94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 14 April 2023

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1130194

This article is part of the Research TopicStories of Abandonment. A Biographical-Narrative Approach to the Academic Dropout in Andalusian Universities. Multicausal Analysis and Proposals for PreventionView all 13 articles

The abandonment of university studies is a problem that affects the balance and correct organization of university systems throughout the world and that has undesirable personal consequences in advanced societies. Dropping out of school has a multidimensional explanation. Among the causes, associated with each other, that originate it, the following factors stand out: psychological, social, economic, psycho-pedagogical, institutional, and didactic. Studying how all these dimensions act and relate to each other in specific cases of people who drop out of Higher Education, helps us to better understand the phenomenon and to develop prevention measures in university institutions. This text presents the results of biographical-narrative research carried out among the student population in a situation of abandonment of the universities of Andalusia that has allowed us to recover 22 stories of abandonment carried out by as many ex-students who were enrolled in any of the nine universities. Andalusians publish in any of the different university degree studies. The biographical texts have been subjected to narrative analysis to achieve personal exemplifications and characterize paradigmatic cases of relationship between the dimensions of the problem, using concept mapping to present the outcomes.

There is great international concern about student retention in higher education institutions, especially in recent years (Foster and Francis, 2020; Casanova et al., 2021), being also a concern for Spain and its universities (Lizarte, 2017a, 2020; Lizarte and Fernández, 2020). Dropout undoubtedly occurs as an interconnected result of social, family, economic and personal factors that students experience when they abandon their university studies, and it needs to be analyzed in terms of the specific geographical and socio-economic contexts. For example, in the context of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), which includes Spain, the opening up of areas of free movement of workers and the transparency and transferability of university degrees is also a factor that has generated a global adaptation of the university system, of its organization in the European Credits Tansfer System (ECTS) credit system, and of the teaching methodologies appropriate for competence-based training (Gijón Puerta and Crisol Moya, 2012; Lizarte and Gijón, 2019).

Early dropout affects all areas of knowledge and all higher education institutions, both public and private. Its influence on the survival of university institutions is also high – especially in private institutions – and it occupies the education policy agendas of developed countries and emerging economies. In the case of the European Union, the so-called 2030 Agenda has set targets related to the reduction of early school leaving, as a generic concept in this case, comprising the population aged 18–24 who are not in or have dropped out of tertiary education.

In terms of university dropouts, the most recent data from the Spanish Ministry of Universities put the dropout rate at between 13 and 11% – for those under 30 years of age – of students at Spanish universities who entered in the 2015/16 academic year. These figures are like those of other OECD countries (Fernández Mellizo, 2022) and represent a strong negative impact on the quality of higher education. This study indicates as factors involved in early drop-out (between the first, second and third year for 4-year degrees), some family or individual factors, academic performance in the first year of the degree, tuition fees, age and socio-economic level. Courses requiring fewer qualifications for entry have higher drop-out rates, and the size of the university also seems to be related to drop-out rates (the larger the university, the higher the drop-out rate).

The international literature has progressively included different views on drop-out in higher education. For this reason, a brief terminological clarification is needed. Having a single definition of “University Desertion” is certainly complicated, as there are different perspectives on abandonment and multiple factors that can influence the decision to drop out. International literature provides various conceptualizations of the phenomenon of student abandonment, including terms such as desertion, retention and persistence (Bäulke et al., 2022) or procastination (Bäulke et al., 2021). These terms are defined differently, although they are sometimes used interchangeably. Generally speaking, “level of retention” refers to the rate at which students remain at a given institution, while “persistence” refers to the completion of a degree and the award of a qualification, irrespective of whether they have changed institution or degree.

Different authors have approached the concept of dropout from different perspectives. For example, González and Uribe (2002) has presented dropouts according to: their duration – temporary dropouts are called partial and permanent dropouts are called total – and according to whether they affect a university or the entire higher education system – institutional dropouts are associated with a single institution, and systemic dropouts when they involve leaving higher education for good. –.

In relation to the point in time at which desertion occurs, the threshold applied varies: from using the time of desertion regardless of when it occurs, to using 3, 2, or 1 year desertion data (Fernández Mellizo, 2022). In this sense, a large part of the studies on dropout have agreed that university dropout occurs mainly in the first year (Corominas Rovira, 2001; Pierella et al., 2020; Wild and Heuling, 2020). The first weeks of school are decisive because there is a higher risk of dropping out due to the multitude of internal and external factors that intervene in the course of adaptation, which is more accentuated among students with lower degrees of self-perception and regulation in psychosocial and academic areas (Lizarte Simón and Gijón Puerta, 2022).

Tinto (1982) defines dropout as a situation faced by a student who aspires to and fails to complete his or her educational project at university, and a dropout as a student who has no academic activity for three consecutive semesters. We will use this concept of “desertion,” focusing on university drop-out in the first and second year of a degree programme.

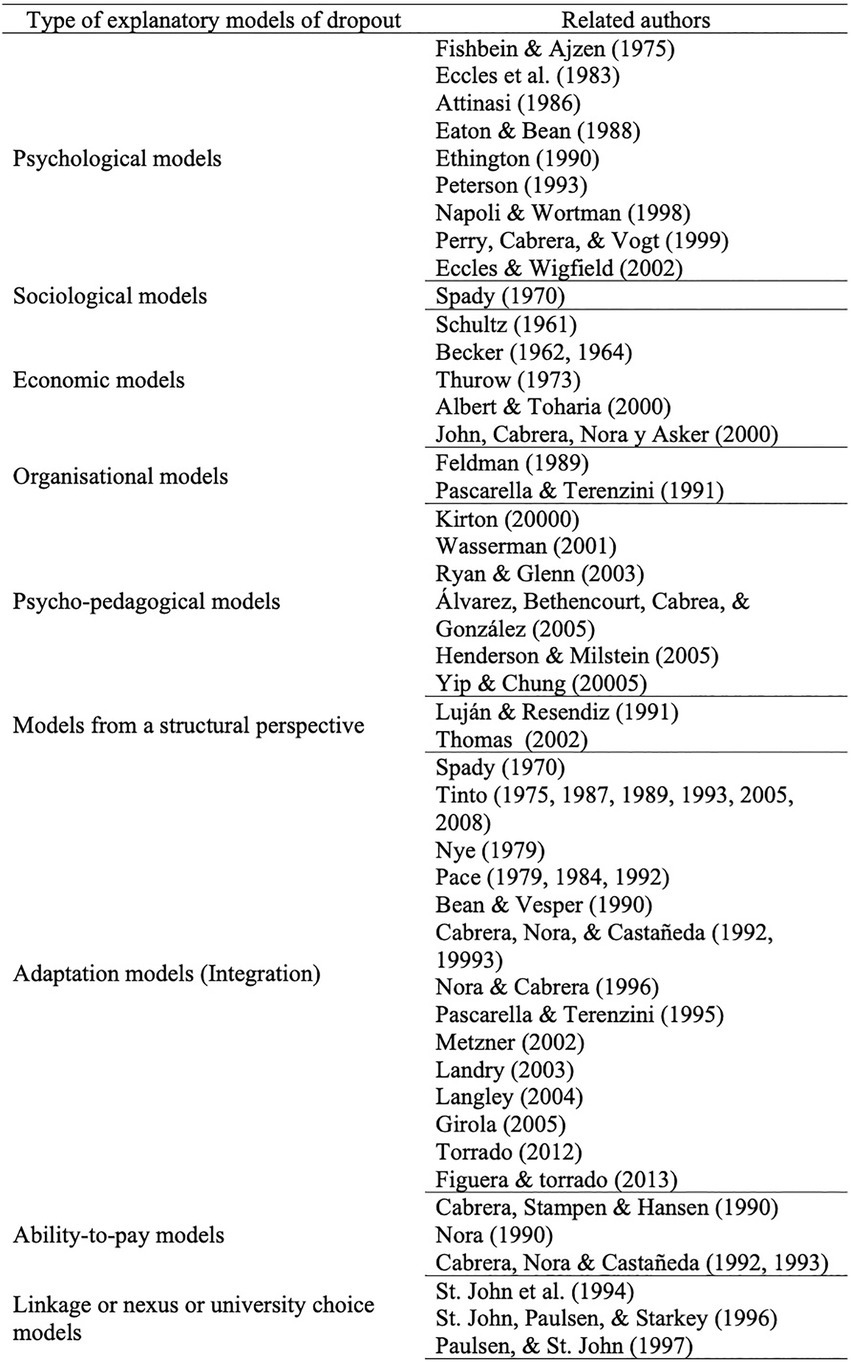

The literature of the last four decades has generated very different explanatory models of the process of student drop-out in higher education. Since the 1960s, a wide variety of models have been developed to try to explain dropout in higher education, which are grouped into different perspectives: psychological, sociological, structural and organizational, adaptation (integration), psycho-pedagogical, structural perspective, adaptation (integration), ability to pay, or link, nexus and university choice (Berlanga et al., 2018; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dimensions grouping the explanatory models of dropout and authors related to each dimension. From Berlanga (2014).

Based on recent reviews of the existing literature on explanatory models of dropout (Figuera Gazo and Torrado Fonseca, 2012; Torrado Fonseca, 2012; Berlanga et al., 2018; Torrado Fonseca and Figuera Gazo, 2019) it is possible to establish the existence of a solid body of doctrine on dropout in higher education. The Student Integration Model developed by Spady (1970), Tinto (2010), and do Nicoletti (2019), and Bean’s Student Attrition Model (Bean and Metzner, 1985) will be the two basic models from which the research on dropout, integration, attrition and dessertion has been developed in higher education, organized around several factors that each model structures differently.

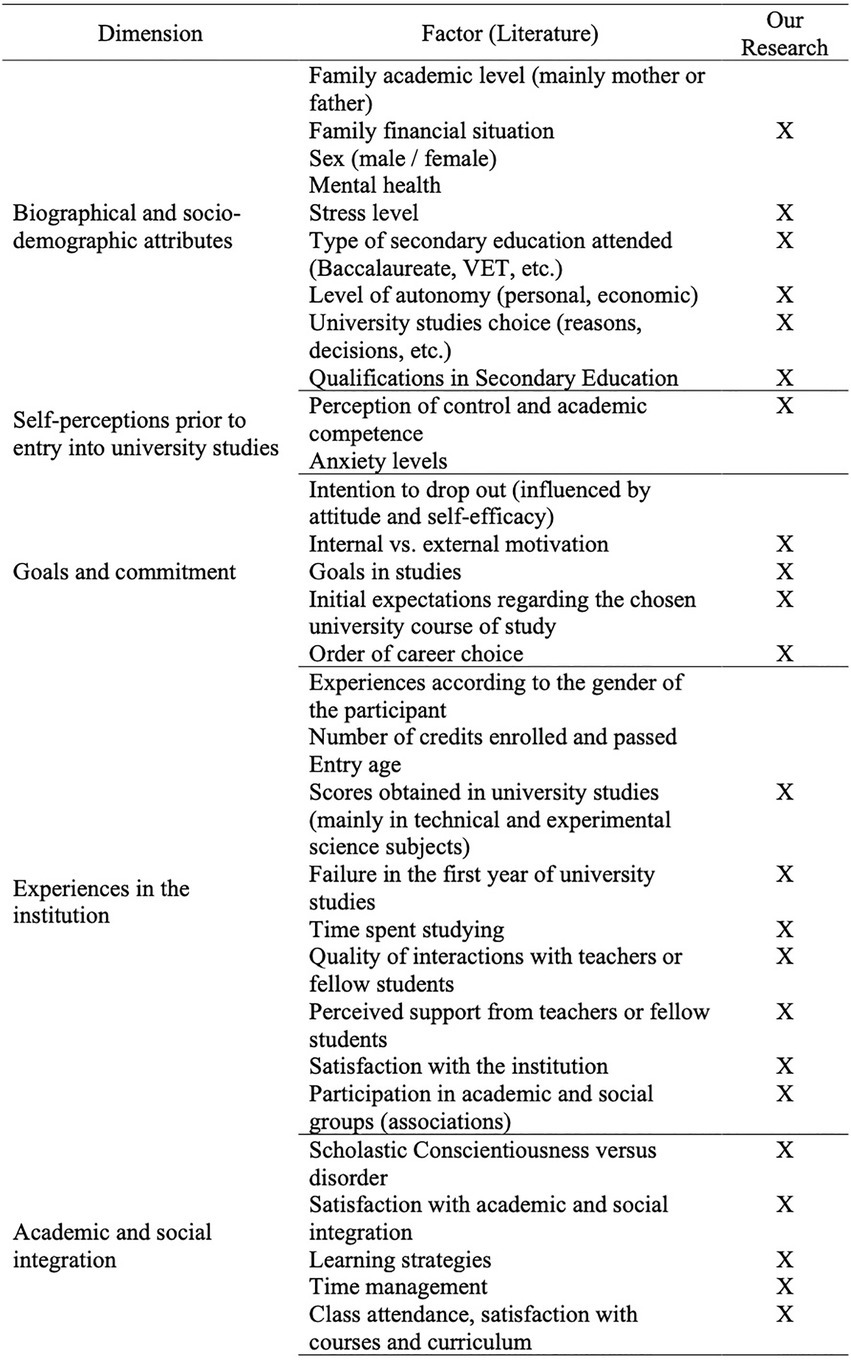

Irrespective of the models we select, several factors related to dropout in higher education are recurrent. Thus, based on the work of Lizarte and other authors in the international sphere (Lizarte, 2017b, 2020; Barroso et al., 2022; Lizarte Simón and Gijón Puerta, 2022) we can establish a set of factors related to early dropout in higher education, which will allow us to organize the narrative data that we will obtain from the application of in-depth interviews, as detailed in the methodological section. In Figure 2 we present the most relevant factors from the literature (Berlanga et al., 2018; Barroso et al., 2022), grouped into dimensions: (a) Biographical and socio-demographic attributes; (b) Self-perceptions prior to entry; (c) Goals and commitment; (d) Experiences in the institution; (e) and academic and social integration.

Figure 2. Factors related to early dropout and their dimensions. Source from Berlanga (2014), Lizarte (2020), Barroso et al. (2022), and Lizarte Simón and Gijón Puerta (2022).

Regardless of the explanatory models of dropout, there are several strategies that universities carry out to overcome dropout, but there are no general protocols to prevent it (Lizarte Simón and Gijón Puerta, 2022). Based on the latest reports from various Andalusian universities, the creation of Guidance Units at the faculties is presented as one of the aid plans that best works avoid cases of abandonment. Orientation is part of the educational process and has become an indicator of the quality and functioning of university systems (Vidal et al., 2002).

As an example, we present the Guidance Unit of the Faculty of Educational Sciences of the University of Granada (Villena et al., 2013), whose most relevant tasks can be grouped into three categories: (a) Care program to the Baccalaureates (reception and attention of Baccalaureate students in the faculty, organizing open days, attention to counselors of Secondary Education Schools, or participation in lectures at Secondary Education Schools); (b) Program of professional opportunities (general planning of activities on professional opportunities for the different degrees, organization of employment preparation workshops -preparation of the curriculum vitae, professional interview, information on jobs-); (c) Assistance program for students with disabilities (list of professors-tutors and students with specific educational support, information and awareness needs for the university community regarding university students with disabilities); (d) Support program for the tutorial function (planning and development of courses for teachers, teacher training, collaboration in the design of a Tutorial Plan, etc.).

The abandonment of university studies is a problem that affects the balance and correct organization of university systems throughout the world and that has undesirable personal consequences in advanced societies. Dropping out of school has a multidimensional explanation. Among the causes, associated with each other, that originate it, the following factors stand out: psychological, social, economic, psycho-pedagogical, institutional, and didactic. Studying how all these dimensions act and relate to each other in specific cases of people who drop out of Higher Education, helps us to better understand the phenomenon and to develop prevention measures in university institutions (Figure 3).

The problem of university dropout affects all universities, although it occurs with different intensities –BBVA Foundation Report– (Pérez and Aldás, 2019). According to the U-Ranking – Spanish Universities report, the differences in dropout rates by region reach 19 percentage points in the case of bachelor’s degrees and 13 points in the dropout rate of SUE (Spanish University System). The highest dropout rate by the regions is led by the Canary Islands with a value of 38.8%, while the lowest dropout rate is in Castilla y León with 19.6%. In the Andalusian case, the dropout rate stands at 28.5%.

The degree dropout rate by year of dropout and Andalusian university (Cohort 2012–2013) is Almería: 29.2%; Cadiz: 34.8%; Cordoba: 27.2%; Grenada: 27.2%; Huelva: 33%; Jaén: 29.7%; Malaga: 28.8%; Pablo de Olavide: 18.5%; Seville: 27.8%. As we can see, the Pablo de Olavide University presents the lowest dropout rate of the Andalusian universities with 18.5%; while the University of Cádiz presents the highest rate with 34.8%. The University of Granada presents a rate of 27.2%, which can be classified as a high rate.

There are several strategies that university institutions carry out to overcome the phenomenon of dropout, but there is no general protocol for action in cases of possible dropout (Lizarte Simón and Gijón Puerta, 2022). Based on the latest reports from various Andalusian universities, the creation of Guidance Units in faculties is presented as one of the aid plans that work best to remedy cases of abandonment. Guidance is part of the educational process and has become an indicator of the quality and functioning of university systems (Vidal et al., 2002).This text presents the results of biographical-narrative research carried out among the student population in a situation of abandonment of the universities of Andalusia that has allowed us to recover 22 stories of abandonment carried out by as many ex-students who were enrolled in any of the nine universities. Andalusians publish in any of the different university degree studies. The biographical texts have been subjected to narrative analysis to achieve personal exemplifications and characterize paradigmatic cases of relationship between the dimensions of the problem, using concept mapping to present the outcomes.

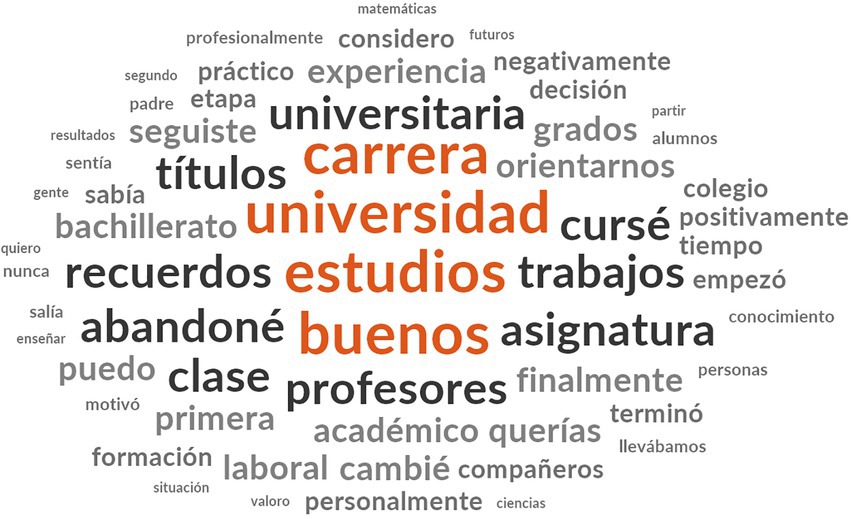

Using NVivo® word frequency queries, we can list the words that occur most frequently in certain resources, in this case the transcripts of the interviews conducted. To refine the search, it has been screened by a minimum length of five letters, which is considered relevant for the Spanish language. Likewise, to avoid sterile repetition, derived words have been grouped and, finally, empty words (articles, prepositions, common verbs, etc.) have been eliminated. This query allows different visualizations: the branching map and the word cloud, which indicate – proportionally with the size – the presence of words; and the cluster analysis, which groups words according to their similarity of occurrence in the different files.

On the one hand, the word frequency query was used to: (a) Create a word cloud to visualize the concepts used in adequate proportion; (b) Define the general feeling that the process of making the abandonment decision linked to their biographical trajectory implied (self-coding by feelings); (c) Create a library of dropout-related keywords, which can serve as a basis for future discourse analysis of university dropout, using software such as Yoshikoder® (Lowe, 2006; automatic autocoding).

On the other hand, a direct narrative reconstruction of the CAB dimension (Causes of dropout) was carried out to establish the most frequently reported dropout factors and to compare them with those established in the literature review. The inductive categorization of the CON dimension (Suggestions and advice) was also carried out. The resulting information was reworked by the research team in a collaborative way, in the form of a narrative reconstruction of the causes of drop-out and in the form of a conceptual map. –Concept Mapping by Novak– (González García et al., 2013; Ibáñez et al., 2014), thus establishing a “knowledge model” generated with the key elements and their agreed relationships within the research team (González García et al., 2013) for the causes and advice that participating students give to participating institutions and other students.

The sample consisted of a total of 23 interviews. Sampling was criterion sampling, based on the subject’s “accessibility” and acceptance of the research conditions. The demographic structure of the sample is presented in Figure 4, including 16 men and 7 women, students from the universities of Almeria, Cadiz, Granada, Cordoba, Jaen and Malaga, from careers related to experimental and biomedical sciences, social sciences, humanities and technical careers. The interviews were labeled with a number associated with the university where the dropout occurred AL01, CA01, GR01-03-04-05-06-07-09, JA01-02-03-04-06-07-08-09-10-11-12-13, MA02.

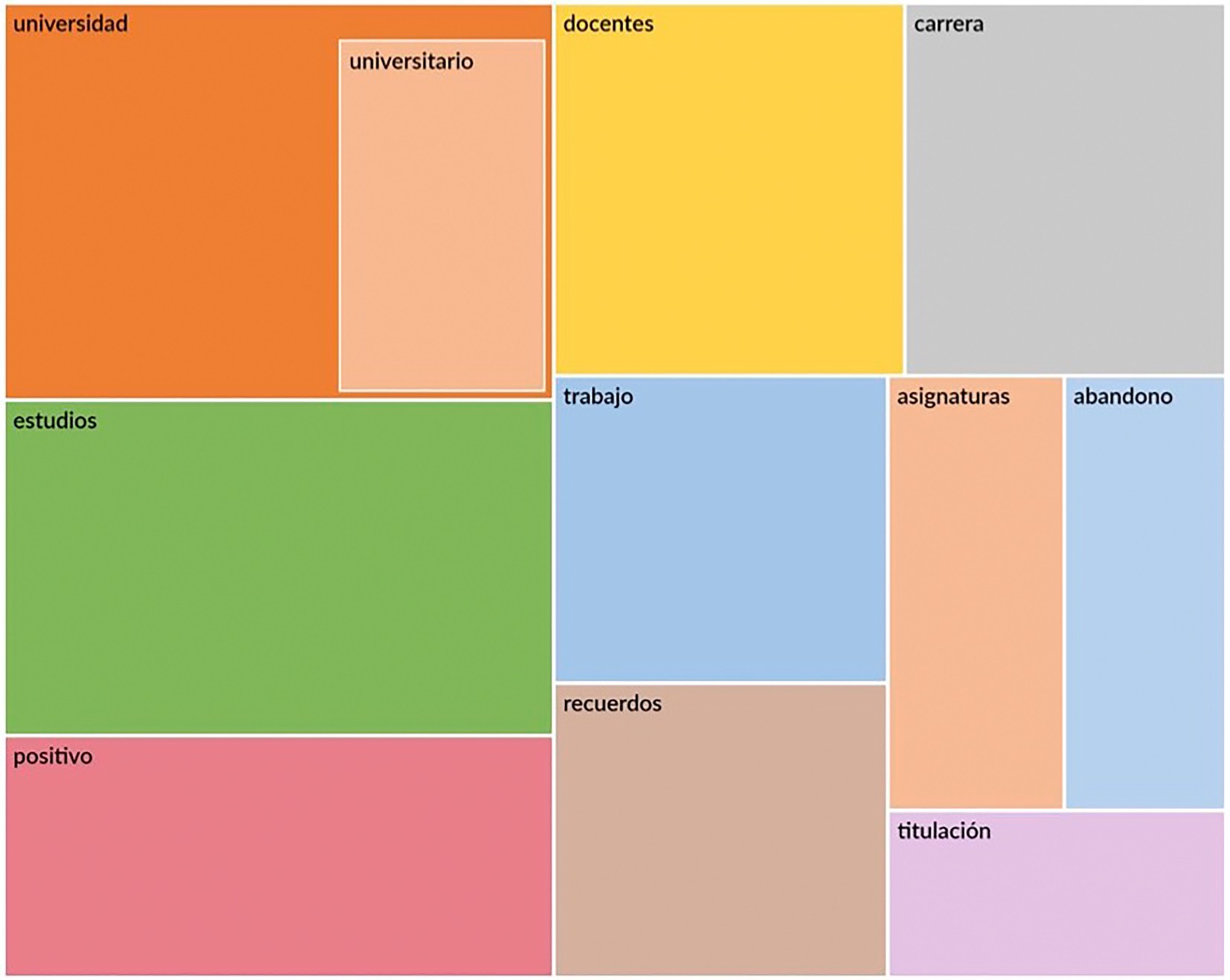

Firstly, the word count consultation carried out has allowed us to establish a “library” of abandonment from the perspective of the research participants. The library, which includes the concepts most used by the students who dropped out and participated in the research, is summarized in Figure 5, highlighting the concepts with the greatest relative weight in Figure 6. These concepts are, in order of frequency: University; Studies; Positive; Teachers; Positive; Teachers; Work; Memories; University Degree; Subjects; dropout and graduation (together with the associated word family).

Figure 6. Representation of the concepts with the highest relative importance that make up the abandonment library. Caption (top to bottom-left to right): (A) universidad (University), (B) universitario (Undergraduate), (C) estudios (Studies), (D) positivo (Positive), (E) docentes (Teachers), (F) carrera (Career), (G) trabajo (Job), (H) asignaturas (subjects), (I) abandono (Dropout), (J) titulación (Grade).

The cloud of concepts generated from the frequency query also shows that the core of concepts that students handle around the process of dropping out, which is not considered negative (“good”) and which is concentrated around the university and the studies taken (“university,” “studies,” and “career”), is complemented by reference to the completion of studies and dropping out (“degree” and “dropout”) and to “memories” of “class,” “teachers” and “subjects” (“good”) and “memories” of “class,” “teachers” and “subjects” (“good”) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Word cloud generated from frequency query (Spanish). Caption -big words-: universidad (University), buenos (Good), estudios (Studies), profesores (Teachers), carrera (Career), trabajo (Job), asignatura (subject), abandono (Dropout), titulación (Grade); recuerdos (Memories).

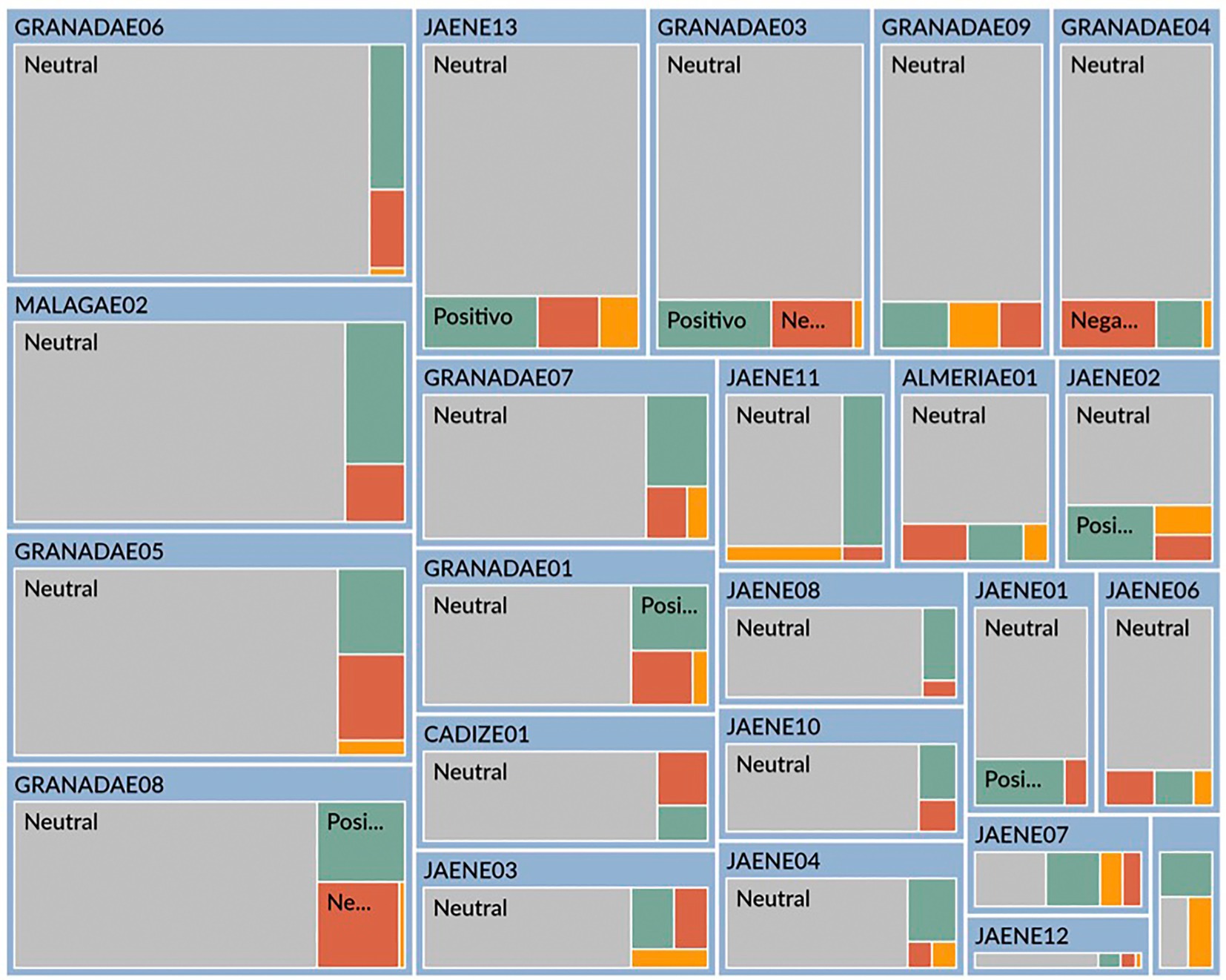

Finally, the self-coding on feelings gives us a general idea of how the students have experienced the dropout process and whether positive or negative aspects dominate in their memories. In our case, out of 486 codes extracted by the program, 22 are indicated as “very negative” and 66 as “very positive,” with those labeled as “moderately negative” –168– and those labeled as “moderately positive” -230- being much more represented. Thus, NVivo® presents the participants’ experiences and feelings about the abandonment process as “neutral” – neither positive nor negative – both at the global level and in each of the cases analyzed (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Representation of self-coding based on feelings. Caption (top to bottom-left to right): (A) GRANADAE06 (Neutral), (B) MALAGAE02 (Neutral), (C) GRANADAE05 (Neutral), (D) GRANADAE08 (Neutral), (E) JAENE13 (Neutral), (F) GRANADAE07 (Neutral), (G) GRANADAE01 (Neutral), (H) CADIZE01 (Neutral), (I) JAENE03 (Neutral), (J) GRANADAE03 (Neutral), (K) JAENE11 (Neutral), (L) JAENE08 (Neutral), (M) JAENE10 (Neutral), (N) JAENEE04 (Neutral), (Ñ) GRANADAE09 (Neutral), (O) ALMERÍAE01 (Neutral), (P) JAENE01 (Neutral), (Q) JAENE07 (Neutral), (R) JAENE12 (Neutral), (S) GRANADAE04 (Neutral), (T) JAENE02 (Neutral), (U) JAENE06 (Neutral).

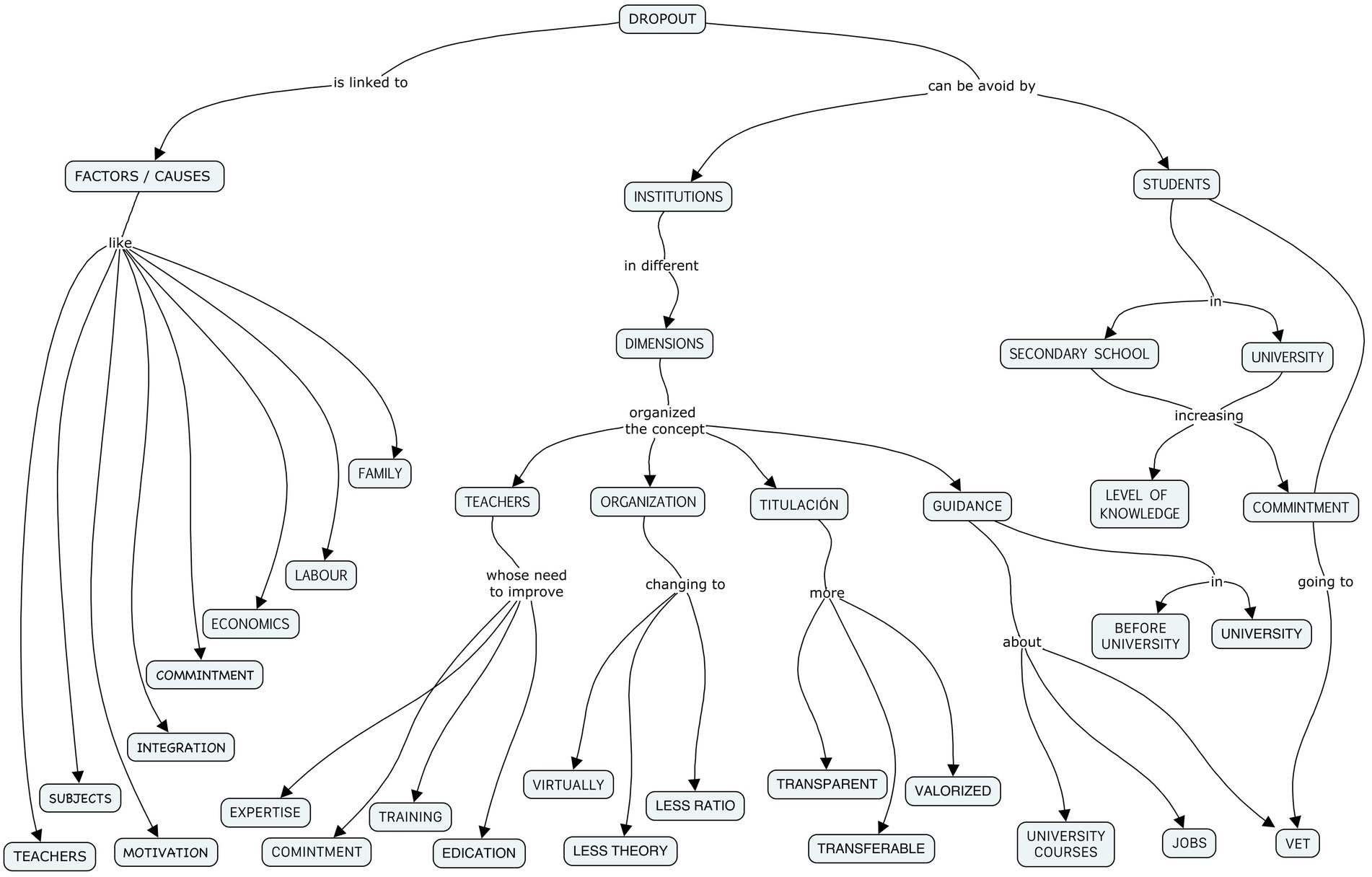

From the narrative review of the CAB and CON dimensions of the interview, it has been possible to construct a conceptual map on the most relevant factors for dropout and the advice offered by participants to prospective students and universities (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Knowledge model representing the factors associated with dropout and with advice from students who dropped out.

Although there are factors (causes) associated with dropout that are circumstantial, such as a «pandemia mundial que al año siguiente tendría que pagar la misma matrícula y con la incertidumbre de hacer curso online o hacer curso presencial» (JA03) (global pandemic that the following year I would have to pay the same tuition and with the uncertainty of taking an online course or taking a classroom course), those that appear are organized around: (a) the teaching staff; (b) the subjects and the career; (c) factors related to motivation; (d) factors related to integration and commitment; (e) economic resources; (f) and work or family problems.

As for the teaching staff, there is a certain lack of involvement and renewal of contents and methods: «el profesor de informática que nos explicaban cositas de matemáticas como si fuéramos retrasados» (GR05) (the computer teacher who explained little things about mathematics to us as if we were retarded).

The subjects, the syllabi, and the degrees themselves are the subject of reflections that place them among the causes of dropout. On the one hand, there is some talk about the difficulty of the courses. JA01 indicates that «abandoné porque después de intentarlo mucho me di cuenta de que no avanzaba en los estudios y cada vez eran más difíciles» (I dropped out because after trying a lot I realized that I was not progressing in my studies and they were getting harder and harder). Also the repetition of content (GR01 states that «estaba un poco desilusionada. Rollo, el temario era muy repetitivo para el primer año, vale. El segundo, vuelves y haces otra vez lo mismo y cuando empiezas el tercero y ves que hacen lo mismo, es como que echas aquí cuatro años para aprender absolutamente nada» (I was a little disappointed. The syllabus was very repetitive for the first year. The second, you come back and do the same thing again and when you start the third and see that they do the same thing, it’s like you spend 4 years here to learn absolutely nothing”) and its eminently theoretical character is highlighted by some students, such as JA02, who states that «lo que me motivó realmente fueron el poco interés que había en ese grado a la actividad práctica y el tanto que había el marco teórico había acercamiento a la historia desde un punto de vista práctico. Simplemente era absorción de conocimiento y luego plasmarlos en un examen» (what really motivated me was the little interest there was in that grade to practical activity and the fact that there was so much theoretical framework there was an approach to history from a practical point of view. It was simply a matter of absorbing knowledge and then translating it into an exam). The transparency and transferability of the degrees is questioned in some cases because «se suponía que ibas a convalidar medio curso, luego no convalidaron nada, me voy a Murcia y ya tuve una lesión que luego no pude terminar tampoco los exámenes» (CA01) (you were supposed to validate half a course, then nothing was validated, I went to Murcia and I had an injury and then I could not finish the exams either).

In some cases, it is the degree that is considered a mistake: «aparte de que ni una asignatura, ni una carrera que me llenaba» (JA03) (apart from the fact that neither a subject, nor the studies that made me happy,” leaving «porque no me gustaba la carrera. Me equivoqué cuando me metí. No era lo que yo esperaba» (AL01) (because I did not like the courses. I was wrong when I got into it. It was not what I expected). And this fact is usually associated with «no encontrar significatividad a lo que estaba haciendo y de no encontrar una motivación y una fuente de orientación dentro del sistema universitario» (JA04) (not finding significance to what I was doing and not finding a motivation and a source of orientation within the university system).

Motivation appears recurrently in the perceptions of the interviewees: JA06 affirms that he dropped out «porque me faltaba motivación, al no obtener los resultados» (because I lacked motivation, because I did not get the results); MA02 affirms that «el último año de la universidad pues ya prácticamente como no estaba motivado fue cuando un poco abandoné el tema de los estudios y me enfoqué a vivir la vida» (in the last year of university, since I was practically not motivated, that was when I abandoned the subject of studies and focused on living life). GR03 presents it clearly when he states that «realmente, estoy pensando, creo que no llegué a presentarme ningún examen de primero, pero que tampoco me puse a preparármelo como tal» (In fact, I’m thinking, I do not think I took any exams in my first year, but I did not prepare for them as such).

Integration and commitment also appear frequently in the participants’ accounts. In some cases, the focus is on teachers and peers («escasa atención por parte del profesorado y poca sociabilización entre compañeros» JA10; «era una gente ultra egoísta, nada más que queriendo presumir sus logros en vez de intentar aprender o enseñar y tal iban a presumir» GR04) (“little attention from teachers and little socializing among peers” JA10; “they were ultra-selfish people, just wanting to show off their achievements instead of trying to learn or teach and so on” GR04). In others, they recognize their own lack of commitment and academic and social integration: JA12 indicates that «no iba a todas las asignaturas al día, no estudiaba como tal de manera intensa, dedicándole un gran número de horas al día hasta que no se iba (…) de lo que creo que han sido bastante buenos para el esfuerzo que realicé» (I did not go to all the subjects a day, I did not study as such in an intense way, dedicating a large number of hours a day until I did not leave (…) so I think they were quite good for the effort I made); GR07 states that «no quiere decir esto que no me haya esforzado, pero sí que los resultados considero que sí, que marca un periodo importante de tu vida» (this does not mean that I did not make an effort, but I do think that the results are good, that it marks an important period in your life); and finally GR06 indicates that «no la aproveché lo suficiente, no porque no me dieran opciones, sino porque yo a lo mejor lo dejé un poquillo» (I did not make enough of it, not because they did not give me options, but because maybe I did not care too much).

Another remarkable aspect is the lack of resources as a determinant factor or cause of dropout, indicated by the participants, which is the lack of financial resources or the need to work to get them. JA08 states that «no podía persistir porque no aprobé todas y no tenía dinero para la matrícula. Me gustaba la carrera, pero no conseguí sacar las asignaturas» (I could not persist because I did not pass all of them and I did not have the money for tuition fees. I liked the course, but I did not manage to pass the subjects). JA10 also stresses the problem of resources, when he indicates that «mis motivos fueron escasa ayuda económica» (my reasons were lack of financial support). JA11 says that «verdaderamente, el principal motivo, como he dicho, fue el económico. El hecho de que ganase buen dinero y que hiciera falta fue lo principal para para no seguir» (the true main reason, as I said, was financial. The fact that I earned good money and that I needed it was the main reason for not continuing), the same as JA13, who tells us that he left «los estudios para trabajar por falta de recursos económicos» (his studies to work due to lack of economic resources).

Finally, it is family problems or incompatibility with work that cause drop-out. Dropping out is caused by «el hecho de que entre el trabajo diario y luego otras circunstancias de tareas, digamos familiares que también tienes» (GR09) (the fact that between the daily work and then other circumstances of duties, let us say family duties that you also have), as time becomes the limiting factor: «por falta de tiempo y no por falta de ganas. Te digo, si tuviera tiempo seguiría estudiando» GR06 (due to lack of time and not due to lack of desire. I tell you, if I had time I would continue studying).

The narrative reorganization of the CON dimension allows us to build the hierarchical knowledge model (conceptual map agreed by experts –in this case the research team–), which shows the relationships or connections between the concepts shown. In our case, two categories or concepts generate a first level – the most inclusive –: students and institutions.

The concept “students” focuses on study, breaking down into “university” and “pre-university studies.” The concept “institutions” unfolds into four less inclusive concepts: teachers; organization; qualification; and guidance which, in turn, is opened to university guidance, pre-university guidance and, with special emphasis, vocational training.

The extensive literature on dropout reveals that several factors recur – with varying degrees of importance – in the different models – of greater or lesser importance, and in some cases as the root cause of dropout. Our findings are generally consistent with the existence of these same factors as the ultimate cause or determinant of early dropout in the first 2 years of a university degree.

Returning to the factors presented at the beginning of this document as a result of recent literature reviews (Berlanga, 2014; Lizarte, 2020; Barroso et al., 2022; Lizarte Simón and Gijón Puerta, 2022), we will mark those that appear in our research after analyzing the content of the 23 semi-structured interviews that form it (see Figure 10, in grey the dropout factors that appear in our study).

Figure 10. Factors related to early dropout and its dimensions (comparison of our results and those of the literature). Source. From Berlanga (2014), Lizarte (2020), Barroso et al. (2022), and Lizarte Simón and Gijón Puerta (2022).

First, we can say that there are no differences associated with the age or gender of the research participants, as well as with anxiety levels or mental health. Nor does the academic level of the parents seem to be related to the dropout factors in our case.

Secondly, economic factors are indeed reflected in several of the individuals interviewed, which seems to justify the concern to increase support for students through new scholarship policies in Spain (Fernández Mellizo, 2022).

Thirdly, factors linked to the student’s academic and social integration and academic commitment remain essential factors in explaining the decision to drop out.

Looking at the results in the various dimensions, we can compare with some previous results in other research.

As for the dimension related to “Biographical and socio-demographic attributes,” it is worth noting that we found no indications regarding the influence of gender on the decision to drop out, unlike other studies, which did find significant differences (Almås et al., 2016; Isphording and Qendrai, 2019).

Within the dimension “Self-perceptions prior to entry into university studies” appears in our research the item “Perception of control and academic competence,” which is frequent in research that focuses on technological or natural science-related careers (Respondek et al., 2017, 2020).

In the “Goals and commitment” dimension, an interesting variable – especially in the Spanish context, which is frequently reported in the literature – is the “Order of career choice,” since in our country, due to the scholarship policy, it is not very expensive to wait a year studying a degree that is not the first choice (Zumárraga-Espinosa et al., 2018; Contreras, 2021).

Within the dimension “Experiences in the institution,” our study collects different factors. Scores obtained in university studies” have been recognized in previous studies and are now being used as a predictor of dropout, using learning machines (Solis et al., 2018). Time spent studying” also appears frequently in studies on dropout (Respondek et al., 2017) using also big data in the case of e-learning (Liang and Yang, 2016).

Finally, “Academic and social integration” is a dimension that is reflected in our study with different factors already referred to in the literature (Scholastic Conscientiousness, Satisfaction with academic and social integration, Learning strategies, Time management, Class attendance, satisfaction with courses and curriculum), and it also appears in many previous and current studies, so we deduce that it continues to be one of the important factors in the decision to leave, as indicated by different authors, both in Spain and internationally (Álvarez et al., 2016; Kehm et al., 2019; Aina et al., 2021; Piepenburg and Beckmann, 2022).

One issue that can perhaps be associated with the Spanish context is the frequency with which participants recommend attending VET-related courses before going on to university studies. In this sense, the existence of a higher number of university students in Spain than in other EU countries, to the detriment of higher vocational training studies, may justify part of the drop-out rate in terms of expectations not fulfilled by university education (practical training, immediate job placement, etc.).

This may be related to the need for more vocational guidance prior to university entrance.

In conclusion, the findings of our study do not differ from those of other geographical contexts and are generally in line with the factors or causes of early dropout that have been clearly established in the literature in recent decades. It is up to educational policies and higher education institutions to implement the processes of teacher training, curricular reorganization and academic and vocational guidance that, on a case-by-case basis, can help to reduce the risk of early leaving.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

JG: writing–review and editing, formal analysis, and methodology. MG: writing–review and editing, formal analysis, and methodology. PG: writing–review and editing, data curation, and investigation. EL: investigation, writing–review and editing, and conceptualization. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

RDI European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) 2014-2020. Junta de Andalucía. Ministry of Economy, Innovation and Science. Reference: B-SEJ-516-UGR18. “Stories of dropout. Biographical-narrative approach to academic dropout in Andalusian universities. Multi-causal analysis and prevention proposals.”

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aina, C., Baici, E., Casalone, G., and Pastore, F. (2021). The determinants of university dropout: a review of the socio-economic literature. Socio Econ. Plan. Sci. 79:101102. doi: 10.1016/j.seps.2021.101102

Almås, I., Cappelen, A., Salvanes, K., Sørensen, E., and Tungodden, B. (2016). What explains the gender gap in college track dropout? Experimental and administrative evidence. Am. Econ. Rev. 106, 296–302. doi: 10.1257/aer.p20161075

Álvarez, P., Cabrera, L., González, M., and Bethencourt, J. (2016). Causas del abandono y prolongación de los estudios universitarios. Paradigma 27, 7–36.

Barroso, P. C. F. M., Oliveira, I., Noronha-Sousa, D., Noronha, A., Cruz Mateus, C., Vázquez-Justo, E., et al. (2022). Dropout factors in higher education: a literature review. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional 26, 1–10. doi: 10.1590/2175-35392022228736T

Bäulke, L., Daumiller, M., and Dresel, M. (2021). The role of state and trait motivational regulation for procrastinatory behavior in academic contexts: insights from two diary studies. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 65:101951. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101951

Bäulke, L., Grunschel, C., and Dresel, M. (2022). Student dropout at university: a phase-orientated view on quitting studies and changing majors. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 37, 853–876. doi: 10.1007/s10212-021-00557-x

Bean, J. P., and Metzner, B. S. (1985). A conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Rev. Educ. Res. 55, 485–540. doi: 10.3102/00346543055004485

Berlanga, V. (2014). La transición a la universidad de los estudiantes becados Universidad de Barcelona. España. Available at: http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/handle/2445/60244.

Berlanga, V., Figuera, M. P., and Pons, E. (2018). Modelo predictivo de persistencia universitaria: Alumnado con beca salario. Educación XX1 21, 209–230. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.20193

Casanova, J. R., Assis Gomes, C. M., Bernardo, A., Núñez, J. C., and Almeida, L. (2021). Dimensionality and reliability of a screening instrument for students at-risk of dropping out from higher education. Stud. Educ. Eval. 68:100957. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100957

Contreras, C. (2021). Determinación de variables predictivas de deserción inicial para generar un sistema de alerta temprana. Análisis sobre una muestra de estudiantes beneficiarios de la beca de nivelación académica en una universidad pública en Chile. Calidad en la Educación 54, 12–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.31619/caledu.n54.828.

Corominas Rovira, E. (2001). La transición a los estudios universitarios: Abandono o cambio en el primer año de universidad. RIE: revista de investigación educativa 19, 127–151. Available at: https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/96361

do Nicoletti, M. C. (2019). Revisiting the Tinto’s theoretical dropout model. High. Educ. Stud. 9, 52–64. doi: 10.5539/hes.v9n3p52

Fernández Mellizo, M. (2022). Análisis del abandono de los estudiantes universitarios de grado en las universidades presenciales en España. Madrid: Ministerio de Universidades.

Figuera Gazo, P., and Torrado Fonseca, M. (2012). “La adaptación y la persistencia académica en la transición en el primer año de universidad: el caso de la Universidad de Barcelona,” in Congreso Internacional e Interuniversitario de Orientación Educativa y Profesional. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2445/32417

Foster, C., and Francis, P. (2020). A systematic review on the deployment and effectiveness of data analytics in higher education to improve student outcomes. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 45, 822–841. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1696945

Gijón Puerta, J., and Crisol Moya, E. (2012). La Internacionalización de la Educación Superior. El caso del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. REDU. Revista de Docencia Universitaria 10, 389–414. doi: 10.4995/redu.2012.6137

González García, F. M., Veloz Ortiz, J. F., Rodríguez Moreno, I. A., Velos Ortiz, L. E., Guardián Soto, B., and Ballester Valori, A. (2013). Los modelos de conocimiento como agentes de aprendizaje significativo y de creación de conocimiento. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS) 14, 107–132. doi: 10.14201/eks.10216

González, L., and Uribe, D. (2002). Estimaciones sobre la" repitencia" y deserción en la educación superior chilena. Consideraciones sobre sus implicaciones. Calidad en la Educación 17, 75–90. doi: 10.31619/caledu.n17.408

Ibáñez, P., Gijón, J., and González, F. (2014). “Revisión del conocimiento acumulado sobre mapas conceptuales a través del análisis de comunicaciones presentadas en los 5 congresos mundiales” in Concept Mapping to Learn and Innovate: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Concept Mapping. 419–426.

Isphording, I., and Qendrai, P. (2019). Gender differences in student dropout in STEM. IZA Res. Rep. 87, 1–15. Available at: http://ftp.iza.org/report_pdfs/iza_report_87.pdf

Kehm, B. M., Larsen, M. R., and Sommersel, H. B. (2019). Student dropout from universities in Europe: a review of empirical literature. Hungarian Educ. Res. J. 9, 147–164. doi: 10.1556/063.9.2019.1.18

Liang, J., and Yang, J. (2016). “Big data application in education: dropout prediction in edx MOOCs” in 2016 IEEE second international conference on multimedia big data (BigMM). (IEEE). 440–443.

Lizarte, E. J. (2017a). Biographical trajectory of a student who dropout pedagogy at the University of Granada. Jett 8, 267–282. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/56122

Lizarte, E. J. (2017b). Análisis de los estudios en la Universidad de Granada: El caso de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación. Granada: Universidad de Granada. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/62301

Lizarte, E. J. (2020). “Early dropout in college students: the influence of social integration, academic effectiveness and financial Stresse” in Experiencias e Investigaciones en Contextos Educativos. eds. F. J. Hinojo, F. Sadio, J. A. Lopez, and J. M. Romero (Madrid: Dykinson), 519–531.

Lizarte, E. J., and Fernández, M. (2020). “Determinantes sociales e institucionales y percepción de los estudiantes de la Universidad de Granada sobre su eficacia en el estudio” in Investigación Educativa e Inclusión. Retos Actuales en la Sociedad del Siglo XXI. eds. T. Sola, J. A. López, A. J. Moreno, J. M. Sola, and S. Pozo (Madrid: Dykinson), 415–430.

Lizarte, E. J., and Gijón, J. (2019). “Ambientes de aprendizaje para las nuevas y viejas metodologías en la Educación Superior” in Investigación, Innovación Docente y TIC. Nuevos Horizontes Educativos. eds. S. Alonso, J. M. Romero, C. Rodriguez, and J. M. Romero (Madrid: Dykinson), 689–701.

Lizarte Simón, E. J., and Gijón Puerta, J. (2022). Prediction of early dropout in higher education using the SCPQ. Cogent Psychol. 9:2123588. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2022.2123588

Lowe, W. (2006). “Yoshikoder: an open source multilingual content analysis tool for social scientists,” in Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, PA.

Pérez, F., and Aldás, J. (2019). U-Ranking. Indicadores Sintéticos de las Universidades Españolas. Fundación BBVA Ivie. Available at: http://dx.medra.org/10.12842/RANKINGS_SP_ISSUE_2019

Piepenburg, J. G., and Beckmann, J. (2022). The relevance of social and academic integration for students’ dropout decisions. Evidence from a factorial survey in Germany. Eur. J. Higher Educ. 12, 255–276. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2021.1930089

Pierella, M.-P., Peralta, N.-S., and Pozzo, M.-I. (2020). El primer año de la universidad. Condiciones de trabajo docente, modalidades de admisión y abandono estudiantil desde la perspectiva de los profesores. Revista iberoamericana de educación superior 11, 68–84. doi: 10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2020.31.706

Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Hamm, J. M., and Nett, U. E. (2020). Linking changes in perceived academic control to university dropout and university grades: a longitudinal approach. J. Educ. Psychol. 112, 987–1002. doi: 10.1037/edu0000388

Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., and Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived academic control and academic emotions predict undergraduate university student success: examining effects on dropout intention and achievement. Front. Psychol. 8:243. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00243

Solis, M., Moreira, M., Gonzalez, R., Fernandez, T., and Hernandez, M. (2018). “Perspectives to predict dropout in university students with machine learning,” in 2018 IEEE International Work Conference on Bioinspired Intelligence (IWOBI). (IEEE), 1–6.

Spady, W. G. (1970). Dropouts from higher education: an interdisciplinary review and synthesis. Interchange 1, 64–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02214313

Tinto, V. (1982). Limits of theory and practice in student attrition. The Journal of Higher Education 53, 687–700.

Tinto, V. (2010). “From theory to action: exploring the institutional conditions for student retention” in Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. ed. J. Smart (Springer)

Torrado Fonseca, M. (2012). El fenómeno del abandono en la Universidad de Barcelona: el caso de ciencias experimentales. Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/134955.

Torrado Fonseca, M., and Figuera Gazo, P. (2019). Estudio longitudinal del proceso de abandono y reingreso de estudiantes de Ciencias Sociales. El caso de Administración y Dirección de Empresas. Educar 55, 401–417. doi: 10.5565/rev/educar.1022

Vidal, J., Díez, G. M., and Vieira, M. J. (2002). Oferta de los servicios de orientación en las universidades españolas. Revista de Investigación Educativa 20, 431–448. Available at: https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/99001

Villena, M. D., Muñoz, A., and Polo, M. T. (2013). La Unidad de Orientación de Centro como instrumento para la Orientación Universitaria. REDU: revista de docencia universitaria 11, 43–62. doi: 10.4995/redu.2013.5566

Wild, S., and Heuling, L. S. (2020). Student dropout and retention: an event history analysis among students in cooperative higher education. Int. J. Educ. Res. 104:101687. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101687

Keywords: dropout, higher education, concept mapping, narrative methodology, biographical method

Citation: Gijón J, Gijón MK, García P and Lizarte EJ (2023) Dropout stories of Andalusian university students. Front. Educ. 8:1130194. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1130194

Received: 22 December 2022; Accepted: 27 February 2023;

Published: 14 April 2023.

Edited by:

Antonio Hernandez Fernandez, University of Jaén, SpainReviewed by:

Isabel Martínez-Sánchez, National University of Distance Education (UNED), SpainCopyright © 2023 Gijón, Gijón, García and Lizarte. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emilio J. Lizarte, ZWxpemFydGVAdWdyLmVz

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.