- Faculty of Education, Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax, NS, Canada

This study examined the contributions of morphological awareness, listening comprehension, and early gains in word reading fluency to later outcomes in word- and text-reading fluency. There were 83 participants in second and third grade who were followed across 18 months. Gains in word reading fluency across the first six months predicted both word- and text-reading fluency one year later, beyond variance accounted for by initial word reading fluency, phonological awareness, rapid naming, and two oral language skills. Initial morphological awareness predicted reliable additional variance in word- and text-reading fluency 18 months later. The contribution of listening comprehension was specific to outcomes in text reading fluency. In the last analyses, listening comprehension, but not morphological awareness, predicted unique variance in final text reading fluency beyond final word reading fluency. Findings are discussed in terms of the developmental time-course of reading fluency and the roles of the two oral language skills examined.

Introduction

A hallmark of skilled reading is the automatic recognition of words as one reads passages (Stanovich, 2000). This seemingly effortless word reading frees cognitive resources for the more attention demanding, meaning-making cognitive activities involved in comprehending texts (LaBerge and Samuels, 1974; Perfetti, 2007). Text reading fluency, defined here as the accuracy and rate of reading sentences and passages (see also, Kim, 2015; Kim et al., 2021), has been shown to contribute to individual differences in reading comprehension for typically developing young readers (e.g., Kim et al., 2021) and for those with reading disabilities (e.g., Torgesen and Hudson, 2006; Metsala and David, 2022). Models of text reading fluency and its development, in turn, highlight a critical role for word reading fluency, the accuracy and speed of reading words in a list format (e.g., Klauda and Guthrie, 2008; Hudson et al., 2009, 2012; Norton and Wolf, 2012). Comprehensive models of reading fluency have also proposed a role for linguistic processes, such as morphological awareness and listening comprehension (e.g., Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001; Hudson et al., 2009; Kim, 2015; Kirby and Bowers, 2017).

Verbal efficiency theory identified both accuracy and rate as instrumental to word reading fluency (Perfetti, 1988). Theories of word reading development delineate how readers acquire this efficient word reading over time, with a focus on early phonological decoding skills and then on the increasingly internalized orthographic representations of words and word parts (Ehri, 1998, 2014; Share, 2008). Word reading fluency has been reported to be the single largest contributor to text reading fluency for typically developing and impaired readers (Torgesen et al., 2001; Torgesen and Hudson, 2006; Hudson et al., 2012). A considerable body of research has focused on the association between phonological awareness and rapid naming in the development of word reading fluency (e.g., Papadopoulos et al., 2016; Landerl et al., 2019). There has been less research on a potential role for oral language skills in the development of word- and text-reading fluency (Shechter et al., 2018; Manolitsis et al., 2019); therefore, the contributions proposed in some models have not been adequately tested.

Several questions concerning reading fluency and the skills that contribute to it in the early elementary grades remain largely unanswered. Kim (2015) suggested that some emergent skills studied in the context of reading development may contribute uniquely to word reading fluency and others to text reading fluency. Furthermore, the developmental time-course of stable individual differences and continuing malleability in reading fluency is not well delineated. One goal of this study is to test whether gains in word reading fluency across six months of second and third grade, predict word- and text-reading fluency outcomes one year later, beyond initial word reading fluency and several literacy related skills. A second goal is to examine whether morphological awareness and listening comprehension at study outset, predict variance in word- and text-reading fluency 18 months later, beyond initial word reading fluency and reading-related skills.

The role of early skill and gains in word reading fluency to later fluency outcomes

Word- and text-reading fluency increases sharply following students’ entry into second and third grade (Hasbrouck and Tindal, 2017). This steep incline for typical readers has been proposed as one reason why readers with dyslexia remain woefully behind in fluency, even when remediation closes achievement gaps in accuracy and comprehension (Torgesen and Hudson, 2006; Metsala and David, 2017). The window for getting readers who struggle back on a solid trajectory for word- and text-reading fluency appears to close early, perhaps as early as the first couple years of elementary school (Juel, 1988; Torgesen et al., 2001). It seems important then, to understand the contribution of individual differences in word reading fluency beyond grade 1 to later fluency outcomes. A critical question is whether fluency trajectories are more or less consolidated quite early for developing readers, or whether there are significant individual differences in continuing gains in word reading fluency that affect later fluency outcomes. In a somewhat related approach, Petscher and Kim (2011) reported that growth rates in oral reading fluency across first grade accounted for the most variance in third grade reading comprehension; however, when these students were in grades 2 and 3, the strongest relationship to third grade comprehension was their initial status in oral reading fluency, rather than growth. Although they examined comprehension outcomes, their study supports the notion that critical individual differences in fluency may be solidified quite early in reading acquisition. The current study set out to investigate whether gains in word reading fluency over roughly six months of second and third grade account for individual differences in word and text fluency one year later, beyond variance accounted for by initial word reading fluency and by several additional reading-related skills.

Morphological awareness and reading fluency

The role of foundational language skills has been emphasized in multicomponent models of reading comprehension; for example, the Reading Systems Framework recognizes that knowledge of vocabulary, syntax, and morphology directly influence comprehension processes, such as the readers’ construction of mental models (Perfetti and Stafura, 2014; Stafura and Perfetti, 2017; for a focus on morphology, see Levesque et al., 2021). Alongside orthography and phonology, comprehensive models of reading fluency have proposed additional roles for semantic, syntactic, and morphological knowledge systems (Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001; Hudson et al., 2009, 2012; Kim, 2015). One focus of the current study is on morphological awareness, an individuals’ ability to recognize and manipulate the smallest meaningful units in words (Carlisle, 2000). Findings have been relatively consistent concerning the unique contribution of morphological awareness to word reading accuracy (e.g., Kirby et al., 2012; cf. McBride-Chang et al., 2005) and reading comprehension (e.g., Deacon and Kieffer, 2018; Metsala et al., 2021). Theoretical models also propose a role for morphological awareness in word- and text-reading fluency. Awareness of morphemes is implicated in interactive models for which word reading fluency is a result of connections among orthographic, phonological and semantic representations (Seidenberg and McClelland, 1989; Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001). Moreover, morphological awareness may play a role in text reading fluency as one component of top-down linguistic influences potentially related to spreading activation facilitating reading sentences and passages (Hudson et al., 2009).

Despite these theoretical accounts, findings have been somewhat inconsistent in examinations of the associations between individual differences in morphological awareness and word reading fluency. Consider findings concerning the prediction of concurrent skills. Morphological awareness did not predict unique variance in first- and second-grade students’ concurrent English word reading fluency with phonological awareness also in the equation (Apel et al., 2013). In contrast, other studies reported that morphological awareness predicted unique variance in concurrent English word reading fluency for first or third grade students, also with phonological awareness controlled (Kirby et al., 2012; Manolitsis et al., 2019).

Similar inconsistencies are found in longitudinal research across these early elementary school years. Students’ fall morphological awareness predicted unique variance in spring word reading fluency for second grade English and French readers, with phonological awareness and rapid naming controlled, but this was not the case for young readers in Greek (Desrochers et al., 2018; see also, Georgiou et al., 2008; Diamanti et al., 2017; Giazitzidou et al., 2023 for similar findings with young Greek students; cf. Giazitzidou and Padeliadu, 2022). Kirby et al. (2012) also found that morphological awareness predicted English word reading fluency for students followed from second to third grade; although the relationship from first to third grade was not significant, as was the case for younger readers learning to read in Korean (Kim, 2015).

Only a handful of studies have controlled for initial word reading fluency in this literature. For English (but not for Greek) readers, morphological awareness at the end of grade 2 predicted word reading fluency at the beginning of grade 3 beyond initial word reading fluency and the other controls in the model (Manolitsis et al., 2019); however, even for the English readers in this sample, unique contributions to word reading fluency were not supported from the end of grade 1 to beginning of grade 2, nor across the grade 2 academic year. Similarly, morphological awareness did not account for unique variance in Greek word reading fluency from first to second grade after controlling for either initial word reading fluency or for several other reading related skills (Manolitsis et al., 2017).

Theoretical models also propose a role for morphological awareness in text reading fluency (e.g., Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001), but little research has examined this directly (cf. Kirby et al., 2012; Kim and Wagner, 2015). Kirby et al. (2012) found that grade 2 morphological awareness predicted variance in third grade text reading fluency. For young children learning to read in Korean, morphological awareness did not predict text reading fluency one year later, with initial word reading fluency and other reading related skills in the model (Kim, 2015).

Inconsistent findings concerning the association between skills and reading may be explained, in part, by the nature of the orthographic system under investigation (Ziegler et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2022). Morphological awareness appears to play a more prominent role in word reading fluency in English and similar relatively opaque orthographies than in more transparent orthographies (Shechter et al., 2018). However, as reviewed here, inconsistencies remain among studies on learning to reading in English, the language examined in the current study. Furthermore, while longitudinal studies have routinely controlled for phonological awareness, there is less consistency for including initial word reading fluency or rapid naming; the former allows a look at gains over a specified period of time and, the later has been shown to be uniquely associated with word reading fluency (e.g., Wolf and Bowers, 1999; Shechter et al., 2018; Landerl et al., 2019). Given the inconsistencies in the literature, the limited number of studies concerning text reading fluency, and the theoretical reasons to expect a role for morphological awareness in word- and text-reading fluency (Shechter et al., 2018), these relationships were examined in this study. In particular, the contribution of morphological awareness to later word- and text-reading fluency were tested, after variance accounted for by initial word reading fluency, gains in such, phonological awareness, and rapid naming were taken into account.

Listening comprehension and reading fluency

Linguistic comprehension, or understanding spoken sentences and discourse, is a major component of reading comprehension (Hoover and Gough, 1990). Research examining whether comprehension of spoken language also contributes to reading fluency is quite limited. Kim (2015) found that Korean listening comprehension was not uniquely associated with concurrent text reading fluency when the sample was younger (mean age was 5 yrs., 2 mos). One year later, however, listening comprehension did predict concurrent text reading fluency beyond word reading fluency. In a longitudinal study with young English readers, first-grade students’ fall listening comprehension predicted spring text reading fluency beyond fall word reading fluency; however, second-grade listening comprehension was not uniquely associated with text reading fluency one year later (Kim et al., 2021). This finding suggests that this relationship may be developmentally limited; that is, listening comprehension may facilitate text reading fluency only for young children whose single word reading is still relatively slow or inefficient. On the other hand, theories that propose automatic activation among semantically related words during reading or propose a top-down influence reflecting linguistic comprehension would lead us to expect an ongoing role for listening comprehension in text reading fluency (e.g., Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001; Jenkins et al., 2003; Hudson et al., 2009). This is consistent with the findings that first through fourth grade students’ listening comprehension contributed to variance in concurrent English text reading fluency beyond single word reading fluency (Kim and Wagner, 2015). Furthermore, bivariate correlations were small to moderate for listening comprehension and later word- and text reading fluency, although unique longitudinal associations were not examined. Further research concerning associations of listening comprehension with later fluency is needed.

The present study

The present study contributes to understanding aspects of fluency development in English reading by addressing three primary questions: (1) Do gains in word reading fluency over 6 months of second and third grade account for variance in word- and text-reading fluency one year later, after controlling for initial word reading fluency, phonological awareness, and rapid naming (as well as the two language skills)? It was hypothesized that gains in word reading fluency over this period would influence final outcomes, even beyond this stringent set of controls. (2) Do each of initial morphological awareness and listening comprehension account for unique variance in word- and text-reading fluency outcomes, over and above the control variables in this study? It was hypothesized that morphological awareness would account for variance in both fluency outcomes. Consistent with theoretical models (Kim, 2015), it was predicted that the effects of listening comprehension would be specific to text reading fluency. (3) Do each of the two oral language skills predict unique variance in final outcomes in text reading fluency beyond variance accounted for by final outcomes in word reading fluency? This question allows an examination of the effects of each oral language skill on text reading fluency that is not accounted for by an association with final outcomes in word reading fluency. It was predicted that listening comprehension would have a unique association with text reading fluency, but it is not clear if this would be the case for morphological awareness.

Methods

Participants

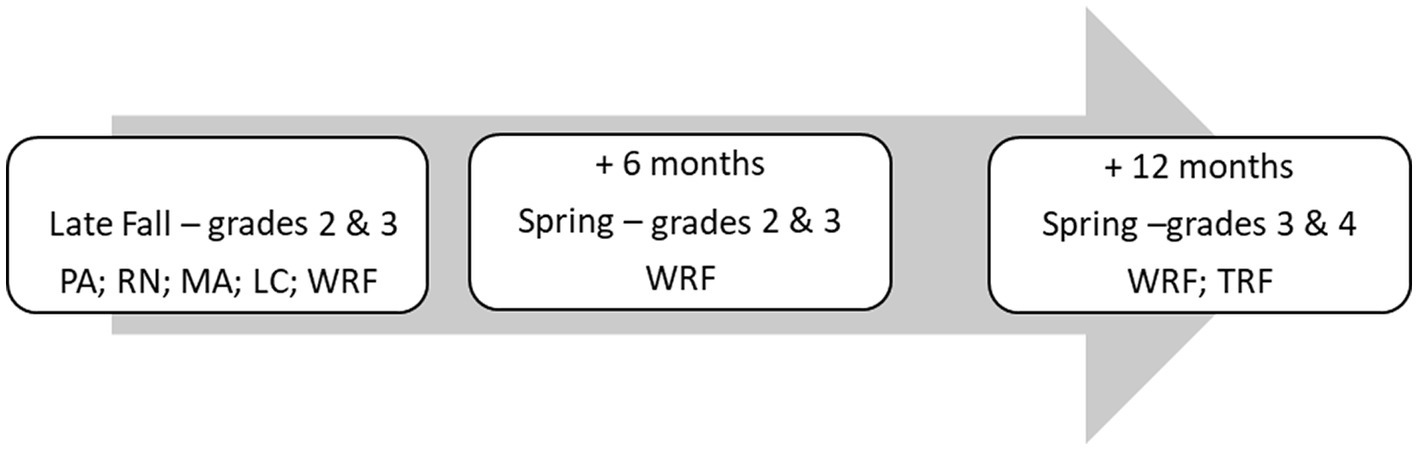

Second and third grade students were recruited as part of a longitudinal study on oral language and reading in English. Eighty-three students completed a battery that included word- and text- reading fluency measures. Initial testing occurred when the students were in late fall of their second or third grade year (Initial time; Late fall-Year 1). After roughly six months, students again completed the word reading fluency measure (Spring-Year 1). Final fluency outcomes were measured roughly 18 months after study inception (Final time; Spring-Year 2; Figure 1 shows the time line for measure administration).

Figure 1. Time line for administering measures across the 18 months of this study. PA, phonological awareness; RN, rapid naming; MA, morphological awareness; LC, listening comprehension; WRF, word reading fluency; TRF, text reading fluency.

Thirty-nine of these participants were in second grade at the beginning of the study (mean age 7;6 years; range 6;11–8;8; 20 females) and 44 in third grade at study onset (mean age of 8;4 years; range 7;10–8;10; 18 females). All but four students spoke English as their first language; these four students started to learn English as an additional language between 2 to 4 years of age and were included in all analyses.

The children were recruited from six public schools in suburban neighborhoods in an Eastern Canadian province. The neighborhoods were made-up largely of working- and middle-class families (district provided data showed the means of families served by the schools in the study did not differ from the district more generally concerning the prevalence of families with post-secondary education or categorized as falling within a low-income bracket; Ms = 49% and 7% for the district, respectively). The province and school district follow a balanced literacy curriculum (Nova Scotia, 2019).

Procedure

The study received ethical clearance from Mount Saint Vincent University’s Research Ethics Board. All participants were included whose parents or legal guardians signed consent forms. The young participants gave assent to participate at the beginning of each session. All students were tested individually in quiet rooms within their schools.

Instruments

All standardizes measures were administered following directions in each test manual.

Reliability coefficients reported for all standardized measures were above 0.80. The morphological awareness measure was an experimental measure, and is described below.

Phonological awareness: initial testing time

The Elision subtest of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing - II (Wagner et al., 2013) required children to repeat a spoken word omitting the indicated sound(s) (e.g., “Say dog, now say it again without the /g/”).

Rapid automatized naming: initial testing time

Naming speed was measured by the RAN Digit subtest of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing - II (Wagner et al., 2013). Children are asked to name the stimuli as accurately and quickly as possible across the rows on a page. The manual reports raw scores as a function of number of errors and the time taken.

Word reading fluency: all three testing times

The Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE-2; Torgesen et al., 2012) required children to read as many words, in list format, as they could in 45 s. The raw score is number of words read correctly.

Gains in word reading fluency. Gains in word reading fluency across the 6 months of Year 1 were calculated by subtracting Time 1 raw scores on this subtest from T2 raw scores. Thus, these scores are the number of additional words each child read in 45 s at Time 2 than at Time 1.

Text reading fluency: final testing time

The Oral Reading Fluency subtest of the Woodcock Reading Mastery Tests - 3rd Edition (Woodcock, 2011) required children to read a series of short passages aloud. Their fluency score is based on the number of errors and the time taken for each passage.

Listening comprehension: initial testing time

Listening comprehension was measured with the Understanding Spoken Paragraphs subtest of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals - 5th edition (CELF–5; Wiig et al., 2013). The examiner read aloud a series of paragraphs, and asked the student open ended questions after each paragraph.

Morphological awareness: initial testing time

A two-part, inflectional morphology task was used. The first twelve items required each child to provide the correct morphological form of a word that completed a spoken sentence. These items were from the Word Structure subtest of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Functioning–5 (Wiig et al., 2013). Five additional items required each child to correct mistakes in spoken sentences. All correct sentences required a manipulation of morphemes to correct the subject-verb agreement errors (e.g., The cats plays and Todd sleep; correct The cat plays and Todd sleeps or The cats play and Todd sleeps). These items stressed the meta-linguistic component of morphological awareness. Tasks with inflectional morphology were used to further tap into meta-cognitive awareness, as children this age have largely mastered implicit inflectional morphology (Robertson and Deacon, 2019). The Cronbach’s alpha for this experimental task was 0.70.

Results

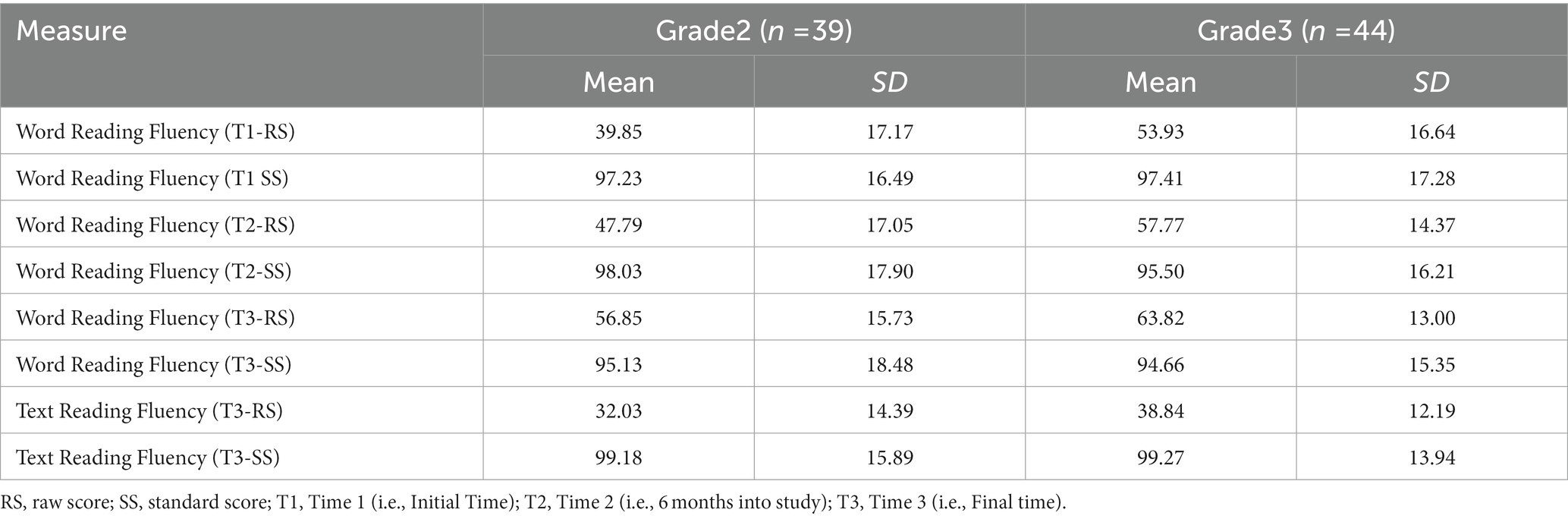

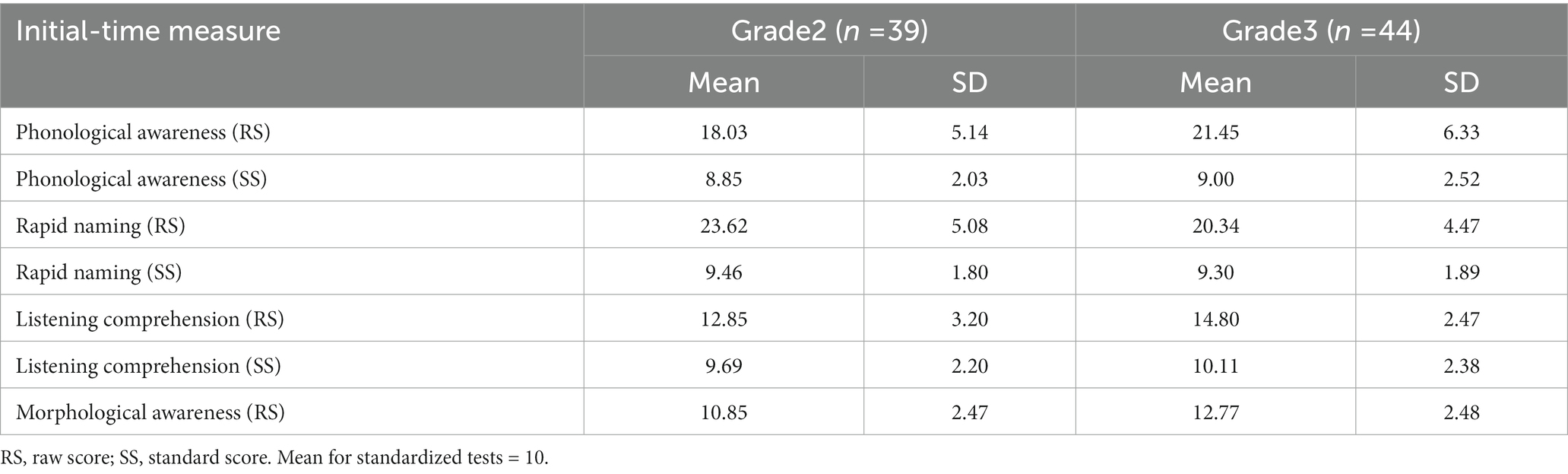

All variables in the study were normally distributed and there were no multivariate outliers (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013). Raw scores are used in all analyses. Only one data point was missing, and this participant’s data was not included in all analyses that included morphological awareness. Descriptive statistics are shown in Tables 1, 2 for all measures in this study. As can be seen from these Tables, the sample’s standardized mean scores fell within the average range for all reading fluency measures and the additional reading-related skills, and the standard deviations appear similar to those on the standardized measures.

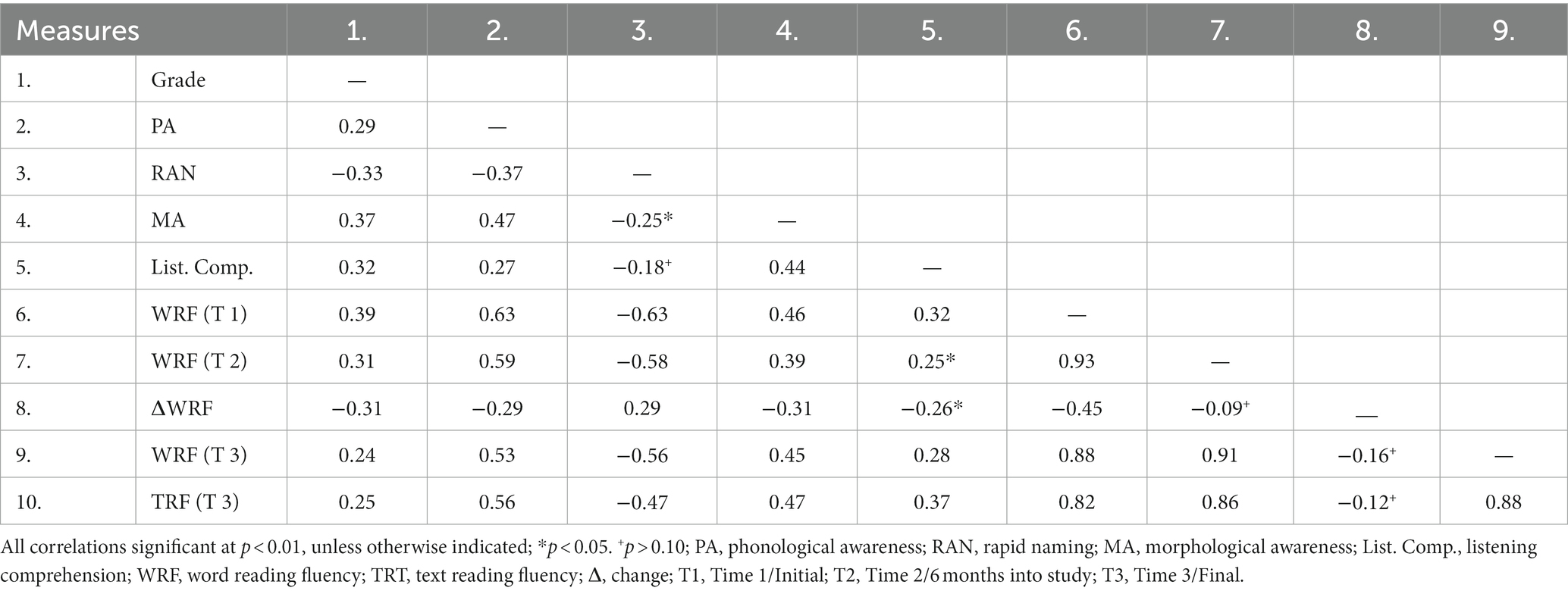

Bivariate correlations are shown in Table 3. Each of phonological awareness, rapid naming, morphological awareness, and listening comprehension are correlated with each measure of word- and text-reading fluency. The word reading fluency gain scores (based on the first six months of the study) are negatively correlated with initial word reading fluency. This indicates that those who had lower word reading fluency in the fall, made greater gains in this skill over the following 6 months. This is similar to previous findings for text reading fluency; students with lower fluency in the fall of grade 1 had greater growth across that academic year (Petscher and Kim, 2011).

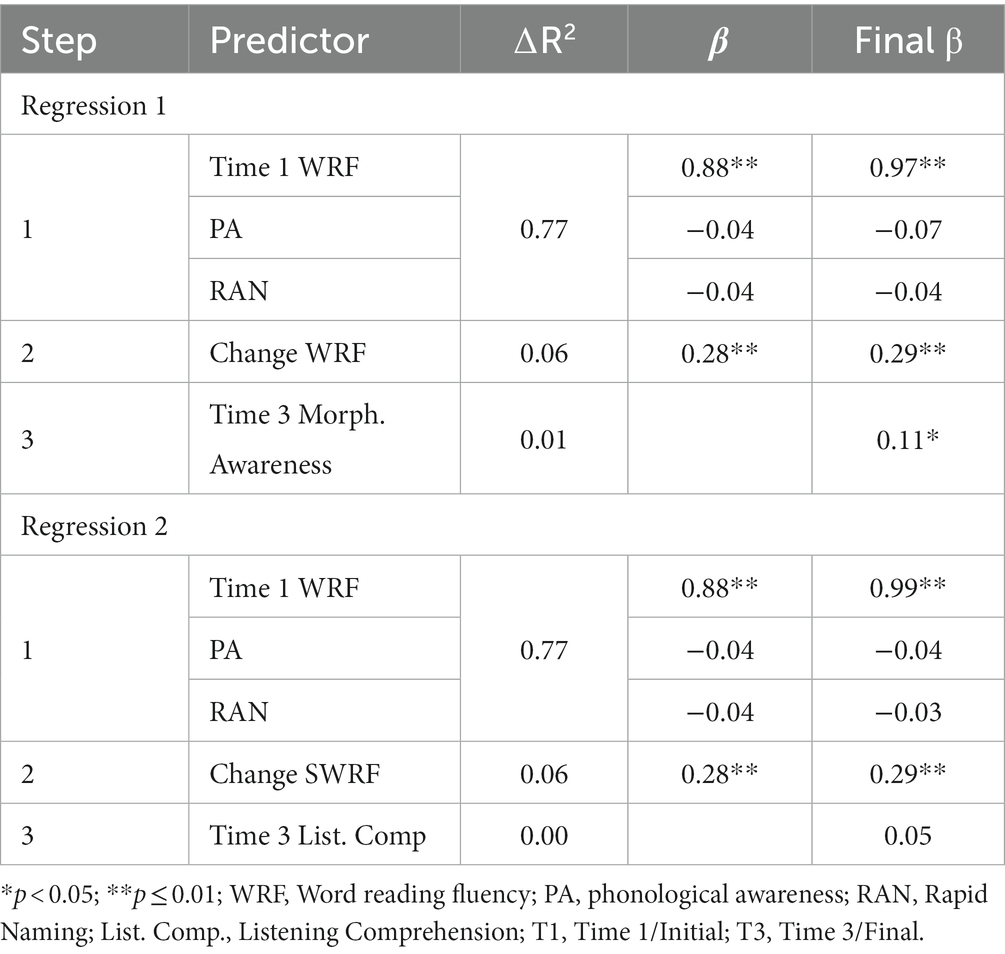

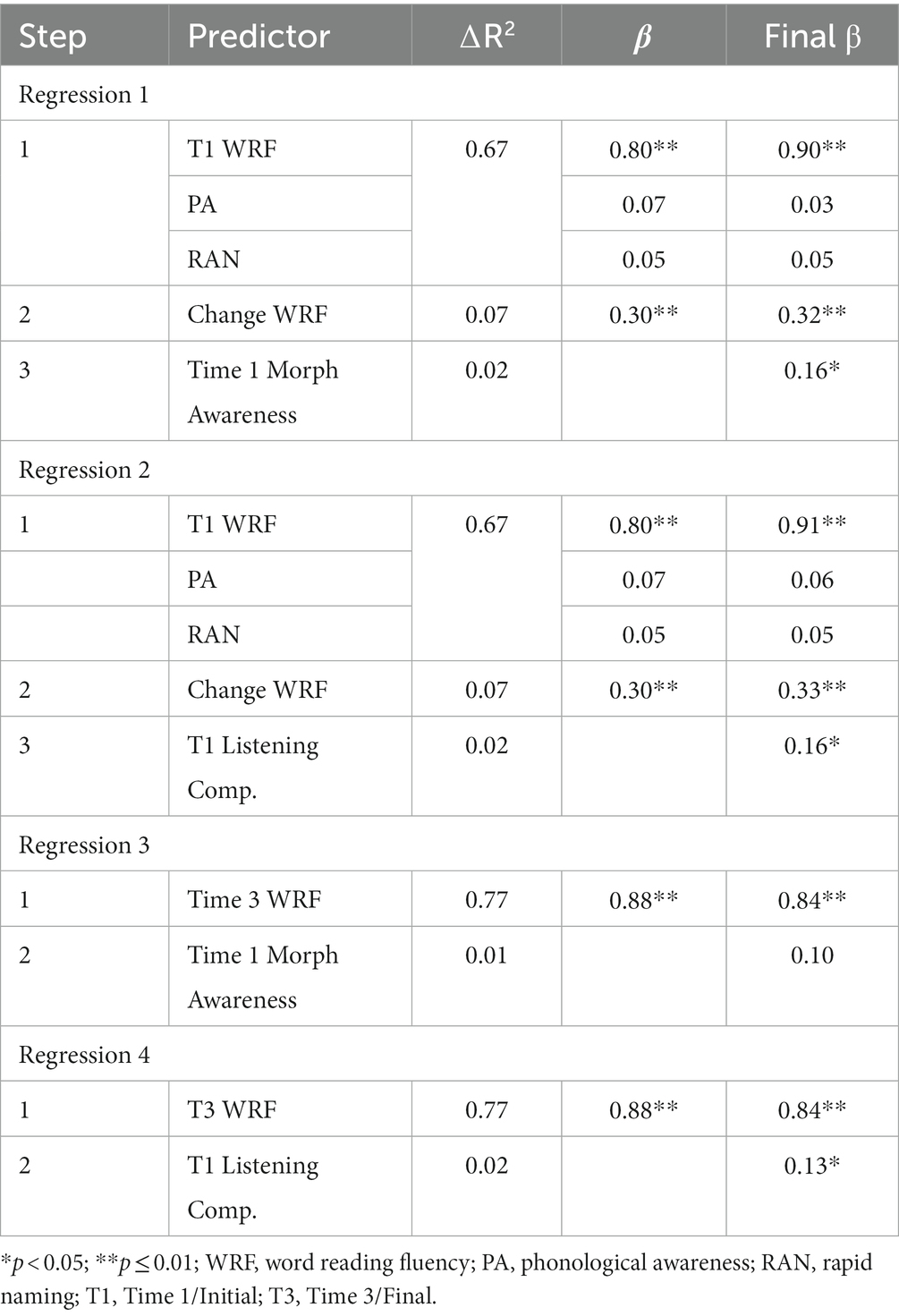

A series of hierarchical regressions were used to answer the first two research questions. First, to test whether gains in word reading fluency and initial morphological awareness predicted unique variance in final word reading fluency, a hierarchical regression was conducted with initial word reading fluency, phonological awareness and rapid naming entered in Step 1 (Table 4, Regression 1). This step accounted for 77% of the total variance, with initial word- reading fluency as the only significant predictor. Gains in word reading fluency accounted for an additional 6% of the variance as Step 2. Finally, morphological awareness predicted an additional, small but significant 1% of the variance in final word reading fluency.

The same hierarchical regression was conducted but with listening comprehension entered in Step 3 (Table 4, Regression 2). Listening comprehension was not a significant predictor of unique variance in final word reading fluency.

Similar analyses were used to examine whether morphological awareness, listening comprehension, and gains in word reading fluency predicted unique variance in final text- reading fluency. In the first regression, Step 1 accounted for 67% of the variance, with initial word reading fluency as the only significant predictor (Table 5, Regression 1). In Step 2, gains in word reading fluency accounted for an additional 7% of the total variance. In Step 3, morphological awareness predicted an additional 2% of the variance in text reading fluency. In the next hierarchical regression, listening comprehension comprised Step 3, predicting an additional 2% of the variance in final text reading fluency (Table 5, Regression 2).

The final regressions examined whether each of the two oral language skills would remain significant predictors of final text reading fluency, after accounting for final word reading fluency. First, final word reading fluency accounted for 77% of the total variance in text- reading fluency. When entered as Step 2, morphological awareness did not predict additional variance in text reading fluency (Table 5, Regression 3). In contrast, when entered as Step 2, listening comprehension accounted for an additional 2% of the variance in text reading fluency (Table 5, Regression 4).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine unique contributions of English-speaking second and third grade students’ initial morphological awareness and listening comprehension, as well as early gains in word reading fluency, to outcomes in word- and text-reading fluency. The sample of students in this study showed distributions on word- and text-reading fluency measures that appeared similar to the normative, standardization samples (see Table 1). The study controlled for initial word reading fluency, phonological awareness, and rapid naming. Findings highlight the importance of continuing gains in word reading fluency over 6 months of second and third grade to fluency outcomes near the end of their third and fourth grade year. Initial word reading fluency did, however, account for the bulk of the variance in later fluency outcomes. Students’ initial morphological awareness also predicted outcomes in both word- and text-reading fluency 18 months later; however, the unique contribution of morphological to text reading fluency was accounted for by its association with final word reading fluency. On the other hand, there was a consistent unique effect of listening comprehension on text reading fluency. Each finding in this study is discussed in turn.

The contributions of earlier gains in word reading fluency to fluency outcomes

The findings in this study, coupled with previous research, help to delineate the developmental time course of individual differences in English word reading fluency. For students with reading impairments beyond first grade, it has proven difficult to move the needle on standardized measures of reading fluency, while effective interventions prior to the end of first grade tend to normalize fluency outcomes (Torgesen et al., 2001). These findings suggest that trajectories for English reading-fluency development may be solidified quite early in this process of learning to read. The current study lends support to the notion that fluency skills are determined quite early in the reading process. By the late fall of second and third grade, word reading fluency accounted for the bulk of the variance in word- and text-reading fluency outcomes 18 months later (77 and 68%, respectively). At the same time, additional, relatively sizable variance in both fluency outcomes were accounted for by gains in word reading fluency over six months of second and third grade (6–7%). Importantly, students who started off lower in word reading fluency made greater gains on this skill than those who were higher at study onset (similar to past findings for text reading fluency; Kim et al., 2010). This means that relative standing in word reading fluency remains at least somewhat malleable across the second and third grade years.

Neither phonological awareness nor rapid naming predicted unique variance in word- or text-reading fluency outcomes for this relatively opaque orthography. Conceivably, there may be a direct role for these skills on word reading fluency in participants younger than those in the current study; but, the roles of these two skills may be developmentally limited in English reading. Findings do not support the notion that phonemic awareness proficiency for more advanced phonological awareness tasks such as manipulation and deletion (the later measured in the current study), has a unique role or is critical to ongoing growth in fluency across these elementary grades (Kilpatrick, 2020). The related recommendation for a prolonged focus on oral-only phonemic awareness instruction in order to set a solid trajectory for fluency (Heggerty, 2003; Kilpatrick, 2015) conflicts with recommendations from the National Reading Panel (2000) (see Brady, 2020, for updated review and discussion) and are not suggested by the correlational findings in this study. Rather, the current study suggests a more direct focus on increasing efficiency of word reading skills in second and third grade may increase later reading fluency outcomes. This may not have been a target of instruction within the context of the balanced literacy curriculum for students in the current study; that is, balanced literacy tends not to place a significant focus on instruction for efficient, context-free recognition of words (Spear-Swerling, 2019).

The contribution of morphological awareness to word- and text-reading fluency

Multicomponent models of reading comprehension have outlined direct roles for foundational oral language knowledge on comprehension processes (e.g., Stafura and Perfetti, 2017). Models of reading fluency have also proposed a role for morphological knowledge directly to fluency (Hudson et al., 2009, 2012; Kim, 2015); fluency in turn, also contributes to reading comprehension (Kim et al., 2021). In this study, students’ morphological awareness at the beginning of second and third grade was a predictor of gains in word reading fluency 18 months later. This finding builds on some past research by controlling for phonological awareness, rapid naming, and the autoregressive variable. Theoretical accounts propose several mechanisms through which morphological knowledge may influence word reading fluency. In Ehri’s Phase Theory, efficient word reading comes to rely on increasingly larger chunks of internalized orthographic patterns, including morphemes (Ehri, 2005). This association seems congruent with Hudson et al.’s (2009) model, which proposes this higher-level orthographic knowledge as one influence on reading fluency (see also, Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001). Levesque et al. (2021) propose an additional mechanism; children actively use their knowledge of morphemes to analyze and decode words. In turn, morphemes as meaningful units may trigger “top-down semantic activation enabling faster and more accurate word reading” (Levesque et al., 2021, p. 14). In support, Nunes et al. (2012) found that the degree to which children used morphological units in decoding and spelling predicted later outcomes in both word- and text-reading fluency. Morphological awareness thus appears to play a role in developing word reading fluency, and this may become more critical with the increase of morphologically complex words in texts with rising grades.

Morphological awareness was also found to predict unique variance in later text reading fluency, beyond initial status and early gains in word reading fluency, phonological awareness and rapid naming. This adds to a relatively small body of research examining this association from a longitudinal perspective. At first glance, it appears that morphological awareness, perhaps as one component of the top-down linguistic processes, facilitates text reading fluency. However, after controlling for final outcomes in word reading fluency, morphological awareness no longer predicted unique variance in text reading fluency. Kirby et al. (2012) found a unique contribution from grade 2 morphological awareness to grade 3 text reading fluency; however, initial or final status in word reading fluency were not included in their model. Kim (2015) found that morphological awareness did not predict later Korean reading fluency when word reading fluency was in the model, albeit Korean is a more transparent orthography. Although the current findings suggest that the association between morphological awareness and text reading fluency are fully accounted for by its influence on gains in word reading fluency – this in no way diminishes its importance to text reading fluency, given the magnitude of the association between final outcomes in word- and text-reading fluency (r = 0.88). The unique role found in this study for morphological awareness on word reading fluency appears consistent with this aspect of the Morphological Pathway’s model (Levesque et al., 2021).

The contributions of listening comprehension to word- and text-reading fluency

Understanding oral language is an important component of reading comprehension (Hoover and Gough, 1990). This study contributes to the limited body of research on a potential role for listening comprehension in children’s fluency development. Children’s listening comprehension predicted unique variance in later text reading fluency, but not word reading fluency, beyond that accounted for by measures of earlier word reading fluency, phonological awareness, and rapid naming. Furthermore, this unique contribution remained significant when final outcomes in word reading fluency were entered into the equation. Previous research addressing this relationship has been somewhat sparse, but the findings from this study are consistent with multi-component models of fluency development (e.g., Hudson et al., 2009, 2012). For one such model, it is proposed that elements associated with reading (and listening) comprehension (e.g., knowledge, vocabulary, passage- and social-context) have a top-down influence on text reading fluency (Hudson et al., 2009). Their model does not incorporate direct or indirect effects of these comprehension processes on word reading fluency, consistent with the specific association found in the current study. Meaning making processes involved in oral language comprehension thus appear to facilitate text reading fluency, even over these extended years of elementary school. While the Simple View of Reading proposes a role for linguistic comprehension to reading comprehension (Hoover and Gough, 1990), the current findings are consistent with somewhat more complex models which support its role in text reading fluency (Kim, 2015). That is, listening comprehension may directly influence comprehension as a facet of semantic linguistic processes (Stafura and Perfetti, 2017), and may have an indirect effect on comprehension through its potential contribution to reading fluency. This proposal is also consistent with Kim and Wagner’s (2015) findings that the relationship from listening comprehension to reading comprehension in English, was partially mediated by text reading fluency for second through fourth grade students.

Limitations

The current study adds to the growing research examining the time course of fluency development and the role of two dimensions of oral language. This study has limitations which must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the measure of morphological awareness included inflectional but not derivational morphology. This was judged appropriate as inflectional knowledge is more stable for the developmental period examined, and thus individual differences may more heavily tap meta-linguistic knowledge (see also Robertson and Deacon, 2019). However, derivational knowledge has been measured in this age range and further research is needed to test the generalizability of the current finings for this additional aspect of morphology. Second, the current study defined text reading fluency in terms of accuracy and speed (see also Kim, 2015; Kim et al., 2021). Other researchers include prosody or expression as a component of text reading fluency. The unique contributions of oral language measures may vary depending on how text reading fluency is operationalized. The current study lends support for a unique contribution of listening comprehension to text reading fluency, and this association might be expected to be stronger when prosodic elements are included in oral reading fluency measures. Third, the sample size was relatively small and thus somewhat limited the data analytic approach. Finally, the study was conducted within the context of a balanced literacy instructional approach (for discussion, see Spear-Swerling, 2019). Future research is needed to test the proposed direct and indirect contributions of these oral language skills to reading fluency outcomes and to test the generalizability to instructional contexts that may include more direct focus on word reading accuracy and efficiency.

Conclusion

Longitudinal research findings on the associations examined in this study have been inconsistent or sparse. The current findings contribute to a better understanding of the developmental time course of fluency skills in these early elementary years and of the contributions of oral language skills to reading fluency. Individual differences in word reading fluency appear quite stable from early in second and third grade. This has implications for thinking about early word reading instruction; approaches that focus on both accuracy and efficiency for components of word reading instruction from the earliest grades may be critical (Lane and Contessa, 2022). At the same time, the significant gains across six months of second and third grade influenced fluency outcomes near the end of the students’ third- and fourth-grade years, and gains were largest for those with lower initial scores. Continued targeted instruction in word reading fluency across this period may help change trajectories for those off to a slower start. Findings also suggested that phonological awareness and rapid naming may have a developmentally limited role to play in reading fluency and the findings do not support an ongoing focus across these grades on oral-only phonemic awareness instruction. Finally, consistent with Kim’s (2015) proposal, findings supported specificity in the unique associations of reading-related oral language skills with fluency. Morphological awareness appears to contribute primarily to gains in word reading fluency, consistent with mechanisms outlined in some models (Levesque et al., 2021). In turn, word reading fluency is the major determinant of text reading fluency. Conversely, listening comprehension was uniquely associated to outcomes in text reading fluency, supporting a potential role for top-down linguistic processes in text reading fluency (Hudson et al., 2009, 2012).

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the consent forms signed for this study preclude making the data for this manuscript openly available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to JM: SmFtaWUuTWV0c2FsYUBtc3Z1LmNh.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University Research Ethics Board, Mount Saint Vincent University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by an Inter-University Research Network Grant from the Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and by funding from the Gail and Stephen Jarislowsky Research Chair in Learning Disabilities Endowment at Mount Saint Vincent University.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank participating students, their teachers and principals, as well as university researchers and the team who worked with the students, for their contributions to this research.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Apel, K., Diehm, E., and Apel, L. (2013). Using multiple measures of morphological awareness to assess its relation to reading. Top. Lang. Disord. 33, 42–56. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0b013e318280f57b

Brady, S. (2020). A 2020 perspective on research findings on alphabetics (phoneme awareness and phonics): Implications for instruction (expanded version). Read. League J. 1, 20–28.

Carlisle, J. F. (2000). Awareness of the structure and meaning of morphologically complex words: Impact on reading. Reading and Writing 12, 169–190. doi: 10.1023/A:1008131926604

Deacon, S. H., and Kieffer, M. (2018). Understanding how syntactic awareness contributes to reading comprehension: Evidence from mediation and longitudinal models. J. Educ. Psychol. 110, 72–86. doi: 10.1037/edu0000198

Desrochers, A., Manolitsis, G., Gaudreau, P., and Georgiou, G. (2018). Early contribution of morphological awareness to literacy skills across languages varying in orthographic consistency. Read. Writ. 31, 1695–1719. doi: 10.1007/s11145-017-9772-y

Diamanti, V., Mouzaki, A., Ralli, A., Antoniou, F., Papaioannou, S., and Protopapas, A. (2017). Preschool phonological and morphological awareness as longitudinal predictors of early reading and spelling development in Greek. Front. Psychol. 8, 20–39. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02039

Ehri, L. C. (1998). “Grapheme-phoneme knowledge is essential for learning to read words in English” in Word recognition in beginning literacy. eds. J. L. Metsala and L. C. Ehri (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 3–40.

Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Sci. Stud. Read. 9, 167–188. doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

Ehri, L. C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Sci. Stud. Read. 18, 5–21. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Georgiou, G. K., Parrila, R., and Papadopoulos, T. C. (2008). Predictors of word decoding and reading fluency across languages varying in orthographic consistency. J. Educ. Psychol. 100:566. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.3.566

Giazitzidou, S., Mouzaki, A., and Padeliadu, S. (2023). Pathways from morphological awareness to reading fluency: the mediating role of phonological awareness and vocabulary. Read. Writ., 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11145-023-10426-2

Giazitzidou, S., and Padeliadu, S. (2022). Contribution of morphological awareness to reading fluency of children with and without dyslexia: evidence from a transparent orthography. Ann. Dyslexia 72, 509–531. doi: 10.1007/s11881-022-00267-z

Hasbrouck, J., and Tindal, G. (2017). An update to compiled ORF norms (No. 1702). Technical report. Available at: https://intensiveintervention.org/sites/default/files/TechRpt_1702ORFNorms%20FINAL.pdf (Accessed March 26, 2023).

Heggerty, M. (2003). Phonemic awareness: The skills that they need to help them succeed! Oak Park, IL: Literacy Resources Inc.

Hoover, W. A., and Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Read. Writ. 2, 127–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00401799

Hudson, R. F., Pullen, P. C., Lane, H. B., and Torgesen, J. K. (2009). The complex nature of reading fluency: A multidimensional view. Read. Writ. Quar. Overc. Learn. Difficult. 25, 4–32. doi: 10.1080/10573560802491208

Hudson, R. F., Torgesen, J. K., Lane, H. B., and Turner, S. J. (2012). Relations among reading skills and sub-skills and text-level reading proficiency in developing readers. Read. Writ. Interdiscip. J. 25, 483–507. doi: 10.1007/s11145-010-9283-6

Jenkins, J. R., Fuchs, L. S., Van Den Broek, P., Espin, C., and Deno, S. L. (2003). Sources of individual differences in reading comprehension and reading fluency. J. Educ. Psychol. 95, 719–729. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.719

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: a longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 80, 437–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.80.4.437

Kilpatrick, D. A. (2015). Essentials of assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kilpatrick, D. A. (2020). How the phonology of speech is foundational for instant word recognition. Persp. Lang. Liter. 46, 11–15.

Kim, Y. S. G. (2015). Developmental, component-based model of reading fluency: An investigation of predictors of word-reading fluency, text-reading fluency, and reading comprehension. Read. Res. Q. 50, 459–481. doi: 10.1002/rrq.107

Kim, Y. S. G., Petscher, Y., Schatschneider, C., and Foorman, B. (2010). Does growth rate in oral reading fluency matter in predicting reading comprehension achievement? J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 652–667. doi: 10.1037/a0019643

Kim, Y. S. G., Quinn, J. M., and Petscher, Y. (2021). What is text reading fluency and is it a predictor or an outcome of reading comprehension? A longitudinal investigation. Dev. Psychol. 57, 718–732. doi: 10.1037/dev0001167

Kim, Y. S. G., and Wagner, R. K. (2015). Text (oral) reading fluency as a construct in reading development: An investigation of its mediating role for children from grades 1 to 4. Sci. Stud. Read. 19, 224–242. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2015.1007375

Kirby, R. J., and Bowers, P. N. (2017). “Morphological instruction and literacy: binding phonological, orthographic, and semantic features of words” in Theories of reading development. eds. K. Cain, D. L. Compton, and R. K. Parrila (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 437–461.

Kirby, J. R., Deacon, S. H., Bowers, P. N., Izenberg, L., Wade-Woolley, L., and Parrila, R. (2012). Children’s morphological awareness and reading ability. Read. Writ. 25, 389–410. doi: 10.1007/s11145-010-9276-5

Klauda, S. L., and Guthrie, J. T. (2008). Relationships of three components of reading fluency to reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 100, 310–321. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.310

LaBerge, D., and Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cogn. Psychol. 6, 293–323. doi: 10.1016/00100285(74)90015-2

Landerl, K., Freudenthaler, H. H., Heene, M., De Jong, P. F., Desrochers, A., Manolitsis, G., et al. (2019). Phonological awareness and rapid automatized naming as longitudinal predictors of reading in five alphabetic orthographies with varying degrees of consistency. Sci. Stud. Read. 23, 220–234. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2018.1510936

Lane, H., and Contessa, V. (2022). UFLI foundations: an explicit and systematic phonics program. Sun Prairie, WI: Ventris Learning.

Lee, J. W., Wolters, A., and Grace Kim, Y. S. (2022). The Relations of Morphological Awareness with Language and Literacy Skills Vary Depending on Orthographic Depth and Nature of Morphological Awareness. Rev. Educ. Res., 1–31. doi: 10.3102/00346543221123816

Levesque, K. C., Breadmore, H. L., and Deacon, S. H. (2021). How morphology impacts reading and spelling: Advancing the role of morphology in models of literacy development. J. Res. Read. 44, 10–26. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.12313

Manolitsis, G., Georgiou, G. K., Inoue, T., and Parrila, R. (2019). Are morphological awareness and literacy skills reciprocally related? Evidence from a cross-linguistic study. J. Educ. Psychol. 111, 1362–1381. doi: 10.1037/edu0000354

Manolitsis, G., Grigorakis, I., and Georgiou, G. K. (2017). The longitudinal contribution of early morphological awareness skills to reading fluency and comprehension in Greek. Front. Psychol. 8, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01793

McBride-Chang, C., Cho, J. R., Liu, H., Wagner, R. K., Shu, H., Zhou, A., et al. (2005). Changing models across cultures: Associations of phonological awareness andmorphological structure awareness with vocabulary and word recognition in second graders from Beijing, Hong Kong, Korea, and the United States. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 92, 140–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2005.03.009

Metsala, J. L., and David, M. D. (2017). The effects of age and sublexical automaticity on reading outcomes for students with reading disabilities. J. Res. Read. 40, S209–S227. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.12097

Metsala, J. L., and David, M. D. (2022). Improving English reading fluency and comprehension for children with reading fluency disabilities. Dyslexia 28, 79–96. doi: 10.1002/dys.1695

Metsala, J. L., Sparks, E., David, M., Conrad, N., and Deacon, S. H. (2021). What is the best way to characterise the contributions of oral language to reading comprehension: listening comprehension or individual oral language skills? J. Res. Read. 44, 675–694. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.12362

National Reading Panel (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Norton, E. S., and Wolf, M. (2012). Rapid automatized naming (RAN) and reading fluency: Implications for understanding and treatment of reading disabilities. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 427–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych120710-100431

Nova Scotia (2019). English Language Arts P-6: At a Glance. Available at: English Language Arts P-6 at a glance (2019).pdf (novascotia.ca)

Nunes, T., Bryant, P., and Barros, R. (2012). The development of word recognition and its significance for comprehension and fluency. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 959–973. doi: 10.1037/a00

Papadopoulos, T. C., Spanoudis, G. C., and Georgiou, G. K. (2016). How is RAN related to reading fluency? A comprehensive examination of the prominent theoretical accounts. Front. Psychol. 7:1217. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01217

Perfetti, C. A. (1988). “Verbal efficiency in reading ability” in Reading research: advances in theory and practice. eds. M. Daneman, G. E. Mackinnon, and G. T. Waller, vol. 6 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 109–143.

Perfetti, C. A. (2007). Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension. Sci. Stud. Read. 11, 357–383. doi: 10.1080/10888430701530730

Perfetti, C., and Stafura, J. (2014). Word knowledge in a theory of reading comprehension. Sci. Stud. Read. 18, 22–37. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2013.827687

Petscher, Y., and Kim, Y. S. (2011). The utility and accuracy of oral reading fluency score types in predicting reading comprehension. J. Sch. Psychol. 49, 107–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.09.004

Robertson, E. K., and Deacon, S. H. (2019). Morphological awareness and word-level reading in early and middle elementary school years. Appl. Psycholinguist. 40, 1051–1071. doi: 10.1017/S0142716419000134

Seidenberg, M. S., and McClelland, J. L. (1989). A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychol. Rev. 96, 523–568. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.523

Share, D. L. (2008). “Orthographic learning, phonological recoding, and self-teaching” in Advances in child development and behavior. ed. R. V. Kail, vol. 36 (Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press), 31–82.

Shechter, A., Lipka, O., and Katzir, T. (2018). Predictive models of word reading fluency in Hebrew. Front. Psychol. 9:1882. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01882

Spear-Swerling, L. (2019). Structured literacy and typical literacy practices: Understanding differences to create instructional opportunities. Teach. Except. Child. 51, 201–211. doi: 10.1177/0040059917750

Stafura, J. Z., and Perfetti, C. A. (2017). “Integrating word processing with text comprehension” in Theories of reading development. eds. K. Cain, R. K. Parrila, and D. L. Compton (John Benjamins), 9–31.

Stanovich, K. E. (2000). Progress in understanding reading: Scientific foundations and new frontiers. New York: Guilford Press.

Torgesen, J. K., and Hudson, R. (2006). “Reading fluency: Critical issues for struggling readers” in Reading fluency: The forgotten dimension of reading success. eds. S. J. Samuels and A. Farstrup (Newark: International Reading Association), 130–158.

Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C. A., and Alexander, A. (2001). “Principles of fluency instruction in reading: Relationships with established empirical outcomes” in Dyslexia, fluency, and the brain. ed. M. Wolf (London: York Press), 333–356.

Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., and Rashotte, C. A. (2012). Test of word reading efficiency (TOWRE-2). 2nd Edn. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C. A., and Pearson, N. A. (2013). Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP-2) 2nd Edn. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Wiig, E. H., Semel, E., and Secord, W. A. (2013). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF-5) 5th Edn. London: NCS Pearson.

Wolf, M., and Bowers, P. G. (1999). The double-deficit hypothesis for the developmental dyslexias. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 415–438. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.415

Wolf, M., and Katzir-Cohen, T. (2001). Reading fluency and its intervention. Sci. Stud. Read. 5, 211–239. doi: 10.1207/S1532799XSSR0503_2

Keywords: reading development, reading fluency, morphological awareness, listening comprehension, longitudinal research

Citation: Metsala JL (2023) Longitudinal contributions of morphological awareness, listening comprehension, and gains in word reading fluency to later word- and text-reading fluency. Front. Educ. 8:1194879. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1194879

Edited by:

Pedro García Guirao, WSB Universities, PolandReviewed by:

Giulia Vettori, University of Florence, ItalyEster Trigo-Ibáñez, Universidad de Cádiz, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Metsala. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jamie L. Metsala, SmFtaWUuTWV0c2FsYUBtc3Z1LmNh

Jamie L. Metsala

Jamie L. Metsala