95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 10 May 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1182615

This article is part of the Research Topic .Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Assessment and Improvement of Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: A World-Wide Kaleidoscope View all 17 articles

Introduction: Families with young children who face economic and related adversities are the most likely group to miss out on the advantages of regular sustained participation in high quality early childhood education and care. In Australia, there are an estimated 11% of children assessed by teachers to have two or more developmental vulnerabilities and many of these children are living in economically disadvantaged contexts. Government policy in Australia aspires to provide universal access to Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) services to support children’s outcomes and ensure workforce participation, but policy falls short of ensuring all families can take up high quality early childhood education and care. Government responses to the Covid crisis saw significant changes to the ECEC policy and funding mechanisms. It is timely therefore to reflect on the level of ‘competence’ in the Australian ECEC systems. Coined this term to refer to a system that is sustainable, inclusive, and effective for all families.

Methods: Using a Delphi methodology, we coalesced the insights of high-level stakeholders who have expertise in delivering services to families experiencing adversities and noted points of consensus and of divergence among these stakeholders. We have taken up the challenge of considering the Australian system from the point of view of families who typically find services hard to use.

Results and Conclusion: We put forward a model that frames the characteristics of services that can inclusively engage with families - Approachable, Acceptable, Affordable, Accessible and Appropriate. We argue that more needs to be known about appropriateness and what effective pedagogy looks like on the ground for families and children.

Child poverty gets under the skin. It shapes how children grow and what they know. It can trigger chronic, debilitating, enduring health conditions (Boyce et al., 2021). Poverty influences how people on the street and in institutions speak to them and to their family. As one young mother noted: ‘teachers judge people like me like a horse – by my teeth and my shoes’ (Skattebol et al., 2014). Poverty dictates the confines of everyday life and limits young children’s experiences. Parental income is the key influence on educational trajectories (Spencer et al., 2019; Burley et al., 2022). Despite Australia’s significant wealth, one in six Australian children live in poverty with nearly 200,000 of these children living in ‘severe poverty’ (Duncan, 2022). Whilst Australia has higher rates of intergenerational income mobility than many other advanced nations, rates of widening income inequality are likely to result in less upward intergenerational mobility in coming generations. Currently, nearly a third of those who experienced childhood poverty themselves are likely to have children who also experience income poverty in their lifetime and this proportion is rising not going down (Corak, 2020). Further, the opportunity for mobility has a regional dimension and is associated with school attendance and the strength of regional labour markets (Deutscher and Mazumder, 2020). Those living in severe poverty are often also living in deep isolation from services and family/friendship networks (Duncan, 2022). There is wide consensus across health, economics and education disciplines that show that intervening early in children’s lives is not only critical for the child themselves but it also makes economic sense (Wood et al., 2020). Universal high quality Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) holds promise as one of the few rare policy interventions that can offer significant economic and social dividends. As noted by the 2023 Productivity Commission inquiry into universal childcare, “a great early childhood education and care system pays a triple dividend – it sets children up for a great start in life, helps working families to get ahead, and builds our economic prosperity by supporting workforce participation.”1

This paper will showcase aspects of service delivery that work for families who experience poverty. We coalesce insights from high level policy makers and provider organisations that have experience of delivering effective ECEC services to these families. We address the question of what an effective inclusive service is, offer a framework for thinking through the elements that make services easy to use, and identify gaps in our current policy and practice knowledge.

The last two decades have seen policy makers, providers, practitioners and philanthropists all make considerable efforts to tune policy settings and service design to the needs of families in disadvantage so they can engage with ECEC. Administrative data indicates more children are enrolled in ECEC in the year before school, but these efforts still miss a significant minority of young children (Goldfeld et al., 2022). Whilst policy sometimes rationalises children missing out on ECEC as an effect of parental choice, research demonstrates ECEC service systems are unresponsive at a macro level and there are structural barriers facing families in disadvantage (Vandenbroeck and Lazzari, 2014).

International reviews of effective inclusive services and interventions shows they are embedded in competent macro, meso and micro systems (Urban et al., 2012). These authors state:

‘competence’ in the early childhood education and care context has to be understood as a characteristic of the entire early childhood system. The competent system develops in reciprocal relationships between individuals, teams, institutions and the wider socio-political context. A key feature of a ‘competent system’ is its support for individuals to realise their capability to develop responsible and responsive practices that respond to the needs of children and families in ever-changing societal contexts. At the level of the individual practitioner, being and becoming ‘competent’ is a continuous process that comprises the capability and ability to build on a body of professional knowledge and practice and develop professional values. Although it is important to have a ‘body of knowledge’ and ‘practice’, practitioners and teams also need reflective competences as they work in highly complex, unpredictable and diverse contexts. A ‘competent system’ requires possibilities for all staff to engage in joint learning and critical reflection. This includes sufficient paid time for these activities. A competent system includes collaborations between individuals and teams, institutions (pre-schools, schools, support services for children and families…) as well as ‘competent’ governance at policy level. (p.21).

Australia’s mixed market system of ECEC provision does not deliver equity and so cannot be considered a ‘competent’ system. Studies of Australian ECEC administrative data show that enrolment, attendance, and length of time in programs are proportionally lower in regional, remote, and disadvantaged communities (Hurley et al., 2022). There are lower enrolments in early years services amongst single parent families; families from non-English speaking backgrounds; families with lower levels of education; where both parents are unemployed; families of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent; and families who live in rural or remote areas or socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (Beatson et al., 2022). Furthermore, the programs and initiatives offered in these settings may be more limited rather than more comprehensive. A recent study showed that meal provision – a basic service offering typically associated with children experiencing food insecurity – is less likely to occur in disadvantaged regions than in regions with strong competition for families who can pay high fees (Thorpe et al., 2022).

The Australian government monitors and regulates its marketized system via the National Quality Standard with the aim of improving quality in services. However, National Quality Standard data shows that high quality in educational programming and practice, staffing arrangements and leadership are less common in disadvantaged areas and more common in high income areas (ACECQA, 2021). Settings in disadvantaged areas are more likely to have a waiver on regulations that ensure levels of qualification amongst staff (ACECQA, 2021). One of the largest studies of Australian ECEC quality reported that only 7% of children from low SES families attend services in the top quintile for quality ‘instructional support’, compared to 30% of children from high SES families (Torii et al., 2017). Siraj et al. (2019) argue that the National Quality Standard tools are not comprehensive enough to scaffold the improvements in practice needed in communities where there are high rates of developmental vulnerabilities.

Whilst the National Quality Standard aims to improve services across the board, a recent study on the predictors of improvement trends over time on a national scale show there is greater quality improvement in the not-for-profit sector (compared to the for-profit sector) and in large multi-site organisations (compared to stand alone providers). The Australian mixed market system is comprised of 51% for-profit providers and 80% of these are operated by stand-alone providers. National Quality Standard improvement trends indicate the system does not offer sufficient support for standalone providers to make significant quality improvements over time (Harrison et al., 2023).

Governments have also committed to ensuring each child receives 15 h of early education in the year before school. Improvements in children’s outcomes are strongly associated with the amount of time (sometimes discussed as a ‘dose’ that impacts on outcomes) spent in high quality ECEC. A randomised control trial that delivered high quality ECEC with wrap around services to families with complex needs found significant learning and development benefits from 20.4 h per week of formal early years care and education, compared with a control group receiving 15.7 h per week (Tseng et al., 2019). This ‘dose’ of over 20 h is typically beyond the subsidised hours in childcare and available hours in preschools because many ECEC services structure their daily charges around a 9 (or 12) hour day regardless of how many hours the child attends (Bray et al., 2021). Furthermore, there is growing international evidence that high-quality ECEC from age 3 improves children’s long-term outcomes and that many Australian children do not receive this amount of time (Beatson et al., 2022; Newman et al., 2022). Market mechanisms perpetuate disadvantage for families on lower incomes because parents have less capacity to find, access and pay for high quality care and education which suits their needs (Brogaard and Helby Petersen, 2022). The subsidised or free hours of ECEC provided to families are not sufficient to ensure children get the most out of ECEC. At a macro level, there are not only issues with the availability of high-quality services in disadvantaged areas, and with the system’s potential to improve quality in these areas, but also with the hours of subsidised care available to families experiencing disadvantage.

Families experiencing disadvantage also have higher servicing needs than their better off counterparts. The current system requires service providers to be entrepreneurial and creative in accessing the resources needed to deliver effective services. These challenges are exacerbated in high poverty contexts because community needs are high across a range of domains and communities are often superdiverse and with high rates of forced housing mobility (Skattebol et al., 2016). Services that integrate children’s education with family support services reduce the burden on families of using multiple services, are responsive to local conditions, and offer higher quality ECEC (Geinger et al., 2015), but these services are not available to all that need them. Furthermore, these services need to be able to retain staff over time, and those staff require specific skills for working with crisis situations.

Importantly, attitudinal studies of professionals across education, social work and child protection sectors suggest that ‘poverty-blindness’ is endemic (Simpson et al., 2017; Roets et al., 2020). In line with meritocratic logics, professionals assert they treat people ‘the same’ and address individual risk factors (Fenech and Skattebol, 2021). This approach often renders the systemic barriers families face invisible and places undue burden on families and individuals to meet their needs in a fragmented system. Educators require high levels of reflective and professional skill to navigate socio-emotional dynamics with families in times of crisis and who have experienced negative interactions in the past with professionals. So, whilst a variety of models for effective interdisciplinary work exist, they all require practice structures that support liaison across disciplines and professional communication skills in order to effectively meet the needs of families (Wong and Press, 2017). So for educators and allied professionals to be effective, they need to learn to accommodate a range of disciplinary viewpoints and have good understanding of poverty, how it shapes everyday circumstances and gets under the skin.

Poverty is a multi-layered condition and manifests in highly varied ways in everyday life. Policy and practice responses need to respond to broad-brush effects as well as to situated understandings of the challenges in people’s lives. Whilst poverty is broadly about inadequate resources, it is comprised of intersecting compounding conditions – insufficient income for basic needs, low quality precarious housing, unsafe and polluted neighbourhoods, and reduced access to high quality health and education services (Boyce et al., 2021). Broadly speaking, economic structures of Australian society reproduce disadvantage. Government benefits are well below the poverty line, whilst housing costs increase far more than rent subsidies (Duncan, 2022). People may rely on benefits, on precarious underpaid work in the cash economy, on top ups from family and welfare organisations or all three. Children and families face increasingly precarious labour markets and inequitable schools, so it is difficult to rise out of poverty.

In relation to upward economic mobility, Baldwin (1961/1992) famously observed that “anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.” This statement draws attention to the complex social processes that contribute to poverty. Goods and services are provided by operators who structure pricing in ways that benefit those with good cash flow and disadvantage those with limited expenditure ability. Payment plans without securities often attract higher overall costs. Families with no or poor rental track records often resort to renting properties above market prices. These added costs involve subtle interactions between human and non-human actors, histories and the disruptive force of events. Small cash or resourcing shortfalls can produce cascading shocks that lead to an array of complex problems – schooling change, breakdowns in familial or social networks, homelessness, and mental health struggles. A shock experienced in one domain or part of a social network can produce a shudder in another (Hancock et al., 2018). We know, for example, when some families cannot afford to feed children, they keep them out of school to avoid the stigma of going without (Skattebol et al., 2012). Furthermore, economic geographies determine what is available to be used and to be bought. As families slip into severe poverty, they cluster in places where it is cheapest to live.

Over 20% of Australia’s young people in disadvantaged households live in areas of concentrated disadvantage. Importantly for policy and service provision, 80% are living in mixed SES areas (Abello et al., 2016). Nevertheless, a focus on areas of concentrated disadvantage is critical because these areas rarely improve over time (Duncan, 2022).They are typically in regional or remote areas or regions on urban peripheries with significant public housing and low-quality housing stock and far from vibrant labour markets. As online platforms become more ubiquitous as a starting point for receiving most government and non-government services, the challenges of everyday life are compounded by inadequate digital infrastructure. Poor connectivity is a feature of low-income areas on the periphery of large cities, regional and remote areas (Seymour et al., 2020). Overcrowded houses and unsafe local parks further ramp up the pressures on families with children (Goldfeld et al., 2021).

Australian policy claims that all children – regardless of background or circumstances – have equal educational opportunities. Public resources are distributed universally, some children/areas receive targeted ‘top-ups’ and the underlying policy logic is that with hard work and merit anyone can secure upward mobility. This logic is widely accepted by all economic classes across all developed countries (Mijs and Savage, 2020) and it supresses attention to deep system structures which reproduce inequalities and asserts a ‘cruel optimism’ that anyone can achieve social mobility. Conditionality in welfare (social security) policies suggest that recipients of social benefits are locked into cultures of dependence (Klein et al., 2022). When children face multidimensional disadvantages, parental/caregiver capacities are questioned (Edwards et al., 2015). In short, our safety nets are structured in a way that supports prevailing beliefs that people in poverty lack the grit for upward mobility.

It is important that policy makers and practitioners respond effectively to the debilitating effects of stigma that is associated with poverty. Stigma undermines human dignity and operates as a felt disgrace. Stigma is widely experienced, highly debilitating and associated with toxic stress which can undermine the building blocks of health development (Shonkoff et al., 2021). When a person presents as visibly ‘poor’, they are vulnerable to micro-interactions with others which leave them feeling they have been disgraced. These feelings can flare up in supermarket and pharmacy queues, at school gates, in classrooms, watching television, and in the mirror. Stigma can be public, institutionalised, or internalised (Friedman et al., 2022). People in poverty buffer themselves and those they love from stigma. Children as well as adults may minimise resource shortages, adapt preferences, isolate from better-off counterparts or from services, and build community with others who are similarly marginalised (Redmond et al., 2016; Peterie et al., 2019). Furthermore, families struggling with poverty often have attenuated or closed social networks that can result in limited knowledge about service supports that are available (Mitchell and Meagher-Lundberg, 2017). Children in families experiencing poverty are often protected from the most detrimental effects by their family, who may go without or downplay difficult experiences. They are likely to have different needs, assets and experiences to other children (Hedegaard and Fleer, 2013; Leseman and Slot, 2014; Redmond et al., 2016).

Finally, there is enormous diversity in localised conditions of poverty and how people live in those conditions. Some people live in large, tightly connected family groups and others are in deep isolation, some people are living amongst their better-off counterparts, and some are in areas of concentrated disadvantage. Some have highly developed money management skills and others do not. Some people have intergenerational histories of institutional failures in Australia and others are new arrivals. Ameliorating the effects of poverty in young children’s lives thus requires broad understandings of the conditions of poverty as well as situated knowledge that is developed from the ground up with the people that experience it.

The barriers to participation are well rehearsed in the literature. Structural factors such as affordability and accessibility (available places) continue to headline as barriers to participation in ECEC (The Smith Family, 2020). Low-income parents have fewer financial resources to purchase care, places where they live are often unavailable, and many have little information about costs and subsidies. They may lack transport, be time poor, experience disability and high housing mobility (Wood et al., 2020; Beatson et al., 2022). Effective services respond to this challenge by making themselves easily approachable through outreach initiatives and/or brokerage organisations (Mitchell and Meagher-Lundberg, 2017). Outreach and other brokerage activities intentionally place key service information in places where families go–near supermarkets, health services and local parks (Fenech and Skattebol, 2021).

Cultural safety has been identified in the literature as a significant barrier to the take up of ECEC services. Value dissonances in child rearing, dietary or disciplinary practices can tap into a lack of trust families have in institutions and leave families feeling culturally unsafe (Gilley et al., 2015; Fenech and Skattebol, 2021). However, when families feel culturally safe, they can entrust their children to staff in services. Services are acceptable to families when early interactions are compatible with family communication styles, protocols, and values. Cultural ‘brokerage’ is widely accepted as an important practice for engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families (Barratt-Pugh et al., 2021). The importance of learning from and engaging cultural insiders also applies to other disenfranchised groups including refugees (Mitchell and Meagher-Lundberg, 2017). However, cultural knowledge must be locally specific and developed through respectful relationships with local community members. Local knowledge and diversity training can support educators to attend to micro-interactions, learn about specific family practices, and understand community alliances. Here, situated knowledge of poverty (Skattebol et al., 2016) and how it plays out in people’s lives, is critical.

Another barrier identified in the literature concerns the availability of places. Areas of disadvantage and areas that are further from urban hubs are often ‘under-supplied’. A 2022 report that mapped childcare provision to demographics across Australia found that 568,700 children aged 0–4 years, or 36.5%, live in neighbourhoods classified as ‘childcare deserts’ defined as such because there are over three children per childcare place (Hurley et al., 2022). Similar trends have been observed in studies of attendance rates (Pascoe and Brennan, 2018). For families struggling with basic resourcing, the idea of ‘availability’ needs to be considered over a range of timeframes – daily, weekly and over the stages of a year. Flexible session times support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families who need to return home to country to sustain family and spiritual connections and are critical for families who are mobile for periods because of family violence (Barratt-Pugh et al., 2021).We know that surplus capacity is financially challenging for services viability (Bray et al., 2021, p302), but when a service is run at full capacity they often cannot accommodate families whose days and hours of employment change (Cortis et al., 2021). In terms of competent ECEC systems that can accommodate family needs for flexible hours, governments would need to systematically monitor childcare availability and develop targeted solutions that involves funded spaces to be held available for families with complex needs (Wood et al., 2020).

Affordability is a key barrier for many families. Attendance in ECEC services decreases the lower the family income and the higher the level of financial stress. Only 18.2% of families with an income of <$600 per week income were using formal childcare compared to 33.8% of families whose income exceeds $1,000 per week [Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2018] Furthermore, the capacity to pay is not fixed and many families have changing income and financial circumstances. These families also face significant administrative burdens in constantly updating income statements to access subsidies.

Lastly, sustained attendance in ECEC requires that services are appropriate and useful for families and help them meet the goals they have for their children – such as learning for school readiness or learning that helps children establish cultural group membership. Literature on pedagogical approaches to children experiencing poverty is scarce. We do know that educators do not always seek to understand the knowledge children bring to ECEC settings. Simpson et al. (2017) noted that practitioners working in high poverty contexts lack poverty sensitivity and deliver standardised rather than responsive practices. Similarly, in Australia studies have found that educators are most likely to consider family cultures and knowledge without finding out how the socio-economic conditions of everyday life intersects with culture and knowledge (Nolan, 2021).

Learning experiences are most effective when they are tailored to knowledge that children have gained through daily experiences so they can engage in sustained shared thinking with educators and peers (González et al., 2006; Hedegaard and Fleer, 2013; Taggart et al., 2015; Siraj et al., 2019). This knowledge has been termed children’s funds of knowledge (González et al., 2006). In this approach to pedagogy, educators seek to identify the knowledge of the family, informed through culture and history as well as the practices of teaching and learning in the child’s home. Children are most competent in the knowledge and practices they are most familiar with, so this foundation is used in teaching to ensure developmental gains are made through the zone where established and new knowledge interact.

A small body of research indicates that it can be challenging for teachers and practitioners to access the funds of knowledge of people who have been stigmatised and excluded. Families may doubt their own knowledge due to past experiences of deficits being attributed to them as individuals or to their family situation and may value their privacy (Llopart and Esteban-Guitart, 2017). There are examples of effective practice from practitioners and teachers who are trained in theories of cultural capital, Critical Race Theory, culturally relevant pedagogies, anti-deficit theory and strategies for critical reflection. Although much of this research is focussed on school aged children (Lampert and Burnett, 2016) there are some good ECEC examples (see Hedges et al., 2011; Arndt and Tesar, 2014). One of the most valuable contributions of the funds of knowledge approach is that it challenges the idea that poor families have less knowledge, poorer organisational skills and less capacity to learn than other people. It leverages the knowledge in families in the learning experiences to improve children’s learning outcomes.

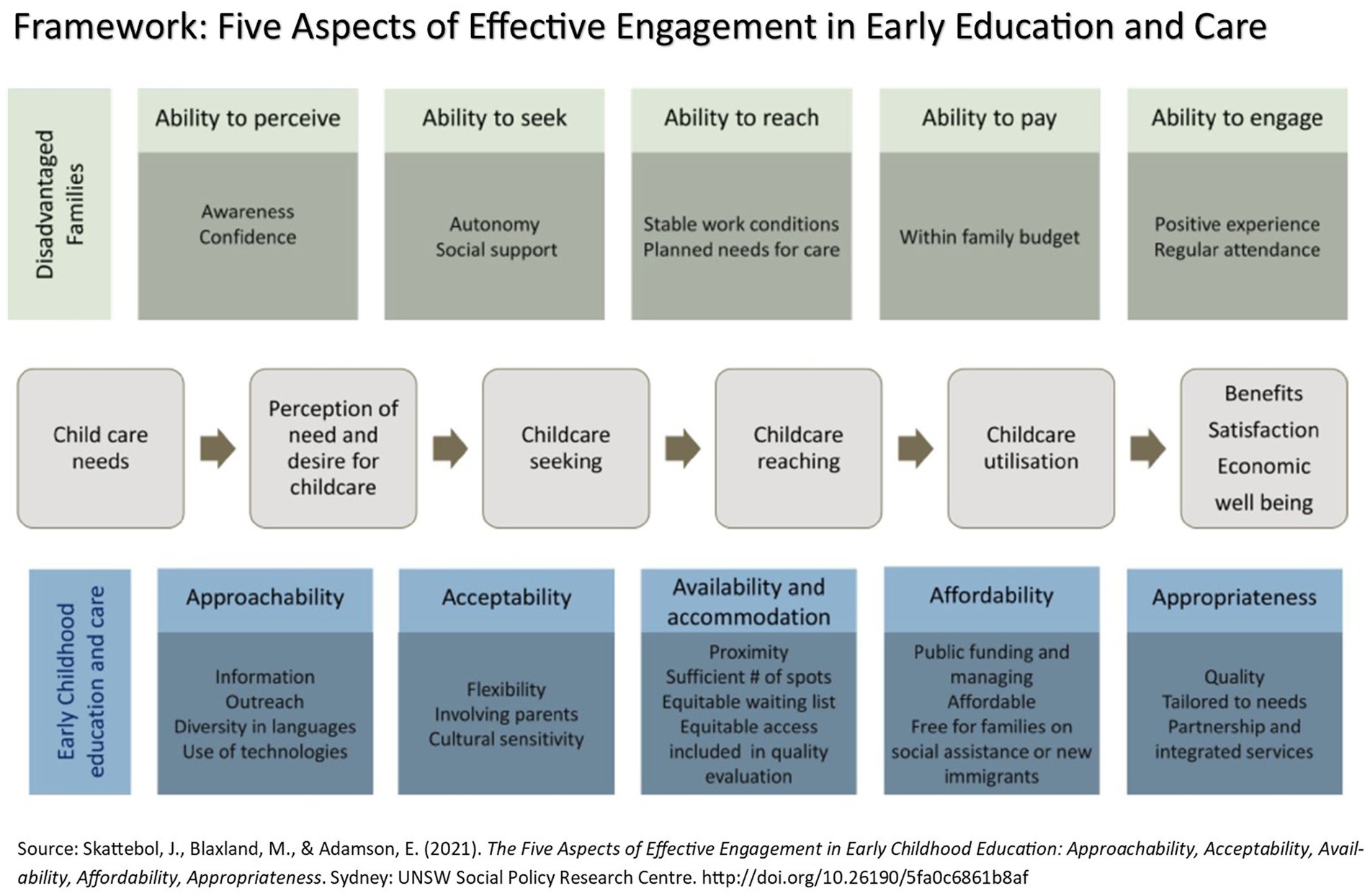

We position the above enablers of participation in quality ECEC in an ecological framework – originally designed to assess the health service characteristics that support the people who find health services hard to use (Levesque et al., 2013). It was adapted for assessment of ECEC services (Archambault et al., 2020). The benefit of the model is that moves away from deficit understandings of families who find services hard to use and focuses instead on the material, social and internal resources that families have and how service structures and practices interact with these resources. We have adapted the model further (Figure 1) to place family resources as the starting point. We labelled the continuum of service characteristics using alliteration (approachability, acceptability, accessibility, affordability, and appropriateness) to make it easy to remember. This model maps well to our findings as well as to the literature.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework of access to quality ECECs for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In the 5 Aspects of Engagement framework, we have conceptualised the aspects as what families need to see and experience from services so they can engage with them. On the left, at the most minimum level – approachability – families need to know of a service and connect before any engagement can happen. On the right, at the deepest level of engagement – appropriateness, services meet all the needs of children and their families. The sequencing of the aspects follows the steps a family in deep isolation goes through as they take their child to preschool. The different aspects may be more or less important as the family’s connectedness to the system develops. Furthermore, the aspect of acceptability may be vitally important at every step for some families yet recede in urgency for others. The framework emphasises the importance of the complementarity of interventions between different partners working towards the common goal of equitable access to services.

This model does not address all the elements required to make a competent early childhood and care system in the definition coined by Urban et al. (2012). Questions about workforce attraction and retention, leadership and governance are outside the scope of this paper and of the model. The model is concerned with what families might need to see and experience from educators and the processes and structures in services to they are easy to use.

This paper draws on data from research that aimed to identify the characteristics of services that effectively address the needs of families experiencing adversities and disadvantage. We conducted a review of international literature (including the ‘grey’ literature) and interviewed high level stakeholders (policy makers and large organisations) using a Delphi methodology. A Delphi method approach was used to elicit the perspectives of policy makers and service providers known for their interest in service delivery to families experiencing disadvantages. The Delphi technique (Diamond et al., 2014) is a two-step iterative communication process aimed at conducting detailed examinations and discussions of a specific issue, in this case, equitable access to high quality ECEC. The method allows participants to think independently and researchers to build consensus, identify outlier opinions and neutralise the power relations between experts. It supports co-thinking of complex problems and enables participants to scrutinise each other’s responses and revise or refine their thinking. It allowed us to address the potential halo effect of key ECEC policy architectures – the National Quality Standard and Early Years Learning Framework which have been collaboratively developed in the sector over a long period of negotiation with all sector stakeholders and government (Sumsion et al., 2009). The halo effect occurs when high profile experts, or in the ECEC case, when groups of high-profile experts have designed something together and others are wary of expressing dissenting opinions. Our interest was to investigate if these guiding practice architectures are effective enough to support high quality practice in disadvantaged contexts. The project aimed to understand whether there are aspects of effective practice that sit outside existing quality practice architectures, such as the Early Years Learning Framework and National Quality Standard.

We established an advisory group from key advocacy organisations to help identify participants with expertise on services in high poverty contexts and to shape findings. The selection criteria were that the participants were at senior executive level in an organisation with a track record of including children who typically miss out on ECEC. We did not include participants in stand-alone services. Our participants were in not-for-profit2 provider organisations (both large and medium size; n = 9), in senior government policy positions (n = 3), training organisations specialising in services in high poverty contexts (n = 3), allied services – in partnership (n = 2), philanthropic brokerage organisations (n = 3), Indigenous specific services (n = 2), a university/government partnership aimed at improving pre-school attendance (n = 1). We conducted 23 semi-structured telephone interviews with participants. A review of the literature informed the first round of questions which included identifying the characteristics of families who find services hard to use, utility of subsidy processes, provider costs, strategies for access, strategies for settling families into services, pedagogical practices, quality standards and monitoring, challenges specific to regional, remote, and Indigenous communities, and reflections on the ideal ECEC system. The research team then conducted an iterative thematic analysis (Neale, 2016) of the interviews, beginning with codes based on a review of the literature. Participants were then sent a summary report that noted points of consensus and dissensus and were invited to further reflect on the scope and geographical reach of brokerage available, the outreach, access and flexibility approaches summarised, costs of inclusion and how these can be financed, examples of pedagogical excellence, and the comprehensiveness of existing quality frameworks. The second round of data collection encouraged the expression of opinions, critique, and revisions of judgement by enabling participants to comment on the positions of anonymous others in a cyclic data refinement process. Subsequent data was then subject to higher order coding and the 5 Aspects framework was developed.

This section presents the strategies and practices that stakeholders had seen ease the engagement process for families who find services hard to use. They identified families with the following characteristics as more likely to find services hard to use – low-income families (in particular, those facing intergenerational disadvantage with negative experiences of institutional failures), families with contact with the child protection system, children and families experiencing trauma, families with mental health issues, as well as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, asylum seekers and refugees. The findings are presented below and organised through the 5 Aspects of Engagement framework.

Participants discussed outreach and brokerage as essential activities aimed at bringing ECEC services to families who are isolated or excluded. The outreach/brokerage continuum moved from connecting directly with families to enabling families to connect with other organisations. Stakeholders emphasised the need for resources that build family’s knowledge of what is available in the early years system, opportunities to build relationships with services before committing to enrollment, practical help with administration and paying childcare debts. Most highlighted the need for professional networking so educators could build trusting relationships with other professionals who may have the trust of families in deep isolation.

Overall, there was a high level of consensus on strategies for outreach. Examples of access and outreach principles and practices included:

• Soft entry points – playgroups, BBQs and other community events.

• Opportunities for families to observe what happened in services without being formally enrolled.

• Information sharing about the Australian ECEC system to families.

• Practical supports such as coordinating transport.

• Connecting with other support services, such as disability services, health providers, child protection.

• Peer to peer engagement/activities.

• Strong service networks and interagency collaboration.

Many organisations offered light touch community events throughout the year.

We offer a community hall where there might be a day for young parents to come in and just connect with others. It could be focused around reading. Generally, they are fairly broad sorts of occasions to connect community, resident to resident, not-for-profit to not-for-profit. We work with probably a dozen different community groups like this and run a variety of these types of things.

Some participants noted that organisations need to continually reflect on who lives locally but are not using services and why.

“Who is not here?” is important for thinking about who is not accessing ECEC services and what could be done differently to support their engagement. A local organisation, agency or professional is likely to know these families and children but an ECEC service might not have any idea or the capacity to identify them.

Effective outreach was offered by a range of service types – integrated child and family services, standalone long day care or kindergarten services. Typically, brokerage initiatives found places for families and created conditions which enabled families to use services. Those that offered financial help to support with debts were funded through philanthropic organisations. They were often embedded in place-based initiatives where there were concentrations of families who do not use ECEC. Importantly for policy, most respondents saw that outreach initiatives were highly successful but that the distribution of outreach activities was ‘ad hoc’ across the sector and missed many families in need.

The challenge of delivering acceptable culturally safe services to families starts at the first point of contact and continues throughout the family’s connection to the service. Participants noted that cultural safety for families was essential but required support and training to establish. They described acceptability as a feeling that needed to be generated rather than a set of prescribed cultural practices.

I think if it’s really high quality, you can walk into a service and right from step one, you’d be able to feel that the service really wants to work with me and my child. And even that might take a long time, but you can feel it every step of the way.

Our informants agreed that strong relationships with families involved reflecting and valuing cultural difference. Cross-cultural competence based in reflexivity was considered foundational to effective practice.

staff need to be able to acknowledge and be really aware of their own biases, and the way they may interact with a family, based on their bias and they need to be able to put that to one side.

Learning about how children are reared in different cultures was essential. One informant described the need for service providers to be ‘researchers of their own community’, so they could meet family needs for safety. Another noted:

You definitely have to have a good knowledge of their culture, and what are cultural norms for them, and how is that reflected in your services; are they the same thing?

Like, we encourage children to take their shoes off, and run around and play, and get muddy and dirty; but that’s not cultural norm for some of our families. When the family comes to pick them up, and they don’t have their shoes on, or they’re missing a sock, that’s a really big thing for them. We’ve got to think, “Okay, well, what is their cultural norm? What are we doing? Are they reflective of that?”

Staffing that reflected diverse cultural groups in the community was seen as a good starting point for delivering services that are acceptable to families. One participant explained this as follows: “they can see themselves in there…that their type of family is okay [there].” Staff who shared a cultural background with families could potentially provide insights into the parents’ views and knowledge about their children’s development. Where educators and families shared a first language other than English, staff could provide translation and interpreter support, and sometimes socio-political histories which supported educators to have better situated understandings of families and what was important to them. Significantly, these activities were often conducted by staff in unpaid time.

Guidance from cultural insiders was considered critical in establishing cultural safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families but most participants felt there were different ways of accessing cultural support to ensure their service was culturally safe and responsive. Some participants emphasised the importance of designated positions in their own organisation.

We do have at least around about four Aboriginal staff members, and we have a community liaison officer, an Aboriginal community liaison officer, who helps us support our families, our Indigenous families, with enrolments, and doing home visits, following them up and things like that.

Other participants felt that ‘cultural brokers’ from within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and migrant communities can be, but do not necessarily need to be, directly employed at the setting. They recognised the importance of responding to the needs of families rather than having a single approach to inclusion. One service provider stated:

We work really closely with an Aboriginal corporation. They partner with us, and we employ an Aboriginal worker. People need choice. So Aboriginal people don't necessarily want to work with an Aboriginal organisation, but they want to have the choice to, or not, and still be able to get safe services.

In addition to employing and building relationships with representatives from the local community, services attempted to design their physical spaces so they could interact with families in ways that were acceptable to them. Interactions needed to be handled with great respect for people’s privacy. Many families did not want others in the community to know their business, so first point of contact services needed to offer discreet places where conversations with families could take place.

The issue of providing safe environments for families who had experienced trauma was raised by all informants. Various trauma and attachment-based approaches that worked with families and children with complex trauma were cited. This work is highly specialised and we cannot do it justice in the scope of this paper. The important finding from these stories is that teams need adequate training and support to address trauma.

Importantly, the need for specialised training extended beyond trauma practices. Participants identified a need to develop skills amongst ECEC staff and educators to build effective and trusted relationships. For this, there is a need for professional learning for existing staff and new graduates about the conditions of poverty broadly and about its many manifestations.

Informants noted that families experiencing poverty often required help navigating government systems and websites, gathering required documentation, finding an available place, completing enrolment forms and practical supports – like transport, printing forms, getting birth certificates and immunizations up to date. We heard examples of providers working to establish this trust directly, and also examples where brokerage agencies established this trust and then made ‘warm referrals’ so that families could easily access services they would find useful. Warm referrals are when service providers select specific services for families and follow through until connections are made (Goldberg et al., 2018). One informant from a small service offering wrap around support observed that warm sustained brokerage was needed with families in deep isolation:

This is easier said than done. You need someone to scaffold the family to move to a service, and almost hold their hands for a while. We quite often had the scenario of a vulnerable family coming to a supported playgroup, where they got to know other people. The playgroup facilitator scaffolded them in that situation, and then they would enroll their child at childcare. The transition could be fine, but other times, maybe it wasn’t. If they didn’t feel as comfortable doing that, we would actually have that worker scaffold the family a bit.

Brokerage organisations supported ECEC services to be accessible as well as supported families to gain access. If small stand-alone providers were not able to provide the support families required brokerage agencies stepped in. One brokerage agency said:

We’ve made it really clear with all the [local] centers we support that if you have families who you think are going to walk away, and you need extra help to make it work for them, give us a call and we’ll see how we can all come up with something together. And that might just be that the centers don’t have the time to sit there, or to go through all the things online with them or apply for birth certificates.

As noted above, many families are not familiar with the ECEC fee and subsidy system. Our informants noted that a significant number of families they worked with were not aware that subsidies were available. In addition, some families did not have the required documentation to apply for fee subsidies (called the Child Care Subsidy) so the process could be challenging and time consuming. The director of a long day care service said:

I will say 50% or more [of newly enrolling families] are not familiar with the Child Care Subsidy. They need advice on how to go about it, what to do, what they need. If we ask, have you enquired about your Child Care Subsidy, some would say, what’s that? So, you have to tell them where to go, what to ask for and how that would influence their enrolment.

Stakeholders also talked about delays in the processing times for families’ fee subsidy applications. Some organisations responded by offering families various kinds of fee relief – reducing or waiving enrolment bonds, or not charging families extra if children stayed overtime. As noted earlier, some brokerage organisations paid childcare debts so families could re-engage with childcare services.

The appropriateness of a service is determined by how well a service can meet a family’s needs over time. Organisations sequenced their orientation and engagement processes in different ways. Some used very light and unstructured processes, whilst others conducted meetings focused on goal setting for children with detail and clarity about how goals would be met.

At the informal end of the spectrum of orientation processes, few demands for information were placed on families. One participant described the need to set up the physical entrances to the service in ways that encouraged families to come with their children and observe without having to speak or engage with workers. They suggested that some families want to get the look and feel for a service before they are given information about the processes and requirements. This service set up a welcoming seating area near the street where families could stop, rest, and allow their children to wander in. Families were enabled to return and remain in this observing space as many times as they wanted. In a similar vein, one provider noted they needed to look at their processes from the point of view of families:

Many of our families have not had any positive experience with any kind of authority, any kind of formal processing. Families who have had difficult immigration processes, fled from a country, come to the country through the ‘not straight’ pathway, even some who have come through the legal straight pathway. It wasn’t until we actually started to reflect on why we were struggling to get a full enrolment process completed and then when we could see we’re throwing all of these documents at families who have just had a life full of documents.”

At the more formal and structured end of the spectrum of orientation processes, families were scaffolded through every element of the service induction via carefully structured relationship building.

So orientation tours- we sit down with the families, talk to them about their needs. It’s sort of like a chat, where we build relationships [and find out] what they want the children to have or experience while they’re here, and what experience previously they’ve had. Then we go around, showing them the premises. We talk about what we teach the children, what the children might learn or do while they’re here, what services we provide – like meals, nappy changing, all the records and charts that are available to them, or how we document and how we get the parents’ input, and what they want the children to learn, too.

Highly structured and thorough orientation process were understood by these stakeholders as central to strong relationship building. Whilst there were different strategies implemented, our informants concurred there needed to be multiple opportunities for families to share concerns and that attachment-based structures were a critical support for educator/family relationships. This typically involved a primary caregiver system where each family is assigned a key worker for their daily communications, with service directors and/or other personnel following up with the families regularly.

Whilst there were differences in approaches to orientation, there was consensus that many families could only stay connected with services when those services were flexible.

Sometimes family circumstances change in an absolute heartbeat. The standard procedure is that if the child is going to cease care with us, we ask for a four-week notice period. But we absolutely need to be flexible if we’ve got a family, which we’ve had a number, who need to go to protective custody, you know, you can’t just say, “Oh, but hang on. We need four weeks’ notice” There are times where you just need to go, “Okay. You need to leave the state. If you can give us a call in a couple of weeks to let us know, we’d love to hear from you”

The need for flexible enrollment and attendance was emphasised for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.

They have often have cultural obligations to respond to the needs of family members, attend funerals and other sorry business, to go back to country for important cultural events, social and spiritual rejuvenation.

The structures of mainstream services and subsidy systems often make it difficult to meet these obligations which are central to the wellbeing of communities and individuals.

When asked about pedagogy there was a high level of consensus in the interviews about the need for quality learning in high poverty contexts. Informants talked about partnerships between families and educators that supported children’s learning. However, there was little discussion about how this could be operationalised in pedagogical practice and few examples were given. Similarly, the Australian Early Years Learning Framework was cited by participants as an effective approach to pedagogy but there was very little elaboration about how experiences of poverty shape children’s existing knowledges and how to work with this.

One informant elaborated on the types of pedagogical support she had witnessed working in professional development in services in high poverty contexts. She noted educators typically held low expectations of children’s learning. Importantly, she observed that educators tended to have an exclusive focus on children’s needs in social–emotional and life skill areas rather than on what they already know:

I’ve found that educators already have a belief that children will not achieve because of what the educator sees as the family circumstances in which the children are experiencing their lives. So, they won’t say these kids have got no hope. It won’t be like that, but it will be, “Oh, we have to take account of the fact that we have to spend a lot of time on routines with these children.”

She proposed that culturally responsive pedagogies required educators to become researchers of their local communities because children learn through playing with familiar things – re-enacting behaviour that they see in the community using pretend and imagination.

This understanding of how children learn underpins what we regularly see in early childhood settings and kinder classrooms where children are offered a play corner where they re-enact going to a restaurant with menus and tablecloths and so on. However, if this experience is unfamiliar to children, it has no meaning. In high poverty contexts, educators need to research the familiar experiences children have like going to the doctor and or a clinic – seeing how oral transactions take place and having a chance to re-enact this experience.

Overall, the interviews suggest that pedagogical approaches are heavily focused on social emotional skills and that dialogic strength-based educator/family partnerships are a key domain of underdeveloped expertise in the sector.

These findings from interviews with 23 high level stakeholders identify the way that micro, meso and macro levels interact in a way that both creates, yet also work to overcome, barriers to engaging with high quality ECEC for children experiencing poverty. A high-quality equitable system requires more than subsidies and available places. It requires multi-level understandings of the effects of living in poverty, policy and practice architectures that address all the barriers families face.

Our study found that we need better understandings of the practices that galvanise the assets in these families and to rethink the training for educators who work with complex issues. Whilst a recent systematic review showed that the qualification levels of educators are paramount for delivering high quality ECEC (Manning et al., 2019), the findings here suggest that practitioners working in high poverty settings must possess knowledge and skills beyond that which is typically credentialled (for elaboration on this argument see Jackson, 2022). Educators go to enormous lengths to mobilise to support in their own and other organisations so that low-income families can engage with ECEC services. These practitioners on the ground are integral to driving these meso-level changes in their organisations, and often play important roles in advocacy to the meso- and macro-level.

Our findings emphasise the importance of outreach and brokerage models that make services approachable, as well as the range of innovative practices and strategies that staff utilise to provide acceptable, accessible, and appropriate services. It is evident that many of these practices are costly and made possible by cross-subsidisation in large organisations, buckets of philanthropic funding and unpaid staff time. These practices are not well accounted for in service budgets or in inclusion funding. This gap in knowledge about what it costs to deliver these services is a critical barrier to the development of inclusive ECEC policy.

Whilst stakeholders recognised the benefits of the National Quality Standard, they also believed that quality in services needed to calibrate to the needs of the local context and much unfunded essential work needs to be acknowledged in quality frameworks. The stakeholders we spoke with all operated within areas of concentrated enduring disadvantage. Investment in ECEC for low-income children and families is largely targeted in low-socioeconomic locations, where there is a concentration of complex needs. Services in these areas tend to be well-rehearsed and networked with other social services. It is also important, however, to consider how providers in mixed socioeconomic areas reach children experiencing poverty (~80% of people in poverty live in mixed SES areas). The service systems in mixed socio-economic areas differ from high poverty contexts and are likely to have far fewer outreach and brokerage programs and/or access to free or low-cost community and social services. Families and children in these areas are often ‘hidden’ and harder to reach if they are not already connected to services. There is not strong evidence about what is needed in these areas.

The knowledge shared by stakeholders provides valuable evidence for providers. However, government investment and strategic planning is required at the systems, or macro-, level to realise these high-quality practices for all children experiencing poverty in socioeconomically diverse and complex geographic locations. Current government policy prioritises investment in fee subsidies for families to improve the affordability of services, yet more investment is required to enable the system to implement effective outreach that reflects the local context and cultural values of families and communities. Consistent with literature that overviews the ECEC system (Bray et al., 2021), stakeholders reiterated that the subsidy system is too complex and creates administrative barriers to children and families trying to access ECEC services. System-wide changes to skills and qualifications required would support educators to enhance their skills in culturally relevant pedagogies and improve the capacity of staff to mobilise the strengths of children and families who experience adversities. Furthermore, there are significant workforce, leadership and governance challenges documented elsewhere that governments need to address (see for example commentary such as “As ECEC battles ongoing workforce crisis, managers need to focus on culture https://thesector.com.au/2023/01/18/as-ecec-battles-ongoing-workforce-crisis-managers-need-to-focus-on-culture/”).

We have seen the governments respond to the sector needs and deliver supply side supports through the Covid pandemic (Plibersek, 2020). These temporary changes at the macro level arguably relieved some of the stresses and barriers previously – and since – experienced by children living in low-income families. Governments have the capacity to make changes, but the early childhood education and care sector still requires more investment for children in disadvantaged contexts to accrue the benefits of high-quality education and care.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JS, MB, and EA conceptualized the project, conducted fieldwork and analysis and contributed to the writing of the report and this article. JS led the writing on this paper and was chief investigator for the project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The research project was funded by the Gonski Institute of Education at UNSW.

We wish to acknowledge our industry partners who offered intellectual guidance and facilitated relationships with key industry people: Gabbie Holden, Manager Research and Policy, KU Children’s services; Elizabeth Death, Chief Executive Officer, Early Learning and Care Council of Australia; Stacey Fox, Research Manager, Front Project; Kate Highfield, Professional Learning and Research Translation, Early Childhood Australia.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/jim-chalmers-2022/media-releases/productivity-commission-inquiry-consider-universal-early

2. ^For-profit providers were included in the potential sample, however none were nominated who met the selection criteria of having a strong record of inclusion.

Abello, A., Cassells, R., Daly, A., D’Souza, G., and Miranti, R. (2016). Youth social exclusion in Australian communities: a new index. Soc. Indic. Res. 128, 635–660. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1048-9

ACECQA (2021). National Quality Framework Annual Performance Report. Australian Children’s education and care quality authority. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-03/NQF-Annual-Performance-Report-2021.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2022).

Archambault, J., Côté, D., and Raynault, M.-F. (2020). Early childhood education and care access for children from disadvantaged backgrounds: using a framework to guide intervention. Early Childhood Educ. J. 48, 345–352. doi: 10.1007/s10643-019-01002-x

Arndt, S., and Tesar, M. (2014). “Crossing Borders and borderlands: childhood’s secret undergrounds” in Children and borders. eds. S. Spyrou and M. Christos (Houndmills: Palgrave mac Millian)

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2018). Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017 Table 5. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/childhood-education-and-care-australia/latest-release (Accessed March 1, 2023).

Barratt-Pugh, C., Barblett, L., Knaus, M., Cahill, R., Hill, S., and Cooper, T. (2021). Supporting parents as their Child’s first teacher: aboriginal parents’ perceptions of Kindi link. Early Childhood Educ. J. 50, 903–912. doi: 10.1007/s10643-021-01221-1

Beatson, R., Molloy, C., Fehlberg, Z., Perini, N., Harrop, C., and Goldfeld, S. (2022). Early childhood education participation: a mixed-methods study of parent and provider perceived barriers and facilitators. J. Child Fam. Stud. 31, 2929–2946. doi: 10.1007/s10826-022-02274-5

Boyce, W. T., Levitt, P., Martinez, F. D., McEwen, B. S., and Shonkoff, J. P. (2021). Genes, environments, and time: the biology of adversity and resilience. Pediatrics 147:e20201651. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1651

Bray, J. R., Baxter, J., Hand, K., Gray, M., Carroll, M., Webster, R., et al. (2021). Child care package evaluation: final report. (Research Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Available at: https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/202212/2021_child_care_package_evaluation_final_report.pdf (Accessed September 20, 2022).

Brogaard, L., and Helby Petersen, O. (2022). Privatization of public services: a systematic review of quality differences between public and private daycare providers. Int. J. Public Adm. 45, 794–806. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2021.1909619

Burley, J., Samir, N., Price, A., Parker, A., Zhu, A., Eapen, V., et al. (2022). Connecting healthcare with income maximisation services: a systematic review on the health, wellbeing and financial impacts for families with young children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:6425. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116425

Corak, M. (2020). Intergenerational mobility: what do we care about? What should we care about? Aust. Econ. Rev. 53, 230–240. doi: 10.1111/1467-8462.12372

Cortis, N., Blaxland, M., and Charlesworth, S. (2021). Challenges of work, family and care for Australia’s retail,online retail, warehousing and fast food workers. Sydney Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Available at: https://www.sda.org.au/download/submissions-publications/Who-Cares-A-fair-share-of-work-care-challenges-of-work-and-family-care-Survey-Report-2021_lowres.pdf (Accessed February 15, 2023).

Deutscher, N., and Mazumder, B. (2020). Intergenerational mobility across Australia and the stability of regional estimates. Labour Econ. 66:101861. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101861

Diamond, I. R., Grant, R. C., Feldman, B. M., Pencharz, P. B., Ling, S. C., Moore, A. M., et al. (2014). Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002

Duncan, A. S. (2022). Behind the line: poverty and disadvantage in Australia 2022. Bankwest Curtin economics Centre focus on the states series Vol. 9. Available at: https://bcec.edu.au/assets/2022/03/BCEC- Poverty-and-Disadvantage-Report-March-2022-FINAL-WEB.pdf (Accessed September 20, 2022).

Edwards, R., Gillies, V., and Horsley, N. (2015). Brain science and early years policy: hopeful ethos or ‘cruel optimism’? Crit. Soc. Policy 35, 167–187. doi: 10.1177/0261018315574020

Fenech, M., and Skattebol, J. (2021). Supporting the inclusion of low-income families in early childhood education: an exploration of approaches through a social justice lens. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 1042–1060. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1597929

Friedman, S. R., Williams, L. D., Guarino, H., Mateu-Gelabert, P., Krawczyk, N., Hamilton, L., et al. (2022). The stigma system: how sociopolitical domination, scapegoating, and stigma shape public health. J. Community Psychol. 50, 385–408. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22581

Geinger, F., Van Haute, D., Roets, G., and Vandenbroeck, M. (2015). Integration and alignment of services including poor and migrant families with young children. Paper presented at the Background paper for the 5th meeting of the Transatlantic Forum on Inclusive Early Years.

Gilley, T., Tayler, C., Niklas, F., and Cloney, D. (2015). Too late and not enough for some children: early childhood education and care (ECEC) program usage patterns in the years before school in Australia. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 9, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40723-015-0012-0

Goldberg, J., Greenstone Winestone, J., Fauth, R., Colon, J., and Mingo, M. V. (2018). Getting to the warm hand-off: a study of home visitor referral activities. Matern. Child Health J. 22, 22–32. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2529-7

Goldfeld, S., O'Connor, E., Sung, V., Roberts, G., Wake, M., West, S., et al. (2022). Potential indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children: a narrative review using a community child health lens. Med. J. Aust. 216, 364–372. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51368

Goldfeld, S., Villanueva, K., Tanton, R., Katz, I., Brinkman, S., Giles-Corti, B., et al. (2021). Findings from the kids in communities study (KiCS): a mixed methods study examining community-level influences on early childhood development. PLoS One 16, e02564311932–e02564316203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256431

González, N., Moll, L. C., and Amanti, C. (2006). Funds of knowledge: theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. New York: Routledge, 1135614067.

Hancock, K. J., Christensen, D., and Zubrick, S. R. (2018). Development and assessment of cumulative risk measures of family environment and parental Investments in the Longitudinal Study of Australian children. Soc. Indic. Res. 137, 665–694. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1607-3

Harrison, L. J., Waniganayake, M., Brown, J., Andrews, R., Li, H., Hadley, F., et al. (2023). Structures and systems influencing quality improvement in Australian early childhood education and care centres. Aust. Educ. Res. 4, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00602-8

Hedegaard, M., and Fleer, M. (2013). Play, learning, and children's development: everyday life in families and transition to school. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1107355303.

Hedges, H., Cullen, J., and Jordan, B. (2011). Early years curriculum: funds of knowledge as a conceptual framework for children’s interests. J. Curric. Stud. 43, 185–205. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2010.511275

Hurley, P., Matthews, H., and Pennicuik, S. (2022). Deserts and oases: how accessible is childcare? Melbourne: Mitchell Institute, Victoria University. Available at: https://vuir.vu.edu.au/44440/1/how-accessible-is-childcare-report.pdf (Accessed February 18, 2023).

Jackson, J. (2022). Qualifications, quality, and habitus: using Bourdieu to investigate inequality in policies for early childhood educators. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 43, 737–753. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2022.2057926

Klein, E., Cook, K., Maury, S., and Bowey, K. (2022). An exploratory study examining the changes to Australia’s social security system during COVID-19 lockdown measures. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 57, 51–69. doi: 10.1002/ajs4.196

Lampert, J., and Burnett, B. (2016). Teacher education for high poverty schools. New York: Springer. 3319220586.

Leseman, P. P. M., and Slot, P. L. (2014). Breaking the cycle of poverty: challenges for European early childhood education and care. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 22, 314–326. doi: 10.1080/1350293x.2014.912894

Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., and Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 12, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

Llopart, M., and Esteban-Guitart, M. (2017). Strategies and resources for contextualising the curriculum based on the funds of knowledge approach: a literature review. Aust. Educ. Res. 44, 255–274. doi: 10.1007/s13384-017-0237-8

Manning, M., Wong, G. T., Fleming, C. M., and Garvis, S. (2019). Is teacher qualification associated with the quality of the early childhood education and care environment? A meta-analytic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 89, 370–415. doi: 10.3102/0034654319837540

Mijs, J. J. B., and Savage, M. (2020). Meritocracy, elitism and inequality. Polit. Q. 91, 397–404. doi: 10.1111/1467-923x.12828

Mitchell, L., and Meagher-Lundberg, P. (2017). Brokering to support participation of disadvantaged families in early childhood education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 43, 952–967. doi: 10.1002/berj.3296

Neale, J. (2016). Iterative categorization (IC): a systematic technique for analysing qualitative data. Addiction 111, 1096–1106.

Newman, S., McLoughlin, J., Skouteris, H., Blewitt, C., Melhuish, E., and Bailey, C. (2022). Does an integrated, wrap-around school and community service model in an early learning setting improve academic outcomes for children from low socioeconomic backgrounds? Early Child Dev. Care 192, 816–830. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2020.1803298

Nolan, A. (2021). Addressing inequality: educators responding to the contexts of young children’s lives? Child. Soc. 35, 519–533. doi: 10.1111/chso.12416

Pascoe, S., and Brennan, D. (2018). Lifting our game. Melbourne: Government of Victoria, 1925551857.

Peterie, M., Ramia, G., Marston, G., and Patulny, R. (2019). Social isolation as stigma-management: explaining long-term unemployed people’s ‘failure’ to network. Sociology 53, 1043–1060. doi: 10.1177/0038038519856813

Redmond, G., Skattebol, J., Saunders, P., Lietz, P., Zizzo, G., O'Grady, E., et al. (2016). Are the kids alright? Young Australians in their middle years: final report of the Australian Child Wellbeing Project. Available at: www.australianchildwellbeing.com.au

Roets, G., Van Beveren, L., Saar-Heiman, Y., Degerickx, H., Vandekinderen, C., Krumer-Nevo, M., et al. (2020). Developing a poverty-aware pedagogy: from paradigm to reflexive practice in post-academic social work education. Br. J. Soc. Work 50, 1495–1512. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcaa043

Seymour, K., Skattebol, J., and Pook, B. (2020). Compounding education disengagement: COVID-19 lockdown, the digital divide and wrap-around services. J. Children's Serv. 15, 243–251. doi: 10.1108/JCS-08-2020-0049

Shonkoff, J. P., Slopen, N., and Williams, D. R. (2021). Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the impacts of racism on the foundations of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 42, 115–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940

Simpson, D., Loughran, S., Lumsden, E., Mazzocco, P., Clark, R. M., and Winterbottom, C. (2017). ‘Seen but not heard’. Practitioners work with poverty and the organising out of disadvantaged children’s voices and participation in the early years. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 25, 177–188. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2017.1288014

Siraj, I., Howard, S. J., Kingston, D., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Melhuish, E. C., and de Rosnay, M. (2019). Comparing regulatory and non-regulatory indices of early childhood education and care (ECEC) quality in the Australian early childhood sector. Aust. Educ. Res. 46, 365–383. doi: 10.1007/s13384-019-00325-3

Skattebol, J., Adamson, E., and Woodrow, C. (2016). Revisioning professionalism from the periphery. Early Years 36, 116–131. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2015.1121975

Skattebol, J., Blaxland, M., Brennan, D., Adamson, E., Purcal, C., Hill, P., et al. (2014). Families at the centre: what do low income families say about care and education for their young children? Sydney: UNSW: Social Policy Research Centre.

Skattebol, J., Saunders, P., Redmond, G., Bedford, M., and Cass, B. (2012). Making a difference: building on young people’s experiences of economic adversity. Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Spencer, N., Raman, S., O'Hare, B., and Tamburlini, G. (2019). Addressing inequities in child health and development: towards social justice. Br. Med. J. Paediatr. Open 3:e000503. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000503

Sumsion, J., Barnes, S., Cheeseman, S., Harrison, L., Kennedy, A., and Stonehouse, A. (2009). Insider perspectives on developing belonging, being & becoming: the early years learning framework for Australia. Australas. J. Early Childhood 34, 4–13. doi: 10.1177/183693910903400402

Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., and Siraj, I. (2015). Effective pre-school, primary and secondary education project (EPPSE 3-16+): how pre-school influences children and young people's attainment and developmental outcomes over time. Effective pre-school, primary and secondary education project (EPPSE 3-16+) (ucl.ac.uk) (Accessed February 23, 2023).

The Smith Family (2020). Small Steps, Big Futures Report – Community insights into preschool participation Australia. Available at: https://www.thesmithfamily.com.au/-/media/files/research/reports/small-steps-big-future-report.pdf (Accessed March 22, 2023).

Thorpe, K., Potia, A. H., Searle, B., Van Halen, O., Lakeman, N., Oakes, C., et al. (2022). Meal provision in early childhood education and care programs: association with geographic disadvantage, social disadvantage, cost, and market competition in an Australian population. Soc. Sci. Med. 312:115317. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115317

Torii, K., Fox, S., and Cloney, D. (2017). Quality is key in Early Childhood Education in Australia. Melbourne: Mitchell Institute.

Tseng, Y., Jordan, B., Borland, J., Coombs, N., Cotter, K., Guillou, M., et al. (2019). Changing the life trajectories of Australia’s Most vulnerable children, 24 months in the early years education program: assessment of the impact on children and their primary caregivers, May (No. 4). Report. Available at: https://fbe.unimelb.edu.au/data/assets/pdf_file/0003/3085770/EYERP-Report-4-web.pdf (Accessed February 22, 2023).

Urban, M., Vandenbroeck, M., Van Laere, K., Lazzari, A., and Peeters, J. (2012). Towards competent systems in early childhood education and care. Implications for policy and practice. Eur. J. Educ. 47, 508–526. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12010

Vandenbroeck, M., and Lazzari, A. (2014). Accessibility of early childhood education and care: a state of affairs. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 22, 327–335. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2014.912895

Wong, S., and Press, F. (2017). Interprofessional work in early childhood education and care services to support children with additional needs: two approaches. Aust. J. Learn. Difficulties 22, 49–56. doi: 10.1080/19404158.2017.1322994

Keywords: early childhood education, policy systems, economic disadvantage, families, partnerships

Citation: Skattebol J, Adamson E and Blaxland M (2023) Serving families who face economic and related adversities: the ‘5 As’ of effective ECEC service delivery. Front. Educ. 8:1182615. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1182615

Received: 09 March 2023; Accepted: 04 April 2023;

Published: 10 May 2023.

Edited by:

Linda Joan Harrison, Macquarie University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Andrea Nolan, Deakin University, AustraliaCopyright © 2023 Skattebol, Adamson and Blaxland. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Skattebol, ai5za2F0dGVib2xAdW5zdy5lZHUuYXU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.