- 1Department of Special Education, MA in Special Education, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of Special Education, Faculty of Education, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

The purpose of this research was to better understand the challenges, as well as ways to overcome the aforementioned challenges, associated with sex and reproductive health education for parents of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from the perspective of parents. A qualitative multiple case study approach, including interviews and document analysis, was conducted to answer the research questions. The participants included 9 parents of adolescents with ASD, including (4) fathers and (5) mothers. Their children’s ages ranged from (13–19) years. Inductive coding was conducted to analyze the data collected. The findings suggested several challenges exist, including parents’ lack of knowledge regarding sex and reproductive health education and training on how to effectively teach their children. This lack of knowledge may contribute to unacceptable social demonstrations of sexuality by individuals with ASD, which creates another challenge for parents. The findings related to the second research question indicated families of individuals with ASD need more awareness and education, particularly on how to effectively educate their children on sexual matters. The importance of education regarding sexual matters for individuals with ASD within the school and community was also realized. The findings could help the Ministry of Education establish educational programs to ensure schools are equipped to educate individuals with ASD on sexual matters. The programs could also be beneficial if they provided training to parents on how to effectively provide sexual education to their adolescent children. The findings of this research could additionally provide insight to parents, general education teachers, and special education teachers on the importance of sex and reproductive health education for children with ASD.

Introduction

Sex is considered one of the fundamental biological issues and is significantly correlated with psychological and physiological traits and differences at various life stages. Male and female are often the dichotomous variables used to categorize gender, although gender is not completely binary, but sometimes is categorized several different ways including, physical features from birth, self-identification, legal gender, and social gender in terms of behaviors and sexual expression (Lindqvist et al., 2020). However, there is a definite difference between the biological traits for the different genders and the ways in which those traits are expressed (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2020).

Adolescence and puberty are two of the most significant transitional phases in one’s life. Rapid growth and development in all areas, including physical, sexual, psychological, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral growth, are characteristics of this stage (Ballan and Freyer, 2017). This level of life is one of the most difficult and delicate, due to the difficulties and obstacles that accompany it as a result of the numerous changes that the person experiences (Sisk and Gee, 2022).

Sexual education is imperative during this time, as some adolescents do not understand the changes occurring in their body during this period of change (Wang, 2022). The primary goal of sexual education is to facilitate the transition from childhood to puberty and adolescence. It also focuses on all causes, developments, and changes related to sexual health (Wang, 2022). Relationships, interpersonal abilities, gender, sexual and psychological health, society, and culture are also included (Planned Parenthood, 2021).

It is also imperative individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) receive sexual. Education. Symptoms of ASD typically manifest in childhood (Zamora et al., 2019; Othman et al., 2020). The majority of these individuals encounter numerous difficulties and setbacks throughout their lives. They often experience particular difficulties in adolescence, due to the circumstances and the potential for change in every area of growth (Ismiarti et al., 2019).

Some people incorrectly assume individuals with ASD are uninterested in relationships and sexual activity (Holmes et al., 2021; Weir et al., 2021). However, the results of the Sala et al. (2020) study indicated most adolescents with ASD tend to be interested in relationships and sexual activity and also have psychosexual characteristics and needs. They also show physical changes as a result of puberty, in addition to fluctuations and psychological changes, and an increase in the level of sexual instincts and motives (Muslikhah and Rudiyati, 2019).

Need for education

Teenagers with ASD condition may find themselves drawn to same-sex, bisexual, or heterosexual individuals and may experience more stress during their sexual development (George and Stokes, 2017; Weir et al., 2021). Due to obstacles with the process of communication and social interaction, one of the biggest challenges they encounter is their inability to express and understand their sexual feelings toward others and themselves. This inability to express themselves can have a negative impact on the development of sexual relationships (Stanojević et al., 2021; Teliti and Resulaj, 2022). The results of the Turner et al. (2017) study showed that inappropriate sexual behavior is more common in adolescence and adulthood for people with ASD, as they show sexual interests and behaviors in public, and this is what makes the behavior inappropriate and problematic. Research has suggested this is closely related to a limited level of sexual knowledge (Turner et al., 2017).

Among the common sexual practices practiced by adolescents with ASD are nudity, masturbating in front of others, touching their own and others’ genitals, looking at certain parts of the body of others, kissing others, and undressing in public (Pryde and Jahoda, 2018). These practices lead to a lack of acceptance by others (Ismiarti et al., 2019; Mann and Traver, 2019). Masturbation is one of the most common behaviors among adolescents with ASD, because it leads to their feeling of sexual satisfaction compared to other behaviors (Muslikhah and Rudiyati, 2019). Some mothers expressed the need to educate children with ASD on sexual actions that should be done in private (Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022). Society rejects any inappropriate behavior that does not conform to cultural standards, which raises fear and anxiety for adolescents themselves and their guardians (Masoudi et al., 2021).

Without enough preparation, teenagers with ASD will feel confused and anxious as these changes occur in adolescence. This is true for all adolescent children, not only adolescents with ASD. However, neurological differences in adolescents with autism can impact these children’s development and the ways they explore their sexuality (Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022).

Role of parents

Parents are the foundation for preparing children with ASD to face these changes and developments (Pryde and Jahoda, 2018; Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022). Therefore, it is crucial for parents of teenagers with ASD to understand the significance of puberty and be knowledgeable of the changes that occur in their child’s sexual development, as well as the difficulties and sexual challenges that may ensue (Chamidah and Jannah, 2017). Parents should learn effective methods and strategies to teach adolescents the concept of sexual functions. This could help reduce the emergence of inappropriate sexual behaviors (Masoudi et al., 2021).

Most parents of adolescents with ASD believe that sexuality begins when they reach adolescence, although it begins in early childhood (Chamidah and Jannah, 2017). Research has indicated parents tend to discuss topics related to sex within a very limited and restrictive framework, such as personal hygiene and the privacy of their own places only (Gkogkos et al., 2019; André et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2021). Also, this matter is sometimes opposed by parents, and perhaps this imposition is justified by some of the negative beliefs and ideas that are held by society. Some believe talking about sex leads to the emergence of sexual behaviors that did not exist previously, or that it enhances their attention, increases motivation and curiosity about matters related to sex, and may lead to experimentation (Pryde and Jahoda, 2018).

Research has suggested parents are exposed to psychological stress and anxiety because of their constant fear for their children (Mackin et al., 2016; Lestari and Aunurrahman., 2021). They are fearful they may be exposed to sexual exploitation and harassment, or abuse from others, due to their lack of sex education. The challenges faced by parents may lead them to suffer very negative psychological and health consequences, such as exposure to pressure, anxiety, stress and fear on a permanent basis (Masoudi et al., 2021).

Parents are the basis for preparing their children with ASD to face these changes and developments that occur in adolescence, and without good preparation, adolescents with ASD will feel confused and stressed during this period of their life (Pryde and Jahoda, 2018). In this sense, it is important for parents of adolescents with ASD to understand the importance of knowledge regarding the developments and changes that occur in their adolescent child’s sexual development and the resulting difficulties and challenges that exist (Chamidah and Jannah, 2017).

Sex and reproductive health education is one of the most difficult topics that parents of teens with ASD have to teach their children, because they do not have sufficient information and knowledge regarding matters related to sexual development (André et al., 2020; Gergelya and Rusu, 2021). Parents may realize the importance of sex education, but face difficulties and challenges that lie in not knowing how to teach their children or the appropriate method to use (Chamidah and Jannah, 2017). The failure by parents to use effective methods and strategies for adolescents on the concept of their sexuality could generate the emergence of many inappropriate sexual behaviors in the society in which they live (Masoudi et al., 2021). Therefore, it is imperative sexual education is offered, so parents are knowledgeable of their role and how to best educate their children (Alomair et al., 2021).

Role of schools

While the importance of sex and reproductive health education is important everywhere, worldwide, it is especially true in Saudi Arabia as sex and reproductive health education is not included in the formal curriculum (Horanieh et al., 2020a,b). Likewise, there is a lack of evidence-based sex and reproductive health education curricula geared towards the needs of adolescents with ASD (Stanojević et al., 2021). The curriculum, rather, is restrictive, consisting of a specific structure, related to core subjects, such as biology, and Islamic studies (Saudi Arabia Ministry of Education, 2019). Cultural, social and religious beliefs in Saudi Arabia make sex education a difficult topic, as Saudi differs from Western societies with extremely conservative views on sexuality, primarily driven by Islamic values (Al-subaie, 2019; Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022).

Chamidah and Jannah (2017) substantiated these findings regarding schools’ absence of sex education for children entering adolescence in a study conducted in Indonesia, indicating there are multiple locations around the globe dismissing the need for this type of education. This lack of knowledge has led to children obtaining sexual information from other sources, which are likely to be less credible, such as the media, Internet, pornography, films and television. This can result in unsatisfactory behavioral consequences regarding sexual arousal and desire and lead to children learning the wrong sexual behaviors (Solomon et al., 2019).

Saudi Arabia

It is also worth noting the culture in Saudi Arabia has conservative views on sexuality (Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022). Pre-marital and sexual relations outside the context of marriage are forbidden, so discussions around these topics outside of marriage are also often discouraged (Attaky et al., 2021). Literature on sexuality is also very limited. Research that does exist states sexual satisfaction is an important goal within dyadic relationships (Attaky et al., 2021). In the Islam culture, sex is supposed to be reserved for marriage. However, sexual satisfaction is an important goal within the confines of marriage for Arabian couples. Outside of marriage, however, it is taboo to even discuss sexual activity. Therefore, some mothers in Saudi Arabia expressed their hesitation with educating their children on such topics (Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022). Despite these challenges, it is important that parents, as well as special education teachers, or specialists within schools ensure adolescents in Saudi Arabia are properly educated on this topic.

Research questions

This study sought to evaluate the challenges of sex and reproductive health education for adolescents with ASD in Saudi Arabia and to fill the gap in previous literature by focusing on family’s perspective. This study also sought to discover suggestions for overcoming the challenges parents of adolescents with ASD face related to sex education. Therefore, the following research questions are developed:

1. From the parental perspective, what are the challenges in the provision of sex education in adolescents with ASD?

2. What are ways for parents of adolescents with ASD to overcome identified challenges in the provision of sex education?

Method

This study used a qualitative multiple case study approach for collecting data through interaction and direct involvement with parents of adolescents with ASD. Qualitative research, according to Creswell (2014), is “an approach for exploring and understanding the meaning individuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem” (p. 32). Qualitative research involves collecting data in participants’ natural setting. An inductive approach is then utilized to analyze the data and establish themes from specific information to draw more general conclusions. This methodology was selected, as it is one of the most comprehensive approaches that achieves a deep understanding of all the details (Crowe et al., 2011), such as providing an accurate description of all the issues facing parents of adolescents with ASD in relation to sex education, while also revealing their views and experiences regarding the challenges and obstacles that occur. In addition, this technique addresses solutions and proposals that contribute to ideas for improvement, according to one’s own experiences, in order to achieve the best possible results.

Instrument development

The researchers developed interviews, which is a semi-structured way to collect data. The interviews were conducted using a set of open questions, in order to enhance the discussion and to obtain accurate and detailed data. An experimental interview was conducted, and the main objective was to ensure the questions were clear. They were rephrased and developed, if necessary. The approximate amount of time the interview would take to complete was also estimated. Additionally, the researchers ensured the questions flowed in a sequential manner, for ease of use with the participants. A pilot study is beneficial in qualitative research, as it enables the researcher to refine, revise, develop data collection tools, and take advantage of proposals presented (Yin, 2014; Creswell and Poth, 2018).

The study and interview questions were divided into two parts. The first part included the first study question, which inquired about the challenges of sex education for adolescents with ASD from the point of view of their parents. This included a set of six open-ended sub questions, which sought to answer the first aforementioned research question. The second question inquired about improvement proposals to reduce the challenges of sex education for adolescents with ASD. The second part included interview questions that were built through the study’s second research question, which included two open-ended sub questions. Therefore, in total there were eight questions, six in the first part, which facilitated answering the first research question and two in the second part, which helped with answering the second research question.

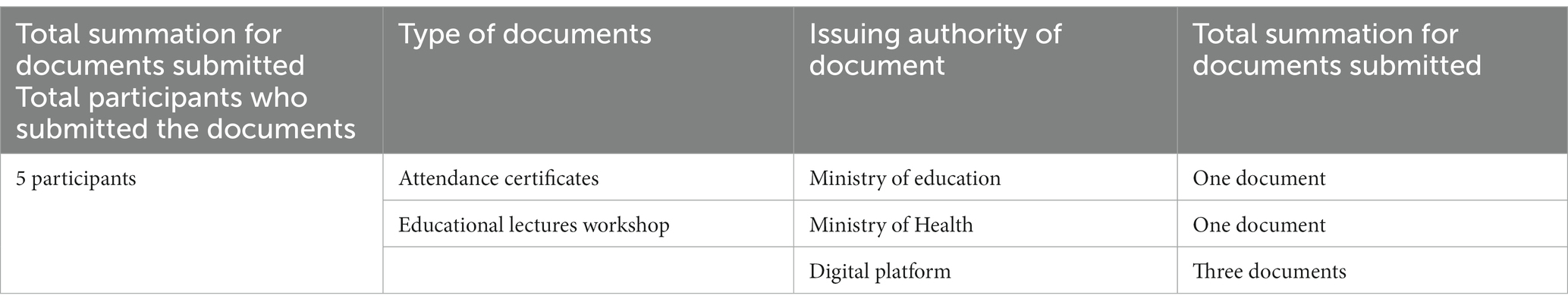

In addition to the interviews, document analysis was used as a tool that provided additional data that did not appear in the interviews. Participants were asked to provide documents related to their attendance at courses or lectures in the field of sex education. Some of the participants submitted the required documents, except four of them, who were unable to do so because they did not have them. Then all the obtained documents were analyzed. These documents varied, and included certificates participants received from attending educational lectures and training courses related to sex and reproductive health education and puberty for individuals with ASD. The data had become sufficient and clear. The details are included in the Table 1. Another interview was also conducted for more confirmation and assurance, as Creswell and Poth (2018) recommended. Additionally, the researchers continued to undergo field visits to collect data until he reached the degree of saturation for all categories, and no new data appeared (Saunders et al., 2018).

Participants

A number of parents of adolescents with ASD who were present in public schools and day care centers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were selected in the city of Makkah, and they were chosen according to the intentional method. This method was utilized, because it helped with finding participants with the specified criteria (Lauretto et al., 2012). The main criteria included being the parent of a son with ASD, who had reached adolescence, and a letter of participation request was used for attracting participants. Additional criteria suggested knowledge in sexual matters related to adolescence, such as receiving prior education or training, even if it was obtained independently or informally from friends or social media. Because there is not often formal sexual training in Saudi Arabia, former background included parents obtaining information from the internet, which is one of the primary sources of sexual education in Saudi Arabia (Alomair et al., 2021). However, this was not a requirement, because the researchers wanted a range of previous training from the participants. The final criteria included being from the city of Makkah.

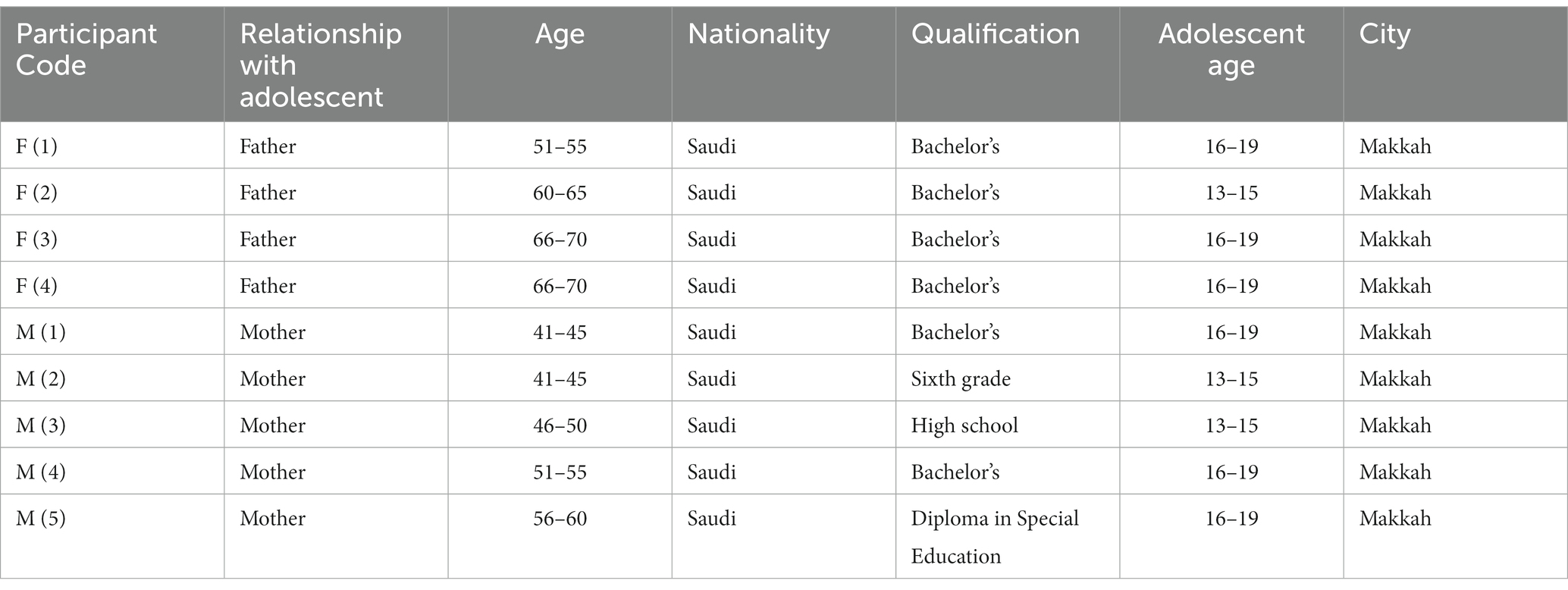

The number of participants in the study was (9) parents of adolescents with ASD, including (4) fathers and (5) mothers. Their children’s ages ranged from (13–19) years. The adolescents with ASD were males. This is because there were more male students with ASD, which aligns with previous findings by Duvekot et al. (2017) which found a 2.6 to 1 ratio of males to females diagnosed with ASD. The sample size of 9 students enabled the researchers to obtain more detailed, reliable and accurate data. To preserve the privacy of the participants, they were not be called by their real names in the study, but rather these names were encoded (Table 2).

Data analysis

The inductive method was used to analyze the subjects and the data from the personal interviews (Thomas, 2006). This method depends on the organization and sequence and on the development of data with compatible and different denominators within the main topics that answered the basic questions of the study. This approach was utilized because it enabled the researchers to generate overarching findings from the raw data, which was collected (Thomas, 2006). The interviews were done in Arabic. They were then recorded and transcribed in Arabic to allow for thematic analysis. The data was analyzed in Arabic. Three coders, two who had doctorate degrees and one who had a Masters degree in special education, helped with the coding process. Follow-up data analysis was based on seven main steps for analyzing the topics mentioned by Al-Abd Al-Karim (2020), which included organizing the data, where all the data was dumped on the computer via the Word program. Each participant had his own file, and all the texts were read and reviewed. Additionally, the recordings were listened to over again, with a focus on identifying all the important points. This enabled the researchers to go deeper into the available data to ensure all data was written and free of errors and that the data had become familiar and clear. The coding process then began, which was one of the most important steps that depended on the use of objective analysis, where notes were placed on all important texts manually, and were then coded with simple words or phrases, after which many topics of important data were extracted (Lester et al., 2020).

The notes were recorded by reviewing all subjects in depth again. The goal was to have points and topics revealed that did not appear clearly in the initial coding and in extracting the topics. After the completion of the previous step, patterns were identified, and the related phrases were linked to each other in one group, then the phrases that were similar in terms of agreement and disagreement were extracted and placed among the main topics. After that, the results were formulated, and in this step, the data was written, formulated, analyzed, and interpreted sequentially to discover the participants views on the subject of the study. The results were verified, as all the main and sub-topics and phrases that were coded in each of the main topics were reviewed and then discussed. The three coders kept working until they reached agreement on all of the codes. The coded data was then translated to English. The main and sub-topics and phrases were then developed in English. The two versions of codes (Arabic and English) were then compared by the professionals to ensure the translated codes were accurate. This translation process allows for research transparency and helps ensure meaning is not lost in translation (Ho et al., 2019). Intercoder reliability was established to help with the reliability of the findings. Finally, the final report was written, and this was the last step to explain all the detail of the study.

Results

This study included (9) parents of adolescents with ASD, including (4) fathers and (5) mothers. The average age of the participants in the study was (50) years, ranging from 40 to 68 years. Most of the participants had received undergraduate diplomas (Bachelor’s degree). The participants’ children were adolescents with ASD, between the ages of 13–19 years old. The results of the current study were divided into two main parts, including a section regarding the most important challenges of sex education facing parents of adolescents with ASD and a section discussing the most important needs and suggestions that may contribute to reducing these challenges. The participants’ responses to the first question generated (2) main themes, including challenges related to the concept of sexual education and challenges related to inappropriate public behaviors. As for the second question of the study, the responses also developed (3) main themes for this question, including family awareness and education, the importance of education within the school, and community participation.

Challenges related to the concept of sex education

To answer the question related to the challenges facing parents of students with ASD, the first theme that emerged was challenges related to the concept of sex education. The lack of sufficient information and expertise on the concept of sex education constitutes a major challenge in this aspect and participants’ responses indicated there was a discrepancy in parents’ knowledge and information about sex education, as some of the parents did not have any knowledge regarding sex education. Father number two stated, “This is the first time I have heard about sex education.” On the other hand, these participants expressed their personal interpretation of the term sex education through information available to them. The parents expressed their knowledge was limited to several primary areas, including personal hygiene, protection from sexual assault, and the ability to marry and establish private relationships. The second and third father both stated that sex education meant discussing personal hygiene, marital life, and how to deal with sexual harassment.

Parents expressed they did not feel equipped with knowledge of appropriate methods to educate their children on sexual matters. This was evident by M (3)’s comment expressing she did not know how to control her son’s sexual behavior, as he stated “there are ongoing sexual behaviors, and I do not know how to deal with them or the right way to deal with them.” Another parent expressed verbal indoctrination was their only educational method, as F (2) stated, “we did not use any educational method, because I do not know, but verbally, at least it is wrong and defective.” M (1) also stated “I used direct communication with him. At least, do not do this, because it is wrong and forbidden.”

Conversely several parents stated they had received sexual education training. Document analysis substantiated this finding, as the documents of F (1), M (3), M (4), and M (5) showed that they received educational lectures related to sex and reproductive health education for people with ASD, and that they underwent training courses on puberty and adolescence. However, despite this training, some parents still did not feel properly equipped to educate their children, as M (3) had previously expressed how she did not know how to control her son’s behaviors regarding sexuality. This implies more training is needed.

Some participants indicated that they did not want to teach their children about sexual matters, due to their negative attitudes and ideas toward sex education. For example, parents expressed their concern about new sexual problems arising, due to sex education. The first and fourth father stated they did not educate their children with ASD, because they felt bringing sexual matters to their children’s attention might cause their children to explore their sexuality, leading to unwanted sexual behaviors.

Conversely, some participants expressed the importance of education at this stage. F (3) stated he found sex education to be very important, especially during adolescence. He felt sex education helped children with personal hygiene and encouraged purity, limiting their sexual exploitation and the emergence of non-consensual sexual behaviors. He stated, “sexual education is very important. I support this being done in schools. It is a stage that everyone goes through regardless of disability.” Mother number five agreed stating, “they must be taught that there are parts of the body that no one should touch, as well as personal hygiene and many matters related to sexual behaviors that people with ASD must learn.” Parents also face challenges in teaching their children the skill of personal care and hygiene, and some of the participants explained the difficulties they face with their children regarding care and personal hygiene during puberty and adolescence. For example, M (4) stated, “as for personal care, I do it, come on, because he does not depend on himself a lot.”

Challenges related to inappropriate public behaviors

Parents also expressed their concerns regarding challenges related to inappropriate public behaviors. Parents of adolescents with ASD may be exposed, at this critical stage, to challenges regarding sexual behaviors, which are unacceptable in society. For example, F (2) stated, “he masturbates a lot, and more than once I saw him.” M (5) also expressed her concern, stating “my son used to masturbate in front of a maid, so that he felt as if he had worked with her.” F (3) faced a challenge with his teenage son, represented by him watching pornographic clips: “I saw him watching a clip on YouTube that was about sexual matters. Frankly, I was shocked and immediately pulled the phone from his hand and locked it permanently from him.”

Family awareness and education

The next question sought to answer proposals to overcome the aforementioned challenges. The first theme that emerged was related to family awareness and education. Parents and family members’ acceptance of adolescents with ASD is one of the most important basic elements, and the responsibility rests primarily on family members in providing information related to sexual matters. This was confirmed by the participants’ answers. For example, F (5) stated “I see that they are important. The family is aware of sexual matters and all the ways they use them.” F (3) stated, “at home it is important that the family be aware of this issue, and be a united hand, and all of them must know the methods that suit the needs and abilities of the autistic group, especially the teenage stage.” If parents are not educating their children, it is apparent adolescents will receive the information from other sources, as evident by F (3)’s statement about his son watching pornographic clips about sexual matters.

Some parents even realized the importance of taking the initiative to receive training to ensure they were properly equipped to educate their children with ASD on sexual matters. F (1), M (3), M (4), and M (5) all expressed they had received educational lectures related to sex and reproductive health education for people with ASD, and they underwent training courses on puberty and adolescence. This helped them to be prepared, while developing the knowledge and skills they needed to teach their children.

Activating the role of the school

This was the next theme that was generated from participants’ responses to the second research question. The design and teaching of sexual education curricula in schools is considered one of the main pillars to overcoming challenges associated with adolescents with ASD regarding sexuality. Some of the participants in the current study suggested that educational curricula on sexual education should be prepared for adolescents with ASD, as well as their parents. This is evident through the following quotes: M (4) “Design a special curriculum. Sex education, like any other course, should be taught. F (4) stated, “In Saudi Arabia, it would be very nice if special curricula were created on sexual education for parents and adolescents, but unfortunately we lack this subject.” M (3) reported that government schools and day-care centers in the city of Makkah Al-Mukarramah lack curricula and scientific material: “Schools and centers are few, and even the lack of scientific material, although I tried and searched and searched for a model, for example, how to teach her to clean herself, or even if there are models, but unfortunately I found none of these things.”

When responding to potential solutions to challenges regarding sexual matters for adolescents with ASD, M (4) replied, “to provide sex and reproductive health education programs in the three academic stages.” The education should vary according to children’s age and stage, or grade, in school. The mother went on to explain when children are in the primary stage, pictures could be used to explain body parts which are forbidden to be touched by anyone. They can later be taught about sexuality, relationships, and marriage. These responses substantiate the need for effective school sexual education programs for adolescents with ASD.

The role of teaching adolescents with ASD sex and reproductive health education is not only the responsibility of parents and general educators, but also includes the involvement of special education teachers, or specialists. Therefore, special education teachers must be aware of the stages of adolescent development and all areas of sex and reproductive health education and how to use effective educational methods. For this reason, M (3) expressed the importance of schools hiring special education teachers, as general teachers may not be knowledgeable regarding ASD and about effective teaching methods for these students. She stated, “they are supposed to hire special education specialists in integration schools. She is the one who gives them the idea, because they know how to deal with them more than anyone else.” M (4) reported that special education teachers must go to schools and hold educational courses for general education teachers: “The specialists go to schools and educate general education teachers so that they know about all the sexual issues that they may encounter with autism and how to behave with them in this respect.”

Community participation

Among the most prominent agencies that provide community services are mental health clinics, striving to provide solutions to community members regarding problems they are facing. Parents expressed the need for these services, because of the pressure they face raising children with ASD. M (5) stated, “there should be individual and group psychological sessions for mothers, and they should talk about sexual matters.”

The task of specialists is not limited to teaching and educating adolescents with ASD and their parents, but rather their role extends to include the whole community. Therefore, it is necessary to provide education and awareness of all the transitional stages that they go through, in addition to expanding the publication of topics related to the field of sexual education. The development of technology and the use of distance education systems makes educating parents and adolescents with ASD and society about the physical and psychological changes that occur to adolescents and the subsequent behaviors, or sexual changes, more viable. F (3) substantiated this stating, “it is necessary for specialists to do this subject through, for example, lectures, brochures through social media. It is possible to do more remote lectures for the puberty and adolescence period.”

Discussion

The results of the current study indicated that there is a difference in the opinions of parents of adolescents with ASD in their concept of the term sex education, protection from sexual exposure, and marriage. This result is consistent with the study by Holmes et al. (2019) which indicated information about sex education is presented within a limited framework. This finding also aligned with findings by Chamidah and Jannah (2017), which found some parents of adolescents with ASD were knowledgeable regarding sexual development, growth, and sex education.

Additionally, there were differences in the training parents stated they received. Specifically, three females and one male stated they received training. It is worth noting the age discrepancy between the mothers and the fathers in this research. The fathers ages ranged from 51–70 years of age, while the mothers ages ranged from 41–60. Research has indicated parents are getting married later in Saudi Arabia than they previously did, due to education and career aspirations (El-Haddad, 2003; Al-Khraif et al., 2015). The age discrepancy could be the reason less fathers reported receiving training on sexual matters for teenagers with ASD, as there is not much formal training available, and most training comes from the internet (Alomair et al., 2021). Older parents may be less likely to utilize the internet (Fierloos et al., 2021). However, more research is needed to confirm this. The reason mothers had received more training could also be because mothers in Saudi Arabia tend to be me more involved in parenting, as the role of parenting is highly gendered (Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022).

The findings of this research also suggested some parents do not want their children to receive sexual education, as they believed it may draw their children’s attention to undesirable sexual matters and generate the emergence of socially unacceptable sexual behaviors. The Pryde and Jahoda (2018) study agreed in terms of the fear of mothers of adolescents with ASD. Their finding similarly indicated mothers irrationally fear sex education may create the development of sexual behaviors that did not previously exist and may increase sexual desires (Pryde and Jahoda, 2018). Daghustani and MacKenzie (2022) also found mothers had varied responses from teaching their children about sexuality and privacy regarding sexual acts to avoidance to try to succumb their desires. This confusion and these varied approaches illustrate why training and awareness is warranted to clear up these misconceptions and to help parents realize the importance of training and education.

This research also shed light on the challenges parents of teenagers with ASD face regarding teaching their teenage children the skill of personal hygiene and taking care of private places. Parents expressed how they did not feel they could effectively teach their children these skills. André et al.’s (2020) research substantiated this finding, indicating the challenges associated with teaching students, especially adolescents, the skill of personal hygiene. It is clear training and information need to be made available to these parents. A network where parents could communicate their successes and challenges would also be helpful, so these parents do not feel like they are alone in their attempts to teach their children.

The results of the study also indicated the most common sexual behavior among adolescents with ASD is masturbation. Pryde and Jahoda (2018) also found adolescents with ASD masturbate in public. The results of the study showed that parents do not have sufficient knowledge about methods to ensure children’s sexual behavior is done in appropriate settings and effective ways to educate them on matters related to sexual education. Some parents’ strategies were limited to verbal indoctrination in this study, and research by Holmes et al. (2019) confirmed that the most highly utilized method for teaching sexual education was the verbal indoctrination method. Both Chamidah and Jannah (2017), as well as Rooks-Ellis et al. (2020) studies agreed that parents were not knowledgeable of effective teaching styles and ways to help their children in these respects. This furthermore substantiates the need for training, information, and collaboration between parents, so they have information and a network of other parents to share their experiences. Daghustani and MacKenzie (2022) also expressed the need for support educationally, within families, and socially for parents raising children with ASD and navigating how to best educate them regarding sexual matters.

Conversely, some parents realized the importance of sex education for their teenage children. Additionally, some parents recognized the need for parental knowledge and awareness of the physiological changes that occur for adolescents and the need to effectively teach adolescents with ASD about these natural changes. This finding aligns with research by André et al. (2020), as parents desired to obtain additional information on topics of sexual education. It also aligns with the study of Gergelya and Rusu (2021), where parents realized the importance of sex education for their adolescent children with ASD in all stages of their lives. Similarly, Chamidah and Jannah (2017) found that sex and reproductive health educations should be provided to their adolescent children with ASD, because this type of education is one of the basic foundations in the education process. Therefore, it is evident children also need to receive relevant education.

The results of this study confirmed schools do not adequately provide sex and reproductive health education to students with ASD, or equip their parents to provide the necessary education. Sex education specific to students with ASD is not included in the curricula, according to parents in this study. Among the most prominent proposals put forward to overcome the challenges of sex education is the design of special curricula for sex and reproductive health education prepared by specialists. Results of research by Pugliese et al. (2019) found including age-appropriate sex and reproductive health education in school curricula for parents with ASD had positive results in terms of increased knowledge. Similar results were found when parents were given access to sex and reproductive health education materials for their children by the schools. Plexousakis et al. (2020) had similar findings, noting sex education helps children express their feelings, establish healthy social and private relationships, and increase awareness of one’s body. It is evident curriculum needs to be updated to include sex education for all students, specifically those students with ASD.

It was also proposed to activate the role of mental health clinics for parents, as they work to help parents find solutions, in addition to reducing the burden and pressures they go through. Among the proposals is also the provision of awareness and educational lectures by specialists on the concept of sex education, to include society as a whole. The study of Chamidah and Jannah (2017) agreed that holding lectures and training seminars contributes to greater awareness and understanding related to sex education.

This study was unique and warranted, as it included both mothers and fathers. There is not much research on this topic, and the research that does exist mostly includes mothers’ perspectives (Daghustani and MacKenzie, 2022). This research offered varied perspectives, which is very important to include, especially in a culture like Saudi Arabia where cultural gender differences exist.

Limitations

One of the most important difficulties that we faced when preparing the current study was during the collection of data, as it was difficult to find willing participants. This was due to the lack of schools and centers that attract adolescents with ASD in the city of Makkah, in addition to obtaining rejection from many parents. This is likely due to the sensitivity of the subject and parents’ fear to participate. Additionally, the small sample size reduces the generalizability of the study to additional regions in Saudi Arabia, so more research needs to be conducted to affirm the findings. There is also a risk of bias with a qualitative, multiple case study approach. The researchers were careful to extract personal opinions and had multiple professionals help with coding and data analysis. Additionally, the researchers were careful to establish intercoder reliability and agreement with the coded data. Finally, the possibility of a potential selection bias exists. Individuals with conservative views may not have felt comfortable participating in this study, due to the topic.

Recommendations and future research

The two researchers recommend early detection of sexual behavioral problems that appear during puberty and adolescence for people with ASD in order to reduce sexual challenges. Individuals with ASD must receive age-appropriate sexual education by their parents, beginning in childhood, so they are prepared for the changes and developments that occur to them during their different stages of growth. It is important special education teachers, or specialists, prepare special curricula on sexual education for people with ASD in all educational stages in a scientific and educational manner. Therefore, it is important special training programs are developed for adolescents and parents of individuals with ASD to address the challenges of sex education as they transition into adulthood. In addition to designing educational programs related to sexual education topics and testing their quality and effectiveness, it is helpful if special education teachers, or specialists, provide lectures and workshops on sexual education and its importance to educate the community, with the aim of sharing appropriate methods to meet the challenges of sexual education. It would also be helpful if the media issued content targeting adolescents with ASD, their parents, and society as a whole, by providing them with information related to sex education. Finally, it would be helpful if parents of teenagers with ASD were able to network and communicate about their successes and challenges. This could be done via technology, such as social media groups.

The researchers suggest conducting more research and studies on the concept of sex and reproductive health education for adolescents with ASD with the aim of accurately identifying the challenges that appear in this field, appropriate solutions, and strategies for the implementation of the proposed ideas. The current study focuses only on the city of Makkah, so additional research should be conducted to include additional regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia with different variables. Additionally, the current study focuses on the perspective of parents of adolescents with ASD. Additional research could include the perspective of teachers, including both general education teachers and special education teachers. The researchers also recommend the development of a training program that focuses on the process of conveying sexual knowledge and concepts by parents to their adolescent children with ASD.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Umm Al-Qura University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Abd Al-Karim, R. H. (2020). Qualitative research in education. 3rd Edn. Riyadh: Al-Rashid library.

Al-Khraif, R., Salam, A. A., Elsegaey, I., and Al-Mutairi, A. (2015). Changing age structures and ageing scenario of the Arab world. Soc. Indic. Res. 121, 763–785. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0664-0

Alomair, N., Alageel, S., Davies, N., and Bailey, J. V. (2021). Sexual and reproductive health knowledge, perceptions and experiences of women in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. Ethn. Health 27, 1310–1328. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2021.1873251

Al-subaie, A. S. (2019). Exploring sexual behaviour and associated factors among adolescents in Saudi Arabia: a call to end ignorance. J. Epidemiol. Global Health 9, 76–80. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.181210.001

André, T. G., Montero, C. V., Marquez-Vega, M. A., Ahumada-Cortez, J. G., and Gamez-Medina, M. E. (2020). Communication on sexuality between parents and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Sex. Disabil. 38, 217–229. doi: 10.1007/s11195-020-09628-1

Attaky, A., Schepers, J., Kok, G., and Dewitte, M. (2021). The role of sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction in the sexual function of Arab couples living in Saudi Arabia. Sexual Med. 9:100303. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100303

Ballan, M. S., and Freyer, M. B. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder, adolescence, and sexuality education: suggested interventions for mental health professionals. Sex. Disabil. 35, 261–273. doi: 10.1007/s11195-017-9477-9

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2020). What is gender? What is sex? CHIR. Available at: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48642.htm1 (accessed January 15, 2023).

Chamidah, A. N., and Jannah, S. N. (2017). “Parents perception about sexual education for adolescence with autism” in Proceedings of the 9th international conference for science educators and teachers (ICSET 2017) (Semarang: Semarang State University).

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Qualitative inquiry and research design. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., and Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Daghustani, W., and MacKenzie, A. (2022). Stigma, gendered care work and sex education: mothers’ experiences of raising autistic adolescents sons in socially conservative societies. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 3:100215. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2022.100215

Duvekot, J., van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., Slappendel, G., van Daalen, E., Maras, A., et al. (2017). Factors influ- encing the probability of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in girls versus boys. Autism 21, 646–658. doi: 10.1177/1362361316672178

El-Haddad, Y. (2003). Major trends affecting families in the Gulf countries. Bahrain: Social Science Department, Bahrain University College of Arts.

Fierloos, I. N., Windhorst, D. A., Fang, Y., Mao, Y., Crone, M. R., Hosman, C. M. H., et al. (2021). Factors associated with media use for parenting information: a cross-sectional study among parents of children aged 0–8 years. Nurs. Open 9, 446–457. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1084

George, R., and Stokes, M. A. (2017). Sexual orientation in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 11, 133–141. doi: 10.1002/aur.1892

Gergelya, R. H., and Rusu, A. S. (2021). A qualitative investigation of parental attitudes and needs for sexual health education for children with autism in Romania. J. Educ. Sci. Psychol. 11(73), 64–75. doi: 10.51865/JESP.2021.2.08

Gkogkos, G., Staveri, M., Galanis, P., and Gena, A. (2019). Sexual education: a case study of an adolescent with a diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified and intellectual disability. Sex. Disabil. 39, 439–453. doi: 10.1007/s11195-019-09594-3

Ho, S.-S., Holloway, A., and Stenhouse, R. (2019). Analytic methods’ considerations for the translation of sensitive qualitative data from mandarin into English. Int J Qual Methods 18:160940691986835. doi: 10.1177/1609406919868354

Holmes, L. G., Ofei, L. M., Merritt, M. H., Palmucci, P. L., and Rothman, E. F. (2021). A systematic review of randomized controlled trials on healthy relationship skills and sexual health for autistic youth. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 9, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s40489-021-00274-7

Holmes, L. G., Strassberg, D. S., and Himle, M. B. (2019). Family sexuality communication for adolescent girls on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 2403–2416. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03904-6

Horanieh, N., Macdowall, W., and Wellings, K. (2020a). Abstinence versus harm reduction approaches to sexual health education: views of key stakeholders in Saudi Arabia. Sex Educ. 20, 425–440. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2019.1669150

Horanieh, N., Macdowall, W., and Wellings, K. (2020b). How should school-based sex education be provided for adolescents in Saudi Arabia? Views of stakeholders. Sex Educ. 21, 645–659. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1843424

Ismiarti, R. D., Yusuf, M., and Rohmad, Z. (2019). Sex education for autistic adolescents. J. ICSAR 3, 74–78. doi: 10.17977/um005v3i12019p074

Lauretto, M. D., Nakano, F., Pereira, C. A., and Stern, J. M. (2012). Intentional sampling by goal optimization with decoupling by stochastic perturbation. AIP Conference Proceedings 1490, 189–201. doi: 10.1063/1.4759603

Lestari, L., and Aunurrahman, A. (2021). Sexual education for adolescent autism spectrum disorders: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Int. J. Commun. Med. and Public Health 8, 1625–1631. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20211210

Lester, J. N., Cho, Y., and Lochmiller, C. R. (2020). Learning to do qualitative data analysis: a starting point. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 19, 94–106. doi: 10.1177/1534484320903890

Lindqvist, A., Sendén, M. G., and Renström, E. A. (2020). What is gender, anyway: a review of the options for operationalising gender. Psychol. Sex. 12, 332–344. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2020.1729844

Mackin, M. L., Loew, N., Gonzalez, A., Tykol, H., and Christensen, T. (2016). Parent perceptions of sexual education needs for their children with autism. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 31, 608–618. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.07.003

Mann, L. E., and Traver, J. C. (2019). A systematic review of interventions to address inappropriate masturbation for individuals with autism spectrum disorder or other developmental disabilities. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 7, 205–218. doi: 10.1007/s40489-019-00192-9

Masoudi, M., Maasoumi, R., Effatpanah, M., Bragazzi, N. L., and Montazeri, A. (2021). Exploring experiences of psychological distress among Iranian parents in dealing with the sexual behaviors of their children with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative study. J. Med. Life 15, 26–33. doi: 10.25122/jml-2021-0290

Muslikhah, R., and Rudiyati, S. (2019). Identification sexual behaviour children with autism age 12-18 years. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Hum. Res. 296, 73–77. doi: 10.2991/icsie-18.2019.14

Othman, A., Shaheen, A., Otoum, M., Aldiqs, M., Hamad, I., Dabobe, M., et al. (2020). Parent–child communication about sexual and reproductive health: perspectives of Jordanian and Syrian parents. Sex. Reproduct. Health Matt. 28, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1758444

Planned Parenthood (2021). What is sex education?. Planned Parenthood. Available at: https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/for-educators/what-sex-education (accessed January 15, 2023).

Plexousakis, S., Gkintoni, E., Georgiadi, M., Kourkoutas, E., Halkiopoulos, C., and Roumeliotou, V. (2020). “Enhancing sexual awareness in children with autism spectrum disorder: a case study report” in Cases on teaching sexuality education to individuals with autism. ed. P. S. Whitby (IGI Global), 79–98.

Pryde, R., and Jahoda, A. (2018). A qualitative study of mothers’ experiences of supporting the sexual development of their sons with autism and an accompanying intellectual disability. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 64, 166–174. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2018.1446704

Pugliese, C. E., Ratto, A. B., Granader, Y., Dudley, K. M., Bowen, A., Baker, C., et al. (2019). Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a parent-mediated sexual education curriculum for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 24, 64–79. doi: 10.1177/1362361319842978

Rooks-Ellis, D., Jones, B., Sulinski, E., Howorth, S., and Achey, N. (2020). The effectiveness of a brief sexuality education intervention for parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 15, 444–464. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2020.1800542

Sala, G., Pecora, L., Hooley, M., and Stokes, M. A. (2020). As diverse as the spectrum itself: trends in sexuality, gender and autism. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 7, 59–68. doi: 10.1007/s40474-020-00190-1

Saudi Arabia Ministry of Education (2019). Islamic jurisprudence-level 6-secondary education. Riyadh: Ministry of Education.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., et al. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 52, 1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Sisk, L. M., and Gee, D. G. (2022). Stress and adolescence: vulnerability and opportunity during a sensitive window of development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.10.005

Solomon, D., Pantalone, D. W., and Faja, S. (2019). Autism and adult sex education: a literature review using the information–motivation–behavioral skills framework. Sex. Disabil. 37, 339–351. doi: 10.1007/s11195-019-09591-6

Stanojević, C., Neimeyer, T., and Piatt, J. (2021). The complexities of sexual health among adolescents living with autism spectrum disorder. Sex. Disabil. 39, 345–356. doi: 10.1007/s11195-020-09651-2

Teliti, A., and Resulaj, L. (2022). Adolescence in autism spectrum disorder and challenges encountered. Interdiscip. J. Res. Dev. 9, 42–47.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 27, 237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748

Turner, D., Briken, P., and Schöttle, D. (2017). Autism-spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood: focus on sexuality. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 30, 409–416. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000369

Wang, C. (2022). Analysis of how sex education in Asia is expressed in the media. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Hum. Res. 638, 951–954. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.220110.180

Weir, E., Allison, C., and Cohen, S. B. (2021). The sexual health, orientation, and activity of autistic adolescents and adults. Autism Res. 14, 2342–2354. doi: 10.1002/aur.2604

Keywords: challenges, sex education, adolescence, autism spectrum disorder, perspective

Citation: Shakuri MA and Alzahrani HM (2023) Challenges of sex education for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder from the Saudi family’s perspective. Front. Educ. 8:1150531. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1150531

Edited by:

Mohammed Saqr, University of Eastern Finland, FinlandReviewed by:

Ashley Johnson Harrison, University of Georgia, United StatesSusan Wilczynski, Ball State University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Shakuri and Alzahrani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hassan M. Alzahrani, aG1temFocmFuaUB1cXUuZWR1LnNh

Manar A. Shakuri1

Manar A. Shakuri1 Hassan M. Alzahrani

Hassan M. Alzahrani