94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 05 May 2023

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1175599

Introduction: Requesting is considered one of the most threatening speech acts that people tend to use politeness strategies to tone down the request and minimize the face loss of the recipient. These strategies develop over years and while children appear to produce polite speech forms at an early age, less is known about the strategies they use when they make requests in the Jordanian context. This study aims to investigate politeness strategies used by Jordanian children in requests at different age levels in relation to their gender.

Methods: The study included 80 subjects divided into two age groups, namely, six years and ten years, with an equal number of boys and girls. They met a lady puppet who had a box of gifts, and they were told to ask her politely to get the gift they wanted. Their requests were recorded and analyzed using Blum-Kulka’s politeness model to find the most common strategies the children used and whether these strategies differed with age and gender.

Results and Discussion: The study concluded that at the age of six, the concept of politeness is present in children’s linguistic competence, but the assignment of polite expressions to the proper speech act is still ill-defined. There were no significant differences in using politeness strategies according to gender. As children grow older, around the age of ten, they become more able to express politeness in requests. Girls preferred the indirect strategies while boys opted for the direct level in making requests. This study may positively help parents and schoolteachers enhance the pragmatic knowledge and linguistic politeness of children.

Human beings worldwide cannot live coherently without a given mode of communication. Therefore, they use language to exchange knowledge, beliefs, and opinions and make wishes, threats, promises, and requests (Gleason and Ratner, 1998). This emphasizes the concept of the performative function of utterances which was originated by Austin (1975) and developed further by Searle (1976) under the name of Speech Act Theory. It stipulates that language is used not only to present information but also to carry out actions. Austin (1975) divided speech acts into three categories: locutionary act, which refers to an utterance and its actual meaning, illocutionary act, which refers to the intended significance of an utterance as a socially valid verbal action; and perlocutionary act, which refers to the effect on the feelings, thoughts or actions of an utterance on the hearer. Based on this classification of speech acts, Searle (1976) further classified the illocutionary acts into representatives, which describe a state of affairs; directives which cause the hearer to take a particular action; commissives which commit the speaker to do something; expressives which express speaker’s emotional state toward the proposition; and declarations which change the reality according to the proposition of the declaration.

Requesting is an unavoidable social act that has a vital role in human communication and is the first mode of communication learned by children (Prodanovic, 2014). It is defined as “an illocutionary act whereby a speaker (requester) conveys to a hearer (requestee) that he/she wants the requestee to perform an act which is for the benefit of the speaker (Trosborg, 1995, p.187)”. This means that requests impose the requester’s wish on the requestee and restricts the latter’s freedom of action, and therefore, has been considered one of the most face-threatening speech acts (Brown and Levinson, 1987). For this reason, people usually try to formulate requests in a way that sounds more polite to the hearers by using politeness strategies to tone down the request and minimize the face loss of the recipient.

Politeness is the interactional balance that is reached to prevent encountering interaction imposition (Alakrash and Bustan, 2020). It is a way in which language is used moderately when conversing to express significant consideration for the desires and feelings of a person’s interlocutors. This is necessary to develop and uphold interpersonal relationships in order to fully be in harmony with the person’s culture and the rules of their society through appropriate behaviour. Requesting, in particular, is an area of politeness that has received significant attention and has been the focus of many studies in child language. Previous research demonstrates that children start producing polite forms at an early age (see Bates and Silvern, 1977; Read and Cherry, 1978; Wilhite, 1983; Watson-Gegeo and Gegeo, 1986; Schieffelin, 1990; Küntay et al., 2014; Almacioğlu, 2020). In fact, many studies proved that children’s production of polite speech seems to be very similar to adult speakers’ usage of utterances with appropriate levels of face-saving (see Bates, 1976; Bates and Silvern, 1977; Bock and Hornsby, 1981; Ervin-Tripp, 1982; Nippold et al., 1982).

In Arab societies, children have a distinctive mode of addressing adults (Al Qadi, 2020). While they appear to produce polite speech forms at an early age, less is known about the strategies they use when they make requests in the Jordanian context. Most studies focused on linguistic politeness in adults’ speech (see Abushihab, 2015; Al-Natour et al., 2015; Al-Khawaldeh, 2016; Kreishan, 2018; Amer et al., 2020; Badarneh, 2020; Al-Khatib, 2021; Rababah et al., 2021; Soudi and Rashid, 2021). Therefore, this study examines politeness strategies used by Jordanian children in requests at different age levels in relation to their gender. It mainly answers the following question:

What are the most common politeness strategies that Jordanian boys and girls use when they make requests at the age of six and ten?

The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 presents the politeness theory and outlines the framework used in this study. It further reviews previous studies on politeness in requests. Then, Section 3 describes the research methodology. Findings are discussed in Section 4, and they are discussed in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the conclusion and includes the implications and recommendations for future research.

Direct requests can be considered impolite. Therefore, people tend to mitigate or soften the effect of imposition by using politeness strategies that serve to avoid conflicts likely to arise during a conversation between the participants. This section discusses politeness theory and the empirical studies conducted on children’s polite forms in requests.

Politeness theory centres on the notion of face, which leads back to the sociologist Ervin Goffman who first introduced the term. According to Goffman (1967, p. 5), the concept of face is defined as “the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact.” Brown and Levinson (1987) expanded the face theory by adding that there are two faces: positive face which is associated with the participant’s desire to gain approval of others; and negative face which is associated with a member’s wish not to be imposed on by others. However, face in many verbal interactions can be threatened (Goffman, 2006). Some acts “by their very nature run contrary to the face wants of the addressee and/or the speaker” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 65). These are known as face-threatening acts (FTA), and they can threaten both the speaker’s and the hearer’s face.

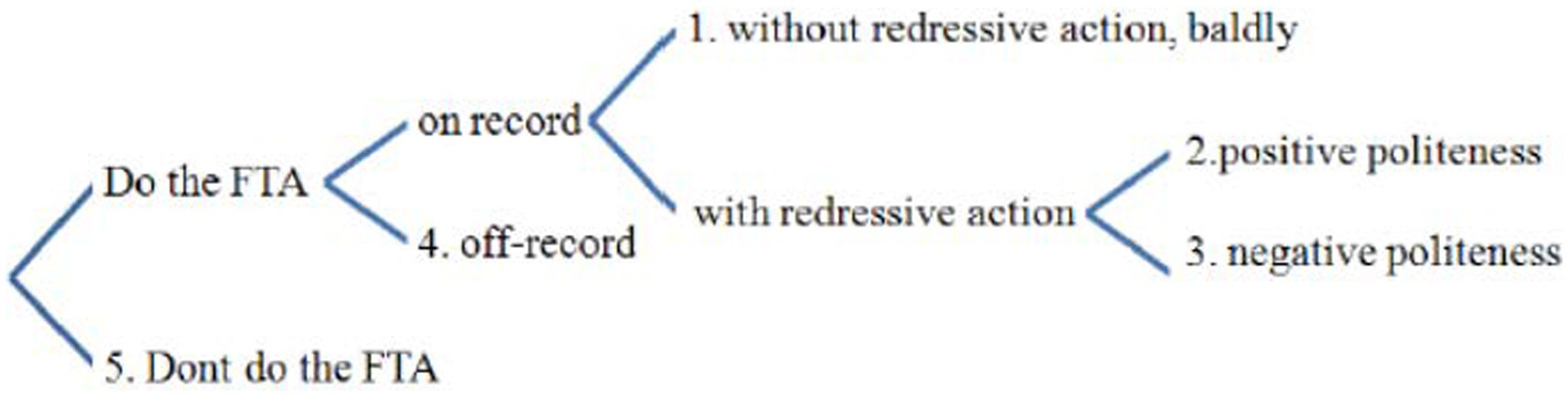

Brown and Levinson (1987) define politeness in relation to FTAs as face-saving behaviour used to minimize the threat. They outline several strategies for mitigating the face threat, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Brown and Levinson’s politeness strategies (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 74).

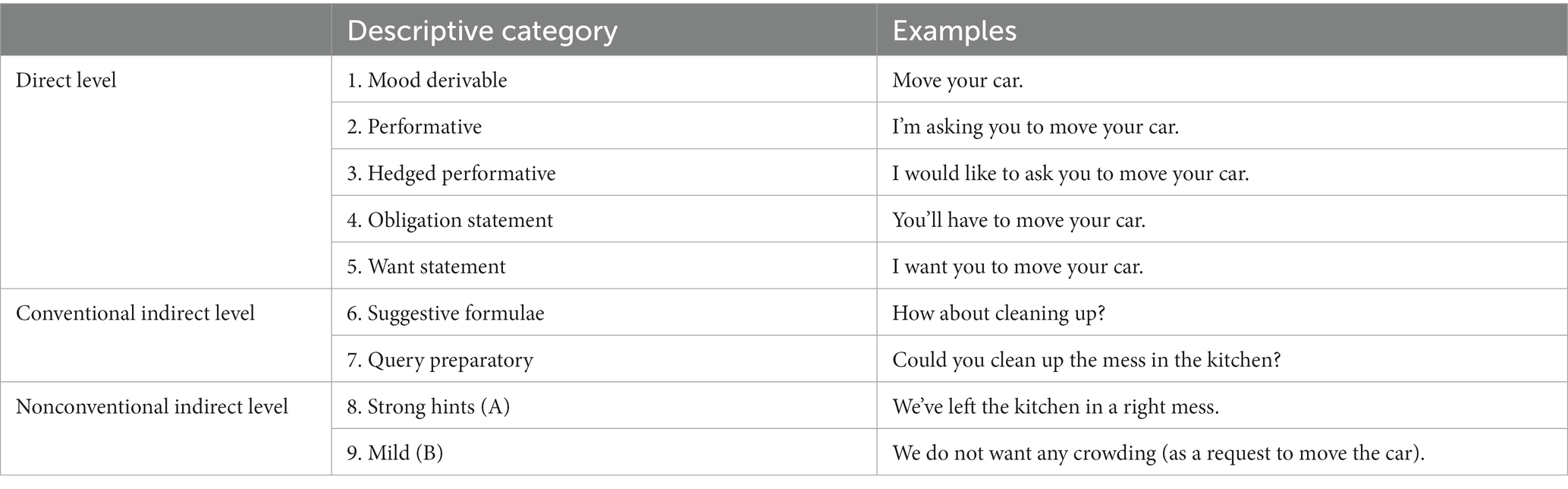

Although Brown and Levinson’s model set the basis for politeness theory, it has received a lot of criticism over the years (Watts, 2003; Kádár and Haugh, 2013). In fact, other classifications proved to be easier to operate in data analysis in empirical studies, but they remain interrelated with Brown and Levinson’s. Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (1984, p. 201) state that one can minimize the imposition on the hearer by using indirect request strategies, which sound more polite and save the hearer’s face. They describe three levels of directness of request strategies, further subdivided into nine strategies, as shown in Table 1. The first five belong to the direct level, the next two belong to the conventional indirect level, and the last two belong to the nonconventional indirect level.

Table 1. Request categories proposed by Blum-Kulka (1987, p. 133).

This study adopts Blum-Kulka’s (1987) politeness model to reveal some general characteristics of politeness patterns that Jordanian children resort to when they make requests. The reason for choosing this model is its comprehensive classification of strategies, which provides a theoretical foundation for understanding how children use language to express politeness in requests. Additionally, this model is based on empirical research and has been extensively used as a reliable tool for analyzing politeness in real-world communication.

Politeness in requests has been the main focus of many studies concerned with language development in children. Some of these studies investigated how children acquire politeness in different cultures (Bates and Silvern, 1977, with Italian children; Schieffelin, 1990, with Kaluli-speaking children; Watson-Gegeo and Gegeo, 1986, with Kwara’ae-speaking children, Wilhite, 1983, with Cakchiquel-speaking children; and Nakamura, 2002, with Japanese-speaking children; Küntay et al., 2014, with English-speaking children). These studies focused on the acquisition of politeness markers such as “thank you” and “please.” They all showed similar findings, demonstrating that children acquire politeness routines at an early age. Some other studies focused on the gradual development of children’s ability to produce and understand different politeness strategies in requests. Bates (1976) found that comprehension of polite forms precedes production. Three stages in children’s acquisition of linguistic politeness have been identified. At the first stage, which ends at the age of four, children produce direct forms such as imperative. In the second stage, which ends at about six, children produce syntactic devices but cannot mask the content of their requests. Children can produce very indirect requests in the third stage at around eight years. In the same token, Nippold et al. (1982) examined children’s understanding and producing of polite forms showing subtle differences among age groups, three years, five years, and seven years where each group consisted of the same number of boys and girls. All subjects participated in a production task and a judgment task. They found that children’s ability to produce and understand polite forms increased steadily with age. As they grow older, they become more able to produce more than one polite form in the same utterance and to use a wider variety of interrogative types when expressing politeness. Their study also revealed no differences in requests according to the children’s sex. Likewise, Axia and Baroni (1985) investigated the development of linguistic politeness in children. They conducted a study on children aged five-six, seven-eight, and nine-ten. Half of the subjects in each group were male, and the other half were female. The results showed that the capacity to react to the cost of the request in relation to the addressee’s status is acquired in an early stage and that children increase politeness in requests later at the age of seven.

Some studies examined the variety of polite forms in children’s speech. For example, the word “please” (Read and Cherry, 1978), indirect requests (Garvey, 1974; Bock and Hornsby, 1981; Ervin-Tripp, 1982), and politeness devices (Bates and Silvern, 1977) have been analyzed. In these studies, it is clear that “please” appears very early in children’s speech; indirect requests and politeness devices are used with increasing age.

A large number of studies were concerned with gender differences in children’s linguistic politeness, most of which focused on the different strategies utilized by girls and boys (Miller et al., 1986; Austin, 1987; Sachs, 1987). The subjects of these studies were mostly American, and their results showed that the girls used more mitigating strategies, whereas the boys used a more assertive style. In a similar study, Sheldon (1996) found that girls tend to use mitigators, indirectness, and even subterfuge in order to soften the blow while promoting their wishes. In the same vein, Goodwin (1998) and Cook-Gumperz and Szymanski (2001) investigated children’s linguistics politeness in the American context. They found that even though girls employ more mitigated forms in their requests than boys, they still use a more assertive, unmitigated style in mixed-sex groups. Kyratzis and Guo (2001) also analyzed Mandarin-speaking preschool children in China compared to English-speaking preschoolers in the United States. They found that American girls preferred indirect, polite conflict strategies, while Chinese girls were direct and highly assertive. Similarly, Rasti and Mehrpour (2015) investigated polite request forms in the speech of Iranian first-graders (i.e., seven-year-old children) to identify differences between male and female children. They concluded that girls favoured more indirect forms, whereas boys opted more for direct structures. On the other hand, Ladegaard (2004) conducted an empirical study of Danish children’s production of politeness in play. He found no significant differences in boys’ and girls’ use of mitigation. Both boys and girls often used an assertive, unmitigated style in their play. Likewise, Almacioğlu (2020) investigated the Turkish children’s acquisition and use of politeness in requests. The language of preschoolers between 4;3 and 5;7 years was analyzed, focusing on the possible gender and age differences or similarities in their use of polite forms. The results revealed no significant differences in boys’ and girls’ use of mitigation. They often used an assertive, unmitigated style at the same level in their play.

In the Jordanian context, Al Qadi (2020) investigated politeness strategies in children’s requests. The children were asked to respond to various situations in which they submitted a request to speak. The findings proved that the respondents used a listening perspective to express solidarity and consideration for others.

It can be said that although the literature of children’s politeness studies is rich, little attention has been paid to this linguistic phenomenon in Jordan. However, there is a stressing need to have specific knowledge about Jordanian children’s use of politeness strategies in relation to age and gender for their essential role in family and educational settings. Hence, this study investigates politeness strategies used by Jordanian children in requests focusing on the possible gender and age differences.

Eighty Jordanian Arabic-speaking school children participated in the study after their parents’ consent was affirmed by the “Parent Information and Approval Form.” The children were divided into two groups based on their age, with an equal number of boys and girls in each. The first group consisted of 40 six-year-old children, and the second group consisted of 40 ten-year-old children. This grouping is based on previous studies that investigated linguistic politeness in children and proved effective in demonstrating its gradual development (see Becker, 1986; Pedlow et al., 2004).

The study was conducted at a school targeting the aforementioned age groups. The experimenter met each group of children and explained the task to them. The task is an adaptation of Bates’s politeness task (1976, p. 296–297) in which the child requested candy from an old lady hand-puppet. In the present investigation, the children were told that they would meet a lady hand-puppet that had a collection of gifts, and she would give the children any gift they wanted if they asked her politely. In order to familiarize the children with the lady puppet, they met her before the beginning of the task. The experimenter sat on a table in a room to operate the lady puppet and displayed a box of gifts that belonged to her. The children entered the room one by one and sat opposite the lady puppet. The lady puppet was the speaker of the task with the voice of the experimenter, who was consistent in terms of the words used and the overall tone and attitude. She told the children, “معي بوكس في ألعاب حلوة، وبقدر أعطيك وحدة إذا بتطلب مني بطريقة مؤدبة” I have a box of nice gifts, and I can give you what you want if you ask me politely. The spontaneous requests produced by the children were recorded. Their requests were classified and analyzed using the framework proposed by Blum-Kulka (1987) to find the most common strategies the children used and whether these strategies differed with age and gender. It must be noted that the classified data were cross-checked by two colleagues specialized in pragmatic studies to ensure that the requests were identified correctly with the strategies and no major discrepancies were found.

As a native speaker of colloquial Arabic and being familiar with the Arab culture, the researcher could identify polite requests through different linguistic markers. The syntactic form of a sentence can be modified from an imperative أعطيني الكتاب “give me the book” into an interrogative تعطيني الكتاب؟ “can you give me the book” signalling an indirect approach in requesting. This strategy may involve incorporating a lexical item such as ممكن “is it possible”, بصير “is it possible”, لو سمحت “please”, بقدر “can I”, عادي “is it okay”. These devices are usually used to make requests more polite and less threatening. It is important to note that the stress and softened intonation accompanying the utterance also play a role in mitigating requests.

The request forms made by children are classified into categories that determine the strategies used in accordance with the proposed model, as can be shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2. Distribution of frequency and percentage of the request strategies used by six and ten-year-old boys and girls.

Table 2 and Figure 2 demonstrate the diversity of the strategies realized by children at the age of six, with the direct level being the highest in both boys and girls, making up 55% and 40%, respectively. The direct-level strategies used were mood derivable, hedged performative, and want statement. Performative and obligation statements, however, were absent in the request forms of this age group. In the conventional indirect level, only query preparatory was used by boys and girls, with 10% and 15%, respectively. The nonconventional indirect level was also utilized in the form of strong and mild hints by boys and girls, with 15% and 20% in a row. The data include statements that do not count as requests and are categorized under irrelevant forms, with 20% made by boys and 25% by girls.

Regarding the ten-year-olds, there is a decrease in the number of strategies used. The boys seem to prefer the direct level when making requests forming 65% of the overall number of the strategies they use. Hedged performative was highly used (45%), want statements (15%), and mood derivable (5%). On the other hand, only 35% of the girls used direct strategies, with hedged performative being the highest (25%). As is the case in the six-year-olds, performative and obligation statements were not among the children’s strategies. At the indirect level, only query preparatory was used by boys (35%). This also applies to the girls, but the percentage was much higher (60%).

This section discusses the findings related to the most frequently used politeness strategies among six and ten-year-old children in requests. Each age group is discussed separately with examples that do not represent the totality of requests made but only incidents of the different types of strategies used.

Table 3 includes examples of the strategies used in request expressions made by six-year-old boys and girls. It must be noted that the categories which do not have matching examples in the collected data were excluded.

As shown in Table 3, the requests made by six-year-old boys and girls were considerably varied in terms of the directness of the strategies. Mood derivable was used limitedly yet similarly by boys and girls, represented in the imperative verb أعطيني “give me,” which may be considered a form of unmitigated and assertive language. Likewise, the boys employed hedged performative using the expression لو سمحت “please” a bit more often than girls. However, for both sexes, it was mainly used as a memorized expression without being able to incorporate it into a complete sentence that expressed a request. In the girls’ data, there were some cases where the subjects used expressions such as شكرا “thank you”, عفوا “welcome”, and يسلمو “thank you” along with لو سمحت “please” to make requests. These examples are all used as polite responses when someone has asked you to do something or done you a favour but never in making requests. This demonstrates that children at this age have a good repertoire of polite expressions, but they do not use them in the right situations. More precisely, they confuse the use of such expressions with the right speech act. The reason may be that children at this age do not communicate with many people since they spend most of the time with their parents, who usually try to instill polite behaviours at an early age. This was reinforced when some children linked the use of politeness forms with their mothers, although they were not present at the time of conducting the study. There were a few requests starting with لو سمحت يا ماما “please mom” and يسلمو يا ماما “thank you mom”, which may be justified by the fact that mothers give their children instructions on how to behave politely with others. When children are given something, mothers usually ask them, “what should you say?” waiting for “thank you” as a response. However, the intimacy of relations among the family members may affect the degree of politeness they use with each other. When children are sent to school, they need to act politely with their teachers and classmates. Some children may have been enrolled in kindergartens before, but rules are not as strictly imposed as at schools. Therefore, children’s linguistic politeness may be improved at this stage. Although not focused on in this study, the roles of parents in children’s early socialization and pragmatic development were emphasized in previous studies (see Toda et al., 1990; Bornstein et al., 1992; Crago, 1992; Crago et al., 1993).

Regarding want statements, the boys and girls used the same patterns, although the former used this strategy more often. All in all, the boys’ use of direct strategies was slightly higher than the girls’, which may be due to the fact that they are generally more confident about expressing what they want. During the experiment, some girls felt shy and hesitant to make a request and used pointing at first to ask for the gift they wished to have, but they did later upon the experimenter’s insistence that they should utter a verbal request. According to Abu Nidal (2004), in the Arab world, girls are taught how to behave politely and talk quietly, while boys are subjected to a different and less set of rules.

At the conventional direct level, query preparatory was observed in the requests made by boys and girls, which are indicators of polite behaviours. They all used a lexical item such as ممكن “is it possible”, بصير “is it possible”, and عادي “is it okay” to make their requests less threatening. However, it was noted that the girls were sometimes more persuasive in that they used affectionate and praising phrases in their requests, such as “I love you” and “you are pretty.” They tended to reduce the act of threatening the hearer’s positive face by making proper compliments to the experimenter to feel good. Such expressions were not used by boys, who are generally less emotionally expressive than girls (Simon and Nath, 2004).

For the nonconventional indirect level, boys and girls used strong and mild hints to express what they wanted indirectly. Their requests centred on what they liked and what they wanted to buy. Nevertheless, the limited number of requests in this category confirms earlier findings of Bates (1976), who concluded that children at the age of six cannot mask the content of their requests.

There were many irrelevant statements produced by some children, such as بحب أشتغل “I like to work” and بحب أساعد ماما وبابا “I like to help my mom and dad”. This may indicate an aspect of how parents, in general, deal with their children. Mentioning good behaviours may be a good reason for which children deserve a gift as they are usually told that they will be rewarded if they perform a certain chore or behave well.

It can be said that the requests produced by children at age six demonstrated that they understand the general concept of politeness with no significant gender differences. This is consistent with previous findings of Nippold et al. (1982), Ladegaard (2004) and Almacioğlu (2020), where no notable difference in boys’ and girls’ use of politeness strategies was observed. In contrast, other studies (Goodwin, 1998; Cook-Gumperz and Szymanski, 2001) found that boys and girls differ in terms of their use of politeness phenomenon in that although girls employ more mitigated forms in their requests than boys, they still use a more assertive, unmitigated style in mixed-sex groups. This inconsistency in research results may be due to some cultural and contextual differences which influence the strategies boys and girls adopt in their speech.

Table 4 includes examples of the strategies used in request expressions made by ten-year-old boys and girls. It must be noted that the categories which do not have matching examples in the collected data were excluded.

As Table 4 demonstrates, there was less variation in the politeness strategies used by ten-year-old children. It also indicates that children at this age level were more able to express politeness in requests; there were no irrelevant forms in the statements they uttered, unlike six-year-olds. Requesting strategies are part of the pragmatic competence through which children can identify the relationship between the speaker and the addressee and the speaker’s aim of trying to get something from the addressee. This lends support to previous studies, which found that linguistic politeness develops with age (Bates, 1976; Nippold et al., 1982; Axia and Baroni, 1985).

Mood derivable was barely used by ten-year-old children; only one request was reported by a boy and another by a girl. There was a difference in the number of requests made using hedged performative between boys and girls. It is remarkably the strategy that was used by most boys. Although it is a direct strategy, there was a consistent pattern in the way boys employed it in their requests; they all used the lexical politeness marker لو سمحت “Please” to mitigate the illocutionary force of their requests. Girls used the same pattern as well, but to a lesser extent. Want statements were also used more by boys. All in all, it can be said that most boys preferred direct strategies to make requests. This result goes in line with Miller et al. (1986), Austin (1987), Sachs (1987), and Sheldon (1996) who found that girls prefer mitigating strategies, whereas the boys use a more assertive style.

At the conventional direct level, only query preparatory strategy was used by the children in the form of the interrogative structure stating with conventions of means of ability, permission, willingness, and possibility such as ممكن “is it possible”, بصير “is it possible”, بقدر “can I”, and عادي “is it okay”. Both boys and girls used the same patterns, but they were much more prevalent in the girls’ requests. However, it was noticed that most girls used this strategy with the lexical marker لو سمحت “Please”, making their requests more polite. When it comes to boys, not a single subject from the study sample used لو سمحت “Please” with query preparatory. This result accords with the findings of Rasti and Mehrpour (2015) who found that girls preferred indirectness in forming requests.

At the nonconventional indirect level, hints, whether mild or strong, did not appear at all or appeared only once by a girl. The reason for this is that the children were required to ask the experimenter for the toy they wanted. However, the absence of this strategy in children’s requests at this age may not apply to all life situations. They may resort to this strategy in unplanned settings depending on what they want and who the addressee is.

Children are all persistent in getting what they want, but the study proves that girls are more successful in using politeness strategies at this age level.

This study aimed at identifying polite request forms in the speech of Jordanian children at two age levels (six and ten) and finding gender-based differences, if any, between the speech of boys and girls. It was revealed that at the age of six, the concept of politeness is present in children’s linguistic competence, but the assignment of polite expressions to the proper speech act is still ill-defined. The study also found that there are no significant differences in using politeness strategies according to gender at this age level. As children grow older, around the age of ten, they become more able to express politeness in requests. The strategy that seems to be pervasive among Jordanian children is using the lexical politeness marker لو سمحت “Please”. However, girls use it with an interrogative sentence to mitigate the illocutionary force of their requests whereas boys use it with an imperative. This indicates that girls prefer indirect strategies while boys opt for the direct level.

This study may positively help parents and schoolteachers enhance the pragmatic knowledge and linguistic politeness of children. As Politzer (1980) stated, pragmatic competence is not created automatically; it rather requires education, starting from the early stages of language learning. Researchers interested in politeness universal principles can also use the findings of this study to compare and contrast young speakers of Jordanian Arabic with other languages.

In light of the outcomes of this investigation, further studies are recommended to include more participants of different age levels in various geographical areas in Jordan. Moreover, more studies can be conducted to investigate different factors that influence the choice of strategies, such as the addressee and the setting.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author is grateful to the Middle East University, Amman, Jordan for the financial support granted to this research.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abu Nidal, N. (2004). Rebellion of A Female in the Novels of Arab Women and A Bibliography of Arab Feminist Novels (1885–2005). Beirut: The Arab Publishing and Studies.

Abushihab, I. M. (2015). Contrastive analysis of politeness in Jordanian Arabic and Turkish. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 5:2017. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0510.06

Alakrash, H. M., and Bustan, E. S. (2020). Politeness strategies employed by Arab EFL and Malaysian ESL students in making request. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 10, 10–20. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i6/7257

Al-Khatib, M. A. (2021). (Im)politeness in intercultural email communication between people of different cultural backgrounds: a case study of Jordan and the USA. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 50, 409–430. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2021.1913213

Al-Khawaldeh, N. (2016). A pragmatic cross-cultural study of complaints expressions in Jordan and England. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 5, 197–207. doi: 10.7575//aiac.ijalel.v.5n.5p.197

Almacioğlu, G. (2020). Politeness in young children’s (between 4; 3-5; 7) speech in Turkish: age and gender. Edebiyat Derg. 17, 1–24.

Al-Natour, M. M., Maros, M., and Ismail, K. (2015). Core request strategies among Jordanian students in an academic setting. Arab World Engl. J. 6, 251–266. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol6no1.20

Al Qadi, M. J. (2020). The use of polite request among Jordanian children. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 17, 1934–1946.

Amer, F., Buragohain, D., and Suryani, I. (2020). Politeness strategies in making requests in Jordanian call-centre interactions. Educ. Linguist. Res. 6, 69–86. doi: 10.5296/elr.v6i1.16283

Austin, J. P. (1987). The dark side of politeness: A pragmatic analysis of non-cooperative communication. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Canterbury, Chrisrtchurch, New Zealand). Retrieved from https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/1041

Axia, G., and Baroni, M. R. (1985). Linguistic politeness at different age levels. Child Dev. 56, 918–927. doi: 10.2307/1130104

Badarneh, M. A. (2020). “Formulaic expressions of politeness in Jordanian Arabic social interactions,” in Formulaic Language and New Data: Theoretical and Methodological Implications. eds. E. Piirainen, N. Filatkina, S. Stumpf, and C. Pfeiffer (Berlin: De Gruyter), 151–170.

Bates, E., and Silvern, L. (1977). Social adjustment and politeness in preschoolers. J. Commun. 27, 104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01834.x

Becker, J. A. (1986). Bossy and nice requests: children’s production and interpretation. Merrill-Palmer Q. 1982, 393–413.

Blum-Kulka, S. (1987). Indirectness and politeness in requests: same or different? J. Pragmat. 11, 131–146. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(87)90192-5

Blum-Kulka, S., and Olshtain, E. (1984). Requests and apologies: a cross-cultural study of speech act realization patterns (CCSARP). Appl. Linguist. 5, 196–213. doi: 10.1093/applin/5.3.196

Bock, J. K., and Hornsby, M. E. (1981). The development of directives: How chidren ask and tell. J. Child Lang. 8, 151–163. doi: 10.1017/S030500090000307X

Bornstein, M., Tal, J., Rahn, C., Galperín, C., Lamour, M., Ogino, M., et al. (1992). Functional analysis of the contents of maternal speech to infants of 5 and 13 months in four cultures: Argentina, France, Japan, and the United States. Dev. Psychol. 28, 593–603. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.4.593

Brown, P., and Levinson, S.C. (1987). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cook-Gumperz, J., and Szymanski, M. (2001). Classroom “families”: cooperating or competing girls’ and boys’ interactional styles in a bilingual classroom. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 34, 107–130. doi: 10.1207/S15327973RLSI3401_5

Ervin-Tripp, S. (1982). “Ask and it shall be given you: children’s requests” in Georgetown Roundtable on Language and Linguistics 1982. ed. H. Byrnes (Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press), 235–245.

Garvey, C. (1974). Requests and responses in children’s speech. J. Child Lang. 2, 41–63. doi: 10.1017/S030500090000088X

Gleason, J. B., and Ratner, N. B. (1998). Psycholinguistics. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face to Face Behavior. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (2006). “On facework: an analysis of ritual elements in social interaction” in The Discourse Reader. eds. A. Jaworski and N. Coupland (New York, NY: Routledge), 299–310.

Goodwin, M. H. (1998). “Games of stance: conflict and footing in hopscotch” in Kids’ Talk: Strategic Language Use in Later Childhood. eds. S. Hoype and C. T. Adger (New York: Oxford University Press), 23–46.

Crago, M. B. (1992). Communicative interaction and second language acquisition: an inuit example. TESOL Q. 26, 487–505. doi: 10.2307/3587175

Crago, M. B., Annahatak, B., and Ningiuruvik, L. (1993). Changing patterns of language socialization in inuit homes. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 24, 205–223. doi: 10.1525/aeq.1993.24.3.05x0968f

Kreishan, L. (2018). Politeness and speech acts of refusal and complaint among Jordanian undergraduate students. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 7, 68–76. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.4p.68

Kyratzis, A., and Guo, J. (2001). Preschool girls’ and boys’ verbal strategies in the United States and China. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 34, 45–74. doi: 10.1207/S15327973RLSI3401_3

Küntay, A. C., Nakamura, K., and Şen, B. A. (2014). “Crosslinguistic and crosscultural approaches to pragmatic development” in Pragmatic Development in First Language Acquisition. ed. D. Matthews (USA: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 317–342.

Ladegaard, H. J. (2004). Politeness in young children’s speech: context, peer group influence and pragmatic competence. J. Pragmat. 36, 2003–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2003.11.008

Miller, P., Danaher, D., and Forbes, D. (1986). Sex-related strategies for coping with interpersonal conflict in children aged five and seven. Dev. Psychol. 22, 543–548. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.22.4.543

Nakamura, K. (2002). “Polite language usage in mother-infant interactions: a look at 23 language socialization” in Studies in Language Sciences II. eds. Y. Shirai, H. Kobayashi, S. Miyata, K. Nakamura, T. Ogura, and H. Sirai (Tokyo: Kurosio), 175–191.

Nippold, M., Leonard, L., and Anastopoulos, A. (1982). Development in the use and understanding of polite forms in children. J. Speech Hear. Res. 25, 193–202. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2502.193

Pedlow, R., Sanson, A., and Wales, R. (2004). Children’s production and comprehension of politeness in requests: relationships to behavioural adjustment, temperament and empathy. First Lang. 24, 347–367. doi: 10.1177/0142723704046188

Politzer, R. L. (1980). Requesting in elementary school classrooms. TESOL Q. 14, 165–174. doi: 10.2307/3586311

Prodanovic, M. M. (2014). The delicate mechanism of politeness as a strong soft skill. IUP J. Soft Skills 8, 7–19.

Rababah, M., Al Zoubi, S., Al Masri, M., and Al-Abdulrazaq, M. (2021). Politeness strategies in hotel service encounters in Jordan: giving directives. Arts Fac. J. 18, 319–340. doi: 10.51405/18.1.12

Rasti, A., and Mehrpour, S. (2015). Use of polite request forms by Iranian first-graders: does gender make a difference? J. Child Lang. Acquis. Dev. 3, 64–69.

Read, B. K., and Cherry, L. J. (1978). Preschool children’s production of directive forms. Discourse Process. 1, 233–245. doi: 10.1080/01638537809544438

Sachs, L. (1987). “Preschool boys’ and girls’ language use in pretend play” in Language, Gender and Sex in Comparative Perspective. eds. S. U. Philips, S. Steele, and C. Tanz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 178–188.

Schieffelin, B. B. (1990). The Give and Take of Everyday Life: Language, Socialization of Kaluli Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. R. (1976). A classification of illocutionary acts. Lang. Soc. 5, 1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500006837

Sheldon, A. (1996). You can be the baby brother, but you aren’t born yet: preschool girls’ negotiation for power and access in pretend play. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 29, 57–80. doi: 10.1207/s15327973rlsi2901_4

Simon, R. W., and Nath, L. E. (2004). Gender and emotion in the United States: do men and women differ in self reports of feelings and expressive behavior? Am. J. Sociol. 109, 1137–1176. doi: 10.1086/382111

Soudi, L. A., and Rashid, R. A. (2021). Reversal politeology: the interchangeable use of im/politeness in Jordan. Dirasat: Educ. Sci. 48, 571–579.

Watson-Gegeo, K. A., and Gegeo, D. W. (1986). “The social world of Kwara’ae children: Acquisition of language and values,” in Children’s Worlds and Children’s Language. eds. J. Cook-Gumperz, W. Corsaro, and J. Streeck (Berlin: De Gruyter), 109–128.

Wilhite, M. (1983). Children’s acquisition of language routines: the end-of-meal routine in Cakchiquel. Lang. Soc. 12, 47–64. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500009581

Toda, S., Fogel, A., and Kawai, M. (1990). Maternal speech to three-month-old infants in the United States and Japan. J. Child Lang. 17, 279–294. doi: 10.1017/S0305000900013775

Keywords: politeness, school children, age, gender, request, speech act

Citation: Al-Abbas LS (2023) Politeness strategies used by children in requests in relation to age and gender: a case study of Jordanian elementary school students. Front. Educ. 8:1175599. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1175599

Received: 27 February 2023; Accepted: 03 April 2023;

Published: 05 May 2023.

Edited by:

Hadeel A. Saed, Applied Science Private University, JordanReviewed by:

Mohammad Alqatawna, King Faisal University, Saudi ArabiaCopyright © 2023 Al-Abbas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linda S. Al-Abbas, bGFsYWJiYXNAbWV1LmVkdS5qbw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.