- Department of Performance, Health and Wellbeing, School of Psychology, University of Worcester, Worcester, United Kingdom

Student mental health and wellbeing is both a priority and area of challenge within Higher Education, with providers seeing an increased demand for mental health, counselling and wellbeing support. The current paper argues that an effective preventative approach to supporting university student wellbeing is one that: (a) addresses student wellbeing using a holistic approach; (b) is underpinned by a comprehensive wellbeing theory; (c) aims to promote key dimensions of individual and collective wellbeing; and (d), can align with HE structures and strategies. Consequently, we describe and evaluate a multi-faceted 8-week online wellbeing programme—Flourish-HE—which follows a positive education ethos and is underpinned by the PERMA-H theory of wellbeing. The mixed method evaluation of Flourish-HE employs an explanatory sequential design with matched pre-post quantitative surveys (N = 33) and follow up qualitative interviews (N = 9). The surveys examine pre-post changes in PERMA-H wellbeing facets, mental health outcomes and sense of community with quantitative results indicating significant increases in positive emotion, positive relationships, meaning or purpose in life, overall mental wellbeing and sense of (course) community following participation in the programme, alongside decreases in depressive symptomology. The qualitative findings supported, and provided further explanation for, the pre-post-test differences and highlighted several barriers to engagement in the programme (e.g., unfavourable preconceptions) and future considerations (such as supporting longer-term effects). The evaluation provides evidence to suggest Flourish-HE is an effective wellbeing programme that can be delivered to students in Higher Education.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, there has been an increase in demand for university mental health services due to a decline in students' wellbeing during their time in Higher Education (HE) (Larcombe et al., 2014; Thorley, 2017). Students face chronic stressors while transitioning to university, including financial pressures and increased academic workload (Robotham and Julian, 2006; Denovan and Macaskill, 2013, 2017). This, in turn, can lead to increases in academic burnout, anxiety and depression among university students (Eisenberg et al., 2007; Shankland et al., 2019). These challenges have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with students reporting additional increases in stress and anxiety (Deng et al., 2021), and experiences of isolation and disconnect from their university community (Zhai and Du, 2020; Liu et al., 2021). Two years on from the start of the pandemic, longer-term consequences are surfacing, such as long-COVID, which may further impact the wellbeing of HE students (Righi et al., 2022). In a population who are deemed at high risk for mental health conditions (Brown, 2018), the existing challenges coupled with the unknown long-term risks of the pandemic is likely to be problematic for university student wellbeing.

Student wellbeing has been identified as an area of priority for the Office for Students, who have provided UK universities with funding to develop support strategies (Office for Students, 2022b). Recent initiatives have included access to therapeutic interventions (University of Birmingham), the development of an online toolkit for academics (University of Derby) and a peer support programme (University of Lincoln) (Office for Students, 2022a). As these are ongoing projects, the effectiveness of these interventions in changing wellbeing outcomes has not yet been established. In a recent systematic review, Upsher et al. (2022) identified 46 wellbeing interventions that have been embedded within university curricula and target student mental health or wellbeing outcomes. These interventions included stress management (e.g., McCarthy et al., 2018), mindfulness (e.g., Damião Neto et al., 2019), art-based (e.g., Evangelista et al., 2017), and assessment-related interventions (e.g., Chen et al., 2015). It is important to note, however, that these interventions are typically focused on unidimensional constructs of wellbeing despite calls to consider wellbeing as a multidimensional construct (Shiba et al., 2022). As wellbeing is best characterised as “a profile of indicators across multiple domains rather than a single factor” (Kern et al., 2015, p. 262), there is a crucial gap for multi-faceted wellbeing interventions within HE. We propose here that an effective approach to supporting university student mental health and wellbeing is one that: (a) addresses student wellbeing using a holistic approach; (b) is underpinned by a comprehensive wellbeing theory; (c) aims to promote key dimensions of individual and collective wellbeing; and (d), can align with HE structures and strategies. The current approach described here constitutes a multi-faceted approach to wellbeing, underpinned by positive psychology theories that sits alongside—and supports—traditional wellbeing provision and formal counselling/mental health services.

1.1. A positive education approach to university student wellbeing

Described as “education for both traditional skills and for happiness” (Seligman et al., 2009, p. 293), Positive Education seeks to support student wellbeing alongside the mastery of traditional academic skills. A myriad of evidence has demonstrated how the successful integration of wellbeing within educational settings can function to enhance positive affective responses, decrease symptomology of mental ill health, enhance social relationships, and promote learning, academic motivation and success (Waters, 2011; Kern et al., 2015; Bani et al., 2020; Vella-Brodrick et al., 2020). As such, it can be argued that a Positive Education approach—and integration of wellbeing in educational institutions—will serve to both enhance wellbeing and support the more traditional goals of academic achievement. A model for wellbeing that has inspired positive education frameworks and has been widely adopted within educational settings is Seligman's (2011) “PERMA” model. PERMA is an acronym that describes five key pillars for wellbeing: Positive emotion, Engagement, positive Relationships, Meaning or purpose in life, and having a sense of Accomplishment and competency. More recently, the addition of a sixth “Health” facet has been proposed in recognition of the importance of physical health for overall wellbeing (Lai et al., 2018). The revised PERMA-H model of wellbeing “embraces a holistic view of physical and psychological health” (Lai et al., 2018, p. 3), with theoretical and empirical evidence demonstrating how each facet of PERMA-H contributes distinctly to overall wellbeing (Forgeard et al., 2011; Seligman, 2011).

Outside of HE, in primary and secondary educational contexts, PERMA(H) has been integrated into school policy, practises and curricula [e.g., Geelong Grammar School Applied Framework for Positive Education (Norrish et al., 2013; Norrish, 2015), and St Peter's College Positive Institution (White and Murray, 2015)]. The adoption of a PERMA(H) approach in schools is testament to the perceived value of the wellbeing pillars to students and other stakeholders, and the ability to integrate PERMA(H) within existing school structures (Waters et al., 2012; Norrish et al., 2013). There is also growing support for the efficacy of PERMA(H)-based interventions within educational settings. An exploratory evaluation of wellbeing outcomes amongst Australian secondary school students participating in a PERMA-based Positive Education Intervention (PEI) yielded a pattern of positive correlations between the various PERMA facets and measures of life satisfaction, hope, gratitude, school engagement, growth mindset and physical vitality (Kern et al., 2015). In Hong Kong, a 3-year PERMAH-inspired PEI has been employed and evaluated within a primary school (Lai et al., 2018). The researchers found that subjective wellbeing of pupils could be predicted by the six facets of PERMA-H. Inverse relationships were also found between the six PERMA-H facets and anxiety and depression, supporting the notion that wellbeing is symptomatic of positive mental health (Keyes, 2002). Such evaluation studies have contributed to an increasing evidence-base showing that PERMA-H wellbeing programmes can be effective at eliciting positive wellbeing outcomes and mitigating mental ill-health within different levels and types of educational systems and cultures. Despite this, integration of the PERMA-H model into HEIs is relatively limited in comparison to its primary and secondary education counterparts. There is reason to believe, however, that each PERMA-H facet is equally applicable to university students.

1.2. The applicability of PERMA-H within HE

Positive emotion (or affective wellbeing) has been linked to problem-solving capacity (Fredrickson, 2013), self-efficacy and academic efficacy (Valiente et al., 2012; Oriol-Granado et al., 2017), coping with academic stress (Freire et al., 2016), a deep approach to learning (Trigwell et al., 2012), and enhanced academic performance (Ben-Eliyahu and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2013). In both school and university settings, positive emotions are claimed to play a key role in student adjustment, friendship formation and engagement in positive social relationships (Phan et al., 2019). The link between positive emotion and favourable academic outcomes may be explained by Barbara Fredrickson's Broaden and Build theory (Fredrickson, 2001, 2004). This theory details how experiencing positive emotion can expand one's thought repertoire, enhance creativity and prompt the development of valuable mental and social resources that be drawn on at a later date. Ouweneel et al. (2011) conducted a longitudinal examination of positive emotions in Dutch university students to examine the applicability of broaden and build to HE. They hypothesised that students' experience of positive emotion would predict their future personal resources and engagement in academic studies. In turn, it was hypothesised that students' personal resources would further predict their study engagement and that positive emotions, resources and engagement would be reciprocally related (demonstrating the cyclical effect of broaden and build theory). All hypotheses, apart from the direct relationship between positive emotion and study engagement, were supported in their sample indicating the potential immediate and longer-term benefits of promoting positive emotion within HE.

The Engagement facet of PERMA-H relates to engagement in all aspects of life including, for this population, engagement in studies and academic life more broadly. Student retention in academic settings is maximised when students feel a sense of belonging within, and commitment to, the educational institution in which they are studying (Christenson et al., 2001). A meta-analysis on the relationship between academic engagement and achievement (Lei et al., 2018) suggests a moderately strong and positive relationship between these constructs, with emotional, cognitive and behavioural elements of engagement all predictive of academic achievement. Of relevance to this facet of wellbeing is Csikszentmihalyi's Flow theory (Csikzentmihalyi, 1990, 1997). “Flow” is described as a heightened state of engagement where one is functioning at optimal capacity (Csikszentmihalyi et al., 2005). Flow has been linked to motivation and engagement in academic contexts (Shernoff et al., 2003) with evidence suggesting that the experience of flow can enhance enjoyment in learning, such that learning becomes intrinsically rewarding (Csikszentmihalyi et al., 1994; Mesurado et al., 2016). Flow (as a temporary mental state of absorption) has been considered alongside conceptualizations of engagement as a more persistent state of mind, to create multi-dimensional views of academic engagement. For example, the concept of “work engagement”, which has been applied to university students (Schaufeli et al., 2002), comprises absorption alongside vigour (mental resilience and investment of energy/effort) and dedication (seeing academic work as important and demonstrating eagerness and pride in one's work). Together, these three facets of academic work engagement have been positively related to wellbeing (Tayama et al., 2018) and enhanced academic performance (Salanova et al., 2010).

As previously described by Oades et al. (2011), universities encourage social interaction amongst many diverse groups and, as such, promote opportunities for fulfilling social relationships. Having a sense of belongingness within a university is associated with fewer symptoms of loneliness, anxiety and depression (Arslan et al., 2020; Arslan, 2021), and supportive relationships within academic settings promotes citizenship, intrinsic motivation for learning and enhanced academic outcomes (McGrath and Noble, 2010). As neatly summarised, “universities seem to be ideal settings for the systematic promotion of positive relationships” (Oades et al., 2011, p. 436).

Having a sense of meaning in life has been related to greater coherence, goal directedness and sense of purpose (Steger, 2009; Shin and Steger, 2016). Evidence suggests that the presence of meaning in life may be a protective factor for mental health, given its negative relationship to depression and anxiety symptomology (Steger et al., 2006). Within student populations, meaning in life has been linked to higher levels of self-esteem and self-acceptance (Ryff, 1989; Steger et al., 2006), adjustment to academic life (Park and Folkman, 1997), circumventing acculturative stress (Pan et al., 2008), as well as academic attainment (DeWitz et al., 2009; Olivera-Celdran, 2011; Bailey and Phillips, 2016). Academic attainment may be further supported by students' sense of accomplishment. Seligman (2011) describes accomplishment to involve progressing towards goals and, importantly, setting and monitoring goals for learning are linked to enhanced academic performance and decreased academic burnout (Morisano et al., 2010; Rehman et al., 2020). In turn, a sense of academic accomplishment or positive academic performance can increase students' self-efficacy around their academic goals. Talsma et al. (2018) provided evidence for a reciprocal relationship between self-efficacy and academic performance. Their meta-analysis (N = 2,688) suggests that students' academic performance can predict their academic self-efficacy, and self-efficacy can predict future academic performance (but to a lesser degree). These results indicate the longer-term consequences of a sense of achievement or accomplishment in university students. More recently, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, research has indicated that university students' perceived self-efficacy for dealing with challenge can positively influenced their academic grades (Sulla et al., 2022).

Finally, in relation to health, physical fitness and diet have been linked to academic performance (Burrows et al., 2017; Zhai et al., 2022) and resilience (Whatnall et al., 2019), while sedentary behaviour is adversely related to university grades (Babaeer et al., 2022). Unhealthy sleep patterns and insufficient sleep have been identified as particularly problematic in university and college students (Pilcher et al., 1997; Lund et al., 2010), with the COVID-19 pandemic further increasing the prevalence of sleep problems in undergraduate students (Valenzuela et al., 2022) and negatively impacting on their sleep efficiency (Benham, 2021). This has adverse consequences for learning and academic performance due to the key role sleep plays in attention and executive functioning, as well as memory consolidation (Fonseca and Genzel, 2020). Looking more broadly at predictors of academic success, DeBerard et al. (2004) demonstrated how college students' health-related quality of life was predictive of student retention. In combination, these sources of evidence suggest that promoting physical health in university students (through a focus on activity, diet and sleep) would be beneficial for both physiological and academic outcomes. Thus, while the integration of PERMA-H within universities is limited to date, the arguments outlined here provide clear evidence for the applicability of this framework within HE contexts.

1.3. The Flourish-HE wellbeing programme

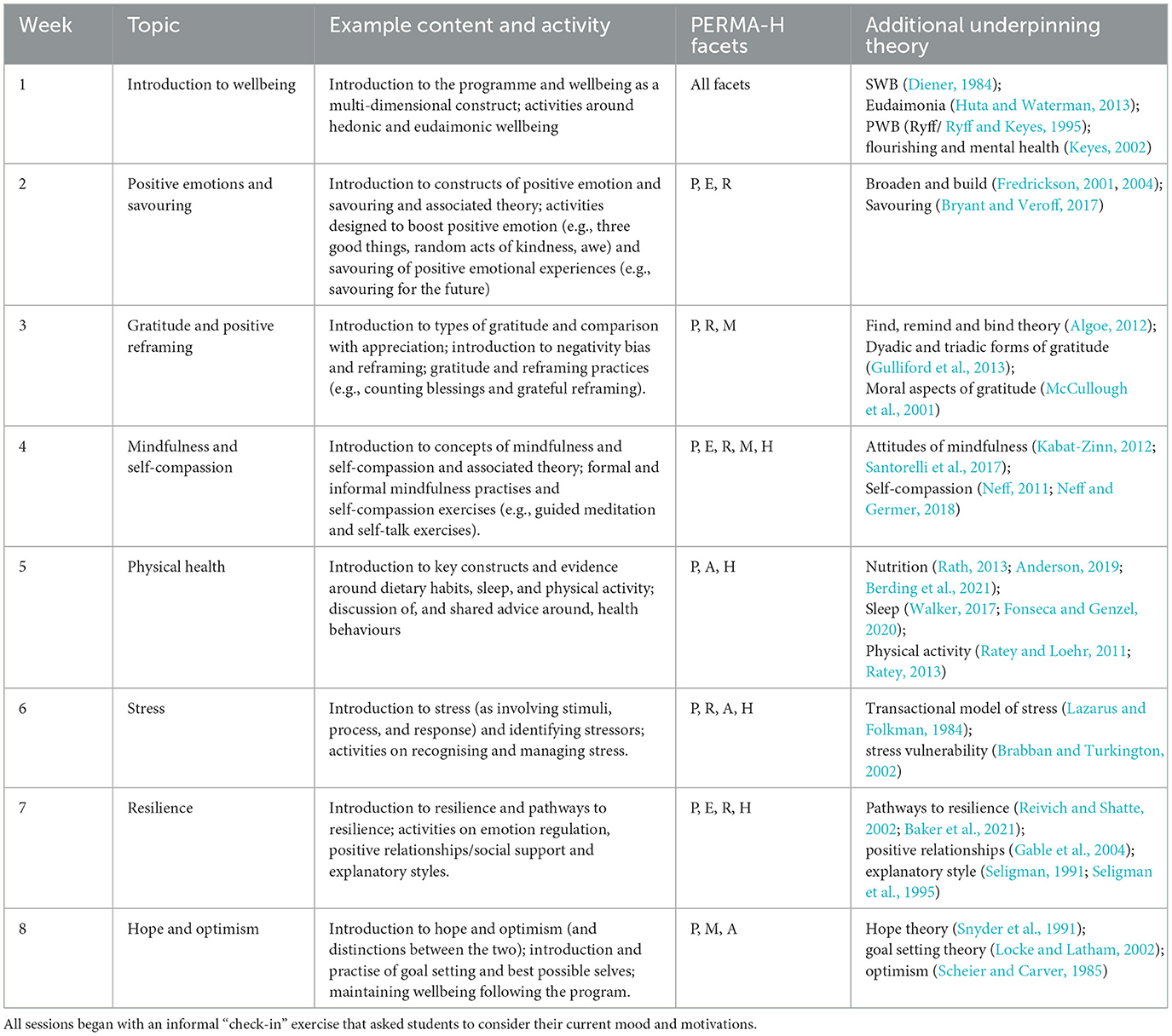

The current paper describes the design, delivery and evaluation of a multi-component wellbeing programme designed to support the wellbeing and mental health of UK university students. Flourish-HE is an 8-week wellbeing programme comprised of weekly 1-h wellbeing sessions. The content of these sessions can be seen in Table 1. The wellbeing sessions take place online through a Virtual Learning Environment. The sessions contain background information on wellbeing constructs (i.e., key theories, frameworks, or principles) and interactive activities to promote wellbeing and social interaction with peers. All information, resources and activities included in these sessions are underpinned by theoretical and empirical evidence, with a particular emphasis on content from positive psychology (see Table 1). Elements of this program were first piloted in April-May 2020 and delivered a second time—with evaluation—in February-March 2021. This multi-faceted programme is inspired by the PERMA-H model (Seligman, 2011; Lai et al., 2018) and offers a holistic approach to supporting university students' emotional, psychological, social and physical wellbeing. Each session is designed to promote one or more of the six PERMA-H facets of wellbeing, as indicated in Table 1 (Please also see Morgan and Simmons, 2021, for further description of the wellbeing content and activities).

Table 1. Overview of the topics and content covered within the 8-week Flourish-HE wellbeing programme, with reference to the PERMA-H facets that were emphasised.

As described in the introductory section, HE students experience both lower levels of wellbeing than the general public (Stewart-Brown et al., 2000), but are also at higher risk of mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression (Andrews and Wilding, 2004; Brown, 2018). It is, therefore, relevant to note that developing emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing (e.g., through addressing the PERMA-H pillars) can promote positive mental health (Keyes, 2002). Evidence further indicates that enhancing wellbeing can alleviate symptoms of mental ill health, including depression and anxiety (Keyes, 2002; Seligman et al., 2005; Fava and Tomba, 2009; Gander et al., 2013). To this end, the Flourish-HE programme also seeks to support positive mental health by providing self-directed exercises and activities that promote the development of emotional, psychological and social wellbeing. Given that such a preventative approach has been suggested to buffer against mental health crises (Waters et al., 2022) and act as an antidote to mental ill health (Kern et al., 2015), an indirect goal of the current programme was to alleviate pressure on central university services by mitigating referrals to counselling services.1 Further to this, and as evidenced in the preceding section, promoting the PERMA-H wellbeing facets is linked to a wide array of beneficial academic outcomes. By taking a positive education approach, the programme should also function to enhance student learning, for example, through encouraging course engagement and connectedness.

1.4. Overview of the current research

A mixed method evaluation of the 8-week Flourish-HE programme was conducted to examine the degree to which the programme is able to: (a) enhance the six facets of wellbeing described by the PERMA-H model; (b) enhance student learning as gauged via work engagement and sense of community; and (c) alleviate symptoms of mental ill health that have been associated with university study, namely anxiety, depression and academic burnout.

The evaluation employed an explanatory sequential (QUANT –>QUAL) mixed research design which comprised quantitative surveys to examine pre/post differences in key wellbeing, mental health and academic-related outcomes and qualitative (semi-structured) interviews to explore student experiences of the programme alongside facilitators and barriers to programme engagement. The mixed research design comprised four phases or time-points: (i) the pre-intervention phase (here, pre-test self-report measures were completed, up to 2 weeks before the intervention began); (ii) the intervention phase (during which the 8-week online program was delivered to students); (iii) the post-intervention phase (when participants completed post-test self-report measures up to 2 weeks after the final wellbeing session); and (iv) a qualitative follow-up phase (where students could opt-in to a semi-structured interview to discuss their experiences during and following the programme). The research design included two groups of participants: the intervention group who participated in Flourish-HE and a measurement-only control group who did not participate in the programme. For individuals participating in the Flourish-HE programme, it was hypothesised that:

H1: Students' wellbeing, as gauged by the six facets of PERMA-H, will increase following participation in Flourish-HE.

H2: Students' symptomology of mental ill health—specifically depression, anxiety and academic burnout—will decrease following participation in Flourish-HE.

H3: Students' levels of academic work engagement and sense of course community will increase following participation in Flourish-HE.

H4: The degree of change observed (when testing Hypotheses 1–3) will be influenced by the number of wellbeing sessions attended and continued practise of wellbeing activities introduced.

2. Methods

2.1. Quantitative methods

2.1.1. Participants

The “Flourish-HE” programme was offered to all undergraduate and postgraduate students studying Psychology and Criminology courses at a Higher Education Institution in the West Midlands, UK. Reviews of positive psychology interventions (including those that are multi-component, 8 weeks long, delivered online and have an intervention group and a neutral control group), have demonstrated that significant effects can be observed in sample sizes as small as 13–16 participants per group/condition (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Casellas-Grau et al., 2014; Hendriks et al., 2020). The average number of participants in intervention studies of this nature has been identified as 35 and the average retention rate of participants as 74% (Hendriks et al., 2020). Following this, we aimed to recruit 48 participants to the intervention condition and 48 participants to the control, with a view to retaining 35 participants in each group at the post-phase data collection point. Participants were recruited via volunteer sampling with the pre- and post-intervention surveys advertised within teaching sessions, emails and advertised on a research participation site. The post-intervention survey also invited participants to opt-in to the qualitative phase of the current research (see Section 2.2 for details of the qualitative methods) and, for students that indicated interest, they were given details regarding booking an interview slot. No financial incentives were offered to students for any phase of the research, however, they were able to receive course credit if they took part via the departmental research participation site.

Fifty-eight students completed the pre-intervention survey and 57 completed the post-survey. Forty-three of the post-survey respondents engaged with the wellbeing program and, of these, 33 students provided data for both time-points (see Appendix B for a flowchart of participants). Students' ages ranged from 18 to 55 years (mean = 26 years), 26 identified as female/woman, five as male/man, two as non-binary or transgender. Eighty-five percentage were undergraduate students (27% first year; 24% second year; 33% third year) and 15% postgraduate (12% Masters students; 3% PhD students). The sample included a mix of home and international students. While attempts were made to recruit a separate group of students as a measurement-only control, only 14 controls completed the post-survey and, of these, three provided pre-survey responses for comparison. Unfortunately, this left an insufficient number of control participants for analysis. This issue is considered further in the discussion.

2.1.2. Materials

2.1.2.1. Pre and post measures

Participants were asked to complete the following scales pre and post the wellbeing programme via an online survey:

The PERMA-profiler (Butler and Kern, 2016)

This 23-item self-report scale was employed to measure the original five wellbeing facets outlined in the PERMA model alongside physical health. Example items include, “How often do you feel joyful?” (positive emotion item) and “How satisfied are you with your personal relationships?” (positive relationships item). Participants respond using an 11-point Likert scale which ranges from 0 = never to 10 = always, 0 = terrible to 10 = excellent, or 0 = not at all to 10 = completely. Previous studies have demonstrated that the overall scale—and each of the subscales—have acceptable internal and test-retest reliability and evidence of content validity across multiple samples, including within student samples (Butler and Kern, 2016). A total overall wellbeing score, or scores for each of the PERMA-H facets can be calculated using the PERMA-profiler. Given the mapping of the programme to the PERMA-H model, total scores for each facet of wellbeing were calculated and entered into analysis. The PERMA-profiler has been tested on a wide range of populations, including university students and UK participants (see Butler and Kern, 2016). Across these populations, the PERMA-profiler has demonstrated good internal consistency for the measure overall (α = 0.92–0.95) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.69–88). Similarly, adequate to good levels of internal consistency and test-retest reliability have been observed for each of the PERMAH facets (Positive emotion: α = 0.71–89; r = 0.65–0.88; Engagement: α = 0.60–0.81; r = 0.51–0.81; Relationships: α = 0.75–0.85; r = 0.66 −0.90; Meaning: α = 0.85–0.92; r = 0.61–0.86; Accomplishment: α = 0.70–0.86; r = 0.62–0.80; and Health: α = 0.85–0.94; r = 0.75 −0.86).

The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (Stewart-Brown et al., 2009)

A 14-item measure of mental wellbeing was also included in this study given the limited use of the PERMA-profiler in UK university samples. The WEMWBS implements a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 0 = none of the time – 5 = all of the time. All items are positively worded, for example, “I have been feeling optimistic about the future”. This measure has shown evidence of content validity and test-re-test reliability, and has been widely used with student samples (α = 0.89, student sample). Total scores are calculated to provide an index of mental wellbeing, with higher scores demonstrative of higher levels of wellbeing.

PROMIS Anxiety and depression (short-form) scales (Pilkonis et al., 2014)

The depression short scale is comprised of eight items and the anxiety short scale contains seven items and both are designed for use with normal populations. Participants are asked to consider the previous 7 days and respond to items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. Example items include, “I felt hopeless” (depression item) and “I felt uneasy” (anxiety item). Both scales have demonstrated good internal reliability (α > 0.90). Where researchers wish to compare participant scores to those in the general population, raw scores are converted to item response theory-based T-scores. However, as the current researched simply aims to track changes in depression and anxiety symptomology across time, raw total scores were calculated and entered into analysis.

Academic burnout was assessed using the 5-item exhaustion scale from the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS; Schaufeli et al., 2002). Respondents used a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always) to identify their current levels of exhaustion related to their academic studies (e.g., “I feel emotionally drained by my studies”). The scale has been tested and validated with university students and demonstrates good psychometric properties. An overall burnout score is derived from average responses across items (ranging from 0 to 6), with higher scores indicating higher levels of academic burnout. This measure has been tested with students across a range of countries and has consistently demonstrated internal consistency with Cronbach's α scores of above 0.70 (Schaufeli et al., 2002).

Classroom Community Scale (Rovai, 2002)

The 10-item Connectedness subscale of the Classroom Community scale was employed to examine a sense of community in the learning environment. Items are responded to using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Example item: “I feel connected to others in this course”. Three negatively worded items (e.g., “I feel isolated in this course”) are reversed scored. The connectedness subscale has demonstrated good psychometric properties indicating it is reliable as a stand-alone measure (α = 0.92). Total scores were calculated by summing across items.

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student (UWES-S-9; Gusy et al., 2019) will be used to measure academic engagement. This is a 9-item scale comprised of six items that measure vigour (e.g., “when studying I feel strong and vigorous”); five items measuring dedication (e.g., “I am proud of my studies”) and six items measuring absorption (e.g., “when I am studying, I forget everything else around me”). Items are responded to using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. This has been used with university students across a wide range of studies (Stoeber et al., 2011). Separate scores for vigour, dedication and absorption are calculated from average responses across each subscale (ranging from 1 to 7), with higher scores reflective of higher facets of work engagement. The 9-item version of UWES has demonstrated good internal consistency overall (α = 0.86), as well as across each of the subscales (α = 0.70–0.86, Gusy et al., 2019).

2.1.2.2. Key covariates

Perceived stress

The post-test measurements were conducted during assessment periods (a time of heightened academic stress), therefore, students' levels of perceived stress at Time 2 were gauged as a control variable. The Perceived Stress Scale (or PSS-10, Cohen and Williamson, 1988), a 10-item scale measures the degree to which individuals perceives aspects of their life as uncontrollable, unpredictable, and overloading, was employed. Participants were asked to reflect on the past month and respond to items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) where higher scores demonstrate higher levels of perceived stress. Example item: “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”. The scale has been tested and validated across a wide range of samples and contexts and demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current study (α = 0.91). There are four items that require reverse scoring before summing all items to provide a total perceived stress score. Participants' stress scores at T2 (during post-survey completion) were included as a covariate in the quantitative analysis.

Coronavirus anxiety

Given that the Flourish-HE programme and evaluation took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-Anxiety was included as a possible covariate and examined to gauge whether anxiety around contracting COVID-19 might prohibit participants from engaging in wellbeing pursuits or interrupt healthy habits. The Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS, Lee, 2020) is a new 5-item scale of dysfunctional anxiety associated with COVID-19. Respondents were asked to reflect on the previous 2 weeks and respond to items, for example “I had trouble falling or staying asleep because I was thinking about the coronavirus”, using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day). This is a new scale but existing reliability and validity tests in the US have shown the scale to have good psychometric properties (α = 0.93) and the internal reliability of the scale was similarly robust in the current study (α = 0.91). Total summed scores for COVID-19 anxiety at Time 1 (during pre-survey completion) were included in the analysis as a covariate.

Attendance and engagement

To gauge the degree of attendance and engagement in the wellbeing programme, additional questions regarding the sessions attended and continued practise of wellbeing activities were included in the post-phase online survey. Specifically, participants were asked to indicate which of the eight wellbeing sessions they attended, and to identify any cases where wellbeing activities introduced within the wellbeing programme were practised outside of the sessions. Separate summed scores were calculated for the number of sessions attended and the number of sessions where “homework” was completed. These two summed scores were entered as covariates in the quantitative analysis.

Other wellbeing practices

In order to acknowledge possible confounding factors within the evaluation, participants were asked to provide brief details around their existing/additional wellbeing practises within an open-ended textbox response.

2.1.3. Procedure

Upon accessing the online surveys, participants asked to provide basic demographic information on their age, gender and level of study, and to create (pre-survey) or re-enter (post-survey) a unique ID code. Following this, participants completed the aforementioned scales in the order they are introduced above. The surveys took an average of 17 min to complete.

2.1.4. Data analysis

Pre and post intervention scores were calculated for all measured outcomes and all participants (as outlined in the materials section). Responses to the open-ended survey question around existing wellbeing practises were analysed thematically generating ten categories of wellbeing practises. An indicative score of existing practise was calculated by summing the number of wellbeing practises reported by participants.

With insufficient data for an intervention and control group comparison, the quantitative data analysis focused on pre- and post-intervention changes within students partaking in the Flourish-HE programme. A repeated measures MANCOVA was conducted to examine pre-post changes in the various outcome variables listed above, alongside the key covariates of COVID-19 anxiety at Time 1, perceived stress at Time 2, programme attendance, homework engagement, and existing wellbeing practises (see Section 3).

2.2. Qualitative methods

2.2.1. Participant selection

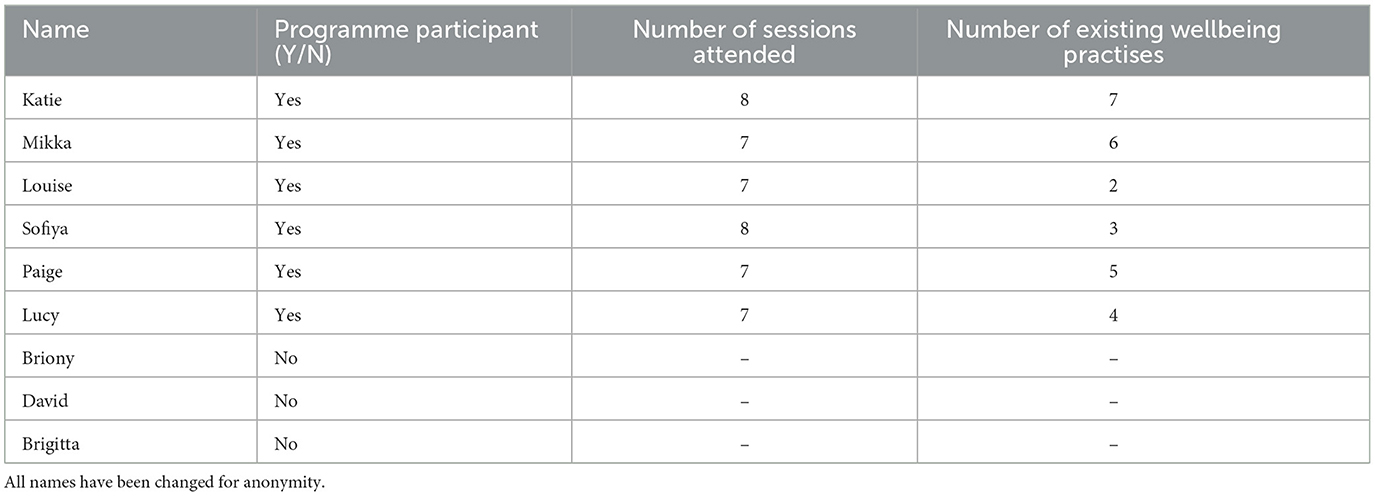

Participants were recruited using volunteer sampling with students declaring their interest within the post-survey. A total of nine participants took part in the qualitative phase (see Table 2). Six participants had attended an element of the wellbeing programme and three participants had not attended any element of the programme (see Appendix B for a flowchart of participants). Participants' ages ranged from 20 to 31 years and interviewees included both undergraduate and postgraduate students, and home and international students.

2.2.2. Materials

Data were collected using an interview schedule that consisted of two sections. The first section of the interview was for programme attendees only and explored participants' wellbeing in relation to the PERMA-H facets (e.g., “Have your levels of interest and involvement in your daily life and activities changed at all following participation in the programme?”). The second section of the interview was relevant to both programme attendees and non-attendees and explored facilitators and barriers to programme engagement (e.g., “Did you encounter any barriers which prevented you from taking part in any element of the programme?”). Interview duration ranged from 16 to 31 min, with an average interview time of 24 min.

2.2.3. Procedure

Interviews were conducted online via a Virtual Learning Environment. After the interviews were conducted, the audio was transcribed verbatim. Punctuation and non-verbal cues (e.g., laughter) were excluded to ensure that these did not change the meaning of the text (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Transcripts were cleaned prior to analysis by removing repetitions and adding words to aid understanding. Personal or identifiable information, such as names and places, were also anonymised and removed from the transcript. The qualitative follow-up interviews took place between 2 and 5 weeks after the end of the Flourish-HE programme, during April and May.

2.2.4. Researcher description

The research team consisted of academics who are directly involved with teaching and research in HE. The researchers had a background in facilitating wellbeing provision across the public, private and third sector, in addition to intervention development and evaluation. All researchers were familiar with the concept of wellbeing through research and direct contact with students by providing pastoral support. All members of the team were actively involved in the teaching of students who participated in the wellbeing programme and the qualitative interviews. This may have led to some positivity bias towards the programme. However, this pre-existing relationship allowed trust and rapport to be built between the interviewer and participant, presenting an opportunity for participants to disclose information about their experiences that may not have been uncovered in the absence of this relationship (DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree, 2006).

2.2.5. Data analysis

The data were analysed using both deductive and inductive thematic analysis in accordance with Braun and Clarke's (2006) framework. Data collected during the “PERMA-H section” of the interview were primarily analysed deductively by mapping responses to the PERMA-H framework. To begin, data were familiarised through reading and re-reading the transcripts and an initial mapping exercise to PERMA-H facets. To aid in the deductive analysis, a qualitative codebook was created by the research team based on the initial mapping exercise, providing definitions and inclusion criteria for the PERMA-H facets (see Appendix A). The codebook was developed to reduce subjectivity and prompt consistent coding practises across researchers. Following deductive analysis, the researchers also identified additional inductive themes where data responding to wellbeing changes did not clearly fit with the codebook (for example, discussions of overall levels of wellbeing and decreases in negative affect). Data collected during the “facilitators and barriers section” of the interview schedule were analysed inductively. Data were initially coded independently by the three researchers before being reviewed collectively. Any discrepancies in coding were discussed by all researchers until agreement was reached and themes were named and defined.

3. Results

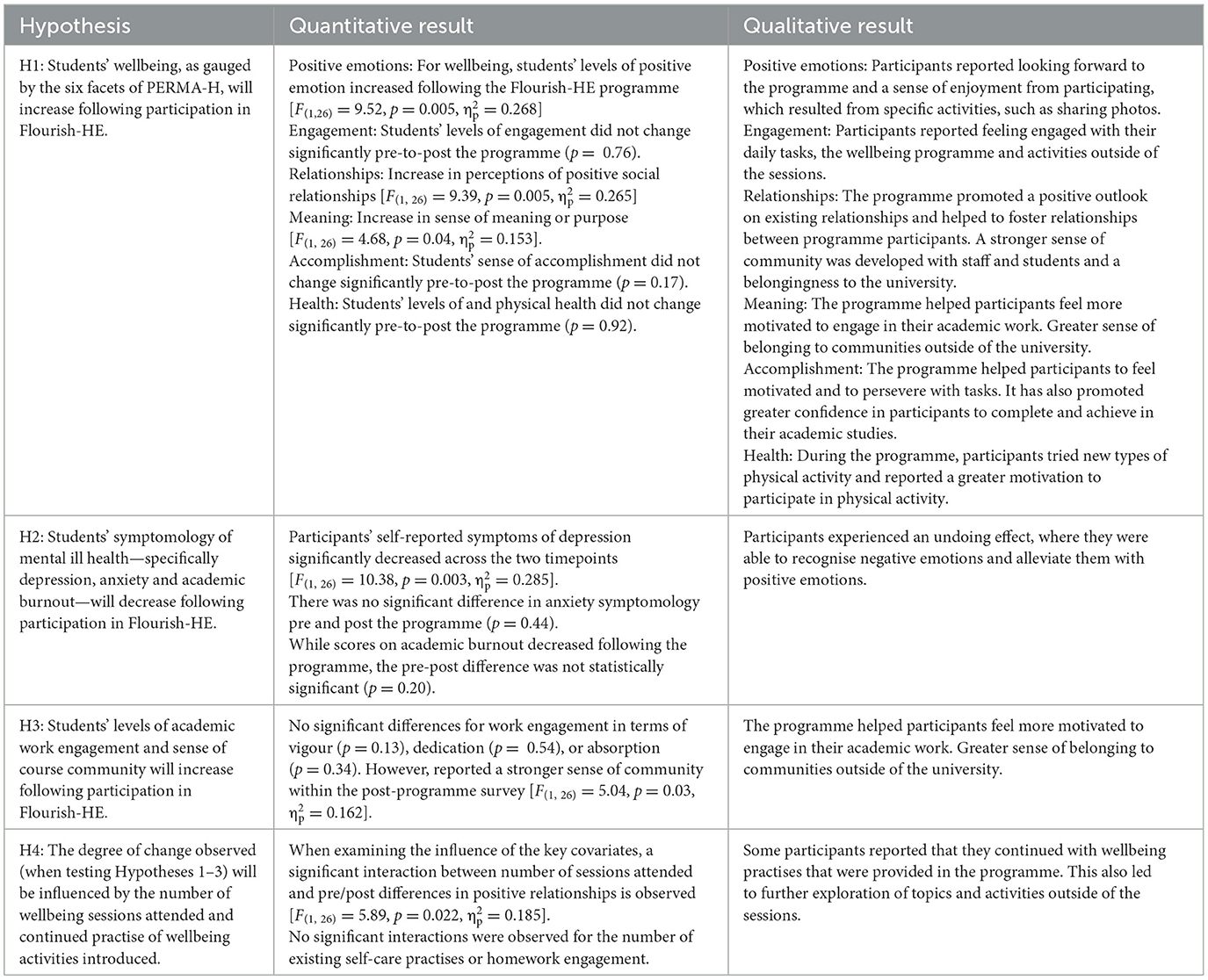

The mixed method results were integrated using a weaving approach where qualitative findings have been used to explain the quantitative results (Fetters et al., 2013). The results section will begin with an overview of the quantitative results from the pre/post online surveys. Following this, the qualitative findings from the semi-structured interviews will be outlined and concurrently integrated with the quantitative results. The qualitative findings and integration is presented in two parts, the first relates to the PERMA-H framework and the second is related to experiences and perceptions of the programme. Table 4 within the qualitative findings and integration section provides a summary of the quantitative and qualitative findings with respect to the four hypotheses being examined within the current research.

3.1. Quantitative results

3.1.1. Descriptive statistics

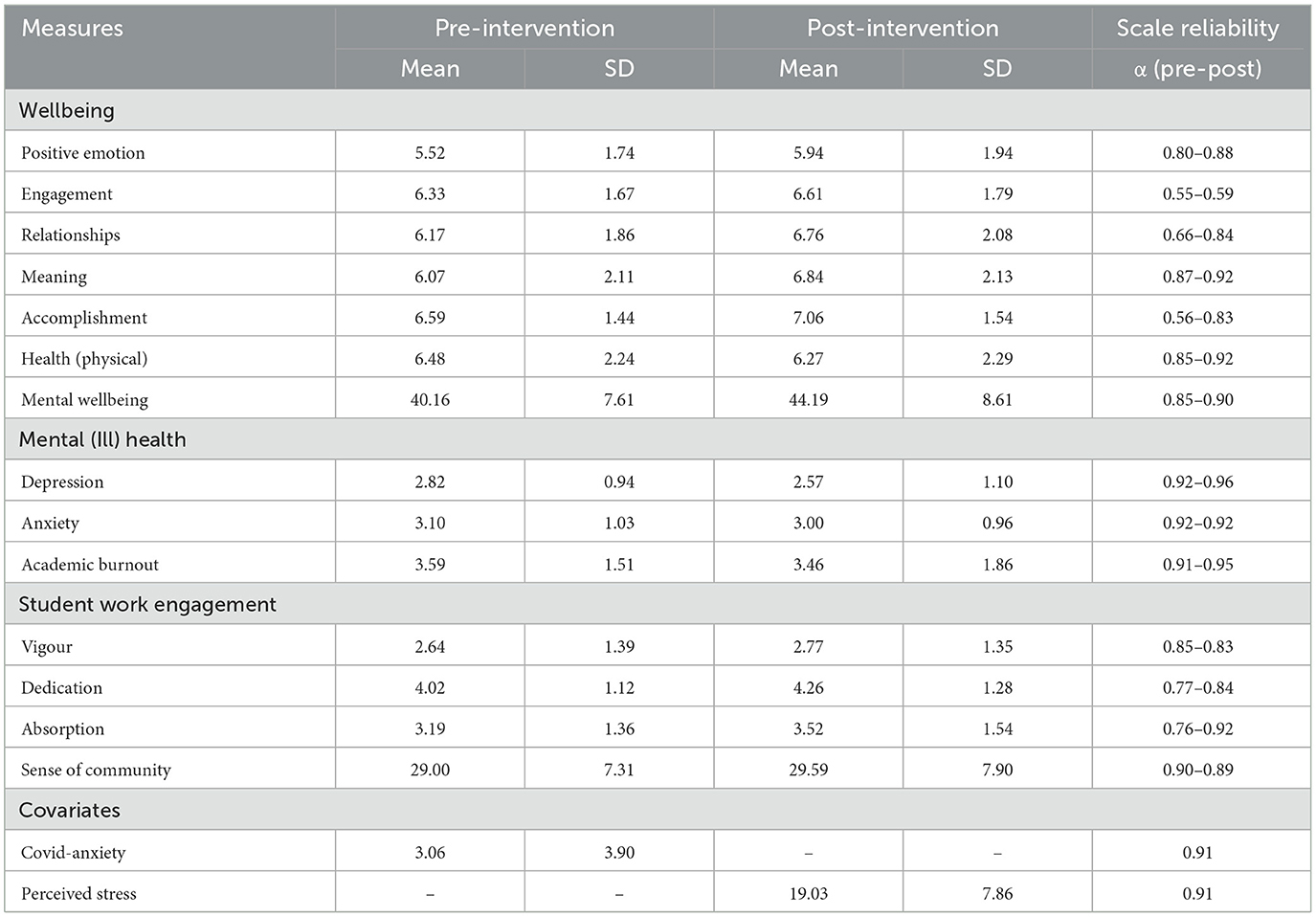

Mean pre- and post-scores across the outcome variables can be seen in Table 3. Scores increased or decreased in the predicted direction for all outcomes except for physical health. The mean number of programme sessions ranged from 3 to 8 with the average number of attended sessions being 6 (M = 6.39, SD = 1.58). The number of wellbeing practises introduced in sessions and continued outside of sessions as “homework” ranged from 0 to 8, with an average of 4 (SD = 2.77). The vast majority of students (97%) indicated that they already engaged in a variety of different wellbeing practises, with the main categories being physical activity, mindfulness/contemplative practises, relaxation techniques and journaling. The number of existing wellbeing practises engaged with ranged from 1 to 7 (per participant), with a mean of 3 (SD = 1.52).

3.1.2. MANCOVA results

Two univariate outliers were observed within the data, both related to extreme scores for COVID-19 Anxiety, however, following further inspection of the data and Q-Q plots, the data was retained for analysis. The dependent variables were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilks > 0.05), with the exception of COVID-19 anxiety pre-scores and post-scores for relationships and academic burnout. As MANCOVAs are robust to normality violations, this was not considered problematic for the validity of the analysis. Following this, a repeated measures MANCOVA examining changes in outcomes measures across the two (pre/post) time-points was conducted. The key covariates of T1 COVID-19 anxiety, T2 perceived stress, number of sessions attended, homework engagement and number of existing wellbeing practises were entered as covariates. A number of significant pre-post differences were observed. For wellbeing, students' levels of positive emotion increased following the Flourish-HE programme [F(1, 26) = 9.52, p = 0.005, = 0.268]; as did their perceptions of positive social relationships [F(1, 26) = 9.39, p = 0.005, = 0.265] and sense of meaning or purpose [F(1, 26) = 4.68, p = 0.04, = 0.153]. Students' levels of engagement, accomplishment, and physical health, as measured by the PERMA-profiler, did not change significantly pre-to-post the programme (p = 0.76; p = 0.17, and p = 0.92, respectively). Students' self-reported levels of overall mental wellbeing were significantly higher following the programme [F(1, 26) = 8.73, p = 0.007, = 0.251]. In relation to mental health, participants' self-reported symptoms of depression significantly decreased across the two time-points [F(1, 26) = 10.38, p = 0.003, = 0.285], however, there was no significant difference in anxiety symptomology (p = 0.44). In terms of academic outcomes, while scores on academic burnout decreased following the programme, the pre-post difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.20). Similarly, there were no significant differences for work engagement in terms of vigour (p = 0.13), dedication (p = 0.54) or absorption (p = 0.34). Students did, however, report a stronger sense of community within the post-programme survey [F(1, 26) = 5.04, p = 0.03, =0.162].

When examining the influence of the key covariates, a significant interaction between number of sessions attended and pre-post differences in positive relationships is observed [F(1, 26) = 5.89, p = 0.022, = 0.185]. Larger pre-post differences were observed when participants attended a greater number of wellbeing sessions. No significant interactions were observed for the number of existing wellbeing practises or homework engagement. There was a significant interaction between pre-post time points, self-reported health scores and pre-test COVID anxiety scores [F(1, 26) = 7.74, p =0.010, =0.229]. Examination of the means demonstrated a tendency for smaller pre-post differences in physical health at higher levels of self-reported COVID anxiety, however, this was not consistent across all participants. There was a significant interaction between pre/post time points, self-reported academic burnout scores and pre-test COVID anxiety scores [F(1, 26) = 4.35, p = 0.047, = 0.143]. Here, larger pre-post differences in academic burnout were observed for median levels of pre-test COVID anxiety, with smaller pre-post differences observed for both higher and lower COVID anxiety scores. An interaction between T2 perceived stress scores, pre-post time points and scores for positive emotion, mental wellness and depression were also observed. An examination of the means revealed larger pre-post increases in positive emotion for students that reported lower levels of perceived stress at T2 [F(1, 26) = 6.101, p = 0.20, = 0.190]; smaller pre-post increases in mental wellness for students who reported more extreme levels of perceived stress at T2 [F(1, 26) = 5.531, p = 0.027, = 0.175] and larger pre-post decreases in depression symptomology for students who reported lower levels of perceived stress at T2 [F(1, 26) = 10.054, p = 0.004, = 0.279]. There was also a significant interaction between T2 perceived stress scores and pre-post differences in positive relationships due to larger pre-post differences in self-reported positive relationships at both higher and lower levels of perceived stress, with lower differences observed for median levels of stress [F(1, 26) = 5.20, p = 0.031, = 0.167]. Such results indicate the importance of considering both T1 COVID anxiety and T2 perceived stress when examining programme effectiveness (we revisit this in the discussion).

3.2. Qualitative findings and integration

Within this section, the qualitative findings are concurrently integrated with the quantitative findings to provide mixed insights into the effectiveness of the Flourish-HE programme. Firstly, the deductive analysis of participants' insights into the effects of the programme are considered with reference to the PERMA-H model. This is followed by a summary of the quantitative and qualitative results, organised around the four study hypotheses. The second part of this section will present the inductive qualitative findings, focusing on the evaluation of perceptions and experiences of the programme.

3.2.1. PERMA-H insights and integration

3.2.1.1. Positive emotions

Participants reported experiencing positive emotions in anticipation of the programme: “It was definitely something that influenced my emotions in that sense that it was something I looked forward to and I felt more positive on Wednesday than I would have done otherwise” (Sofiya). Participants also noted a sense of enjoyment from participating in the programme itself, “I found it [the programme] to be really really enjoyable and there was something to look forward to so each week you know having that it became sort of part of my part of my routine” (Mikka). This also included feeling positive emotions on the day that the programme was delivered, “I felt particularly more positive than the Wednesdays that I had before the programme” (Lucy).

Positive emotions also increased more generally as a result of participating in the programme, with participants recognising when they were feeling these emotions: “I suppose my positive emotions have increased a bit more instead of I suppose how I was before I've definitely learned to recognise positive emotions more and actually go I feel today is a good day” (Katie). This also included directly after a wellbeing session had ended, “I think the day of the sessions I would come out of the sessions, usually feeling more positive and just generally more positive emotions” (Louise). Additionally, participants discussed specific activities that increased their positive emotions during participation in the programme: “when we share like how we felt with photo or photos or memes that was amazing because I was always laughing at other pictures” (Paige). These qualitative findings mirror the self-reported increases in positive emotion following the Flourish-HE programme (p = 0.005) and indicate that positive emotion has been experienced in anticipation of, because of, or during their participation in the programme.

3.2.1.2. Engagement

Whilst self-reported levels of engagement in life increased over the period of the programme (as measured by the PERMA-profiler), these did not did not change significantly pre-to-post the programme (p = 0.76). There were also no significant differences for work engagement in terms of vigour (p = 0.13), dedication (p = 0.54) or absorption (p = 0.34). However, within the interviews participants reported feeling increased engagement as a result of taking part in the wellbeing programme, in addition to feeling engaged in the programme itself.

Participants reported feeling engaged with their daily tasks after completing the wellbeing programme: “I think I'm more focused on what I want to do I think before I could be a bit distracted (especially if I was feeling particularly emotion or feeling an emotion quite strongly that that would sort of takeover) but I'm now able to say but I really need to focus on this today this is my task this is what I'm getting done so I'm definitely much more focused now I can definitely crack on and get that done” (Katie).

Participants also discussed taking part in additional wellbeing practises as a result of participating in the programme. The number of wellbeing practises introduced in sessions and continued outside of sessions as “homework” ranged from 0 to 8, with an average of 4 (SD = 2.77). This was further discussed in the follow-up interviews, where participants reported feeling engaged with the wellbeing programme itself: “I think after one of the sessions where we talked about empathy and supporting the people in our lives. I think I made a mental note to go away and do that, and maybe for the week after I might have tried to implement those” (Louise). Some participants also continued to practise activities that were provided in the session, “I was never doing meditation and mindfulness exercises before but after this session I started it and honestly I'm like doing it every day since that day” (Paige).

Participants' responses indicated how the programme provided opportunities to explore wellbeing and enhance their knowledge and awareness of wellbeing practises: “I learned a lot of things I didn't know just in terms of ways to improve your wellbeing so there's certain things that I did anyway kind of like the physical exercise side of things mainly but the session on meditation was really informative to me because that's not something I'd particularly done before and something that I found interesting and that I've kind of looked into a bit more since the sessions” (Sofiya).

3.2.1.3. Relationships

The perceptions of positive social relationships increased following the programme (p = 0.005, η2p = 0.265). Within the interviews, participants reported having new outlooks on existing relationships and how the programme helped them to develop new relationships with other programme attendees. This resulted in participants reporting greater connections with others on their course.

Participation in the programme provided a new, positive outlook on existing relationships with family and friends. When speaking about their younger brother, one participant noted that “taking part in the programme has made me sort of step back there and say look here's a 13-year-old boy you know all 13 year olds are like this… it's definitely I think made me look at that relationship a little bit differently it definitely helped us I think we clash maybe a little bit less” (Katie).

When discussing the status of current relationships, another participant noted that “I didn't really have the best relationships because I was never responding to messages…I took it as a chore you know I was just like why do I need to write [to] someone I was just like all over the place... and I told myself I really need to work on this so my personal relationships will get better and it got better because I started to like write [to] my friends I started to call my friends because I was thinking about the fact that they're in the same position as me and maybe they also need me... so maybe they can like cry with me and then be happy so that's why I called them and I started to like engage in my relationships” (Paige).

The programme also helped participants to see the relationships they had and those they could seek support from: “I think when I was stressed or upset it's very easy to think that I was on my own and there was nobody there and again go into that spiral but I think definitely now I can step back and see well actually I've got this lecturer to talk to and I've got this person on the end of the phone” (Katie). When discussing previous support, one participant stated that “back then people were giving me support but I didn't want to take it... now I see it from [a] different light because I see that people really want to help me and they want me to get better so [it] just help[ed] me to change the perspective” (Paige).

A significant interaction between number of sessions attended and pre/post differences in positive relationships was also observed (p = 0.022, = 0.185) and participants reported a stronger sense of community within the post-programme survey (p = 0.03, = 0.162), suggesting that the programme itself fostered and developed positive relationships amongst its members. Participants reported developing connections with staff, students and feeling a general sense of belonginess to the university, through the disclose of personal information during the sessions: “I definitely feel a greater connection with other people on the course Who took part in the world being programme just because of the conversations that I had. In the discussions and seeing a little glimpse at people's lives been locked down, feel greater connection to them, and also [staff who led the programme] and everyone else who was leading the sessions. The familiarity of hearing familiar voices each week… you feel more connected to the people in the sessions” (Louise). When discussing the sessions, participants found the community element useful in developing relationships with others on the programme, “to come to the sessions every Wednesday and have a chat with people we see what was going on definitely felt that there was a little community going on in those sessions” (Katie). Specifically, participants enjoyed the social element of the programme in being able to form relationships with others, “I really enjoyed the social aspect of it [the programme] and being able to relate to other people you know even like sharing like memes and pictures” (Mikka). By developing these connections, participants felt this added to the enjoyment of the programme, “the main thing that I really enjoyed about the programme sort of feeling connected to the university and other students and yourselves as lecturers” (Sofiya).

3.2.1.4. Meaning (or purpose)

A sense of meaning or purpose increased following the programme (p = 0.04, = 0.153). This was further supported by participants who, when discussing their daily life, found they had more purpose and meaning in everyday life: “I think it's made me more focused as I've said which has probably changed how I feel when I wake up about what my purpose of the day is work could either wake up and say right I need to get on with this and I will do it so I feel about during the day I have a purpose” (Katie). This also included an increased sense of motivation, which one participant discussed in relation to motivation to complete their academic work: “it's given me more motivation and like sense of purpose with regards to my repeatedly searching away... it kind of made me feel like motivated and remind me of how much purpose my specific research has and I also think I would say it's given me sort of purpose in my personal life” (Sofiya).

For some participants, this sense of meaning and purpose was connected to their broader personal lives, with one participant stating that, “[Before the programme] I just didn't want to do anything and I literally didn't want to live anymore so I didn't have really like purpose in my life and direction which I want to like go but the programme really helped me because now I feel that I have some purpose and I want to be the best version of myself” (Paige). Meaning and purpose also manifested itself as being connected to something bigger than oneself, for example, a sense of belonging to communities within and outside of the university. In particular, the programme helped to foster a feeling of belonging to a wider community during a period of remote learning: “I definitely feel greater belonging with the course and also the university and even so far as the [university city] community…” (Louise), which resulted in “feel[ing] a greater connection to the people around you in the sense of in the community rather than actual proximity” (Louise), highlighting the ability to feel a sense of belonging throughout an online programme. Participants also reflected on their position in life and their possible contribution towards community and society: “[the programme] resonated with me and I was starting to like think about it and about my life and then I told myself I want to belong somewhere and I want to have the feeling of cohesion with someone or some community” (Paige).

3.2.1.5. Accomplishment

Feelings of accomplishment increased after the completion of the programme, however, this did not change significantly (p = 0.17). Despite this, participants reported feeling better able to achieve their goals. When discussing their academic work, one participant noted that, “I feel that before I might have looked at the mountain of work and gone or class just so much work to do and I've got all of whereas now I'll look at it and go right how can I achieve that goal what do I need to do” (Katie).

When discussing goals and accomplishments, participants discussed their motivation. One participant reported that the programme helped their motivation return: “when it comes to motivation the motivation came back to my life” (Paige). Some participants attributed this to an increase in motivation to push through and persevere with accomplishing goals: “it's definitely helped me to have that motivation and to want things and to keep trying and if something doesn't quite go to plan to say right what else is there if that plan is completely out the question … to think positively and yet to keep going and to keep trying” (Katie). Participants reported that this also had an impact on their productivity and had a particular impact on the work they were conducting on the day of the programme or immediately after: “I feel like I was more productive in my work for the rest of that day and even the week really” (Sofiya).

Accomplishment was also discussed in relation to academic achievements. When discussing their academic work, one participant noted that, “after this other session I also like wrote some goals on my paper which I want to like achieve and it was not like goals like 10 years from now but it was like attainable goals which I can like complete for example in this semester and I was really thinking about it like what can I do and what possibilities are like are out there for me” (Paige). This also had an impact on the overall view of participants' academic experience, with one participant reporting that “my confidence has improved to finish my degree” (Lucy).

3.2.1.6. Health

Students' levels of physical health, as measured by the PERMA-profiler did not change significantly pre-to-post the programme (p = 0.92). However, within the interviews, participants reported feeling fewer physical manifestations of stress in their body after the programme. When discussing physical changes in the body, one participant noted that “there are lots of physical benefits I feel less tense in my body… I can physically relax slow that heart rate down and just breathe for a little bit so that's definitely stopped me from being really tense” (Katie).

Participants also reported engaging in physical activity during and after the wellbeing programme. During the programme, participants reported that they tried new types of physical activity, that were inspired by activities in the wellbeing programme, “I started to do yoga and it was something that I was never doing before because I was also like always like working out and going to the gym... I never thought yoga would be something for me but after this programme and also the mindfulness practises I'm like connecting yoga to exercises when I'm doing it so like I'm stretching my body and also like moving and also putting my mind to ease” (Paige). This also included a general increase in motivation to participate in physical activity with one participant reporting that, “I think while it was ongoing, I felt more motivation to be active, both because of the discussion of particularly things like mental and physical health [..] but in the long run I don't think it [physical health] has improved that much” (Louise). However, amongst participants there was a consensus that the overall physical health of individuals had not changed during the pandemic: “Yeah I can't really see a change in my physical health” (Lucy).

3.2.1.7. Undoing effect and coping

Participants' self-reported symptoms of depression significantly decreased across the two time points (p = 0.003, = 0.285). However, there was no significant difference in anxiety symptomology (p = 0.44). As a result of the wellbeing programme, participants reported that they felt better able to cope with stressors they experienced: “how I probably dealt with stress beforehand probably wasn't very productive I'd probably let it build up to the point where I couldn't really do much so actually going through the programme sort of allowed me to deal with that stress much in a much more productive way” (Katie).

Participants also reported an undoing effect, where experiencing positive emotions helps to relieve negative emotions (Fredrickson and Levenson, 1998). For participants, the wellbeing programme allowed them to recognise their negative emotions: “my negative emotions have decreased even if I am experiencing them I can acknowledge them and then I can move on so I don't dwell on them” (Katie). The programme itself also served as an undoing effect, with participants reporting that, “they [the sessions] alleviate some of those negative feelings like loneliness or hopelessness or confusion” (Louise). Participants also discussed the reframing of their negative emotions was a useful way to maintain their wellbeing: “I was always focusing on the negative things like when I went out I was just like oh why is it so cold or or why is it raining and now I'm taking all these things even if they have negative nature as positive ones so I always talk to myself that like oh look maybe it's cold but at least it's not hot and you're not sweating or something like that” (Paige).

These results provide evidence for students' wellbeing, as gauged by the six facets of PERMA-H, increasing following participation in Flourish-HE. Despite non-significant quantitative changes across some of the PERMA-H facets and mental health outcomes (such as engagement, accomplishment and academic burnout), participants' qualitative discussions of their experiences suggest that the programme may have positively impacted their engagement in university life, goal setting and management of academic pressures. See Table 4 for a summary of the quantitative and qualitative findings with reference to the study hypotheses.

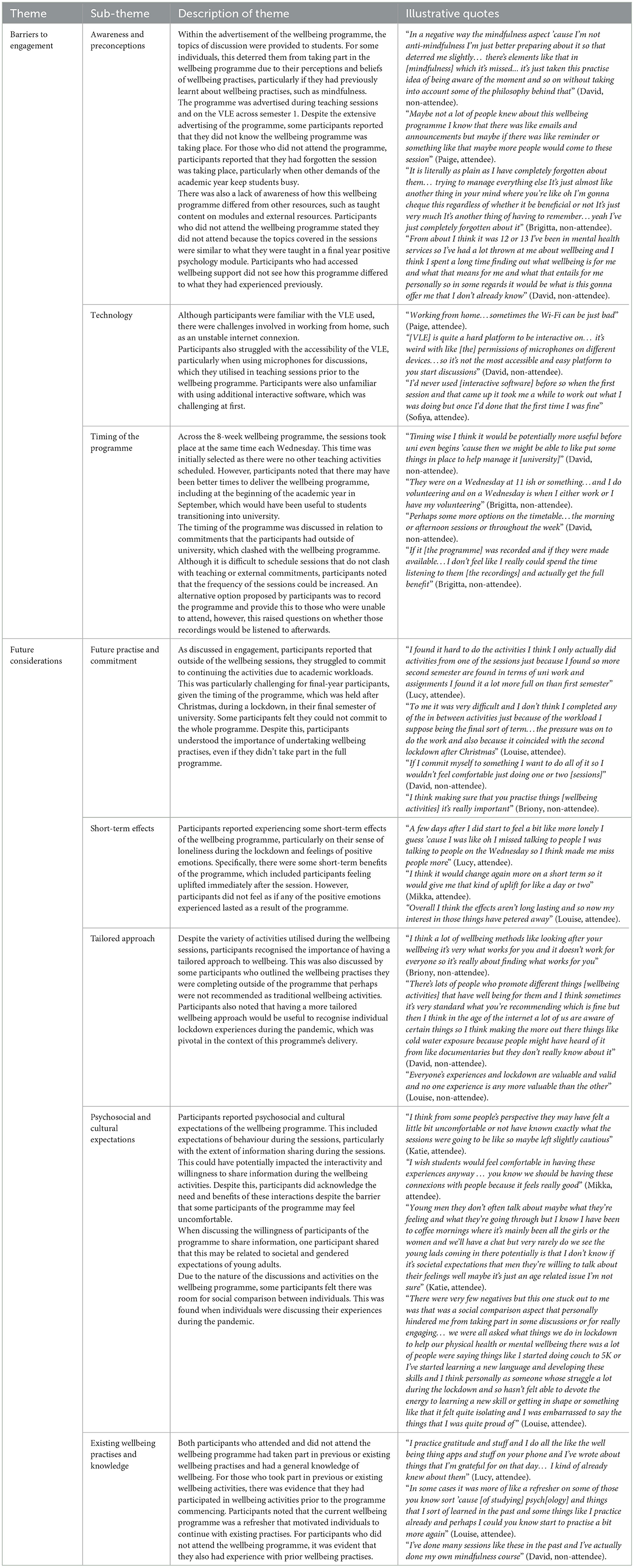

3.2.2. Evaluation of perceptions and experiences of the programme

The qualitative interview questions that explored students' experiences and perceptions of the Flourish-HE programme were analysed inductively using thematic analysis. Two overarching themes were found: barriers to engagement and future considerations. Programme attendees and non-attendees identified a number of barriers to engagement in the programme, which included negative programme perceptions and beliefs, awareness of the programme, technology, and timing of the programme (see Table 5). Participants' also indicated a range of future considerations for programme development. The themes identified here were future practise and commitment, short-term effects, tailored approach, psychosocial and cultural expectations and existing wellbeing practises and knowledge. Please see Table 5 for a description of these qualitative themes and illustrative quotes.

4. Discussion

Flourish-HE is a multi-faceted wellbeing programme that aims to enhance university students' emotional, psychological, social and physical wellbeing through the promotion of the PERMAH pillars of wellbeing. Through the promotion of PERMAH wellbeing facets, the programme further aimed to alleviate symptoms of mental ill health and enhance academic work engagement and a sense of course community. The effectiveness of the programme was evaluated using a mixed (QUANT-QUAL) explanatory sequential design and comprised an online survey to track pre-post changes in programme outcomes and follow up interviews for more detailed insights into experiences and changes across the programme.

The integration of results suggests that Flourish-HE demonstrated an ability to increase positive emotions within participating students. Participants evidenced significantly increased levels of positive emotion pre-to-post programme participation (as measured by the PERMA-H profiler) and, qualitatively, participants reported experiencing positive emotions during and after the sessions as a result of programme activities and through anticipation of upcoming sessions. Participants' interview responses signalled how the sessions generated positive emotions such as joy, amusement, interest and hope, mirroring previous findings that simple activities can prompt immediate boosts in hedonia (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky, 2006). However, several participants noted that these uplifts were temporary and faded over time—thereby suggesting that these boosts may not be sustainable over the longer term without additional practise. Such a limitation had been anticipated and informed our rationale for including evidence-based “homework” activities for participants to complete in-between the weekly sessions. Indeed, other larger-scale wellbeing evaluations have found a significant positive impact of adherence to between-session wellbeing practises on the magnitude and longevity of wellbeing outcomes (Seligman et al., 2005; Lyubomirsky et al., 2011). Despite this, not all participants in the current study undertook these homework activities and there was no evidence for an interaction between homework engagement and wellbeing outcomes. This is likely due to the sample size and large variation in self-reported engagement in homework activities. Encouraging greater independent practise of positive-emotion-inducing activities amongst participants may therefore be a useful design consideration for future iterations of Flourish-HE and similar wellbeing programmes.

Engagement was one of the PERMA-H facets which saw no significant quantitative change pre-to-post programme participation. Relatedly, there were no significant changes observed in the specific measure of academic work engagement. This may have been due, in part, to the nature of the programme being voluntary and self-selective. As such, the sub-group of students recruited as participants may have had higher motivation and a greater readiness to actively and purposefully engage in practises which they deemed beneficial to both their life and/or academic goals (for example by being at the “Preparation” or “Action” stages of behaviour change (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983). This is also indicated by the high percentage of participants who were already completing their own wellbeing practises. Additionally, the programme took place within the second semester of the academic year, a time-point when students typically may be more absorbed in, and dedicated to their studies, thus, participating students may have already had higher than average levels of engagement in life and work at the outset of the programme. It should also be noted here that low reliability scores were observed for the Engagement facet of the PERMA-profiler (see Table 4). Specifically, the question related to “excitement about and interest in things”, could be argued to have prompted participants to consider their positive emotion levels rather than their present-moment attentional focus in everyday activities. Overlap between PERMA-H facets also posed challenges for the qualitative analysis, where the researchers noted difficulties in discretely coding responses to single PERMA-H facets. For example, engagement in work has been conceptualised and quantitatively measured as involving interest and pride (Simpson, 2009). However, interest and pride are also considered to be positive emotions (Fredrickson, 1998) and a sense of accomplishment in academic settings can generate feelings of pride (Seifert et al., 2022).

The phrasing of PERMA-profiler items may also help to explain the lack of pre-post changes in Accomplishment. Kern (2022) suggests that there are two ways of defining accomplishment—objectively and subjectively. Whilst the former comprises tangible outputs and socially recognised accolades, the latter concerns perceived competence, perseverance and the process of actively working towards goals. The questions within the PERMA-profiler are arguably more aligned with the objective definition of accomplishment. Given that post-programme measures were taken midway through the academic semester (where module grades and awards were still unknown), it is possible that participating students may not have perceived any noticeable changes in objective achievement during the 8-week programme. There is evidence from the qualitative interviews that participants did observe changes in subjective achievement, reporting increases in self-efficacy, productivity and perseverance which the quantitative measure did not detect. This may suggest that an alternative scale for measuring accomplishment in future evaluations could be beneficial.

With regard to the PERMA-H facet of Relationships, participants reported having a new outlook on existing relationships and being able to identify where they could seek support or improve their social support network. Moreover, the programme itself also promoted positive relationships and connexions between staff and students. Such strengthening of relationships between student peers and between students and staff has also been observed as a result of PERMA-based interventions in educational settings, albeit with younger pupils, and has been cited as an important factor in explaining increases in perceived flourishing of participating students (Leskisenoja and Uusiautti, 2017). In addition, significant interaction between number of sessions attended and pre/post differences in positive relationships was observed, suggesting that greater participation in the programme supported the development of these positive connexions with peers and university staff. As noted elsewhere, improvements in one facet of wellbeing may promote associated gains in others (Seligman, 2011; Butler and Kern, 2016), and it is likely here that the stronger social connexions to peers and staff outlined above will have also contributed to self-reported increases in meaning, sense of belonging and community. There is, therefore, an argument for bolstering elements of wellbeing programmes which foster both relationships and improved sense of community for participants and which can facilitate participants broadening their sense of belonging to communities beyond the programme and the university.

Self-reported levels of physical health decreased (non-significantly) over the course of the wellbeing programme. As the health-related items in the PERMA-profiler ask about general/overall physical health, it is not possible to decipher these findings further. It is clear from the interview responses, however, that participants primarily focused on physical activity when prompted to consider their physical health. To gain deeper insights into any changes in physical health as a result of wellbeing programmes, researchers may consider measurement tools that prompt participants to separately consider physical vitality, sleep, diet and so forth. Any non-significant decreases in physical health here may be a result of more realistic perceptions of their health (following programme content) and/or due to an increase in unhealthy behaviours across the academic term (e.g., related to increases in stress/academic pressures). It is also worth noting that the period of evaluation for the Flourish-HE programme coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and, while no national lockdowns took place over the evaluation period, students' may have been paying more attention to different aspects of physical health, such as symptoms of illness, during this period. It is also possible that participants were primarily focused on physical safety rather than physical vitality during this time, and the sociocultural climate limited pre-post changes to physical health. As noted in earlier sections of this paper, the pandemic has presented university students with a range of challenges, for example, exacerbating sleep problems and heightening depressive symptomology (Lanza et al., 2022; Valenzuela et al., 2022). This likely means that the baseline from which students were working from, and the wellbeing challenges they were trying to overcome, may not be reflective of a typical academic year. It is possible, therefore, that the context in which this programme and evaluation were delivered may have dampened the prospective gains associated with the Flourish-HE programme. Future evaluations of the programme will be needed to examine this possibility further.

In terms of mental health, self-reported symptoms of depression decreased following Flourish-HE. The inductive analysis on additional wellbeing themes indicates this may be due to feeling better able to cope with adversity and experiencing an “undoing effect”, where the experience of positive emotions helped to relieve negative emotions. The “undoing hypothesis” (Fredrickson and Levenson, 1998; Fredrickson et al., 2000) suggests that positive emotions may function as a resource that individuals can draw on to regulate and manage negative emotions, such as threats and stress. It is possible that the reduction in depressive symptoms noticed here is due to dedicated sessions on, and explicit attention paid to, positive emotions such as gratitude, hope and optimism. Gratitude and hope have been conceptualised (at least in part) as positive emotions (Fredrickson et al., 2000; Tsang, 2006), and positive psychology practises linked to gratitude and hope (e.g., gratitude lists and “best possible selves” exercises) have been shown to reduce depressive symptomology (Cheavens et al., 2006; Carrillo et al., 2019; Dickens, 2019; Cregg and Cheavens, 2021), including in university samples (Tolcher et al., 2022). A recent meta-analysis demonstrates that while positive emotion practises, such as gratitude lists, have evidenced a small but significant impact on depression they have a more limited effect on anxiety (Cregg and Cheavens, 2021). Mirroring this, while the current study offers evidence of decreasing depressive symptoms in students, there were no pre-post differences observed for self-reported symptoms of anxiety. Such findings indicate the importance of wellbeing programmes feeding into more formalised modes of mental health support within HEIs.

No pre-post differences in academic burnout were observed in the quantitative data, despite the underpinning positive education ethos which suggests that enhancing wellbeing skills can support students' learning. One possible explanation for this is regarding the timing of the 8-week programme: pre-test measures were completed early in the teaching semester (2–3 weeks into teaching), at a point where academic pressures around assignments and grades can be assumed to be at a lower level. In comparison, post-test measures were completed nine-to-ten weeks later at a point where assessment deadlines were looming. It is possible, therefore, that pre-post changes in academic burnout are confounded by levels of academic pressure. It is notable that, while no decrease in academic burnout is observed pre-post the programme, there is no increase in academic burnout scores either. It is possible, therefore, that the programme helped to maintain lower levels of academic burnout across the semester—but, without a comparable control group, we cannot make any clear assumptions here. We do observe from the qualitative interviews, however, that students reported that the programme helped them to deal with academic stress. In recognition of increasing academic pressures across the semester, perceived stress during post-survey completion was measured and analysed as a covariate in analysis. Perceived stress scores influenced many of our pre-post comparisons, with high levels of perceived stress appearing to dampen the effects of the wellbeing programme. This is perhaps unsurprising as it is well-documented in the literature that HE students experience several sources of academic and personal stress throughout the academic year, such as workload, time management, assessment and financial pressures (Pitt et al., 2017). Researchers should similarly consider controlling for post-phase, or pre-to-post changes, in stress levels within wellbeing programmes and interventions that are conducted within academic contexts.