- Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States

Drawing on scholars of critical theory and pedagogy, we understand power as operating within nested social systems, meaning that individuals experiencing injustice are impacted not only by the most immediate agent of that injustice but also by the broader institutions, policies, and values of their society. The practice of attending to power and how it shapes our societies at multiple levels (i.e., power analysis) is necessary to critical research approaches, including Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR). While adolescents and adults (the age groups most commonly engaging in CPAR) are likely to have developed some understanding of systems of power through experience, dialog, and/or educational experiences, children participating in CPAR have generally had fewer opportunities to develop this type of analysis. In our own CPAR projects with 3rd–5th grade children, we have witnessed the challenges and possibilities of exploring power with child CPAR team members. In this paper, we introduce a methodological tool that we developed to facilitate power analysis during critical research projects like these: The Power Rainbow. The Power Rainbow is a graphic representation of nested systems of power, which can be utilized with children in multiple ways throughout the CPAR process. The tool concretizes the abstract concept of systemic power through shape, color, and text, and scaffolds the type of structural thinking necessary to research and take action towards more just futures.

Introduction

This paper is dedicated to all the child members of the CPAR research teams that inspired The Power Rainbow.1 Thank you for sharing your creativity, imagination, and wisdom with us.

In order to be transformative, educational research and practice must be attentive to how power shapes our societies. Power is a key factor in every issue of (in)justice, operating at multiple levels and playing complex roles shaped by identity and social context. Because of this, the ability to recognize and analyze systems of power is integral to developing a deep understanding of how injustice is perpetuated, as well as how we can work to dismantle it. Awareness of power often emerges through some form of critical education (McLaren and Kincheloe, 2007). However, it is rarely highlighted in pedagogy or media for children, even within progressive and social justice-oriented spaces.

In this paper, we introduce a methodological tool (The Power Rainbow) that we developed and piloted to help children analyze systems of power within Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR)2 projects. CPAR as a research approach is explicitly oriented toward justice, and one of its key tenets is a focus on how power shapes the research topic and process (Torre, 2009; Cammarota and Fine, 2010). While the existing literature provides some models for implementing that focus in CPAR projects with adolescents and adults, engaging in power analysis with children requires a different process. In our CPAR projects with 3rd–5th graders, we found that children needed a structured framework for power analysis that could be embedded in the research process. We will describe how The Power Rainbow fills this methodological need and how the tool has functioned for us in practice.

How to engage with this paper

Throughout this paper, we invite you, the reader, into the creative process and way of being that guides our work. The children we work with remind us that everyone takes different approaches to learning and engaging with ideas, and that none of those approaches is inherently better than others. To honor this, we have structured this paper to reflect our own playful way of thinking and offer multiple ways to engage. Specifically, we have designed the paper as a landscape that is home to four beings who steward the land. Each being engages with this landscape of ideas in different ways, and you can choose one (or more) beings as your guides through the paper. Below, we provide a map of the whole landscape. Then, we name the four beings who can accompany you on your journey.

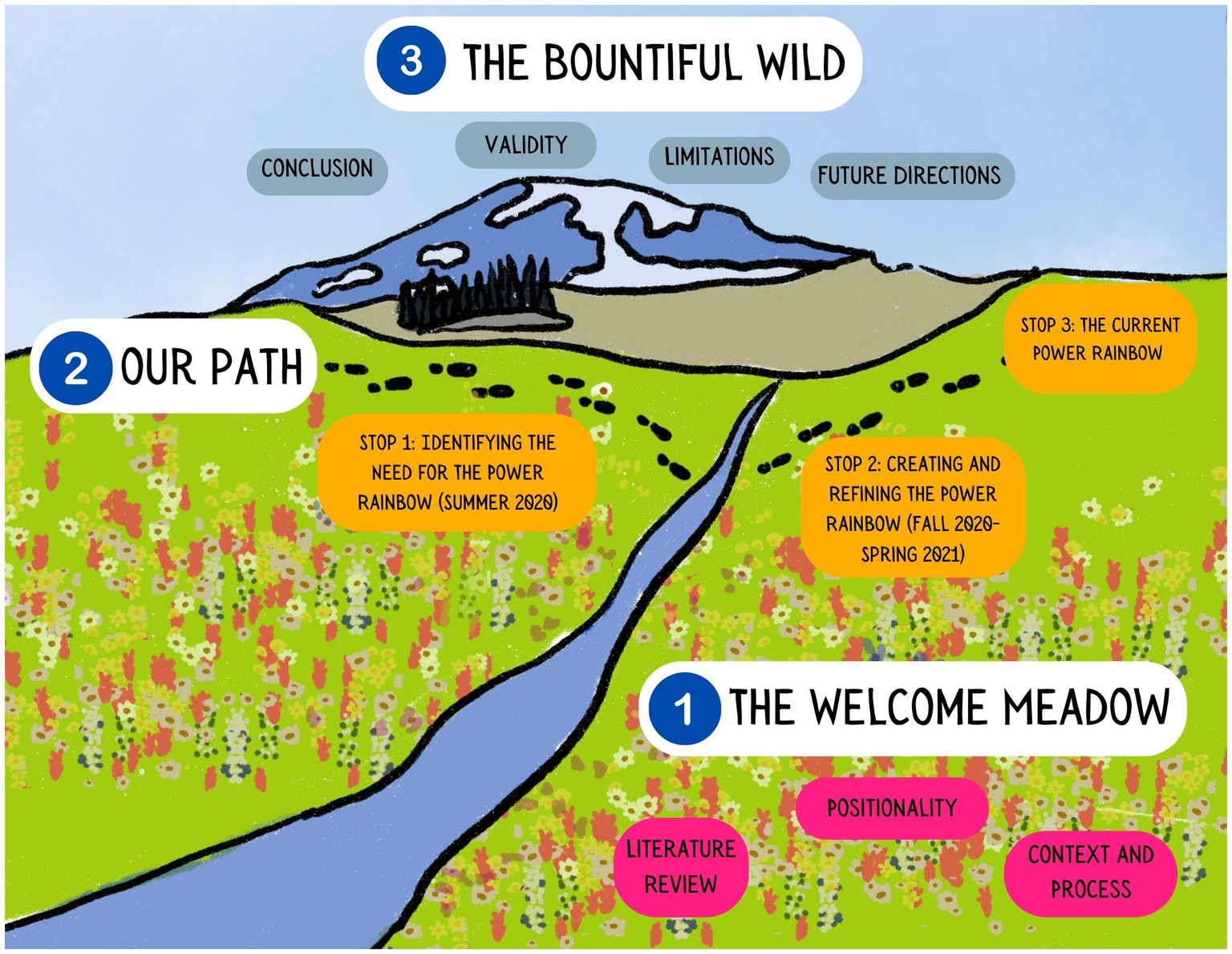

Map of the paper (see Figure 1 for a visual representation):

• The Welcome Meadow (i.e., a place to help you make sense of the paper as a whole)

• Literature review

• Positionality

• Context and Process

• Our Path (i.e., a place where you can trace our journey in creating The Power Rainbow)

• Stop 1: Identifying the Need for The Power Rainbow (Summer 2020)

• Stop 2: Creating and Refining The Power Rainbow (Fall 2020-Spring 2021)

• Stop 3: The Current Power Rainbow and How We Used It (Summer 2021)

• The Bountiful Wild (i.e., a place where you can explore, dream, plan and question beyond what we have done so far)

• Validity

• Limitations

• Future Directions

We invite you to follow this map in the ways that feel most useful for you. Who will be your guide? (See Figure 2 for visual representations of the guides.)

• Tortoise: Tortoise accompanies those who feel studious, reflective and thorough. It makes Tortoise happy to think about following something from beginning to end, digging into all the details along the way. With Tortoise as your guide, start at the beginning (The Welcome Meadow) and read all the way through, pausing along the way to reflect as needed.

• Tree: Tree’s root network accompanies those who are nourished by connection to, and communication with, others. Tree seeks out stories that make them feel rooted in a particular context. With Tree as your guide, start with Positionality, which describes who we are and the communities we are rooted in. Continue onto Context and Process, and then Our Path, to learn about the story of how The Power Rainbow came to be. Read until you feel ready to seek out a friend or community to share your learnings with!

• Beaver: Beaver accompanies those who are ready to build, make, do! Beaver likes to discover new tools but knows they will learn best through experience, by putting those tools into action. With Beaver as your guide, start at Stop 3 to read about what The Power Rainbow is and how we used it. Continue on to Limitations and Future Directions for background information that is useful before you use the rainbow. Then, take the rainbow with you into the world and create!

• Otter: Otter is playful by nature, and is often reading with others (maybe with children). With Otter as your guide, color in your own copy of The Power Rainbow. Talk about it with your companions while you play (see Supplementary material S1).

The Welcome Meadow

Literature review (What existing work are we speaking to?)3

This paper adds to the existing literature documenting methodological tools to support critical and transformative educational research. We4 ground our contributions in the tradition of CPAR, a research approach in which community members and researchers partner to design and implement a research project and subsequently use their findings to take or plan for social action (Cammarota and Fine, 2010; Mirra et al., 2016; Fine and Torre, 2021). As a form of critical research, CPAR projects typically focus on questions of power and inequity in both the research content and process (Bohman, 2016). Our CPAR projects engage children as research team members. Because existing CPAR literature typically focuses on adolescents and adults, this paper therefore also contributes to necessary research providing examples and tools to support younger CPAR participants.

One of the central assumptions within CPAR projects is that “all people and institutions are embedded in complex social, cultural, and political systems historically defined by power and privilege” (Torre, 2009). For the purposes of this paper, we refer to these social, cultural, and political systems as systems of power – i.e., systems that determine how power works to uphold or dismantle injustice in society. Because of this central assumption of CPAR, research team members need to possess (or develop during the research process) the ability to engage with power and how it shapes our lives and societies (Brion-Meisels and Alter, 2018), an ability that we refer to in this paper as power analysis. While some children and youth may have engaged in power analysis prior to participating in CPAR projects (e.g., in academic settings, through activism or organizing work, or with caregivers or adults in their lives), many have not. As a result, adult researchers need tools to support youth in practicing and applying power analysis throughout the research process. This is particularly important in projects involving children (as opposed to adolescents), who are less likely to have had previous experiences with power analysis.

Examples of methodologies to promote power analysis are limited in the existing CPAR literature with children and adolescents. CPAR literature involving adolescents typically focuses on other aspects of CPAR, including how research teams engaged in specific steps of the research process (e.g., identifying a research question, analyzing data) or how they promoted team community-building (Cammarota and Fine, 2010; Mirra et al., 2016). There is less literature published about CPAR with children overall, much of which focuses on the empowerment of children throughout the research process (e.g., Kohfeldt et al., 2011; Langhout et al., 2014; Anselma et al., 2020).

While many CPAR publications note that youth who participated in the projects developed understandings of systems of power in some way (e.g., youth made connections between the power wielded by individuals, institutional agents, institutions, policies and/or cultural forces), these publications seldom describe how that understanding unfolded, or what adults did (if anything) to support or nurture it. However, a few key strategies can be identified from the literature. For example, in one Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) project, adult researchers engaged youth in co-constructing definitions of terms related to their research topics, while ensuring that those definitions implicated power and inequity. This gave research teams a shared vocabulary for discussing which groups have historically been marginalized (Ayala et al., 2018, p. 123). Adult researchers have also shared texts and/or ideas from critical theory with youth CPAR teams. For example, Mirra et al. (2016) explain how they presented youth researchers with writing prompts based on Yosso (2005) concept of community cultural wealth. Activities like these can provide young people with a conceptual framework for how power shapes communities. Finally, creating space to intentionally reflect on power relationships within CPAR teams – and to disrupt power hierarchies when necessary – can support young people and adult researchers in understanding the impacts of systems of power on their own work (e.g., how ageism reinforces the power of adults over youth in academic and research settings) (Brion-Meisels et al., 2020).

One specific methodological tool for engaging in power analysis in CPAR is the Oppression Tree (COCo, 2018). The Oppression Tree has been used in CPAR projects with adolescents to identify roots and symptoms of inequity or injustice, and it has also been adapted by Gretchen Brion-Meisels to include roots and symptoms of liberation as well as oppression (G. Brion-Meisels, personal communication, 2023). The tool is usually used to develop a research focus or question for a CPAR project. To use the tool, adult researchers draw or create a large image of a tree. Then, research team members add leaves to the tree corresponding to visible symptoms of community problems (as well as evidence of community liberation, when including that focus). After identifying these leaves, the research team works to identify root causes and add these as roots of the Oppression Tree. For example, if one visible community issue is poor health, root causes may include a lack of available healthy food or structural barriers to accessing preventative healthcare. Reflecting on root causes in this way points students toward the sources of structural power that inhibit or promote justice, which they can subsequently address through their research and social action. However, while the Oppression Tree supports power analysis, it also relies on youth researchers being able to identify and distinguish between symptoms and root causes, and it does not provide scaffolding for younger children who might not yet possess that ability.

While the examples above were used within CPAR projects involving adolescents, we have identified one notable example of a tool designed for children. The Five Whys method is a tool that has been used outside of CPAR, and which was adopted by Kohfeldt and Langhout (2012) to help 5th grade YPAR team members develop a problem definition for research. The Five Whys is similar to the Oppression Tree in that it focuses on identifying powerful, structural forces that promote or inhibit justice. To use this tool, grown up facilitators ask child research team members to identify a “why” about a problem (e.g., why are toilets in school bathrooms unflushed?) and then brainstorm five possible answers. They select what they believe is the most probable answer, create a “why” question about that answer, and then repeat the process a total of 5 times (although the authors note that it can take more or fewer cycles). The goal is to move children toward a conceptualization of a problem that implicates power at a structural level.

Each of these examples implicate power in valuable ways. However, our method takes a different approach by explicitly naming power as the central idea and, we believe, by making the forces implicated in power analysis more visible and accessible for children. Before diving into The Power Rainbow, we turn to who we are, and how our identities shape our work.

Positionality (Who are we and where are we speaking from?)

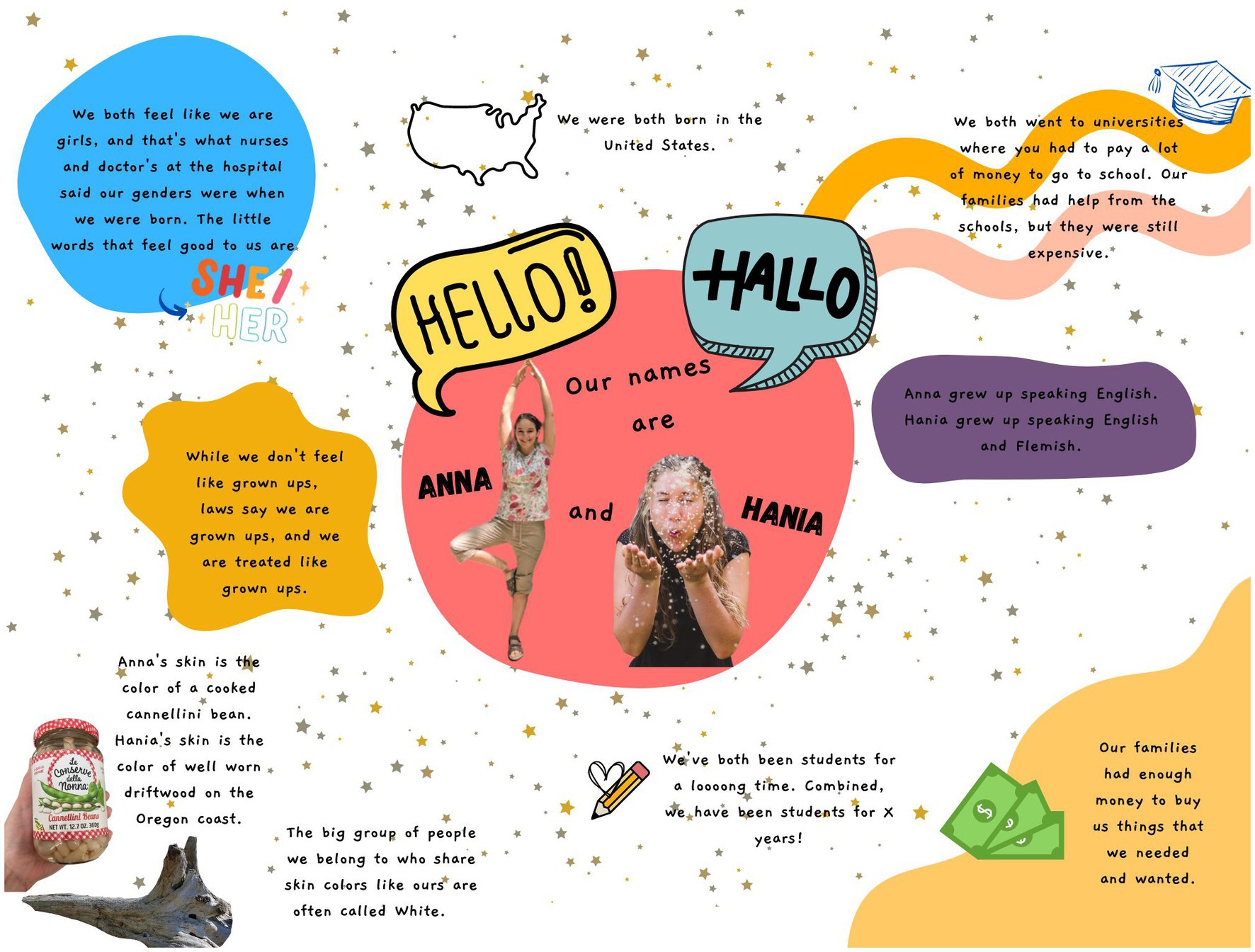

We come at this work with the perspective that who we are matters. It matters because we all have unique gifts we bring to the world, and because our identities shape what we see, hear, feel and notice, as well as how we make sense of those things. We both identify as white, cis, able-bodied, adult women with United States citizenship from birth, raised in upper middle class families, whose families are fluent in English. We both attended predominantly white, private, liberal arts undergraduate institutions, and we are PhD students at a predominantly white graduate institution, the Harvard Graduate School of Education (see Figure 3 for a visual representation).

In our work as CPAR researchers, the injustices we explore with children are often not ones we have experienced directly. Given this, we do our best to bring in the voices of people experiencing particular injustices through books, videos and news stories (adapted for children). We also explore the concept of individual perspective with our child researchers, with the aim of helping us all explore the affordances and limitations of our own perspectives. Throughout our CPAR projects, we emphasize that we care about what the kids have to share. Their thoughts as children matter to us, and we know there are things that we miss or misunderstand as adults. In past camps, we were often able to catch ourselves when we realized that we were imposing our adult ways of working or thinking on the CPAR campers. Sometimes reminders came from the campers themselves, and we took those moments as signs that we had established relationships of accountability.

Our identities as researchers and educators are also shaped by what we have learned from the children and families we have had the privilege to work with; the critical educators we have worked with or whose work we have witnessed and been inspired by; the authors and illustrators whose books fill our bookshelves and feature in our programming; and the activists, organizers, and artists whose work continues to pave the way for all of us invested in the collective work of liberation. The wisdom of these groups has shaped our research process as well as the non-traditional format of this paper. They have instilled in us that play and silliness can co-exist alongside rigorous inquiry and scholarship, which is why both our CPAR projects and this paper incorporate playful elements like art and make-believe. They have highlighted that there are many ways to communicate and engage with ideas, and that words are only one option (not the “best” option). Providing alternatives – like the pathways of the animal guides in this paper – is a way to increase accessibility and invite diverse ways of knowing and being in the world. Finally, our communities have continually reminded us that justice (in the world, in research, and in pedagogy) means not only the absence of inequitable or undue suffering, but also the presence of freedom and joy. Here and in all our work, we aim to engage in ways that foreground hope and the possibility of transformation.

Context and process (What circumstances did this work arise from?)

The Power Rainbow was created and piloted within the context of our virtual Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR) summer camps. We developed the idea for our first CPAR camp in spring and summer 2020, a few months into the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. At the time, children and families were struggling not only with social distancing and isolation, but with school closures and virtual- or home-schooling. Concurrent with the COVID-19 pandemic were brutal acts of racial violence, including George Floyd’s murder, which sparked an increase in visible protests against White Supremacy and policing. Although many media outlets and scholars were highlighting the effects of these events on kids and families – and calling for research to help better understand their experience – few if any of these narratives were co-designed by the kids and families themselves. As researchers committed to CPAR, we suspected that without partnerships with kids and families, emerging research might overlook important questions and perspectives arising from their unique experiences.

We designed a CPAR summer camp (the Imagining More Just Futures Summer Camp) for 3rd–5th grade children to help us better understand their experiences and how they might imagine “a more just future.” We designed the camp for 3rd–5th graders for the following reasons: we both have experience with and enjoy working with this age range; we know that middle childhood is a stage when young people are actively learning and thinking about their identities, relationships, and place in the world (Grusec et al., 2012; Osher et al., 2020); and we know that CPAR and other critical research and pedagogy has not focused on this age range as much as adolescence.

Our first CPAR camp took place in July 2020. Over the following fall, winter and summer, Hania analyzed data from the camp, and we reflected on the camp through conversational, verbal memos. This reflection sowed the seeds for The Power Rainbow, which we piloted during the second year of Imagining More Just Futures Summer Camp, in summer 2021.

For both years of camp, we recruited children through a university-based program providing programming to graduate students with children; several other youth-serving organizations in the greater Boston area; and word of mouth. Before starting camp, we met with participating children and their grown-ups on Zoom to get to know each other and determine how we could best support the individual children who would be part of the team. During each camp, we met with eleven 3rd–5th graders on Zoom, 2–3 times per week over 4 weeks. Sessions were 45–60 min long. In almost every session, the CPAR campers engaged in art and play (e.g., poetry, Play-Doh sculptures, painting); read content-relevant picture books (e.g., books connected to big concepts like research, imagination, or power); and had conversations about social justice. The first five sessions were primarily focused on cultivating relationships, building common vocabulary, and exploring potential topics for our collaborative research. The last five sessions were primarily focused on identifying issues of injustice to research, generating questions for a survey to distribute in campers’ communities, and analyzing survey results to share back in those communities.

The data we collected during our 2020 CPAR camp guided us in creating The Power Rainbow and subsequently writing this methodological paper. That data includes: video recordings of our verbal, conversational memos; curriculum documents and slides from the CPAR camps; photos and recordings of student work from the CPAR camps; recordings of camp sessions; and written notes we took during and after CPAR sessions.

Our analysis method was iterative and inspired by qualitative self-study (Pinnegar and Hamilton, 2009), in that we sought to learn and improve our practice based on structured reflection on our experiences as educators within and between the two CPAR camps. In the months following the summer 2020 camp, Hania analyzed all the data using an arts-based coding methodology (Mariën, 2022, forthcoming). We used the findings from this analysis, as well as multiple rounds of memos, to begin constructing and iterating on versions of the power rainbow (using the process described in depth in Stop 2: Creating and Refining The Power Rainbow). Before writing the current paper, we did another round of analysis. Specifically, we first read/watched through all of the data sources listed above, and pulled out the specific memos, videos, etc. that contained any content relevant to how we discussed (or failed to discuss) structural power, what our campers shared about power, and/or versions of The Power Rainbow. Once we had assembled this subset of data, we used it to assemble a narrative arc, posing the questions: How did the Power Rainbow come to be? How did it offer us a framework, in summer 2021, to address sticking points in children’s understanding about structural power?

Our path

Stop 1: Identifying the need for The Power Rainbow (summer 2020)

When we embarked on designing a CPAR camp with 3rd–5th graders in 2020, power was not one of the concepts we intended to explore explicitly. While we knew that power was one of the foundational ideas underlying CPAR, we intended to use our limited time together to focus instead on ideas like research, justice, and imagination. We thought that power could be present as an assumption implicit in discussions of justice and collaborative research, rather than as an explicit topic of conversation within our research team. However, we found that conceptualizations of power and questions about how it functioned were top-of-mind for our campers.

“I have three injustices,” Chemie Forcherine, one of the youth researchers in our CPAR camp, began. It was 6 days into our camp, and we had asked each of the campers to share the social justice issues they wanted to research. Chemie’s response echoed and pulled together many of the other campers’ suggestions. “The first one is the injustice of racism, that’s “why should people be judged because of different colors of their skin?” The second one is the injustice of people and animals, that people have more power than animals, even though we are just the most knowledgeable animals. And thirdly, the injustice of grownups and children. Since grownups have the power of money and knowledge and transport, they have the power of controlling other people.” When we asked Chemie what she meant by “power,” she said: “power can be good or bad, but if someone who is not for the good has the power, that can be a disaster, because power means you can control other people’s lives.” Before we responded, she continued. “That’s just one example. There’s little power and big power… little power is like if I get to choose what game to play now, big power is let us say you are the president, you are allowed to choose if [pauses] drugs are legal or not.”

The other campers seemed interested in all of Chemie’s “three injustices,” but when they voted to select a single focus, the group was split. Grasping for a way to keep all campers’ interests central to the research, we proposed focusing on the idea that – in Chemie’s words – united them: power.

Suddenly, power became not only an idea embedded in CPAR as an assumption, but an explicit idea that would shape the trajectory of the remainder of the camp. We continued to discuss power abstractly as a research team, at times using art activities and Play Doh to share what power meant to each of us. Building on the campers’ ideas and art, we (Hania and Anna) created a graphic story introducing a framework of “power over” (i.e., power derived from asserting control over others), “power with” (power derived from relationship and collaboration) and “power within” (power derived from who we are).

The research team also explored power through the case study of school segregation, using the picture book Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation by Duncan Tonatiuh. The book uses a narrative format to tell the true story of the 1947 California ruling against public-school segregation, focusing in particular on the experience of Sylvia Mendez. Mendez was banned from enrolling in an Orange County elementary school because of her brown skin and Mexican name, and her family subsequently catalyzed a local movement for school desegregation that helped to bring about the 1947 ruling. We chose Separate Is Never Equal because we thought it made different levels of power particularly clear. In it, we could identify an individual who experienced an injustice (Sylvia); an institutional agent who interacted with that individual (the school secretary who denied Sylvia admission); the institutions that structured those interactions (the school and district); the rules or laws that governed the behaviors of individuals as well as the policies of institutions (the legality of segregation in the beginning of the story, and later the desegregation policy); and the dominant cultural beliefs that shaped everything else (racism, xenophobia, and prejudice against Mexicans and their culture). The book also provides examples of characters using their “power within” and “power with” each other to take social action. However, even in the context of the story, these examples and structures of power were not easily identified by the campers. Again and again, they honed in on specific interactions between individuals (e.g., the conversation in which the school secretary denies Sylvia admission), without recognizing the ways in which these interactions are shaped by larger forces.

We provide the Separate is Never Equal case study as one illustrative example, but this outsized focus on the interpersonal (as opposed to the structural) continued to turn up in campers’ work throughout the CPAR project. While we often attempted to direct campers’ attention to structural forces (e.g., by asking pointed “why” questions, or by reminding campers that individuals like the school secretary in Separate is Never Equal are often following rules or laws made by others), we found that the invisibility of many of these forces made them difficult for campers to grasp – and at the time, we did not have any tools to help make the invisible more visible.

Stop 2: Creating and refining The Power Rainbow (fall 2020-spring 2021)

Following the first summer of Imagining camp, we went through multiple rounds of reflection on the process and what we learned from it. This reflection (described in Context and Process) included a full analysis of our data (including session recordings, memo recordings, pedagogical documents, and research team work) by Hania, as well as more individual written memos and joint conversational memos. We simultaneously began an extended process of brainstorming and planning for a second summer of Imagining More Just Futures camp.

One thing we knew was that we wanted to continue to make power a central and explicit component of our second camp. This choice was driven by the fact that power had been such an engaging topic for our first team of campers. We also knew from our experience with those campers that we would need additional strategies to help children recognize power as something not only wielded by individuals but embedded in multi-level social structures – that is, to help them engage in power analysis. As described above, one of our take-aways from summer 2020 was a “sticking point” in the campers’ thinking about injustice, specifically in their ability to see the connections between interpersonal and structural injustices. As Anna wrote in a memo from August, 2020:

“Often, even when they [the campers] come in with big social justice ideas (e.g., racism), they understand these ideas through interpersonal interactions – how to build the connection between the effects of injustices in the micro, meso, macro, chronosystems they inhabit is tricky. Maybe some intentional Bronfenbrenner-like learning (maybe centered around thinking about “community”?) would be helpful…?”

As evidenced in the quote above, we were beginning to draw on Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory as one way to conceptualize multi-level structures, including structures of power. In the ecological systems model, individuals exist within nested social contexts: a child is nested within a microsystem (comprised of direct social influences like their family and school); which is nested within an exosystem (comprised of indirect social influences like the government, economic system, and media); which is nested within a macrosystem (comprised of the norms and values of the society) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). A graphic of circles-within-circles is often used to illustrate the model.

During this planning period, we also returned to existing power analysis tools that have been used in CPAR projects, including the Oppression Tree (COCo, 2018) and the Five Why’s (Kohfeldt and Langhout, 2012), both of which are described earlier in this paper. While we admired both of these tools, neither were quite what we were looking for. The Oppression Tree, as is, did not provide enough scaffolding for our younger CPAR campers, who were not familiar with the distinction between symptoms and root causes of injustice. The Five Why’s – which has been used successfully with kids at the upper end of our age-range – was a more promising approach. When we considered including it in our camp, though, we felt like it would require a lot of speaking without hands-on elements, which can be challenging for children over Zoom and did not align with our arts- and play-based approach. Reflecting on our experience discussing Separate is Never Equal with campers during Summer 2020, we realized we would need a visual framework or tool that could serve as more of an anchor in conversations like these. Finally, we wanted a strategy that would make power an explicit, central idea as opposed to having the concept of power embedded in “root causes” or “whys.”

We went into the second summer of Imagining More Just Futures camp still considering what that tool could look like, and we spent the first few sessions getting to know the campers, their interests, and their existing understanding of the concept of power. In a Zoom memo a few days before Session 6 – when we were planning to transition from introductory sessions into our CPAR research process – we brainstormed about how to integrate the power analysis that was lacking from our 2020 camp. We discussed various activities: an arts-based power mapping activity for each of their chosen research topics; a comic-making activity in which they could imagine interactions between stakeholders in their topics; and a research-planning activity in which they would brainstorm survey questions for each stakeholder. With each option, we got stuck on how to help them understand that the power of individuals might be shaped by less visible types of power like institutional or governmental policy, capitalism, or racism.

Thinking about less-visible forms of power ultimately brought us back to the idea of a Bronfenbrenner-inspired, nested systems graphic, which could take our research team all the way from the power of an individual to the power of abstract systems like racism. We brought this idea to life as The Power Rainbow, incorporating colorful visuals and imaginative shapes as a nod to the playfulness of our campers.

Stop 3: The current Power Rainbow and how we used it (summer 2021)

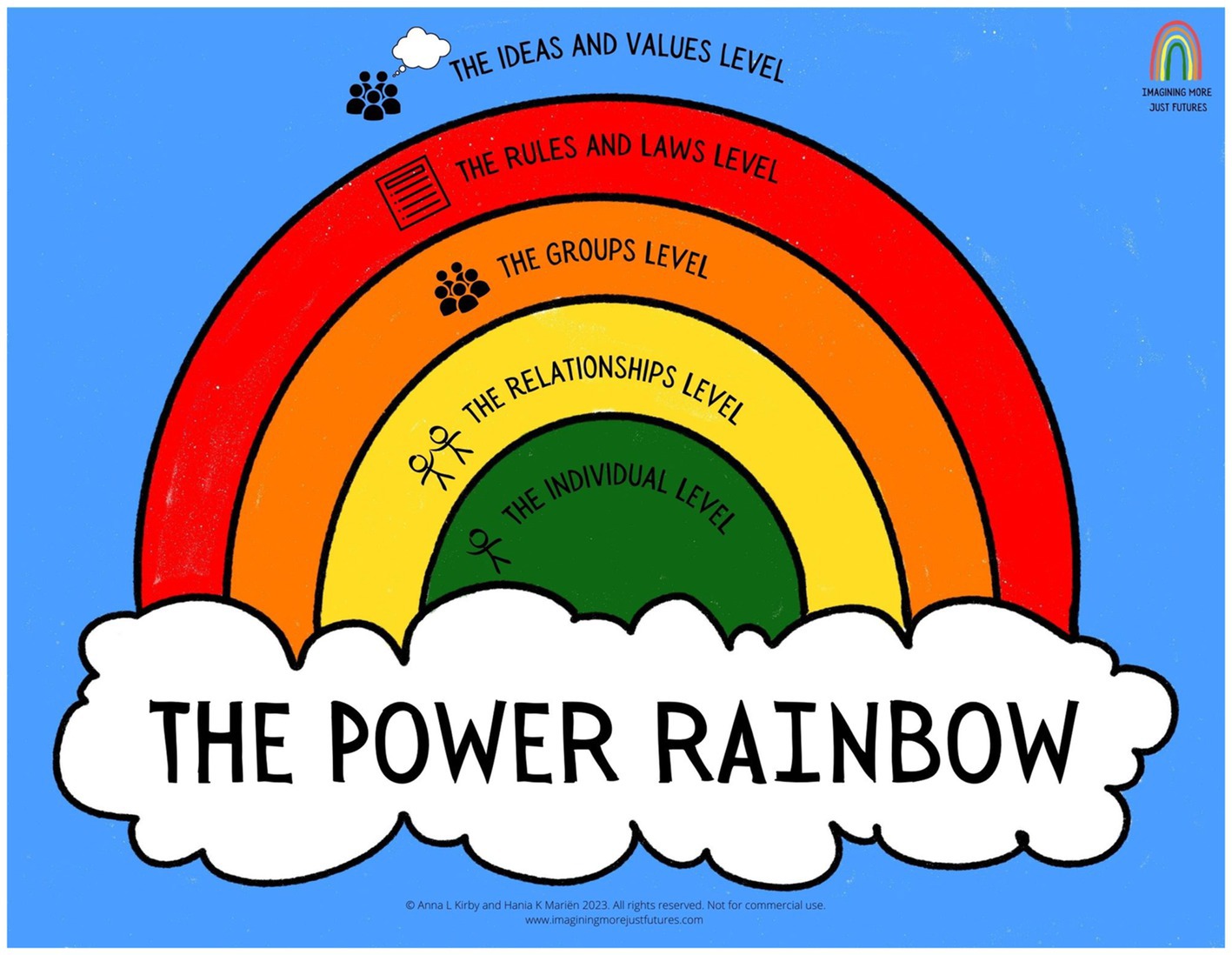

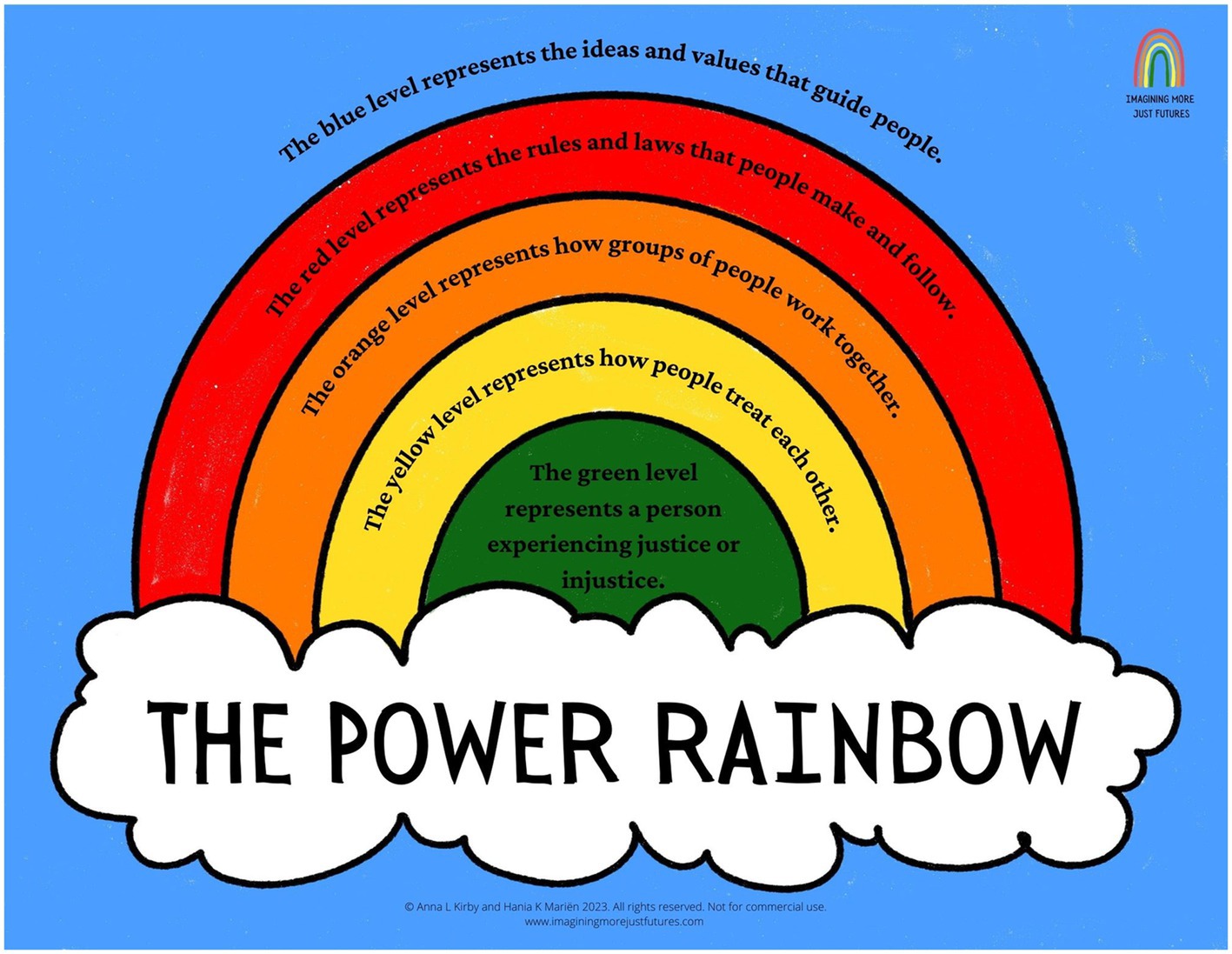

The Power Rainbow is shown in Figures 4, 5. The smallest, center arc of the rainbow (the green level) represents an individual with the potential to experience justice or injustice. This arc is nested within the systems with the power to contribute to that individual’s experience of (in)justice: relationships with other individuals (the yellow level), groups of people or institutions (the orange level), rules and laws (the red level), and finally the ideas and values that shape the collective consciousness of a society (the sky around the rainbow, or blue level).

It took some iteration to arrive at this version of The Power Rainbow. As we developed it, we carefully wrote and rewrote the labels for each level, attempting to describe social structures in a way that was accurate to our understanding, straightforward, and child-friendly. We also discussed how and where to include a circle corresponding to activists/activism, but ultimately decided instead to frame activism as something that could happen within any level (e.g., an activist could do something to support an individual or could try to change a law) and that social movements necessarily cut across all the levels.5

We never conceptualized The Power Rainbow as a static graphic, but rather as a methodological tool that could be put into action throughout a CPAR project. In the following section, we describe how we utilized The Power Rainbow in our second summer of CPAR camp (2021), as a framework for both individual activities and our collaborative research projects (which focused on learning about justice for animals and justice for patients in the healthcare system, respectively).

We started our conversation about power, and introduced The Power Rainbow, during Session 6. The campers loved riddles, so we created a riddle to lead them to the word power: There are electric plants that make me. In the world, adults and teachers often have me, but kids usually do not have a lot of me in comparison. What am I? Once the campers arrived at the answer, we asked them what they thought power meant. Some of their answers included:

• “Power can be like your phone uses, like a superpower that superheroes use, or like ‘you are super good at this.’”

• “Like you have the power to do something, like change a law.”

• “A teacher has power over their students because they are in charge.”

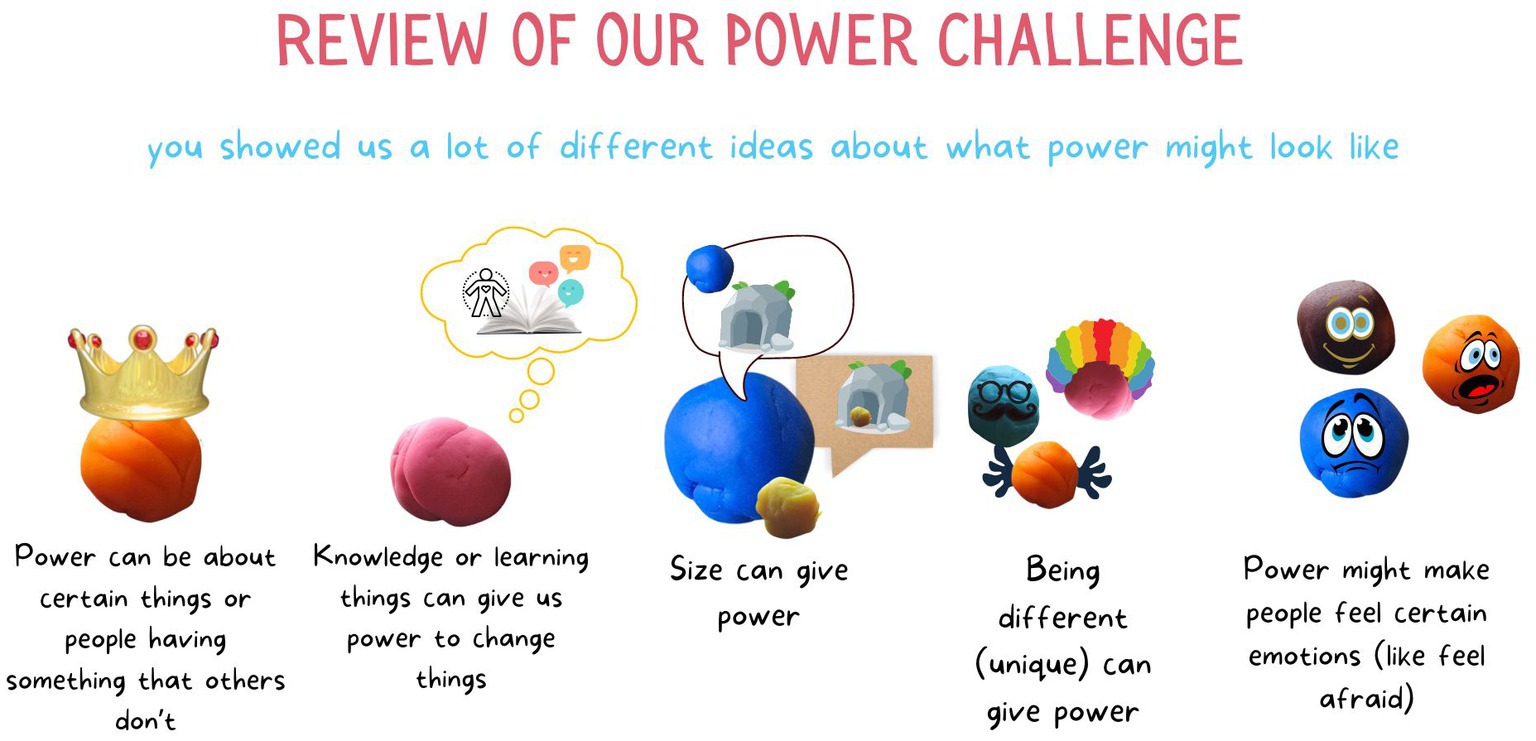

As facilitators, we offered one other way of thinking about power, as the ability to make things happen the way you want them to (Saunders et al., 2019). We also highlighted that, while grown-ups often have more power than children, children have unique and special kinds of power which we think can help make the world a more just place. To continue exploring power together, we pivoted into an activity we called The Power Challenge, which was inspired by Theater of the Oppressed (Boal, 2008; N. Moustafa, personal communication). To set up the activity, we instructed everyone to find the Play Doh we had sent them. Next, we told them to: 1) split the Play Doh into four pieces; 2) make three of the pieces into cubes; 3) make one of the pieces into a ball/sphere; and 3) come up with ways to make the sphere/ball more powerful than the cubes. We gave everyone about 3 min to create with their Play Doh, and then we brought the group back together. The following quotes illustrate how the campers were thinking about power at this point in the process.

Stuffie Lord!!!!!: It’s kind of like a movie. So let us think. Three mean squares be mean to a tiny ball, but the ball goes home and decides to learn how to fight. So a few days later the ball comes back and stands up to the big squares and the – a ball gets a bit more power than the squares.

Basketball star: My way is that there are three squares and one ball, and the ball might be, like, quiet, so the ball does not need somebody else to help it… the ball is unique because it’s not the same as the squares. The ball is unique and it’s different than the squares, so it has power in different ways than the squares, and the ball can break into different pieces, like my ball here can break into different pieces.

Will: I have two ways. So one – the ball goes to college, it just gets smarter than the three balls and knows – and since he knows more than all three balls put together they do not feel as powerful – like the ball is more powerful. And if the ball is bigger than all three squares put together, it could also be more powerful.

As shown in the examples, many of their Play Doh creations connected to how power could be used to harm or to support others. As facilitators, we used this as a way to connect power to the ideas of justice and injustice. We explained: When there is injustice in the world, power is helping that injustice exist. If we want to change things to create justice, we need to use power to do that too.

After the Power Challenge activity, we ended Session 6 by introducing The Power Rainbow, showing it on a slide and talking through each of the levels. We used the example of justice for animals in zoos to illustrate what each level of The Power Rainbow would represent for a specific justice issue (i.e., going from inside to outside: an animal; its caretakers; the zoo it lives in; the rules and laws that regulate animal treatment in that zoo; social beliefs about animals and how humans should treat them).

In presenting The Power Rainbow to campers, it was important to us to highlight why a framework like this one is useful when discussing injustices we see around us. As described previously, we conceptualized The Power Rainbow as a tool for power analysis, which is a fundamental component not only of CPAR but of any critical education, research, or organizing process. In order to explain this thinking to campers who were not familiar with the concept of power analysis, we emphasized that The Power Rainbow allows us to see a bigger picture than the specific instances of injustice we notice around us, which helps us to imagine and eventually take action toward more just futures effectively. We also noted that looking for the big picture helps us move blame away from individuals and toward the forces that shape the actions of those individuals (and in shaping those actions, prevent all of us from building the kind of world we want to live in).

Over the remaining sessions of the camp, The Power Rainbow continued to provide an orienting structure to help our research team think about their chosen research topics. In Session 7, after sharing back with the campers the ideas they had generated about power during Session 6 (see Figure 6), we asked campers to use The Power Rainbow for a power mapping activity. We asked them to draw their own rainbows, and in two breakout rooms (one for campers more interested in animal justice, and one for those more interested in health justice) we presented them with simplified versions of local news stories (Huffman, 2017; McGloin, 2020) about their research topics (see Supplementary material S2). While the breakout groups discussed the stories, the campers labeled their rainbows with the people, organizations, rules, and values mentioned in the stories. After this activity, we shared our screen with a color-coded table based on the levels of The Power Rainbow and had conversations in breakout rooms to generate survey questions corresponding to each level (see the table we created, along with the questions campers generated, in Supplementary material S3).

It is important to note that using The Power Rainbow did not make these sessions “perfect.” When reflecting on Session 7, for example, we noted that while the rainbow color-coded table was useful, other elements of the curriculum could have been tweaked to better support the campers. The session felt more adult-led than we wanted it to; Hania described that she did much of the talking in her breakout room (the health justice room), and we both felt that the news stories we provided shaped the campers’ survey questions more than we had intended. The activity may have been more generative if we had started by inviting campers to reflect on their own experiences, and had incorporated the articles as needed afterward.6 However, while the process of developing survey questions still involved some challenges, we felt that by using the color-coded table based on The Power Rainbow, we were able to help the campers ask questions that addressed issues more structurally than during summer 2020.

In Session 8, we shared with campers the survey we had created using the questions generated in Session 7, and we made a plan to send that survey to people in their lives, including people who they thought might have experience or expertise related to their research topics. In Session 9, we presented the results of the survey, using a slide that sorted qualitative responses by Power Rainbow level (see Supplementary material S4). We asked campers to start working on drawings that show what justice might look like for their research topics based on what we had learned together.

Finally, during Session 10 (our last session of the camp), we asked campers to share their drawings of justice. Then, we pivoted to talk about what it might take to get to those visions of a more just world. Within the constraints of our short, virtual camp, this was as far as the research team would get into the CPAR phase of “taking or planning for social action.” We initially wanted each camper to brainstorm an action for each level of the rainbow, but for the sake of time, each camper ended up focusing on only one level. We also talked about other examples of actions from Boston-area social justice organizations and how they address power at different levels. Even during this abbreviated action phase, The Power Rainbow was a useful framework for highlighting the differences between actions at individual and structural levels.

In summary, one of our primary goals during our 2021 camp was to introduce a methodological tool to support our campers in engaging in power analysis – a key ability for engaging in CPAR and other critical and transformative research approaches. The Power Rainbow accomplished this by providing the campers with a framework for exploring how power operates structurally in the world, and specifically in relation to their chosen research topics. As described in the preceding paragraphs, we utilized the tool within a larger camp curriculum (including activities like the power riddles and play doh activity, which helped to define power as a concept). While these activities to introduce power worked well, we feel that it is The Power Rainbow that provided the key scaffolding that allowed campers to move beyond simply discussing the idea of power and toward engaging in systemic power analysis.

The Bountiful wild

Power analysis is a foundational component of working toward justice, including within transformative research approaches like CPAR. Based on our observations, the 3rd–5th graders in our CPAR camps struggled to shift from an individual or interpersonal perspective on injustice (e.g., people sometimes act unfairly towards one another) toward a more accurate, structural analysis informed by how power operates at different levels of society (e.g., individual unfair actions are influenced by institutions, laws, and cultural norms). To support our CPAR campers through this key component of the CPAR process, we developed The Power Rainbow, a flexible, methodological tool incorporating input from the children we have worked with and our own reflections. When we piloted the tool in a CPAR context, we observed that The Power Rainbow helped us move past the sticking points that we identified in thinking about power structurally with children. Specifically, it helped us – through pre-planning and in the moment – to shift the direction of conversations when campers were focused only interpersonally or only on rules and laws, thereby incorporating opportunities for power analysis into every step of the CPAR process.

Validity (Why should you trust the learnings shared in this paper?)

In sharing our experiences and The Power Rainbow itself, we also want to engage with the concept of validity. The idea of validity helps us figure out whether we should trust research findings – in the case of this paper, whether you should trust that The Power Rainbow is a useful tool for power analysis with elementary school children. Not everyone conceptualizes validity in the same way, and different ideas of validity raise different types of questions about research. For example, many researchers rely on internal validity (how confident can one be that the research findings are attributable to the factors the researchers identify, and not to other variables?) or external validity (to what extent can the research findings be applied to other contexts or populations?)

Critical researchers often draw on additional concepts of validity, which align with the philosophical foundations of CPAR. One of these is Theoretical Generalizability, which asks: Is enough information about the research provided that one can transfer findings appropriately to other contexts? While traditional notions of external validity assume that high-quality research findings should be directly transferable to as many other contexts as possible, theoretical generalizability is grounded in a more qualitative and context-specific perspective on knowledge (Fine, 2006). Fine (2006) describes theoretical generalizability as “the extent to which theoretical notions or dynamics move from one context to another,” and emphasizes that researchers should provide enough nuance and specificity (about the research context, population, and research methods) for the reader to meaningfully consider these dynamics and their transferability. Another form of validity is Provocative generalizability, which combines the idea of transfer with the transformative approach of CPAR, by “provoking” readers to “generalize to ‘worlds not yet’… to rethink and reimagine current arrangements” (Fine, 2006). In other words, did we provide enough context for readers to consider how our research findings might translate into other contexts with elementary school children? Does our research encourage readers to imagine new methods of power analyzes in educational research and practice?

Another form of validity utilized in critical research is Authenticity. CPAR scholarship tells us that research questions and analyzes must be authentic to local contexts. This means that a research project must be: situated (i.e., the context must be clear and well described); participatory (members of the community must be part of the process); and transformative or activist (the purpose and outcome of the research must be both action and knowledge production) (Rodríguez and Brown, 2009).7

In writing this paper, we have tried to hold ourselves and our work to these rigorous notions of validity. In accordance with Fine’s (2006) perspective on theoretical generalizability, we have tried to be as transparent as possible about our own positionality and our process of creating, refining, and using The Power Rainbow. Our hope is that the detail we provide will allow readers to reflect on how The Power Rainbow might be useful in their contexts, as well as provoking readers to imagine new ways of exploring power with children. Further, we present The Power Rainbow as an authentic innovation because it emerged from situated and participatory research within the context of our CPAR camps; it was inspired by, and incorporated, the ideas and questions about power shared by children in those projects; and it was conceptualized and used not only to increase understanding, but to facilitate action. As we aim to make clear in this paper, The Power Rainbow was successful in its original context in moving our research team toward a more critical and power-oriented research process.

Limitations (What are the shortcomings of the learnings we are sharing here?)

While we try to be as intentional as possible in the decisions we make, we are constantly navigating the constraints of time-bounded, virtual programming. We remind ourselves that we cannot do everything and acknowledge that we sometimes get things wrong. In this section, we address some of the limitations of The Power Rainbow and our use of it.

While we do not think a “perfect” version of any pedagogical tool exists, we know there are ways the current iteration of The Power Rainbow could be improved. The Power Rainbow is not accessible for learners who are visually impaired, including those who are colorblind. The levels of the rainbow, and the labels for those levels, do not encompass all of the types of power that operate in our society. We devised the levels and labels to be a child-friendly (and graphic friendly – i.e., the labels could not be too long) starting place for power analysis. We do not know that our current levels and labels are the best ones, and we expect them to continue changing. As children become more comfortable with The Power Rainbow, it would be necessary to open up additional conversations. For example, what counts as an institution or organization? How are rules and laws different? What other structures might exist in-between the levels of the rainbow or might straddle multiple levels? Additionally, The Power Rainbow as it currently exists requires some explanation and facilitation. Supplemental resources would likely be needed to help parents or educators use the tool without significant planning, or to help children use the tool on their own.

As a power analysis tool, The Power Rainbow necessarily draws our attention to the realities of the world we live in. However, we believe it is important to combine analysis of existing power structures with exercises in imagining new ways to use power more justly in the future. Given this, we try to use power analysis tools like The Power Rainbow alongside art-based, play-based, and imaginative activities, and to highlight the connections between understanding current injustices and envisioning more just futures. Children are radically imaginative and able to think beyond adult-created structures and frameworks. We know they will continue to help us dream up new ways to use The Power Rainbow and push the limits of our personal and societal imaginations.

Future directions (How can we imagine others building on what we share here?)

While The Power Rainbow started as a methodology for a specific purpose and in a specific research context, we can imagine it being used in a variety of other ways in the future – both within and beyond CPAR projects.

For example, The Power Rainbow could be brought into classrooms and used as a framework to explore the roles power plays in a variety of different academic subjects. The levels of the rainbow could provide the structure for a worksheet or activity book for kids or families to use at home. The rainbow could even be reproduced in 3-dimensions, providing opportunities to merge power analysis with movement- or play-based education. We would love to see educators (potentially natural science educators) lean into the metaphorical possibilities behind The Power Rainbow. As one example: white light (like the light from the sun) is a mixture of all of the colors, but usually we cannot perceive those individual component colors in it. In a rainbow, they are temporarily made visible. In the same way, the practice of critical reflection can make previously invisible structures of power visible to us.

We have even found The Power Rainbow to be useful outside of middle childhood or interactions including children. We find ourselves thinking of it often in our adult lives, when we encounter instances of injustice or examples of social activism. We find ourselves asking, which levels of The Power Rainbow are at play here? Or, how can I expand my thinking (or my action) at this moment to encompass additional levels? Like the children we have worked with, we sometimes have to remind ourselves to shift our focus away from an individual perpetuating injustice and toward the institutions, laws, and values that enshrine or encourage such individual actions.

We trust that you (as well as any students, children, family members, friends, and colleagues you may share The Power Rainbow with) will have many creative ideas. We encourage you to use The Power Rainbow in your own contexts and adapt it as needed for use in your own classrooms or other educational spaces. If you share The Power Rainbow, please cite or reference this paper or the original tool (Kirby and Mariën, 2023). If you want to create adapted or remixed versions of the tool to share outside of your educational spaces (e.g., on social media, in newsletters, or in trainings), please contact the authors. We also ask that your use of The Power Rainbow honors the spirit in which it was created, as a tool to help us imagine and work towards more just futures.

The paper is focused on presenting The Power Rainbow as a methodological tool, as well as describing how it helped us open up space for power analysis with children in the context of CPAR. Given that focus, we did not systematically evaluate children’s ability to engage in power analysis before and after using the tool. However, existing research has used ethnographic field notes and qualitative coding to understand the impact of pedagogical tools on kids’ reasoning about causes of injustice (Kohfeldt et al., 2011) and future research could develop and pilot new methods for evaluating children’s power analysis specifically. We encourage researchers to think about how this work could happen within critical research paradigms, guided by the forms of validity described above.

Finally, while we believe The Power Rainbow is a useful contribution, we know that other exciting work is being done in this area and that much more work is needed. Children learn in different ways, so when there are more options of resources and tools available to the adults who care for and work with children, it is more likely that one of those resources will be supportive. We encourage you to consider this paper not only as an invitation to use The Power Rainbow, but also as inspiration to find other ways to support children in understanding and analyzing power within critical research and educational spaces.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of abundant caution in protecting the identities of child participants, even in de-identified, qualitative data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to annakirby@g.harvard.edu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Harvard University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

HM and AK participated equally in data collection, analysis, and the writing of this paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1185685/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1 | Power Rainbow coloring page.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S2 | News stories about campers’ research topics.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S3 | Survey questions sorted by Power Rainbow levels.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S4 | Results of survey sorted by Power Rainbow levels.

Footnotes

1. ^A, Artista Named E, Basketball Star, Chemie Forscherine, Creative S, Davi, Glider, Horsegirl, Lizard Researcher, Puppy Ninja, Queen G, Rainbow, Smol beans/Yoshiboy, Squash Player, Stuffie Lord!!!!!!!!!!!!!, Swimmer, Will and Wingwatcher.

2. ^Although we work with children, we use the term CPAR rather than YPAR (Youth Participatory Action Research) in order to highlight the critical nature of the research process (i.e., its engagement with power and its transformative aims). When we reference existing literature, we use the terms employed by the researchers.

3. ^We wrote these section headings with academic accessibility in mind. We chose to publish in Frontiers specifically because it is an open-access journal, but we know that making research accessible means more than removing financial barriers – it also means writing in a way that is clear for readers from non-academic backgrounds. While terms like “literature review” and “positionality” are useful signals for many readers, we felt that including translations of these terms in the form of questions increased inclusivity for a wider audience.

4. ^Throughout the paper, we (the authors, Hania and Anna) use the word “we” to refer to the two of us. We use the phrase “the CPAR research team” to refer to ourselves plus the 3rd–5th graders in either of our CPAR summer camps. We refer to the 3rd–5th graders alone as “the CPAR campers.”

5. ^While we now see the rainbow shape as central to the tool, it was initially chosen for logistical reasons. Our first draft consisted of colorful circles, until Hania suggested “chopping off the bottoms” to make it fit better on our slides. The practicality of our thinking still makes us laugh. We embraced the rainbow shape and appreciate its connection to the water cycle (CPAR is also a cycle) and the associations between rainbows and moments of clarity or hope.

6. ^While this observation is not directly related to the usefulness of The Power Rainbow itself, we feel it is important to note that the tool can be used in ways that are more or less effective, and that it is not our intention that it be used in ways that reinforce adult power within educator-child interactions. This is an example of a time when, in retrospect, we would have liked to step back as educators and allow the campers to exercise power in shaping the conversation.

7. ^The idea of research as transformative or activist is also sometimes referred to as Impact Validity (Massey and Barreras, 2013; Sandwick et al., 2018).

References

Anselma, M., Chinapaw, M., and Altenburg, T. (2020). “Not only adults can make good decisions, we as children can do that as well” evaluating the process of the youth-led participatory action research children in action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:625. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020625

Ayala, J., Cammarota, J., Berta-Ávila, M., Rivera, M., Rodríguez, L., and Torre, M. (2018). PAR EntreMundos:A pedagogy of the Américas. Peter Lang Publishing. New York City.

Bohman, J. (2016). “Critical theory” in The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. ed. E. N. Zalta Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-theory/

Brion-Meisels, G., and Alter, Z. (2018). The quandary of youth participatory action research in school settings: a framework for reflecting on the factors that influence purpose and process. Harv. Educ. Rev. 88, 429–454. doi: 10.17763/1943-5045-88.4.429

Brion-Meisels, G., Fei, J. T., and Vasudevan, D. S. (Eds.). (2020). At our best: Building youth-adult partnerships in out-of-school time settings. IAP. Rotterdam.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979).The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cammarota, J., and Fine, M. (Eds.). (2010). Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. Routledge, England.

COCo (2018). The Oppression Tree Tool. Available at: https://coco-net.org/the-oppression-tree-tool/#:~:text=When%20we%20use%20this%20as,and%20supported%20by%20the%20facilitator

Fine, M. (2006). Bearing witness: methods for researching oppression and resistance—a textbook for critical research. Soc. Justice Res 19, 83–108. doi: 10.1007/s11211-006-0001-0

Fine, M., and Torre, M. E. (2021). Essentials of critical participatory action research. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Grusec, J. E., Chaparro, M. P., Johnston, M., and Sherman, A. (2012). “Social development and social relationships in middle childhood” in Handbook of Psychology. ed. I. B. Weiner. 2nd ed (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc), 6.

Huffman, Z. (2017). Group Fights to Retire Massachusetts Zoo’s Elephants. Courthouse News Service. Available at: https://www.courthousenews.com/group-fights-retire-massachusetts-zoos-elephants/

Kohfeldt, D., Chhun, L., Grace, S., and Langhout, R. D. (2011). Youth empowerment in context:exploring tensions in school-based yPAR. Am. J. Community Psychol. 47, 28–45. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9376-z

Kohfeldt, D., and Langhout, R. D. (2012). The five whys method: a tool for developing problem definitions in collaboration with children. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 22, 316–329. doi: 10.1002/casp.1114

Langhout, R. D., Collins, C., and Ellison, E. R. (2014). Examining relational empowerment for elementary school students in a yPAR program. Am. J. Community Psychol. 53, 369–381. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9617-z

Massey, S. G., and Barreras, R. E. (2013). Introducing “impact validity”. J. Soc. Issues 69, 615–632. doi: 10.1111/josi.12032

Mariën, H. K. (2022). Imagining more just futures: A creative study of a YPAR process with 3rd-5th grade children. [Unpublished manuscript]. Graduate School of Education, Harvard University.

McGloin, C. (2020). Despite The Pandemic, Immigrants In Mass. Say They Are Afraid To Seek Medical Care. WGBH News. Available at: https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2020-06-15/despite-the-pandemic-immigrants-in-mass-say-they-are-afraid-to-seek-medical-care

McLaren, P., and Kincheloe, J. L. (Eds.). (2007). Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? (Vol. 299). PeterLang. Oxford.

Mirra, N., Garcia, A., and Morrell, E. (2016). Doing youth participatory action research: A methodological handbook for researchers, educators, and students. Routledge. London

Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., and Rose, T. (2020). Drivers of human development:how relationships and context shape learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24, 6–36. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650

Pinnegar, S., and Hamilton, M. L. (2009). Self-study of practice as a genre of qualitative research: Theory, methodology, and practice. 8, Springer Science & Business Media.

Rodríguez, L., and Brown, T. M. (2009). From voice to agency: guiding principles for participatory action research with youth. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2009, 19–34. doi: 10.1002/yd.312

Sandwick, T., Fine, M., Greene, A. C., Stoudt, B. G., Torre, M. E., and Patel, L. (2018). Promise and provocation: humble reflections on critical participatory action research for social policy. Urban Educ. 53, 473–502. doi: 10.1177/0042085918763513

Saunders, C., Buckthorn, G., Salami, M., Scarlet, M., Songhurst, H., Avelino, J., et al. (2019). The power book: What is it, who has it, and why? Ivy Kids: London.

Torre, M. (2009). Critical participatory action research map. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1mcX3OR0nfif6pRx1eMXRfnqv2xoRV3PJ/view?pli=1

Keywords: critical pedagogy, power analysis, middle childhood, social justice education, CPAR

Citation: Mariën HK and Kirby AL (2023) The Power Rainbow: a tool to support 3rd–5th graders in analyzing systems of power. Front. Educ. 8:1185685. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1185685

Edited by:

Isabel Menezes, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

I-Chien Chen, Michigan State University, United StatesStacy DeZutter, Miller College, United States

Copyright © 2023 Mariën and Kirby. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna L. Kirby, annakirby@g.harvard.edu; Hania K. Mariën, hmarien@g.harvard.edu

†These authors share first authorship

Hania K. Mariën

Hania K. Mariën