- CRC-W - Católica Research Centre for Psychological, Family and Social Wellbeing, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal

Introduction: Service-Learning (SL) is an innovative teaching-learning proposal with an increasingly wide application in higher education. Previous studies show its potential to generate positive personal, academic, social and citizenship outcomes among students who participate in it. But studies that help understand in depth its real impact, particularly in comparison with more traditional teaching-learning contexts, are still scarce.

Method: This study explores the effects of Service-Learning on 122 university students, who were attending Psychology (n = 80), Social Work (SW; n = 19) and Applied Foreign Languages (AFL; n = 23) degree courses. These participants were organized into service-learning and traditional teaching-learning groups and assessed on expectations and impact of the service-experience, development of social and civic skills, and life goals.

Results: Results show significant differences between pre- and post-tests in life goals, namely an increase in hedonistic and wellbeing goals for Psychology students, political, hedonistic, religious, personal development, and wellbeing goals for SW students, and social and wellbeing goals for AFL students. Students in Psychology and AFL increased their expectations with the service and students in the AFL developed more pro-social behaviors.

Discussion: These results are encouraging for the expansion of this transformative teaching-learning practice to courses of different scientific areas, although with some specificities, with the purpose of contributing to a more responsible, critical and participatory society in the creation of the common good.

Introduction

Service-Learning (SL) is an experiential teaching-learning methodology that combines academic learning with community service (Celio et al., 2011) with the goal of enhancing learning, teaching civic responsibility, and strengthening communities (Fiske, 2001).

Previous studies, including very recent findings, have highlighted its relationship with several benefits for the participating students, including gains in these key domains (Celio et al., 2011; Salam et al., 2019; Folgueiras et al., 2020; Lin and Shek, 2021; McDougle and Li, 2023): attitudes toward self, school and learning, civic engagement, social skills such as teamwork and adaptation to new situations, academic performance, and life satisfaction. The SL experience seems to be associated with positive emotions such as interest, enthusiasm, inspiration, and determination, which are maintained throughout the experience (Opazo et al., 2018). Other authors also highlight SL as a significant experience impacting participants’ life goals by focusing on contributing to “the common good” (Opazo et al., 2018).

In addition to the students, who can benefit personally, socially, and academically, the SL programs have also shown (e.g., White, 2001; Conway et al., 2009) a positive influence on the community receiving the services and on the educational institution hosting the program. The use of this methodology is meaningful in a context where, particularly in the last two decades, there has been a growing emphasis on the transformation of higher education in Europe, with the promotion of an active and democratic citizenship through formal higher education being a primary concern (Ribeiro et al., 2021). SL has proven to be a powerful didactic methodology to achieve these ideals, becoming a widespread strategy in schools around the world, with an exponencial growth of contributions over the last 20 years (Queiruga-Dios et al., 2021; Sotelino-Losada et al., 2021) as opposed to more traditional teaching-learning models (e.g., Opazo et al., 2018; Prado et al., 2020).

SL is based on the theoretical proposal of Dewey (1938), an American educator and philosopher who strongly influenced movements for the renewal of education in various parts of the world. His theory (“learning by doing”) proposes that individuals reflect on and use prior knowledge from personal experiences to achieve authentic learning, leading to new ways of seeing education as an active connection between knowledge and experience through engagement and reflection on the world beyond the classroom. It proposes to increase students’ understanding of the content learned and, at the same time, to promote the fulfilment of community needs (Salam et al., 2019), since – in Dewey’s conception - the world constitutes an ever-changing reality, and it is only through action that it is possible to know it. It is therefore up to educational institutions to provide this action, suppressing the obstacles of the community as much as possible.

Thus, through SL, students find very specific opportunities to apply their knowledge and skills in projects developed outside the university setting that aim to benefit the community or a certain group of people with a specific need (Waldner et al., 2012). This experiential learning, potentially beneficial for all stakeholders (Henry and Breyfogle, 2006; Tijsma et al., 2020), allows students to apply theoretical knowledge in a “real world” context, enhancing their understanding about theoretical concepts and promoting multiple skills and personal growth (Salam et al., 2019). In a very recent study, Lin et al. (2023) highlight the potential benefits of the SL experience even if conducted online (e.g., life satisfaction and leadership skills) and suggest the perceived benefits may vary for students depending on their psychosocial skills and learning experiences.

Following the first studies in our country (Veiga et al., 2021; Pais et al., 2022) seeking to understand the effect of the practice of SL experiences in Higher Education in Portugal, the present research aims to explore the effects of the use of this pedagogical model on students from a Portuguese university attending three different courses (Psychology, Social Work and Applied Foreign Languages) in the 2021–2022 academic year and organized into an experimental group (with SL experience) and a control group (without SL experience). Students were assessed at the beginning (February) and end (May) of the semester (pre-and post-test) on the following dimensions: expectations toward service-learning, perceived impact of the experience, development of civic and social skills, and life goals.

Research goals and hypotheses

The present study aims to evaluate the impact of the SL experience in three distinct courses, as opposed to tractional teaching-learning contexts. To achieve this goal, the following research hypotheses were developed:

H1: In each course, participants in both groups (experimental and control) show no differences at pre-test on the subscales regarding expectations and impact of the service-learning experience vs learning in course units, civic and social skills, and life goals.

H2: In each course, participants in both groups (experimental and control) show significant differences at post-test on the subscales regarding expectations and impact of the service-learning experience vs learning in course units, civic and social skills, and life goals. These differences are favorable to the experimental group.

H3: In each course, there are no significant differences from pre-to post-test in the control group on the subscales regarding expectations and impact of the service-learning vs learning experience in course units, civic and social skills, and life goals.

H4: In each course, there are significant differences from pre-to post-test in the experimental group on the subscales regarding expectations and impact of the service-learning vs learning experience in course units, civic and social skills, and life goals, with higher results at post-test.

H5: There are no significant differences between the three courses in the experimental group (SL) in the pre-test on the subscales related to expectations and impact of the service-learning vs learning experience in course units, civic and social skills, and life goals.

H6: There are no significant differences among the three courses in the experimental group (SL) in the post-test on the subscales in the variables related to expectations and impact of the service-learning vs. learning experience in course units, civic and social competencies, and life goals.

Methods

Participants

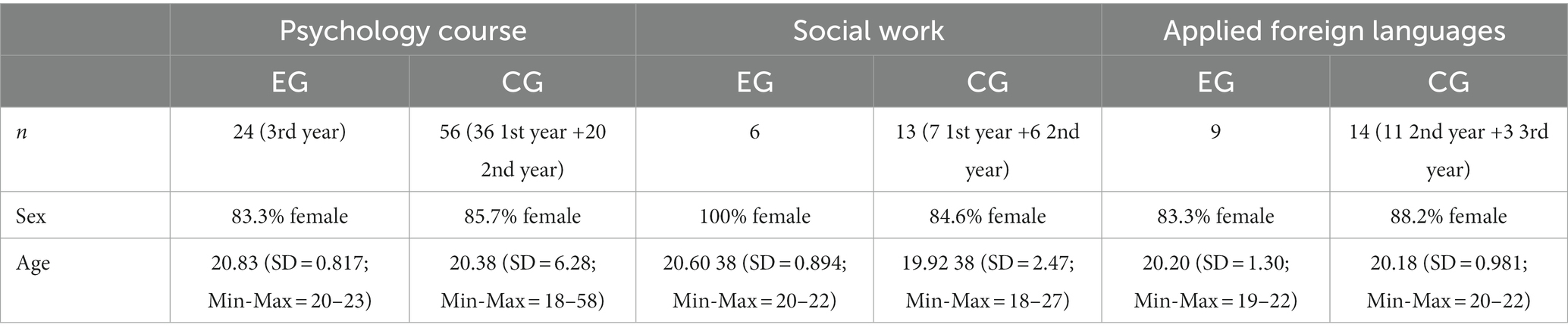

A total of 122 undergraduate students from the Faculty of Human Sciences at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa (UCP; Lisbon campus), enrolled in the academic year 2021/2022, participated in this study. These students were attending the Psychology degree in the 1st (n = 36), 2nd (n = 20) or 3rd (n = 24) year of the course, the Social Work degree in the 1st (n = 7), 2nd (n = 6) or 3rd (n = 6) year, and the Applied Foreign Languages (ALE) degree in the 1st (n = 9), 2nd (n = 11) or 3rd (n = 3) year. In the control groups (CG) there was no previous contact of the students with the SL methodology. The experimental groups (EG) were attending for the first time a course unit using the SL methodology. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the students comprising both the experimental and control groups per course.

Instruments

The research protocol consisted of a total of 4 separate sections:

i. Expectations regarding the learning-service experience: ten items, with a 5-point Likert response scale (1 = Strongly Disagree and 5 = Strongly Agree), that aim to assess the impact of the learning-service experience (or of the course units of that semester, in the case of the control group) on a set of knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes (e.g., Be more responsible for my learning). Exploratory factor analyses indicate that the items are grouped into two subscales: learning-related expectations and service-related expectations which explain 39% of the total variance. The assessment of internal consistency indicated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.71 for learning-related expectations and 0.86 for service-related expectations.

ii. Impact of the learning-service experience: ten items, with a 5-point Likert response scale, which intend to evaluate the perception of the impact that the learning-service experience had on oneself (student) and on others (e.g., The service has contributed to better understand the contents of the curricular unit) - completed only by the experimental groups at the post-test. The exploratory factor analysis indicated the existence of a single factor, which explains 48% of the total variance. The assessment of internal consistency indicated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

iii. Civic and social skills: twenty items (CUCOCSA; Santos-Rego et al., 2021), with a 6-point Likert response scale (1 = Strongly disagree and 6 = Strongly agree), which aim to assess the extent to which the student considers having a set of competences (e.g., I am able to work cooperatively with other people). In the original version of the instrument the items are organized into four subscales that explain a variance of 50.96%: pro-social behavior (α = 0.79), teamwork and relationships with others (α = 0.70), intercultural competence (α = 0.73), and leadership (α = 0.72).

iv. Life goals: thirty-three items (Major Life Goals; Roberts and Robins, 2000), with a 5-point Likert response scale (1 = Not at all important and 5 = Totally important), which intend to assess to what extent a set of goals are valued by the student (e.g., Make my parents proud). The exploratory factor analysis performed at this sample indicated the existence of nine factors, which explain 54.75% of the total variance with alpha reliabilities ranging from 0.68 to 0.84: economic, aesthetic, social, relationship, political, hedonistic, religious, personal development, and wellbeing.

Data collection procedure

The decision to include the Psychology, Social Work, and Applied Foreign Languages courses was based on the implementation of a phased and voluntary teaching methodology across multiple campuses, schools, study cycles, and courses at UCP. In the 2021/22 academic year, the only bachelor’s degree in the Faculty of Human Sciences that did not incorporate this methodology was Social Communication. Therefore, we strongly believe that by including three distinct courses from diverse scientific fields (humanities, social services, and behavioral sciences), we can enrich the discussion on the impact of service-learning.

Students in the experimental groups were attending curricular units in the 2nd semester of the 2021/22 school year using the SL methodology, through which had the opportunity to learn and deepen some of the planned programmatic contents, while applying them by providing a service to the community.

In the Psychology course, the curricular unit was Educational Psychology, in which there was collaboration with a private organization that aims to achieve social action, health care, education and culture objectives, as well as the promotion of quality of life, particularly for people in situations of social and professional vulnerability. Students were integrated in the project “Boost me up!: Promoting and supporting engagement, learning and wellbeing,” which consisted of preparing workshops on topics such as self-knowledge, exploring the world, developing social and emotional skills, and promoting wellbeing among the institution’s users. The target-group was composed by students of alphabetisation, hairdressing, and elderly support courses. The university students were organized into six distinct groups, with each group being responsible for developing a workshop on one of the topics. Each workshop lasted 1 h and included a brief presentation followed by a set of dynamics/activities appropriate to the target-group. Two groups of students were also responsible for the organization of a visit to the university.

In the Social Work (SW), the project was developed in the course unit of Social Work and Social Administration. The main objectives included making a participatory organizational diagnosis and designing a strategic plan for sustainability, choosing a single axis of affirmative and participatory action, as a collaborative work between students and associative leaders/responsible of the services chosen as partners. The class was divided into four working groups corresponding to each SL partner organization. The four NGOs selected were: (i) day care center with activities for adult people with physical or mental disabilities, whose focus of strategic intervention consisted in identifying partnerships for inclusion from the measure of socially useful activities; finding local companies and services to integrate these people in useful activities for their respective users; (ii) residential response institution as a measure of institutionalization for children and youth removed from their families, whose focus was to identify strategic partnerships for funding and sustainability of a day care project that can integrate children from the entire community including those flagged by the Court for the Protection of Children and Youth; (iii) senior academy - educational and socio-occupational forum for elderly men and women, in which students worked to enhance the knowledge of the elderly and intergenerational coexistence as a way to strengthen social ties between generations; and, (iv) socio-occupational forum for adults, men and women with mental illness, whose main action focused on analysing how art workshops can be shared with other groups in the community, bringing together people from inside and outside the institution.

In the Applied Foreign Languages (AFL), the Translation for Equality and Inclusion project was developed within the scope of the Generalist English Translation, a 1st year course. The partner was an association that aims at promoting equality of speech and inclusion practices. The intervention of the “translators” (students) would represent an added value for the dissemination of the association’s work across borders, spreading the support to the foreign community living in Portugal. The methodology consisted in dividing the students into teams, as if they were a translation agency. A project guide was made available to the students, with the designation of the teams and the division of tasks. Translation deadlines (English-Portuguese and Portuguese-English) and final revision were defined by each team. It would be the Team Leaders’ responsibility to deliver the final work to the professor. This work was essentially collaborative and took place outside the classroom and outside class time, providing students with a more practical context and approach close to their future professional reality.

Students in the control groups were attending course units scheduled for the 2nd semester of the 2021/22 school year, and none of them were using the SL methodology. Participants of all groups completed the pre-and post-test questionnaires in a classroom setting, in the presence of the researchers. The average completion time was 20 ± 15 min.

Data analyses procedure

Data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23 for Windows) and Jamovi (version 2.3.18 for Windows). Descriptive statistical analyses which included measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion were performed. Additionally, inferential statistical analyses were conducted to examine differences between groups and evaluation times. U Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare the experimental and control groups of each course, while Wilcoxon tests were employed to analyze the pre-test and post-test variances. Kruskal-Wallis was used to analyze differences between the experimental and the control groups of all courses. The effect sizes of all the statistical analyses were also calculated, non-parametric tests were chosen due to the limited number of participants in the various groups. Statistical significance was determined by a value of p of less than 0.05.

Results

Expectations of the service-learning experience

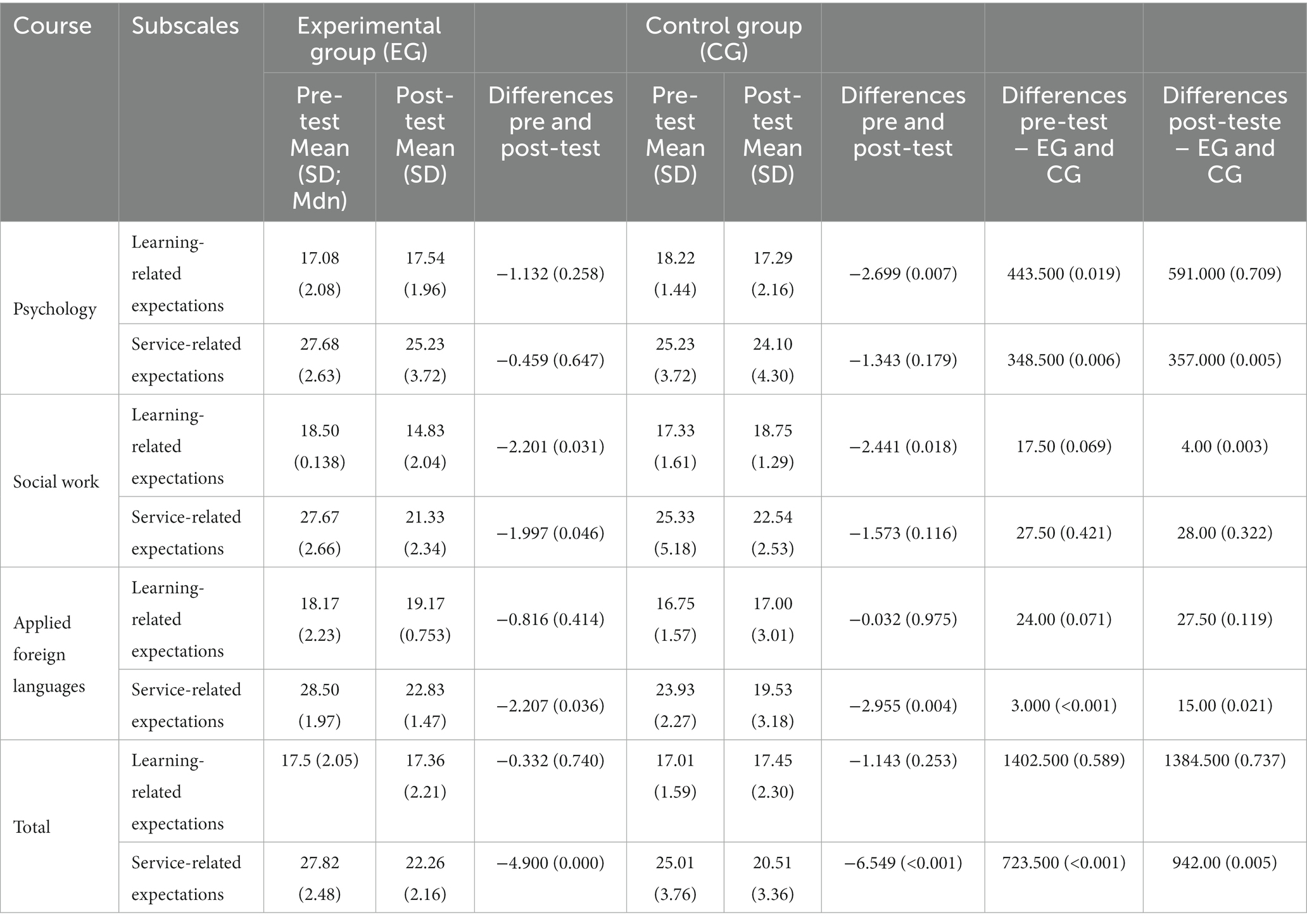

Regarding the Psychology course, results indicate there were no differences between pre-and post-test in both subscales for the experimental group. In the control group, there were differences between the two assessment moments in the Learning-related expectations, with a decrease in the results at post-test (Z = -2.699, p = 0.007; r = 0.495). In terms of comparison between the experimental and control groups, differences were found at pre-test, in the Learning-related expectations (U = 443.500, p = 0.019, r = 0.328) in favor of the control group, and in the Service-related expectations in favor of the experimental group (U = 348.500, p = 0.006, r = 0.402). Also at post-test, there were differences between groups in the Service-related expectations in favor of the experimental group (U = 357.000, p = 0.005, r = 0.403).

Regarding the Social Work course, in the experimental group, differences were found, in both variables, toward a decrease at post-test (Z = -2.201, p = 0.031, r = 1.00; Z = -1.997, p = 0.046, r = 0.905). In the control group, there were differences between the two assessment moments in the Learning-related expectations, with an increase at post-test (Z = -2.441, p = 0.018, r = 0.944). There were also differences between the experimental and control groups at post-test, in the Learning-related expectations (U = 4.00, p = 0.003, r = 0.889) in favor of the control group.

As for the Applied Foreign Languages course, in the experimental group, differences were found in the Service-related expectations, toward a decrease at post-test (Z = -2.207, p = 0.036; r = 1.00). In the control group, there were differences between the two moments in the Service-related expectations, representing a decrease at post-test (Z = -2.955, p = 0.004; r = 1.00). Differences between the experimental and control groups were registered both at pre-test (U = 3.00, p < 0.001, r = 0.929) and post-test (U = 15.00, p = 0.021, r = 0.667), but only in the variable Service-related expectations, and in favor of the experimental group (Table 2).

The comparison between the results of the three experimental groups (Psychology, Social Work, and Applied Foreign Languages) indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between groups at pre-test, either in the Learning-related expectations or Service-related expectations. There were statistically significant differences in the Learning-related expectations [X2 (2) = 11.068, p = 0.004, ɛ2 = 0.316] between Psychology and AFL and between SW and AFL at post-test, with worse results for AFL; but not in the Service-related Expectations.

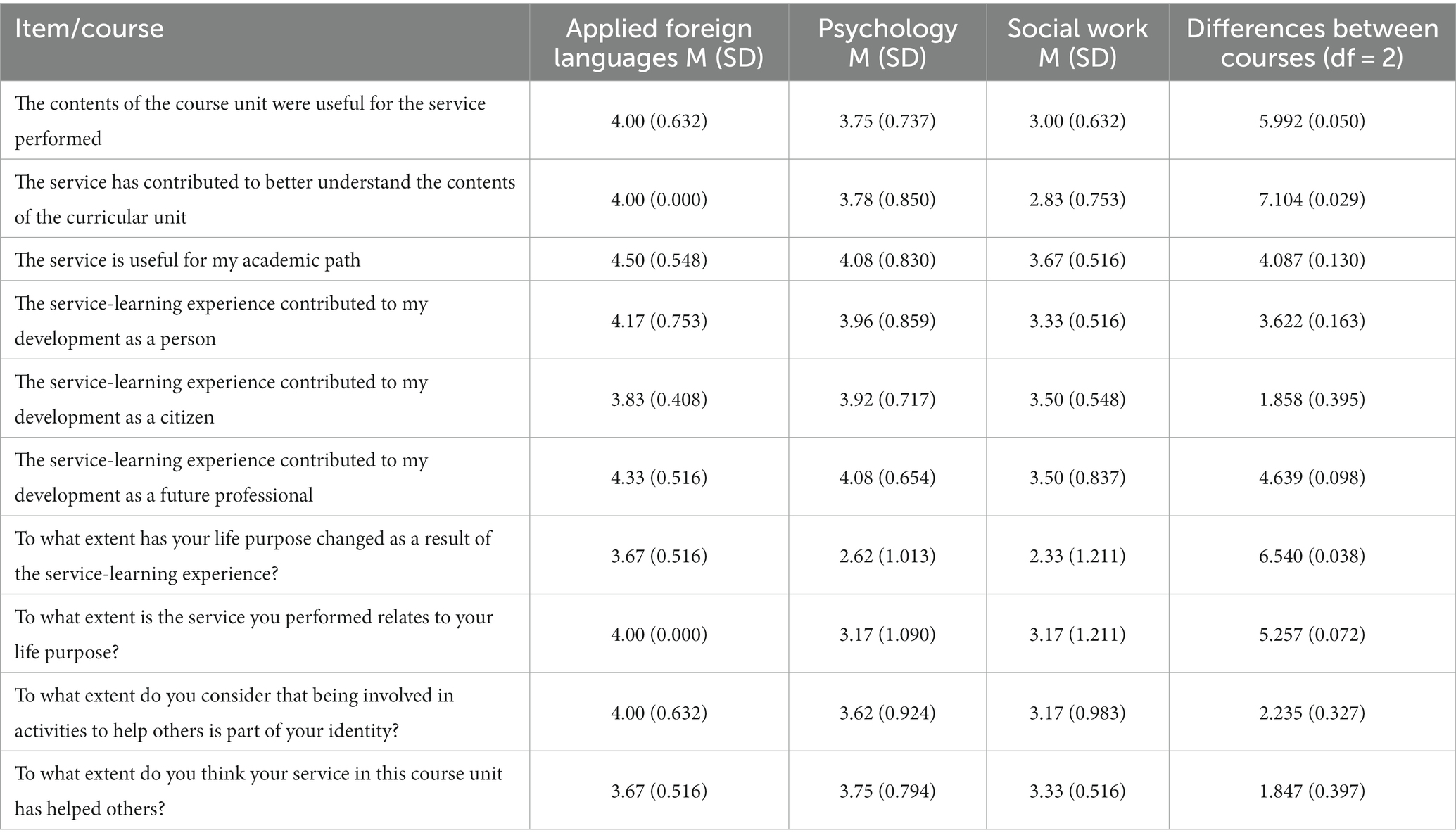

Impact of the service-learning experience

The comparison between the results of the three experimental groups (Psychology, Social Work, and Applied Foreign Languages) indicated statistically significant differences between courses. Specifically, differences were found at: the service performed contributed to better understand the contents of the curricular unit [X2 (2) = 7.104, p = 0.029, ɛ2 = 0.209] between Psychology and Social Work and between Languages and Social Work, and To what extent did your life purpose change as a result of the Service-Learning experience? [X2 (2) = 6.540, p = 0.038, ɛ2 = 0.187] between Languages and Social Work, with results always more favorable for the AFL course (Table 3).

Civic and social skills

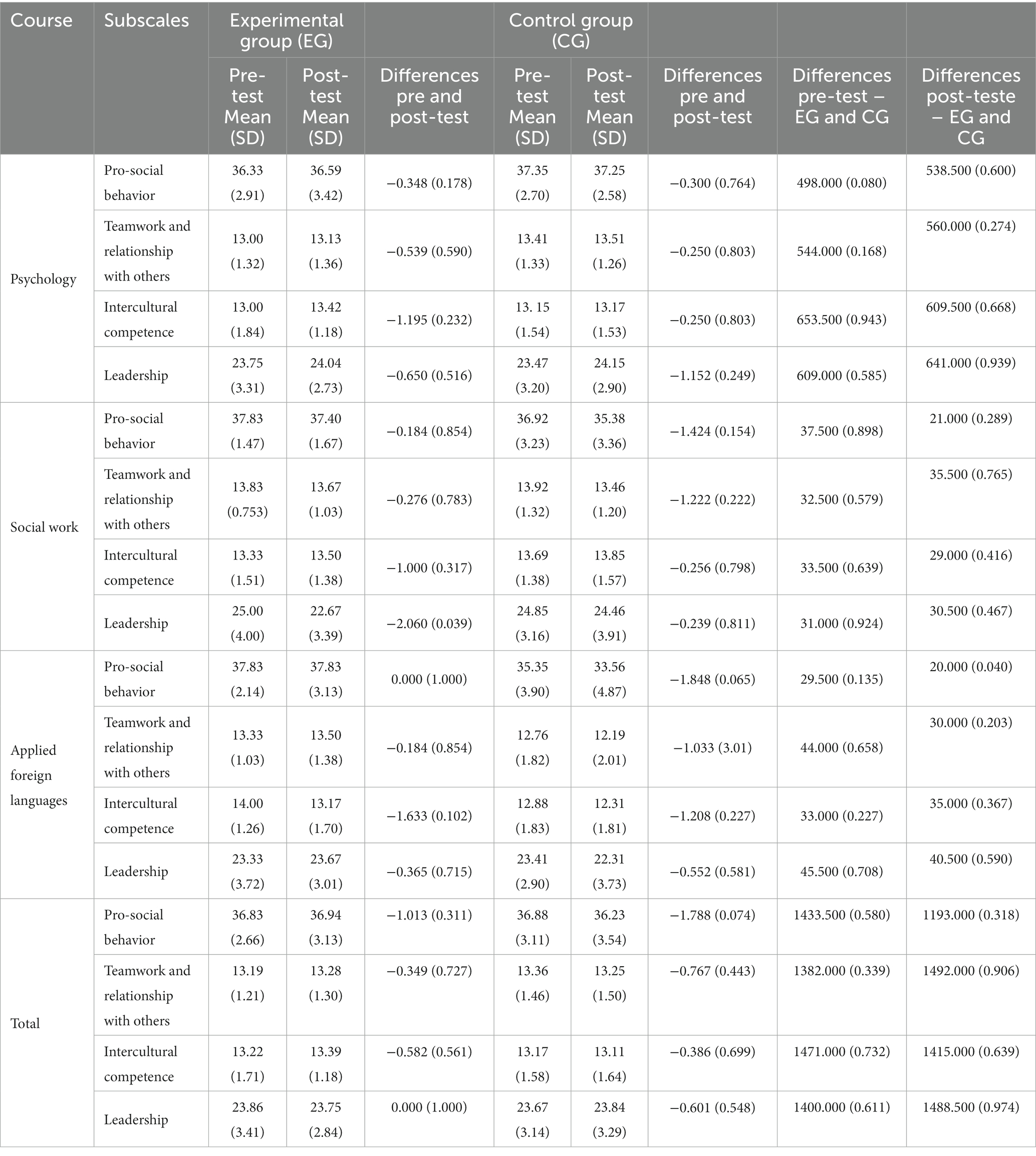

Regarding the Psychology course, no statistically significant differences were found relating to civic and social skills, both in intra and inter-group comparisons.

As for the Social Work course, there was a statistically significant difference in the Leadership subscale in the experimental group, with a decrease in the results at post-test (Z = -2.060, p = 0.039; r = 0.100).

And finally, in the Applied Foreign Languages course, there was a statistically significant difference in the post-test between the experimental group and the control group in the subscale Pro-Social Behavior (U = 20.000, p = 0.040, r = 1.00), in favor of the experimental group (Table 4).

The comparison between the results of the three experimental groups (Psychology, Social Work, and Applied Foreign Languages) indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between them in social and civic skills, considering both the pre-and the post-test.

Life goals

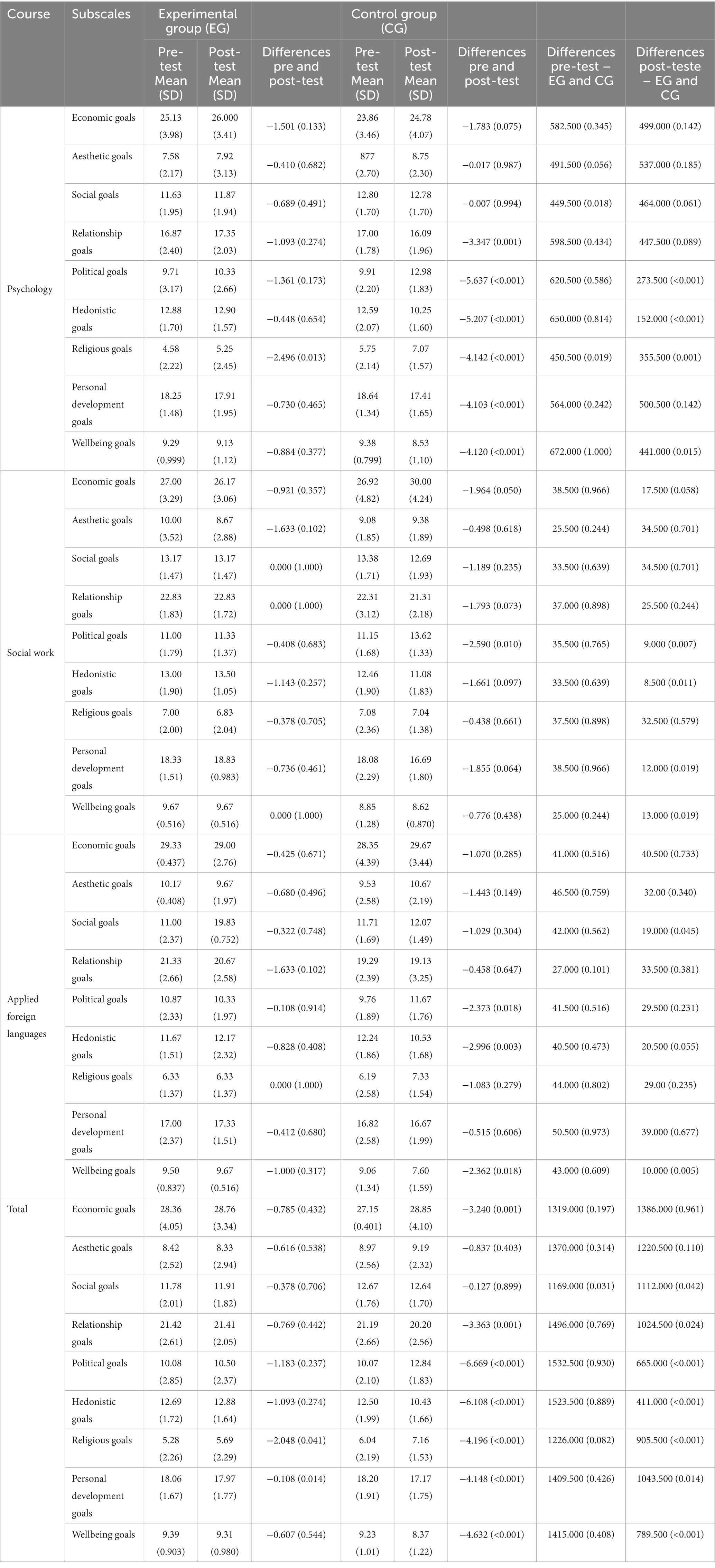

Regarding the Psychology course, the experimental group showed statistically significant differences between pre-and post-tests in the religious goals, toward an increase (Z = -2.496, p = 0.013; r = 0.660). In the control group, there were differences between the two assessment moments in six of the nine subscales (relationship, political, religious, personal development, and wellbeing goals). The differences in the relationship (Z = -3.347, p = 0.001, r = 0.497), hedonistic (Z = -5.207, p < 0.001; r = 0.818), personal development (Z = -4.103, p < 0.001; r = 0.720), and wellbeing goals (Z = -4.120, p<. 001; r = 0.772) were toward a decrease, while the differences in political goals (Z = -5.637, p < 0.001, r = 0.922), and religious goals (Z = -4.103, p < 0.001, r = 0.667) were toward an increase. As for the differences between groups, in the pre-test there were two differences in favor of the control group, in social goals (U = 449.500, p = 0.018, r = 0.331) and religious goals (U = 450.500, p = 0.019, r = 0.330). At post-test there were differences on four subscales, two in favor of the control group - political goals (U = 273.500, p < 0.001, r = 0.586) and religious goals (U = 355.500, p = 0.001, r = 0.461) and two in favor of the experimental group - hedonistic goals (U = 152.000, p < 0.001, r = 0.749) and wellbeing goals (U = 441.000, p = 0.015, r = 0.332).

The Social Work course showed no statistically significant differences between pre-and post-tests in the experimental group. It does, however, revealed statistically significant differences in the political goals (Z = -2.590, p = 0.10, r = 0.879) of the control group, with an increase at post-test. As for differences between groups, these were verified at post-test in political (U = 9.000, p = 0.008, r = 0.769), hedonistic (U = 8.500, p = 0.011, r = 0.764), personal development (U = 12.000, p = 0.019, r = 0.692) and wellbeing goals (U = 13.000, p = 0.019, r = 0.667), always in favor of the experimental group.

Finally, the Applied Foreign Languages course showed no statistically significant differences between pre-and post-test in the experimental group. It does, however, indicated statistically significant differences in political (Z = -2.373, p = 0.018, r = 0.714), hedonistic (Z = -2.996, p = 0.003; r = 0.934) and wellbeing goals (Z = -2.362, p = 0.018; r = 0.736), in the control group, with only the former increasing at post-test. As for the differences between groups, there are no differences at pre-test, and statistically significant differences at post-test were found only in social goals (U = 19.00, p = 0.045, r = 0.578), in favor of the control group (Table 5).

The comparison between the results of the three experimental groups (Psychology, Social Work, and Applied Foreign Languages) indicated the existence of statistically significant differences between courses in aesthetic [X2 (2) = 9.276, p = 0.010, ɛ2 = 0.265] between the AFL and Psychology groups and religious goals [X2 (2) = 8.146, p = 0.017, ɛ2 = 0.233] between the AFL and Psychology; Social Work and Psychology groups at pre-test. At post-test, there were only differences between courses in social goals [X2 (2) = 5.992, p = 0.050, ɛ2 = 0.176] between AFL and Social Work.

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of using the Experiential Service-Learning (SL) pedagogical model versus traditional teaching-learning on students from a Portuguese university, attending three different courses.

As relevant results we highlight the increase in the service-related expectations of the Psychology students who participated in the SL experience, but not for the other two courses, which is partially in line with the conclusions of previous studies (e.g., Mosakowski et al., 2013; Winans-Solis, 2014) that show positive expectations and perceptions about the participation in SL. Although caution should be taken when interpreting inferential analyses with data obtained from each item independently, as was the case, we highlight the apparent impact of the SL experience on students, namely the recognition of the usefulness of the curricular contents for the service performance in the AFL students, the usefulness of the service for the understanding of the curricular unit contents in Psychology and AFL students, and the change in life purpose of the AFL students. In line with what was recently highlighted by Pais et al. (2022), it also emerges from our study that the contact with practical and real contexts of intervention enabled by the SL experiences gives meaning to the academic knowledge and skills they acquire throughout their training and allows them - ultimately - to understand how they can develop their professional activity in the real world. It is, therefore, suggested that the SL experience, by combining theory with practice, enables students to mobilize skills such as critical thinking, adaptability, and flexibility to articulate different knowledge and perspectives, which is also associated with the benefits and knowledge arising from an experience of “service to others” which would not otherwise take place.

In the meantime, the increase in pro-social behavior in the AFL students after conducting the SL experience is noteworthy. Previous studies (e.g., Smith, 2008) highlight how this experiential approach provides opportunities for participants to develop important relationships with others, whom they help meet needs while developing an “ethics of care” oriented toward social good and strengthening civic engagement (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2021; Ribeiro et al., 2021). By observing the increase of pro-social behaviors only in AFL students, we hypothesize that students in Psychology and Social Work courses would already be – by the nature of their chosen courses - more oriented towards an altruistic vision and action, admitting a “ceiling effect” that constrains the existence of significant increases at this level.

Regarding life goals, there was an increase in religious goals among Psychology students after the SL experiment, but also in the control group, in this case together with political goals. In the case of Social Work students, it is interesting to note that the experimental group stands out for the increase - compared to the control group - of political, hedonistic, personal development, and wellbeing goals. In the case of AFL students, the increase in relationship, hedonic, personal development, and wellbeing goals is highlighted, with significant increases in the experimental group but not in the control group. Comparing the three courses, after the SL experience, only differences in social goals are evident, namely between AFL and Social Work.

In summary, the previously hypotheses were only partially confirmed, that is, (i) in each course, participants in both groups (experimental and control) showed differences at pre-test (H1) and post-test (H2) in the subscales related to expectations of the service-learning experience vs. learning in the course units and life goals, but not in the civic and social competences, and these differences were not always in favor of the experimental group, as initially predicted; (ii) in each course, contrary to what was predicted (H3), there were statistically significant differences from pre-to post-test in the control group, in the variables Learning-related expectations and life goals (and in civic and social skills but only for the AFL course); these differences showed an increase or decrease depending on the variables under analysis; (iii) in the Psychology course there were no differences from pre to post-test in the experimental group on the variables relating to the learning-service expectations and civic and social skills, but there were for life goals; on the opposite, in the Social Work and AFL courses, there were differences from pre to post-test in the experimental group on the service-related expectations and on the civic and social skills, but not on life goals. Moreover, these differences were not always in the direction of higher results at post-test (H4); and finally, the three courses in the experimental group (SL) did not show, at pre-test, differences with the service-learning expectations, nor in civic and social skills, as anticipated, but did showed differences in life goals (H5); and, as for the post-test, there were differences between the three courses (H6) in terms of the service-learning expectations (with more favorable results for Psychology and SW), the impact of the service-learning experience (with more favorable results for AFL students), and the life goals (with more favorable results for SW and AFL).

Thus, overall, the SL experience seems to have an effective impact on many students, catalyzing their learning processes and psychological development, expressed for example in their life goals, as evidenced also in previous studies (e.g., Conway et al., 2009). Furthermore, the apparent effect of SL on students’ engagement with social issues, examples of which include pro-social conduct, social and political goals, point – as in previous studies (e.g., Opazo et al., 2018) – to a potential development of awareness of their agency in transforming social inequalities. The focus on social and political goals leads us to consider that students critically go further when they reflect on the social realities they face, empowering them to develop a sense of mission and active citizenship. Being part of an SL experience seems, in some way, and as also pointed out by previous authors (e.g., Pais et al., 2022), to predispose students to reflect on the impact that their actions can have on the populations they serve, particularly when the objective is to empower people. In other studies (e.g., Billig et al., 2005; McIlrath et al., 2019), students participating in SL experiences have demonstrated more internalized moral standards, sensitivity to their communities and their needs, and stronger beliefs that one can make a difference in the world. From Reinders and Yourniss’ (2009) longitudinal study examining elements of SL activities and how students experienced or interpreted them, it is evident that – over time – having direct interactions with people in need increases their perception of being helpful to others which, in turn, leads to greater civic engagement.

Although the results have been less consistent than expected, they support the use of the SL methodology and are in line with what is proposed in the Declaración de Bolonia (1999), emphasizing that higher education institutions should train professionally competent and socially responsible citizens, critical of injustice and communally participative, in order to contribute to the improvement of society, disadvantaged people and groups, and the environment.

Limitations and future research

The results of this study, although very exploratory, can be used to guide decisions around curriculum development and implementation of SL projects but should be interpreted in light of important limitations. First, while relying on a longitudinal design and comparison with control groups, the study used convenience sampling, the number of participants should have been higher and similar for the different groups, response rates were low (compared to the total number of students) and, the SL methodology was applied in two courses to 3rd year students and on the other course to 1st year students. In addition, other factors such as time/maturation and other courses the students were taking at the same time could have accounted for some differences between the first and second assessment moments (which may even account for some differences found between pre and post-tests in the control groups).

Second, all assessments were based on students’ self-reports, so the relationships between variables should be considered sparingly. It would be interesting to be able to rely on the evaluation of others (e.g., professors, peers) about the changes related to the experience. Furthermore, it is unknown how long the positive changes will persist, since only two moments (i.e., pre and post-test) were evaluated.

The time elapsed between the pre-test and post-test moments (February and May) may also be a determining factor for the results obtained. Several authors (e.g., McLeod, 2003) have discussed the “ideal time” that should separate these two assessment moments to capture the true change caused by the intervention and not the impact of other factors such as memory, maturation, or life experiences.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, this study suggests that SL can serve as an effective educational approach to strengthen diverse student competencies, promoting – in academic terms – a more holistic pedagogy that favors the integral development of the participants, while allowing the university to go beyond its walls.

Practical implications

Despite its limitations, our study holds significant practical and intervention-related implications that are highly relevant to educators and those involved in shaping curricular possibilities in higher education. By providing empirical evidence, our study confirms the benefits of Service-Learning (SL) methodology in higher education. Our findings reinforce that the implementation of SL in higher education offers a compelling model for integrating academic learning with community service. In the current landscape of global educational trends, universities are uniquely positioned to address the needs of students and society. They bear the responsibility of preparing citizens who can drive change, engage in social and political action, and carry academic knowledge. Their mission and resources allow them to cultivate future leaders who can navigate the complexities and diversities of the twenty-first century, fostering the conditions for the development of well-informed and responsible individuals.

Understanding these processes can inform the development of interventions that support and enhance the natural growth of wellbeing or disrupt negative trends. Although the studies concerning SL do not provide definitive answers, they do provide valuable insights into potential possibilities. For instance, Martin and Kilgo (2015) discovered that being part of a “structured learning community,” where coursework is completed with a consistent group of students, predicted wellbeing over both one-and four-year periods. Additionally, also important, academic achievement and wellbeing may have a reciprocal causal relationship (du Toit et al., 2022).

Also, educators and institutions interested in implementing SL programs, should consider that, when engaged in service activities, students actively sought to establish a meaningful connection between their classroom learning and its practical application in the real world (Li et al., 2016). The improvements in their learning outcomes provided positive reinforcement, allowing students to recognize the value of their education. Concurrently, students gradually became aware that their strengths and efforts made a difference and brought value to those they served (Pinto and Costa-Ramalho, 2022). This perceived value, both for themselves and the recipients of their service, played a crucial role in shaping the meaning they derived from their service-learning experiences. Students began to view service tasks as significant and worthwhile endeavors, dedicating themselves wholeheartedly to such activities. In essence, acts of charity and academic achievements both contribute to students’ construction of meaning regarding service-learning, expanding their perceived value to encompass not only their academic gains but also the well-being of others.

From our practical work, extensive literature review and the results of this study, we can thus suggest some good SL practices: (a) learning and service goals should be intertwined and unified; (b) student assignments, classroom activities and assessment are purposefully structured to align and complement the experiences in the community; (c) the community partnership is characterized by continuous collaboration, starting from the initial planning stages until the project’s completion; (d) the experience is integrative, fostering connections between students’ in-class and out-of-class activities, and encouraging the integration of diverse perspectives and knowledge from all participants; and, (e) the pedagogy is intentionally crafted to be adaptable, allowing for dynamic situations and responsiveness to the capacity-building needs and opportunities of all individuals involved.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Católica Research Centre for Psychological, Family and Social Wellbeing (CRC-W). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Billig, S. H., Root, S., and Jesse, D. (2005). “The relationship between the quality indicators of service-learning and student outcomes” Improving service-learning practice: Research on models to enhance impacts, 97–115.

Celio, C. I., Durlak, J., and Dymnicki, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of service-learning on students. J. Exp. Educ. 34, 164–181. doi: 10.1177/105382591103400205

Chiva-Bartoll, O., Ruiz-Montero, P. J., Olivencia, J. J. L., and Grönlund, H. (2021). The effects of service-learning on physical education teacher education: a case study on the border between Africa and Europe. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 27, 1014–1031. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1756748

Conway, J. M., Amel, E. L., and Gerwien, D. P. (2009). Teaching and learning in the social context: a meta-analysis of service learning's effects on academic, personal, social, and citizenship outcomes. Teach. Psychol. 36, 233–245. doi: 10.1080/00986280903172969

Declaración de Bolonia (1999). Declaración conjunta de los Ministros Europeos de Educación [joint declaration of the European ministers of education]. Available at: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dctm/boloniaeees/documentos/02que/declaracionbolonia.pdf?documentId=0901e72b8004aa6a

du Toit, A., Thomson, R., and Page, A. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies of the antecedents and consequences of wellbeing among university students. Int. J. Wellbeing 12, 163–206. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v12i2.1897

Felten, P., and Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2011, 75–84. doi: 10.1002/tl.470

Fiske, E. B. (2001). Learning in deed: the power of service-learning for American schools Ohio State Univ: Columbus. W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Folgueiras, P., Aramburuzabala, P., Opazo, H., Mugarra, A., and Ruiz, A. (2020). Service-learning: a survey of experiences in Spain. Educ. Citizen. Soci. Justice 15, 162–180. doi: 10.1177/1746197918803857

Henry, S. E., and Breyfogle, M. L. (2006). Toward a new framework of “server” and “served”: De (and re) constructing reciprocity in service-learning pedagogy. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 18, 27–35.

Li, Y., Guo, F., Yao, M., Wang, C., and Yan, W. (2016). The role of subjective task value in service-learning engagement among Chinese college students. Front. Psychol. 7:954. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00954

Lin, L., and Shek, D. T. (2021). Serving children and adolescents in need during the covid-19 pandemic: evaluation of service-learning subjects with and without face-to-face interaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042114

Lin, L., Shek, D. T., and Li, X. (2023). Who benefits and appreciates more? An evaluation of Online Service-Learning Projects in Mainland China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Res Qual Life 18:625–646. doi: 10.1007/s11482-022-10081-9

Martin, G. L., and Kilgo, C. A. (2015). Exploring the impact of commuting to campus on psychological well-being. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 2015, 35–43. doi: 10.1002/ss.20125

McDougle, L. M., and Li, H. (2023). Service-learning in higher education and prosocial identity formation. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 52, 611–630. doi: 10.1177/08997640221108140

McIlrath, L., Aramburuzabala, P., and Opazo, H. (2019). “Europe engage: developing a culture of civic engagement through service learning within higher education in Europe” in Embedding service-learning in higher education. Developing a culture of civic engagement in Europe. eds. P. Aramburuzabala, L. McIlrath, and H. Opazo (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.), 69–80.

McLeod, J. (2003). Doing counselling research. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks: California: Sage Publications Ltd.

Mosakowski, E., Calic, G., and Earley, P. C. (2013). Cultures as learning laboratories: what makes some more effective than others? Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 12, 512–526. doi: 10.5465/amle.2013.0149

Opazo, H., Aramburuzabala, P., and Ramírez, C. (2018). Emotions related to Spanish student-teachers’ changes in life purposes following service-learning participation. J. Moral Educ. 47, 217–230. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1438992

Pais, S. C., Dias, T. S., and Benício, D. (2022). Connecting higher education to the labour market: the experience of service learning in a Portuguese university. Educ. Sci. 12:259. doi: 10.3390/educsci12040259

Pinto, J. C., and Costa-Ramalho, S. (2022). Boost me up!: promoting and supporting engagement, learning and wellbeing. Oral presentation of Service-Learning Experiences. ORSIES–Observatório da Responsabilidade Social e Instituições do Ensino Superior.

Prado, E. L.-d.-A., Higuera, P. A., and Carvajal, H. O. (2020). Diseño y validación de un cuestionario Para la autoevaluación de experiencias de aprendizaje-servicio Universitario [design and validation of a questionnaire for the self-evaluation of university service-learning experiences.]. Educ. XX1 23, 319–347. doi: 10.5944/educXX1.23834

Queiruga-Dios, M., Santos Sánchez, M. J., Queiruga-Dios, M. Á., Acosta Castellanos, P. M., and Queiruga-Dios, A. (2021). Assessment methods for service-learning projects in engineering in higher education: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 12:629231. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.629231

Reinders, H., and Yourniss, J. (2009). School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 10, 2–12. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_1

Ribeiro, Á., Aramburuzabala, P., and Paz, B. (2021). Reflections on service-learning in european higher education. RIDAS 12, 3–12. doi: 10.1344/RIDAS2021.12.2

Roberts, B. W., and Robins, R. W. (2000). Broad dispositions, broad aspirations: the intersection of personality traits and major life goals. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 1284–1296. doi: 10.1177/0146167200262009

Salam, M., Iskandar, D. N. A., Ibrahim, D. H. A., and Farooq, M. S. (2019). Service learning in higher education: a systematic literature review. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 20, 573–593. doi: 10.1007/s12564-019-09580-6

Santos-Rego, M. A., Mella Núñez, Í., Naval, C., and Vázquez Verdera, V. (2021). The evaluation of social and professional life competences of university students through service-learning. Front. Educ. 6:109. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.606304

Smith, C. M. (2008). Does service learning promote adult development? Theoretical perspectives and directions for research. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2022, 1–4. doi: 10.1002/ace.20462

Sotelino-Losada, A., Arbués-Radigales, E., García-Docampo, L., and González-Geraldo, J. L. (2021). Service-learning in Europe. Dimensions and understanding from academic publication. Front. Educ. 6:4825. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.604825

Tijsma, G., Hilverda, F., Scheffelaar, A., Alders, S., Schoonmade, L., Blignaut, N., et al. (2020). Becoming productive 21st century citizens: a systematic review uncovering design principles for integrating community service learning into higher education courses. Educ. Res. 62, 390–413. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2020.1836987

Veiga, N., Couto, P., Ribeiro, C., Ferreira, A., Ribeiro, L., Themudo, C., et al. (2021). “Service learning at Universidade Católica Viseu – a pilot study” in Transformación universitaria. Retos y oportunidades ( Salamanca: Spain. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca), 31–38.

Waldner, L. S., Widener, M. C., and McGorry, S. Y. (2012). E-service learning: the evolution of service-learning to engage a growing online student population. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 16, 123–150.

White, A. E. (2001). A meta-analysis of service learning research in middle and high schools. Thesis, Dissertations, Student Creative Activity, and Scholarship. 67. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slcedt/67

Keywords: service-learning, traditional teaching-learning contexts, expectations and impact, social and civic skills, life goals

Citation: Pinto JC and Costa-Ramalho S (2023) Effects of service-learning as opposed to traditional teaching-learning contexts: a pilot study with three different courses. Front. Educ. 8:1185469. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1185469

Edited by:

José Carlos Núñez, University of Oviedo, SpainReviewed by:

Kivanc Bozkus, Artvin Çoruh University, TürkiyeLuis J. Martín-Antón, University of Valladolid, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Pinto and Costa-Ramalho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: J. C. Pinto, am9hbmFjYXJuZWlyb3BpbnRvQHVjcC5wdA==

J. C. Pinto

J. C. Pinto Susana Costa-Ramalho

Susana Costa-Ramalho