- 1Department of Educational Psychology, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya

- 2Department of Curriculum, Instruction and Media, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya

Introduction: Mental health literacy could be a protector from stress and other mental health problems. Statistics in sub-Saharan Africa estimate that up to 20% of children and adolescents experience mental health problems due to stress. Research has also shown that there is a bidirectional association between positive coping and mental health literacy. Nonetheless, little is known about stress levels, coping strategies, and mental health literacy of secondary school students in Kenya. This study sought to answer the following questions: What is the stress level of students in secondary schools in Kenya? What is the association between stress levels and coping strategies of learners? What is the mental health literacy level of learners in secondary schools in Kenya?

Methods: The study employed a sequential explanatory mixed methods research design by carrying out a quantitative study to ascertain stress levels and coping strategies and a qualitative study to explore the mental health literacy of the students. A total of 400 secondary school students aged 16–22 years participated in the study. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics whereas qualitative data was analyzed thematically.

Results: Based on these results, the majority of students were moderately 244 (66%) and highly 112 (31%) stressed. Only 11 students (3%) reported low stress levels. The study also indicated a positive significant association between stress and avoidance coping strategy (r = 0.11, p < 0.05). Qualitative data revealed varied conceptualizations of mental health. The following themes emerged: the students conceptualized mental health as help offered to people who are stressed to help them reduce stressors, others felt that it was a state of being at peace with one’s self and being able to think and act soundly, whereas others felt that mental health is severe mental disorder or illness. Students further attributed stress to school, peer, and home pressure.

Discussion: Lastly, although the students believed that seeking emotional, social, and psychological support was the best way to cope with stress, they feared seeking this support from teachers and peers. There was no evidence of students seeking support from parents. This study contributes to the Group Socialization Theory that suggests that peers become the primary social agents of adolescents outside the confinement of their homes. It provides essential information for developing awareness programs on mental health issues in Kenyan secondary schools. It also highlights a need to equip students with skills so that they can offer peer-to-peer support in times of distress.

Introduction

Stress among young people

Stress has been associated with mental health problems (Tuasig et al., 1995, 827). The most affected are individuals whose ability to cope with life stressors or change is less than the demands of the situation (Roy et al., 2015, 49). It is estimated that one in four persons will develop one or more mental health disorders at some point in their lives (World Health Organization [WHO], 2001). Young people in particular are of central concern pertaining to their experience of stress and mental health problems because of the psychological transitional changes that occur as they navigate through the adolescent stage (Holden, 2010, 208). This stage is characterized by rapid physical, hormonal, neurological, cognitive, and psychological transitional changes (Holden, 2010, 208). Adolescents also face challenges related to their home environment, school context, and relationship with their significant adults and peers (Darmody et al., 2020, 367). Mental health problems could be associated with a drastic increase in the suicide rate among adolescents over the past 50 years, which has become a public concern (Schneider, 2009, 267; Venkataraman et al., 2019, 2,723).

Research shows that during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, children and young people experienced high levels of stress and mental health problems (Owens et al., 2022, 1). A study in Israel (Revital and Haviv, 2022, 18) showed that the dynamics associated with the changes in life during and after the Covid-19 restrictions could have had remarkable consequences on young people’s mental health. The outcome of the distress could have been expressed by youths’ involvement in delinquent behavior. In Kenya for example, the rampant school fires and arsons in boarding secondary schools after the long closure of schools due to Covid-19 could be linked to stress among the students. It is estimated that 35 schools across Kenya were set on fire in 1 month forcing many to shut down just after long school closure and reopening (Yusuf, 2021). The situation was almost declared a national disaster because the unprecedented fire outbreaks outmatched previous years in frequency, scale, and depth (Moywaywa, 2022, 128). These fires occurred concurrently in various schools across the country and the damage caused was more pronounced compared to previous fires experienced in schools in Kenya. In their studies, Modi et al. (2020) reported that stress among the students which was associated with pressure to complete the syllabus early was one of the causes of school fires in Homa Bay County in Kenya.

Young people’s stress coping strategies

Effective coping and management of stress among young people can reduce the risk of mental health disorders and strengthen protective factors (Radicke et al., 2021, 2). Coping refers to the cognitive and behavioral methods that individuals use in the face of frustration (Mitrousi et al., 2013, 131). Emotional coping strategy influences individuals’ stress resolution and long-term mental health and shapes the attitude of individuals to seek help from others and professionals (Li et al., 2022, 2). The use of emotional support has been reported to be a good coping style for mental health wellness among adolescents (Maria de Carvalho and Vale-Dias, 2021, 281).

Emotional support as a coping style acts as a booster for mental wellness among adolescents by offering a safe space where they can express feelings of distress or loneliness and feel heard (Roohi et al., 2020, 2; Hu et al., 2022). Besides, emotional support has been reported to stabilize the mental conditions of young people and shape their resilience in face of stress (Li et al., 2022, 4). Unlike seeking emotional support, avoidance as a coping strategy relies on short-term distraction and stress reduction which may be harmful and dysfunctional in the long term (Abouammoh et al., 2020, 6).

Mental health literacy and mental health problems

It has been documented that mental health literacy is associated with better mental health outcomes (Maria de Carvalho and Vale-Dias, 2021, 281). People who know more about mental wellbeing may feel more capable and competent to face life challenges (Venkataraman et al., 2019, 2,723). Knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders aid in the recognition, management, and prevention of mental health problems (Jorm, 2000, 396). Thus, mental health literacy may boost mental wellness by acting as an effective prevention measure against mental disorders among adolescents (Tahlia et al., 2018, 1).

Nonetheless, the literacy level on mental health issues among young people in many developing countries is either poorly or inaccurately understood, yet it is among the key determinants of this population’s health outcomes (Ganasen et al., 2008, 23). Mental health illiteracy could be an obstacle in providing treatment for those in need in low- and middle-income countries. In addition, access to mental health care remains low in African countries partially due to the stigma associated with mental health problems (D’Orta et al., 2022, 1). It is worth noting that school children can be a medium for educating the rest of the community on matters of mental health (Ganasen et al., 2008, 28).

There was a proposal to introduce mental health literacy programs in Kenyan schools (Marangu et al., 2014, 4). The proposers argued that mental health literacy is a tool for the early identification, treatment, and management of mental health symptoms. However, since the proposal was shared with the education sector, there are still few works of literature on mental health literacy levels and coping strategies among students (Roy et al., 2015, 54). Taking this into consideration, the current study explored the perceived stress levels, coping strategies, and mental health literacy of students in secondary schools in Kenya.

Research questions

This study sought to answer the following questions:

1. What is the stress level among students in secondary schools in Kenya?

2. What are the emotional support or avoidance strategies used by students in secondary schools in Kenya?

3. What is the association between stress levels and emotional support or avoidance as coping strategies?

4. What is the mental health literacy level of secondary school learners in Kenya?

Theoretical framework

This study was anchored on Group Socialization Theory which recognizes the important role that peers can have on adolescents’ development. This theory states that peers have a greater influence on adolescents compared to their parents (Holden, 2010, 212). According to Harris (1995), who is the founder of the theory, parents are important determinants of behaviors inside the home, nonetheless, once a child is outside the confines of the home, peers become the primary social agents and the influences of parents and teachers are filtered through children’s peer groups. Harris suggested that adolescents seek to be like their peers rather than their parents, consequently, turning parent-adolescent conflict into a vital feature and challenge at this stage. This study sought to find out whether the peer socialization process influenced the coping strategies of adolescents when they are stressed.

Methodology

This study employed a sequential explanatory mixed-method research design. Specifically, a quantitative study was conducted to ascertain stress levels and coping strategies followed by a qualitative study to explore the mental health literacy of the students (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). A descriptive survey was carried out to understand the stress levels and coping strategies of secondary school students in Kenya. Based on the findings, focus group discussions were held to understand these associations and ascertain the level of mental health literacy among the students. The design was appropriate in understanding the extent to which students are experiencing stress and how they are coping with the problem.

Participants

In phase 1 of the study, four national schools including two boys’ and two girls’ secondary schools in western Kenya were purposefully chosen. National schools were suitable because of their national enrollment of students thus guaranteeing the inclusivity of students from different counties in the study. The study involved Form Four students. The Form Four students were favored as it was presumed that they were more likely to be stressed because of the uncertainty about the end of their fourth-year examinations which had been postponed because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, recalling them to school while the rest of the students remained at home could have also triggered stress. Additionally, phase 1 of the study involved 384 students. Random sampling was used by placing cards bearing the students’ admission numbers in a container and shuffling. Students who picked cards written “yes” were selected. Specifically, 151 (39%) boys and 233 (61%) girls were selected. In terms of age, 202 (53%) were aged between 18 and 19 years, 162 (42%) were between 16 and 17 years, and only 17 (5%) were above 20 years. This suggests that a majority of the respondents were in their middle and late adolescence stages of growth and development. The students were from 44 out of the 47 counties in Kenya. Specifically, the respondents were spread across the country as follows: Nairobi 48 (13%), Bungoma (11%), Kakamega (11%), Uasin Gishu 23 (6%), Kisumu 21 (5.5%), Kisii 20 (5.2%), and Nakuru 18 (4.7%). Counties with only one student (0.3%) were: Samburu, Turkana, Isiolo, Wajir, and Tana River.

Phase 2 of the study was conducted in two national secondary schools and one county secondary school in western Kenya. It employed the maximum variation strategy (Dicicco-Bloom and Crabtree, 2006, 317) to select a school each from the following categories of schools: boys’ school, girls’ school, and mixed boys’ and girls’ school. The number of participants in the study was limited to 30 Form Four students. The selection of fewer respondents for the study allowed an in-depth view of the phenomenon under study (Patton, 2015, 183). Purposive sampling was used to select the respondents. Pseudonyms (S1; S2; S3) were used to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of the respondents. Students who were aged above 19 years were excluded from the focus group discussion because they were believed to be past the adolescence stage. Besides, the quality of research in phase 2 was guaranteed through the application of several techniques including peer debriefing, member checking, and triangulation.

Data generating instruments and procedure

In phase 1, a biographic form was used to generate data on age, gender, and home county of the students. Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, 1994, 386) and Proactive Coping Inventory Scale (Greenglass et al., 1999, 5) questionnaires were used to collect data on perceived stress and proactive strategies, respectively.

Questionnaires were selected because the Perceived Stress Scale has demonstrated high internal consistency reliability of above alpha = 0.78 while the Proactive Coping Inventory has reported internal consistency alphas ranging from 0.71 to 0.85 for all the scales (Cohen, 1994, 386; Greenglass et al., 1999, 5).

A focus group discussion guide (Appendix A) was used in phase 2 of this study. It probed the findings of phase 1 and answered the fourth research question of this study, “What is the mental health literacy level of secondary school learners in Kenya?” This inquiry was informed by the fact that understanding the literacy levels of children and adolescents is essential in addressing their mental health needs and may influence their coping strategies.

A total of three focus group discussions were conducted for this study. Each group was made up of 10 students as per the recommendations by Merriam and Tisdell (2016, 114) that a suitable focus group discussion should comprise between 8 and 12 participants. In line with Taylor et al. (2016, 132) view, the focus group discussions lasted for 60 min during which the researcher encouraged the participants to talk to one another, ask questions, exchange anecdotes, and comment on each other’s experiences and points of view (Cohen et al., 2018, 532).

Analysis

In phase 1 of the study, perceived stress levels were grouped into lowly, moderately, and highly stressed as suggested by Manzar et al. (2019). Using this method, those whose scores were between 0 and 13 were considered to be having low stress levels, those whose scores were between 14 and 26 were considered to be moderately stressed, and students whose scores were between 27 and 40 were considered to be highly stressed.

Quantitative data were analyzed using frequencies, mean scores, and standard deviations.

Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient was also used to determine the relationship between perceived stress and seeking emotional support or avoidance. The level of significance for the statistical tests conducted in this study was set at α < 0.05.

In phase 2, thematic analysis was employed to develop categories or themes with reference to the research questions. Both inductive and deductive analytical styles were employed. Inductive analysis was used to build patterns, categories, and themes from the data into increasingly abstract units of information (Creswell and Creswell, 2018, 125). The deductive style used some of the codes that were generated by the quantitative data conducted in phase one (Creswell and Poth, 2018, 96). Thematic analysis using a six-step process (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 86) guided the analysis process. In particular, the analysis centered on immersion in the data through repeated reading of the transcripts, systematic coding of the data, development of preliminary themes, revision of those themes, selection of a final set of themes, and organizing and writing the final report.

Results

The stress level of students in secondary schools in Kenya

Respondents reported their feelings and thoughts about stress in the past 6 months. Findings showed that the majority of students perceived themselves to be experiencing moderate 244 (63%) and high 112 (31%) levels of stress. Only 11 students (3%) perceived themselves to be having low stress levels. Further analysis indicated that boys (M = 2.52, SD = 0.54) perceived themselves to be more stressed than girls (M = 2.24, SD = 0.54) (t = 4.55, df = 365, p < 0.01).

Coping strategies by the students in secondary schools

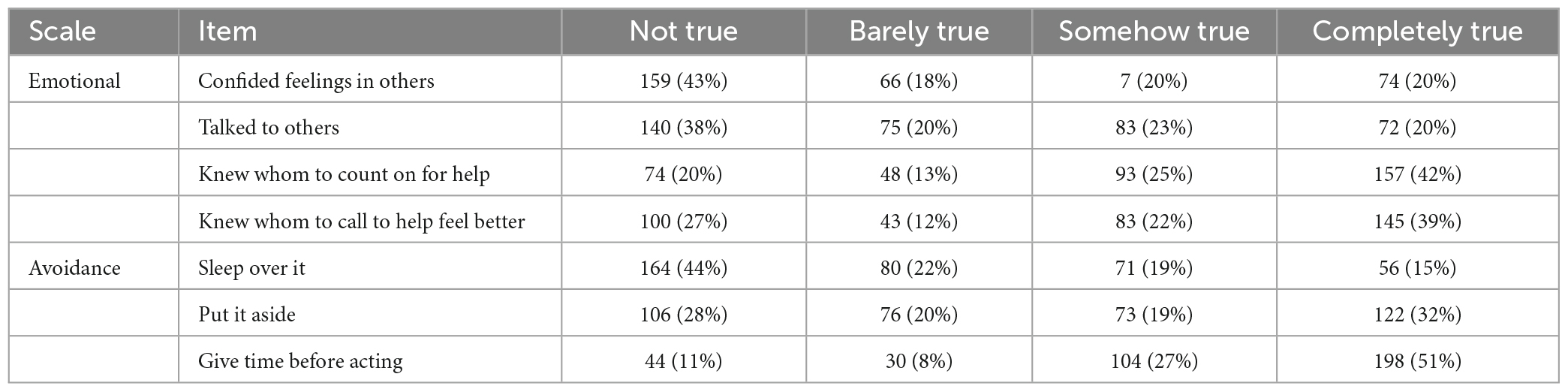

Frequency scores of the emotional and avoidance coping strategies used by the students were computed as indicated in Table 1.

The findings showed that the majority of the students knew whom to approach 157 (42%) or call 145 (39%) for help. However, only a few students 74 (20%) shared their feelings or talked to others. A significant number of students managed to sleep over their problems, while a majority put aside or gave the stressors time before acting. The findings suggested that whereas a small number of the students sought emotional support, the majority resorted to avoidance as a coping strategy. The results further revealed that there were no significant differences in the use of emotional support by boys (M = 0.15, SD = 1.82) and girls [(4.93, SD = 1.62) (t = 1.190, df = 357, p > 0.01)]. Similarly, there were no significant differences in avoidance coping strategy by boys (M = 2.63, SD = 0.74) and girls [(M = 2.59, SD = 0.73), (t = 0.50, df = 376, p > 0.01)]. This suggests that boys and girls employ similar coping strategies when stressed.

Stress levels and seeking emotional support or avoidance as coping strategies among students in secondary schools in Kenya

The third objective was to find out the association between stress levels and coping strategies used by students. Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient was computed. Findings indicated that stress was significantly associated with the avoidance coping strategy (r = 0.11, p < 0.05). There was no significant relationship between stress and the emotional support-seeking strategy. The findings suggested that an increase in stress levels among the students increased their tendency of avoidance as a means of addressing the stressors.

Mental health literacy of secondary school learners in Kenya

Phase 2 of this study explored the mental health literacy level of secondary school learners in Kenya. Specifically, it investigated the conceptualization of mental health and seeking help as a means of coping. This inquiry was informed by the fact that understanding the literacy levels of children and adolescents is essential in addressing their mental health needs and coping strategies. This second phase of the study was also informed by the findings of phase 1 which indicated that students were stressed and that there was an association between stress and avoidance as a coping strategy. We sought to explore whether mental health literacy could be a contributing factor to this finding.

Students’ understanding of mental health

The focus group discussions showed that students attempted to define mental health by associating it with their day-to-day experiences such as dealing with stress.

Researcher: what is your understanding of mental health?

S1. For me, this could be the treatment given to those guys who are mentally unwell or stressed.

S2. I would say it’s a state of mind in which one is settled, not stressed.

S4. Just like my friend has said here, mental health, for me, refers to being mentally ok. Having those positive vibes, thinking good… you know (laughs).

Mental health problems experienced by students

Regarding the issue of whether their friends experience mental health problems or not, the study showed that students could identify some of their friends who suffered in silence. This was expressed by the following excerpts.

Researcher: Do you believe your friends or yourself suffer from mental health problems or stress in your school?

S1. Yes, so many of them. In fact, nearly all of us are stressed in one way or another.

S2. Just as my friend here has suggested, so many of us especially boys are stressed. Like now my close friend has been ailing from gonorrhea but he cannot share for fear of being stigmatized and victimized.

S4. Of course, everyone is stressed, either by family issues or poor academic performance. Then there are issues of boyfriends and pregnancy. So many of these girls are suffering in silence.

Possible causes of mental health problems

There was a lack of consensus over the main cause of stress or mental health problems in school and life generally between the boys and girls who participated in this study. For instance, whereas boys reported that family background and issues emanating from home were major stressors, girls pointed out that peer pressure and boy-girl relationships were the major causes of stress. The following excerpts of the focus group discussions exemplify these assertions. To start with, the girls shared the following:

Researcher: what do you believe is the main cause of stress or mental health problems in school and life generally?

S10: For us girls, I think it is peer pressure.

Researcher: why do you think so?

S3: You see for us we are really influenced by peer pressure. We want to be like others. We want to belong to a certain grouping. We just want to do what our friends do. We want to dress the same way. As you may know, boys care less compared to girls.

Researcher: yes.

S3: A boy can dress shabbily but no one will raise an issue with him. The society judges us girls harshly compared to boys.

Researcher: ok.

S3: Again when it comes to boy–girl relationship. It affects mostly the girls. You see girls tend to love by the heart while boys tend to love by the brain. A boy will tell you I think I love you but a girl will say I love you.

On the other hand, boys complained of stress emanating from their family background. In particular, they shared the following:

Researcher: what do you believe is the main cause of stress or mental health problems in school and life generally?

S5: For us boys, it is stress from home.

Researcher: why do you think so?

S5: You see for us boys once you turn 18 years you are viewed as an adult. You should now start fending for yourself. For example, if I and my sister asks for something, my sister will be given the first priority

Researcher: why should your sister be given first priority and not you?

S3: Sir, for girls the case is usually different. Parents know that if they fail to provide for them then they will easily find someone, possibly a sugar daddy, who will provide. But as you know, a boy finding a sugar mummy is quite difficult.

S1: Even some of us do not live with our parents. We just meet occasionally, especially with our fathers who care very little for us. All they care about is investing in girls for they know girls are a source of dowry.

The foregoing excerpts obtained from the focus group discussions are consistent with the quantitative study (phase 1) which showed that the students experienced stress by different stressors and to different magnitudes. For instance, whereas boys were more stressed by issues emanating from home, girls were stressed because of peer pressure and boy-girl relationships.

Coping strategies for stress

Some students reported that they shared their problems with peers and sought help from parents, teachers, and religious leaders. However, a majority of the students resorted to avoidance as a coping strategy. According to these students, they avoided seeking help because of a range of reasons including stigmatization by others after they revealed their problems to them. For example, one of the students divulged that his friend was suffering in silence after contracting gonorrhea. He further reported that the boy feared that other students would laugh at him and that his girlfriend would desert him.

To other students, the nature of the cause of stress was one that discouraged them from sharing their predicaments. For instance, girls said that it was difficult to disclose to anyone that they were pregnant or that their boyfriend made them heartbroken. This is because boy-girl relationships were prohibited in the school. In the same vein, boys revealed that they suffered in silence battling drug addictions, sexually transmitted diseases, and rejection.

Moreover, some students were discouraged from seeking further help after not receiving it in their previous attempts. For instance, a student disclosed the following:

S3: Sir, we do understand that it is important seek for assistance from our teachers whenever we are stressed but at times those teachers do not help.

Researcher: why don’t they help?

S3: in most cases, they lack the capacity to help.

Researcher: do you have any instance you approached a teacher and informed him or her what was stressing you and you failed to get assistance?

S3: yes, I have several instances.

Researcher: kindly can you share with us one instance?

S3: You see sir, there is this time my parents were not seeing eye to eye. Their relationship had deteriorated to a point mum threw dad out of our rented house.

Researcher: mum did what? But why did she do that?

S3: Dad had just lost his job because of the Covid 19 job losses. As you understand, so many hotels were closed, and my dad used to work for one of the hotels as a chef.

Researcher: sorry for that.

S3: so, I decided to share my predicaments with one of the teachers. The teacher just told me to keeping working hard dad and mum would sort their issues by themselves.

Support systems available to address students’ mental health problems

Finally, the students complained of a lack of well-structured support systems for them to seek help when stressed. They further stated that there was a lack of understanding and patience from their parents. Similarly, teachers were also reported to be hostile as they often stressed adherence to school rules instead of listening to the students. In addition, help from other students was often misleading as most students lacked the knowledge required to offer constructive advice. Moreover, advice from peers was at times not genuine. For example, one girl disclosed that when she sought help from her friend at a time when she was having relationship difficulties with her boyfriend, the friend advised her to stop the relationship only to later learn that the friend had befriended her now ex-boyfriend.

Discussion

Stress levels among secondary school students

The findings of this study revealed that stress levels among students range from moderate to high levels. This is an indication that students in secondary schools in Kenya are pre-disposed to mental health problems. A previous study also reported that university students were moderately and severely stressed (Nathiya et al., 2020, 83). The focus group discussions also concurred that students were stressed. The students shared stories of their stressed friends who were suffering from a range of issues including poor academic performance, high academic expectations from parents and teachers, numerous assignments, feeling homesick, bullying from others, addiction to drug substances, and keeping up with peer pressure. Other stressors that the students mentioned were poverty at home, parental issues (such as divorce, single motherhood, etc.), heartbreak after failed romantic relationships, early pregnancy, and sexually transmitted diseases. There is a possibility that social changes such as disruption in education and the other factors mentioned impacted negatively on students’ sense of wellness and added to their stress. The findings add to existing literature, most of which were from university students, that young people in learning institutions are facing stress stemming from their academic, personal, and social lives, yet they lack the skills to manage the responsibilities (Graves et al., 2021, 2).

Additionally, the quantitative study established that boys suffered from more stress than girls. The findings contrast with past research that showed that women experience more stress than men and that men are less likely to report their emotions compared to women possibly due to their masculine orientation (Graves et al., 2021, 8; Misigo and Ayiro, 2021, 28). The difference in the findings in the current study and previous ones could be due to other threatening factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic that interfered with the day-to-day lives of many (Graves et al., 2021, 8). There is a possibility that the boys were adversely affected by the changes in school closing and reopening during the pandemic that was beyond their previous experiences. The adverse experiences motivated them to talk about what was bothering them. Furthermore, for a long time, girls were viewed as vulnerable in the African setup and were confined as a way of protecting them from possible abuse in the community. Boys were previously less confined. The confinement measures could have been stressful for the boys to the extent that they realized the need to speak out. It is possible that the anonymity assured to them during the data collection process could have also given them the confidence to talk about their experiences freely.

Coping strategies

The findings of this study indicated that there was no significant difference in the use of emotional support and avoidance as coping strategies between boys and girls. This is a departure from previous findings that showed that women sought emotional support to a greater degree than men (Day and Livingstone, 2003, 75; Renk and Creasey, 2003, 159; Abouammoh et al., 2020, 6; Misigo and Ayiro, 2021, 28). The results, however, add to a study (Janney, 2017, 14) that found that gender differences in coping strategies have been decreasing over time. It seems that there are other compelling factors that could be contributing to the low rates of girls seeking emotional support. Such factors could be a lack of open communication between girls and the people who can offer them emotional support. A lack of supportive relationships, closeness, connectedness, and care from others could be the driving force for them to resort to avoidance as a coping strategy. Comparably, a study done in Ghana established that adolescents resorted to isolation, substance use, and spiritual help because the school-based support system was ineffective. Thus, Ghanaian students were not seeking help from counselors because of a lack of trust and confidentiality (Addy et al., 2021, 1). This could be a similar experience for students in Kenyan secondary schools.

In this study, stress was significantly associated with avoidance as a coping strategy. Thus, the more the students perceived themselves to be stressed the more they avoided addressing the problem. This trend is quite worrying because the students knew who to count on or call for help but rarely sought help. For instance, the focus group discussions showed that when the students had a problem they knew suitable strategies such as sharing with their peers and seeking help from parents, teachers, and religious leaders. One of the reasons presented by the students for avoiding seeking help was that their teachers were uncooperative. Other reasons were strict school rules and the lack of well-structured social support systems. The lack of well-structured social support systems could be emanating from the observation that Kenyan schools suffer from the government, teachers, and parents playing blame games (Moywaywa, 2022, 128).

For instance, the government feels that parents are not instilling good character in their children. Similarly, teachers feel that parents have failed in their parenting responsibilities, whereas, on the other hand, parents feel that teachers are not doing their best to enhance moral values in their children. All these suggest that students continue to suffer from mental health-related problems in silence in Kenyan secondary schools which may end up in student indiscipline in schools.

Similarly, fear of rejection by other students of the opposite gender and being taken advantage of (in the case of the girl who lost her boyfriend to her friend) came out strongly in our study. The findings provide pertinent information about the identity formation of students and boy–girl relationships during the adolescent stage. During this stage, adolescents are seeking autonomy from their parents and form identities with their peers (Holden, 2010, 212). Thus, apart from teachers whom they feared, the students did not mention seeking parental support. The findings corroborate the Group Socialization Theory (Harris, 1995, 465) which suggests that at the adolescence stage, peers are the most important environmental influence than parents (Holden, 2010, 212). There is, therefore, a need to empower peers with knowledge and skills so that they can offer emotional and psychological support to fellow peers in schools. This may enhance peer-to-peer support in times of distress.

Mental health literacy levels

The focus group discussions indicated that the students have an idea of what mental health is. Whereas some felt that mental health is help offered to people who are stressed, others felt that it was a state of being at peace with one’s self and being able to think and act soundly. There was a lack of consensus over the main causes of stress or mental health problems among girls and boys. These contradictions could have been a result of the diverse samples employed in this study through the maximum variation technique. For instance, one girl shared that her main source of stress was home as her father had on several occasions tried to marry her off to rich men in the community in exchange for huge dowry payments. A boy reported that the family of his stepfather hated him as he was seen as an intruder. Another student shared that she was worried about her academic performance which kept on dwindling despite her increased effort. From these findings, it can be concluded that students attributed stress and mental health problems to varied factors that include academic performance, family background, issues emanating from the home, peer pressure, and finally boy-girl relationships.

It is also worth noting that the lack of seeking emotional support and resorting to avoidance when stressed could be an indicator of a low mental literacy level. This is based on a previous study (Maria de Carvalho and Vale-Dias, 2021, 281) that found that adaptive forms of coping are related to a positive mental health literacy where adolescents with higher levels of mental health literacy reported less use of denial and avoidance. In this study, there is a possibility that the students knew that mental health issues such as stress needed to be addressed but they could have associated seeking help with people who have severe mental disorders. The students thus believed that their mental health problems will resolve on their own. These findings further validate a report proposal by stakeholders in Kenya on the need for adolescent-friendly spaces and training of youth champions on issues of mental health (Memiah et al., 2022, 2). How the teachers address mental health problems when approached by students also raises questions about the mental health literacy of the teachers in secondary schools in Kenya. The story of a student who sought help from a teacher when stressed but felt unhelped could be an indicator that most teachers could either be ignorant or lack essential skills in mental health. This study contributes to the recommendation that educational strategies, including school curriculums in school settings, should be used in addressing mental health literacy (Kutcher et al., 2016, 161). Given that there are not many pieces of literature on the mental health literacy level of students in Kenya, the findings set a platform for further investigation.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on unheard voices of students in secondary schools in Kenya who are suffering from moderate to severe stress yet prefer avoidance as a coping strategy. It further revealed that unlike before when girls and women sought emotional support more than boys, both boys and girls are now resorting to avoidance as a coping strategy when stressed. Although the students feared rejection from their peers, they preferred sharing their problems with them. Parental participation in addressing mental health issues of their children remains unknown as no child mentioned it. The findings contribute to the Group Socialization Theory that views peers as having more influence on adolescents than their parents would, which was established in this study by students not seeking parental support when in distress. There is a need to empower school students to offer support to their peers in schools. The findings of this study open a window for interrogating this theory further through the lens of mental health among adolescents. It sets the pace of discussing peers, teachers, and parents’ mental literacy levels as well as their roles in supporting students with mental health problems. The findings are also useful to educational planners and policymakers in addressing some of the issues related to offending behavior associated with students’ mental health such as rising cases of criminal behavior in Kenyan schools.

Recommendation

The study recommends the following:

i. A study with a larger sample to enable gauging the magnitude of mental health literacy among secondary school students.

ii. A study assessing teachers’ mental health literacy to ascertain their knowledge, attitude, and ability to detect mental ill health symptoms among students in secondary schools.

iii. Capacity assessment and training of teachers and educational officers in mental health issues so as to come up with policies addressing the rising problem in schools.

iv. Enhancement of literacy levels and the role of parents through the lens of their children’s mental health.

Limitations

The design used cannot infer a causal relationship. Future studies should use a longitudinal design to assess the associations between stress, coping strategies, and mental health literacy.

Data obtained on mental literacy levels cannot be generalized to all students in secondary schools. There is a need to investigate this issue in a larger sample.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

LA and BM designed the study and wrote the introductory part of the manuscript. BM formulated the objectives. LA did the quantitative data collection and analysis. RD did the qualitative data collection and analysis. LA and RD wrote the results section. BM did proofreading and editing. All authors contributed to carrying out the study and writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abouammoh, N., Irfan, F., and AlFaris, E. (2020). Stress coping strategies among medical students and trainees in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 20:124. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02039-y

Addy, N., Agbozo, F., Runge-Ranzinger, S., and Grys, P. (2021). Mental health difficulties, coping mechanisms and support systems among school-going adolescents in Ghana: A mixed-methods study. PLoS One 16:e0250424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250424

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research Methods in Education, 8th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315456539

Creswell, J., and Creswell, D. (2018). Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J., and Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Darmody, M., Smyth, E., and Russell, H. (2020). Impacts of the Covid-19 control measures on the widening Education in-equalities. Redlands, CA: ESRI, doi: 10.26504/sustat94

Day, A., and Livingstone, H. (2003). Gender differences in Perceptions of Stressors and Utilization of Social Support among University Students. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 35, 73–83. doi: 10.1037/h0087190

Dicicco-Bloom, B., and Crabtree, B. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Med. Educ. 40, 314–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

D’Orta, I., Eytan, A., and Saraceno, B. (2022). Improving mental health care in rural Kenya: A qualitative Study conducted in two primary care facilities. Int. J. Mental Health 51, 470–485. doi: 10.1080/00207411.2022.2041265

Ganasen, K., Parker, S., Hugo, C., Stein, D., Emsley, R., and Seedat, S. (2008). Mental health literacy: focus on developing countries. Afr. J. Psychiatry 11, 23–28. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v11i1.30251

Graves, B., Hall, M., Dias-Karch, C., Haischer, M., and Apter, C. (2021). Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS One 16:e0255634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255634

Greenglass, E., Schwarzer, R., and Taubert, S. (1999). The Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI): A multidimensional research instrument. New Delhi: Pharmacy Council of India. doi: 10.1037/t07292-000

Harris, J. (1995). Where is the child’s environment: A group socialization theory of development. Psychol. Rev. 102, 458–489. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.3.458

Holden, W. G. (2010). Parenting: A dynamic perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781452204000

Hu, X., Song, Y., Zhu, R., He, S., Zhou, B., Li, X., et al. (2022). Understanding the impact of emotional support on mental health resilience of the community in the social media in Covid-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 308, 360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.105

Janney, J. (2017). Gender Differences when coping with depression project. Pembroke: University of North Carolina.

Jorm, A. (2000). Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 177, 396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., and Hashish, M. (2016). Mental Health Literacy for students and teachers: A school friendly approach. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804394-3.00008-5

Li, S., Sheng, Y., and Jing, Y. (2022). How Social Support Impact Teachers’ Mental Health Literacy: A Chain Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 13:851332. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.851332

Manzar, M., Salahuddin, M., Peter, S., Alghadir, A., Anwer, S., Bahammam, A., et al. (2019). Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale in Ethiopian university students. BMC Public Health 19:41. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6310-z

Marangu, E., Sands, N., Rolley, J., Ndetei, D., and Mansouri, F. (2014). Mental healthcare in Kenya: exploring optimal conditions for capacity building. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 6, E1–E5. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v6i1.682

Maria de Carvalho, M., and Vale-Dias, M. (2021). Is mental health literacy related to different types of coping? Comparing Adolescents, Young Adults and Adult correlates. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2, 281–290.

Memiah, P., Wagner, F., Kimathi, R., Anyango, N., Kiogora, S., Waruinge, S., et al. (2022). Voices from the Youth in Kenya Addressing Mental Health Gaps and Recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 5366. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095366

Merriam, S., and Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th Edn. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Misigo, L., and Ayiro, L. (2021). Perceived Stress Level and Coping Strategies among emerging Adults during the covid-19 pandemic in Kenya. Kenyan J. Counsell. Psychol. 2, 24–30.

Mitrousi, S., Travlos, A., and Koukia, Z. S. (2013). Theoretical approaches to coping. Int. J. Car. Sci. 6, 131–137.

Modi, J., Dimo, H., and Okemwa, P. (2020). An Investigation into Arson in Secondary Schools in Kenya; a Case of Homa Bay County. Hmlyan. Jr. Edu. Lte. 1, 4–15.

Moywaywa, C. (2022). The Phenomenon of school fires in Kenyan Public secondary schools: Blame Games, scape goats and real culprits. Int. J. Educ. Res. 10:2.

Nathiya, D., Singh, P., Suman, S., Raj, P., and Tomar Balvir, S. (2020). Mental health problems and impact on youths’ minds during the Covid-19 outbreak: Cross-sectional (RED-COVID) Survey. Soc. Health Behav. 3, 83–88.

Owens, M., Townsend, E., Hall, E., Bhatia, T., Fitzgibbon, R., and Miller-Lakin, F. (2022). Mental Health and Wellbeing in Young People in the UK during Lockdown (COVID-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1132. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031132

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 4th Edn. London: Sage Publication.

Radicke, A., Sell, M., Adema, B., Daubmann, A., Kilian, R., Busmann, M., et al. (2021). Risk and protective factors associated with health-related quality of life of parents with mental illness. Front. Psychiatry 12:779391. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.779391

Renk, K., and Creasey, G. (2003). The relationship of gender, gender identity, and coping strategies in late adolescents. J. Adolesc. 26, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00135-5

Revital, S., and Haviv, N. (2022). Juvenile delinquency and COVID-19: the effect of social distancing restrictions on juvenile crime rates in Israel. J. Exp. Criminol. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s11292-022-09509-x

Roohi, S., Javad, S., Mahmooddzadeh, H., and Morovati, Z. (2020). Relationship of social support and coping stategies with post-traumatic growth and functional disability among patients with cancer: meditating role of health literacy. Iran Red. Crescent. Med. J. 22, 1–11. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.98347

Roy, K., Kamath, V., and Kamath, A. (2015). Determinants of adolescents stress: A narrative review. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2, 48–56. doi: 10.4103/2395-2555.170719

Schneider, B. H. (2009). An observational study of the interactions of socially withdrawn/anxious early adolescents and their friends. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 50, 799–806.

Tahlia, L. B., Daniel, L. S., and Frederick, L. C. (2018). Mental health literacy and attitudes about mental disorders among younger and older adults: A preliminary study. Open J. Geriat. 1, 1–6.

Taylor, S. J., Bogan, R., and DeVault, M. L. (2016). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource, 4th Edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Tuasig, M., Gotlib, I., and Avison, W. (1995). Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future. Contemp. Sociol. 24:827.

Venkataraman, S., Patil, R., and Balasundaram, S. (2019). Why mental health literacy still matters: a review. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 6:27239.

World Health Organization [WHO] (2001). The World Health Report 2001: Mental Disorders affect one in four people. Geneva: WHO.

Yusuf, M. (2021). Dozens of Kenyan Schools Closed due to students Arson. Washington, DC: Voice of America.

Appendix

Appendix A: Focus group discussion guide

1. What is your understanding of mental health?

2. Do you believe your friends or yourself suffer from mental health or stress in your school?

3. What do you believe is the main cause of stress or mental health problems in school and life in general?

4. Between boys and girls in your school, who suffer more from mental health problems? Why?

5. Whom do you go to for support when you are stressed, do you open up to others or confide to them when you are stressed? If yes, why? If not, why?

6. Generally, why would you avoid seeking support when you are feeling stressed?

7. In your opinion why do many students prefer to put aside the issue troubling them instead of looking for a solution or help?

8. What do you think students need to know about mental health services?

Keywords: mental, literacy, stress, coping, strategies, health

Citation: Ayiro L, Misigo BL and Dingili R (2023) Stress levels, coping strategies, and mental health literacy among secondary school students in Kenya. Front. Educ. 8:1099020. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1099020

Received: 15 November 2022; Accepted: 14 February 2023;

Published: 16 March 2023.

Edited by:

Tholene Sodi, University of Limpopo, South AfricaReviewed by:

Sumeshni Govender, University of Zululand, South AfricaJulia Mutambara, Midlands State University, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2023 Ayiro, Misigo and Dingili. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lilian Ayiro, YXlpbGlsaWFuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Lilian Ayiro

Lilian Ayiro Bernard Lushya Misigo1

Bernard Lushya Misigo1