95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 14 September 2023

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1220658

Introduction: Children and families residing in regional Australia experience higher rates of vulnerabilities coupled with inadequate access to the early childhood health and early intervention services which pose increased risk to their health, development and wellbeing. The current study was designed to respond to the inherent complexity of supporting effective integrated service provision in regional communities, with a view to develop a model of effective service integration that leverages the capacity and opportunity of universal early childhood education (ECE) provision.

Method: The study adopted a qualitative multiple case study design to explore the perceptions of ECE professionals across six regional ECE services and two early intervention professionals operating from a regional early childhood intervention (ECI) organization. Data included an initial audit of the service system landscape coupled with facilitated discussions (focus groups and interviews) to identify facilitators and challenges to service integration and current patterns of service usage and engagement.

Results: Findings highlighted the foundational importance of relationships for establishing trust, engagement and service sustainability, as well as the need for embedding structural supports, including the professionalization of educators, the utilization of a key worker model, and staff retention. Systemic constraints, including limitations and inconsistencies in community infrastructure, program atrophy, and the complexity of referral systems, were seen to undermine effective service integration.

Discussion: Findings speak to the potentiality of the ECE context as a hub for effective service integration within a functional practice framework for ECE. We conclude by offering a suggested model to ensure service connections, and enhance professional capacity and sustainability.

Young children residing in regional Australian communities experience higher levels of vulnerability across a range of health and educational domains than their metropolitan counterparts (Arefadib and Moore, 2017; NSW Ministry of Health, 2019; Australian Early Development Census, 2021). Initiatives designed to shift these trajectories include providing specialized assessment and targeted support from a range of health and allied health, education, and early childhood professionals and programs. Within regional contexts, however, availability of these health and other early childhood intervention (ECI) services is more limited than in metropolitan settings and, when services are available, they are harder to access as they are typically more fragmented and siloed (Moore and Skinner, 2010; Krakouer et al., 2017). Ensuring access for young children and their families is further complicated by a service system dependent on familial capacity (e.g., education, means, time, ability to travel, etc.), for both access and engagement, by design (Royal Far West, 2017, 2018). For example, in a longitudinal study examining sociodemographic factors associated with maternal help seeking for children with developmental concerns, Eapen et al. (2017) found that children experiencing vulnerability are often subject to, “an inverse care effect where children with the greatest health needs have the least access to services” (p. 968), with mothers from low SES backgrounds least likely to access support services. Collectively, these factors – availability, access, and design – ensure that children and families in regional and rural settings with the greatest needs are the least well equipped to identify and engage with a complex service landscape. For these reasons, it is important to understand whether early childhood education (ECE) services, which are increasingly funded for universal service provision and recognized as foundational for the Australian educational system, can be enabled to support effective service integration for children and families.

Given the challenges facing families with complex needs, attempts to better integrate health and ECI services have gained increasing attention (Moore and Skinner, 2010; Press et al., 2012; Saunders et al., 2022). Initiatives that aim to provide communities with a one-stop-shop or wrap-around service are widely lauded because, when they are well designed (Moore and Skinner, 2010; Press et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2012; Barnes et al., 2018), they provide families with a single-entry point and ensure that children and families are more likely to access the services they need across a range of domains (e.g., ECI, adult education, family support, etc.). Whilst such models may be ideal for areas of high-density disadvantage, or where the community has sufficient support and critical mass, it is not clear that they can meet the needs of many regional communities. Furthermore, while much thought and research has been devoted to ideal models for inter-agency working to support such integration (e.g., Barnes et al., 2018), little research has explored how a model of effective service integration supported through ECE can be implemented in contexts where systemic and structural factors mean that the one-stop-shop model is not viable or high levels of complexity in the service landscape are likely to persist.

The current study was designed to respond to the inherent complexity of supporting effective integrated service provision in regional communities, with a view to develop a model of effective service integration that leverages the capacity and opportunity of universal ECE provision. We sought to examine the viability of a model that places children at the center of decision making and empowers early childhood educators to embrace inter-agency work in collaboration with families. We targeted regional ECE services that were in communities characterized by low SES, with the assumption that these communities would have a greater need for ECI and health services and therefore would afford a better capture of child and familial need, service complexity and capacity.

Approximately 30% of Australia’s children reside in non-metropolitan areas (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020) and these children are twice as likely to experience developmental vulnerability (27%; Royal Far West, 2018) than their metropolitan counterparts. Despite higher levels of need, the most recent estimate suggested that almost a third of children in regional or remote NSW are unable to access the health and intervention services that they require (Royal Far West, 2018), a situation that has deteriorated since the onset of COVID-19. Many of the reasons for these service gaps are systemic or have high-cost implications, including complexities in the recruitment and retention of professionals, large distances between communities and services, and inadequacies of transportation services (Arefadib and Moore, 2017).

Insufficient provision of health and ECI services for children in regional settings can result in cycles of disadvantage that amplifies developmental disparities between children from metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas (Arefadib and Moore, 2017; Royal Far West, 2017). For example, a mapping of language and communication developmental vulnerabilities across Australian geographical areas showed the 27 communities with highest rates of vulnerability were those communities with poorest access to speech pathology services (McCormack and Verdon, 2015). Such service deserts result in longer waiting lists, with some families reporting wait times of up to 16 months (Royal Far West, 2018). This can mean that by the time children access these services the critical window for optimal developmental outcomes has essentially closed. The paucity of support across the early childhood service system – particularly in areas of geographical isolation and high levels of poverty – is a significant risk factor to the health and wellbeing of these communities.

The drive toward more integrated early childhood services has focused predominantly on community centers where a range of education, health, intervention, and support programs are available for children and families (Press et al., 2012). The co-location of services is designed to facilitate access to a range of programs and agencies, a model that has enjoyed some success (e.g., Taylor et al., 2017; Barnes et al., 2018). There is also recognition, however, that services can be effectively virtually integrated when there are strong connections and referral pathways between them, and it is not uncommon for there to be a combination of co-located and virtually integrated services within community contexts (Press et al., 2012; Moore, 2021). The success of both co-located and virtually integrated services depends on joint planning and coordination of service delivery in ways that recognize the challenges and complexities facing families (Barnes et al., 2018). This is best achieved through strong leadership and collaborative inter-agency working or partnership to support children through a family-centered approach (Moore and Skinner, 2010; Press et al., 2012).

Despite growing evidence of the efficacy of such integrated service models, there exists a major gap in focus on the compatibility or transferability of these models to regional communities. The paucity of services within many regional areas (Arefadib and Moore, 2017) means that co-location models are not feasible for the majority of communities, although elements of co-location may still be possible. The emphasis on virtual integration through partnership and collaboration is likely to be more promising but depends on families and children understanding the need for and engaging with services in a sustained manner during the early childhood period. In this respect, ECE, which is a common feature in virtually all regional areas, represents a context within which families can encounter and engage with health and ECI services in an environment that is supportive and family-centered.

High-quality ECE is widely recognized as an essential feature of the service landscape from the point of view of supporting children’s learning, development, and wellbeing (Melhuish et al., 2015; Goldfeld et al., 2016) but ECE provision and practice is, understandably, largely focused on education, albeit within an inclusive framework (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, 2021; Australian Government Department of Education, 2022). For ECE services to be repositioned as hubs for integration, educators need to understand their place in the broader early childhood development service landscape and embrace professional practices that support inter-agency working and service integration; a role that is not formally recognized, and for which training and support is not currently provided. Nevertheless, many ECE services already find themselves providing these extended functions in an ad hoc manner and the potential benefit of service integration through ECE is clear (Taylor et al., 2017; Barnes et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2020).

It is timely, therefore, to investigate a model for effective service integration through ECE. Such an approach is not inconsistent with the current focus in the literature on place-based and virtual service integration through inter-agency working (Moore, 2021) but recognizes that ECE plays a distinctive and on-going role in the lives of children and may be uniquely well-positioned to support collaborative work with families. In regional settings specifically, the role of ECE as a context for service integration demands further examination.

The current study is a part of a larger research project – Supporting Effective Service Integration (SESI) – that explored service integration and capacity building within regional early childhood systems through the development and implementation of an innovative model of physical and virtual service integration that is bespoke to individual communities and supported through local ECE services (Neilsen-Hewett et al., 2020).

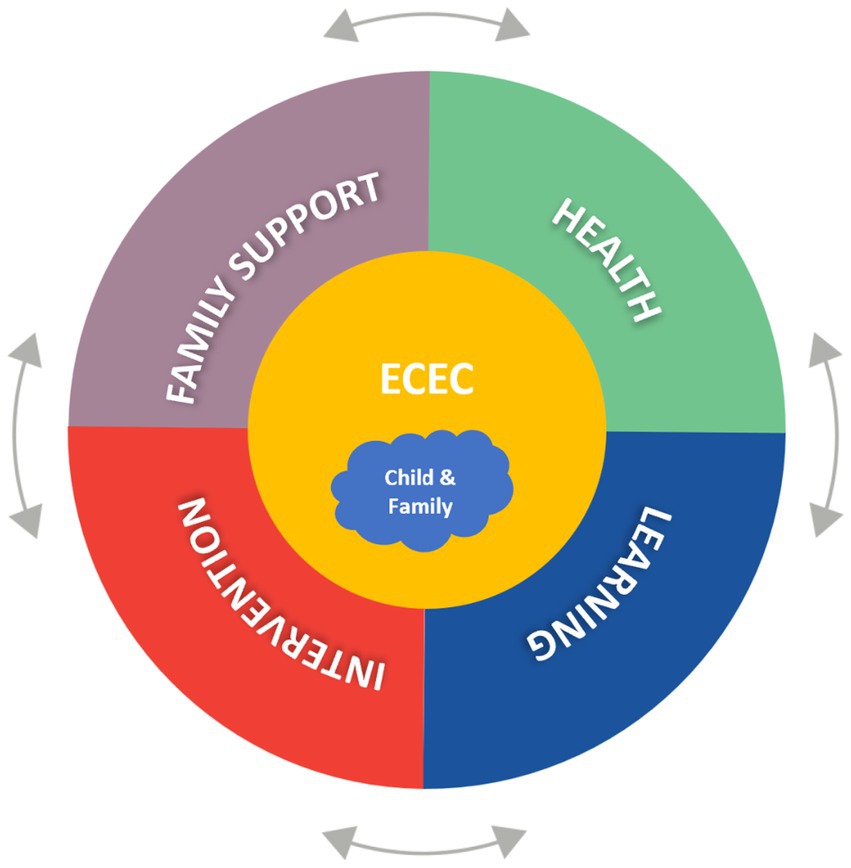

Figure 1 illustrates the functional model of effective service integration developed for the current study in relation to these ECE settings. The approach differs from common models for service integration in that it deliberately positions the ECE service at the heart of integration while recognizing that other (wrap-around) services (e.g., health, ECI, family support, etc.) may be connected in a variety of ways and there is likely to be uneven access to such services. This model builds upon the universal ECE platform and prioritizes the strengths and capacities of the ECE context. It is a capacity driven quality practice model that is sustainable in its focus, so that the skills required to understand children’s needs, support families, and link them with services, become part of the normal expectation of high-quality ECE. This model recognizes the essential role that educators can, and often do, play in making sense of and navigating the service landscape for children and families, despite the fact that they are neither decision makers nor providers of such services.

Figure 1. A functional model for supporting effective service integration (SESI) in non-metropolitan contexts.

The analysis presented in this paper includes an overview of the current models of access and practices within early childhood service systems across six communities in regional and rural New South Wales, Australia. We investigate the facilitating and impeding factors of existing access pathways between ECE and health and ECI services, drawing on the perspectives of ECE educators and ECI service professionals working in these communities.

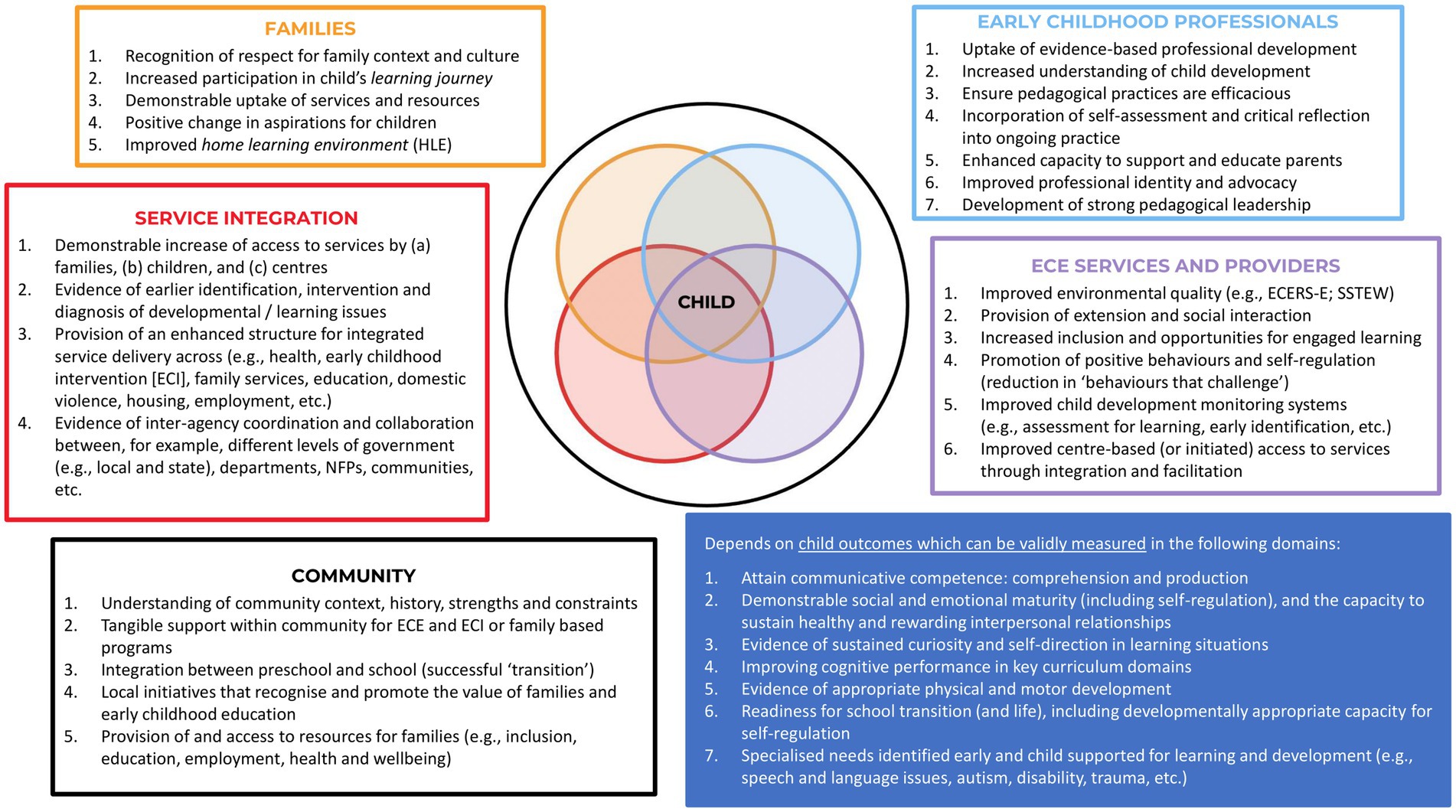

The SESI study was funded by the Ian Potter Foundation [20180488] and broadly investigated how ECE service-level quality, educator capacity and ECI relational connections could be enhanced via an evidence-based professional learning (PL) program for educators. At the heart of the SESI intervention was the Leading for Early Education, Development and Advocacy (LEEDA) professional learning program. The content, structure and form of the PL was informed, in part, by research evidence around effective PL design (e.g., Siraj et al., 2022), knowledge of the target ECE workforce and their work contexts, as well as a mapping of the key organizations, relationships, and connections across each regional network. The LEEDA PL was situated within the broader LEEDA practice framework (Neilsen-Hewett and de Rosnay, 2017; see Figure 2) which was used to inform the context of the work and identify challenges and strengths across each of the participating ECE contexts. Importantly, the broader LEEDA framework provided a flexible but comprehensive guide for ECE professionals and communities to understand the elements that need to combine to provide optimal outcomes for children.

Figure 2. The Leadership for Early Education, Development, and Advocacy (LEEDA) framework for optimizing children’s learning, development and wellbeing within the ECE context.

The SESI study was conducted over 5 stages. Stage 1 involved community consultation, recruitment of participants, and establishment of the reference group. Stage 2 involved a comprehensive review of national and international models of integrated service delivery and an initial audit of participating ECE services and their community service context, which informed facilitated discussions with educators to identify current patterns of service usage and engagement. Stage 3 involved the development and delivery of the LEEDA professional learning program.

The LEEDA PL was delivered over seven full-day group-based sessions. The content was underpinned by rich evidence-based understandings of process quality, child development, relationships and active engagement, holistic learning, value for child assessment and differentiation, community connections, and support for the home learning environment. Content was contextualized by responding to the challenges and strengths of participating ECE services, which was revealed through initial educator focus groups (Stage 2) and coupled with baseline assessments of classroom quality practice using the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Extension (ECERS-E) (Sylva et al., 2006) and the Sustained Shared Thinking and Emotional Wellbeing scale (SSTEW) (Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2008).

The LEEDA PL prioritized collective participation and collaboration within and across services, active learning, pedagogical leadership, approaches to change management, reflective practice, quality improvement, contextualized and differentiated practice, and self-assessment. Contextualized learning was further supported through an embedded coaching and mentoring program that occurred with each of the participating services and was structured to occur in-between group-based PL sessions.

Stage 3 was to be delivered face-to-face over a six-month period, commencing February 2020, however COVID-19 resulted in a more disrupted delivery pattern, which included some delays in session delivery, the inclusion of one refresher session and a subsequent move to an online delivery model for one of the group-based sessions. Pandemic disruptions extended to the in-service face-to-face delivery of the coaching and mentoring component, which was moved (in response to participants desire to maintain contact) to a virtual model of delivery, leveraging online and telecommunication technologies. These disruptions presented an additional research opportunity to explore the impact of COVID-19 on service integration within regional ECE services, which became Stage 4 of the project. Stage 5 focused on the review and evaluation of the LEEDA PL intervention through an examination of shifts in practice quality as assessed by the ECERS-E and SSTEW scales, as well as a process evaluation, drawing upon post-intervention qualitative surveys and facilitated semi-structured interviews with participating ECE services to determine perceived impact on participating educator, ECE service practice(s), inter-agency and service connections.

The findings presented in the current paper draw upon a qualitative multiple case study design to explore both early childhood educator and early childhood intervention (ECI) service provider perceptions of early childhood service integration in regional New South Wales, Australia. The current paper reports on Stage 2 of the SESI project, which includes three phases: March–December 2019 (Phase 1), June–August 2019 (Phase 2) and July 2022 (Phase 3). Phase 1 involved an initial audit of the service system landscape across the six target communities, this was informed by a scoping exercise that involved discussions with key allied health and ECI services. Phase 2 involved a series of educator focus groups and examined patterns of service usage as well as the potential facilitators and barriers to service integration. This phase was used to: (1) further inform the audit of the service environment and utilization within each of these communities; (2) identify facilitators and barriers to service access; and (3) inform the design of the LEEDA professional learning intervention program (as part of the larger study). To better understand service integration and access in these communities, as well as the challenges, Phase 3 included semi-structured interviews with two ECI service professionals from a not-for-profit organization situated in regional NSW and working with the ECE services.

Participants for Phase 2 were center directors and educators from six ECE services in regional NSW, Australia. The majority of educators from each participating ECE service attended each focus group. Participating services were purposefully selected for high levels of early childhood vulnerability Australian Government Department of Education and Training, (2018) and high levels of socio-economic disadvantage (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). This strategy ensured the credibility of participant knowledge was reflective of the research aims (Carpenter and Suto, 2008). Participants for Phase 3 were the CEO (ECI-1) and a key worker and program leader (ECI-2) from an ECI service (Table 1).

Data was collected across all three phases. Phase 1 involved the initial audit of services, Phase 2 included semi-structured facilitated focus groups with participating ECE services, and Phase 3 involved semi-structured individual interviews with participating ECI professionals. Each of these stages are detailed below.

This involved an audit of services based on the research teams’ independent survey and scoping of the service landscape across the six communities. The scoping process involved a comprehensive google search to identify the range of services in each region, a sweep of local service directories, connection with community services to confirm common referral pathways, and calls to community medical centers to clarify and confirm outreach services.

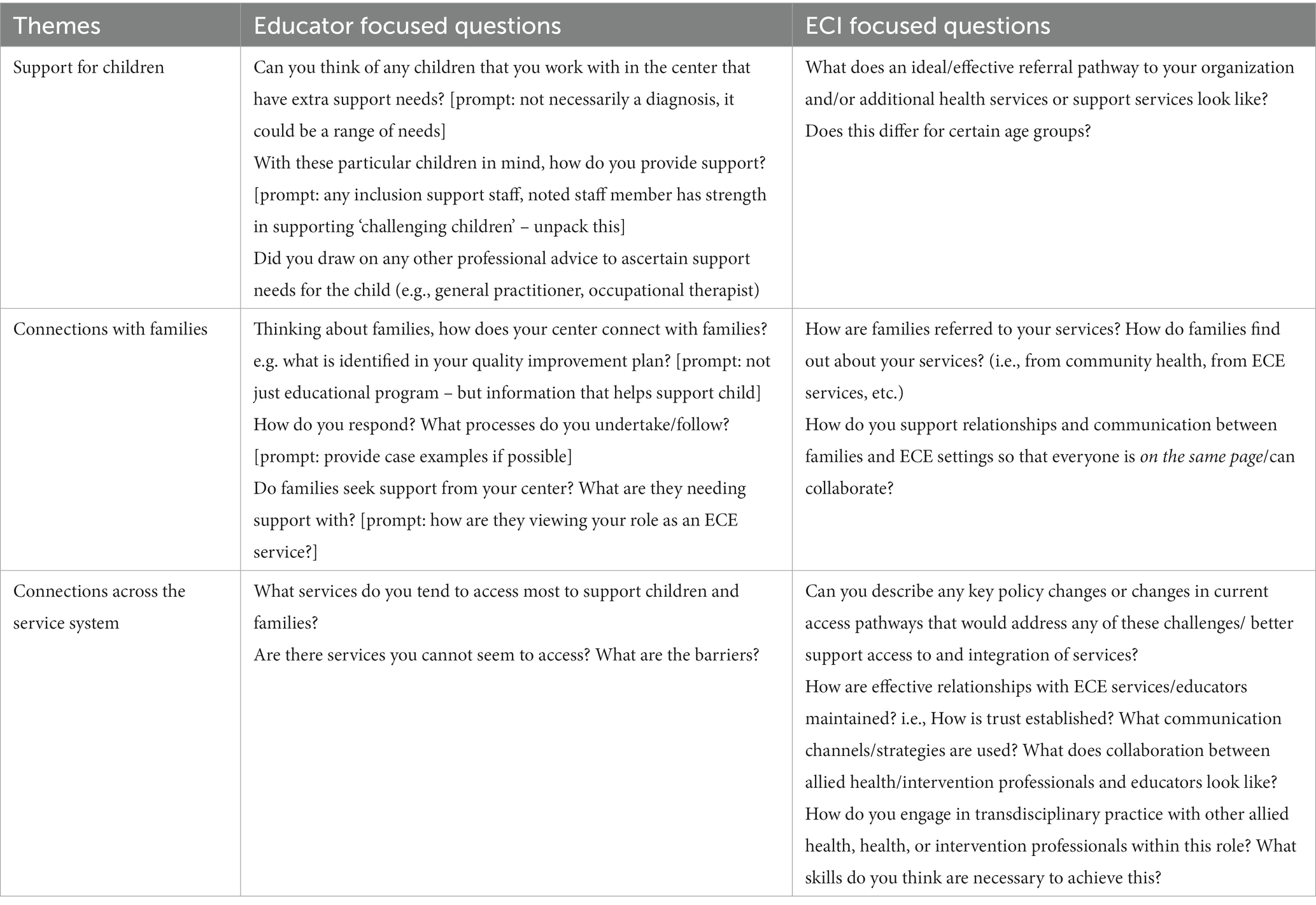

Semi-structured facilitated focus group interviews were conducted at each ECE service. Focus group interviews were recorded and transcribed for later analysis with Nvivo (Release 1.7.1). Phase 2 questions were largely exploratory in nature and informed by key themes emerging from the service integration literature. All participants were provided with questions prior to focus interviews (see Table 2).

Table 2. Example questions from phase 2 semi-structured focus group interviews (ECE) and phase 3 semi-structured individual interviews (ECI professionals).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted individually over Zoom. Phase 3 questions were also exploratory in nature, informed by key themes emerging from both the service integration literature and findings from Stage 2 analysis. All participants were provided with questions prior to focus interviews (see Table 2 for examples). Interviews lasted approximately 1 h.

Analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guidelines for thematic analysis. Separate thematic analyses were conducted for Stage 2 and Stage 3. Data transcriptions underwent multiple preliminary readings to enhance familiarization. Stage 2 data was analyzed first and coded semantically, driven by inductive and deductive orientations, and informed in part by an ecological orientation (e.g., looking at perceptions of connections with families, connections across contexts, systemic influences) focusing on identified facilitators and barriers to integrated practice (see Barnes et al., 2018 for a comprehensive review). Coding was further affirmed through consultation with relevant literature. The content within these organizing frameworks were then coded using an inductive approach (i.e., data codes were derived from interpretations of the data) and data relevant to each code was then collated with candidate themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006) generated to form a code book. Stage 3 data analysis followed a similar protocol but separate codes and themes were generated to fit with the ECI service context.

Examination of multiple case studies allowed for the compilation of a rigorous dataset that identified similarities and differences between sites, enhancing the generalizability of this data for the target population (Baxter and Jack, 2008). Researcher triangulation of data and results was also conducted to critically evaluate and enhance rigor and the richness of the findings (Liamputtong, 2013). Finally, data were shared with participants during member checking group discussion sessions (separately for ECE services and ECI professionals) for feedback and/or clarification.

The results speak to the current service system across the six locations and highlight capacities, challenges, and supports as identified by the educators and ECI professionals involved in this study. The functionality and needs of the service system are captured in terms of relational supports, the role of collaboration and communication within and across the service system, structural features needed to support service connections along with systemic supports and constraints.

The audit of services was based on the research teams’ independent survey and scoping of the service landscape across the six communities (including a sweep of local service directories for each participating ECE service) (Phase 1) along with information derived from the educator focus groups (Phase 2). Participants were asked to reflect on which early childhood services or professionals they engaged with and any areas in which they were struggling to access services. Open discussion of service engagement was promoted with prompting based on the results of the Phase 1 service scoping. The resulting data were combined for illustrative purposes (including feedback to the ECE services) by mapping the broad range of available services to the SESI model of service integration (see Figure 3). This process provided a visualization of the complexity of the service landscape and supported collective understanding of the ECE services’ engagement patterns.

Frequency of service usage was calculated from focus group interview data and is captured in Figure 3. While not exhaustive, this figure captures the complexity of the early childhood and family service system across these communities and ECE engagement patterns. The white boxes indicate utilization by the ECE services. The weight of the outline reflects higher usage as reported by ECE services (which includes their knowledge of family utilization), so those with “bolder outlines” represent higher engagement/usage. For example, among the Familial Support Services the highest rates of usage were recorded for early intervention family programs and family referral services, followed by child protection/family and community services, financial support, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services. Circles indicate organizing nodes within the service landscape. For example, within the Health quadrant “early childhood health clinic” is positioned as the parent or organizing node for common services such as pediatricians, maternal child health nurses, and dental services/checks.

Relationships between educators, ECI professionals, and families were critical to ensuring effective service integration. This encompassed the formation and maintenance of trust, active collaboration, and the quality of communicative practices within relationships. These subthemes are elaborated below.

Reciprocal and trusting family–educator relationships were perceived as essential for supporting child and family service access across the participating ECE services. Building trust was viewed by services as being dependent on time for the relationship to develop, as well as having opportunities for sustainable connections. This demanded prioritization with respect to establishing and maintaining relationships, particularly with families who may be fearful of judgment or stigmatization. Services spoke to ensuring that families trusted in their professional knowledge. Once trust was established, educators within the services were able to draw upon their relationship to support families to navigate often complex referral systems, “If you do not have that rapport it’s kind of very delicate… Some people are really forthcoming and other people aren’t and you find things out over months and months” [ECE-4].

ECI professionals also positioned relationships as central to integration. Referrals largely came through ECE services and were facilitated by established connections and educators’ understanding of child and family need/capacity. Trust between ECI professionals and families was described as often being moderated by the educator–family relationship. Having a sustained and positive reputation within the community was viewed as integral to ensuring familial and educator engagement,

“…A couple of years ago when we were trying to get children to come into a screening, and [an educator at the ECE service] put out a note [to families] and said, “if I tell that family that a speech pathologist is coming to the service, that child won't turn up on that day, but if I say ‘someone from [the ECI service] who they know is going to be here’, they go ‘Yeah, that's cool’”… it’s really striking to us about the level of trust and time that you need to build that relationship” [ECI-1].

Across the majority of ECE services, educators shared similar sentiments regarding trust between themselves and ECI professionals. The most trusting relationships were evident when an ECI professional was consistent, spent time in the service with children and educators, worked collaboratively by sharing their knowledge and insights, and respected the professional knowledge of educators.

Active collaboration and consistent communication with families underpinned familial and child engagement with services. One service described meeting with families regularly to establish shared goals and common strategies, while another service worked alongside families in developing behavior support plans. Services (n = 4) highlighted the importance of communication between staff to monitor child and family needs and to ensure consistency when implementing support strategies.

Communication and collaboration between educators and ECI professionals enhanced access pathways for children and families and ensured a more streamline assessment process, with educators within two of the participating services making preliminary referrals on behalf of families. These educators collaborated with ECI professionals to support consistency for children,

“The partnership we have with [allied health professional] is she is seeing some of the children here…she's coming in and she's talking with us about what she's doing. Then we're implementing it into individual learning plans. So, we are supporting speech pathology that is happening outside of the center and putting it into the center” [ECE-2].

ECI professionals spoke to the importance of embedding collaborative practices to empower both educators and families, while acknowledging educators’ knowledge of the child. They highlighted the value of sustained conversations, active collaboration, flexible and contextualized support and the time needed to make this happen,

“You are not coming in as the holder of all the knowledge, because that's not the case … they've got lots of experience in many cases…you've got some people with really diverse skills, and so we need to be listening to what they've got to say. We need to listen to what their main need [if we don’t], then that doesn't build relationships …” [ECI-1].

Connections across ECE and ECI services hinged largely on relational quality, with fragmentation or service silos more likely in communities where relationships between health, ECI professionals and educators broke down or did not exist. For example, one ECE service was largely unaware of the available services in the community. This was attributed to the high rates of program atrophy and the competing demands that educators faced, “We do not have time to become familiar with what services are available and that’s something that we would really like help with” [ECE-4].

A culture of mistrust of health professionals, including GPs and pediatricians, was evident amongst some educators at two of the participating services. Conflicting agendas, absence of communication and misaligned recommendations created a divide between health professionals, educators, and families. The dismissive nature of health professionals and a perceived lack of value these health professionals had for the educator voice was positioned as a major barrier to achieving diagnosis and appropriate support,

“You don't get support from professionals. We've referred some of our families onto pediatricians down here …they say there is nothing wrong with them. We write letters. We put the documentation in, but they just don't look at that and it is hard work…. It takes us to re-fight. Not fight the parents but reencourage them to go and get a second opinion…there's that conflict there…they trust us but then they trust their doctor...that can go on for months” [ECE-3].

Open and honest communication between educators and families was at times challenging, due to fear of judgment, stigmatization, and embarrassment. One service spoke of genuine concerns for a child’s safety, “We know that child has a global delay. We know that child has autism. What benefit do we gain by telling that family because we know that child is going to get bashed [by the family].” [ECE-5].

Structural supports and constraints included characteristics important for ensuring service access and integration, such as utilization of a key worker model, embedded access to ECI, staffing arrangements, and the professionalization of educators.

The ECI professionals reported that organizational utilization of a key worker model enhanced relationships between families, educators, and ECI professionals. The key worker was selected based on the child’s goals and needs, while ensuring a ‘best fit’ for the family. This relationship was consistently reviewed to ensure mutual benefits for all parties,

“Relationship-wise, sometimes it might not be the right fit. We try to get it right, but if it's not yet where it should be, and that might be for the family and/or for the therapist…it's just got to be the right fit for everyone for it to work really effectively because if it's not … the families aren't invested” [ECI-2].

The ECI professionals spoke to the importance of shared approaches and consistency across contexts. Key workers navigated connections across and within their own transdisciplinary team, families and educators ensuring all parties had access to the same information.

ECE services (n = 4) reported similar benefits when they implemented an informal key worker approach, typically an educator who became the primary communicator for the family, source of information about the child, as well as navigating access pathways,

“I am going to link [child] to [ECI service] …the family will go with [key educator] so she will introduce them…I wanted them to go with someone they felt comfortable with first” [ECE-1].

This model was viewed as particularly effective for families experiencing high levels of vulnerability.

This subtheme spoke to the value of having face-to-face visits from key health and ECI professionals and was reported across the participating ECE services. These visits typically involved child assessments or therapeutic sessions with children and provided an opportunity for collaboration with educators. Models that prioritized support for educator practice with the child were positioned as being more beneficial than treatment models for which ECE was treated as a setting for the service provider to access the child. In-service screening opportunities were important for early identification of children’s additional support needs and provided incidental support and capacity building for educators.

Given the scarcity of services in regional settings, the ECI professionals advocated for hybrid models of service support that included the use of digital technologies (e.g., video meetings, email, video recordings, and texting). These models did not replace opportunities for face-to-face encounters but allowed for more continuous and frequent support,

“It's probably a combination of [communication] channels …there is a place for virtual support, such as Zoom calls, for one-on-one coaching but it needs to be supported with face-to-face visits…it's the observation of what's happening [that enables] the best outcomes” [ECI-1].

Across the services, staffing arrangements were positioned both in terms of staff stability as well as roles and capacity. Staff longevity within the ECE service was identified by most of the participating services as important for developing connections and maintaining relationships. This was particularly important within Aboriginal communities where trust and respect between educators, families, and the community needed to be cultivated over time, “The longevity of the staff here is really something you have got to retain… [it takes] 3 years to be accepted in this community” [ECE-1].

The appointment of additional staff, including administration, family support workers, and inclusion support subsidy (ISS) educators facilitated ECE service access to health and family services. Administrative and family support workers were identified by educators from two of the participating ECE services as being helpful in connecting families to services and taking some of the burden off educators who positioned themselves as time poor. Access to and funding for these positions, however, was not equally distributed across the services,

“There wasn't any funding for a family worker…so instead the staff getting on the floor and reaching out to the odd intervention [which] takes them away from the children… so interactions have dropped” [ECE-2].

Retaining consistent ECI personnel was identified by the ECI professionals as important for maintaining family and educator relationships, with high staff turnover posing a significant challenge to maintaining connections. One solution was to ensure organizational consistency in core values, philosophical approach, and a shared practice framework,

“In relationship consistency I'm talking about either staffing that are consistent, or if they can't be consistent, the quality is consistent. You've got people with some of the really core values and the things that we know make a difference in those relationships like the coaching and the listening and the being context aware and being flexible and fitting in with that environment being really respectful, being very truly collaborative. They're the things I'm talking about consistency, because if you get a lot of changes of staff and it's a new face every six months, then you can't build relationships easily in that context” [ECI-1].

Characteristics of the individual and their perception of their role as an ECE professional (and what that role encompasses) was an important factor in ensuring effective service integration, “If we were just here as an early childhood education center looking at the developmental areas and nothing else [intervention is] not going to work” [ECE-1].

Recognizing their role within the identification and referral process was crucial to educators’ ability to drive these processes. ECE services (n = 2) spoke to the importance of engaging in professional learning opportunities, this knowledge was crucial for not only supporting the referral of children to intervention services, but for ensuring effective evidence-based teaching practices within the ECE context. Conversely, when support strategies and teaching practices were not underpinned by evidence-based practice, educators felt ill-equipped to provide adequate support and noted increased challenges with respect to children’s behavior and engagement.

More than half of the participating ECE services felt ill-equipped to provide effective support for the children in their care, “I’m not trained in autism … so until [a child has] an assessment we do not have the expertise here to be doing the scaling we do now” [ECE-5]. This sense of helplessness led to feelings of frustration and burnout,

“I have had conversations with individual staff members about particular children and they’re getting to a point where they feel they’ve just run out of their tools which are all being used and they’re not working” [ECE-4].

“The pressure in the room was ridiculous…we had staff ready to walk out…it was a pressure cooker” [ECE-1].

Task overload and scope creep, complex professional demands and lack of time and opportunity for staff reflection contributed to educator dissatisfaction across the participating service, with educators from one service noting increasing numbers of children with high support needs,

“I went down through each child and talked about the situations…some pretty critical stuff…horrendous trauma stuff…we never have time to unpack that stuff…we come in with the best intention [but] never have time to discuss what's happening or where we are trying to get to” [ECE-5].

Complex and convoluted referral and funding documentation were perceived to strip time away from teaching and rich interactions.

Systemic constraints included limitations and inconsistencies with community infrastructure, program atrophy, complex referral systems and funding. These were positioned as being largely outside the control of educators, ECI professionals and families, and were perceived as a major barrier to access. Conversely, systemic supports, such as organizations adopting innovative approaches to accessing funding, worked towards addressing some of these issues.

Lack of transport, housing, health and ECI services within rural and regional communities were a major factor in preventing access to support services,

“Most of our children do not attend [early intervention] anymore because they cannot get there” (ECE-2); “Housing is a challenge for integrated services because no one’s interested in that higher level of integrated services if they do not have a safe place to be” [ECI-1].

The limited number of ECI services contributed to longer wait times, delaying access to crucial intervention for children and forcing families to seek out of area support or private services at greater cost. Most of the participating services reflected on the detrimental effect this had on opportunities for collaboration and relationship building,

“[You] used to walk in the doctors and they would look at your history and they'll say "Oh how did you go with that?". So now you come in and they go "Oh so … what's wrong?"…where is the confidence there…our community is growing, and I don't think we've got enough surgeries in the area to compete or cope with the amount of families” [ECE-3].

All participating ECE services expressed frustration with high levels of program atrophy; services that were perceived to be valuable often broke down due to changes in funding or the transient nature of health and intervention professionals,

“[ECEC organization] put on a speech pathologist…a two year contract and she was our own speechie…she did help us a lot but she left before her contract was up and they never replaced her” [ECE-6].

ECI professionals spoke to issues around staff retention and caseload within rural and regional areas,

“Attracting staff is a real issue, like it's not a [organization wide] issue, it's an industry wide issue. There's a huge disparity between the amount of staff that are needed and the amount of staff that are available. And I think the NDIS has created this artificially high need for therapists and so we're having young therapists coming out of university and for the first time they're going straight into private practice” [ECI-2].

Complex and confusing referral pathways and funding systems were a major constraint to access and integration. Many services voiced their frustrations with referral systems that required families to drive processes, often without the support of educators. Even when educators supported families to seek referral and assessment, many families did not engage, “This particular parent did not end up engaging [with ECIS]. Even though we did all the paperwork for her” [ECE-1]. Such reticence was often attributed to the stigma families experienced around having a child with additional support needs.

Services emphasized their frustration with ISS and the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) funding systems, reporting that children with less severe or undiagnosable support needs, such as trauma, missed out on vital early intervention. The lack of funding supports also meant children were sometimes refused enrolment, “If the child had very high needs that’s going to stop that program for everyone, we are not going to take the child” [ECE-1].

Educators from three of the participating ECE services also spoke to challenges surrounding the lack of targeted funding support across both health and ECE systems for children under 3 years of age. There was less clarity amongst the educators at these services as to the funding and diagnostic entitlements for younger children. There was a perception amongst educators that children under three were not eligible for diagnosis from a pediatrician, excluding these children from accessing ISS or NDIS funding. Educators also reported that these younger children attending long day care services often had less access to funding and subsidies than children of preschool age.

Despite voicing their frustrations with complex funding systems, ECI professionals also spoke to the innovative ways in which they supported ECE services. This included offering subsidies for consultation and professional learning opportunities and utilizing grants and government initiatives to provide specialized programs. This was positioned as beneficial to both building relationships with ECE services and contributing to the professional skillset of educators. Despite this success, there were constant threats to program sustainability due to changes to government policy.

“… The relationships that have been built there will be changing. We’ve put another request for tender in, but they've changed it from LGA to health district, so they only want one organization per local health district. They have basically absorbed two areas now. …that was disappointing because we had put in the discussions … now we’ve lost the consistency is. It is a shame” [ECI-1].

Findings from this study speak to the significance of relationships for ensuring sustainable service systems, the need for systemic commitments to evidence-based practices, and the impact of utilizing a key worker model to ensure continuity and connection across both ECI and ECE services.

Within this study, the relationships between educators, families, and ECI professionals were key to ensuring effective service integration and familial navigation of ECI services. Consistent with previous research, the establishment of collaborative relationships between educators and families, depended on educators’ ability to establish trust and engage in open communication (e.g., Hadley and Rouse, 2018), which was even more prominent within services with higher proportions of families experiencing disadvantage (Roberts, 2017). The recognition and prioritization of relationships was particularly robust in the current study, a narrative that aligns with current policy initiatives (e.g., NSW Brighter Beginnings and the First 2000 Days Framework) as well as practices emphasized within the National Quality Standards (NQS) and Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) V2.0 (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, 2021; Australian Government Department of Education, 2022). Despite this growing awareness, educators identified a disconnect between the recognized need for educator-family relationships and the time and support provided to educators to build capacity and confidence in making and maintaining relationships with families (O’Connor et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2021) with some educators noting a certain hesitancy to engage with ‘hard to reach’ families.

Educator capacity emerged as a critical consideration for ensuring familial support and engagement. This factor seems to be particularly salient in regional and rural areas or areas where there are higher rates of familial vulnerability and where the ECE service is often the first and only entry point into the early childhood service system. Recent research by Moore (2021) speaks to the ways in which the quality of relationships between early childhood practitioners and families directly affects how effective they can be in supporting and empowering families through strength-based, capacity-building, and family-centered help-giving practices (e.g., practices that value and respect familial choice, voice, and action). If we are indeed going to advocate for a more holistic and integrated approach to ECE, then we need to ensure ECE professionals are not only versed in pedagogical practice, but they are empowered in their relational practice. These supports, however, need to be informed by evidence. Further research is required to develop efficacious professional development opportunities specifically for educators to better help them engage with and maintain strong relationships with families within their ECE service.

To reposition the ECE service as a hub for integration of early childhood services within regional communities, consideration needs to be given to those features of the ECE context that should be prioritized and, more importantly, what we need to do to empower educators to respond to and support children experiencing challenge and vulnerability. It is well established that high quality ECE affords significant cognitive, social, and emotional benefits for children and that these benefits extend beyond the early years into adulthood (Melhuish et al., 2015; Taggart et al., 2015; Goldfeld et al., 2016). The potential for positive impact is further heightened among children who experience disadvantage, developmental and/or socioeconomic vulnerabilities (Cornelissen et al., 2018; Van Huizen and Plantega, 2018). These benefits, however, are reliant on the quality of practices, pedagogies and relationships to which children are exposed (Siraj et al., 2016; Van Huizen and Plantega, 2018; Siraj et al., 2022).

While the extent of influence of quality practice is witnessed most keenly among populations of children experiencing greater vulnerability, we also know these children are most vulnerable to poor quality practice. This presents a real and enduring concern within the current Australian ECE context where we see reduced access to quality ECE in communities characterized by higher social and economic disadvantage (Torii et al., 2017).

The challenge of providing children with high-quality ECE environments in regional settings is further complicated by increased stress on workforce in these areas, which includes the recruitment and retention of qualified staff, particularly degree-qualified early childhood teachers (Community Early Learning Australia, 2021). A model that prioritizes capacity building of staff in situ is necessary if we are going to position the ECE context as a key lever for enhancing child outcomes through quality practice, integrated service delivery and ECI partnerships. The findings from this study corroborate the broader literature in suggesting that such workforce empowerment may be supported through the professional development and upskilling of educators, particularly if we are to build a strong regional ECE workforce that possess the knowledge and skills to work in integrated ways with ECI services and professionals (Royal Far West, 2017; Moore, 2021).

Findings from the current study also highlight the benefits of connecting educators with contemporary research (including developmental science and early childhood pedagogy), and empowering them to implement evidence-informed practical strategies for supporting children and families within their services. These insights resonate with existing research (see Siraj et al., 2018, 2022) that speaks to the importance of professional learning targeting skills and knowledge, along with educator confidence and professional identity. Heightened knowledge and professionalism is essential for ensuring educators feel adequately placed to support and advocate for children and families experiencing vulnerabilities.

The model of educator empowerment through ongoing professional learning – adopted in the SESI study – was positioned as essential for ensuring educator capacity within regional settings, particularly given the limited allied health service support system, which translated to long wait times for diagnosis and early intervention. Service level interventions also have the potential to support children who may not require additional interventions beyond quality early education, or children whose circumstances dictate a lack of access to additional interventions (i.e., familial reluctance to access health or intervention services). Findings from the current study further suggest that this upskilling and capacity building of educators may support the retention of the early childhood workforce and combat staff frustration, burnout, and high rates of turnover, which remain a threat to the functionality of early childhood systems within regional communities (Community Early Learning Australia, 2021).

One evidence-based model that could be adapted to support early intervention and transdisciplinary models in regional contexts is the key worker model of service delivery (Clapham et al., 2017). This model is typically utilized within ECI services and involves the allocation of a single ECI professional (i.e., speech pathologist, occupational therapist, etc.) acting as a family’s key point of contact within a multidisciplinary team or across agencies (Kelly and Knowles, 2015). Findings from this study suggest that ECE services who had established relationships with a key ECI professional were better positioned to seek advice, provide internal supports within the ECE service, and support families to navigate referral pathways to ECI services. Having a key worker can also support collaboration and communication pathways between educators and ECI professionals to work in transdisciplinary ways, including the sharing of disciplinary knowledge, collaborating on intervention strategies, and sharing vital contextualized information specific to a child’s needs and family, social, or cultural context (Prichard et al., 2015; Moore, 2021).

Implementing an ECI professional key worker model within regional communities where ECI services are limited and fragmented, however, can present unique challenges. Evidence from the current study speaks to the potential benefits of a model where ECE services themselves embed a key worker role such that an ECE employee adopts the role of the early childhood family support, health, and intervention navigator. This role can support familial connections with health, community and ECI services, building a team around the child and fostering transdisciplinary collaboration between early childhood health and intervention professionals, educators, and families.

The significance of these findings needs to be understood within the limitations of the research design. The small sample size, a focus on regional contexts and the reliance of educator report, limits the generalizability of findings while highlighting the need for replication with a wider sample of ECE services. Given that community risk and complexity increase alongside geographic remoteness (Arefadib and Moore, 2017) future research should target models of integrative effectiveness in areas of greater need including rural and remote communities. While the current study prioritized the voice of the educator, a broader understanding of the complexities of service integration would benefit by including perspectives of other key system stakeholders including children, families, and ECHI professionals alongside objective measures of service usage.

Findings from the current study highlight a number of key features or components needed to ensure role effectiveness for an ECE navigator, including: (1) a commitment to forming relationships based on trust, collaboration, and strong communication with families and ECI services and professionals; (2) a willingness and ability to work in transdisciplinary ways in which all early childhood professionals, educators, and families are key members of the team around the child, and the child’s goals and needs are the focal point of all decisions and practice; and (3) a required knowledge of the family support, health, and ECI services available within the community, knowledge of the relevant access pathways to these services, and an ability to support families in navigating these pathways. The adaptation of this model within ECE settings may serve to alleviate educator frustrations around the time burdens placed upon them to support familial connections to outside services, resulting in what is often perceived as scope creep, taking educators away from their core business of educating young children.

As we move toward the development of models of service integration within early childhood contexts, we need to be considering different ways of working that reflect the unique needs and capacities of the communities in which children, families and services are embedded. In an ECE system that is underpinned by universal structures (i.e., consistent staff ratios, staff qualifications, common accreditation requirements and practice frameworks), there is a strong case to be made that we need to move toward a system that commits to a more differentiated model of funding and support, including further role differentiation within ECE (with concomitant professional supports). Such a model would include both a commitment to universal funding as a minimum requirement across all communities and service systems, supplemented with a universal+ model that caters for the disproportionate needs of communities where we witness higher rates of vulnerability and challenge. The ECE services involved in the current study would clearly have benefited from a universal+ model, which could encompass the inclusion of additional staff in the guise of an ECE navigator (outside standard ratios) to not only navigate the complexities of the support and funding system (i.e., NDIS funding) but also to ensure staff at the service could prioritize key learning opportunities that we know are essential for setting young children up for success.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Wollongong Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

CN-H and MR contributed to conception and design of the study. CN-H and JS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CN-H, JS, and KS-L analyzed the data. MR and CN-H read and edited all sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding for this project was provided by the Ian Potter Foundation [20180488].

The authors would like to acknowledge the vital contribution of the participating directors, educators, and early childhood intervention professionals within this study as well as the children and families attending these services. A special thank you is extended to the SESI reference group for their guidance and contribution to this project and to Alysha Calleia, Amanda Strudwick, Michelle Edwards, and Ana-Luisa Franco for their support in the collection of data and project management. Thank you also to the Ian Potter Foundation for funding and supporting this project from conception.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Arefadib, N., and Moore, T.G. (2017). Reporting the health and development of children in rural and remote Australia. The Centre for Community Child Health at the Royal Children’s hospital and the Murdoch Children’s research institute, Parkville, VIC. Available at: https://www.royalfarwest.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/MurdochReport.pdf

Australian Bureau of Statistics . (2016). Census of population and housing: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA) Australia, 2016. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~IRSD%20Interactive%20Map~15

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority . (2021). Guide to the national quality framework. Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. Available at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-03/Guide-to-the-NQF-March-2023.pdf

Australian Early Development Census . (2021). Australian early development census national report 2021. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Available at: https://www.aedc.gov.au/resources/detail/2021-aedc-national-report

Australian Government Department of Education . (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: the early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian government Department of Education for the ministerial council. Available at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf

Australian Government Department of Education and Training . (2018). Australian early development census (AEDC) Data Explorer. Available at: https://www.aedc.gov.au/data-explorer/

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . (2020). Australia’s children. Australian institute of health and welfare. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/childrenyouth/australias-children/contents/health/the-health-of-australias-children

Barnes, J., Crociani, S., Daniel, S., Feyer, F., Giudici, C., Guerra, J. C., et al. (2018). Comprehensive review of the literature on interagency working with young children, incorporating findings from case studies of good practice in interagency working with young children and their families in Europe. Report to the European Union under grant agreement no. 72706. European Union, Brussels. Available at: http://archive.isotis.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/D6.2.-Review-on-inter-agency-working-and-good-practice.pdf

Baxter, P., and Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 13, 544–559. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carpenter, C., and Suto, M. (2008). Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: a practical guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Clapham, K. F., Manning, C. E., Williams, K., O’Brian, G., and Sutherland, M. (2017). Using a logic model to evaluate the kids together early education inclusion program for children with disabilities and additional needs. Eval. Program Plann. 61, 96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.12.004

Community Early Learning Australia . (2021). CELA advocacy position may 2021: closing the gap for rural children. Available at: https://www.cela.org.au/CELA/how-help/advocacy/CELA-Advocacy-Position-May-2021-05.pdf

Cornelissen, T., Dustmann, C., Raute, A., and Schonberg, U. (2018). Who benefits from universal childcare? Estimating marginal returns to early childcare attendance. J. Polit. Econ. 126, 2356–2409. doi: 10.1086/699979

Eapen, V., Walter, A., Guan, J., Descallar, J., Axelsson, E., Einfeld, S., et al. (2017). Maternal help seeking for child developmental concerns: associations with socio-demographic factors. J. Paediatr. Child Health 53, 963–969. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13607

Goldfeld, S., O’Connor, E., O’Connor, M., Sayers, M., Kvalsvig, A., and Brinkman, S. (2016). The role of preschool in promoting children’s healthy development: evidence from an Australian population cohort. Early Child. Res. Q. 35, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.11.001

Hadley, F., and Rouse, E. (2018). The family-Centre partnership disconnect: creating reciprocity. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 19, 48–62. doi: 10.1177/1463949118762148

Kelly, L. M., and Knowles, J. M. (2015). The integrated care team: a practice model in child and family services. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 18, 382–395. doi: 10.1080/10522158.2015.1101728

Krakouer, J., Mitchell, P., and Trevitt, J. (2017). Early years transitions: supporting children and families at risk of experiencing vulnerability: rapid literature review. Victoria Government Department of Education and Training. Available at: https://research.acer.edu.au/early_childhood_misc/9/ (Accessed April, 2023).

McCormack, J. M., and Verdon, S. E. (2015). Mapping speech pathology services to developmentally vulnerable and at-risk communities using the Australian early development census. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 17, 273–286. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2015.1034175

Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Ariescu, A., Penderi, E., Rentzou, K., et al. (2015). A review of research on the effects of early childhood education and care (ECEC) upon child development. EU CARE project. Available at: https://ecec-care.org/fileadmin/careproject/Publications/reports/new_version_CARE_WP4_D4_1_Review_on_the_effects_of_ECEC.pdf (Accessed March, 2023).

Moore, T.G. (2021). Developing holistic integrated early learning services for young children and families experiencing socio-economic vulnerability. Prepared for social ventures Australia. Parkville, VIC: Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children's research institute, the Royal Children’s hospital

Moore, T, and Skinner, A. (2010). An integrated approach to early child development. The benevolent society. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290437771_An_Integrated_Approa ch_to_Early_Childhood_Development

Murphy, C., Matthews, J., Clayton, O., and Cann, W. (2021). Partnership with families in early childhood education: exploratory study. Austral. J. Early Childhood 46, 93–106. doi: 10.1177/1836939120979067

Neilsen-Hewett, C., and de Rosnay, M. (2017). The leadership for early education, development and advocacy (LEEDA) framework. Wollongong, Australia: University of Wollongong.

Neilsen-Hewett, C., Stouse-Lee, K., and Calleia, A. (2020). Supporting effective service integration (SESI) in regional and remote communities [Online Conference Presentation]. Charles Sturt University Early Childhood Voices 2020 Conference. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4eNCRLO4BLQ

Newman, S., McLoughlin, J., Skouteris, H., Blewitt, C., Melhuish, E., and Bailey, C. (2020). Does an integrated, wrap-around school and community service model in an early learning setting improve academic outcomes for children from low socioeconomic backgrounds? Early child development and care. Early Child Dev. Care. 192, 816–830. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2020.1803298

NSW Ministry of Health . (2019). The first 2000 days: Conception to age 5 framework. NSW Ministry of Health. Available at: https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2019_008.pdf

O’Connor, A., Nolan, A., Bergmeier, H., Williams-Smith, J., and Skouteris, H. (2018). Early childhood educators’ perceptions of parent-child relationships: a qualitative study. Austral. J. Early Childhood 43, 74–99. doi: 10.23965/AJEC.43.1.01

Press, F., Sumsion, J., and Wong, S. (2012). Integrated early years provision in Australia. Professional support coordinators Alliance. Bathurst: Charles Sturt University. Available at: https://childaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CSU-PSCA-Integrated-Services-Report_Final-1.pdf

Prichard, P., O’Byrne, M., and Jenkins, S. (2015). Supporting Tasmania’s child and family centres: The journey of change through a learning and development strategy. Hobart, Tasmania: Centre for Community Health

Roberts, W. (2017). Trust, empathy, and time: relationship building with families experiencing vulnerability and disadvantage in early childhood education and care services. Austral. J. Early Childhood 42, 4–12. doi: 10.23965/AJEC.42.4.01

Royal Far West . (2017). Supporting childhood development in regional, rural, and remote Australia. Available at: https://www.royalfarwest.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/RFW-Policy-Paper-Supporting-childhood-development-in-regional-and-rural-Australia-July-2017-V2.pdf

Royal Far West . (2018). The invisible children. Available at: https://www.royalfarwest.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The-Invisible Children-Report.pdf

Saunders, V., Beck, M., McKechnie, J., Lincoln, M., Phillips, C., Herbert, J., et al. (2022). A good start in life: effectiveness of integrated multicomponent multisector support on early child development – study protocol. PLoS One 17, 1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267666

Siraj, I., Kingston, D., Neilsen-Hewett, C. M., Howard, S. J., Melhuish, E., de Rosnay, M., et al. (2016). Fostering effective early learning: a review of the current international evidence considering quality in early childhood education and care programmes—in delivery, pedagogy and child outcomes. Sydney, Australia: Department of Education

Siraj, I., Melhuish, E., Howard, S., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Kingston, D., de Rosnay, M., et al. (2018). Fostering effective early learning (FEEL) study: Final report publication details. Sydney, Australia: NSW Department of Education

Siraj, I., Melhuish, E., Howard, S. J., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Kingston, D., De Rosnay, M., et al. (2022). Improving quality of teaching and child development: a randomised controlled trial of the leadership for learning intervention in preschools. Front. Psychol. 13:1092284. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1092284

Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Sammons, P., and Melhuish, E. (2008). Towards the transformation of practice in early childhood education: the effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project. Camb. J. Educ. 38, 23–36. doi: 10.1080/03057640801889956

Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., Sammons, P., Melhuish, E., Elliot, K., et al. (2006). Capturing quality in early childhood through environmental rating scales. Early Child Res. Q. 21, 76–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.01.003

Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., and Siraj, I. (2015). Effective pre-school, primary and secondary education project (EPPSE 3–16+): How pre-school influences children and young people's attainment and developmental outcomes over time. London, UK: Department of Education

Taylor, C. L., Jose, K., van de Lageweg, W. I., and Christensen, D. (2017). Tasmania’s child and family centres: a place-based early childhood services model for families and children from pregnancy to age five. Early Child Dev. Care 187, 1496–1510. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2017.1297300

Torii, K., Fox, S., and Cloney, D. (2017). Quality is key in early childhood education in Australia. Mitchell Institute paper no. 1/2017. Melbourne, Victoria: Mitchell Institute at Victoria University. Available at: http://www.mitchellinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Quality-is-key-in-earlychildhood-education-in-Australia.pdf

Van Huizen, T., and Plantega, J. (2018). Do children benefit from early childhood education and care? A meta-analysis of evidence from natural experiments. Econ Educ Rev 66, 206–222. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.08.001

Keywords: service integration, early childhood education, early childhood intervention, regional communities, developmental vulnerability, early childhood pedagogy

Citation: Neilsen-Hewett C, de Rosnay M, Singleton J and Stouse-Lee K (2023) Supporting service integration through early childhood education: challenges and opportunities in regional contexts. Front. Educ. 8:1220658. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1220658

Received: 11 May 2023; Accepted: 22 August 2023;

Published: 14 September 2023.

Edited by:

Waganesh A. Zeleke, Virginia Commonwealth University, United StatesReviewed by:

Louise Tracey, University of York, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Neilsen-Hewett, de Rosnay, Singleton and Stouse-Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cathrine Neilsen-Hewett, Y25oZXdldHRAdW93LmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.