- 1Institute of School and Profession, University of Teacher Education St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

- 2Department of Educational Science and School of Education, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

- 3Institute of Educational Science, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Emotions are an important factor influencing teaching behavior and teaching quality. Previous studies have primarily focused on teachers’ emotions in the classroom in general, rather than focusing on a specific aspect of teaching such as homework practice. Since emotions vary between situations, it can be assumed that teachers’ emotions also vary between the activities that teachers perform. In this study, we therefore focus on one specific teacher activity in our study, namely homework practice. We explore teachers’ emotions in homework practice and their antecedents. Methodologically, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 23 Swiss secondary school teachers teaching German and analysed using structuring qualitative content analysis. The results show that teachers experience a variety of positive and negative emotions related to homework practice, with positive emotions predominating. According to the teachers’ reflections, the antecedents of their emotions could be attributed to the context (e.g., conditions at home), teacher behavior and (inner) demands (e.g., perceived workload) and student behavior (e.g., learning progress). Implications for teacher education and training are discussed.

1. Introduction

Schutz and Lanehart (2002) emphasized that “emotions are intimately involved in virtually every aspect of the teaching and learning process and, therefore, an understanding of the nature of emotions within the school context is essential” (p. 67). Since then, research on emotions in education has steadily increased and includes empirical studies on the emotions of students, teachers, as well as parents (e.g., Dettmers et al., 2011; DiStefano et al., 2020; Burić and Frenzel, 2021). The results regarding the teacher uniformly show that they experience a variety of emotions while teaching (Hargreaves, 1998; Sutton and Wheatley, 2003; Mevarech and Maskit, 2015), which have been identified as significant factors that influence teaching behavior, and consequently, teaching quality and student outcomes (Frenzel et al., 2009b; Hagenauer and Hascher, 2018; Frenzel et al., 2021). Moreover, recognizing, understanding, and expressing these emotions are crucial for teachers’ well-being (Hagenauer and Hascher, 2018; Dreer, 2021; Hascher and Waber, 2021).

Previous studies have focused predominantly on teachers’ emotions during teaching as broadly defined (e.g., Chen, 2019), rather than on a specific facet of teaching practice. Such an approach is valuable because it generates insights into how teaching in general is experienced emotionally by teachers and how these emotions in turn affect students (Frenzel et al., 2021). However, research has shown that students’ emotions vary depending on the subject (Goetz et al., 2006, 2010) or activity they are engaged in (e.g., emotions in learning, emotions during exams, emotions during homework etc.; Pekrun et al., 2002; Goetz et al., 2012). The same can be assumed for teachers. The effect of context and situation on emotions is increasingly coming to the fore of academic research (for example, Pekrun and Marsh, 2022). In our study, we therefore zoom even more precisely into the different activities or tasks a teacher is required to perform to examine their emotional experience more closely in connection with a very specific activity: namely, homework practice. In this study, homework practice means teachers’ various actions related to homework. It includes planning, assigning, but also checking, giving feedback or integrating homework into the lesson.

We have chosen to focus on the activity of homework practice as homework in schools has been a topic of controversial discussion for decades, especially with regard to its effectiveness and quality (Baş et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2017). Homework practice has now been brought even more into focus by the COVID-19 pandemic, as homework also promotes core student skills, such as self-regulated learning (Pelikan et al., 2021). It can be assumed that teachers who experience homework practice positively and implement it with motivation also achieve a higher quality of the homework. Previous research clearly points to the association between teachers’ emotions and teaching quality (e.g., Becker et al., 2015). Even though emotions are considered relevant as part of teachers’ professional competence (Frenzel et al., 2021), there is currently a lack of empirical evidence on which emotions teachers experience in homework practice and what triggers them. This is the focus of the present study. Based on an exploratory approach, arising from the limited empirical findings on this topic to date, we examine which emotions teachers experience in relation to homework practice and their antecedents. We adopt Cooper’s (1989) definition of homework as a task that a teacher gives to students to complete out of school. However, the homework process we are interested in as an emotion-triggering source of teachers’ emotions should be thought of more broadly and ranges from planning homework to assigning and correcting it and giving feedback. Therefore, it is not only about activities that the teacher does for themselves (e.g., planning homework), but also about the teacher–student interactions that occur in the course of the homework process, for example, when teachers give feedback to students or discuss homework together in class.

2. Teachers’ emotions

2.1. Definition of emotions and teachers’ emotions

Emotions are multidimensional constructs that consist of (1) affective, (2) physiological, (3) cognitive, (4) expressive, and (5) motivational components (Kleinginna and Kleinginna, 1981; Scherer, 2005; Shuman and Scherer, 2014). Emotions have what Frenzel et al. (2015) call a “felt core”— the tangible experience of feeling (p. 202). When people experience emotions, the body often reacts as well. For example, the experience of fear can result in an increased heart rate or a change in breathing rate or pattern (Frenzel et al., 2015, p. 202). Emotional experiences also impact thoughts, such as when fear leads to thoughts about consequences. Emotions can be perceived by the outside world through the expressive component. For example, fear can be expressed verbally or non-verbally, such as through a worried face. Finally, the motivational component ensures that appropriate action is taken. Fear often leads to avoidance behavior.

According to Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2012, p. 261; see also Pekrun et al., 2023), emotions can be described and differentiated according to their valence and activation. In terms of valence, a distinction can be made between positive (e.g., joy) and negative (e.g., anger). Valence in this context is related to the subjective experience of the teacher. Positive emotions are classified as those that are experienced as pleasant by the teacher, whereas negative emotions are defined as those experienced as unpleasant. Both negative and positive emotions can be functional or dysfunctional (for a critical discussion see An et al., 2017). In addition, there are physiologically activating or deactivating states. Excitement is activating, whereas relaxation is usually deactivating. These two aspects are crucial for understanding the actions that arise from emotions, as in the case of teachers who experience emotions in the classroom and act accordingly.

Teachers’ emotions have increasingly become objects of study in recent years. Frenzel (2014) proposed a reciprocal model of the causes and effects of teachers’ emotions when teaching in class. It illustrates how teachers’ emotions are triggered and influenced by and affect the teaching process. The basic assumptions of the model are based on an appraisal-theoretical understanding of emotions (Ellsworth and Scherer, 2003). Appraisal theory explains why the same external experience may not lead to the same emotional responses in all individuals; it is not the experience itself that evokes the emotion, but the subjective appraisal made by the individual (Sutton and Wheatley, 2003). For teachers, this appraisal is based on four aspects of teacher goals: (1) cognitive, (2) motivational, (3) social, and (4) relational (Frenzel et al., 2009b; Frenzel, 2014). Based on their perceptions of learners’ behavior on these four dimensions, teachers assess whether they have achieved or will achieve these goals. The outcome of this assessment process determines the teachers’ emotional response. For example, if a teacher perceives students’ engagement as high, it is likely that the teacher will experience positive emotions (e.g., enjoyment) as the students’ behavior is interpreted as goal conducive. These emotions then influence the teacher’s classroom behavior (i.e., cognitive activation, classroom management, social support). For example, teachers who experience positive emotions can build trusting relationships with their students. These instructional behavior factors affect students’ achievement, motivation, behavior in class, and relationship with the teacher. Thus, student and teacher behavior in the classroom is both the cause and effect of the teacher’s emotional experiences. This reciprocal relationship between teacher and student emotions has been empirically confirmed in a variety of studies (Frenzel et al., 2009a,b; Becker et al., 2014; Keller and Lazarides, 2021). It is expected that students’ homework behavior on the different dimensions is related to teachers’ homework-related emotions as well. It seems plausible, for example, that students who are committed to doing their homework trigger positive emotions in teachers because teachers then feel confirmed in their effectiveness and consider their goals to have been achieved. However, there are no specific empirical findings for homework practice so far.

2.2. Antecedents of teachers’ emotions—empirical findings

Teachers experience emotions for a variety of reasons related to achieving or not achieving their goals (Sutton and Wheatley, 2003; Sutton, 2007; Frenzel, 2014). They experience joy in the classroom when students are motivated (Becker et al., 2015; Burić and Frenzel, 2021), engaged (Prawatt et al., 1983; Epstein and van Voorhis, 2012; Hagenauer et al., 2015; Chang, 2020), interested (Frenzel et al., 2008), disciplined (Hagenauer et al., 2015; Frenzel et al., 2020) or simply happy (Chang, 2020; Keller and Lazarides, 2021). According to Frenzel et al. (2008) and Keller and Lazarides (2021), joy is the emotion most commonly reported by teachers. When students are successful or interactive, teachers experience positive emotions (Sutton, 2005; Wu and Chen, 2018; Chang, 2020) regardless of the students’ abilities (Prawatt et al., 1983). In addition, they feel pride when a student with low abilities suddenly begins to try very hard (Prawatt et al., 1983).

However, student engagement and discipline are also significant predictors of negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and frustration (Prawatt et al., 1983; Georgiou et al., 2002; Sutton and Wheatley, 2003; Sutton, 2005; Becker et al., 2014; Hagenauer et al., 2015; Frenzel et al., 2020). Anger is mainly evoked when students misbehave, do not participate, or are inattentive or unmotivated (Sutton, 2007; Hagenauer et al., 2015). It also arises when teachers attribute students’ academic failures to inadequate effort (Reyna and Weiner, 2001). The level of discipline has a significantly negative correlation with fear (Frenzel et al., 2008). Surprise occurs when low-ability students who make little effort nevertheless succeed or high-ability students who exert a lot of effort fail (Prawatt et al., 1983).

The relationships between students and teachers are also associated with emotions. When teachers feel connected to their students, they experience joy. If these relationships cannot be established, anger and anxiety are more likely to arise (Hagenauer et al., 2015). In addition, social relations outside the classroom—such as those with colleagues or parents—can also lead to emotional responses (Sutton and Wheatley, 2003; Sutton, 2005; Wu and Chen, 2018). Teachers feel pleasant emotions when they succeed in working with their colleagues, receive support from school leaders, or experience recognition from parents (Chen, 2019). In contrast, unpleasant emotions can result if they experience competition with their colleagues, receive little support from the administration, or interact with uncooperative parents (Sutton, 2005; Chen, 2019).

In conclusion, the main sources which trigger teachers’ emotions proposed in the model on teachers’ emotions (Frenzel, 2014) have been confirmed empirically by various studies in different countries. However, it remains an open question whether these particular sources are also at the core of teachers’ emotions related to homework.

3. Homework

Homework has a long tradition worldwide and is a relevant practice in many schools. As already outlined in the introduction, it is defined as assignments given by a teacher for students to complete outside of school (Cooper, 1989).

To date, much of the research on homework has focused on its didactic–methodological function (e.g., Fernández-Alonso et al., 2019). For example, researchers have investigated whether the additional learning time gained through homework impacts student performance (e.g., Rosário et al., 2018). In addition, research has analysed whether homework supports self-regulated learning by helping students acquire learning strategies (Trautwein and Lüdtke, 2008). Another aspect that has been considered is whether homework functions as an equalizer or reinforces inequality because students have different degrees of support at home (Dettmers et al., 2019). Additionally, researchers have investigated the influence of homework on the development of students’ interest (Trautwein et al., 2001).

Although the aforementioned research has produced different findings, it is the consensus that doing homework alone does not necessarily provide benefits, but that the quality of homework is decisive in determining whether students benefit from it (Trautwein et al., 2001, 2002; Flunger et al., 2015; Rodríguez et al., 2019). Previous studies have shown that quality homework can positively influence the learner’s behavior and achievement (Trautwein et al., 2002, 2006; Trautwein and Lüdtke, 2007, 2009; Dettmers et al., 2010; Rosário et al., 2018). Moreover, a student’s motivation to complete homework is positively related to its perceived quality (Trautwein et al., 2006; Trautwein and Lüdtke, 2007; Rosário et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2021; Xu, 2022). For example, Rosário et al. (2018) found that when students perceive their homework to be high quality, they try harder, complete homework more often, perform better on assignments, and get higher grades in mathematics. However, the topic of homework is still controversial and opinions about the sense or even meaninglessness of homework are diverse (Cooper et al., 2006; Fan et al., 2017). Due to these controversies, the topic can also be considered “emotional,” be it that homework often leads to conflicts between students and their parents (Forsberg, 2007; Dumont et al., 2012) or that homework can also trigger emotions in the teacher–student interaction, for example, when students do not complete their homework (see Hagenauer et al., 2015 for teacher-student interaction).

Studies on students’ emotions during homework show that they are influenced by perceived homework quality and by parental homework support (Trautwein et al., 2009a,b; Dettmers et al., 2011). For example, negative emotions arise when perceived homework quality is low or parental homework help is perceived as controlling and can have a negative impact on homework effort and performance (Else-Quest et al., 2008; Trautwein et al., 2009a,b; Dettmers et al., 2011). Trautwein et al. (2009b) also found that negative emotions are negatively related to homework effort and French performance. However, they were also able to show that performance can predict subsequent negative emotions in homework. Regarding the parents, it was found that the emotions of the parents (e.g., about a subject) influence their homework support, but also have an influence on the emotions of the students (Moè and Katz, 2018; DiStefano et al., 2020). Hence, while there are some studies on students’ emotions (Knollmann and Wild, 2007; Trautwein et al., 2009a; Dettmers et al., 2011) and parents’ emotions (Moè and Katz, 2018; DiStefano et al., 2020), research on teachers’ emotions pertaining to homework practice is lacking.

4. The present study

Many studies have investigated the emotions teachers experience while teaching (Sutton and Wheatley, 2003; Frenzel, 2014; Fried et al., 2015; Frenzel et al., 2021). However, there has been little research to date that focuses on specific activities of teaching. The present study focuses on the homework process. Based on Frenzel’s (2014) model, it can be assumed that the quality of homework is influenced by the teachers’ emotions. For example, positive emotions, such as joy triggered by students who are highly engaged in homework, may cause teachers to put in the effort to assign differentiated homework. This is likely to further enhance the students’ motivation and engagement. Thus, perceived student engagement and motivation may function as a significant cause of a teacher’s emotions related to homework. So far, however, there is no empirical evidence on the antecedents of teachers’ emotions and experienced teachers’ emotions themselves in the homework process.

To this end, in the present study we explored the following main research questions:

1. Which emotions do teachers experience related to German language homework (the language of instruction and the students’ native language), and (2) what are their antecedents?

This zooming in on a specific activity of teachers is timely, as the high context specificity of emotions and consequently the variations of emotions between contexts and situations are increasingly seen as being relevant for empirical research in the field. While there is already a great deal of empirical evidence on teachers’ emotions while teaching in general and their relations to students (e.g., Frenzel et al., 2021), our study extends previous research efforts by taking a closer look at a specific activity of teachers – homework practice and its emotional potential for teachers—and thereby also taking the context specificity of teachers’ emotions into account.

5. Method

5.1. Participants

A total of 23 secondary school teachers from the canton of Bern in Switzerland participated in this study. The conditions for participation were that they had been in the teaching profession for at least 3 years and taught German (which is the language of instruction and a primary subject in the area). The subject German was chosen as it is one of the main subjects in Swiss secondary schools. Homework and its control can be very time-consuming for teachers, as essays have to be corrected in addition to other forms of assignments. In addition, it was important for us that the teachers already had sufficient professional experience so that they could report from their broad experience.

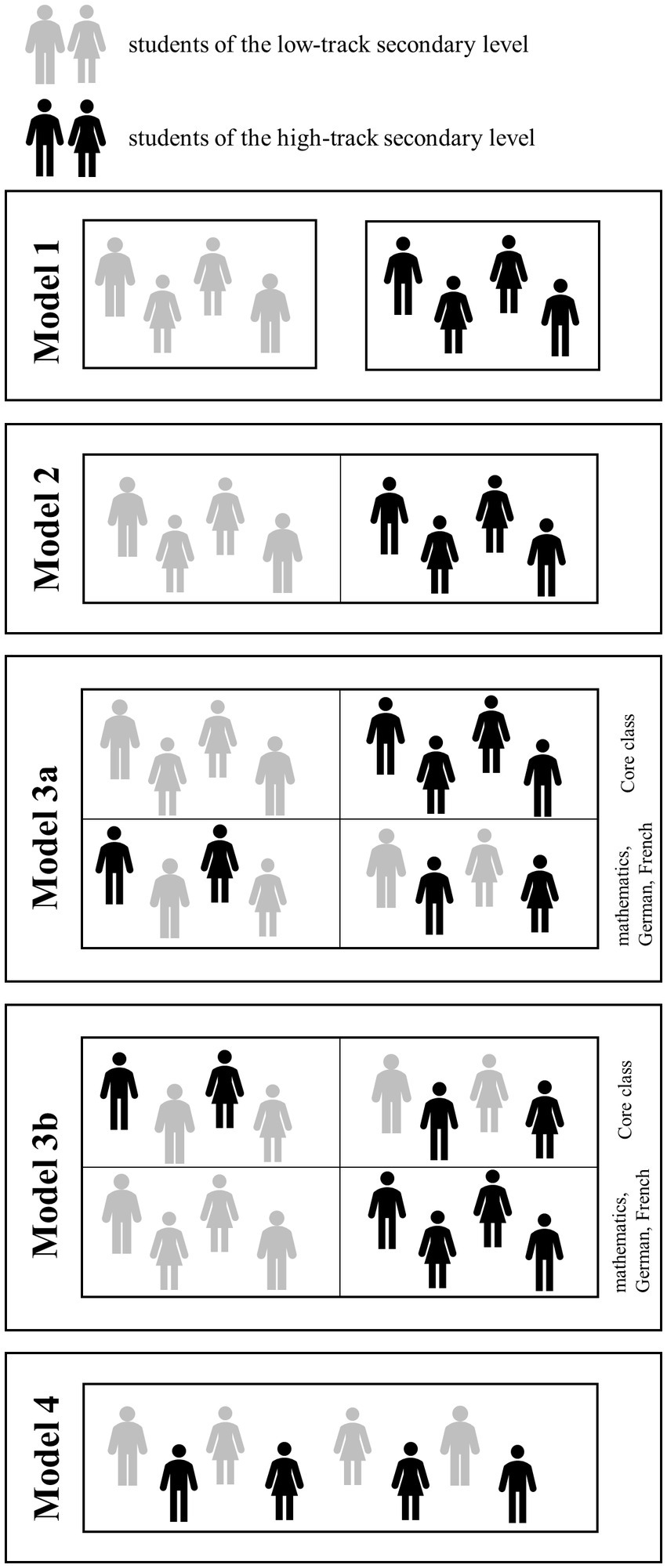

We first contacted all secondary schools in the canton of Bern to recruit teachers who were willing to participate in interviews. There are five different school models in Bern, which differ in terms of permeability (see Figure 1). In Model 1, the students of the high-track secondary level (Sekundarschule) and the low-track secondary level (Realschule) are taught separately in different school buildings. In Model 2, the two tracks are taught separately but in the same school building (i.e., there are separate high-track and low-track classes in the same building). In Model 3a, students in the low- and high-track levels are taught separately in most subjects; however, in the main subjects (mathematics, German, French), they are grouped according to their ability levels. In Model 3b, core classes are mixed, while the three main subjects are taught in ability-level groups. In Model 4, all subjects are taught in mixed levels and classes are only differentiated internally.

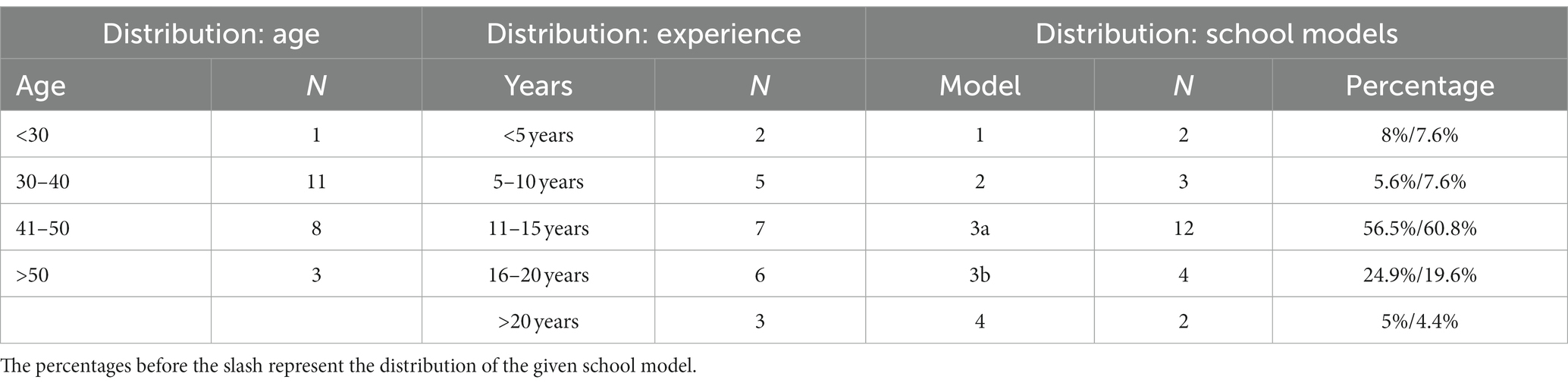

Of the teachers interviewed, two teachers were from Model 1, three teachers were from Model 2, 12 teachers were from Model 3a, four teachers were from Model 3b, and two teachers were from Model 4. This distribution accurately reflects the distribution of teachers among the different models in the canton of Bern. Model 3a is the most frequently implemented (see Table 1).

Of the 23 teachers interviewed, 12 were female (52.2%) and 11 were male (47.8%). One teacher was under 30 years old, 11 were between 30 and 40 years old, eight were between 41 and 50 years old and three were over 50 years old. The teachers also differed in terms of professional experience. Two had been in the teaching profession for less than 5 years, five for 5–10 years, seven for 11–15 years, six for 16–20 years and three for over 20 years (see Table 1).

5.2. Interviews and procedure

As teachers’ emotions related to homework practices are relatively unexplored, a qualitative–explorative approach was chosen to answer the proposed research questions. In addition, a short questionnaire was used to collect demographic information and the teachers’ positive and negative affect related to homework practice.

5.2.1. Interviews

We conducted semi-structured interviews based on an interview guide that lasted between 28 and 69 min. The interview guide had been previously piloted with two teachers. These interviews showed that the questions were easy to understand but that the interviewees found it difficult to identify emotions on their own.

Consent to use the data was obtained from the participants. In addition, they were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time and were assured that their personal information and data would be kept confidential. Interviews were conducted by the principal investigator in person or via Zoom (because of the COVID-19 pandemic). An informal conversational style was used to encourage respondents to speak openly about their experiences. They were also told that their experiences were important and that, therefore, there were no right or wrong answers; this was intended to ensure that they would proffer information as freely and openly as possible.

During the interviews, the teachers were asked to report on situations related to the homework process that had evoked emotions in them. They were asked to name the emotion and describe the situation that caused it (Main interview question: In which situations related to homework do you experience positive feelings? What kind of feeling? Can you tell me more about it? In which situations do you experience negative feelings? What kind of feeling? Can you tell me more about it?). Based on the test interviews, during a second step, the teachers were presented with a list of specific emotions (which were also later addressed in the short questionnaire) and asked to read them. If they had experienced the emotion and had not yet mentioned it, they were asked to explain a situation that had triggered this emotion (Main interview question: You have now already reported on various emotions in the homework process. I will show you a selection of emotions now. Read through the emotions briefly. Perhaps you will notice that you have experienced one or two of them in connection with your homework practice. I would ask you to tell me a bit more about it).

5.2.2. Teachers’ positive and negative affect

After the interviews, the teachers filled out a short questionnaire which consisted of demographic information and the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS, Breyer and Bluemke, 2016; German version). The PANAS scales were applied to provide a preliminary quantifying description of the teachers’ emotions related to their homework practice in addition to the thick and contextualized descriptions resulting from the interviews. The teachers had to answer the following question in terms of different emotions (e.g., active): “When you think about your previous homework practice, how do you feel about it in general?” The PANAS consists of ten positive and ten negative emotional states. Additional emotions that were considered relevant to homework were added: satisfied, disappointed, relaxed, frustrated, relieved, confident, hopeless, stressed, empathic, grateful, hopeful, bored, sad, pity, embarrassed, guilty conscience, disgusted, admiring, and envious (see Supplementary Table S1). The teachers assessed the intensity with which they felt each emotion using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

5.3. Data analysis

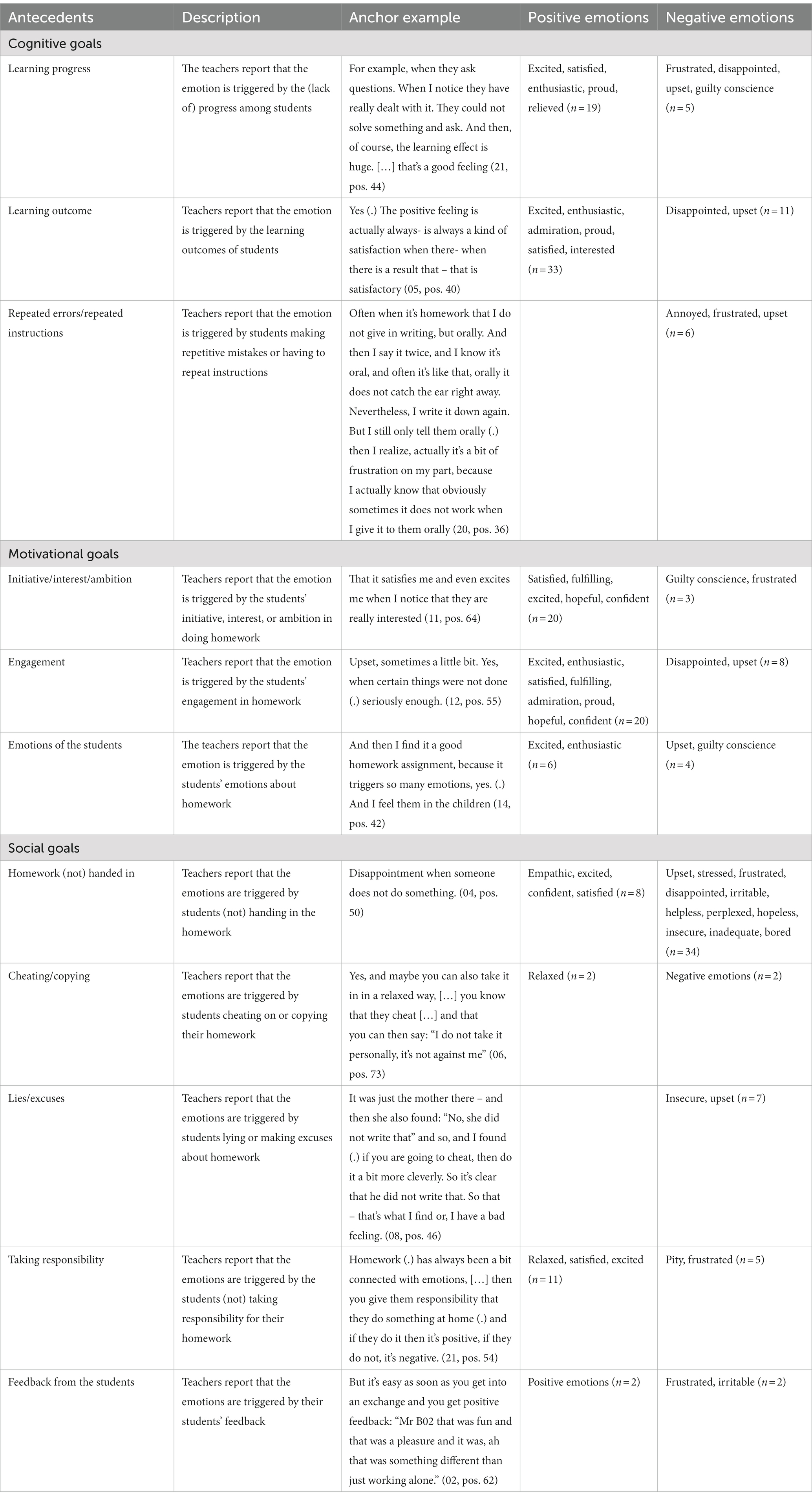

The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Fuss and Karbach (2019) and Kuckartz (2010) identified obligatory and pre-defined transcription rules. All transcripts conformed to these rules. Personal information provided by the participants was anonymised in the transcripts. The interviews were analysed utilizing the software MAXQDA based on the qualitative content analysis structure defined by Mayring (2017). A coding frame was developed consisting of several main categories and subcategories that structured the material. First, the interview material was coded based on Frenzel’s (2014) teachers’ emotions model. They classified the students’ behavior on cognitive, motivational, and social levels as relevant antecedents of the teachers’ emotions. All other key categories and sub-categories pertaining to the triggers of the teachers’ emotions that were part of the coding frame emerged inductively from the material. In terms of specific emotions, the emotional states from the PANAS scales were used as deductive categories. Other emotions, such as feeling insecure, emerged from the interviews, so further inductive categories were formed during the coding process. These categories and the overall coding frame were discussed several times with a second researcher. The full coding frame is available from the researchers on request. Extensive extracts from the coding frame are depicted in the results section in Tables 2–4.

For the final coding frame, each category was described and assigned a representative anchor example. In relation to the research questions, the coding scheme included 21 categories of positive emotions and 27 categories of negative emotions. A total of 116 codes in the positive emotion categories and 133 codes in the negative emotion categories were developed. The coding scheme also included 25 antecedents, 20 of which were divided into positive and negative. The exceptions were categories that were considered to be positive or negative per se (e.g., lies/excuses). There were 373 codes in the antecedent categories.

To ensure intercoder reliability, a second independent researcher who was not involved in the research project but who has expertise in the field coded a randomly selected interview using the final coding scheme. The codes were discussed with the second researcher. After a consensus was reached, the independent researcher coded four more randomly selected interviews. These were used to calculate intercoder reliability via the corrected Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, as suggested by Brennan and Prediger (1981). The intercoder reliability as a measure of the coding consistency was good, suggesting consistency in the coding process (κ = 0.78; Landis and Koch, 1977).

6. Results

In the following sections, the results of the study are reported. First, the emotions reported in the short questionnaire are presented, which is followed by the antecedents and associated emotions reported in the interviews. We will describe the dimensions/categories in detail and complement this description with frequencies (i.e., How many teachers mentioned each category). This procedure—the combination of detailed description and the indication of frequencies—is a common strategy for presenting results when using qualitative content analysis (Schreier, 2012).

6.1. Which emotions do teachers experience in relation to their homework practice?

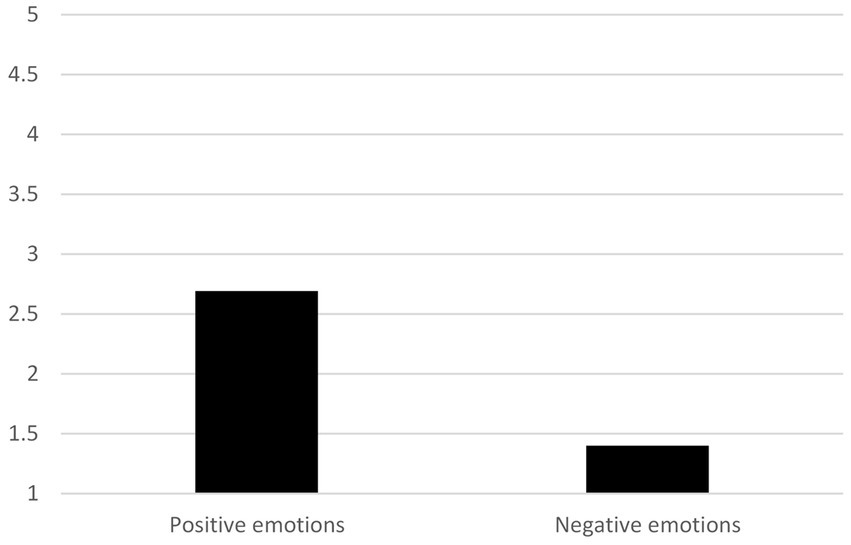

Findings from the PANAS scales revealed that the teachers experienced a variety of positive and negative emotions related to homework. Positive emotions dominated over negative emotions (Mpositive emotions = 2.69; Mnegative emotions = 1.40) (see Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2. Mean values of positive and negative teacher emotions in relation to the homework practice (1 = low occurrence; 5 = high occurrence).

To cross-validate these findings, the teachers were also asked in the interviews whether positive or negative emotions dominate from their perspective. In line with the quantitative findings, most of the teachers interviewed (n = 15) claimed that positive emotions were dominant. When prompted to elaborate, they clarified that they have a positive attitude toward homework and strive to implement high-quality homework practices. In addition, they reported that they do not receive negative feedback from students or parents on their homework practices, suggesting that they are satisfied. In contrast, negative emotions dominated among some teachers (n = 6). They argued that homework has the potential to cause negative outcomes such as conflicts with parents, stress, or students feeling overloaded. Finally, two teachers were unsure whether positive or negative emotions dominate, reflecting an ambivalent attitude toward homework.

Looking at the distinct emotions in detail, the teachers mentioned a high variation of positive and negative emotions that are triggered by their homework practice. Specifically, for the positive emotions, they reported feeling hopeful, excited, relieved, empathic, admiration, confident, determined, interested, enthusiastic, inspired, satisfied, proud, fulfilling, and relaxed. In terms of negative emotions, they reported feeling stressed, pity, sad, ineffective, overwhelmed, frustrated, guilty, including having a guilty conscience, ashamed, upset, insecure, disappointed, annoyed, scared, irritable, helpless, perplexed, hopeless, inadequate, and bored. In the following section, these distinct emotions are related to their antecedents.

6.2. What are the antecedents of teachers’ emotions related to their homework practice?

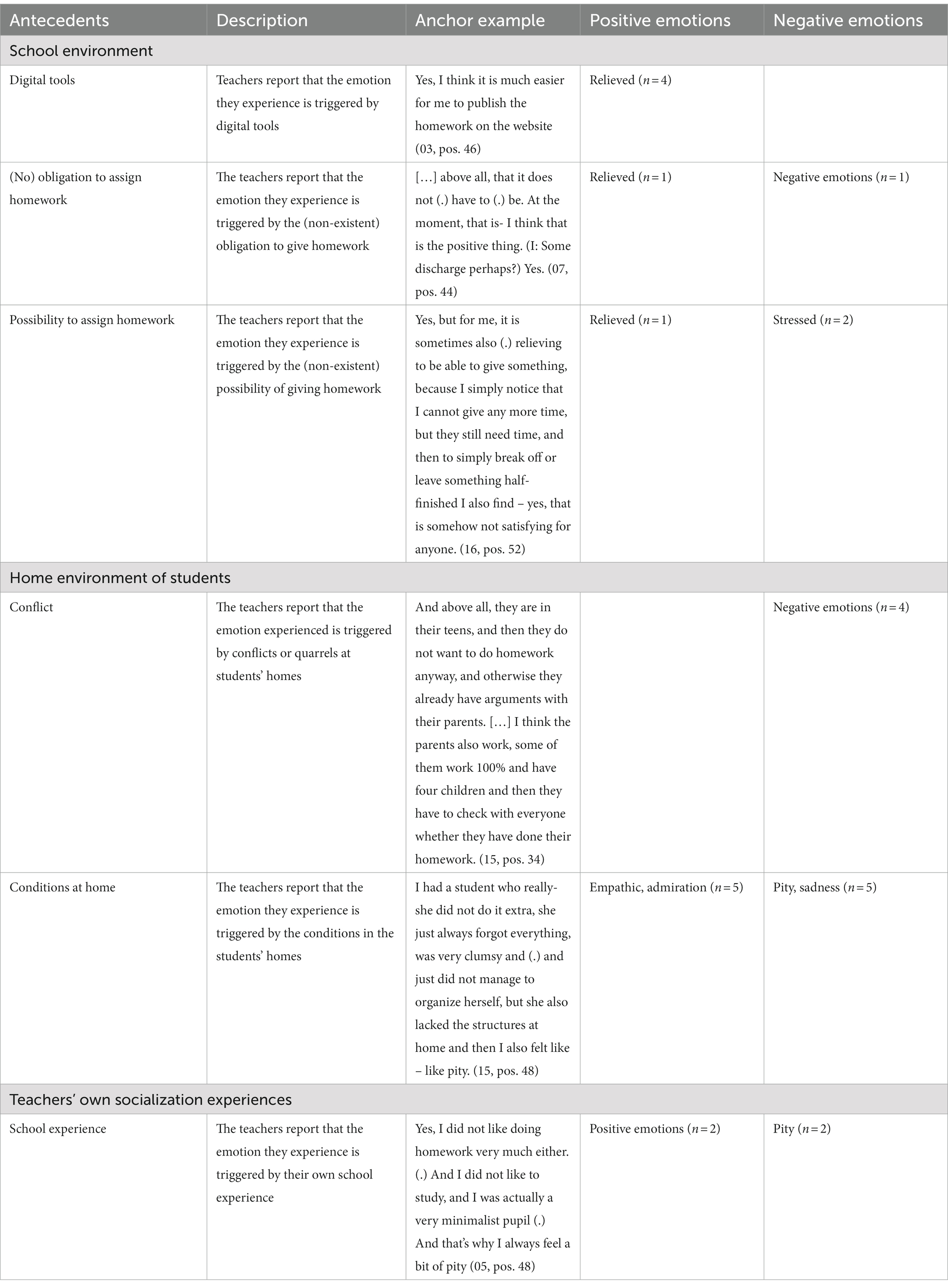

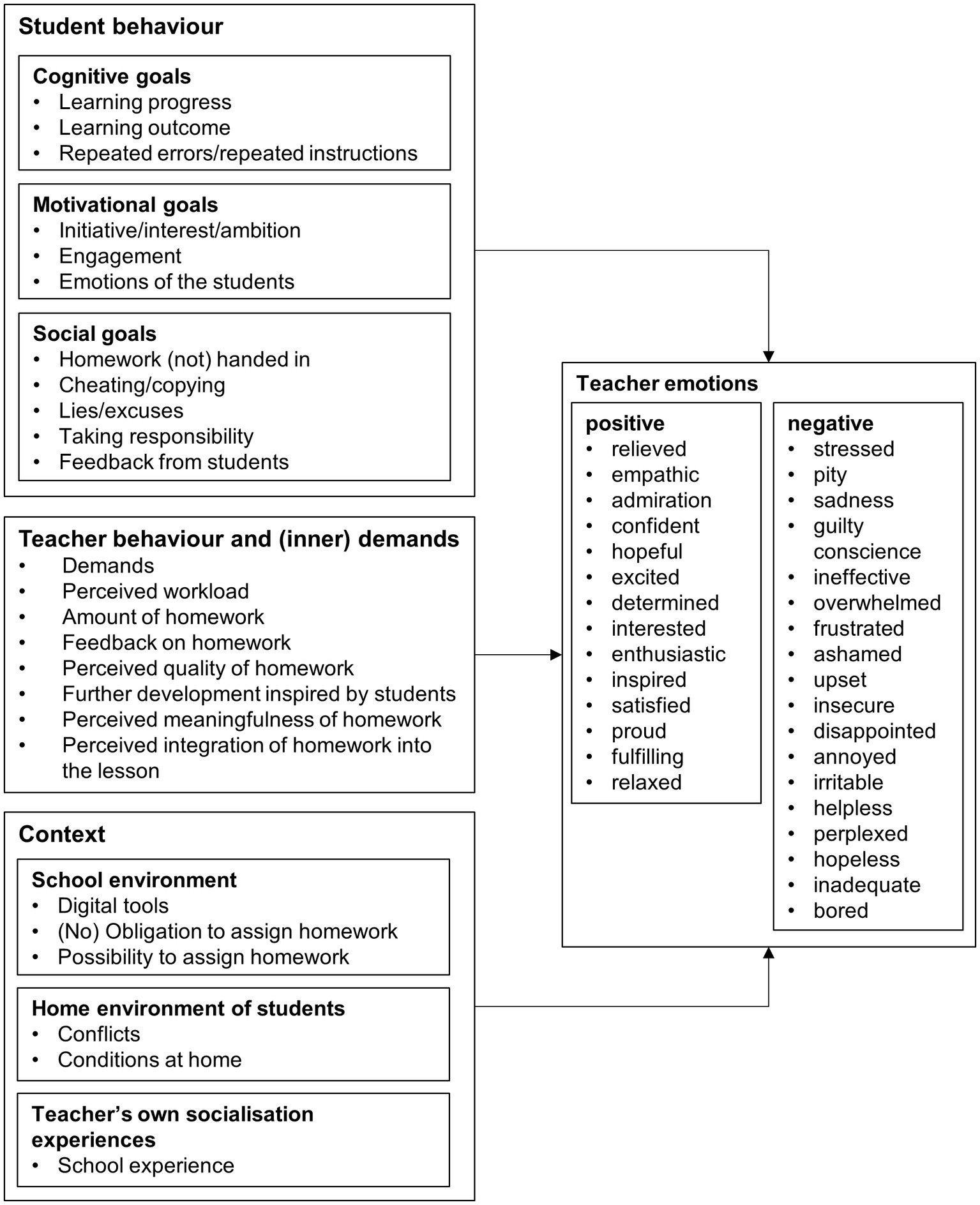

Based on the interview findings, triggers of teachers’ emotions were identified and grouped into three categories: context (Section 6.2.1), teacher behavior and (inner) demands (Section 6.2.2), and student behavior (Section 6.2.3).

6.2.1. Context

Various contextual factors that trigger emotional responses were mentioned (see Table 2). They related to the school environment, the students’ home environments, or the teacher’s own socialization experiences (i.e., their prior experiences with homework).

With regard to the school environment, the teachers reported that they feel relieved that they have access to digital tools. Emotions were also evoked in teachers because they have an/no obligation or the/no possibility of assigning homework. One teacher stated that she is relieved to have the opportunity to assign homework occasionally as this allows her to cover content for which there is too little time in class. Another teacher reported stress because he would like to assign more homework but does not have the opportunity because the students would be overwhelmed.

The teachers seldom mentioned factors related to the students’ home environments in the interviews. However, on some occasions, these conditions did evoke emotions. More concretely, some teachers reported that they feel empathy or pity when students do not have a suitable place at home to work and concentrate. In addition, conflicts between parents and students caused by homework evoked negative emotions in teachers. Regarding positive emotions, the teachers claimed to feel admiration when underachieving students or those who receive little support at home nevertheless work hard to complete their homework.

Finally, the teachers’ own socialization evoked emotions in them. One teacher said he felt sorry for the students because he did not like doing homework himself. In contrast, two teachers reported that they had enjoyed doing homework in their own school years, one particularly emphasizing the subject German because he was especially good at it.

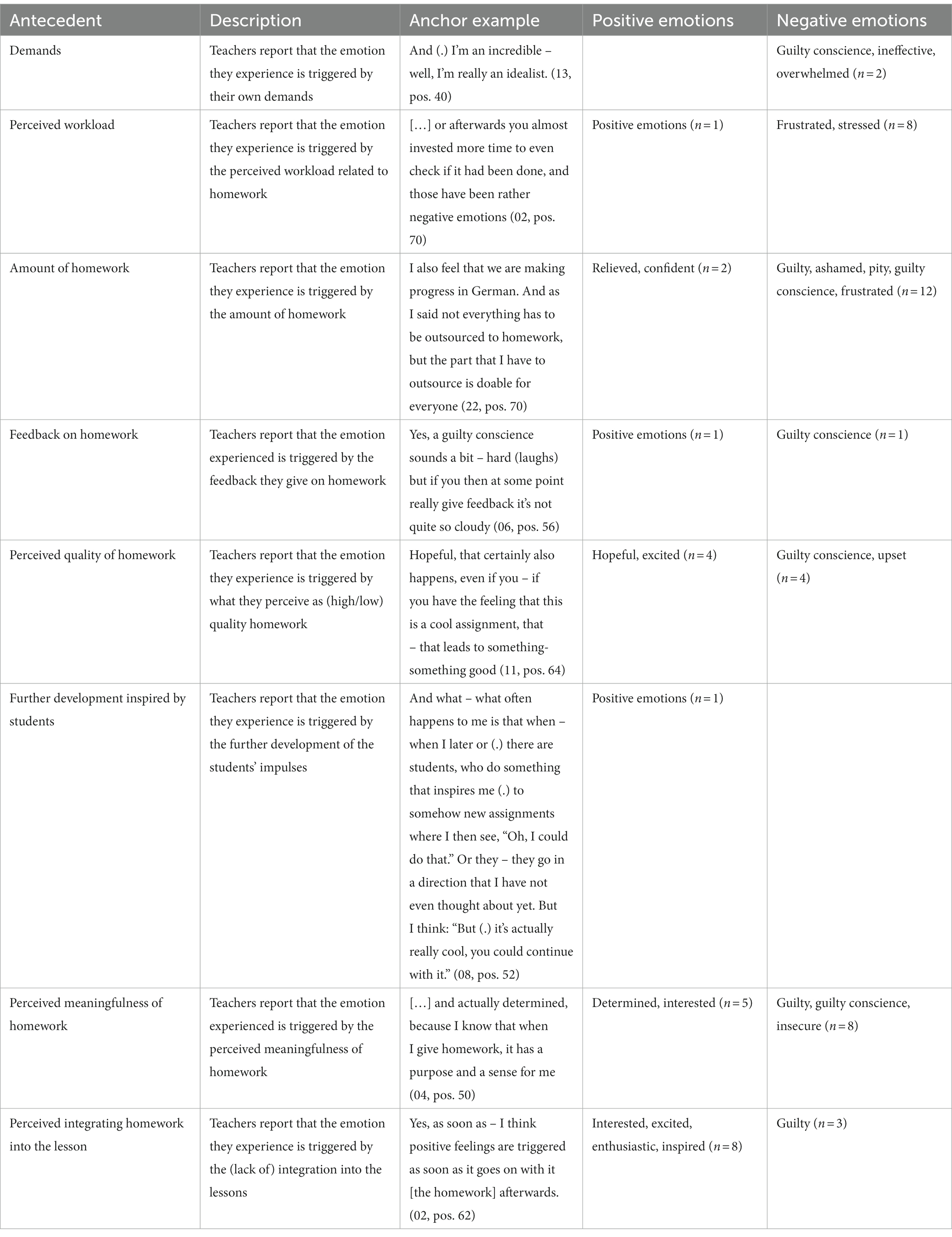

6.2.2. Teacher behavior and (inner) demands

Different aspects of the teacher’s own behavior and (inner) demands triggered emotional responses (see Table 3). For one teacher, her demands and idealism led to a guilty conscience and a feeling of being ineffective and powerless. Several teachers reported feeling frustrated or stressed when the workload (e.g., correcting or preparation) is too high. Only one teacher experienced positive emotions, as she avoided giving homework to keep her workload low:

“I am really a bit wary of giving homework that gives me personally a lot of work.” (11, pos. 50)

The amount of homework assigned by the teachers evoked various emotions. First, the teachers reported feeling relieved when they do not have to assign a lot of homework to students—for example, when the students work productively in class, or when additional homework is unnecessary as the learning objectives have already been reached. Second, some of the teachers reported feeling guilty, ashamed, or pity when they assign homework to students who already have assignments from other teachers or have to study for tests.

The teachers reported experiencing positive emotions when the assigned work is completed well and thus, they can give positive feedback. However, negative emotions such as a guilty conscience can arise if they have to give negative feedback.

The teachers further reported that they are hopeful, excited, and enthusiastic when they assign homework that is perceived as high quality and which they have planned thoroughly. On the contrary, they mentioned experiencing a guilty conscience when they realize that they have put in little effort and/or time to prepare the homework. One teacher reported that she is often inspired by students to create new assignments.

Insecurities can arise during planning if the meaningfulness of homework is questioned. Teachers who doubt this frequently reported feelings of guilt. However, when they give homework that they believe is meaningful, they feel determined and interested. When teachers succeed in integrating homework into the lesson and it leads to discussions, they experience positive emotions such as interest, joy, enthusiasm, or inspiration. In contrast, they reported feeling guilty when they do not integrate homework into the lesson.

“It has also happened that you have done something […] and then you have not reacted at all, so that was – that was not sensible. Then you are really (.) guilty.” (06, pos. 75)

6.2.3. Student behavior

The students’ homework-related behavior triggered the broadest range of emotions in the teachers, defined in terms of the cognitive, motivational, and socio-emotional goals described in the Frenzel (2014) model (see Table 4). The teachers did not describe student behavior related to relational goals.

Cognitive goals were closely linked to learning progress and perceived success. Homework that does not lead to improved learning performance is likely to cause frustration, disappointment, and anger. One teacher reported experiencing a guilty conscience when particularly diligent students who complete their homework are still not successful. However, when learning goals are achieved, the teachers frequently reported feeling excited, enthusiastic, and satisfied. When students who have difficulties with the content succeed, teachers have indicated that they are enthusiastic, proud, and relieved.

In addition to the learning process and progress, the students’ learning outcomes (results/products) caused an array of emotions in the teachers. If the students do not meet the teachers’ expectations, disappointment or anger is likely to arise. The teachers reported being annoyed, frustrated, or upset when the students’ mistakes are repeated, or they have to repeat their instructions several times. However, more teachers reported positive emotions related to student outcomes, including joy, enthusiasm, admiration, pride, satisfaction, and interest.

As described in the model on teachers’ emotions (Frenzel, 2014), teachers also pursue motivational goals during instruction, which becomes salient in relation to homework practice. The teachers frequently mentioned that the students’ initiative, interest, and ambition trigger positive emotions in them. For example, the teachers reported that they feel satisfaction, fulfillment, or joy when students voluntarily engage in school-related tasks at home or show interest in the content that has been discussed at school. However, if the students lack motivation, frustration can occur.

The teachers also reported feeling disappointed and upset as a result of a lack of student engagement. Conversely, high student engagement goes hand in hand with joy, enthusiasm, satisfaction, fulfillment, admiration, and pride. One teacher reported that he feels hopeful and confident when he notices that a formerly disinterested student suddenly develops motivation and engagement.

In addition, the teachers revealed that their emotions are strongly related to those of their students, suggesting emotion transmission effects. Teachers indicated they feel guilty when students’ emotions about homework are negative. One teacher reported that he sometimes gets upset with himself when he overloads his students with homework. Positive emotions among students corresponded with emotions such as joy or enthusiasm in teachers.

Finally, teachers reported that they experience emotions related to the students’ achievement of social goals. Students are responsible for fulfilling their role as learners by behaving in a socially appropriate manner and in accordance with the norms and standards of their respective learning environment.

Most of the teachers’ negative emotions were triggered by homework that is not handed in by students. Teachers reported feeling anger and stress because they cannot progress in class. They feel frustrated, disappointed, upset, irritable, perplexed, helpless, and even hopeless when the same students repeatedly fail to complete homework. In addition, some teachers confessed to feeling insecure and incompetent because, from their perspective, they have failed to establish a positive homework culture.

“Yes, being hopeless is sometimes a bit difficult, but when there are really students who don't succeed in this subject or in that subject and maybe not even in German, then maybe sometimes the question is: How could we tackle this now?” (03, pos. 58)

One teacher reported that he feels empathic when a student does not do homework due to a difficult situation at home; he then works with the pupil to seek a solution. Another teacher reported that she feels bored when the same situation occurs repeatedly. Unfinished homework can lead to conflicts at school between teachers and students, which cause negative feelings.

Two closely related phenomena are cheating on or copying homework, which is interpreted as a failure to meet social goals. The same is true of students who lie or make excuses, which also evoke negative emotions among teachers. The particular emotion that is triggered depends on who is considered responsible for the behavior. When teachers are blamed, they are likely to feel insecure; however, when teachers do not attribute the behavior to themselves but regard the students as responsible, they experience anger (directed toward the students).

Homework completion evokes positive emotions in teachers because it demonstrates that students are meeting social goals. Teachers reported being happy when homework is done, although experiences differed. One teacher reported that she feels confident that when students do not do their homework, it is usually for a good reason and not due to a general rejection of homework.

Similarly, when students take responsibility and succeed in organizing themselves, teachers mentioned feeling relaxed, satisfied, and excited. In contrast, the teachers reported that they feel pity and frustration when the students do not take responsibility and organize themselves to complete their homework.

Finally, feedback from students triggered emotions in teachers, with positive feedback leading to positive emotions and negative feedback leading to negative emotions, such as frustration in one teacher. One teacher reported that she can also be irritable when she receives negative feedback that is not justified.

To conclude and summarize the results related to our main research question, the teachers reported various positive and negative emotions and the factors that trigger them. These features are illustrated in a conceptual model of teachers’ emotions related to homework practices (see Figure 3).

7. Discussion

The overall aim of this study was to investigate the emotions triggered in teachers by homework-related issues. It was found that for the majority of teachers, positive emotions dominated negative emotions. A positive emotional pattern in teachers when teaching was also found in the majority of previous studies (Keller et al., 2014; Anttila et al., 2016). Nevertheless, when prompted to identify specific situations which triggered an emotional response, the teachers mentioned just as many negative situations as positive ones. Many different triggers of teachers’ emotions were mentioned and described, which were categorized according to contextual conditions, teachers’ behavior and (inner) demands, and students’ behavior.

In line with previous research and the theoretical model of teachers’ emotions (Frenzel, 2014), the present study underlines the importance of the students’ cognitive, motivational, and socio-emotional behavior. More concretely, teachers reported that they experience joy when they perceive or experience students as motivated, engaged, interested, and disciplined e.g., (see also Chang, 2020). In contrast, they explained that they feel frustration or anger when students are not engaged or disciplined e.g., (see also Becker et al., 2015). It was also confirmed that teachers experience positive emotions when they observe students making progress e.g., (see also Wu and Chen, 2018). In line with Prawatt et al. (1983), this study found that teachers experience joy as a result of their students’ achievements and outcomes. Additionally, previous studies (Becker et al., 2014; Frenzel et al., 2021; Keller and Lazarides, 2021) have shown that the teachers’ emotions are related to those of the students—identified as the emotion transfer effect, which was also reflected in the present study. Consistent with Chen (2019, 2020), this study further showed that negative emotions arise in teachers when students do not take responsibility for their learning; a central goal of self-regulated learning environments, which gained additional attention during the COVID-19 pandemic when students had to cope with distance learning (Berger et al., 2021).

In addition to the many findings that align with prior research on teachers’ emotions and the factors that trigger them, the study also produced some unexpected results. First, the teachers did not report the emotions of anxiety. This may be due to the fact that inexperienced teachers were excluded from the study; previous studies have found that inexperienced teachers and student teachers experience more anxiety than experienced teachers (Sutton and Wheatley, 2003; Chang, 2009). The results so far also indicate that anxiety is mainly experienced with regard to classroom management (for example, Oral, 2012 for student teachers). This is less relevant in the context of homework practice. However, it could have been assumed that teachers may be anxious about correcting homework and giving feedback to students, because, for example, correcting essays is a rather complex task. However, this assumption was not confirmed in the present data. In this case, teaching experience could have played a moderating role.

Second, the students’ relational behavior was not stressed as an important factor influencing the teachers’ emotions. In this regard, the data collection method may have played a role. Previous studies have revealed that relational behavior is an important antecedent of teachers’ emotions when measured by a questionnaire, but it is stressed less often when teachers are asked directly about concrete, emotion-laden situations (e.g., Hagenauer and Hascher, 2018). Therefore, relational aspects may be less explicit than, for example, socio-emotional behaviors and thus, harder to explicitly describe and reflect on. However, recent research has shown the importance of teacher–student relationships in behavior and well-being (Roorda et al., 2011; Spilt et al., 2011). Consequently, the perception that high-quality, goal-oriented homework is likely to affect the quality of teacher–student relationships (Wentzel, 2012; Wettstein and Raufelder, 2021) should not be ignored. Future research may use additional methods (e.g., intensive longitudinal methods such as diaries or experience sampling) to explore this link in depth (Goetz et al., 2016).

Third, concerning the factors that trigger emotions, the results show, in accordance with Frenzel’s model on teachers’ emotions (Frenzel, 2014) that the emotions related to homework practice are also triggered primarily by the behavior of the students. This implies that the model can also be applied well to the specific area of a teachers’ responsibility, namely homework practice. Yet, the results also show that teacher-determined and contextual factors are responsible for teachers’ emotions as well. These findings underscore that teachers set high standards for their professional practices. Depending on their evaluation of whether they meet the standards (e.g., by assigning differentiated homework) or not (e.g., by assigning too much homework), they experience either positive or negative emotions. Thus, teachers evaluate their students’ behavior and critically evaluate their own professional behavior simultaneously. This finding supports the idea that the teaching profession demands high moral standards—both in general (De Ruyter and Kole, 2010) and in terms of homework practices—which leads to guilt among teachers who feel they do not meet them.

Furthermore, the findings also show that the wider context needs to be considered when discussing the emotional value of homework practices. This is reasonable, as contextual factors (e.g., the [lack of] support at home) influence whether teachers can achieve their goals. Previous research has repeatedly shown that how parents support their children is significantly related to homework behavior and student achievement (Pomerantz and Eaton, 2001; Moroni et al., 2015). However, school-level (e.g., a place to do homework at school) and system-level contextual factors (e.g., the number of lessons per week) also influence homework practices and ultimately affect teachers’ emotions.

7.1. Strengths, limitations, and future research

Based on an explorative approach, the present study has shown that teachers’ emotions can also be examined context-specifically for the teacher’s area of responsibility “homework practice.” Following the results, the model of teachers’ emotions (Frenzel, 2014), which specifies the antecedents of teachers’ emotions, can be transferred to teachers’ emotions related to homework practice, but additionally, it should be extended to include further antecedents at the teachers’ level and at the context level. Through the exploratory approach the diversity of teachers’ emotions in the homework process could be illustrated and the diverse antecedents of these emotions could be identified in depth.

Still, from an exploratory perspective, the study has some limitations as well. First, the findings represent the experiences of secondary teachers from the canton of Bern. By purposively selecting these cases, we have tried to obtain a selection that is as comprehensive as possible in terms of the school models existing in the canton of Bern. Nevertheless, further quantitative studies need to follow. These studies could test possible differences in the emotional experiences of teachers working in different school models. In our small-scale study, these group differences could not be reliably explored. In addition, further studies based on different samples in different contexts are needed, which would allow a generalization of the results beyond the Swiss (Bernese) context. If such quantitative studies are conducted, when developing measurement instruments, consideration should be given to mapping the diversity of the emotional experiences of teachers. Classical instruments, such as the Teacher Emotions Scales (TES; Frenzel et al., 2016) which were developed for teaching in general, may fall short when it comes to the specific context of homework practice. Even if anxiety, anger, and enjoyment (i.e., the core emotions of the TES) are relevant teachers’ emotions related to homework practice, other emotions, such as satisfaction, disappointment, stress, or guilt (including having a guilty conscience) should also be considered in such measurement instruments. Furthermore, the link between teachers’ emotions and homework quality needs further exploration. As a reciprocal relationship can be assumed, a complex longitudinal design needs to be applied. Second, the teachers’ emotions were measured retrospectively. It can be assumed that the teachers mainly described situations that were either very close in time or in which the emotions were experienced intensely (Heuer and Reisberg, 1992). Future studies should therefore also use situational measurements (e.g., experience sampling methods). Another limitation is that the results were based on self-reporting. This can lead to bias; for example, the teachers may have answered in a socially desirable way. We countered this effect by ensuring full anonymity and by creating a trusting environment during the interviews. It must also be mentioned that the subjective assessment of emotions is still a valid way to capture the affective core of emotions, i.e., the subjective feeling that cannot be observed. Nevertheless, if a multicomponent approach to emotions is pursued, future studies can, for example, use further data collection methods, such as physiological measures accounting for the physical arousal of emotions. Finally, it should be noted that the teachers were explicitly asked about their emotions in connection with homework. This has the advantage that teachers have purposefully reflected on their emotions and their antecedents. However, such an approach presupposes a conscious reflection on emotions by the teachers. Another pre-assumption of this study was that emotions occur in the homework process, which is why we opted for the explicit approach to explore teachers’ emotions. For future research, it would be interesting to complement these explicit approaches to capturing emotions with implicit approaches by attempting to reconstruct teachers’ emotional experiences through, for example, narrative interviews.

7.2. Conclusion and practical implications

This study has provided a first insight into the emotional experiences of Swiss secondary teachers teaching German during the homework process and has also identified the multiple influencing conditions of these emotions. On a theoretical level, the results of this study extend the research findings on teachers’ emotions by focusing on homework practices as a specific area of action in the classroom. They enable Frenzel’s (2014) model of teachers’ emotions in the classroom to be differentiated by focusing on this specific aspect of teaching. Overall, the results clearly showed that the homework process is definitely experienced emotionally by teachers. Even though homework is done by students at home, it is still the students and their behavior that are the most emotionally relevant source for teachers’ emotions. This result is due to the fact that the homework process also includes significant teacher–student interactions in class (e.g., homework return and discussion), as well as the fact that student behavior is also visible in the quality of homework completion. Teachers, for example, are happy about the students’ learning progress that they diagnose from the homework, or they are annoyed when the students do not put in enough effort or cheat on homework. However, the demands that teachers place on themselves are also often sources of their emotions (e.g., “inner demands”), and contextual factors also influence their emotional experience (e.g., experiencing pity due to unfavorable conditions at home).

From a practical point of view, the results provide some implications for teacher education and training in Switzerland. First and foremost, pre-service teachers should acquire basic knowledge about the development of emotions and their influence on teaching and learning. In-service teachers should also be sensitized to this through professional development programs. For example, a training program developed by Carstensen et al. (2019) focusses specifically on fostering teachers’ socio-emotional competencies. If teachers develop socio-emotional competencies, they are more likely to recognize automatic patterns of action that occur due to their own emotions and thus will be better able to interrupt negative spirals that can arise from them. This could have a positive impact on the quality of the homework they assign and subsequently the behavior of the students. Teachers who can regulate their emotions appropriately (e.g., by applying cognitive reappraisal when students do not hand in their homework) are less likely to let their emotional reactions interfere with their professional teaching behavior.

These skills also have an impact on building and maintaining meaningful teacher–student relationships (Carstensen et al., 2019), which positively influence the students’ engagement and achievement (Roorda et al., 2011). Previous research has shown that cheating amongst university students is lower when the instructor is evaluated positively (Stearns, 2001) in terms of teacher–student relationships and enthusiasm (Orosz et al., 2015). Building on these findings, meaningful teacher–student relationships might decrease the triggers of negative teachers’ emotions, as students who are satisfied with their teachers are less likely to cheat on, copy, or lie about their homework and complete it more reliably.

Finally, pre-service and in-service teachers should be specifically trained in assigning high-quality homework. The results of this study demonstrate that positive emotions in teachers can be evoked by their students’ learning progress, learning outcomes, and engagement. Previous studies have shown that homework quality can promote student achievement (Rosário et al., 2018) and engagement (Trautwein et al., 2006). Assigning high-quality homework can have positive effects on both the students’ learning and the teacher’s own emotional experiences. During the training, teachers could also learn how to follow up on completed homework during class, as it was found that being unable to use homework in class leads to negative emotions.

Data availability statement

The dataset presented in this article is not readily availabel because it currently forms an essential part of the first author’s qualification phase. Requests to access the dataset should be directed to CF, Y2hyaXN0aW5lLmZlaXNzQHBoc2cuY2g=.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CF conceived, planned, and conducted the study. In addition, CF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GH and SM were closely involved in the process and contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1239443/full#supplementary-material

References

An, S., Ji, L.-J., Marks, M., and Zhang, Z. (2017). Two sides of emotion: exploring positivity and negativity in six basic emotions across cultures. Front. Psychol. 8, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00610

Anttila, H., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., and Pietarinen, J. (2016). How does it feel to become a teacher? Emotions in teacher education. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 19, 451–473. doi: 10.1007/s11218-016-9335-0

Baş, G., Şentürk, C., and Ciğerci, F. M. (2017). Homework and academic achievement: a meta-analytic review of research. Issues Educ. Res. 27, 31–50.

Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., Morger, V., and Ranellucci, J. (2014). The importance of teachers' emotions and instructional behavior for their students' emotions – An experience sampling analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 43, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.002

Becker, E. S., Keller, M. M., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., and Taxer, J. L. (2015). Antecedents of teachers' emotions in the classroom: An intraindividual approach. Front. Psychol. 6:635. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00635

Berger, F., Schreiner, C., Hagleitner, W., Jesacher-Rößler, L., Roßnagl, S., and Kraler, C. (2021). Predicting coping with self-regulated distance learning in times of COVID-19: evidence from a longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 12:701255. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.701255

Brennan, R. L., and Prediger, D. J. (1981). Coefficient kappa: some uses, misuses, and alternatives. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 41, 687–699. doi: 10.1177/001316448104100307

Breyer, B., and Bluemke, M. (2016). Deutsche version der positive and negative affect schedule PANAS (GESIS panel). Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items Skalen. doi: 10.6102/zis242

Burić, I., and Frenzel, A. C. (2021). Teacher emotional labour, instructional strategies, and students' academic engagement: a multilevel analysis. Teach. Teach. 27, 335–352. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2020.1740194

Carstensen, B., Köller, M., and Klusmann, U. (2019). Förderung sozial-emotionaler Kompetenz von angehenden Lehrkräften. Zeitschrift Für Entwicklungspsychologie Pädagogische Psychologie 51, 1–15. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637/a000205

Chang, M.-L. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: examining the emotional work of teachers. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 21, 193–218. doi: 10.1007/s10648-009-9106-y

Chang, M.-L. (2020). Emotion display rules, emotion regulation, and teacher burnout. Front. Educ. 5:90. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00090

Chen, J. (2019). Exploring the impact of teacher emotions on their approaches to teaching: a structural equation modelling approach. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 57–74. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12220

Chen, J. (2020). Teacher emotions in their professional lives: implications for teacher development. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 48, 491–507. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2019.1669139

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., and Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Rev. Educ. Res. 76, 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

De Ruyter, D. J., and Kole, J. J. (2010). Our teachers want to be the best: on the necessity of intra-professional reflection about moral ideals of teaching. Teach. Teach., 16, 207–218. doi: 10.1080/13540600903478474

Dettmers, S., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., and Pekrun, R. (2011). Students’ emotions during homework in mathematics: testing a theoretical model of antecedents and achievement outcomes. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.001

Dettmers, S., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Kunter, M., and Baumert, J. (2010). Homework works if homework quality is high: using multilevel modeling to predict the development of achievement in mathematics. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 467–482. doi: 10.1037/a0018453

Dettmers, S., Yotyodying, S., and Jonkmann, K. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of parental homework involvement: how do family-school partnerships affect parental homework involvement and student outcomes? Front. Psychol. 10:1048. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01048

DiStefano, M., O’Brien, B., Storozuk, A., Ramirez, G., and Maloney, E. A. (2020). Exploring math anxious parents’ emotional experience surrounding math homework-help. Int. J. Educ. Res. 99:101526. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101526

Dreer, B. (2021). Teachers’ well-being and job satisfaction: the important role of positive emotions in the workplace. Educ. Stud. 1–17, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2021.1940872

Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Neumann, M., Niggli, A., and Schnyder, I. (2012). Does parental homework involvement mediate the relationship between family background and educational outcomes? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 37, 55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.09.004

Ellsworth, P. C., and Scherer, K. R. (2003). “Appraisal processes in emotion” in Series in affective science. Handbook of affective sciences. eds. R. J. Davidson, H. H. Goldsmith, and K. R. Scherer (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 572–595.

Else-Quest, N. M., Hyde, J. S., and Hejmadi, A. (2008). Mother and child emotions during mathematics homework. Math. Think. Learn. 10, 5–35. doi: 10.1080/10986060701818644

Epstein, J. L., and van Voorhis, F. L. (2012). “The changing debate: from assigning homework to designing homework” in Contemporary debates in childhood education and development. ed. S. Suggate (London: Routledge), 263–273.

Fan, H., Xu, J., Cai, Z., He, J., and Fan, X. (2017). Homework and students' achievement in math and science: a 30-year meta-analysis, 1986–2015. Educ. Res. Rev. 20, 35–54. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2016.11.003

Fernández-Alonso, R., Woitschach, P., Álvarez-Díaz, M., González-López, A. M., Cuesta, M., and Muñiz, J. (2019). Homework and academic achievement in Latin America: a multilevel approach. Front. Psychol. 10:95. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00095

Flunger, B., Trautwein, U., Nagengast, B., Lüdtke, O., Niggli, A., and Schnyder, I. (2015). The Janus-faced nature of time spent on homework: using latent profile analyses to predict academic achievement over a school year. Learn. Instr. 39, 97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.05.008

Forsberg, L. (2007). Homework as serious family business: power and subjectivity in negotiations about school assignments in Swedish families. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 28, 209–222. doi: 10.1080/01425690701192695

Frenzel, A. C. (2014). “Teacher emotions” in Educational psychology handbook series. International handbook of emotions in education. eds. R. Pekrun and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (New York: Routledge), 494–519.

Frenzel, A. C., Daniels, L., and Burić, I. (2021). Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students. Educ. Psychol. 56, 250–264. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2021.1985501

Frenzel, A. C., Fiedler, D., Marx, A. K. G., Reck, C., and Pekrun, R. (2020). Who enjoys teaching, and when? Between- and within-person evidence on teachers' appraisal-emotion links. Front. Psychol. 11:1092. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01092

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., and Sutton, R. E. (2009a). Emotional transmission in the classroom: exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 705–716. doi: 10.1037/a0014695

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Stephens, E. J., and Jacob, B. (2009b). “Antecedents and effects of teachers' emotional experiences: An integrated perspective and empirical test” in Advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers' lives. eds. P. A. Schutz and M. Zembylas (New York: Springer), 129–151.

Frenzel, A. C., Götz, T., and Pekrun, R. (2008). “Ursachen und Wirkungen von Lehreremotionen: Ein Modell zur reziproken Beeinflussung von Lehrkräften und Klassenmerkmalen” in Lehrerexpertise: Analyse und Bedeutung unterrichtlichen Handelns. ed. M. Gläser-Zikuda (Münster: Waxmann), 187–209.

Frenzel, A. C., Götz, T., and Pekrun, R. (2015). “Emotionen” in Pädagogische Psychologie. eds. E. Wild and J. Möller. 2. Auflage ed (Berlin Heidelberg: Springer), 201–224.

Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Durksen, T. L., Becker-Kurz, B., et al. (2016). Measuring teachers' enjoyment, anger, and anxiety: the teacher emotions scales (TES). Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 46, 148–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.003

Fried, L., Mansfield, C., and Dobozy, E. (2015). Teacher emotion research: introducing a conceptual model to guide future research. Issues Educ. Res. 25, 415–441.

Fuss, S., and Karbach, U. (2019). Grundlagen der Transkription: Eine praktische Einführung. 2nd Edn. Opladen Toronto: Barbara Budrich.

Georgiou, S. N., Christou, C., Stavrinides, P., and Panaoura, G. (2002). Teacher attributions of student failure and teacher behavior toward the failing student. Psychol. Sch. 39, 583–595. doi: 10.1002/pits.10049

Goetz, T., Bieg, M., and Hall, N. C. (2016). “Assessing academic emotions via the experience sampling method” in Methodological advances in research on emotion and education. eds. M. Zembylas and P. A. Schutz (Stuttgart: Springer), 245–258.

Goetz, T., Cronjaeger, H., Frenzel, A. C., Lüdtke, O., and Hall, N. C. (2010). Academic self-concept and emotion relations: domain specificity and age effects. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 35, 44–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2009.10.001

Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., and Hall, N. C. (2006). The domain specificity of academic emotional experiences. J. Exp. Educ. 75, 5–29. doi: 10.3200/JEXE.75.1.5-29

Goetz, T., Nett, U. E., Martiny, S. E., Hall, N. C., Pekrun, R., Dettmers, S., et al. (2012). Students' emotions during homework: structures, self-concept antecedents, and achievement outcomes. Learn. Individ. Differ. 22, 225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.006

Hagenauer, G., and Hascher, T. (2018). Bedingungsfaktoren und Funktionen von Emotionen von Lehrpersonen im Unterricht. Unterrichtswissenschaft 46, 141–164. doi: 10.1007/s42010-017-0010-8

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., and Volet, S. E. (2015). Teacher emotions in the classroom: associations with students' engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30, 385–403. doi: 10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0

Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotional practice of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 14, 835–854. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00025-0

Hascher, T., and Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: a systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educ. Res. Rev. 34:100411. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100411

Heuer, F., and Reisberg, D. (1992). “Emotion, arousal, and memory for detail” in The handbook of emotion and memory: Research and theory. ed. S.-Å. Christianson (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 151–180.

Keller, M. M., Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Pekrun, R., and Hensley, L. (2014). “Exploring teacher emotions: a literature review and an experience sampling study” in Teacher motivation: Theory and practice. eds. P. W. Richardson, H. M. G. Watt, and S. A. Karabenick (New York: Routledge), 69–82.

Keller, M. M., and Lazarides, R. (2021). “Effekte von Lehreremotionen auf Unterrichtsgestaltung und Schüleremotionen: Eine Tagebuchstudie im Fach Mathematik” in Emotionen in Schule und Unterricht: Bedingungen und Auswirkungen von Emotionen bei Lehrkräften und Lernenden. eds. C. Rubach and R. Lazarides (Opladen Berlin Toronto: Barbara Budrich), 108–127.

Kleinginna, P. R., and Kleinginna, A. M. (1981). A categorized list of emotion definitions, with suggestions for a consensual definition. Motiv. Emot. 5, 345–379. doi: 10.1007/BF00992553

Knollmann, M., and Wild, E. (2007). Quality of parental support and students' emotions during homework: moderating effects of students' motivational orientations. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 22, 63–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03173689

Kuckartz, U. (2010). Einführung in die computergestützte Analyse qualitativer Daten. 3rd Edn. Wiesbaden: VS.

Landis, J. R., and Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310

Mayring, P. (2017). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt: Beltz.

Mevarech, Z. R., and Maskit, D. (2015). The teaching experience and the emotions it evokes. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 18, 241–253. doi: 10.1007/s11218-014-9286-2

Moè, A., and Katz, I. (2018). Brief research report: parents’ homework emotions favor students’ homework emotions through self-efficacy. J. Exp. Educ. 86, 597–609. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2017.1409180

Moroni, S., Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Niggli, A., and Baeriswyl, F. (2015). The need to distinguish between quantity and quality in research on parental involvement: the example of parental help with homework. J. Educ. Res. 108, 417–431. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2014.901283

Oral, B. (2012). Student Teachers' classroom management anxiety: a study on behavior management and teaching management. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, 2901–2916. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00966.x

Orosz, G., Tóth-Király, I., Bőthe, B., Kusztor, A., Kovács, Z. Ü., and Jánvári, M. (2015). Teacher enthusiasm: a potential cure of academic cheating. Front. Psychol. 6:318. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00318

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., and Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in Students' self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 37, 91–105. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

Pekrun, R., and Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). “Academic emotions and student engagement” in Handbook of research on student engagement. eds. S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (New York: Springer), 259–282.

Pekrun, R., and Marsh, H. W. (2022). Research on situated motivation and emotion: Progress and open problems. Learn. Instr. 81:101664. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101664

Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Elliot, A. J., Stockinger, K., Perry, R. P., Vogl, E., et al. (2023). A three-dimensional taxonomy of achievement emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 124, 145–178. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000448

Pelikan, E. R., Lüftenegger, M., Holzer, J., Korlat, S., Spiel, C., and Schober, B. (2021). Learning during COVID-19: the role of self-regulated learning, motivation, and procrastination for perceived competence. Z. Erzieh. 24, 393–418. doi: 10.1007/s11618-021-01002-x

Pomerantz, E. M., and Eaton, M. M. (2001). Maternal intrusive support in the academic context: transactional socialization processes. Dev. Psychol. 37, 174–186. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.174

Prawatt, R. S., Byers, J. L., and Anderson, A. H. (1983). An attributional analysis of teachers' affective reactions to student success and failure. Am. Educ. Res. J. 20, 137–152. doi: 10.3102/00028312020001137

Reyna, C., and Weiner, B. (2001). Justice and utility in the classroom: An attributional analysis of the goals of teachers' punishment and intervention strategies. J. Educ. Psychol. 93, 309–319. doi: 10.1037//0022-0663.93.2.309

Rodríguez, S., Núñez, J. C., Valle, A., Freire, C., Ferradás, M. D. M., and Rodríguez-Llorente, C. (2019). Relationship between students' prior academic achievement and homework behavioral engagement: the mediating/moderating role of learning motivation. Front. Psychol. 10:1047. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01047

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., and Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students' school engagement and achievement. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 493–529. doi: 10.3102/0034654311421793

Rosário, P., Carlos Núñez, J., Vallejo, G., Nunes, T., Cunha, J., Fuentes, S., et al. (2018). Homework purposes, homework behaviors, and academic achievement. Examining the mediating role of students' perceived homework quality. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 53, 168–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.04.001

Scherer, K. R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Soc. Sci. Inf. 44, 695–729. doi: 10.1177/0539018405058216

Schutz, P. A., and Lanehart, S. L. (2002). Introduction: emotions in education. Educ. Psychol. 37, 67–68. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3702_1

Shuman, V., and Scherer, K. R. (2014). “Concepts and structures of emotions” in Educational psychology handbook series. International handbook of emotions in education. eds. R. Pekrun and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (New York: Routledge), 13–35.

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., and Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: the importance of teacher–student relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23, 457–477. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

Stearns, S. A. (2001). The student-instructor relationship's effect on academic integrity. Ethics Behav. 11, 275–285. doi: 10.1207/S15327019EB1103_6

Sutton, R. E. (2005). Teachers' emotions and classroom effectiveness: implications from recent research. Clear. House 78, 229–234. doi: 10.2307/30189914

Sutton, R. E. (2007). “Teachers' anger, frustration, and self-regulation” in Emotion in education. eds. P. A. Schutz and R. Pekrun (Amsterdam: Academic Press), 259–274.

Sutton, R. E., and Wheatley, K. F. (2003). Teachers' emotions and teaching: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 4, 327–358. doi: 10.1023/A:1026131715856

Trautwein, U., Köller, O., and Baumert, J. (2001). Lieber oft als viel: Hausaufgaben und die Entwicklung von Leistung und Interesse im Mathematik-Unterricht der 7. Jahrgangsstufe. Zeitschrift Pädagogik 47, 703–724. doi: 10.25656/01:4310

Trautwein, U., Köller, O., Schmitz, B., and Baumert, J. (2002). Do homework assignments enhance achievement? A multilevel analysis in 7th-grade mathematics. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 27, 26–50. doi: 10.1006/ceps.2001.1084

Trautwein, U., and Lüdtke, O. (2007). Students' self-reported effort and time on homework in six school subjects: between-students differences and within-student variation. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 432–444. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.432

Trautwein, U., and Lüdtke, O. (2008). “Die Förderung der Selbstregulation durch Hausaufgaben: Herausforderungen und Chancen” in Kompetenz-Bildung: Soziale, emotionale und kommunikative Kompetenzen von Kindern und Jugendlichen. eds. C. Rohlfs, M. Harring, and C. Palentien (Wiesbaden: VS), 239–251.

Trautwein, U., and Lüdtke, O. (2009). Predicting homework motivation and homework effort in six school subjects: the role of person and family characteristics, classroom factors, and school track. Learn. Instr. 19, 243–258. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.05.001

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Schnyder, I., and Niggli, A. (2006). Predicting homework effort: support for a domain-specific, multilevel homework model. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 438–456. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.2.438

Trautwein, U., Niggli, A., Schnyder, I., and Lüdtke, O. (2009a). Between-teacher differences in homework assignments and the development of students’ homework effort, homework emotions, and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 176–189. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.101.1.176

Trautwein, U., Schnyder, I., Niggli, A., Neumann, M., and Lüdtke, O. (2009b). Chameleon effects in homework research: the homework–achievement association depends on the measures used and the level of analysis chosen. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 34, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.09.001

Wentzel, K. R. (2012). Teacher-student relationships and adolescent competence at school. In T. Wubbels, P. Brokden, J. Tartwijkvan, and J. Levy (Eds.), Advances in learning environments research: Vol. 3. Interpersonal relationships in education: An overview of contemporary research. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. (pp. 19–35).

Wettstein, A., and Raufelder, D. (2021). “Beziehungs- und Interaktionsqualität im Unterricht” in Soziale Eingebundenheit. Sozialbeziehungen im Fokus von Schule und Lehrer*innenbildung. eds. G. Hagenauer and D. Raufelder (Münster: Waxmann), 17–31.

Wu, Z., and Chen, J. (2018). Teachers' emotional experience: insights from Hong Kong primary schools. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 19, 531–541. doi: 10.1007/s12564-018-9553-6

Xu, J. (2022). Individual and class-level factors for students' management of homework environment: the self-regulation perspective. Curr. Psychol. 1–15, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02596-5

Keywords: teachers’ emotions, homework, secondary school, qualitative content analysis, interviews, emotional antecedents

Citation: Feiss C, Hagenauer G and Moroni S (2023) “I feel enthusiastic, when the homework is done well”: teachers’ emotions related to homework and their antecedents. Front. Educ. 8:1239443. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1239443

Edited by:

Benjamin Dreer, University of Erfurt, GermanyReviewed by:

Angelica Moè, University of Padua, ItalyEvangelia Karagianni, Hellenic Open University, Greece

Copyright © 2023 Feiss, Hagenauer and Moroni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christine Feiss, Y2hyaXN0aW5lLmZlaXNzQHBoc2cuY2g=

Christine Feiss

Christine Feiss Gerda Hagenauer

Gerda Hagenauer Sandra Moroni

Sandra Moroni