- 1VSO Sierra Leone, Freetown, Sierra Leone

- 2Open Development & Education, Freetown, Sierra Leone

- 3School of Psychology, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Background: Like many other countries, Sierra Leone faces significant challenges with primary education resulting in many children leaving primary school without acquiring basic foundational skills. To address these challenges, an educational technology (EdTech) intervention was implemented in 20 primary schools located in two marginalized districts in Sierra Leone. While this EdTech intervention has been shown to raise learning outcomes, little is known about the impacts on the broader education ecosystem. This paper investigates how this EdTech intervention might address some the challenges faced with primary education in Sierra Leone, by examining policy, teacher, and community perspectives.

Method: A mixed methods approach was employed which included a policy mapping exercise, a survey of teachers training needs in supporting the development of foundational skills with grade 1 learners, an interview with teachers after they had delivered the EdTech intervention to garner their perceptions and experiences of using the technology in their class, and focus groups with teachers and other community members to gain insights into how the EdTech intervention had been received.

Results: Findings from the policy mapping exercise and quantitative data from the survey of teacher training needs were triangulated with qualitative data from the interviews and focus groups. Four key themes emerged relating to the effective and sustained use of this EdTech intervention to support the acquisition of foundational skills by primary school children in Sierra Leone: (1) the need for continued teacher professional development, (2) the use of English as the language of instruction, (3) access to the technology by children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), and (4) the importance of active community engagement in supporting the intervention.

Discussion: Collectively, results indicated that the EdTech intervention employed in this study aligned well to the education policy in Sierra Leone. Enhanced teacher training is needed, especially in using English as the language of instruction, and continued community engagement is essential for scaling the intervention effectively and ensuring that all children, including those with SEND, access the technology at primary school. These results have implications for other EdTech intervention deployed in resource-poor settings to enhance learning of foundational skills.

Introduction

Significant challenges with the provision of quality primary education prevail globally. This results in more than 617 million children and adolescents worldwide having impoverished literacy and numeracy skills, yet these foundational skills are needed to live a healthy and productive life and contribute toward economic growth (UNESCO, 2017). This global learning crisis is particularly evident in Sub-Saharan African countries where minimal proficiency levels are not being met by 88% of children and adolescents in reading and 84% in mathematics. To address this global learning crisis, all member states of the United Nations agreed to work toward the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal for Quality Education (SDG4), which aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Like many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Sierra Leone faces considerable challenges with primary education (UNESCO, 2017; Annual Schools Census Report and Statistical Abstract, 2019). Accordingly, in 2018 the Government of Sierra Leone launched its Free Quality School Education Program (FQSE), which aims to “increase nationwide access to quality pre-primary, primary and secondary school, as well as school-level technical and vocational education and training” (FQSE, MBSSE, 20181). Even though enrolment rates rose to 139% in 2019, on average, children will have received just 4.5 learning adjusted years by the time they turn 18 (World Bank, 2018; UIS, 2019). High levels of unqualified teachers, particularly at the primary level (Mackintosh et al., 2020), and lack of resources hinders the provision of high-quality primary education and perpetuates the learning crisis that results in deep inequalities in foundational learning, with many children leaving primary school without acquiring critical skills in reading, writing and maths: 64% of grade 4 children cannot answer a single comprehension question on a basic text (Sengeh and Winthrop, 2022). Low levels of foundational skills impact quality of life and wellbeing, active participation in society, and increase the risk of pernicious social issues such as forced marriage, female genital circumcision, and child labor (International Centre for Research on Women, 2016). Pitchford (2023) argued that radical solutions are required that will eliminate existing barriers to quality education for all children, anywhere in the world.

One potential solution that has been introduced into primary schools in resource-poor settings over the past decade to address the crisis in foundational learning is personalized digital educational technology (EdTech). These EdTech interventions personalize and adapt instructional content to the needs of individual learners. While literature on the use of EdTech in supporting quality education is increasing, there is a paucity of rigorous evidence demonstrating efficacy (Law et al., 2008; Haßler et al., 2016; Major et al., 2021). However, a recent meta-analysis that examined the effectiveness of technology-supported personalized learning for school-aged children in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) reported statistically significant positive effects on learning outcomes, for both literacy and mathematics (Major et al., 2021). This study included 16 randomized controlled trials with 53,029 learners aged 6–15 years, conducted in five countries, that were published between 2007 and 2020. Major et al. (2021) concluded that technology to support personalized learning in LMICs could play an important role in ensuring more inclusive and equitable access to education and called for the appropriateness of teachers integrating personalized approaches in their practice to be explored.

There is a growing evidence base for the efficacy of a personalized EdTech intervention designed to support the acquisition of basic literacy and numeracy skills that has been deployed in several countries in the Global South, including but not exclusive to, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Cambodia, Brazil, India, and Jamaica, as well as high-income countries, such as Canada and the UK.2. This EdTech intervention—onecourse—has been designed and developed by onebillion©, joint winners of the Global Learning XPRIZE and several other education awards,3 and is currently being scaled nationally in Malawi.4 This personalized EdTech intervention covers basic literacy and mathematics instruction in over 4,000 learning units, delivered through hand-held tablets (see Pitchford, 2023, for an overview). It features a virtual teacher who describes ‘how to’ by demonstrating tasks, then the child is required to interact with the software to practice the task, during which they receive feedback on their interactions, before being tested on the skill being learnt.

Studies evaluating the efficacy of onecourse on learning outcomes have shown significant improvements in early grade literacy and mathematics in Malawi, for mainstream children and children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND), as well as the UK (Pitchford, 2015; Hubber et al., 2016; Outhwaite et al., 2017, 2018; Pitchford et al., 2018, 2019; Gulliford et al., 2021; Bardack et al., 2023). Results of these evaluation studies demonstrate consistent and reliable learning gains can be achieved with this education technology regardless of context. In general, this amounts to a 3+ month advantage for children learning basic numeracy and a 4+ month advantage for children learning basic literacy with the onebillion software compared to standard classroom instruction (Education Endowment Foundation, 2019; Pitchford et al., 2019; Imagine Worldwide, 2020; Outhwaite et al., 2020). This EdTech intervention has also been shown to be effective at raising basic numeracy skills in bilingual children in Brazil, when delivered in either Brazilian Portuguese or English (Outhwaite et al., 2020), and for bilingual children in South Africa (Pitchford et al., 2021), and for children in the UK with English as an Additional Language (Outhwaite et al., 2017). Moreover, girls and boys respond equally well to this intervention which can mitigate gender disparities associated with traditional teaching methods, especially when introduced in the first year of formal schooling (Pitchford et al., 2019). The intervention has also been shown to be suitable for children of different socio-economic backgrounds (Outhwaite et al., 2017) and to improve attentional capacity of learners through interacting with the software, resulting in secondary learning gains (Pitchford and Outhwaite, 2019). The importance of implementation within classrooms on learning gains with this technology has been highlighted (Outhwaite et al., 2019), demonstrating the need for teachers to have sufficient capacity and capability to implement the intervention successfully (Pitchford, 2023). For it to be sustainable and scaled at a national level, it is also important to demonstrate how the technology aligns with current education policy in the country where it is being deployed and that it is culturally sensitive and acceptable to the communities in which it is being introduced (Pitchford, 2023).

Although it has been shown that EdTech can be beneficial in raising learning outcomes in core foundational skills in LMICs (Major et al., 2021), it can also create additional barriers which increase inequalities (Barry, 2022). The digital divide between learners in the Global North and the Global South can be increased through asynchronous development of EdTech, differential provision of EdTech facilities, and inconsistency in inclusive learning environments (Tsegay, 2016). The importance of an equitable approach to EdTech (i.e., an approach that ensures each child receives the support they need to develop their full academic potential5), is emphasized by Zubairi et al. (2021) who argued that unless stakeholders are committed to delivering EdTech with equity, the default position of EdTech will be to exacerbate rather than reduce existing inequalities. It is important, therefore, when introducing EdTech to communities, to carefully consider the local context and evaluate positive and negative consequences on teachers and local communities, as well as determining the learning outcomes of children. The quality, relevance, and consequences of introducing EdTech into local communities should be examined, to ensure inclusivity, especially for marginalized groups, such as children living in poverty, children living in rural locations, and children with SEND, and to enable sustainable development.

A recent systematic review focused on how EdTech might support learners with SEND in LMICs (Lynch et al., 2022). Lynch et al. (2022) highlighted that most studies focused on access to EdTech and less on promoting learner engagement with and empowerment through EdTech. However, Coflan and Kaye (2020) argued that EdTech can play a role in advancing the Universal Design for Learning framework for children with SEND if EdTech is part of a holistic (i.e., comprehensive and interconnected) strategy for inclusion. Barry (2022) argued that EdTech should be introduced “in a thoughtful, learner-focused and age-appropriate way to improve the availability, accessibility, acceptability and adaptability of education for all” (page 18) to align with SDG4. Furthermore, rigorous research focused on understanding how EdTech interventions work in specific contexts, especially how use of technology aligns with government priorities and leads to the strengthening of national education systems, is needed (Hollow and Jefferies, 2022).

With these concerns in mind, the aim of this study was to examine the broader impacts of the introduction of the onecourse EdTech intervention within the primary education ecosystem in Sierra Leone, by considering policy, teacher, and community perspectives, to engender insights to be gained for the deployment and scaling of personalized digital learning interventions designed for raising foundational learning in other LMIC contexts. Accordingly, this study examined (i) how the onecourse EdTech intervention, designed to improve attainment in basic English literacy and mathematics by grade 1 learners, aligns with the education policy in Sierra Leone, as called for by Hollow and Jefferies (2022), (ii) the capacity and experiences of teachers in remote districts in Sierra Leone to integrate this personalised EdTech intervention successfully into their daily practice, as called for by Major et al. (2021), and (iii) how receptive local communities are to the introduction of this EdTech intervention into the primary school system, in response to Pitchford (2023).

Education policy in Sierra Leone

To address the significant challenges with primary education faced by Sierra Leone, the Ministry of Basic & Secondary Education (MBSSE) published the National Curriculum Framework and Guidelines for Basic Education in Sierra Leone (The Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education, 2021a). The new curriculum embodies the Government’s Radical Inclusion Policy (The Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education, 2021b), which is grounded in the ideology of inclusion for all and focuses on four excluded and marginalized groups: children with disabilities (SEND); children from low-income families; children in rural and underserved areas; and girls. This provides a framework for transformative education through an innovative and inclusive curriculum and multi-stakeholder partnerships, both national and international, that is expected to: (1) facilitate equity and radical inclusion with a chance for every child to learn and succeed in life, regardless of gender, ethnicity, disabilities, poverty, or other life circumstances, (2) fulfill the hopes and aspirations of learners and their parents, as well as local communities and the nation by improving quality and restoring integrity in education, (3) enhance employability and livelihoods through appropriate skills training and talent cultivation, (4) support national unity, civics, good governance, and nation building, through the celebration of the country’s rich ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity, and (5) help children to achieve their human potential by safeguarding knowledge and practices that enhance their overall health and well-being.

The new curriculum aims to facilitate education as a right for all Sierra Leonean children and is based on the United Nation’s framework for rights-based education (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2007). It emphasizes holistic and child-centered learning, that priorities the needs of individual learners, as well as the role of education in creating peaceful and equitable societies. There is also an emphasis on Teacher Professional Development for the integrity and quality of the educational system and a call for collaboration between different actors, state, and non-state, for achieving the new transformative curriculum for basic education. The national framework also stipulates that the language of instruction should be English, which is the official language of Sierra Leone. Accordingly, increased time has been allocated to teaching basic English literacy skills, with an emphasis on letter sounds in the early primary grades 1–3. However, teaching in the different home languages of Sierra Leone is accepted in the early primary grades 1–3 to facilitate understanding and effective communication. The National Policy on Radical Inclusion also calls for a review of the use of assistive technologies to support learners’ individual needs (National Policy on Radical Inclusion section 3.3.1, p.38). The importance of foundational skills is further prioritized in Sierra Leone’s 2022–26 Education Sector Plan as the basis for long-term educational success by all children (Sengeh and Winthrop, 2022). The MBSSE are thus investing heavily in foundational learning during primary school.

Context of the current study

The onecourse EdTech intervention investigated here was implemented with grade 1 learners in partnership with Save the Children and the Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO; a non-governmental organization that works with national and international volunteers to deliver programing on the ground to alleviate poverty). Software was provided free-of-charge by onebillion, and hardware was supplied by JP: IK. Once installed on the tablet, children can interact with the software offline, so internet connectivity is not needed. The study took place in two remote and marginalized districts of Sierra Leone—Pujehun and Kailahun. Due to their remoteness, these districts are amongst the most disadvantaged in the country, with similar characteristics in terms of vulnerability and provision of education facilities—see Supplementary Materials. Due to the remote geographical location and difficulty with access (including having to cross rivers in many areas which requires the use of boats), Save the Children is the only actor in many areas of these districts. Accordingly, as partners in this project, 20 primary schools that Save the Children are operating in to deliver their Building Futures program took part in this research.

The 2019 Annual School Census highlights the status of education provision and multi-dimensional educational challenges faced by girls and boys in Sierra Leone. Findings show that 96.9 and 83.3% of schools operating in Pujehun and Kailahun, respectively, are government approved. There are a significant number of untrained, unqualified, teachers with 43.5% of teachers in Pujehun and 50% in Kailahun holding only a basic level qualification (i.e., WASSCE/O’Level). The distribution of female and male teachers in primary schools in both districts is uneven: in Pujehun there are 237 female teachers (16%) and 1,262 male teachers (84%) and in Kailahun there are 497 female teachers (19%) and 2,118 male teachers (81%). Between 2018 and 2019, after the introduction of the Free Quality School Education Program in Sierra Leone (MBSSE, 2018), there was an increase in primary school enrolment across both districts: in Pujehun enrolments increased from 45,559 to 67,459 students (48.1% increase) and in Kailahun enrolment increased from 79,791 to 95,621 students (19.8% increase). At the same time, between 2018 and 2019, there was an increase in the total number of primary schools across both districts: in Pujehun the number of primary schools increased from 285 to 287 (2 schools, 0.7% increase) and in Kailahun from 390 to 396 (6 schools, 1.5% increase). The pupil-teacher ratio in Pujehun is 1:45 and 1:37 in Kailahun: the national average is 1:37. The increase in primary schools across these two districts between 2018–19 was disproportionate to the high increase in primary school enrolment, especially in Pujehun district. This will have placed additional stressors on an already fragile education system.

At all levels of primary school, 50%–51% of enrolled students are girls, however by the final year of senior secondary school this drops to 47.5%. Needs assessments conducted by Save the Children identified the main factors contributing to children dropping out of primary and secondary school in these communities. These include lack of support from parents, over-crowded classrooms, issues in the classroom, high cost associated with school fees, low-income earnings of parents/caregivers, schools not accessible for children living with disabilities, access to secondary education, and early marriage and teenage pregnancy. The Annual School Census 2019 reports Pujehun to have the lowest textbook ratio in government assisted primary schools for both English (language of instruction) and maths, whereas Kailahun has the 7th lowest for English and 6th lowest for maths. This contextual analysis of the project location suggests that while both districts are marginalized and vulnerable to inadequate education provision, Pujehun is especially at risk.

The objective of this study was to examine the broader impacts of the onecourse EdTech intervention for policy, teachers, and community members in these remote districts of Sierra Leone, as these are all key actors in the primary education ecosystem. An impact evaluation of this EdTech intervention in raising basic English literacy and maths skills of grade 1 learners in Sierra Leone is reported by Pitchford and Lurvink (in preparation).

Methods

Design

A mixed methods approach was adopted, that involved four strands of investigation: (1) a policy mapping exercise to investigate how the onecourse EdTech intervention employed in this study aligned with the National Curriculum Framework and Guidelines for Basic Education in Sierra Leone, (2) a survey to establish the capacity of teachers in rural districts in Sierra Leone to deliver a personalized EdTech intervention in their classrooms to support the learning of foundational skills in English, (3) interviews to garner teachers’ perceptions and experiences of using the EdTech intervention in their daily practice, and (4) focus groups to gather views as to how the EdTech intervention was received by parents and other community members.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was awarded by the Government of Sierra Leone Office of the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee, Ministry of Health and Sanitation Directorate of Policy, Planning & Information (DPPI). The research presented minimal risk to participants. All participants in this study were required to give informed consent prior to taking part in the research. According to ethical requirements, the identity of all participants was anonymized and only group findings are reported. All data collection, coding, and entry complied with GDPR legislation and data was stored securely using password protected files, accessible only to the research team.

Participants

Head teachers and class teachers from the 20 participating schools took part in three research strands: a survey of capacity needs, post-intervention interviews, and focus groups. Members from the local community also participated in focus groups. A sample of 57 participants, drawn from 19 of the 20 participating schools, took part in the survey of teacher capacity needs. The enumerators mistakenly omitted to administer the survey at one school in Pujehun as it had been assigned as a control school (see below). Hence, the sample consisted of 19 head teachers (9 from Pujehun, 10 from Kailahun) and 38 class teachers (15 from Pujehun and 23 from Kailahun), of which 12 (1 in Pujehun and 11 in Kailahun) were ordinary teachers. A distinction was made by the participating schools between class teachers and ordinary teachers, where a ‘class teacher’ was assigned to a specific class with the responsibility of monitoring learners’ attendance, teaching the class, and preparing report cards, and an ‘ordinary teacher’ had no responsibility to manage a class, but taught where they were asked to do so, especially when the class teacher was not present. The composition of this sample was determined by the teachers that had been selected to deliver the onecourse intervention in the school. An opportunity sample of 11 head teachers and 22 class teachers (33 in total) from across Pujehun (11) and Kailahun (22) districts were interviewed toward the end of the project, to garner their views and experiences of using the EdTech intervention to support children’s learning of basic literacy and mathematics. These participants were available on the day the enumerators visited the schools. An opportunity sample of 54 head teachers and class teachers (27 from each district) and 170 community members (84 from Pujehun and 86 from Kailahun) participated in the focus groups. Again, these participants were available on the day the enumerators visited the schools and communities. Where possible, separate focus groups were held with high-status community members (e.g., village chief, mammie, or queen, and religious leaders) and lower-status community members (parents and other members of the community) to encourage participation from all levels of the community.

Implementation of the EdTech intervention

Different and novel implementation modalities were piloted in this project to ascertain the best way to deliver the EdTech intervention in the local contexts of Pujehun and Kailahun districts in Sierra Leone. The reason for piloting different and novel implementation modalities in Sierra Leone arose from difficulties by teachers implementing this EdTech intervention through a particular modality in Malawi, in which small groups of children accessed the technology in a Learning Centre away from the rest of the class (Pitchford, 2015, 2023). High class sizes and short school days for grade 1 learners in Malawi resulted in difficulties in all children accessing the technology with sufficient time on task for it to be effective. Thus, this study piloted four different and unique implementation modalities that were designed to promote access to the technology for grade 1 learners. The different implementation modalities piloted in this study were: Split Class which allowed the teacher to work with half the class while the other half worked with the tablets in the classroom; Tablet Sharing which required the teacher to pair children to work on the tablet together in the classroom; Remedial in which targeted children that were struggling to learn in class, or the wider school environment, were given access to the tablets; and Projector which enabled the teacher to share the software content with the whole class through a projector. Teachers could select the software in one of two different modes: Adaptive mode created a lesson for each child based on performance of a short in-built test in the software, whereas Teacher mode enabled the teacher to select the learning units they wanted children to work on.

Of the 20 participating schools, eight schools served as a comparison to practice as usual and did not use the technology. The remaining 12 schools implemented the EdTech intervention via one of the different implementation modalities described above. Prior to implementation, teachers were trained in how to use the technology (e.g., how to turn on the tablet, how to increase the volume, how to connect the headphones etc.) and how to deliver classes using onecourse software. Training was designed by VSO and onebillion, and was provided in person, locally, for 2 h, by the VSO education specialists supporting this project. Training was attended by the head teacher and class teachers responsible for implementing the EdTech intervention in the schools. Children were then baseline assessed on standardized measures of literacy and numeracy, after which schools implemented 60 sessions of the intervention, each session lasting 45 min. At the end of the intervention period, children were endline assessed on the same measures of literacy and numeracy given at the start of the study. Teacher interviews and focus groups were then conducted following the protocols outlined below.

Procedure

For each of the four strands of investigation, details of the procedure followed are given below.

Policy mapping exercise

The National Curriculum Framework and Guidelines for Basic Education in Sierra Leone document was accessed online and scrutinized by the first author and key components identified. For each component, the EdTech intervention employed in this study and any previous research relating the intervention was considered.

Survey of teacher capacity needs

The survey consisted of five questions about capacity and training needs for teaching core foundational skills with and without EdTech, as well as questions about the role of the participant in the school and their maximum level of education attained. See Appendix 1. The survey was administered orally to individual participants and their responses were recorded manually by VSO education specialists supporting this project during sensitization meetings held in each district at the start of the study who served as enumerators for this study. As this project was conducted during the global COVID-19 pandemic, when international travel restrictions were in place, it was not possible for the research team to collect the data in situ. Thus, the second author (lead investigator) provided online training to the Program Manager and Monitoring and Evaluation Manager at VSO Sierra Leone, who in turn then trained the enumerators. Three months later, the Monitoring and Evaluation Manager at VSO asked participants an additional four questions about their capacity for teaching in English, as this was overlooked at the start of the study (Appendix 1).

Teacher interviews

Semi-structured interviews with head teachers and class teachers were conducted toward the end of the project to garner their views and experiences after using the EdTech intervention to support children’s learning of basic literacy and mathematics, according to the themes and questions specified in the interview protocol reported in Appendix 2. VSO education specialists supporting the project administered the interviews with class teachers and head teachers on an individual basis, in a quiet area of the school, free from distraction. As above, they were trained by the Program Manager and Monitoring and Evaluation Manager at VSO Sierra Leone in how to conduct the interviews, having been trained themselves online by the lead researcher. Responses to the questions posed were recorded manually and any comments made by the participants during the interview were noted.

Focus groups. The focus group protocol was co-developed by the first author and the VSO education and community engagement specialists supporting the study, to ensure the format, activities, wording of questions, and group composition was appropriate and sensitive to cultural needs (see Appendix 3). All VSO staff, including the first author, were based in Sierra Leone at the time that the focus groups took place. The community engagement specialists were nationals of Sierra Leone, one education specialist was a Sierra Leone national, and one education specialist was from Malawi. The VSO community engagement specialists selected participants to take part in the community focus groups, considering local politics, and based on their knowledge of the local communities. All teachers implementing the EdTech intervention in their classes were invited to participate in the teacher focus groups. Depending on their availability on the day the enumerators visited the school and the number of teachers involved in delivering the intervention in each school, three to five teachers from each school participated in each teacher focus group. In total, 36 focus groups were held, 18 in each district. Each focus group lasted between 60 and 90 min. The VSO community engagement specialists facilitated the community focus groups which ensured that every member of the group had an opportunity to share their thoughts on the project. As the first author was not versed in the languages of Sierra Leone, they were present during the focus groups but sat at an appropriate distance from the discussion, took observation notes, and ensured protocols were followed. Focus groups with teachers and head teachers were co-facilitated by the education specialist and first author. Questions were posed to participants either in English, Mende, or Krio, as required by the group composition. Participants responded in Mende or Krio and a designated VSO community engagement specialist, who acted as interpreter during all 36 focus group discussions, interpreted responses into English so the first author could record them manually.

Results

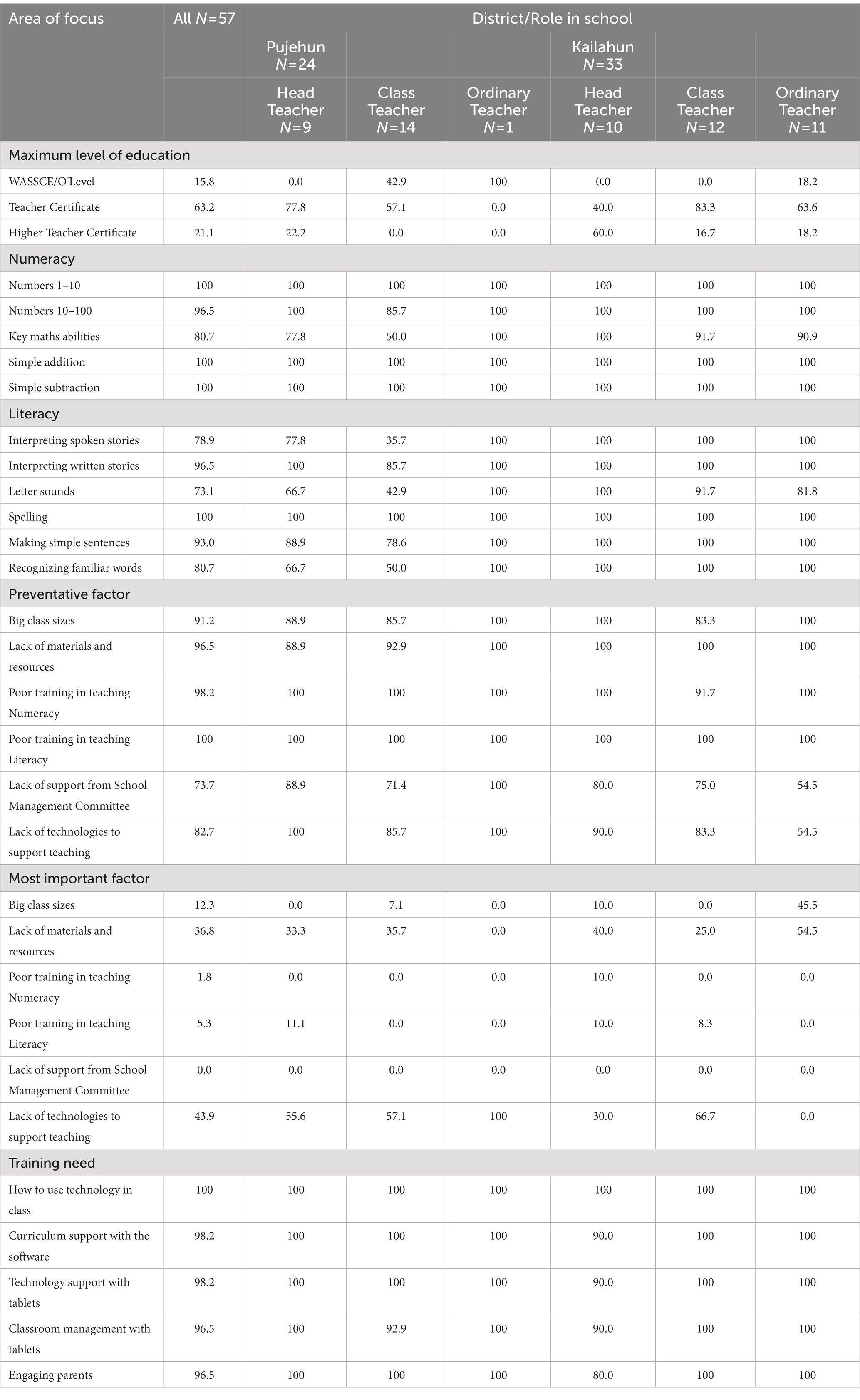

Findings from the policy mapping exercise were triangulated with data obtained from the survey of teacher capacity needs, post-intervention teacher interviews, and focus groups with teachers and local communities. To characterize responses from the participants in this study, summary statistics (frequency of response) were determined for the teacher capacity needs survey data and the fixed response questions included in the teacher interviews. Results are reported in Tables 1, 2, respectively. Qualitative data from the open-ended questions in the teacher interviews and focus groups was subjected to an aggregative, semantic thematic analysis, where participant comments were taken at their word, with little interpretive process taking place. Manual coding was undertaken by the first author, who was immersed in the study setting and investigation with the participants. This sensitization supported the credibility and dependability of the thematic analysis (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

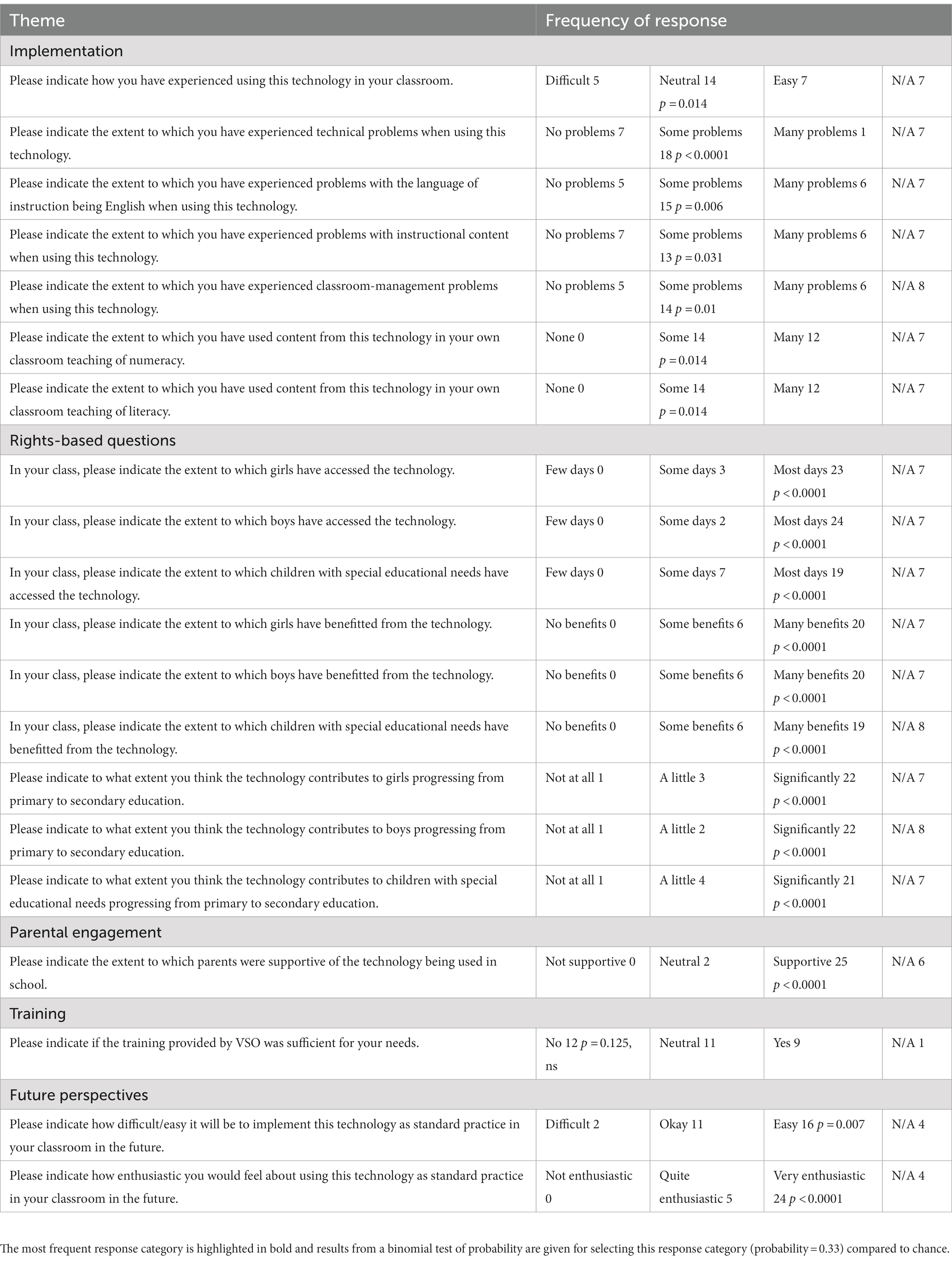

Table 2. Frequency of responses given by the sample of 33 head teachers and class teachers interviewed towards the end of the study.

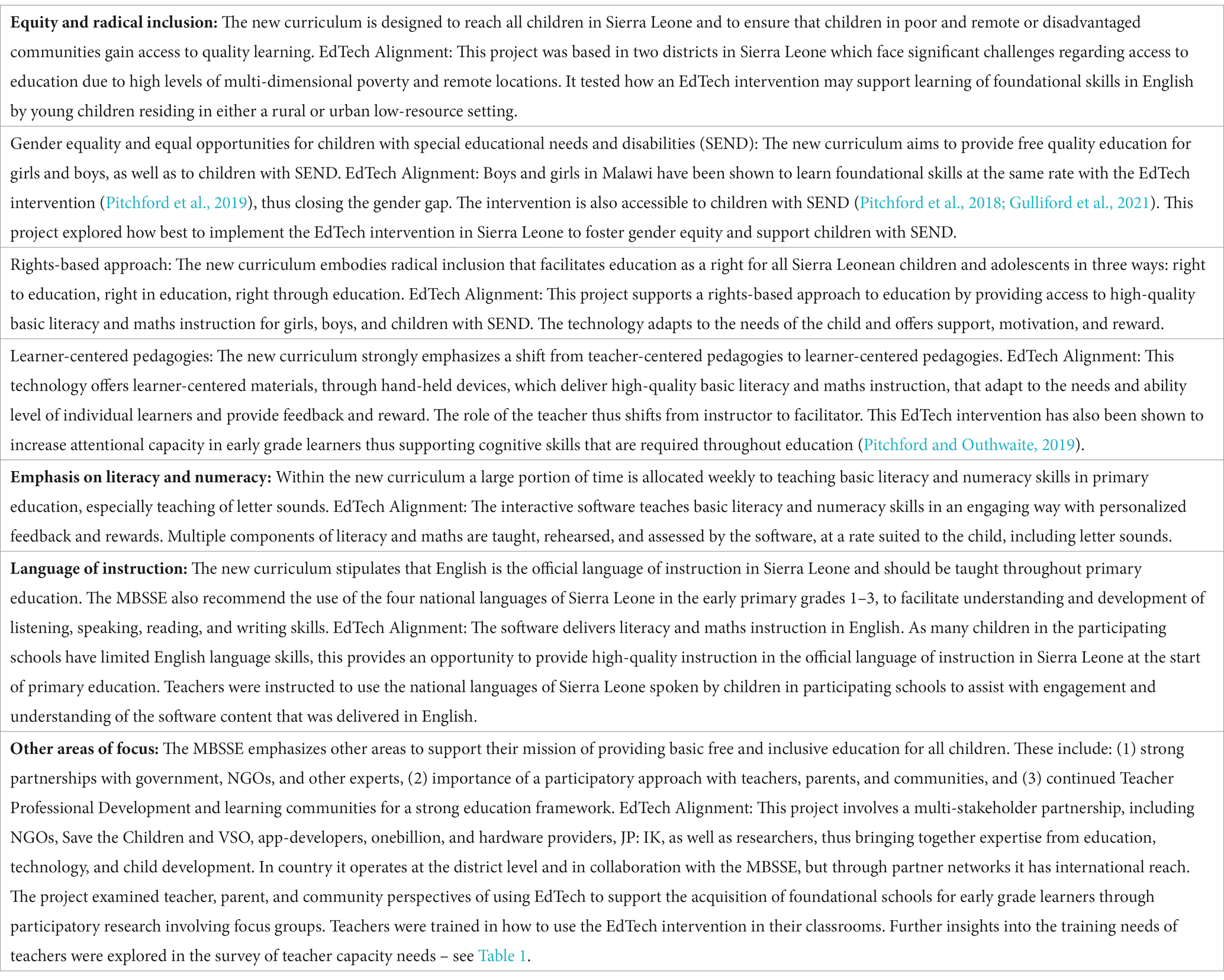

Policy mapping

Results from the policy mapping exercise are summarized in Table 3. As can be seen, several features of the EdTech intervention employed in this study aligned with key components of the National Curriculum Framework and Guidelines for Basic Education in Sierra Leone.

Table 3. Mapping of the onecourse EdTech intervention used in this study to key components of the National Curriculum Framework and Guidelines for Basic Education in Sierra Leone.

Survey of teacher capacity needs

Results revealed the level of education attained by participants differed significantly across district and role. As shown in Table 1, none of the participants had attained degree level education: 15.8% of the sample had WASSCE/O’Level qualifications, 63.2% had a Teacher Certificate, and 21.1% had a Higher Teacher Certificate. A 2 (district) × 3 (education level) chi-square test revealed that the education level of participants in Kailahun was significantly higher than that of participants in Pujehun (χ2 = 7.89, p = 0.019, 2-tailed). Furthermore, a 3 (education level) × 3 (role) Fisher’s Exact test revealed that Head Teachers had a significantly higher level of education than Class Teachers and Ordinary Teachers (p = 0.016, 2-tailed).

Table 1 shows that participants were more confident in teaching basic numeracy skills (mean = 95.4%, range = 80.7% to 100%) than basic literacy skills (mean = 87.0%, range = 73.1% to 100%). The observed frequency of participants reporting to be confident in teaching basic numeracy skills across the five questions asked in the survey was significantly greater than the observed frequency of participants reporting to be confident in teaching basic literacy skills across the six questions asked in the survey, as confirmed by a 2 (confidence) × 2 (domain) chi square test with Yates correction (χ2 = 11.986, p = 0.0005). In addition, participants reported being confident in teaching more other numeracy skills (28.1%) than other literacy skills (15.8%) than asked about in the survey, however this distribution did not differ significantly from chance, as established by a 2 (confidence) × 2 (domain) chi square test with Yates correction (χ2 = 1.845, p = 0.174, ns). For numeracy, participants were least confident in teaching key maths abilities, such as quantities, colors, and shapes (80.7%), especially in Pujehun. For literacy, participants were least confident at teaching letter sounds (73.1%) and interpreting spoken stories (78.9%), especially in Pujehun, which are key components of the new national curriculum in Sierra Leone.

As shown in Table 1, most participants believed all factors asked about in the survey contributed to poor attainment in numeracy and literacy skills in Sierra Leone and few suggestions (1.8%) as to other contributing factors were raised. When asked to identify the most important factor, most participants reported lack of technologies to support teaching (43.9%) and lack of materials and resources (36.8%), which combined accounted for 80.7% of responses. This was consistent across district and role. Most participants wanted training in all aspects of the EdTech intervention asked about in the survey. Participants in Pujehun district mostly identified the need to be trained in assessing learning and maintenance of the technology.

Data was available from 60 eligible participants for the additional questions regarding confidence in teaching in English as the language of instruction in Sierra Leone, which were administered 3 months after the start of the project. Results revealed 58% of participants (28% from Pujehun; 30% from Kailahun) were very confident and 42% of participants (17% from Pujehun; 25% from Kailahun) were quite confident about teaching literacy and mathematics in English without the use of technology. A similar distribution was found for teaching with technology: 53% of participants (23% from Pujehun; 30% from Kailahun) were very confident and 47% of participants (15% from Pujehun; 32% from Kailahun) were quite confident about teaching literacy and mathematics in English with the use of technology. When asked about children’s ability to learn English literacy and mathematics with the technology, 30% of participants (11% from Pujehun; 18% from Kailahun) thought children would be able to follow instruction in English when delivered by the technology, 68% of participants (32% from Pujehun; 37% from Kailahun) thought children would struggle to learn when given instruction in English when delivered by the technology, and 2% of participants (from Pujehun) thought children would not be able to understand instruction in English so will not be able to use the technology. This distribution differed significantly from chance as determined by a one-group chi square test (χ2 = 40.3, p < 0.00001). Finally, all participants commented they would help children understand the English instructions and content of the technology by translating into the children’s home language.

Teacher interviews

Results from the post-intervention teacher interviews are reported in Table 2. As 7 participants were from control schools many of the questions asked were not applicable to these participants so are recorded as not applicable (N/A). In addition, some responses were missing from the data provided by the VSO educational specialists who interviewed the participants in the field, so these have been added to the N/A category. As shown in Table 2, the most frequent response category is highlighted in bold. For each question posed, a binomial test of probability was conducted for selecting the most frequent response category (probability = 0.33) compared to chance. Results are presented in Table 2.

As can be seen, participants reported some problems with implementing the EdTech intervention, but all used content from the software in their standard classroom practice to teach numeracy and literacy some or most of the time. Most participants considered the EdTech intervention supported children’s rights to quality basic education, as boys and girls and children with SEND were frequently given access to the technology. Participants perceived the EdTech intervention benefitted children’s acquisition of basic numeracy and literacy and would facilitate progression from primary to secondary school. Parents were reported as being mostly supportive of the project and participants reported that the EdTech intervention would be easy to embed within their future standard classroom practice and were mostly enthusiastic for this to happen. Twelve participants rated the quality of the training they received prior to implementation as being inadequate for their needs, although this frequency of responses did not differ significantly from chance.

Focus groups

Four key themes were identified through the thematic analysis of the qualitative data obtained from the open-ended questions of the post-intervention teacher interviews and focus groups with teachers and community members, as summarized below.

Theme 1: Teacher professional development

The need for further training was emphasized by teachers, specifically in the content and pedagogy of the software, how to embed the software pedagogy within their standard classroom practice, and how to manage their classroom and time effectively when using the technology. Teachers requested access to a tablet for themselves, so they could examine the software content to prepare their lessons well. Teachers reported that they had learnt from the software content, especially for letter sounds and spelling. One teacher commented: “I did not understand English before, but now I do, particularly letter sounds teaching and pronunciation.” Teachers also mentioned that the tablet content was easier to deliver than the syllabus provided by the MBSSE. Finally, teachers preferred the teacher mode of the software over the adaptive mode, as the teacher mode enabled them to align the EdTech intervention content with the curriculum and planning, facilitate sessions more easily, and monitor pupils’ progress.

Theme 2: English as the language of instruction

Teachers and community members reported that children’s foundational skills had improved with the EdTech intervention, in particular literacy. They commented that children learnt fast with the technology and improved in different aspects of literacy, especially letter sounds. Teachers also commented that they learnt from the letter sounds activities in onecourse. However, teachers indicated that instruction in English presented a barrier to learning, as the accent of the in-app teacher was being difficult to understand, and one teacher recommended “to add some African sauce to the English” so that it would resonate more with their own English. Some teachers said that the language barrier was an issue at the start of the intervention but ameliorated over time. Community members also reported that children were speaking English at home and that the children’s Krio had also improved. Teachers perceived the main benefits for continued use of this EdTech intervention to be improved numeracy and literacy skills of early grade learners and the impact this would have on higher grades, as they considered it will be easier to teach children in higher grades who have strong foundational skills in English.

Theme 3: Special educational needs and disabilities

Teachers identified both opportunities and challenges in delivering the EdTech intervention with children with SEND. Opportunities included helping children with SEND to write, benefiting visually-impaired children to learn as the tablet is closer to the child than is the chalkboard, benefiting slow learners as children progress through the software at their own pace, engaging children with cognitive difficulties who often do not respond to standard instruction but respond well to tablet instructions and tasks, and being able to increase the volume for hearing-impaired children enabling them to engage with the learning process. Challenges included the risk of children with SEND damaging the tablet, the volume of the projector being too low so hearing-impaired children struggle to access the content, the software not being accessible for children with low vision/blindness, and time management of using the technology for children with SEND. Most teachers emphasized the need for children with SEND to access the EdTech intervention so “they feel belonging.” Teachers also emphasized that children with SEND needed special attention and encouragement, and required a special class/session, when using the technology.

Community members were aware of different types of disabilities and indicated that they wanted to support children with disabilities to attend school, remove barriers, and prohibit discrimination, and they vouched to protect them. Many requested assistive devices so children with SEND could attend school. Most community members thought all children, including children with SEND, should have access to the EdTech intervention. Parents and other community members also reported that including children with SEND in the EdTech intervention engendered a sense of belonging with their peers. However, community members mentioned that teachers needed to be trained on how to support children with SEND. Some communities expressed the need to have a special space for children with SEND that is safe and where they are supported by trained teachers so they can learn effectively.

Theme 4: Active community engagement

Teachers identified support from the community in sending children to school, monitoring of children and teachers, and keeping the learning environment clean and safe. Community members were highly supportive of the project and reported the following benefits: a feeling of pride within their community for being given the technology, increased school attendance, enrolment, and punctuality, a change in children’s attitude toward and eagerness to attend school, parents were eager to send their children to school, transference of knowledge from children to parents, “As parents we have started learning from our kids at home,” increased parental engagement in their children’s learning as parents visited the school more regularly, increased confidence in children’s ability as their literacy and maths skills improved, and an increase in children’s digital skills as children were now helping parents to use their phones.

Community members expressed they would like to support the project in moving forward by monitoring children’s attendance and behavior, providing security for the tablets, supporting children, including those with SEND, to attend school, and setting up bylaws against discrimination of children with SEND. Community members also reported they would like the technology to be accessed by other classes beyond grade 1. Several communities expressed the need for an additional classroom, due to the increased number of children attending school because of the EdTech intervention. All participants wanted the technology to be accessed by all grade 1 learners, not just those requiring remedial support.

Discussion

This study investigated how the introduction of an EdTech intervention—onecourse—designed to support the acquisition of foundational skills, for use with grade 1 learners in primary schools into two remote districts of Sierra Leone was perceived by teachers and community members and aligned with the primary education policy of Sierra Leone. Collectively, the results of this investigation indicated that the EdTech intervention employed in this study has potential to support a transformative basic education curriculum through an innovative and inclusive curriculum with multi-stakeholder partnerships. Four key themes emerged that address Sierra Leone’s pathway to “locally rooted but globally informed education goals” (page 14, Sengeh and Winthrop, 2022). These themes also highlight issues of availability, accessibility, acceptability, and adaptability, as described in the 4As framework by Barry (2022), Special Rapporteur to the Human Rights Council, in their report on the risks and opportunities of the digitalization of education and their impact on the right to education.

The first theme that emerged from this study focused on Teacher Professional Development, needed for building, and maintaining, integrity and quality of the educational system (The Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education, 2021a). The survey of teacher capacity needs revealed the necessity to enhance the education level of teaching staff across the two districts where the study took place, especially for teaching basic English literacy skills, where confidence amongst teachers was low, particularly for teaching letter sounds which is a key component of the new national curriculum. Results showed that teachers were significantly more confident in teaching basis numeracy than basic literacy skills, highlighting the need for continued professional development of teachers to be able to deliver high-quality instruction in basic literacy skills. Interestingly, teachers reported that the onecourse software was a useful teaching and learning resource, especially for delivering instruction in English, and that their interactions with the software had improved their knowledge and skills of teaching English literacy. Hence, there is potential for onecourse to be utilized as a form of continuous teacher professional development that could address the lack of confidence in teaching English literacy skills, as revealed by teachers in this study. This raises the possibility that EdTech interventions designed for child-centered learning may also be of benefit to teachers in facilitating their delivery of high-quality education and could serve as a useful training aid to enhance their daily practice.

This study was conducted in two marginalized and remote districts of Sierra Leone where access to teaching training and educational resources is limited. Interviews and focus groups revealed that class teachers and head teachers considered the quality of the training received prior to using the EdTech intervention in their schools was mostly inadequate for their needs. The 2-h training session given to schools in this study by the implementation partners focused on how to use the tablet technology, whereas results from this investigation indicated that teachers required training in the software content and pedagogy and how to align the EdTech intervention with the national primary education curriculum of Sierra Leone. It was clear that a 2-h training session focused on technical features of the hardware was insufficient to meet the needs of teachers who were not familiar with using digital technology in the classroom to enhance their practice. Rather, teachers required time to interact with the software, to appreciate the breadth of content covered by the app and consider how this might be used to improve their daily lesson planning and delivery. Seemingly, the training approach adopted here could be interpreted as somewhat colonial (Lansari and Haddam Bouabdallah, 2022). Clearly, it is important that as this program scales, the training of teachers should be modified and improved to meet the needs of those who are delivering the intervention within primary schools in different countries and contexts.

Along related lines, results showed that teachers preferred the autonomy afforded by the teacher mode of the software over the adaptive mode, as the teacher mode facilitated their ability to plan sessions in line with the national curriculum and monitor student progress. Moreover, teachers found the software content easier to deliver than the syllabus provided by the MBSSE, indicating that this technology has potential to address the gap in teacher capacity needs identified by this study, particularly for teaching foundational English literacy skills. This is important as teachers’ attitudes toward EdTech and ways of using it have been significantly linked to learning outcomes in literacy and numeracy in Western contexts (Higgins and Moseley, 2001). However, the preference by teachers for the teacher mode of the software, over the adaptive mode which promotes personalized learning adapted to individual abilities, is at odds with the results of a recent meta-analysis, which revealed personalized EdTech interventions led to significantly greater learning outcomes than those linked to learners’ interests, feedback, support, and/or assessment (Major et al., 2021). Clearly, for this EdTech intervention to be taken forward, teachers’ capacity to use the software effectively to support their daily practice needs to be carefully balanced with the propensity of the adaptive software to improve learning outcomes. As Major et al. (2021) acknowledged, teachers require professional development that will equip them with the knowledge to integrate personalized EdTech interventions with other teaching activities.

The second theme focused on the use of English within the software to deliver instruction, as English is the official language of instruction in Sierra Leone. Before implementation of the EdTech intervention, teachers thought instruction in English would pose significant challenges for most grade 1 learners and by the end of the intervention teachers reported that they needed to scaffold children’s comprehension by translating instructions/content used in the software into the children’s home language while providing additional instructions for clarification. However, it was reported that instruction in English became easier with increased exposure to the software, for both learners and teachers. By the end of the study, teachers commented on the speed at which children learnt with the software, especially letter sounds, and how this would facilitate rights through education as they thought it would be easier to teach children in higher grades with strong English foundational skills. As the national curriculum places specific emphasis on letter sounds in the early primary grades 1–3, instruction with this EdTech intervention might provide an effective means of using the increased time that has been allocated to teaching foundational English literacy skills in Sierra Leone, especially for teachers who are not confident about their ability to teach in English.

As Hennessy et al. (2021) note, “issues of language and multilingualism are constantly in flux, particularly as national education curricula change” (page 26). They referred to Wagner (2017) to demonstrate that children who are taught in an official language of instruction that differs from the language(s) spoken at home often underachieve at school. Instruction in English as part of an inclusive education policy can therefore be debated. In Sierra Leone, English is also the language of opportunities for social mobility. Gellman (2020) argues that “since English operates as the high-status language in Sierra Leone, the shift to Krio may produce better language cohesion for people across ethnic groups, but will not allow most people access to the middle and upper class jobs, including politics and international development that continue to require English” (p. 141). In Sierra Leone, languages are also strongly tied to ethnic identity. As such, instruction in English, rather than the home languages of Sierra Leone, could be contested as supporting an inclusive approach to learning, and may further increase the divide between richer and poorer communities. However, Fyle (2003) shows that the issue of language is complex in post-independence Sierra Leone as instruction in Krio, Sierra Leone’s current lingua franca, could have repercussions for equity as well, since Krio is the language of the relatively small (1.2%) Krio population in Sierra Leone (Census 2015). Nonetheless, 18.2 percent of the population speak Krio as their main language (Census, 2015). Furthermore, in post-civil war Sierra Leone, multilingual classrooms, where multiple languages are spoken by both learners and teachers, are common. However, there is potential for EdTech interventions to be used flexibly to support learning in multilingual classrooms, either by teachers translating instructions and content into the language(s) spoken at home, as was demonstrated in this study, or when the software is available in different languages (Pitchford et al., 2021). Also, the various implementation modalities trialed in this study could support the learning of English foundational skills in different ways. For example, when implementing the intervention to the whole class using a projector, teachers can translate the content and instruction given in English by the onecourse software into the children’s home language(s). In contrast, when the software is available in multiple languages, implementation modalities requiring children to work individually or in pairs with the software might be optimal, as children can switch between instruction in their home language and language of instruction at their own pace (Pitchford et al., 2021).

UNESCO (2016) estimated that 40% of children are taught in a language that is not spoken at home, so children often cannot comprehend what is being taught, especially at the start of primary education. However, this study has demonstrated that grade 1 children in Sierra Leone were able to learn foundational skills in English, after 45 h of instruction with the onecourse software (Pitchford and Lurvink, in preparation). The onecourse software provides a consistent form of English instruction that is accessible to all children, irrespective of their home language(s) and their teachers competency in English, so it equalizes opportunities for children to acquire the official language of instruction from the start of primary school. Continued use of this EdTech intervention throughout primary school could prevent an attainment gap from emerging amongst different groups of learners (Pitchford et al., 2019) and could provide all children with a strong foundation in English which is required for progression through education in Sierra Leone. Previous research has shown that when onecourse was introduced into a rural primary classroom in the Kwa-Zulu Natal Province of South Africa, where isiZulu is the predominant language, parents preferred their children to be taught in English by the software rather than isiZulu, as they believed that mastery of English will provide their children with better opportunities (Pitchford et al., 2021). Clearly, the issue of English as the language of instruction in Sierra Leone is challenging for their inclusive education policy but there is potential for EdTech interventions to address some of these challenges, as demonstrated here. Continued research and nuanced reflection on how personalized education technologies might support teaching and learning in multilingual classrooms is required.

The third theme centered on the use of EdTech for children with SEND. While some children with SEND experienced physical difficulties with operating the tablets several benefits were identified in promoting an inclusive learning environment where children with SEND felt they belonged to an EdTech class, and the in-app features empowered them to learn with the onecourse software. Previously, Pitchford et al. (2018) suggested a range of adaptations that could be made to the onecourse software to enhance accessibility and engagement for children with SEND. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the two software modes gave flexibility to teachers in how to optimize support for children with SEND. For example, if teachers wanted to target instruction on a particular skill, they could use the teacher mode of the software to select specific learning units, while the adaptive mode of the software tailored instruction to each child’s ability, thus fostering a personalized learning program that the child could work through at their own pace. The different modes of the onecourse software thus provides teachers with autonomy and flexibility to enable them to master and configure the technology in their own way to adapt to the needs of their class (Barry, 2022). This highlights that building flexibility into how EdTech can be used in the classroom affords the potential to unlock both access and quality of education for children with SEND (Kuper et al., 2018). This is important as children with SEND are among the most marginalized groups in LMICs (Hennessy et al., 2021) and, like all children, have a right to quality education.

However, concerns about rights of access to education were raised that were based on the remedial implementation modality piloted here, where only children who were struggling to acquire foundational skills were given access to the EdTech intervention, to try to narrow the attainment gap. This study revealed strong agreement amongst teachers and community members in Sierra Leone that all children should have access to the technology, not just children with SEND. However, teachers and community members also suggested the need for a separate EdTech class or session just for children with SEND, as these children required special attention and encouragement to learn with the technology that could not be easily met by teachers in a regular class environment that included non-SEND learners. This suggestion could be construed as conflicting with Sierra Leone’s radical inclusion policy but creating a safe and supportive learning environment where children with SEND can engage with EdTech could be seen to align with the right to quality education and the right to respect participation in the learning environment (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2007). Clearly, determining how best to support children with SEND in using EdTech effectively at primary school while facilitating equity and radical inclusion without discrimination requires difficult decisions to be made by policymakers, educators, and caregivers (Hennessy et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2022).

Finally, the fourth theme to emerge from this study involved the role of the community in supporting the introduction and sustained use of EdTech in primary schools. The focus groups highlighted how community members perceived themselves as an active partner in the EdTech intervention, by supporting and encouraging children to attend school, increasing parental engagement in their children’s learning, and enabling a clean and safe learning environment, particularly for children with SEND. As this study was conducted in two of the most marginalized districts in Sierra Leone, it demonstrates how EdTech can promote a sense of pride amongst community members and can foster active community engagement with the education system. Sengeh and Winthrop (2022) fully acknowledged the importance of community-school collaborations within the education eco-system and the need for community voice in participatory policy design for transformative education. They referred to Barton (2021) who highlighted that participatory policy design approaches, which included community members alongside teachers, students, and education system leaders, were important for successful reform of education systems in Portugal, Finland, and Canada. This study clearly demonstrates the desire and aspirations of community members to be active stakeholders in EdTech interventions that improve the quality and restore integrity in education in Sierra Leone (The Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education, 2021a). Involving community members, especially from the most marginalized districts, will be critical in determining how to scale EdTech interventions within Sierra Leone to ensure sustainability.

Limitations

This study was conducted in 2021 in the middle of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Although schools were open in Sierra Leone when the study took place, international travel restrictions prevented the researchers from supervising the data collection of the teacher capacity survey and interview data in situ. Consequently, a ‘train the trainer’ model was adopted, in which the lead investigator (second author) provided online training to senior staff at VSO in Sierra Leone in how to administer the evaluation tools, who then trained local enumerators in-person on the ground. The lack of researcher oversight in the administration of the teacher capacity survey and interview tools resulted in some omissions in data acquisition for the teacher capacity survey and reliance on opportunity sampling for the teacher interviews. As such, a full set of data was not collected for these two measures. However, when travel restrictions were eased, the first author was able to join the project in Sierra Leone, so was able to supervise the administration of the focus groups from the ground. Such challenges in data acquisition are not uncommon to applied field research in resource-poor settings, such as Sierra Leone (Acharya and Pathak, 2019), but these were exaggerated by global pandemic in this study. However, all data processing (entry, coding, and analyses) was conducted by the research team only and the data collected was a reasonable sample size for a study of this scope. In addition, Haßler (2022) argued that interventions need to be affordable and cost-effective to be scalable. While assessment of the costs of scaling this intervention nationally was beyond the scope of this research, it is a critical step in moving forward with this program to ensure nationwide access to quality education.

Conclusion

Despite the challenges of conducting this study during an unprecedented period of a global pandemic, this study has shown that personalized digital education interventions can align well to a rights-based education policy, by facilitating access to and progression through the education system, especially for marginalized groups of learners. Software that offers a flexible and effective method of teaching foundational skills can benefit early grade learners, including children with SEND, to acquire foundational skills in an inclusive setting. EdTech interventions that can be adapted to local contexts, either through a range of implementation modalities and/or modes of instruction, can enhance the quality of literacy and numeracy instruction provided in primary schools, which could address differences in teacher capacity to provide high-quality literacy instruction, particularly when the language of instruction differs from the language(s) spoken at home. These technologies can also foster community engagement with the education system, encouraging children to attend, and stay in, school. Results also revealed the importance of providing teacher training in the content and pedagogy of EdTech interventions, rather than simply instruction in how to use the technology. Locally contextualized forms of technology-mediated Teacher Professional Development could be particularly effective for remote and marginalized districts (Hennessy et al., 2022). This study has highlighted the importance of a flexible approach to introducing EdTech interventions into primary schools to support the acquisition of foundational skills, which can be adapted according to contextual differences, from national to regional to community levels. Scaling EdTech interventions, such as onecourse, nationally without careful consideration of local realities and engagement of all stakeholders in the education ecosystem, could potentially result in greater exclusion and a widening of the digital divide.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Government of Sierra Leone Office of the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee, Ministry of Health and Sanitation Directorate of Policy, Planning & Information (DPPI). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Author contributions

A-FL and NP co-designed the study and materials, supervised data collection in Sierra Leone, conducted the data analyses, and edited the article. A-FL was responsible for the policy mapping, data entry from the survey and interviews, conducting the focus groups, coding the qualitative data, and conducting the thematic analysis. NP secured ethical approval, analyzed the quantitative data, wrote the article, and led the research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hempel Foundation (grant number RK2919) in an award made to VSO. The not-for-profit app developers, onebillion, donated the software free of charge to the participating schools. None of the authors have a financial interest in onebillion.

Acknowledgments

We thank the partner organizations, VSO, Save the Children, onebillion, and JP: IK, who delivered this project in Sierra Leone. We are most grateful to the children and teachers at participating schools, and the local communities where the study was based, for taking part in this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1069857/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^https://mbsse.gov.sl/fqse/

2. ^https://onebillion.org/impact/

3. ^https://onebillion.org/impact/awards/

4. ^https://www.imagineworldwide.org/updates/building-educational-foundations-through-innovation-technology-befit-malawi-scale-up-program-overview/

5. ^https://www.nationalequityproject.org/education-equity-definition

References

Acharya, K. P., and Pathak, S. (2019). Applied research in low-income countries: why and how? Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 4:3. doi: 10.3389/frma.2019.00003

Annual Schools Census Report and Statistical Abstract . (2019). Republic of Sierra Leone Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education. Available at: https://mbsse.gov.sl/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2019-Annual-School-Census-Report.pdf

Bardack, S., Lopez, C., Levesque, K., Chigeda, A., and Winiko, S. (2023). An exploratory analysis of divergent patterns in reading progression during a tablet-based literacy program. Front. Educ. 8:983349. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.983349

Barry, K.B. (2022). Impact of the digitalization of education on the right to education. Report of the special rapporteur on the right to education. Human Rights Council 15th Session.

Barton, A. (2021). Implementing education reform: is there a “secret sauce”? Dream a Dream. Available at: https://dreamadream.org/reportimplementingeducation-reform/

Coflan, C. M., and Kaye, T. (2020). Using education technology to support students with special educational needs and disabilities in low- and middle-income countries (EdTech Hub Helpdesk Response No. 4). EdTech Hub.

Education Endowment Foundation . (2019). Onebillion: App-based maths learning. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/projects-and-evaluation/projects/onebillion-app-based-maths-learning/

Fyle, C. N. (2003). “Language policy and planning for basic education in Africa” in Towards a multilingual culture of education. ed. A. Ouane (Hamburg, Germany: UNESCO Institute for Education), 113–119.

Gellman, M. (2020). “Mother tongue won’t help you eat”: language politics in Sierra Leone. Afr J. Polit. Sci. Int. Relat. 14, 140–149. doi: 10.5897/AJPSIR2020.1292

Gulliford, A., Walton, J., Allison, K., and Pitchford, N. J. (2021). A qualitative investigation of implementation of app-based maths instruction for young learners. Educ. Child Psychol. 38, 90–108. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2021.38.3.90

Haßler, B. (2022). Reaching SDG4 by 2030: characteristics of interventions that can accelerate progress in the lowest-income countries. Decision 49, 189–194. doi: 10.1007/s40622-022-00321-0

Haßler, B., Major, L., and Hennessy, S. (2016). Tablet use in schools: a critical review of the evidence for learning outcomes. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 32, 139–156. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12123

Hennessy, S., D’Angelo, S., McIntyre, N., Koomar, S., Kreimeia, A., Cao, L., et al. (2022). Technology use for teacher professional development in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Comput. Educ. 3:100080. doi: 10.1016/j.caeo.2022.100080

Hennessy, S., Jordan, K., and Wagner, D.A., EdTech Hub team (2021). Problem analysis and focus of EdTech Hub’s work: Technology in Education in low- and middle-income countries. [Working Paper 7]. EdTech Hub.

Higgins, S., and Moseley, D. (2001). Teachers' thinking about information and communications technology and learning: beliefs and outcomes. Teach. Dev. 5, 191–210. doi: 10.1080/13664530100200138

Hollow, D., and Jefferies, K. (2022). How EdTech can be used to help address the global learning crisis: A challenge to the sector for an evidence-driven future [preprint] EdTech Hub.

Hubber, P., Outhwaite, L. A., Chigeda, A., McGrath, S., Hodgen, J., and Pitchford, N. J. (2016). Should touch screen tablets be used to improve educational outcomes in primary school children in developing countries? Front. Psychol. 7:839. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00839

Imagine Worldwide . (2020). Tablet-based learning for foundational literacy and math: an 8-month RCT in Malawi. Available at: https://www.imagineworldwide.org/resource/tablet-based-learning-for-foundational-literacy-and-math-an-8-month-rct-in-malawi-executive-su

International Centre for Research on Women . (2016). A second look at the role education plays in women’s empowerment. Available at: https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/A-Second-Look-at-the-Role-Education-Plays-in-Womens-Empowerment.pdf

Kuper, H., Ashrita, S., and White, H. (2018). Rapid evidence assessment (REA) of what works to improve educational outcomes for people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. Department for International Development (DfID). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/738206/Education_Rapid_Review_full_report.pdf

Lansari, W. C. C., and Haddam Bouabdallah, F. (2022). Teacher training in the post-colonial era (from 1962 - 2000 and up). Revue Plurilingue: Études Des Langues, Littératures Et Cultures 6, 91–98. doi: 10.46325/ellic.v6i1.89

Law, N., Pelgrum, W. J., and Plomp, T. (2008). Pedagogy and ICT use in schools around the world: Findings from the IEA SITES 2006 study. Hong Kong: CERC-Springer.

Lynch, P., Singal, N., and Francis, G. A. (2022). Educational technology for learners with disabilities in primary school settings in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. Educ. Rev., 1–27. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2022.2035685

Mackintosh, A., Ramirez, A., Atherton, P., Collis, V., Mason-Sesay, M., and Bart-Williams, C. (2020). Education workforce supply and needs in Sierra Leone (Research and Policy Paper No. 3; p. 41). Education Workforce Initiative. Available at: https://educationcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/3-EW-Supply-and-Needs-Paper.pdf

Major, L., Francis, G. A., and Tsapali, M. (2021). The effectiveness of technology-supported personalised learning in low- and middle- income countries: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52, 1935–1964. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13116

Outhwaite, L. A., Faulder, M., Gulliford, A., and Pitchford, N. J. (2018). Raising early achievement in math with interactive apps: a randomized control trial. J. Educ. Psychol. 111, 284–298. doi: 10.1037/edu0000286

Outhwaite, L. A., Gulliford, A., and Pitchford, N. J. (2017). Closing the gap: efficacy of a tablet intervention to support the development of early mathematical skills in UK primary school children. Comput. Educ. 108, 43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.01.011

Outhwaite, L. A., Gulliford, A., and Pitchford, N. J. (2019). A new methodological approach for evaluating the impact of educational intervention implementation on learning outcomes. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 43, 225–242. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2019.1657081

Outhwaite, L. A., Gulliford, A., and Pitchford, N. J. (2020). Language counts when learning mathematics with interactive apps. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51, 2326–2339. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12912

Pitchford, N. J. (2015). Development of early mathematical skills with a tablet intervention: a randomized control trial in Malawi. Front. Psychol. 6:485. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00485

Pitchford, N. J. (2023). “Case study: customized e-learning platforms, Malawi” in An introduction to development engineering: a framework with applications from the field. ed. T. Madon (Cham: Springer), 269–322.

Pitchford, N. J., Chigeda, A., and Hubber, P. J. (2019). Interactive apps prevent gender discrepancies in early grade mathematics in a low-income country in sub-Sahara Africa. Dev. Sci. 22:e12864. doi: 10.1111/desc.12864

Pitchford, N. J., Gulliford, A., Outhwaite, L. A., Davitt, L. J., Katabua, E., and Essien, A. (2021). “Using interactive apps to support learning of elementary maths in multilingual contexts: implications for practice and policy” in Multilingual education yearbook 2021: Practice and policy in STEM multilingual contexts. eds. A. A. Essien and A. Msimanga (Cham: Springer)

Pitchford, N. J., Kamchedzera, E., Hubber, P. J., and Chigeda, A. (2018). Interactive apps promote learning in children with special educational needs. Front. Psychol. 9:262. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00262

Pitchford, N.J., and Lurvink, A.F. (in preparation). Impact evaluation of an EdTech intervention for raising foundational skills with early grade learners in Sierra Leone.

Pitchford, N. J., and Outhwaite, L. A. (2019). Secondary benefits to attentional processing through intervention with an interactive maths app. Front. Psychol. 10:2633. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02633

Sengeh, D., and Winthrop, R. (2022). Transforming education systems why, what, and how. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institute.

Sierra Leone 2015 National Population and Housing Census: National Analytical Report (2017). Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL). Available at: https://www.statistics.sl/index.php/census/census-2015.html

Sierra Leone 4th National Human Development Report: Building Resilience for Sustainable Development . (2019). United Nations development Programme Sierra Leone.

Sierra Leone Multidimensional Poverty Index . (2019). Statistics Sierra Leone, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, United Nations Development Programme.

Sierra Leone Population and Housing Census (2015). Statistics Sierra Leone, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Sierra Leone.

The Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education . (2021a). Transforming education service delivery through evidence-informed policy and practice. Freetown: MBSSE.

The Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education . (2021b). National Policy on radical inclusion in schools. Freetown: MBSSE.