- 1School of Education, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 2Human and Social Sciences, Kore University of Enna, Enna, Italy

The construct of pathological or extreme demand avoidance (EDA) is used to describe the experience of avoiding demands and having an extreme need for control. However, the EDA construct is contested by researchers and educational psychology practitioners. To investigate the utility and validity of the construct of EDA, this qualitative study explored psychologists’ experience and conceptualisation of demand avoidance and extreme demand avoidance, and their approach to working with children and adolescents who avoid demands. Online semi-structured interviews were conducted with 12 psychologists (female = 9) working in private, education and disability services. Thematic analysis yielded six themes: (i) reason for the psychologists’ involvement, (ii) psychologists understanding of child’s presentation, (iii) psychologists’ focus in supporting the child, (iv) challenges for psychologists, (v) enablers for psychologists and (vi) success for psychologists. Results indicated that psychologists do not view the construct of EDA as necessary for their work and achieve success with children who avoid demands by drawing on range of approaches focusing on the underlying needs of those children.

Introduction

The construct of extreme demand avoidance (EDA) was created to refer to children and adults who persistently and vigorously resist ordinary demands owing to their need for control (Newson et al., 2003). However, the evidence base supporting EDA is small, the construct does not appear in diagnostic manuals upon which psychologists rely, and different diagnostic thresholds are described in the existing research (Woods, 2022c). Disagreements exist as to whether EDA occurs within autism (Stuart et al., 2020), across profiles (Gillberg et al., 2015), as a collection of symptoms in autism and beyond (Green et al., 2018) or is a distinct developmental profile (Newson et al., 2003; Woods, 2020).

Whilst some psychologists, e.g., Phil Christie have authored books discussing likely helpful approaches for demand avoidant children, empirical studies have not investigated how psychologists support children with demand avoidant behaviour or whether the construct of EDA is relevant to psychologists’ work (Kildahl et al., 2021). This lack of research into practice has resulted in a lack of clinical guidance for psychologists about how to support children with EDA, which is significant, owing in part to the high levels of stress experienced by those children (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2016; Doyle and Kenny, 2023).

The aims of this study were thus to (a) explore how psychologists conceptualise, experience and approach demand avoidance in children, (b) determine if any accounts of demand avoidance are conceptualised by psychologists as extreme, i.e., EDA and (c) identify if there are parallels between psychologists’ accounts of EDA and the construct of EDA presented in the literature. The study of psychologists’ accounts will help to identify useful practices in supporting children with demand avoidance and will advance the conceptualisation of EDA by identifying if the construct of EDA is something that is relevant to psychologists’ work. Such contributions to the knowledge base are critical to support vulnerable children.

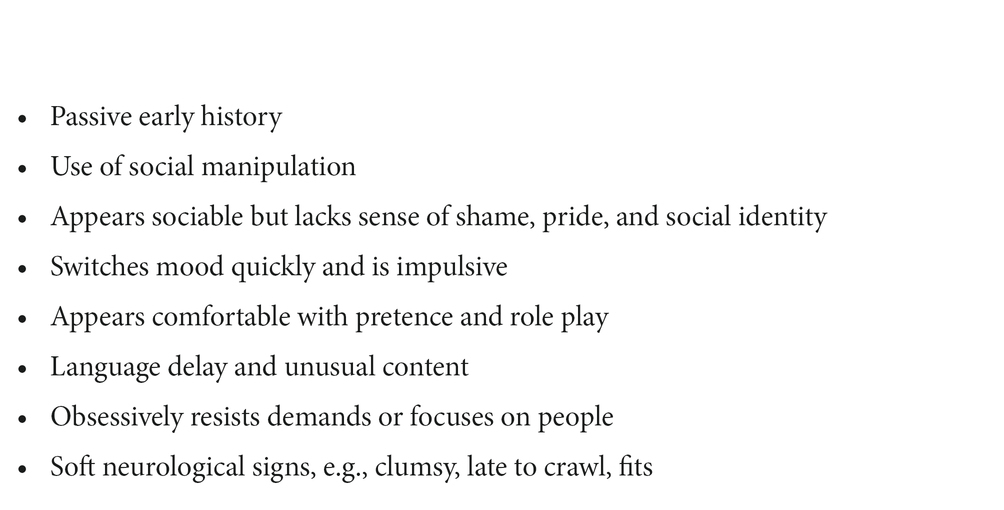

Extreme demand avoidance (EDA) is a behavioural profile characterised by an extreme anxiety driven resistance to ordinary demands and was first described by Newson a clinician, and her colleagues in the 1980s as a pervasive development disorder. Features were identified by Newson et al. (2003) (see Table 1), when children who were referred for autism assessment were qualitatively different than autistic children but similar to each other. The topic has garnered much media and parent attention predominantly in the U.K., but the evidence base on the features of EDA is lacking (Kildahl et al., 2021). Research that does exist is informed by a variety of perspectives largely clinicians, namely clinical and educational psychologists (e.g., Judy Eaton, Phil Christie, Judith Gould, Norah Frederickson) and psychiatrists (e.g., Christopher Gillberg, Johnathan Green) as well as academics interested in the field (e.g., Richard Woods, Elizabeth O’Nions, Alison Moore).

Table 1. Features of extreme demand avoidance described by Newson et al. (2003).

Owing to the broadening of criteria for autism in the DSM-5, researchers now see more commonality between what we understand as autism and Newson’s description of EDA (e.g., Kildahl et al., 2021). Eaton and Weaver (2020) describe that though there were non-autistic people in Newson’s research, they would now likely meet DSM-5 criteria. Autism makes a unique contribution in predicting EDA (White et al., 2022) and many UK authorities such as the Department of Education and charities recognise EDA as a profile within autism. Thus, in explaining EDA, features of autism have been used including, sensory sensitivities, phobias, extreme rigidity, need to conform with expectations (O’Nions et al., 2018), inertia (Milton, 2019), reduced importance of social feedback (O’Nions and Noens, 2018) intolerance of uncertainty (Stuart et al., 2020), cognitive inflexibility (Malik and Baird, 2018), executive function difficulty (O’Nions and Eaton, 2020) and monotropism (Woods, 2018). A different understanding of hierarchy (Moore, 2020) and the role of trauma have also been noted (Woods, 2019). O’Nions and Eaton (2020) concluded that features of EDA are common in autism but that EDA appearing at the level described by Newson described is rare.

Others reject the acceptance of EDA as occurring in autism, describing a lack of consideration for possible alternative explanations recognising that it instead represents a positive source for vulnerable people, reflecting power differences at play (Woods, 2020). Research indicates EDA may occur outside of autism, within other profiles (Daffern et al., 2007; Reilly et al., 2014; Gillberg et al., 2015), as a collection of symptoms (Green et al., 2018) or as a distinct profile, fitting within the obsessive-compulsive related disorders (Woods, 2022c). Some people have compared EDA to ADHD (Egan et al., 2020), anti-social personality disorder (Trundle et al., 2017) and attachment disorder (Milton, 2018). Malik and Baird (2018) acknowledge that for EDA to be considered a distinct entity, it would require that all features are not sufficiently explained by other disabilities or disorders. In trying to elicit common experience, Kildahl et al. (2021) notes using existing criteria of, for example anxiety, may be helpful, particularly when aiming to provide early support. O’Nions et al. (2014) cautions that attention should be paid to common underlying mechanisms. Much of the existing research does not focus on underlying mechanisms and instead relies on Newson’s criteria (White et al., 2022), the validity of which has been questioned (Kildahl et al., 2021).

Explanatory information about EDA could be garnered by eliciting lived experience, biographies such as that co-authored by Fidler and Daunt (2021) are helpful, however, the inclusion of such voices in research studies has been lacking (Kildahl et al., 2021). Some autistic people are highly critical of the construct, rejecting it entirely, viewing it as undermining autistic self-advocacy (Moore, 2020) and as part of an agenda to make autistic people more neurotypical (Milton, 2013). Demand avoidance, considered in this way, sees autistic people as logically avoiding demands set by neurotypical people who have different experiences of communication, sensory information, and anxiety. Whilst the term extreme describes the level of avoidance in this paper as used by Gillberg (2014) and Reilly et al. (2014), Woods (2022c) describes the avoidance as rational in conveying the autistic perspective.

Lack of consensus means that the construct does not appear in diagnostic manuals such as the ICD-11 or the DSM-5, upon which most psychologists rely (Raskin et al., 2022). It remains however, that some children systematically avoid demands and parents and those identifying with the profile feel that the EDA label is functional (Egan et al., 2020), in helping individuals make sense of their lives (Thompson, 2019). Difficulties with school (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2016), as well as high levels of family stress (Ozsivadjian, 2020) including parental blame (Doyle and Kenny, 2023) have been documented.

The lack of validation of the construct of EDA means an absence of clinical guidance about how to support children. The existing guidance remains mostly neutral, documenting the divergent views which exist concerning EDA, and largely does not address useful practices. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011) autism diagnostic guidelines and those from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2020), the Australia Autism CRC (2018b) and the British Psychological Society (2021) all reference the absence of EDA from diagnostic manuals and a lack of consensus on the construct. Significant interest in EDA was identified by both NICE in their 2020 review (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020) and the Autism CRC (2018a) public consultation, however associated guidance documents remain succinct on the topic. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013) also produced a document specific to support strategies for autistic individuals, but it does not reference avoidance of demands or how to support experience of such. Both the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011) and RCP guidance note managing the presentation as part of formulation and planning for the individual, whilst the RCP version suggest avoiding confrontation but otherwise, do not specify what may be helpful, aside from highlighting that avoidance of demands is a common human feature. Interestingly, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011) guidelines associate EDA with oppositional defiance disorder which may emphasise a role of volition in avoiding demands, inconsistent with viewing avoidance as a stress response. As well as publishing guidelines regarding assessing for PDA (PDA Society, 2022), the PDA specific charity have written at large regarding helpful practices for individuals experiencing demand avoidance, with authors highlighting their annual conferences are oversubscribed (Trundle et al., 2017). It remains however that empirically based evidence as to what is helpful for this group is lacking.

The research that does exist indicates that behaviourist-based practices are unhelpful in EDA (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2018), and may even be counterproductive (Duncan et al., 2011). This is of interest, as some practices traditionally used in supporting autistic individuals are derived from behaviourism, e.g., applied behaviour analysis (Lovaas, 1987). The use of unhelpful practices in schools, particularly those using a traditional autism lens may explain why children experience such difficulty and why the EDA profile has garnered so much parent attention. Thoseractices identified by researchers and clinicians as helpful in EDA include increasing certainty (Stuart et al., 2020) or developing ways to manage uncertainty, increasing demand tolerance, teaching alternative skills (Grahame et al., 2020), masking demands, promoting interests, offering choice (Duncan et al., 2011), using agreed upon rewards, using low demand, avoiding reinforcing avoidance, using low arousal, picking battles, using indirect language, focusing on non-verbal cues, managing adult expectations (Eaton and Weaver, 2020), avoiding head-on confrontation (Fidler and Christie, 2015), using variety, mystery and novelty, complex language, anxiety reduction strategies, role-play, visuals to depersonalise demands, providing a safe space, building self-awareness and self-esteem and having a keyworker system who is calm and where the relationship is based on trust, intuition, flexibility and adaptability (Christie, 2007). Fidler (2019) notes an emphasis on whole-school wellbeing is important. O’Nions and Eaton (2020) identified that in the specific context of completing an assessment with a child, psychologists benefit from being adaptable, following the child’s lead, inviting the child to help, and including humour and choice. Interestingly, critics argue that such helpful practices are not confined to EDA, but instead can be understand as good practice based on current understanding of how to support neurodivergent individuals (Woods, 2019).

Regarding professional practices that are helpful for families, authors highlight collaboration (Moh and Magiati, 2012) availability, empathy, openness to a variety of perspectives (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2018) and ability to assess dynamics of relationships (Green et al., 2018). Despite children experiencing EDA being involved with many professionals, the most common group of professionals they are involved with is educational psychologists (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2016; Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2018). However, clinical psychologists are also involved in working with children with EDA, showing support is needed outside of school (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2018).

Even though children who systematically avoid demands are in receipt of psychological support, little literature appears to exist that explored psychologists’ perspectives or experiences of working with children with demand avoidance. Doyle and Kenny (2023) found that psychologists working with this population were keen to access training and, specifically, to learn more about diagnostic practices. Authors have highlighted gaps in knowledge answerable by future research, including how to improve wellbeing for children experiencing EDA (Eaton and Weaver, 2020), whether identification of EDA is helpful (Truman et al., 2021), how demands might be made more tolerable (O’Nions and Eaton, 2020), the developmental trajectory of EDA and helpful practices (Kildahl et al., 2021; Mols and Danckaerts, 2021). It seems that those psychologists working closely with children, schools and families may to contribute to answering these questions.

This study takes a constructivist approach in exploring psychologists’ accounts of demand avoidance and extreme demand avoidance in children. Examining EDA provides a rare opportunity to explore how psychological constructs evolve from their origin, giving a voice to psychologists who play a key role in supporting children and who are well placed to advance our understanding of psychological phenomena. Acknowledging that the definition of EDA is contested in the literature, this research holds the a priori standpoint that the construct of EDA is open to investigation. Similarly, the literature is unclear on whether EDA is confined to autism (Egan et al., 2020), thus, this study does not require psychologists to be working with autistic children. The present study aimed to address the following research objectives.

1. To describe how psychologists conceptualise, experience and approach demand avoidance in children. This objective informs us about how psychologists have understood and approached such presentations in the absence of clear guidance.

2. To determine if any of the psychologists’ accounts of demand avoidance were conceptualised as EDA. This objective helps us to better understand the utility of the construct of EDA.

3. To explore if there are parallels between psychologists’ accounts of extreme demand avoidance and the construct of EDA described in the literature. This objective examines whether psychologists’ accounts of extreme demand avoidance align with what is described as EDA in the literature as per Newson et al. (2003).

These objectives were addressed using a small-scale qualitative study of practicing psychologists from the United Kingdom, Australia, and the Republic of Ireland.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

A sample size of 10–15 psychologists working with children and adolescents was anticipated to comply with pragmatic time constraints, psychologists’ likely interest in being interviewed about the niche area of demand avoidance, to create a diversity of perspectives, and recognising the depth of data likely generated by psychologists (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Sample size is acknowledged as a single factor when using reflexive TA in a constructivist paradigm. Data quality was monitored during transcription and following the 12th interview, it was deemed there were sufficient data to tell a complex and rich story (Sim et al., 2018).

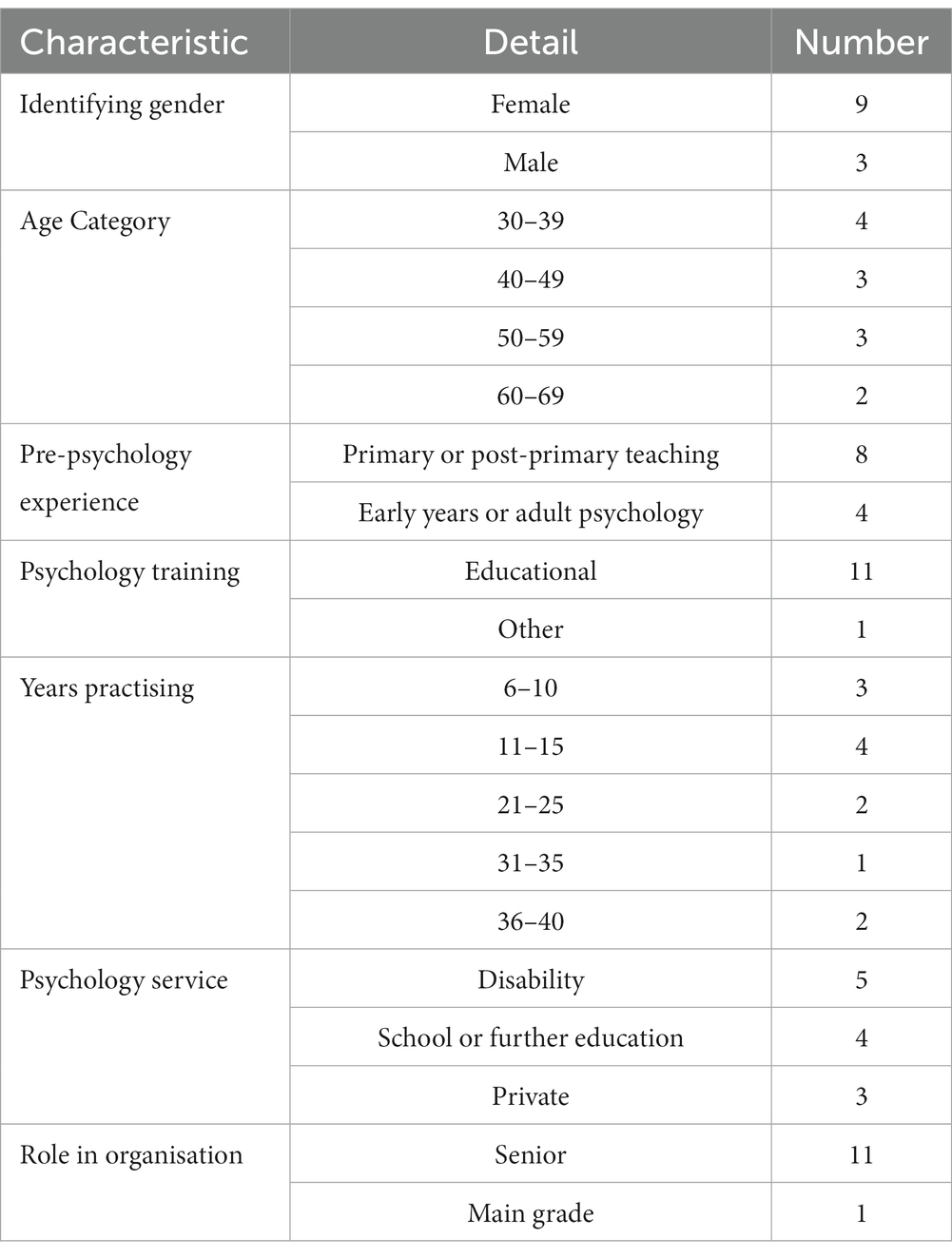

Table 2 gives a summary of participant details grouped to ensure anonymity. Most psychologists identified as female (n = 9) and a diversity of ages was achieved. Most psychologists (n = 8) had been teachers before becoming a psychologist, and others worked in early years or psychology services. Most psychologists had been trained as educational psychologists (n = 11). Of the psychologists practising in Ireland, most were working in one geographical location within Ireland. Three psychologists were employed by the National Educational Psychology Service (NEPS), one by the Education and Training Boards, five by the Health Service Executive (HSE) Disability service and, one was in a private service. One practitioner from Australia and one from the United Kingdom also practised privately. All participants had more than 6 years in practice (n = 12) and most (n = 11) described their role as senior.

Exemption from a full ethical review was obtained from the UCD Human Research Ethics Committee on the basis of the research being on standard professional practice, and research approval was granted from the Research Advisory Committee of NEPS in June 2022. Psychologists were recruited via a snowball approach using word of mouth, social media (Twitter), a Whatsapp networking group of practicing psychologist across Ireland, and NEPS channels, where a manager sent an email to a specific geographical area of Ireland. A leading PDA specific organisation, the PDA Society shared the call for participants on Twitter. An information sheet detailing the nature of the research was made available online. All participants were informed that their anonymity would be respected, and there would be no identifiers (including by service) in the write-up. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study up to 2 weeks post-interview.

Participants completed informed consent and submitted their contact details and demographic information (self-identified gender, level of professional experience, age category, and occupational status) via a Google form. A pilot test of the semi-structured interview schedule was conducted with a practicing psychologist in July 2022. The 12 interviews were conducted by the primary investigator via Zoom between July and November 2022. Each interview lasted between 45 and 70 min. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed into Microsoft Word, de-identified and stored on a secure, encrypted laptop. Once transcribed, the audio files were destroyed.

Semi-structured interviews

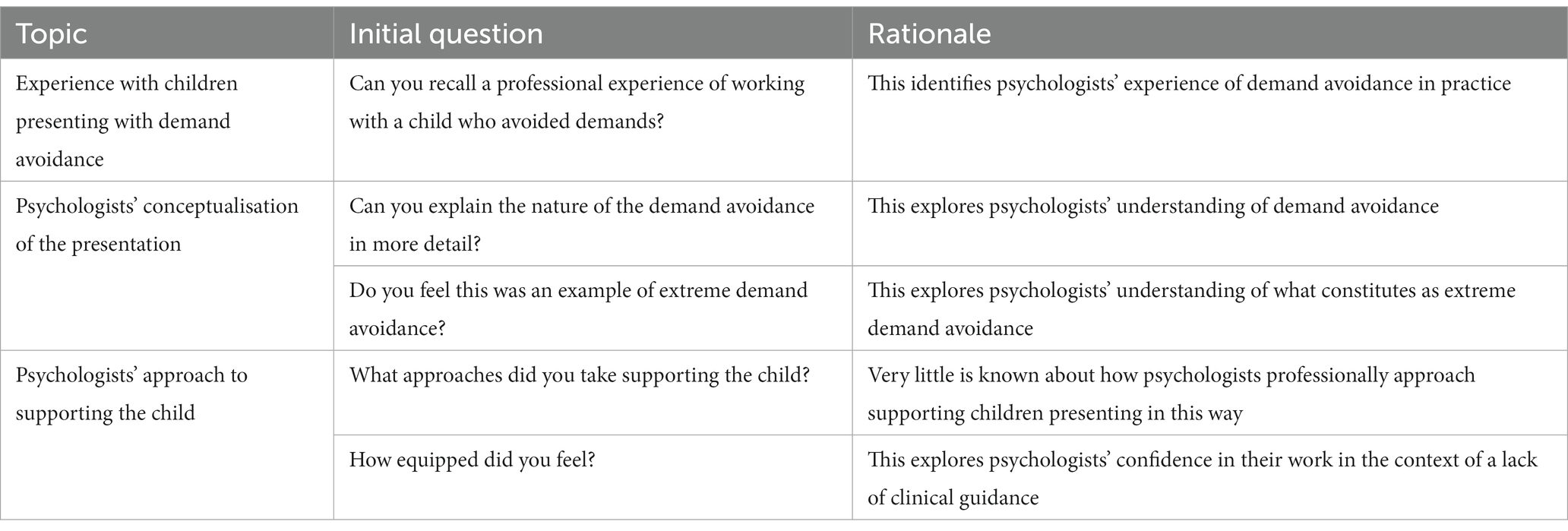

The semi-structured interview schedule was designed based on the research questions and was adjusted with feedback from psychology experts and from the pilot study. Table 3 describes the interview schedule, detailing each question with the associated underlying topic and rationale. The interview schedule was designed using three topics incorporating five main questions and associated probes: (a) psychologists’ experience with children presenting with demand avoidance, (b) psychologists’ conceptualisation of the presentation and whether the case represented extreme demand avoidance, and (c) psychologists’ approach to supporting the child. There was a degree of flexibility within each interview, in that the order of questions and the time spent exploring each topic were determined by participants’ contributions, allowing the researcher to explore issues raised by participants, in line with the constructivist approach. Initial questions were deliberately broad so as not to constrain responses, for example, in the approaches section, participants were asked “What approaches did you draw on in supporting the child?” followed by probes to gain more information “can you explain why you chose those approaches?” and to funnel to specific topics raised by the participant, e.g., “How was the use of novelty new for the child’s carers?”

Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented regarding participants’ self-identified gender, number of years practicing, role in organisation, and age category. The semi-structured interviews were analysed using the six-phase reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) approach as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2019) for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns with a dataset. Though sequential phases are identified, the RTA process is recursive and iterative, requiring the researcher to move back and forth in a flexible way, as necessary. RTA was chosen as it is flexible in approach, and views researcher subjectivity as a resource, whilst staying close to participants’ own accounts which fits with the constructivist paradigm informing this study. Identifying meaning in participants’ responses in RTA is a combination of the researcher’s judgements of which data answer the research question, and the importance ascribed to experiences by the participants. While recurrence of meaning is noted, it is not the focus. The researchers took a critical orientation to the data, acknowledging that though meaning was created in the interactions between researcher and participants, and is influenced by researcher subjectivity, participants’ accounts of their personal reality remain a valuable means of understanding their experiences.

Data were transcribed by the first author into Microsoft Word documents and NVivo12 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) was utilised to code and organise data. Transcription was viewed as a useful part of the familiarisation phase, which also included reviewing each transcription and noting of items of interest, conflicts, initial ideas, and assumptions (Braun and Clarke, 2019). The research questions formed the criteria for a firstly deductive approach to coding material, where the researcher coded the data into three key areas of experience, conceptualisation, and approach. The predominate approach for the remainder of the process was inductive, and prioritised participant meaning, as all interview data were coded multiple times across different key areas to ensure nothing was missed. Note-taking was used throughout to ensure consistency of approach, and to track the evolution of codes through various iterations. A comprehensive approach was taken, meaning many finer grain codes were created which sought to carry sufficient detail to stand alone from the data (Braun et al., 2016). A mixture of semantic and latent coding was used, in many cases both, semantic codes reflected the meaning communicated by the participant and latent codes reflected the interpretation of the analyst.

Themes were generated from initial codes where the focus was then on ensuring meaning across the entire data set was reflected as well as how meaning is interpreted to answer the research questions. Initial codes and themes (phases two and three) were reviewed by the second author and the corresponding discussion led to further reflection on potential themes in phase four. Discussion did not seek to achieve consensus but was used as a platform to check assumptions. A record was kept of several iterations involving codes, subthemes and themes being removed, revised, and restructured. Original transcripts were regularly referred to in checking the broader coding context. A revised thematic map was developed, and some further adjustments were made, including naming of themes and subthemes. In preparing for phase six, both authors considered the order in which to report themes. Data were contextualised in the results section as advocated for by Clarke and Braun (2013).

Results

Child details

During interview, psychologists were asked to recall their experiences with one child presenting with demand avoidance. Children in psychologists’ accounts were typically aged 5 to 9 years (n = 6) or 12 to 14 years (n = 6), with eight boys and four girls. Most children were previously identified as neurodivergent (n = 10), with nine identified as autistic. Whilst accessing the psychologist, four children were also involved with other allied health professionals, typically psychiatry (n = 4). Eight children had experienced or were contemplating an educational placement move, one had experienced school exclusion. Three were currently in mainstream education, four in a “special” setting, four in alternative education or were not accessing any formal education. The following were perceived to be strengths of the children described: average cognitive ability (n = 6), involved in local community (n = 3), seeking social connections (n = 5), well-developed communication skills (n = 4), and coping with academic learning (n = 2).

Thematic analysis

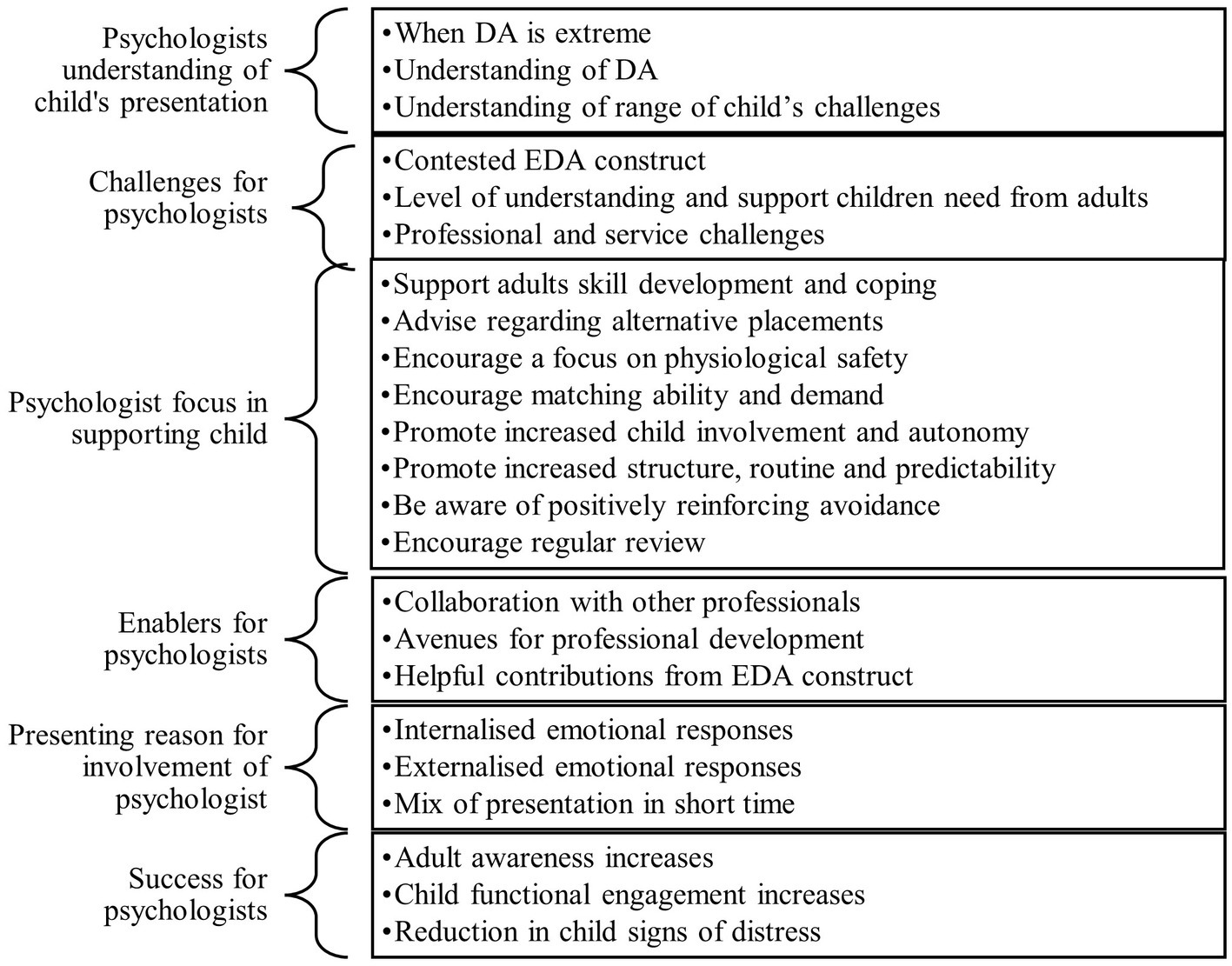

Thematic analysis yielded six salient themes emerging from subthemes. The corpus of themes summarised psychologists’ experiences, conceptualisation, and approach in working with children with demand avoidance (see Figure 1). The themes and subthemes are described in this section, supported by relevant excerpts from the interviews.

Psychologists’ understanding of child’s presentation

This theme relates to participants’ accounts of reasons given for psychologists to become involved with children, often known as the referral question. Psychologists noted that reasons given by referrers were often removed from a full understanding of the child’s experience.

References were made to demand avoidance which presented as externalised emotional responses directed toward self, others, or material objects. Some psychologists used broad-stroke descriptions, such as “physical outbursts,” perhaps owing to psychologists receiving this information second-hand. One psychologist (female) was more explicit having witnessed a response first-hand, “he lay on the floor, rolled himself up in the rug and started kicking to the point where I was concerned because the walls were glass.” One psychologist (female) recalled the caring adults felt “targeted” when children “make comments, about weight, accent and skin colour.”

Disengagement as a feature of demand avoidance was a likely indicator for psychological involvement, viewed as an internalised emotional response. One psychologist (female) feared that cases of internalising demand avoidance were not reaching psychologists as much as she might expect. Each child described was experiencing daily demand avoidance, however, the most common reason for involvement was individuals failing to leave the house. Another psychologist (female) noted, “he spent a lot of the previous 4 years in his bedroom.”

The idea that individuals’ regulation went “from 0 to 100” was another common referral question. Whilst few psychologists had witnessed this themselves, one (female) who had, recalled the child “screeching, but the next minute switching into high-quality conversation.”

Challenges for psychologists

This theme describes three main challenges for psychologists which include, an ill-defined construct of EDA, working with varying levels of understanding of the child amongst adults and additional professionals, and service boundaries which require management.

Participants acknowledge the contested EDA construct has implications for professional understanding, practice, and relationships. One psychologist (female) recalled a frustrating conversation with a colleague who questioned, “aren’t they all demand avoidant by adolescence?.” One psychologist (female) noted, “I feel nervous, because it’s not in the DSM, yet something has to exist to reach the threshold.” Others questioned the value that EDA would add, with one psychologist (male) describing a risk of, “getting caught up in the high grass, instead of focusing on the actual practical implications,” whilst another psychologist (female) added, “what matters is getting this person out of their bedroom!.” Psychologists expressed frustration that although a needs-based rather than a diagnosis-based focus exists in some educational systems, a focus on diagnostics remains, “on the one hand you do not need a diagnosis to get support along the continuum, but, if you have requested special treatment, then you need a reason” (female psychologist).

One expressed concern that with growing awareness, over-identification of the profile could occur. Many participants disliked the language used in the construct title and definition, rejecting the term pathological (a synonym for extreme in the construct title), based on the medical model of disability. One participant’s experience was that the construct encouraged them to focus solely on the language of demands and avoided generating a fuller understanding. The term manipulative was also problematic because this was not felt to accurately reflect the child’s experience.

Psychologists describe a key challenge relates to families and schools’ level of understanding of the child’s experience. Many acknowledge the influence of parents’ experience of being parented. One psychologist (female) appreciated her recommendations were novel for parents, “it was just so unusual initially…encouraging her 14-year-olds to do these things.” Another psychologist (female) noted parents’ commitment to traditional education pathways impacts upon progress, “she pushed him beyond what he could reasonably achieve.” One psychologist (female) felt the impact of working with parents who are neurodivergent made aligning goals difficult, “the parent had challenges with communication and executive functioning, making it very difficult.”

At school, social and learning expectations, the number of adults and other children involved were also reported as barriers. Psychologists explained that cultural norms were sometimes mismatched with the needs of the child. For example, in relation to a common school rule in the UK and Ireland regarding uniform, one psychologist (female) found a uniform rule exasperating, “Why do you have to wear a skirt? Just be flexible!.” Participants described that many of the children they met had first been identified as autistic and were supported with traditional autism approaches which might not be useful, resulting in difficult experiences. Parent and school staff understanding could be mismatched, often resulting in blaming parents. For example, one parent a psychologist (female) worked with, was told she was “a ridiculous mother seeing problems where there were none.” This lack of consensus in how to support children with complex needs contributes to adult exhaustion, which, in turn causes difficulty for psychologists, as it reduces adults’ capacity to build on psychologists’ work.

The psychologists also encountered challenges with several professional issues. Psychologists described a lack of control over many factors within systems in which the children existed. Some psychologists found it difficult when parent agency meant a poorer perceived outcome for the child, for example regarding school choice, “ultimately, I cannot make that call, but it was very difficult holding that because I am worried about the long-term implications” (female psychologist). Not being privy to relevant contextual factors was also acknowledged: “psychologists operate in an imperfect process, we are reliant on information relayed to us but that’s subject to the perception of the narrator” (female psychologist). A further challenge was delay in accessing the latest research, which caused guilt for some psychologists, “it’s tough when you see this young person in distress, and you think, we should have known what was going on” (female psychologist). Service boundaries involving time was also seen as a challenge, with many noting this type of work is time consuming. Others noted being restricted in who they could work with, e.g., not being allowed to work directly with parents.

Enablers for psychologists

A key sense of togetherness was communicated in relation to psychologists collaborating with others to bring change for the children. Shared experience, supervision, and expertise from other disciplines including occupational therapy, speech and language therapy and psychiatry, was reported as being valuable. Having follow up from professionals from other services was useful, owing to services boundaries. Psychologists referred to a need for both formal and informal fora, noting, “you need to be sitting in a room, here’s a case study, this is what transpired, these are the approaches” (male psychologist). Learning alongside colleagues was seen as important, “we trained together, so we implemented our learning together” (female psychologist), another described team meetings which included reflecting on “what we screw up and what we get right” (female psychologist). Whilst one psychologist noted relying heavily on academic research, another acknowledged a time barrier, “I do not have the luxury to be looking through research, I’d love someone to point me in the direction of something practical” (female psychologist). Twitter was noted as an efficient method to connect with the autistic community.

Some psychologists noted the approaches associated with the EDA construct had been supportive. One stated “I still draw on the information for when you need an alternative approach” (female psychologist), noting the construct can offer an explanation as to why more traditional strategies have failed. Another psychologist described using EDA approaches daily. Psychologists welcomed the addition of the current research, hoping that it would yield practical implications.

Psychologists’ understanding of the child’s presentation

This theme illustrates the ways in which psychologists conceptualised the child’s presentation. This theme is connected to the other theme of psychologists’ reason for involvement, as it describes how psychologists conceptualise demand avoidance and other influencing factors. In addition, this theme includes data pertaining to psychologists’ descriptions of when demand avoidance is considered extreme.

Psychologists mainly attribute demand avoidance to autism or ADHD and anxiety at “exceedingly high” (female psychologist) levels resulting in autonomic bodily responses. Experience of autistic trauma, inertia, intolerance of uncertainty, burnout, or a mismatch between autistic and neurotypical understanding, were all named as influential. One psychologist noted that “children who are autistic have been traumatised numerous times before there is an understanding of where their autonomic nervous system is at” (female). Another explained, “demand avoidance might lead backwards to something that happened which was frightening, and nobody explained it” (female). Whilst some psychologists felt that demand avoidance was natural and adaptive, others described it as resulting from a “complex interweaving of family stuff” (male psychologist) or described it as involving many factors, a “curious mix” (female psychologist).

Such complexity was reflected in the range of challenges psychologists described children facing at biological, cognitive, behavioural, affective, and family/school/community levels, with the latter two appearing most influential in contributing to the child’s presentation based on psychologists’ accounts. Affective factors included negative experiences of expectations (of time, social encounters and abilities, health, and school), feeling a lack of physiological safety owing to not being seen or heard “he was at that top end of the fight or flight, in a really heightened state of anxiety all the time” (female psychologist), being punished for things outside of their control, and not having trusted connections, resulting in emotional responses communicated in a different way.

Family, school, and community factors noted by psychologists as challenges for children included relationship dynamics, as well as cultural norms about how people experience the world. One psychologist (female) described family expectations, they had another child, and they were applying the same rules to her, but we said “look, this is different”. Ruptures across key relationships was also reported as being common.

Psychologists described demand avoidance as extreme when it was evident from early childhood, occurred in another neurodivergence, included externalising, and internalising emotional responses precipitating harm to others, linked to strong interests in individuals, appeared as the child having a “definite view” (male psychologist), evidenced a mismatch between age expectations and the child’s tolerance, and impacted on the child doing what they needed or wanted to do.

Psychologists’ focus in supporting the child

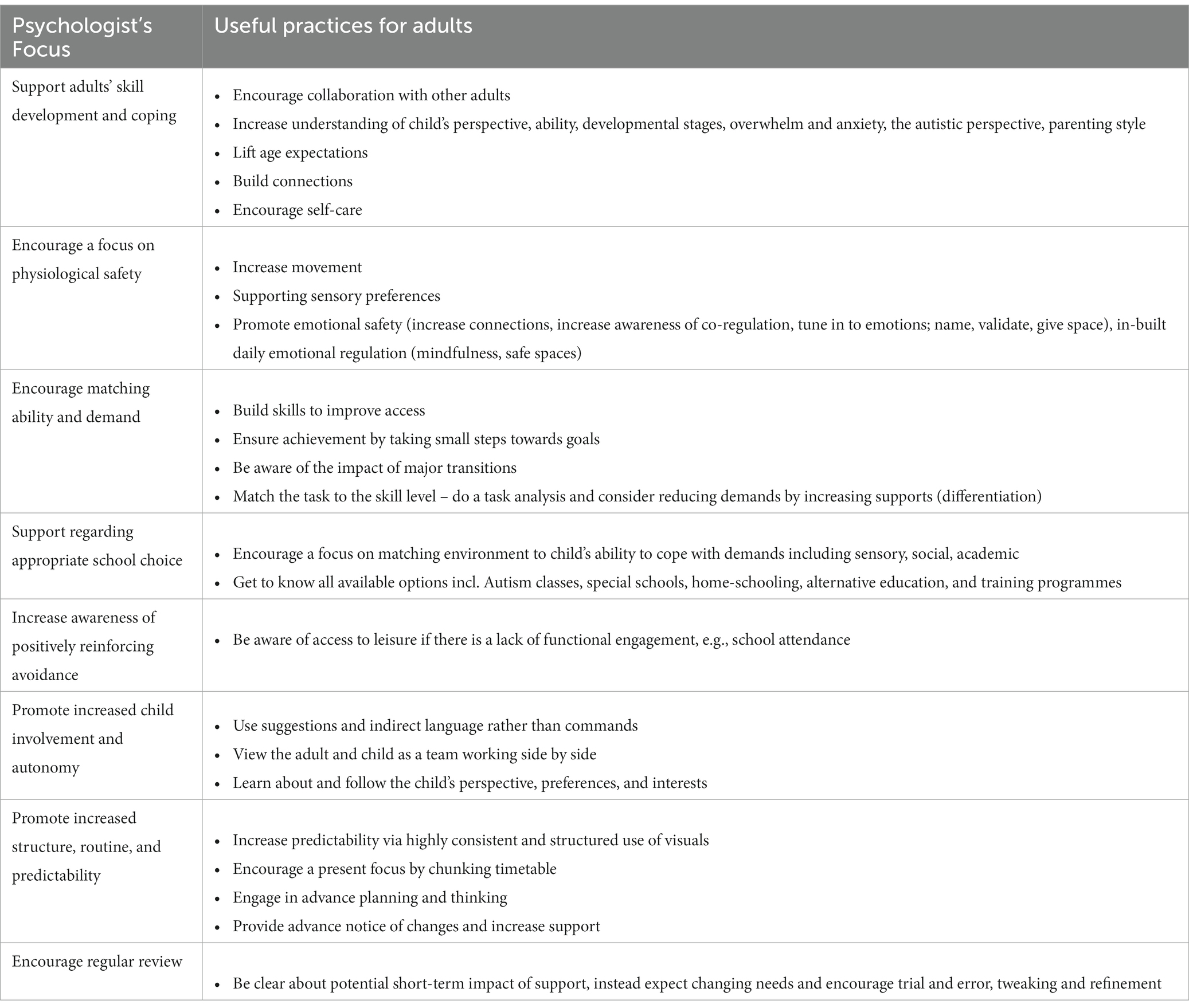

This theme describes psychologists’ focus in supporting the children they described (See Table 4) via improving adult practices. The focus on working with the adults involved with the child rather than the child themself highlights the truly systemic nature of the psychologists’ role. Psychologists empower adults by validating their experience, bringing awareness of assumptions, building understanding, and supporting them in tuning in to individual need, whilst considering environmental factors. “Taking a step back” (female psychologist) from culturally influenced expectations was referenced. “Tuning in” (female psychologist) often involved giving the child a voice. One psychologist (female) recalled thinking “you [parents] might know a lot about autism, you might know a lot about ADHD, and you obviously know loads about [medical condition] but you do not know what it’s like to be this girl.” Openness to regularly adjusting the type of support is deemed important, with a psychologist (female) noting, “I was under no illusions it would be long lasting.” Supporting children presenting in this way was deemed to be “quite skilled” work by one psychologist who noted, “I think it is down to subtlety in approach and it is very, very individualised” (male psychologist).

Success for psychologists

This theme addresses psychologists’ descriptions of success in their involvement with children. Psychologists communicated that indicators of success may be small. They noted that adults’ understanding increasing is a key feature, with one psychologist (female) describing her involvement as having “shifted the parents thinking about her as defiant, to trying to reduce her stress levels.” Another psychologist (female) noted a parent now “takes steps back in order to go forward.” Others described increased self-awareness for parents as important in achieving co-regulation, “she [mother] was the most regulated she had been ever, and he [child] completely opened up in a way he’d never done before” (female psychologist).

Psychologists also described features of successful change for children, including relating to other people, seeking others, tolerating imposed boundaries, or going to necessary places. In relation to attending therapy appointments, one psychologist (female) noted “she tolerated me, and she came back,” and another (female) spoke of increasing ability to tolerate school, “attendance went from 10 min three times a week, to 90 min every day, massive progress.” A reduction in signs of child distress was also seen as important.

Discussion

This research aimed to explore practicing psychologists’ accounts of demand avoidance in children whom they play a large role in supporting (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2018). The research sought to explore how psychologists experience, conceptualise and approach demand avoidance in children, and, in cases where psychologists conceptualised the demand avoidance to be extreme, how their descriptions mapped on to the construct of PDA as originally described by Newson et al. (2003). Transcripts of semi-structured interviews with 12 psychologists working with children were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2019). The six themes created provide a rich account of how this cohort experiences, conceptualises, and approaches demand avoidance in children. Psychologists appeared to experience demand avoidance and EDA as a feature of their work. Amidst a lack of clear clinical guidance, psychologists reported using a range of practices, overlapping many approaches, in supporting children. The focus was mostly indirect, emphasising the adults around the child. The features of demand avoidance described by psychologists as being extreme had some parallels with those features of EDA described by Newson but also had key differences.

Psychologists’ experiences of demand avoidance in children

Children in need of support

Firstly, psychologists’ descriptions of demand avoidance in children emphasised their need for support, regardless of their orientation towards the EDA construct (Woods, 2020). Children’s need to avoid demands was understood as arising owing to the differences between neurotypical individuals and neurodivergent individuals, which gives rise to complex interactions. Consistent with Brede et al. (2017) and Doyle and Kenny (2023), challenges were associated with home and school evidenced by the high prevalence of school moves and poor health experienced by children and parents. Such a finding indicates difficulty with traditional schooling, which is likely to have led to negative experiences for families and schools. Duncan et al. (2011) also refer to the impact of late identification of such a profile, noting that less helpful approaches may have been used where a full understanding was lacking. Early support gives children the opportunity to achieve success.

Common challenges and enablers

Despite controversy surrounding EDA, psychologists did not experience supporting these children as particularly different to other neurologically divergent groups. One common experience was that of tensions amongst different stakeholders and different levels of understanding. Whilst the department of education model of resource allocation (Department of Education and Science, 2017) suggests schools can cater to need without diagnosis, psychologists communicated that schools still find it difficult to deviate from the norm. Doyle and Kenny (2023) also queries the utility of needs-based models where very novel approaches are needed, such as in EDA. Insight from young autistic people who had been excluded from school similarly emphasised the lack of understanding of their needs as central to their failed school placements. The young people also cited difficulty in understanding how all pupils finding school challenging could successfully tolerate being placed in the one classroom. Accounts in the current study also described tensions in relation to school placement, where psychologists might not see a placement as a good fit for the child. The new progressing disability service model in children’s disability teams in Ireland also recommends parent prioritisation of goals (Bradley et al., 2020), which may present similar difficulties for supporting clinicians.

Consistent with previous research, both within the demand avoidance literature and more broadly within professional psychology literature, certain factors were seen as enabling success for psychologists. Psychologists valued learning from peers and from research disseminated efficiently, as has been found elsewhere (Law and Woods, 2018; Hoyne and Cunningham, 2019) as well as through collaboration with other disciplines (Atkinson et al., 2013; Doyle and Kenny, 2023). Psychologists in the current study also valued access to neurodivergent perspectives. Space and time for learning opportunities is likely a challenge in organisations, but its value cannot be understated. Twitter was acknowledged in the current study as a key avenue to engaging with neurodivergent individuals. Since NEPS and primary care psychology are single discipline services in Ireland, it follows that systems may need to be in place to facilitate multidisciplinary working.

Psychologists’ approach to demand avoidance in children

Range of (neurodiverse affirmative) approaches

Despite a lack of guidance about practices for supporting children with demand avoidance, many psychologists in the current study approached demand avoidance in a similar way to other psychological difficulties, by focusing on the child’s underlying needs (Astle et al., 2022), and by building understanding for all involved (Milton, 2018). Psychologists emphasised the individualised nature of this work which draws on a strengths-based approach to diversity, consistent with previous findings (Wilding and Griffey, 2015; Doyle and Kenny, 2023). Clinical guidance produced by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013) emphasises the individual nature of support in the case of autistic children and the PDA Society (2022) in the case of autistic children with an EDA profile. In supporting children, psychologists drew upon a range of approaches including relational, with a focus on adult self-regulation (Cunningham, 2022), anxiety-based, as advocated for by White et al. (2022) and, neurodiversity-informed, as suggested by autistic children themselves (Goodall, 2018). EDA adults (Johnson and Saunderson, 2023) and autistic young people experiencing demand avoidance (Brede et al., 2017) also referenced the role of the relationship with trusted adults around them in emotional regulation and the role of uncertainty and change in anxiety. Approaches associated with EDA were also in use, argued by Woods (2019) to represent good practice in supporting neurodivergent children. Behavourist methods described in other studies (e.g., Law and Woods, 2018) were not often mentioned in the current study, perhaps owing to a move towards neurodiverse affirmative approaches identified by psychologists as becoming increasingly relevant to their work. Using a range of approaches makes sense for psychologists as, regardless of their psychological challenges, children’s minds and histories are diverse (Allsopp et al., 2019).

Indirect work

In approaching demand avoidance in children indirectly, increasing adult understanding and managing expectations were seen by the psychologists as being important, in line with previous findings (Law and Woods, 2018; Hoyne and Cunningham, 2019; Eaton and Weaver, 2020) and clinical guidance (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013; PDA Society, 2022). Christie’s (2007) guidelines placed strong emphasis on the significant support needs of the adults working around a child presenting as demand avoidant. In addressing adults’ own anxiety, psychologists encouraged them to value diversity and to move away from a within-child deficit model influenced by psychocentrism (Gruson-Wood, 2016) and developmentalism (Gabriel, 2021), common in education, towards viewing difficulties as occurring relationally.

Developmentalism results in demand avoidance being misinterpreted as pathological, as it deviates from what is expected for children according to age (Moore, 2020). Adults’ experience of being parented and of education were also seen as influencing their expectations, in line with Kerr and Capaldi (2019) and Hornby and Blackwell (2018). Indirect work with parents and teachers means the quality of the relationship matters (Hoyne and Cunningham, 2019). In the context of demand avoidance, parents value good listening, care, no judgement, and openness (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2018). The Department of Education model for resource allocation (Department of Education and Science, 2007) and the Progressing Disability Service (PDS) model for children’s teams (Bradley et al., 2020) in Ireland both rely on empowering the adults in a child’s life.

Psychologists also described encouraging adults to regularly review their practice, noting that this may be difficult as needs change and develop over time. Previous authors have suggested continuity in access to psychologists might be helpful (Gore Langton and Frederickson, 2018; Doyle and Kenny, 2023), with support increasing and decreasing as needed (Green et al., 2022). In theory, both in children’s disability teams and in NEPS, children can achieve recurring support, although this is of course dependent on the limited availability of psychologists.

Psychologists conceptualisation of demand avoidance in children

Demand avoidance in autism

Despite its original categorisation as pathological demand avoidance, and the lack of consensus regarding demand avoidance as occurring within autism, psychologists have typically observed demand avoidance in autistic individuals. Demand avoidance as occurring solely within autism has been strongly campaigned for (e.g., PDA Society UK). A strong recognition factor described by families upon receipt of the diagnosis and approaches described as differing from those used for other autistic people are being cited as evidence for the existence of a sub-type. Eaton and Weaver (2020) highlight the central feature of EDA appears to be anxiety, which is itself not a diagnostic feature of autism. Woods (2022a,b,c) suggests that there are power differences at play, with the potential for the autism industry to create an EDA product that would allow private practitioners to gain financially by offering a contested diagnosis. High levels of support for EDA may be therefore explained by social identity theory which describes disabled people needing to create in-groups to protect against ableism (Bogart and Dunn, 2019). In the current study, psychologists’ acceptance of demand avoidance as occurring mainly in autism shows the power of mass interest and suggests that care must be taken regarding the social influence on constructs of disability (Woods, 2022a). Woods (2023, p. 48) describes how a “premature communities of practice” can form as a result of campaigning on social media, in this case relating to EDA as occurring soley within autism.

Taking a broad perspective

Psychologists viewed children’s presentations broadly, as complex, and as occurring because of a range of factors, and not solely associated with demand avoidance. Features included high levels of distress, and documented impact on health of children and adults, replicating findings of Brede et al. (2017), Gore Langton and Frederickson (2018), and Doyle and Kenny (2023). In line with previous findings (e.g., Doyle and Kenny, 2023), psychologists attributed differences to known features of neurodivergent individuals. Some psychologists used the language of neuroscience, describing autonomic bodily stress responses which happen in the context of imposed demands. This may also align with the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2020) who highlight avoidance of demands is a common feature of humans, in a brief note on PDA in their guidance on the psychiatric support of autistic adults. Adults experiencing EDA in the study by Johnson and Saunderson (2023) also reference the role of the autonomic nervous system in explaining their bodily responses, though some discussed being motivated by stress which perhaps suggests a role of volition. Stress response explanations are consistent with models described by Green et al. (2018) and Woods (2022b) which take the view that stress is transactional with the environment and occurs when demands exceed coping ability. Transactional models have implications for environments such as homes and schools in which children exist. Given the high level of stress exhibited by children in the current study and previous research, it seems that demands placed on some children do not appear to match their coping ability.

Extreme demand avoidance as a construct

Parallels with Newson

All psychologists in this study described the children they worked with as experiencing extreme levels of demand avoidance. Much of what is known about demand avoidance is based on Newson et al.’s (2003) early criteria for EDA. Parallels exist between Newson’s criteria and the criteria described by the psychologists in the current study, but key differences also emerged. Importantly, social manipulation was not discussed by the psychologists, although it is a central feature of Newson’s descriptions. In addition, the psychologists described the impact on what children want or need to do as being important, which showed respect for the individual, rejecting a developmentalist perspective (Moore, 2020). Contrastingly, Newson et al. (2003) focus on children not carrying out actions as desired by adults. In addition, Newson does not refer to the transactional context where demands exceed coping ability. Whilst Newson included developmental features, e.g., language delays, other authors had removed them (O’Nions et al., 2016) and one psychologist saw emergence in early development as important in delineating EDA from demand avoidance. Other features described by Newson which achieved little or no coverage by psychologists in this study include passive early history, comfort in role play and, soft neurological signs.

Utility of the construct

Though the psychologists in the current study reported using a range of approaches to work with children with demand avoidance, representing good practice for neurodivergent individuals (Woods, 2019), most rejected the medicalised language and utility of the EDA construct. Rejection of medicalised language is reflected in the variety of terminology available to describe EDA and has been identified previously amongst psychologists (Raskin et al., 2022). Few psychologsists were open to including the profile as part of an autism identification and had previously done, consistent with suggestions by the PDA Society UK in their 2022 guidance. Most psychologists focused on children’s underlying needs, which may be in line with a transdiagnostic approach as described by Astle et al. (2022). This approach recognises that some characteristics in children’s profiles occur outside of categories, giving the example of autism and anxiety. A transdiagnostic model focuses on characteristics, over diagnostic label, and is in line with Doyle and Kenny (2023) who suggest noting the presentation of anxiety and demand avoidance in formulation. Guidelines from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2020) relating to autistic adults also advocate for managing underlying factors such as severe anxiety. Even advocates of PDA question the utility of diagnostic classifications and note that different profiles can present with similar features (Duncan et al., 2011). In a foreword to a book from the perspective of an 11-year-old girl with PDA written by Duncan et al. (2011), a leading clinical psychologist in the field, Judy Gould, notes that its content is likely to be of use to individuals “not conforming to conventional social rules, who are oppositional, or just different” (Fidler and Christie, 2015, p. 10). Rather than adhere strictly to a categorical approach, a transdiagnostic model may be of value as it allows for early identification of strengths and vulnerability, potentially reducing inequality in accessing support, as children do not have to wait for characteristics to be sufficiently problematic to reach a threshold.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this research, meaning that caution must be used when interpreting findings. Firstly, because the research set out to test the EDA contrast, it purposefully did not work with a precise definition of what is meant by demand avoidance. The implication of this means we cannot say if the practices pertain specifically to demand avoidance, or if they are useful practices for children in general or in a specific category. Similarly, we cannot say whether the practices psychologists identify as useful in supporting children will work at higher or lower levels of demand avoidance than what is described. A detailed account of children’s profiles or experiences was not possible meaning any possible intersectionality is not addressed. Information such as age of child is missing which may be relevant to ability to learn coping strategies as alluded to by Johnson and Saunderson (2023).

In addition, by its design, the study relied solely on the views of psychologists. This is particularly relevant when considering practices described to be useful or the indicators of success, as psychologists’ perceptions may differ from that of teachers, parents, and children whose perspectives would give the most reliable account. Psychologists’ views are likely highly influenced by the inherent privilege associated with their role (Stoudt et al., 2012). Since the neurodiversity paradigm has shown so clearly in its emphasis on the subjective voice, means of achieving feedback from teachers, children and families in relation to the usefulness of psychologists’ support would be worthwhile.

In relation to the limitations associated with the recruitment method, though Twitter and a Whatsapp group were used, it is worth noting that such platforms cannot reach on all potential psychologists thus restricting participation from the outset. In addition, the lack of consensus and keen interest surrounding the topic of EDA, and related varying diagnostic practices means that recruitment may have relied on those with a particular view or agenda in relation to the construct coming forward or being invited by colleagues to participate – thus biasing the study. This is particularly the case where recruitment was shared within the network of the PDA Society who present as very committed to a set outlook on the construct. In addition, although the recruitment method was designed to recruit non-Irish based psychologists, most participants who agreed to be interviewed were working in one geographical location in Ireland. This possibly resulted in a restricted overview of practice as there may have been local arrangements in place to address the lack of formal guidance in relation to assessment for and support of demand avoidance. Owing to the limited geographical spread, social desirability in interview responses may have also been a factor, particularly given the similar training orientation of the lead researcher and participating psychologists, use of alternative data collection methods, e.g., questionnaire for future researchers may mitigate this risk.

A further consideration is that it was not possible to present a detailed analysis of the relationships between multiple codes, given the length limitations of this manuscript. In addition, though psychologists’ accounts of EDA are compared with the construct as outlined by Newson et al. (2003), the current analysis was conducted thematically, and psychologists were not asked to list their criteria specifically. Thus, it is likely that psychologists’ full understanding as to what constitutes EDA may not have been obtained. Finally, 11 psychologists described autistic children, this may have been because they saw the study as associated with the known construct of EDA, which has come to be attributed to autism, or because their most prominent experience of demand avoidance is in children who happen to be autistic. In my view, despite these limitations, this exploratory study which aimed to explore psychologists’ accounts of their experiences of, conceptualisation and approach to demand avoidance advances understanding of the EDA construct, makes important research to practice links, and highlights implications for practice and policy of psychologists working with children.

Conclusion

Little is known about how psychologists’ experience, conceptualise and approach children’s demand avoidance, nor about how they conceptualise extreme demand avoidance (EDA) in their work. The current study gives voice to psychologists in relation to the practices they draw upon and the utility of the construct of EDA as first described by Newson. Though psychologists used EDA aligned approaches, they rejected the medicalised language and utility of the construct. Such a finding is timely given the growing impact the neurodiversity paradigm is having on psychologists’ work. Instead, psychologists focused on the current characteristics and needs of the child, an approach which could allow early identification of strengths and vulnerability, thus reducing inequality in accessing support. Psychologists drew upon a range of approaches in working systemically with the adults in children’s lives, shifting the focus to transactional contexts, and to valuing diversity. It is evident that owing to of their emphasis on systemic work, psychologists are well placed to incorporate neurodiversity into practice.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LH: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. JeS: conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, and writing – review and editing. JoS: conceptualisation, methodology, and supervision. UP: conceptualisation and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allsopp, K., Read, J., Corcoran, R., and Kinderman, P. (2019). Heterogeneity in psychiatric diagnostic classification. Psychiatry Res. 279, 15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.07.005

Astle, D. E., Holmes, J., Kievit, R., and Gathercole, S. E. (2022). Annual research review: the transdiagnostic revolution in neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 63, 397–417. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13481

Atkinson, C., Squires, G., Bragg, J., Wasilewski, D., and Muscutt, J. (2013). Effective delivery of therapeutic interventions: findings from four site visits. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 29, 54–68. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2012.748650

Autism CRC (2018a). A national guideline for the assessment and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in Australia: responses to public consultation submissions. Available at: https://www.autismcrc.com.au/access/sites/default/files/resources/National_Guidline_Response_to_Consultation_Public_Submissions.pdf (Accessed December 11, 2022).

Autism CRC (2018b). A national guideline for the assessment and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in Australia: full national guidance. Available at: https://www.autismcrc.com.au/access/sites/default/files/resources/National_Guideline_for_Assessment_and_Diagnosis_of_Autism.pdf (Accessed December 11, 2022).

Bogart, K. R., and Dunn, D. S. (2019). Ableism special issue introduction. J. Soc. Issues 75, 650–664. doi: 10.1111/josi.12354

Bradley, S., Byrne, M., French, C., Hayes, D., Hughes-Kazibwe, A., and McCarthy, E. (2020). Progressing towards outcomes-focused family Centred practice – an operational framework. Ireland health service Executive Progressing Towards Outcomes-Focused Family-Centred Practice (hse.ie)

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exercise Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exercise Health 13, 201–216. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Braun, V., Clarke, V., and Weate, P. (2016). “Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research” in Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise. eds. B. Smith and A. C. Sparkes (London: Routledge), 191–205.

Brede, J., Remington, A., Kenny, L., Warren, K., and Pellicano, E. (2017). Excluded from school: autistic students’ experiences of school exclusion and subsequent re-integration into school. Autism Dev. Lang. Impairm. 2:239694151773751. doi: 10.1177/2396941517737511

British Psychological Society (2021). Working with autism: best practice guidelines for psychologists. Available at: https://cms.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/Working%20with%20autism%20-%20best%20practice%20guidelines%20for%20psychologists.pdf (Accessed December 5, 2022).

Christie, P. (2007). The distinctive clinical and educational needs of children with pathological demand avoidance syndrome: guidelines for good practice. Good Autism Pract. 8, 3–11. http://www.pdaresource.com/files/Strategies-for-teaching-pupils-with-PDA.pdf (Accessed 9 June 2022).

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist 26, 1–13.

Cunningham, M. (2022). ‘This school is 100% not autistic friendly!’Listening to the voices of primary-aged autistic children to understand what an autistic friendly primary school should be like. Int. J. Inc. Ed. 26, 1211–1225. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1789767

Daffern, M., Howells, K., and Ogloff, J. (2007). What’s the point? Towards a methodology for assessing the function of psychiatric inpatient aggression. Behav. Res. Ther. 45, 101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.011

Department of Education and Science (2007). Special educational needs: a continuum of support: guidelines for teachers. The stationary office. Special educational needs - a continuum of support (guidelines for teachers) (File Format PDF 1.8MB) - 674c98d5e72d48b7975f60895b4e8c9a.pdf (www.gov.ie).

Department of Education and Science (2017). Circular to the management authorities of all mainstream primary schools special education teaching allocation: circular no. 0013/2017. Special Education Unit. Circular to the Management Authorities of all Mainstream Primary Schools - Special Education Teaching Allocation (circulars.gov.ie).

Doyle, A., and Kenny, N. (2023). Mapping experiences of pathological demand avoidance in Ireland. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 23, 52–61. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12579

Duncan, M., Healy, Z., Fidler, R., and Christie, P. (2011). Understanding pathological demand avoidance syndrome in children: A guide for parents, teachers and other professionals, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Eaton, J., and Weaver, K. (2020). An exploration of the pathological (or extreme) demand avoidant profile in children referred for an autism diagnostic assessment using data from ADOS-2 assessments and their developmental histories. Good Autism Pract. 21, 33–51.

Egan, V., Bull, E., and Trundle, G. (2020). Individual differences, ADHD, adult pathological demand avoidance, and delinquency. Res. Dev. Disabil. 105:103733. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103733

Fidler, R. (2019). “Girls who ‘can’t help won’t’: understanding the distinctive profile of pathological demand avoidance (PDA) and developing approaches to support girls with PDA” in Girls and Autism (London: Routledge), 93–102.

Fidler, R., and Christie, P. (2015). Can I tell you about pathological demand avoidance syndrome?: A guide for friends, family and professionals, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Fidler, R., and Daunt, J. (2021). Being Julia-a personal account of living with pathological demand avoidance, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Gabriel, N. (2021). Beyond ‘developmentalism’: a relational and embodied approach to young children’s development. Child. Soc. 35, 48–61. doi: 10.1111/chso.12381

Gillberg, C. (2014). Commentary: PDA–public display of affection or pathological demand avoidance?–reflections on O’Nions et al. (2014). J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55, 769–770. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12275

Gillberg, C., Gillberg, I. C., Thompson, L., Biskupsto, R., and Billstedt, E. (2015). Extreme (“pathological”) demand avoidance in autism: a general population study in the Faroe Islands. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 24, 979–984. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0647-3

Goodall, C. (2018). Mainstream is not for all: the educational experiences of autistic young people. Disabil. Soc. 33, 1661–1665. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2018.1529258

Gore Langton, E., and Frederickson, N. (2016). Mapping the educational experiences of children with pathological demand avoidance. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 16, 254–263. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12081

Gore Langton, E., and Frederickson, N. (2018). Parents’ experiences of professionals’ involvement for children with extreme demand avoidance. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 64, 16–24. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2016.1204743

Grahame, V., Stuart, L., Honey, E., and Freeston, M. (2020). Response: demand avoidance phenomena: a manifold issue? Intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety as explanatory frameworks for extreme demand avoidance in children and adolescents–a response to Woods (2020). Child Adolesc. Mental Health 25, 71–73. doi: 10.1111/camh.12376

Green, J., Absoud, M., Grahame, V., Malik, O., Simonoff, E., Le Couteur, A., et al. (2018). Pathological demand avoidance: symptoms but not a syndrome. Lancet Child Adoles. Health 2, 455–464. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30044-0

Green, J., Leadbitter, K., Ainsworth, J., and Bucci, S. (2022). An integrated early care pathway for autism. Lancet Child Adoles. Health 6, 335–344. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00037-2

Gruson-Wood, J. F. (2016). Autism, expert discourses, and subjectification: a critical examination of applied behavioural therapies. Stud. Soc. Just. 10, 38–58. doi: 10.26522/ssj.v10i1.1331

Hornby, G., and Blackwell, I. (2018). Barriers to parental involvement in education: an update. Educ. Rev. 70, 109–119. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2018.1388612

Hoyne, N., and Cunningham, Y. (2019). Enablers and barriers to educational psychologists’ use of therapeutic interventions in an Irish context. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 35, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2018.1500353

Johnson, M., and Saunderson, H. (2023). Examining the relationship between anxiety and pathological demand avoidance in adults; a mixed methods approach. Front. Educ. 8:1179015. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1179015

Kerr, D. C., and Capaldi, D. M. (2019). “Intergenerational transmission of parenting” in Handbook of parenting: Being and Becoming a Parent. ed. M. H. Bornstein (New York: Routledge), 443–481.

Kildahl, A. N., Helverschou, S. B., Rysstad, A. L., Wigaard, E., Hellerud, J. M., Ludvigsen, L. B., et al. (2021). Pathological demand avoidance in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Autism 25, 2162–2176. doi: 10.1177/13623613211034382

Law, C. E., and Woods, K. (2018). The representation of the management of behavioural difficulties in EP practice. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 34, 352–369. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2018.1466269

Lovaas, O. I. (1987). Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. J. Consulting Clin. Psych. 55, 3–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.1.3

Malik, O., and Baird, G. (2018). Commentary: PDA-what’s in a name? Dimensions of difficulty in children reported to have an ASD and features of extreme/pathological demand avoidance: a commentary on O’Nions et al. (2017). Child Adolesc. Mental Health, 23, 387–388. doi: 10.1111/camh.12273

Milton, D. (2013). ‘Natures answer to over-conformity’: deconstructing pathological demand avoidance. Available at: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/62694/ (Accessed September 6, 2022).

Milton, D. (2018). A critique of the use of applied behavioural analysis (ABA): on behalf of the neurodiversity manifesto steering group. Available at: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/id/eprint/69268 (Accessed September 10, 2022).

Milton, D. (2019) Pathological demand avoidance (PDA) and alternative explanations – A critique. [Conference slides] University of Kent. Available at: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/74107/ (Accessed September 11, 2022).

Moh, T. A., and Magiati, I. (2012). Factors associated with parental stress and satisfaction during the process of diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 6, 293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.05.011

Mols, D., and Danckaerts, M. (2022). Diagnostische validiteit van het concept Pathological Demand Avoidance: een systematische literatuurreview. Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde en Gezondheidszorg, 1–27. doi: 10.47671/TVG.78.22.077

Moore, A. (2020). Pathological demand avoidance: what and who are being pathologised and in whose interests? Global Stud. Childh. 10, 39–52. doi: 10.1177/2043610619890070

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011). Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition referral and diagnosis (NICE guideline CG128). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg128/resources/autism-spectrum-disorder-in-under-19s-recognition-referral-and-diagnosis-pdf-35109456621253 (Accessed December 11, 2022).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013). Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: support and management (NICE guideline CG170). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170/resources/autism-spectrum-disorder-in-under-19s-support-and-management-pdf-35109745515205 (Accessed December 11, 2022).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2020). Surveillance consultation report October 2020: Autism theme (NICE guidelines CG128, CG142 and CG170). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg128/documents/surveillance-review-proposal (Accessed December 11, 2022).

Newson, E. L. M. K., Le Marechal, K., and David, C. (2003). Pathological demand avoidance syndrome: a necessary distinction within the pervasive developmental disorders. Arch. Dis. Child. 88, 595–600. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.7.595

O’Nions, E., Gould, J., Christie, P., Gillberg, C., Viding, E., and Happé, F. (2016). Identifying features of ‘pathological demand avoidance’using the diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders (DISCO). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 25, 407–419. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0740-2

O’Nions, E., Viding, E., Greven, C. U., Ronald, A., and Happé, F. (2014). Pathological demand avoidance: exploring the behavioural profile. Autism 18, 538–544. doi: 10.1177/1362361313481861

O’Nions, E., and Eaton, J. (2020). Extreme/‘pathological’demand avoidance: an overview. Paediatr. Child Health 30, 411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2020.09.002

O’Nions, E., and Noens, I. (2018). Commentary: Conceptualising demand avoidance in an ASD context–a response to Osman Malik & Gillian Baird (2018). Child Adolesc. Mental Health 23, 389–390. doi: 10.1111/camh.12287

O’Nions, E., Viding, E., Floyd, C., Quinlan, E., Pidgeon, C., Gould, J., et al. (2018). Dimensions of difficulty in children reported to have an autism spectrum diagnosis and features of extreme/‘pathological’demand avoidance. Child Adolesc. Mental Health 23, 220–227. doi: 10.1111/camh.12242

Ozsivadjian, A. (2020). Demand avoidance—pathological, extreme or oppositional? Child Adolesc. Mental Health 25, 57–58. doi: 10.1111/camh.12388PDA

Raskin, J. D., Maynard, D., and Gayle, M. C. (2022). Psychologist attitudes toward DSM-5 and its alternatives. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 53, 553–563. doi: 10.1037/pro0000480

Reilly, C., Atkinson, P., Menlove, L., Gillberg, C., O’Nions, E., Happé, F., et al. (2014). Pathological demand avoidance in a population-based cohort of children with epilepsy: four case studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 35, 3236–3244. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.08.005

Royal College of Psychiatrists (2020). The psychiatric management of autism in adults (CR228). Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr228.pdf?sfvrsn=c64e10e3_2 (Accessed December 6, 2022).

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., and Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined Apriori? Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 21, 619–634. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2018.1454643

PDA Society (2022). Identifying and assessing a PDA profile: Practice guidance. Available at: https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Identifying-Assessing-a-PDA-profile-Practice-Guidance-v1.1.pdf (Accessed December 11, 2022).

Stoudt, B. G., Fox, M., and Fine, M. (2012). Contesting privilege with critical participatory action research. J. Soc. Issues 68, 178–193. https://rb.gy/c3mk08 (Accessed November 17, 2022).

Stuart, L., Grahame, V., Honey, E., and Freeston, M. (2020). Intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety as explanatory frameworks for extreme demand avoidance in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Mental Health 25, 59–67. doi: 10.1111/camh.12336

Thompson, H. (2019). The PDA paradox: The highs and lows of my life on a little-known part of the autism spectrum, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Truman, C., Crane, L., Howlin, P., and Pellicano, E. (2021). The educational experiences of autistic children with and without extreme demand avoidance behaviours. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 1-21, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1916108

Trundle, G., Craig, L. A., and Stringer, I. (2017). Differentiating between pathological demand avoidance and antisocial personality disorder: a case study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Offending Behav. 8, 13–27. doi: 10.1108/JIDOB-07-2016-0013

White, R., Livingston, L. A., Taylor, E. C., Close, S. A., Shah, P., and Callan, M. J. (2022). Understanding the contributions of trait autism and anxiety to extreme demand avoidance in the adult general population. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 2680–2688. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05469-3

Wilding, L., and Griffey, S. (2015). The strength-based approach to educational psychology practice: a critique from social constructionist and systemic perspectives. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 31, 43–55. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2014.981631

Woods, R. (2018). An interest-based account (monotropism theory) explanation of anxiety in autism and a demand avoidance phenomenon discussion. [conference slides] Scottish Autism Parc fringe, Glasgow. PowerPoint Presentation (shu.ac.uk)