95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 14 April 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1123586

This article is part of the Research Topic Trauma-Informed Education View all 11 articles

Introduction: In remote education settings in Australia, experienced teachers who can effectively support students impacted by trauma are essential. Remote communities are unique yet are in many ways vulnerable to trauma as they face higher rates of disadvantage and exposure to traumatic events, including natural disasters and domestic and family violence. This is compounded by a lack of access to effective supports due to the tyranny of distance. Also, First Nations peoples living in remote areas continue to endure the ongoing and traumatic impacts of a violent and disruptive colonization.

Methods: The qualitative research study detailed in this article explored the requirements for the work of experienced, trauma-informed teachers in remote Australia to be effective, adding an important and unique perspective to the research evidence that is not often considered. Seven teachers from remote Australia completed a short, online questionnaire and participated in a focus group interview which was analyzed thematically.

Results: Themes emerging from the focus group data indicated that specific and contextualized preparation and support for teachers is required for them to do their work effectively. For remote Australian settings this means preparing teachers with cultural awareness and relevant trauma-informed training. Further, the wellbeing of these remote educators is often compromised, and addressing systemic factors such as adequate preparation of their colleagues and support to access relevant ongoing professional learning is needed.

Discussion: Remote teaching work in Australia is complex, and while the current study is small and exploratory in nature, the findings highlight some of the real-world impacts of these issues at a community and individual teacher level that have not been previously explored.

In Australia, many terms are used to define ‘remote,’ for example ‘the bush,’ ‘outback,’ ‘the sticks,’ and ‘isolated’ (Roberts and Guenther, 2021). Remote communities are each unique according to geography, history, culture, and customs. Yet all require well prepared, experienced, and resilient teachers (Perso and Hayward, 2015). However, teachers working in remote communities can experience additional challenges not faced by their metropolitan counterparts and often need further preparation. All teachers need to balance the delivery of a “crowded curriculum” with meeting individual students’ personal and educational needs (Crump, 2005, p. 31). However, teachers in remote schools are also working with students who are more often socio-economically disadvantaged and who experience higher rates of trauma than students in metropolitan areas. This can be due to greater exposure to domestic and family violence, greater direct experience of natural disasters, and higher rates of involvement with child protection services (Mitchell et al., 2013; Roufeil et al., 2014; Goodridge and Marciniuk, 2016; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2022a). This can also be due to students facing additional challenges associated with their having limited access to support services in their communities, requiring that they rely more often on teachers and schools for support (Evans et al., 2008; Caringi et al., 2015; Chafouleas et al., 2016). Students who have experienced trauma can display challenging behaviors which can impact on the learning of other students and the teacher’s ability to support and educate (Porche et al., 2011; Howard, 2013; Ban and Oh, 2016; Brunzell et al., 2016; Berger et al., 2021). If teachers are not trained in trauma-informed practices, they may misinterpret these behaviors as being deliberate disobedience and might respond in ways that can reinforce the trauma and disadvantage suffered by students in remote areas (Goodman et al., 2012; Howard, 2013; Bonk, 2016).

Since the 1980s, there has been a plethora of research, both in Australia and internationally, that has focused on the preparation of pre-service teachers and the retainment of early career teachers in remote schools (Barker and Beckner, 1985; Yarrow et al., 1999; Hudson and Hudson, 2008; Lassig et al., 2015; Papatraianou et al., 2018). Unlike pre-service and early career teachers (White, 2019; Hudson et al., 2020), there is not the plenitude of research examining experienced teachers who work in remote settings and there is certainly a dearth of research examining experienced teachers who are also trauma-informed.

There is also a lack of consistency in the research literature regarding definitions of what constitutes an experienced teacher, and no clear definitions are provided for what constitutes an experienced, trauma-informed teacher (Graham et al., 2020). Therefore, for the purposes of this research, two definitions were adopted to help frame data collection and analysis. Experienced teachers are defined as those who have more than 6 years of teaching experience (Akbari and Tajik, 2009) and trauma-informed teachers are those who realize the impact of trauma, recognize the symptoms of trauma in their students and community, and respond by applying their understandings through practices to reduce re-traumatization (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014; Maynard et al., 2019). These teachers also have a deep understanding of the skills and knowledge they bring to their teaching and how their own experiences, skills, and behaviors influence how they respond to childhood trauma in the context of their work (Champine et al., 2022). The participants in this study met the requirements of both definitions and all had experience working in remote schooling.

In general, teachers working in remote schools face challenges not encountered by their urban and metropolitan counterparts. As an example, remote teachers face tensions associated with social proximity and a lack of privacy, which can be referred to as “living in a fishbowl” (Karlberg-Granlund, 2019, p. 297). Also, there can be substantial expectations placed upon them by their local communities (Pavlic-Roseberry and Donne, 2022). Remote teachers are often trying to meet both the demands of the communities in which they live and “the upward accountability environment of the system” in which they work (Guenther et al., 2016, p. 47). This “upward accountability” often requires that those who have more experience than others be given greater work responsibilities whereby they are required to “wear many hats within the school” (Trikoilis and Papanastasiou, 2021, p. 4). This can also be exacerbated by insufficient staffing, another quite common occurrence in remote areas. Teachers can also be required to take on leadership positions in their schools despite their having limited or no training to prepare them for these roles (Jarzabkowski, 2003; Jenkins et al., 2011). Also, they may have limited opportunity to learn from and work collaboratively with other experienced leaders from other schools (Nordholm et al., 2022). Experienced teachers who are also trauma-informed may be working with other staff members who are not ready to become trauma-informed due to personal biases and not understanding the need for trauma-informed practices or not being aware of the prevalence or impact of trauma in their communities (Wassink-deStigter et al., 2022). This can present challenges for teachers in remote schools to find a balance between work demands and maintaining their personal wellbeing (Karlberg-Granlund, 2019) and for them to lead and implement trauma-informed work in an effective manner. It is important to explore the requirements for the work of remote, experienced, and trauma-informed teachers to be effective, whilst also considering the personal and professional well-being of these teachers.

Attracting and retaining teachers to rural and remote communities has been an ongoing challenge for education systems in Australia (Hasley, 2018). To address this, Australian state and territory governments and education systems have undertaken different approaches to attract and retain teachers (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2018). Examples include education systems collaborating with universities to provide professional experience opportunities for pre-service teachers, school leaders and experienced remote school teachers participate in teacher recruitment roadshows and fairs, financial incentives (subsidized rent, relocation allowance, increase pay), extra leave, and study leave incentives (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2018; Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). Despite these incentives, it is often early career teachers being placed in rural and remote communities in the first years of their careers (Carroll et al., 2022). The most current collective data suggests that 30% of teachers in Australia work in rural and remote schools (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2021), and 26% of these teachers are in their first 5 years of teaching (Freeman et al., 2014). Many teachers who work in remote settings are “unable to cope with the reality of the experience” (Perso and Hayward, 2015, p. 201) due to conditions including isolation and a lack of services, teaching multi-age classes, responding to the behavior of students, teaching high proportions of students who live with a disability, and teachers having a general lack of cultural awareness (Lock et al., 2012; Kline et al., 2013; Willis et al., 2017). Many of these teachers have grown up in cities and towns and attended metropolitan schools and universities and therefore have not experienced the cultural and linguistic diversity of remote Australia and need significant and informed support to transition well to teaching in a remote setting (Brasche and Harrington, 2012; Disbray, 2016; Willis et al., 2017; Commonwealth of Australia, 2020).

When teachers first arrive in a remote setting, they may experience “culture shock” (Oberg, 1960; Adler, 1975; Muecke et al., 2011; Irving et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2022). This may occur when students and parents bring “community and cultural values into the classroom” (Eady et al., 2021, p. 214) that are vastly different to the teacher’s own cultural background. Thus, it is important that teachers new to remote areas are culturally aware (Foley and Howell, 2017; Biddle et al., 2018; Wilks et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2022). In Australia, people identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander consist of 3.3% of the Australian population yet comprise 32% of the population in remote communities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2022b). So, an important part of being culturally aware is for teachers to understand Australia’s history from Indigenous perspectives, including a thorough awareness of the effects of colonization, dispossession, assimilation, and the impact of the Stolen Generations in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were “forcibly separated from their families and communities since the very first days of the European occupation of Australia” (Wilson, 1997, p. 22). This severe and tragic disruption led to the destabilization and sometimes destruction of traditional family units in remote communities which in many cases, resulted in intergenerational trauma (Menzies, 2019). Intergenerational trauma is defined as the secondary impact of trauma that is passed down through generations and which has a damaging impact on family systems (Raphael et al., 1998; Cromer et al., 2018). Therefore, it is also essential that teachers new to remote settings are aware of the history, needs, and strengths of the local community in which they work. These variables make addressing trauma in remote communities “complex and multilayered” (Kreitzer et al., 2016, p. 50) and further highlight the need for teachers working in these settings to be culturally aware and trauma-informed.

To be eligible for teacher registration in Australia, an initial teacher education degree must be completed. This university qualification is offered through different programs of study (e.g., 4 year Bachelor Education or 2 year Master of Teacher (post-graduate) majoring in either early childhood education, primary, or secondary education). Options for study typically include online or internal delivery (or a combination of both), and service a variety of different student populations (undergraduates, post graduates, international students, and mature age students) to meet the different job market needs (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2023). Due to the differing contexts, making comparisons between the different providers and modes of study is unable to be made (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2023). However, the research to date suggests that many teachers have not received training in cultural awareness of trauma-informed practices and are currently unaware of how childhood trauma can impact on student education and wellbeing (Brunzell et al., 2021).

University education in trauma-informed practice can increase favorable attitudes and knowledge of preservice teachers in this area (Brown et al., 2020; L’Estrange and Howard, 2022) but this is not available in all initial teacher education programs in Australia. Also, once working in schools, it is important for teachers to receive ongoing training as this can increase confidence and teacher emotional self-regulation for when they need to manage any challenging behaviors of trauma-impacted students (Stokes and Brunzell, 2019; Berger et al., 2021). It is unfortunate that accessing professional development opportunities in remote settings can be limited due to the tyranny of distance impacting the availability of face-to-face training and complexities with internet provision for on-line training (Dorman et al., 2015; Carroll et al., 2022). Perso and Hayward (2015, p. 202) suggest that due to the complexities of teaching in remote settings, it is “almost impossible to fully prepare someone for the job of teaching in a remote school,” suggesting that teachers working in a remote setting also need to be quite resilient (Papatraianou et al., 2018; Willis and Grainger, 2020).

Unfortunately, there can also be a disconnect between teacher preparation and the knowledge, skills, and cultural awareness that is needed for teachers in remote areas to do their work in an informed and effective manner (Lock et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2021). Another critical area of preparation that can sometimes be lacking, is cultural awareness training. A lack of cultural awareness training can lead to deficit discourses being accepted by teachers and being directed at students, family, community, and school personnel (Auld et al., 2016; Stacey, 2022). Teachers may have insufficient knowledge and skills to teach in a culturally responsive way, with many not having accessed Indigenous studies at all during their initial teacher education (Llewellyn et al., 2018; Vass et al., 2019; Willis and Grainger, 2020) and few may have received any form of professional training in cultural awareness and culturally appropriate education practice since commencing their careers (Lock et al., 2012). It is clear that teachers require more consistent training and support for them to work safely and competently with Indigenous students who are impacted by trauma (Australian Government, Department of Employment, Education and Training, 2020). To be effective, cultural awareness training needs to be specific to the unique histories, attributes, and needs of individual communities and should be designed to adequately prepare teachers to respond well to the contextual issues that they may face (Lock et al., 2012). It is important that this training includes knowledge and skill development to support students impacted by trauma, and the health and wellbeing issues that can be experienced by students (Lock et al., 2012). Part of cultural awareness involves teachers knowing how to connect with community and understanding the culture and home lives of students, including any trauma that may have been experienced (Eady et al., 2021). Therefore, to support and educate their students well, teachers in remote areas need cultural awareness training that also includes training in trauma-informed practices (Brown et al., 2020; Willis and Grainger, 2020).

Teaching can be a demanding profession and consequently, teachers can be vulnerable to stress. This is particularly relevant for those who work with students impacted by trauma (Spilt et al., 2011; Borntrager et al., 2012; Lever et al., 2017; Koenig et al., 2018; Berger et al., 2021; Brunzell et al., 2021). Intense and ongoing stress can lead to compassion fatigue, which is defined as “the natural, consequent behaviors and emotions from knowing about trauma experienced by a significant other – the stress resulting from helping or wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person” (Figley, 1993 as cited in Figley, 1995, p. 7). Hearing student’s experiences can bring back teachers’ own memories of trauma and this may impact on their teaching capacities (Caringi et al., 2015; Wassink-deStigter et al., 2022). Teachers experience a higher rate of compassion fatigue than many other related professions and report greater levels of secondary traumatic stress even though stating as having job satisfaction at comparable levels to other helping occupations (Brunzell et al., 2021). Compassion fatigue is acute for teachers working in low socio economic and remote communities due to the high numbers of students with whom they work who have been exposed to trauma that includes community and family violence (Lever et al., 2017). Teachers in Australia’s remote areas have higher levels of stress compared to those who teach in urban areas with early career teachers experiencing the highest rate of stress compared to those who are experienced teachers and those who are late in their career (Lock et al., 2012; Carroll et al., 2022). There are several factors that contribute to this prominent level of stress experienced by teachers in remote schools. These include the impacts of under-staffing, the expectation that teachers act in many and diverse roles to address staffing needs, limited access to resources and support, teachers experiencing personal and professional isolation (Carroll et al., 2022), and working long hours because of the professional and social expectations of visibility and contact with the community (Eacott et al., 2021). Thus, “boundaries between professional and personal life are frequently blurred” (Eacott et al., 2021, p. 19). High levels of teacher stress can impact on the stress experienced by students which, in turn, can impact on student learning and well-being outcomes if not addressed (Lever et al., 2017).

Thus, the work of teachers can be described as “emotionally intense” (Heffernan et al., 2022, p. 1) as teachers are sensitive to the challenges that students experience (Townsend et al., 2022). Part of this emotional intensity includes teachers becoming frustrated with colleagues who have a lack of experience with and knowledge of how to support students who exhibit challenging behaviors (Caringi et al., 2015). Facing these difficulties, teachers are required to continue to do their work while evading compassion fatigue (Essary et al., 2020) and despite these difficulties, many teachers stay in the profession as they feel a sense of responsibility to students (Essary et al., 2020).

With this in mind, there is now an imperative for education systems to recognize the prevalence and impact of trauma in student populations in remote areas and to respond by supporting teachers in remote areas to do their work effectively with students impacted by trauma (Keane and Evans, 2022). This can be achieved by teachers being trauma-informed, which means teachers understand the type and prevalence of adverse experiences amongst students, recognize the impact these experiences can have, and ensure that school is not a place of re-traumatization (Bellamy et al., 2022). Thankfully, there are some highly experienced and dedicated, trauma-informed people working in remote schools who recognize the impact of trauma on students and communities and who are advocating for the consistent implementation of trauma-informed practices in schools (Brown et al., 2022). With appropriate support, the work of these teachers will be nurtured and enhanced, and the numbers of these teachers will grow.

There is growing research on teachers’ experiences associated with working with students impacted by trauma (Barrett and Berger, 2021; Brunzell et al., 2021; Miller and Berger, 2022) but there is a lack of research focusing on the experiences of highly trained trauma-informed teachers, particularly those who are working in remote settings. It is this lack of research that has prompted this current study. In this study, highly experienced (more than 6 years teaching), highly trained trauma-informed teachers are defined as teachers who have undertaken training in trauma-informed education practice during post graduate studies at a tertiary institution as well as accessing a range of professional development within the school system. This study aimed to answer the following research question: What is required for the work of experienced trauma-informed teachers in remote settings to be effective?

Participants in this qualitative study included five female teachers and two male teachers with a mean age range of 30–39 years. Participants had been teaching for up to 20 years, averaging 11–15 years of working in remote schools. A remote school is defined as a school located in a very remote or remote area as identified by the Australian Bureau of Statistics which use the Accessibility/Remoteness of Australia (ARIA+) to define remoteness via a geographic measure of distance from the nearest service center (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023). The further the distance from a service center, the more remote the location (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Half of the participants had been working in their current remote schools for 3–5 years and the other half were within their first 2 years at their current schools. The participants’ professional roles included one deputy principal, one senior teacher of inclusion, one head of department, one head of learning, two secondary teachers, and one student support officer. All participants worked in secondary schools (students aged 13–18 years) in remote areas across Australia: four in Queensland, one in the Northern Territory, one in New South Wales, and one in Western Australia.

Participants were recruited through their engagement in one of two post-graduate university courses focusing on trauma-informed education in which they were enrolled during 2021. These courses (a Graduate Certificate, or Masters degree in Education) were both offered at the same university and could be studied online or internally. The trauma-informed education component of each course was similar and included an introduction to trauma-informed education, understanding adverse childhood experiences, the neurobiology of trauma, learner groups affected by trauma and leading trauma-informed education. Participants were recruited immediately after the completion of their university studies and data was collected within 2 months. To be eligible for participation in the study, participants needed to be currently working in a remote school or to have worked in a remote school within the previous 18 months. Participants also needed to be experienced (greater than 6 years teaching) and highly trained in trauma-informed practice (completion of post graduate training). Due to the specific sample required, a snowball sampling approach was also included. Snowball sampling is a method in which participants for a study are asked by researchers to recommend individuals as future participants (Crouse and Lowe, 2018). For this study, participants shared the recruitment information with their networks. Of the seven participants, six were recruited through the university and one was recruited through snowball sampling.

The participant numbers in this study are small as finding experienced, trauma-informed teachers was a challenge as they are understandably a minority within the broader group of remote school teachers in Australia (and this group is in its entirety is only a small percentage of Australian teachers). The Australian Teacher Workforce Data Teacher Survey 2018–2020 reported there are approximately 2% (n = 418) of classroom teachers in remote or very remote schools compared to 66% (n = 11,061) of classroom teachers in major cities (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2022). Despite the small number, the study was able to take a “deep dive” into the lived experiences of these experienced remote teachers which adds valuable findings to the growing evidence base of trauma-informed practices in schools.

To understand what experienced trauma-informed teachers who work in remote settings need for their work to be effective, participants answered a short online questionnaire and participated in an online focus group interview. Approval to research was granted by a university Ethics Review Committee. Invitations to participate in the research were emailed to people who were enrolled in the post graduate trauma-informed education courses. Participants contacted the first author to express interest in the study, and after receiving the project information sheet and providing written consent, they completed a short, online questionnaire. The questionnaire required for them to provide information about (1) their time working as a teacher; (2) their current employment location; (3) the length of time that they had worked in current remote setting; (4) their main role within the school; (5) the state or territory in which they currently work; (6) any professional learning that they had accessed in the previous 12 months; and (7) their perceived level of professional and personal wellbeing.

A focus group interview was conducted after all participants had completed the questionnaire. Focus group interview questions were informed by questionnaire responses and focused on teachers’: (1) confidence for working with students impacted by trauma; (2) years working in remote school/s; (3) reflections regarding their professional development and formal training in trauma-informed practices; (4) perceived level of wellbeing; and (5) recommendations to meet the needs of teachers in remote areas to work effectively with students living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. These primary areas of questioning were explored using open-ended questions, with additional probing questions being used as required and according to participant responses. Examples of prompts or questions that were used included: “Summarize your experience of working with students impacted by complex childhood trauma,” “How confident are you when doing this work?” and “Has working with students living with the effects of complex childhood trauma impacted on your personal and/or professional wellbeing and if so, how?” The focus group interview was of approximately 100 min duration, was facilitated by the first author, was audio recorded and professionally transcribed. All responses were de-identified.

Based on the exploratory nature of this study, a qualitative research design using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was used. This study was exploratory due to limited research literature available that discusses the experiences of highly trained, trauma-informed teachers or teachers working in remote settings who teach students living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Focus group interview data were analyzed, and themes were generated. The analysis was conducted in several stages as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 87): “familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, search for themes, reviewing the themes, defining, and naming themes, producing the report, and selecting appropriate examples to illustrate the themes.” The analysis was not a linear procedure, it was an iterative and in-depth reflexive process.

The first step in the thematic analysis involved the first author of this article reading and re-reading the interview data and manually coding these into segments of recurring ideas. Themes were then generated by the first author into overarching and subsequent themes. The second author of this article independently analyzed the data and then consulted with each other regarding the potential themes and subsequent themes. The authors then collaborated on the final set of themes and subsequent themes and consensus on the themes was reached through dialogue. Three overarching themes emerged from this process.

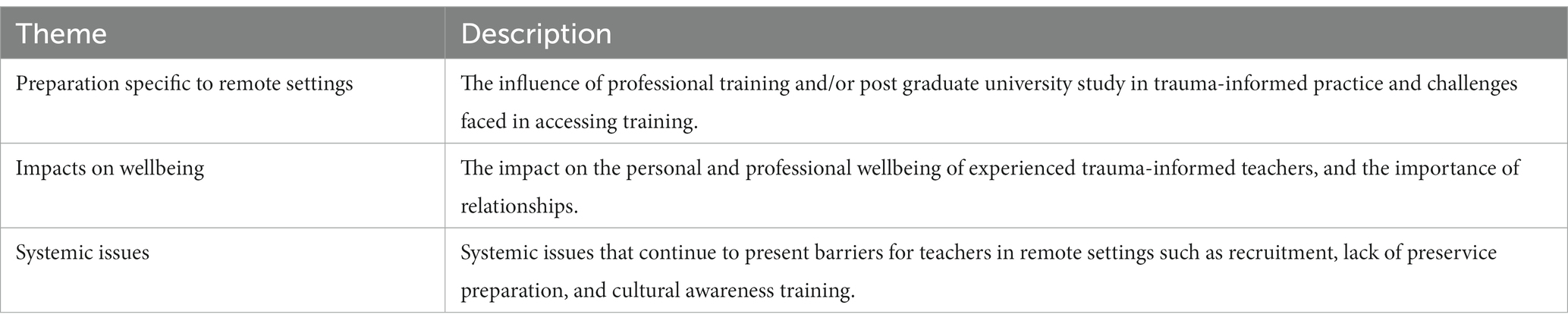

Within the richness of the data, three main themes emerged that addressed the research question: What is required for the work of experienced trauma-informed teachers in remote settings to be effective? Quotes are incorporated in this article to illustrate the experiences and thoughts of participants associated with each theme and each is accompanied by a participant identifier (for example P1 refers to participant one). Identifying information has been omitted to safeguard participants’ anonymity. Table 1 summarizes the three themes generated through the thematic analysis.

Table 1. Themes identifying what is required for experienced trauma-informed teachers work to be effective.

The importance of specific and adequate training and preparation were identified by participants as necessary for teachers to be able to teach effectively in remote settings with students impacted by trauma.

Participants in this study were experienced teachers working in remote settings and highly trained in trauma-informed practices having accessed postgraduate university training in trauma-informed practices, as well as other trauma-informed professional training opportunities either prior to, during, or after their post-graduate university training. Participants suggested that the training they undertook prepared them to work with students impacted by trauma by extending their knowledge and understanding of trauma-informed practices and underpinning theories. Participants shared their key learnings from undertaking post-graduate training in trauma-informed practices. One explained that “The course [higher education post graduate course] has been really good because I’ve been able to attach the science to the philosophy or the belief of the practice” [P4]. Another participant shared that, “the [higher education post graduate course] course has been great for [explaining] a wide breadth of knowledge and the neuroscience and everything behind it” (P5). However, one participant acknowledged they felt the training accessed, both professional development and the post-graduate course was “generalized” (P2) rather than being contextualized to what was required for teaching in a remote setting. This participant also reflected on the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives being included in any training regarding trauma-informed practice.

Participants shared that although they valued past training in trauma-informed practices, ongoing training and support was critical for them and for other staff to be able to work effectively with trauma-impacted students. One participant explained this by stating,

[Training] I did a few years ago was understanding the ACEs and how a high score contributes to outcomes of behavior, suspension and obviously retaining our kids. Then during [Training], again doing it the second time around…I felt like doing it again really consolidated all the learning the first time around. Because I think the first time around, I was so overwhelmed with how many strategies and skills and all the neuroscience, I kind of didn’t understand – not that I didn’t know where to start but it was a lot. Whereas the second time around, I’m hammering that, I’m picking that up, and just really easy strategies…just small things (P7).

On reflection, participants identified challenges they faced in accessing ongoing training, due to their working in a remote setting. One participant disclosed, “professionals [trainers] aren’t willing to give up that time to come remote, in the middle of nowhere, to provide that service [Training]. There’s still a lot of challenges about professional learning for remote communities or for teachers in remote communities” (P4).

In some remote communities, trainers do travel to schools and a participant in the study emphasized the benefits of this by stating,

We’re in a bigger school, they [school leadership] do seem to invest more into getting people to us and then it’s much more effective – because you’re actually doing the activities with your colleagues in the right – in the same context and that can be very powerful (P2).

Other participants detailed the challenges they faced to access relevant training if this was not provided onsite at their school. These included long distances to travel, difficulty arranging childcare, and budgetary and other impacts on schools that were associated with accessing relief teaching staff. One participant described this,

Financial aspect, that schools are having to commit in terms of travel in a remote community, but I think there’s a massive impact on staffing…. the length of time that you’re out a day either side to travel, the cost of travel which for some communities is – I don’t know, upwards of $600 one way [airfare]. But bigger than all of that is then being able to release teachers…. very difficult because you can’t get TRS [teacher release scheme – assists schools with replacing teachers while they are absent from school]. It’s usually one person that maybe gets to go [to the professional training] and it depends on staffing at the time (P6).

Participants noted that a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic was that training became more accessible to teachers in remote areas as face-to-face training increasingly moved to online provisions. This was recalled by a participant,

In the last 18 months with COVID, things have been moved forward in terms of, there’s so many more PDs [professional developments] are accessible online and that are offered after school or before school…. I think things are more accessible than they were 18 months ago, and I think it’s only going to increase now because we can actually do it remotely, we don’t have to do it face to face (P7).

However, for some participants accessing training online continued to present challenges as revealed by one participant, “then there’s the added complexities of accessing viable internet services…. whilst the internet and online stuff has opened up opportunities, I think that there’s lots and lots of challenges for remote and very remote” (P4).

Once overcoming barriers associated with accessing training, participants described the enormous and positive impact trauma-informed practices had on how they made meaning of their work in a remote setting.

Living in community, seeing what happens in community day in, day out, 24/7, hearing it, just being with families that are dealing with, well I didn’t call it trauma then because, well, I didn’t know what it was. It [training] just all made sense and I’m like, oh God for the last 12 years this is what I’ve been dealing with. I wish I knew now back then, and I can imagine the impact with the different – the impact I could have had on these kids’ lives if I had’ve known what I know now (P7).

Another participant agreed, “Being able to have that word [trauma] become part of how I thought about and the way that kind of changed my practice” (P2). While another participant appreciated how the post graduate training addressed their skill development in leadership. “What I love about this course [post graduate course] is that it is challenging me now at a leadership level to look beyond the classroom and to impact the whole school and community wide, and also have a voice systematically” (P3). The overwhelming consensus from participants emphasized that despite the challenges, accessing quality ongoing training in trauma-informed practices is essential.

Even though participants in this study were experienced teachers who were highly trained in trauma-informed practices and who identified that they had good relationships with students and families, they also were keen to discuss how their work impacted on their wellbeing. Wellbeing, as discussed by participants’ in this study, referred to feelings of satisfaction and meaning at work, balancing work with personal life, and looking after their emotional, mental and physical health. Their responses clearly explained that it can be challenging to maintain good health and wellbeing when you are a teacher working in remote setting with students impacted by trauma. This was influenced by both internal factors (personal characteristics of the educator) and external factors (location, students, community, other teachers). One participant shared, “I think remote has so much to offer if we are willing to embrace it. I think it is an amazing place to grow but it’s also a place that can break you if you are not resilient enough to deal with it” (P3).

Most of the participants (n = 6) drew on their self-awareness in which they identified the importance of self-reflection and their understanding their own needs, strengths, and limitations. As one participant disclosed,

Your relationship with yourself should be so healthy so that you can know… I have my own limitations and I first need to take care of myself if I want to have an effective impact on the students, I work with…. I do live in a highly distressed community – to make sure – because I was carrying my own things – to make sure that doesn’t trigger me (P3).

It was suggested that this type of self-awareness enabled teachers to reflect on what they needed to do to continue to effectively do their work.

Another participant conveyed the changing nature of their wellbeing. “In terms of my personal wellbeing, there are times when it’s incredibly difficult…personally, I feel like at the moment, but ask me tomorrow it might be different, that I’m travelling along pretty ok” (P4). This was also like another participant, “I try and find that balance because some days are horrific. But there are other days where I have – everything just falls into place, the students are amazing, everything goes right, so everything you know, a bit of a balance” (P1).

Findings suggest that working in a remote setting with students impacted by trauma can, in some instances, have a long-term impact on teacher wellbeing. As explained by one participant, this can be due to

Hearing constantly about hardships and the traumatic things that kids go through, when you lay in bed at night or you’re sitting with your family at home and you look around at your own privilege, it hurts, and sometimes you can’t – like I know tears probably come once a month with the weight that you bear on your shoulders. Sometimes you look around your school and you think, if I wasn’t here for these kids, where would they be or who would they go to? If I ever left, what would happen? Professionally, I think the more experience you have, the longer you are at a school – well I speak for myself – you become the dumping ground for our hardest kids (P7).

Participants in the study suggested that their wellbeing was impacted because they felt they had to do everything they could to ensure that the needs of the students impacted by trauma were met. Participants also identified this need to take on everything in other staff members as well.

The biggest problem that I’ve come across is staff trying to – or feel they need to solve the world and they take that on board. It’s lovely that they want to do that, but it becomes all – encompassing, and it also becomes very difficult to handle when there’s not simple answers for complex problems (P4).

Participants indicated the feeling of having to take on everything took up a significant amount of time in their day at the expense of their own work and personal life. One suggested that,

You definitely take on everything because there’s only such a few number of staff. I don’t do it for my own personal glory, it’s for the kids, so that where I’m working from, to make sure they get that easy transition from primary school to high school, that easy transition from high school, through high school into the work force. I can be working until 6 o’clock at night, sometimes later (P1).

Another participant reported,

There’s not time during the day where you can actually sit at your desk and do the 17 million things I’ve got to get done as my own role as a leader, but I can’t because I’ve got 7 kids that need me, haven’t got shoes, haven’t had food, Mum and Dad have a massive blue [fight], haven’t slept – dealing with that constantly. Then when getting home, having the relationship with community, sometimes my phone doesn’t stop till midnight dealing with different things (P7).

Feeling that they needed to take on everything led to participants to be frustrated when they tried to provide an education to students.

The part I find hard and the most frustrating is actually being able to still provide the education, still be able to build a pathway and to see success and that’s – you get so good at providing the relationship that the actual – the progress or the outcomes become harder to see (P2).

Participants also relayed the frustration felt toward colleagues who were not trauma-informed in their practice. One suggested that,

There’s a few really great colleagues I’ve got that get it [trauma] but then there’s other colleagues that just have no idea, and professionally it makes you feel really undervalued” (P7). Another voiced, “My other frustrations come from other staff members and their – like other people were saying, their sort of lack of understanding in regard to it [trauma]. In my role, I frequently fight fires that the young person didn’t start, the staff member started, and the young person’s just carried it on and escalated it with them and I’ve got to fire fight [resolve the issue] (P5).

Despite the significant impact on wellbeing associated with working in remote settings, all teachers in the study drew strength from the relationships they had built with students and families. One participant explained how they

…developed a relationship, and that relationship base really did allow me to, allowed me to grow as a teacher as much as it allowed the student to grow as a student” (P1). Another participant recounted, “That [relationships] enabled me to have that confidence because I was really, not afraid of trauma and then not afraid to engage with families, because most families I found were just crying out for release or just someone to hear them, not answers or anything, but just for someone else to understand what is going on” (P7).

A further participant shared,

You do connect to the community……. There’s all the negativities but there’s a whole bunch of positives associated with living in community around relationship building, and of course there is the negative side to that. There’s the ability to get out and live and breathe country. I’m connecting to really amazing people, building really amazing relationships (P4).

Systemic issues that were barriers to working effectively with students impacted by trauma were also discussed by participants. Systemic issues identified by participants included: (i) issues with recruitment of teachers to work in remote settings, (ii) a lack of preparation of teachers to work in remote settings, (iii) a lack of understanding by teachers of the impact of trauma on students, and (iv) a lack of trauma-informed, cultural awareness training.

One of the key barriers participants identified was how teachers were recruited to work in remote settings. One participant shared,

I find that our regions with really remote areas sometimes create an impression that, come out and have this incredible adventure. They create a picture of all of these wonderful things that young educators can come and experience and each one of those things are true, but if that is the reason why they come out, they come with these false expectations. [Need] to make sure that they know their ‘why’ when come out, they know that these places [remote] are called places of adversity. Just the remoteness in itself is adverse and then its heat of 40 degrees on a consistent and then you add to that the levels of distress in our communities and what they experience. I don’t think our systems are actually able to care for our educator’s mental health and wellbeing (P3).

The lack of preparation of teachers at the pre-service level was also identified by participants as a systemic issue. One participant who held this view expressed that “getting new teachers straight from uni is not the answer” (P1). This lack of preparation was further explained by a participant who identified additional systemic issues related to training and recruitment.

I’m not sure that we [education systems] prepare people enough before they come out…staff need to be well prepared for coming out to remote. There’s some really challenging situations from a classroom perspective that staff aren’t prepared for. The staff I’m working with here, 80% are first-or second-year teachers who never had remote or regional experience before – lack professional learning, lack of access to professional learning, and really not a particularly good understanding of what’s like to teach in a remote or region – remote classroom as opposed to a mainstream classroom (P4).

According to participants, teachers who are not prepared to work in remote settings, often experience culture shock once they arrive and commence work. A participant reported that,

It’s a massive culture shock moving to a remote area for a lot of people in terms of everything – internet, food, shops that are available – all that sort of thing impacts on your life. All of them [teachers] come out of highly privileged environments in our metropolitan areas, and they come here, and it was in absolute ignorance, no idea of what to expect here. Within the first three weeks we had a crisis on our hands because they just could not mentally process what they were confronted with in our high school every day (P3).

Another participant shared their observations of the cultural bias displayed by some teachers who come to work in remote settings.

I find there’s a lot of cultural bias with their [teacher] own prior knowledge and their expectation of what they’re coming into when they start working in a remote community. The natural bias of their own prior knowledge quite often, it just doesn’t marry up (P1).

Another systemic issue identified by participants was working with teachers who had limited understanding about the impact trauma has on students’ behavior and learning. Participants identified a correlation between students’ relationships with teachers who were not trauma-informed, and their consequent challenging behaviors. A participant shared their observations of working with teachers who are not trauma informed,

There’s so many people still that are…they don’t realise that it is not a personal attack [children’s behavior]” (P7). While another reflected, “they [new teachers] come in, being high school, it’s curriculum focus, my outcomes are a, b, c, and they forget that it’s not just the outcomes that make the learning, it’s actually the student’s whole wellbeing that helps with the learning that in turn build with that learning as well” (P1).

Another significant systemic issue recognized by participants was the lack of cultural awareness training incorporating trauma-informed practices. One participant expressed this as “I would say that [cultural awareness is] really lacking actually in terms of PD available on trauma… lacking in terms of Indigenous perspectives” (P6). Teachers need cultural awareness and knowledge to support them to do their work, and when this is not forthcoming it has a major impact on wellbeing. This was clearly articulated by one participant,

You need it [cultural awareness] full stop. You need to have that Indigenous knowledge and cultural awareness, that understanding of intergenerational trauma, and I think a lot of the vicarious trauma that teachers suffer is because they don’t understand. They don’t understand previous trauma, the intergenerational trauma as to how and why this affecting their [students’] behaviours and their language and how they speak and how they behave. So, yeah, I think having that lack of Indigenous culture [awareness] and knowledge really does then impede on vicarious trauma for the teachers (P1).

Another participant expanded this further and identified what they see should happen to prepare teachers to work in remote settings with students impacted by trauma,

Having worked quite significantly in Indigenous education and now living and breathing community life for the last few years, there’s significant lack of Indigenous perspectives around trauma-informed practice. It should be compulsory for every educator to have Indigenous practice, understanding anyway and cultural awareness anyway, but if you’re come out to communities, having some really good understanding (P4).

This study presents themes that emerged from a focus group interview with remote teachers regarding what is needed for them to do their work effectively with students impacted by trauma. A small but growing amount of research has focused on the perspectives of teachers working with students impacted by trauma (Alisic, 2012; Davies and Berger, 2020; Barrett and Berger, 2021; Berger et al., 2021; Miller and Berger, 2022) including those who are working in remote settings (Brown et al., 2022). Due to the paucity of research in remote school settings and the particular challenges faced by these teachers, it is important that research continues to examine this understudied topic.

A main theme that emerged consistently from data in this study was the importance of teachers being adequately prepared to work in remote settings with students impacted by trauma which included having access to quality training in trauma-informed practices. Numerous studies reports that teacher training in trauma-informed practice is limited (Davies and Berger, 2020; Barrett and Berger, 2021; Miller and Berger, 2022; Oberg and Bryce, 2022) and this is exacerbated for teachers in remote areas (Frankland, 2021; Oberg and Bryce, 2022). What is unique about the participants in this study is that all have completed post-graduate studies in trauma-informed education as well as additional professional training in trauma-informed practices, which makes them highly qualified to discuss the ongoing needs of experienced, trauma-informed teachers. In addition, participants in this study were living and working remotely. Thus, the findings of the current study add an important and unique perspective to the research evidence that is not often considered.

Through listening to participants in the current study, insight was gained into the challenges faced in accessing quality ongoing training and support due to geographic factors. It appears there are many barriers that remote teachers must overcome that their urban/metropolitan colleagues do not face, such as isolation, lack of professional training opportunities, lack of internet access, distances to travel and related costs. The barriers that participants in the current study faced have been identified in previous research (Motley et al., 2005; Maher and Prescott, 2017). For example, Maher and Prescott (2017) found that the main challenges remote teachers faced were location and lack of professional development opportunities. This was also identified by Motley et al. (2005) who found that maintaining currency in practice through differentiated professional development opportunities suitable to the remote context was needed. When teachers feel supported with ongoing professional development opportunities, they are more likely to stay in the profession (Maher and Prescott, 2017). The importance of teachers engaging in regular professional training is well established and essential in “sustaining meaningful change” (Riley and Pidgeon, 2019, p. 138). The central role teachers in remote communities play in facilitating change has been highlighted in recent work, particularly with youth affected by trauma (Brown et al., 2022). Therefore, supporting these teachers in ongoing professional learning is an essential part of addressing the underlying inequities associated with remote and trauma-affected communities. Currently, there is limited research into what is required to support the professional training needs of teachers in remote settings, and while this study adds insight into what addressing some of these challenges could achieve, further research is required to understand this more deeply.

Teachers in remote schools are at risk of negative impacts on their personal and professional wellbeing (Willis and Grainger, 2020; Hine et al., 2022). They are often working with students in communities that are more socio-economically disadvantaged and have higher rates of trauma than metropolitan areas. Despite being experienced and highly trained in trauma-informed practices, teachers in the current study reported their wellbeing was impacted. This is congruent with studies where teachers who have not received trauma-informed practices training reported that their wellbeing was also affected by working with students impacted by trauma (Berger and Samuel, 2020). This suggests that there is more than just lack of training which is impacting on the wellbeing of teachers who work with students impacted by trauma.

Several distinct reasons were given to explain the impact on the wellbeing of teachers in this study. These included feeling as though they needed to “do everything” to support children and families and their frustration with working with teachers who do not understand the impact of trauma on students’ behavior and learning due to the lack of this focus in their pre-service training. The teachers who participated in this study have identified systemic issues related to inadequate preparation of teachers coming into remote areas that have been documented in international research in rural and remote education (Echazarra and Radinger, 2019; Riley and Pidgeon, 2019). As a consequence of the lack of preparation of their colleagues, teachers participating in the current study felt because they were experienced and trained, their colleagues tended to rely on them to address the needs of students impacted by trauma which did impact on their wellbeing and their other work commitments. To date, there is a small body of research investigating pre-service training in trauma-informed practice (Davies and Berger, 2020; McClain, 2021; L’Estrange and Howard, 2022) and the findings of the current study further emphasize the importance of adequate preparation of remote teachers by identifying the impact that a lack of pre-service preparation can have on more experienced teachers.

Teachers in the current study also expressed significant concern in relation to lack of cultural awareness training. In remote settings, cultural awareness is key to building and maintaining relationships with students, families and communities and is an important component of being trauma-informed (Morrison et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2022) and promoting a socially just way of working (Crosby et al., 2018). This study emphasizes that, when working in remote communities with high proportions of Indigenous peoples, teachers need to be culturally aware and be able to access ongoing, cultural awareness training that is specific to their local communities and not a “one-size fits all” approach. Training in cultural awareness and trauma-informed practices needs to be contextualized and address historical trauma to move beyond the questions of “what’s wrong” with the student and “what has happened” to the student, to “why” these experiences have happened to the communities and to the students with whom they work (Gherardi et al., 2020, p. 492). This means teachers working in remote communities need to be aware of their own culture and their own position of privilege, and the disempowerment that disproportionately exists across society. This includes recognizing their position of power both as a teacher and as a member of a dominant culture and the influence this may have in the community in which they work (Crosby et al., 2018; Gherardi et al., 2020). Teachers need to bring “self-reflexivity to their roles in schools and communities, being aware of the differences that present to them within the context and responding with flexibility” (Guenther et al., 2016, p. 87). There was some evidence that teachers in the current study had a strong sense of cultural awareness and were reflexive in their responses to the students and staff with whom they worked. This was reflected in the importance they placed on building relationships within the communities in which they worked and their awareness of their privileged position.

One way to begin to address the impact of the lack of cultural awareness in remote teachers is to increase the opportunities for pre-service training and professional learning in this space. Currently, there is a lack of consistent high quality pre-service and in-service professional development in cultural awareness in Australia (Morrison et al., 2019). Further, teachers may not be accessing professional learning due to individual or school choice, due to other areas of staff development that are prioritized by school leadership, or due to the lack of quality professional learning opportunities that are available (Morrison et al., 2019). Research has shown that integrating culturally responsive practices improves teachers’ ability to support students (Bonner et al., 2018; Gay, 2021). Trauma-informed practice embedded within culturally responsive pedagogy is emerging as a promising framework for schools and for the teaching profession (Chafouleas et al., 2021; Schimke et al., 2022). However, currently, it is not mandated in Australia for teachers to develop culturally responsive pedagogies (Morrison et al., 2019) or for initial teacher education to include trauma-informed training (Longaretti and Toe, 2017; L’Estrange and Howard, 2022). These are difficult and complex systemic issues to address, and while the current study is small and exploratory in nature, the findings highlight some of the real-world impacts of these issues at a community and individual teacher level. Findings from this study add to the imperative for future research to continue to include the voices of remote teachers and their insights into working with trauma affected students and communities.

There were some limitations in this study. Challenges with recruitment of a representative sample led to a small sample size (n = 7) which needs to be considered in the interpretation of findings and their implications. Also, the recruitment method may have introduced some bias as participants were recruited through their engagement in post graduate education at one university. Given a different recruitment mechanism, other teachers from broader contexts may have chosen to participate in the study resulting in a more diverse sample and possibly different findings. However, given that we wanted to recruit a purposeful sample of experienced teachers from remote settings who completed post-graduate training in trauma-informed practices, the sample population to draw from is small. Another limitation of this study is that data collection focused on participants’ professional experiences and did not explore personal factors that may have affected their experiences and therefore their responses (for example their own past histories and experiences). Providing questions in the online questionnaire regarding types of and number of professional development (trauma informed and cultural awareness training) opportunities accessed by participants would have provided further information about their training and how this may have influenced their practice.

Future research could investigate what is offered at the pre-service level in preparing teachers to teach in remote settings, including what trauma-informed practices and cultural awareness training is provided by initial teacher education programs across Australia. Additionally, mixed-method data collection with a larger sample size and participants from broader contexts may also assist in evaluating the current capacity of teachers when working in remote settings with students impacted by trauma and the means to enhance this capacity. Identification of gaps in educator competency may also inform the development of targeted professional development and resources for teachers who are wanting to work in remote settings, so that they can become trauma-informed and culturally aware.

This study was able to identify some important findings regarding the needs of experienced, trauma-informed teachers who are working in remote areas to do their jobs well. Findings emphasize the need for greater and easier access to ongoing, quality professional training so that more experienced teachers remain equipped to take on leadership roles in trauma-informed practice in their schools and communities. Findings also emphasize the importance of pre-service teacher education in trauma-informed practice and cultural awareness to enhance the knowledge and skill of colleagues of experienced teachers, which would in turn make the work of experienced teachers easier and more effective. Quality preparation and training is essential for teachers in remote areas to respond effectively to trauma-impacted students and is vital to protect and enhance their personal and professional wellbeing. Through listening to the teachers who participated in this study, important insights into systemic issues that could enhance or hinder their work were identified. Importantly, findings emphasized that teachers building relationships with their communities and having strong cultural awareness are vital for them to experience success when working with trauma affected students in remote settings.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because ethical approval for this study to conduct the research does not extend to the use of original/raw data in future studies. Hence data are not available in a public access data repository. Request to access data sets should be directed to the corresponding author. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bWVlZ2FuLmJyb3duQHF1dC5lZHUuYXU=.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Queensland University of Technology Ethics Review Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MB conceived and designed the study, collected the data, performed the data analysis, interpreted data for the article, wrote the manuscript, and co-ordinated authors in responding to successive drafts. LL’E conceived and designed the study, performed the data analysis, interpreted data for the article, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Seed funding was provided by the Queensland University of Technology’s Center for Child and Family Studies Research Group. This funding was used for research assistant and professional transcription of interview data.

The authors would like to sincerely thank the teachers who participated in this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adler, P. S. (1975). The transitional experience: An alternative view of culture shock. J. Humanist. Psychol. 15, 13–23. doi: 10.1177/002216787501500403

Akbari, R., and Tajik, L. (2009). Teachers’ pedagogic knowledge base: A comparison between experienced and less experienced practitioners. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 34, 52–73. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2009v34n6.4

Alisic, E. (2012). Teachers’ perspectives on providing support to children after trauma: A qualitative study. Sch. Psychol. Q. 27, 51–59. doi: 10.1037/a0028590

Auld, G., Dyer, J., and Charles, C. (2016). Dangerous practices: The practicum experiences of non-indigenous pre-service teachers in remote communities. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 41, 165–179. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2016v41n6.9

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023). Remoteness structure – the Australian statistical standard (ASGS) remoteness structure. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/statistical-geography/remoteness-structure

Australian Government, Department of Employment, Education and Training (2020). Education in remote and complex environments. Parliament of Australia. Available at: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-11/apo-nid309426.pdf

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL]. (2021). Spotlight: Professional learning for rural, regional and remote teachers. Available at: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/research-evidence/spotlight/professional-learning-for-rural-regional-and-remote-teachers.pdf

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL] (2022). Australian workforce data 2022 – teacher survey 2018-2020 – school characteristics by position (school). Available at: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/australian-teacher-workforce-data/key-metrics-dashboard

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL]. (2023). Australian teacher workforce data – key metric dashboard release: Initial teacher education: Supply by jurisdiction and provider data January 2023. Available at: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/atwd/reports/atwd-key-metrics-dashboard-ite-jan-2023.pdf?sfvrsn=6171b43c_2

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2022a). Child protection Australia 2020-2021. Australian Government. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2020-21/contents/about

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2022b). Profile of Indigenous Australians. Australian Government. Profile of Indigenous Australians-Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available at: aihw.gov.au

Ban, J., and Oh, I. (2016). Mediating effects of teacher and peer relationships between parental abuse/neglect and emotional/behavioural problems. Child Abuse Negl. 61, 35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.010

Barker, Bruce O., and Beckner, Weldon. (1985). Rural education preservice training: A survey of public teacher training institutions in the United States. Paper presented at 77th rural education National Conference, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, October 13–15. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED261838.pdf

Barrett, N., and Berger, E. (2021). Teachers’ experiences and recommendations to support refugee students exposed to trauma. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 24, 1259–1280. doi: 10.1007/s11218-021-09657-4

Bellamy, T., Krishnamoorthy, G., Ayre, K., Berger, E., Machin, T., and Rees, B. E. (2022). Trauma-informed school programming: A partnership approach to culturally responsive behavior support. Sustainability 14:3997. doi: 10.3390/su14073997

Berger, E., Bearsley, A., and Lever, M. (2021). Qualitative evaluation of teacher trauma knowledge and response in schools. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 30, 1041–1057. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2020.1806976

Berger, E., and Samuel, S. (2020). A qualitative analysis of the experiences, training, and support needs of school mental health workers regarding student trauma. Aust. Psychol. 55, 498–507. doi: 10.1111/ap.12452

Biddle, C., Mette, I., and Mercado, A. (2018). Partnering with schools for community development: Power imbalances in rural community collaboratives addressing childhood adversity. Community Dev. 49, 191–210. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2018.1429001

Bonk, Ivy T. (2016). Professional development for elementary educators: Creating a trauma informed classroom (Doctoral dissertation). Regent University. ProQuest LLC.

Bonner, P. J., Warren, S. R., and Jiang, Y. H. (2018). Voices from urban classrooms: Teachers’ perceptions on instructing diverse students and using culturally responsive teaching. Educ. Urban Soc. 50, 697–726. doi: 10.1177/0013124517713820

Borntrager, C., Caringi, J. C., van den Pol, R., Crosby, L., O’Connell, K., Trautman, A., et al. (2012). Secondary traumatic stress in school personnel. Adv. School Ment. Health Promot. 5, 38–50. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2012.664862

Brasche, I., and Harrington, I. (2012). Promoting teacher quality and continuity: Tackling the disadvantages of remote indigenous schools in the Northern Territory. Aust. J. Educ. 56, 110–125. doi: 10.1177/000494411205600202

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, E. C., Freedle, A., Hurless, N. L., Miller, R. D., Martin, C., and Paul, Z. A. (2020). Preparing teacher candidates for trauma-informed practices. Urban Educ. 57, 662–685. doi: 10.1177/0042085920974084

Brown, M., Howard, J., and Walsh, K. (2022). Building trauma informed teachers: A constructivist grounded theory of remote primary school teachers’ experiences with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Front. Educ. 7:537. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.870537

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed flexible learning: Classrooms that strengthen regulatory abilities. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 7, 218–239. doi: 10.18357/ijcyfs72201615719

Brunzell, T., Waters, L., and Stokes, H. (2021). Trauma-informed teacher wellbeing: Teacher reflections within trauma-informed positive education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 46, 91–107. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2021v46n5.6

Caringi, J. C., Stanick, C., Trautman, A., Crosby, L., Devlin, M., and Adams, S. (2015). Secondary traumatic stress in public school teachers: Contributing and mitigating factors. Adv. School Ment. Health Promot. 8, 244–256. doi: 10.1080/1754730x.2015.1080123

Carroll, A., Forrest, K., Sanders-O’Connor, E., Flynn, L., Bower, J. M., Fynes-Clinton, S., et al. (2022). Teacher stress and burnout in Australia: Examining the role of intrapersonal and environmental factors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 25, 441–469. doi: 10.1007/s11218-022-09686-7

Chafouleas, S., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., and Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch. Ment. Heal. 8, 144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Chafouleas, S. M., Pickens, I., and Gherardi, S. A. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Translation into action in K-12 education settings. Sch. Ment. Heal. 13, 213–224. doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09427-9

Champine, R. B., Hoffman, E. E., Matlin, S. L., Strambler, M. J., and Tebes, J. K. (2022). “What does it mean to be trauma-informed?”: A mixed-methods study of a trauma-informed community initiative. J. Child Fam. Stud. 31, 459–472. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-02195-9

Commonwealth of Australia (2020). Education in remote complex environments. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Employment, Education and Training. Available at: https://www.aph.gov.au/-/media/02_Parliamentary_Business/24_Committees/243_Reps_Committees/Education_and_Employment/Education_in_remote_and_complex_environments/Remote_education_full_report.pdf?la=en&hash=FC217ECE9459153DF91EE6D2DA1478C85E9B3E38

Cromer, L. D., Gray, M. E., Vasquez, L., and Freyd, J. J. (2018). The relationship of acculturation to historical loss awareness, institutional betrayal, and the intergenerational transmission of trauma in the American Indian experience. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 49, 99–114. doi: 10.1177/0022022117738749

Crosby, S. D., Howell, P., and Thomas, S. (2018). Social justice education through trauma-informed teaching. Middle Sch. J. 49, 15–23. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2018.1488470

Crouse, T., and Lowe, P. A. (2018). “Snowball sampling” in The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation. ed. B. B. Frey (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc)

Crump, S. (2005). Changing times in the classroom: Teaching as a ‘crowded profession’. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 15, 31–48. doi: 10.1080/09620210500200130

Davies, S., and Berger, E. (2020). Teachers’ experiences in responding to students’ exposure to domestic violence. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 44, 96–109. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2019v44.n11.6

Disbray, S. (2016). Spaces for learning: Policy and practice for indigenous languages in a remote context. Lang. Educ. 30, 317–336. doi: 10.1080/09500782.2015.1114629

Dorman, J., Kennedy, J., and Young, J. (2015). The development, validation and use of rural and remote teaching, working, living and learning environment survey (RRTWLLES). Learn. Environ. Res. 18, 15–32. doi: 10.1007/s10984-014-9171-0

Eacott, Scott, Niesche, Richard, Heffernan, Amanda, Loughland, Tony, Gobby, Brad, and Durksen, Tracy. (2021). High-impact school leadership: Regional, rural and remote schools. Commonwealth Department of Education, Skills and Employment, Australia. Available at: https://researchmgt.monash.edu/ws/portalfiles/portal/362959484/354066423_oa.pdf

Eady, M. J., Woolrych, T. J., and Green, C. A. (2021). Indigenous primary school teachers’ reflections on cultural pedagogy – developing positive social skills and increased student self-awareness in the modern day classroom. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 13, 211–228. doi: 10.1080/2005615X.2021.1964263

Echazarra, Alfonso, and Radinger, Thomas. (2019). “Learning in rural schools: Insights from PISA, TALIS and the literature”, OCED education working papers no. 196. OCED Publishing: Paris.

Essary, J. N., Barza, L., and Thurston, R. J. (2020). Secondary traumatic stress among educators. Kappa Delta Pi Record 56, 116–121. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2020.1770004

Evans, G. D., Radunovich, H. L., Cornette, M. M., Wiens, B. A., and Roy, A. (2008). Implementation and utilisation characteristics of a rural, school-linked mental health program. J. Child Fam. Stud. 17, 84–97. doi: 10.1007/s10826-007-9148-z

Figley, Charles R. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Foley, G., and Howell, E. (2017). Cultural awareness training for educational leaders and teachers – a lesson in history. Ágora 52, 41–44. doi: 10.3316/informit.069605538656098

Frankland, M. (2021). Meeting students where they are: Trauma-informed approaches to rural schools. Rural Educ 42, 51–71. doi: 10.35608/RURALED.V42I2.1243

Freeman, Chris, O’Malley, Kate, and Eveleigh, Frances. (2014). Australian teachers and the learning environment: An analysis of teacher response to TALIS 2013 Final report. Australian Council for Educational Research. Available at: https://research.acer.edu.au/talis/2/

Gay, G. (2021). “Culturally responsive teaching: Ideas, actions, and effects” in Handbook of urban education. eds. H. R. Milner IV and K. Lomotey (Milton: Taylor & Francis Group), 212–233.

Gherardi, S. A., Flinn, R. E., and Jaure, V. B. (2020). Trauma-sensitive schools and social justice: A critical analysis. Urban Rev. 52, 482–504. doi: 10.1007/s11256-020-00553-3

Goodman, R. D., David Miller, M., and West-Olatunji, C. A. (2012). Traumatic stress, socioeconomic status, and academic achievement among primary school students. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 4, 252–259. doi: 10.1037/a0024912

Goodridge, D., and Marciniuk, D. (2016). Rural and remote care: Overcoming the challenges of distances. Chron. Respir. Dis. 13, 192–203. doi: 10.1177/1479972316633414

Graham, L. J., White, S. L. J., Cologon, K., and Pianta, R. C. (2020). Do teachers’ years of experience make a difference in the quality of teaching? Teach. Teach. Educ. 96:103190. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103190

Guenther, J., Disbray, S., and Osborne, S.. (2016). Red dirt education: A compilation of learnings from the remote education systems project. Ninti One Limited. Available at: https://nintione.com.au/resource/RedDirtEducation_CompilationLearningsRES_EBook.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2022).

Hasley, J. (2018). Independent review into regional, rural and remote education. Final Report. Australian Government, Department of Education. Available at: https://www.education.gov.au/quality-schools-package/resources/independent-review-regional-rural-and-remote-education-final-report

Heffernan, A., MacDonald, K., and Longmuir, F. (2022). The emotional intensity of educational leadership: A scoping review. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ., 1–23. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2022.2042856 [Epub ahead of print].

Hine, R., Patrick, P., Berger, E., Diamond, Z., Hammer, M., Morris, Z. A., et al. (2022). From struggling to flourishing and thriving: Optimizing educator wellbeing within the Australian education context. Teach. Teach. Educ. 115:103727. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103727

Howard, Judith A. (2013). Distressed or deliberately defiant? Managing challenging student behaviour due to trauma and disorganised attachment. Toowong, QLD: Academic Press.

Hudson, P., and Hudson, S. (2008). Changing preservice teachers’ attitudes for teaching in rural schools. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 33, 67–77. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2008v33n4.6

Hudson, S., Young, K., Thiele, C., and Hudson, P. (2020). An exploration of preservice teachers’ readiness for teaching in rural and remote schools. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 30, 51–68. doi: 10.47381/aijre.v30i3.280

Irving, M., Short, S., Gwynne, K., Tennant, M., and Blinkhorn, A. (2017). ‘I miss my family, it’s been a while…’ a qualitative study of clinicians who live and work in remote Australian aboriginal communities. Aust. J. Rural Health 25, 260–267. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12343