95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 14 July 2023

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1139648

This study aims to delineate the intellectual and conceptual architecture of social justice leadership (SJL) research in education by reviewing the strategic themes that emerged during its scientific evolution. The study combines bibliometric performance and science mapping analysis of 135 articles on “SJL in education” retrieved from the Scopus database. SciMAT software (version 1.1.04) was used for the study since it allows for sequential analysis. Our analysis comprised three periods: Period 1 (2003–2012), Period 2 (2013–2017), and Period 3 (2018–2022). Studies during the first period mostly centered around transformative leadership, social justice, and equity themes, while the research focus during the second period moved toward the roles of principals in enabling justice. During the third period, the analysis revealed more variety in the themes addressed by scholars. Instructional leadership roles of principals and the outcomes of social justice leadership, such as equity and well-being for different groups vulnerable to injustices, were the most prominent themes addressed during the last period. The study’s findings enable us to reflect on this research field’s well-or underdeveloped aspects. They would help guide research interest into the under-investigated or emerging themes of SJL, which would eventually increase our understanding of the practice and outcomes of SJL in the educational context.

The concept of social justice is familiar in educational literature, with almost 50 years of history. Earlier articulations of social justice mainly focused on sexism and racism (i.e., equity for women and racial minorities in education), particularly with pedagogical and curricular concerns (Lewis, 2016). However, over the past decade, the interest of educational scholars and practitioners in social justice has increased (Goldfarb and Grinberg, 2002; Shields, 2004; Marshall and Olivia, 2006; Furman, 2012; Berkovich, 2014; Canlı and Demirtaş, 2022; Rissanen et al., 2023), and the content of social justice has extended to inequities resulting from poverty, socioeconomic status, cultural diversity, ethnicity, disability, and sexual orientation (Jean-Marie et al., 2009). Starting from the early 21st century, the role of educational leaders in addressing and eliminating these inequitable practices has begun to garner increasing attention (Theoharis, 2007; Shields, 2010; Bogotch, 2013; Berkovich, 2014). Some scholars have even boldly asserted that “educational leadership and social justice are, and must be, inextricably interconnected” (Bogotch and Shields, 2014, p. 10), and “individuals who are unable or unwilling to purposefully, knowledgeably, and courageously work for social justice in education should not be given the privilege of working as a school or district leader” (Marshall and Olivia, 2006, p. 308).

The emphasis on social justice leadership (SJL) has increased internationally (Furman, 2012; Forde and Torrance, 2017), a trend which may be explained from several perspectives. First and foremost, research has shown that inequalities faced by marginalized groups or minorities not only damage school efficiency and effectiveness through harming social solidarity in schools, reducing motivation, and increasing disciplinary problems and drop-out rates but also harm the socioemotional growth and well-being of these students (Karpinski and Lugg, 2006; Berkovich, 2014; Wang, 2018; Moral Santaella, 2022). In the long run, inequities suspend schools from their contemporary mission of “facilitating the harmonious development of a diverse society” (Lumby and Heystek, 2012, p. 5).

Furthermore, under the influence of globalism, societies have become more culturally and ethnically diverse, with a growing number of minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. This has resulted in socioeconomically, culturally, and ethnically diverse student populations and commissioned schools to prepare students for participation in a more multicultural, multiethnic, multinational, and multi-religious society (Jean-Marie et al., 2009; Rissanen et al., 2023). The global education reform policies introduced in line with neoliberal agendas have also focused on system and research interest in social justice (King et al., 2021). On the one hand, the politics of neoliberalism use education to perpetuate societal inequities by supporting the dominance of elite groups over the marginalized and urging people always to strengthen their position (Berkovich, 2014). On the other hand, the accountability and audit pressures of neoliberalism have attracted the attention of policymakers and practitioners to increased inequities in schools, especially concerning academic achievement gaps in high-stakes exams (Shields, 2004; Jean-Marie et al., 2009; Lewis, 2016). In terms of testing, international comparative testing regimes such as PISA have also led to national and international performance comparisons of schools, and the gaps between high and low-achieving students (mostly from disadvantaged groups) have become a significant concern (Blackmore, 2009; Forde and Torrance, 2017). Hence, ensuring social justice in educational policies and practice through school leadership is now more crucial than ever (Shields, 2010; Bogotch, 2013; Oplatka, 2014; Canlı and Demirtaş, 2022).

Social justice leadership discourse has advanced in the literature since the turn of the 21st century, and many scholars have addressed the means and challenges of alleviating and sustaining social justice in schools (DeMatthews et al., 2015). As Lewis (2016) asserted, much has changed and evolved concerning the conceptual understanding of equity and inclusion in schools and the structural factors that shape our notions of social justice. In this regard, a comparative analysis of the evolving SJL knowledge through identifying conceptual and topical trends in SJL research would help broaden our conception of the intellectual quest into “SJL in education.” Thus, the current study conducted a quantitative longitudinal review of the SJL in the educational literature by combining bibliometric and science mapping analysis, which aimed to help reveal how the intellectual structure of “SJL in education” has evolved as a research field. More specifically, the study aimed to address the following research questions:

RQ1: What are scholarship’s volume and growth trajectory on “SJL in education”?

RQ2: What journals and authors have evidenced the most significant citation impact on “SJL in education”?

RQ3: What is the intellectual structure and evolution of the knowledge base of “SJL in education”?

RQ4: What topical foci have attracted the most significant attention from scholars on “SJL in education”?

Although there is no broad consensus on what “social justice” means in educational literature, it is often used as an umbrella term to refer to (in)equity, (in)equality, (un)equal opportunity, diversity, and inclusion (Blackmore, 2009; Berkovich, 2014). In brief, the concept of social justice addresses creating equitable conditions for all students regardless of their capabilities/disabilities, different racial, cultural or ethnic backgrounds, and/or spiritual and sexual orientations (Jean-Marie et al., 2009). In a socially just system of education, as elucidated by Shields (2004), all students are provided with equity of access to an inclusive and academically challenging curriculum that can open the doors to studying at the university level or seeking employment in a desirable workplace, as well as promoting equitable sustainability and outcomes of schooling which can, in turn, “equip all children from all groups to leave school fully prepared to lead productive, successful, fulfilling lives” (p. 124).

From the leadership perspective, a common understanding is that social justice focuses on the “inequity experiences of marginalized groups concerning educational opportunities and outcomes” (Furman, 2012, p. 194) and refers to the “exercise of altering the [institutional and organizational] arrangements by actively engaging in reclaiming, appropriating, sustaining, and advancing inherent human rights of equity, equality, and fairness in social, economic, educational, and personal dimensions” (Goldfarb and Grinberg, 2002, p. 162). In the same vein, SJL involves a strong interest in interrogating and identifying conditions that create or perpetuate inequalities and marginalization and a gallant attempt to substitute these inequities with equitable and democratic practices (Theoharis, 2007; DeMatthews, 2014; Sarid, 2021). SJL is not only about the recognition and awareness of all kinds of inequities but also involves activism to promote equity-oriented change in social structures and practices (Berkovich, 2014; Forde and Torrance, 2017; Flores and Bagwell, 2021).

Within this dual perspective of SJL, scholars have defined some exemplary personal/professional characteristics or acts associated with school leaders and elucidated the activism inherent in this type of leadership (Theoharis, 2007; DeMatthews, 2014). On the one hand, leaders’ beliefs, experiences, values, and worldviews (Ingle et al., 2011); their cultural or ethnic identities (Santamaria and Jean-Marie, 2014); their communication skills, emotional awareness, and their ability to build relationships and to foster collaboration among diverse groups (DeMatthews, 2014); their acumen and capacity to enact principled and democratic decision making (DeMatthews et al., 2015); their ability to see beyond the parts to the whole with a systems-level perspective (Wang, 2018); and their will to identify their own biases, prejudices, and deficit beliefs through continuous self-reflection (Furman, 2012; Lewis, 2016) are considered to be crucial for socially just leadership practices. On the other hand, social justice leaders are portrayed as activists because they are deemed to courageously challenge the status quo and raise critical consciousness of discriminating and marginalizing norms and practices to create profound and structural social change to eventually elude inequities of any kind (Furman, 2012; Hill-Berry, 2019; Sarid, 2021). In their attempt to transform persistent conventional inequities, these leaders also engage in solid advocacy work through maximizing resources, enhancing staff capacity, mediating conflicts, raising the awareness of others into the deficit beliefs building these injustices, and initiating a community-wide intervention to transform exploitative and marginalizing norms in and out of schools (Jean-Marie et al., 2009; Lewis, 2016). As such, SJL necessitates persistence, commitment, and courage (Furman, 2012) because it entails “an ongoing struggle complicated by personal, cultural, societal, and organizational dimensions associated with the leader, school, community, and society as a whole” (DeMatthews et al., 2015, p. 19).

Scholars contend that educational leadership literature needs a solid theory of social justice. Thus, theories from social sciences could provide the intellectual scaffold for both research and practice of leadership (Young and Lopez, 2005; North, 2006). This section encapsulates some theories prominently used in the current SJL literature.

Lewis (2016) asserted that SJL as a modern concept is associated with ideas of distributive justice and societal reorganization, and theories of social justice are built upon three aspects of justice: distributive, cultural, and associational (Furman, 2012; DeMatthews et al., 2015). In brief, distributive justice is the equitable distribution of goods, rights, and societal advantages (Rawls, 2009). Cultural justice refers to recognizing cultural diversity and lacking cultural dominance or marginalization (Fraser, 1997). Associational justice, conversely, concerns ensuring marginalized groups’ participation in decisions that shape their lives (Taysum and Gunter, 2008). Within this framework, SJL is about ensuring that no school is confined to under-resourced, understaffed, undesirable, and inadequate conditions (distributive justice), eliminating deficit thinking, othering, stereotyping, disrespecting or degrading of any cultural group and fostering a culture-friendly educational atmosphere (cultural justice), and a strengthening culture of democracy that enables full participation of everyone where decisions are to be made (associational justice).

Another prevalent theory addressed in SJL literature is conceptualization of social justice of Fraser (1997): redistribution and recognition (Blackmore, 2009; Berkovich, 2014; Wang, 2016). Redistribution concerns eliminating the socioeconomic exploitation, marginalization, and deprivation of any group, and achieving socially just distribution of economic benefits, while recognition refers to eliminating cultural domination, non-recognition, or/and misrecognition; thus, “designat[ing] an ideal reciprocal relation between subjects in which each sees the other as its equal and also as separate from it” (Fraser, 1997, p. 10).

Scholars have also investigated SJL within the framework of socio-ecological theory (Berkovich, 2014; Zhang et al., 2018; King et al., 2021). The theory defines social life based on the interactions between individuals and multiple subsystems (immediate, broader, and macro-social structures) in society (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Within this framework, SJL is emphasized to be “tightly intertwined in the cultural, historical and personal contexts of the leader and the school” (Arar and Oplatka, 2016, p. 71). Thus, understanding SJL necessitates a holistic view that comprises the personal (e.g., beliefs, identity, and background), school (e.g., nature of relationships, climate, and a culture of trust), and community-level factors (e.g., politics and culture; Zhang et al., 2018).

Critical theory, which suggests that society is already organized unjustly and any attempt should benefit the marginalized, is frequently addressed in social justice literature and considered a sound theoretical framework for understanding SJL in schools (Theoharis, 2007). In the same vein, critical race theory, queer theory, and feminist theory, each developed from critical theory, are also suggested to offer a valuable lens to strengthen the investigation and practice of SJL (Young and Lopez, 2005; Marshall and Olivia, 2006; Jean-Marie et al., 2009).

In this study, we combined performance analysis and scientific mapping methods to determine the bibliometric performance of the “SJL in education” research field, to reflect on its dynamic and structural features, and to comprehensively present the cognitive architecture of this academic field (Cobo et al., 2011; MacFadden et al., 2021).

Online databases such as Clarivate’s Web of Science (WoS) and Elsevier’s Scopus are frequently used as data sources in bibliometric studies. Scopus is considered an optimum database for bibliometrics (Cañadas et al., 2021). Mongeon and Paul-Hus (2016) stated that almost all of the documents listed in the WoS database are also indexed in the Scopus database and that Scopus lists more journals than WoS. The broader coverage of journals reduces the risk of missing documents published that would be valuable to the analysis. For this reason, we used the Scopus database to search and extract data in the current study. During data collection/analysis, we followed a three-step procedure of searching and defining data, extracting and cleaning data, and subsequently analyzing the retrieved data (Hallinger and Kulophas, 2019). The selection process of the 135 articles in the current study is also reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA) guidance (Moher et al., 2009) in Figure 1.

The following inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to select publications for analysis (Table 1):

In line with the determined criteria, a keyword search was performed against the Scopus database on August 09, 2022, using the following keyword string:

TITLE (“social justice” OR “social justice leader*” OR “social justice leadership” OR “justice leader*” OR “justice leadership”) AND TITLE (“educational leadership” OR “principal*” OR “school principal*” OR “school administrator*” OR “school administration” OR “leader*” OR “school manager*” OR “school management” OR “head*” OR “headship” OR “headteacher*” OR “head teacher*” OR “school leader*” OR “school leadership” OR “supervisor*” OR “inspector*” OR “school*” OR “teacher*” OR “student*” OR “learner*” OR “pupil*” OR “classroom*” OR “learning” OR “teaching” OR “education*” OR “higher education” OR “secondary education” OR “primary education” OR “preschool education” OR “pre-school education” OR “K-12 education”).

Keywords were selected after an in-depth review of the relevant literature and the approval of two field experts. The initial search yielded 1,485 documents, of which 288 remained after excluding 1,197 documents failing to meet the selection criteria. Then, the titles of the 288 articles were examined one by one by the researchers, and 94 documents whose titles were not directly related to “SJL in education” were excluded from the dataset. Next, the researchers read the abstracts of the remaining 194 articles in detail. At this stage, 65 documents were excluded because they needed to be correctly populated and/or were considered out of scope. Eventually, 129 articles were left for the final analysis. However, six additional articles identified through the references of these articles were identified as being appropriate and were subsequently included. As such, the total number of articles selected for analysis increased from 129 to 135.

After performing a data search on the Scopus database, we transferred the bibliometric data of each selected article (title, author names, keywords, abstract, citations, publication date, journal name, plus other information such as country) onto the Science Mapping Analysis Tool (SciMAT) software (version 1.1.04) and made them eligible for analysis. Using the SciMAT, we manually grouped keywords representing the same concepts, such as leader and leaders, principal and principals, etc., to improve the thematic analysis’s quality (Cobo et al., 2012; López-Robles et al., 2021).

In line with our research purpose, we used a particular methodology to evaluate the bibliometric performance, conceptual structure, and thematic evolution of the “SJL in education” field based on the 135 most relevant articles selected for the study. First, a bibliometric performance analysis was conducted to determine the temporal distribution of related publications, the accumulated number of publications, and the average citations per article (Zupic and Čater, 2015). In addition, science mapping analysis was performed using the SciMAT software tool (Cobo et al., 2012) to analyze the conceptual structure and thematic evolution of the “SJL in education” research field. Science mapping analysis not only helps to reveal the conceptual structure, development, and research trajectories of a particular field but also aims to reveal the structural and dynamic aspects of this scientific research (Cobo et al., 2011; Martínez et al., 2015). SciMAT combines scientific mapping and bibliometric performance analysis techniques to examine a field, identify, describe, and visualize specific topics and themes, as well as show their thematic evolution. SciMAT is a potent tool for analyzing and monitoring a research field’s evolution over sequential periods (Garfield, 1994; Cobo et al., 2012; Batagelj and Cerinšek, 2013; Chen, 2017). In the current study, SciMAT was used for conceptual science mapping analysis following these four steps (Callon et al., 1991; Coulter et al., 1998; Cobo et al., 2011, 2012; Martínez et al., 2015; Murgado-Armenteros et al., 2015): (i) Identifying “SJL in education” research topics; (ii) visualization of research themes and thematic network; (iii) identifying thematic areas; and, (iv) performance analysis.

A standardized network of co-occurring keywords was formed using the keywords extracted from the retrieved articles. Later, a clustering algorithm was applied to the normalized network of co-occurring keywords to identify research themes, with closely related keywords comprising each cluster or theme. This phase allowed for identifying and visualizing the conceptual subfields of “SJL in education” as a research field and revealing its thematic evolution.

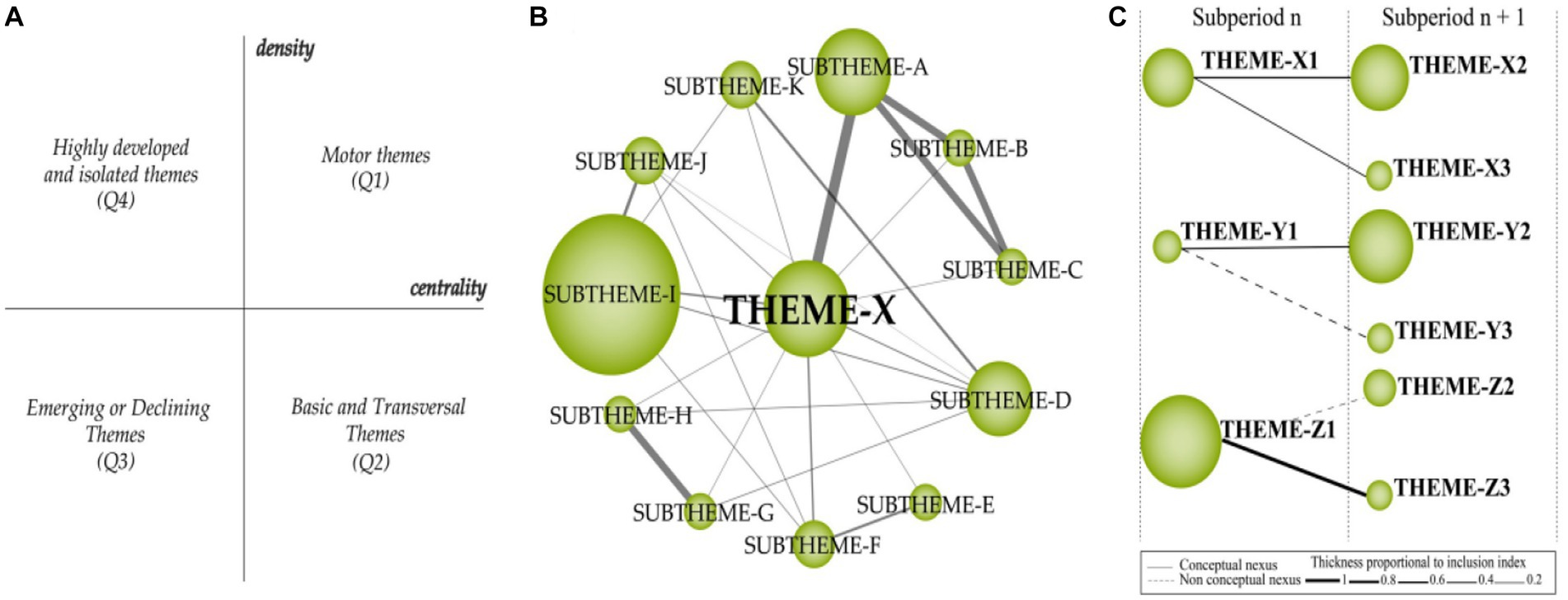

Strategic diagram and thematic network were used as two different tools to create a graphical representation of the identified topics. A clustering algorithm was used in the current study to identify and illustrate the research themes. The themes from the cluster-based analysis were presented in a four-quadrant, two-dimensional strategic diagram based on the centrality (x-axis) and density (y-axis) values. Centrality measures the degree to which a cluster interacts with other clusters or the strength of its relationship. In other words, centrality relates to the external relations of a theme; so, as the relationship of a theme with other themes increases, the themes shift to the right-hand side of the strategic diagram. Centrality is mathematically formulated as “c = 10 x Σekh,” where “k” represents a keyword belonging to any one theme and “h” represents a keyword belonging to another theme. Centrality reveals that a cluster or network is an important crossing point and has a critical role in highlighting and helping to understand the relationship between themes. On the other hand, density measures the internal strength of the relationship, that is, the strength of the relationship between keywords within a theme. Density represents the capacity of themes in a research field to persist and develop over time. In addition, density relates to the internal relations of the themes. Themes with increased relationships among themselves shift upward toward the top of the strategic diagram. Density is mathematically formulated as “d = 100 (Σeij / w),” where “i” and “j” represent the keywords of the theme, and “w” represents the number of keywords in the theme. Using centrality and density values, a research field can be represented in a strategic biaxial diagram separating four categories.

In this regard, the research themes were divided into four groups for a conceptual science mapping analysis based on a network of co-occurring keywords as shown in the strategic diagram in Figure 2A (Cobo et al., 2012): (a) Motor themes (Q1): High centrality and density themes related to the development and structuring of the research field; i.e., they show high-progress and are the most significant themes for that field of research; (b) Basic and transversal themes (Q2): High centrality and low density (themes not that well developed but related to the research field; they still tend to be motor themes due to their high centrality); (c) Emerging or declining themes (Q3): Low centrality and density (themes emerging or already disappeared, which can be determined through in-depth qualitative analysis); and (d) Highly developed and isolated themes (Q4): Low centrality and high density (despite being highly specialized and environmental themes, they may be no longer deemed necessary, or lack the appropriate background due to newly-emerged concepts or technology in the field).

Figure 2. (A) Strategic diagram, (B) thematic network structure, and (C) thematic evolution structure (Cobo et al., 2012).

The thematic network structure presented in Figure 2B shows how strategic themes emerge alongside other subthemes related to the research field. Each thematic network is tagged according to the most important (most central) keyword in the associated theme. Here, the keywords are interconnected, with the volume of the spheres proportional to the number of articles corresponding to each keyword. The size of the circles in the thematic networks depends on the number of publications, whereas the thickness of the lines represents the strength of the relationship.

The thematic evolution map in Figure 2C explores the evolution of research themes, periods, origins, and interrelationships. It is presented as a set of themes developed over different periods. Depending on their interrelationships, a theme may belong to a different thematic area or may not be a continuation of any other theme. Solid lines on the thematic map indicate that the exact keywords as the theme names are shared between the themes; dashed lines indicate that ordinary words are shared apart from the theme labels. The thickness of the lines varies according to the degree of the relationship, while the size of the circles is based on the number of publications.

To analyze the evolution of the “SJL in the education” research field, the raw data were divided into three consecutive periods. An inclusion index was used to explore the conceptual links between themes from the different periods based on the equation: Ii = #(U ∩ V)/min(#U, #V; Börner et al., 2005; Sternitzke and Bergmann, 2009). The thematic evolution map was created by forming conceptual links (common keywords) from the U theme to the V theme. A thematic connection between the U and V themes shows that both themes have common elements and how they have evolved. As the number of common keywords between periodical clusters increases, their evolution becomes more evident.

At this stage, the number of articles, total citations, and different h-index values (Hirsch, 2005; Alonso et al., 2009) were used as bibliometric indicators in order to measure the contribution (scientific impact) of each thematic area that emerged from the analysis to the whole “SJL in education” research field.

López-Robles et al. (2021) suggested that analysis made over different periods saves the data from uniformity and allows for comparative results. Therefore, we evaluated the articles focusing on “SJL in education” over three consecutive periods. The three-time periods were formed based on the number of articles published over the whole analysis period (2003–2022). Due to the fewer publications during the earlier years, Period 1 covered 2003 to 2012, Period 2 was from 2013 to 2017, and Period 3 was from 2018 to 2022.

We conducted a performance-based bibliometric analysis to evaluate the “SJL in education” research field. Since performance analysis is based on bibliometric indicators that measure the global impact of publications, we separately examined the distribution of articles in this field according to the year of publication, the accumulated number of publications, citations per article, most productive/cited authors, and most productive/cited journals (Hirsch, 2005).

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of the 135 articles examined on “SJL in education” by year of publication, the accumulated number of publications, and a graphical representation of the average citations per article.

As Figure 3 illustrates, the interest in SJL within the educational literature has increased gradually according to the periods used in the current study, but with some unstable fluctuations. The number of publications in Period 2 and Period 3 showed a more evident upward trend, with 2021 having the highest number of publications. One reason publications escalated during 2021 may be due to the increased attention that social justice could have become a more significant issue during or since the COVID-19 pandemic and might have exacerbated the prevailing educational inequities for groups of already vulnerable students. On the other hand, many renowned journals published special issues during Period 1, such as Educational Administration Quarterly (2004), International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning (2006), Journal of Educational Administration (2007), Journal of School Leadership (2007), and Teacher Development (2008), which may have garnered additional interest in SJL in the subsequent periods. Figure 3 shows that articles published during Period 1 were the most cited, as expected. Interestingly, though, articles published in 2014 also received considerable numbers of citations when compared to the other years of Period 2.

Table 2 lists the 20 most productive scientists contributing to the “SJL in education” field based on the total number of citations. Within the scope of the 135 articles analyzed, the number of authors that contributed to the articles totaled 222, with some authors also having been involved in more than one of the published studies.

Table 2 shows that DeMatthews contributed to the field with the highest number of articles (n = 7), while Theoharis’ articles received the highest number of citations (n = 663). Brown contributed two highly cited articles, while Capper was one of the most contributing authors to the field, having published four highly cited articles.

The top 20 journals with the highest number of articles on “SJL in education” between 2003 and 2022 are listed in Table 3, based on the total number of articles published.

As Table 3 illustrates, research on “SJL in education” was mostly published in one of the leading journals of the educational administration field; Educational Administration Quarterly. Although the list of most influential journals largely comprises journals with an education/educational management and policy focus, journals from social sciences, counseling, and psychology also showed significant interest in publishing research on “SJL in education.”

The articles obtained from the Scopus database were analyzed with the SciMAT software tool. They presented the main themes and performance measures (i.e., the h-index values, the sum of citations, centrality, and density ranges). In this section, the results of the science mapping analysis performed using SciMAT are reported as (i) structural analysis (thematic analysis) according to periods, (ii) overlapping graph analysis, and (iii) longitudinal analysis (thematic evolution structure).

This period includes 34 articles published between 2003 and 2012. The strategic diagram and performance analysis results are shown in Figure 4, while the thematic network structure is shown in Figure 5.

The data analysis for Period 1 (2003–2012) revealed four main themes. Social-Justice-and-Equity, Leadership, and Transformative-Leadership emerged as the motor themes that contributed the most to the field’s development. This finding indicates that research during this initial period mainly focused on themes from the leadership and social justice literature. The Equity theme, on the other hand, was revealed to be an emerging and/or declining theme. The theme of highest significance during this first period was found to be Social-Justice-and-Equity, which was represented by 10 articles in total.

In order to identify the terms associated with the themes for the first period (2003–2012), cluster networks were examined (see Figure 5). Andragogy, Bigotry, Democratic-Leadership, Educational-Leadership, Educational-Administration, Principal-Preparation, Student-Resilience, and Adult were found to have associations with the Social-Justice-and-Equity theme (1, 0.75), which emerged as one of the motor themes of the period (based on the centrality and density values). The Andragogy, Adult, and Principal-Preparation motor themes reflect that prior studies on SJL focused on developing better leadership training programs to support SJL in schools (Furman, 2012). On the other hand, the Leadership motor theme (0.75, 1) established a strong relationship with Lawyers, Minority-Group, Principals, School-Leadership, Inclusive-Leadership, Environmental-Justice, Racial-Justice, and Emotional-Intelligence subthemes. These subthemes seemingly address the qualities (e.g., Emotional-Intelligence, Inclusive-Leadership) or the targets of leadership (e.g., Environmental-Justice, Racial-Justice, Minority-Group) in terms of creating socially just schools.

Another motor theme associated with Period 1 was Transformative-Leadership (0.5, 0.5), which was found to have strong relationships with the Ethnic-Groups, Leadership-for-Social-Justice, Organizational-Justice, Class, Critical-Social-Theory, Pathologizing-Practice, and Perceived-Organizational-Support subthemes. This finding indicates that transformative leadership research in the “SJL in education” literature centrally addressed these subthemes between 2003 and 2012.

This period included 42 articles published between 2013 and 2017, with the results of the science mapping analysis presented as follows. Figure 6 shows the strategic diagram and performance analysis, while Figure 7 shows the thematic network structure.

Five main themes emerged for Period 2 (2013–2017); among them, the Principals and Social-Justice-and-Equity themes were revealed to be the motor themes. Their strong centrality and high-density values suggested that they were the main themes that contributed to the development of the field during the second period. The Leadership-for-Social-Justice theme, with low centrality and high-density values, emerged as a highly developed and isolated theme. On the other hand, the School-Leadership theme was found to be a relatively weak theme that emerged and/or disappeared within the second period. Educational-Leadership was shown to be a basic and transversal theme related to the research field but needed to be sufficiently emphasized. The theme of highest significance during Period 2 was found to be the principal’s theme, which was represented by 10 articles.

Cluster networks (see Figure 7) were examined to determine the subthemes related to the main themes that emerged during Period 2 (2013–2017). The central theme of Principals (1, 0.8) was strongly associated with Urban-Education, Student-Resilience, Instructional-Leadership, Leadership, Moral-Leadership, Social-Justice-Leadership, Equity, and Emotional-Intelligence subthemes. The solid, thick lines also indicate that Urban-Education, Moral-Leadership, Social-Justice-Leadership, and Emotional-Intelligence also had strong associations. The subthemes seemingly underline the means and outcomes of SJL in schools as practiced by principals, especially in the urban schooling context.

The central theme of Social-Justice-and-Equity (0.8, 0.6) was strongly related to Jewish, Muslim, Head-Teacher, Educational-Administration, Bilingual-Education, Community-Development, Advocates, and Educational-Equity subthemes. The finding reflects that research interest during the second period tended to focus on religion and/or language-based inequalities and emphasize the advocacy role of SJL.

The third period included 59 articles published between 2018 and 2022, and the results of their analysis are presented as follows. The strategic diagram and performance analysis are shown in Figure 8, and the thematic network structure is shown in Figure 9.

The analysis revealed 10 main themes for Period 3 (2018–2022). School-Leadership, Instructional-Leadership, LGBTQ, Well-Being, and Equity were the motor themes with strong centrality and high-density values. Thus, these themes contributed the most to developing the “SJL in education” field of research. The Leadership-for-Social-Justice theme emerged as highly developed and isolated, supported by its low centrality and high-density values. Social-Justice-Leadership, Diversity, and Educational-Leadership were each found to be emerging/declining themes that were relatively weak and either newly emerged or had disappeared from the research field during Period 3. Collective-Transformative-Agency was revealed to be a basic and transversal theme, indicating that while the theme was relevant to the research field, it needed to be more adequately developed. This quadrant displays transverse and general basic themes having high centrality and low density. The most significant central theme during Period 3 was the LGBTQ theme, represented by 13 articles.

Cluster networks (see Figure 9) were examined to determine which subthemes related to the main themes that emerged during Period 3 (2018–2022). The central theme of LGBTQ (0.8, 1) was revealed to be strongly related to Cooperative-Behavior, Criminal-Law, Leadership, Justice, Social-Justice-and-Equity, Lawyer, COVID-19, and Cooperation subthemes.

The central theme of Instructional-Leadership (0.9, 0.9) was found to have strong relationships with Preparation, Priority, Goals-of-Schooling, Commitment, First-Generation, Graduation, Matriculation, and Neoliberalism subthemes. Many subthemes address access to or successful attainment in higher education (i.e., Preparation, First-Generation, Graduation, and Matriculation). In other words, the scholars of SJL research have addressed instructional leadership to achieve social justice in accessing and completing higher education, which may determine prospects for a better life. In addition, the goals of schooling (maybe the academic and social goals) under the influence of neoliberalism are reconsidered with an SJL perspective during Period 2.

The central theme of School-Leadership (1, 0.8) was strongly associated with Citizens, College-Curriculum, Urban-Education, Talents, Advocates, Andragogy, Bridge-Partnerships, and Budget-Allocation subthemes.

The central theme of Well-Being (0.7, 0.6) was found to have strong relationships with Mental-Health, Social-Determinants-of-Health, Relational-Leadership, Minority-Group, Academic-Optimism, Anti-Racism, Food-Insecurity, and Health-Care-Policy subthemes, which seemingly address both the psychological and physiological aspects of well-being as an outcome of social (in)justices. The central theme of Equity (0.6, 0.7), on the other hand, was revealed to have strong relationships with Stakeholders, Gender, Bigotry, Marginalized, People-Oriented-Approach, Reform, Remedial-Courses, and Revolutionize subthemes during Period 3.

The overlapping map shows the keywords for each period and the newly appeared, lost, or reused keywords during the study’s three consecutive periods (Salazar-Concha et al., 2021). The overlapping map illustrated in Figure 10A shows that a total of 37 terms emerged for Period 1 and that while 15 of these did not exist in the subsequent period, a total of 22 terms also existed. For Period 2, on the other hand, a total of 48 terms emerged, of which 34 were also used in the following period and 14 were not. As for Period 3, 83 terms emerged in total. While the number of terms used for the first time in Period 2 was 26, this total was 49 in Period 3. The keywords increased from 37 in Period 1 to 83 in Period 3, indicating a significant increase in articles published. This cumulative keyword number increase reveals that the “SJL in education” research field has been diversified systematically. In addition, the increased number of words added during each period reveals that the field is continuing to develop, while the growing number of disjointed terms reveals that the terms used in this field of research are constantly being updated.

The longitudinal thematic evolution map (see Figure 10B) illustrates the development pattern in the knowledge base and the relationships between topics that formed the focus of “SJL in education” research over the three consecutive periods of the current study. While the size of the spheres in the longitudinal map indicates the number of publications, the thickness of the lines connecting the spheres indicates the strength of correlation between the themes within the periods (Cobo et al., 2012; Murgado-Armenteros et al., 2015). The thematic fields shown in this map reveal the main themes and emerging research fields covered by “SJL in education” research.

The longitudinal map illustrates that four themes emerged during Period 1 (2003–2012), constituting 25.19% of the published articles. Among these themes, Social-Justice-and-Equity continued to exist in Period 2. It was determined that the Leadership theme was exchanged with School-Leadership and Principals themes in Period 2. In addition, the Transformative-Leadership theme was observed to be exchanged for the Leadership-for-Social-Justice, School-Leadership, and Educational-Leadership themes in Period 2. However, the Equity theme was found to be exchanged by Principals, School-Leadership, and Educational-Leadership themes in Period 2.

Five themes emerged during the second period (2013–2017), covering 31.11% of the articles reviewed. Among these themes, Educational-Leadership, School-Leadership, and Leadership-for-Social-Justice continued to exist in Period 3. The Social-Justice-and-Equity theme was found to have merged with the LGBTQ, School-Leadership, and Collective-Transformative-Agency themes. In addition, the principal’s theme was exchanged with the LGBTQ, School-Leadership, Instructional-Leadership, Social-Justice-Leadership, Equity, and Educational-Leadership themes.

Ten main themes emerged in Period 3 (2018–2022), which covers 43.70% of the articles examined. Among these themes, Educational-Leadership, School-Leadership, and Leadership-for-Social-Justice were themes carried forward from Period 2, while seven appeared for the first time in Period 3 (LGBTQ, School-Leadership, Instructional-Leadership, Social-Justice-Leadership, Well-Being, Diversity, and Collective-Transformative-Agency). The Equity theme, which had appeared in Period 1 and interestingly disappeared in Period 2, later reappeared during Period 3. The Well-Being theme, which emerged in Period 3, was not found to have established any relationships with themes from the two previous periods.

Combining bibliometric and science mapping analysis, the present study delineated the intellectual and conceptual architecture of the SJL field by exhibiting the strategic themes that emerged during its scientific evolution. This quantitative longitudinal review suggests significant implications for the future investigation and practice of SJL in an educational context.

It was evident that SJL has incrementally garnered research interest in educational literature over the past two decades. This research field’s thematic evolution and conceptual architecture were analyzed in three consecutive periods to better observe the changing scope and trends. The featuring themes and subthemes, as well as the periodical evolution of these themes, are elaborated on and discussed in light of existing literature.

The results of the science mapping analysis showed that leadership, transformative leadership, social justice, and equity themes were featured for the first analysis period. Among these themes, transformative leadership and social justice/equity were significant for driving research during this period. As expected, the research at this initial developmental stage was building upon leadership and social justice literature, so the emergence of social justice and leadership as motor themes was not surprising. The fact that “social justice” and “equity” were combined as a single theme while “equity” got weaker attention might indicate that social justice and equity were held as two same constructs by the researchers and were used interchangeably or altogether rather than addressing equity alone. Looking into the definitions of SJL (as given earlier) alone could justify this claim. As for the transformative leadership theme, our finding supports Shields (2004) assertion that “perhaps the most prevalent theme in the literature is that social justice leaders are proactive change agents, engaged in “transformative leadership” (p. 195). Transformative leadership, “characterized by its activist agenda and its overriding commitment to social justice, equality and a democratic society” (Van Oord, 2013, p. 422), could be a suitable intellectual scaffold or a touchstone for SJL (Bogotch and Reyes-Guerra, 2014; Wang, 2018) since SJL is defined as an agentic, action-oriented, and activist endeavor toward realizing justice for all, and a challenging attempt to realize a profound change in the mindsets and practices of educational stakeholders concerning inequalities of all kinds (Lewis, 2016).

A closer scrutiny of the motor themes from the first period indicates that transformative leadership was also held with perceived organizational support, critical social theory, and pathologizing educational practices. Research on SJL as a transformative act was associated with the perceived valuing and caring aspect of leadership that could nourish the sense of belonging and collective responsibility for the well-being of everyone (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002; Wang, 2018) while using critical social theory as a theoretical lens. The theory had already become prominent in educational literature through the works of scholars such as Freire. It addressed the significance of building a humanist pedagogy that provides equal opportunity and power to access quality education (Benson et al., 2013). Concerning this, the critical social theory was seemingly taken up by researchers to investigate leadership acts for achieving equity for everyone regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or other forms of difference. As for the pathologizing sub-theme, the following assertions of Shields (2004) might have been influential:

“…transformative educational leaders may foster the academic success of all children through engaging in moral dialog that facilitates the development of strong relationships, supplants pathologizing silences, challenges existing beliefs and practices, and grounds educational leadership in some criteria for social justice” (p. 109).

Shields (2004) suggests that pathologizing occurs due to the deficit thinking that differences result from the lived experiences of the marginalized and, thus, are abnormal and unacceptable within the school’s boundaries. This pathologizing approach could show itself through silencing the marginalized and discriminatory language used in policy statements or practices and thus possesses a significant barrier to achieving social justice.

The prominent themes during the second period were “principal,” “social justice,” and “equity,” while “school” and “educational leadership” themes were weakening. One particular reason for this result could be that principals were considered to play a vital role in enacting social justice in schools (Wang, 2016) and have “a critical position to move initiatives forward or to kill them off, quickly through actions or slowly through neglect” (Murphy et al., 2009, p. 181). Hence, principals are considered positionally powerful and morally responsible for fostering equitable practices and outcomes for all students regardless of race, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation (DeMatthews et al., 2015; Shaked, 2020). As such, several studies investigated the acts and characteristics of principals with social justice orientations (e.g., Jansen, 2006; Kose, 2007; Theoharis, 2007), and research interest in the second period moved from broader concepts of school or educational leadership to a narrower scope—the daily operations of principals concerning social justice.

The sub-themes associated with the “principal” theme, such as “moral leadership,” “emotional intelligence,” or “instructional leadership,” also support this interpretation, all of which stand as significant characteristics of effective principals as a leader (Theoharis, 2007; Rigby, 2014). In this period, Zembylas (2010), for instance, investigated the emotional aspects of SJL, answering Jansen’s (2006) call for studies explicitly addressing the emotions of social justice leaders, and found that SJL entails both pleasant and unpleasant emotions, which eventually impacts the leadership practices and outcomes.

Rigby (2014), on the other hand, defined social justice as the third logic of instructional leadership and underlined the significance of instructional leadership in leveraging the academic achievement of all students and promoting diverse needs in heterogeneous classrooms. Shaked (2020) later confirmed that SJL had parallels with instructional leadership in that they both aimed to support all students’ academic achievement and raise them as resourceful citizens. Principals practice both types of leadership when they “continuously examine whether …student learning is equitable for all student groups …and encourage teachers to critically examine their practice for possible bias regarding race, class, and gender” (Kose, 2007, p. 279). In the same vein, scholars often emphasized the “moral” aspect of SJL and defined it as a moral use of power to foster equitable school practices and outcomes (Jean-Marie et al., 2009; Bogotch and Reyes-Guerra, 2014). It is often suggested that the moral aspect of leadership must accompany the technical aspect in the field and leadership preparation programs (Furman, 2012). During the second period, these perspectives were all reflected in research focusing on principal leadership.

During the third period of analysis, the theme “instructional leadership” maintained its significance while the themes of school leadership and equity emerged as the motor themes. On the other hand, the main themes from the previous periods, such as “educational leadership,” “transformative leadership,” and “agency,” weakened. One reason why “school leadership” came into prominence while the “principal” theme disappeared could be the changing perspective of leadership from a single person (i.e., the principal) to more distributed or shared forms of leadership (i.e., increased leadership capacity) in schools (Karakose et al., 2022). For one thing, SJL, as the advocacy of equity for all in the face of persistent historical and systemic marginalization, is not an easy task, and leaders often confront challenges, pressures, dilemmas, and resistance, which can genuinely be overcome through collective efforts within and around schools (Theoharis, 2007; DeMatthews, 2014; Parveen et al., 2022; Tülübaş, 2022). For instance, as Wang (2018) underlined, working with like-minded teachers willing to collaborate to enact social justice in every dimension of students’ lives is crucial. Similarly, empowering and including all stakeholders (school administrators, teachers, parents, and students) to collaboratively address social inequities and groom them as critical-minded, transformative agents is essential for effective leadership (Zhang et al., 2018; Yirci et al., 2023). Therefore, a distributive perspective is considered to help develop a better understanding and practice of SJL (DeMatthews, 2014; Hill-Berry, 2019).

The analysis also showed that research interest in LGBTQ issues in educational contexts increased during the third period. One reason why LGBTQ became a driving theme in this period could be the increasing number of studies on the problems of LGBTQ students or staff during the COVID-19 pandemic, considering that the pandemic could make these groups of people more vulnerable to inequality due to their weaker status in many societies (Goldberg, 2020). This was also reflected in our findings, as COVID-19 was one of the significant sub-themes of the LGBTQ theme. Other sub-themes, such as law, lawyer, and justice, might indicate that these studies primarily focused on the legal rights aspect of the issue. On the other hand, scholars noted that studies addressing LGBTQ experience in education and leadership literature are scarce and insufficient to develop a clearer understanding of their lived experiences from social justice perspective (O’Malley and Capper, 2015). However, research indicates that students with LGBTQ identification often feel unsafe and victimized in school, and confront bigotry and verbal and physical assault/harassment (Myers et al., 2020). What is more, intersectionality, referring to the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, is found to be a shared experience among these students, which might bring in more severe injustices (O’Malley and Capper, 2015). These previous findings might have guided SJL research during the third period.

Well-being emerged as another theme that garnered research interest during the third period. The theme, with its various sub-themes such as health care, mental health and food security, anti-racism, relational leadership and minority groups, and academic optimism, suggests that research during this period focused on student well-being from quite a broad perspective. Indeed, both psychical and emotional well-being are expected and targeted outcomes of enabling social justice in schools. This can be achieved by improving all students’ life prospects, socioemotional growth, and academic outcomes (Berkovich, 2014). Considering that social equity has a significant influence on the psychological and physiological well-being of both students and the school-wide community (Gerdin et al., 2021; Polat et al., 2023), this increased research interest is gratifying and likely to contribute to our understanding of how student well-being can be enhanced through SJL.

The evolution of thematic trends across three consecutive periods also deserves some elaboration because the changing scope of these themes delineates the intellectual evolution of social justice leadership research in educational literature and presents a guideline for future research. When viewed holistically, it is evident that the number of themes consistently increased, each theme having a narrower scope. Closer scrutiny of the themes featured during the first period shows that social justice and leadership literature scaffolded the initial development of social justice leadership discourse in research. In the second period, the number of leadership concepts increased such that educational leadership, school leadership, and leadership for justice themes became prominent, while transformative leadership as a concept lost research interest. In the third period, the variety of themes increased, and research began to be guided by new themes such as LGBTQ or well-being. The transformative leadership theme re-emerged with a focus on the collective aspect. Diversity theme, which is, in fact, central to the understanding of social justice, though, was among the newly emerging, weaker themes. These results indicate that the increased understanding of the scope of social justice leadership over time enriched the research field.

On the other hand, the emerging themes in the final period, especially the weaker ones such as diversity, a collective transformative agency of all school-community or even all the stakeholders, await more research interest. Another significant finding is that “social justice leadership” and “leadership for social justice” emerged as two separate themes; the latter emerged as a stand-alone theme in the third period. This indicates conceptual confusion among researchers, which should be addressed in future investigations.

The current study contributed to the growing literature on “SJL in education” by delineating the periodical evolution of its themes and the conceptual architecture of the existing knowledge base. The findings support this research field’s future development by reflecting its well-or under-developed aspects. It would guide research interest into the under-investigated or emerging themes of SJL, which would eventually increase our understanding of the practice and outcomes of SJL in educational contexts. On the other hand, the present study has limitations, as any study is. For one thing, despite the comprehensive coverage of journals and articles on Scopus and the inclusion of a more enormous scope of research thanks to co-word analysis, the study might still have missed some research on “SJL in education.” In addition, this study neither attempts nor presents the review of previous research in conventional terms but solely illustrates its intellectual development and evolution between 2003 and 2022.

TK and TT: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and drafting the manuscript. TK, TT, and SP: analysis and interpretation of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alonso, S., Cabrerizo, F. J., Herrera-Viedma, E., and Herrera, F. (2009). H-index: a review focused in its variants, computation and standardization for different scientific fields. J. Inf. Secur. 3, 273–289. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2009.04.001

Arar, K. H., and Oplatka, I. (2016). Making sense of social justice in education: Jewish and Arab leaders’ perspectives in Israel. Manag. Educ. 30, 66–73. doi: 10.1177/0892020616631409

Batagelj, V., and Cerinšek, M. (2013). On bibliographic networks. Scientometrics 96, 845–864. doi: 10.1007/s11192-012-0940-1

Benson, R., Heagney, M., Crosling, G., and Devos, A. (2013). “Setting the context” in Managing and Supporting Student Diversity in Higher Education: A Casebook. eds. R. Benson and M. Heagney (Cambridge, UK: Chandos Publishing), 1–23.

Berkovich, I. (2014). A socio-ecological framework of social justice leadership in education. J. Educ. Adm. 52, 282–309. doi: 10.1108/JEA-12-2012-0131

Blackmore, J. (2009). Leadership for social justice: a transnational dialogue: international response essay. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 4, 1–10. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234727543_Leadership_for_Social_Justice_A_Transnational_Dialogue (Accessed October 28, 2022)

Bogotch, I. (2013). “Educational theory: the specific case of social justice as an educational leadership construct” in International Handbook of Educational Leadership of Social (in)Justice. eds. I. Bogotch and C. M. Shields (New York: Springer), 51–65.

Bogotch, I., and Reyes-Guerra, D. (2014). Leadership for social justice: social justice pedagogies. Rev. Int. Educ. Just. Soc. 3, 35–38. Available at: http://www.rinace.net/riejs/numeros/vol3-num2/art2_en.htm (Accessed November 12, 2022)

Bogotch, I., and Shields, C. M. (2014). “Introduction: do promises of social justice trump paradigms of educational leadership?” in International Handbook of Educational Leadership of Social (in)Justice. eds. I. Bogotch and C. M. Shields (New York, NY: Springer), 1–12.

Börner, K., Chen, C., and Boyack, K. W. (2005). “Visualizing knowledge domains” in Annual Review of Information Science and Technology: 37. ed. B. Cronin (Leesburg, VA: Society for Information Science and Technology), 179–255.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Callon, M., Courtial, J. P., and Laville, F. (1991). Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: the case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics 22, 155–205. doi: 10.1007/bf02019280

Cañadas, D. C., Perales, A. B., Belmonte, M. D. P. C., Martínez, R. G., and Carreño, T. P. (2021). Kangaroo mother care and skin-to-skin care in preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: a bibliometric analysis. Arch. Pediatr. 29, 90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2021.11.007

Canlı, S., and Demirtaş, H. (2022). The correlation between social justice leadership and student alienation. Educ. Adm. Q. 58, 3–42. doi: 10.1177/0013161X211047213

Chen, C. (2017). Science mapping: a systematic review of the literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2, 1–40. doi: 10.1515/jdis-2017-0006

Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., and Herrera, F. (2011). Science mapping software tools: review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 62, 1382–1402. doi: 10.1002/asi.21525

Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., and Herrera, F. (2012). SciMAT: a new science mapping analysis software tool. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 63, 1609–1630. doi: 10.1002/asi.22688

Coulter, N., Monarch, I., and Konda, S. (1998). Software engineering as seen through its research literature: a study in co-word analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 49, 1206–1223. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(1998)49:13<1206::AID-ASI7>3.0.CO;2-F

DeMatthews, D. (2014). Dimensions of social justice leadership: a critical review of actions, challenges, dilemmas, and opportunities for the inclusion of students with disabilities in US schools. Rev. Int. Educ. Just. Soc. 2014:666738. Available at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/ed_lead_papers/27/ (Accessed October 28, 2022)

DeMatthews, D. E., Mungal, A. S., and Carrola, P. A. (2015). Despite best intentions: a critical analysis of social justice leadership and decision making. Adm. Issues J. 5:3. doi: 10.5929/2015.5.2.4

Flores, C., and Bagwell, J. (2021). Social justice leadership as inclusion: promoting inclusive practices to ensure equity for all. Educ. Lead Adm. Teach. Prog. Dev. 1, 31–43. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1318516 (Accessed October 16, 2022).

Forde, C., and Torrance, D. (2017). Social justice and leadership development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 43, 106–120. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2015.1131733

Fraser, N. (1997). Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition. England, UK: Routledge

Furman, G. (2012). Social justice leadership as praxis: developing capacities through preparation programs. Educ. Adm. Q. 48, 191–229. doi: 10.1177/0013161X11427394

Garfield, E. (1994). Scientography: mapping the tracks of science. Curr. Contents Soc. Behav. Sci. 7, 5–10.

Gerdin, G., Philpot, R., Smith, W., Schenker, K., Mordal Moen, K., Larsson, L. S., et al. (2021). Teaching for student and societal well-being in HPE: nine pedagogies for social justice. Front. Sports Act. Living 3:702922. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.702922

Goldberg, S. B.. (2020). COVID-19 and LGBT Rights. Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2687 (Accessed September 9, 2022).

Goldfarb, K. P., and Grinberg, J. (2002). Leadership for social justice: authentic participation in the case of a community center in Caracas, Venezuela. J. Sch. Leadsh. 12, 157–173. doi: 10.1177/105268460201200204

Hallinger, P., and Kulophas, D. (2019). The evolving knowledge base on leadership and teacher professional learning: a bibliometric analysis of the literature, 1960–2018. Prof. Dev. Educ. 46, 521–540. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1623287

Hill-Berry, N. P. (2019). Expanding leadership capacity toward social justice. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadsh. 4, 720–742. doi: 10.30828/real/2019.3.10

Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 16569–16572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102

Ingle, K., Rutledge, S., and Bishop, J. (2011). Context matters: principals’ sensemaking of teacher hiring and on-the-job performance. J. Educ. Adm. 49, 579–610. doi: 10.1108/09578231111159557

Jansen, J. D. (2006). Leading against the grain: the politics and emotions of leading for social justice in South Africa. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 5:37. doi: 10.1080/15700760500484027

Jean-Marie, G., Normore, A. H., and Brooks, J. S. (2009). Leadership for social justice: preparing 21st century school leaders for a new social order. J. Res. Leadsh. Educ. 4, 1–31. doi: 10.1177/194277510900400102

Karakose, T., Papadakis, S., Tülübaş, T., and Polat, H. (2022). Understanding the intellectual structure and evolution of distributed leadership in schools: a science mapping-based bibliometric analysis. Sustain. For. 14:16779. doi: 10.3390/su142416779

Karpinski, C. F., and Lugg, C. A. (2006). Social justice and educational administration: mutually exclusive? J. Educ. Adm. 44, 278–292. doi: 10.1108/09578230610664869

King, F., Travers, J., and McGowan, J. (2021). The importance of context in social justice leadership: implications for policy and practice. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 10, 1989–2002. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.10.4.1989

Kose, B. W. (2007). Principal leadership for social justice: uncovering the content of teacher professional development. J. Sch. Leadsh. 17, 276–312. doi: 10.1177/105268460701700302

Lewis, K. (2016). Social justice leadership and inclusion: a genealogy. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 48, 324–341. doi: 10.1080/00220620.2016.1210589

López-Robles, J. R., Cobo, M. J., Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M., Martínez-Sánchez, M. A., Gamboa-Rosales, N. K., and Herrera-Viedma, E. (2021). 30th anniversary of applied intelligence: a combination of bibliometrics and thematic analysis using SciMAT. Appl. Intell. 51, 6547–6568. doi: 10.1007/s10489-021-02584-z

Lumby, J., and Heystek, J. (2012). Leadership identity in ethnically diverse schools in South Africa and England. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadsh. 40, 4–20. doi: 10.1177/1741143211420609

MacFadden, I., Santana, M., Vázquez-Cano, E., and López-Meneses, E. (2021). A science mapping analysis of ‘marginality, stigmatization and social cohesion’ in WoS (1963–2019). Qual. Quant. 55, 275–293. doi: 10.1007/s11135-020-01004-7

Marshall, C., and Olivia, M. (2006). Leadership for Social Justice: Making Revolutions in Education. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon

Martínez, M. A., Cobo, M. J., Herrera, M., and Herrera-Viedma, E. (2015). Analyzing the scientific evolution of social work using science mapping. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 25, 257–277. doi: 10.1177/1049731514522101

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group* (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Mongeon, P., and Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of web of science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106, 213–228. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Moral Santaella, C. (2022). Successful school leadership for social justice in Spain. J. Educ. Adm. 60, 72–85. doi: 10.1108/JEA-04-2021-0086

Murgado-Armenteros, E. M., Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M., Torres-Ruiz, F. J., and Cobo, M. J. (2015). Analyzing the conceptual evolution of qualitative marketing research through science mapping analysis. Scientometrics 102, 519–557. doi: 10.1007/s11192-014-1443-z

Murphy, J., Smylie, M., Mayrowetz, D., and Louis, K. S. (2009). The role of the principal in fostering the development of distributed leadership. Sch. Leadsh. Manag. 29, 181–214. doi: 10.1080/13632430902775699

Myers, W., Turanovic, J. J., Lloyd, K. M., and Pratt, T. C. (2020). The victimization of LGBTQ students at school: a meta-analysis. J. Sch. Violence 19, 421–432. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2020.1725530

North, C. E. (2006). More than words? Delving into the substantive meaning(s) of “social justice” in education. Rev. Educ. Res. 76:507. doi: 10.3102/00346543076004507

O’Malley, M. P., and Capper, C. A. (2015). A measure of the quality of educational leadership programs for social justice: integrating LGBTIQ identities into principal preparation. Educ. Adm. Q. 51, 290–330. doi: 10.1177/0013161X14532468

Oplatka, I. (2014). “The place of “social justice” in the field of educational administration: a journals-based historical overview of emergent area of study” in International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Social (in)Justice. eds. I. Bogotch and C. M. Sheilds (New York: Springer), 15–35.

Parveen, K., Tran, P. Q. B., Alghamdi, A. A., Namaziandost, E., Aslam, S., and Xiaowei, T. (2022). Identifying the leadership challenges of K-12 public schools during COVID-19 disruption: a systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 13:875646. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875646

Polat, H., Karakose, T., Ozdemir, T. Y., Tülübaş, T., Yirci, R., and Demirkol, M. (2023). An examination of the relationships between psychological resilience, organizational ostracism, and burnout in K–12 teachers through structural equation modelling. Behav. Sci. 13:164. doi: 10.3390/bs13020164

Rhoades, L., and Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. Appl. Psychol. 87, 698–714. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

Rigby, J. G. (2014). Three logics of instructional leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 50, 610–644. doi: 10.1177/0013161X13509379

Rissanen, I., Kuusisto, E., Timm, S., and Kaukko, M. (2023). Diversity beliefs are associated with orientations to teaching for diversity and social justice: a study among German and Finnish student teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 123:103996. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103996

Salazar-Concha, C., Ficapal-Cusí, P., Boada-Grau, J., and Camacho, L. J. (2021). Analyzing the evolution of technostress: A science mapping approach. Heliyon 7:e06726. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06726

Santamaria, L. J., and Jean-Marie, G. (2014). Cross–cultural dimensions of applied, critical, and transformational leadership: women principals advancing social justice and educational equity. Camb. J. Educ. 44, 333–360. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2014.904276

Sarid, A. (2021). Crossing boundaries: connecting adaptive leadership and social justice leadership for educational contexts. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 1, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2021.1942995

Shaked, H. (2020). Social justice leadership, instructional leadership, and the goals of schooling. J. Educ. Manag. 34, 81–95. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-01-2019-0018

Shields, C. M. (2004). Dialogic leadership for social justice: overcoming pathologies of silence. Educ. Adm. Q. 40, 109–132. doi: 10.1177/0013161X03258963

Shields, C. M. (2010). Transformative leadership: working for equity in diverse contexts. Educ. Adm. Q. 46, 558–589. doi: 10.1177/0013161X10375609

Sternitzke, C., and Bergmann, I. (2009). Similarity measures for document mapping: a comparative study on the level of an individual scientist. Scientometrics 78, 113–130. doi: 10.1007/s11192-007-1961-z

Taysum, A., and Gunter, H. (2008). A critical approach to researching social justice and school leadership in England. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Just. 3, 183–199. doi: 10.1177/1746197908090083

Theoharis, G. (2007). Social justice educational leaders and resistance: toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 43, 221–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X06293717

Tülübaş, T. (2022). The influence of educational employees’ policy alienation on their change cynicism: an investigation in the Turkish public-schooling context. Educ. Proc. Int. J. 11, 40–64. doi: 10.22521/edupij.2022.111.4

Van Oord, L. (2013). Towards transformative leadership in education. Int. J. Leadsh. Educ. Theory Pract. 16, 419–434. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2013.776116

Wang, F. (2016). From redistribution to recognition: how school principals perceive social justice. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 15, 323–342. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2015.1044539

Wang, F. (2018). Social justice leadership-theory and practice: a case of Ontario. Educ. Adm. Q. 54, 470–498. doi: 10.1177/0013161X18761341

Yirci, R., Karakose, T., Kocabas, I., Tülübaş, T., and Papadakis, S. (2023). A bibliometric review of the knowledge base on mentoring for the professional development of school administrators. Sustain. For. 15:3027. doi: 10.3390/su15043027

Young, M., and Lopez, G. R. (2005). “The nature of inquiry in educational leadership” in The Sage Handbook of Educational Leadership: Advances in Theory, Research, and Practice. ed. F. W. English (London, UK: Sage Publications, Inc.), 337–361.

Zembylas, M. (2010). The emotional aspects of leadership for social justice. J. Educ. Adm. 48, 611–625. doi: 10.1108/09578231011067767

Zhang, Y., Goddard, J. T., and Jakubiec, B. A. E. (2018). Social justice leadership in education: a suggested questionnaire. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadsh. 3, 53–86. doi: 10.30828/real/2018.1.3

Keywords: social justice leadership, social justice, leadership, educational leadership, school leadership, science mapping, SciMAT

Citation: Karakose T, Tülübaş T and Papadakis S (2023) The scientific evolution of social justice leadership in education: structural and longitudinal analysis of the existing knowledge base, 2003–2022. Front. Educ. 8:1139648. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1139648

Received: 07 January 2023; Accepted: 26 June 2023;

Published: 14 July 2023.

Edited by:

Cheng Yong Tan, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Keri L. Heitner, Saybrook University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Karakose, Tülübaş and Papadakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stamatios Papadakis, c3RwYXBhZGFraXNAdW9jLmdy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.