94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 12 April 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1156530

This article is part of the Research Topic Research on Teaching Strategies and Skills in Different Educational Stages View all 32 articles

Introduction: Effective communication skills are essential for successful behavior management in the classroom. Teachers who can respond proactively and in a student-centered manner can create a positive and productive learning environment. However, the empirical support for student-centered communication practices in behavior management is limited.

Methods: To address this gap, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify the characteristics of student-centered behavior management strategies that lead to lower behavior problems and increased student engagement. The review utilized a PRISMA protocol to ensure the rigor of the study selection process.

Results: Five main categories were identified that characterize student-centered behavior management responses. A table of 24 communication strategies was presented based on the findings of the review. The study also discussed the further impact of these strategies on student motivation, learning outcomes, responsibility, and interpersonal classroom climate.

Discussion: The findings of this study highlight the importance of effective communication skills in behavior management and provide valuable insights for teachers to improve their practice. By implementing these student-centered communication strategies, teachers can manage the classroom effectively, creating a more positive and productive learning environment and supporting students in achieving better learning outcomes.

Teachers worldwide spend a significant amount of their teaching time managing student behavior and report it as their main challenge in the profession (Eisenman et al., 2015; Kwok, 2020). In the United States, more than one-third of teachers stated that student behavior interfered with their teaching [as reported in Steinberg and Lacoe (2017)]. Similarly, in the recent Talis (OECD, 2019) study, it was reported that 29 percent of teachers spend a significant amount of their instruction time on behavior management. In a survey in Australia (Auditor General Western Australia, 2014), 39 percent of teachers used more than 20 percent of their teaching day on student behavior.

There is not one single widely accepted definition of classroom behavior management. Brophy (2006) describes classroom management as any teachers’ actions, which create and facilitate a learning environment for successful instruction. Emmer and Evertson (2012) conclude that for effective behavior management, which is an essential part of classroom management, teachers need to develop a caring relationship with and among students, encourage students’ engagement, optimize student access to learning, promote students’ social, emotional, and self-regulation skills, and use appropriate interventions to help students with behavior problems. The current study focuses on a key component of classroom behavior management, specifically on teachers’ communication responses to student behavior.

Effective teaching and learning cannot happen in poorly managed classrooms (Hattie, 2009, 2012; Korpershoek et al., 2016). If not managed effectively, classroom disturbances increase teachers’ stress, drop-out, and job dissatisfaction (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; Aldrup et al., 2018; Paramita et al., 2020). Further, ineffective classroom management strategies harm student wellbeing, responsibility, self-concept, and result in a greater amount of disruptive behavior in the classroom (Larrivee, 2005; Omoteso and Semudara, 2011). On the other hand, as Emmer and Evertson (2012) suggest, when teachers possess effective behavior management skills, it reduces their stress and burnout (Oliver et al., 2011). It also enables them to deal with problem behavior more efficiently, establish a safe learning climate, and positive teacher-student relationships (Gordon and Burch, 2003; Larrivee, 2005; Ming-Tak and Wai-Shing, 2008; Porter, 2014; Schonert-Reichl, 2017), which in return increase students’ motivation (Kunter et al., 2007), learning achievements (Oliver et al., 2011; Omoteso and Semudara, 2011), prosocial behavior, and both teachers’ and students’ wellbeing (Oliver et al., 2011; Schonert-Reichl, 2017).

The role of teachers’ communication in classroom behavior management has been repeatedly emphasized (Porter, 2014; Burden, 2016). Communication skills to respond to student behavior are considered an integral and crucial part of classroom management skills (Gordon and Burch, 2003; Ming-Tak and Wai-Shing, 2008; Roache and Lewis, 2011). Fogelgarn et al. (2020) emphasize that the way teachers talk to students directly impacts student behavior, teacher-student relationships, student autonomy, and classroom climate. The current study addresses the crucial communication skills teachers need for effective behavior management. Specifically, it focuses on behavior management communication strategies or practices, which are teachers’ specific responses to student behavior. These responses include both verbal also non-verbal behaviors such as gestures, voice tone, eye contact, or body posture for they are inevitably tied to teachers’ communication practices in the classroom (LaBelle et al., 2013).

As suggested by Porter (2014), teachers’ use of communication practices or strategies depend on their approach to classroom management. These approaches vary from the traditional, teacher-directed behavioral models to the more recent humanistic student-centered models (Alcruz and Blair, 2022). Hart (2010) suggests that the former includes the use of communication strategies such as praise or punishment to reinforce or reduce student behavior. The latter include communication strategies such as listening to views of students, or non-directive non-judgmental language (Larrivee, 2005) to provide students with space to regulate their own behavior.

A recent meta-review shows a growing trend away from teacher-directed approaches promoting compliance and obedience to a more holistic and student-centered approach to classroom management, promoting students’ self-regulation and autonomy (Freiberg et al., 2020). The student-centered approach is rooted in humanistic psychology (Rogers, 1969; Gordon and Burch, 2003) and emphasizes the importance of both teachers’ and students’ needs; it promotes mutual trust, respect, connectedness, shared responsibility, student self-regulation, positive relationships, and safe and positive school climate (Freiberg and Lamb, 2009).

Student-centered communication practices are associated with a positive impact on student behavior, relationships, and learning. Cornelius-White (2007) posited that empathy and non-directivity helps teachers eliminate power struggles, which supports students in their learning and behavior. His meta-analysis reported an association of student-centered education with significant increases in participation, satisfaction, and learning motivation. It also reports effects on self-esteem and social skills, reduction in drop-out, disruptive behavior, and absences (Cornelius-White, 2007). Establishing student-centered classrooms also promotes positive teacher-student relationships, a safe classroom climate, student academic achievements, and social and emotional development (Weinstein and Romano, 2018; Gokalp and Can, 2021). Moreover, it also allows teachers to focus more on student academic and social-emotional outcomes and spend less time managing student behavior (Talvio et al., 2014).

Teachers’ classroom management communication practices include a wide range of proactive and reactive strategies, both having a different impact on student behavior (Hepburn and Beamish, 2019; Paramita et al., 2021). Proactive strategies emphasize the prevention of classroom disturbances through building relationships, actively engaging students, creating classroom rules, or establishing a safe learning environment. These strategies have wide support in research studies suggesting that proactive teachers have classrooms with fewer disturbances, engaged and motivated students, and higher student achievements (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; Hepburn and Beamish, 2019). Reactive strategies are those that teachers use directly in response to student behavior. Most studies focusing on reactive strategies include among these disciplinary interventions such as punishments, giving warnings, threatening, administering consequences, making sarcastic comments, yelling angrily at students, reprimands, or directives (Lewis et al., 2005; Paramita et al., 2021). Clunies-Ross et al. (2008) suggest that reactive strategies include mostly negative teachers’ responses and increase problem behavior. Miller et al. (2000) support these findings suggesting that students express problem behavior in response to teachers’ unfair, harmful, or aggressive behavior. Also, these classroom management strategies are not effective in the long term and have a negative impact on teacher-student relationships, student autonomy, achievements, and teachers’ wellbeing (Lewis et al., 2005; Hepburn and Beamish, 2019; Paramita et al., 2021).

Authors repeatedly emphasize that for effective classroom management, teachers need to implement proactive classroom management strategies (Hepburn and Beamish, 2019; Paramita et al., 2021), however, there are situations when teachers need communication strategies to respond to student behavior directly when it occurs. Although reactive strategies are frequently referred to as teachers’ negative responses to student behavior, numerous authors suggest that there are communication responses teachers can use directly in response to student behavior, which promote teacher-student relationship, support student autonomy, social and emotional skills, engagement, self-concept, and decreases student misbehavior (Gordon and Burch, 2003; Larrivee, 2005; Porter, 2014; Talvio et al., 2014). Madden and Senior (2017) label these strategies as responsive rather than reactive and emphasize that these strategies do not always have a negative impact on students; they can be used in accordance with the student-centered approach and can be effective in helping students with their behavior issues and providing the students with space to self-regulate. Gordon and Burch (2003), for instance, include among these I-messages or Active listening. As opposed to the traditional view of reactive strategies, these strategies are reported as effective in the long term (Porter, 2014). Talvio et al. (2014) build on Gordon and Burch’s ideas and suggests that these strategies such as I-messages or active listening support student social and emotional development for teachers’ effective communication skills are integrated into the social and emotional competence model (Talvio et al., 2014).

Effective behavior management practices are widely researched and reviewed. Research reviews and meta-analyses focus mostly on general classroom management practices (Korpershoek et al., 2016; Hepburn and Beamish, 2019), or programs (Oliver et al., 2011; Korpershoek et al., 2016; Freiberg et al., 2020). Further, research reviews focus on specific classroom management strategies in accordance with the behavioral approach, such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS) practices (Hepburn and Beamish, 2019; Estrapala et al., 2020). However, little attention is given to the student-centered or humanistic approach to behavior management and to student-centered communication strategies that are used directly in response to student behavior. Although these responsive student-centered strategies have broad theoretical support (Larrivee, 2005; Hattie, 2009, 2012; Porter, 2014; Burden, 2016), the empirical support is somewhat limited. According to our search in Web of Science, Scopus, and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) databases, there were not found any literature reviews or meta-analyses that would address the humanistic communication strategies teachers employ to manage student behavior. Our search covered the period from 1995 to 2021, and used several key words, including “student-centered,” “literature review,” “systematic review,” “meta-analysis,” “behavior management,” and “communication strategies.” For such an approach yields positive results (Porter, 2014), a literature review gathering these strategies warrants to be interesting for educators and researchers who want to employ these strategies in teacher preparation programs or address these teaching strategies in research studies. The review presented here offers a position from the student-centered approach, aiming to identify a broader range of effective student-centered communication strategies teachers can use in response to student behavior to reduce the problem behavior or increase student engagement in the classroom. Additionally, this review found the impact that these student-centered behavior management communication strategies have on students besides the reported impact on their behavior and engagement. It further describes the student-centered communication strategies, which lead to a decrease in student problem behavior or an increase in student behavior engagement. It also presents the further impact of these communication practices on students and characterizes the reviewed studies.

1. What characterizes student-centered behavior management communication strategies that lead to lower behavior problems or increased behavior engagement?

2. What further impacts do the student-centered behavior management communication strategies have on students?

This study is a literature review using a narrative approach (Snilstveit et al., 2012), based on the principles of the systematic review (Booth et al., 2016) to add new insights and recommendations while providing transparency and clarity and formal guidance on the method. Using this approach, this study provides a descriptive overview of the studies on teachers’ student-centered communication practices used to effectively deal with student behavior.

A literature search following the PRISMA protocol (Booth et al., 2016) was conducted, using three individual searching methods based on Randolph (2009) literature review methodology: search in databases, reference search, and contacting experts. Before the search, a set of inclusion criteria was designed and piloted by two sample searching processes; subsequently, the criteria were slightly changed to yield reliable results.

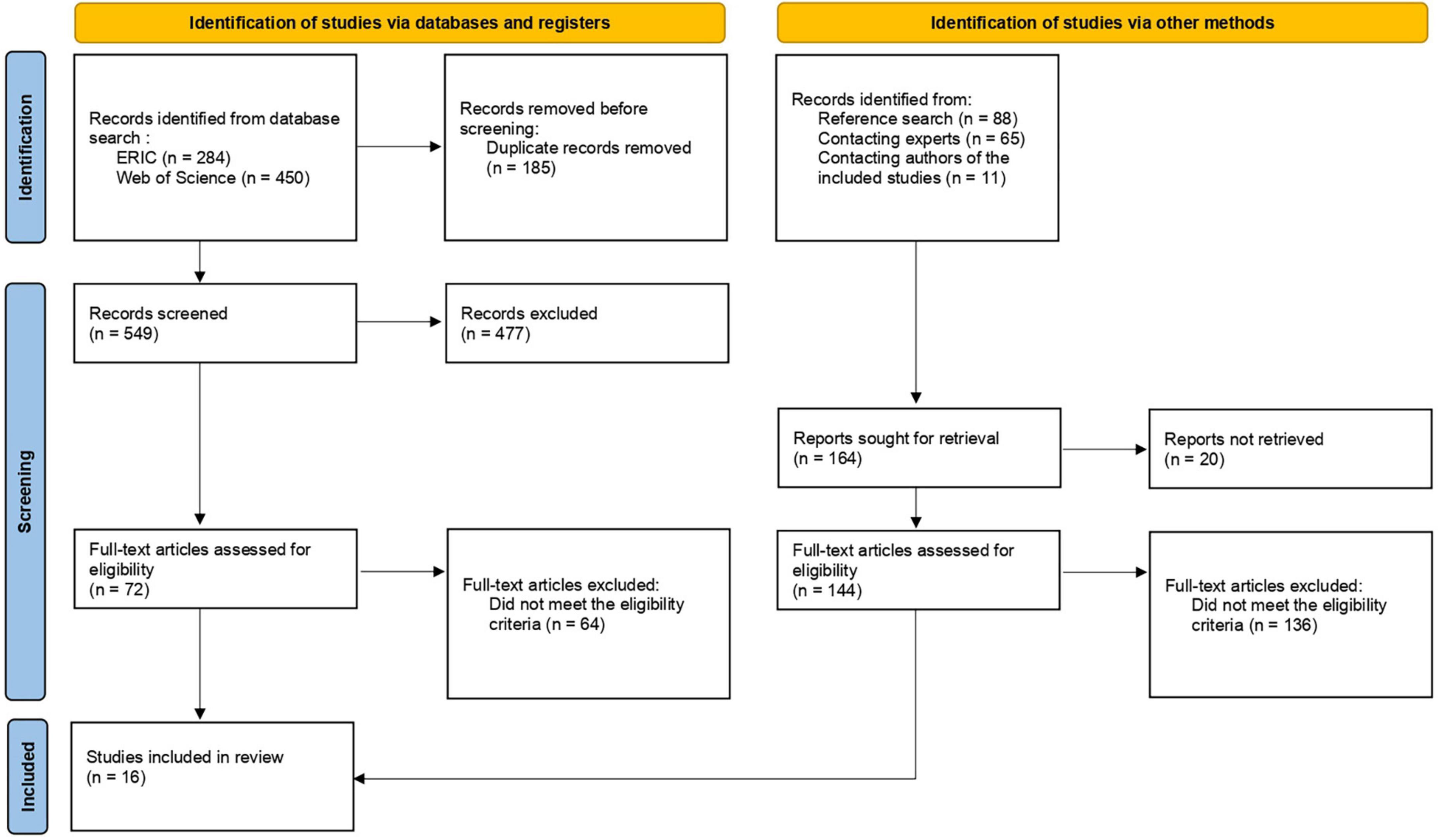

The whole process of data collection and evaluation can be seen in Figure 1. The first stage of data collection was an electronic search of academic databases; Web of Science and ERIC databases were used. ERIC and Web of Science (WOS) databases were chosen for our literature review search due to their comprehensive coverage of academic literature in the field of education, as well as their sophisticated search tools which allowed us to refine our search terms and tailor our search to our specific topic. In addition, WOS is known for its high-quality indexing of articles and its citation tracking, which ensures the access to the most relevant and up-to-date literature on our educational topic. For the initial search, the keywords “classroom management,” “behavior management,” and “strategies” were used and combined using the Boolean operator “OR.” This means that the search results would include articles that contain any one of these keywords. Subsequently, the search was refined five times by adding keywords: “humanism,” “effective,” “autonomy,” “misbehavior,” and “techniques.” These keywords were also combined using the “OR” operator, which means that the search results would include articles that contain any one of these additional keywords in addition to the initial keywords. As noted by Vongalis-Macrow (2009), in the 90’s, globalization emerged as a great impetus for educational reforms. Therefore, a systematic review search was limited to peer-reviewed journals published between 1995 and 2021. This time frame was chosen as it captured a period of significant change and innovation in the field of education, including a growing interest in evidence-based practices (Hargreaves, 2007). Additionally, this approach allowed for the retrieval of studies that continue to be influential in current education research. The Web of Science search was limited to four subject areas: Education, Psychology, Communication, and Behavioral Sciences.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram (updated from Page et al., 2021).

The initial search identified 734 articles. Of these, 185 duplicates were removed, and 477 were excluded after reading the abstract based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: Inclusion criteria: (1) the study reported the impact of communication strategies on student engagement, or behavior, (2) the communication strategy was in accordance with the principles of student-centered humanistic approach; (3) the study was conducted in an educational context, including early childhood, elementary, secondary, and higher education contexts, (4) the study was a research article or a review. Exclusion criteria: (1) books, or other sources that were not a research article or a review, (2) studies carried out in a non-education context, (3) the communication strategies used were in accordance with or grounded in the behaviorist or teacher-directed approach, (4) the study did not report the impact of communication strategies on student behavior or engagement. Seventy-two articles remained for further examination. The process of inclusion of studies was conducted with another researcher to ensure the quality of the search and inclusion process. A full-text review resulted in five studies meeting the criteria.

Second, as Randolph (2009) recommends, the references of the most relevant full-text reviewed articles were retrieved. Those references, which seemed relevant were found, and their references were read. This process was repeated until no new articles came to light. This search resulted in 88 articles examined; three of them were included based on the inclusion criteria.

After database and reference searching, 28 most-cited experts in the field of classroom management, classroom interaction, behavior management, or autonomy support were contacted via email. They were shared with a brief explanation of the problem formulation, literature search objectives, and preliminary findings. The experts were asked about any further references that might be included in the literature review and other further ideas or recommendations regarding the researched topic. A total of 65 articles were gathered from the nineteen responses that were obtained. All of them were full text examined. After excluding already included articles and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, five studies were included in the review.

Further, the authors of the studies intended for inclusion in the review were contacted. The findings were shared with them, and a brief description of the study was provided, followed by a request for a critical view on the study’s inclusion. They were asked about any further recommendations for studies to be included in the review. In this email, I also asked for additional pieces of information, which were missing in the studies. For the main aim of the study was to provide a picture of student-centered communication practices and provide their individual descriptions, each of the authors was asked to provide a brief quote of the communication strategy listed in the included research articles. Fifteen responses were gathered throughout this process, which helped us to revise the studies and create a table with each communication strategy supported by a quote and a description. This process resulted in ten further studies, of which one was included in the review.

The quality of the studies included in this review was assessed using an adapted version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018). This tool was chosen as it is specifically designed for reviews that include a combination of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies. Two researchers independently evaluated the quality of the selected studies using the MMAT. The tool includes two screening questions for all research designs and five specific criteria for each research design category, such as qualitative research, quantitative randomized controlled trials, quantitative non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed-method studies. Each criterion is rated as “Yes,” “No,” or “Can’t tell.” In this review, the reviewers agreed to use only “Yes” or “No” ratings. To report the quality of the studies was used a combination of stars (*). Each star stands for 20% (e.g., three stars stand for 60%, four stars stand for 80%. five stars stand for 100%). Each criterion was assigned a value of one star or 20%. For example, a study that fulfilled three criteria would receive three stars, which equals 60%. Ratings for each study and criterion and the overall score can be found in Figure 2.

For the data analysis and interpretation, the review used a content analysis approach (Silverman, 2020). It enabled us to include and analyze both qualitative and quantitative studies and code the studies by drawing on a theoretical framework underlying this study. The codes were created both deductively and inductively. The studies were coded to capture the general and detailed description of the communication practices used in the studies. The codes were further inductively classified and categorized.

To analyze and report the description of student-centered communication practices affecting student behavior were created categories to reflect their key patterns, similarities, and differences. These categories were based on a qualitative content analysis of the description of each communication strategy; the descriptions were provided in the research studies or obtained directly from the studies’ authors. Creating the individual descriptions of the strategies and their categorization was done by two individual researchers through constant interaction between the research studies’ content, the theoretical framework supporting the studies, and communication with the authors. The process of the analysis can be seen in Supplementary Table 1.

Altogether, 16 studies were included in the in-depth review. Table 1 provides key information for each research paper. Studies were conducted in USA (9), Belgium (2), Israel (2), South Korea (1), Australia (2), China (1), and Ireland (1). One study was conducted in three countries. The studies were conducted in the context of elementary schools (4), secondary schools (7), colleges (3), and universities (3). One study was conducted in two educational contexts. The prevailing study design in the reviewed studies was quantitative (13), three studies used a qualitative methodology design, and one combined qualitative and quantitative instruments to assess the impact of student-centered communication strategies. All studies reported the relation of student-centered communication strategies to student behavior (16). The classrooms where teachers used student-centered communication practices in response to student behavior reported a decreased level of misbehavior (12), increased prosocial behavior (1), or increased behavioral engagement (3). Further effects of the student-centered communication practices include increased students’ participation in class (1), learning outcomes (2), motivation (2), study behavior (1), need satisfaction (1), responsibility (2), self-regulation (1), and interpersonal climate (3).

The student-centered communication strategies are further characterized into five groups (sub-sections “4.2.1. Perspectives and feelings, 4.2.2. Choice and autonomy-support, 4.2.3. Non-directive non-judgmental language, 4.2.4. Explanations and expectations, and 4.2.5. Teacher immediacy and form of the message”), as identified throughout the content analysis. The specific communication strategies gathered throughout the review can be found in Figure 3. The extended version of the Supplementary Table 2 also contains references and definitions for each communication strategy. Supplementary Table 1 describes which communication strategy belongs to each group.

Taking students’ perspectives, recognizing their feelings, and acknowledging them were among the most frequent features of communication strategies listed throughout the reviewed studies. Teachers take and acknowledge students’ perspectives when they experience the classroom events as if they were the students. Teachers also communicate to students that they value and follow their perspectives even when they disagree. Further, any students’ expression of negative affect is accepted as a valid reaction to classroom demands, rules, or activities (Jang et al., 2010). Authors emphasize the importance of communicating to students that teachers value and follow their perspectives and feelings even when they disagree (Wallace et al., 2014; Weger, 2017).

In this review, Taking students’ perspectives and Acknowledging students’ feelings are reported in one category as they frequently overlap and are used as one communication strategy (Jang et al., 2010; Vansteenkiste et al., 2012; Cheon et al., 2019). For instance, Wallace et al. (2014) term these strategies together as Open communication. Other authors emphasize the importance of recognizing and acknowledging students’ perspectives and feelings when using other communication strategies. Aelterman et al. (2018) conclude that it is key to ask about students’ feelings and acknowledge them when discussing rules with students. Goodboy and Myers (2008) and Buckner and Frisby (2015) also include in their study communication strategies that communicate to students that they are recognized and acknowledged as valuable individuals with their needs and affects; they use the term Confirmation. Similarly, teachers can recognize and acknowledge students’ perspectives and feelings when providing clear expectations for behavior, asking questions, or actively listening (Vansteenkiste et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2014; Weger, 2017).

Besides acknowledging students’ feelings and perspectives, the authors also point to the importance of supporting students to see the perspectives of others. Roache and Lewis (2011), Miller et al. (2014), and Wallace et al. (2014) emphasize the importance of talking about teachers’ perspectives. Teachers use I-messages, Open communication, or Self-disclosure to describe their feelings, explain why specific behavior is unacceptable, illustrate a rule, or provide a particular rationale for expected behavior (Peterson et al., 1979; Roache and Lewis, 2011; Miller et al., 2014; Wallace et al., 2014).

When talking about providing students with choice and autonomy, authors repeatedly emphasize the importance of teachers’ autonomy-supportive language or behavior (Assor et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2010; Vansteenkiste et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2014; Cheon et al., 2019). They stress that it is crucial to communicate with the students in an autonomy-supportive way as frustrating the need for student autonomy may lead to negative behavioral, motivational, and affective outcomes. Vansteenkiste et al. (2012) conclude that autonomy is not about unlimited freedom where students lack sufficient guidance. Instead, teachers adopt the autonomy-supportive language and provide students with structure (such as communicating requests and clear expectations) in an autonomy-supportive way (e.g., through adopting their perspectives, providing them with choice, and accepting their negative affect).

The studies include among autonomy-supportive language communication strategies termed Open communication, Providing choice, Acknowledging and accepting students’ negative feelings, Taking students’ perspectives, Invitational language, Discussing the rules with students, Hinting, and Clear expectations (Figure 2). More specifically, in four studies, authors emphasize the importance of providing students with the desired amount of choice (Assor et al., 2002; Vansteenkiste et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2014; Cheon et al., 2019). Vansteenkiste et al. (2012) and Cheon et al. (2019) use the term Inviting language to talk about language, which promotes choice and volition (you might, you can) instead of control (you should, you must, you need to). Further, the authors emphasize the importance of giving students freedom of mobility, opportunities to collaborate, allowing them to work in their own way, or giving them the responsibility to use their own solutions to solve any issue without teacher control. Romi et al. (2009) use the term Hinting to talk about communication strategy which informs students that they are breaking some rule, without telling them explicitly what to do; thus, providing them with autonomy to solve the situation themselves. In contrast, Assor et al. (2002) conclude that the role of choice and freedom of action is less important than the extent to which students perceive the requests, rules, or task as personally meaningful. Therefore, it might be crucial to combine the desired amount of choice with supporting students to find their own perspectives, values, and relevance of the expected behavior, for instance when discussing the rules with students (Aelterman et al., 2018).

The non-directive and non-judgmental language was frequently mentioned and contrasted with evaluative, controlling, pressuring, and coercive teacher talk. Jang et al. (2010) state that by using non-controlling informational language, teachers provide the students with a sense of ownership, choice, and responsibility for solving the problem and regulating their behavior. Likewise, Vansteenkiste et al. (2012) and Cheon et al. (2019) use the term Invitational language to speak about teachers’ communication responses that minimize pressure on students by incorporating options and choices instead of commands and directives.

The review showed that most of the studies emphasized non-directive and non-judgmental language as part of the communication strategies listed (e.g., Active Listening, I-messages, Hinting, Non-controlling language, and Autonomy-supportive language). Specifically, Romi et al. (2009) and Roache and Lewis (2011) use in their research a communication strategy called Hinting: a non-judgmental non-directional description of student behavior. They argue that unlike controlling teachers’ statements, such as commands, hints offer students space for their responsibility to deal with their problems. Roache and Lewis (2011) distinguish various types of hints, such as specific hints (addressing a specific behavior), general hints (describing a problem situation in a general way), a restatement of expectations (re-emphasizing rules), I-messages, and direct questions. Wallace et al. (2014) also include Questioning as a communication strategy in their study and argue that it offers students space to respond or change their behavior before offering any comments, directives, or suggestions. Further, Weger (2017) points to Active listening as a key communication strategy and emphasizes that its most important part is that it is non-judgmental. Similarly, Peterson et al. (1979) point to the importance of non-judgmental informational language. They contrast I-messages with You-messages, claiming that I-messages contain no judgment and no directive for the students. Using I-messages, teachers describe students’ disruptive behavior, state their feelings in response to the student’s behavior, and indicate why students’ behavior negatively affects the teacher (Peterson et al., 1979; Gordon and Burch, 2003).

Providing students with explanations and expectations was another broad category of communication practices. When dealing with student behavior, teachers can communicate to students expectations, rules, and explanations for requested behavior; this way, teachers introduce their requests and rules by explaining their value and importance so that the students will see them as personally meaningful (Wallace et al., 2014; Cheon et al., 2019; Chesebro and Lyon, 2020). Romi et al. (2009) and Roache and Lewis (2011) conclude that when teachers set expectations and work out the rules for appropriate behavior with the students, they feel more responsible for their behavior. Aelterman et al. (2018) and Cheon et al. (2019) support this idea and argue Providing rationale is one of the communication strategies that help students feel not being pressured or controlled; instead, students can perceive behavioral requests as more personally meaningful and are likely to internalize the value. Further, Miller et al. (2014) connect explanatory rationale with teachers’ life stories or experiences. They state that teachers can add relevant, friendly, and personal disclosure (e.g., their personal or professional experiences) to the explanation of rules or expected behavior to show their relevance.

Authors point to the importance of explaining and explicitly describing the impact of student behavior on others. Peterson et al. (1979) and Romi et al. (2009) describe I-messages and Hinting as communication strategies which explain why student behavior interferes with teachers’ or students’ needs and allow students to respond to the problem situation with no pressure or directive from the teacher. Wallace et al. (2014) and Chesebro and Lyon (2020) further note that when teachers explain why certain behavior interferes with their needs or with the learning process and what impact it can have, students may choose to behave differently for they find it personally meaningful.

Besides explanations, Vansteenkiste et al. (2012) state that teachers need to provide clear expectations for desirable classroom behavior. When giving expectations, teachers state the rule, instruction, or target behavior and transfer responsibility for the action to students, leaving them accountable for their learning and behavior. However, they add that teachers may communicate the expectations in an autonomy-supportive way and in a non-judgmental manner, for instance, by providing explanatory rationale or using non-controlling language. Wallace et al. (2014) support this idea by suggesting that it is essential to give clear expectations and steps to follow when requesting a rule or action, however, it should always be accompanied by an explanatory rationale.

All the communication strategies listed differed in the form of the messages sent and in the closeness or immediacy of teacher behavior. The ways of communicating immediacy include appropriate use of eye contact, gestures, voice tone, smile, movement, physical contact, or physical closeness. It is any behavior that indicates physical or psychological closeness (Weger, 2017). Wallace et al. (2014), Cheon et al. (2019), and Chesebro and Lyon (2020) highlight the importance of teachers’ voice tone when using Invitational language, asking questions, or using a Composed and respectful response. Invitational language is sent in a higher pitch to communicate understanding and support; Questions use a tone that conveys respect and implicit rationale of the message; Chesebro and Lyon (2020) stress the importance of sending the message in a tone that is composed, respectful and calm.

Eight main types of the teachers’ messages were distinguished regarding the form of teacher talk: Asking questions (Romi et al., 2009; Wallace et al., 2014; Chesebro and Lyon, 2020), Offering advice (Wallace et al., 2014), Listening (Worley et al., 2007; Wallace et al., 2014; Weger, 2017; Cheon et al., 2019), Providing request (Vansteenkiste et al., 2012; Cheon et al., 2019; Chesebro and Lyon, 2020), Giving a statement (Peterson et al., 1979; Romi et al., 2009; Roache and Lewis, 2011), and Discussing or facilitating privately or out of class (Wallace et al., 2014; Aelterman et al., 2018; Chesebro and Lyon, 2020).

The two broadest categories were Questions and Listening. The authors identified various aims of asking the questions. Teachers ask questions to get clarification from the students about any issue, behavior, or affect they experience (Wallace et al., 2014; Weger, 2017). Questions can also point to problem behavior in the classroom, asking the students about the rules in the classroom or the expected behavior (Roache and Lewis, 2011). Wallace et al. (2014) suggest that teachers can help students think through problems by asking them questions, which help them to see things from different perspectives and find individual ways to solve an issue. The form of the question is always descriptive (What happened?) or corrective (What can we do with that?).

Listening to students was another broad category, which involves attentively listening to students’ feelings and ideas. During active listening, teachers take students’ perspectives and try to understand students’ points of view. Teachers paraphrase what the students are saying to clarify understanding and send students a message that they understand and accept their feelings. The authors list active listening as a communication strategy to use during conflict resolutions or when involving students in decision-making (Worley et al., 2007; Weger, 2017). Romi et al. (2009) and Roache and Lewis (2011) include active listening as an essential component when teachers discuss the impact of student behavior on others.

The present research review aimed at providing a deep characterization of student-centered communication strategies, which lead to lower behavior problems in the classroom. Sixteen studies were identified that demonstrated the positive impact of student-centered communication strategies on student behavior. Five main characteristics that these communication strategies have in common were found. The prevailing characteristics of the student-centered communication practices were that they are non-judgmental and non-controlling, they recognize and accept students’ perspectives, provide choice, if possible, give clear expectations for behavior, explain the reason for any request or rule, and are sent in a calm manner. These characteristics can be seen as principles that can help formulate student-centered responses to student behavior. Further, with the help of the authors of the reviewed studies, a table with specific twenty-four communication strategies with their brief descriptions and sample statements was created.

Notably, the studies’ analysis results further revealed that using student-centered communication strategies in the classroom leads to fewer behavior problems or greater behavioral engagement; they further promote student motivation, learning achievements, responsibility, self-regulation, and interpersonal climate. These results align with those obtained by Cornelius-White (2007), who emphasizes the positive impact of a student-centered approach in the classroom. This reinforces the theory of Fogelgarn et al. (2020), suggesting that communication of the teacher is a crucial classroom management skill that directly impacts student behavior, autonomy, and classroom climate.

Most studies focused on verbal communication strategies; however, four studies also focused on non-verbal communication practices, such as voice tone, eye contact, smile, and calmness. Non-verbal aspects of communication are less discussed, even in theoretical works on classroom management. LaBelle et al. (2013) emphasize that teachers’ responses inevitably include non-verbal behaviors which influence the statement that the teacher sends. Similarly, Larrivee (2005) concludes that there needs to be a congruence between teacher’s non-verbal and verbal messages. This supported the study of Jang et al. (2010) and Weger (2017); if teachers send a message describing student behavior in a calm manner, with a smile, warm voice, and patience, students are more likely to adjust their behavior and respond to the teacher’s request.

One interesting aspect that emerged from the analysis is that most of the student-centered communication strategies gathered can be used directly in response to student behavior. These results support the theory of Madden and Senior (2017) that responsive strategies do not always negatively impact student behavior and can be used in accordance with a student-centered approach to help students with their behavioral issues. For instance, teachers can use I-messages or Hinting to describe student behavior in a non-judgmental, non-directive manner. Similarly, providing an explanation of a teacher’s request or a rule can be used directly in response to student behavior while making it meaningful to the student and thus more likely that the students will internalize the value and adapt their behavior.

Further, the descriptions of the communication practices showed that student-centered communication strategies derive only slightly from teacher-directed methods. For instance, student-centered questions (Wallace et al., 2014) are sent in a tone that conveys respect, aiming to get additional information, understand student affect and behavior, or support students in their independent thinking (What happened? What can we do with that?) In comparison, Gordon and Burch (2003) and Larrivee (2005) emphasize the negative impact of questions, which are judging, threatening, or not accepting the students (Why did you…? Why are you…?). Similarly, the statement “You must take notes” is directive. Porter (2014) suggests that these statements lead to feelings of resentment and frustrate students’ need for autonomy. On the other hand, using invitational language (“You might take notes”) changes the statement into a non-directive, student-centered response. The studies which used this communication strategy reported increased prosocial behavior, interpersonal climate, and need satisfaction (Cheon et al., 2019). Thus, applying the five principles of student-centered communication strategies when responding to student behavior could potentially make the responses more relevant to students and might lead to a safe learning climate, increased student motivation, need satisfaction, learning achievements, responsibility, and self-regulation, and lower behavior problems in the classroom.

The findings from this study have several implications for teaching and learning. Teachers worldwide spend a significant amount on managing student behavior, claiming they have insufficient skills to solve these situations (Kwok, 2020). The findings of this study may support teachers and student teachers to gain competencies to manage student behavior effectively. The results show the importance of teachers’ student-centered responses to student behavior, define student-centered communication in its complexity and show specific communication strategies with their definition and sample responses. Teacher training should focus on these responses, illustrating to students the multiple ways to respond to student behavior effectively and the impact these communication practices may have on students. These materials can serve as a professional tool for teachers, who can learn about the communication strategies supported by research and use them in their practice. Further, the findings may inform teacher educators who can use them in their classroom management courses. The study provides qualitative examples and characteristics of both verbal and non-verbal responses for teachers and student teachers to use when dealing with problem situations in the classroom to solve them successfully with a positive impact on students and their behavior.

Whereas Freiberg et al. (2020) found a growing trend away from the teacher-directed approach, the current database search showed a rather small number of studies focusing on the student-centered behavior management approach or on student-centered communication strategies specifically. This may be partly due to the focus of the study and the choice of criteria: the search focused on studies that concentrated specifically on teachers’ communication strategies rather than on their classroom management strategies in general and included only studies conducted in the educational context. Future research could explore the topic of student-centered or humanistic communication in a broader context. On the other hand, the low number of studies included in the exploration may also indicate the strong need for further research on student-centered behavior management communication strategies in the classroom.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined precisely and in advance to decide which study to include in the current review. All attempts were made to perform a quality selection of the studies; three individual searching methods were used and the results were constantly consulted with the experts in the field; however, it is acknowledged that even with two independent reviewers, the selection of the studies is at risk for subjectivity.

It should also be noted that the studies were conducted in different countries and cultures. The linkage of the findings of each study to a certain cultural context (and the highly culturally bound issue of classroom management strategies) is acknowledged. When interpreting the results, this must be taken into consideration.

Also, the main aim of the study was to concentrate on the characteristics of student-centered communication strategies gathered throughout the review. Further analysis is needed for a more detailed picture of the included studies and their research designs and methods. Besides, it was only briefly commented on the impacts of communication strategies on students. Additional research might explore these impacts in more detail. Some of the reviewed studies used a set of communication strategies and researched their impact on students. It is acknowledged that the specific communication strategies that had the greatest potential to impact student behavior cannot be distinguished. When interpreting the findings, this is important to note. Further research could be focused on the impact of each specific communication characteristic on student behavior.

This study makes several contributions. First, it characterizes the complexity of student-centered communication that is used to respond to student behavior. Next, it presents specific communication strategies with definitions and sample statements. It also describes the impact of these communication practices on student behavior, engagement, and other areas. Overall, the study reaffirms the importance of student-centered communication responses to problem behavior in the classroom; it defines the communication that can teachers and student teachers use to handle problem situations in the classroom successfully with a positive impact on students and their behavior.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

JK contributed to the conception and design of the study, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and conducted the systematic review data gathering using the PRISMA protocol. JN wrote the sections of the manuscript and revised it critically. JN and JK contributed to the analysis of the data and their interpretation. Both authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This research was partially supported by Aktuální výzvy v profesi učitele 21. Století (Current challenges in the 21st Century Teaching Profession) (MUNI/A/1481/2020).

We would like to express our gratitude to Emeritus Laureate Professor John Hattie for his encouragement, advice, and feedback throughout the research process. We thank Shuzhan Li, Ph.D. for his valuable feedback on the final draft of the manuscript, and Dr. Louise Porter for her insights and feedback on the manuscript. Their contributions have been invaluable to the completion of this work. We would also like to express our gratitude to all the authors of the studies included in this review for their valuable contributions to the field and for allowing us to use their work in this review. We would like to extend our special appreciation to the authors who provided additional support and advice throughout this review. Their insights and expertise have been invaluable in shaping the findings of this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1156530/full#supplementary-material

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., and Haerens, L. (2018). Correlates of students’ internalization and defiance of classroom rules: A self-determination theory perspective. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 22–40. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12213

Alcruz, J., and Blair, M. (2022). Student-centered classrooms: Research-driven and inclusive strategies for classroom management. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., Göllner, R., and Trautwein, U. (2018). Student misbehavior and teacher well-being: Testing the mediating role of the teacher-student relationship. Learn. Instruct. 58, 126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.05.006

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., and Roth, G. (2002). Choice is good, but relevance is excellent: Autonomy-enhancing and suppressing teacher behaviours predicting students’ engagement in schoolwork. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 72, 261–278. doi: 10.1348/000709902158883

Auditor General Western Australia, (2014). Behaviour management in schools (no. 4). Available online at: https://audit.wa.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/report2014_04-BehaviourMgt-Amendment072015.pdf (accessed September 20, 2022).

Booth, A., Sutton, A., and Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review, 2nd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Brophy, J. (2006). “History of research on classroom management,” in Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues, eds C. M. Evertson and C. S. Weinstein (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 17–43.

Buckner, M. M., and Frisby, B. N. (2015). Feeling valued matters: An examination of instructor confirmation and instructional dissent. Commun. Stud. 66, 398–413. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2015.1024873

Burden, P. (2016). Classroom management: Creating a successful K-12 learning community, 6th Edn. New York, NY: Wiley.

Chesebro, J. L., and Lyon, A. (2020). Instructor responses to disruptive student classroom behavior: A study of brief critical incidents. Commun. Educ. 69, 135–154. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2020.1713386

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., and Ntoumanis, N. (2019). An intervention to help teachers establish a prosocial peer climate in physical education. Learn. Instr. 64:101223. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101223

Clunies-Ross, P., Little, E., and Kienhuis, M. (2008). Self-reported and actual use of proactive and reactive classroom management strategies and their relationship with teacher stress and student behaviour. Educ. Psychol. 28, 693–710. doi: 10.1080/01443410802206700

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 113–143. doi: 10.3102/003465430298563

Eisenman, G., Edwards, S., and Cushman, C. A. (2015). Bringing reality to classroom management in teacher education. Prof. Educ. 39, 1–12.

Emmer, E. T., and Evertson, C. M. (2012). Classroom management for middle and high school teachers, 9th Edn. London: Pearson.

Estrapala, S., Rila, A., and Bruhn, A. L. (2020). A systematic review of tier 1 PBIS implementation in high schools. J. Pos. Behav. Interv. 23, 288–302. doi: 10.1177/1098300720929684

Fogelgarn, R. K., Burns, E. A., and Lewis, R. (2020). Hinting as a pedagogical strategy to promote prosocial behaviour. Educ. Action Res. 29, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1743333

Freiberg, H. J., and Lamb, S. M. (2009). Dimensions of person-centered classroom management. Theory Pract. 48, 99–105. doi: 10.1080/00405840902776228

Freiberg, J. H., Oviatt, D., and Naveira, E. (2020). Classroom management meta-review continuation of research-based programs for preventing and solving discipline problems. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 25, 319–337. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2020.1757454

Gokalp, G., and Can, I. (2021). Evolution of pre-service teachers’ perceptions about classroom management and student misbehavior in an inquiry-based classroom management course. Action Teach. Educ. 44, 70–84. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2021.1939194

Goodboy, A. K., and Myers, S. A. (2008). The effect of teacher confirmation on student communication and learning outcomes. Commun. Educ. 57, 153–179. doi: 10.1080/03634520701787777

Gordon, T., and Burch, N. (2003). Teacher effectiveness training: The program proven to help teachers bring out the best in students of all ages. New York, NY: Crown.

Hargreaves, D. (2007). “Teaching as a research-based profession: Possibilities and prospects (The teacher training agency lecture 1996),” in Educational research and evidence-based practice, ed. M. Hammersley (Milton Keynes: Open University Press), 3–17.

Hart, R. A. (2010). Classroom behaviour management: Educational psychologists’ views on effective practice. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 15, 353–371. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2010.523257

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning, 1st Edn. London: Routledge.

Hepburn, L., and Beamish, W. (2019). Towards implementation of evidence-based practices for classroom management in Australia: A review of research abstract. Austral. J. Teach. Educ. 44, 82–98. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2018v44n2.6

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fábregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., et al. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of copyright (# 1148552). Gatineau, QC: Canadian Intellectual Property Office.

Jang, H., Reeve, J., and Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 588–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019682

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., and Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 643–680. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626799

Kunter, M., Baumert, J., and Köller, O. (2007). Effective classroom management and the development of subject-related interest. Learn. Instruct. 17, 494–509. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.002

Kwok, A. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ classroom management beliefs and associated teacher characteristics. Educ. Stud. 47, 609–626. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1717932

LaBelle, S., Martin, M. M., and Weber, K. (2013). Instructional dissent in the college classroom: Using the instructional beliefs model as a framework. Commun. Educ. 62, 169–190. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2012.759243

Larrivee, B. (2005). Authentic classroom management: Creating a learning community and building reflective practice, 3rd Edn. London: Pearson.

Lewis, R., Romi, S., Qui, X., and Katz, Y. J. (2005). Teachers’ classroom discipline and student misbehavior in Australia, China and Israel. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 729–741. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.008

Madden, L. O. B., and Senior, J. (2017). A proactive and responsive bio-psychosocial approach to managing challenging behaviour in mainstream primary classrooms. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 23, 186–202. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2017.1413525

Miller, A., Ferguson, E., and Byrne, I. (2000). Pupils’ causal attributions for difficult classroom behaviour. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 70, 85–96. doi: 10.1348/000709900157985

Miller, A. N., Katt, J. A., Brown, T., and Sivo, S. A. (2014). The relationship of instructor self-disclosure, nonverbal immediacy, and credibility to student incivility in the college classroom. Commun. Educ. 63, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2013.835054

Ming-Tak, H., and Wai-Shing, L. (2008). Classroom management: Creating a positive learning environment. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

OECD (2019). TALIS 2018 results (volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. Paris: TALIS, OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

Oliver, R. M., Wehby, J. H., and Reschly, D. J. (2011). Teacher classroom management practices: Effects on disruptive or aggressive student behavior. Campbell Syst. Rev. 7, 1–55. doi: 10.4073/csr.2011.4

Omoteso, B. A., and Semudara, A. (2011). The relationship between teachers’ effectiveness and management of classroom misbehaviours in secondary schools. Psychology 2, 902–908. doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.29136

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Paramita, P. P., Sharma, U., Anderson, A., and Laletas, S. (2021). Factors influencing Indonesian teachers’ use of proactive classroom management strategies. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 1–19. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1916107

Paramita, P., Anderson, A., and Sharma, U. (2020). Effective teacher professional learning on classroom behaviour management: A review of literature. Austral. J. Teach. Educ. 45, 61–81. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2020v45n1.5

Peterson, R. F., Loveless, S. E., Knapp, T. J., Loveless, B. W., Basta, S. M., and Anderson, S. (1979). The effects of teacher use of I-Messages on student disruptive and study behavior. Psychol. Rec. 29, 187–199. doi: 10.1007/bf03394606

Porter, L. (2014). A comprehensive guide to classroom management: Facilitating engagement and learning in schools, 1st Edn. London: Routledge.

Roache, J., and Lewis, R. R. (2011). Teachers’ views on the impact of classroom management on student responsibility. Austral. J. Educ. 55, 132–146. doi: 10.1177/000494411105500204

Romi, S., Lewis, R., and Katz, Y. J. (2009). Student responsibility and classroom discipline in Australia, China, and Israel. Compare 39, 439–453. doi: 10.1080/03057920802315916

Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. Future Child. 27, 137–155. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0007

Snilstveit, B., Oliver, S., and Vojtkova, M. (2012). Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J. Dev. Effect. 4, 409–429. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2012.710641

Steinberg, M. P., and Lacoe, J. (2017). What do we know about school discipline reform? Educ. Next 17, 44–52.

Talvio, M., Lonka, K., Komulainen, E., Kuusela, M., and Lintunen, T. (2014). The development of teachers’ responses to challenging situations during interaction training. Teach. Dev. 19, 97–115. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2014.979298

Vansteenkiste, M., Sierens, E., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Dochy, F., Mouratidis, A., et al. (2012). Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: Associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learn. Instruct. 22, 431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.04.002

Vongalis-Macrow, A. (2009). The simplicity of educational reforms: Defining globalization and reframing educational policies during the 1990’s. Int. J. Educ. Pol. 3, 62–80.

Wallace, T. L., Sung, H. C., and Williams, J. D. (2014). The defining features of teacher talk within autonomy-supportive classroom management. Teach. Teach. Educ. 42, 34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.04.005

Weger, H. (2017). Instructor active empathic listening and classroom incivility. Int. J. Listen. 32, 49–64. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2017.1289091

Weinstein, C. S., and Romano, M. (2018). Elementary classroom management: Lessons from research and practice, 7th Edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Keywords: communication skills, classroom behavior management, student-centered, systematic review, communication strategies

Citation: Karasova J and Nehyba J (2023) Student-centered teacher responses to student behavior in the classroom: A systematic review. Front. Educ. 8:1156530. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1156530

Received: 01 February 2023; Accepted: 17 March 2023;

Published: 12 April 2023.

Edited by:

Linda Saraiva, Polytechnic Institute of Viana do Castelo, PortugalReviewed by:

Elizabeth Fraser Selkirk Hannah, University of Dundee, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Karasova and Nehyba. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jirina Karasova, ai5qLmthcmFzb3ZhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.