- Department of Education, Languages, Interculture, Literatures and Psychology, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

This study investigates the emergence of sound-sign correspondence in Italian-speaking 5-year-old pre-schoolers. There are few experimental studies on the precursors of reading and writing skills and those existing mainly focus on letter knowledge or logographic processing of words in pre-schoolers. This paper evaluates and compares 5-year-old children’s use of the logographic processing or the use of sound-sign processing to decode target words in original and modified versions. Furthermore, we verify whether pre-schoolers’ type of reading words (logographic versus sound-sign processing) vary in accordance with children’s socio-cultural differences (i.e., type of school and socio-cultural information from parents). This study tested 94 children (M-age = 5 years and 8 months) at the end of the last year of preschool. Six stimulus logos were used to evaluate children’s ability to decode words and the type of decoding (logographic or sound-sign processing). The Chi-square results confirm that the achievement of the correspondence between sound-sign at the base of reading and writing has already started in preschool. Our findings shed light on a significant proportion of pre-schoolers who can already read words via sound-sign processing or show the emergence of notational awareness, while the others still rely on logographic processing. Moreover, the results show that pre-schoolers’ notational awareness is related to socio-cultural characteristics pertaining to schools and families. These findings suggest that 5 years is an important age for the disentanglement between logographic and sound-sign correspondence in pre-schoolers and provide useful implications for theory and practice.

1. Introduction

In studying the development of children’s learning to read and write, most of the developmental theories on literacy acquisition refer to the importance of the so-called emergent literacy period (Pinto et al., 2012, 2017; Bigozzi et al., 2016a,b) which significantly supports later formalised learning to read and write. The emergent literacy period is identified as a preschool phase during which children are exposed to different forms of written language although this is not explicitly taught to them. Frith’s (1986) hypothesis states that initially children have access to the meaning of a written word using its visual form, without any phonological mediation, in what is called the ‘logographic phase’. Thus, at the very beginning of their contact with written language, most children seem to be able to read a small number of words, those belonging to their everyday life context (Frith, 1986). Frith’s theorisation has produced a conspicuous number of research studies to clarify several issues, for example the effective utility of the logographic phase for literacy acquisition and the existence of a logographic phase in all children (Bastien-Toniazzo and Jullien, 2001), the existence of language-specific effects (Aro and Wimmer, 2003; Spencer and Hanley, 2004; Marinelli et al., 2015), also given the great heterogeneity among subjects of the same age (Rayner et al., 2012).

A further line of research points out pre-schoolers’ sensitivity to extra-linguistic environments as central factors in achieving the meaning of words (Mol and Bus, 2011). Other studies suggest that children store an overall shape in their memory (Seymour and Elder, 1986) or just certain letters (Ellis and Large, 1988; Kuhn et al., 2010) or even salient graphic features of the word’s shape, such as the presence of ascenders and descenders (Ehri, 2020), that are used a cue to recognise written words.

In addition to these different perspectives on pre-schoolers’ sensitivity to written language features, Harris and Coltheart (1986) theorised that even in the first phase of literacy acquisition, which the authors call the visual vocabulary phase and place it when a child is four years old, children are able to read a small number of words aloud using a direct procedure (Harris and Coltheart, 1986).

In particular, the authors focus their attention on a single case of a four-year-old girl, Alice, (in the midst of a visual vocabulary stage) who was able to read about 30 words, some of which she had been taught while others were learned spontaneously. To find out whether this reading ability was based on a direct procedure or on visual form recognition, one of the words the child could read was used. The word “Harrods” was presented to her in a written form different from what she was used to (word in capital letters without logos). Alice was able to correctly read the word presented in an unusual graphic form, showing that she was using a directed reading process. This procedure is not related to grapheme-phoneme correspondence: words are recognised as specific sequences of letters and not in their global form. The child was also subjected to a second experiment: Alice was presented with a list of words similar to a word she already knew, (also on the list), but modified in the initial or final part, and she was able to correctly identify the known word. Here again, Alice used all the letters in the sequence to read the word and distinguish it from the others presented in the list (Harris and Coltheart, 1986). We also find this in the study by Masonheimer et al. (1984) where children, despite the alphabetical features of words being altered, read the same words through a correspondence between visual aspects and pronunciation with which, on the basis of their prior experience, they usually associate them. However, they do not consider the changes made and thus commit errors in reading the words XEPSI and PEPSI. Even though the letter P is replaced with an X, the children pay attention to the graphic aspects and continue to associate them with the form corresponding to the word PEPSI with which they have always been used to associating it, regardless of what is actually represented. In this example, we can also detect the effect of the law of the “good gestalt”: when children are in the condition to read a new piece of writing, they are inclined to point to what is the ‘form’ and therefore the most common, most balanced, simplest word that corresponds to it on the basis of its graphical aspects, without thinking of the possible presence of variations that would make it less homogeneous (Kanizsa, 1983). Thus on the basis of its visual characteristics, it is more harmonious to read the word XEPSI as PEPSI rather than in the actual corresponding form.

On the other hand, a part of the studies showed that preschool children already possess knowledge of the nature and conceptual meaning of a writing system at an early stage of development: drawing, numeracy, and literacy are all key components of emergent understanding of symbolic systems (Whitehurst and Lonigan, 1998; Rohde, 2015). All of these aspects influence the formal learning of conventional literacy processes (Hand et al., 2022) and can, therefore, be considered strong predictors of them (Missall et al., 2007; Bigozzi et al., 2016b).

Children already at preschool age possess the ability to differentiate between different symbolic systems (e.g., letters from numbers) and to use different knowledge and attitudes specific to each domain (Yamagata, 2007). Studies have shown that possession of these early skills leads to improved reading achievement in elementary school (Bishop, 2003). All these symbolic systems, therefore, allow the expression of mental representations (drawing and writing leave visible marks, unlike speaking or reading) (Hall et al., 2015) but differ in some aspects. Drawing can be described as a process characterised by recurring graphic patterns and certain rules that must be followed (Nicholls and Kennedy, 1992). Writing, on the other hand, is characterised by greater restrictions, as the set of units represents a closed system in which nothing can be added without drastically changing the meaning (Zhang and Treiman, 2021).

Pre-schoolers’ sensitivity to the characteristics of signs and letters is well-documented in the literature (Neumann et al., 2012). Preschool children, in order to best develop conceptual knowledge of their writing system, reflect upon the different symbolic systems used to represent meanings (e.g., written language, numerical language, and drawing), make spontaneous attempts to represent words in print (Milburn et al., 2017; Ouellette and Sénéchal, 2017) and try to systematically match the sounds included in words with signs that are not necessarily conventional (which should be distinguished from the letters of the alphabet) (Treiman and Kessler, 2013; Puranik et al., 2014). In particular, pre-schoolers’ notational awareness is a key component of the Emergent Literacy Model by Pinto et al. (2009, 2018; Pinto and Incognito, 2022) for Italian children. Notational awareness indicates pre-schoolers’ ability to understand and operate the correspondence between sound-sign. Invented reading and invented spelling activities demonstrate the emergence and mastering of letter-speech sound integrations by young children before schooling This complex skill, typical of preschool children, integrates phonological awareness (Ouellette and Sénéchal, 2017; Albuquerque and Alves Martins, 2022) with grapho-motor skills (Mohamed and O’Brien, 2022) and visual attention (Valdois et al., 2019). For example, “invented spelling” a developmental stage in which children attempt to merge the phonological and orthographic features of a word through the use of “invented” signs, written productions that, while not yet letters, include some of the properties of the writing system (Albuquerque and Alves Martins, 2022). An analysis of the literature suggests that, at later developmental ages, reading fluency (Bigozzi et al., 2016b) and the presence of reading and spelling disorders (Bigozzi et al., 2016a) are significantly affected by children’s early notational awareness. Previous studies show that socio-cultural factors affect children’s literacy skills. The study by Incognito and Pinto (2021) demonstrates that growing up in a rich environment in terms of literacy materials and experiences contributes to pre-schoolers’ emergent literacy skills development. Further research evidence shows the influence of home literacy on other important skills, such as word recognition (Evans and Shaw, 2008) and that children whose parents have higher levels of education and occupation interact with more literacy resources and receive more informal literacy activities, such as shared reading (Wang and Liu, 2021).

1.1. Aims and hypothesis

The aim of this study was to investigate the emergence and development of sound-sign correspondence in pre-schoolers.

Specifically, the aims were the following:

1) To evaluate and compare 5-year-old children’s use of logographic processing or the use of sign-sound processing to decode target logo words and whether there are differences between words written in Italian (transparent orthography) and words written in English (opaque orthography);

2) To verify whether pre-schoolers’ type of reading words (logographic versus sign-sound processing) vary in accordance with children’s socio-cultural differences (i.e., type of school and socio-cultural information from parents).

Regarding the first aim, we expect that 5 years is an important age for the disentanglement between logographic and sound-sign correspondence in pre-schoolers. In 5-year-old children referable to the logographic period, we expect to observe the significant emergence of notational awareness in pre-schoolers when using the sound-sign processing in decoding logo words.

Regarding the second aim, we hypothesised that pre-schoolers’ performances vary in accordance with children’s socio-cultural differences, linked to the type of preschool and socio-cultural information from parents.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

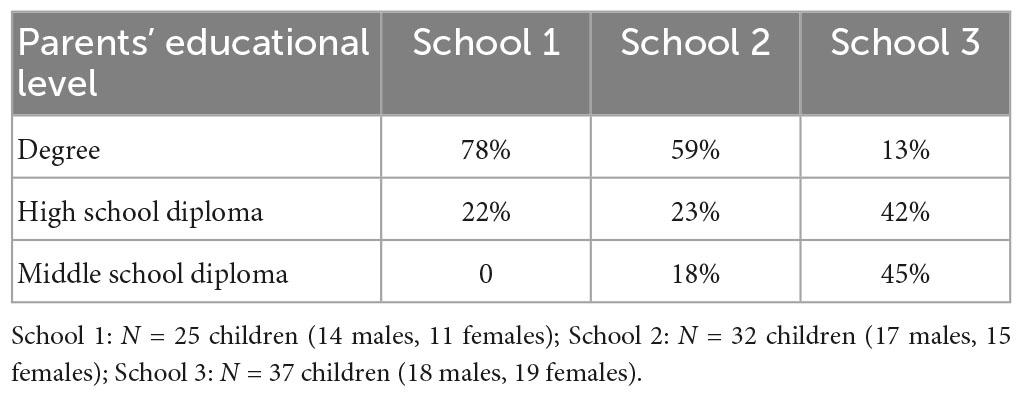

The research involved 94 children, 49 boys and 45 girls (M-age = 5 years and 8 months), all attending three different preschools located in a city of central Italy. The schools involved in the research are three municipal preschools in the municipality of Arezzo and located in different areas of the city: School 1 (25 pre-schoolers – 14 males, 11 females), School 2 (32 pre-schoolers – 17 males, 15 females), School 3 (37 pre-schoolers – 18 males, 19 females). The children in School 1 had grown up in a more culturally elevated environment than the children in the other schools. Table 1 shows sample distribution across schools. All the children showed typical development, were born in Italy, and spoke Italian as their mother tongue. At the time of the study, no participant had a diagnosis of physical or mental disability or had begun a diagnostic evaluation process or, according to teachers, presented a special educational need. The three preschools have a catchment area where the parents come from different socio-economic backgrounds. The association between children’s responses and the type of preschool and socio-cultural information from parents were analysed. We checked that all schools included in this study adhere to the standard national curriculum in accordance with the Italian national guidelines issued by the Ministry of Education. Children attending the last year of the preschool class were exposed to different forms of written language (words, posters, signs and books, etc.) but not explicitly taught the grapho-phonological code. Data collection in classrooms took place at the end of the school year during the month of May.

Table 1. Percentages of the educational qualifications of the children’s parents who participated in the research.

2.2. Procedure and measures

Three administrations were performed within one-week of time. In the first administration, at the first meeting with the children, the work was presented collectively, explaining to them that this work was not used to judge them but to help the teachers who they would meet at primary school to decide on the best way for them to learn to read and write; it was also explained to them that such work had to be done individually in a quiet place beside the classroom. Following the general illustration phase, each child was presented individually with the target word and asked the question: “Could you tell me what is written on this card?”.

The task material consists of six stimulus words chosen from a larger list of words (including toy brands and cartoon characters after having checked the copyrights) through a recognition task performed in a pilot study on 23 children (13 females and 10 males) not included in the final sample used in this research. We subjected 23 children to 14 target logos of the following 14 words: Walt Disney, Nutella, Kinder, Fiesta, Playmobil, Barbie, Action Man, Nemo, Madagascar, Shrek, Estathe, Gormiti, Winx. Those stimuli belong to specific categories such as snacks, names of toys or cartoons, easily recognisable by the children as every-day and familiar stimuli. From these stimuli presented to the pilot sample, we chose the most recognised and familiar ones, therefore the six words used in the research were the following logos:

1.  indicating one of the main characters of the computer-cartoon called “Finding Nemo” and “Finding Dory”;

indicating one of the main characters of the computer-cartoon called “Finding Nemo” and “Finding Dory”;

2.  indicating the computer-animated survival comedy film;

indicating the computer-animated survival comedy film;

3.  indicating the computer-animated comedy film;

indicating the computer-animated comedy film;

4.  indicating a brand of tea;

indicating a brand of tea;

5.  indicating a toy brand;

indicating a toy brand;

6.  indicating an animated fantasy series.

indicating an animated fantasy series.

Only those children recognising the target word at the first administration were subsequently presented with the modified versions of the word as described below.

In the second administration, the six modified versions of target words with a change in the central letters (e.g.,  ) were presented to those pre-schoolers who had previously recognised the original graphic version of the word and they were asked to say what was written in them.

) were presented to those pre-schoolers who had previously recognised the original graphic version of the word and they were asked to say what was written in them.

In the third and last administration, pre-schoolers were asked to read the six modified versions of target words with the change to initial/final letters (e.g.,  ) and then in the graphic form in capital letters without logos (i.e., NEMO, MADAGASCAR, SHREK, ESTATHÉ, GORMITI, WINX).

) and then in the graphic form in capital letters without logos (i.e., NEMO, MADAGASCAR, SHREK, ESTATHÉ, GORMITI, WINX).

For the modified versions of the target words in the central letters and in the initial/final letters, the child’s types of reading were coded as described in the following:

• NOTATIONAL AWARENESS (NA): assigned when the child reads the modified word correctly via a “Sound-sign processing when reading”, e.g., child reads the word correctly as it is written and reads the modified word “Sadagascar”. This indicates the child’s ability to read the word correctly in its original form and modified versions.

• EMERGENT NOTATIONAL AWARENESS (ENA): when presented to children the original version or modified versions of the target word, e.g., child realises that there is something dissonant in the modified words and does not read by saying, for example, that they do not recognise the word because “it has a little letter that is not the right one”. This indicates the child’s sensitivity to the variation of the pattern of letter or graphic form denoting the early emergence of notational awareness (e.g., the modified version “NOMO” of the original word “NEMO”).

• LOGOGRAPHIC RECOGNITION (LR): assigned when the modified word was read as it was correctly written, e.g., child reads “Madagascar” where “Sadagascar” was written. This indicates that children continue to use logographic processing in reading the modified versions of words as if they were written correctly in their basic form (thus not noticing the changes made and relying only on the graphical aspects, thus committing reading errors).

For the modified versions of the target words in the graphic form in capital letters without logos, the children’s types of reading were coded as described in the following:

● YES: when children read

● NO: when children do not read

2.3. Data analysis

To perform the analyses on the logos modified in the middle letters and in the beginning and ending letters, we distinguished two categories of scores: (1) children who read through logographic recognition, and (2) children who had notational awareness or emergent notational awareness of the word.

Preliminarily, the sample distribution across schools and parental educational level were calculated. Regarding the first aim, frequencies and percentages for the type of reading manifested by the children when reading the original and modified versions of words were calculated, also in relation to the three different preschools. The Chi-Square Goodness-of-Fit Test was used to compare observed and expected frequencies in each category. The proportion of cases expected in each group of the categorical variable can be equal or unequal (Balakrishnan et al., 2013). In view of this, we expect there to be differences in the variables considered for our sample. Values with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Then, a Chi-square test was used to verify if there are differences between the words with a transparent orthography (i.e., Italian) and the words with an opaque orthography (i.e., English).

Regarding the second aim, Chi-square tests were used to verify the association between the type of reading presented by the children in relation to the type of school and socio-cultural information from parents. In addition, Bonferroni’s method with adjustment of p value for comparison of column proportions was used. Values with p < 0.05 were considered significant. Further corrections for multiple comparisons are not necessary if there are three groups being compared, since the degrees of freedom have already been taken into account (Shaffer, 1986). In the case of significance, Phi or Cramer’s V values were calculated. Phi is a measure of the strength of association between two categorical variables in a 2 × 2 contingency table. Whereas, Cramer’s V is an alternative to Phi in tables larger than 2 × 2. Both coefficients range between 0 and 1 with no negative values. Thus, a value close to 0 means that there is no association. However, a value above 0.25 is considered a very strong relationship for Cramer’s V. In line with Liebetrau’s (1983) interpretations, the following cut-offs can be defined: > 0.25 Very strong; > 0.15 Strong; > 0.10 Moderate; > 0.05 Weak; > 0 None or very weak.

3. Results

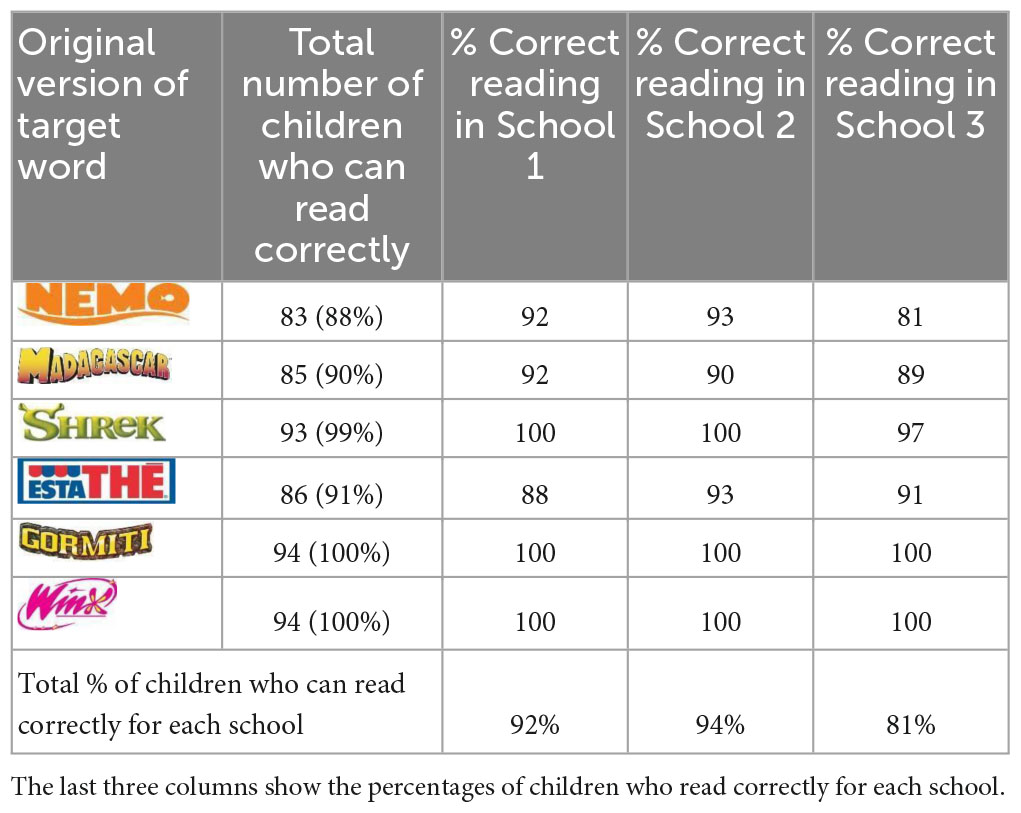

First, to examine the sample distribution, a Chi-square test was performed. The percentages of parental educational level show that School 1 has a significantly higher percentage of children’s parents with a university degree, in comparison with School 2 and School 3 [χ2(4) = 31.82, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.41]. Table of percentages was reported in Participants section. At the preliminary administration of the original versions of the six logos, the results showed that almost all pre-schoolers correctly read the logos with a percentage ranging from 83 to 100%, as detailed in Table 2. At this stage, pre-schoolers who read the logo correctly could be children in the logographic phase who read the logo correctly as a result of recognition of words based on visual cues or children who read the logo correctly as a result of sound-sign processing. This step was useful to verify that the majority of pre-schoolers could continue in the subsequent research steps that better clarify the type of processing used by pre-schoolers to read words.

Table 2. Number of children who read the words correctly in their original form and their percentages.

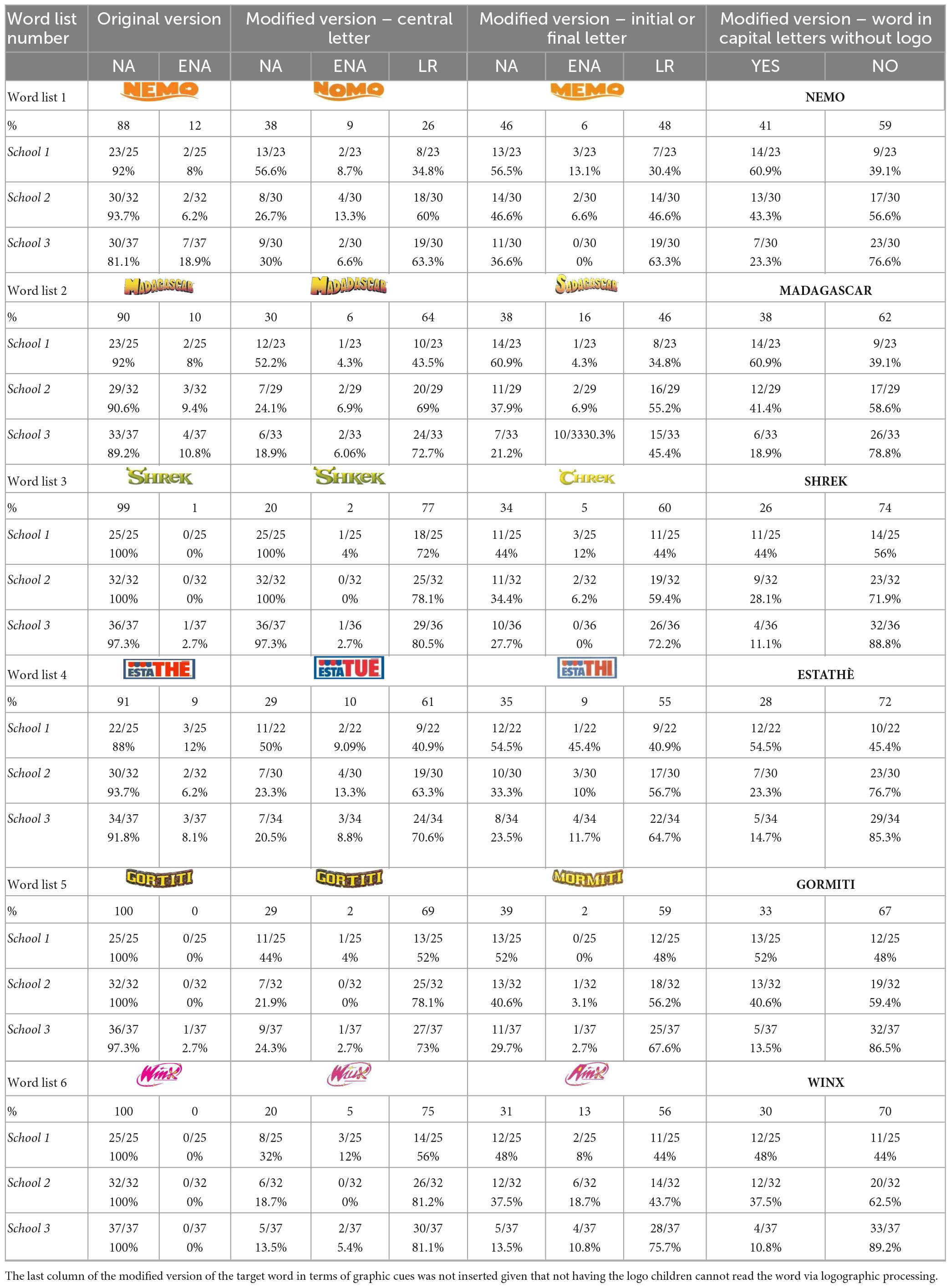

Regarding pre-schoolers’ ability to correctly read the modified versions of logos, Table 3 reports the results of the frequency percentages of reading types for each modified version of the six target logos (NA - Notational Awareness; LR - Logographic recognition; ENA - Emergent Notational Awareness). The results of the Chi-Square Goodness-of-Fit Test show statistically significant differences in some categories.

Table 3. Frequency rates for the reading type for each version of the target word (original or modified) and frequencies and percentages according to the school attended.

Specifically, the results show that in the case where logos were changed in the central letters statistically significant differences in favour of reading with logographic recognition were found in the following stimuli: Madagascar [χ2(1) = 6.86, p < 0.01]; Shrek [χ2(1) = 31.82, p < 0.001]; Estathé [χ2(1) = 3.76, p < 0.05]; Gormiti [χ2(1) = 13.79, p < 0.001]; and, Winx [χ2(1) = 22.51, p < 0.001]. At the same time, statistically significant differences were found in favour of children correctly reading the word regardless of the logo or not reading because they notice the logo change in the following stimulus compared to those children reading in logographic: Nemo [χ2(1) = 54.08, p < 0.001].

On the other hand, in the case of logo modification in the initial and final letters, in all stimuli, it is observed that the proportion of children who read logographically does not differ statistically from those with notational awareness. Except for Shrek [χ2(1) = 3.88, p < 0.05]; in this case, frequency comparison shows that statistically, most children read through logographic recognition.

Finally, statistically significant differences were observed in reading the word capital letters of the logo in all stimuli: Madagascar [χ2(1) = 4.76, p < 0.05]; Shrek [χ2(1) = 21.77, p < 0.001]; Estathé [χ2(1) = 16.79, p < 0.001]; Gormiti [χ2(1) = 10.89, p < 0.001]; and, Winx [χ2(1) = 14.09, p < 0.001], except for the Nemo stimulus. In all cases, most of the children did not read the modified word in capital letters without the logo.

To verify if there are differences between the Italian words and English words, first, we selected the most frequently read Italian word and we compared it with the most frequently read English word. Among the words with transparent spelling, most children correctly read the word Nemo (41%), followed by the words: Madagascar (38%), Gormiti (33%) and Estathe (28%). Among the opaque spelling words, most children correctly read the word Winx (30%), followed by the word Shrek (26%). The two most easily recognised words were selected: Winx and Nemo. The results of the Chi-square test show that there is a statistically significant difference between the two words [χ2(1) = 59.15, p < 0.001].

Regarding the second aim, the frequency and percentages of reading types of the modified versions of the six target logos (NA – Notational Awareness; LR – Logographic recognition; ENA – Emergent Notational Awareness; for modified word in capital letters: YES – reads correctly; NO – does not read) across the three preschool types of school are shown in Table 3. Results of the Chi-square test with Bonferroni’s method with adjustment of p value show that there is no significant association between school type and the reading of the original logo, nor between school type and the reading of the logo when the change is made in the middle letters. Regarding the reading of the logo with changes in the initial and final letters, there are no significant associations with school type except for the following stimuli: Madagascar [χ2(4) = 14.86, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.30] and Winx [χ2(4) = 12.43, p < 0.05, Cramer’s V = 0.26]. The results showed that in all cases the association was between reading of the logo with changes in initial and final letters with School 1.

On the other hand, the results show strong associations between school type and logo reading in word in capital letters. Specifically: Nemo [χ2(2) = 7.70, p < 0.05, Cramer’s V = 0.30]; Madagascar [χ2(2) = 10.27, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.35]; Shrek [χ2(2) = 8.47, p < 0.05, Cramer’s V = 0.30]; Estathé [χ2(2) = 11.02, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.36]; Gormiti [χ2(2) = 11.28, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.35]; and, Winx [χ2(2) = 12.62, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.37]. The results showed that in all cases the strongest association was between correct reading of word in capital letters with School 1, compared to those who do not read.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the emergence of sign-sound correspondence, named notational awareness, in Italian-speaking 5-year-old pre-schoolers. Studies in the Italian language system (Pinto et al., 2012, 2017; Bigozzi et al., 2016a,b) and in other orthographies (Treiman and Kessler, 2013; Puranik et al., 2014) indicate that sign-sound correspondence achievement is a key skill for the development of children’s reading and writing skills. In accordance with the literature (Garcia-Mila et al., 2004), we assumed that notational awareness needs to be constructed by young children along a process that sees the production, reflection, and interpretation of one’s own notations (e.g., invented spelling activities) and notations provided by the surrounding world (e.g., preschool and home environment) and others (e.g., educators and parents). The literature (Frith, 1986) states that children around age 5 are in the logographic phase. Our results contribute to further explore the logographic phase as a window into the emergence and early development of sound-sign processing when decoding words in 5-year-old pre-schoolers acquiring a transparent language like Italian and when notational awareness fully takes over.

Regarding the first aim of evaluating and comparing the type of reading in Italian-speaking pre-schoolers, it is interesting to observe that the results show a consistent part of pre-schoolers able to use the sign-sound correspondences when decoding the modified versions of logos. The correct reading of words with modification in the central letters is around 29% of the sample for the target words  ,

,  ,

,  and goes as high as 36% for the word

and goes as high as 36% for the word  . Words with a lower percentage of correct reading are

. Words with a lower percentage of correct reading are  and

and  with a correct reading percentage of around 20%. The literature (see Frith, 1986) informs us that children around the age of 5 are in the logographic phase given that they are able to recognise words by relying on visual and contextual cues without decomposing the words into smaller units and spell on a letter-by-letter basis. Our results add to the inspection of the logographic phase by showing a more complex pattern of reading profiles. Our results, indeed, showed the large presence of 5-year-old pre-schoolers with a high notational awareness that allows sign-sound processing before school entry because they read the word correctly despite still having retained the logo without being fooled by the logo, thus attributing the correct sound to each sign or other pre-schoolers who report that they cannot read because they realise that some letters have changed and therefore still do not get fooled by the logo showing an emergent level of notational awareness.

with a correct reading percentage of around 20%. The literature (see Frith, 1986) informs us that children around the age of 5 are in the logographic phase given that they are able to recognise words by relying on visual and contextual cues without decomposing the words into smaller units and spell on a letter-by-letter basis. Our results add to the inspection of the logographic phase by showing a more complex pattern of reading profiles. Our results, indeed, showed the large presence of 5-year-old pre-schoolers with a high notational awareness that allows sign-sound processing before school entry because they read the word correctly despite still having retained the logo without being fooled by the logo, thus attributing the correct sound to each sign or other pre-schoolers who report that they cannot read because they realise that some letters have changed and therefore still do not get fooled by the logo showing an emergent level of notational awareness.

For an effective use of the sound-sign processing children must represent the information in symbols and operate a matching between grapheme and phoneme (Ravid and Tolchinsky, 2002). In transparent orthographies like Italian, this sound-sign matching is biunivocal despite what happens in opaque orthographies in which the grapheme level does not match the oral version of the word (Caravolas, 2013).

Regarding the modified version  in the central letters of the target word

in the central letters of the target word  , our results showed a high proportion of pre-schoolers who have overcome the logographic processing and realise that one or more graphemes have been modified by using the sound-sign processing. There is also an interesting number of children showing the emergence of the sound-sign correspondence; indeed, some pre-schoolers realise that there is something dissonant in the modified words and do not read by saying for example that they do not recognise the word because “it has a little letter that is not the right one” or “this letter I don’t know how to say…”, thus still noticing a change and informing us about their paying attention to the individual letters that make up the word. It could be also possible that the four letters, fully capitalised may facilitate young children’s recognition and sound-sign processing given the decreased cognitive demands required for decoding words (Ober et al., 2020).

, our results showed a high proportion of pre-schoolers who have overcome the logographic processing and realise that one or more graphemes have been modified by using the sound-sign processing. There is also an interesting number of children showing the emergence of the sound-sign correspondence; indeed, some pre-schoolers realise that there is something dissonant in the modified words and do not read by saying for example that they do not recognise the word because “it has a little letter that is not the right one” or “this letter I don’t know how to say…”, thus still noticing a change and informing us about their paying attention to the individual letters that make up the word. It could be also possible that the four letters, fully capitalised may facilitate young children’s recognition and sound-sign processing given the decreased cognitive demands required for decoding words (Ober et al., 2020).

Regarding the modified version in the initial/final letters, the results of the comparisons of Italian-speaking 5-year-old pre-schoolers’ reading type confirm the pattern previously described given that there is an important proportion of pre-schoolers reading correctly or not reading, thus manifesting the sound-sign correspondence achieved or at its emergence. A child who, smiling with amusement at the reading of the word  in the modified form, said: “Mormiti!….that’s wrong,…you can’t write Gormiti with an M”, demonstrating that his attention was entirely devoted to the letters. Our results are in line with Coltheart’s (1981) theory according to which 5-year-old children operate for the recognition of words as a particular sequence of letters, thus making them capable of detecting changes made at the alphabetical level. Those pre-schoolers using sound-sign processing also confirm the tendency in easily recognising the initial and final sounds of words (Pinto, 2003), while other pre-schoolers show a still dominant logographic recognition via visual cues even when the word is altered in its salient initial or final components. This is particularly evident for the word list “Shrek”, in fact, our results pointed out that most children read its modified version in initial/final letters as the original logo, thus logographic processing remains dominant in this case. One explanation may be that the characteristics of the word

in the modified form, said: “Mormiti!….that’s wrong,…you can’t write Gormiti with an M”, demonstrating that his attention was entirely devoted to the letters. Our results are in line with Coltheart’s (1981) theory according to which 5-year-old children operate for the recognition of words as a particular sequence of letters, thus making them capable of detecting changes made at the alphabetical level. Those pre-schoolers using sound-sign processing also confirm the tendency in easily recognising the initial and final sounds of words (Pinto, 2003), while other pre-schoolers show a still dominant logographic recognition via visual cues even when the word is altered in its salient initial or final components. This is particularly evident for the word list “Shrek”, in fact, our results pointed out that most children read its modified version in initial/final letters as the original logo, thus logographic processing remains dominant in this case. One explanation may be that the characteristics of the word  which has a lower-case letter and is not an Italian word that does not facilitate young children’s recognition and sound-sign processing. Our results show that children performed sound-sign processing significantly more when reading the word Nemo that is a disyllabic word that follows the sound-sign transposition as in Italian in comparison to the word Winx that contains letters not present in the Italian alphabet.

which has a lower-case letter and is not an Italian word that does not facilitate young children’s recognition and sound-sign processing. Our results show that children performed sound-sign processing significantly more when reading the word Nemo that is a disyllabic word that follows the sound-sign transposition as in Italian in comparison to the word Winx that contains letters not present in the Italian alphabet.

Finally, regarding the modified words written in capital letters without the logo, the results confirmed that a great proportion of 5-year-old children can read the word via sound-sign processing, while others who cannot read indicate that they are developing notational awareness. As highlighted in the literature, it is better to conceive the achievement of the sound-sign correspondence as a developmental process during which several phases mark the differential emergence of representational systems (Yamagata, 2007).

For what concerns the second aim, we assumed that preschool curriculum and home literacy practices may enhance pre-schooler’s achievement of the sound-sign correspondence which is at the basis of later reading and writing acquisitions (Incognito et al., 2021; Bigozzi et al., 2023, in press). We thus decided to analyse the existence of differences in type of reading in the light of socio-cultural characteristics pertaining to preschools and parents’ levels of education. A preliminary inspection of data showed that School 1 reported a significantly higher percentage of children’s parents with a university degree, in comparison with School 2 and School 3, meanwhile School 3 reported a significantly higher percentage of high-school diploma and middle-school diploma in comparison to School 2 and School 1. The results of the comparisons showed an association between correct reading type and School 1 in comparison to School 2 and School 3. Especially in the last phase of the research, the results of School 1 stand out positively in terms of the number of correct answers, in fact more than half of the children in this school read the word written in block letters correctly. The results of the χ2 test show an association between School 1 and the ability to read the modified words written in capital letters without the logo. A closer look at data shows that in School 1 the great majority of parents have a University Degree and the other part have a High-School Diploma, while no parents have a Middle-School Diploma. In School 2 the number of graduates decreases even more dramatically in School 3 where 45% of parents have a High-School Diploma and only 13% have a University Degree. Therefore, these results confirm that there is an influence of the socio-cultural level of parents. Growing up in a rich environment in terms of literacy materials and experiences contribute to pre-schoolers’ emergent literacy skills development (Incognito and Pinto, 2021) and word recognition (Evans and Shaw, 2008).

These findings, while exploratory and preliminary in nature, extend our limited understanding about the emergence of sign-sound processing in Italian-speaking 5-year-old pre-schoolers. The sign-sound correspondence achievement in pre-schoolers is critical for later reading and writing development (Tijms et al., 2020). Our results have educational implications by highlighting that literacy acquisition experience may promote young children’s awareness of sound-sign correspondence. As suggested in the literature, there is a high probability that high levels of education in parents are associated with higher home literacy environments and practices. The results from the current study indicate that the home literacy environment and practices promote children’s early literacy skills, such as notational awareness. Thus, parents should encourage children in joint reading and writing activities at home or invented reading and invented spelling practices, which require many important skills such as the use of grapheme-phoneme correspondence or the early letter knowledge and their word meaning. Previous research conducted in the Italian context suggests that helping pre-schoolers to link letters with their corresponding sounds benefits their notational awareness (Incognito et al., 2021; Bigozzi et al., 2023, in press). Also, as suggested by Coltheart (1981), it is important to expose the child to words and logos to facilitate their knowledge and storing in memory. Finally, the results from the current study indicate that implementing research-based programmes, such as Promoting Sound Sign Achievement (PASSI; Pinto et al., 2018), can be effectively fostered during the preschool years of notational awareness, particularly with educators’ guidance and peers’ involvement in small group activities.

4.1. Limitations and future research

The children observed in this study were a group of 5-year-old children. Future longitudinal studies which will include a larger sample of young children are needed. A longitudinal research design will help to gain a more comprehensive view of the phase in which children disentangle logographic and sound-sign processing. Moreover, given the results indicating that children’s type of reading varied in relation to sociocultural status pertaining to type of school and parents’ educational level, it is important for future research to be able to generalise to other populations of children the results from this study. In this respect, a more detailed examination of children’s home literacy environment and practices would be useful to verify similarity across cultures and orthographies in terms of how parents support children’s sound-sign correspondence achievement. The disentanglement between logographic and sound-sign correspondence in pre-schoolers might show different patterns of development in a cross-linguistic perspective. The acquisition of the English language, which is a language with an opaque orthography whose letter-sound correspondence relations do not have a coherent pattern, presents different difficulties and different developmental trajectories compared to Italian, which, being a language with a transparent orthography, is characterised by regular letter-sound correspondences.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Florence. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albuquerque, A., and Alves Martins, M. (2022). Invented spelling as a tool to develop early literacy: The predictive effect on reading and spelling acquisition in Portuguese. J. Writ. Res. 14, 113–131. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2022.14.01.04

Aro, M., and Wimmer, H. (2003). Learning to read: English in comparison to six more regular orthographies. Appl. Psycholinguist. 24, 621–635. doi: 10.1017/S0142716403000316

Balakrishnan, N., Voinov, V., and Nikulin, M. S. (2013). Chi-squared goodness of fit tests with applications. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Bastien-Toniazzo, M., and Jullien, S. (2001). Nature and importance of the logographic phase in learning to read. Read. Writ. 14, 119–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1008138931686

Bigozzi, L., Tarchi, C., Caudek, C., and Pinto, G. (2016a). Predicting reading and spelling disorders: A 4-year cohort study. Front. Psychol. 7:337. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00337

Bigozzi, L., Tarchi, C., Pezzica, S., and Pinto, G. (2016b). Evaluating the predictive impact of an emergent literacy model on dyslexia in Italian children: A four-year prospective cohort study. J. Learn Disabil. 49, 51–64. doi: 10.1177/0022219414522708

Bigozzi, L., Vettori, G., and Incognito, O. (2023). The role of kindergartners’ home literacy environment and emergent literacy skills on later reading and writing skills in primary school: A mediational model. Front. Psychol. 14:1113822. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1113822

Bishop, A. G. (2003). Prediction of first-grade reading achievement: A comparison of fall and winter kindergarten screenings. Learn. Disabil. Q. 26, 189–200. doi: 10.2307/1593651

Caravolas, M. (2013). “Learning to spell in different languages: How orthographic variables might affect early literacy,” in Handbook of orthography and literacy, eds R. M. Joshi and P. Aaron (Milton Park: Routledge), 511–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01725.x

Coltheart, M. (1981). Disorders of reading and their implications for models of normal reading. Visible Lang. 15, 245–286.

Ehri, L. C. (2020). The science of learning to read words: A case for systematic phonics instruction. Read. Res. Q. 55, 45–60.

Ellis, N., and Large, B. (1988). The early stage of reading: A longitudinal study. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2, 47–76.

Evans, M. A., and Shaw, D. (2008). Home grown for reading: Parental contributions to young children’s emergent literacy and word recognition. Can. Psychol. 49, 89–95. doi: 10.1037/0708-5591.49.2.89

Frith, U. (1986). A developmental framework for developmental dyslexia. Ann. Dyslexia 36, 67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02648022

Garcia-Mila, M., Marti, E., and Teberosky, A. (2004). Emergent notational understanding: Educational challenges from a developmental perspective. Theory Pract. 43, 287–294. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4304_7

Hall, A. H., Simpson, A., Guo, Y., and Wang, S. (2015). Examining the effects of preschool writing instruction on emergent literacy skills: A systematic review of the literature. Lit. Res. Instr. 54, 115–134.

Hand, E. D., Lonigan, C. J., and Puranik, C. S. (2022). Prediction of kindergarten and first-grade reading skills: Unique contributions of preschool writing and early-literacy skills. Read. Writ. 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s11145-022-10330-1

Harris, M., and Coltheart, M. (1986). Language processing in children and adults: An introduction. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. Trad. It. L’elaborazione del linguaggio nei bambini e negli adulti. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Incognito, O., and Pinto, G. (2021). Longitudinal effects of family and school context on the development of emergent literacy skills in preschoolers. Curr. Psychol. 42, 9819–9829. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Incognito, O., Bigozzi, L., Vettori, G., and Pinto, G. (2021). Efficacy of two school-based interventions on notational ability of bilingual pre-schoolers: A group- randomized trial study. Front. Psychol. 12:686285. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686285

Kuhn, M. R., Schwanenflugel, P. J., and Meisinger, E. B. (2010). Aligning theory and assessment of reading fluency: Automaticity, prosody, and definitions of fluency. Read. Res. Q. 45, 230–251.

Marinelli, C. V., Romani, C., Burani, C., and Zoccolotti, P. (2015). Spelling acquisition in English and Italian: A cross-linguistic study. Front. Psychol. 6:1843. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01843

Masonheimer, P. E., Drum, P. A., and Ehri, L. C. (1984). Does environmental print identification lead children into word reading? J. Read. Behav. 16, 257–271.

Milburn, T. F., Hipfner-Boucher, K., Weitzman, E., Greenberg, J., Pelletier, J., and Girolametto, L. (2017). Cognitive, linguistic and print-related predictors of preschool children’s word spelling and name writing. J. Early Child. Lit. 17, 111–136. doi: 10.1177/1468798415624482

Missall, K., Reschly, A., Betts, J., McConnell, S., Heistad, D., Pickart, M., et al. (2007). Examination of the predictive validity of preschool early literacy skills. School Psychol. Rev. 36, 433–452. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2007.12087932

Mohamed, M. B. H., and O’Brien, B. A. (2022). Defining the relationship between fine motor visual-spatial integration and reading and spelling. Read. Writ. 35, 877–898. doi: 10.1007/s11145-021-10165-2

Mol, S. E., and Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychol. Bull. 137, 267–296.

Neumann, M. M., Hood, M., Ford, R. M., and Neumann, D. L. (2012). The role of environmental print in emergent literacy. J. Early Child. Lit. 12, 231–258. doi: 10.1177/1468798411417080

Nicholls, A. L., and Kennedy, J. M. (1992). Drawing development: From similarity of features to direction. Child Dev. 63, 227–241.

Ober, T. M., Brooks, P. J., Homer, B. D., and Rindskopf, D. (2020). Executive functions and decoding in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic investigation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 32, 735–763. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09526-0

Ouellette, G., and Sénéchal, M. (2017). Invented spelling in kindergarten as a predictor of reading and spelling in Grade 1: A new pathway to literacy, or just the same road, less known? Dev. Psychol. 53, 77–88. doi: 10.1037/dev0000179

Pinto, G. (2003). Il suono, il segno, il significato. Psicologia dei processi di alfabetizzazione. Roma: Carocci.

Pinto, G., and Incognito, O. (2022). The relationship between emergent drawing, emergent writing, and visual-motor integration in preschool children. Infant Child Dev. 31:e2284. doi: 10.1002/icd.2284

Pinto, G., Bigozzi, L., Gamannossi, B. A., and Vezzani, C. (2009). Emergent literacy and learning to write: A predictive model for Italian language. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 24, 61–78.

Pinto, G., Bigozzi, L., Gamannossi, B. A., and Vezzani, C. (2012). Emergent literacy and early writing skills. J. Genet. Psychol. 173, 330–354. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2011.609848

Pinto, G., Bigozzi, L., Tarchi, C., and Camilloni, M. (2018). Improving conceptual knowledge of the Italian writing system in kindergarten: A cluster randomized trial. Front. Psychol. 9:1396. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01396

Pinto, G., Bigozzi, L., Vezzani, C., and Tarchi, C. (2017). Emergent literacy and reading acquisition: A longitudinal study from kindergarten to primary school. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 32, 571–587. doi: 10.1007/s10212-016-0314-9

Puranik, C. S., Petscher, Y., and Lonigan, C. J. (2014). Learning to write letters: Examination of student and letter factors. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 128, 152–170.

Ravid, D., and Tolchinsky, L. (2002). Developing linguistic literacy: A comprehensive model. J. Child Lang. 29, 417–447. doi: 10.1017/S0305000902005111

Rayner, K., Pollatsek, A., Ashby, J., and Clifton, Jr, C (2012). Psychology of reading. London: Psychology Press.

Rohde, L. (2015). The comprehensive emergent literacy model: Early literacy in context. Sage Open 5:2158244015577664.

Seymour, P. H. K., and Elder, L. (1986). Beginning reading without phonology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 3, 1–37.

Shaffer, J. P. (1986). Modified sequentially rejective multiple test procedures. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 81, 826–831.

Spencer, L. H., and Hanley, J. R. (2004). Learning a transparent orthography at five years old: Reading development of children during their first year of formal reading instruction in Wales. J. Res. Read. 27, 1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9817.2004.00210.x

Tijms, J., Fraga-González, G., Karipidis, I. I., and Brem, S. (2020). The role of letter-speech sound integration in normal and abnormal reading development. Front. Psychol. 11:1441. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01441

Treiman, R., and Kessler, B. (2013). Learning to use an alphabetic writing system. Lang. Learn. Dev. 9, 317–330.

Valdois, S., Roulin, J., and Bosse, M. L. (2019). Visual attention modulates reading acquisition. Vision Res. 165, 152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2019.10.011

Wang, L., and Liu, D. (2021). Unpacking the relations between home literacy environment and word reading in Chinese children: The influence of parental responsive behaviors and parents’ difficulties with literacy activities. Early Child. Res. Q. 56, 190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.04.002

Whitehurst, G. J., and Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Dev. 69, 848–872.

Yamagata, K. (2007). Differential emergence of representational systems: Drawings, letters, and numerals. Cogn. Dev. 22, 244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2006.10.006

Keywords: literacy acquisition, sound-sign correspondence, emergent literacy, pre-schoolers, notational awareness

Citation: Bigozzi L, Incognito O, Mercugliano A, De Bernart D, Botarelli L and Vettori G (2023) A study on the emergence of sound-sign correspondence in Italian-speaking 5-year-old pre-schoolers. Front. Educ. 8:1193382. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1193382

Received: 24 March 2023; Accepted: 30 May 2023;

Published: 16 June 2023.

Edited by:

Elena Jiménez-Pérez, University of Malaga, SpainReviewed by:

Antonella Marchetti, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyMaria Carmen Usai, University of Genoa, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Bigozzi, Incognito, Mercugliano, De Bernart, Botarelli and Vettori. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giulia Vettori, giulia.vettori@unifi.it

Lucia Bigozzi

Lucia Bigozzi