94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 02 June 2023

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1165746

This article is part of the Research TopicTeaching Wellbeing in Higher EducationView all 6 articles

Introduction: Immigrant and refugee children face multiple challenges in accessing education. To help facilitate the educational success and wellbeing of these children, teachers need to have self-efficacy in creating a supportive learning environment for them.

Methods: Based on a set of highly interconnected competences identified through a literature review and empirical research, the study developed a measurement instrument to assess teachers' generalized perceived self-efficacy in the domain of working with refugee children: the Newcomer's Teacher's Self-Efficacy (NTSE) scale. The scale was tested for validity and internal consistency with 154 practicing and prospective teachers enrolled at three different teacher education institutions in Belgium and the Netherlands, 42 of whom also underwent newcomer education courses.

Results: The study examined the factorability, reliability, and validity of the NTSE scale and showed that the scale is reliable (a = 0.97) and has good convergent and criterion validity. The results also demonstrated that participation in a study module for newcomer educators corresponded with an increase in partakers' NTSE scores, and the extent of the module was related to the degree of increase.

Discussion: The proposed scale performed well in the context where it was tested, but further international research is needed to determine its generalizability to different countries and time frames.

In 2021, 36.5 million children were displaced from their homes (UN News, 2022). In recent years, the EU recorded between 120,000 and 350,000 children as first-time asylum applicants per year (Eurostat, 2022). This year, the number is expected to grow substantially due to the war in Ukraine. As stipulated in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, 1989), access to education is a right of all children, including refugee children. Moreover, the education of displaced children can provide the knowledge and skills to rebuild their lives and give them a chance for a prosperous, peaceful future (Dooley, 2017).

In general, 8% of the children in the EU are non-nationals (Eurostat, 2021) and the situation of these migrant children depends, to a large degree, on the school policy and the teachers with whom they interact. Immigrant children and refugee children among them tend to lag behind their native peers in educational attainment. For instance, in the EU, 38% of non-EU-born individuals over 25 years old did not exceed lower secondary education, in comparison to 28% of the native-born population and 20% of the EU-born population (Eurostat, 2023). In the Netherlands, for instance, newcomer students are three times more likely to be directed to lower forms of secondary education than other primary school graduates (Dutch Inspectorate of Education, 2020). Immigrant children who have good cognitive capacity but do not possess a good command of the host country's language can be directed to the lowest forms of vocational education, aimed at pupils with learning difficulties. This disadvantage further extends to their position in the job market, with non-EU-born migrants aged between 15 and 29 being two times more likely to be neither in employment nor in education, compared to the native-born population (Eurostat, 2023). First-generation immigrant students in the EU also experience lower life satisfaction and a sense of belonging at the school than their native counterparts (Cerna et al., 2021).

There are particular barriers faced by refugee children that need to be taken into consideration to improve their educational prospects, e.g., language difficulties, personal trauma, and cultural differences (Crul et al., 2016). To facilitate refugee children reaching their full potential and wellbeing, education institutions must be prepared to meet their needs (Pinson and Arnot, 2007). The situation of the migrant children depends, to a large degree, on institutional arrangements and school policy. However, the teachers also play an essential role, as they interpret and implement mandated policies (Hos and Kaplan-Wolff, 2020), and they directly influence the development of a child as well as the school climate and practices. Therefore, in addition to systemic institutional solutions, teachers in the field should be able and willing to overcome challenges and create new environments facilitating the educational success of newcomer children. Teachers' persistence and teaching performance, as well as their students' outcomes, were demonstrated in multiple studies to be related to teachers' self-efficacy (Caprara et al., 2006; Klassen and Tze, 2014; Kim and Seo, 2018). Teachers in the field, however, often do not feel qualified to meet the needs of immigrant children in their classroom (Evans et al., 2022), as demonstrated by qualitative studies sampling the experiences of in-service and pre-service teachers of refugees in preferred destination Western countries such as the USA, Canada, Sweden, and Croatia. School staff often feel that they lack the skills for working with refugee children (Levi, 2019; Vrdoljak et al., 2022); feel not prepared to address the emotional stress experienced by refugee children (Szente et al., 2006); are unable to teach children who have limited command of the host country's language (Siwatu, 2007; Svensson, 2019); and are afraid that they may say something to their refugee students that might lead to cultural misunderstandings or trigger traumatic memories (McBrien, 2005).

Perceived lack of knowledge and self-efficacy in the domain of working with refugees can generate avoidance of refugee students by their teachers, as demonstrated in some studies (Roxas, 2011). Engaging with refugee children requires that teachers believe they have the necessary capacities that are crucial for it. Teachers who lack a sense of mastery in these capacities can distance themselves and avoid refugee students. The belief people have concerning their capability to set a course of action and complete a task within a situation has been described as self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986, 1997). According to those theories, self-efficacy is an important determinant of an individual's behavior, as it influences the belief that one can succeed at a task and meet expectations. Someone's self-efficacy belief, therefore, affects their motivation, the effort put into the task, the choices made when completing the task, their persistence in the face of difficulties (Bandura, 1977, 1997), and eventually their performance (Peeler and Jane, 2005). Empirical studies confirm the influence of self-efficacy on motivation and effort in numerous areas, academic performance being one (Caprara et al., 2011). Self-efficacy is also an excellent predictor of individual behavior (Goddard et al., 2000). In the context of education, teachers' self-efficacy concerns their belief about possessing the capacity to bring about the desired outcomes of student engagement and learning (Bandura, 1977). Following the theory of self-efficacy, teachers possessing self-efficacy in the relevant domain are expected to put more effort into their teaching, persevere despite difficulties, and employ effective strategies (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2007). Studies have also confirmed that teachers' self-efficacy not only affects their behavior but also indirectly impacts their students' performance (e.g., Knoblauch and Hoy, 2008).

The current article aimed to offer a measurement instrument for self-efficacy beliefs in the realm of teaching displaced children, in particular, refugees. Instruments focused on actual competences such as knowledge, skills, and attitudes do not take into consideration perceived self-efficacy (Caprara et al., 2009), while perceptions of efficacy are critical determinants of how people behave (Bandura, 1997). Teachers' self-efficacy is said to be specific to the particular settings, subjects, and students (Goddard et al., 2000). Therefore, there is a need to measure the self-efficacy of teachers in the domain of teaching displaced children as a separate construct from a general teacher's self-efficacy. Studies demonstrated the potential predictive relevance of such specific measures in related domains; for instance, self-efficacy in the area of teaching children with limited host country language command is related to positive attitudes toward such students (Karabenick and Clemens Noda, 2004). An international study carried out in England, Italy, the Netherlands, and Poland showed that teachers' diversity-related self-efficacy was related to intercultural classroom practices employed by participating teachers (Romijn et al., 2020). Since teachers' self-efficacy in the specific domain of teaching displaced children can affect their ability to meet the needs of refugee students, it is important to establish what are the essential competences constituting it.

Refugee students face distinctive sets of educational, linguistic, and social challenges and the need to successfully integrate (McBrien, 2005; Vrdoljak et al., 2022). Therefore, a particular set of competences is required by teachers to support displaced children, determined by these needs and barriers faced by displaced children. These challenges may include limited command of the host country's language, personal trauma, and cultural differences (Crul et al., 2016). A literature review revealed five partially overlapping domains of challenges requiring teachers of displaced students to have the competence to adequately respond: (a) language barrier, (b) cultural barriers, (c) situational factors affecting students, (d) barriers to parental involvement, and (e) socio-emotional vulnerability.

There is often a language barrier between newcomer students and their teachers (Szente et al., 2006; Crul et al., 2016). Some students do not have sufficient command of the host country's language due to an insufficient number of hours dedicated to language learning (Vrdoljak et al., 2022). This requires teachers to (a) support efficient acquisition of the new language (Walker-Dalhouse et al., 2009) and (b) teach subject matters to students with limited language fluency. On the most fundamental level, to teach effectively, teachers have to assure that students understand what they convey and what is expected (Petersen, 2017; Vrdoljak et al., 2022), but teachers also need to understand students (Gözpinar, 2019). For effective communication with students with limited fluency in the host country's language, teachers need communicative competence in the context of a multilingual setting (Peko et al., 2010; Gözpinar, 2019). This may include non-verbal communicative competence, active listening, the ability to interpret feedback from students to confirm their understanding (Alptekin, 2002), knowledge of the languages of the countries of origin of students (Peko et al., 2010), and the capacity to use translators and translation tools in the class (Gözpinar, 2019).

In addition to the language barrier, refugees, and many other immigrants share the challenge of adapting to a new culture. Researchers have suggested that teachers' abilities to recognize and respect cultural differences are important for the academic success of refugee students (McBrien, 2005), as cultural competence is necessary to understand diverse students in the classroom and identify their needs (Milner, 2011), and that culturally responsive teaching strategies can support refugee learning (Strekalova and Hoot, 2008; Leeman and van Koeven, 2019; Bennouna et al., 2021).

Some scholars postulate that knowing students' cultural backgrounds might be a necessary condition to respond successfully to diverse learners (Kanu, 2008) as it allows teachers to adapt their instructional practices accordingly, as well as understand students' perspectives and communication styles, respond more appropriately, and avoid misunderstandings (Milner, 2011). Successful teachers can also potentially bring intercultural understanding across to help students to establish positive relationships with each other (Milner, 2011; Walsh and Townsin, 2015). This competency also involves not only knowledge of the students but also awareness of the teacher's cultural assumptions and biases. As the content of specific cultural knowledge needed varies between students, universal competence of a critical and open-minded attitude can be of great relevance for an overall teacher's competence to work in classrooms with diverse students, including refugees (Milner, 2011; Roxas, 2011; Kopish, 2016).

Teachers possessing appropriate intercultural competence can take cultural diversity in their classroom into account, and accordingly adjust and adapt their classroom management, teaching materials, or instructions (Milner, 2011; Kopish, 2016; Gözpinar, 2019) to take into account individual differences between children's learning and communication styles, as affected by their cultural background (Kopish, 2016; Petersen, 2017). They also can fine-tune assessment so it is appropriate and fair for all students, irrespective of their cultural background (Szente et al., 2006; Petersen, 2017).

Another barrier shared by displaced children and other students with a migration background is their current and previous objective situation, though its gravity might be heavier for refugees than for other migrants. Refugees have a different education history compared to regular students (Stevenson and Willott, 2007), often involving interruptions in schooling (d'Abreu et al., 2019) which can even extend to minimal experience with formal schooling (Kirova, 2001). The discrepancy in educational history creates gaps in knowledge among refugee students in comparison to what is assumed (Vrdoljak et al., 2022). In addition to their past situation, a refugee's present situation should be taken into consideration as well. For instance, refugees often have unstable living and family situations (Stevenson and Willott, 2007), accompanied by uncertainty regarding how long they can stay in their current place as well as a lack of financial resources and support (Lucas, 1997).

Teachers have often little awareness of the nature of their refugee students' backgrounds (Goodwin, 2002) and might not know about the experiences of refugees in their classrooms or are even unaware that they have refugee students (McBrien, 2005). Authors argue that there is a critical need for teachers to better understand the lives of their refugee students (Roxas, 2010) and that such understanding should make them more committed to assist refugee students (Strekalova and Hoot, 2008). This can also further help to foster a postulated individualized approach to education that takes into account the different needs and experiences of every child (Hek, 2005; Kanu, 2008; Roxas, 2010).

The same set of conditions that affect students directly (objective conditions, language, and cultural barriers) are also affecting them indirectly, through their parents. These conditions often limit parental involvement in their child's education (Rah et al., 2009; Gandarilla Ocampo et al., 2022). Newcomer parents face challenges such as objective hardship (Vrdoljak et al., 2022), lack of stable jobs, incomes, or housing, and limited mobility and available time (Bennouna et al., 2021). Language and cultural barriers can often prevent parents and teachers from understanding each other (Trueba et al., 1990; Peko et al., 2010) or other parents (Kopish, 2016), or even cause them to avoid each other (Gandarilla Ocampo et al., 2022). In addition, newcomer parents lack an understanding of the intricacies of the host country's educational system (Gandarilla Ocampo et al., 2022; Vrdoljak et al., 2022).

Parents and parental involvement are important factors in immigrant students' success (Portes and Rumbaut, 2001). Parents can help structure their children's studies, but without their support, children have to bear their responsibilities alone (Denessen et al., 2010). It is possible to establish positive parent–teacher relationships with newcomer parents for the benefit of students' educational growth (Bennouna et al., 2021). The same communicative competences required for supporting students (Peko et al., 2010; Kopish, 2016) can help school staff achieve such a relationship with newcomer parents, possibly engaging a larger newcomer community in the process as well (Bennouna et al., 2021).

Displacement and past traumatic experiences (McBrien, 2005; Roxas, 2011) can affect refugee children's school performance and psychosocial wellbeing, as these students may continue to suffer from mental health consequences of prior adverse life events (Bennouna et al., 2020; Stark et al., 2021) and experience anxiety, depression, and a sense of isolation (Ukasoanya, 2014; Asad and Kay, 2015; d'Abreu et al., 2019). Students who have experienced such events may also find it hard to build relationships (Crul et al., 2016) and may feel insecure (Roxas, 2011). Positive relationships with teachers and peers can provide social support and make it easier to obtain assistance with learning tasks. Therefore, difficulties in building such positive relations can also worsen school performance (Szente et al., 2006). Pre-existing psychological issues may be further exacerbated by acculturative stress, experiences of being discriminated against by the host community, and conflicting demands of cultural norms (Castro-Olivo and Merrell, 2012).

To be able to overcome any of these difficulties, teachers should make sure that a classroom is a safe environment. In such environments, students can express themselves and learn about the new country (Gözpinar, 2019). Safe classrooms also foster positive intergroup contact and prevent negative intergroup behaviors (Vrdoljak et al., 2022). To this end, teachers should be capable of stimulating the formation of trusting relationships among students, recognizing existing relationships between students, and being able to moderate and stimulate these relationships (Zins and Elias, 2006).

In addition to assuring a positive classroom climate, refugees' teachers may be expected to fulfill the roles of psychological counselors, social workers, and life coaches for their students (Kanu, 2008). Providing social and emotional support in schools can be seen as a necessary condition for newcomer children to realize their human right to education (Evans et al., 2022). These types of support require not only classroom communicative and management skills but also an empathic attitude (Southern, 2007) and social–emotional skills related to social identity and relationship building (Bennouna et al., 2021). To make students feel safe and understood, teachers should be able to listen to their pupils' stories with compassion and react without avoidance, shock, or aversion (Szente et al., 2006; Gözpinar, 2019).

In summary, to successfully fulfill the educational needs of refugee children, teachers need a set of intertwined competences: (a) competency to stimulate and foster country language acquisition; (b) communication competence necessary not only to understand and be understood but also to engage and build relationships with students and their parents who may have limited command of the host country language; (c) social–emotional competences for the same reason and further to help emotionally vulnerable students to cope and to create a safe learning environment for them as well as foster their social–emotional development; (d) cultural competency open-mindedness and flexibility to be able to adapt teaching style, materials, and activities and foster the aforementioned relationships; and (e) be able and willing to learn about situational factors affecting their students and take them into account.

Although presented here as separate categories, these competences are highly interconnected and overlap to a large degree. Moreover, their specific content is highly dependent on the particular context. Refugee students are not a homogenous group and differ fundamentally in terms of their specific needs (Hek, 2005). Groups of refugees with divergent backgrounds will face different barriers, as each individual has their unique history and situation. In addition, the institutional context may place very different demands on the teachers of refugees, as the school system, for instance, may provide different amounts of language support and instruction, thus affecting expectations concerning teachers in this regard.

In this light, generalized competence and self-efficacy with regard to being a teacher of refugee children may be of greater relevance than specific skills. By necessity, formal assessment at teacher preparation institutions is focused on specific knowledge, skills, and capacities rather than on perceived self-efficacy and a sense of control. However, these perceptions may be actual determinants of how teachers behave in a classroom (Bandura, 1997).

Teachers in the field often feel they are not qualified to meet the needs of refugee children. There is a plethora of studies on the education of migrants, but much fewer studies concerning refugee students, despite their situation being more challenging (McBrien, 2005; Bloch et al., 2015). Moreover, the research into teachers' competences in the context of refugee education mostly consists of qualitative case studies (Dryden-Peterson, 2017). The limited research into teacher self-efficacy in relation to working specifically with refugee students usually focuses on one specific competency, for instance, multicultural self-efficacy (Sleeter, 2001; Guyton and Wesche, 2005). There is a need for research focusing on the general self-efficacy of teachers in the domain of refugee education. To support overcoming the deficiency in this area, in this study, we propose a questionnaire instrument to assess teachers' generalized perceived self-efficacy in the domain of working with refugee children, which should be suitable for large-scale quantitative studies and applicable across different institutional and national contexts.

First, the initial domain of competences was established by a systematic literature review utilizing predefined keyword searches on Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) and PsycINFO databases, which revealed 19 publications meeting the inclusion criteria, released after 2000, and discussing challenges faced by refugee students and the teachers' competences required to overcome them. To confirm the relevance of the established domain in the context of the Netherlands, Belgium, and the UK, a string of small-scale empirical research was conducted, consisting of a selective inductive content analysis based on meaningful phrases related to the teacher's competence, as found in: (a) standardized moderator reports from learning communities meetings at 20 locations across these three countries, with 2–8 meetings at each location bringing together refugee parents, students, and teachers, (b) a focus group interview with seven teachers experienced in educating newcomers in the Netherlands, (c) a series of 12 interviews with stakeholders involved in refugee education, and (d) a small survey study of 17 Dutch teachers from ethnically diverse schools, which receive interns seeking to gain experience in newcomer education (SIREE, 2021; Sklad et al., 2021).

The empirical results confirmed the indications from the literature review and led to the formulation of nine concrete competences using the Delphi method, involving eight Dutch and Belgian experts responsible for setting up newcomers' teacher education modules. The competences were translated into learning objectives (see Table 1) in setting up university courses and in the creation of a self-efficacy measurement tool, the Newcomer's Teacher's Self-Efficacy (NTSE) scale. Finally, following Bandura's guidelines for constructing self-efficacy scales (Bandura, 2006), 18 items of the scale corresponding to the identified competences were then constructed with the use of the Delphi method to assure face validity.

To test the validity and internal consistency, several tests were conducted. First, an exploratory factor analysis of the NTSE items was conducted, followed by correlational analyses to establish convergent and criterion validities, and finally, teachers who took part in newcomer education courses were compared to the control group in their results on the NTSE.

At three different teacher education institutions in Belgium and the Netherlands: In Holland, Hogeschool Utrecht, and VIVES, 154 students completed the NTSE scale. In addition, all participants filled in pre-existing validated scales measuring a related construct: the Culturally Responsive Teaching Self-Efficacy Scale (CRTSE; Siwatu, 2007). In general, 42 teachers and prospective teachers from both countries who completed the scales also took the newcomers' education learning modules, utilizing the nine objectives before completing the self-efficacy instruments. For 19 of the teachers from the Netherlands, we were in possession of the data grading rubrics in which their course work was evaluated with respect to the degree to which it demonstrated mastery of the nine competences constituting the foundation of the measure and learning objectives of the course.

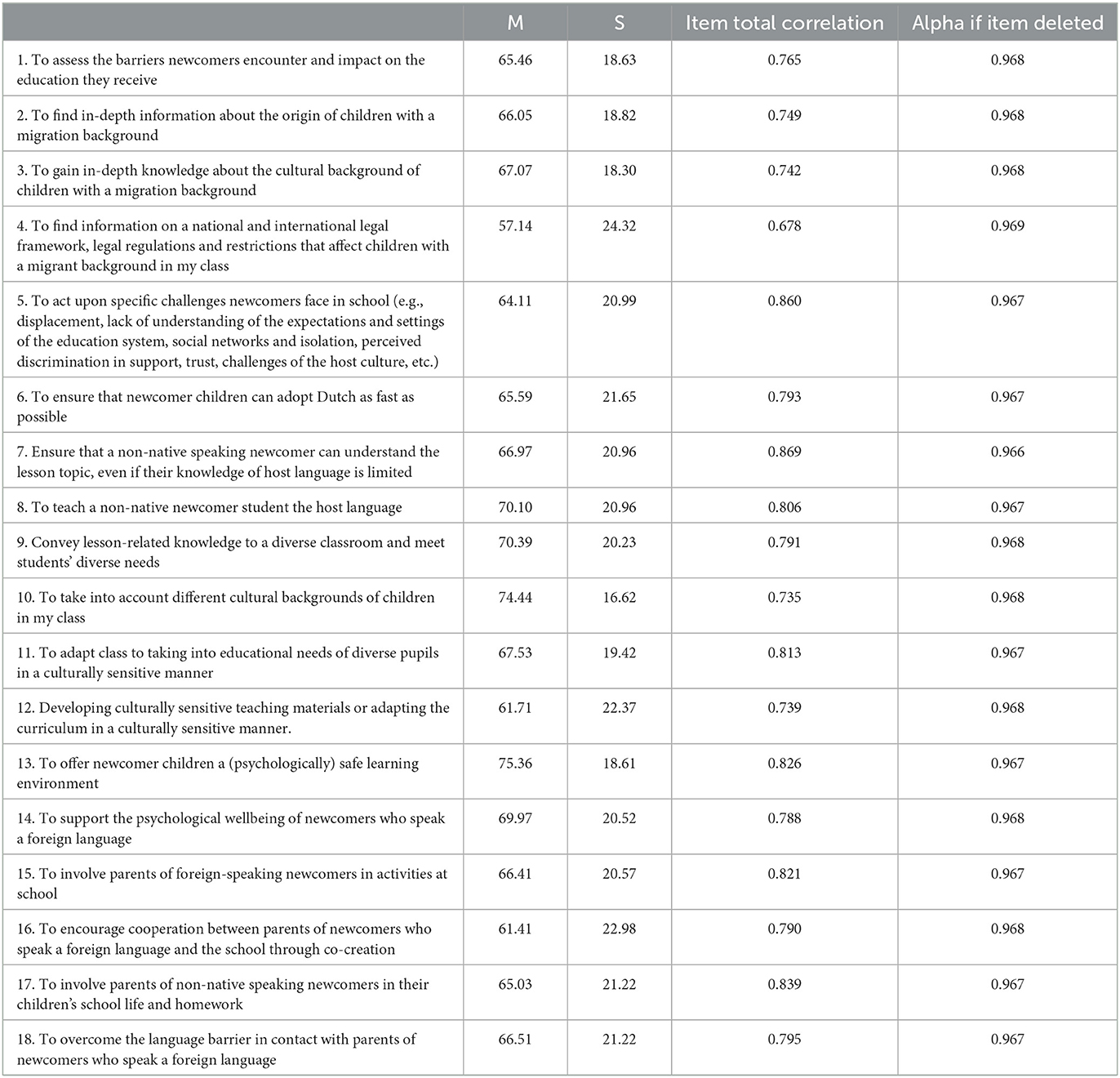

The NTSE scale consisted of 18 self-report items measuring self-efficacy in the domain of newcomer education. For each of the 18 items, respondents were asked to rate their confidence in their ability in a given area on a scale ranging from 0 (no confidence at all) to 100 (complete confidence). For the item wording, consult Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of NTSE items, including item-total correlations and reliability of the scale with items removed (N = 152).

The CRTSE (Siwatu, 2007) is a 40-item Likert-type scale that measures the self-efficacy of pre-service teachers in executing teaching practices adopted by culturally responsive teachers. It captures part of the construct of interest of NTSE, particularly the domain related to cultural competence.

Meeting the learning objectives was measured by a behavioral rubric, applied during the courses on the newcomer's education course by the instructors to evaluate whether the work of the students demonstrated the mastery of each of the nine learning objectives.

Participating teachers (in education) completed the self-efficacy scales at their convenience using an online questionnaire; the link was provided to them by their instructors. A standard protocol for administering the questionnaire was used.

The minimum amount of data for factor analysis was satisfied (Barrett and Kline, 1981) with a final sample size of 152 (using list-wise deletion), providing a ratio of 8.44 cases per variable. The factorability of the NTSE items was confirmed by several criteria.

All items correlated at least 0.4 with all other items. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.93, well above the recommended value of 0.6. Moreover, Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant [Chi2(153) = 3189.51, p < 0.001]. For each variable, the communalities were above 0.7, thus confirming that each item shared a common variance (see Table 2), and measures of sampling adequacy were above 0.87 for each of them. In light of the above, all 18 items were considered suitable for factor analysis.

A principal component analysis was used. An exploratory factor analysis revealed the unidimensionality of the NTSE. Initial eigenvalues indicated that the first four factors explained 66, 7, 5, and 5% of the variance, respectively. The second factor had an eigenvalue of just over one (1.2) and explained only 7% of the variance. Solutions for two and four components, using varimax and oblimin rotations, were inspected. A unidimensional solution was preferred because eigenvalues “leveled off” after the first component, which explained the majority of items' variance.

The instrument showed outstanding internal consistency. The internal consistency of the scale was examined using Cronbach's alpha. The alpha was excellent, at 0.97, and no increases in alpha could have been achieved by removing any of the 18 items (Table 2). The composite score was created as the average of the items, with higher scores indicating more self-efficacy, with the theoretical maximum score of 100 corresponding to perfect confidence in one's capacity and a score of 0 corresponding to an absolute lack of it.

The score distribution (see Table 3) was slightly negatively skewed leptokurtic. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 4. The skewness and kurtosis were well within a tolerable range, and assuming a normal distribution, an examination of the histograms suggested that the distribution was approximately normal. An approximately normal distribution was evident for the composite score data in the current study; thus, the scale is well-suited for parametric statistical analyses.

The NTSE scale showed good convergent construct validity. It had a strong statistically significant correlation with the CRTSE score (Siwatu, 2007): r = 0.838, p < 0.001.

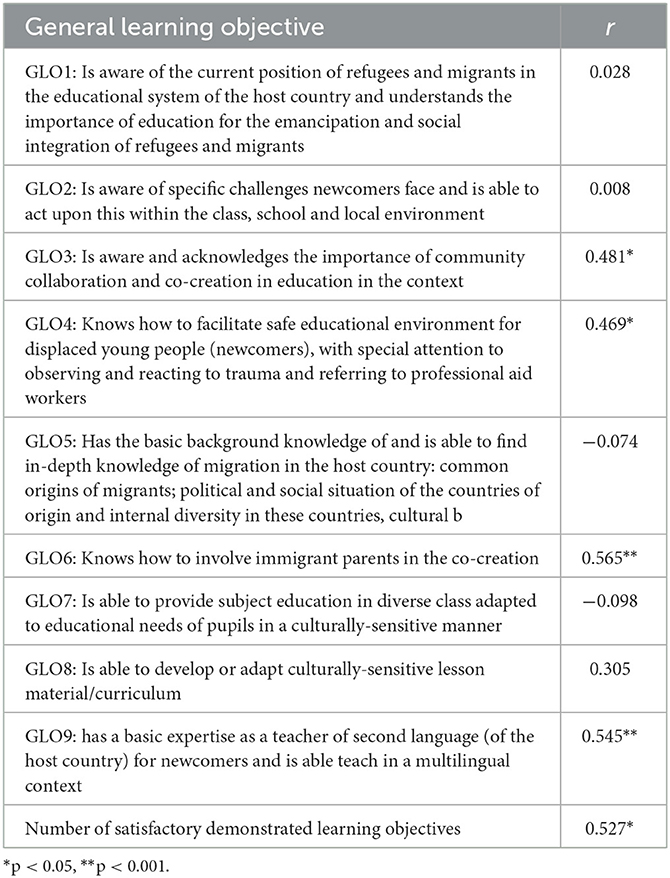

The criterion validity of the scale was further confirmed by the data from participants who participated in the academic course module preparing them for teaching newcomer children. The NTSE score correlated well with the number of learning objectives demonstrated by students' work with r = 0.53, p = 0.01. The score was particularly well-related to demonstrating competency in working with parents, facilitating a safe educational environment, and teaching language and awareness of community collaboration. At the same time, scores were not substantially correlated with demonstrating awareness and knowledge of position, challenges of migrants, and migration in the host country, nor demonstrating the capacity to provide subject classes in a culturally sensitive way (see Table 5).

Table 5. Correlations of NTSE score with demonstrating mastery of general learning objectives of the newcomers' education course.

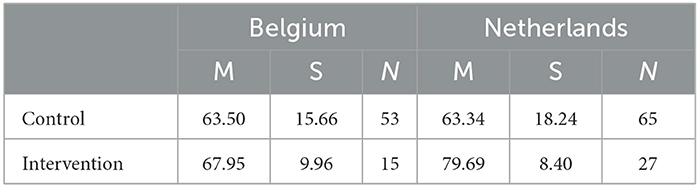

Finally, to further confirm criterion validity and establish if NTSE can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, scores from 42 participants who took the newcomers' teachers' education course module were compared on their NTSE scores to those of control participants. In addition to the presence of the course, the institutional context was taken into account, as the newcomer's education module provided to participants in Belgium was shorter and had a narrower scope than the one offered in the Netherlands.

There was a significant main effect of participating in the module on the NTSE score, F(1,153) = 13.13, p < 0.001, eta2= 0.08. There was also a significant interaction between the intervention effect and the country, F(1,153) = 13.13, p < 0.05, eta2= 0.03. In the control condition, teachers in preparation did not differ between the countries. However, the teachers from the Netherlands who took part in the more extensive educational module showed a greater increase in their NTSE score than their Belgian counterparts who participated in a less extensive module (see Table 6).

Table 6. Means and standard deviations of NTSE score among teachers participating in the newcomers' education modules and control groups in the Netherlands and Belgium.

The study proposed a scale to measure teachers' self-efficacy in the domain of teaching and supporting the wellbeing of refugee children meant for practicing and pre-service teachers, which is very relevant for teachers in many countries at this time. Correlations with other self-efficacy indicators and behavioral measures supported the validity of the scale. The scale showed good psychometric properties and internal consistency, which were further supported by its unidimensionality, despite the broad domain of competence it encompasses. We assured that all relevant competence aspects were represented in the scale, which makes this a valuable tool for future researchers interested in measuring the construct as pre-existing tools (e.g., Siwatu, 2007) focused only on specific parts of this domain.

The above study was carried out in the Netherlands and Belgium with input from the UK in the context of the second decade of the 21st century, which determines the characteristics of school systems, teachers, and the refugees with whom they work. We do not know to what extent the findings are generalizable to different countries and time frames. Therefore, further international research should be carried out both for the sake of generalizability as well as to allow for international comparisons of teachers' self-efficacy in the domain of supporting the education and wellbeing of displaced and newcomer children.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The original study was partially funded by the SIREE project within the Interreg 2 Seas Program 2014–2020 co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund under subsidy contract no. SIREE 2S03-035.

The author would like to thank and acknowledge: Ria Goedhart, Miranda Poeze, Stefan Dewitte, Els, Vanobberghen, and Anne Eikelboom for their contributions to the development of the learning objectives, for developing and teaching teacher education modules used in this study, for providing support with the data collection, and for consulting the items of the NTSE scale; Lianne Van der Looij for her contribution to the review of barriers and competences; Margje Camps and Isa Boere for their editorial support; and all the members of the SIREE project team for supporting the process in multiple ways.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alptekin, C. (2002). Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT J. 56, 57–64. doi: 10.1093/elt/56.1.57

Asad, A. L., and Kay, T. (2015). Toward a multidimensional understanding of culture for health interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 144, 79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.013

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (2006). “Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales,” in Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, Vol. 5, eds F. Pajares and T. Urdan (Information Age Publishing), 307–337.

Barrett, P. T., and Kline, P. (1981). The observation to variable ratio in factor analysis. Pers. Study Group Behav. Personality Study & Group Behaviour. 1, 23–33.

Bennouna, C., Brumbaum, H., McLay, M. M., Allaf, C., Wessells, M., and Stark, L. (2021). The role of culturally responsive social and emotional learning in supporting refugee inclusion and belonging: a thematic analysis of service provider perspectives. PLoS ONE 16, e0256743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256743

Bennouna, C., Stark, L., and Wessells, M. G. (2020). “Children and adolescents in conflict and displacement,” in Child, Adolescent and Family Refugee Mental Health (Cham: Springer), 17–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-45278-0_2

Bloch, A., Chimienti, M., Counilh, A. L., Hirsch, S., Tattolo, G., Ossipow, L., et al. (2015). The Children of Refugees in Europe: Aspirations, Social and Economic Lives, Identity and Transnational Linkages. Geneva: Centre de recherches sociales (CERES).

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., and Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers' self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students' academic achievement: a study at the school level. J. Sch. Psychol. 44, 473–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.001

Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., Alessandri, G., Gerbino, M., and Barbaranelli, C. (2011). The contribution of personality traits and self-efficacy beliefs to academic achievement: a longitudinal study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 78–96. doi: 10.1348/2044-8279.002004

Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., Capanna, C., and Mebane, M. (2009). Perceived political self-efficacy: theory, assessment, and applications. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 1002–1020. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.604

Castro-Olivo, S. M., and Merrell, K. W. (2012). Validating cultural adaptations of a school-based social-emotional learning programme for use with Latino immigrant adolescents. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 5, 78–92. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2012.689193

Cerna, L., Brussino, O., and Mezzanotte, C. (2021). The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background: an Update with PISA 2018. OECD Education Working Paper No. 261. Paris: Publishing.

Crul, M., Keskiner, E., Schneider, J., Lelie, F., and Ghaeminia, S. (2016). No Lost Generation? Education for Refugee Children. A Comparison Between Sweden, Germany, The Netherlands and Turkey. The Integration of Migrants and refugees. Florence: European University Institute.

d'Abreu, A., Castro-Olivo, S., and Ura, S. K. (2019). Understanding the role of acculturative stress on refugee youth mental health: a systematic review and ecological approach to assessment and intervention. Sch. Psychol. Int. 40, 107–127. doi: 10.1177/0143034318822688

Denessen, E. J. P. G., Bakker, J. T. A., Kloppenburg, H. L., and Kerkhof, M. (2010). Teacher-parent partnerships: preservice teacher competences and attitudes during teacher training in the Netherlands. Int. J. Parents Educ. 3, 29–36. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/2066/90375

Dooley, T. (2017). Education Uprooted: For Every Migrant, Refugee and Displaced Child, Education. New York, NY: UNICEF.

Dryden-Peterson, S. (2017). Refugee education: EDUCATION for an unknowable future. Curric. Inquiry 47, 14–24. doi: 10.1080/03626784.2016.1255935

Dutch Inspectorate of Education. (2020). The State of Education in the Netherlands 2020. Available online at: https://english.onderwijsinspectie.nl/documents/annual-reports/2020/04/22/the-state-of-education-in-the-netherlands-2020 (accessed May 12, 2023).

Eurostat (2021). 8% of the Children in the EU Are Non-National. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20211217-1 (accessed April 29, 2022).

Eurostat (2022). Children in Migration - Asylum Applicants. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Children_in_migration_-_asylum_applicants (accessed April 29, 2022).

Eurostat. (2023). Population by Educational Attainment Level, Sex, Age and Country of Birth (%). Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/EDAT_LFS_9912__custom_6183047/default/table?lang=en (accessed May 12, 2023).

Evans, K., Oliveira, G., Hason III, R. G., Crea, T. M., Neville, S. E., and Fitchett, V. (2022). Unaccompanied children's education in the United States: Service provider's perspective on challenges and support strategies. Cultura, Educación y Sociedad. 13, 193–218. doi: 10.17981/cultedusoc.13.1.2022.12

Gandarilla Ocampo, M., Bennouna, C., Seff, I., Wessells, M., Robinson, M. V., Allaf, C., et al. (2022). We are here for the future of our kids: parental involvement in refugee adolescents' educational endeavours in the United States. J. Refug. Stud. 34, 4300–4321. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feaa106

Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., and Hoy, A. W. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 37, 479–507. doi: 10.3102/00028312037002479

Goodwin, L. (2002). Teacher preparation and the education of immigrant children. Educ. Urban Soc. 34, 156–172 doi: 10.1177/0013124502034002003

Gözpinar, H. (2019). Challenges and experiences Of EFI teachers and newly arrived refugee students: an ethnographic study in Turkey. MIER J. Educ. Stud. Pract. Educational Studies, Trends & Practices 9, 147–164.

Guyton, E. M., and Wesche, M. V. (2005). The multicultural efficacy scale: development, item selection, and reliability. Multicult. Perspect. 7, 21–29. doi: 10.1207/s15327892mcp0704_4

Hek, R. (2005). The role of education in the settlement of young refugees in the UK: the experiences of young refugees. Pract. Soc. Work Action 17, 151–171. doi: 10.1080/09503150500285115

Hos, R., and Kaplan-Wolff, B. (2020). On and off script: a teacher's adaptation of mandated curriculum for refugee newcomers in an era of standardization. J. Curric. Teach. 9, 40–54. doi: 10.5430/jct.v9n1p40

Kanu, Y. (2008). Educational needs and barriers for African refugee students in Manitoba. Canad. J. Educ. 31, 915–940.

Karabenick, S. A., and Clemens Noda, P. A. (2004). Professional development implications of teachers' beliefs and attitudes toward English language learners. Biling. Res. J. 28, 55–75. doi: 10.1080/15235882.2004.10162612

Kim, K. R., and Seo, E. H. (2018). The relationship between teacher efficacy and students' academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 46, 529–540. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6554

Kirova, A. (2001). Loneliness in immigrant children: implications for classroom practice. Childh. Educ. 77, 260–267. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2001.10521648

Klassen, R. M., and Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers' self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 12, 59–76. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Knoblauch, D., and Hoy, A. W. (2008). “Maybe I can teach those kids.” The influence of contextual factors on student teachers' efficacy beliefs. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 166–179. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2007.05.005

Kopish, M. A. (2016). Preparing globally competent teacher candidates through cross-cultural experiential learning. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 7, 75–108.

Leeman, Y., and van Koeven, E. (2019). New immigrants. An incentive for intercultural education? Educ. Inquiry 10, 189–207. doi: 10.1080/20004508.2018.1541675

Levi, T. K. (2019). Preparing pre-service teachers to support children with refugee experiences. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 65, 285–304. doi: 10.11575/ajer.v65i4.56554

Lucas, T. (1997). Into, Through, and Beyond Secondary School: Critical Transitions for Immigrant Youths. Topics in Immigrant Education 1. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

McBrien, J. L. (2005). Educational needs and barriers for refugee students in the United States: a review of the literature, Rev. Educ. Res. 75, 329–364. doi: 10.3102/00346543075003329

Milner, H. R. (2011). Culturally relevant pedagogy in a diverse urban classroom. Urban Rev. 43, 66–89. doi: 10.1007/s11256-009-0143-0

Peeler, E., and Jane, B. (2005). Efficacy and identification of professional self. Acad. Exchange Quart. 9, 224–228.

Peko, A., Sablic, M., and Jindra, R. (2010). “Intercultural education,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Scientific Conference - Obrazovanje za interkulturalizam: Zbornik radova S. 2 Medunarodne znanstvene konferencije. Online Submission. Croatia: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek.

Petersen, K. B. (2017). Preparation of student teachers for multicultural classrooms: reflections on the danish teacher education curriculum. J. Int. Soc. Teach. Educ. 21, 45–54.

Pinson, H., and Arnot, M. (2007). Sociology of education and the wasteland of refugee education research. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 28, 399–407. doi: 10.1080/01425690701253612

Portes, A., and Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rah, Y., Choi, S., and Nguyên, T. S. T. (2009). Building bridges between refugee parents and schools. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 12, 347–365. doi: 10.1080/13603120802609867

Romijn, B. R., Slot, P. L., Leseman, P. P., and Pagani, V. (2020). Teachers' self-efficacy and intercultural classroom practices in diverse classroom contexts: a cross-national comparison. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 79, 58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.08.001

Roxas, K. (2010). Who really wants “the poor, the tired, and the huddled masses” anyway? Teachers' use of cultural scripts with refugee students in public school classrooms. Multicult. Perspect. 12, 1–9.

Roxas, K. (2011). Tales from the front line: teachers' responses to Somali Bantu refugee students. Urban Educ. 46, 513–548. doi: 10.1177/0042085910377856

SIREE (2021). Social Integration of Refugees through Education and Self-Employment. SIRE. Available online at: https://www.siree.eu/post/read-about-the-siree-project-through-our-ebook (accessed December 09, 2021).

Siwatu, K. O. (2007). Preservice teachers' culturally responsive teaching self-efficacy and outcome expectancy beliefs. Teach. Educ. 23, 1086–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.07.011

Sklad, M., Goedhart, R., Van der Looij, L., Camps, M., Vanobberghen, E., and Dewitte, S. (2021). Teacher Training Modules Education For Newcomers – Demonstration Guide. SIREE.EU. Available online at: https://www.siree.eu/post/learn-about-our-teacher-training-courses (accessed December 09, 2021).

Sleeter, C. E. (2001). Preparing teachers for culturally diverse schools: research and the overwhelming presence of Whiteness. J. Teach. Educ. 52, 94–106. doi: 10.1177/0022487101052002002

Southern, N. L. (2007). Mentoring for transformative learning: the importance of relationship in creating learning communities of care. J. Transform. Educ. 5, 329–338. doi: 10.1177/1541344607310576

Stark, L., Robinson, M. V., Gillespie, A., Aldrich, J., Hassan, W., Wessells, M., et al. (2021). Supporting mental health and psychosocial wellbeing through social and emotional learning: a participatory study of conflict-affected youth resettled to the US. BMC Public Health 21, 1620. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11674-z

Stevenson, J., and Willott, J. (2007). The aspiration and access to higher education of teenage refugees in the UK. Compare 37, 671–687. doi: 10.1080/03057920701582624

Strekalova, E., and Hoot, J. (2008). What is special about special needs of refugee children? Multicult. Educ. 16, 21–24.

Svensson, M. (2019). Compensating for conflicting policy goals: Dilemmas of teachers' work with asylum-seeking children in Sweden. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 63, 1–16.

Szente, J., Hoot, J., and Taylor, D. (2006). Responding to the special needs of refugee children: practical ideas for teachers. Early Childh. Educ. J. 34, 15–20. doi: 10.1007/s10643-006-0082-2

Trueba, H. T., Jacobs, L., and Kirton, E. (1990). Cultural Conflict and Adaptation: The Case of Hmong Children in American Society. New York, NY: Falmer Press.

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2007). The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 23, 944–956. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.003

Ukasoanya, G. (2014). Social adaptation of new immigrant students: cultural scripts, roles, and symbolic interactionism. Int. J. Adv. Counsell. 36, 150–161. doi: 10.1007/s.10447-013-9195-7

UN News. (2022). Global Perspective Human Stories. Retrieved from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/06/1120642 (accessed May 12, 2023).

UNICEF (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/childrights-Convention (accessed May 05, 2023).

Vrdoljak, A., Stanković, N., Corkalo Biruški, D., Jelić, M., Fasel, R., and Butera, F. (2022). “We would love to, but…” - needs in school integration from the perspective of refugee children, their parents, peers, and school staff. Int. J. Qualit. Stud. Educ. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2022.2061732

Walker-Dalhouse, D., Sanders, V., and Dalhouse, A. D. (2009). A university and middle-school partnership: preservice teachers' attitudes toward ELL students. Literacy Res. Instruct. 48, 337–349. doi: 10.1080/19388070802422423

Walsh, C. S., and Townsin, L. (2015). A New Border Pedagogy to Foster Intercultural Competence to Meet the Global Challenges of the Future. Western: Australian Association for Research in Education.

Keywords: refugees and asylum seekers, self-efficacy (SE), measurement scale development, competence, wellbeing, pupils, immigrant children

Citation: Sklad M (2023) Supporting and measuring current and future educators' preparedness to facilitate wellbeing of displaced children in schools. Front. Educ. 8:1165746. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1165746

Received: 14 February 2023; Accepted: 27 April 2023;

Published: 02 June 2023.

Edited by:

Nicole Jacqueline Albrecht, Flinders University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Alberto Crescentini, University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2023 Sklad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcin Sklad, bS5za2xhZEB1Y3Iubmw=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.