- 1Department of Educational Science, University of Education Upper Austria, Linz, Austria

- 2Center for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 3Department of Management, Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria

- 4Department for Higher Education Research, Austria Center for Educational Management and Higher Education Development, Danube University Krems, Krems, Austria

- 5Department of Business Education and Development, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

- 6Department of Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Higher education institutions (HEIs) have been going through far-reaching processes of transformation in terms of their missions in teaching, research, and societal impact. Contrary to their previous understanding and mission, Austrian universities are now increasingly required to contribute evidence from research and teaching to meet social challenges and to cooperate with community partners. This forces an understanding of HEIs as a driver for social innovation and requires educational leadership on multiple levels. Overall, campus community partnerships (CCPs) emerge as a dimension of a new culture of cooperation between HEIs and civil society which includes individual, organizational and inter-organizational learning. As, CCPs basically depend on the individual efforts, ambitions and networks of faculty members and educators we raise the questions, (1) who takes the lead for their initiation and maintenance, and (2) to which degree these partnerships have been institutionalized and supported so far. These questions are discussed in the framework of their significance for educational leadership for the establishment of suitable framework conditions for the promotion of social innovation for CCPs. These questions are particularly of interest for the German speaking countries like Austria, since CCPs in this context still have little tradition across the higher education sector. In this brief research report, results from a recent survey (2022; N = 107) concerning the initiation, support structures and formalization of CCPs in Austrian HEIs are presented, and conclusions for educational leadership principles for CCPs are discussed.

1. Introduction

Higher education institutions (HEIs) have been going through far-reaching processes of transformation in terms of their missions in teaching and research extending these to the mission of reaching an increased societal impact and social change (Marullo and Edwards, 2000). In addition to their previous understanding as educational institutions educating students and bringing forth excellent research, HEIs are now increasingly required to contribute evidence from research and teaching to meet social challenges and to cooperate with community partners for these purposes. These cooperations occur on multiple levels (strategic management, middle management, faculty level, teaching level, student level, level of student organizations etc.) and to different degrees of institutionalization (formal cooperation, informal cooperation etc.). Successful cooperation of HEIs with external stakeholders as drivers for social innovation and societal impact – in any case – depends on responsible educational leadership on these multiple levels (Fassi et al., 2020). Today, multilevel analytics on educational governance, management, and leadership are common in educational leadership research, drawing on a variety of approaches and academic disciplines (Elo and Uljens, 2022). Nevertheless, leadership of teaching and learning (TL) still remains an understated topic in higher education (HE), and there is no common understanding of what educational leadership in HEI means. A current study conducting a systematic literature review on scholarly articles relating to leadership in Teaching and Learning (TL) in a HE context, published between 2017 and 2021, points out, that the distributed leadership approach claims to represent a solution to the general discontent with the dominant new public management model in academia (Kinnunen et al., 2023). Distributed leadership calls for a change in perspective, which would emphasize leadership as a collective activity, which envisions the entire community being involved in the work of leadership, and which enables analyses of engaging and participatory processes in HE institutions.

Overall, campus community partnerships (CCPs) emerge, for instance, in the German speaking countries (Austria, Germany, Switzerland) as a dimension of a new culture of cooperation between HEIs and civil society (Zeichner, 2010; Felten and Clayton, 2011). Defining CCPs is a complex task including some essential elements: a relationship characterized by mutuality or reciprocity, involving one or more individuals or groups from the academia and the community and a commitment to an agreed objective (Beere, 2009). Partnerships can be large, small-scale, focused on a single need or objective or serve multiple purposes. CCPs can be conducted with civil society organizations, social enterprises or public institutions – all serving a ‘real need’ in the institution or community (Resch et al., 2020). CCPs are initiated for the mutual benefit of all involved, such as exchange, knowledge application, or exploration, and should lead to “sustainable, productive, and meaningful relationships with community partners” (Kmack et al., 2022: 16). CCPs are influenced by a number of factors, such as campus size (large universities tend to have more supportive infrastructure and resources), type of the HEI (research universities tend to focus on research tasks more than teacher training colleges), and location of the HEI (those located in urban areas might have a more vivid campus life involving community partners) (Beere, 2009). These partnerships require different forms of leadership compared to research and teaching and new modes of learning on the individual, organizational and inter-organizational level (Fahrenwald and Fellner, 2023). As a form of research-practice transfer activities, CCPs contribute to organizational innovative practice (Martin et al., 2005) by involving civil society partner organizations in HEI’s missions and core activities.

Despite a considerable body of research on CCPs in HE system in the Anglo-Saxon countries (Fleming, 1999; Percy et al., 2006; Osafo and Yawson, 2019) so far, little is known about the institutionalization of the emerging CCPs in the HE system in the German speaking countries. Against this background, the questions arise (1) to which degree these partnerships have been institutionalized and supported by the HEIs so far and (2) who takes the lead for their initiation and maintenance. These questions are discussed in the framework of their significance for educational leadership for the establishment of suitable framework conditions for the promotion of societal impact and social change for CCPs. The purpose of this collaborative research project, conducted among several HEIs in Austria, is to map the current status quo of CCPs in Austrian HEIs to identify the ways in which educators receive institutional support in implementing these formats.

1.1. CCPs in the context of educational leadership in higher education

Within teaching, CCPs are more often represented in certain learning formats, which diverge from traditional lecture-based approaches to learning (engaged scholarship). Engaged scholarship can be viewed as a teaching format that relates to civic engagement involving campus-community partnerships (Harkins, 2013). This requires an understanding of active student learning, in which students actively strive to improve their learning through analysis and reflection. Students view themselves as active change agents, knowledge producers and co-creators of their own educational experience, rather than consumers of knowledge – as might be the case in traditional instruction-based courses (Darling-Hammond and Bransford, 2005; Harkins, 2013). In instruction-based approaches in higher education the educator acts as the main knowledge holder, however in engaged scholarship the role of educator changes from traditional instruction to guidance, counselling, and mentoring (Resch et al., 2022). Active learning involves more interactive, discussion-based and field-oriented learning (Harkins, 2013) and civic engagement provides diverse forms of active learning through community engagement. This form of teaching is supported by a general didactic shift from lecture-based approaches to more self-directed and open learning formats in higher education in recent years (Zeichner, 2010). Approaches, which function well with the involvement of community partners and in turn require well-functioning CCPs, are first and foremost service learning (Felten and Clayton, 2011), but also community-based learning or research. These teaching formats, however, do pose certain challenges to educators, who need to organize and manage these community partnerships accordingly. CCPs often depend on the individual efforts, ambitions and networks of faculty members and educators (Resch and Dima, 2021). Community-based research and service-learning are application-oriented and experience-based learning formats that ultimately aim at enhancing students’ sense of civic responsibility (Bringle and Hatcher, 1995; Felten and Clayton, 2011).

Based on the common value of working together in engaged scholarship, academics and community partners enter more or less formal partnerships pursuing a common goal (Levkoe and Stack-Cutler, 2018). CCPs can be viewed as relationships between community partners and HEIs that follow several phases: relationship initiation, development and maintenance, sustainable relationships or dissolution of relationships (Bringle and Hatcher, 2002). The degree of institutionalization of CCPs strongly depends on the educational leaders initiating the partnerships (Levkoe and Stack-Cutler, 2018). The most extensive body of research exists for the service learning approach as one form of engaged scholarship (Harkins, 2013). The exponential growth of service learning in the last years in Europe and in Austria as well are clear indicators for a renewed emphasis on CCPs in higher education leadership, policy, and practice (Resch et al., 2020).

Furco (2003) and Kecskes (2013) identify three stages of sustainable institutionalization of service-learning activities. In the first stage (critical mass building), the campus begins to recognize service learning and build a network of actors. Initial efforts are made to create an appropriate foundation for the implementation of service learning; at this stage the service-learning concept is not clearly defined and is used inconsistently to define a variety of community-oriented activities. In the second stage (quality building) the campus focuses on developing ‘high quality’ community-based activities and expands the network to include these activities. Service-learning components are often perceived as an important part of the university mission, although they are not officially included in the mission statement or strategic plan. In the third stage (sustained institutionalization), the campus has fully integrated community-based learning into the culture and structure of the institution. This stage is characterized by an internalization of service learning in the academic culture. The needs of community partners are identified and aligned with the learning objectives of the HEI.

At the stage of critical mass building, CCPs may be a leadership response to an invitation to engage or may be initiated by lecturers, faculty members on behalf of the universities (e.g., in forums, study circles, or applied coursework) or the community partners (e.g., in local gatherings or moderated community dialogues) (Fear, 2010). CCPs can be carried out on an isolated basis – based on the decision of individual lecturers within the framework of their courses, projects or activities with students – or on a coordinated basis – as a joint effort of various institutes or faculties together with civil society actors (dispersed versus coordinated model; Mulroy, 2004). Isolated CCPs can also take place in the context of curricular and extracurricular university activities such as volunteer programs. While the differences between these teaching/learning methods are not always clear (Harkins, 2013; Resch, 2021), they are in any case intended to support students’ experiential, applied, and transdisciplinary learning. In this regard, “coordinated” CCPs exhibit an institutionalized form that requires supportive internal higher education structures. These offer a contact point for practice partners over a longer period of time or permanently (e.g., in the form of a coordinating office for non-university cooperation, an entrepreneurship program or a volunteer center; Butterfield and Soska, 2004).

Facilitators play an essential role as educational leaders in CCPs. Facilitators can be individuals or institutional leaders which promote CCPs. According to Tennyson (2005), there are internal and external facilitators, individual or team facilitators, and proactive and reactive facilitators in the context of CCPs. Internal facilitators work within the partner institution (either HEI or community) and are responsible for preparing the CCP and managing various aspects of the partnership. External facilitators are contracted to set up CCPs and build capacity in this area. Both individuals or teams can act as facilitators in CCPs. Proactive facilitators build partnerships, while reactive facilitators coordinate existing partnerships within a HEI or community. Although facilitators are heterogenous in their motivation, mandate, target groups, and organizational background, they do share commonalities and power to establish and support or disrupt and dissolve CCPs. Facilitators are likely to take over a range of roles in the partnerships between HEI and communities, and a strong role in sustaining partnerships if they are employed over a longer period of time to overcome constraints of lecturers posed by the academic schedule (Levkoe and Stack-Cutler, 2018). Levkoe and Stack-Cutler (2018) identify community-based facilitators, university-based facilitators, resource-based facilitators (dependent on funding bodies) and professional facilitating networks. The later might have a broader network of partnerships or matching opportunities at hand but might not be able to engage in a deeper partnership involving decision-making depending on the topic.

These questions are particularly of interest for Austria, since CCPs in the context of teaching still have little tradition across the higher education sector. This requires both a national and comparative approach to analyzing the state-of-the art of CCPs in the four different types of higher education institutions in Austria.

1.2. CCPs in the Austrian higher education context

Austria’s higher education system consists of 74 HEIs separated in four sectors with a different approach and tradition towards CCPs. According to the Universities Act from 2002 (§ 3 Abs 8 UG), Public Universities (22) are not understood as entities isolated from society; instead, the Universities Act emphasizes their active role and contribution to society. The focus of Universities of Applied Sciences (21) lies on study programmes and societal impact is less in the focus of the institutions. CCPs with institutions relevant to students’ later professional life are nevertheless common. Universities of Education (14) frequently conduct CCPs with schools and other educational stakeholders (Resch et al., 2022).

2. Methodology

2.1. Rationale

The research project advances the state-of-the-art on (1) how CCPs emerge within HE in Austria and (2) to what extent they are institutionalized, (3) the degree to which CCPs still depend on the educators’ social and professional networks, (4) the relevance of CCPs for HEI management and Third Mission, and (5) differences in the emergence and degree of institutionalization between the various types of HEIs and HE systems in Austria.

2.2. Instrument

The online survey consisted of 70 questions regarding different themes, such as the initial motivation for CCPs, significance and support structures at the universities, as well as the concrete conditions of the formation and implementation of the respective partnerships. The survey addressed educators’ perspectives on CCPs, their initial motivation, the emergence and implementation of CCPs, the number of CCPs per course/program, as well as other characteristics like duration, frequency and pattern of the interaction with students. Additionally, the survey collects data on the course/program itself (type, credits, form of evaluation etc.) and the educators’ profile (status, qualification, experience with Service-Learning etc.). The items of the instrument were developed in orientation on existing questionnaires from German data on Service Learning and was validated in different feedback-loops cooperating with transnational experts.

2.3. Data collection and sample

From spring to autumn 2022, the online survey was conducted with educators in all four above mentioned higher education sectors in Austria. The invitation to participate in the survey, with a short introduction and an online link/QR code, was sent via email to institutional contacts and highly involved educators, asking them to spread the mail (snowballing) to other educators who might be applying CCP. Additionally, educators were contacted according to their teaching profile based on an extensive desk research. In total, findings from N = 107 educators who participated in the survey and stated actively collaborating with community partners within the framework of their courses in the academic year 2021/22 were used for the current study.

2.4. Data analysis

After data collection and data clearance, the descriptive analysis gave an overview about the perspective of educators working and implementing CCP in their teaching. The focus of the analysis was to get more information and insights about the different forms and the amount of support which these educators perceive from their HEIs. Additionally, the socio-demographical data from the educators were compared with official data available from higher education reports by Statistic Austria. This enables to find out about the characteristics and particularities of educators working with CCP and how they might distinguish from other educators. Based on the results of the descriptive analysis and the distribution of educators’ answers the level of the institutionalization of CCP at Austrian HEIs was identified.

3. Results

The findings of the mapping provide insight about the dissemination and institutionalization of CCPs in Austria as well as about the role of educational leaders within this process.

3.1. Characteristics of the educators applying and leading CCPs

The educators applying and leading CCP in their teaching have mostly reached an academic mid-level: in terms of their highest completed education, 35% of the respondents have a master’s or diploma degree and 41% have a doctorate. Forty-nine percent of the educators are between 40 and 54 years old. Women are overrepresented in the survey with a share of 61% compared to the population of all university educators in Austria (43% women, 57% men). Among those respondents (N = 51) who report cooperation with community partners in higher education teaching for the academic year 2020/21, the proportion of women is also above average at 61%. In the context of leadership this means, that leadership and the responsibility for CCPs is often a female phenomenon on a post-doc level.

3.2. Degree of institutionalization and support of CCPs

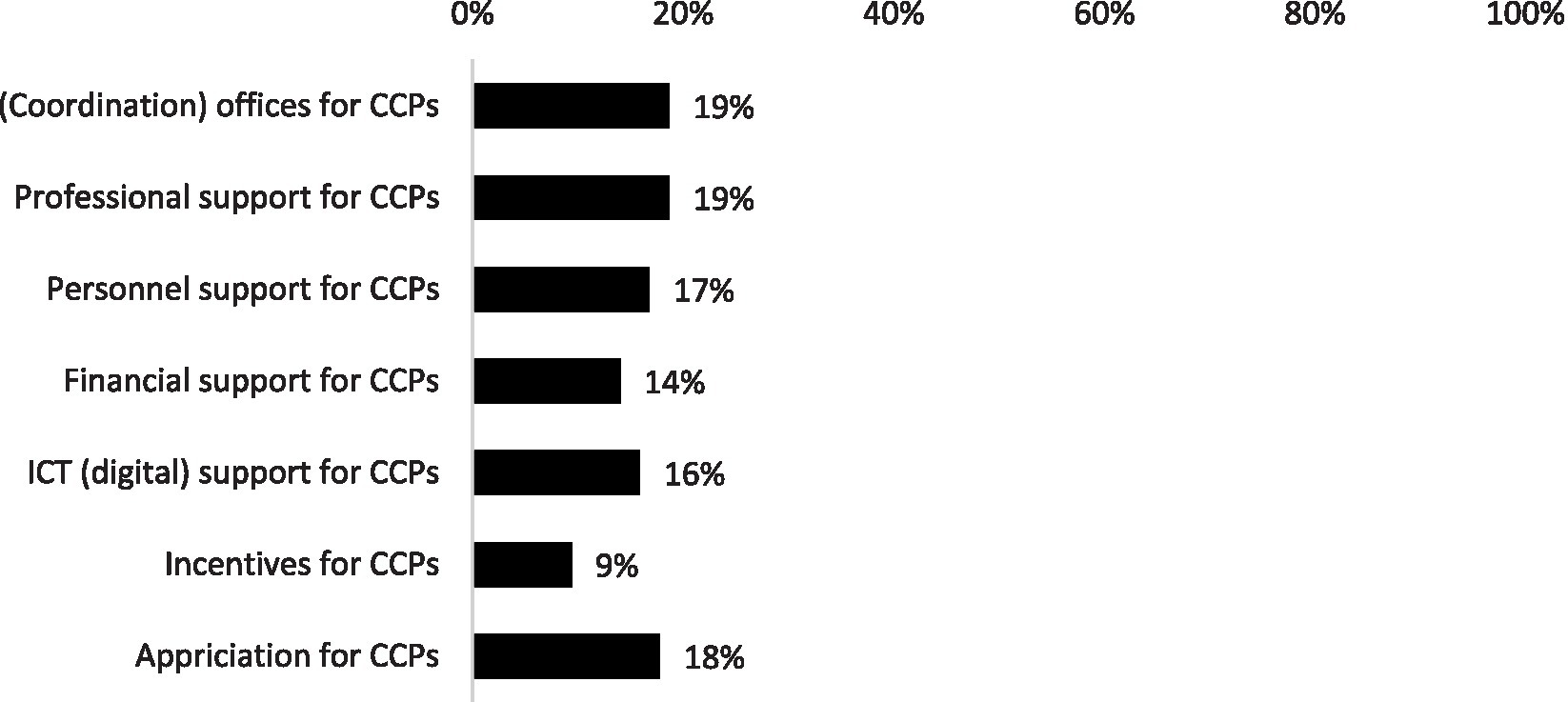

The answers of the educators specifically about the available support services for planning and implementing cooperation with community partners in the context of teaching clearly show that these have not been established yet or are hardly perceived as such. Less than one fifth (19%) of the respondents’ state that there is a coordination office for one or more forms of CCPs, such as for service learning or community service, at their HEI. Likewise, 19% refer to professional support in the design and planning of CCPs via training courses offered by the HEI. Only between 14 and 17% report institutionalized forms of support for the initiation and implementation of CCPs, such as personnel, financial and digital support. Around 20% of respondents are currently unable to provide any information on support structures. Only 18% of the educators perceive some kind of recognition by the university for their cooperation with community partners (Figure 1).

Around 53% of the respondents state that their HEI does not provide any of the above-mentioned support services (no institutionalization). Thirty-one percent report one or two institutionalized support services at their HEI (low institutionalization). For 12% of the respondents, three to four different offers are available (medium institutionalization). Only 4% state, that their HEI offers comprehensive institutionalized support for CCPs. Overall, these results are an initial indicator of a currently still barely to very low degree of institutionalization of CCPs at Austrian HEIs. Acting as an Educational Leader in HEIs the educators do not seem to be extensively supported in their efforts and the process of initiating CCPs from their institutions. This kind of leadership focusing on societal transformative developments is not located on a system level, or an organizational level but rather on the individual efforts of engaged scholars. As a consequence, this implies a high responsibility of the single educator. We must assume that informal networks between educators in the same scientific area may exist. But nevertheless, on the institutional level, educators’ actions and cooperations in CCPs are not systematically coordinated between each other or concerted.

3.3. Engaged scholarship in the context of CCPs

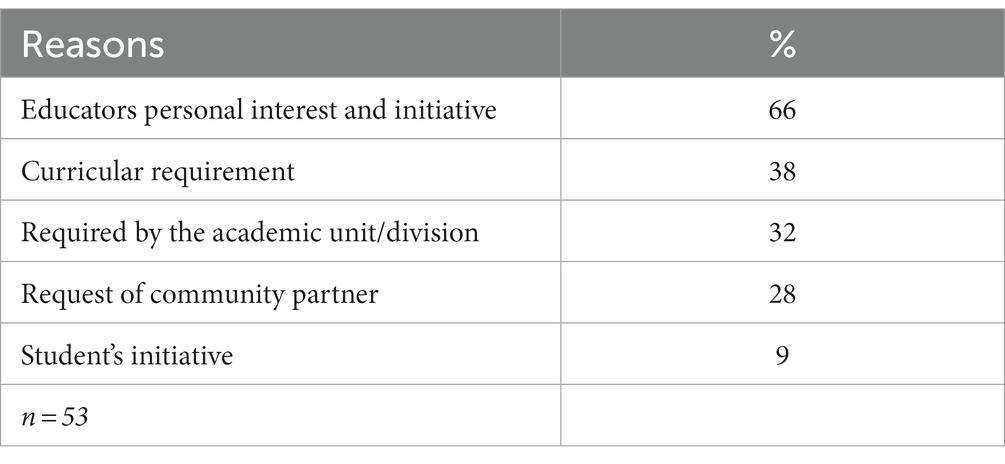

At the level of educators’ courses (n = 53), the main question is, how CCPs are initiated, and which actors play a significant role. In the majority (66%) of the courses, cooperations with community partners were initiated on the basis of personal interest and the educators’ own initiative and personal contact. Requirements in the curriculum or by the academic unit were given as the decisive reason for cooperation in only one third of the cases. About a quarter of the educators’ report that the cooperation is due to requests from the community partners. In comparison, for only 9%, the collaboration is due to the initiative of students. In this case, students seem to be involved in the decision and selection of community partners only in individual cases and there is no institutionalized practice in this regard (Table 1).

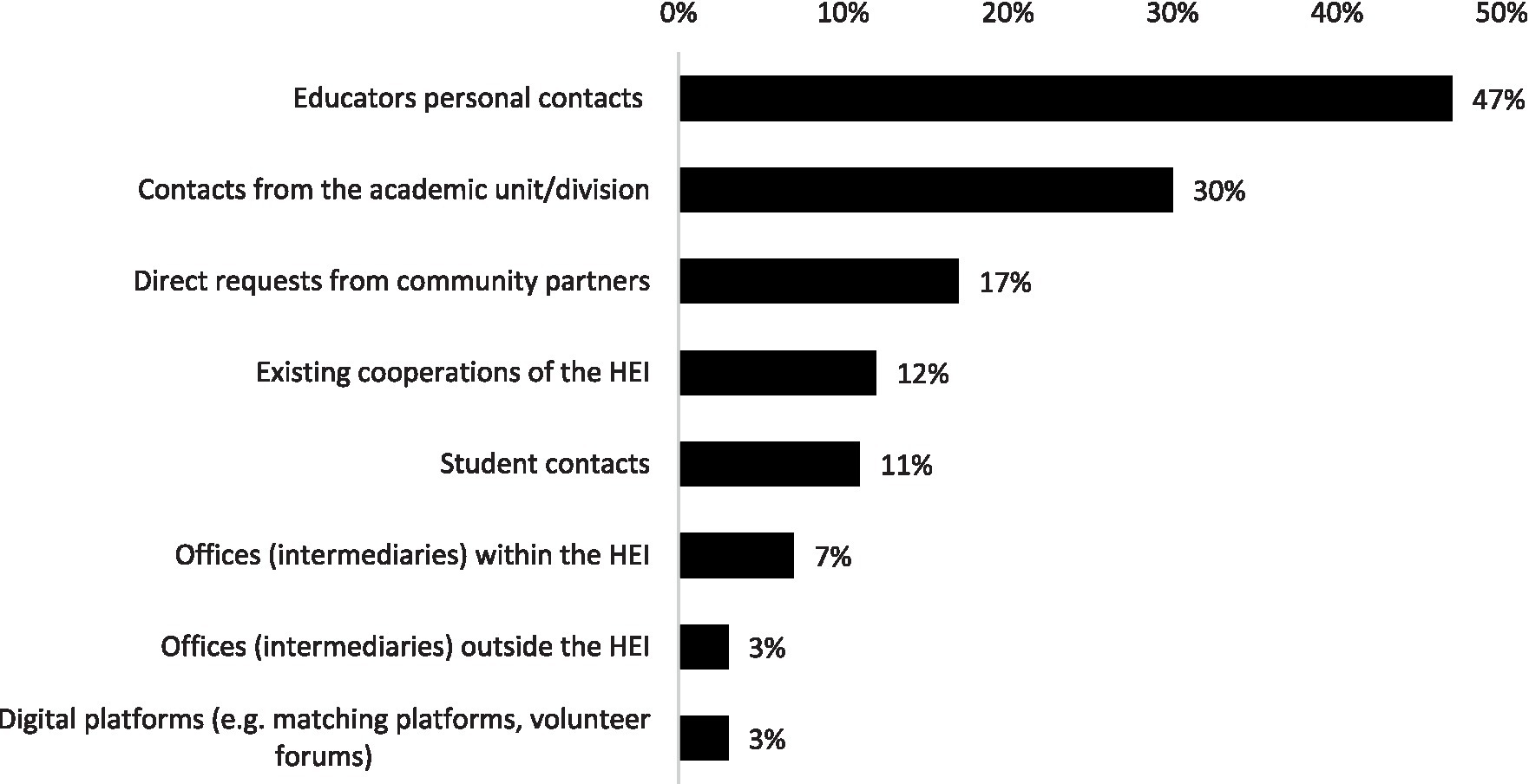

This perspective is similar looking at the selection of community partners. The initial first-time contact is attributed to the personal acquaintance of the educator in charge (around 47% agree) and to existing contacts of the academic unit/department (around 30% agree). On the other hand, selection based on direct requests by community partners (around 17% agree) or established cooperation at the HEI (around 12% agree), but also on student initiative (around 11% agree) are mentioned much less frequently (Figure 2).

Placement offices and digital platforms seem to play a marginal role so far. These findings add additional support to our hypothesis, that most commonly, educators initiate, organize and manage CCPs and therefore serve as primary CCPs leaders.

4. Discussion

The empirical results show that CCPs have not been institutionalized at Austrian HEIs so far; instead, the personal interest and commitment of educators as well as their contacts form the starting point and the basis for CCPs in higher education teaching. Only one fifth of the practicing educators receive some form of support for courses of this kind and only about 12% of the educators agree to cooperate based on already existing partnerships. Beside mentions of third mission activities in the HE mission statements (Resch et al., 2020), HEIs in Austria still lack official support structures for CCPs (cf. Mugabi, 2015). There is a high proportion of educators (over 75%) practicing CCP who themselves have experience in volunteering and voluntary work, and thus established contacts with civil society organizations. Voluntary work outside the HEIs thus seems to increase the likelihood of CCPs in teaching, whereby educators predominantly belong to the academic middle class (postdoc phase without habilitation and post-doctoral phase). From this part, educators’ own volunteering experience and their personal contacts are highly important for the initiation and integration of CCPs in their teaching. In this sense, the data indicates that mostly educators are taking the lead for CCPs. Nevertheless, to further increase the societal impact and utilize CCPs full potential, educational leaders need support in a twofold way. First of all, institutionalized support structures for CCPs should be established at all HEIs to disburden educators in terms of organizing and managing CCPs and institutional reward systems need to be changed (Marullo and Edwards, 2000). Second, educators leading CCPs should be trained and facilitated to become transformative leaders and serve as societal change agents to promote social innovation in education (Fahrenwald et al., 2021).

In the face of current societal challenges, both communities and HEIs may struggle to mobilize collective action, hence, leadership in this context means producing direction and cultivating collective capacities for action, such as CCPs (Kliewer and Priest, 2019). CCPs have, in principle, the potential for broader participation in social transformation processes (Marullo and Edwards, 2000); however, the establishment of CCPs, but also preparation and implementation of partnerships usually require a lot of resources. Cooperation between HEIs and community partners has so far been linked primarily to educators’ interest or commitment. In this respect, support services must be designed in a way that a culture of participation is sustainably promoted and institutionally anchored. Since partnerships between HEIs and community partners are in Austria predominantly “bottom-up” initiatives of the educators, it is, on the other hand, important to reflect on which unintended side effects might be associated with an extended regulation by leaders of the higher education institution (“top down”) and to what extent this would mean a loss of empowerment and freedom for the educators as leaders.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

CF, KR, PR, MF, PS-Z and MK contributed all to the conception and design of this article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Beere, C. (2009). Understanding and enhancing the opportunities of community-campus partnerships. N. Dir. High. Educ. 2009, 55–63. doi: 10.1002/he.358

Bringle, R. G., and Hatcher, J. A. (1995). A service-learning curriculum for faculty. Michigan J. Community Serv Learn Fall 1995, 112–122.

Bringle, R. G., and Hatcher, J. A. (2002). Campus- community partnerships: the terms of engagement. J. Soc. Issues 58, 503–516. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00273

Butterfield, A. K., and Soska, T. M. (2004). “University-community partnerships: an introduction” in University-Community Partnerships. Universities in Civic Engagement. eds. T. M. Soska and A. K. Butterfield (New York and London: Routledge), S1–S11.

Darling-Hammond, L., and Bransford, J. (2005). Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers Should Learn and Be Able To Do. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Elo, J., and Uljens, M. (2022). Theorising pedagogical dimensions of higher education leadership—a non-affirmative approach. High. Educ. 85, 1281–1298. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00890-0

Fahrenwald, C., and Fellner, M. (2023). “Hochschulen optimieren durch gesellschaftliches engagement? (Inter-) organisationale lernherausforderungen am Beispiel von Service Learning” in Organisationen Optimieren? Jahrbuch der Sektion Organisationspädagogik. eds. S. M. Weber, C. Fahrenwald, and A. Schröer (Wiesbaden: VS Springer (In Print)).

Fahrenwald, C., Kolleck, N., Schröer, A., and Truschkat, I. (2021). Editorial: “social innovation in education”. Front. Educ. 6:761487. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.761487

Fassi, D., Landoni, P., Piredda, F., and Salvadeo, P. (Eds.) (2020). “Universities as drivers of social innovation” in Theoretical Overview and Lessons from the "campUS" Research (Cham: Springer).

Fear, F. A. (2010). “Coming to engagement: critical reflection and transformation” in Handbook of Engaged Scholarship: Contemporary Landscapes, Future Directions. Volume Two, Community-Campus Partnerships. eds. H. E. Fitzgerald, C. Burack, and S. D. Seifer (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press), 479–492.

Felten, P., and Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2011, 75–84. doi: 10.1002/tl.470

Fleming, J. J. (1999). A Typology of Institutionalization for University-Community Partnerships at American Universities and an Underlying Epistemology of Engagement. University of California, Berkeley.

Furco, A. (2003). Self-Assessment Rubric for the Institutionalization of Servicelearning in Higher Education. Providence, RI: Campus Compact.

Harkins, D. A. (2013). Beyond the Campus: Building a Sustainable University-Community Partnership. Charlotte, N.C: Information Age Publications.

Kecskes, K. (2013). “The engaged department” in Research on Service Learning: Conceptual Frameworks and Assessment: Communities, Institutions, and Partnerships. eds. P. H. Clayton, R. G. Bringle, and J. A. Hatche (Sterling: Stylus) vol. 2, 471–504.

Kinnunen, P., Ripatti-Torniainen, L., Mickwitz, Å., and Haarala-Muhonen, A. (2023). Bringing clarity to the leadership of teaching and learning in higher education: a systematic review. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-06-2022-0200

Kliewer, B. W., and Priest, K. L. (2019). Building collective leadership capacity: lessons learned from a university-community partnership. Collab. J. Community Based Res. Pract. 2, 1–10. doi: 10.33596/coll.42

Kmack, H., Pellino, D., and Fricke, I. (2022). Relationship, leadership, action: evaluating the framework of a sustainable campus-community partnership. Community Dev., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2022.2109700

Levkoe, C. Z., and Stack-Cutler, H. (2018). Brokering community-campus partnerships: an analytical framework. Gateways 11, 18–36. doi: 10.5130/ijcre.v11i1.5527

Martin, L. L., Smith, H., and Phillips, W. (2005). Bridging “town & gown” through innovative university-community partnerships. Innov. J. 10, 1–16.

Marullo, S., and Edwards, B. (2000). From charity to justice: the potential of university-community collaboration for social change. Am. Behav. Sci. 43, 895–912. doi: 10.1177/00027640021955540

Mugabi, H. (2015). Institutional commitment to community engagement: a case study of Makerere University. Int. J. High. Educ. 4, 187–199. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v4n1p187

Mulroy, E. A. (2004). “University civic engagement with community-based organizations: dispersed or coordinated models?” in University-Community Partnerships. Universities in Civic Engagement. eds. T. M. Soska and A. K. Butterfield (New York and London: Routledge), 35–52.

Osafo, E., and Yawson, R. M. (2019). The role of HRD in university–community partnership. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 43, 536–553. doi: 10.1108/EJTD-12-2018-0119

Percy, St, Zimpher, N., and Brukardt, M.J. (2006). Creating a New Kind of University: Institutionalizing Community-University Engagement. Bolton, MA: Anker.

Resch, K. (2021). “Praxisrelevanz der Hochschullehre durch den Service-Learning-Ansatz und andere praxisorientierte Methoden stärken” in Rigour and Relevance: Hochschulforschung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Methodenstrenge und Praxisrelevanz. eds. A. Pausits, R. Aichinger, M. Unger, M. Fellner and B. Thaler (Hrsg.). (Studienreihe Hochschulforschung Österreich. Münster: Waxmann Verlag) S. 131–144.

Resch, K., and Dima, G. (2021). “Higher education teachers’ perspectives on inputs, processes, and outputs of teaching service learning courses” in Managing Social Responsibility in Universities. eds. L. Tauginienė and R. Pučėtaitė (London: Palgrave Macmillan)

Resch, K., Fellner, M., Fahrenwald, C., Slepcevic-Zach, P., Knapp, M., and Rameder, P. (2020). Embedding social innovation and service learning in higher Education’s third sector policy developments in Austria. Front. Educ. 5, 1–5. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00112

Resch, K., Schrittesser, I., and Knapp, M. (2022). Overcoming the theory-practice divide in teacher education with the ‘partner school programme’. A conceptual mapping. Eur. J. Teach. Educ., 1–17. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2022.2058928

Tennyson, R. (2005). The Brokering Guidebook: Navigating Effective Sustainable Development Partnerships. The International Business Leaders Forum (IBLF), England. Available at: https://thepartneringinitiative.org/publications/toolbook-series/the-brokering-guidebook/ (Accessed August 01, 2022).

Keywords: higher education, societal impact, campus-community-partnerships, educational leadership, engaged scholarship, transformation

Citation: Fahrenwald C, Resch K, Rameder P, Fellner M, Slepcevic-Zach P and Knapp M (2023) Taking the lead for campus-community-partnerships in Austria. Front. Educ. 8:1206536. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1206536

Edited by:

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United StatesReviewed by:

Michael Göhlich, University of Erlangen Nuremberg, GermanyKerry Renwick, University of British Columbia, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Fahrenwald, Resch, Rameder, Fellner, Slepcevic-Zach and Knapp. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claudia Fahrenwald, Y2xhdWRpYS5mYWhyZW53YWxkQHBoLW9vZS5hdA==: Katharina Resch, a2F0aGFyaW5hLnJlc2NoQHVuaXZpZS5hYy5hdA==

Claudia Fahrenwald

Claudia Fahrenwald Katharina Resch

Katharina Resch Paul Rameder

Paul Rameder Magdalena Fellner

Magdalena Fellner Peter Slepcevic-Zach

Peter Slepcevic-Zach Mariella Knapp

Mariella Knapp