the importance of the mother-daughter relationship (Koff and Rierdan, 1995; Isguven et al., 2015; Afsari et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020). Participants fully supported the three MVC lessons which involved parents. However, possible barriers to their involvement included parents’ lack of time and / or interest, as well as the additional efforts for school staff to arrange events.

To our knowledge, this is the first research in which menstrual health education is aligned with the HPS-framework. Furthermore, it includes measurable academic outcomes and intentional parent engagement, both of which have been lacking in previous studies (Langford et al., 2015; Thomas and Aggleton, 2016). Although the proposed program addressed most of the eight aspirational standards for HPS (World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2021), it did not address Standard 1 for government policies and resources, and Standard 7 for the school physical environment.

This study collected data through annotated booklets, interviews and FGDs. Multiple methods of data collection for the same phenomenon are considered to add validity (Cohen et al., 2017). However, the non-return of some booklets may have reduced the full richness of data possible. Reasons for non-return were not collected for this study.

Selection bias may be present as school staff who were interested in OM health more likely participated. Although invited to participate, there were also no male participants.

A strength of this study is the range of schools both below and above the average ICSEA value of 1,000, indicating that schools from across different socio-educational advantage or disadvantage were included in this study. However, the data was collected from Independent and Catholic school staff in metropolitan Western Australia and cannot be generalizable to public schools or other schools in regional, rural or remote areas.

A pilot study of MVC would likely indicate refinement possibilities. Additional studies include examination of current school resources in teaching cycle science; measuring the OM health literacy of school staff; and understanding the perspectives and experiences of male teachers. Finally, development and trial of school staff’s resourcing, training and support are recommended (Thomas and Aggleton, 2016; Peralta et al., 2022).

The HPS-framework layers multiple sources of positive support from a school’s governors, teachers, healthcare team, external speakers from the broader healthcare community and parent-body. However, there are barriers to implementing a comprehensive menstrual education program such as MVC. School-based barriers include curriculum restrictions; interprofessional co-ordination; and community engagement. Staff-based barriers to implementation include menstrual disdain, knowledge gaps and an absence of professional development. These barriers to implementing MVC could be resolved by adopting the HPS-framework because it facilities resourcing and developing school staff; cross-discipline collaboration, interprofessional co-ordination; development of a network into the broader community; and engagement with parents. When applying the HPS-framework, flexibility is recommended to shift from a “one size fits all” implementation approach to tailoring programs within different contexts whilst retaining its essential message and content (Darlington, 2016). Future research is required to resolve addressing barriers satisfactorily.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by Curtin Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2018-0101) and Catholic Education Western Australia (RP2018/44). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

FR, JH, HC, and SB contributed to the conception and design of the study. FR collected, analysed, and reported data. JH, SB, and HC reviewed data analyses. FR wrote the manuscript. JH, SB, and HC reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship under grant CHESSN8617438119.

Thanks are extended to all the school staff who participated, and to Kathryn Harrison of Curtin Medical School Western Australia for her artwork.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Afsari, A., Mirghafourvand, M., Valizadeh, S., Abbasnezhadeh, M., and Galshi, M. (2017). The effects of educating mothers and girls on the girls’ attitudes toward puberty health: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 29, 984–965. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0043

Ålgars, M., Huang, L., Von Holle, A. F., Peat, C. M., Thornton, L. M., Lichtenstein, P., et al. (2014). Binge eating and menstrual dysfunction. J. Psychosom. Res. 76, 19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.11.011

Ambresin, A. E., Belanger, R. E., Chamay, C., Berchtold, A., and Narring, F. (2012). Body dissatisfaction on top of depressive mood among adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 25, 19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.06.014

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2015). American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 651: menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet. Gynecol. 126, e143–e146. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001215

Armour, M., Hyman, M. S., Al-Dabbas, M., Parry, K., Ferfolja, T., Curry, C., et al. (2021). Menstrual health literacy and management strategies in young women in Australia: a national online survey of young women aged 13-25 years. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 34, 135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.11.007

Armour, M., Parry, K., Manohar, N., Holmes, K., Ferfolja, T., Curry, C., et al. (2019). The prevalence and academic impact of dysmenorrhea in 21,573 young women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Women's Health 28, 1161–1171. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7615

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) (2013). Guide to understanding 2013 index of community socio-educational advantage (ICSEA) values. Available at: https://www.myschool.edu.au/ [Accessed July 24, 2022].

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) (2023). Health and physical education (Version 8.4). Available at: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/teacher-resources/understand-this-learning-area/health-and-physical-education [Accessed April 19, 2023].

Biggerstaff, D., and Thompson, A. R. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): a qualitative methodology of choice in healthcare research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 5, 214–224. doi: 10.1080/14780880802314304

Bisaga, K., Petkova, E., Cheng, J., Davies, M., Feldman, J. F., and Whitaker, A. H. (2002). Menstrual functioning and psychopathology in a county-wide population of high school girls. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 41, 1197–1204. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00009

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 13, 201–216. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: a practical guide. Los Angeles, CA, USA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Brown, N., Williams, R., Bruinvels, G., Piasecki, J., and Forrest, L. J. (2022). Teachers' perceptions and experiences of menstrual cycle education and support in UK schools. Front. Glob. Womens Health 3:827365. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.827365

Bulanda, J. J., Bruhn, C., Byro-Johnson, T., and Zentmyer, M. (2014). Addressing mental health stigma among young adolescents: evaluation of a youth-led approach. Health Soc. Work 39, 73–80. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlu008

Burns, S., and Hendriks, J. (2018). Sexuality and relationship education training to primary and secondary school teachers: an evaluation of provision in Western Australia. Sex Educ. 18, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2018.1459535

Burrows, A., and Johnson, S. (2005). Girls' experiences of menarche and menstruation. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 23, 235–249. doi: 10.1080/02646830500165846

Chrisler, J., and Gorman, J. (2016). Menstruation. Encyclop. Ment. Health 3, 75–81. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00254-8

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th). London, England: Taylor & Francis.

Corbin, J. M., and Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.

Darlington, E. (2016). Understanding implementation of health promotion programmes: Conceptualization of the process, analysis of the role of determining factors involved in programme impact. [PhD dissertation]. Université Jean Monnet.

Dixon, R., Clelland, T., and Blair, M. (2022). It takes a village: partnerships in primary school relationships and sexuality education in Aotearoa. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 57, 367–384. doi: 10.1007/s40841-022-00260-5

Drosdzol-Cop, A., Bąk-Sosnowska, M., Sajdak, D., Białka, A., Kobiołka, A., Franik, G., et al. (2017). Assessment of the menstrual cycle, eating disorders and self-esteem of Polish adolescents. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 38, 30–36. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2016.1216959

Duggleby, W., and Williams, A. (2016). Methodological and epistemological considerations in utilizing qualitative inquiry to develop interventions. Qual. Health Res. 26, 147–153. doi: 10.1177/1049732315590403

Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Fisher, C. M., Heywood, W., and Lucke, J. (2019). Australian students’ experiences of sexuality education at school. Sex Educ. 19, 597–613. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2019.1566896

Fram, S. M. (2013). The constant comparative analysis method outside of grounded theory. Qual. Rep. 18, 1–25.

Galletta, A., and Cross, W. E. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Gharabaghi, K., and Anderson-Nathe, B. (2017). Strength-based research in a deficits-oriented context. Child Youth Serv. 38, 177–179. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2017.1361661

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., and Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 204, 291–295. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Goldman, J. (2008). Responding to parental objections to school sexuality education: a selection of 12 objections. Sex Educ. 8, 415–438. doi: 10.1080/14681810802433952

Goldman, J. (2011). External providers’ sexuality education teaching and pedagogies for primary school students in grade 1 to grade 7. Sex Educ. 11, 155–174. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2011.558423

Hampton, K. D., Mazza, D., and Newton, J. M. (2013). Fertility-awareness knowledge, attitudes, and practices of women seeking fertility assistance. J. Adv. Nurs. 69, 1076–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06095.x

Holmes, K., Curry, C., Sherry Ferfolja, T., Parry, K., Smith, C., Hyman, M., et al. (2021). Adolescent menstrual health literacy in low, middle and high-income countries: a narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052260

Huseth-Zosel, A. L., and Secor-Turner, M. (2022). Teacher perceptions of and experiences with student menstruation in the school setting. J. Sch. Health 92, 194–204. doi: 10.1111/josh.13120

Isguven, P., Yoruk, G., and Cizmecioglu, F. M. (2015). Educational needs of adolescents regarding normal puberty and menstrual patterns. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 7, 312–322. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.2144

Johnston-Robledo, I., and Chrisler, J. (2013). The menstrual mark: menstruation as social stigma. Sex Roles 68, 9–18. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-0052-z

Johnston-Robledo, I., Sheffield, K., Voigt, J., and Wilcox-Constantine, J. (2007). Reproductive shame: self-objectification and young women's attitudes toward their reproductive functioning. Women Health 46, 25–39. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n01_03

Joseph, S. (2008). “Positive psychology as a framework for practice,” in Frameworks for practice in educational psychology: a textbook for trainees and practitioners, eds. M. Thomas, B. Kelly, L. Woolfson, and J. Boyle London: Jessica Kingsley, 185–196.

Koff, E., and Rierdan, J. (1995). Preparing girls for menstruation: recommendations from adolescent girls. Adolescence 30:795.

Langford, R., Bonell, C., Jones, H., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S., Waters, E., et al. (2015). The World Health Organization's health promoting schools framework: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 15:130. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y

Langford, R., Bonell, C., Komro, K., Murphy, S., Magnus, D., Waters, E., et al. (2017). The health promoting schools framework: known unknowns and an agenda for future research. Health Educ. Behav. 44, 463–475. doi: 10.1177/1090198116673800

Li, A. D., Bellis, E. K., Girling, J. E., Jayasinghe, Y. L., Grover, S. R., Marino, J. L., et al. (2020). Unmet needs and experiences of adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea: a qualitative study. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 33, 278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.11.007

Liu, X., Liu, Z. Z., Fan, F., and Jia, C. X. (2018). Menarche and menstrual problems are associated with non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Arch. Women Ment. Health 21, 649–656. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0861-y

McCluskey, A., Kendall, G., and Burns, S. (2019). Students’, parents’ and teachers’ views about the resources required by school nurses in Perth, Western Australia. J. Res. Nurs. 24, 515–526. doi: 10.1177/1744987118807250

Mitchell, A., Patrick, K., Heywood, W., Blackman, P., and Pitts, M.. (2014). National Survey of Australian secondary students and sexual health. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre for Sex, Heath and Society, La Trobe University

Moore, S. S., Stephens, A., and Kelly, P. J. (2022). Nurse mentorship to support healthy growth of adolescent girls. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 60, 15–18. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20220324-03

Noble, T., and McGrath, H. (2008). The positive educational practices framework: a tool for facilitating the work of educational psychologists in promoting pupil wellbeing. Educ. Child Psychol. 25, 119–134. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2008.25.2.119

Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 15, 259–267. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

Oleka, C. T. (2019). Use of the menstrual cycle to enhance female sports performance and decrease sports-related injury. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 33, 110–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.10.002

Parker, M., Sneddon, A., and Arbon, P. (2010). The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG 117, 185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x

Peralta, L. R., Cinelli, R. L., and Marvell, C. L. (2021). Health literacy in school-based health programmes: a case study in one Australian school. Health Educ. J. 80, 648–659. doi: 10.1177/00178969211003600

Peralta, L. R., Cinelli, R. L., Marvell, C. L., and Nash, R. (2022). A teacher professional development programme to enhance students’ critical health literacy through school-based health and physical education programmes. Health Promot. Int. 37, 1–12. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daac168

Peralta, L. R., and Rowling, L. (2018). Implementation of school health literacy in Australia: a systematic review. Health Educ. J. 77, 363–376. doi: 10.1177/0017896917746431

Peralta, L., Rowling, L., Samdal, O., Hipkins, R., and Dudley, D. (2017). Conceptualising a new approach to adolescent health literacy. Health Educ. J. 76, 787–801. doi: 10.1177/0017896917714812

Pound, P., Langford, R., and Campbell, R. (2016). What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people's views and experiences. BMJ Open 6:e011329. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329

Powell, M. A., Graham, A., Fitzgerald, R., Thomas, N., and White, N. E. (2018). Wellbeing in schools: what do students tell us? Aust. Educ. Res. 45, 515–531. doi: 10.1007/s13384-018-0273-z

Randhawa, A. E., Tufte-Hewett, A. D., Weckesser, A. M., Jones, G. L., and Hewett, F. G. (2021). Secondary school girls’ experiences of menstruation and awareness of endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 34, 643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2021.01.021

Raniti, M., Rakesh, D., Patton, G. C., and Sawyer, S. M. (2022). The role of school connectedness in the prevention of youth depression and anxiety: a systematic review with youth consultation. BMC Public Health 22, 2152–2124. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14364-6

Roux, F., Burns, S., Chih, H. J., and Hendriks, J. (2019). Developing and trialling a school-based ovulatory-menstrual health literacy programme for adolescent girls: a quasi-experimental mixed-method protocol. BMJ Open 9:e023582. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023582

Roux, F., Burns, S., Chih, H., and Hendriks, J. (2022). The use of a two-phase online Delphi panel methodology to inform the concurrent development of a school-based ovulatory menstrual health literacy intervention and questionnaire. Front. Glob. Women Health 3:826805. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.826805

Roux, F., Burns, S., Hendriks, J., and Chih, H. J. (2021). Progressing toward adolescents’ ovulatory-menstrual health literacy: a systematic literature review of school-based interventions. Women Reprod. Health 8, 92–114. doi: 10.1080/23293691.2021.1901517

Roux, F., Burns, S., Hendriks, J., and Chih, H. (2023b). “What’s going on in my body?”: gaps in menstrual health education and face validation of my vital cycles, an ovulatory menstrual health literacy program. Aust. Educ. Res. doi: 10.1007/s13384-023-00632-w

Roux, F., Chih, H., Hendriks, J., and Burns, S. (2023a). Validation of an ovulatory menstrual health literacy questionnaire. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 63, 588–593. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13680

Sansom-Daly, U., Lin, M., Robertson, E., Wakefield, C. E., McGill, B., Girgis, A., et al. (2016). Health literacy in adolescents and young adults: an updated review. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 5, 106–118. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0059

School Curriculum and Standards Authority (2017). Government of Western Australia. Health and Physical Education Curriculum – Pre-Primary to Year 10. Available at: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/health-and-physical-education [Accessed April 12, 2018].

Thomas, F., and Aggleton, P. (2016). A confluence of evidence what lies behind a “whole school” approach to health education in schools? Health Educ. 116, 154–176. doi: 10.1108/HE-10-2014-0091

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Turunen, H., Sormunen, M., Jourdan, D., Von Seelen, J., and Buijs, G. (2017). Health promoting schools: a complex approach and a major means to health improvement. Health Promot. Int. 32, 177–184. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dax0001

van Iersel, K. C., Kiesner, J., Pastore, M., and Scholte, R. H. J. (2016). The impact of menstrual cycle-related physical symptoms on daily activities and psychological wellness among adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. 49, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.007

Vigil, P. (2019). Ovulation a sign of health: Understanding reproductive health in a new way. New York, USA: Reproductive Health Research Institute.

Wilding, L., and Griffey, S. (2015). The strength-based approach to educational psychology practice: a critique from social constructionist and systemic perspectives. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 31, 43–55. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2014.981631

Willis, D. G., Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Knafl, K., and Cohen, M. Z. (2016). Distinguishing Features and Similarities Between Descriptive Phenomenological and Qualitative Description Research. West J. Nurs. Res. 38, 1185–1204. doi: 10.1177/0193945916645499

World Health Organization (1986). “Ottawa charter for health promotion” in The move towards a new public health, an international conference on health promotion (Geneva: WHO)

World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school. Global standards and indicators for health-promoting schools and systems. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025059 [Accessed April 19, 2023].

Wyn, J. (2007). Learning to “become somebody well”: challenges for educational policy. Aust. Educ. Res. 34, 35–52. doi: 10.1007/BF03216864

Keywords: ovulation, menstruation, wellbeing, health literacy, adolescence, Health Promoting School, mental health, strengths-based teaching

Citation: Roux F, Hendriks J, Burns S and Chih H (2023) An ovulatory menstrual health literacy program within a Health Promoting School framework: reflections from school staff. Front. Educ. 8:1239619. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1239619

Received: 13 June 2023; Accepted: 21 September 2023;

Published: 18 October 2023.

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Lawrence StLeger, Deakin University, AustraliaCopyright © 2023 Roux, Hendriks, Burns and Chih. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felicity Roux, RmVsaWNpdHkuUm91eEBjdXJ0aW4uZWR1LmF1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.