94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Educ., 02 November 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1175457

This article is part of the Research TopicEmancipatory Inquiry in Educational Research: Models and Methods for Transformational LearningView all 6 articles

This article explores an analytical, reflexive, epistemological, and liberatory research approach I call senseMaking. This article draws upon data from a larger narrative study of participants who work(ed) and/or learn(ed) in self-contained special educational environments in New York City. I use creative writing and quilting as examples of senseMaking tools to complicate and question the deficit-laden narratives and research that currently inform decision making about special education and traditional methods of educational research.

If a place is willing to tell a different story

—a more honest story—

It would begin to see a different set of people visiting (Smith, 2021, p. 124)

The story I was told fourteen years ago: this is a school for kids who have been kicked out of everywhere else. This is their last chance for a high school diploma.

The story that I told myself fourteen years ago: This is an opportunity to be creative and make a classroom space with kids so that they will want to come and learn.

The story that I heard from former students during this research: It was their last chance to earn a high school diploma because of the stories that had been told about them.

The story that the former students want to tell: We all began school with desires—to learn, be seen, be safe, to belong and be understood.

For months now, I have been sitting with the concept of truth and the act of telling as I reflect on the stories that were shared with me during the course of my research. I have hundreds of pages of transcripts, organized in binders, just waiting for me to create space and time to crack them open. I look at them, stacked on a shelf above my desk and reflect on the power and responsibility that I have in shaping the narrative that you are now reading. In an effort to reduce my exposure to COVID-19, I commute by bicycle from my home in Brooklyn to a public high school in Manhattan, passing the Brooklyn Museum on my way. In May of 2021, the walls alongside the main plaza of the museum became the site of an installation piece by Nick Cave entitled “Truth Be Told.” The installation consisted of the words “Truth Be Told” “stretch[ed] across different planes of the Museum’s lower façade, commenting on how words can be warped and distorted by those in power” (Brooklyn Museum, 2021, para 1). Cave created the piece in response to the police murder of George Floyd, with the intention of provoking viewers into questioning “where truth does and does not reside” (Brooklyn Museum, 2021, para 1). One early morning as I paused at the traffic light, I glanced at the museum and saw a huddled shape under a blanket on the stairs, right under the words “Truth Be Told.” A person had made a museum step their bed for the night. I was struck by the juxtaposition of this massive cultural institution, which was actively encouraging passersby to engage in questioning the meaning of “truth,” and the physical representation of the truth that lay in the body of the person curled under the blanket on the granite step. Seeing the person sleeping on the stairs provoked me to dig deeply into “the truth,” and to understand that ultimately, when there is no space for people to speak their truths, we lose sight of our collective humanity and responsibilities to each other and to the planet.

The focus of this article is on the epistemological, reflexive, analytical and liberatory ways in which I employed a research approach that I call senseMaking. senseMaking is not a particular set of activities or tools. It is an approach I use to make space within research in order to develop deeper ways of listening to participants and myself. It is a way to understand and make meaning of and from the experiences and knowledges of participants and my own experiences and knowledges as a researcher. The ways in which I “Make” space are varied, anything from building to producing short films from quilting to poetry. This article is organized into five different sections: Research Context, Framing, senseMaking 1-poetry, senseMaking 2-quilt, and Conclusions and Continued Wonderings. In senseMaking 1-poetry, I will specifically focus on data drawn from one former student participant, Ace1 to illustrate senseMaking through poetry as analytical, epistemological and liberatory tool that I used to listen and deeply hear. In senseMaking 2-quilt, you will read about senseMaking through quilting as reflexive, epistemological and liberatory tool that I use to bring my research to a close.

This study took place in the summer months that followed the COVID-19 shutdown at the height of the racial uprisings in response to racial violence and police brutality and specifically the murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd. For many, including the participants of this study, the syndemics of global COVID-19, police brutality, and racial violence highlighted the living impact of systemic racial injustices in education, health, food insecurity, safety, housing and disability. The pandemic laid bare the tensions between storied American, rugged-individualist narratives and impassioned acts of collective care. When the friction between individual and collective experiences is broken, a space is opened in which it is possible to feel, see, and hear how systems, structures, and institutions intersect, collide, and bend to reveal structures of inequity. It is compelling to me that my participants each have unique experiences, but when viewed collectively, their shared narratives highlight the sharp disparities, contradicting logics, and moments of joy in self-contained settings. While this project was not imagined during the pandemic, it was re-imagined to capture the further complexities of educational containment within a time of global containment.

This article draws from data and methods used in a larger narrative study of 14 educational professionals and nine former students2 who work(ed) and/or learn(ed) in self-contained special education environments in New York City. During the study I met with each participant, via Zoom, for three interview sessions and a final member-check session (which occurred 2–3 months after the initial data collection). They were generous in sharing their time and experiences with the hopes that their stories would be shared with others. The experiences of the participants reflect the policies, culture, and populations of New York City but the truth is that stories like those shared here exist throughout the United States and beyond. New York’s system for placing students in what is considered their “appropriate” setting is based on federal legislation as interpreted by local and state officials. New York City’s story is compelling as there has been a decades-long, near constant push for cultural and policy changes regarding desegregation, and yet the primary system that maintains racial segregation is special education (Ferri and Connor, 2005).

One third of the nearly 200,000 students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) in New York City attend school in a “special class” separate from their general education peers. The New York City Department of Education defines “special class” as a location in which “services are provided in a self-contained classroom. All of the children in the class have IEPs with needs that cannot be met in a general education classroom. They are taught by special education teachers who provide specialized instruction” (New York City Department of Education, 2021). To preserve the anonymity of the participants in the study, I did not ask to be provided with the specific locations of the self-contained educational environments. Each of the former students identified that they had attended District 75 programming at some point during their K-12 education. District 75 is a non-geographical self-contained district that has programs and schools throughout the city. It operates separately from the other 32 districts that make up the New York City public school system. Within the continuum of special education settings available in New York City Public schools, District 75 is the most restrictive school-based setting. The settings that come after District 75 are day and residential placements and home and hospital instruction.

This research was guided by two central and two supporting questions, to better inform pedagogical practices and educational policies:

1) How do former students labeled with an educational disability navigate and make meaning of their learning environments?

a. What discourses do the former students embrace, twist, and/or reject as a means to make meaning of their educational experiences (e.g., deservingness, meritocracy, ability and or disability, containments, etc.)?

2) How do educational professionals working in self-contained special education settings make meaning of their work-related experiences and decisions?

a. What discourses do the educational professionals embrace, twist, and/or reject as a means to make meaning of their professional experiences in self-contained settings (e.g., deservingness, meritocracy, ability and/or disability, special education, purpose of education, etc.)?

The purpose of the larger research project is to deepen societal understanding of the complex and everyday impact of educational discourses like deservingness, disability, trauma, behavior, special education, and the school-to-prison nexus (Meiners, 2007) specifically as it relates to educators and young people who work and learn in self-contained/segregated environments. This group of individuals who work and learn in isolated environments is largely stigmatized in special education literature. The field of special education is flooded with research that persistently posits “deficit-based understandings of difference, overrepresentation in negative outcomes, and [a] limited range of research methodologies” (Annamma et al., 2018, p. 48).

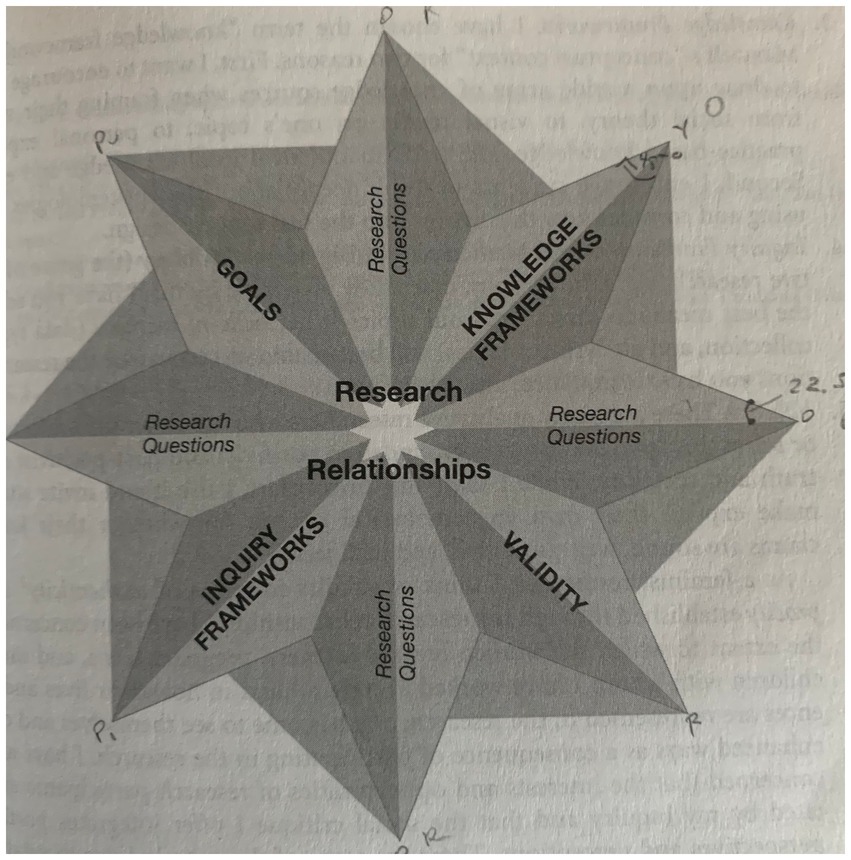

senseMaking seeks to counter and complicate traditional special education research methods by incorporating Making into the research process. I used it to make space for dignity and voice through the centering of individual and collective experiences of the researcher and research participants. Over the course of researching and writing, my process evolved as I moved through different ways of looking and listening to the participants. Initially, I began with traditional analytical tools: transcription, discourse analysis, narrative analysis, and visual discourse analysis. At a certain point, however, I got stuck. The words were just swirling on the page, and I was lost. Of all of the tools I used to help me find my way, the most helpful was my research design. You will read later in “senseMaking 2-quilt” about the influence sociologist, Dr. Wendy Luttrell’s “reflexive-origami North Star research design” (Luttrell, 2010, p. 161) had on my design process. Her North Star design served as a guide back from the depths of the data as it required me to return to the heart of my project, my relationship to the participants and to their stories and their truths.

My research was conducted within a community that I know intimately and interacted with on a regular basis. Therefore, my concern for ethics was (and still is) paramount. In her work on autoethnographic research methods, Dr. Carolyn Ellis explains that:

“Relational ethics recognizes and values mutual respect, dignity, and connectedness between researcher and researched, and between researchers and the communities in which they live and work … relational ethics requires researchers to act from our hearts and minds, to acknowledge our interpersonal bonds to others, and to initiate and maintain conversations…” (Ellis, 2007, p. 2).

I knew I had an ethical responsibility to use methods that would liberate academic space for the participants to talk back to dominant narratives in the field. For example, the idea that self-contained educational settings are an “educational imperative” (Kauffman et al., 2005) for meeting the needs of students with disabilities was challenged by Ace, who shared that he felt he had been robbed of opportunities because of his school placement. Theoretically, Disability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) provided me with a framework for listening to/for counter-narratives of former students’ and educators’ experiences in their schooling environments. DisCrit reveals “the shifting boundary between normal and abnormal, between ability and disability, and seeks to question ways in which race contributes to one being positioned on either side of the line” (Annamma et al., 2013, p. 10). The space between the “shifting boundary” is where counter-narratives lie. I think of counter-narratives not just as the words, images, and actions of the participants in this study, but also as the spaces of silence- as the pauses, as the “I do not knows” or “I do not remembers,” as the empty chairs in classrooms. Foucault (1965) suggests that an “archaeology of silence” reveals that the construction of “madness” or of “the other” relies upon the silencing of those being labeled (p. xi). There is also silence or absence left behind in the spaces that the participants have been pushed out of, removed from, or have been denied access to. The participants in this study had all been labeled by the educational system either as having an educational disability or as working within self-contained special education settings. They all have experienced silencing and have left behind silence in their wake.

Much of my career as a high school special education teacher has been guided by students expressing their desires to do things that matter. Many of my students were dissatisfied with traditionally rote methods of reading and writing instruction. As someone who learns best by doing, I too am dissatisfied with teaching and researching in ways that feel restrictive and bound to the page. I needed to do something, to liberate the knowledges being shared and created in this research and, to make things that connected how I was listening to what I was hearing- which reflected the hurts, hopes and desires of the participants and myself. That is how senseMaking became a part of my process. DisCrit is one of the theoretical frameworks that I use to think and listen, and senseMaking is my reflexive, analytical and epistemological approach for processing what and how I hear. senseMaking is rooted in my experiences as an artist, maker, and special education teacher.

Work that aligns itself with DisCrit must be used as a form of “academic activism” to explicitly “talk back” to dominant narratives (Connor et al., 2016, p. 22). For me, there is an irony (and a liberatory power) in the act of “talking back” to a system that has punished and excluded generations of students for acts of resistance, which could be considered “talking back” to systems of oppression. In her essay “Talking Back,” Hooks (1986) describes the risks and necessities in talking back, and wonders about the silences and the silenced. In the essay, Hooks recalls her parents explaining their need to break her spirit, which calls to mind Bettina Love’s use of the concept of “spirit murdering” to describe “denial of inclusion, protection, safety, nurturance, and acceptance because of fixed, yet fluid and moldable structures of racism” in the context of school (Love, 2019). If we think about traditional special education research methods as tools to silence and exclude those that ‘talk back’, the work of senseMaking is to make space within research for participants and researchers to ‘talk back’ and truth tell.

For as long as I can remember, I have been a maker of things. I grew up in a household surrounded by makers: my parents and sister were always making things—physical things like clothing, woodworking projects, musical things, and things with words, like articles, sermons and poems. Often things were made out of necessity, like weather-appropriate clothing and tools to make household chores easier, and sometimes things were made for pure joy, like toys, swings and beautiful things to look at. As a result, making has always been the way that I make sense of myself and of the world, as well as the way that I express my ideas to others. Thus, it was natural for me to incorporate senseMaking at all the stages of my research process, from design to final products.

One particularly slow-going afternoon, I pulled a table into the middle of my living room and laid out my stacks of coded transcripts. I proceeded to cut them apart and paint on them. Cutting and assembling the strips gave me a way to see and hear the words of the narrative segments in a new way. This is how the poem “Ace,” which you will read in a later section, came to take its form and organization. I did not set out to write a poem, but the precedent for thinking about the power of the poetic form in research was highlighted for me in the article, “Michael’s Story: ‘I get into so much trouble just by walking’: Narrative Knowing and Life at the Intersections of Learning Disability, Race and Class” by DisCrit scholar (and co-founder) Dr. David Connor. I had read his article very early on in graduate school, and it was one that I returned to repeatedly for guidance as I entered the research process. Connor (2006) writes, “by using the poetic form, I am not making claim to traditional ‘truth telling’ but rather see the data as an interpretive activity” (p. 155). The act of cutting up the lines allowed me to interpret what Ace was saying as an act of his talking back, his truth telling, beginning with this section that I pulled away from other parts of his interview:

Once I felt that button was pushed a million times—.

I started off with a chair, the dictionary and then the little table.

I am literally attacking the person that’s bothering me.

I heard so much rhythm in his narrative that I was able to organize his words in a way that closely resembled the way that he speaks. Placing the strips together enabled me to spatially represent the narrative segments in the way that I was hearing them, which, for me, was not possible when reading his words through the transcripts.

You can call me Ace.

one.

I remember tearing down classrooms.

Telling the teacher, I was being bothered,

The teacher not doing anything about it.

Once I felt that button was pushed a million times—

I started off with a chair, the dictionary and then the little table.

I am literally attacking the person that’s bothering me.

It comes down to me getting suspended.

When I left that school, we would have the autistic kids with us.

That’s really how I knew I was in a different school setting.

two.

It was still the same, honestly. The fights did not slow down until about fourth grade—

Where English had started to make a difference.

I was bullied for being the only kid on a non-uniform day that wore a uniform.

three.

They wanted to see how I would do in a different setting.

It was on the West Side next to

the precinct.

That’s when I realized what the

difference

between

mainstream

and

special ed

was.

I remember that IEP meeting.

I remember them telling me they wanted to see

how

I would fare

in a bigger class size.

I wanted to give it a try because

I wanted to see what the difference would be

I wanted to get away from having a 1-1 (paraprofessional) …

pretty much feeling babied all the time or monitored 24/7.

four.

I did have support but

it wasn’t the same as the 1-1

In the new school that person was there to help everybody.

I did not finish the school year … I got into a fight … and that’s when

I got back to special ed … I was mad.

Like, I finally got out of here, finally got a chance to go

back to gen pop and I screwed it up … It was just one chance …

No one ever represented the idea of returning to mainstream.

five.

I remember getting into [Urban Construction High] …

I knew early on I was good with my hands …

my paperwork got jammed up …

I did get accepted

but nobody notified me … so the conversation I had with [administration] is that

because of behavioral problems, they wanted me to start at [Hell’s Kitchen High] …

It wasn’t something I wanted to do.

I had stepped out of a special ed setting and

I realized that’s where my full potential could be met …

I felt like I could learn more in a regular ed setting.

six.

I felt like I got cheated out of my chance to get a better education.

I just kept going cuz

I did not know how the process worked.

Aggravated, everyday aggravated—everyday.

It did not matter whether I was getting the education that I wanted …

I was in an environment that I did not want to be in …

I fought so hard from the time that I got kick[ed] out of general ed

to get back into general ed

to obtain a general education diploma.

seven.

I do not know what made me keep going.

I did not really have an option. I did not go, I’d get my ass whooped by

my father or grandmother …

Dropping out wasn’t an option

Because I just wanted to be on my own …

I had the mindset, at an early age

Without the proper education and a proper high school diploma,

I would not be about to survive

To take care of myself

Get a decent paying job, right?

eight.

My diploma would wibe the equivalent of a black belt in its original form. So, the origin of a black belt is that it changed color

through

blood,

sweat

and tears

over the course

of years.

You do not obtain a black belt, your white belt turns black … and that.

is what the high school experience is:

blood, sweat, tears … literally.

I was put unconscious by this one dude in a sleeper hold;

fought my way through the experience of high school.

The tests that I did not think I would pass, the seats …

That’s what my diploma means to me.

There’s not too many people in my family

that can say they have their high school diploma—

so to me, it’s breaking the cycle …

the diploma,

I keep it in the yearbook,

I keep that in an envelope,

And I keep that in a bin.

It is not going nowhere. I have all my awards and certificates … and a portfolio

Because they show the progress that I’ve made over the years from

Literally not being able to form sentences

To being the man I am today.

Every time I interviewed Ace, he was in his car—not driving, but leaned back in the driver’s seat, window cracked. He was vigilant about the world passing him by as we talked. Some of my favorite moments of relistening to our conversations were during the pauses. I could hear the sounds of kids playing nearby. Ace would often greet people, offering a nod or a soft “hey there” and in return, indistinct murmurs of hello would float back through the window. He was simultaneously at ease and on-edge during our conversations, his mood shifting with his story and the world outside of his car window. Over the course of three interviews, Ace constructed a clear, chronological narrative about his schooling experiences. He seamlessly moved our conversation from early elementary school, to middle school, to high school. His narrative seemingly centered around the theme of fighting, both literally and figuratively. At times during his telling, it was as though Ace was still battling with his educational experiences. His narrative began with a memory of an incident in an elementary school classroom, after he felt like “that button was pushed a million times,” and ends with an explanation of what his diploma means to him—“the equivalent of a black belt in its original form.” Ace has a long history of training in martial arts, and I understand how sacred this metaphor is to him—he really means it. He is specific with his language: “you do not obtain a black belt, your white belt turns black.” Obtain, meaning “to get”- in other words, no one just gets a black belt; it is something that is earned. Ace understood, because of his family, that a high school diploma is also not something that a person obtains but rather something that someone deserves once they have completed the requirements. Ace explained that he felt “cheated” out of his opportunity to attend a general education high school program, that he deserved the opportunity to attend Urban Construction High but because of a paperwork issue was denied the chance to realize his “full potential.” His blood, sweat and tears are part of how he makes sense of his education in self-contained settings.

After listening to his interviews several times, I could hear a distinct rhythm in the way that he told his story. I printed a transcript of Ace’s narrative and then cut out each line. I then arranged his narrative into stanzas, breaking apart his sentences to reflect the way that he naturally speaks. When we met for our final session, I asked him if he had gotten a chance to look at the way that I had represented his interview. He said that he had not had time but asked if I would read it to him. He sat back in his seat, his head against the headrest, eyes closed, listening. When I finished reading, he was quiet—all I could hear was street noise in the background. Then, he let out a laugh and said in a surprised voice, “I said all that?” I’ve been holding on to a lot.” When I asked him about the arrangement he remarked, “it made sense because that is how I sound when I talk and that is what happened to me, that’s my story, at least that’s part of it.”

Ace’s story is unique to Ace but is also representative of many of the stories that I was told by the nine former students. Their individual stories were so personal and so emotional, yet they collectively spoke back to the discourses of special education that pathologize, criminalize and exclude students who do not fit neatly into, or who challenge, the “grammar of schooling” (Tyack, 1974, p. 28). When students are reduced to labels, their humanity is lost to the structure. Labels silence. The physical removal of students also creates a silence in their absence. Participants engaged in an “archaeology of silence” by telling their stories, by telling their truths. In taking up space to be heard and make meaning, they humanized themselves. This is a form of liberation. When I shared the poem with Ace, he said, “I said all that? I’ve been holding on to a lot!” He meant that through the act of truth telling and senseMaking he was no longer “holding on” to some of those thoughts, words and experiences in the same way. His voice raised in exclamation at the end—as though shedding some of the weight he carries with him regarding his educational experiences. Ace was not alone in that response to his words. I used my final session with each of the participants as a member-check and we reviewed what they had said, and what I had written so far. During those sessions, it was not uncommon for the participants to express relief, —I am so glad I said that—or exhale a deep breath. And now that the research has concluded, the participants have continued to reach out and inquire about where their “stories are.” During this process I felt like I was, as Hooks (1986) teaches, “bear[ing] witness to the primacy of struggle in any situation of domination, to the strength and power that emerges from sustained resistance, and the profound conviction that these forces can be healing, can protect us from dehumanization and despair” (p.126). My personal experience of each member-check session included a cycle of anxiety about my position of power as a researcher, vulnerability about sharing my interpretations and expressions of the experiences of the participants, and relief in the knowledge of a shared moment of connection, healing and hope.

Sitting at the table, I slowly pull the fabric apart. I slide the seam ripper into the space I created with my fingers and carefully pop each of the stitches holding the fabric together. As I break the threads, I think about the tools and materials in my hands and the generations of knowledges that guide my fingers through this process.

I kept my position as a high school special education teacher for most of my graduate studies. This meant that often what I was studying, learning and thinking about in my Urban Education program was also happening, in real time, at my work. During lunch, it was not unusual for me to work on a paper or read something for class to the soundtrack of students running, laughing and sometimes screaming, as well as all of the other noises one associates with a lively group of teenagers. COVID-19 silenced this soundtrack and brought my process to a grinding halt. My deadline was looming and yet there were no words that could bring my research to a close. Initially, my project was to conclude with a multi-sensory installation in which viewers would have been able to walk through a space while seeing and hearing the experiences and words of the participants. Because of COVID-19, I was forced into a position where I had to conceive of writing my conclusion in a more traditional way. This felt antithetical to the relationships I had with my participants and to my research process. And so, I turned to another approach in senseMaking, this time a reflexive, epistemological and (I was hoping) liberatory process—quilting. While I had never quilted before, I was raised in a community that has a strong making and quilting culture. I can remember sitting under the quilting frame while the ladies from my church moved their needles in and out, gossiping, laughing and sometimes crying.

In the home where I spent my elementary and middle school-aged years, my mother had her sewing machine set up in the basement, not far from her desk, my workbench, and my father’s workbench. I spent a lot of time in the basement playing, experimenting, and reading as my parents worked on their projects or while my mother was researching and writing her dissertation. I observed their ways of making. My father would organize all of his screws and nails into coffee cans and stack them into milk crates. Hand tools were stacked in his toolbox and hanging on the pegboard behind the massive wooden table. His workbench was a magical place of puttering, where broken things were fixed or turned into something else. My mother would painstakingly pin her patterns to fabric that was spread across the Formica table with the gold specks in it. Her blue-handled scissors (never to be used on paper) and an old wooden sugar bucket filled with generations-old buttons were never far from where she worked. Across from her sewing machine, her desk sat, loaded with stacks of paper, drafts of her research and articles, paperclipped and highlighted. From a young age, though I was not aware of it at the time, I was influenced by this confluence of epistemologies.

During my doctoral studies, I was inspired by the visual model (Figure 1) of sociologist Dr. Wendy Luttrell’s “reflexive-origami North Star research design” (Luttrell, 2010, p. 161). When I saw the name of Luttrell’s model, North Star, I thought about the traditional North Star quilt pattern that I had seen used in quilts during my childhood. The North Star pattern has also been connected to a code system used by abolitionists and enslaved people to guide enslaved people North, towards freedom (Bryant, 2019). Even though her model is not the same in appearance as a traditional North Star quilt pattern, its symbolism inspired me to think about quilting as a means of senseMaking. Throughout history the North Star has been used to signify safety, home, hope, faith, freedom and truth3 (Buck, 2009; Butler, 2021; National Museum of African American History and Culture, n.d.). Many traditional quilts are made from scraps of fabric collected over the years and compiled into a tactile memory: pieces of cloth from dresses, tablecloths and other bits—each one a portal to the past. “Quilts tell stories. Their traditional role in providing warmth and comfort connects them to the most intimate parts of people’s lives, families, and homes” (Parmal et al., 2021, p. 13). Because of its associations with home and hearth, quilting is a powerful tool of resistance when used in a political or subversive context (Parmal et al., 2021; Haynes, 2022). For many of the participants, access to traditional academic spaces and skills had been closed off to them because of how they had been labeled. Using quilting as a senseMaking strategy at this stage in my research made sense as a form of talking back to traditional academic practices that privilege the written word over other forms of knowledge expression.

Figure 1. Luttrell’s model (reproduced from Luttrell, 2010, p. 161).

Research relationships lie at the center of Luttrell’s model (Figure 1). Each of the points of the star surround the research relationships in a pattern beginning with research questions at the top and moving in a clockwise fashion: knowledge frameworks, research questions, validity, research questions, inquiry frameworks, research questions, goals. The participants in this research had trusted me with their stories, their truths, and I struggled with whether or not I was able to do them justice with this work. As I looked at the fabric swatches laid across the table, I balanced the weight of my participants’ truths with Luttrell’s questions, “What specific moral, political, and ethical principles will guide your investigation? What guidelines will you follow, including and beyond, ‘Do no harm?’ What criteria of reciprocity, fairness, or justice will you use?” (p. 161). Quilting offered me a way to physically represent a coming together of my own knowledges and the knowledges of my participants. Their stories—their truths—overlapped, paralleled and followed similar patterns, just like a quilt.

It was clear to me, because of the repetition of research questions within the star, that the color and pattern choice ought to be bright. I chose a yellow fabric with white stars and a yellow-green fabric with a plant-like print and sewed them together to make four points of the star shape. The colors reminded me of springtime and bright stars—the possibilities of new growth and the awakening of dormant life—which is what my research questions were to me—an opportunity for new ideas and the possibility of old ones.

The next point to figure out was “knowledge framework.” My knowledge framework is my theoretical perspective; it is how I am thinking and listening to the participants and to myself. My knowledge framework developed out of deep reading and exploring in the areas of settler colonialism; social constructions of disability; theories of resistance; structural theory and explorations of liminality/liminal personae. This seemingly disparate collection of theories has provided me with the lenses I needed to deeply engage with the words and images of the participants. In a “hexagonal thinking”4 (Potash, 2020) visualization (Figure 2) of my knowledge framework, I was able to see that I had organized my framework into two distinct groups of literature: those that centered on structure and those that centered on agency. I needed colors and patterns that would speak to the character and organization of my framework, and would also work in concert with my inquiry framework which sits diagonally from the knowledge framework in the North Star design. Drawing from my memories of undergraduate color theory, I chose to use an analogous color to the yellow of the research questions. Analogous colors are meant to pleasing to the brain, as viewers do not have to work as hard to transition from colors that are close to each other on the color wheel. So, a visual shift from yellow to yellow-orange to orange—from research questions to knowledge framework—would be easy on the eye (see Figure 3).

I followed a similar process for selecting the colors for the rest of the star and the background. As I worked, I considered the relationship of each piece to the whole quilt. Similarly, I considered my relationship to each of the participants and to the research project as a whole. Research has the potential to destroy as much as it can create new ideas and spaces for inquiry, and that is dependent upon the relationships you hold while you work. As I sewed, I found that the area that was the most difficult was the center of the star—the space that symbolizes research relationships. On the original drawing (Figure 1), the center is open, and the endpoints of each of the diamonds forms a smaller star shape in the middle. Each piece needed to be tucked and sewed by hand in order to achieve this with fabric. This gave me a lot of time to reflect on the research relationships that I was holding. I had agonized over the representations of the words of my participants and tried to incorporate their feedback as much as possible. While I stitched, I felt a growing sense of closure. I recognized that my data and relationships with my participants helped me to understand myself as a researcher who is continually reflexive about my process. I used member-checks and had participants read, listen and ask questions along the way. Slowly, the star began to take shape as I thought about the truths of the participants and how their truths formed the North Star of this project. In Block’s (2008) book, Community: The Structure of Belonging, author Peter Block writes:

Belonging can also be thought of as a longing to be. Being is our capacity to find our deeper purpose in all that we do. It is the capacity to be present and to discover our authenticity and whole selves. This is often thought of as an individual capacity, but it is also a community capacity. Community is the container within our longing to be fulfilled. Without the connectedness of a community, we will continue to choose not to be. (p. xviii).

For me, understanding the positions from which I was looking, listening and thinking was an essential and continual part of my reflexive research process, my experience of awakening and becoming. Much of this reflexive work occurred during the quilting process. As I sewed, I realized that my senseMaking was about what it means to belong and what I now identify as a life’s worth of struggles and experiments in “longing to be.”

senseMaking creates a sense of belonging by opening research spaces for participants and researchers to truth tell and talk back. Using senseMaking to move beyond traditional research methods provided me with the opportunity to create work that speaks to the relationships that were nurtured throughout the research process. I sought to create a space for the participants’ counter narratives within academic literature as a way to inform policy and pedagogical decisions. It became clear to me as I engaged in the analytical work that discourse and narrative analysis were not going to be enough—that my participants required more of me as a researcher. Poetry and quilting served as senseMaking tools to make space for the participants and myself to truth tell and talk back to places where we felt our experiences were ignored, or made invisible within traditional educational literature. senseMaking offered me an opportunity to show that I had heard them and that they belong. While their experiences speak to a very specific place in school—self-contained environments—the understandings and senseMaking of this work are not limited to the discourse of special education or even to the field of education. As Ace very clearly stated, “it did not matter whether I was getting the education I wanted, I was in an environment I did not want to be in.” Ace’s words reveal the complexity and necessity of a very basic human desire—a need to belong. senseMaking as an analytical, epistemological, reflexive and liberatory approach to research made space for the participants and researcher of this study to truth tell and talk back to systems and structures that have previously contained and silenced their participation.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: this data is private and restricted to the public. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Y2xhcmtlbWlseWJwaGRAZ21haWwuY29t.

The studies involving humans were approved by CUNY Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^All names of people and schools are pseudonyms, selected by the participants, used to protect their identities.

2. ^For well-over a decade, I worked in many different roles within a New York City public school program that operates in Manhattan. Teaching in a small community can sometimes create long-lasting connections and I remain in touch with an extensive network of former students. Since their leaving school (either via graduation or for another reason), I have followed their lives and they mine. Identifying this group of participants as “former students” signifies two things: (1) they are former students of the NYC public school system and attended self-contained programs at some point in their education and (2) they are my former students, meaning that at some point I worked with them in an educational capacity (teacher, mentor, tutor, crisis support, listener, coach etc.).

3. ^During World War II, my grandfather William Clark served with the Navy as the Chief Quartermaster, Signals and Navigation aboard a number of ships. As a celestial navigator, he was responsible for guiding his ship using the stars. I can recall being in his backyard as he tried to teach me about the stars, including the North Star, and explained how they would always be there to help me find my way.

4. ^“Hexagonal thinking” is a visual thinking tool that I learned about from the blog, cultofpedagogy.com (Potash, 2020). In a hexagonal thinking activity, you begin with a stack of hexagons. On each hexagon you write a term, idea, title etc. in the middle. Once you have a bunch, you can lay them out and arrange them while paying careful attention to the connections between the hexagons. Once you have them arranged how you want, you write out an explanation of each of the connecting sides.

Annamma, S. A., Connor, D., and Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethn. Educ. 16, 1–31. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2012.730511

Annamma, S. A., Ferri, B. A., and Connor, D. J. (2018). Disability critical race theory: exploring the intersectional lineage, emergence, and potential futures of DisCrit in education. Rev. Res. Educ. 42, 46–71. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18759041

Brooklyn Museum (2021). Nick cave: truth be told Brooklyn Museum Available at: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/nick_cave?gclid=CjwKCAiAxvGfBhB-EiwAMPakqujDSZy8pmHHX_t68p4joOAhVJx8-_LcCroS8TirjYGBn6864xz00RoCwv4QAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds.

Bryant, M. C. (2019). Underground quilt codes: what we know, what we believe, and what inspires us Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage Magazine Available at: https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/underground-railroad-quilt-codes.

Buck, W. (2009). Atchakosuk: Ininewuk stories of the stars. First nations perspectives. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre Inc. 2, 71–83.

Butler, B. (2021). I go to prepare a place for you [quilt]. Smithsonian, Washington, DC. Available at: http://n2t.net/ark:/65665/fd5ccbe181b-262f-4564-b229-e19e664ae8fd

Connor, D. J. (2006). Michael’s story: “I get into so much trouble just by walking”: narrative knowing and life at the intersections of learning disability, race, and class. Equity Excell. Educ. 39, 154–165. doi: 10.1080/10665680500533942

Connor, D., Ferri, B., and Annamma, S. (2016). DisCrit: disability studies and critical race theory in education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Ellis, C. (2007). Telling secrets, revealing lives: relational ethics in research with intimate others. Qual. Inq. 13, 3–29. doi: 10.1177/1077800406294947

Ferri, B., and Connor, D. (2005). In the shadow of brown: special education and overrepresentation of students of color. Remedial Spec. Educ. 26, 93–100. doi: 10.1177/07419325050260020401

Foucault, M. (1965). Madness and civilization: a history of insanity in the age of reason. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Haynes, C. (2022). “The subversive power of quilts: legacy Russell on ‘the new bend’” in Art review Available at: https://artreview.com/the-subversive-power-of-quilts-legacy-russell-on-the-new-bend/

Hooks, B. (1986). “Talking back” in Discourse, vol. 8, 123–128. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44000276

Kauffman, J. M., Landrum, T. J., Mock, D. R., Sayeski, B., and Sayeski, K. L. (2005). Diverse knowledge and skills require diversity of instructional groups: a position statement. Remedial Spec. Educ. 26, 2–6. doi: 10.1177/07419325050260010101

Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Luttrell, W. (2010). Qualitative educational research: readings in reflexive methodology and transformative practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Meiners, E. R. (2007). Right to be hostile: schools, prisons and the making of public enemies. New York: Routledge.

National Museum of African American History and Culture . (n.d.) North Star a digital journey of African American history. Available at: https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/digital-learning/north-star

New York City Department of Education . (2021). Special education. Available at: https://www.schools.nyc.gov/learning/special-education

Parmal, P. A., Swope, J. M., and Whitley, L. D. (2021). Fabric of a nation: American quilt stories. Boston, MA: MFA Publications.

Potash, B. (2020). Hexagonal thinking: a colorful tool for discussion. Available at: https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/hexagonal-thinking/

Smith, C. (2021). How the word is passed: a reckoning with the history of slavery across America. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

Keywords: educational deservingness, belonging, self-contained special education, senseMaking, truth telling, poetry, quilting, disability critical race theory (DisCrit)

Citation: Clark EB (2023) “Aggravated, everyday aggravated—everyday”: senseMaking to truth tell, talkback and find belonging in educational research. Front. Educ. 8:1175457. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1175457

Received: 27 February 2023; Accepted: 09 October 2023;

Published: 02 November 2023.

Edited by:

Aaliyah El-Amin, Harvard University, United StatesReviewed by:

Gretchen Brion-Meisels, Harvard University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Clark. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emily B. Clark, Y2xhcmtlbWlseWJwaGRAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.