- 1Museology Department, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

- 2Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt

Following the implementation of 2018’s laws on the rights of persons with disabilities (PWDs) in Egypt, students with disabilities (SWDs) have both legal and moral rights to meaningful learning opportunities and inclusive education. Despite that, SWDs still have very limited education resources which limit their career aspirations and quality of life. In this respect, education whether as part of formal education or lifelong learning is central to the museum’s mission. Museums, as part of non-formal education, are being acknowledged for their educative powers and investments in the development of quality formal, non-formal, and informal learning experiences. Further, phrases such as “inclusivity,” “accessibility,” and “diversity” were notably included in the newly approved museum definition by ICOM (2022) emphasizing museums’ obligations to embrace societal issues and shape a cultural attitude concerning disability rights, diversity, and equality together with overcoming exclusionary educational practices. The study seeks to investigate the existing resources and inclusive practices in Egyptian museums to achieve non-formal education for SWDs. Qualitative research approaches have been employed to answer a specific question: How can Egyptian museums work within their governing systems to support the learning of SWDs beyond their formal education system? The study aims to assess the potential of Egyptian museums in facilitating learning for SWDs. Further, it examines the capability of Egyptian museums in contributing to informal and non-formal learning for SWDs and striving for inclusive education inspired by the social model of disability that fosters inclusive educational programs and adopts a human rights-based approach. The results revealed that Egyptian museums contributed to the learning of SWDs, yet small-scale programs and individual efforts, but they are already engaged in active inclusive practices that address the learning of SWDs. The study suggests that they need to be acknowledged and supported by the government as state instruments and direct actors in advancing inclusive education and implementing appropriate pedagogies in favor of SWDs.

1. Introduction

Children with disabilities are one of the most marginalized and excluded groups in the education (Schuelka and Johnstone, 2012; UNESCO, 2020). There is no doubt that inclusive education for SWDs in developing countries is still difficult to achieve (Srivastava et al., 2015). Despite that, the rights of children and youth with disabilities are widely recognized in the Egyptian constitution, Egypt’s Strategic Vision 2030, and the new legislation of the state; they still face several barriers to accessing their educational resources (Ministry of Education, 2014; Zakaria, 2020; Hassanein et al., 2021). Their barriers range from inaccessible transportation services and facilities to, most importantly, attitudinal and intellectual barriers, to the effectuation of laws to be fully integrated into Egyptian society. One of the major barriers to the inclusion of SWDs in Egypt is the attempt of the Egyptian government to adopt a Western-style education system rather than developing a specific education system that fits the social, cultural, political, and educational context of Egyptian society (Kim, 2014; Hassanein et al., 2021).

The study argued that Egyptian museums can contribute to the practices of inclusive education and the successful implementation of Egypt’s strategic goals toward the full inclusion of learners with disabilities. Museums, as non-formal learning environments (Hooper-Greenhill, 1999, 2007; Dierking, 2005; Falk and Dierking, 2016) and social institutions (Silverman, 2010; Morse, 2022), may embrace diversity among all people including PWDs, and support the learning opportunities for SWDs (Sandell, 2002, 2003, 2017; Kanari and Souliotou, 2020). Museums have educative powers and social impact that reflected upon supporting formal and non-formal education (Black, 2012; Falk and Dierking, 2016), serving communities (Silverman, 2010; Morse, 2022), addressing discrimination and stereotypes, combating prejudices and inequality (Sandell, 2002, 2017; Sandell and Dodd, 2010; Sandell and Nightingale, 2012), and making institutional changes for the betterment of society (Fleming, 2012; McCall and Gray, 2014).

Within the framework of the social model of disability that emphasizes the socio-environmental barriers that exclude PWDs (Shakespeare and Watson, 2002; Shakespeare, 2006; Oliver, 2013; Rocha et al., 2022), museums can actively raise the awareness of lawmakers, policymakers, and other organizations in Egypt about the societal barriers faced by individuals with disabilities and their effect on the implementation of inclusive education (Zakaria, 2020), and thus support the education system to identify barriers to inclusion and develop the appropriate policies and practices needed for SWDs’ education. Furthermore, progress can be achieved by incorporating the museums of Egypt, as educational institutions, among the essential instruments of the state that should be used alongside schools in supporting the learning processes for SWDs (Bennett, 1995; Hein, 2006; Hooper-Greenhill, 2007).

Much of the literature in the museum studies field used “informal” and “non-formal” terms in relation to the educational practices in museums in an approach to elaborate on the educational characteristics of the programs and activities museums offered (Hooper-Greenhill, 1999, 2007; Falk and Dierking, 2000; Dierking, 2005; Hein, 2006). While museums are perceived as “informal education institutions” and “free-choice” learning spaces with multiple leisure experiences, the term “non-formal” is usually used within museums to refer to the learning programs and activities that take place outside the formal educational setting (Falk et al., 2006; Falk and Dierking, 2016; McGhie, 2020).

The study aims to investigate the role of museums as formal, informal, and non-formal learning environments in promoting education for SWDs and supporting the formal education system of Egypt in realizing their rights. The objectives of the study are, therefore, twofold. Firstly, to assess the capability of Egyptian museums’ potential in facilitating both informal and non-formal learning for SWDs. Secondly, to argue the social responsibilities of the museums in fostering inclusive practices and striving for SWDs’ rights in education and thus contribute to their integration into society. In pursuit of these objectives, a qualitative approach was adopted using semi-structured interviews with twenty-three museum professionals in a variety of institutional settings (i.e., different types of museums and concerned administrative divisions) to assess the effectiveness of Egyptian museums in performing these roles and responsibilities. In addition, five semi-structured interviews were performed with students with multiple disabilities to reflect their voices in the existing inclusive practices of the studied museums.

2. Setting the context: the evolving roles of museums in education, learning, and inclusion

Today, the traditional roles of museums as institutions for collecting, preserving, and displaying artifacts have been adjusted, expanded, and evolved to meet the ongoing changes in society. Museums as an integral part of society are invaluable resources that constitute education and knowledge for individuals and communities. As public institutions, museums are for all and act as a great source of learning and inspiration for everyone coming through the doors (Hooper-Greenhill, 1992; Bennett, 1995; Black, 2012; Chen, 2013). The functional origin of museums is to provide education and learning for people and their communities (Hooper-Greenhill, 1999, 2007; Talboys, 2005). Museums buildings, exhibitions, collections, and other associated knowledge that emerged from curatorship practices and interpretation strategies are forming the basis of a wide range of education and learning programs that support people’s knowledge and regulate their thinking in society (Hooper-Greenhill, 2000, 2007; Marstine, 2006; Chen, 2013).

The educational purpose of museums is well-documented throughout museum history. Since the 19th century, museums, as major instruments of the state, dedicated to the education and edification of the general public (Bennett, 1995; Hein, 2002, 2006). By the beginning of the 20th century, museums were recognized for their significant role in teaching, as they served as educational resources along with schools and universities (Hooper-Greenhill, 1999, 2007; Falk and Dierking, 2000, 2016; Chen, 2013). The 1974’s museum definition of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) emphasized the educational role of museums as: “A non-profit making, permanent institution in the service of society and of its development, and open to the public for purposes of study, education, and enjoyment, material evidence of man and his environment” (Sandahl, 2019; Lehmannová, 2020). Several museum’s literatures including the publication of 1984’s “Museums for a New Century” have also declared that “education is the primary purpose of museums” (American Association of Museums, 1984).

In 1992, the American Association of Museums (AAM) issued a landmark document entitled “Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums” highlighting the museum’s obligation to public education of every age (Cochran Hirzy and American Association of Museums, 1998). While the United Kingdom’s Museums Associations (MA) agreed on a definition for a museum in 1998 stating that “Museums enable people to explore collections for inspiration, learning, and enjoyment (etc.)” assuring that learning is among the core roles of museums, which imply that museums moved from the education programs oriented towards children to learning individuals of all ages through an enjoyable experience (Museum Associations, 2020). In the late 1990s, museums incorporated digital technologies into their educational services seeking more engagement with the public (Hawkey, 2004; Jewitt, 2012).

Since the late 20th century, museum organizations have moved from objects-oriented museology to visitors-oriented museology- an approach that fosters the relationship between museums and the needs of their visitors (Velázquez Marroni, 2017; Coleman, 2018). This shift has been described by Stephen Weil as a museum movement “from being about something to being for somebody” acknowledging museums’ obligations towards serving the “public’s own needs and interests” (Weil, 1999, 2002). In doing so, museums are performing their public service roles by providing educational and learning experiences for the betterment of society (O’Neill, 2002; Silverman, 2010). By this time, museums have gone through a process of change asserting that educational responsibility is not museums’ sole active public-service role. Further, as “a vehicle for social integration,” museums have a great social impact on the quality of individuals’ lives and their communities’ well-being and can influence society and contribute to its development (Sandell, 2002, 2017; Silverman, 2010; Dodd, 2015).

In response to the pluralistic and rapidly changing society of the 21st century, the museum’s public service dimension has been expanded to support the inclusion of a broader spectrum of a diverse society (Silverman, 2010; McCall and Gray, 2014; Brown and Mairesse, 2018; Morse, 2022). The concept of social inclusion has been embedded into museums’ organizational policies and programs to embrace equality and empower marginalized individuals including PWDs (Sandell, 2003; Sandell et al., 2010; Fleming, 2012; Reich, 2014; Moore et al., 2022). Museums have been used as “social agencies” not only to impart education but also to bring moral values and social justice to society (Sandell, 2002; Tlili, 2008; O’Neill, 2011; Sandell and Nightingale, 2012; Brown and Mairesse, 2018; Janes and Sandell, 2019). Most recently, there is a widespread acceptance of the museum’s role as “an agent for social change” in combating social inequality and promoting social justice and human rights (Sandell, 1998, 2002; Moore et al., 2022, 11–28; Morse, 2022, 10–19).

Despite that, the ICOM definition versions of 2002 and 2007 reemphasize the museum’s purposes as an educational and study facility as well as reaffirming the museum’s role “in the service of society and its development” (McCall and Gray, 2014; Brown and Mairesse, 2018; Sandahl, 2019) but still does not reflect the 21st-century museum’s commitments and the visions towards the future. Therefore, the ICOM seeks its members and interested parties to partake in a more updated definition that expresses the museum’s responsibilities toward the sustainable, ethical, political, social, and cultural challenges in the 21st century. The newly approved definition by ICOM during the 26th ICOM General Conference in Prague on 24 August 2022 reads: “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing” (International Council of Museums (ICOM), 2022). Phrases such as “Inclusivity,” “Accessibility,” “Diversity,” “Sustainability,” and “operate/communicate ethically” present expanded roles of museums’ educational and social responsibilities that involve the entire museum organization to be operated by equal justice initiatives and to engage in developing sustainable solutions toward respecting human rights and social justice (Cândido and Pappalardo, 2022).

Museum educational and social roles are constantly stretched with new possibilities and changes to be more socially relevant to their visitors (Dodd, 2015), support human rights and diversity (Sandell, 2017; McGhie, 2020), and combat social inequalities (Sandell, 1998, 2002, 2017; Janes and Sandell, 2019). Interestingly, these emergent notions of inclusion, diversity, and supporting disability rights have penetrated the museums’ context and become central to exhibitions and displays in the United Kingdom (Sandell et al., 2010; Dodd, 2015), United States (Reich, 2014, 2–8; Moore et al., 2022, 60–64), and other examples worldwide (Martins, 2018). The representations of disability and portraying PWDs in a series of exhibitions narratives with explanatory materials and educational resources are becoming broadly accepted practices among the inclusive approaches of museums toward challenging stereotyping, and prejudice, and framing society’s perceptions of disability through the lens of the social model (Delin, 2002; Sandell and Dodd, 2010; Dodd, 2015; Martins, 2018). No doubt that this approach is contributing largely to institutional changes in society’s perception of disability culture and promoting positive attitudes and tolerance towards the rights of PWDs.

From this point, as “institutions with moral functions” (Hein, 2000, 106), museums have a moral responsibility to promote the rights of access of all people to quality education (Fernandes and Norberto Rocha, 2022, 1–2) and democratization of knowledge that caters to all including socially vulnerable groups and PWDs (UNESCO, 2016). In doing so, museums are cooperating with PWDs, as protagonists and professionals, in eliminating barriers and offering more accessible environments and services to ensure physical, intellectual, attitudinal, and communicational access for all visitors with disabilities (Walters, 2009; Antoniou et al., 2013; Rocha et al., 2020). Several educational programs and activities target school children with disabilities are demonstrated to enable them to learn, enjoy and interact with exhibits without any barriers (Antoniou et al., 2013; Kanari and Souliotou, 2020). Studies regarding the inclusion of PWDs in museum learning underline a range of organizational actions to ensure the sustainment of learning for SWDs and promote institutional inclusive practices (Reich, 2014).

Further, the role of museums -as a non-formal learning institution- in the education of SWDs has been subjected to intensive study and relevant practices (Dierking, 1991, 2005; Falk and Dierking, 2000, 2016; Hein, 2002; Hooper-Greenhill, 2007; Reich, 2014). Several principles and theoretical frameworks have been developed to support their education. Differentiated Instruction (DI), the Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts & Mathematics) are among the different models that have been adopted in the museums’ context in alignment with the school curriculum to promote engagement, motivation, and inclusion in the learning process for children with disabilities (Kanari and Souliotou, 2020).

3. Interpreting disability in Egypt and claiming rights

Disability is a global rising concern that is perceived differently in numerous controversial ways. According to “The World Report on Disability” published by World Health Organization (WHO) (2011), disability is conceived as “an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions, referring to the negative aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors)” (World Health Organization (WHO), 2011, 4). Similarly, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities defines persons with disabilities as “those who have long term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (United Nations, 2006, 1).

In Egypt, the person with a disability is defined, according to Law no. 10 of the year 2018 (article 2) as “any person who has a full or partial disorder or impairment for a long-term be it physical, mental, intellectual or sensory; if this disorder or impairment is stable; and which in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with the others” [(Law No. 10 of 2018, 2020, 6) 10 of the year 2018, article 2, p. 6]. Thus, the focus in these definitions is on long-term physical, mental, and sensory impairments that hinder the individual from full integration into society.

Disability is best understood globally through the disability models that reflect several conceptual framings in dealing with PWDs. In disability studies, there are many different models for disability. Four main models are the most prominent in understanding and perceiving the disability (Barnes et al., 1999; Thomas, 2007; Oliver, 2013; Smith and Bundon, 2018). Two of them can be described generally through two main approaches: the individualistic medical approach opposed to the social approach (Barnes et al., 1999). The medical approach is regarded as a functional limitation of a person’s disability in which he/she is perceived as a patient in need of medical health care (Shakespeare, 2014; Baglieri and Shapiro, 2017). While the social approach to disability -that is developed in the 1970s as part of the disability movement in United Kingdom-perceived disability as a disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by a contemporary society that fails to meet the needs of people with impairments (Stone, 1999; Shakespeare and Watson, 2001; Shakespeare, 2014). It is, therefore, supporting the need for improvements in the social, physical, and attitudinal environments to enable PWDs to participate in society on an equal basis with others, and thus is the groundbreaking civil rights-based approach to disability that supports an inclusive society for all (Baglieri and Shapiro, 2017).

The other two models are described as the social-relational model and the human rights model. The social-relational model derived its roots from the critiques of the social model and social relationships between people that construct and enact disablism and disability (Smith and Bundon, 2018; Sang et al., 2022). It conceptualized several forms of social oppression and ‘ableist’ practices people experience in an attempt to change policies and practices to shift from ableism to inclusion (Thomas, 2004, 2007; Smith and Bundon, 2018). Unlike the social model and the social-relational model that recognize disability as an outcome of social process, the human rights model, as the name suggests, is underpinned by the basic principles of human rights in which PWDs need to participate in all aspects of society on an equal basis with their non-disabled peers (Degener, 2016; Smith and Bundon, 2018).

Despite that the disability condition in Egypt has improved over the past decades, but, as in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa-MENA region, the medial individualistic model of disability is still the dominant paradigm in Egypt (Zakaria, 2020). Egyptian society still prevailed with inaccessible built environments that caused the exclusion of PWDs in the various sectors, whether education, health, transportation, or otherwise (Hagrass, 2005; Lord and Stein, 2018; Elhadi, 2021). Additionally, there are still many social, cultural, and economic barriers that need to be eliminated to enable the inclusion of PWDs in social and economic activities in the country (Hagrass, 2005; Zakaria, 2020).

3.1. Legal delineation

The article 81 of the current Egyptian constitution of 2014 asserts the state’s full commitment to the rights of people with disabilities. It stated, “The state shall guarantee the health, economic, social, cultural, entertainment, sporting, and educational rights of persons with disabilities” (Constitute, 2017). Unlike the Rehabilitation Law 39 of 1975 which focuses on social insurance and pensions for citizens with disabilities, the new disability legislation -Law No. 10 of the year 2018- granted equality of opportunities and inclusion for PWDs in all sectors. It ensures that PWDs enjoy all their human rights on equal bases with others and supports their full integration into society as well as adopts inclusive environments and rehabilitation programs to ensure that PWDs exercises their rights and freedom equally with others (Zakaria, 2020).

There is no doubt that this new legislation reveals positive developmental reforms in supporting the rights of PWDs in all sectors of the state including health, legal protections, employment, political activities, and cultural rights. Further, it includes provisions for the rights of persons with disabilities in education at all levels. Despite these legislative reforms toward the inclusion of PWDs in Egyptian society, they are poorly enforced on the ground. There are still many detailed regulations and measures that need to be issued to effectuate the law’s provisions and put them into practice together with the concerned official bodies.

As part of the international obligation towards human rights, Egypt has signed the international convention of human rights and has formally recognized that all people have certain civil, political, economic, social, cultural, and development rights (Rioux and Carbert, 2003). In 2008, Egypt signed and ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD). Based on article 33 of the CRPD, Egypt established “the National Council for Disability Affairs” in 2012 (United Nations OHCHR, n.d.). This council was replaced in 2019 by “The National Council for People with Disabilities” in accordance with Egyptian Law No. 10. The goal of this new council was to develop strategies for the rehabilitation, inclusion, and empowerment of PWDs.

3.2. Inclusive education of students with disabilities in Egypt

Inclusion in education is considered a basic human right for every child (Srivastava et al., 2015; UNESCO, 2020). Inclusive education focused mainly on students with disabilities (SWDs) and their rights to be educated and attend regular schools. It emerged from the 1994’ Salamanca Framework for Action on Special Needs Education which acknowledged education as having an essential role in eliminating discrimination and promoting social justice and thus encouraged governments to stop segregating educational provisions for children with disabilities to ensure schools “…accommodate all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, linguistic or other condition” (UNESCO, 1994).

It has been spelled clearly in the article (24, b) of the CRPD to ensure “an inclusive education at all levels and lifelong learning” for all PWDs. It has referred to the rights of SWDs as “access an inclusive, quality, and free primary and secondary education on an equal basis with others in the communities in which they live” (United Nations, 2006).

UNESCO defined inclusive education as “a transformative process that ensures full participation and access to quality learning opportunities for all children, young people, and adults, respecting and valuing diversity, and eliminating all forms of discrimination in and through education” (Cali Commitment, 2019). As term inclusion refers to respect for diversity, equal opportunities in education, and universal human rights that allows all students to have access to education regardless of their strengths, weakness, abilities, and disabilities. It is an approach that obligates preschools, schools, and other educational settings to promote a school-child-friendly learning environment for all children including those with disabilities. Even though the terms ‘inclusion’ and ‘integration’ are not the same, they are used interchangeably in referring to the practice of educating SWDs. Integration is more about mainstreaming SWDs in regular classrooms, but inclusion is associated with accommodating all children (Wapling, 2016). The term inclusive education has been stated several times in Egyptian disability Law No. 10 of 2018. Yet, no specific definition was provided, nor elaboration was found.

The educational system of Egypt is classified as one of the largest education systems in the MENA region (PWC, 2017). The structure of Egyptian education is based upon an extremely centralized and hierarchical framework. On its top lies the Ministry of Education, which is responsible for developing and monitoring education-related policies, curriculum development, and overall educational plans (Ministry of Education, 2014). According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), the number of total enrollments of Egyptian students in 2019/2020 basic education is over 19.7 million students, in addition to 1.5 million children registered in Kindergarten (KG) (Central Agency for Mobilization and Statistics (CAMPAS), 2020). The general education stages (the pre-university education) are divided, respectively, into primary (6 years), preparatory (3 years), and secondary (3 years). These 12 schooling years make up compulsory basic education through two types of schools, namely public schools, and private schools (ElRashidy, 2017, 25–36). While the CAPMAS announced that approximately 15% of the Egyptian population who are 5 years and older have disabilities, there is a lack of data and statistics on the number of SWDs in education (Central Agency for Mobilization and Statistics (CAMPAS), 2017; Zakaria, 2020).

In 2013, the Ministry of Education reported that 7–10% of students enrolled in the education system have disabilities ranging from physical, and intellectual disabilities to visual and hearing impairments (Handicap International Humanity and Inclusion, 2022). The education of SWDs is entrusted to the General Directorate for Special Education, which is affiliated with the Ministry of Education. It is responsible for developing educational services for SWDs through three main departments, namely, the visual disability department, the hearing disability department, and the intellectual disability department (Elhadi, 2021; Ministry of Education, 2021). The SWDs are enrolling in public education schools where special independent classes are designed for them, or in special education schools which is the prevailing model in Egypt.

Recently, several efforts have been made to integrate SWDs into well-equipped schools after Egypt’s endorsement of the CRPD (Hassanein et al., 2021). The educational provisions for SWDs were clearly stated in many Ministerial Decrees issued by the Ministry of Education including the Ministerial Decree No. 42 of the year 2008 which ensured the formulation of a specialized committee aimed at the promotion of SWDs’ inclusion in public education as well as developing an operational framework to put this aim into practice. In addition, Ministerial Decree No. 94 of the year 2009 ensured the inclusion of children with mild disabilities in all stages of the public school (Elhadi, 2021).

Following the strategic plan of the Ministry of Education for pre-university education (2014–2030), which is part of Egypt’s Vision 2030 -Sustainable Development Strategy- SDS (Ministry of Planning, Monitoring and Administrative Reform, 2015). The Ministry of Education is committed to ensuring the rights of every child to equally obtain a good-quality education allowing him/her to contribute effectively to society including all SWDs (Ministry of Education, 2014; ElRashidy, 2017, 25–36). It affirmed the full integration of children with minor/basic disabilities in pre-university schools. At the same time, improving the current services and accommodations in special education schools. In response to these strategic goals, the ministry updated the aforementioned Ministerial Decrees in 2015 to mandate the admission of students with mild disabilities into all stages of the education system, whether in public or private schools. This resulted in the establishment of new schools dedicated to SWDs along with the promotion of accessible infrastructure to help fully integrate SWDs into the education process (Ministry of Education, 2014).

Despite this progress, SWDs are facing major barriers in their education. Their integration into mainstream public education and community schools is only partial with very limited quality education and rigid curricula. They lacked accessible utilities, equipment, teachers’ preparation on inclusive education strategies, and inaccessible physical and remote learning environments. Not to mention the weak enforcement of the laws and the challenges of applying the commitments to inclusive education as outlined in CRPD (ElRashidy, 2017; Elhadi, 2021; Hassanein et al., 2021). Limited data on out-of-school children with disabilities in the national education system is hampering the progress in inclusive education as they remain invisible (Hassanein et al., 2021; Handicap International Humanity and Inclusion, 2022). Further, attitudinal barriers and misconceptions by the community about disability led to a lack of recognition of the importance of education for SWDs, especially in rural areas and among those who are refugees. Also, stigma and discrimination led to bullying against SWDs and segregation of them in the education system where they faced several barriers in the learning environment (Handicap International Humanity and Inclusion, 2022).

In this respect, Egyptian museums, as non-formal and informal educational institutions, can contribute to the practices of inclusive education and support the learning of SWDs beyond their formal education system. As educational service providers, museums can develop useful learning resources in collaboration with schoolteachers to improve the education of SWDs (Antoniou et al., 2013; Kanari and Souliotou, 2020). Moreover, they can contribute to societal changes in Egypt, more precisely, changing disability-related narratives and thus accelerating the inclusive practices and expanding the acceptance of the educational rights of SWDs as human rights. In adopting the new possibilities of what museums sought to be now, as acknowledged by the new 2022 ICOM museum definition, museums can act as generators for social movements to embrace inclusive practices, combat prejudice, and promote social justice in favor of SWDs.

4. Museum education and inclusive practices in Egyptian museums

Egyptian museums are collection-based institutions that originated as warehouses for storing and preserving excavation artifacts (Wendy, 2008; Zakaria, 2019, 540–541). Even though the nineteenth century witnessed a pioneering role in the field of museum education in Egypt when the Egyptologist Ahmed Kamal established a school attached to the Egyptian Museum of Bulaq, as early as 1882, funded by the Antiquities department to teach Egyptians; art, history, ancient Egyptian language, and other subjects related to the history of the museum collections (Said Louay, 2002; Baligh, 2005). There was a noticeable stagnation in the state of museum education in the later decades whereas Egyptian museums lacked any educational programs for the public as they have been largely represented and curated for tourists and scholars (Abd El-Gawad and Stevenson, 2021, 124–126).

Since the last quarter of the twentieth century, there was a notable growth in the number of Egyptian museums all over the country along with a significant increase in the number of Egyptian visitors and their participation in museums’ programs and events (Wendy, 2008; Mahmoud, 2012). The Egyptian museums became actively engaged in educational programs and social events with the public. They committed to “educating the native Egyptians about their heritage” through a wide range of educational and learning programs that targeted children, school students, families, youths, and adults (Hawass, 2005). By this time, there was a remarkable expansion in the museum’s types, roles, and social activities. Several regional museums were created and spread in most of the country’s governates to educate the locals about the history of their regions, fostering their sense of belonging, and thus encouraging them to participate in museum activities (El-Saddik, 1993, 105–122). In parallel, modern art, site, historic house, ethnology, specialized, and antiquities museums were established and funded by the Egyptian government as part of the cultural agenda of the state (Wendy, 2008). The Egyptian museums gradually transformed from tourist-oriented museums to attracting more segments of local visitors.

4.1. Efforts to engage people with disabilities in Egyptian museums

Since the 1990s, the role of the Egyptian museums in educating children and youth was well-recognized when Egypt’s first lady initiate a plan to promote children’s education by using several state instruments, museums were among them (Baligh, 2005). This approach was supported by international organizations-the German Hans Seidel Foundation- which provided condensed workshops, activities, and special training on museum education from 1994 to 1996 to curators from different museums all over the country (El-Saddik, 1993; Baligh, 2005). Further, museological training courses for the museum personnel were designed by UNESCO, ICOM, and other international organizations to improve their skills and competence in all museum areas including the field of museum education (Mahmoud, 2012, 156–166).

This has resulted in delivering several educational programs at Egypt’s museums that were not limited only to the main national museums such as the Egyptian Museum of Cairo (EMC). Still, further, it was extended to many regional museums such as Tanta Museum, Port-Said Museum, Mallawi Museum, Luxor Museum, and Nubian Museum (Baligh, 2005; Hawass, 2005). This was alongside the launching of several initiatives by the Greco-Roman Museum of Alexandria to address children and individuals with disabilities of all ages, in cooperation with special education schools for SWDs as well as the Departments of Psychology, Sociology, and History at the Faculty of Arts of Alexandria University (El-Saddik, 1993; Baligh, 2005; Hawass, 2005).

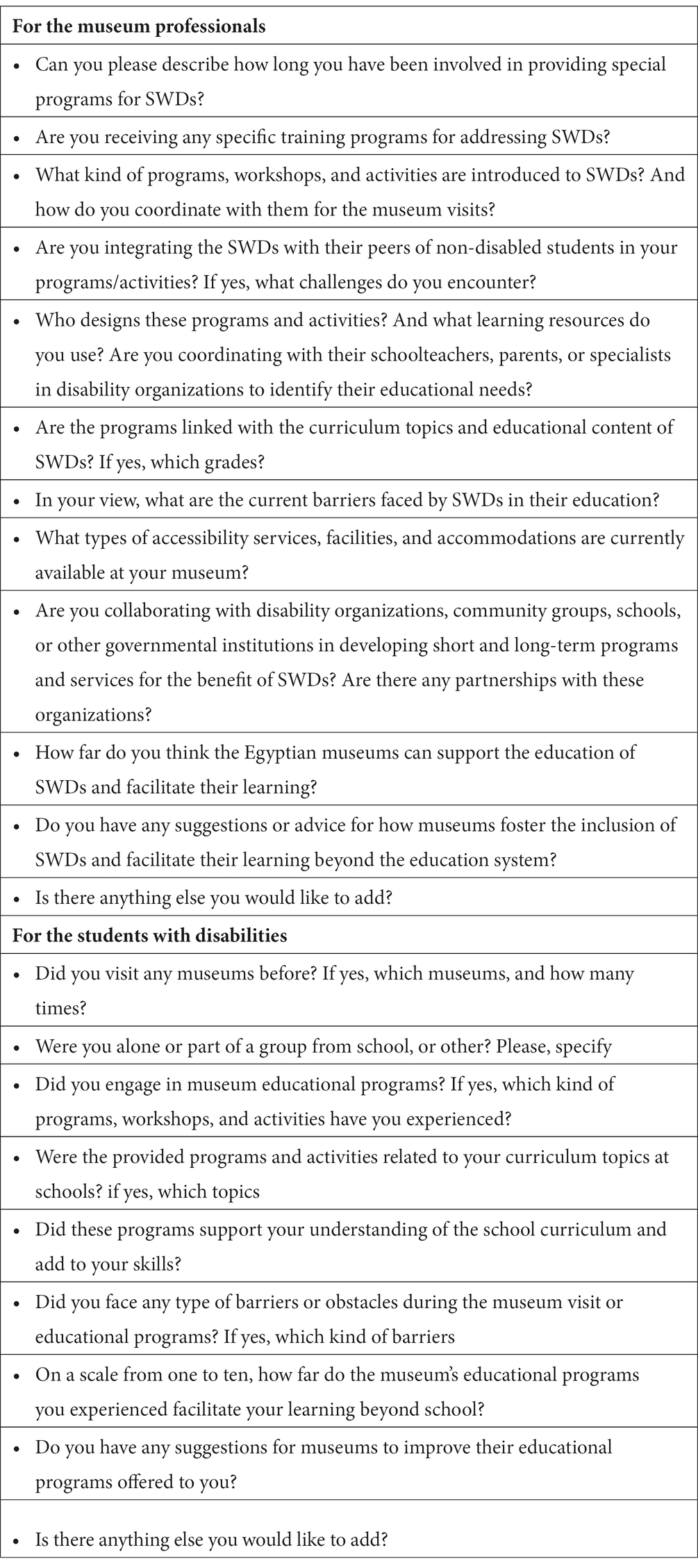

In 1996, the first museum for children was established by an NGO, namely, the Association of Heliopolis, in the Heliopolis area of Cairo, allowing the children to use all their senses to learn and interact with the exhibits and obtain knowledge by using technology (El-Saddik, 1993, 64–68). It has been expanded, remodeled, and fully completed in 2012. Following the re-opening of the children’s museum, it was renamed “the Children’s Civilization and Creativity Center-Child Museum” (Mallinson Architects and Engineers, 2023). It offers more engaging hands-on learning activities and welcomes a wider number of children along with their families (up to 1,200 schoolchildren each day; El-Saddik, 1993; Heliopolis Association, 2023; Mallinson Architects and Engineers, 2023). It was not until 2017 that the museum initiated special programs oriented toward SWDs. Since then, the museum is working regularly with special needs schools and disability organizations to offer a variety of programs, activities, and workshops for kids and children with disabilities, together with family and friends. One of the museum’s disability-specific programs is the “Edraak” Program that is focusing on improving the skills of children with intellectual disabilities as well as raising awareness of their rights to be fully integrated into society (Egypt Today, 2021; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Educational activities targeting SWDs- the “Edraak Program”, the Child Museum of Heliopolis.

In 2002, EMC founded a museum school– the Cairo Museum School- targeting school-age children with many school programs that were designed by the museum curators in cooperation with national and international schools to enrich the children’s knowledge in compliance with their curricula (Eldamaty, 2004; Baligh, 2005). In parallel, special education programs have been made to welcome visually-, hearing- and physically impaired students (The Egyptian Museum, 2009). Furthermore, several coordination arrangements were undertaken between the EMC and the Ministry of Social Affairs (Now, Ministry of Social Solidarity), and the National Center for Child’s Culture affiliated with the Ministry of Culture to create special education programs for blind- and hearing-impaired individuals (The Egyptian Museum, 2009). Also, Mobile Museum and outreach programs were carried out in public schools as well as special schools for SWDs to reinforce the educational role of the museum (Eldamaty, 2004). This school is the core foundation of the current Educational Department at the EMC that’s still actively working on providing educational and learning programs for the locals, school children, youth, and PWDs among other targeted visitors. In 2004, the growing support and interest in engaging children and individuals with disabilities were reflected by the establishment of the educational school/section at the EMC or the Visually Impaired School, as they are often referred to. The school aimed to provide regular educational programs and learning activities for all PWDs of all ages (Eldamaty, 2004; Figure 2).

In 2006, the foundation of the Children’s Museum in the EMC was a giant step forward in acknowledging the fundamental role of the museum in educating children of all ages alongside their parents (The Egyptian Museum, 2009). LEGO models, replicas, and artifacts were attracting children’s attention with their families who searching for an out-of-school education (The Egyptian Museum, 2009). Some special educational visits targeting SWDs, yet on a small scale, were carried out followed by workshops and activities aimed at improving their skills and knowledge after their visits (The Egyptian Museum, 2022).

The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC), one of the main national museums in Egypt, has formulated a policy for the development of comprehensive educational programs that target pre-school age up to older adults and PWDs (Abdel Moniem, 2005). Even though NMEC has opened recently but it was actively involved in providing educational programs and hands-on learning activities even before its official opening (Aboulnaga et al., 2022). Most recently, the NMEC initiate special programs for SWDs and other individuals with disabilities in cooperation with some disability-related institutions in Egypt (National Museum of Egyptian Civilization-NMEC, 2021; Figure 3).

The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) as a cultural complex and global education center for Egyptology is integrating the “Edutainment strategy; technological information system” in the implementation of the children’s museum (Mansour, 2005; Grand Egyptian Museum, 2023b). Multi-media applications and interactive educational activities were developed in joint teams of experts and professionals to increase the educational effectiveness of children/students of all ages (El Sheikh, 2020; Grand Egyptian Museum, 2023a). In addition, GEM is designing a variety of educational resources to support children’s school curriculums (up to 12 years; Grand Egyptian Museum, 2023b). Responding to the needs of children with disabilities, the GEM set up an ambitious plan aimed at promoting learning opportunities for SWDs and providing supportive informal learning materials in collaboration with schoolteachers and different disability organizations (Figure 4). Further, the GEM is adopting the necessary elements of accessibility and universal design standards in the museum building, exhibition galleries, and other GEM facilities to facilitate access to all PWDs physically and intellectually (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Educational Program for Students with Down Syndrome at the Grand Egyptian Museum. Image reprinted with permission from the Grand Egyptian Museum.

Figure 5. Testing Hands-On Station by a Person who is blind at the Grand Egyptian Museum. Image reprinted with permission from the Grand Egyptian Museum.

In 2020, for the first time, an administrative department dedicated to PWDs has been established within the organizational structure of the museums’ sector. It is entitled “The General Administration for People with Special Needs” (GAPSNs) and is aimed at improving accessibility and providing special programs designed to meet the needs of the community of PWDs (Maspero, 2021). A specific unit for museum education of PWDs was, therefore, established at each museum affiliated with the GAPSNs to promote programs and services for PWDs. Undoubtedly, this new administration is asserting the responsibilities of the Egyptian museums toward the inclusion of PWDs as well as reinforcing their commitment to integrating them into society.

5. Methodology and research instruments

The research investigates the current practices of Egyptian museums towards SWDs and the educational programs that support their learning beyond the formal education system. It aimed to assess the potential of Egypt’s museums in facilitating learning for the SWDs as well as framing their responsibilities in advancing inclusive education and supporting the rights of PWDs. It asks two main questions: (1) How can Egyptian Museums work within their governing systems to support the learning of SWDs beyond their formal education system? (2) What are the current challenges impacting the practices of inclusive education in Egyptian museums?

The research plan was conducted with an extensive review of the literature on education and disabilities in museums in Egypt and internationally. The research was then drawn upon existing theories on the potentiality of museums’ pedagogical and societal tasks in supporting the education of SWDs. A qualitative approach was conducted to provide an empirical grounding of the current inclusion practices toward PWDs within Egyptian museums and explore the challenges and opportunities for facilitating learning for SWDs. Finally, field observation was performed.

5.1. Participants

A descriptive study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with twenty-eight participants. Twenty-three representatives were selected from museum institutions and administrative departments affiliated with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA)- the leading institution responsible for the museums of Egypt. They are varying between seven leaders from a variety of institutional departments at MoTA as well as sixteen museum professionals ranging between museum educators, heads of educational departments, heads of special needs units, along with the head of the accessibility team at the GEM. They were selected from eight different museums, which are as follows: National Museums (EMC, NMEC, GEM, Coptic Museum, Islamic Art Museum), Regional Museums (Malawi Museum), Historic House Museums (Gayer-Anderson Museum), and the Children’s Civilization and Creativity Center (Child Museum) that affiliated to the Association of the Heliopolis.

The museums selected for the study are the state museums of Egypt that bear significant impacts not only on a national level but also on an international scale. They all, except for the child’s museum, are affiliated with the MoTA which is responsible for coordinating between all the government museums and formulating strategies and policies for improving museums’ roles and effectiveness in the service of Egyptian society (Prime Ministerial Decree No. 85 of 2019). Further, EMC, NMEC, GEM, Coptic Museum, and Islamic Art Museum are Egypt’s most visited and influential museums. Examples of regional museums were considered to capture impacts in regional locations. Also, historic house museums were among the selected museums to enrich the study with the challenges of providing accessible educational activities in a historic building. At this point, it was important for the study to capture inclusive educational practices in other types of museums outside the governing framing. Hence, the child’s museum was selected to explore the effectiveness of its inclusive educational practices.

In an attempt to explore the perceptions of SWDs in the current inclusive programs offered by the studied museums, other in-depth interviews were conducted with five students with multiple disabilities (i.e., three with a visual disability, one with a physical disability, and one with mild intellectual disability) from different school stages to explore their concerns and advice for promote inclusively educational programs that can help in facilitating their learnings. The study’s participants from the educational departments helped in identifying the students and facilitated communication with them.

Intriguingly, some of the study participants are not only PWDs but further, they are key actors in managing the accessibility services, planning, and formulating the inclusion programs oriented toward the PWDs in the museums’ sector. The director of GAPSNs is himself a person with a disability (he is a person who is blind), as well as three other museum educators of the interview participants, are also PWDs (they have physical and sensory disabilities). This recruitment of PWDs in permanent positions in the organizational structure of the museums’ sector is not only useful for increasing the inclusion of PWDs in the workforce but also comes in response to the necessity of reflecting the voices of PWDs and improving their representation in the museums’ sector in an attempt to address the interests and needs of users with disabilities and enhancing their services and facilities in the museum experience. It is worth mentioning here that the above-mentioned participants were the nucleus of the Museum Education Department at the EMC and led several educational programs for SWDs since 2004 till the present not only on the scale of EMC but on the wider scale of other museums at the MoTA.

5.2. Data analysis

A preliminary analysis was conducted in the first section derived from the review of the literature review and focused on museums’ contribution to informal and non-formal education as well as their societal obligation towards advocating the rights of PWDs. As part of the study investigation, a thorough analysis of the history of museum education in Egypt and the educational practices at Egyptian museums was provided to elaborate on the potential of museums to support inclusive educational practices.

Then, a comprehensive analysis was undertaken using in-depth qualitative interviews combined with observational notes taken during the interviews. The practices of the Egyptian museums were analyzed and discussed through one-to-one interviews with each of the participants virtually using the Zoom platform to assess the ongoing educational programs and inclusion practices that target PWDs, as well as explore their concerns and advice for promoting educational opportunities for SWDs and widening the Egyptian museums’ societal tasks to support their rights in inclusive education. The interviews were conducted in Arabic since the participants were Egyptian museum professionals. It was then transcribed verbatim, translated into English, arranged, and categorized according to the emergent topics and discussions around barriers to engaging with SWDs, restrictive environments, museums’ potential in facilitating learning of curriculum content, and possible collaboration and opportunities. The collected data was analyzed and sorted according to the research scope and aims, the emergent themes in the interviews, notes, and video recordings. The questions that were used as the basis for the interview are in (Table 1).

5.3. Results and findings

Over the past decades, Egyptian museums have stretched their work across several socially purposeful activities targeting the local community. Currently, almost all the museums of MoTA have some form of educational program or resources oriented toward people with disabilities including SWDs. This approach has been supported by the establishment of a specialized administrative division in each museum affiliated with the GAPSNs and obligated to provide educational programs for all PWDs. Prior, these disability-related programs were performed under the umbrella of the educational sections/departments at museums.

The results of the study revealed that Egyptian museums have already contributed to the learning of SWDs through several activities and workshops, yet short-term programs and individual efforts, but they affirmed the potentiality of Egyptian museums in supporting learning beyond the formal education system of the state. From the perspective of museum professionals, the study witnessed a growing awareness and willingness by the museum staff to expand their museum tasks to be more inclusive as voiced in many responses including this comment: “There is growing attention to the disabled people’s programs at the ministry reflected in expanding the collaborative relationships with disabled organizations, increasing social programs, and improving the accessibility in the museum buildings. In the past, these practices were out of our obligations as museum staff.” They are very keen to embrace the rights of PWDs, mainly the SWDs, support their learning, and contribute to eliminating their exclusionary educational practices.

Similarly, the perspective of the SWDs admits the supportive role of museums in improving and facilitating their learning. All five students agreed that the programs they have experienced at the museums contributed effectively to their understanding, knowledge, and skills. In this respect, one of the study interviewees, a student with a visual disability, has emphasized that the learning programs he experienced at the museum have brought additional knowledge to his learning process, specifically the touch tour, whether touching original artifacts or replicas, he stated.

“The touch tour helped me to complete my mental perception of many historical topics related to school curricula, such as the sphinx which I had no idea what meant to be a lion’s body and pharaoh’s head. Now I realized what it is and how it has been created in the past.”

Another student with mild intellectual disabilities highlighted how the museum activities increased her performance in art activities-drawing and painting- and allow displaying her drawing together with her colleagues’ drawings in an art exhibition inside the museum:

“I liked these activities a lot because I can mix the colors and create better-colored drawings. The museum program raised the quality of my paintings and drawings. I was very happy when I saw my drawings displayed at the museum.”

Undoubtedly, Egyptian museums possessed some of the essential factors needed to provide meaningful learning opportunities for SWDs and stimulate their abilities and social skills. These factors are included but not limited to; museum-collection that is used as starting point for dialogue-based learning, curricula-related objects, some audio-visual services, art and crafts activities, fun field trips, performances, drama and theatre, outreach-educational programs, not to mention the desire and moral responsibility of the staff among other museum pedagogical tools.

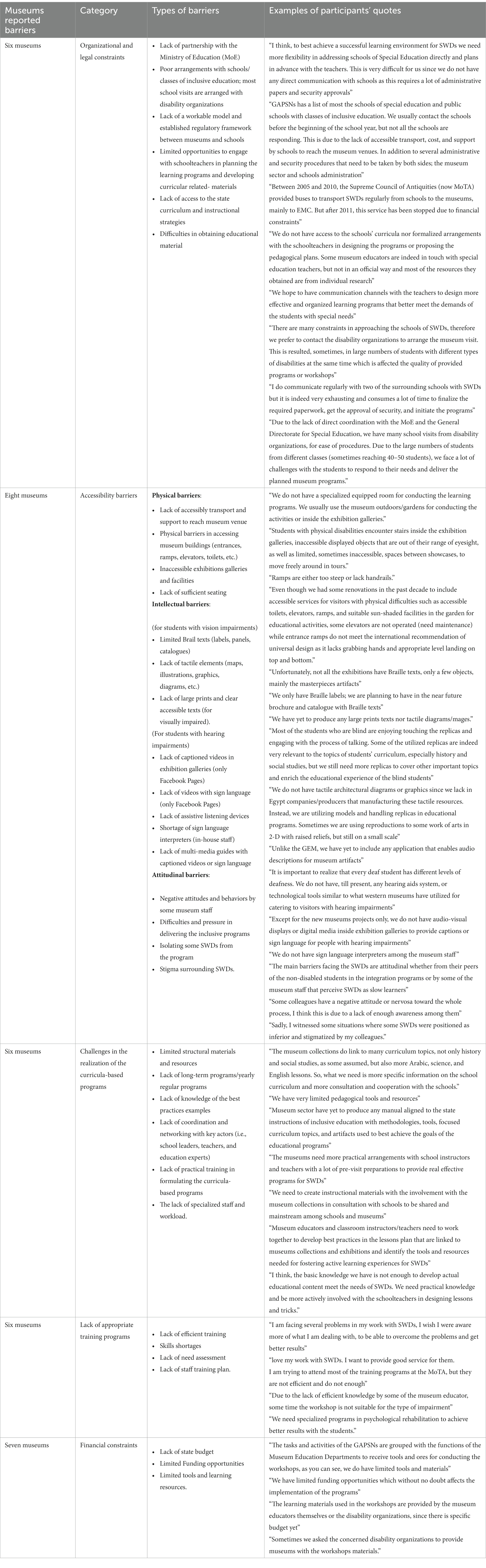

Nonetheless, the study also revealed multiple barriers at the Egyptian museums and challenges that directly impact practices of inclusive education. Several classifications worldwide examined and classified barriers to disability and inclusions of the PWDs (Leahy and Ferri, 2022). Following the world report on disability, the main barriers that hinder the inclusion of PWDs are recognized as (1) inadequate policies and standards, (2) negative attitudes, (3) lack of provision of services, (4) problems with service delivery, (5) inadequate funding, (6) lack of accessibility, (7) lack of consultation and involvement, and (8) lack of data and evidence (World Health Organization and World Bank, 2011). The study used this context to analyze and sort the barriers thematically as emerged from the answers of the interview respondents, which can be categorized as the following (see Table 2).

Table 2. Barriers sorted as emerged from the answers of the interview respondents (museum professionals).

5.4. Constraints related to organizational and legal aspects

Most of the respondents marked concerns about constraints related to formalized coordination with schools of inclusive education as well as partnerships with the Ministry of Education to develop a regulatory framework allowing direct arrangements with schools, consolidating knowledge with the school-based curricula, and thus more effective and regular programs designed for SWDs (see Table 2). Unsurprisingly, there have yet to be any institutional partnerships developed between the Ministry of Education and MoTA targeting inclusive practice for SWDs.

While two museum educators have reported that they coordinate with surrounding schools of disability education, the majority indicated that it is preferable to communicate with disability organizations and civil society associations, for the ease of security procedures, as these bodies are taking the responsibility for arranging with the concerned schools to institute the planned museum visits. One of the participants voiced a strong belief that disability organizations are more supportive of the museums’ programs towards SWDs than schools stating that “Communicating with disability organizations to organize learning programs for SWDs is much easier and faster than schools. They are keener than schools in cooperating with the museums.”

Even though such arrangements, that have taken place by these bodies, are alleviating the burden of time delay, and facilitating access to the museum programs, it resulted in school visits of different educational levels and sometimes even varied impairments at the same time. In this line, all the museum educators stated that they face a lot of problems when conducting programs for SWDs of different levels of education or disabilities as this would compromise the effectiveness and the quality of the provided programs, as one of the participants stated “Do you think the inclusive program can be successful with large numbers of students with different types of disabilities at the same time? This is affecting the quality of the program and compromising the ability of the students to learn.”

In the context of the structured information-based programs and their linkage with the school curricula, most of the participants assured of their keenness to provide activities and workshops related to the curriculum topics and educational content of SWDs yet missing a workable model with curriculum guidelines to be used as a framework for the educational plans (i.e., curricular topics for each grade, instructions, tool/materials used, assessment). One participant commented, “We do not have yet a template with instructions in the museum sector to be used in the planning of the educational programs.”

However, participants indicated that they consider the curriculum of all three education stages, namely, primary, preparatory, and secondary, with extra attention being given to the primary and preparatory. However, these are individual efforts with very limited opportunities to coordinate and engage with schoolteachers in designing these programs and activities or proposing any pedagogical plans to help the successful inclusion of SWDs, “having regular communication channels with the schoolteachers for the pre-planning of the museum programs would definitely improve the quality of the programs and educational activities and contribute to a better learning experience for the SWDs. But we do not have yet any formalized cooperation with schoolteachers,” commented one of the participants.

Further, the majority have raised concerns about not having access to the state curriculum instructions to help develop more effective programs “Unfortunately, we do not have access to the state resources of inclusive education.” This is due to the lack of formalized arrangements with the Ministry of Education and its affiliated schools and concerned departments.

5.5. Accessibility barriers; physical, intellectual, and attitudinal

Most of the museums in Egypt, mainly the national museums, are difficult to be visited by people with physical disabilities due to many architectural barriers and obstacles (Zakaria, 2020). Since the foundation of the GAPSNs in 2020, several accessibility audits were carried out to assess the museums’ buildings, exhibition areas, and facilities to improve accessibility accommodations for PWDs (Figure 6). In response to this commitment, guidance on accessibility recommendations and local guidelines were formulated by the GAPSNs in cooperation with experts from the concerned disability organizations.1

Figure 6. Assessing the accessibility services (brail labels) for the visually impaired at the Islamic art museum.

Despite the recent efforts that have been made by the MoTA for improving accessibility and developing services for PWDs in Egyptian museums and archeological sites (such as accessible toilets, ramps, elevators, etc.) (Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, 2021) but there are still major barriers reflected in the participants’ responses as they have indicated that the current physical environment and infrastructure conditions have limited accessibility for SWDs. As emerged from the interview respondents, the movement inside exhibition galleries and museum facilities is inaccessible, not only for students with physical impairments but also for blind individuals. This was grounded on the accessibility audit guidelines provided by the GAPSNs.

In this respect, one of the students echoed this concern stating that “I was tired on the guided tour. I encountered some physical barriers in accessing the toilet and some display cases. Even though the toilet itself was accessible and usable for me but the way leading to was very difficult.”

“Some wheelchairs have been donated by NGOs, but still very few,” commented one of the interviewees of the museum professionals. Some enhancements have been implemented by some international organizations, such as UNESCO in the case of the Gayer-Anderson Museum, to improve accessibility accommodations and visitor services (Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, 2022). The development of these services is still restricted only to the ground floor and accessible toilets with no access to the museum building and the other floors. One of the students reported: “Even though the museum staff used a virtual tour via mobile to show us the rest of the museum galleries on the second floor, I wished the museum has an accessible elevator to enable me to explore the second floor and roof myself.”

Some of the museums lacked dedicated spaces or galleries that can be easily reachable by SWDs for educational purposes. As for the entrance ramps, “they are not compatible with the principle of universal design in terms of size, sloping degree, and handrails,” as highlighted by one of the participants.

On an intellectual and sensory level, most of the museums have incorporated a modest level of intellectual accessibility that varies from one museum to another. Braille labels, a touch tour, and replicas models are among the common services that target blind people in the majority of museums. Some museums such as EMC have recently adopted electronic audio devices accompanying the Braille labels to provide more engagement with the museum’s key artifacts (Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, 2019).

Aside from this, there are limited Braille texts and provisions. Only one of eight museums-Gayer Anderson Museum- has reported that it developed a Museum Catalogue in Braille in cooperation with the Blind Association as stated by one of the participants: “We have developed a Braille Catalogue for the first time to be distributed to schools of special education which faces difficulties in visiting the museum.” There is also an absence of any tactile elements such as maps or illustrations, no large prints, labels/panels font size is very difficult to read by visually or partially impaired students as well lacking contrasting colors. One of the partially sighted students said that “the labels and panels texts are too small and too difficult to read, and there is no brochure with large prints.” Interestingly, the EMC has recently created a tactile path for visually impaired people in cooperation with the State Tactile Museum of Omero (Italy)2 together with special audio pens for explaining the artifacts on the route, but as reported by one of the interviewees” it is the only museum that has a tactile path for the blind people and audio pens for people with visual disability” (State Tactile Museo Omero, 2023; Figure 7).

Figure 7. Testing the tactile path for the visually impaired by museum educator from the visually impaired school at the Egyptian museum of Cairo.

As for students with hearing disabilities, the Egyptian museums have yet to take access measures for them, except for captioned videos or videos supported with sign language that are available only on the museum’s Facebook pages, as highlighted by the interview respondents. “We have this service available only on the Facebook page of the museum with the help of some experts from disability organizations that provided the sign language interpreters.” Another participant expressed how the positive impact of this service online stated that: “We have developed specific educational content in form of episodes on the Facebook page called “tales of our ancestors” supported with sign language to cater to students with hearing loss. They were actively engaged with it, and we received very positive feedback.” Another participant commented: “We have created partnerships with several deaf associations in Egypt to support our programs toward visitors with hearing disabilities.”

Museum-led tours for students with hearing impairments are presented only by sign interpreters that accompanied students from disability organizations. The study revealed that museum educators have limited knowledge of sign language and are not able to handle the tour guide and other-related programs without getting assistance from the concerned disability organizations or schools. In this concern, “We have this service available only on the Facebook page of the museum with the help of some experts from disability organizations that provided the sign language interpreters.” Another participant expressed how the positive impact of this service online stated that “We have developed specific educational content in form of episodes on the Facebook page called “tales of our ancestors” supported with sign language to cater to students with hearing loss. They were actively engaged with it, and we received very positive feedback.” Another participant commented, “We have created partnerships with several deaf associations in Egypt to support our programs toward visitors with hearing disabilities.”

Based on the approved architecture design of the GEM that was constructed by the Irish firm Heneghan Peng Architects, the GEM has integrated an adequate accessibility approach and universal design for PWDs based on British standards as stated by the one of study participants (Grand Egyptian Museum, 2023a). Accessibility and inclusion are inherent in the design of exhibitions, programs, and services to be accessible to all visitors, physically and intellectually without the need for adaptation or specialized design. Special companies- such as Acciona- were used to implement a variety of accessibility elements at the GEM, i.e., Tactile and interactive exhibit elements, hands-on stations, replicas, tactile routes, audio descriptions, assistive listening devices for the deaf and hard of hearing, captioning and subtitles and much more are services recognized at the GEM for the inclusion of PWDs (Acciona, 2020). Most recently, collaboration was made between the GEM and National Council for Persons with Disabilities to assess accessibility accommodations to best serve the need of the community of PWDs in Egypt.3

Interestingly, the study observed that the majority of museums set up special programs for students with developmental disabilities, such as Down Syndrome and Autism, in which they work closely with concerned schools and cooperate with associations for developmental disabilities in developing the appropriate programs or services.

The Child’s Museum, for instance, has developed partnerships with several disability-related organizations and schools to design effective programs targeting children with developmental disabilities which are the center of the museum’s vision towards SWDs as described by one of the respondents “social interaction, learning by doing and collaborations hand-to-hand with schools of special needs and disability organizations hold a central role in the museum agenda towards SWDs, mainly students with learning and developmental disabilities.” Social interaction is central to visitors with intellectual and developmental impairments (Gratton, 2020). These programs, therefore, aim to stimulate students’ interactions, advance their skills, and improve their intellectual, social, and cognitive abilities, as highlighted by one of the participants “We are adopting activities-related learning designed to stimulate the students’ interactions through ‘learning by doing’. We have a specific team of social specialists who studied psychiatry, in addition to fresh graduates of the Faculty of Education and Kindergarten, to facilitate active experiential learning programs.”

In doing so, the museum is utilizing curriculum related-content, hands-on activities, tactile activities, experimentations, etc., that are positively affecting their learning opportunities. This includes the “Edraak Program” that is stated above. It is a long-term program available the whole time of the year, unlike the other programs provided by the museums affiliated with the MoTA, which are available only on special occasions and events with fewer educational activities and resources. Perhaps, this is due to the fact that all the programs provided by MoTA’s museums are free of charge while the “Edraak” and other similar programs at the Child’s Museum are required fees to cover the cost of the programs and maintain their sustainability.

In this respect, many participants of the MoTA’s museums have voiced that they are facing a lot of difficulties in addressing children with developmental disabilities and facilitating their learning. This occurred especially in the integration programs that combined both children with developmental disabilities and their peers of non-disabled. Participants stated that they cannot manage the group which, in many cases, resulted in isolating the children by their teachers and leaving them behind in the galleries without a particular task. Given the significant challenges faced in practice, some of the participants indicated that there are major attitudinal and emotional barriers facing SWDs from both their teachers/facilitators and several museum staff, as stated by one of the students “I felt that attending the educational program at the museum was difficult for me. I felt bad when I was avoided by some of the museum staff who led the tour guide.” In this view, another student stated that “I faced a negative attitude from some of the museum security.” Some of the museum educators have explicitly reported some negative attitudes and behaviors of their colleagues during the programs, which are considered major barriers to the inclusion of SWDs.

5.6. Challenges in the realization of the curricula-based programs

As stated above, there is a lack of cooperation between the museums and schoolteachers in the planning and designing of the curricula-based programs which are, as agreed by all the participants, one of the main important factors for the quality of the programs and improving the learning experience of the SWDs. Several museum personnel pointed out that the museum exhibitions and collections had great relevance to many curricular topics of different school stages, but there is a lack of instructional materials, tools, and resources to provide more effective programs in favor of SWDs. The curricula-based educational content used for teaching SWDs was described by one of the museum educators as” weak and lacked needed resources that affected the quality of the programs.”

Part of the challenges highlighted by the participants was a lack of knowledge of the best practice examples in realizing the educational programs for SWDs or models with key elements that need to be considered in the planning of the content, process, and used tools, and thus “developing original museum-educational programs for SWDs” as added one of the respondents. This is due to the fact that there is no practical training provided to museum educators in planning the learning programs for SWDs, as the study witnessed.

Also, there is a lack of regular long-term programs as expressed by some of the museum personnel “These programs can be classified as events rather than well-crafted long-term educational programs especially since some of these activities and workshops are taking place on special occasions, such as celebrating the blind and white sticks, or the international day for disability (etc.) and not available during the whole year regularly.”

Another participant commented on this issue “Museum professionals should take part in advance in the planning and developing of SWDs curricula in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and create effective educational resources based on the museum’s collections.” Another highlighted the positive impact of museums’ activities on advancing the SWDs social skills: and abilities: “The museums are organizing several multicultural events and activities for SWDs including art and crafts workshops, performances, drama, competitions, marathons (etc.) that allow them to discover their utmost potential and utilize their diverse strengths and abilities to engage and win.”

The lack of specialized staff and workload were also reported as a barrier to the inclusion of SWDs. One of the participants stressed the shortage of staff as one of the constraints they faced in the implementation of the programs. Others assured the necessity of hiring teams from specialized faculties such as the Faculty of Education and Faculty of Arts, namely the departments of psychology and sociology, to provide the needed guidance and advice for the successful inclusion of SWDs into the Egyptian museums.

5.7. Lack of appropriate training programs

Training museum personnel to work with PWDs should be a museum-wide commitment to ensure access and inclusion to all on an equal basis. Training is needed to support staff with knowledge of accessibility issues, disability etiquette, and respectable language in addressing and communicating PWDs (Braden, 2016). In addition, raise their awareness about the behaviors and needs of PWDs to embrace them and promote their engagement with the museum programs. As appeared in some of the interviewees’ responses, there were some negative attitudes and behaviors identified by both museum educators and SWDs during the programs.

While adopting training programs at MoTA is important recently, to the extent that this results in a checklist approach in different departments to addressing attitudinal barriers and raising the awareness of the MoTA staff in different museums and archeological sites with disability issues and communication with people of different disabilities, it is unlikely to be sufficient.

Museum educators need more focused training which is, as agreed by most of the participants, “limited at the MoTA and does not meet our needs.” It was agreed by the majority of museum professionals that there are difficulties in dealing with SWDs during the educational programs due to a lack of specialized training, as stated by one of the participants, “We are encountering some difficulties in dealing with SWDs which made us more conscious of the necessity of having more focused skills training to meet what we truly need.” One of the museum professionals commented, “The experience of dealing with PWDs, and working closely with them and their organizations made me realize that I have deficits and need to improve my skills to provide better programs.”

According to the obtained results, there is no Need Assessment at the MoTA to determine the exact needs and gaps before providing disability training that is delivered by multiple centralized departments at the MoTA (i.e., Centralized Department of Training, Cultural Development Department, General Administration for the Development of Visitor Services at Archeological Sites and Museums). Further, “there is a lack of strategic training elaborating on who needs what” as stated by one of the museum professionals.

Despite that, all the museums of the study have indicated partnerships and cooperation with universities and disability-related- organizations for capacity building of museum staff in disability awareness training and basic communication in dealing with PWDs, there was a consensus among participants that this training is not sufficient with very limited opportunities to learn and practice new skills in addressing PWDs. Some participants criticize the training stating that” It is more of awareness lectures than a specialized training program with clarified objectives, methodology, and learning outputs.” Others highlighted the time allowed for these programs as “very limited time with only 2–5 days of lecture programs, which are not enough to gain appropriate knowledge.” Another added to this criticism, stating “There is no training toolkit, written guidance, or any helpful resources for obtaining new skills.” Comments of one participant highlight this point, “These kinds of training would be of importance for the staff of security and information desks to raise their awareness of the appropriate way in communication with PWDS, while the museums’ educators are required to have more specialized training to enable them to facilitate learning for SWDs.”

5.8. Financial constraints

Considerable evidence in the responses of the participants indicated that they have very confined financial resources in practicing inclusive programs for SWDs. This is due to the fact that the organizational structure of the General Administration for People with Special Needs (GAPSNs) is still under the approval of the State Central Agency for Organization and Administration, thereby, does not receive yet any allocated funds from the public funding of the state.

Most of the museum professionals have reported that they lacked learning materials that support their programs due to the limited budget. One commented, “It is very difficult to provide an inclusion program without a reasonable budget.” The majority have indicated that they bring the materials and tools with their own money to implement the programs adequately otherwise the programs will be limited only to the guided tour and oral interpretation which are, as emphasized by many, not efficient for the success of the programs. A participant said, “Sometimes we asked the concerned disability organizations to provide museums with the workshops materials.” Some others added, “They have very innovative ideas to enrich the programs with explanatory materials and useful elements that can effectively support the curriculum content but unfortunately they lacked the budget and resources to invest in SWDs programs.”

6. Discussion

Undoubtedly, there are strong willingness and endeavor from the Egyptian museums to expand their roles in the education of SWDs and support their learning experience. In the past few years, Egyptian museums have increasingly promoted several educational programs and activities aimed to improve the learning of SWDs beyond their schools, taking into account curricula and school lessons. All of the analyzed museums assured the use of museum collections and exhibitions to develop more curriculum-based educational programs and promote more learning opportunities for SWDs- yet with limited resources and funds. Despite these limitations in program-related resources and services, the impact of these programs is of great significance for the learning of SWDs and offers them a higher level of enjoyment and social interaction. “Teaching methods in schools are very traditional and focus more on facts and information,” highlighted one of the museum professionals. While museums as non-formal learning institutions are adopting different ways to provide exciting stimulating learning for all students including those with disabilities (Falk et al., 2006). In this view, another museum educator commented, “These programs are of great importance and bring a lot of enjoyment and joy to ordinary students, let alone students with disabilities.”