- Faculty of Education, Southern Cross University, Gold Coast, NSW, Australia

The early childhood environment influences a young child's growth, wellbeing, and development, and the young child's environment determines lifelong outcomes. The impact of the environment on children's developing brain capacity has been shown to affect the hard wiring that occurs in the 1st years of life. Brain development in the early years is shaped and formed in response to environmental experiences. The learning environment in early childhood education and care (ECEC) services is designed by the early childhood educators—for example, by establishing and implementing routines, deciding on how to resource the environment, and developing and maintaining relationships with children, families, and staff. The Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) has developed and implemented a national quality standard (NQS) that addresses the quality of the learning environment in ECEC services. The NQS comprises seven quality areas that early childhood educators implement. Even though early childhood educators are the key decision-makers in implementing quality learning experience for children, their perspectives on the NQS have not been heard. This study presents the early childhood educators' perspectives on the characteristics of long day care (LDC) centers (for children aged from birth to 5 years) that they perceived to be important for provision of high-quality ECEC. Findings are presented from 15 interviews with early childhood educators regarding their perspectives of what characteristics enabled their LDC center to be assessed as Exceeding the NQS, one of the highest quality ratings possible. Findings indicate that the educator characteristics and their qualities in leadership and teamwork were important in determining high-quality ECEC. However, while the educators' attributes were deemed important, it was clear that there was an interconnectedness of factors including the relationships between children, families, and educators, the financial capacity, the governance, and structure of the LDC center that contributed to the provision of high-quality ECEC. Recommendations are that LDC centers could be incentivised to provide professional learning for staff leadership, teamwork, and capability to provide high-quality ECEC.

Provision of quality ECEC in Australia

Research has shown that investment in high-quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) produces significant return for society over the long term (Heckman, 2013). Across the world, there is consensus that the quality of early childhood programmes has beneficial and long-lasting effects on children and society (Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD), 2018), while the competence of the workforce is a salient predictor of ECEC quality (Urban et al., 2012). What the early childhood educator does influences the children's experiences in the early childhood setting and impacts the quality of the learning opportunities for children (Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD), 2018; Manning et al., 2019). Yet, it is unclear from research what early childhood educators perceive to be important in the provision of high-quality ECEC.

In Australia, the quality of ECEC is recognized as being of critical importance (Pascoe and Brennan, 2017; Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD), 2019). Evidence suggests that high-quality ECEC supports children's optimal development, wellbeing, and educational outcomes (Sylva et al., 2014; Melhuish et al., 2015; The Front Project, 2019; Wylie, 2019). High-quality ECEC also contributes to society's productivity and social capital (Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD), 2018). Quality ECEC is viewed as a multi-dimensional concept that supports children's outcomes; it is temporal and contextualized within societal conditions (Dahlberg, 2013). Constructs of quality ECEC that include the experiences of children, families, and educators; interactions between stakeholders; the structural conditions such as staff-to-child ratios, group size, and staff qualifications; and the process aspects of quality such as interactions are critical to understand the multifaceted aspects of quality of an early childhood setting.

Despite the perceived benefits of quality ECEC, definitions of quality are elusive owing to its subjective nature (Pianta et al., 2016). Even though there is not agreement on a definition of quality ECEC, evidence highlights the importance of high-quality ECEC (Organisation for Economic and Cooperative Development (OECD), 2012; Tayler, 2012; Melhuish et al., 2015). As a result, the Australian government has invested heavily to support children's learning and development with the establishment of the National Quality Framework (NQF) that resulted from the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) (2008) Partnership Agreement. The NQF aims to raise the provision of quality ECEC with continuous improvement embedded in the implementation of a national law and national regulations, the Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) (Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations, 2009), a National Quality Standard (NQS), and a national quality assessment and rating (A&R) process (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023).

The national quality framework assessment and rating process

ACECQA is the statutory body responsible for the implementation of the NQF. The NQF applies to ECEC services who receive funding from the government to operate. Services include long day care services (LDC) (for children aged from birth to 5 years), preschools/kindergartens for children aged from 3 to 5 years, family day care where children are cared for in an educator's home, and outside of school hours care for primary school aged children from 5 to 12 years. The focus of this study was on LDC services.

ECEC services in Australia are assessed for the provision of quality under an Assessment and Rating (A&R) process against the NQS. The NQS is a comprehensive guide with seven quality areas that LDC services are required to meet. They are Quality Area QA1: the educational programme and practice; QA2: children's health and safety; QA3: the physical environment; QA4: staffing arrangements; QA5: relationships with children; QA6: collaborative partnerships with families and communities; and QA7: governance and leadership (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023). Within each quality area are relevant standards and elements that guide ECEC services' quality practice.

The A&R process commences with the ECEC service developing their Quality Improvement Plan (QIP), a plan that highlights the LDC service's strengths and areas for improvement. Services submit the QIP to ACECQA within 4 weeks of this notification, and the authorized officer visits 5 to 8 weeks later. An authorized officer, representing the regulatory authority of the jurisdiction, visits and assesses the ECEC service during the A&R process.

The authorized officer observes practices and the environment, discusses policies and procedures with staff, reviews documents pertaining to quality practice, and completes an A&R report of the seven quality areas of the NQS (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023). The LDC center is assessed at one of four quality ratings: Exceeding, Meeting, Working Toward the NQS, or Significant Improvement Required. Assessment occurs every 3 years for services who receive an Exceeding the NQS rating; every 2 years for the Meeting rating; and every year for services who received the rating of Working Toward achieving the NQS.

In late 2022, 88% of Australian ECEC services were assessed as Meeting or Exceeding the NQS rating (Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2022). Five years ago, just 73% of services were assessed as Meeting the NQS rating (Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2022) demonstrating the significant improvement of provision of quality of ECEC. Yet, only 27% of these services achieved a high-quality rating of Exceeding the NQS rating. Furthermore, there were 12% of services that did not meet the NQS, that is, they had a rating of Working Toward the NQS or Significant improvement required (Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2022). This falls short of the NQF goal to provide quality ECEC for all children (Fenech et al., 2012) 10 years after the implementation of the NQF. Specifically, a study undertaken by Harrison et al. (2023) shows that Meeting and Exceeding the NQS rating is more likely associated with not-for-profit providers of ECEC, compared to for-profit.

The NQF was developed to align with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2006) recommendations. A criticism of the NQF has been that the NQF is “dependent on international research evidence and ideological argument” (Ishmine et al., 2009; p. 718). Early childhood research that takes account of the Australian context and characteristics has been limited regarding the provision of high-quality ECEC. This study makes a key contribution to this research gap by investigating the characteristics of Australian LDC centers who achieved an Exceeding the NQS rating from the perspective of the LDC centers' early childhood educators. In the context of this research, Exceeding the NQS rating is considered to be providing high-quality ECEC.

High-quality ECEC

Characteristics of high-quality ECEC across the Western world have focussed on the structural and process quality features of the ECEC service (Bennett, 2008). Structural quality is regarded as measurable and aligned to regulation, and so the most reported structural features characterizing structural high-quality ECEC are educator qualifications, children's group sizes, and the staff-to-child ratios (Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD), 2017; Manning et al., 2019). These features are related to child outcomes which are included in most western countries' regulations and the foundation for process features of quality. Process features of quality include the staff-to-child interactions and relationships; staff and family interactions and relationships; and staff-to-staff interactions and relationships (Pianta et al., 2016; Tayler et al., 2016). The process features of quality are impacted by the staff characteristics, including staff leadership (Gibbs, 2020), staff governance and management (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023), staff wellbeing (Logan et al., 2020), and work conditions (Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD), 2018; Manning et al., 2019; Fenech et al., 2021).

Researchers agree that the provision of a quality ECEC programme is significantly impacted by leadership (Siraj-Blatchford and Manni, 2006) and that leadership supports children's learning outcomes (Colmer et al., 2015; Gibbs, 2020). Distributed leadership was identified by Gumus et al. (2016) as most frequently contributing to quality ECEC, building on Siraj and Hallet's (2013) view that leadership is a “relational and communal concept where all can be a leader and engage in leadership, benefit from leadership and exercise power and individual agency” (p. 10). Thus, leadership in ECEC is not solely about one person being the leader with others following, but rather all educators engage in contributing to quality ECEC.

What the staff bring to their ECEC role influences process quality. The individual staff attributes, or strengths, are intangible and often are “hidden” characteristics of high-quality ECEC. Attributes that have been identified as important for ECEC educators in their roles include motivation, enthusiasm, values, and complex decision-making (Cleveland and Krashinsky, 2005); practical wisdom that includes expert knowledge, appropriate judgement, thoughtful action, and autonomy (Goodfellow, 2003); and communication, listening, managing effective communication, reflection, passion, and emotional intelligence (McMahon, 2017). Specific staff attributes that relate to how the team functions, which in turn has been found to reduce absenteeism and consequently increase productivity (Haslip and Donaldson, 2021). The staff attributes are likely to make a strong contribution to the teamwork of an ECEC center so that common goals are enacted.

ECEC teamwork

Being a leader means that there is a team of people with whom the leader works. Teams are viewed as being of key importance for the success of organizations (Delice et al., 2019). Working in a team means that all educators work together toward a common goal, and in the case of working in an LDC center, the goal is to provide high-quality ECEC. The NQS defines team collaboration as being

“based on understanding the expectations and attitudes of team members, and build on the strength of each other's knowledge, help nurture constructive professional relationships” (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023, p. 215).

Teams face constant challenges, and being able to adapt team practices as challenges arise is a measure of a successful team (Delice et al., 2019). Undergoing the A&R process is one such challenge the LDC center ECEC teams face. If team members change, then this is likely to pose challenges to the team's existing operations, until the team “gels” again. This is a key concern for LDC centers in Australia as the early childhood sector has reported to have up to a 30% attrition rate in 2020 (The Front Project, 2019).

In ECEC centers in Australia, all educators are likely to make an important contribution to the quality of the early childhood programme, and all educators are considered to influence children's learning and development. Within this context, the practices and expertise of all educators in early childhood settings matter. The educators' approach to their work impacts the quality of the early childhood programme. Early childhood educator teams are comprised of differently qualified staff: Staff may have an early childhood teacher's (ECT) degree from a university, or a Diploma or Certificate III in early childhood education, but most research on the impact of provision of quality ECEC has focussed on degree qualified early childhood teachers and directors (e.g., Urban et al., 2012; see Manning et al., 2019), with little research attention given to the views of the other educators who are essential to the ECEC team. It is unclear from past research what the (non-teacher) educators' perspectives are about working toward provision of quality ECEC owing to the focus upon early childhood teachers. Yet all educators are part of the team who provide the ECEC, and so their perspectives are important. Furthermore, research from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) has shown that the staff qualified with either a Diploma of ECEC or an early childhood degree (that is teachers) delivered similar outcomes for children (Warren and Haisken-DeNew, 2013). The provision of high-quality ECEC is likely to be a team effort, not just the result of the early childhood teachers.

Within Australia, the context of this research, LDC centers are required to be open for a minimum of 8 h per day, and 48 weeks per year with each staff member holding an ECEC qualification (Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2022). Qualified ECTs usually work less hours compared to Diploma or Certificate III staff, for financial reasons, yet it is the Diploma and Certificate III ECEC trained educators who are required to be present at all times the LDC is open for children to attend. The National Education and Care Services Regulations state that teachers need to be present for a certain number of hours per week, depending on the number of children at the service. This may vary across jurisdictions—for example, in the state of New South Wales (NSW), a center with < 25 children per day is required to have a trained teacher for 20% of the opening time, while a LDC center with 25 to 59 children is required to have an ECT for at least 6 h per day (NSW Legislation, 2023). ECTs often only work during the middle part of the day, from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.; therefore the Diploma or Certificate III educators have the important role at the beginning of the day, of setting up the learning environment to make it welcoming, stimulating and safe, and communicating with families when children are dropped off. At the end of the day, these educators are often tasked with sharing the child's day with the family and packing up the environment. These educators work with fellow team members throughout the day to provide quality ECEC for the children. Thus, it is the whole team that impacts the provision of high-quality ECEC not just the ECTs. The research presented in this study includes the perspectives of educators both trained teachers and those with Diplomas or Certificates of ECEC.

Governance and management of LDC centers

The governance and management structure supports educators to achieve the common goals outlined in the philosophy of the LDC center. Specifically, working effectively as a team requires staff to work professionally together on a shared goal, which in the case of this study, was the provision of high-quality ECEC. The NQS (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023) stresses the importance of the ECEC team having a shared vision guided by the LDC center's philosophy so that all educators will own the philosophy and be committed and willing to enact it in their service's practices. Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA) (2023) explain in the NQS, QA7, that the ECEC service's philosophy statement has three purposes being that the philosophy:

1. “underpins the decisions, policies and daily practices of the service;

2. reflects a shared understanding of the role of the service among staff, children, families and the community; and

3. guides educators' pedagogy, planning and practice when delivering the educational program” (p. 282).

Quality Area 4.2 of the NQS clearly delineates that professionalism is achieved when staff operate in a team which in turn contributes to quality ECEC. As stated in the NQS (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023):

“When adults communicate effectively and respectfully with each other they promote a positive and calm atmosphere at the service, supporting children to feel safe and secure and contributing to the development of positive relationships between children and educators. Unresolved and poorly managed conflict between adults in the service affects morale and impacts on the provision of quality education and care to children (p. 215).”

So that provision of high-quality ECEC is possible, the ECEC service's management structure is required to support the educators' work. Not-for-profit, community-based services have been found to demonstrate higher levels of quality than for-profit services and corporate services (Cleveland and Krashinsky, 2009; Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2022; Harrison et al., 2023) which may suggest that these management structures have higher qualified staff, better staff-to-child ratios, and/or stronger staff retention. A service's governance and management structure may influence staff wellbeing and retention, because of work conditions, including wages, and paid time away from children for programming (Fenech et al., 2021). Research shows that children's outcomes are better achieved in services with lower staff turnover rates, and better working conditions owing to the impact upon staff wellbeing (Logan et al., 2020). Additionally, the wellbeing of ECEC educators has been found to impact the learning environment for children, with wellbeing related to lower staff turnover rates potentially affecting the quality of the educators' professional practices (Irvine et al., 2016; Bonetti and Brown, 2018; Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD), 2018). If educators do not feel that their vision for provision of high-quality ECEC is shared in their workplace, then this is likely to impact the educators' wellbeing, and the subsequent provision of quality ECEC for children will be impeded (Logan et al., 2020). Therefore, the management structures need to be such that staff feel supported.

Overall, research studies acknowledge that outcomes for children are likely to be an interplay of the structural, process and less tangible characteristics of quality ECEC (Press and Harrison, 2012; Bonetti and Brown, 2018). The intent of the A&R process is to determine the quality of ECEC by capturing the interplay of these features, but little is known about the characteristics of the LDC center's provision of high-quality ECEC from the educators' perspectives. This study presents findings from a study that investigated the characteristics of five LDC centers from the educators' perspectives that achieved a high-quality rating of Exceeding the NQS under the A&R process of the NQS.

Research aims and theoretical framework

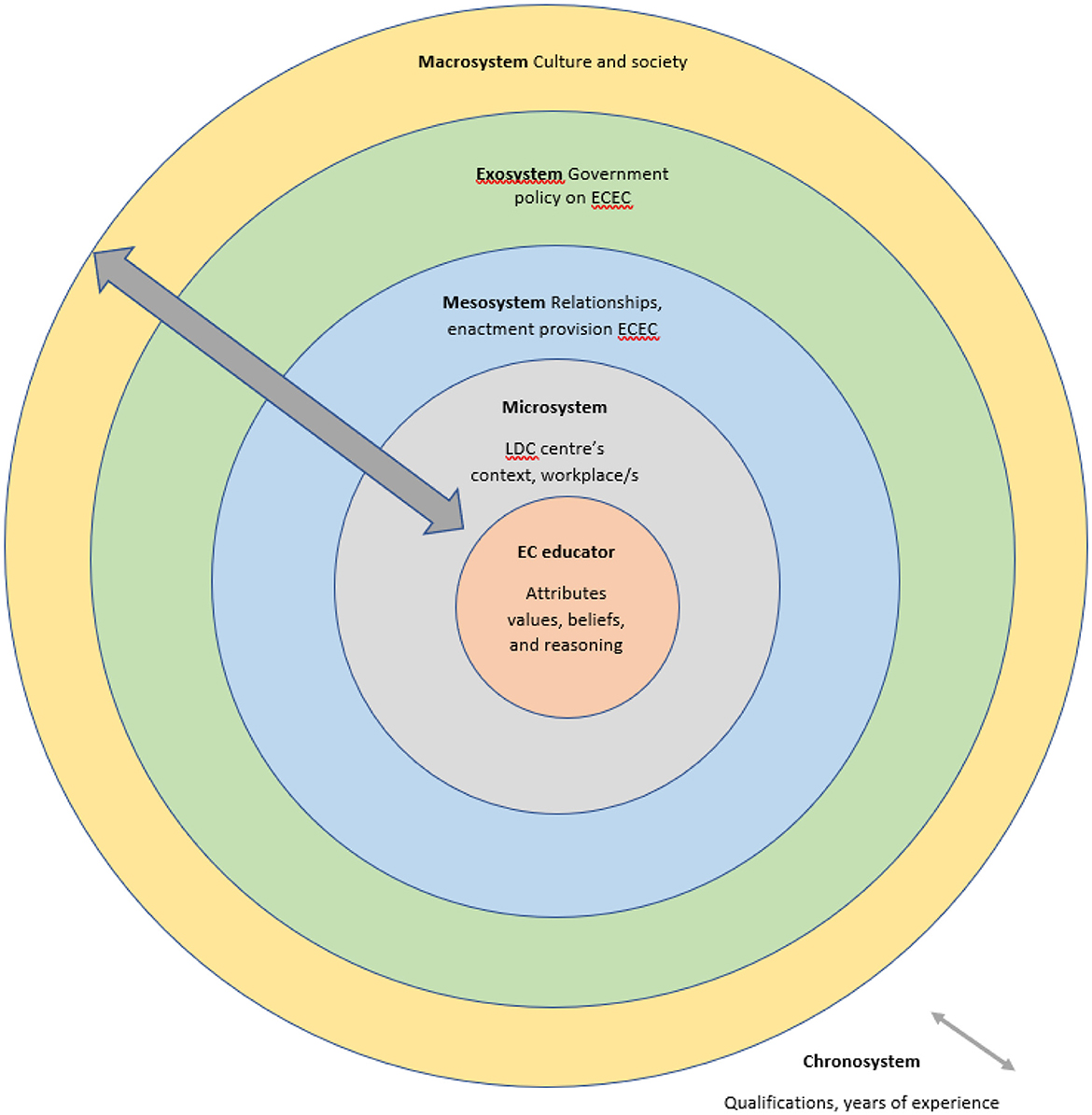

This study reports on the characteristics of five LDC centers that had achieved an Exceeding the NQS rating from the educators' perspectives who worked in each center. Bronfenbrenner's ecological system theory (1974) was chosen as the theoretical framework for this research as it aligned with the research aims and the research approach. This theoretical approach brings a contextual basis to understanding each LDC's service, within a system that is strongly influenced by the educators, families, and community within that context, set amidst the regulatory requirements for operating a LDC within Australia (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ecological systems of educators in ECEC centers (adapted from Bronfenbrenner, 1974).

For this study, the early childhood educators are at the center of the Bronfenbrenner model as they are the key players who make the decisions to enact ECEC. The educators bring to their work in the LDC center their beliefs about the provision of quality ECEC, their own dispositions, qualifications, and experience, and their socio-cultural background. Around the educator is the mesosystem representing the relationships within the LDC context with the children, colleagues, families, service governance, and local community. The mesosystem is where educators influence and are influenced by children through the relationships they enact; where educators can influence and are influenced by each other as they work together implementing the center philosophy; and where educators and families cooperate together for optimal children's learning and development. Relationships are bi-directional where each person within the microsystem can impact another person's learning and perspectives and are influenced by the interplay with management.

The exosystem is comprised of the context of the LDC center—for example, the community in which the service operates, the families in the local community, and the rural, remote, or urban context. The macrosystem is comprised of ACECQA, which includes the national regulations, the national quality framework, and associated national quality standard; and the culture and customs of the society. These systems are never static, represented by the chronosystem, with ongoing changes being experienced within the system—for example, changes in staff, management/ownership of the LDC center, legislation.

Methodology

Procedure and participant selection

The study adopted a qualitative approach to investigate the characteristics of LDC centers that were rated as Exceeding the NQS, from the perspectives of the early childhood educators. Five LDC centers were purposively chosen from ACECQA's National Register. The LDC centers invited to participate represented services across jurisdictions that had met Exceeding the NQS rating. As previously mentioned, in the context of this study, Exceeding the NQS rating is regarded as being high-quality ECEC. This research was interested in LDC centers that were assessed as Exceeding the NQS rating.

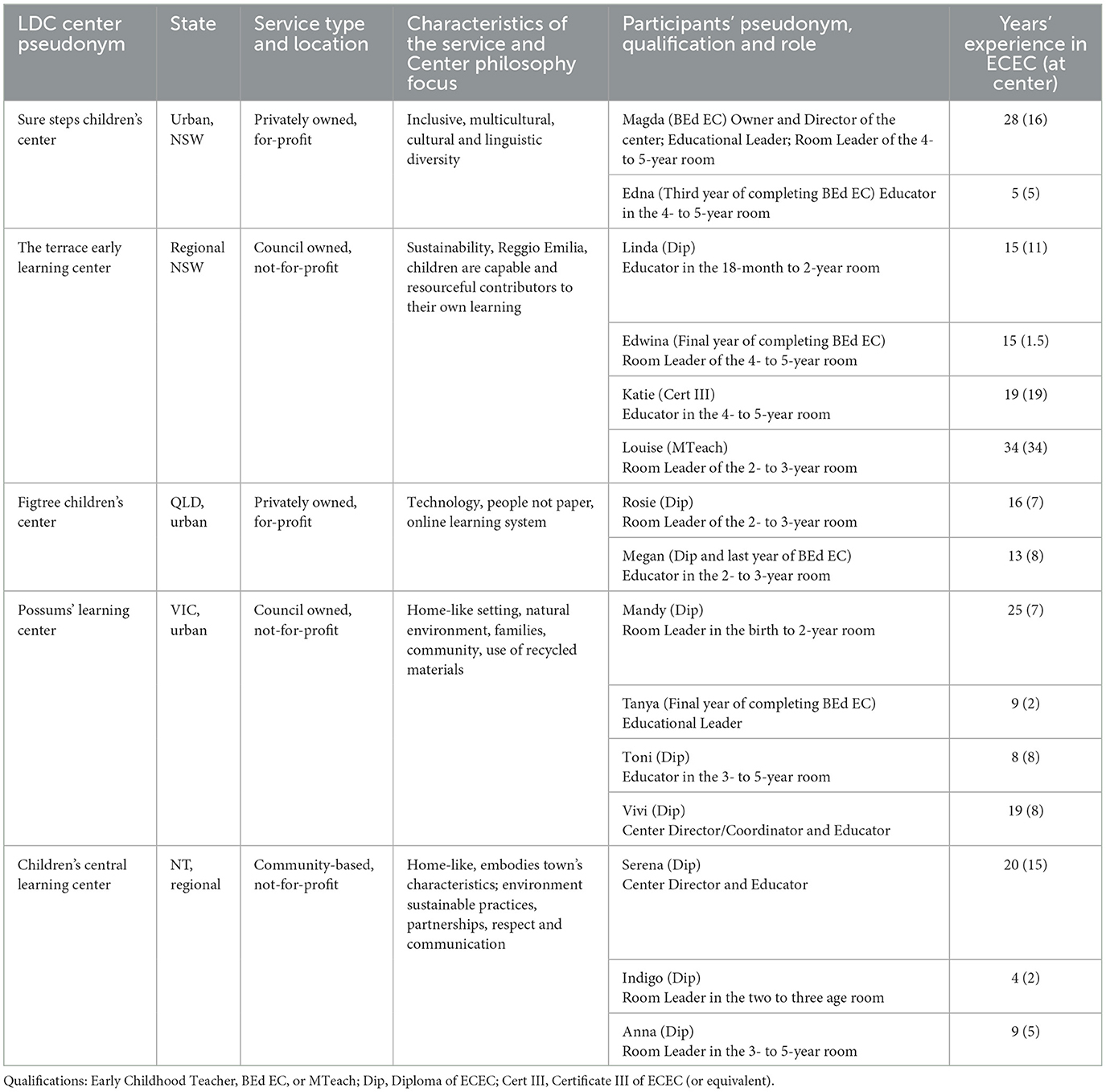

Overall, 15 educators were recruited from the five LDC centers that achieved an Exceeding the NQS rating. The LC centers were located in four Australian jurisdictions and had different contexts and philosophical backgrounds. Table 1 illustrates the five LDC centers' different characteristics and the participants' qualifications, experience, and position at the time of the study.

After the recruitment process was finalized, the Director of each center was emailed an initial questionnaire to complete about the center's operation, governance, management, enrolments, and staff-to-child ratios. The participants were also emailed a questionnaire that asked questions relating to their age, experience in ECEC and the LDC center, their qualifications, and their role in the center. Questionnaires were completed before the interview so that the researcher had prior knowledge of the center and participants. The 15 educators were interviewed following ethics approval (approval number 2014/381). Pseudonyms have been used for all LDC center names and their educators. This article presents findings from a doctoral study of the lead author, Phillips (2020).

Semi-structured interviews were deemed to be the most appropriate data collection method to obtain deep insights of the participants' perspectives of what they believed were their LDC center's characteristics which led to the Exceeding the NQS rating. The interviews enabled the educators to use their own language and to report on a range of experiences (Leavy, 2017). Each participant was interviewed once, face to face, at their LDC center, at a mutually convenient time in a quiet space. Most interviews were approximately 30 min, were audio recorded, and then transcribed.

Interview questions

The semi-structured interviews focussed on how the educators prepared for the A&R process; how they felt about the feedback from the authorized officer; the characteristics of the LDC center that contributed to achieving an Exceeding the NQS rating.

Analysis of data

Interview transcripts were analyzed applying Braun and Clark (2006) guide to thematic analysis which has six phases:

Familiarization of the data

At the first phase, interview data were transcribed and then read and re-read until they were completely immersed in the data. Interesting points and initial ideas were noted.

Generating initial codes from the data

At this stage, codes were developed inductively from the interview data, meaning without attempting to fit into an existing code frame. Meaningful extracts relevant to the research aim were highlighted on the interview transcripts in a word document and given an initial code name. Initial code names were collated into a list of codes, and definitions were developed for each code.

Searching for themes

The third phase of analysis involved the identification of themes and collecting all relevant codes within each theme. Themes were developed inductively in the first instance. Second, themes were developed deductively using the reviewed literature and Bronfenbrenner's ecological system theory (1974) as a lens. The code cards were then organized into deductive theme piles.

Reviewing themes

This stage involved reviewing all coded data extracts. All coded extracts were printed and compiled into their relevant theme. The theme document was read and re-read to ensure that the theme formed a coherent pattern. Some codes were added to themes that were not considered to fit in the first stages of analysis emerging, and some codes that appeared not to fit well were removed or applied to other themes.

Defining and naming themes

Each final theme was given a definition. Theme names and definitions were cross checked between researchers.

Reporting findings

As the research aimed to investigate educators' perspectives of their LDC center's high-quality characteristics, seven themes were defined from the data as follows:

1. Educators' characteristics.

2. Relationships within the LDC center.

3. Teamwork and leadership.

4. Financial status and investment in high-quality ECEC.

5. The LDC center's governance and associated work conditions.

6. Understanding and preparing for the A&R process.

7. The interconnection between quality characteristics.

Findings

Each of the seven themes cites excerpts from the participants' interviews. A discussion of the theme, with supporting quotes, is presented in the following section.

Theme 1: educator characteristics

Across each LDC center, the characteristics, dispositions, and skills of the educators were raised as key for the provision of high-quality ECEC. Every educator identified that staff were the key asset to obtain the Exceeding the NQS rating. Effective communication skills, honesty, professionalism, passion, respect, flexibility, ethics, and having knowledge and confidence in one's role were perceived as vital educator attributes. Furthermore, the data revealed that an important educator characteristic was an intrinsic and shared drive for high-quality ECEC. This theme is broken down into three sub-themes of educators being reflective, flexible, and ethical; educators being effective communicators; and educators being knowledgeable and committed to the ECEC center's context. These themes are now presented with supporting data.

i) Educator professional qualities of being reflective, flexible, and ethical were raised as being important in the interviews. Linda explained that an educator needs to be passionate and focussed on provision of quality ECEC as well as being a reflective and an ongoing learner was important:

“Most of the people I think about who are great educators I think passion is a big part of it, having a real passion for it, but also that ability to reflect and to be humble enough to say I don't know everything and in fact there are some things that I don't know very well at all. But I can learn from the children and it's about being a learner as well as a teacher. The more we learn the more you know what you don't know.”

Building on this theme of engaging in ongoing learning, Katie explained that she thought teachers needed to be able to change and assess the culture and the context of the LDC center they work in, as she explained:

“Teachers (need to be) prepared to change…You know you can have a teacher who has their degree and got it 30 years ago but there has been a lot of change in ECEC and the way it is approached now compared to 30 years ago has changed so much in that time. So to me a really good teacher is somebody that is able to look at that change and approach it. Also, a teacher that is able to look with open eyes at the culture and context and how they see themselves within not just the center but the community.”

The need to be an ethical educator was raised by Magda. Magda explained how prior to change in the NQS the LDC center was assessed by families, and the LDC center sent a questionnaire to families to complete. If the educators were unethical, this documentation could be fabricated as Magda stated:

“I thought that the families and community part of things was interesting. They (the assessor) receive this information via us because you can't really observe it. So, if I wanted to make it up, I suppose I could…. I mean let's face it in any system if someone wants to be unscrupulous, unethical they can.”

Overall, the need to be confident in your role as an educator was a characteristic that was raised. Being confident meant that you knew what you were doing and knew how to do it professionally and to work alongside your colleagues. Tanya explained that:

“Being confident in what you are doing (is important) but to be confident you have to have good relationships with staff and families and children. That helps you to be confident as an educator.”

ii) Effective communication: The following quotes identify the key attribute of being an effective communicator. Linda explained that:

“We have very honest relationships with families…. with open communication both verbal and written…..You need to be nurturing and have a caring nature and understanding, listening to the children, and what their interests are.”

Indigo, speaking generally, identified that being empathetic and open-minded was important:

“…being able to take another person's perspective is important, being open-minded…always striving to learn, ongoing learning a good observer… and giving time to children”

Being respectful, understanding, and passionate about the work of an educator was raised as a characteristic by Toni, with other qualities included by Toni as being:

“respectful of the children's needs and wants and understand that what we are doing here is about education and learning not just about babysitting so it is that balance of having that warmth and nurturing but also providing a rich play-based learning environment also working with parents quite closely to make sure all needs are being met.”

Finally, listening was a key skill to being an effective communicator. As Katie explained:

“Listening is a big skill. Listening to families, listening to the children, listening to staff and what they are actually saying. And I don't mean listening on a superficial level, I mean really listening to what they are saying and understanding what they are saying.”

iii) Knowledge of, and commitment to, the LDC center's context: The educators spoke about how they ensured that the educators were committed to the LDC center philosophy and had an in-depth knowledge of the children, families, and LDC context. Representative of this process across each of the five LDC centers is Edna's comment as she explained:

“We had one whole center staff meeting which focused mainly on our philosophy which is where we started the whole process was really getting back to the basics of what is our philosophy, what is important to us in our service and caring for our children and what kind of place do we want to be and then we sort of used that as a bit of a framework really for reflecting on what we are doing, so this is what we want, this is what we hope we are, and if is this actually happening within our daily practice with children and so we used that to reflect on our practice.”

Theme 2: relationships within the LDC center

Essential characteristics of the LDC center achieving an Exceeding the NQS rating were the presence of strong and respectful relationships within the LDC center. The educators explained how their respective centers practiced relationships with children, families, and each other and that this characterized their center's provision of high-quality ECEC. The educators highlighted how the depth of these relationships that indicated “a sense of unity” was the most important characteristic within the LDC center.

Educators, children, and families were viewed as equal participants who had a united approach to the provision of high-quality ECEC. Ten educators identified how the staff had knowledge of each child and their family. Families continued to return to their LDC center with each child in the family, which exemplified how important relationships were between educators and families. Rosie explained that “you build such a big relationship with the parents and the children… they respect you and you develop a friendship with them.”

While the educators all indicated that relationships in their LDC center were an important characteristic of high-quality ECEC, differences existed within the relationships in each center highlighting that ECEC quality is contextually bound. For example, Linda explained that “staff here are all connected to the children” and “we have very honest relationships with families,” while Indigo stated that:

“Educators take pride to address the family and they know what is happening with individual families. We know when new siblings are born, the pup is at home, the cat is dying, families are moving… So that is personalized. Parents are their first educators and extend it to here (the service). I think looking at the center as an extension to what is done at home and marrying it to all families.”

The educators indicated that staff collaborated to prepare for the A&R process highlighting the need for respectful and effective collegial relationships within these LDC centers. Rosie put it like this:

“You have got to work together, and you can't be an individual working, you have just got to work together,”

while Indigo explained there were a lot of different areas in which the staff collaborated:

“…having those meetings, looking at the different standards and elements, ticking them off, making comments and basically collaborating together. That is basically what got us Exceeding.”

A sense of unity indicated alignment to the LDC center's philosophy as educators explained that they were “all on the same page”—a direct quote heard from three of the 15 educators. Educators expressed awareness of the need to “be on the same page” to provide consistent education and care across the LDC center. The following responses highlight this finding. Megan stated that

“The staff work well together there is none of this kind of split and divide. We all support each other. We all have reflections together … we all seem to be on the same page and we all have a similar kind of philosophy and goals.”

Similarly, Toni explained:

“Well, I think that all of us, not just me, that we really try and work together and that we try and listen to each other's opinions and that everyone gets a voice and discusses what is happening and why we are doing things the way that we do.”

Serena identified that educators may have different values but need to work together and align with the LDC center philosophy:

“We had a training session where (we were) talking about what we think our center's values are, you know because we all have different values and we have to think about where we all sit and if you are working in a center you have to believe in their philosophy and their values, or otherwise it is not going to work.”

Similarly, Vivi explained that

“For our center it is everyone being on the same page in a philosophical way because we do a lot on our philosophy, and I think it becomes very apparent if someone is not on that page…. A really good educator here will stand out because they fit in with our philosophy and it is consistent across all our rooms. You know you don't have one room working in one way and another room doing it another way; there sort of is a flow.”

Theme 3: teamwork and leadership

Following on from the importance that the educators identified the need for effective collaboration with colleagues, a key finding from the study was that teamwork and leadership were perceived as a significant characteristic of each LDC center for provision of high-quality ECEC. Educators at each LDC center identified that a collective approach to leadership, rather than having one identified leader, was important.

There were strong similarities across the five LDC centers regarding the way leadership was exercised: Each center had an educational leader and/or director responsible for implementing the center's philosophy, collaborating with staff on the QIP, and creating and supporting staff to implement consistent approaches to the center's philosophy. The educators talked about sharing roles and responsibilities, having a strong commitment to providing high-quality ECEC, with all educators' ideas valued. The team commitment to provision of high-quality ECEC was highlighted by Edna who stated:

“It's really wanting to provide the best early childhood service that we can and similarly making sure that the staff have that same kind of pride in their work. When staff have that pride they want their service to be recognized as a good service. It's a lot to do with their attitude toward work.”

Similarly, the director of Edna's center, Magda, highlighted how she managed ensuring each educator's voice, and their views were heard. Magda stressed how all staff made significant contributions—it was not just up to one staff member to lead but rather required teamwork, which as the leader was challenging:

“Every single member of our team contributed. But what then happens is that, for example, if you have 15 voices it's like a cacophony. So, I had to listen to and read each one of those voices…it looks like it is discordant but actually you're both coming from a different angle but not in conflict at all they are just coming at it from a different perspective. So that was a really difficult thing.”

Magda explained that having a shared commitment was key to the provision of high-quality ECEC as she stated:

“I think it comes back to the philosophy. I believe it becomes an amazing resource, I believe if there is not enough shared commitment and enough of a pool of shared values that becomes your philosophy then you are just pulling in different directions. You will know. You walk in to some places and you can feel that it is discordant, people are working hard in each separate room but there isn't a shared vision or a sense of something that is uniform and a thread that goes through.”

This process of addressing discordant views, but ensuring they were represented, was echoed at The Terrace Learning Center by Katie who stated:

“At times it has been challenging and confronting but I think that's brought out what we have needed to bring out. And yes, sometimes it has made some staff feel uncomfortable but I feel that because of our honesty, I feel like we have been able to nut through things, and the situations that have come up where we have needed to sit down and talk about it. I feel we have been good at that.”

Educators talked about sharing roles, feeling confident in their role, and being valued. The Terrace Learning Center team focussed upon how they demonstrated advocacy leadership through sustainable practices, showcasing them to the community, to improve the conditions of the environment for a sustainable future. The process of working together as a team presented challenges for the educators including the leaders; however, it was this characteristic of the LDC center's operation that the educators perceived was important for obtaining the Exceeding the NQS rating.

Theme 4: financial status and investment in high-quality ECEC

Investing financially in the LDC center and in staff capacity was perceived as a key characteristic of the provision of high-quality ECEC. Ongoing improvement was addressed by investing in obtaining, improving, and retaining the knowledge, skills, and resources needed for provision of high-quality ECEC. Explicit strategies were adopted to build financial capacity including applying for grants. Serena was noted by her staff for her grant writing ability, and success just prior to the interview, in obtaining a “large grant of $103,000 for equipment,” “new toys,” and “improvements to the outdoor area,” including “a bush tucker area.” Indigo, who was from the same center as Serena, had a strong interest in the environment as the third teacher and was allocated funding for improvement of Quality Area 3, the physical environment. She believed the environment was important for the provision of high-quality ECEC.

Four of the five LDC centers indicated that they aimed to provide financial capability for provision of high-quality ECEC, with Sure Steps Early Learning Center being the exception. The director of Sure Steps, Magda, did not demonstrate evidence of building financial capacity to improve service quality; however, she explained that having strong financial capacity was a very important major characteristic of high-quality ECEC, as she said

“if we are working on the premise that qualifications equals quality, (and) services who have the resources… the money, [and] can afford attractive working conditions are going to be able to have their pick and choose theoretically the best educators.”

This finding poses interesting questions for provision of high-quality ECEC in areas where funds are not readily available from the LDC center's management to invest in the center's capacity. The educators at each LDC center explained that the management of their center provided professional development opportunities for all staff- thus making a strong investment in staff capability. Training opportunities were deemed to have had significant impact on the provision of ECEC quality. At Possums Learning Center, all four educators interviewed spoke of the impact of attending a professional development day that they believed contributed to the LDC center's Exceeding the NQS rating. Vivi, the director, identified staff relationships and communication as requiring improvement and had organized an external professional expert to deliver staff relationship training. Mandy, one of the educators at Possums Learning Center explained that:

“(The professional learning day) was a huge turning point for staff. The in-service was about being assertive but in a very respectful way, eliminating the gossip… It taught [us to] just to go straight ahead and speak to the person that you need to speak to, and I think as soon as we did that… it opened up the ways for all of us to really communicate… Look I couldn't be happier. We literally just leapt and bounded ahead.”

Here, we see that the director identified the need for staff to address how they worked together as a team and communicated with each other, and thus, the professional learning day made a strong contribution to the staff capacity and skills. Quality Area 4 of the NQS has a focus upon:

“professional and collaborative relationships between management, educators and staff support continuous improvement, leading to improved learning experiences and outcomes for children (Australian Children's Education and Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2023, p. 202)”

which was evident in the approach undertaken by Possums Learning Center and is a key characteristic of Exceeding the NQS rating for this LDC center.

Theme 5: the LDC center's governance and associated work conditions

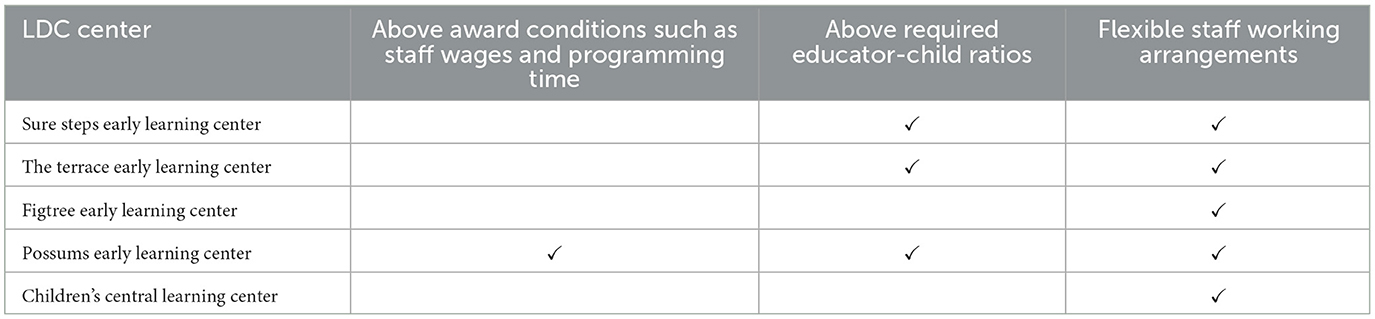

The data revealed that the LDC center's governance and management structure was found to be a key characteristic that educators identified in the provision of high-quality ECEC. As signaled in Table 1, there were various models of service governance and management structures across the five LDC Centers. The models of governance were identified in the initial questionnaire to directors and in interviews with the participants in the five LDC centers as shown in Table 2.

Educators' work conditions varied across the five LDC centers. The initial director questionnaire and interview data revealed that there was one LDC center who paid above award conditions, three LDC centers that had above the required staff-to-child ratios, and all LDC centers provided flexible work conditions for their staff (see Table 3. Educators in these LDC centers identified these particular working conditions as an important characteristic of high-quality ECEC.

The LDC center that provided all three “higher than required work conditions” was Possums Early Learning Center, a council-operated center. Vivi, the director, believed that educators provided with above award conditions provided a positive work environment as they feel valued and are “satisfied” with their job; they are also “highly motivated” and have “stronger relationships” within the LDC center. The governance and management of the center contributed to these above award work conditions as she said that having “a supportive parent run committee” who offer “above award conditions” on “staff wages,” “staff-child ratios,” and “programming time” resulted in the center's “happy and stable team with many staff being employed for 5–10 plus years at the center.”

Another council-operated LDC center, The Terrace Early Learning Center, also identified educator-child ratios above what was required in the regulations, which enabled educators to build strong relationships with children and their families. Offering staff flexible work arrangements was a characteristic of all LDC centers suggesting that having a positive working environment promoted provision of high-quality ECEC. For example, Toni from Possums Early learning Center said:

“Management promote flexible work arrangements, taking into account staff family commitments, health issues and study commitments.”

Anna from Children's Central Learning Center indicated that

“I've had some health problems recently and you know if I said to [the director] right now “my doctors rang and I need to go,” she would let me… and since I have been having problems with my throat she is going to move me to the babies room so I don't have to strain my voice as much… She is a very good director.”

These examples validate that the educators' home/work/life balance supports their wellbeing to contribute to the provision of high-quality ECEC. This is an important finding building on the previous findings that educators' attributes and capabilities were identified as important characteristics of high-quality ECEC.

Theme 6: understanding and preparing for the A&R process

It was clear from the interviews with the educators that having an understanding of the A&R process was considered essential. This theme speaks to the need for effective staff relationships, teamwork, and leadership that ensures all staff are united in their approach to provision of high-quality ECEC. Once educators were all on the same page; then, strategies for preparation for the A&R process were reported in all LDC centers. Educators talked about the meetings they were required to attend—some meetings were room meetings of all the staff who worked in that room; other meetings were whole of center meetings led by the director and/or the educational leader. At the many meetings held, the seven Quality Areas (QAs) of the NQS were discussed, identifying QAs where the staff of the LDC center felt that they were practicing at the Exceeding level and those that required improvement to obtain the Exceeding the NQS rating. This was identified in a variety of ways either led by the center's leaders, or as a collaborative process by all staff. The director led this process in Megan's center:

“Well the director pretty well did it but we were just told the areas that needed improving and we had access to it so that we could look and read any observations on the areas that we needed improving, read the plan and read the programs that were put in place to improve overall.”

In Anna's LDC center, the process was reported as being collaborative:

“It (preparation) obviously started in meetings. We would get together and we would look through each quality area. We used to come up with our strengths and our weaknesses that we wanted to work toward and so everyone would come up with them and we did find at the beginning that lots of stuff came out - we were sort of inundated actually with not so much of our weaknesses we were actually quite proud of our strengths. So, it was a very reflective process, even though I am sure for (leaders) it was quite a lengthy process but we as hands-on-staff felt like it was a really good process for us.”

For some staff, for whom it was a new process, the leaders assisted them to develop understanding of the process, as Serena stated:

“We came together to talk about what we hoped to achieve through this process because some (staff) hadn't been through the process before. So it was basically a new learning experience for them. So it was having a look and thinking now what are they doing? What would they like to do? What do they see as the gaps and we talked about each others' rooms as well, because sometimes you can't see what's in your own room. You are too close to it. For parent feedback, we do these surveys and sometimes I think ‘why do we do these' but they are really, really good. We have just got the last round back and we do that every time. We ask the parents what they would like.”

Anna, a member of Serena's staff, explained that this process was ongoing, with some additional work to prepare for the assessor's visit:

“We invited parents to come in and they were involved in a working bee and we cleaned up the center. We also updated folders and made sure they were up to scratch and ensuring that everything that was needed for the assessment was up on the wall and up to date and easy to access before the visit. Director did a lot of the paper work and we pretty much did the hard labor on the floor. It's an ongoing thing keeping this place running but it is that extra bit of work before the visit. We had the feeling that we were going to get Exceeding so we just had to make sure everything was up to scratch. Most of it was done anyway but it was trying to keep up with it.”

Some educators found the process provoked anxiety and stress, and others were quite relaxed about the process. Magda said:

“We were fairly anxious because it was a new process and therefore there was no feedback, and we were also very aware that Department of Education and Communities (staff) themselves were learning on the job as well. So there was no one to go by, you know now that we have been through it we can tell other services what it was like but we had no one to listen to.”

While Tanya stated:

“Assessment wasn't really nerve wrecking- it was an opportunity for us to review and reflect on our practice.”

There was agreement among the educators that being prepared was very important as highlighted by Magda who said:

“Being prepared at the very base line meant having everything that they require. If you don't have that and you have had time and you know that that is what they want at the very base line then you would be crazy and to have not done your homework that way. There is reflecting and summarizing where you are at now and then looking at what we are great at what we are not so great at and then thinking well how do we want to improve? And then how do we prioritize because you have this long list and that list could last you two years. So then you have to say well ok which ones are really important and why, and which ones are achievable, and which ones do we start now, and which ones are going to be long term.”

The educators identified that the preparation was part of ongoing improvement of practice as part of the operation of a LDC center, with adjustments required as new staff come on board, as Tanya stated:

“… the work is already done on a day-to-day basis so it is just a reflection on what we were doing already;”

Vivi said

“I think it is just constant improvement overall but I think it is about not getting to a point where you think well Ok we got Exceeding we will look at that in another three years' time …it changes all the time….it changes with the staffing team as well. Like this year we have quite a few new staff that weren't here last year and so the things that we feel we do really well in a lot of ways have changed and the things that we need to improve on have changed because it is different people.”

Theme 7: the interconnection between LDC center characteristics

An important theme that emerged from the data was that the LDC's characteristics were interconnected to be rated as Exceeding the NQS rating and providing high-quality ECEC. The LDC centers operated holistically, addressing all seven quality areas of the NQS. Vivi, from Possums Early Learning Center, asserted that “I don't think quality can be seen in separate areas.” The educators spoke of the attributes of their fellow educators, the teamwork and leadership in their LDC center, the governance and management's influence upon the provision of ECEC quality, and the need for all educators to be invested in provision of high-quality ECEC by being united, ‘on the same page' and to be prepared for the A&R process. The educators spoke about how being committed to provision of high-quality ECEC, with their effective communication skills, assisted to build relationships and partnerships with the children and families within the LDC center's context. What the educators bring to their work needs to be supported by governance and management that support the staff's work conditions, wellbeing, and investment in ongoing professional development.

Discussion and conclusion

This study investigated the characteristics of five Australian LDC centers that had been rated as Exceeding the NQS rating, considered equivalent to the provision of high-quality ECEC, from the perspectives of 15 educators who worked in those LDC centers. The findings indicate that, overall, the LDC centers' characteristics were interconnected and that educators need to have the common goal of provision of high-quality ECEC. The need for all educators to be committed to this common goal was evident in each LDC center. The educators' qualities and the operation of the LDC center's leadership and teamwork were necessary requirements to guide the LDC center's provision of high-quality ECEC.

Using the ecological systems model of Bronfenbrenner (1974) as the theoretical framework, the microsystem of the educator's attributes and characteristics was perceived to influence the provision of high-quality ECEC. The educators identified three educator qualities necessary to achieve the Exceeding the NQS rating. These qualities were being reflective, flexible and ethical practitioners; effective communication; and knowledge of and commitment to the LDC center's context. These educator attributes enabled teamwork to be undertaken leading to shared understanding of practices and provision of high-quality ECEC. This finding aligns with past literature, and educators were viewed as needing to be effective communicators (McMahon, 2017), honest, trustworthy, passionate, engaging in ongoing learning, respectful, professional (Cleveland and Krashinsky, 2005), flexible, and ethical with expert knowledge (Goodfellow, 2003).

The second theme identified, that aligns with Bronfenbrenner (1974) mesosytem, is that the educators reported that they purposively developed and nurtured relationships between educators and children, between educators and families, and between educators and educators. The ongoing practice of these relationships was highlighted as a key characteristic of each LDC center and why the center was assessed as Exceeding the NQS rating. This aligns with the literature that links positive educator relationships with children (Goodfellow, 2003; Connor et al., 2005; Tayler et al., 2016); solid partnerships between educators and families (Organisation for Economic and Cooperative Development (OECD), 2012); and collaborative staff relationships (Fenech et al., 2021), with high-quality ECEC. These relationships enabled teamwork to be undertaken leading to shared understanding of practices and provision of high-quality ECEC. For teamwork to be successful, the relationships between the educators within each center were important for Exceeding the NQS rating.

Working as a team was deemed to be an essential characteristic for the LDC center to be assessed as Exceeding the NQS rating. Each center identified that they needed to have all educators implementing the center's philosophy and working consistently and have the common goal of provision of high-quality ECEC. The leaders were responsible for pulling the team together and ensuring that addressing conflicting views were discussed and resolved. This finding aligns with the notion that leadership is a collective process with everyone benefiting by exercising power and agency (Siraj and Hallet, 2013). The finding that the LDC center's philosophy is foundational to leadership and teamwork is a concern, as in Australia there is no ongoing provision of leadership support (Gibbs, 2020).

The educators who were in formalized leadership roles were committed to the responsibility of their role, which in turn supported teamwork to occur in the LDC centers. Educators in the LDC centers reported that they took a collaborative approach to leadership as Vivi articulated: “For our center it is everyone being on the same page in a philosophical way.” But this did not mean it was an easy task, as all educators had diverse expertise, experience, and qualifications, as Katie identified “Every single member of our team contributed. But what then happens is that, for example, if you have 15 voices it's like a cacophony.” This aligns with the literature by Delice et al. (2019) highlighting the significance of the leaders' roles to ensure all educators make contributions that are valued and discussed so that the common shared goal is achieved.

The leaders were responsible for not only determining areas that needed to be strengthened, but also to ensure that all educators worked collectively, which ultimately led to everyone benefiting as the LDC centers reached the common goal of Exceeding the NQS rating. Within this macrosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1974), the leaders exercised power and agency (Siraj and Hallet, 2013) and enabled the team of educators to identify similarities and differences, reflect upon them, and enact the provision of high-quality ECEC. Having supportive leadership is foundational for the provision of high-quality ECEC. This finding has implications for ensuring that the educational leaders in ECEC services have the expertise to lead and resolve conflict with teams to work toward common goals. If the staff lack this expertise, it may be difficult to provide high-quality ECEC. Staff may have studied leadership and teamwork in their study for their qualification, or they may need to attend professional learning to ensure they have these skills. Significant investment in staff's professional development is important for providing high-quality ECEC.

While financial investment in high-quality ECEC is not directly explicit in the NQS, however, it was recognized by the educators in the study that if funds are available for professional development, then the LDC center will benefit in the provision of high-quality ECEC. This has implications for ensuring that educators have skills to write grants; to identify areas to strengthen staff knowledge; and to manage funds. This has implications for the management to ensure investment in the staff and LDC center is ongoing to target provision of high-quality ECEC. For-profit LDC center, providers are less likely to achieve an Exceeding the NQS rating (Harrison et al., 2023); then, to offer children learning environments where they thrive, LDC centers' governance and management may need to be provided with incentives to invest in the educators as they are considered to be an important asset of the LDC center.

Supportive governance and management that provided staff with flexible working arrangements, above award work conditions, and above ratio requirements was found to be a significant characteristic of high-quality ECEC in line with literature (Bonetti and Brown, 2018). The directors worked closely with the LDC center management to provide educators with work conditions that would support educators' wellbeing and capacity, as has been identified by Logan et al. (2020). The LDC educators reported that their LDC centers had built financial and staff capacity to achieve an Exceeding the NQS rating. This finding aligns with previous research that not-for-profit, community-based services generally demonstrated higher levels of quality than for-profit services as they were more likely to invest in high-quality ECEC (Cleveland and Krashinsky, 2009; Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2022).

The staff relationships, their teamwork, and the center leadership actions came to the fore in this study in the sixth finding which highlighted that the A&R process needed to be understood by all educators. The macrosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1974) of the external assessment process varied for each center; however, all educators were involved in the A&R process preparation in some way, with the directors and educational leaders guiding educators through the reflection of their practices. The preparation was viewed as an essential investment for the A&R process, which is important for the provision of high-quality ECEC, aligning with the subjective nature of quality ECEC (Dahlberg, 2013), and that the common goal for high-quality ECEC is contextually different. The final theme identified that undertaking the A&R process was holistic occurring over time. Bronfenbrenner's ecological system (1974) shows that systems are dynamic, what he termed the chronosystem. The provision of high-quality ECEC is not an end point in itself but a process of ongoing continual reflection and improvement across all areas of ECEC practice.

This study found that making an investment in educators who are effective communicators, are honest, professional, and passionate, and have knowledge and confidence in one's role is highly recommended for provision of high-quality ECEC in LDC centers. Teamwork and leadership that focusses on common goals within a governance and management structure that supports the educators were identified as being the key requirements for Exceeding the NQS rating.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The views expressed in this study are those of the educators—just one of the key stakeholders in the provision of high-quality ECEC. There were only 15 educators' perspectives reported from five LDC centers as they underwent the A&R process. There was an imbalance of qualifications among the participants, and their views may not be shared by other key stakeholders such as families. The educator is a key decision-maker in determining the practices and outcomes for children's learning and development within a LDC center, and their voices need to be heard as they work within the LDC centers to provide high-quality ECEC. It is recommended that further study be undertaken to provide a broader indication of educators' views.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Sydney Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

This research is from AP's doctoral study. All authors contributed to writing the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA) (2022). NQF snapshots. Available online at: www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/snapshots (accessed December 12, 2022).

Australian Children's Education Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2023). Guide to the National Quality Framework. Available online at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-03/Guide-to-the-NQF-March-2023.pdf (accessed June 20, 2023).

Bennett, J. (2008). Early Childhood Services in the OECD Countries: Review of the Literature and Current Policy in the Early Childhood Field. Paris: United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

Bonetti, S., and Brown, K. (2018). Structural Elements of Quality Early Years Provision: A Review of the Evidence. Education Policy Institute. Available online at: https://epi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Early-years-structural-quality-review_EPI.pdf (accessed February 01, 2023).

Braun, V., and Clark, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Develop. 45, 1–5. doi: 10.2307/1127743

Cleveland, G., and Krashinsky, M. (2005). The Non-Profit Advantage. Toronto Department of Management, University of Toronto at Scarborough, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Cleveland, G., and Krashinsky, M. (2009). The nonprofit advantage: producing quality in thick and thin child care markets. J. Pol. Anal. Manag. 28, 440–462. doi: 10.1002/pam.20440

Colmer, K., Waniganayake, M., and Field, L. (2015). Implementing curriculum reform: insights into how Australian early childhood directors view professional development and learning. Profess. Develop. Edu. 41, 203–221. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.986815

Connor, C., Son, S. H., Hindman, A., and Morrison, F. (2005). Teacher qualifications, classroom practices, family characteristics and preschool experience: complex effects on first graders' vocabulary and early reading outcomes. J. School Psychol. 43, 343–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.06.001

Council of Australian Governments (COAG) (2008). National partnership agreement on early childhood education. Available online at: http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1314/QG/ChildhoodEducatAccess (accessed June 04, 2021).

Dahlberg Moss, and Pence. (2013). Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: Postmodern Perspectives (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Falmer. doi: 10.4324/9780203371114

Delice, F., Rousseau, M., and Feitosa, J. (2019). Advancing teams research: what, when, and how to measure team dynamics over time. Front. Psychol. 10, 1234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01324

Department of Education Employment Workplace Relations. (2009). Early Years Learning Framework. Belonging, Being and Becoming. Available online at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-02/belonging_being_and_becoming_the_early_years_learning_framework_for_australia.pdf (accessed November 03, 2020).

Fenech, M., Giugni, M., and Bown, K. (2012). A critical analysis of the National Quality Framework: Mobilising for a vision for children beyond minimum standards. Aust. J. Early Child. 37, 5–14.

Fenech, M., Wong, S., Boyd, W., Gibson, M., Watt, H., Richardson, P., et al. (2021). Attracting, retaining and sustaining early childhood teachers: an ecological conceptualisation of workforce issues and future research directions. Au. Edu. Res. 3, 6. doi: 10.1007./s13384-020-00424-6

Gibbs, L. (2020). Leadership emergence and development: organizations shaping leading in early childhood education. Edu. Manag. Admin. Leadership 50, 672–693. doi: 10.1177/1741143220940324

Goodfellow, J. (2003). Practical Wisdom in Professional Practice: the person in the process. Contemp. Iss. Early Childhood 4, 48–63. doi: 10.2304/ciec.2003.4.1.6

Gumus, G., Bellibas, M., Esen, M., and Gumus, E. (2016). A Systematic Review of Studies on Leadership Models in Educational Research from 1980–2014. London: Sage Publications. doi: 10.1177/1741143216659296

Harrison, L., Waniganayake, M., Brown, J., Andrews, R., Ki, H., Hadley, F., et al. (2023). Structures and systems influencing quality improvement in Australian early childhood education and care center. Au. Edu. Res. 3, 8. doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00602-8

Haslip, M., and Donaldson, L. (2021). How early childhood educators resolve workplace challenges using character strengths and model character for children in the process. Early Childhood Edu. J. 49, 337–348. doi: 10.1007/s10643-020-01072-2

Heckman, J. J. (2013). Investing in Disadvantaged Young Children is an Economically Efficient Policy. Paper presented at the Iowa Business Council: Early Childhood Summit, Iowa.

Irvine, S., Thorpe, K., McDonald, P., Lunn, J., and Sumsion, J. (2016). Money, Love and Identity: Initial findings from the National ECEC Workforce Study. Summary report from the national ECEC Workforce Development Policy Workshop. Brisbane, Queensland: QUT ISBN - 978-1-925553-00-0

Ishmine, K., Tayler, C., and Thorpe, K. (2009). Accounting for quality in Australian childcare: A dilemma for policymakers. J. Educ. Policy 24, 717–732.

Logan, H., Cumming, T., and Wong, S. (2020). Sustaining the work-related wellbeing of early childhood educators: perspectives from key stakeholders in early childhood organisations. Int. J. Early Childhood 52, 95–113. doi: 10.1007/s13158-020-00264-6

Manning, M., Wong, G., Fleming, C., and Garvis, S. (2019). Is teacher qualification associated with the quality of the early childhood education and care environment? Rev. Edu. Res. 89, 370–415. doi: 10.3102/0034654319837540

McMahon, S. (2017). “Leadership in ECEC” in Work-Based Practice in the Early Years, eds S. McMahon, and M. Dyer (Taylor and Francis Group). doi: 10.4324/9781315561806-10

Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Ariescu, A., Penderi, E., Rentzou, K., et al (2015). CARE Curriculum Quality Analysis and Impact Review of European Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) D4, 1. A Review of Research on the Effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) upon Child Development. Available online at: http://ecec-care.org/fileadmin/careproject/Publications/reports/new_version_CARE_WP4_D4_1_Review_on_the_effects_of_ECEC.pdf (accessed October 01, 2020).

NSW Legislation (2023). Education and care services National regulations. Available online at: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/sl-2011-0653#ch.4-pt.4,~4.-div.5 (accessed February 01, 2023).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2006). Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care Policy. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic and Cooperative Development (OECD) (2012). Starting Strong II: A quality Toolbox for Early Childhood Education and Care. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic and Cooperative Development (OECD) (2019). Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/f8d7880d-en

Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD) (2018). Starting Strong: Engaging Young Children - Lessons From Research About Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care. OECD. Available online at: https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Starting_Strong_Engaging_Young_Children.html?id=oDVTDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed August 30, 2019).

Organisation for Economic Cooperative Development (OECD) (2017). Starting Strong V: Transitions from Early Childhood Education and Care to Primary Education. Available online at: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org.ezproxy.scu.edu.au/education/starting-strong-v_9789264276253-en (accessed October 08, 2020).

Pascoe, S., and Brennan, D. (2017). Lifting our game: A report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools through early childhood intervention. Available online at: https://education.nsw.gov.au/early-childhood-education/whats-happening-in-the-early-childhood-education-sector/lifting-our-game-report/Lifting-Our-Game-Final-Report.pdf (accessed October 08, 2020).

Phillips, A. (2020). An Investigation of Long Day Care Services in Australia That Are Exceeding the National Quality Standard. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Pianta, R., Downer, J., and Hamre, B. (2016). Quality in early education classrooms: definitions, gaps, and systems. Fut. Child. 26, 119–137. doi: 10.1353/foc.2016.0015

Siraj-Blatchford, I., and Manni, L. (2006). Effective Leadership IN THE Early Years Sector: The ELEYS Study. London: Institute of Education, University of London.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj, I., and Taggart, B. (2014). Students Educational and Developmental Outcomes at Age 16: Effective Pre-School, Primary and Secondary Education (EPPSE 3–16) (London). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/351496/RR354_-_Students__educational_and_developmental_outcomes_at_age_16.pdf (accessed October 08, 2020).

Tayler, C. (2012). Learning in Australian early childhood education and care settings: changing professional practice. Education 40, 7–18. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2012.635046

Tayler, C., Cloney, D., Adams, R., Ishimine, K. Thorpe., and Nguyen, C. (2016). The E4Kids study: Assessing the effectiveness of Australian early childhood education and care programs. Available online at: https://education.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2929452/E4Kids-Report-3,0._WEB.pdf (accessed August 04, 2020).

The Front Project (2019). A smart investment for a smarter Australia: Economic analysis of universal early childhood education in the year before school in Australia. Available online at: http://www.thefrontproject.org.au/initiatives/economic-analysis (accessed January 22, 2023).

Urban, M., Vandenbroeck, M., Lazzari, A., Van Laere, K., and Peeters, J. (2012). Competence requirements in early childhood education and care. Available online at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED534599.pdf (accessed October 08, 2022).

Warren, D., and Haisken-DeNew, J. P. (2013). Early bird catches the worm: The causal impact of pre-school participation and teacher qualifications on year 3 national NAPLAN cognitive tests. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2344071 (accessed June 06, 2020).

Keywords: high quality early childhood education and care, educators' qualities, professional development, assessment and rating, national quality framework

Citation: Phillips A and Boyd W (2023) Characteristics of high-quality early childhood education and care: a study from Australia. Front. Educ. 8:1155095. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1155095

Received: 31 January 2023; Accepted: 07 June 2023;

Published: 06 July 2023.

Edited by:

Linda Joan Harrison, Macquarie University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jane Page, The University of Melbourne, AustraliaEliana Bhering, Fundação Carlos Chagas, Brazil

Louise Tracey, University of York, United Kingdom