95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 07 June 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1091426

This article is part of the Research Topic Well-Being and Education: Current Indications and Emerging Perspectives View all 17 articles

Simone Sayuri Kushida*

Simone Sayuri Kushida* Eduardo Juan Troster

Eduardo Juan TrosterIntroduction: Worldwide burnout prevalence among medical students is high. It has a negative impact on students’ personal and professional lives as well as on their psychosocial wellbeing and academic performance. It can result in physicians with emotional distancing and indifference to work, and it compromises the quality of healthcare offered to society. This study evaluates burnout in medical students selected by mini-multiple interviews (MMIs) who were being taught by the team-based learning (TBL) method. MMIs are often used to select students with soft skills for medicine, and TBL is related to greater academic achievement, which would allow students to have greater resilience to stress. Information on burnout occurrence is lacking for this type of student.

Methods: Students (N = 143) attending the first three semesters at a private medical school were evaluated. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory—Student Version (CBI-SV) questionnaire was applied on three occasions (applications = Apps one, two, and three) in each semester. Scores ≥ 50 were considered to indicate burnout. Data were analyzed by statistics programs.

Results: Personal-related and study-related burnout frequencies for 1st semester students were, respectively, 24.4 and 22% in App one and rose to 51 and 48.5% at the semester’s end. Second- and third-semester students’ frequencies reached 80.4 and 78.8%, respectively. Around 40% of 1st semester students having burnout at App one maintained the burnout score. Peer- and teacher-related burnout frequencies are low (4.9 and 2.4%) at the 1st semester App one and rose to the highest (24–30%) by the end of the 2nd semester. Woman students had significantly higher burnout frequencies in the personal- (p < 0.001) and study-related burnout subscales (p = 0.003). Students living with friends had lower study-related burnout scores than those living with family or alone (p = 0.024). There were no significant correlations between the burnout scores and tuition funding (partial or total) or having or not having religious faith.

Discussion: The prevalence of personal- and study-related burnout among medical students of the Faculdade Israelita de Ciências da Saúde Albert Einstein (FICSAE), perceived via mini-multiple interviews (MMI)—selected and team-based learning (TBL)—taught, was similar to those internationally reported. The college semester and the gender of woman were associated with worse burnout levels. Additional studies are needed to support more effective actions to reduce the impact of stress on students.

Burnout is a psychological syndrome induced by chronic stressors in a work environment characterized by a triad: emotional exhaustion, cynical attitudes and feelings, and low sense of personal accomplishment (Maslach and Jackson, 1981; Lee and Ashforth, 1990).

There is great concern about the mental health of medical students. Medical students have to cope with long study and working hours. Many first- and second-year students had not realized the demanding nature of medical training.

Systematic analysis studies have reported a burnout prevalence of 44.2% (Frajerman et al., 2019) or between 45 and 71% (Ishak et al., 2013) in medical students. More than 50% of first-year students at a British school reported high levels of emotional exhaustion (Guthrie et al., 1998; Cecil et al., 2014). In Brazil, a review and meta-analysis on medical students’ mental health found values of 13.1% for burnout prevalence, 49.9% for stress, and 30.6% for depression (Pacheco et al., 2017).

An important matter to consider is what constitutes burnout. A systematic review of the literature found at least 142 burnout definitions (Rotenstein et al., 2018). Many authors have questioned whether the symptoms described for burnout diagnosis are compatible with those of depression. Hintsa et al. (2016) analyzed chronic stress effects, showing that burnout results lost statistical significance when controlled for depression. It is believed that work-related stress is the triggering factor for burnout, but according to Bianchi et al. (2015) stress sources present in social life including work would also be factors underlying burnout and depressive disorders.

Admission to medical schools in Brazil occurs after the completion of 3 years of high school, when the students generally are 17–20 years old. Medical schools in Brazil, public or private, select their students by written examinations based on the high school curriculum. Students with the highest marks are selected for admittance. There are no interviews or any other form of appraisal of the candidate’s personality. The teaching methods are traditional with few adaptations.

The medical school of the Faculdade Israelita de Ciências da Saúde Albert Einstein (FICSAE) is located in São Paulo and, from its beginning, innovated the admission process and the teaching methodology of its medical course. Candidates first undergo a multiple-choice test on high school subjects. In a second phase, they attend mini-multiple interviews (MMI) to evaluate personal competences for the practice of medicine such as empathy, ethics, teamwork, and communication (Costa et al., 2013). The final selection takes into consideration their performance in both phases.

The methodology of the FICSAE medical course is team-based learning (TBL), which is an inter-active learning method. It is grounded in the acquisition of knowledge by discussions among students organized in small groups (Burgess et al., 2017). The students are required to study a subject on their own and are evaluated before and after discussions with colleagues and, in sequence, with a teacher. Active learning requires discipline from the student in order to cope with the required study load throughout the semester (Carrasco et al., 2021). Weekly tests, conceived to stimulate constant learning, can be a source of stress. However, because of the method’s focus on group learning, TBL offers students the opportunity to develop social skills such as mutual help, respect for diversity of opinions, and self-esteem and self-control (Carrasco et al., 2021).

Methods such as MMI and TBL aim to select and train students in medical science and in the socio-emotional abilities considered as important skills for a good doctor (Englander et al., 2013). Selection by MMI is related to greater academic achievement and is possibly a predictor of performance after graduation (Scott and Markert, 1994; Reiter et al., 2007; Eva et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2016; Yusoff, 2019).

It is important that MMI-selected medical students adapt better to the demands of training. Similarly, it would be expected that TBL-taught students, because of the mutual collaboration inherent to the method, would be more resilient to the stress of medical training programs. Nevertheless, a search of the literature found no published studies on psychological aspects such as satisfaction with academic life, general wellbeing, or the occurrence of burnout in medical students selected by MMI and/or taught by TBL.

The hypothesis tested in the present study is whether the prevalence of burnout syndrome would be lower in FICSAE medical students because they were selected by MMI and taught by TBL, in comparison to medical students taught by traditional teaching methods, who are selected solely by their knowledge of high school subjects. Theoretically, MMI selection plus the TBL teaching method would impart more resilience to stress. This study investigated the prevalence of burnout syndrome in first-year and second-year FICSAE students in order to identify correlated socio-demographic variables. The findings of the present study are compared to the existing research on the prevalence of burnout syndrome among medical students.

First, second and third-semester students attending FICSAE in 2017 were eligible to participate in the study (N = 150). The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Hospital Albert Einstein, to which FICSAE belongs, under number 2.233.372. Voluntary participants signed an informed consent form before receiving the study questionnaires. All measures were taken to guarantee the confidentiality of the data and to prevent any social exposure. The main researcher was the only person to access the questionnaires, and there was no nominal disclosure of participants.

This study was a prospective observational research. The questionnaires were implemented on three occasions in the semester at intervals of approximately 7 weeks. Application took place in FICSAE classrooms. Each of the three occasions avoided the period of final exams or the resumption of classes after vacation. The two questionnaires were:

(1) A socio-demographic questionnaire to characterize the included population according to their age, gender, marital status, medical school semester, existence of housemates, tuition funding, and religion.

(2) Copenhagen Burnout Inventory—Student Version (CBI-SV): a questionnaire created to assess several aspects of the burnout syndrome in students. The CBI-SV questionnaire comprises questions related to four aspects (called subscales) of burnout: personal burnout (six items), study-related burnout (seven items), peer-related burnout (six items), and teacher-related burnout (six items).

All items are rated on a scale of 1–5 points: 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = always. The subscale scores were validated for publishing in Brazilian Portuguese language (Reiter et al., 2007). The answers to each item were assigned values: never = 0, rarely = 25, sometimes = 50, often = 75, and always = 100. Item ten is scored in reverse order (Campos et al., 2013).

The final score of each subscale was the average mean of its items’ scores, varying from 0 to 100. Values equal to or greater than 50 points were considered as the burnout level, and these four subscales were analyzed separately (Borritz and Kristensen, 2004; Campos et al., 2013).

The application, computing, and analysis of the data were performed according to published guidelines (Borritz and Kristensen, 2004). In order to calculate a score, a minimum number of items had to have been answered: at least three items in the subscales for personal, peer-related, and teacher-related burnout and at least four items in the study-related burnout subscale (Borritz and Kristensen, 2004).

The analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows program, version 24.0, and p-values were adjusted by the computer software R, version 3.4.1, and a 5% significance level was considered. To identify further associations between semester progression and the socio-economic data, estimation equations with binomial distribution considered the inter-dependence of evaluation for each student. The adjusted mean values and 95% CI were compared with p-values corrected by the sequential Bonferroni method.

A total of 97% of all the invited students participated in the study, comprising 143 medical students from the first, second, and third semesters. For the full sample, 60.8% participated in all three questionnaire applications, 25.9% participated twice, and 13.3% participated only once. The sample parameters are available as a Supplementary Table 1.

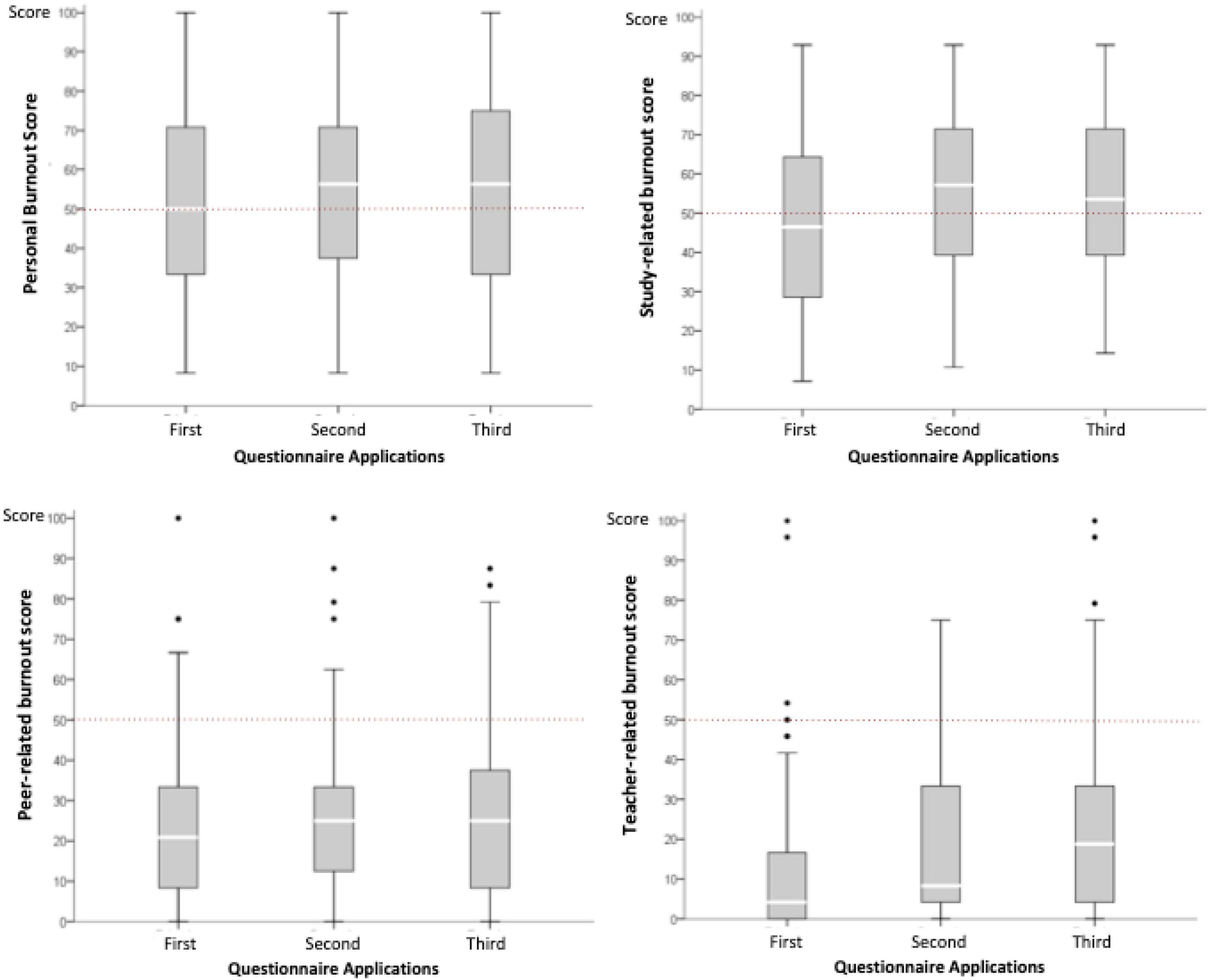

As shown in Figure 1, mean scores of ≥50 were most evident in the questionnaires that explored personal- and study-related subscales. In contrast, peer-related and teacher-related mean scores were well below the 50 points score, although a significant number of students had burnout scores of ≥50 in these subscales.

Figure 1. Distribution of scores obtained in Copenhagen Burnout Inventory—Student Version (CBI-SV) subscale questionnaires applied to Faculdade Israelita de Ciências da Saúde Albert Einstein (FICSAE) students at the beginning, middle, and end of the first three semesters of medical school. The subscale types of CBI-SV questionnaires applied were personal-related, study-related, peer-related, and teacher–related. The white line in the boxplots is the median, and the below and above limits represent the first (25%) and third (75%) quartiles, respectively. Maximum and minimum values are indicated by whiskers, and outliers are shown as asterisks. The transversal line marks the score of 50, which is the threshold considered as burnout in CBI-SV questionnaires. The number of students answering the questionnaires varied from 106 to 143.

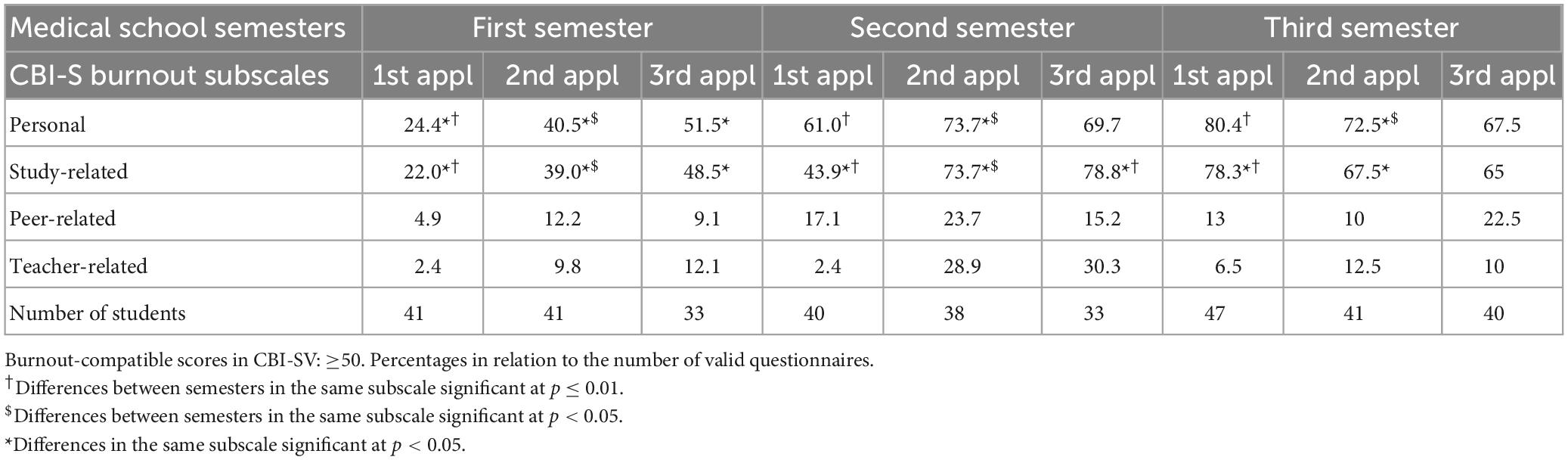

Table 1 shows the percentage of students with burnout scores tested for the various subscales at different time points during the first three semesters of medical school. In the first semester of the medical course, the personal- and study-related burnout frequencies showed a marked increase from the first application to the second, and they roughly doubled in value by the third application (p < 0.05), in which nearly 50% of the students had burnout-compatible scores. It is of note that the questionnaires were applied with intervals of only 7 weeks. These values remained high at the first implementation for the second-semester students, and they increased as the semester progressed (p < 0.05 once compared first and second applications and first and third). The highest frequencies of personal- or study-related burnout were seen at the beginning (first application) of the third semester, tending to a small reduction and stabilization as the semester progressed.

Table 1. Percentage of Faculdade Israelita de Ciências da Saúde Albert Einstein (FICSAE) students with burnout-compatible scores in the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory—Student Version questionnaires applied at the beginning, middle, and end of the first three semesters of medical school.

The percentage of medical students with peer-related burnout scores was small at the beginning of the first semester (approximately 5%), but it doubled over the semester. The highest values were observed at the middle of the second semester and at the end of the third semester. Teacher-related burnout frequency was 2.4% at the start of the first and second semesters, increasing by the second and third questionnaire applications; the values were highest (30.3%) in the middle (second application) of the second semester. In the third semester, the frequencies markedly decreased to values between 6.5 and 12.5%.

This study allowed other analyses. Approximately 22% of the students, who had low scores at the first application of the personal- and study-related subscales, maintained their low scores throughout the two subsequent applications. Conversely, 38–41% who had scores that were ≥50 maintained their scores (data not shown).

In relation to gender, woman students presented higher frequencies of burnout than colleagues who were men in the personal-related burnout (p < 0.001) and study-related burnout (p = 0.003) subscales. Students living with friends had lower study-related burnout scores than those living with family or alone (p = 0.024). There were no significant correlations between the burnout scores and tuition funding (partial or total) or having or not having religious faith.

We found that the median prevalence of personal- and study-related burnout scores (≥50) in FICSAE students selected by MMI and taught by the TBL methodology was high and varied from 24.4%, at the start of medical school training to 80.4% by the third semester of medical school. These frequencies were closer to the 45–71% burnout levels reported in published systematic review studies of medical schools outside Brazil (Ishak et al., 2013).

However, it is difficult to compare data obtained by different methods or inventories. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) was used to evaluate emotional exhaustion among British and American medical students, showing a prevalence of 54.8 and 35–45%, respectively (Cecil et al., 2014; Dyrbye and Shanafelt, 2016). It should be mentioned that these results are not directly comparable to this study described herein, which utilized the CBI-SV, although some items are similar to the MBI emotional exhaustion scale (Maroco and Campos, 2012).

Studies conducted in Brazilian schools, mostly using MBI, reported frequencies of 13.1% (Pacheco et al., 2017) and 12% (Barbosa et al., 2018) for medical students who underwent traditional admission exams to medical schools and who had been taught by conventional teaching methods, respectively. Moreover, regionalism could possibly explain the variation of Brazilian results and the international prevalence of burnout. All Brazilian studies were carried out in the Northeast Region, while the main and most competitive medical schools are located in the Southeast Region, where the school environment becomes more competitive and stressful. At the University of São Paulo, the most competitive Brazilian medical school, a longitudinal study by Millan and Arruda (2008) showed that only 27% of students passed their first attempt to enter college, whereas 41% made two attempts, and 32% made three or more attempts.

Taken together, the results from the present study indicate that personal- and study-related burnout are critical factors in the academic life of FICSAE students. On the other hand, the relationship with colleagues or teachers was not a stressful factor for most students, as the frequencies observed for these subscales were much lower than those for personal- and study-related burnout. However, as expected, in each semester as time passed, gradual increases were observed in the number of students manifesting peer- and teacher-related burnout. The higher frequencies of teacher-related burnout in the second semester possibly reflect difficulties with a particular teacher or subject, considering the sharp reduction during third semester. In general, the low frequencies of students with peer- or teacher-related burnouts probably reflect the TBL method, which encourages cooperation among students and promotes a closer relationship with teachers. These results are novel, as there are no published reports of the effects of interpersonal relations for TBL-taught students.

The high personal- and study-burnout frequencies at the beginning of the semester affecting 22–24% of the students were not expected. Medical students present a demanding trait for high personal performance (Millan and Arruda, 2008), which, allied to highly competitive admission tests, (Pacheco et al., 2017) might have contributed to those high frequencies. Significantly, around 40% of students maintained the burnout scores throughout the first semester, signaling that this group of students requires special attention.

A multi-center study by Dyrbye et al. (2009) indicates that dissatisfaction with the academic environment and the level of perceived support is more closely associated with first-year and second-year burnout. As students advance, other factors, many related to clinical practice, become important in burnout development. Therefore, effective strategies to optimize the learning environment should be developed for different phases of the medical training curriculum (Dyrbye et al., 2009).

In the present study, women presented higher scores for personal- and study-related burnout than men. Other authors found no difference in general burnout levels between genders, although men present higher depersonalization scores and women higher emotional exhaustion scores (Mazurkiewicz et al., 2012; Cecil et al., 2014; Dyrbye et al., 2014). While religion and receiving or not receiving a scholarship did not affect burnout, rather the factor of living with friends is correlated with lower study-related burnout in comparison to students living with family or alone. Perhaps, individuals who are going through the same moment of crisis feel less fragile and more secure (Saito et al., 2014).

Another question to be raised is to what extent burnout questionnaires yield evidence of real burnout. The most widely used is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which was conceived to evaluate three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment at work (Maslach and Jackson, 1981). We deemed that MBI-HSS (Human Services Survey) would not be an adequate method to evaluate first- and second-year medical students because they have only minimal interaction with patients, and for them the most prevalent factor is emotional exhaustion (Mazurkiewicz et al., 2012). Therefore, the present study utilized the CBI-Student Version, a scale that has been validated for the Brazilian Portuguese language (Campos et al., 2013).

As for the limitations of the present study, the study design was cross-sectional and, thus, limited to the first three semesters, and anxiety and depression were not investigated, which can underlie burnout.

In conclusion, the prevalence of personal- and study-related burnout in FICSAE medical students reached significant values, similar to those reported internationally, despite having been selected by MMI and taught by TBL methods. Team-based learning stimulates participation in classes and interest in learning among the so-called Generation Z (Toledo et al., 2012). However, persistent stress can seriously affect the students’ psychological wellbeing. Medical schools have the responsibility to support the students to reduce the impact of stress and to make institutional efforts to facilitate academic achievement (Dyrbye et al., 2006; West et al., 2016).

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research and Ethics Committee of Hospital Albert Einstein. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SK and ET contributed to the conception and design of the study. SK organized the database, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the first version of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the review of the manuscript, read, and approved the submitted version.

SK acknowledges the fellowship support from the Faculdade Israelita de Ciências da Saúde Albert Einstein to perform this study as a Master of Science requirement and thanks Ises de Almeida Abrahamsohn for the help in writing the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1091426/full#supplementary-material

Barbosa, M., Ferreira, B., Vargas, T., Silva, G., Nardi, A., Machado, S., et al. (2018). Burnout prevalence and associated factors among Brazilian medical students. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 14, 188–195. doi: 10.2174/1745017901814010188

Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I., and Laurent, E. (2015). Is it time to consider the “burnout syndrome”. a distinct illness? Front. Public Health 8:158. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00158

Borritz, M., and Kristensen, T. (2004). Normative Data from a Representative Danish Population on Personal Burnout and Results from PUMA study on Personal Burnout, Work Burnout, and Client Burnout, 1st Edn. Copenhagen: National Institute of Occupational Health.

Burgess, A., Bleasel, J., Haq, I., Roberts, C., Garsia, R., Robertson, T., et al. (2017). Team-based learning (TBL) in the medical curriculum: better than PBL? BMC Med. Educ. 17:243. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1068-z

Campos, J., Carlotto, M., and Maroco, J. (2013). Copenhagen burnout inventory - student version: adaptation and transcultural validation for Portugal and Brazil. Psicol. Reflex Crit. 26, 87–97. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722013000100010

Carrasco, G., Behling, K., and Lopez, O. (2021). Weekly team-based learning scores and participation are better predictors of successful course performance than case-based learning performance: role of assessment incentive structure. BMC Med Educ. 21:521. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02948-6

Cecil, J., McHale, C., Hart, J., and Laidlaw, A. (2014). Behaviour and burnout in medical students. Med. Educ. 19:25209. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.25209

Costa, M., Pêgo, J., Bessa, J., and Cerqueira, J. (2013). “Uma metodologia de mini-entrevistas para a seleção de estudantes de acordo com as suas competências não cognitivas,” in Atas do XII Congresso Internacional Galego-Português de Psicopedagogia, (Braga: Universidade do Minho).

Dyrbye, L., and Shanafelt, T. (2016). A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med. Educ. 50, 132–149. doi: 10.1111/medu.12927

Dyrbye, L., Thomas, M., Harper, W., Massie, F. Jr., Power, D., Eacker, A., et al. (2009). The learning environment and medical student burnout: a multicentre study. Med. Educ. 43, 274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03282.x

Dyrbye, L., Thomas, M., and Shanafelt, T. (2006). Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad. Med. 81, 354–373. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009

Dyrbye, L., West, C., Satele, D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Sloan, J., et al. (2014). Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad. Med. 89, 443–451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

Englander, R., Cameron, T., Ballard, A., Dodge, J., Bull, J., and Aschenbrener, C. (2013). Toward a common taxonomy of competency domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad. Med. 88, 1088–1094. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b

Eva, K., Reiter, H., Rosenfeld, J., Trinh, K., Wood, T., and Norman, G. (2012). Association between a medical school admission process using the multiple mini-interview and national licensing examination scores. JAMA 308, 2233–2240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.36914

Frajerman, A., Morvan, Y., Krebs, M., Gorwood, P., and Chaumette, B. (2019). Burnout in medical students before residency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 55, 36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.08.006

Guthrie, E., Black, D., Bagalkote, H., Shaw, C., Campbell, M., and Creed, F. (1998). Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: a five-year prospective longitudinal study. J. R. Soc. Med. 91, 237–243. doi: 10.1177/014107689809100502

Hintsa, T., Elovainio, M., Jokela, M., Ahola, K., Virtanen, M., and Pirkola, S. (2016). Is there an independent association between burnout and increased allostatic load? testing the contribution of psychological distress and depression. J. Health Psychol. 21, 1576–1586. doi: 10.1177/1359105314559619

Ishak, W., Nikravesh, R., Lederer, S., Perry, R., Ogunyemi, D., and Bernstein, C. (2013). Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin. Teach. 10, 242–245. doi: 10.1111/tct.12014

Lee, H., Park, S., Park, S., Park, W., Ryu, S., Yang, J., et al. (2016). Multiple mini-interviews as a predictor of academic achievements during the first 2 years of medical school. BMC Res. Notes 9:93. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1866-0

Lee, R., and Ashforth, B. (1990). On the meaning of Maslach’s three dimensions of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 75, 743–747. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.75.6.743

Maroco, J., and Campos, J. (2012). Defining the student burnout construct: a structural analysis from three burnout inventories. Psychol. Rep. 111, 814–830. doi: 10.2466/14.10.20.PR0.111.6.814-830

Maslach, C., and Jackson, S. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Occup. Behav. 2, 99–113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205

Mazurkiewicz, R., Korenstein, D., Fallar, R., and Ripp, J. (2012). The prevalence and correlations of medical student burnout in the pre-clinical years: a cross-sectional study. Psychol. Health Med. 17, 188–195. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.597770

Millan, L., and Arruda, P. (2008). Assistência psicológica ao estudante de medicina: 21 anos de experiência. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 54, 90–94. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302008000100027

Pacheco, J., Giacomin, H., Tam, W., Ribeiro, T., Arab, C., Bezerra, I., et al. (2017). Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. J. Psychiatry 39, 369–378. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2223

Reiter, H., Eva, K., Rosenfeld, J., and Norman, G. (2007). Multiple mini-interviews predict clerkship and licensing examination performance. Med. Educ. 41, 378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02709.x

Rotenstein, L., Torre, M., Ramos, M., Rosales, R., Guille, C., Sen, S., et al. (2018). Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA 320, 1131–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777

Saito, M., Silva, L., and Leal, M. (2014). Adolescência: Prevenção e Risco, 3th Edn. São Paulo: Atheneu.

Scott, J., and Markert, R. (1994). Relationship between critical thinking skills and success in preclinical courses. Acad. Med. 69, 920–924. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00015

Toledo, P., Albuquerque, R., and Magalhães, A. (2012). “O comportamento da geração Z e a influência nas atitudes dos professores,” in Proceedings of the IX Simpósio de Excelência em Gestão e Tecnologia, (Rezende: Associação Educacional Dom Bosco).

West, C., Dyrbye, L., Erwin, P., and Shanafelt, T. (2016). Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 388, 2272–2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X

Keywords: burnout–professional, psychology, medical school academic performance, medical student and residency education, stress

Citation: Kushida SS and Troster EJ (2023) Burnout prevalence in medical students attending a team-based learning school. Front. Educ. 8:1091426. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1091426

Received: 07 November 2022; Accepted: 19 May 2023;

Published: 07 June 2023.

Edited by:

Eirini Karakasidou, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, GreeceReviewed by:

Joaquin Garcia-Estañ, University of Murcia, SpainCopyright © 2023 Kushida and Troster. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simone Sayuri Kushida, c2F5dXJpX2t1c2hpZGFAeWFob28uY29tLmJy, ZWR1YXJkby50cm9zdGVyQGVpbnN0ZWluLmNvbS5icg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.