- 1School of Health Sciences and Social Work, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 3Faculty of Education, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Faculty of Education, Edith Cowan University, Perth, WA, Australia

Children are significant stakeholders within education and care settings. Their views can be invaluable in thinking about what matters to conceptualising, assessing and improving quality in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and Outside School Hours Care (OSHC) settings. As stakeholders, children’s views are rarely listened to by Australian policy makers to assess what constitutes quality and how the quality can be improved. In the process of updating two nationally approved Australian Learning Frameworks (ALFs): Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia 2.0 and My Time Our Place: Framework for School Age Care in Australia 2.0, children’s responses provided meaningful insights into their perceptions of the practices of the educators. The children’s perspectives were gathered in a combination of research methodologies of talking circles, dialogic drawing, and visual elicitation. Their responses about experiences in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and Outside School Hours Care (OSHC) contexts were analysed to provide a deeper understanding about the characteristics of their experiences in the settings. The research process delivered information about children’s perspectives about pedagogical principles and practices that describe the Australian children’s education and care workforce and environments. The process of gathering the children’s perspectives is not without limitations, however the information is invaluable in considering the assessment and improvement of quality in children’s services.

1. Introduction

The Australian children’s education and care workforce develops and implements programs for children based on two national curriculum guidelines [known as the Approved Learning Frameworks (ALFs)] –Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia 2.0 and My Time Our Place: Framework for School Age Care in Australia 2.0. These Frameworks guide practice in kindergartens/preschools, long day care centres, family day care and outside school hours care (OSHC). The Frameworks are part of the National Quality Framework (NQF) (2021) and contain explicit examples of the ways in which educators use pedagogical practices to engage children to achieve quality outcomes for learning, development and wellbeing. These Frameworks were updated in 2023 by a collaboration of six researchers who worked closely with a consortium of professionals and academics. The writing of the first versions of the ALFs did not have any contributions by children. As part of this research project the researchers examined research tools that would invite children to give their perspectives about the principles and pedagogical practices of the workforce that facilitated the programs of care and education in ECEC and OSHC settings. In so doing children were recognized as key stakeholders in the project and contributed to the updating of these pivotal policy documents that are part of the quality assurance process in children’s services.

The research project was intended to examine the relevance of the frameworks and update the content to be relevant to the field. This article describes the process of facilitating the inclusion of children’s voices as part of this larger research project to review and refresh the ALFs. In particular, the research question about the principles and practices of the workforce that contribute to quality education and care settings. In the project, engagement with children made visible diverse perspectives characterizing their experiences in ECEC and OSHC particularly as it pertained to the quality and characteristics of their experiences and interactions with the children’s services workforce. This included the descriptions of pedagogy, principles and practices that inform workforce roles and responsibilities. Children’s rights to have a say about their experiences were upheld. The children made unique insights about criteria to use when assessing the quality and characteristics of the workforce.

The introduction to the paper sets the context for discussing the quality of the workforce characteristics in Australian education and care services. It introduces the significance of research processes that include children. It highlights how the research design to update the Frameworks from the outset honored the voices of children in the choice of methodologies. Also, the paper includes insights children proposed about the characteristics of the workforce and environment they expected in the education and care settings they attend. The conclusion of the paper advocates for the use of methodologies that could be adopted more broadly in children’s services settings to provide rich insights when assessing both children perspectives of their learning, development and wellbeing in conjunction with assessing the quality of settings.

2. Education and care sector in Australia

The Australian education and care sector comprises a diverse mix of settings catering for children prior to compulsory school entry such as kindergartens and long day care, schools and before and after school care services for older children. The current service system, a term used loosely here, is the outcome of an historically piecemeal approach to policy, funding and administration in education and care (Irvine and Farrell, 2013). Now seen as a quasi-market (Carey et al., 2020), the sector comprises around 16,500 services which are delivered by a range of providers, most often characterized as private for profit (50%), private not for profit (community managed and other organizations, 34%), government managed (State and Local, 7%) and school based (State, Independent and Catholic, 8%; ACECQA, 2021, p. 8). Regardless of service type or provider, the vast majority of ECEC and OSHC services operate under a National Quality Framework (NQF), the exception being some preschool education programs in the year before compulsory school that sit within the school system. The NQF includes legislation and regulations, a National Quality Standard and two nationally ALFs. Designed to drive continuous quality improvement and enhanced educational and developmental outcomes for children, the NQF is founded on a set of guiding principles including recognition of children as capable and agentic learners and their right to participate in decisions that affect them (ACECQA, 2021).

Realization of the intent of the NQF is dependent upon Australia attracting, supporting and sustaining a skilled, engaged and professional workforce (McDonald et al., 2018). The current workforce is estimated to comprise around 200,000 teachers and educators; the majority holding vocational qualifications (Education Services Australia, 2021). However, demand continues to outweigh supply, with predictions of growing workforce shortages attributed to a range of persistent challenges, most notably the lack of recognition of the professional nature of this work and associated remuneration (Irvine et al., 2016; Education Services Australia, 2021). Increasing, government and community expectations and work intensification have also been recognized as impacting attraction and retention (ACECQA, 2021). Despite the number of children and families using ECEC and OSHC settings there appears to be a paucity of research about the determinants for assessing high quality services (Vermeer et al., 2016). A small but growing number of Australian studies (McDonald et al., 2018; Harrison et al., 2019) highlight key factors contributing to engagement and retention of educators including their sense of purpose, enjoyment working with children, and knowing they are making a positive difference. However, in these studies children’s contribution to assessing the quality of the services in which they are stakeholders are not featured.

3. Children’s right to have a say about their education and care

The Children’s Rights agenda draws on The Convention on the Rights of Children (UN, 1989) and states that children should have a say on matters that affect them (Article 12). It has cultivated child research by nurturing a realization that children have a right to be consulted (Smith 2013; Lundy et al., 2015), heard, and to appropriately influence the facilities and services that are provided for them (Quennerstedt, 2014; Nolas, 2015; Farina and Scollan, 2019). Adopting such a “rights-based” framework actively positions children’s contribution as an inclusive approach to connecting “children’s rights, research methods and research ethics” (Mayne and Howitt, 2015, p. 37). If children are going to be heard and influence policies and services provided for them, real and tangible acceptance of their rights is necessary to amplify their voices and allow change to occur.

The relationships between adult/ researcher and child can influence the opportunities for them to ‘have a say’. Child-adult relationships are situated within a negotiated framework of process and representation. Consideration needs to be given to adults’ positioning, to enable children to participate. Nicholson et al. (2015) highlight the importance of situating child-adult narratives alongside each other to provide a more holistic view of children’s experiences. Understanding their perspectives about research methods used makes visible their motivations to engage (Lundy, 2018, 2019). In research with children, it is not enough to gather what they want to say, as the context in which they were invited to participate should also be noted.

Contemporary perspectives of children and childhood frames them as active global citizens. Theories of childhood focus on children as strong, capable and rich (Corsaro, 2014; James and Prout, 2015; Warming, 2019). Within the theoretical framework of the sociology of childhood, it is assumed children are capable of expressing their views and perspectives which are different to adults. Valuing children’s perspectives as different to adults, acknowledges children’s unique, distinctive and important contribution. Furthermore, recognizing children as capable and competent contributors in research through a shared ownership of the process enables a co-construction of meaning and richer data.

Children have often been excluded from participating in research about services for children with reasons cited as ethical considerations, researcher skills, perspectives of childhood along with research design and approaches that can influence children’s level of inclusion (Lundy, 2019; Halpenny, 2021). However, in this research project, it was important to consider adult’s attentiveness within the process. This consideration included the analysis process and adults’ looking beyond the drawing to consider children’s intentions informing meanings represented, along with sequences of thought and action defining relationships, objects, and events depicted (Harrison 2014). These considerations informed the data collection methods which empowered children allowing them to contribute to the project for updating of the ALFs.

Countries such as Sweden and Scotland have utilized consultative processes with children. The use of these processes demonstrates the value placed on children as “citizens and learners” to contribute to the development and design of curriculum and resources (Harris and Manatakis, 2013, p. 9; James and Prout, 2015; Trevarthen et al., 2018). Children’s voices assume central importance in research when reconsidering existing practices and policies designed to support their participation as active citizens in ECEC and OSHC settings. Swedish researchers (see Klerfelt and Haglund, 2014; Lager, 2016) report studies to examine workforce characteristics as well as learning curricula. In Scotland policy makers have legislated children’s rights in policy to ensure voices are listened to and quality improvements achieved (Trevarthen et al., 2018). These examples motivated the ALF project researchers to consider the value in consulting with children in the updates.

3.1. Active participation: ethics, consent, and approaches

Thoughtful processes are required to ensure the integrity of gaining insights about childhoods and children’s participation in ECEC and OSHC services from the inclusion of their perspectives. Seeking children’s participation in research involved reflecting on research intentions with consideration of how their knowledge will be used to influence policy in ways that improve their lives (Johnson et al., 2014). Children need to feel that their agency and safety are a priority (Gibbs et al., 2018). These intentions should be reflected in promotion of the research and for the informed consent processes.

Lundy (2018) promotes selecting and developing research approaches and strategies to support children’s involvement and their detailed recounts by adopting active listening and responding to them in a timely period. Rather than passive recipients of knowledge, children can be positioned as active agents who process and construct meanings and identities (Press et al., 2020; Smith and Coady, 2020; Hurst, 2021). However, given that children remain outside of major political and social power structures, their rights are only manifested through adults’ perceptions and provisions for them. The researchers were cognisant of the paradoxical nature of children’s rights and agency to influence their lives that need to be addressed before real and dynamic agency can be enabled to positively impact children.

Attempting to navigate these tensions, democratic participatory approaches offer children “a fuller range of participation,” enabling authorship of their ideas and experiences (Blaisdell et al., 2021, p. 1). Such an approach examines children’s agency against their participatory rights. Criteria is established to include reflection on the appropriateness of information communicated in response to children’s capacities, opportunities for expressing experiences, and the influence of data generated on decisions affecting them (Mayne et al., 2018). One approach is to conceptualize capturing children’s voices as a shared co-constructed process. Further recognizing children as capable research participants creates valuable insights into their worlds and a democratic approach acknowledges their views on matters of personal, community and global importance (James and Prout, 2015). This requires the use of creative methodologies to authentically engage and support children’s contributions (Clark, 2017; Mayne et al., 2018).

4. An exemplar of children’s contribution in the research design of the Australian approved learning frameworks update project

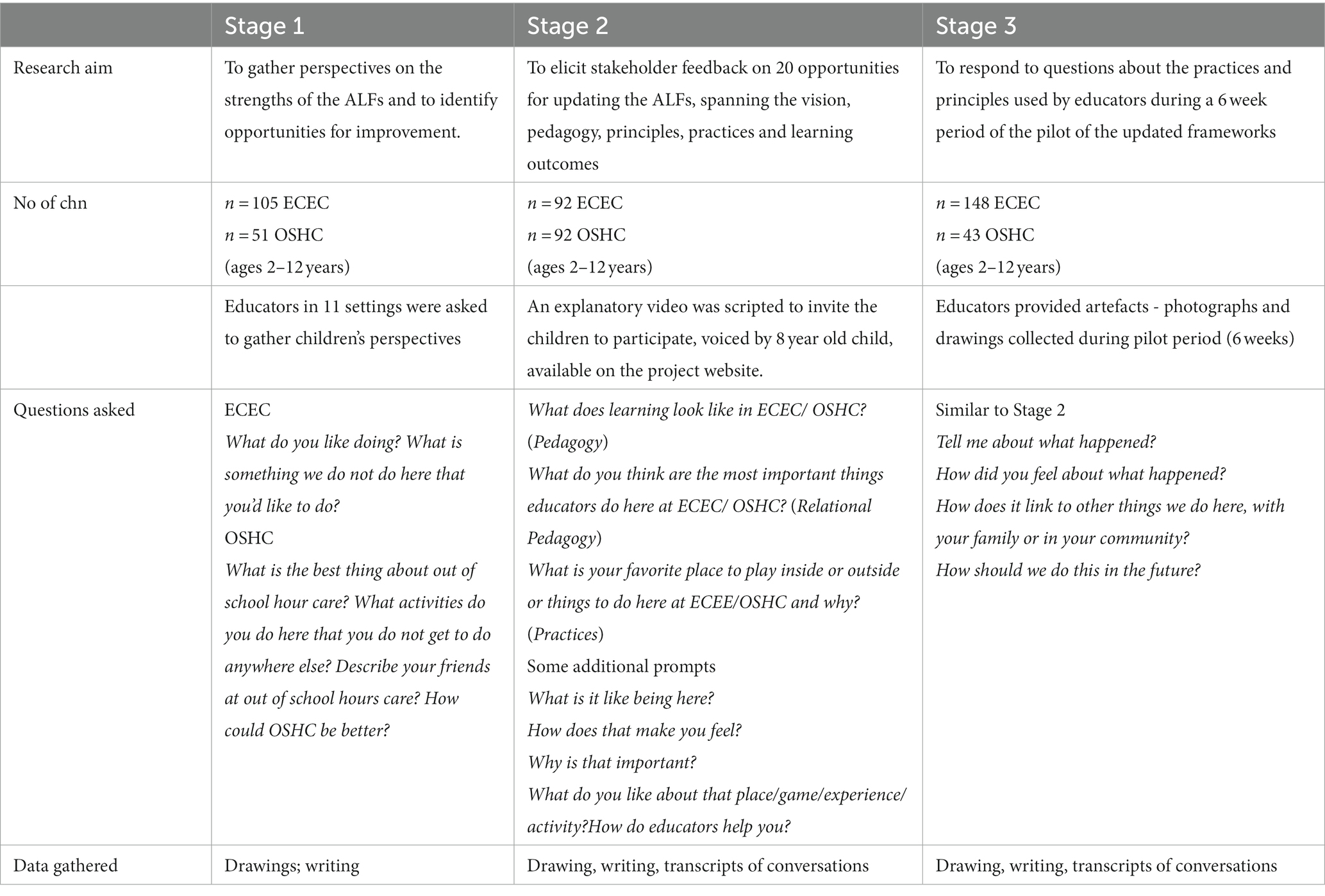

The task of the ALFs Update Project was commissioned by the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority to ensure the Frameworks reflected contemporary knowledge in programs and practices used in ECEC and OSHC settings. The Frameworks are populated with examples of children’s experiences and educators’ practices. The project occurred across three sequential stages, and was supported by a detailed engagement strategy involving a broad cross section of stakeholders (children, educators, parents, managers, policy makers) linked to education and care settings. At each of the stages specific research tools and protocols were used to explore children’s understandings and experiences (see Table 1: Children’s involvement in the three project stages).

The research design was informed by a review of literature on researching with children, as well as ethical considerations informing their consent and ongoing participation in educational research (see Johnson et al., 2014; Lundy, 2019) was undertaken. This noted the benefits of adopting a participatory framework (Gibbs et al., 2018) in conjunction with using consultative policy approaches shaping children’s educational experiences (e.g., Harris and Manatakis, 2013). The review also revealed the ethical, social and experiential forces influencing children’s agency and their voice in research (Mayne and Howitt, 2015; Halpenny, 2021). Building on these findings, the research team developed specific/tailored protocols for engaging with children alongside other stakeholders. The review noted tensions associated with agency, inclusion and the use of democratically informed processes and representation (Doel-Mackaway, 2016; Dalkilic, 2020; García-Carrión et al., 2020; Parsons et al., 2021), as well as the benefits of adopting co-constructed forms of communication to fully capture children’s perspectives (Blaisdell et al., 2021). Therefore, as part of the larger project, children contributed their perspectives about their experiences in education and care settings, including the qualities of the educators with whom they spent their time.

The ALF project researchers used multiple modes and methods for communicating with children. This ensured support to differing capacities for communication and expression (Johnson et al., 2014) and using developmentally appropriate pedagogical approaches (Arnott et al., 2020). These approaches prioritized relational and playful methodologies. The researchers developed protocols highlighting that trusting relationships were established, and that children were well informed about how their ideas are going to be used.

4.1. The participants

The children were aged between 2 and 12 years, attending either an ECEC or OSHC service across urban, regional, and remote areas of Australia. The educators at the ECEC and OSHC services were recruited to broker the research with children. As trusted figures in the lives of children, educators assumed a pivotal role in providing a supportive and encouraging context to stimulate children’s thinking about and response to specific research questions. The familiarity of the educators with the children was intended to alleviate the challenges associated with communicating with them. The choice of research tools was guided by the criteria of developmental appropriateness, language barriers and potential differential between adults and children (Pyle, 2013). Central to children feeling at ease in the research process was the role of the educator. Educators who know the children are critical to the research process to ensure full meanings about the issues being discussed are captured (see McCormick, 2018). Reflective of the diversity of children participating in Australian ECEC and OSHC settings, included were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, children from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and children with a disability. The children’s written and drawn contributions reflected their experiences in ECEC and OSHC services. The children were assigned identifiers that were linked to their contributions. Some children participated in all three stages (see Table 1: Children’s involvement in the three project stages).

4.1.1. Ethical considerations

Researching with children and young people requires careful consideration of ethical practices (Kellett, 2011; Lundy, 2018; Cheeseman et al., 2022). Ethical approval was granted by the research team’s University Ethics Committees (52021991827988 and 20210009395) and guided by the Early Childhood Australia’s (ECA) (2016). In all three Stages explanations about assent were given. All children and young people were asked for their assent and had signed consent from a parent/carer. Furthermore, in the invitation to participate, the research was explained with opportunities given to withdraw at any time. All data were de-identified and pseudonyms are used to report the findings in this paper.

4.2. The data collection process

The ALFs project placed significance on the potentials of creative methodologies with multiple forms of expression and these were used in three stages. Reflections on the use of these approaches foregrounds the development of a methodological framework for perceiving, connecting and expressing children’s contributions in partnership with educators as co-researchers (Cohrssen, 2015). Educators were given briefings and written information on how to use a selected set of research tools with children. The research tools of talking circles, dialogic drawing and visual elicitation were used in integrated ways. A flexible inductive thematic analysis was used to examine the data by the researchers (educators were unable to be included in this part of the process as they did not have release from their everyday work). The thematic analysis was across the data sets looking for similar patterns, particularly to the similar questions that were asked in Stages 2 and 3. It had an analytical focus that looked for patterns of meaning and was also linked to the literature review (Barblett et al., 2021). The researchers had also made visits to all of the sites in Stage 3 so they were aware of the context in which children made their responses.

4.2.1. Research tools

Working in collaboration with educators, three methods: Talking Circles, Dialogic Drawing, and Visual Elicitation were used in conjunction with the research questions for each stage to gain insight into children’s perspectives of their experiences in ECEC and OSHC settings. The researchers kept a diary of notes and reflections about the processes. No audio or video data were collected. Educators participated in focus groups with the researchers pre and post the data collection.

4.2.1.1. Talking circles

Talking circles are a guided conversational process (Cartmel et al., 2020). Talking circles are a relational model to support conversations with and between children in a culturally safe space (Schumacher, 2014). The format for a talking circles creates time and space for children to make connections and build trust with each other and the educator, making the way for open and genuine conversation. Each session starts with an activity designated as ‘getting connected’. This is to help the children to get to know each other and build relationships. Then, it ends with a closing activity that involves children and educators reflecting on what happened for them during the session. During this project, the educator was asked to make a written record of the children’s responses to the question ‘what have you heard or thought about during this conversation that is interesting or important’.

4.2.1.2. Dialogic drawing

As a recognized form of communication and source of data (e.g., Kress, 1997; Pahl, 1999), drawings provide children with a powerful means to express their ideas and experiences. With a focus on meaning-making, symbolism within children’s drawings offers insights into their understanding of events and issues affecting their lives (Wright, 2007). Whilst engaged in processes of creation, children often communicate their intentions, with drawings-in-action shaped by reflective ‘tellings’ (Wright, 2007). Attending to children’s dialogic reflections not only reveals their process, but also helps to clarify what they know and key people of importance and connection (Coates and Coates, 2006; García-Carrión et al., 2020). Building on the work of Einarsdóttir (2011) using draw and talk methods as an intentional strategy, Ruscoe (2021) further developed this method and named it ‘dialogic drawing’. In this project, educators were asked to prompt children to make a response, listen respectfully, pause for children to draw, and then clarify children’s representations and comments. Some educators annotated the children’s drawings as part of the process, particularly the contributions from children under 3 years of age.

4.2.1.3. Visual elicitation

Visual elicitation can involve drawings or photographs to prompt conversations (Bagnoli, 2009; Orr et al., 2020; Shaw, 2021). Using visual prompts provided by children can help to negate privileged adult interpretations as they capture children’s voices. Further, it is recommended that children are active participants in the data collection. This means that photographs used in the research process are the ones taken by the children. This can empower them to share meanings more openly thereby facilitating richer data. In this project, some of the concepts linked to the update of the practices and principles of the Frameworks were abstract so the use of photographs or drawing co-constructed by the children were valuable.

4.3. Results – what children communicated

The children’s drawings and conversations documented by educators were analysed through an iterative process (Cohen et al., 2017). The drawings were analysed for their content as to what they depicted, applying the principles of open coding and inducing categories from common content in the drawings (Merriman and Guerin, 2006). The practices of the educators emerged as a theme when the data were coded. The data collected from the various methodologies were themed for common ideas and it was also categorized into the principles and practices as described in the ALFs. The children’s responses offer unique insights into the quality of the education and care workforce. The majority of the children’s responses in the theme about the practices of educators exposed the multiple roles that educators undertook to meet the requirements of the children attending the service:

“Educators should ‘protect and entertain’ kids and love being outside but also going to the school library. My OSHC is a good time to play with my friends and I like it when educators teach us new skills such as knitting. It is also a ‘really good idea’ to talk with Educators if you have a problem. The most important thing about OSHC is ‘being protected by adults” (Chloe, 10 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle).

The knowledge and abilities of educators to establish and maintain relationships was the top priority for children. They valued communication skills highly. The children also acknowledged that educators’ knowledge and understanding of child development was significant. The communication skills of educators were valued by children as they identified the educators as someone that would be responsive to them when they felt they needed help from a trusted other. Examples of their perspectives are:

Yvonne (11 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle): “I have made some good relationships with specific educators and if I have a problem I feel comfortable talking to those educators.”

Wade (4 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle): “I like being here, the educators make me feel safe.”

Children spoke about the practices of educators. The children also listed personal qualities they looked for in their educators.

They were mindful of the practices used by educators in undertaking their responsibilities.

Emma (10 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle):‘believes that an educator should be ‘confident, have a sense of humour but not be too nice’.

Lionel (4 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle) shared: “A good teacher is someone who is smiley.”

Children also listed the kinds of support they needed to help develop their capabilities and confidence.

Michael (5 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle): “Grown ups help me to learn when I cannot do something.”

Isabel (3 years, Stage 2, Dialogic Drawing): “My teachers teach me to dance to music.”

Eva (7 years, Stage 2, talking Circle): “They take care of us for fun activities and help you cook things.”

In an ECEC setting, the children described how educators helped them to learn.

Ronald (5 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle):"When we learn, we sit on the mat and cross our legs and look at the teacher. Our teachers are kind to us.” In OSHC settings where children are more independent and seeking to manage their time and activities one child noted that educators allow them time and space to pursue their interests. Anya (9 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle): “What the educators do or do not do is important.”

The children reported information about the relationships with educators. They described what they perceived to be important for the workforce of educators, for example understanding of children’s development, in particular social development and emotional wellbeing, their interests, ways to organise the indoor and outdoor environments that are available to them.

Most responses from children about the support given to them was about meeting their physical and emotional needs. For example:

Dean (9 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle): “Teachers always care and give us food.”

Jana (3 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle): “I only like cuddles from some teachers if I am sad saying goodbye to my mum. They help me if someone is mean to me.”

Children talked about educators with knowledge of first aid and helping them when they are unwell as important. For example:

Elise (12 years, Stage 2, Talking Circle): Noticed that the staff who are studying nursing often put their hand up to provide first aid which she thought was ‘cool’.

Reflecting on a desire for agency, children noted the different qualities of educators who provided them with opportunities to ‘have a say’.

Children are social participants in their own right with power and agency. For example, in a dialogic drawing opportunity, a younger child expressed their value for educators’ support when making decisions (see Figure 1):

“This is me putting the rubbish in the garbage bin. The teachers help me decide where things go.”

The children made varied comments about practices of the workforce of educators. The children noted a higher level of engagement in the education and care setting when the workforce and the environment were presented to them in certain ways. The children answered the questions with responses about the principles and practices of the workforce that contribute to quality education and care settings. These practices can be used as criteria in the processes of assessing quality. In addition, they could be used to inform the recruitment of educators who practice in ways that improve the lives of children (Johnson et al., 2014). The children made positive comments about all aspects of the service delivery.

5. Discussion

This research shows that children can contribute to assessing and describing their experiences in rich and meaningful ways. It highlights the importance of using research methodologies with children alongside supportive educators. This process can uncover and transform understandings about the quality of the experience and interactions with the educators in education and care settings. Children were able to convey the significance of experiences that could be used as an assessment of quality.

The exemplar of the ALFs research project underlined the strengths of adopting a multi-layered approach for uncovering children’s perceptions and ideas about ECEC and OSHC settings. Each chosen approach (by ‘doing’ something different) assisted the researchers to piece together the ideas contributed to form a more complete picture of children’s experiences in ECEC and OSHC. This, in turn, provided important insights into their expectations of settings that makes them feel safe and valued, and provides opportunities for them to engage in play, leisure and learning experiences. The theme about feeling safe occurred across all age groups. The data included references to emotional and physical safety. Educators should heed this information when assessing children and young people’s learning and wellbeing. Policy makers and service leadership should heed this underpinning knowledge in workforce development plans and developing assessment reports. Children’s agency should be recognized and respected in ECEC and OSHC settings. The National Quality Standard provision of child-centred practice requires educators who can elicit and respond to children and young people’s perspectives. Quinn and Manning (2013) assert that in order to inform policy and the provision of high quality education and care, there is a need to gain children’s perspectives rather than relying on adult perceptions of children’s perspectives.

The recognition of children and young people’s perspectives is, therefore, imperative to ensuring child-centred practice is at the forefront of everyday assessment practices.

5.1. Reflections on tools, processes and relationships

Educators that participated in the process remarked on the depth of knowledge that the children expressed about the characteristics and qualities of the workforce (Researcher Diaries). As reflected in children’s responses, there was great awareness of the educators’ role, with importance placed on emotional connectedness, enjoyment of learning, and establishing an environment of care for each other. For instance, Henry commented- “The teachers do everything. It’s good being here” (Henry, 4 years), another stating- “Pick up scissors if someone is barefoot. Teachers look after the group. Teachers are nice to us. It’s fun at pre-school.” (Kelly, 4 years), and “I’m happy when I learn and have rest time. Teachers help us to make the right choices.” (Tina, 4 years).

The educators were surprised at how willing children were in contributing their ideas (Focus group: Educators). This was purposefully supported in the research design as processes were focused on relational and playful methodologies, reducing adult-child power imbalances.

5.1.1. Relational methodology

Children have always communicated with adults. However, a deeper appreciation of how this communication plays out in the complexity of the systemic features of education and care services is needed. An understanding of how to communicate with those not yet classified as adults is increasingly a skill one needs to have. Key to this is understanding how to build secure relationships. This requires time to spend ‘going alongside’ children in their everyday lives (Noonan et al., 2016) and the adult does not view themselves as more superior in the communication process. In this way children and young people will engage in conversations between themselves and adults to make meaning together. So, as adults are listening and talking, they are mindful of interpreting and co-constructing meanings about the content of the conversations with children and young people. As Noah 4 years said: “I think educators should ask us lots of things. We know lots of things.” Adults who are self aware provide children and young people with an environment where they will feel confident and safe to express themselves.

5.1.2. Playful methodologies

The creative methodologies used in this research project were playful approaches. Gathering the voices of children does not always happen easily. When researchers use play and playful behaviors to interact with children, they will find they relate to more easily to children (Zosh et al., 2018). As noted in the response by Didi 5 years: “My educators keep me safe and play with me. If I am ‘really sad’ I can talk to them comfortable to talk to an educator.” Children express their pleasure in playing and like their interactions with the adults who play with them. In addition, play can be a tool used with children in order to get to know them and to build trust with them. Building trust creates safe spaces where children feel confident to be accepted for who they are and to express their ideas about the matters that affect them.

5.1.3. Cautions

There are alternative perspectives to gathering the voices of children. In particular, there is a consciousness that children may not want to invest time in an adult agenda such as an investigation about the qualities of the workforce. Children may be intent on participating in their own agenda of play and leisure pursuits and not prioritize the opportunity the adults give them to have a say about policy matters, such as the workforce. If researchers are to include children’s perspectives in research requires thoughtful and inventive ways to ensure the approaches meaningfully capture their voices (Mayne et al., 2018). Gibbs et al. (2018, p. 93) use the term as co-researchers to acknowledge and reflect the way in children’s contributions are made. Researchers are reminded to reflect on the research intentions of seeking children’s participation. Consideration should be given to how children perceive the relevance of research to their lives and how children’s knowledge will be used to influence practice in ways that improve their lives (Johnson et al., 2014). Children may ask how their views are being used. Researchers who engage with children should discuss with children how their views have been heard and used.

5.2. Assessing using a multilayered approach

The meaning making experiences using creative methodologies provided a process for children to express their ideas about matters that affect them. This included their perspectives on the physical and social environment, the qualities of the children’s services’ workforce and the policy and practices embedded in the functions of providing care and education for them.

The involvement of trusted educators across all stages of the project supported access to children’s perspectives of their experiences in ECEC and OSHC contexts, providing opportunities to understand more deeply what they valued (Ergler et al., 2015; McCormick, 2018; Halpenny, 2021). Using methodologies such as talking circles, dialogic drawing and visual elicitation can also positively impact developing tools to the assessing the quality of the outcomes for children in ECEC and OSHC settings. These methodologies may have also contributed to the lack of adverse comments made by the children. The use of additional prompts may have expanded the breadth of children’s comments. Knowing more about children’s expectations can help to provide a more authentic understanding of the demands of professional work and pedagogical practices.

6. Conclusion

The perspectives of children need to be highlighted in assessing quality of ECEC and OSHC settings. If adults are able to consider children’s perspectives, then it is possible that children will acquire the skill to see adults’ perspectives. The ability to understand each other’s perspectives is pivotal to the development of secure and reciprocal relationships between children and the adults who work with them and to assessing the quality of requirements for example the National Quality Framework. Acknowledging children’s perspectives are different to adults, ECEC and OSHC settings are modeling a fundamental skill that will support children to acknowledge and assess their own learning, development and wellbeing.

The update of the Australian ALFs has been a valuable opportunity to gather the voices of children to have a say on matters that affect them in policy and practice. This project used methodological tools that prioritized children’s voices for assessing the vision, pedagogies, principles underpinning practices, and learning outcomes that educators are expected to use in their daily work. The contributions of children have extended beyond just listening to their ideas. Children’s responses have provided meaningful insights about perceptions about quality, responsive environments, self-care, and relational pedagogies. This information will be invaluable to supporting ways to assess and improve the quality of settings for children.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data sets are unable to be shared. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZmF5LmhhZGxleUBtcS5lZHUuYXU=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Macquarie University Ethics Committee. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

JC, SI, LH, LB, FB-H, and FH contributed to conception and design of the study. JC, SI, LH, LB, FB-H, LL, and FH performed the statistical analysis and wrote sections of the manuscript. JC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ACECQA. (2021). Shaping our future. A ten year strategy to ensure a sustainable, high-quality children’s education and care workforce 2022–2031. Available at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-10/ShapingOurFutureChildrensEducationandCareNationalWorkforceStrategy-September2021.pdf

Arnott, L., Martinez-Lejarreta, L., Wall, K., Blaisdell, C., and Palailogou, I. (2020). Reflecting on three creative approaches to informed consent with children under six. Br. Educ. Res. J. 46, 786–810. doi: 10.1002/berj.3619

Bagnoli, A. (2009). Beyond the standard interview: the use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 9, 547–570. doi: 10.1177/1468794109343625

Barblett, L., Cartmel, J., Hadley, F., Harrison, L. J., Irvine, S., Bobongie- Harris, F., et al. (2021). National quality framework approved learning frameworks update: literature review, Australian Children’s Educations and Care Quality Authority, 1–65 Available at: https://www.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1189427/2021NQF-ALF-UpdateLiteratureReview.PDF.pdf.

Blaisdell, C., McNair, L. J., Adison, L., and Davis, J. M. (2021). ‘Why am I in all of these pictures?’ From learning stories to lived stories: the politics of Children’s participation rights in documentation practices. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. 30, 572–585. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2021.2007970

Carey, G., Malbon, E., Green, C., Reeders, D., and Marjolin, A. (2020). Quasi-market shaping, stewarding and steering in personalization: the need for practice-orientated empirical evidence. Policy Des. Pract. 3, 30–44. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2019.170498

Cartmel, J., Casley, M., and Smith, K. (2020). “Talking circles” in Health and wellbeing in childhood. eds. S. Garvis and D. Pendergast (London: Cambridge University Press), XX.

Cheeseman, S., Press, F., and Sumsion, J. (2022). “Reconceptualising Shier’s pathways to participation with infants: listening and responding to the views of infants in their encounters with curriculum,” in (Re)conceptualizing children’s rights in infant-toddler care and education. eds. F. Press and S. Cheeseman (Switzerland: Springer), 59–77.

Cohrssen, C. (2015). “Conversations with children that support responsive engagement,” in Online blog, The Spoke: Early Childhood Australia’s Blog. February 2015. Available at: http://thespoke.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/conversations-children-support-responsive- engagement/.

Coates, E., and Coates, A. (2006). Young children talking and drawing. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 14, 221–241. doi: 10.1080/09669760600879961

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K., eds. (2017). Research methods in education. (8th Edn.). London, UK: Routledge.

Dalkilic, M. (2020). “A capability oriented lens: reframing the early years education of children with disabilities,” in Disrupting and countering deficits in early childhood education. eds. F. Nxumalo and C. P. Brown (New York: Routledge), 67–82.

Doel-Mackaway, H. (2016). The participation of aboriginal children and young people in law and policy development PhD diss., Macquarie University. Research Online http://minerva.mq.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/mq:55401.

Early Childhood Australia (ECA). (2016). Early Childhood Australia’s Code of Ethics. Canberra Australia.

Education Services Australia. (2021). Shaping Our Future. A ten-year strategy to ensure a sustainable, high-quality children’s education and care workforce 2022–2031. Available at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/national-workforce-strategy

Einarsdóttir, J. (2011). Icelandic children’s early education transition experiences. Early Education and Development 22, 737–756. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2011.597027

Ergler, C., Smith, K., Kotsanas, C., and Hutchinson, C. (2015). What makes a good city in pre-schoolers’ eyes? Findings from participatory planning projects in Australia and New Zealand. J. Urban Des. 20, 461–478. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2015.1045842

Farina, F., and Scollan, A. (2019). “Introduction,” in Children’s self-determination in the context of early childhood education and services. eds. F. Farrini and A. Scollan (Switzerland: Springer), 1–22.

García-Carrión, R., Villardón-Gallego, L., Martinez-de-la-Hidalga, Z., and Marauri, J. (2020). Exploring the impact of dialogic literary gathering on students’ relationships with a communicative approach. Qual. Inq. 26, 996–1002. doi: 10.1177/1077800420938879

Gibbs, L., Marinkovic, K., Black, A. L., Gladstone, B., Dedding, C., Dadich, A., et al. (2018). “Kids in action: participatory health research with children: voices around the world,” in Participatory health research. eds. M. T. Wright and K. Kongats (Berlin: Springer), 93–113.

Halpenny, A. (2021). Capturing children’s meanings in early childhood research and practice. London: Routledge.

Harris, P., and Manatakis, H. (2013). Children’s voices: a principled framework for children and young people’s participation as valued citizens and learners Adelaide, Australia: University of South Australia in Partnership with the South Australian Department for Education and Child Development.

Harrison, L. J. (2014). “Using children’s drawings as a source of data in research” in Handbook of research methods in early childhood education. Volume II. ed. O. Saracho (Review of research methodologies. Information Age Publishing), 433–472.

Harrison, L. J., Wong, S., Press, F., Gibson, M., and Ryan, S. (2019). Understanding the Work of Australian Early Childhood Educators Using Time-Use Diary Methodology. J Res Child Educ. 33, 521–537. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2019.1644404

Hurst, B. (2021). Exploring playful participatory research with children in school age care. Int. J. Educ. Res. Ext. Educ. 9, 280–291. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v9i2.04

Irvine, S., and Farrell, A. (2013). The rise of government in early childhood education and care following the child care act 1972: the lasting legacy of the 1990s in setting the reform agenda for ECEC in Australia. Australas. J. Early Childhood 38, 99–106. doi: 10.1177/183693911303800414

Irvine, S., Thorpe, K., McDonald, P., Lunn, J., and Sumsion, J. (2016). “Money, love: initial findings from the national ECEC workforce study,” in Summary report from the national ECEC workforce development policy workshop (Brisbane, Queensland: Queensland University of Technology (QUT)).

James, A., and Prout, A.. (2015). Constructing and reconstructing childhood: contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood. (3rd Edn.). London, UK: Routledge.

Johnson, V., Hart, R., and Colwell, J., eds. (2014). Steps for engaging young children in research: the guide, Vol. 1. The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation.

Kellett, M. (2011). Empowering children and young people as researchers: overcoming barriers and building capacity. Child Indic. Res. 4, 205–219. doi: 10.1007/s12187-010-9103-1

Klerfelt, A., and Haglund, B. (2014). Walk-and-talk conversations: a way to elicit Children's perspectives and prominent discourses in school-age Educare. Int. J. Educ. Res. Ext. Educ. 2, 119–134. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v2i2.19550

Lager, K. (2016). Learning to play with new friends: systematic quality development work in a leisure-time centre. Early Child Dev. Care 186, 307–323. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2015.1030634

Lundy, L. (2018). In defense of tokenism? Implementing children’s right to participate in collective decision making. Childhood 25, 340–354. doi: 10.1177/0907568218777292

Lundy, L. (2019). A lexicon for research on international children’s rights in troubled times. Int. J. Child. Rights 27, 595–601. doi: 10.1163/15718182-02704013

Lundy, L., Welty, E., Blue Swadener, B., Blanchet Cohen, N., Smith, K., Devine, D., et al. (2015). “What if children had been involved in drafting the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child?,” in Law in Society: Reflections on Children, Families, Culture and Philosophy: Essays in Honour Michael Freeman Brill. eds. A. Diduck, N. Peleg, and H. Reece. Available at: http://www.brill.com/products/book/law-society-reflections-children-family-culture-and-philosophy.

Mayne, F., and Howitt, C. (2015). How far have we come in respecting young children in our research? A meta-analysis. Australas. J. Early Childhood 40, 30–38. doi: 10.1177/183693911504000405

Mayne, F., Howitt, C., and Rennie, L. (2018). A hierarchical model of children’s research participation rights based on information, understanding, voice, and influence. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 26, 644–656. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2018.1522480

McCormick, K. (2018). Mosaic of care: preschool children’s caring expressions and enactments. J. Early Child. Res. 16, 378–392. doi: 10.1177/1476718X18809388

McDonald, P., Thorpe, K., and Irvine, S. (2018). Low pay but still we stay: retention in early childhood education and care. J. Ind. Relat. 60, 647–668. doi: 10.1177/0022185618800351

Merriman, B., and Guerin, S. (2006). Using children’s drawings as data in child-centred research. Ir. J. Psychol. 27, 48–57. doi: 10.1080/03033910.2006.10446227

National Quality Framework (NQF) (2021). Snapshot Q4 2021. Australian Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). Available at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-02/NQF%20Snapshot%20Q4%202021.PDF.

Nicholson, J., Kurnik, J., Jevgjovikj, M., and Ufoegbune, V. (2015). Deconstructing adults’ and Children’s discourse on play: listening to children’s voices to destabilise deficit narratives. Early Child Dev. Care 185, 1569–1586. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2015.1011149

Nolas, S. M. (2015). Children’s participation, childhood publics and social change: A review, Children & Society. 29, 157–167. doi: 10.111/chso.12108

Noonan, R. J., Boddy, L. M., Fairclough, S. J., and Knowles, Z. (2016). Write, draw, show, and tell: a child-Centred dual methodology to explore perceptions of out-of-school physical activity. BMC Public Health 16:326. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3005-1

Orr, E. R., Ballantyne, M., Gonzalez, A., and Jack, S. M. (2020). Visual elicitation: methods for enhancing the quality and depth of interview data in applied qualitative Health Research. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 43, 202–213. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000321

Parsons, S., Kovshoff, H., Karakosta, E., and Ivil, K. (2021). Understanding holistic and unique childhoods: knowledge generation in the early years with autistic children, families and practitioners. Early Years 43, 15–30. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2021.1889992

Press, F., Harrison, L. J., Wong, S., Gibson, M., Ryan, S., and Cumming, T. (2020). The hidden complexity of early childhood educators’ work: the exemplary early childhood educators at work study. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 21, 172–175. doi: 10.1177/1463949120931986

Pyle, A. (2013). Engaging young children in research through photo elicitation. Early Child Dev. Care 183, 1544–1558. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2012.733944

Quennerstedt, A. (2014). Researching Children’s rights in education: sociology of childhood encountering educational theory. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 35, 115–132. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2013.783962

Quinn, S., and Manning, J. (2013). Recognising the ethical implications of the use of photography in early childhood educational settings. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 14, 270–278. doi: 10.2304/ciec.2013.14.3.270

Ruscoe, A. (2021). “Power, perspective and affordance in early childhood education.” Unpublished PhD diss., Edith Cowan University. Available at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/2490

Schumacher, A. (2014). Talking circles for adolescent girls in an urban high school: a restorative practices program for building friendships and developing emotional literacy skills. SAGE Open 4:2158244014554204. doi: 10.1177/2158244014554204

Shaw, P. A. (2021). Photo-elicitation and photo-voice: using visual methodological tools to engage with younger children’s voices about inclusion in education. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 44, 337–351. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2020.1755248

Smith, A. B. (2013). Understanding children and childhood: A New Zealand perspective : Bridget Williams Books.

Smith, K., and Coady, M. M. (2020). “Rethinking informed consent with children under the age of three,” in Ethics and research with young children: new perspectives. ed. C. M. Schulte (London: Bloomsbury Academic), 9–21.

Trevarthen, C., Delafield-Butt, J., and Dunlop, A. W.. (2018). The Child’s curriculum: understanding the natural talents of young children, allowing rich holistic learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vermeer, H. J., Harriet, J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Cárcamo, R. A., and Harrison, L. J. (2016). Quality of child care using the environment rating scales: a meta-analysis of international studies. Int. J. Early Child. 48, 33–60. doi: 10.1007/s13158-015-0154-9

Warming, H. (2019). Trust and power dynamics in children’s lived citizenship and participation: the case of public schools and social work in Denmark. Child. Soc. 33, 333–346. doi: 10.111/choo.12311

Wright, S. (2007). Graphic-narrative play: young Children’s authoring through drawing and ‘telling’: analogies to filmic textual features. Int. J. Educ. Arts 8, 1–28.

Keywords: children, children’s voices, education and care, workforce, relationships

Citation: Cartmel J, Irvine S, Harrison L, Barblett L, Bobongie-Harris F, Lavina L and Hadley F (2023) Conceptualising the education and care workforce from the perspective of children and young people. Front. Educ. 8:1167486. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1167486

Edited by:

Nelly Lagos San Martín, University of the Bío Bío, ChileReviewed by:

Karin Lager, University of Gothenburg, SwedenCaroline Cohrssen, University of New England, Australia

Sharinaz Hassan, Curtin University, Australia

Kolbrun Palsdottir, University of Iceland, Iceland

Copyright © 2023 Cartmel, Irvine, Harrison, Barblett, Bobongie-Harris, Lavina and Hadley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Cartmel, ai5jYXJ0bWVsQGdyaWZmaXRoLmVkdS5hdQ==

Jennifer Cartmel

Jennifer Cartmel Susan Irvine

Susan Irvine Linda Harrison3

Linda Harrison3 Lennie Barblett

Lennie Barblett Francis Bobongie-Harris

Francis Bobongie-Harris Leanne Lavina

Leanne Lavina Fay Hadley

Fay Hadley