- 1Center for Research and Development in Dual Language and Literacy Acquisition, Department of Educational Psychology, School of Education and Human Development, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 2Education Leadership Research Center, Department of Educational Administration and Human Resource Development, School of Education and Human Development, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

Introduction: Research is still emerging on how to develop school leaders’ instructional capacity. We implemented research-based practices through virtual professional leadership learning communities (VPLCs) for building school leaders’ instructional capacity. We examined school leaders’ perceptions of (a) the effectiveness of the VPLC as a vehicle for improving instructional practices, (b) the essential components of an effective VPLC, and (c) school leaders’ instructional leadership practices through discussions within VPLC.

Methods: The participants of this study were 40 school leaders at the principal and assistant principal levels in elementary schools in the state of Texas. Based on the research purpose and design, multiple types of data were collected to explore participants’ perceptions and experiences of VPLC.

Results: Based on both qualitative and quantitative analyses of the data from questionnaires and interviews, we found that this VPLC allowed participants to share leadership research and resources and provided them with an avenue for collaborating and communicating with other school leaders. The results of the qualitative data revealed two major components that the participants thought a VPLC should provide based on their experiences in the program (a) community building through collaboration and (b) reflective modules and discussion.

Discussion: An SST explanation can potentially reduce some aspects of homophobia among both healthcare professionals and lay people. Also, worryingly, Chinese healthcare professionals, especially medical professionals, reported more homophobia than lay individuals These VPLCs were regarded as grounds for innovation, as participants worked together with other school leaders to find problems and determine creative and workable solutions focused on building instructional capacity in serving high-needs schools. Thus, school leaders can be supported through sustained, effective professional learning in communities of practice, or virtual professional leadership learning communities.

Introduction

High-needs schools suffer from a lack of effective school leaders (Beesley and Clark, 2015; Grissom et al., 2019), yet noted, those in leadership positions at high-needs schools often face more challenging conditions, such as academic performance, lack of resources, and less parental involvement (Tan, 2018). Furthermore, Wieczorek and Manard (2018) found that newly appointed school leaders often fill leadership positions in low-performing schools, adding a relative lack of experience to existing challenges. However, we contend that technological advancements can be harnessed to address such challenges. As technology improves, so does the ability to disseminate information to major stakeholders, including school leaders, and so does the ability to have those leaders communicate and work with each other or with experienced leaders. Thus, technology has provided breakthroughs in professional learning. As such, professional development and technological improvement merge and work in harmony to produce a growing experience that school leaders can negotiate with their learning needs within flexible schedules.

Irby et al. (2017) suggested that virtual professional development allows school leaders to engage in the professional development at their own pace. Since their learning experiences are ongoing, school leaders can benefit from stronger levels of support over a more extended period than that provided by a short face-to-face professional development. One way to provide sustained interaction is through professional leadership learning communities (PLC), a method that holds promise (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015), yet for which there exists little evidence (e.g., Haiyan and Allan, 2021). As such, we suggest the support of school leaders through research-based virtual PLC (VPLC, Irby, 2020) aligned to the needs of their leadership positions. A successful strategy for encouraging VPLCs among school leaders, as suggested by Irby et al. (2022), is to pair them with virtual mentor coaches so they can receive support as they participate in VPLCs. As a result of such a strategy, school leaders may develop their leadership skills and build their capacity. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to determine how the practicing school leaders at the principal and assistant principal levels perceived (a) the effectiveness of VPLC as a vehicle for improving their instructional leadership practices, (b) the essential components of an effective VPLC, and (c) their instructional leadership practices through discussions within VPLC. For the purpose of our study, we used the Texas Principal Standards as outlined in the Texas Administrative Code (Title 19, Part 2, Chapter 149, Subchapter BB, RULE §149.2001). The standard related to instructional leadership is as follows:

The principal is responsible for ensuring every student receives high-quality instruction.

(A) Knowledge and skills.

(i) Effective instructional leaders:

(I) prioritize instruction and student achievement by developing and sharing a clear definition of high-quality instruction based on best practices from research;

(II) implement a rigorous curriculum aligned with state standards;

(III) analyze the curriculum to ensure that teachers align content across grades and that curricular scopes and sequences meet the particular needs of their diverse student populations;

(IV)model instructional strategies and set expectations for the content, rigor, and structure of lessons and unit plans; and

(V) routinely monitor and improve instruction by visiting classrooms, giving formative feedback to teachers and attending grade or team meetings.

(ii) In schools led by effective instructional leaders, data are used to determine instructional decisions and monitor progress. Principals implement common interim assessment cycles to track classroom trends and determine appropriate interventions. Staff has the capacity to use data to drive effective instructional practices and interventions. The principal’s focus on instruction results in a school filled with effective teachers who can describe, plan, and implement strong instruction and classrooms filled with students actively engaged in cognitively challenging and differentiated activities (Texas Administrative Code, 2014, p. 1).

Principals and assistant principals are assessed with the Texas Principal Evaluation and Support System (TPESS; Texas Education Agency, 2023) using the Texas Principal Standards. The TPESS incorporates the following instructional leadership competencies: implement rigorous curricula and assessments aligned with state standards, including college and career readiness standards; help develop high-quality instructional practices among your teachers that improve student performance; monitor multiple forms of student data to inform instructional and intervention decisions, you contribute to maximizing student achievement, and ensure that effective instruction maximizes the growth of individual students, supports equity, and eliminates the achievement gap.

Review of literature

We followed a standard literature review in which we reported the current status of the research on the topic (University Writing Center, 2023). Specifically, we summarized information on virtual professional leadership learning communities for school leaders.

Irby (2020) defined a PLC as a community of participants who come together to learn new approaches to teaching, assessing, differentiating, and collaborating on future practices. To be a PLC, there must be reflective learning taking place with current information processed with the input of new information (Irby, 2020). In many cases, PLCs will have a facilitator who establishes a meeting agenda, guides discussions, and records outcomes. According to McLester (2012), different professional development models, including PLCs and personal learning networks (PLNs), are being used widely. Schools have increasingly adopted staff-led PLCs for improving professional learning (McConnell et al., 2013). A strong PLC shapes leaders’ practices effectively and is an invaluable tool for helping leaders to develop their instructional leadership capacity. Earlier researchers (e.g., Irby et al., 2022, 2023) suggested that groups of school leaders collaborate effectively through PLCs using virtual mentoring and coaching to improve their professional learning.

According to Owen (2014), PLCs can also be personalized and easily accessible while building a culture of trust and respect and offering practicing school leaders directed activities, personal feedback, and modeling. Effective PLCs share some common principles. Hord and Sommers (2008) summarized the literature on PLCs and listed five key components each should include. First, supportive, and shared leadership requires collegial and collective participation. Shared leadership and responsibility foster the ongoing process of collective inquiry and the level of engagement in PLCs. Second, establishing shared values and vision among the members of PLCs promotes a commitment to student learning and guides practices about teaching. Third, effective PLCs create opportunities for educators to collectively construct new knowledge and apply their learning to practice in individual contexts. Fourth, ensuring supportive conditions is crucial in maintaining professional learners’ growth. Supportive conditions determine “when, where, and how” the members meet regularly as a unit to conduct professional learning. Finally, the shared practice involves constructively assessing each other’s behaviors in PLCs. An effective PLC encourages educators to evaluate others’ views and practices and provide constructive feedback in a way that promotes in-depth reflective analysis and assimilates new ideas.

The interest in using VPLC for leadership development is expanding dramatically, as VPLC provides school leaders with access to useful resources and new developments in leadership practices. Much still needs to be done to identify those aspects of professional development that contribute to professional growth and learning for leaders. Irby et al. (2017) suggested that professional development using communities of practice allows school leaders to work at their own pace while prioritizing their level of engagement. Since their learning experiences are ongoing, school leaders can benefit from stronger levels of support over long periods of time than that of short face-to-face professional development. Thus, there is a need to develop and support school leaders through research-based professional development by using VPLCs that are specifically aligned with their contextualized leadership needs.

Collaborative networks and professional communities are encouraged for school leaders (Fowler, 2022). School leaders need to learn how to monitor and improve their teachers’ new practices. In addition, they must become leaders of learning in order to form a community of practice. However, there is a paucity of research on school leaders’ professional development through PLCs and few researchers (Balyer et al., 2015) have investigated how PLCs facilitate school leaders’ professional development. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Tipping and Dennis (2022) examined the role of school leadership approaches using reflective practice in PLCs. They found that school leaders with online learning practices built their capacity and created opportunities to discuss online teaching practices, problem-solve, and build rapport with teachers. VPLCs can be implemented in various forms, including online platforms for sharing discussion forums and synchronous courses, thereby fostering collaborative learning opportunities for school leaders. Thus, school leaders and other staff members must be supported in various ways as they implement VPLCs in their schools. This includes continual real-time coaching support as well as constant formal professional development programs using PLCs. Leadership development programs using VPLCs are needed more than ever. However, the experimental research on VPLCs is still inconclusive. To address this issue, we sought to build school leaders’ instructional leadership capacity at the campus level through VPLCs across the state of Texas and beyond.

As part of virtual mentoring and coaching, we also introduced and enhanced VPLCs for testing within the United States. As part of the Department of Education Supporting Effective Educator Development Grant Program [SEED grant (#XXXX; Irby et al., 2017)], which focused on teachers who serve large numbers of English-speaking students [referred to in government documents as students whose native language is not English; however, in this study, we will refer to them as emergent bilinguals (EBs) and economically challenged students (ECs); free or reduced lunch students]. At-risk students, including EBs and ECs, are defined by the Texas Education Code (TEC) as those at risk of dropping out. High-needs schools (or schools with high-needs students) serve both EB and EC students as well as students within the categories within TEC 29.08.

Conceptual framework

Based on social constructivism, Collins et al. (1989) developed cognitive apprenticeship theory, which focuses on “learning through guided experience” with a core teaching method of modeling, coaching, and scaffolding (p. 457). According to McLester (2012), different professional development models, including PLCs and PLNs, are widely used. The PLC model which includes groups of staff members collaboratively learning with the goal of improving professional learning, as suggested by Tong et al. (2015), has become increasingly popular in many school districts. Quality leadership requires strong PLCs as an effective tool for shaping leaders’ practices. Previously, researchers (e.g., Harris et al., 2017; Bush, 2019) suggested that groups of school leaders from related content areas working collaboratively in PLCs effectively improved professional learning and increased student achievement.

Given their social nature, PLCs are grounded in social constructivism theories (Wenger, 1998). In PLCs, educators broaden their views and gain new insights by listening to others’ professional experiences from a variety of contexts. In addition, PLCs also employ the concept of cooperative learning from Vygotsky’s (1978) theories of development. According to Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development framework, supporting learners’ independent performance of new practices requires scaffolding. This theory helps explain how educators support each other and collaborate toward problem-solving through social interaction in PLCs. Furthermore, Wenger’s (1998) community of learners model also provided a theoretical foundation for PLCs. According to Wenger (1998), “new experiences, contexts, conversations, and relationships necessitate reframing previous understandings, as the meaningfulness of our engagement in the world is not a state of affairs, but a continual process of renewed negotiation” (p. 54). In other words, learning occurs in a dynamic process through communities of practice.

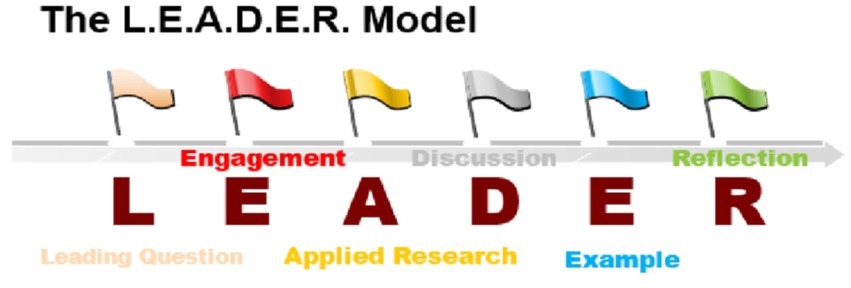

Irby (2020) defined VPLCs as online collaborations of teacher leaders who come together to learn new approaches and focus on relevant issues with leading questions, engagement, applied research, discussion, examples, and guided reflections that move the group members to transform their practice. Each VPLC follows the L.E.A.D.E.R. model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The L.E.A.D.E.R model used in VPLCs (Irby et al., 2017; used with permission).

Using different approaches, our research team built the conceptual framework, using the major components of virtual professional development (Irby et al., 2017), on effective leadership practices for school leaders, including VPLCs. The leadership group worked through the Applied Research, Discussion, and Reflection portions of the model. L.E.A.D.E.R. the model was applied to all VPLCs. Those are as follows:

1. The Leading Question helps the participating school leaders focus on the topic with a deep, probing question.

2. The Engagement provides the participants with an example or a visual representation of the topic.

3. The Applied Research provides research-based evidence that supports the topic. Without the applied research in a VPLC, we consider that new information is not interjected in the discussion.

4. The Discussion section consists of thoughtful, insightful questions that build on the leading question(s) and applied research section of the VPLC.

5. The Example section gives participants a concrete example they can take away to improve their instructional leadership practice.

6. The final step in the VPLC is Reflection.

Irby et al. (2017) developed the VPLC because: (a) school leadership and peer mentoring in VPLCs still remain rather underexplored; (b) rural school leaders serving high-needs schools have no other district colleagues with which they can be paired for face-to-face mentoring; and (c) busy school leaders have limited time for face-to-face professional development and can benefit more from ongoing, online coaching support and feedback before and after work. The research team worked with our partners, iEducate and Texas Center for Educator Excellence (TxCEE), to implement activities for participating school leaders. The VPLC steps included: (a) selecting the facilitator; (b) determining the VPLC meeting via GoToMeeting; (c) introducing leading questions and engaging participants; (d) working in groups through applied research, discussion, and example; and (e) discuss reflection and transformation as a team-next goal. The VPLCs provided its participants with communication tools, the ability to collaborate with their peers, and the opportunity to access professional learning courses, a calendar, and other resources.

Purpose of the study and research questions

As major components of professional development, professional learning networks, and communities still require more research focused on possible ways to build school leaders’ instructional capacity. Despite the increasing use of virtual platforms as venues for leadership development, little is known about how school leaders interpret their online professional learning experiences through virtual communities of practice. There is no published research that we could find reporting the evaluation of VPLCs’ efficacy in improving school leaders’ instructional practices. The proposed strategy in this study was to improve instructional leadership through VPLCs because school leaders and other staff members can be supported as they participate in their communities of practice. Since researchers (Earl and Fullan, 2003; Drago-Severson and Maslin-Ostrowski, 2018) who have studied effective professional development have called for school leaders to translate their learning into instructional practice. We addressed how the practicing school leaders perceived VPLC quality as a component of the XXX project’s virtual professional development.

In this study, we will discuss VPLCs as they relate to school leaders. Next, we will present the attributes of VPLCs for school leaders when compared to face-to-face PLCs. The goal of this VPLC was to build instructional capacity at the campus level for school leaders using communities of practice. We investigated participating school leaders’ perceptions of (a) the effectiveness of the VPLC as a vehicle for improving instructional practices, (b) the essential components of an effective VPLC, and (c) school leaders’ instructional leadership practices through discussions within VPLC. To this end, we formulated the following research questions:

1. How did the practicing school leaders perceive the effectiveness of VPLC as a vehicle for improving their instructional leadership practices?

2. What did the practicing school leaders perceive as essential components of an effective VPLC?

3. In what ways did the school leaders reflect upon their instructional leadership practices through discussions within VPLC?

Method

Research context and design

This study was derived from the project [The grant number for the project Accelerated preparation of leaders for underserved schools: Building instructional capacity to impact diverse learners (APLUS, U423A170053), Irby et al., 2017], under the U.S. Department of Education SEED Program, which focused on the school leaders working in high-needs schools across the state of Texas. This federally funded project supported the leadership development of effective school leaders by (a) recruiting and preparing leaders, (b) providing VPLC activities to current school leaders, and (c) increasing the number of highly effective school leaders in schools with high concentrations of high-needs EBs and ECs. This project has been promoting diversity in the educator workforce by recruiting male and female school leaders, particularly targeting participants who identify as African American, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian, and Asian.

Based on the research purpose and design, multiple types of data were collected to explore participants’ perceptions and experiences of VPLC. A concurrent mixed methods design was employed, in which quantitative and qualitative data were collected separately, and then the data were combined during interpretation (Creswell and Clark, 2017). Specifically, a self-report questionnaire was designed and administered to explore participants’ perceptions and experiences regarding the VPLC. Based on the questionnaire data results, we conducted in-depth and more extensive hour-long interviews with the participants.

Participants

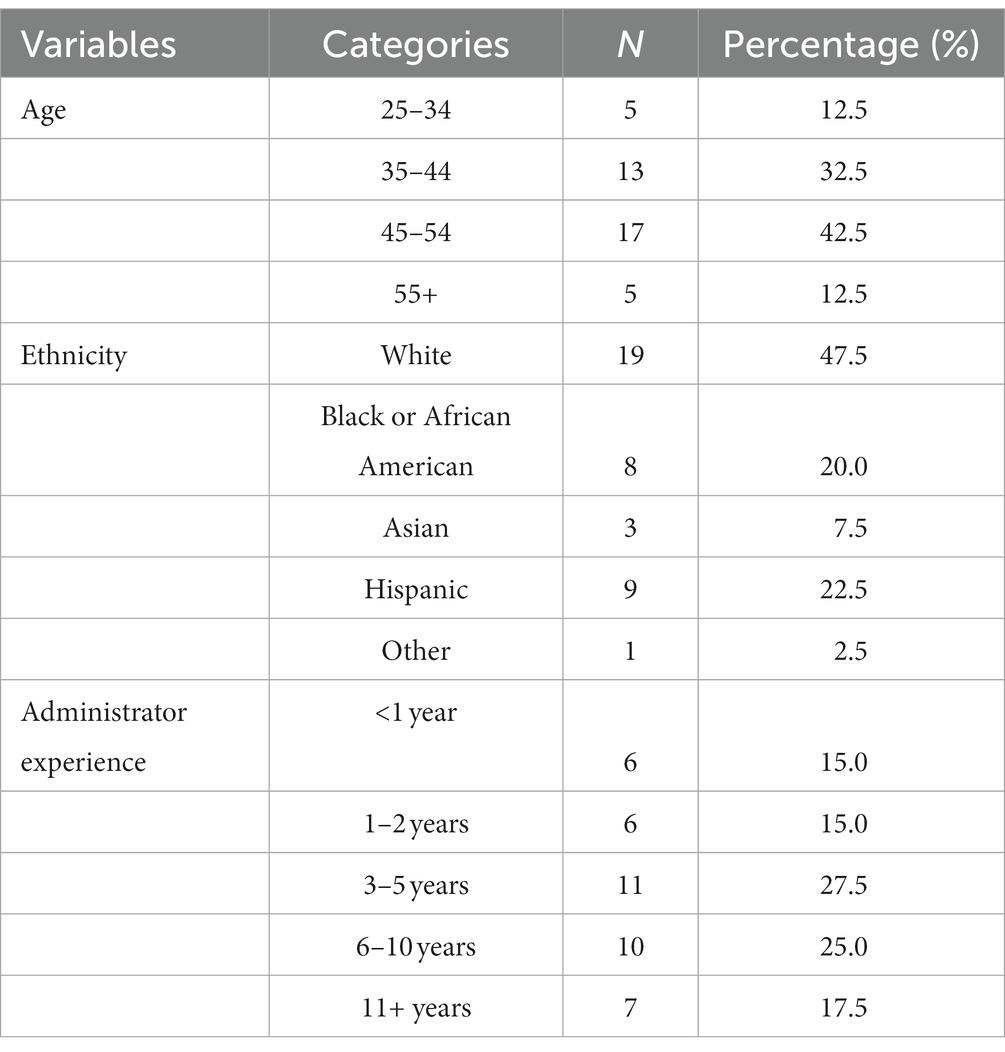

The participants of this study were 40 school leaders at the principal and assistant principal levels in elementary schools in the state of Texas. Ranging in age from 25 to 55, 12.5% of the participants (n = 5) were younger than 35; 32.5% (n = 13) of the participants were 35–44 years old; 42.5% (n = 17) were 45–54 years old, and 12.5% of the participants (n = 5) were older than 55. Approximately, 48 % (n = 19) of the participants identified themselves as White, followed by Hispanic (22.5%, n = 9), Black/African American (20%, n = 8), Asian (7.5%, n = 3), and Others (3%, n = 1). Concerning their experience of being a school leader, 15% of participants (n = 6) had below 1 year of experience, 15% of them have worked as an school leader for 1–2 years (n = 6). As displayed in Table 1, 27.5% of participants (n = 11) reported that they have worked as a school leader for 3–5 years, 25% of them (n = 10) claimed their experience as 6–10 years, and 17.5% of them had above 11 years (n = 7) of experience as a school leader. Detailed information on the participants’ demographic variables is provided in Table 1. These 40 participants completed the questionnaire to evaluate the effectiveness of the VPLCs. Ten of these 40 participants volunteered, based on their availability, to take part in individual semi-structured interviews. These 10 participants ranged in years of experience between less than 1 year and above 5 years of being an assistant principal or principal, and the majority (eight of 10) were self-identified as White and two as Hispanic.

Description of intervention

The virtual professional leadership learning communities for school leaders

The research team provided sustained and collaborative professional learning for school leaders through reflective activities and presentations. Through GoToMeeting, an online video conference platform, the school leaders followed an agenda for discussing related modules and activities. Specifically, the research team developed an action plan to promote learning by targeting instructional quality. The research team further developed strategies to increase participant success in a virtual environment, providing flexible due dates, clear guidance, organized course modules, and frequent communication so participants would know what was expected of them. Strategies included reflective, personalized, and experience-based content that was relevant and personal to the participating school leaders. Included in this virtual learning environment was a continual practice in relationship building and exploring how mutual collaborations lead to both individual and campus improvement. Participants were engaged in intense discussions and shared leadership strategies they could use to build multi-tiered systems to foster the promise of equitable learning opportunities. Through virtual modes of delivery, learning communities were created to increase professional growth while establishing a career-long support network that could only exist because of this virtual learning environment. The VPLC included (a) lessons and supporting sources applicable to various school settings, (b) communication tools to promote interaction among school leaders, and (c) collaboration tools for discussion, planning, group assignments, and leadership development.

The PLC was virtually designed as a leadership development tool to address prevailing issues in developing school leaders’ instructional leadership capacity. We conducted VPLCs with virtual mentor coaches. We provided VPLC during the eight-week for school leaders. Through LogMeIn GoToMeeting, which is an online video conferencing software, the virtual mentor coaches led the school leaders in a discussion during the VPLC modules and activities. To accomplish this, they developed an action plan to work with the leaders, which focused on improving instructional quality to improve learning. Specifically, they developed strategies to increase success in a virtual environment by providing clear guidance and communication so that the leaders knew what was expected of them during their participation in VPLCs.

We provided ongoing professional learning and encouraged the practicing school leaders to share their experiences with colleagues to promote ongoing learning within VPLCs. To improve school leaders’ leadership skills, we worked with the school leaders to help them determine what avenues might help their instructional leadership teams improve instruction for EBs and ECs while reflecting on their own leadership practice and ultimately helping teachers achieve better results. The participants took part in scheduled VPLC sessions on a weekly basis. Our research team worked to implement reflective dialogues for participating school leaders. Our VPLCs included discussions related to research, application exercises, practical implementation strategies, and collaboration with peers as they focused on building instructional leadership capacity to influence the teaching of EBs and ECs. As participants engaged, they were encouraged to share their learning, pose questions, offer recommendations or insights, and challenge themselves and each other to continue to learn and reflect. Each VPLC took between 30 and 45 min to complete, and it was a requirement to review the module and respond to the reflection section of each prior to the VPLC engagement. These modules used with the VPLCs included leadership-related topics such as (a) vision and mission, (b) building community engagement, (c) bullying prevention, (d) critical dialogue, (e) cultivating leadership, (f) culturally responsive leadership, (g) developing instructional skills specialist, (h) improving instruction, (i) leading and learning in PLC, (j) monitoring curriculum and instruction, (k) sharing leadership, (l) strategic planning, (m) using data to make instructional decisions, and (n) using the Root Cause Analysis.

Instruments

We collected the participants’ perceptions of the VPLC’s effectiveness in building their instructional leadership. We collected the data via (a) a questionnaire and (b) semi-structured interviews.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire had three sections. The first section queried participants’ demographic information. The second section included seven items on a 5-point Likert scale. The items measured the participants’ evaluation of the overall effectiveness of VPLCs in terms of (a) content, (b) organization, (c) creating interest in a topic, (d) involvement of participants, (e) use of instructional aids, (f) pace of delivery, and (g) effectiveness of the L.E.A.D.E.R. training model. We selected a 5-point Likert scale due to higher discrimination among five response options and less tendency toward the neutral point compared to the 4-point format (Adelson and McCoach, 2010; Leung, 2011). In the third section, we asked participants to respond to three open-ended questions to: (a) evaluate the virtual training format; (b) share the most effective aspects of the VPLC meetings, and (c) express what takeaways they gained from this VPLC. We developed this questionnaire to explore participants’ perceptions of their learning while engaged in learning communities focused on VPLC. The questionnaire items examined the practicing school leaders’ perceptions of the L.E.A.D.E.R. process for a VPLC and coaching practices. Two experts evaluated the content of the questionnaire items. We used their feedback on the clarity of each item and reworded some elements based on their comments.

Semi-structured interview

Semi-structured interviews with the 10 school leaders were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. According to Ivankova et al. (2006), it was appropriate to reformulate the questionnaire items into semi-structured interview questions, and some additional interview questions corresponded to the themes that emerged from the participant’s responses to the questionnaire. Ultimately, there were nine interview questions which included: (a) Have you had any experience with PLC?, (b) What was your experience with our project VPLC?, (c) What strategies did coaches use to engage you?, (d) How did coaches help you grow and influence your leadership skills?, (e) What were some examples/evidence of changes in your leadership practice throughout the VPLC (confidence, instruction, language knowledge, interests, and behaviors)?, (f) What are differences related to face-to-face PLC as opposed to virtual PLC in which you have been engaged, (g) In what ways has the VPLC L.E.A.D.E.R. helped you to build teachers’ instructional capacity?, (h) What are the benefits and challenges that you have encountered with the VPLC?, (i) How has VPLC influenced your leadership skills?, and (j) Are there any other comments or suggestions you have to improve the quality of the VPLC?. These questions were considered as only a starting point for a discussion in which participants were encouraged to express their views and concerns about the effective aspects of VPLC in our study. To ensure the validity of the interview protocol content, the initial interview questions were reviewed and adjusted by two experts in the field of Educational Administration before they were utilized.

All participants were asked permission to record their interviews. Each participant was interviewed individually via GoToMeeting, and interviews lasted about 30 min for each participant via the online platform.

Data collection procedures and analysis

Based on the research design, data were collected to explore participants’ perceptions of VPLC effectiveness. Participants’ responses to the seven-item, 5-point Likert scale portion of the questionnaire were analyzed using descriptive statistics with cross-tabulation and frequency counts. For the quantitative data analysis, the demographic information and participants’ responses to the questionnaire questions were analyzed employing descriptive statistics to describe the VPLC questionnaire items on a 5-point Likert scale.

For the qualitative analysis, we coded the data that emerged from interviews and participants’ responses to the questionnaire via the Strauss and Corbin (1990) constant comparative method. We first worked through open coding, then axial coding, and finally selective coding within predetermined codes noted as attribute codes by Miles et al. (2014). The predetermined codes were aligned to the seven items noted in the first section of the questionnaire.

The recurring themes were selected through comparison within and between each individual participant’s responses. The researchers continued to explore the emerging themes until they observed no change in the data. We triangulated the data by reviewing it independently and then coming together to arrive at a consensus about the themes. The data were triangulated to identify points of convergence and divergence (Creswell and Clark, 2017) via each investigator. Then, according to Patton (2002), we compared the interview results with the results of the open-ended questions in the questionnaire, explained key patterns and elements, and identified similarities and differences within and between sources.

Trustworthiness and credibility

For establishing trustworthiness and credibility, we adopted three strategies: (a) low inference descriptors, (b) member checking, and (c) investigator triangulation (Johnson, 1997). We used low inference descriptors to collect verbatim quotes from participants’ interview responses. Member checking was accomplished by having the participants validate that the information was consistent with their responses. We adopted investigator triangulation (i.e., multiple researchers) in collecting and interpreting the data to enrich trustworthiness through individual coding, and we coded the interviews independently using the matrix. After completing the coding independently, two of the researchers reviewed the emerging themes until they reached an agreement.

Results

We organized the findings by the three research questions and their results that follow. We present the questionnaire results to answer the first research question. To address the second research question, the results correspond to the interview questions related to how practicing school leaders perceived a successful VPLC should provide related to their experiences in the program.

Research question 1. How did practicing school leaders perceive the effectiveness of the VPLC as a vehicle for improving their instructional leadership practices?

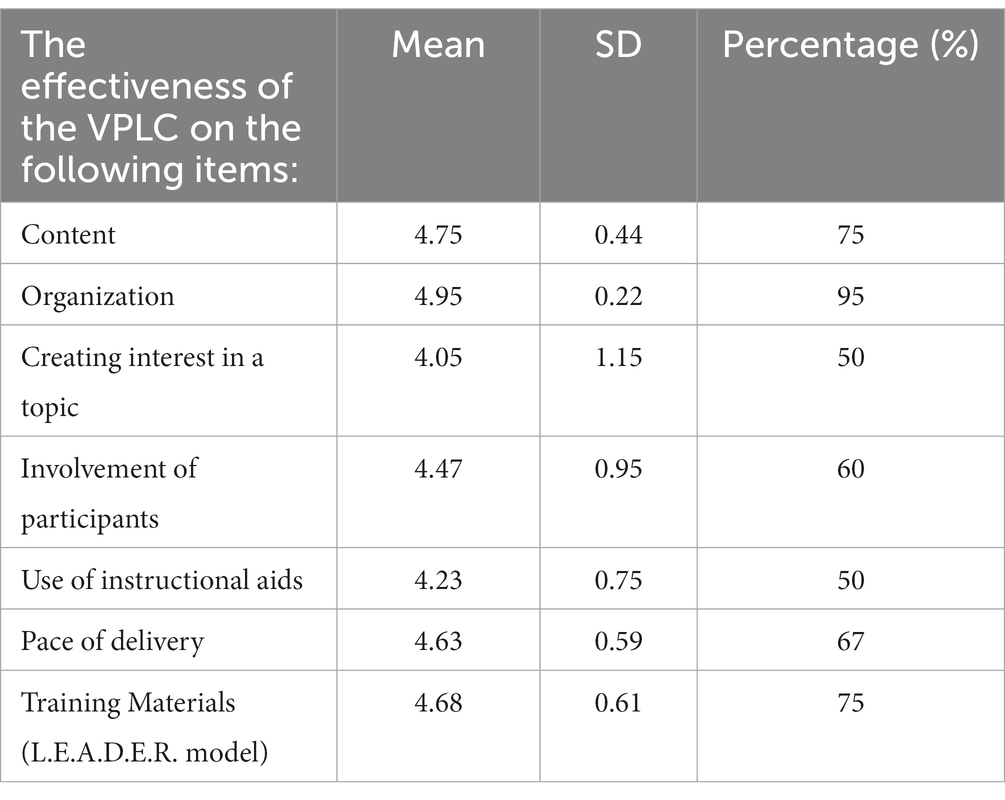

This research question was answered using both quantitative and qualitative data. Post-test scores with descriptive statistics were used to answer this research question quantitatively. Table 2 indicates that the mean ratings on the effectiveness of the VPLC by participants ranged from 4.05 to 4.95 out of 5 possible points. The participants assigned the highest scores to the organization (M = 4.95, SD = 0.22), content (M = 4.75, SD = 0.44), and training materials (M = 4.68, SD = 0.61) of the VPLC. Among the lowest ratings were for creating interest in topics, with a mean value of 4.05 (SD = 1.15), and the use of instructional aids (M = 3.74, SD = 1.08).

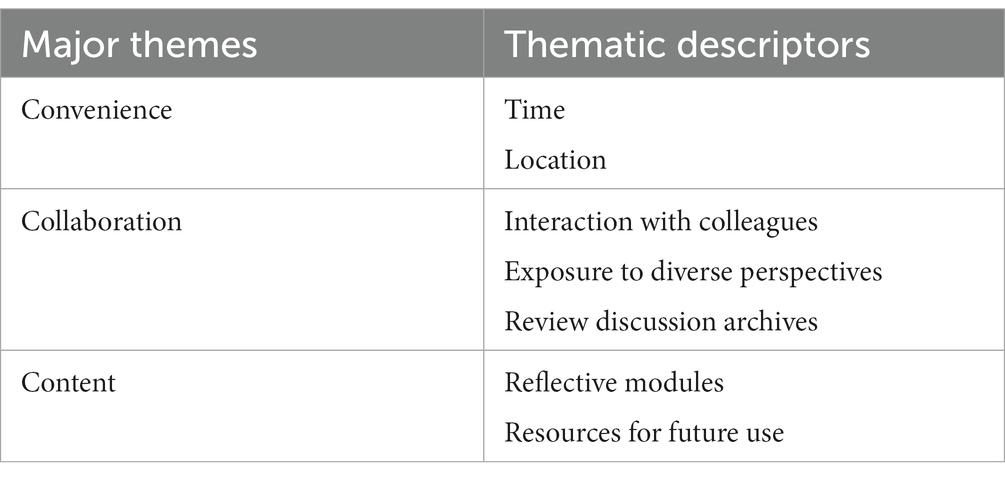

Qualitatively, open-ended questions for the post-test were used to also determine participants’ perceptions related to the effectiveness of the VPLC. The practicing school leaders in the VPLC attributed their leadership gains to the built-in training activities that pushed them to discuss the content they just studied and promoted a reflection focused on changes they could make on their campus and the potential impact on school improvement. As displayed in Table 3, the qualitative analysis results revealed three major themes that the participants thought were effective based on their experiences in the VPLC (a) convenience, (b) collaboration, and (c) content.

Convenience. As part of this VPLC, participating school leaders developed a continuous professional learning program on campus using virtual professional training and support, especially during the COVID-19 time. In VPLC, participants had access to use professional development resources at their convenience and at their own pace. A school leader, for example, stated that “… the virtual learning environment allows flexibility and supports professional learning.” Another participant commented:

The VPLC context increased scheduling flexibility and created possibilities for stimulating collaboration and knowledge-building among school leaders near and far away.

Similarly, participants’ responses to virtual delivery focused on change. Participating school leaders emphasized the importance of continuous professional growth through these changes, as well as reflection opportunities with their educator colleagues.

Collaboration. The participants confirmed in most of their responses that interaction via communities of practice was very helpful. The findings revealed that participation and interaction through the VPLC were encouraged, creating a trusting and collaborative environment. Collaboration with educator colleagues led to the establishment of rapport between novice and professional school leaders and increased administrative support. One of the participants reflected:

My principal and I [as an assistant principal] participated in the program and we were both in two different cohorts. Both can talk about it, redesigned some of the things that are going on our campus, and were able to be refreshed because of the program.

The virtual mentor coaches positively facilitated the VPLCs by connecting the participants with other leaders from different campuses. A participant commented:

I feel that 1/3 of the PLCs are working as a true collaboration. The other 2 are more in compliance mode.

These VPLCs also provided a forum where practicing school leaders could get their questions answered in a timely manner through collaboration with their group members.

Content. An analysis of the participants’ responses revealed that the VPLC content was highly associated with school leadership development, specifically focused on instructional leadership development. Participants asserted that the sustained, focused content and teaching and non-exam materials met their needs in leading a school successfully with teachers and administrators. Furthermore, the content was research-based with real-world examples, which enabled the participants to obtain an in-depth understanding of leadership knowledge and practices. One school leader participant in the program stated:

I really appreciate the case scenarios and examples and non-examples given in each module. This helps me visualize and make the research come to life.

The participants were asked to indicate whether this virtual community had met their expectations and gave their feedback and recommendations concerning the critical features facilitating VPLC. Participants’ responses to the questionnaire questions indicated a positive evaluation of the VPLC.

Research question 2. What did school leaders perceive as essential components of an effective VPLC?

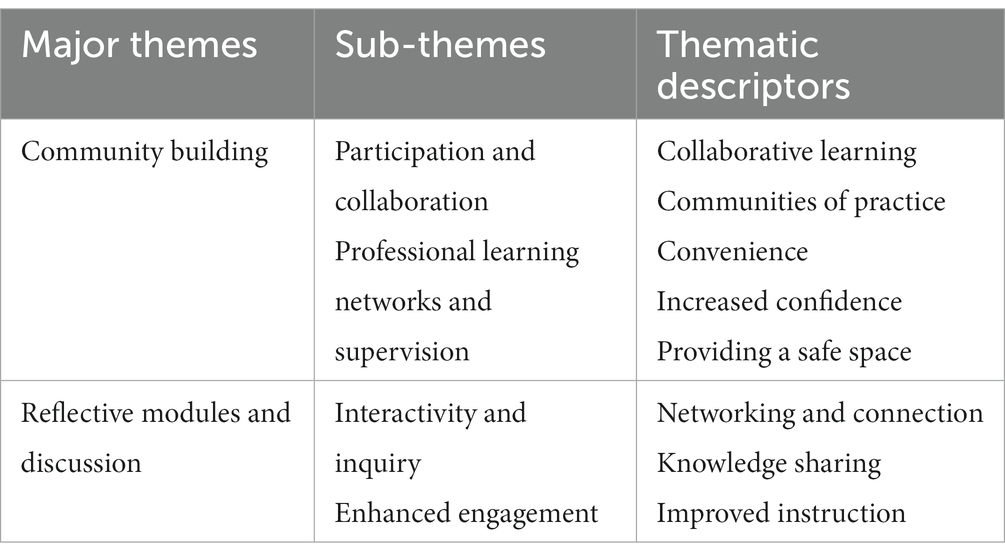

The results of the qualitative analysis of the semi-structured interviews revealed two major components that the participants thought a successful VPLC should provide based on their experiences in the program (a) community building through collaboration and (b) reflective modules and discussion. Following are the practicing school leaders’ responses to the interview questions (Table 4). Pseudonyms were used to ensure the participants’ anonymity. The excerpts below were taken from the participants’ interviews and reported as low-inference descriptors.

Community building

Participation and Collaboration. The school leaders confirmed in most of their responses that interaction via communities of practice was very helpful. The findings revealed that participation and interaction through VPLC were encouraged, creating a trusting and collaborative environment. This VPLC provided a wide range of learning opportunities and has been effective in providing real-time feedback from coaches and facilitators, helping busy school leaders receive ongoing professional development support, modeling, and feedback. A participating school leader, for example, commented:

With my personality, I love the virtual aspect because it’s kind of like I can do it wherever and where I was able to be a part of the VPLC. If I stayed late at work and we had a meeting I could just stay at work and do it. If I went home, I was able to do it. If I went to my stepdaughter’s soccer game, I was able to sit on the sidelines and still be able to do it.

Another participant said:

We were encouraged to share our learning, pose questions, offer insights, and challenge each other to continue to learn and collaborate.

In the VPLC sessions, an interactive and collaborative environment was found to be key in influencing the level of engagement of school leaders. The participants were encouraged to share their past experiences and support each other during the VPLC sessions. The participants took part in the VPLC at their chosen time, allowing them to become familiar with their facilitator and build a sense of community with other leaders from different campuses and districts. They were more actively engaged in the VPLC when adopting the partnership principles of equality and reciprocity. Leadership growth and collaboration were among the major themes revealed by the participants’ responses.

Professional Learning Networks and Supervision. Another theme emerging from the participants’ responses and reflections indicated that their knowledge was constructed through interactivity, inquiry, and supervision with other group members, providing guidelines that helped campuses develop their instructional capacity and knowledge. Participants attested that the virtual aspect of the program gave them an opportunity to make connections and establish relationships with their colleagues participating from other schools and districts. Such networking was apparent in this participant’s representative comment:

One of the things that I find stimulating is seeing the growth not only for myself but also for the teacher's growth when we see a teacher that needs some support and then when you see that they’re taking your feedback.

Since beginning the program, participants have developed an increasingly trusting relationship with their coaches and have also, in the last PLC, volunteered to share documents illustrating excellent practice. Additionally, the practicing school leaders have contacted each other outside the VPLC to further enhance their professional learning, as evidenced by the VPLC recordings. In addition, the PLC that focused on improving instruction seems to be valuable in improving participants’ instructional leadership practice. A participant, for example, specifically commented:

The virtual coach provided more directions, and clearer expectations, or found a way to inspire the teachers to embrace the vision of ongoing learning and supervision.

The VPLC also provided a forum where practicing school leaders could get their questions answered in a timely manner through discussion and collaboration with their group members. The participants agreed that this VPLC was effective, consistently commenting that the sequenced VPLC meetings helped them structure their discussions and collaboration efforts. They remarked that the VPLC positively facilitated their instructional leadership allowing them to connect with other leaders from different campuses.

Reflective modules and discussion

Interactivity and Inquiry. Another theme emerging from the participants’ responses and reflections indicated that the participants’ knowledge was constructed through interactivity, inquiry, and supervision with other group members. This dynamic helped develop their instructional capacity and knowledge through guidelines that benefited both their own development as well as their respective campuses. The participants attested that the virtual aspect of the program gave them an opportunity to make connections and establish relationships with their colleagues from other schools and districts. A school leader stated:

I think one of the benefits of this platform is that you have multiple representations of different types of organizations and school systems. So, you have small school districts, larger school districts, and possibly charter school districts. And so, with that being the case, you know reinforcing previous ideas or thoughts.

Another participant added:

I haven’t had a chance to implement my visions necessarily fully, but this platform allows you to speak in the model as if you were that campus leader and then get that feedback

The VPLC for school leaders provided increased network possibilities; it further motivated learning forums and discussions that bridge research into practice while increasing effective instructional practices. With a focus on building instructional capacity, the program modules and discussions helped the participating school leaders create a social network of support and supervision to know (a) the value of their professional communities and (b) how to use new leadership and/or instructional strategies they had previously learned but no longer used with fidelity in their current practices.

Enhanced engagement. By discussing how school leaders can work collaboratively on the issues of learning and teaching that matter to their campuses, the discussion and activities inspired them to reflect on their own leadership practice. The participants’ responses indicated a significant positive impact of VPLC on leaders regarding their self-regulation, awareness, reflection, and leveraging of their strengths. Echoing the same ideas, a school leader added:

And I think the program with all the meetings that we had really helped to share experiences and to make connections between those experiences … and it’s going to help me to make better decisions in the future. But I think the way that the program was presented was very easy to follow and very easy to understand right just like I said having this Canvas support was a plus there.

Most of the participants also shared their newly gained knowledge with other leaders in their communities. The participating leaders reported that certain practices they learned in the modules are not practices on their current campus. As they maintained, their goal is to “begin transferring what they have learned” to improve instruction on campus.

Since beginning the program, participants have developed an increasingly trusting relationship with their coaches and have volunteered to share documents illustrating excellent practices in the last VPLC. Additionally, the practicing school leaders have contacted each other outside the VPLC to further enhance their professional learning, as evidenced by VPLC recordings. In addition, the VPLC focusing on improving instruction seems to be valuable for improving participants’ instructional practice. A school leader, for example, went on further and commented:

This program allowed me to grow as a leader as I said before. It kind of allowed me to think about every time we had a different lesson, and I was able to talk to other administrators and other districts about the different lessons

Likewise, a school leader commented:

This PLC helped me to make sure that I spend most of my day in the instructional part of my job. There are a lot of administrative functions and responsibilities that really can drain the number of days that you think about how you use it. I guess that’s one of the things that I find effective.

The participants perceived discussion and collaboration, enhanced engagement, and opportunities to reflect and practice as the essential components of an effective VPLC. The practicing school leaders that were enrolled in the program were able to expand their leadership knowledge and experience by actively participating in the discussions while working on collaborative projects. In addition, the level of engagement was also reported as a key factor that affected learning. The participants believed that the mentoring and coaching structure and interactive environment (i.e., face-to-face or virtual) were the main elements positively impacting their engagement. Finally, an effective VPLC should also provide substantial opportunities for participants to reflect on their learning and practices. Reflection could be reinforced by a well-designed curriculum as well as the mentoring and coaching embedded in the VPLC.

Research question 3: In what ways did the school leaders reflect upon their instructional leadership practices through discussions within VPLC?

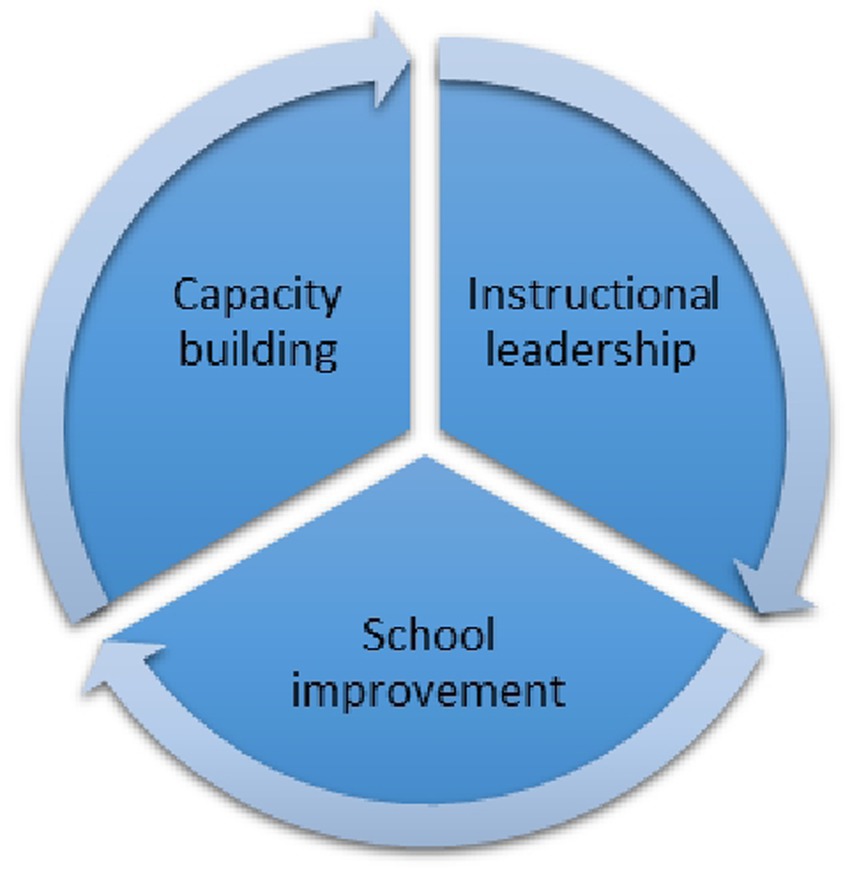

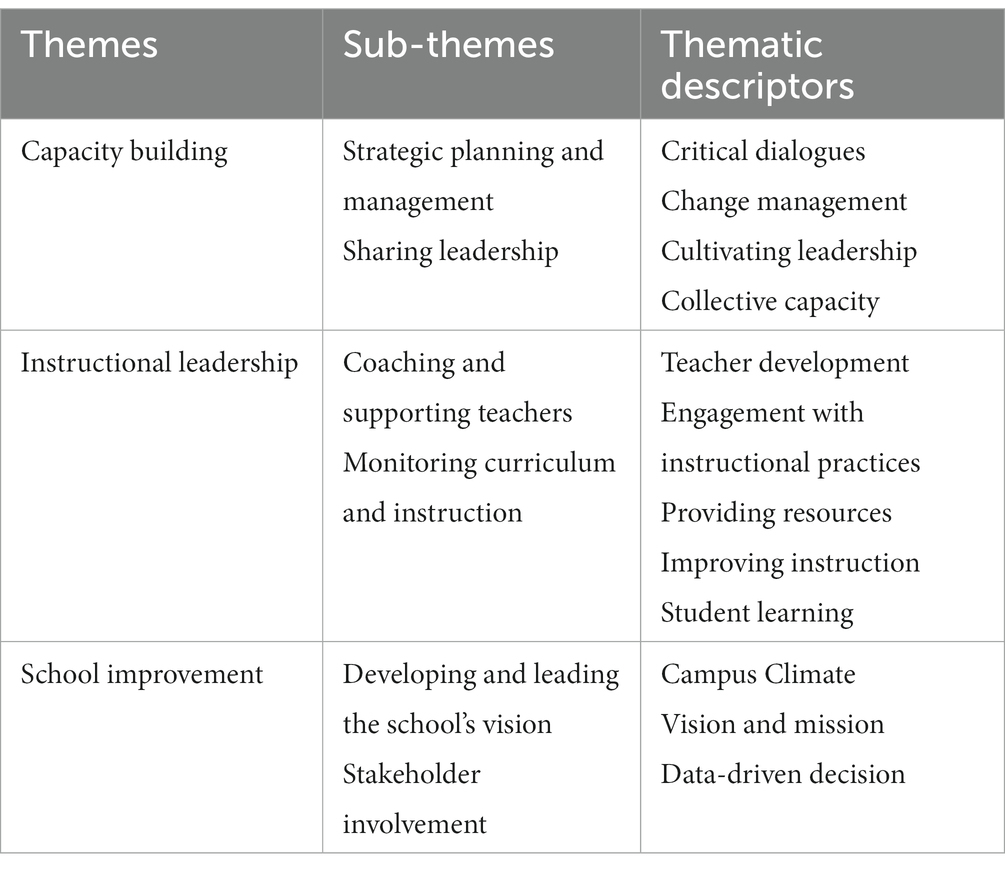

We addressed the participants’ reflections on their instructional leadership in VPLCs. Based on their experiences in and reflection on the professional development modules, the practicing school leaders applied the reflective modules to instructional leadership while using insights gained from reflection for problem-solving, translating theory to practice, and developing plans. The participants found the reflections within VPLCs personalized and relevant to their jobs, which resulted in the three cycles of learning related to professional development emerging from their responses as captured in online discussions (Figure 2). We called this a cycle of learning because the participants primarily learned from their experiences and progress in enhancing their instructional capacities through the three elements of (a) Capacity Building, (b) Instructional Leadership, and (c) School Improvement. This cycle began with the first element moving to another.

During the Capacity Building stage, the practicing school leaders partnered with each other to identify and sustain their instructional capacity for improving teaching and learning in school. During the Instructional Leadership stage, the participants were prepared to hit the goal by enhancing teacher instructional capacity at their schools and describing strategies to improve instruction for EB and EC students. Online discussions within VPLC allowed for interaction and collaboration among school leaders as they learned from their colleagues and shared their best practices for discussion, planning, and group assignments. Finally, during the School Improvement stage, participants were able to refine their professional goals through the process of community engagement. Therefore, the participants learned that their future practice would be impacted by trusting others to lead with them.

Reflection occurred within VPLC. The goal participants indicated by their reflections was related to their own instructional leadership abilities for improving student achievement and school effectiveness. Table 5 renders the major themes emerging from participants’ reflections.

Following are the practicing school leaders’ online discussions within VPLC. Pseudonyms were used to ensure the participants’ anonymity. The excerpts below were taken from the participants’ reflective discussions and reported as low-inference descriptors. No changes were made to the excerpts taken from the participants’ reflections regarding grammar, punctuation, style, etc.

Cycle of learning 1: Capacity building

Strategic Planning and Management. This cycle helped the participating school leaders to share their leadership skills while building others’ capacity to lead. As they went through professional development, they began to evaluate and seek the needs of the community. Most of the participants highlighted the significance of including all stakeholders in the strategic part of planning. For example, one participant stated:

We need to include all stakeholders to build a program that will meet the needs of all students and have a safe place for families to come and get assistance and truly trust us.

As documented in their reflections, the practicing school leaders began to establish a rapport with their campus leadership teams and a sense of trust and relationship building because of the professional development they received. The practicing school leaders’ proficiency with the strategic planning process has helped them solidify their knowledge and affirm the importance of the campus needs assessment process. For instance, one participant noted:

I need to be strategic in how I phrase questions or what type of feedback I request, but I think it would be helpful to understand the current climate in our community.

As the school academic year progressed, the participants continued to work with other leaders on campus to make sure they were doing what they needed for EBs and ECs. The participants realized that they needed a leadership team that they could trust to help them move forward with their campus vision and initiative.

Sharing Leadership. The participants learned from their group while inspiring, encouraging, and motivating others to reach their potential. One of the school leaders, for example, reflected:

In the past, I was convinced that if I wanted something done right, I needed to do it myself. However, I now know that is not going to produce the results that I desire. I have to open myself up to sharing knowledge with my team and trusting them as professionals to get the job done.

A school leader added:

I have always believed in the value of shared leadership in teachers and in building their capacity. I want them to take command of their action plans and show ownership as they themselves become their own change agent.

The school leaders could team up, drawing on expertise and sharing leadership. Their goal, as most of the participants reflected, was to build more relationships with and capacity in future leaders.

Cycle of learning 2: Instructional leadership

Coaching and Supporting Teachers. One of the sub-themes that emerged under Cycle of Learning 2 was coaching and supporting teachers. The participants maintained that they were not only responsible for ensuring that each student was receiving a high-quality education, but also for coaching teachers to improve their instructional capacity in working with EBs and ECs and providing them with support within the VPLC. School leaders who were at the frontline of instruction and interacting with students needed to be coached and coaching other leaders.

The practicing school leaders in this study continued the goal of increasing rigor in the classroom by using peer observation and feedback, utilizing their district specialists. Aside from VPLCs being conducted by team leaders, one of the school leaders reflected:

Next school year, we are going to be coaching and mentoring the new teachers that will continue with the program for the first graders. We will have the opportunity to monitor student’s progress in language development in both languages. And we will continue to receive coaching from our [VPLC] consultants.

Another school leader added:

The insights I have gained that transformed my practice are the importance of teachers’ support to have high-impact teaching and learning, and the importance of a shared clear vision so principals can have the help of supporting staff.

One of the school leaders declared that she did not have a formal coaching framework in place on campus. Based on the discussions and reflections in the VPLC, she developed a coaching framework for each campus meeting that helped her identify purpose, clarity, and accountability. In addition, she encouraged members of each VPLC to visit other classrooms to learn both effective and ineffective methods. The school leader reflected further, adding:

In grades 2-5, there is only one teacher per grade/content, so I have chosen to use the PLC model to establish opportunities for coaching. I would refer to it more as a collaborative process in which the "coach" shifts based on need and expertise. Within each PLC, I have at least one "go-to" individual to serve as a leader for various areas from data analysis to instructional strategies.

Furthermore, a participant shared:

I’d like to have a reflection sheet for the teachers to complete first and then match to my notes for better alignment of their self-reflection views with my notes.

The school leaders in VPLCs were provided with a reflection sheet. A school leader pointed to the significance of having a reflection sheet that might increase the alignment between their views and teachers’ reflections.

Monitoring Curriculum and Instruction. The practicing school leaders were constantly monitoring the impact of the reflective dialogues in cultivating curriculum and instruction during the VPLCs. One of the participants, for example, commented:

I feel validated that the work we are doing in our weekly staff development to cultivate instructional capacity is on the right path. Since we just started this cycle, it is hard to say how effective it will be just yet. The end goal is to craft educators who can naturally reflect day to day.

The participants’ goals were mostly to improve instruction and ensure consistency in monitoring and providing feedback to their teachers. With a common rubric, teachers and leadership teams have been able to have conversations across grade levels. This has also led to incorporating reflection into the specific curriculum. One of the participants reflected:

Self and regular evaluation of the implemented program is a must to see the outcomes and take necessary actions towards the ultimate goals. We must fix the weak areas and continue emphasizing the strengths areas by appreciating the individuals and teams involved in the process.

Most of the practicing school leaders found their conversation in the VPLC particularly enlightening. The support was giving school leaders what they needed, as opposed to creating one-size-fits-all staff development opportunities in which everyone participates and interacts with the same content and at the same level. This made the participating school leaders think that they need to differentiate their professional learning opportunities. A participant, for example, asserted:

In the past, I have always placed a huge emphasis on quality instruction and student growth but overlooked the importance of social and emotional learning which stretches us to equip our students with tools to engage in critical dialogues. [Critical dialogue was a topic of VPLC]

The process of monitoring helped the participating school leaders troubleshoot the curriculum concerning instructional effectiveness. Together with teachers, they were able to come up with some goals they wanted to accomplish for their campus. As evidenced by the participants’ reflections, most of them asserted they must ensure that each student has received high-quality instruction and that learning is occurring daily. As reflected in their portfolios, the participants were able to observe how teachers and instructional specialists were planning and preparing for students on a weekly basis. Thus, they maintained that those teachers who needed additional assistance have been placed in individual and coaching plans with specific goals.

Cycle of learning 3: School improvement

Developing and Leading the School’s Vision. Under this subtheme, we found that the participants’ reflections revealed a significant positive impact of VPLC discussions on their goal-directed self-regulation, self-awareness, and reflection, and leveraging their strengths. The participating school leaders assured that they had the responsibility to influence the school culture and would keep the vision as the foundation for all priorities and decisions. For example, one of the participants stated:

After much dialogue with colleagues via this platform, I am encouraged to write a journal and note the best practices and/or approaches that have proven instrumental to current leaders. I am eager to embrace a campus, however, to ensure it will be a campus of excellence under my leadership, it is vital to enhance my knowledge in platforms such as this with leaders that are experienced as well as leaders that are aspiring to become agents of change at future campuses.

Most school leaders reflected that the VPLC modules were effective, consistently stating a desire for their campus improvement planning committee to meet and review the vision and mission statements to help determine if they are applicable to students today and to their decision-making process as a team. The findings indicated that the reflection was helpful since it offered the school leaders a chance to work on the mission and vision statements to optimize their school performance and minimize difficult areas within the school community. A school leader, for example, commented:

Honestly, our mission and vision should be revised and considered for an update including all stakeholders in the process. With this new planning format, we may re-identify our mission and vision, and evaluate our current statements and how they are valued within the school community. It should be done in a well-planned timeline with all stakeholders’ involvement by using observable data in the process.

One of the school leaders added:

Changes to the vision are welcome as we also change to meet the needs of our students. Changes inform our practice and although a statement on our letterhead it is also where all decisions and practices are measured against. It will not be changed during the school year but revisited and rewritten during the summer preceding the school year.

As a result, the participants’ reflections related to VPLC provided interesting insights to lead changes in schools’ visions and inspire successful vision and mission statement design.

Stakeholder involvement. Stakeholder involvement emerged as a subtheme under Cycle of Learning 3 to improve the school PLCs. Toward the end of the VPLC sessions, the participants believed that their current administration was taking steps to make better and informed decisions that targeted the school’s needs. One of the participants wrote:

I believe it is so important to involve all stakeholders in the process no matter where you are. I also believe that our vision and mission statement is current, but I also believe it may be something that we would like to look at since it has been something that we have not looked at in the past 3 years. It is important to see if all stakeholders believe that the vision and mission is current and or needs any slight changes.

Another school leader added:

We need schools and families to work together. Everybody has a part to play. When these partnerships are formed, everyone benefits.

Similarly, a participant stated:

We as educators need to work with families because I think it is not only important to build stronger students in schools but also to build the capacity of families and stronger communities.

The participants mostly confirmed to include teachers, families, and community members in the VPLCs. The participants believed that all stakeholders should meet to identify areas in need of growth. Reflections allowed the participants to share important leadership research and resources and provided them with an avenue for collaboration with other school leaders as they proceeded through the VPLC modules and activities.

Discussion

Based on both qualitative and quantitative analyses of the data from questionnaires and interviews, we found that this VPLC allowed participants to share important leadership research and resources and provided them with an avenue for collaborating and communicating with other school leaders. These VPLCs were regarded as grounds for innovation, as participants worked together with other school leaders to find problems and determine creative and workable solutions focused on building instructional capacity in serving high-needs schools. With a focus on building instructional capacity, reflection modules and discussions helped school leaders create a support network, identify the importance of VPLC, and determine how to apply new leadership and instructional strategies.

While all school leaders can benefit from effective VPLC, this virtual leadership community, in accordance with quality professional development programs (e.g., Schaap and de Bruijn, 2018; Johnson and Voelkel, 2021), exhibits certain characteristics, including (a) discussion and collaboration, (b) enhanced engagement, and (c) opportunities to reflect. VPLCs yield collaborative professional communities of practice and reflective leadership practices in terms of better networking and collective learning. The findings are consistent with PLC characteristics proposed by earlier researchers to increase the PLC impacts. For instance, Archibald et al. (2011) suggested that an effective PLC should (a) focus on the core content; (b) provide opportunities for collaboration; and (c) include reflective modules. Hord and Sommers’ (2008) conceptual framework for PLCs also highlighted the importance of collective learning, sharing experiences and practices, and supportive learning environments. Fisher et al. (2019), in the PLC+ model, directly focused on equity and building a collective agency for educators to share that agency with students and remove barriers to learning. Levy-Feldman and Levi-Keren (2022) revealed a strong relationship between school leaders’ professional development in school PLCs and the growth-oriented mindset to help move professional learning forward, as well as the importance of providing a “tailor-made” professional development in schools (p. 1). In addition to program characteristics mentioned in previous PLC frameworks, we add that in the VPLC, how the virtual sessions were organized and conducted was also important. Specifically, if VPLCs training materials are organized and conducted under the L.E.A.D.E.R. model, they can yield school leaders more opportunities for reflection, networking, and building collective agency related to instructional leadership. We found that sustained shared leadership and goal-oriented learning during the VPLC were imperative in fostering participants’ accountability, especially in a virtual professional learning environment.

Research is still emerging on how best to develop school leaders’ instructional leadership capacity. Our research team implemented research-based practices for building school leaders’ instructional capacity through the VPLC. We found that the practicing school leaders’ perceptions of the VPLC were positive in terms of (a) increasing convenience and professional networking, (b) supporting community building and critical reflection among school leaders, and (c) providing resources for future use. The VPLC can be regarded as a gateway to increasing the scalability of quality professional development programs for school leaders serving low-performing campuses. Our nation’s school leaders can be better supported by sustained, effective VPLCs. As we work with VPLCs, we will continue to embed reflective activities related to building school leaders’ instructional leadership capacity.

According to DuFour (2004), PLCs can be the platform that instills and protects the time devoted to stakeholders’ rich conversations. PLCs allow all voices to be heard and taken into consideration by using protocols, such as the L.E.A.D.E.R. model. Supporting that notion, the National School Reform Faculty (2019) defined protocols as structured processes and guidelines to promote listening and reflection through meaningful, efficient communication, problem-solving, and learning. As we noted stakeholder involvement is critical in instructional leadership and such a VPLC protocol can promote effective collaboration by holding structured conversations among educators either during stakeholder meetings and/or in the classroom, which can ultimately result in enhancing school climate and culture.

Conclusion and implications

Based on the findings of the present research on the effectiveness of VPLC L.E.A.D.E.R. for school leaders, the following five components for developing an effective high-functioning VPLC emerged upon discussion of the findings with the participants and research team. Those are as follows:

1. The VPLC should be well organized.

2. The VPLC content should create interest in topics.

3. The training materials via the L.E.A.D.E.R. model should:

a. Help to consider diverse perspectives

b. Provide research-evidenced-based instructional practices

4. The pace of delivery and time commitment in VPLC should be considered.

5. Discussion and opportunities to reflect should be included in the VPLC.

Still, we must learn more about possible ways to reduce the cost of implementing sustained, effective PLCs. Perhaps, VPLCs have the potential for providing sustained implementation of traditional PLCs. It is necessary to have a clear vision of what VPLCs can offer school leaders. Finally, the processes and structures that affect the building of VPLCs, including size and composition, need further examination. VPLC outcomes may be influenced by participants’ demographic variables, including their age, experience, gender, and ethnicity of community members, in addition to whether participation is voluntary or mandatory. The time and location of VPLC meetings, VPLC processes, and closure activities may affect the participants’ reflection and performance. The cost of VPLC implementation, along with finding high-quality online professional learning activities remains under-explored.

To suggest a direction for future research, follow-up studies can be conducted to assess the long-term effects of VPLC. School leaders from a variety of school contexts and locations could be included in future VPLCs. It is also possible that subsequent research investigating VPLCs’ effects on participants over time would highlight the need to focus more on the implementation and evaluation of these steps among different groups of leadership teams in high-needs schools. Each school’s leader demographics, instructional resources, and support levels could prove to be mitigating factors for long-term VPLC effectiveness. Research is needed to draw attention to VPLC elements that school leaders deem appropriate for their campus and help leadership teams integrate them.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The research described in this article was supported by the U.S. Department of Education Supporting Effective Educator Development Grant Program, Project Accelerated Preparation of Leaders for Underserved Schools (A-PLUS) (Grant Award No. U423A170053).

Acknowledgments

We thank our project PIs, grant project coordinators, graduate assistants, school leaders, schools, and district officials who made this research possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adelson, J. L., and McCoach, D. B. (2010). Measuring the mathematical attitudes of elementary students: the effects of a 4-point or 5-point likert-type scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 70, 796–807. doi: 10.1177/0013164410366694

Archibald, S., Coggshall, J. G., Croft, A., and Goe, L. (2011). High-quality professional development for all teachers: Effectively allocating resources. Research & Policy Brief. National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED520732.pdf (Accessed October 20, 2022).

Balyer, A., Karatas, H., and Alci, B. (2015). School principals’ roles in establishing collaborative professional learning communities at schools. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 197, 1340–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.387

Beesley, A. D., and Clark, T. F. (2015). How rural and non-rural principals differ in high plains U.S. states. Peabody J. Educ. 90, 242–249. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2015.1022114

Bush, T. (2019). Professional learning communities and instructional leadership: a collaborative approach to leading learning? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 47, 839–842. doi: 10.1177/1741143219869151

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., and Newman, S. E. (1989). “Cognitive apprenticeship: teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics” in Knowing, learning and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser. ed. L. B. Resnick (New York: Erlbaum), 453–494.

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. London: Sage Publications.

Drago-Severson, E., and Maslin-Ostrowski, P. (2018). In translation: school leaders learning in and from leadership practice while confronting pressing policy challenges. Teach. Coll. Rec. 120, 1–44. doi: 10.1177/016146811812000104

Earl, L., and Fullan, M. (2003). Using data in leadership for learning. Camb. J. Educ. 33, 383–394. doi: 10.1080/0305764032000122023

Fisher, D., Frey, N., Almarode, J., Flories, K., and Nagel, D. (2019). PLC+: Better decisions and greater impact by design. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin.

Fowler, C. (2022). Why administrators need professional learning communities, too. Northwest evaluation association (NWEA). Available at: https://www.nwea.org/blog/2022/why-administrators-need-professional-learning-communities-too/ (Accessed February 10, 2023).

Grissom, J. A., Bartanen, B., and Mitani, H. (2019). Principal sorting and the distribution of principal quality. AERA Open 5, 1–21.

Haiyan, Q., and Allan, W. (2021). Creating conditions for professional learning communities (PLCs) in schools in China: the role of school principals. Prof. Dev. Educ. 47, 586–598. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1770839

Harris, A., Jones, M., and Huffman, J. B. (2017). Teachers leading educational reform: The power of professional learning communities. London: Routledge.

Hord, S. M., and Sommers, W. A. (2008). Leading professional learning communities: Voices from research and practice. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press.

Irby, B. J. (2020). Professional learning communities: An introduction. Summer Leadership Institute VI. Education Leadership Research Center, College of Education and Human Development, Texas A\u0026amp;M University, College Station, TX.

Irby, B. J., Lara-Alecio, R., and Tong, F. (2017). Accelerated preparation of leaders for underserved schools: Building instructional capacity to impact diverse learners (U423A170053). Funded Grant, U.S. Department of Education SEED Program.

Irby, B., Pashmforoosh, R., Lara-Alecio, R., Tong, F., Etchells, M., and Rodriguez, L. (2023). Virtual mentoring and coaching through virtual professional learning communities for school leaders: A mixed-method study. Mentor. Tutoring: Partnersh. Learn. 31, 6–38. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2023.2164971

Irby, B., Pashmforoosh, R., Tong, F., Lara-Alecio, R., Etchells, M., Rodriguez, L., et al. (2022). Virtual mentoring and coaching for school leaders participating in virtual professional learning communities. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 11, 274–292. doi: 10.1108/IJMCE-06-2021-0072

Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W., and Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods 18, 3–20. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05282260

Johnson, R. B. (1997). Examining the validity structure of qualitative research. Education 118, 282–292.

Johnson, C. W., and Voelkel, R. H. (2021). Developing increased leader capacity to support effective professional learning community teams. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 24, 313–332. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2019.1600039

Leung, S. O. (2011). A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 37, 412–421. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2011.580697

Levy-Feldman, I., and Levi-Keren, M. (2022). Teachers’ and principals’ views regarding school-based professional learning communities. Int. J. Teach. Educ. Prof. Dev. 5, 1–15. doi: 10.4018/IJTEPD.313940

McConnell, T. J., Parker, J. M., Eberhardt, J., Koehler, M. J., and Lundeberg, M. A. (2013). Virtual professional learning communities: teachers’ perceptions of virtual versus F2F professional development. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 22, 267–277. doi: 10.1007/s10956-012-9391-y

Miles, M., Huberman, M., and Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. 3rd Edn Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2015). Science teachers learning: Enhancing opportunities, creating supportive contexts. The National Academies Press.

National School Reform Faculty (2019). What are protocols? Why use them? Available at: https://www.nsrfharmony.org/whatareprotocols/ (Accessed October 20, 2022).

Owen, H. D. (2014). Putting the PLE into PLD: virtual professional learning and development. JEO 11, 1–30. doi: 10.9743/JEO.2014.2.1

Schaap, H., and de Bruijn, E. (2018). Elements affecting the development of professional learning communities in schools. Learn. Environ. Res. 21, 109–134. doi: 10.1007/s10984-017-9244-y

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Tan, C. Y. (2018). Examining school leadership effects on student achievement: the role of contextual challenges and constraints. Camb. J. Educ. 48, 21–45. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2016.1221885

Texas Administrative Code (2014). Principal’s standards (title 19, part 2, subchapter BB, RULE §149.2001). Available at: https://texreg.sos.state.tx.us/public/readtac$ext.TacPage?sl=R&app=9&p_dir=&p_rloc=&p_tloc=&p_ploc=&pg=1&p_tac=&ti=19&pt=2&ch=149&rl=2001 (Accessed February 20, 2023).

Texas Education Agency (2023). Texas principal standards. Available at: https://tpess.org/principal/standards/ (Accessed February 20, 2023).