95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 08 August 2023

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1140905

This paper analyzes the leadership learning model used by Spanish military commanders from the lifelong learning methodology. The lifelong learning approach consists of three main perspectives: a personal and professional context and how to achieve self-motivation and remain over time; the formal and informal learning sources, and how all this occurs throughout the individual life. Leadership is a fundamental military trait and should be treated as an ongoing process. This study examines how influences the lifelong learning of the Spanish military leaders from the Army, Navy, and Air Force in their leadership style. The methodology resource used is an online Delphi technique through in-depth interviews as well as the Qualitative Data Analysis & Research Software Atlas.it. This research shows that from a lifelong learning perspective, military leadership is built continuously throughout life and is supported by more informal than formal learning systems. The key findings of this research show that the Spanish military commanders’ leadership comes from an informal approach based on the different opportunities given at the workspace, individual job performance, and family support. From the formal system, the career ladder is supported both at the military academy and following regular training. The results show that a lifelong learning framework prepares Spanish military commanders to manage the highly complex environment in which they are involved.

Lifelong learning means the way people learn from different angles and time horizons. Lifelong learning pays attention to a personal and professional context (Drude et al., 2019) and how people could find self-motivation, to the formal and informal learning sources, and to the individual’s life cycle.

A leadership approach could be better understood from a long perspective because becoming a leader is not a brief and quick step. Leadership is not an easy comprehensive topic because of its tremendous complexity and enough paradoxes (Luedi, 2022). The birth of a leader does not take place at a specific time. It is related to so many aspects such as the situation, the contingency, the leader’s skills, or the personality of the individual members of the group, etc. Thus, various stimuli throughout their lives make leaders may set up their role and their behavior. People can be born with some abilities that are very close to the ideal leadership profile. Someone have to occupy a leadership role because of their professional activity. Or there are even some activities where becoming a leader is an obligation. In the military environment is what happens.

Leadership gets connected with a military environment. The Armed Forces use leadership as one of the most important rules to comply with their mission. Both terms are inseparable. The military environment does not make sense without a comprehensive approach to how leadership is managed. The Armed Forces use leadership as one of the most important rules for the mission to accomplish. The Armed Forces get based on organizations, roles, cultures, and people (Wong et al., 2003). The military field requires knowledge in very diverse scopes, given the complexity of combat and the cultural, sociological, and psychological factors that are part of today’s society (Scales, 2009; Laurence, 2011). The complexity of the environment exemplifies the need to interpret the leader construction process (Avolio et al., 2000) and the constant uncertainty in which it is involved.

This research got based on both lifelong learning as building military leadership and how could affect each other. People are continually learning, and it is increasingly necessary. Lifelong learning affects individual performance and content updates in the military environment. The leader is responsible for permanent learning both with himself or herself and the people around them. The effectiveness and willingness of the leader to train throughout life are related to the change in the organization (Caves, 2018). While the leader is formed throughout life and grows, the organization and its employees will also benefit.

Leadership produces an intensive narrative. The study’s approach to leadership makes Gardner et al. (2020) specify that in terms of their research, there has been no previous era with such a diverse, multidisciplinary body of knowledge on the subject or with such a broad focus. Other researchers, Aguilar-Bustamante and Correa-Chica (2017), show that the study of the concept shows certain elements that distinguish leaders and point out factors that define their style. There have also been approaches to develop models and theories that define both the concept of leadership and that of the leader, characterize it, and measure its performance (Blake and Mouton, 1982; Yammarino et al., 1993; Fiedler, 1996). However, leadership implementation in a dynamic environment makes it essential to incorporate context into the analysis (Avolio and Gardner, 2005). Military leaders have the chance to apply leadership skills throughout their careers in the diverse scenarios they live.

The leader-making process has a long journey according to the number of years from a military beginner joining the Military Academia to retirement age. Lifelong learning means that some skills model their growth and development through the individual’s life cycle. From the time a beginner joins the military academy until retirement happens, the military leadership learning model has a long journey. In each stage, they will make decisions of various kinds. Shamir and Ben-Ari (2000) warn of the similarity of the skills required for military commanders and for corporate managers, such as the ability to negotiate, persuade or work as a team. Once the young officers come out of the military academy should apply their knowledge to reality, while the college students’ demands take a more leisurely pace.

This research aims to analyze the learning process of a military leader. This research aims to analyze the learning process of a military leader from the lifelong learning perspective. Research on military leadership focuses on the results of performance evaluation as a leader (Cortina et al., 2004); leadership styles (Avolio and Gardner, 2005); situational factors (Campbell et al., 2010; Yammarino et al., 2010); behavior, skills, and attributes of the military leader (Horey et al., 2004, 2007); in the description of the qualities and character of the leader (Tritten and Keithly, 1995; Murray et al., 2019); among others. Nevertheless, they are not able to show a comprehensive approach and a time horizon as lifelong learning allows.

This research is innovative because it focuses on people of high rank and high skills and long experience as leaders and is part of an organization with many years of experience such as the Spanish Armed Forces. The lifelong learning approach allows a comprehensive approach to how the leadership role has been forged among senior officers of the Spanish armed forces. This research aims to specify the main features of the leadership learning model of Spanish military commanders from the lifelong learning methodology.

The main contribution of this research focuses on describing how military leadership is built throughout life from a lifelong learning perspective. The leadership path in the military is as specific as old, and their proper traits are not no common in other professional activities.

This paper situates the analysis into a distinct framework widely used for learning sources in educational and business organizations, the lifelong learning framework, and with its methodological design tries to explore the origin or sources that contribute to the configuration of the military leader from the experiences of the leaders themselves.

The article is organized as follows: in the next section, the state of the art on how a military leader gets built is concisely described, then subsequent parts depict the methodology and data. The last sections present the results of the analysis, the main findings, conclusions, and directions for further research.

Lifelong Learning (Field, 2000) is fundamental in leadership make. Those leaders who share their knowledge and experience with others are more likely to inspire growth and stimulate the emergence of more leaders within the group, which in turn is beneficial for the organization as a group. Companies need to take care of their values and habits to maintain this collaborative atmosphere.

Leaders should take responsibility for lifelong learning in two ways: with themselves and the people they lead. Workers thrive because they receive the support of their superiors and peers, which is essential for professional growth. The main goal in lifelong learning is continuous improvement, avoiding obsolescence in knowledge and loss of competitiveness. That is why workplaces present unique learning opportunities (Billett, 2020). The workplace environment should implement a long-term perspective. The high rotation and the lack of commitment prevent this orientation. By contrast, shared values, a collaborative attitude, and a strong culture help people to build a friendly working environment, both professional and personal.

Formal learning means a process followed by a person in an institutionalized, sequential, and standardized way with a determined duration and clear intentionality (Belando, 2017). Formal learning has to adapt continuously their contents and their methodologies. In the military field, this refers to learning in the military academies and on the various regulated courses, which constitute the basis of future leaders.

On the contrary, informal learning gets acquired in daily work, family, or leisure activities. Cross (2006) argues that informal learning accounts for between 60 and 80% of the learning process that happens in the workplace as long as the opportunities are offered by this type of space.

Formal and informal learning activities have used depending on the user’s age (Febrinanto et al., 2023). MOOC (Bordoloi et al., 2020) could provide knowledge to several people without discrimination.

Both systems, formal and non-formal, could participate in achieving the organization’s strategic goals and describe the new abilities and knowledge needed to increase professional development and career success (Drewery et al., 2020).

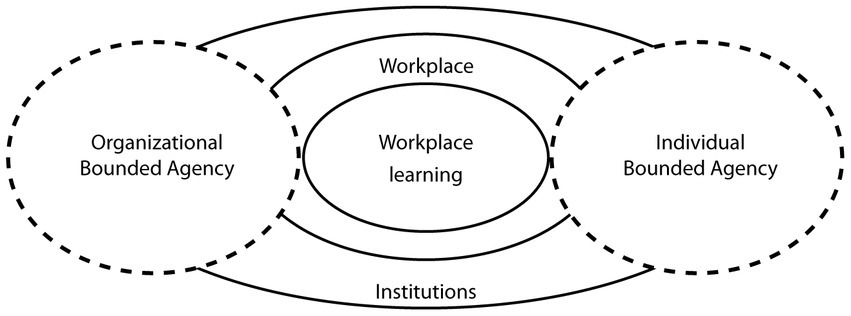

The workplace environment allows us to see an intersection between the person (everything that surrounds them in their personal life) and the organization (professional life). The concept of agency (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998) or agency in life course transitions (Evans, 2007) or in professional life (Eteläpelto et al., 2014) encompasses everything that surrounds the person and the organization. It has an innovative character at an individual, interpersonal, and collective level (Høyrup et al., 2012). Hefler (2019) introduces a reference framework (Figure 1) with a lifelong learning approach that enhances peoples belonging and becoming sense. It’s referred to someone who will keep relationships with him or herself, other people, groups, and institutions, and with all aspects of the outside world that have importance in his or her life (Levinson, 1980).

Figure 1. Workplace learning as a negotiated outcome between organizational and individual agency mediated by the workplace. Taken from the intersection of individual and organizational bounded agency in workplace learning – a comparative approach – chapter in the forthcoming D5.1 report on the ENLIVEN project (p. 23) by Hefler (2019), Vienna.

Learning goes beyond the assimilation of new knowledge or the acquisition of new skills (Nylander and Fejes, 2023). It is participation in the work process and in the social fabric of the workplace that contributes to the establishment of a feeling of belonging and identification as a member of an organization -socialization- and as a way of becoming -transformation- a leader (Biesta et al., 2011), related to institutionalized role models. Leaders should demonstrate their value added to transform organizations and how to face current and future challenges.

The framework for studying and explaining workplace learning gets based on insights from workplace learning, the sociology of work, organizational institutionalism, and the bounded agency framework (Evans, 2007) of individual career choices throughout life.

The organizational agency gets referred to everything that organizations entail in their broadest sense. Organizations are systems designed on purpose to achieve a common goal. Military organizations have, like other companies, their characteristics. The military should know the organization and all the frameworks to adapt to its requirements and should be able to grow professionally in it. That requires continuous learning. Informal learning in the workplace (Donato et al., 2017; Dyson, 2020), organizational structures and systems (Pires et al., 2021), or organizational learning itself (Dyson, 2019) are factors that influence organizational learning itself. The organization itself is an environment that will limit and enable the professional progression of officers. They will have to pay attention to the social relationships within the company itself, to the learning of group work (Goodwin et al., 2018), and especially the stratified social environment (chain of command) that permeates the organizational field and the individual living spaces and its structuring.

The learning opportunities that arise from coworkers (Stothard, Stothard and Drobnjak, 2021) play a determining role, allowing or limiting learning and future professional development and influencing the degree of commitment to the company (Wingerden and Poell, 2017; Liu et al., 2021). The 70-20-10 model (Johnson et al., 2018) holds that 70 percent of a person’s learning comes from workplace experiences, 20% from feedback, and 10% from the training process. That is, 90% of informal learning compared to 10% of formal learning. This means that the organization’s promotion systems should correctly understand where the learning systems come from to integrate them into efficiently.

The agency in workplace learning will depend on the opportunities offered by the company to the individual (Marble et al., 2020) and on the skills and attitudes (Atuel and Castro, 2018) that the person demonstrates on the job. There are company demands such as missions abroad, residence changes, change of friends, dangerousness, workplace tensions with colleagues, etc. Personal needs could be from the birth of a child or death of a loved one, prolonged absences due to missions abroad, and couple tensions to the lack of support at home. In many cases, both could cause conflict (Nayak and Pandey, 2021). Companies have to manage their work-life balance policies adequately and avoid inefficiencies and inequalities.

At the intersection between the organization and the individual, learning is concentrated in the workplace and on the job. The job position could get understood as a stable set of tasks assigned or adopted to a holder of a job located in the social fabric of an organization. It focuses on learning in the initial phases of work commitments, continuous learning in daily work, learning from non-routine activities (Koike and Inoki, 1990), learning from various approaches applied to support workplace learning and non-formal course learning related to current work, among others (Hefler, 2019). Moreover, it comprises in-group learning or in multifunctional teams (Dyson, 2020), learning from coworkers themselves (Goodwin et al., 2018) or in the relationship with superiors, as well as from unforeseen events (Hyllengren, 2017) or in problem-solving (Marcus, 2019).

Hefler (2019) includes individual subjectivity in the individual learning agency. It refers to the individual identity within the organization and the daily experience in the workplace. Learning ambition, training attendance, or professional decisions also play a role. In addition, work at home, civic commitments, free time activities, or their relationship with family (Vest et al., 2017) and friends (Warner et al., 2008) get included.

The military leader develops through a continuous, career-wide process that aims to increase knowledge, skills, and abilities through operational task experience, formal education and training, and self-development (Wong et al., 2003). Additionally, the competencies of these leaders get optimally developed through various responsibilities in multiple hierarchies (Deny, 2021), which facilitates continuous learning subject to different stimuli.

Personality traits, attitude to circumstances, or predisposition sow the leader’s ground. In the military field, strength of character gets correlated with good leadership (Georgoulas-Sherry, 2021). Nevertheless, military leaders express certain peculiarities. Thus, Armada (2008) has developed its leadership model based on a peculiar and challenging environment with a level of risk, prolonged absences from the family environment, and a continuous coexistence between the staff in small and limited places and spaces. In the military field, the occupation of a job automatically implies authority over a group of people.

Authority gets identified in the uniform (Wong et al., 2003). A promotion gets obtained as a result of overcoming training or promotion processes. In the civil environment, a young college graduate does not automatically have any formal authority unless his job position allows it. Fallesen et al. (2011) appreciate that, commonly, leadership describes three assumptions: the individual, which points to the person who is the leader; the capacities, focused on the competencies necessary to perform the role and, finally, the process, the practice of a set of behaviors to direct others. The leader and the organization impact each other because leadership determines the success or failure of an organization (Robinson, 2021), each organization defines its different levels of decision-making, and each leader knows their limits. The leader should take advantage of the learning process and grow personally and professionally, which reverts to organizational progress (Örtenblad, 2019).

The organization gets support with limits on behaviors that are far from the norm (Ledberg et al., 2021) and enriches its cultural framework with procedures, experiences, traditions, and behavior patterns that, in turn, impact prevailing leadership models (Shamir et al., 2000). The leadership models also bring together the specific characteristics of the environment: a) specific demands in the naval field or b) the development of leadership skills in an environment suitable for it (Kumar and Jain, 2021). Without coupling to the environment, insertion is not possible.

Challenges happening in societies have strengthened the working-life balance. Diverses measures have emerged to support the military displaced from home, such as constant means of communication, help for the family through veterans’ associations, and aid for more effective reincorporation upon return, among others (Ben-Ari and Kawano, 2020). Even the alleged inbreeding is gradually decreasing (Martínez, 2004; Escarda, 2012). The family plays a role in their career development (Ministry of Defense, 2021).

The mission constitutes a source of leadership application. The success of mission command (MC) will depend on being integrated into organizational culture and not simply being a method of command (Nilsson, 2021) since it provokes independent decision-making more quickly in environments with a lack of information (Krabberød, 2014). Each soldier is responsible for the fulfillment of the entrusted mission.

The example of others inspires leadership to apply (Shamir et al., 2000; Montaño et al., 2005; Bunin et al., 2021). Military leaders learn from their commanders in terms of operational skills as behaviors are applied to their teamwork. These attitudes get supported by ethical and moral rules. Besides, have to respond to society’s requests and lead the military leader’s performance (Moliner, 2020; Gomes and Lopes de Barros, 2021; Trehan and Soni, 2021). Armed Forces develop their own talent management system to promote people and describe their career ladder.

Their own experiences provide support for the leader (Haidar, 2021). The application to the daily life of the training received, the sensations that learning leaves them, and the decisions made are part of the continuous feedback they receive. In addition, the experience feeds on feedback from evaluation systems. Precise feedback guarantees the development of leaders (Meumann and O’Neil, 2020) and supports promotion systems. Feedback takes part of the lifelong learning process as a leader took to develop performance followers (Crans et al., 2022) and impact the continuous improvement of individual performance.

This research, like many in the last 5 years, has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although it seems strange to point it out in the methodology section, it is relevant to understand the circumstances in which the results were obtained. Initially, this research was designed to propose a series of in-depth interviews on the topic of leadership in military leaders. The research team decided to conduct in-depth interviews because of the wealth of data obtained and the experience of the colonels interviewed. During the year 2020, and given the impossibility of conducting personal interviews with military leaders, the research team decided to rethink the instruments and derive the strategy towards a Delphi method “adapted to the circumstances” in which the research had to be launched (Dalkey and Helmer, 1962). There was the voluntary participation of 42 military leaders, considered experts. It was a unique opportunity to raise a specific issue, using questionnaires sent individually repeatedly, using the QUALTRICS platform for the automatic sending and registration of data, and whose results are returned in the form of feedback creating an opinion of the group. Although the objective of this research was not the search for consensus on the issue of military leadership, the truth is that the Delphi method allows participants to have knowledge and experience on the subject, and anonymity in the answers prevents people from influencing others’ opinions. As some authors point out (Martínez-García et al., 2019), the use of the mixed methodology with qualitative and quantitative procedures enables a process of data analysis. In this research, we opted for the exploitation of open questions and we analyze those nuances that emerge from participants’ testimonies.

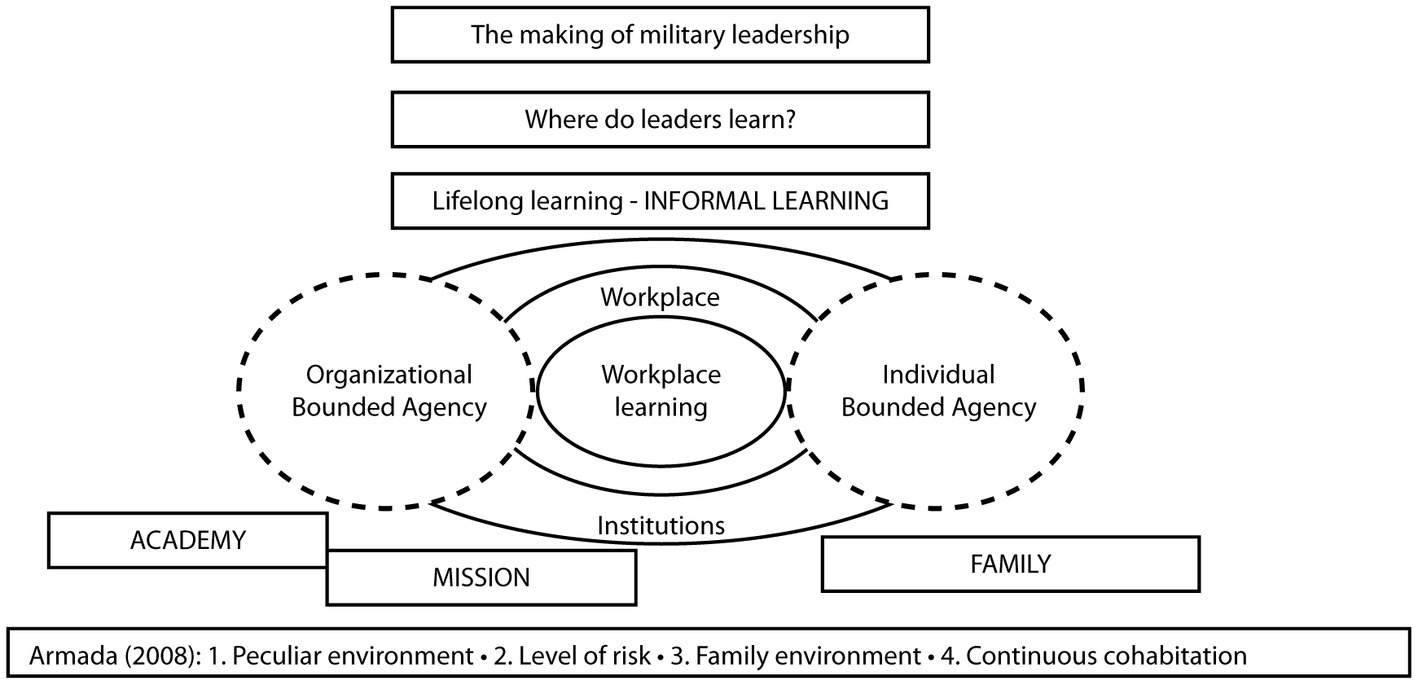

Both for the design procedure of the questions to be included in the questionnaire and for the content analysis of the results of the open questions, this research was based on a framework generated ex profeso (Figure 2) in which the approach of lifelong learning, with a special interest in informal learning in the workplace (Cross, 2006; Dyson, 2019) together with 4 specific aspects of the military profession obtained from the work of la Armada (2008) and which are specified in the following graph.

Figure 2. Main elements for result design and analysis. Own elaboration, adapted from Hefler (2019) and Armada (2008).

This approach led to the specification of these elements in questions launched in an online questionnaire divided into two phases for which the QUALTRICS platform was used during the months of October and November 2020.

For the research approach, the Delphi panel technique was proposed, asking the group of experts their opinion on the process of learning leadership. In this regard, the collaboration of 42 expert colonels in the field was requested.

The experts’ assessments were carried out in two successive rounds with their respective feedback: the first round in October (2020), and the second round in November (2020). Consensus was sought while allowing maximum autonomy and confidentiality to the participants. In the first Delphi round, colonels were asked about learning leadership in the military context, key leader competencies and team management. A total of 29 questions were asked including multiple choice, rating scale, Likert scale, ranking, dichotomous and open-ended questions. The average response time was 25.4 min. In the second Delphi round (39 questions), taking into account the results obtained in the first round, the experts were also asked to make an assessment of the results of the previous round and to identify the factors that shape leaders for future challenges. The average response time was 18.7 min.

The open questions to be answered were about: the experiences and professional career events that marked them as leaders; family and personal experiences outside the workplace that have contributed to them becoming leaders; the role of the military academy, its superiors, its team, the missions, as well as the resources and barriers for the formation of the military leader. All the information was collected in writing, with no need for transcription.

The invited sample was the 95 colonels participating in the promotion course to become a General, of which 42 of them agreed to participate, which is the sample participating in the study. The participating were 42 experts. All of them are colonels with more than 30 years of experience leading teams. Their average age is 53.9 years. At the time of the research, there were 1,050 colonels in Spain. Only 95 colonels, belonging to the Army, Navy and Air Forces, were taking the General promotion course. These are the elite and 42% of the military personnel selected for the general promotion course are participants in this study.

A loss of subjects was expected throughout the two phases. However, given the high level of participation, it was decided not to replace this loss. The informants were selected following the criteria of: being military leaders who occupied, at the time of research, either the position of colonel, or that of ship captain, which in the Armed Forces represents the highest rank; have a long track record in team leadership, missions, etc.; and represent all 3 branches: Army, Navy, and Air Forces (Table 1).

It should be noted that there was one woman participating among sampled experts. However, to preserve anonymity and confidentiality, no segmentation was carried out in this regard. It was decided to carry out the analyzes based on the three branches under analysis.

The questionnaire created for the first phase had open questions that do not condition the direction of the answers and favor the generation of testimonies that are the object of deeper analysis due to the nuances that are expressed. In a second phase, a summary of the main results was provided and that the participants had to comment. Together with these results, other questions with a higher level of precision were sent to them.

To analyze the testimonies provided in the open questions, two coding cycles were established. A hybrid method of thematic analysis of the data was used, using both inductive and deductive reasoning (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2006). A first cycle was set with a deductive nature for which the following codebook was generated in two clear dimensions of the framework of lifelong learning: organizational and individual level (see Table 2). We proceeded to develop an initial codebook for the data analysis, based on the research objectives. We then refined the codebook based on issues that arose during the analysis. The third author developed the initial codebook and shared it with the rest of the authors. The codebook was discussed, refined, and imported into the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti. The codebook was tested by coding the transcripts of the first four interviews by three authors independently. Their coding was virtually similar, so the codebook was not modified. Following the theoretical approach presented previously, the initial categories were developed for both levels. In a second coding cycle, the categories related to the elements that are specific to the military leader and described by La Armada (2008) emerged. In this phase of analysis, the qualitative analysis software ATLAS.ti was used.

At all times, the confidentiality and treatment of the data of the study participants was guaranteed, using anonymization both in the responses and in subject participating. The University of Deusto Research Ethics Committee qualifies the project as FAVOURABLE (9 May 2020) and states that the project is appropriate (ETK-32/19-20) from an ethical point of view.

The presentation of the results will be divided into two parts, which corresponds to the proposed framework. A first part will expose the results on the learning of military leaders based on the organization in which they develop their profession, and a second part with the results linked to the individual sphere that are related to the construction of that leadership.

From the first exploration of the data, it is clear that military leaders learn and are made in the organization. The foundation obtained in the following initial categories raised thus attest to this. Table 3 presents the categories according to the organizational and the individual level, ordered by their weight with respect to the total number of categories used.

All three branches have similar behavior. In this sense, the military leader relies on informal learning in the workplace (148 citations), which is a characteristic element of the Armed Forces that has been registered in the category “Work organization and workplace” (126 citations). The peculiarity of the “job ladders,” together with the “formal career pathways,” is that they contribute to making leaders to the extent that they must assume leadership functions as they go through the chain of command.

Regarding informal learning in the workplace (Table 4), there is a strong representation of learning as part of a team or from a team (37 citations). Without a doubt, they learn to be leaders while being leaders, that is, in the process of performing their jobs (27 citations), but this leadership requires a team from which to learn and with whom to learn to be a leader.

Table 4. Rationale for the subcategories responsible for the weight of informal learning in the workplace.

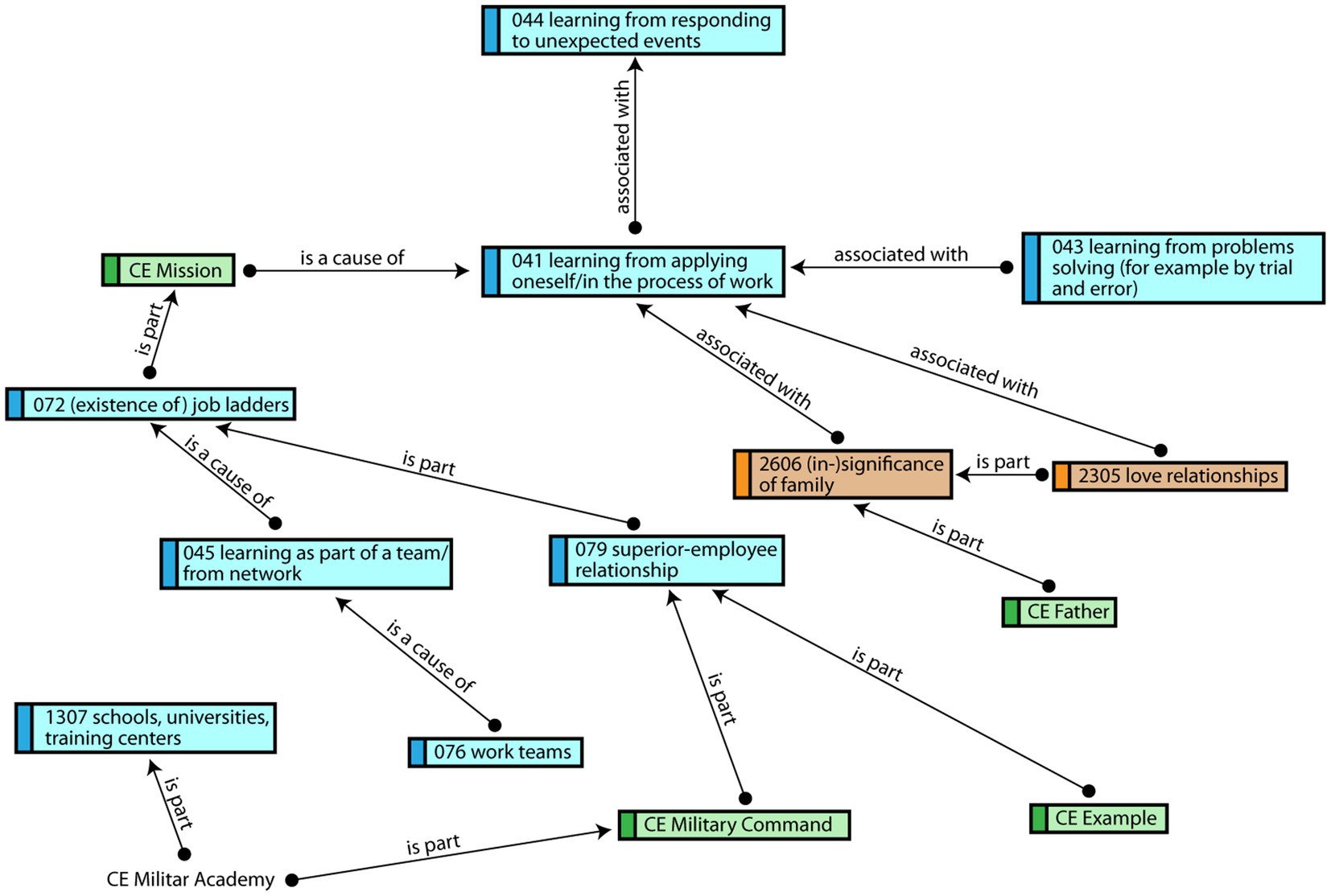

In this team, the relationship between superior and employee takes on a relevant importance. The military leaders interviewed recognize in the superior-employee relationship one of the most important sources of learning, especially their colleagues who have served with their example. It is at this point, where the making of the leader is linked to the individual sphere since, when it comes to understanding role models, father figures -occasionally military men themselves and otherwise embodiments of relevant values- strongly come up (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. Graphic representation of the military leader-learning model. Representation of the initial categories linked to learning at the organizational level and at the individual level and specific categories related to the specificity of military leadership.

Regarding relevant figures, there are also mentions of certain teachers at the Military Academy who, over time, have become important role models or references.

On the other hand, the main source of learning is problem solving and, above all, responding to unexpected events (23 quotes) or, to capitalize, answering in the face of unexpected difficulties that come up in missions.

These data break with the image of a leader with qualities that are innate or leaders with specific personality types. The military leader is a leader made in the process of work, of the mission. When trying to graphically represent the learning or construction model of military leadership, together with the initial categories related to the organization (blue color) and those related to the individual sphere (orange color), three important elements emerged in the second coding cycle, some of which we have already mentioned above: superiors as role models; the father figure who embodies a series of values related to military values; the role played by missions as the space where the leader is built based on decision-making in the face of unexpected events, as part of a team; and the role played by the Military Academy as a starting point for the construction of the military leader.

In this model, which describes the making of a leader considering the organization’s resources, colleagues, the Military Academy, and the very structure or idiosyncrasy of the organization, two elements related to the individual sphere also come up: 1. The importance assigned to acquiring experience throughout the process 2. The importance of being subjected to persistent challenges forces the leader to constantly learn.

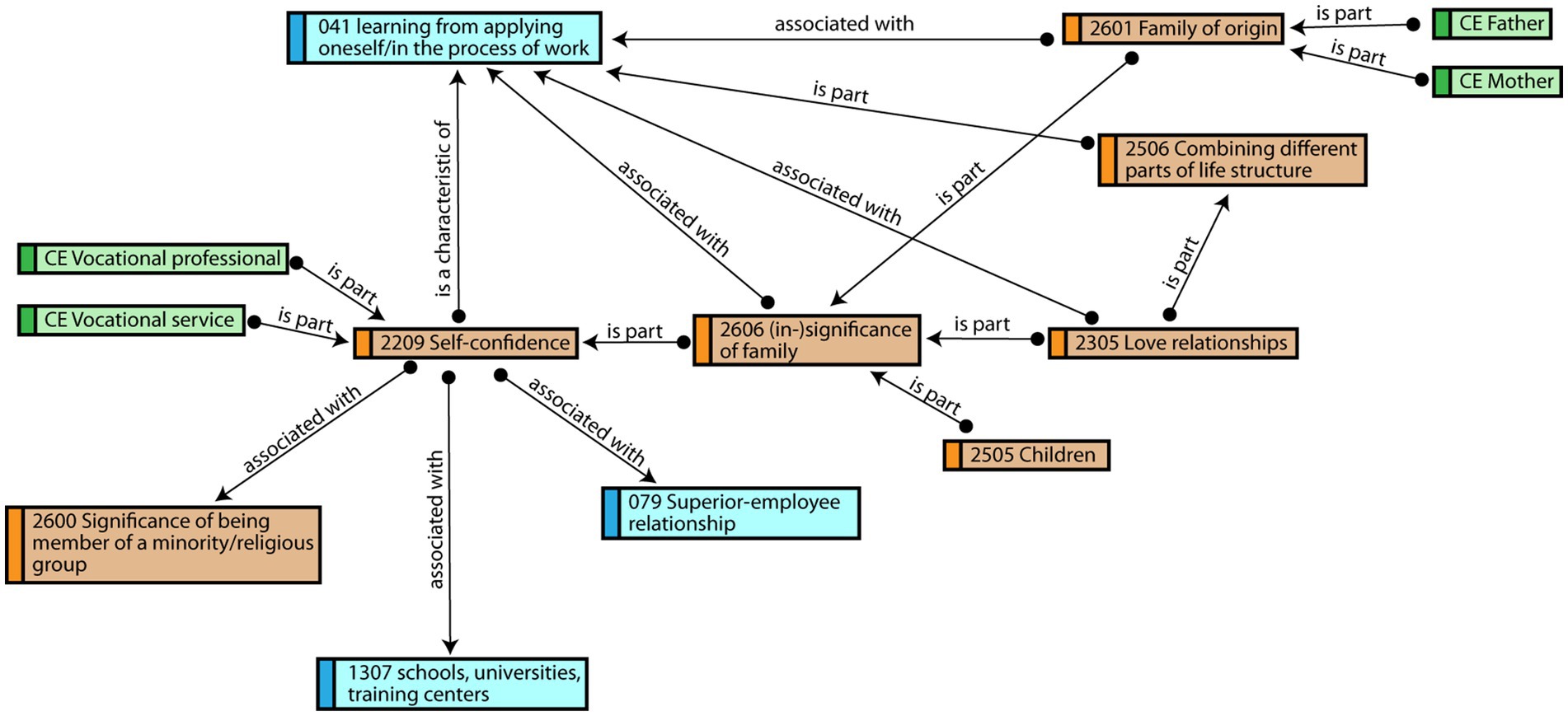

In a second moment, the results are presented on the exploration of the proposed categories (Table 5) with the aim of discovering which elements of the individual sphere are present in the learning and construction of a military leader. Based on the foundation of the citations to the initial categories raised, the anchors of identity (65 citations) together with professional development (46 citations) are the two axes on which the leader is based.

The identity anchors are configured in turn by two subcategories: the relevance of the family (28 citations), and the family of origin (22 citations). The significance of the family appears strongly, with constant references to the values of the family of origin. As well as the role played by partners as facilitators of the reconciliation military leaders, have to do of their profession and their familial responsibilities.

Regarding the individual sphere, “professional development” also has an important weight, which is linked to “self-confidence” as one of the catalysts for the development of the military leader. In this self-confidence, both the personal and individual characteristics of the leader are grouped, as well as the values that move this military leader. Along with “self-confidence,” there are links with the superiors-employees relationship and the role of the Military Academy, so it is understood that the leader needs to reach a certain level of self-confidence, as well as the example of his superiors, and the knowledge and values that are transmitted in the Military Academy.

Figure 4 represents the making of a military leader with the elements mentioned in the individual sphere (in orange) and those that are linked to the organizational sphere (in blue) and elements that have emerged in the second coding cycle, which are represented in green. One of the emerging elements constituting self-confidence is worth underscoring: the term vocation. In this sense, the interviewed leaders recognize vocational aspects of public service in their profession.

Figure 4. Graphic representation of the military leader construction model according to the codes of the individual sphere. Representation of the initial categories linked to learning at the individual level and categories related to the specificity of military leadership.

The results of the research show that Armed Forces military leaders support their learning in informal learning in the workplace due to the opportunities offered in that space (Cross, 2006), according to the 70-20-10 model (Johnson et al., 2018); and, through their job performance, that means, work experience (Deny, 2021). The experiences lived as leaders serve as raw material to be used (Haidar, 2021) in the continuous decision-making process in which they are involved.

Spanish Armed Forces military leaders find informal learning in the workplace is eased by three variables. First of all, as a consequence of being part of a group. Each team member is proud to belong to it. In this case, the Navy stands out compared to the Land or Air Force due to the specific characteristics of the naval environment. In the second term, leaders learn how to lead through learning by doing. Third, learning from their peers generates new knowledge and encourages commitment to the organization and the group (Wingerden and Poell, 2017), a vital addition to cohesion.

Regarding the learning on the job performance, Armed Forces leaders highlight the superior/subordinate relationship. The behavior of others is an inspiration for the exercise of leadership (Shamir et al., 2000), even if an inferior rank. Teamwork is key to military organizations’ identity. Stages in the professional career enable the leader to consolidate the past to face the future (Wong et al., 2003). The responsibilities assumed in the previous steps (Deny, 2021) allow them to achieve the highest competence degree. Effectively leadership advantages from a suitable environment (Kumar and Jain, 2021) with a leadership adaptative to possible changes (Nazri and Rudi, 2019) and fit with the feedback they obtained.

In the military leader’s formal learning, the Military academy influence emerges. Leadership starts in the first training stages and continues throughout their career (Gomes and Lopes de Barros, 2021; Marshall, 2021; Trehan and Soni, 2021; Werber, 2021). Their teachers inspire them in a stage where character and certain behavioral traits get forged. Both will probably will remain unchanged throughout their career.

Mission fulfillment supposes practice leadership. The success of the mission command (Nilsson, 2021) has to do with the required leadership. It implies assuming different responsibilities in multiple hierarchies (Deny, 2021), facilitating lifelong learning.

Research has revealed the importance of the mission in military learning and career growth. The informal learning process happens in the mission day-to-day with the team members, in the process of mission execution, and from the colleagues themselves, as well as from adapting to changes (Nazri and Rudi, 2019). It also responds to unexpected events that constitute key elements in the construction of leadership linked to the mission.

The mission command allows valuing the leader’s skills. It is the way to demonstrate worth and achieve professional merits and recognition from others. Leaders get forged at Miltary Academy and home supported by family and friends (Skomorovsky et al., 2019). Nevertheless, leaders develop in the missions carried out throughout their professional life. It is there where opportunities for growth as a leader will arise, with the rest of the group (Wingerden and Poell, 2017), solving and responding to upcoming challenges and difficulties.

Military leaders lead by doing (Gomes and Lopes de Barros, 2021; Werber, 2021). They perform leadership aimed at successfully fulfilling the entrusted missions. There is no other way to be a leader than to exercise leadership. The mission command constitutes the opportunity for personal and professional growth.

This research confirms that a familiar environment anchors leaders’ identity (Ministry of Defense, 2021). Family serves as a fundamental support for career military development. Organizations should integrate work-life balance (Nayak and Pandey, 2021) to avoid disagreements and disappointment.

The results of this research are aligned with previous research where the importance of experience in the development of a leader throughout life is analyzed (Grunberg et al., 2019; Kolenda, 2021; Vogel et al., 2021).

The Armed Forces educate and train their leaders constantly and periodically. Resources are allocated annually for this purpose. People who choose this profession have to be assessed regarding their cognitive and physical ability, their aptitudes, personality, and knowledge of various subjects to start a military career. After completing the training period in the military academies and fulfilling the requirements, either as officers or as non-commissioned officers, they will exercise leadership with their teams. Their performance will take place in complex and uncertain environments.

This article has analyzed the making of the military leader. The approach has been oriented to scrutinize the learning process of military leaders, from the perspective of the factors and stages that make up the modeling of said leader. It entails a lifelong learning process.

Leadership supposes a habitual and automatic task in the daily work of military leaders. The collective and individual spheres, informal and formal learning, the specific type of work, the influence of continuous training or the influence of their closest environment have an impact on their performance as leaders.

Military leaders exercise their role and get feedback mainly from informal learning. This learning comes both from the opportunities offered by their work space and from the exercise of their functions, or “on-the-job experience.”

The workspace assigns them membership in a group, making it easier for them to assimilate the leadership models they find useful. They take their own bosses as examples and take the opportunity to add the optimal behaviors of colleagues and subordinates to their wealth of skills. To their leadership reference models of leadership, they will add the imprint left by professors from the Academies where they have been trained, and depending on the case, by their own father figures. The work process provides them with the experiences of the lived experiences and the overcoming of the challenges that the missions force them to fulfill. The fulfillment of the mission is the raison-d’être of the military leader. The frame of reference guides their behavior and the decisions they make. The military leader conforms and is made in the mission, in performance with the team, and in the assiduous application of the leadership role.

Formal learning is provided by the training and education that he receives at the Academy and the teachings drawn from the successive job ladder, a known itinerary that generates the necessary skills and knowledge to apply in the next phase.

The collective and social sphere of the military leader’s development is strengthened by the network of protection and support provided by family, relatives, and friends. Partners keep the structure at home. Military leaders, when exercising their mission are physically away from their closest environment, and find vital support in their family.

The contribution of this research focuses on analyzing military leadership as a process per se, beyond personality characteristics, relationships with subordinates, task orientation or other common approaches to date. Military leadership is complex, complex due to the environment in which it is practiced and due to the multiple factors that affect it.

The limitations of the research come, fundamentally, from two different origins. First, due to the bias of the leaders who have participated, which comes from all leaders exercising tactical leadership and no presence of leaders at the operational and strategic levels. Second, there is a gender limitation due to the scarce presence of women. It would be explained by the fact that the incorporation of women into military organizations is recent. The number of women that have been incorporated is still scarce and, therefore, they are still to reach tactical ranks.

As implications for future research, we can indicate the convenience of deepening the preparation of lifelong learning opportunities to be able to accelerate the path that the military takes from tactical to strategic leadership, passing through operational. These opportunities can speed up or slow down the process in a clear way.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were approved by the University of Deusto Research Ethics Committee (ETK-32/19-20). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

FD, PM-M, and MA-C contributed to conception and design of the study. FD organized the interviews and database. MA-C performed the statistical analysis. FD and PM-M wrote the first draft of the manuscript and wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research received external funding from de Ministerio de Defensa Español.

To the Ministerio de Defensa Español, which has funded this research through the “Juan Sebastián Elcano” agreement signed with the University of Deusto. To Colonel José Luis Calvo Albero, Director of the Security and Defence Coordination and Studies Division. To the Colonels of the Army, Navy and Air Force, as well as the Common Corps of the Army, for their voluntary participation in the research.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aguilar-Bustamante, M. C., and Correa-Chica, A. (2017). Análisis de las variables asociadas al estudio del liderazgo: una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Univ. Psychol. 16, 1–13. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.upsy16-1.avae

Armada, Española. (2008). Modelo de liderazgo en la Armada Española. (Ministerio de Defensa) Available at: https://armada.defensa.gob.es/ArmadaPortal/page/Portal/ArmadaEspannola/mardigitaldocinstituc/prefLang-es/00docu-institucional-armada+--07modelo-liderazgo-armada (Accessed July 15, 2021).

Atuel, H. R., and Castro, C. A. (2018). Military cultural competence. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 46, 74–82. doi: 10.1007/s10615-018-0651-z

Avolio, B. J., and Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 16, 315–338. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001

Avolio, B. J., Kahai, S., and Dodge, G. E. (2000). E-leadership: implications for theory, research, and practice. Leadersh. Q. 11, 615–668. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00062-X

Belando, M. R. (2017). Aprendizaje a lo largo de la vida: Concepto y componentes. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 75, 219–234. doi: 10.35362/rie7501255

Ben-Ari, E., and Kawano, H. (2020). Military and Society in Israel and Japan: Family Support, Mental Health and Public Support. Japan: Center for Global Security.

Biesta, G., Field, J., Hodkinson, P., Macleod, F. J., and Goodson, I. F. (2011). Improving Learning Through the Lifecourse: Learning Lives. London: Routledge.

Billett, S. (2020). Learning in the Workplace: Strategies for Effective Practice. London: Routledge.

Blake, R. R., and Mouton, J. S. (1982). Theory and research for developing a science of leadership. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 18, 275–291. doi: 10.1177/002188638201800304

Bordoloi, R., Das, P., and Das, K. (2020). Lifelong learning opportunities through MOOCs in India. Asian Assoc. Open Univ. J. 15, 83–95. doi: 10.1108/AAOUJ-09-2019-0042

Bunin, J. L., Chung, K. K., and Mount, C. A. (2021). Ten leadership principles from the military applied to critical care. ATS Sch. 2, 317–326. doi: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2020-0170PS

Campbell, D. J., Hannah, S. T., and Matthews, M. D. (2010). Leadership in military and other dangerous contexts: introduction to the special topic issue. Mil. Psychol. 22, S1–S14. doi: 10.1080/08995601003644163

Caves, L. (2018). Lifelong learners influencing organizational change. Stud. Bus. Econ. 13, 21–28. doi: 10.2478/sbe-2018-0002

Cortina, J., Zaccaro, S., McFarland, L., Baughman, K., Wood, G., and Odin, E. (2004). Promoting Realistic Self-Assessment as the Basis for Effective Leader Self-Development. ARI Research Leader Development Research Unit 1–69. Applied Research International. New Delhi

Crans, S., Aksentieva, P., Beausaert, S., and Segers, M. (2022). Learning leadership and feedback seeking behavior: leadership that spurs feedback seeking. Front. Psychol. 13:890861. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.890861

Cross, J. (2006). Informal Learning: Rediscovering the Natural Pathways that Inspire Innovation and Performance. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Dalkey, N., and Helmer, O. (1962). An Experimental Application of the Delphi Method to the Use of Experts. California: The RAND Corporation.

Deny, W. (2021). Senior Military Leadership in Domestic Operations: An Exploratory Study. Homeland Security Affairs 17, 1–34. Washington, DC.

Donato, A., Hedler, H. C., and Coelho, F. A. (2017). Informal learning exercise for TIC professionals: a study at the superior military court. RAM. Revista de Administração Mackenzie 18, 66–95. doi: 10.1590/1678-69712017/administracao.v18n1p66-95

Drewery, D. W., Sproule, R., and Pretti, T. J. (2020). Lifelong learning mindset and career success: evidence from the field of accounting and finance. High. Educ. Ski. Work-Based Learn. 10, 567–580. doi: 10.1108/HESWBL-03-2019-0041

Drude, K. P., Maheu, M., and Hilty, D. M. (2019). Continuing professional development: reflections on a lifelong learning process. Psychiatr. Clin. 42, 447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2019.05.002

Dyson, T. (2019). The military as a learning organisation: establishing the fundamentals of best-practice in lessons-learned. Def. Stud. 19, 107–129. doi: 10.1080/14702436.2019.1573637

Dyson, T. (2020). A revolution in military learning? Cross-functional teams and knowledge transformation by lessons-learned processes. Eur. Secur. 29, 483–505. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2020.1795835

Emirbayer, M., and Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? Am. J. Sociol. 103, 962–1023. doi: 10.1086/231294

Escarda, M. G. (2012). La familia en las Fuerzas Armadas españolas. [dissertation thesis] Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia.

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., and Paloniemi, S. (2014). “Identity and Agency in Professional Learning” in International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-Based Learning. eds. S. Billett, C. Harteis, and H. Gruber (Dordrecht: Springer), 645–672.

Evans, K. (2007). Concepts of bounded agency in education, work, and the personal lives of young adults. Int. J. Psychol. 42, 85–93. doi: 10.1080/00207590600991237

Fallesen, J. J., Keller-Glaze, H., and Curnow, C. K. (2011). A selective review of leadership studies in the US Army. Mil. Psychol. 23, 462–478. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.600181

Febrinanto, F. G., Xia, F., Moore, K., Thapa, C., and Aggarwal, C. (2023). Graph lifelong learning: a survey. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 18, 32–51. doi: 10.1109/MCI.2022.3222049

Fereday, J., and Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 5, 80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107

Fiedler, F. E. (1996). Research on leadership selection and training: one view of the future. Adm. Sci. Q. 41, 241–250. doi: 10.2307/2393716

Gardner, W. L., Lowe, K. B., Meuser, J. D., Noghani, F., Gullifor, D. P., and Cogliser, C. C. (2020). The leadership trilogy: a review of the third decade of the leadership quarterly. Leadersh. Q. 31:101379. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101379

Georgoulas-Sherry, V. (2021). The influence of resilience and expressive flexibility on character strengths and virtues on military leadership in US military cadets. J. Wellness 3:4. doi: 10.18297/jwellness/vol3/iss2/4

Gomes, J., and Lopes de Barros, N. (2021). The role of military leadership in the socio-professional configuration of Portuguese police administrative elites. Rev. Militar 5, 417–442. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/36634

Goodwin, G. F., Blacksmith, N., and Coats, M. R. (2018). The science of teams in the military: contributions from over 60 years of research. Am. Psychol. 73, 322–333. doi: 10.1037/amp0000259

Grunberg, N. E., Barry, E. S., Callahan, C. W., Kleber, H. G., McManigle, J. E., and Schoomaker, E. B. (2019). A conceptual framework for leader and leadership education and development. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 22, 644–650. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2018.1492026

Haidar, R. (2021). Desertion and Discipline: How British Soldiers Influenced the Military Justice System During the Seven Years’ War. dissertation thesis Canada: University of Windsor.

Hefler, G. (2019). The intersection of individual and Organisational bounded Agency in Workplace Learning - a comparative approach – Chapter in the forthcoming D5.1 report on the ENLIVEN project. Vienna.

Horey, J., Fallesen, J. J., Morath, R., Cronin, B., and Cassella, R. (2004). Competency Based Future Leadership Requirements. Virginia: Caliber Associates Fairfax.

Horey, J., Harvey, J., Curtin, P., Keller-Glaze, H., Morath, R., and Fallesen, J. (2007). A Criterion-Related Validation Study of the Army Core Leader Competency Model. Virginia: Caliber Associates Fairfax.

Høyrup, S., Bonnafous-Boucher, M., Hasse, C., and Moller, K. (ed.) (2012). Employee-Driven Innovation: A New Approach. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hyllengren, P. (2017). Military leaders’ adaptability in unexpected situations. Mil. Psychol. 29, 245–259. doi: 10.1037/mil0000183

Johnson, S. J., Blackman, D. A., and Buick, F. (2018). The 70: 20: 10 framework and the transfer of learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 29, 383–402. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.21330

Koike, K., and Inoki, T. (Eds) (1990). Skill formation in Japan and Southeast Asia. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Krabberød, T. (2014). Task uncertainty and mission command in a naval context. Small Group Res. 45, 416–434. doi: 10.1177/1046496414532955

Kumar, M. V., and Jain, R. K. (2021). Study of skills & qualities of Indian military veterans valued Most by employers and colleagues. Int. J. Humanit. Manag. 5, 58–64. doi: 10.35940/ijmh.F1294.045821

Laurence, J. H. (2011). Military leadership and the complexity of combat and culture. Mil. Psychol. 23, 489–501. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.600143

Ledberg, S. K., Ahlbäck Öberg, S., and Björnehed, E. (2021). Managerialism and the military: consequences for the Swedish armed forces. Armed Forces Soc. 1–25. doi: 10.1177/0095327X211034908

Levinson, D. J. (1980). “Toward a conception of the adult life course” in Themes of Work and Love in Adulthood. eds. N. J. Smelser and E. H. Erikson (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press), 265–290.

Liu, Z., Venkatesh, S., Murphy, S. E., and Riggio, R. E. (2021). Leader development across the lifespan: a dynamic experiences-grounded approach. Leadersh. Q. 32:101382. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101382

Luedi, M. M. (2022). Leadership in 2022: a perspective. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 36, 229–235. https://doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2022.04.002. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2022.04.002

Marble, W. S., Cox, E. D., Hundertmark, J. A., Goymerac, P. J., Murray, C. K., and Soderdahl, D. W. (2020). US Army medical corps recruitment, job satisfaction, and retention: historical perspectives and current issues. Mil. Med. 185, e1596–e1602. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usaa094

Marcus, R. D. (2019). Learning ‘under fire’: Israel’s improvised military adaptation to Hamas tunnel warfare. J. Strateg. Stud. 42, 344–370. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2017.1307744

Marshall, S. (2021). The leadership gap: is there a crisis of leadership in anaesthesiology? South. African J. Anaesth. Analg. 27, 112–114. doi: 10.36303/SAJAA.2021.27.3.2629

Martínez, R. (2004). Quiénes son y qué piensan los futuros oficiales y suboficiales del ejército español. Barcelona: CIDOB.

Martínez-García, I., Padilla-Carmona, M. T., and y Suárez-Ortega, M. (2019). Aplicación de la metodología Delphi a la identificación de factores de éxito en el emprendimiento. Rev. de Investig. Educ. 37, 129–146. doi: 10.6018/rie.37.1.320911

Meumann, M., and O’Neil, M. J. (2020). The Case for Mentorship and Coaching in Military Formations. Queen's University Kingston, ON.

Ministry of Defense (2021). UK regular armed forces continuous attitude survey results 2021. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/987969/Armed_Forces_Continuous_Attitude_Survey_2021_Main_Reportedited.pdf (accessed November 12, 2021).

Moliner, J. A. (2020). La ética militar y su importancia para el militar profesional. [dissertation thesis] [Madrid]: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia.

Montaño, J. M. G., Domínguez, M. T. G., and Amador, M. A. N. (2005). ¿Es posible medir la moral?: el potencial psicológico: un modelo operativo que intenta explicar esa compleja realidad. Madrid: Instituto Universitario General Gutiérrez Mellado de Investigación sobre la Paz, la Seguridad y la Defensa (UNED).

Murray, E. D., Berkowitz, M. W., and Lerner, R. M. (2019). Leading with and for character: the implications of character education practices for military leadership. J. Character Leadersh. Dev. 20, 287–309. doi: 10.1080/2194587X.2019.1669464

Nayak, A., and Pandey, M. (2021). A study on moderating role of family-friendly policies in work–life balance. J. Fam. Issues 1–24. doi: 10.1177/0192513X211030037

Nazri, M., and Rudi, M. (2019). Military leadership: a systematic literature review of current research. Int. J. Bus. Manage. 3, 1–15. doi: 10.26666/rmp.ijbm.2019.1.2

Nilsson, N. (2021). Mission command in a modern military context. J. Baltic Security 7, 5–15. doi: 10.2478/jobs-2021-0001

Nylander, E., and Fejes, A. (2023). Lifelong Learning Research: The Themes of the Territory. Third International Handbook of Lifelong Learning. Springer Nature. Berlin

Örtenblad, A. (Ed.). (2019). The Oxford handbook of the learning organization. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Pires, P. P., Pinto, G. H., Souza, M. A., Macambira, M. O., and Figueira, G. L. (2021). Career adaptability, engagement and job satisfaction: a psychological network in the military education context. RAM. Rev. de Administração Mackenzie 22, 1–28. doi: 10.1590/1678-6971/eRAMG210114

Robinson, G. F. (2021). An Analysis of Gender Differences in Leadership Style and their Influence on Organizational Effectiveness in the us Air Force. [dissertation thesis] [California]: Trident University International.

Scales, R. H. (2009). Clausewitz and world war IV. Mil. Psychol. 21, S23–S35. doi: 10.1080/08995600802554573

Shamir, B., and Ben-Ari, E. (2000). Challenges of military leadership in changing armies. J. Political Mil. Sociol. 28, 43–59. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45294263

Shamir, B., Goldberg-Weill, N., Breinin, E., Zakay, E., and Popper, M. (2000). Differences in company leadership between infantry and armor units in the Israel defense forces. Mil. Psychol. 12, 51–72. doi: 10.1207/S15327876MP1201_3

Skomorovsky, A., Norris, D., Martynova, E., McLaughlin, K. J., and Wan, C. (2019). Work–family conflict and parental strain among Canadian Armed Forces single mothers: the role of coping. J. Mil. Veteran. Fam. Health 5, 93–104. doi: 10.3138/jmvfh.2017-0033

Stothard, C., and Drobnjak, M. (2021). Improving team learning in military teams: learning-oriented leadership and psychological equality. Learn. Organ. 28, 242–256. doi: 10.1108/TLO-12-2019-0174

Trehan, D., and Soni, S. (2021). Is all lost or a lot is still recoverable? A case of 21st century Indian military organizational culture. J. Contemp. Bus. Govern. 27, 1115–1126. doi: 10.47750/CIBG.2021.27.03.152

Tritten, J. J., and Keithly, D. M. (1995). A charismatic dimension of military leadership? Naval Doctrine Command, Norfolk VA. Available at: (https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA294982.pdf).

Vest, B. M., Cercone Heavey, S., Homish, D. L., and Homish, G. G. (2017). Marital satisfaction, family support, and pre-deployment resiliency factors related to mental health outcomes for reserve and National Guard Soldiers. Mil. Behav. Health 5, 313–323. doi: 10.1080/21635781.2017.1343694

Vogel, B., Reichard, R. J., Batistič, S., and Černe, M. (2021). A bibliometric review of the leadership development field: how we got here, where we are, and where we are headed. Leadersh. Q. 32:101381. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101381

Warner, C. H., Appenzeller, G. N., Mullen, K., Warner, C. M., and Grieger, T. (2008). Soldier attitudes toward mental health screening and seeking care upon return from combat. Mil. Med. 173, 563–569. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.173.6.563

Werber, L. (2021). Talent Management for U.S. Department of Defense Knowledge Workers: What does RAND Corporation Research Tell Us? California: RAND Corporation.

Wingerden, J. V., and Poell, R. F. (2017). Employees’ perceived opportunities to craft and in-role performance: the mediating role of job crafting and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 8:1876. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01876

Wong, L., Bliese, P., and McGurk, D. (2003). Military leadership: a context specific review. Leadersh. Q. 14, 657–692. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.08.001

Yammarino, F. J., Mumford, M. D., Connelly, M. S., and Dionne, S. D. (2010). Leadership and team dynamics for dangerous military contexts. Mil. Psychol. 22, S15–S41. doi: 10.1080/08995601003644221

Keywords: leadership, military leader, leadership development, leadership perceptions, lifelong learning

Citation: Díez F, Martínez-Morán PC and Aurrekoetxea-Casaus M (2023) The learning process to become a military leader: born, background and lifelong learning. Front. Educ. 8:1140905. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1140905

Received: 09 January 2023; Accepted: 27 July 2023;

Published: 08 August 2023.

Edited by:

Rose Baker, University of North Texas, United StatesReviewed by:

Vilma Zydziunaite, Vytautas Magnus University, LithuaniaCopyright © 2023 Díez, Martínez-Morán and Aurrekoetxea-Casaus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fernando Díez, ZmRpZXpAZGV1c3RvLmVz

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.