- 1Department of Linguistics, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Department of Modern Languages, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

This study adopts a multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging perspective to explore the relationship between beliefs and actual linguistic practices concerning multilingual and multidialectal practices among L2 Arabic teachers in Islamic independent schools in Sydney, NSW, Australia. To this end, the study draws on class observations and individual interviews. The findings show a clear mismatch between teachers’ beliefs about the use of English and their actual employment of it in the classroom. The majority of the teachers indicated that English should be either limited or totally avoided in the L2 Arabic classroom, but class observations showed that (a) English was utilized in all 11 classes, and (b) it was used significantly more than Arabic in nine of these classes. As for multidialectal practices, although most of the teachers believed that the use of non-standard varieties along with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) should be limited, findings were inconclusive due to the fact that English was found to be the main medium of communication in the majority of the observed classes. Therefore, the study underscores the need for providing teacher training that demonstrates how to purposefully deploy multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging to help learners enrich their linguistic repertoire in their desired L2.

Introduction

A great deal of research in applied linguistics has recently focused on bringing multilingualism to the forefront to underscore the fluidity of language boundaries and challenge monolingual ideologies in second/additional language (L2) learning contexts (e.g., Otheguy et al., 2015; MacSwan, 2017, 2022; Wei, 2018; Leung and Valdés, 2019; Al Masaeed, 2020). Nevertheless, while multilingual practices have been widely researched in the L2 classroom and research on teachers’ use of L1 in L2 contexts demonstrated that there is usually a discrepancy between recommendations/beliefs and actual practices on the ground (e.g., Polio and Duff, 1994; Macaro, 2001, 2005, 2009; Turnbull, 2001; Rolin-Ianziti and Brownlie, 2002; Liu et al., 2004; De la Campa and Nassaji, 2009; Littlewood and Yu, 2011; Al Masaeed, 2016, 2020), less attention has been devoted to exploring multilingual and multidialectal practices by instructors in less commonly taught language learning contexts.

For example, one of the main challenges encountered by teachers and learners of Arabic is the diglossic nature of the language, where two varieties of the language are used side-by-side in Arabic-speaking communities, serving different functions (Ferguson, 1959; Holes, 2004; Nassif and Al Masaeed, 2022). Consequently, teaching and learning Arabic as an additional language presents linguistic and pedagogical challenges. In light of the recent calls for the multilingual turn in applied linguistics and for bringing multidialectal practices to the center of L2 Arabic (Al-Batal, 2018; Al Masaeed, 2022a,b; Nassif and Al Masaeed, 2022), the primary purpose of the present study is to investigate the (mis)alignment between teachers’ beliefs and actual practices concerning the use of multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging in L2 Arabic classes in Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Translanguaging in L2 contexts

A considerable amount of research in L2 learning contexts has demonstrated the advantages of bi/multilingual practices for enriching learning (e.g., Turnbull and Dailey-O’Cain(eds), 2009; DiCamilla and Antón, 2012; Cheng, 2013; May(ed.), 2014; Sali, 2014; Levine, 2015; Sert, 2015; van Compernolle, 2015; Al Masaeed, 2018, 2020, 2022c; Larsen-Freeman, 2018). May(ed.)’s (2014) edited volume, for example, convincingly criticized monolingual ideologies in second language acquisition (SLA) and highlights multilingual practices as the norm of our modern era.

Therefore, the term translanguaging has gained significant support to highlight the ways in which bilingual and multilingual practices can be used for the purpose of meaning-making and for challenging monolingual ideologies in bilingual education and L2 contexts (e.g., García, 2009; Turner and Lin, 2017; Al Masaeed, 2020). However, translanguaging is a relatively recent development in the field, with a strong but sometimes controversial relationship to code-switching. Code-switching and translanguaging are both multilingual phenomena occurring in multilingual societies and L2 contexts. While some traditions see code-switching as a sub-component of translanguaging, others do not. Both have potential functions in multilingual classrooms through the use of two or more languages or language varieties. Translanguaging refers to the multilingual practices that both learners and teachers deploy to “engage in complex and fluid discursive practices that include, at times, the home language practices of students in order to make sense of teaching and learning, to communicate and appropriate subject knowledge, and to develop academic language practices” (García and Wei, 2014, p 112).

Moreover, the term translanguaging is multifaceted and has been conceptualized and used by researchers and practitioners in various ways. For example, two main models of translanguaging have been proposed to explain the cognitive processing of language and how multilingualism functions. These models are the unitary and the integrated models of translanguaging. The unitary model argues that “bilingualism and multilingualism, despite their importance as sociocultural concepts, have no correspondence in a dual or multiple linguistic system” (Otheguy et al., 2019, p. 625). According to this model, code-switching is a separate phenomenon from translanguaging because it considers code-switching as a dual competence model based on two separate linguistic systems (Otheguy et al., 2015). In other words, some of the leading scholars mentioned above (namely, Garcia, Wei, and Otheguy) have adopted a deconstructivist proposal that rejects the existence of named languages and, by extension, questions the psychological reality of bilingualism (see García et al., 2021, for details).

On the other hand, the integrated model assumes that the internal linguistic system of the individual is structured with separate lexical systems for each language and overlapping grammatical systems which share language components including phonetic, morphological and phonological features (MacSwan, 2017). This model considers code-switching as part of translanguaging, presupposing a distinction between the cognitive linguistic systems. More recently, MacSwan (2022) edited a thought-provoking volume that takes on a multilingual perspective on translanguaging to reject the deconstructivist thesis that does not acknowledge the existence of named languages or discrete language communities. This perspective accepts “language diversity as psycholinguistically real and socially significant, drawing on empirically informed theories of language and society to challenge prevailing language ideologies which oppress and disadvantage linguistically diverse communities” (p. 31).

Because of such various understandings of the term, Leung and Valdés (2019) argue that translanguaging is “still evolving and deepening as a stance, a theory, and a pedagogy” (p. 358). In this study, similar to MacSwan (2022), we adopt a translanguaging perspective that acknowledges the existence of named languages and varieties as part of the social (i.e., external) perspective when analyzing speakers’ utilization of bilingual and multidialectal practices in L2 contexts. This linguistic fluidity does not disregard multilingual speakers’ awareness of linguistic and ideological boundaries, but rather acknowledges their ability to strategically and creatively exploit and manipulate the linguistic resources they have at their disposal for engaging in productive and meaningful interactions. Consequently, translanguaging practices in the L2 classroom should be strategically and purposefully employed to support and enrich learners’ desire to expand their linguistic repertoire in the named L2 (Al Masaeed, 2020). In this vein, the teacher’s role is to support and model linguistic fluidity to help learners internalize, understand, and produce the desired named language so it remains the general means of communication in the L2 classroom. Additionally, adopting a multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging perspective empowers us to advocate for learners of diverse linguistic backgrounds.

Multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging in L2 Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) functions as a standard written language and is considered as the official language of Arab countries. MSA is considered a symbol of unity and nationalism among Arabic-speaking people regardless of their religious faiths. However, in addition to MSA, Arabic is a multidialectal language with different national language varieties, each with its own set of linguistic rules (Ferguson, 1959; Holes, 2004; Al-Batal, 2018; Al Masaeed, 2020, 2022a,b; Nassif and Al Masaeed, 2022). Drawing on empirical research, scholars have increasingly characterized the sociolinguistic situation in the Arab world as a continuum of spoken and written varieties with multiple registers (Holes, 2004; Mejdell, 2011; Younes, 2015). Therefore, while this makes the process of teaching and learning Arabic linguistically and pedagogically challenging, it positions it as an interesting context that is better be explored through a translanguaging standpoint.

A recent line of empirical research in Arabic has demonstrated that learners value the opportunity to learn and use multidialectal practices (e.g., Abdalla and Al-Batal, 2012; Al-Batal, 2018; Isleem, 2018; Zaky and Palmer, 2018; Al Masaeed, 2020; Nassif and Al Masaeed, 2022). However, studies on multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging in L2 Arabic contexts are still scarce. A small number of studies have investigated this matter in the Arabic language context (e.g., Al-Bataineh and Gallagher, 2018; Al Masaeed, 2020, 2022a). Al-Bataineh and Gallagher (2018) conducted a study in the United Arab Emirates to investigate the attitudes of future teachers toward translanguaging when writing stories for young bilingual learners and to identify the variables that shaped their attitudes. The participants were asked to write a storybook of a fictional character’s experience using MSA and English, and Emirati dialect as required. They found that the participants held highly inconsistent and uncertain attitudes toward translanguaging which they concluded were influenced greatly by language ideology. However, many participants did regard translanguaging as a positive learning practice. Moreover, many believed that it made reading translingual stories more interesting than the monolingual one.

Al Masaeed (2020, 2022a) studies on L2 Arabic during study abroad in Morocco and Jordan, respectively, demonstrate the need for the field of L2 Arabic to move beyond the MSA-only language ideology to support learners’ sociolinguistic and pragmatic competence development. For example, his study in Morocco (Al Masaeed, 2020) examined multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging practices among 10 learners (native speakers of English) and eight speaking partners during a summer program in Morocco. The participants were required to do four dyadic conversation sessions a week. The author examined recordings of speaking sessions that were supposed to be in MSA only. He concluded that despite the MSA-only policy, the participants used multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging as valuable resources for achieving and maintaining intersubjectivity throughout their interactions. The results also showed that alternations between MSA and non-MSA varieties were more frequent than switches between Arabic and English. He also concluded that French, while present, was the least utilized language in the examined conversations. In a more recent study, Al Masaeed (2022a) investigated the role of bidialectal practices during study abroad in Jordan on learners’ pragmatic development. He employed a spoken discourse completion task to collect pre-and post-program speech acts production. His findings demonstrated that the ability to use bidialectal practices was a clear indication of learners’ pragmatic development.

The synthesis of L2 Arabic research illuminates the following key points: (1) learners are interested in learning at least one spoken variety of Arabic alongside MSA, (2) multidialectal multilingual translanguaging practices mirror the sociolinguistic reality of Arabic speakers, and (3) multidialectal practices contribute to developing pragmatic competence. Based on these empirical insights, one can argue that L2 Arabic teachers should encourage and engage in multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging practices to help learners internalize, understand, and produce the desired L2. Previous research on teachers’ use of L1 in L2 contexts demonstrated that there is usually a discrepancy between recommendations/beliefs and actual practices on the ground (e.g., Turnbull and Arnett, 2002; Kim and Elder, 2005; Macaro, 2009; Copland and Neokleous, 2011; Sali, 2014). However, what seems to be still lacking is research on teachers’ use of multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging practices in less commonly taught languages such as Arabic. Therefore, the current study draws on data from classroom observations and individual interviews to explore whether L2 Arabic teachers’ beliefs about translanguaging practices (mis)align with their actual linguistic practices in the classroom.

Materials and methods

This study is a part of larger project on teachers’ language learning and teaching beliefs and practices in Australia. In this section we present information about participants and context, as well as data analysis.

Participants and context

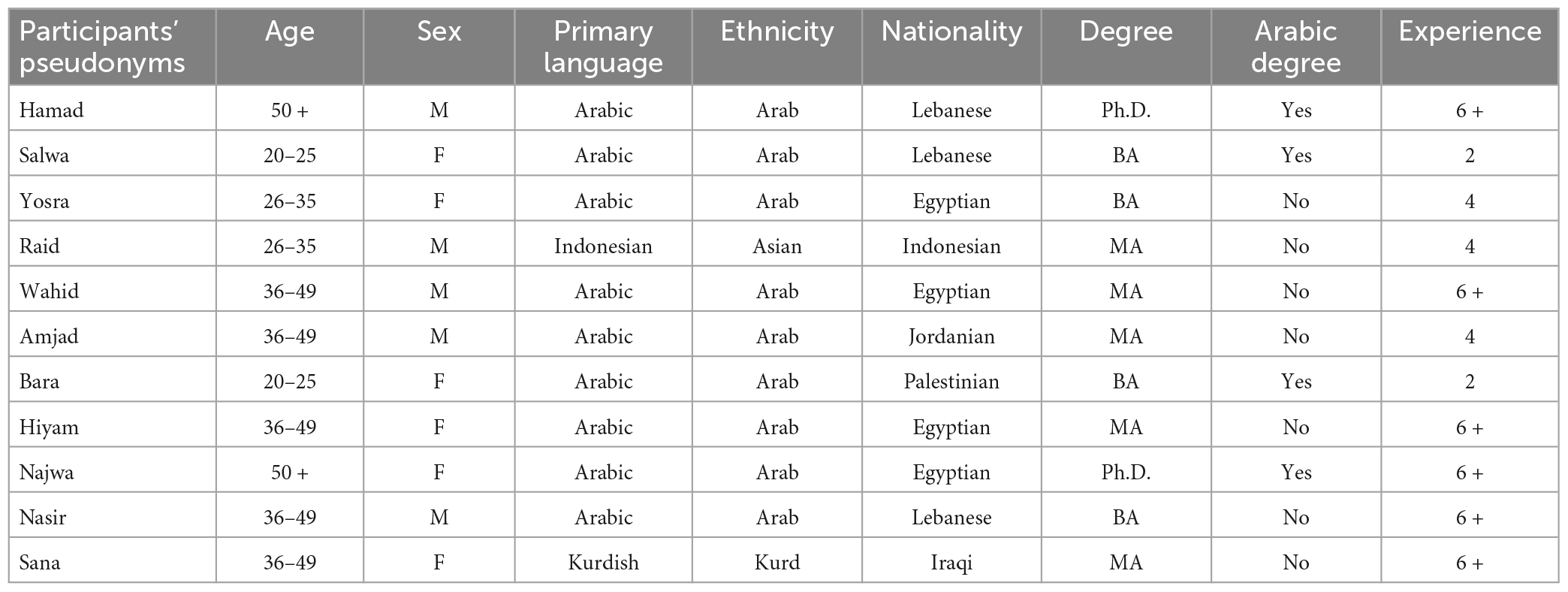

The current study participants were 11 L2 Arabic teachers from a number of three Islamic independent schools in Sydney, NSW, Australia. They were all volunteer participants who were recruited and consented in accordance with Institutional Review Board regulations. Teachers’ background and demographic information is presented in Table 1 below. The independent school system is similar to the mainstream public-school system in terms of the taught curriculum and the objectives derived from the New South Wales (NSW) Bord of Studies (BOS) syllabus for languages other than English. According to the Board of Studies NSW (2009), the current syllabus content is consistent with a communicative focus, with the integration of the four core language skills: listening, reading, speaking and writing within the cultural context of Arabic-speaking communities. For individual teachers, there is still a considerable degree of autonomy in classroom decision-making including task selection and decisions about which language and language varieties are most appropriate for classroom use.

However, the syllabus lacks explicit methods and provides minimal teaching guidelines (Liddicoat et al., 2007; Cruickshank, 2008). Moreover, in independent Islamic schools, English is used as the medium for instruction across all areas of the curriculum, whereas Arabic is specifically taught as a single subject. Arabic is taught as a required subject mainly in primary schools and up to Stage 4 (years 7–8) or Stage 5 (years 9–10) in some high schools, depending on the school. It is also offered as an elective subject at Stage six (years 11 and 12) in some high schools.

Data collection and analysis

Data were obtained over 9 months from 11 L2 Arabic class sessions ranging from first to tenth grade with an average number of 25 students in each classroom. In addition to the demographic information that was collected through a background survey, data for the study were gathered through classroom observations and individual interviews to explore whether L2 Arabic teachers’ beliefs about bilingual and multidialectal practices (mis)align with their actual linguistic practices on the ground. Each teacher was observed once in their classrooms for a period of 40–50 min; and following classroom observations, individual semi-structured interviews were conducted. Both classroom observations and interviews were audio-recorded.

Classroom observations data were analyzed as follows. The teachers’ language use in the classroom was transcribed and read carefully. Next, the total number of words spoken by each teacher in their observed class were calculated, and multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging practices were categorized and tagged with codes. Then, instances of multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging (i.e., MSA, non-MSA, and English) were grouped into their relevant categories, and frequency of occurrence were tallied. But when it comes to Arabic in particular, each word, collocation, and structure was analyzed and categorized as MSA or spoken using linguistic categories in line with previous L1 and L2 Arabic studies (e.g., Alaiyed, 2018; Nassif and Al Masaeed, 2022). For example, we took into account internal word voweling for words that are shared between MSA and spoken Arabic (e.g., the word for “book” could be ktaab or kitaab—the second only is considered MSA; the verb “I like” is considered MSA if it is uḥib, but spoken Arabic if pronounced as baḥib as in Jordanian and Egyptian Arabic). MSA mood and case ending markers on word ends were not considered because these markers are usually dropped by Arabic speakers (Alaiyed, 2018). After that, following Rolin-Ianziti and Brownlie (2002), functions for translanguaging practices were identified.

Analysis of the individual interview responses was conducted as follows: the teachers’ interview responses were audio-recorded, transcribed, and then read and reread carefully until they became very familiar. Next, all statements relating to the research focus were identified, and each was assigned a code, or category. These codes were then recorded and each relevant statement was put under its appropriate code (open coding). Then, in a process of categorical aggregation (Creswell, 2007), the most relevant themes were grouped together under main categories (axial coding). The most relevant, similar and common concepts and categories were then organized into a data table. After that, the most common, interesting, frequent and relevant themes to the research focus were chosen as the main themes to emerge from the interview data. In so doing, the main related themes addressed by most teachers included the use of English and non-MSA varieties alongside MSA. Consequently, individual teacher instances of multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging practices were compared to their stated beliefs in the interviews.

Findings

In this section, we present the findings of whether teachers’ beliefs about multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging practices (as obtained in the interviews) align with their actual practices on the ground (as obtained from class observations). The findings reveal that there is some mismatch between teachers’ beliefs about multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging practices and their actual linguistic practices in the classroom and point to some frequent functions of multidialectal and multilingual practices. Below we present the findings in the following order: (a) teachers’ beliefs vs. multilingual practices (i.e., the use of English alongside Arabic), and (b) teachers’ beliefs vs. multidialectal practices (i.e., the use of MSA and non-MSA spoken varieties).

Teachers’ beliefs vs. multilingual translanguaging practices

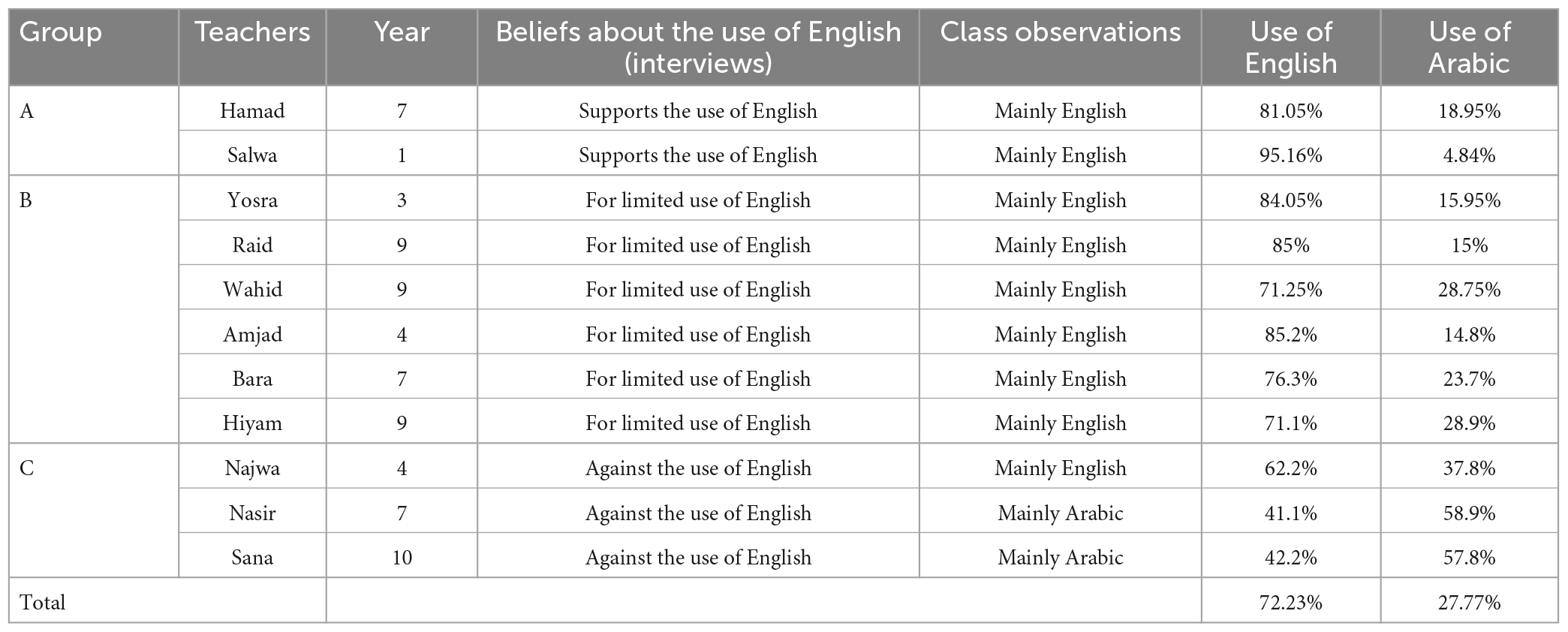

Findings show that instructors’ beliefs about multilingual translanguaging practices (mainly the use of English alongside Arabic) varied to include support for its use as a primary resource as it is the students’ L1; support for its use for specific purposes to facilitate communication; and a total opposition to its use because it slows learners’ L2 progress. Hamad and Salwa, for example, are advocates for the unlimited use of English as a resource for L2 learning. This is because they have a large number of students who come from non-Arabic speaking backgrounds in their classes and because it is the language that learners are more comfortable and familiar with.

But the majority of teachers advocate for using English for specific purposes in the classroom. Bara, for example, believes that a limited amount of English is needed mainly with students of lower proficiency levels for giving instructions and explaining the task at hand. She commented, “I prefer Arabic, but I don’t apply [it] all the time because it’s hard sometimes, especially for lower levels. It’s hard to speak only in Arabic with them specially if you are explaining a task.” Three teachers (Najwa, Nasir, and Sana) are totally against the use of English in the classroom because it negatively impacts learners’ progress in Arabic. Najwa, for example, believes that Arabic should be taught through the use of Arabic only. She stated in the interview that, “it is easier for them to read English than Arabic and they will rely on English to understand Arabic. I want them to focus on Arabic because when they have the English they won’t put effort to read the Arabic.”

However, classroom observations of teachers’ actual linguistic practices reveal substantial use of English in the classroom. In fact, as can be seen in Table 2 below, while all teachers were found to employ English in their classroom talk, most of them (9 of 11) employed English more than Arabic. Furthermore, all of those who supported the limited use of English did end up using it more than Arabic; and while all teachers who were against it ended up using it frequently, one of them (Najwa) was found to use it more than Arabic.

Table 2. Teacher beliefs about the use of English in the L2 Arabic classroom and their actual linguistic practices (interviews vs. classroom observations).

In addition to information provided in Table 2 above, examples 1–3 below are extracted from class observations of the three teachers who stated their opposition to the use of English alongside Arabic in the classroom. In all examples in this section, MSA is in default font, non-MSA is underlined, and English is in bold. Translation is provided in italics on a separate line when needed. Furthermore, transliteration conventions used in this article are adopted from Alhawary (2018) (please see Supplementary Appendix A).

(1) Najwa (class focus was on teaching writing and grammar):

| Najwa: | Everyone got a ḥarf. What’s the meaning of ḥarf? | |

| Students: | letter | |

| Najwa: | Ok, I want this ḥarf, I want also a word. | |

| What’s the meaning of word? | ||

| Students: | kalimah. |

(2) Nasir (class focus was on reading, listening, and writing):

| Nasir: | nuriidu laḥman! Excellent group number 1 | |||

| We want meat | ||||

| Ok, group number 2, we want chicken | ||||

| Students: | nuriidu dajaajan. | |||

(3) Sana (class focus is on reading comprehension):

| Sana: | village, town il-qariyya, madiina, village. | |||

| Student: | Miss, city madiina? | |||

| Sana: | yeah nafs ʔišii | |||

| same thing | ||||

| Student: | and the town? | |||

| Sana: | il-town if you said countryside, bitkuun | |||

| qariyya, village | ||||

| the- it would be | ||||

| Student: | Miss is madiina city? | |||

| Sana: | city. | |||

These examples are representative of teachers’ talk in the classroom, and provide an idea of the frequency and some common functions (e.g., asking questions, classroom management, explaining and clarifying vocabulary, etc.) of deploying English in class. They also point to the misalignment between teachers’ language beliefs and their actual practices.

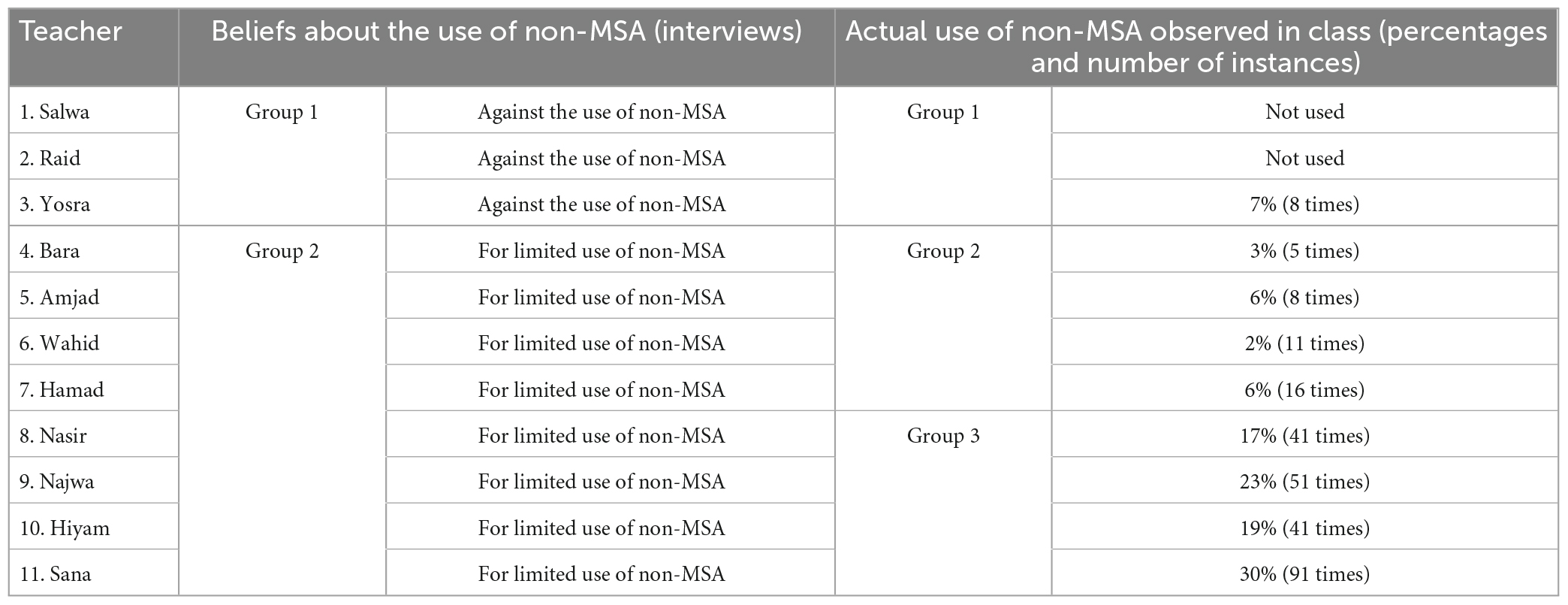

Teachers’ beliefs vs. multidialectal translanguaging practices

Findings regarding multidialectal translanguaging practices [i.e., the use of spoken varieties alongside MSA reveal that the majority of instructors (8/11)] supported the limited use of non-MSA spoken varieties alongside MSA for specific purposes (e.g., encouraging students, asking questions, giving instructions, etc.), but 3/11 were in opposition to utilizing any non-MSA varieties. Those who were in favor of a judicious use of multidialectal practices believe that such practices would support students’ home language, enhance cultural connections, and maximize participation. The three teachers who were against the use of non-MSA believe that such practices are different from what is in the textbook and can be confusing and challenging for students who come from non-Arabic speaking backgrounds. Only one of these three teachers (Yosra) was found to use non-MSA eight times in the little amount of Arabic (15.95%) she used in class time. The other two were found to be consistent.

However, classroom observations reveal that teachers’ actual linguistic practices fell into three categories: (a) teachers who didn’t use non-MSA at all, (b) those who employed it occasionally (less than 10%), and (c) those who used it more frequently (more than 10%) (as Table 3 below shows). An interesting finding is that the two teachers who used English the least (Najwah and Sana) were found to use multidialectal practices the most; and those who deployed multilingual practices the most (Salwa and Raid) did not use multidialectal practices at all.

Table 3. Teachers’ beliefs about the use of non-MSA in the L2 Arabic classroom and their actual linguistic practices (interviews vs. classroom observations).

Examples 4–6 below are extracted from class observations of the three teachers who used non-MSA the most alongside MSA in the classroom.

(4) Sana (class focus is on reading comprehension):

| šuu binsammii theater ʕbilarabiiḥ | |

| What do we call theater in Arabic? | |

| What do we call in Arabic? | |

| maaðaa nusammii al theater bilʕarabii? | |

| What do we call the. |

(5) Najwa (class focus was on teaching writing and grammar):

šuuf! Yasmin ind-haa ḥarf wa ḥaṭṭit-haa wa ḥaṭṭit-haa |

||||||

| fi kilmit faraašah | ||||||

| Look! Yasmine has the letter “F” and she used it | ||||||

| in the word butterfly | ||||||

| wa ḥatiʕmal sentence. | ||||||

| And she’ll make a. |

(6) Hiyam (class focus was on reading comprehension):

| Hiyam: | Yeah, alright Tahir, mumkin tikammil? | |

| Can you continue? | ||

| Tahir: | (reads the part the teacher asked him to read) | |

| Hiyam: | Yeah alright, maazaa fahamt? | |

| What did you understand? | ||

| Tahir: | kaan ʕam bištaγil | |

| He was working | ||

| Hiyam: | ʕam bištaγil! maa fiiš ḥaagah ʔismahaa | |

| ʕam bištaγil | ||

| there isn’t such a thing as | ||

| kaan al-fataa… (asking Tahir to read the answer | ||

| from the book in MSA). | ||

| The boy was… |

Similar to the use of English, the employment of non-MSA is found to serve various functions in the data including (but not limited to) asking questions (as in example 4), offering an explanation (as in example 5), or providing comments on students’ answers/work to evaluate their performance (as in example 6) (see Supplementary Appendix B for a complete list and frequency of the functions both multilingual and multidialectal practices serve in the current study). However, example 6 is of special interest and merits more attention. Hiyam asked the student (in Egyptian Arabic) to start reading and when he was done, she asked him about what he understood from the text he has just read. The student answered in Lebanese Arabic, but Hiyam repeated the student’s answer using Lebanese Arabic and then commented (in Egyptian Arabic) to evaluate the student’s answer. Next, the student read the answer from the book in MSA. What is interesting in this exchange is the teacher’s criticism of the student’s use of non-MSA in spite of her own employment of multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging practices in both her request and evaluation of his answer. This is a clear example of the misalignment between teachers’ beliefs and their actual linguistic practices regarding multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging practices.

Discussion

This study set out to examine language beliefs and actual linguistic practices among L2 Arabic teachers in Islamic independent schools in Sydney, NSW, Australia. To this end, we utilized class observations and individual interviews to explore whether L2 Arabic teachers’ beliefs about the use of multilingual and multidialectal practices align with their actual linguistic practices in the classroom. Findings are summarized and discussed accordingly.

Our findings indicated a clear mismatch between teachers’ beliefs about the use of English and their actual employment of it in the classroom. While the majority of the teachers (9 of 11) in the interviews believed that English should be either limited or totally avoided in their teaching, classroom observations showed that English was not only used in all classes, but it was also utilized more than Arabic in 9 of 11 classes. When asked about this point in particular (the high amount of English used by those teachers) during the interviews that came after class observations, most teachers attributed the use of English to students’ proficiency levels and preference for using English over MSA. This finding shows that the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and linguistic practices concerning multilingual practices is complex, and that teachers are not always aware of the discrepancies. This is consistent with previous studies regarding the use of L1 in L2 contexts (e.g., Macaro, 2009; Copland and Neokleous, 2011; McMillan and Rivers, 2011; Sali, 2014). However, the current finding is at odds with results from many studies that found that teachers tend to use L1 in lower amounts on average (e.g., Polio and Duff, 1994; Macaro, 2001, 2005; Rolin-Ianziti and Brownlie, 2002; Turnbull and Arnett, 2002; De la Campa and Nassaji, 2009).

Nevertheless, although the findings regarding multilingual practices above can be interpreted as evidence of the misalignment between teachers’ language beliefs and their actual linguistic practices on the ground, our finding regarding teachers’ beliefs about the employment of non-MSA varieties alongside MSA and their actual linguistic practices in the classroom were inconclusive. While multidialectal practices in the classroom are supported to a limited degree and utilized infrequently by the majority of the teachers, it was difficult to provide a clear-cut conclusion on this matter because English is found to be the main medium of communication in the majority of the class.

Therefore, we argue that the amount of English utilized in the current study is quite concerning because it seems that it is given more precedence over multidialectal practices (both MSA and non-MSA) that can better support learners’ motivation to engage in conversations that mirror the sociolinguistic situation in the Arabic speaking world, and bolster their understanding of the cultural nuances of the language. In other words, the employment of English this much seems to defeat the purpose of strategic and purposeful use of bi/multilingual translanguaging to support the desired named language (i.e., Arabic). This brings to mind one of the important questions that Leung and Valdés (2019, p. 365) raise for us to bear in mind as we continue to work toward refining what translanguaging as a pedagogical stance exactly means in the L2 classroom: how does a translanguaging classroom address the pedagogic issues connected to the development of language-specific proficiency and use for learning purposes?

Multidialectal translanguaging responds to learners’ needs and has a crucial role in developing their pragmatic competence to connect with the Arabic speaking world and its cultures (e.g., Al-Batal and Belnap, 2006; Younes, 2015; Al Masaeed, 2020, 2022b,c). Therefore, focus should be on Arabic as one language (Al-Batal, 2018); that is, both MSA and non-MSA should be brought to the forefront in the classroom through teachers modeling such practices to support learners. Example 6 above has an important implication. Students can read a text in MSA and then use multidialectal practices to discuss it and answer questions about its details (which is what was really happening till the teacher objected to the student’s use of non-MSA). Adopting a multidialectal perspective in the classroom would increase participation, validate learners’ linguistic backgrounds, and eventually make learning more meaningful for students.

Multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging mirrors the sociolinguistic reality of the modern world and can be utilized to maximize learners’ understanding and enhance their language learning if used strategically and purposefully (Macaro, 2005; Al Masaeed, 2016, 2020). Our findings have shown that most teachers are not aware of how often they deploy multilingual and multidialectal practices to boost L2 learning (Macaro, 2005; Littlewood and Yu, 2011; Zhu and Vanek, 2015). These practices can act as a continuum, complementing each other and available for teachers to utilize according to the specifics of the context and the students to maximize learning outcomes. Therefore, the findings of this study point to the need for demonstrating the gap between beliefs and practices concerning our linguistic practices in L2 learning contexts, and to the need for providing teachers with training opportunities that focus on enhancing and critically evaluating their multilingual and multidialectal practices. Such opportunities are unfortunately lacking, which is a disservice to the field. Moreover, the findings of this study underscore the importance of adopting a multilingual translanguaging approach that acknowledges named languages (Al Masaeed, 2020) and the psycholinguistic reality of bilinguals to be able to challenge language ideology and advocate for learners in L2 learning contexts.

For multidialectal practices in particular, an integrated approach that sees value in teaching spoken varieties alongside MSA (Younes, 2015; Al-Batal, 2018) is in order, which means that independent schools need to re-examine the NSW BOS syllabus to better address the diglossic nature of Arabic. Program coordinators and policymakers should remedy this problem to help teachers (1) become more aware of the standard language ideology to see the benefits of multidialectal practices, and (2) develop a clear sense of when and how they should engage in multilingual and multidialectal practices in the classroom to mirror sociolinguistic practices of Arabic speakers and meet the goals of the learners. This can be tackled by providing training workshops through which Arabic teachers get access to video-taped classroom interactions that clearly show how translanguaging is utilized. This will include both types of practices: those that support language learning and meaning-making, and those that impede the learning process.

Finally, we would like to emphasize that it is clear that more research on multidialectal practices in particular is needed. We hope that future research will build on the methods and findings in this study to explore the issue of multidialectal practices in the L2 Arabic classroom through examining beliefs and practices by both teachers and learners. Some of the limitations of the current study, for example, include obtaining only one class session form each teacher and, to a certain degree, the lack of video-recordings. The use of video-recordings in particular would offer more insights into actual practices as it can capture both linguistic and other various semiotic resources that participants utilize in their classroom interactions.

Conclusion

This study utilized class observations and individual interviews to explore the relationship between beliefs and actual linguistic practices concerning multilingual and multidialectal practices among teachers of L2 Arabic in Islamic independent schools in Sydney, NSW, Australia. Findings showed a clear mismatch between teachers’ beliefs about the use of English and their actual employment of it in the classroom. The majority of the teachers indicated that English should be either limited or totally avoided in the L2 Arabic classroom, but class observations showed that (a) English was utilized in all 11 classes, and (b) it was used more than Arabic in 9 of these 11 classes. Moreover, since English was found to be the main medium of communication in the majority of the class, multidialectal translanguaging was found to be rather limited. Based on these findings, the study emphasizes the need for adopting a multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging perspective that draws on empirical sociolinguistic insights to (1) enhance language education, and (2) offer teacher training that demonstrates how to purposefully and strategically deploy multilingual and multidialectal translanguaging to help learners enrich their linguistic repertoire in the desired L2.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

HK collected the data. Both authors worked together on writing and analyzing the data and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer LN declared a past co-authorship with the author KA to the handling editor.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1060196/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdalla, M., and Al-Batal, M. (2012). “College-level teachers of Arabic in the United States: A survey of their professional and institutional profiles and attitudes,” in Al-’Arabiyya, Vol. 44, ed. R. Bassiouney (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 1–28.

Al Masaeed, K. (2016). Judicious use of L1 in L2 Arabic speaking practice sessions. Foreign Lang. Ann. 49, 716–728. doi: 10.1111/flan.12223

Al Masaeed, K. (2018). “Code-switching in L2 Arabic collaborative dyadic interactions,” in The Routledge handbook of Arabic second language acquisition, ed. M. Alhawary (New York, NY: Routledge), 289–302. doi: 10.4324/9781315674261-15

Al Masaeed, K. (2020). Translanguaging practices in L2 Arabic study abroad: Beyond monolingual ideologies in institutional talk. Mod. Lang. J. 104, 250–266. doi: 10.1111/modl.12623

Al Masaeed, K. (2022a). Bidialectal practices and L2 Arabic pragmatic development in a short-term study abroad. Appl. Linguist. 43, 88–114. doi: 10.1093/applin/amab013

Al Masaeed, K. (2022b). “Sociolinguistic research vs. language ideology in L2 Arabic,” in The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and sociolinguistics, ed. K. Geeslin (New York, NY: Routledge), 359–370. doi: 10.4324/9781003017325-33

Al Masaeed, K. (2022c). “Researching and measuring L2 pragmatic development in study abroad: Insights from Arabic.” in Designing second language study abroad research: Critical reflections on methods and data, eds J. McGregor and J. Plews (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 155–170.

Alaiyed, M. A. S. (2018). Diglossic code-switching between standard Arabic and Najdi Arabic in religious discourse. Ph.D. thesis. Durham: Durham University.

Al-Bataineh, A., and Gallagher, K. (2018). Attitudes towards translanguaging: How future teachers perceive the meshing of Arabic and English in children’s storybooks. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 24, 386–400. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1471039

Al-Batal, M., and Belnap, R. K. (2006). “The teaching and learning of Arabic in the United States: Realities, needs, and future directions,” in Handbook for Arabic language teaching professionals in the 21st century, eds K. Wahba, Z. A. Taha, and L. England (Oxfordshire: Routledge), 389–399.

Al-Batal, M. (ed.) (2018). Arabic as one language: Integrating Ddalect in the Arabic language curriculum. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1fj85jd

Alhawary, M. (ed.) (2018). The Routledge handbook of Arabic second language acquisition. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315674261

Board of Studies NSW (2009). Arabic Continuers Stage 6 Syllabus. Sydney, NSW: Board of studies NSW. Available online at: https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/key-learning-areas/languages/stage-6/arabic/continuers/arabic-continuers-st6-syl-from2010.pdf

Cheng, T. (2013). Codeswitching and participant orientations in a Chinese as a foreign language classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 97, 869–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12046.x

Copland, F., and Neokleous, G. (2011). L1 to teach L2: Complexities and contradictions. ELT J. 65, 270–280. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccq047

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cruickshank, K. (2008). “Arabic-English bilingualism in Australia,” in Encyclopedia of language and education, 2nd Edn, Vol. 5, eds J. Cummins and N. H. Hornberger (Berlin: Springer).

De la Campa, J. C., and Nassaji, H. (2009). The amount, purpose, and reasons for using L1 in L2 classrooms. Foreign Lang. Ann. 42, 742–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2009.01052.x

DiCamilla, F. J., and Antón, M. (2012). Functions of L1 in the collaborative interaction of beginning and advanced second language learners. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 22, 160–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-4192.2011.00302.x

García, O., Flores, N., Seltzer, K., Li Wei, Otheguy, R., and Rosa, J. (2021). Rejecting abyssal thinking in the language and education of racialized bilinguals: A manifesto. Crit. Inq. Lang. Stud. 18, 203–228. doi: 10.1080/15427587.2021.1935957

García, O., and Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137385765

Holes, C. (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, functions and varieties. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Isleem, M. (2018). “Integrating colloquial Arabic in the classroom: A study of students’ and teachers’ attitudes and effects,” in Arabic as one language: Integrating dialect in the Arabic language curriculum, ed. M. Al-Batal (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 237–259. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1fj85jd.17

Kim, S. H., and Elder, C. (2005). Language choices and pedagogic functions in the foreign language classroom: A cross-linguistic functional analysis of teacher talk. Lang. Teach. Res. 9, 355–380. doi: 10.1191/1362168805lr173oa

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2018). Looking ahead: Future directions in, and future research into, second language acquisition. Foreign Lang. Ann. 51, 55–72. doi: 10.1111/flan.12314

Leung, C., and Valdés, G. (2019). Translanguaging and the transdisciplinary framework for language teaching and learning in a multilingual world. Mod. Lang. J. 103, 348–370. doi: 10.1111/modl.12568

Levine, G. S. (2015). “A nexus analysis of code choice during study abroad and implications for language pedagogy,” in Multilingual education: Between language learning and translanguaging, eds J. Cenoz and D. Gorter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 84–109. doi: 10.1017/9781009024655.006

Liddicoat, A. J., Scarino, A., Curnow, T. J., Kohler, M., Scrimgeour, A., and Morgan, A.-M. (2007). An investigation of the state and nature of languages in Australian schools. Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training.

Littlewood, W., and Yu, B. (2011). First language and target language in the foreign language classroom. Lang. Teach. 44, 64–77. doi: 10.1017/S0261444809990310

Liu, D., Ahn, G.-S., Baek, K.-S., and Han, N.-O. (2004). South Korean high school English teachers’ code switching: Questions and challenges in the drive for maximal use of English in teaching. TESOL Q. 38, 605–638. doi: 10.2307/3588282

Macaro, E. (2001). Analysing student teachers’ codeswitching in foreign language classrooms: Theories and decision making. Mod. Lang. J. 85, 531–548. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00124

Macaro, E. (2005). “Codeswitching in the L2 classroom: A communication and learning strategy,” in Non-native language teachers: Perceptions, challenges and contributions to the profession, ed. E. Llurda (Boston, MA: Springer), 63–84. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24565-0_5

Macaro, E. (2009). “Teacher use of codeswitching in the second language classroom,” in First language use in second and foreign language learning, eds M. Turnbull and J. Dailey-O’Cain (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters). doi: 10.21832/9781847691972-005

MacSwan, J. (2017). A multilingual perspective on translanguaging. Am. Educ. Res. J. 54, 167–201. doi: 10.3102/0002831216683935

MacSwan, J. (2022). Multilingual perspectives on translanguaging. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/MACSWA5683

May, S. (ed.) (2014). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

McMillan, B. A., and Rivers, D. J. (2011). The practice of policy: Teacher attitudes toward English only. System 39, 251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.04.011

Mejdell, G. (2011). Diglossia, code switching; style variation; and congruence: Notions for analyzing mixed Arabic. Al Arabiyya 44, 29–39.

Nassif, L., and Al Masaeed, K. (2022). Supporting the sociolinguistic repertoire of emergent diglossic speakers: Multidialectal practices of L2 Arabic learners. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 43, 759–773. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2020.1774595

Otheguy, R., García, O., and Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 6, 281–307. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

Otheguy, R., García, O., and Reid, W. (2019). A translanguaging view of the linguistic system of bilinguals. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 10, 625–651. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2018-0020

Polio, C. G., and Duff, P. A. (1994). Teachers’ language use in university foreign language classrooms: A qualitative analysis of English and target language alternation. Mod. Lang. J. 78, 313–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02045.x

Rolin-Ianziti, J., and Brownlie, S. (2002). Teacher use of learners’ native language in the foreign language classroom. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 58, 402–426. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.58.3.402

Sali, P. (2014). An analysis of the teachers’ use of L1 in Turkish EFL classrooms. System 42, 308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2013.12.021

Sert, O. (2015). Social interaction and L2 classroom discourse. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780748692651

Turnbull, M. (2001). There is a role for the L1 in second and foreign language teaching, but…. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 57, 531–540. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.57.4.531

Turnbull, M., and Arnett, K. (2002). Teachers’ uses of the target and first languages in the classroom. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 22, 204–218. doi: 10.1017/S0267190502000119

Turnbull, M., and Dailey-O’Cain, J. (eds) (2009). First language use in second and foreign language learning. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/9781847691972

Turner, M., and Lin, A. (2017). Translanguaging and named languages: Productive tension and desire. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Bilingu. 23, 423–433. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2017.1360243

van Compernolle, R. A. (2015). Interaction and second language development: A Vygotskian perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/lllt.44

Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl. Linguist. 39, 9–30. doi: 10.1093/applin/amx039

Younes, M. (2015). The integrated approach to Arabic instruction. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315740614

Zaky, M., and Palmer, J. (2018). “Integration and student’ perspectives within an integrated program,” in Arabic as one language: Integrating dialect in the Arabic language curriculum, ed. M. Al-Batal (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 279–297. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1fj85jd.19

Keywords: L2 Arabic, translanguaging, multilingual and multidialectal practices, teachers’ beliefs vs. practices, the integrated approach, language ideology in L2 learning, diglossia

Citation: Kawafha H and Al Masaeed K (2023) Multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging in L2 Arabic classrooms: teachers’ beliefs vs. actual practices. Front. Educ. 8:1060196. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1060196

Received: 02 October 2022; Accepted: 06 April 2023;

Published: 03 May 2023.

Edited by:

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lama Nassif, Williams College, United StatesJeff MacSwan, University of Maryland, College Park, United States

Kirk Belnap, Brigham Young University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Kawafha and Al Masaeed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Khaled Al Masaeed, bWFzYWVlZEBhbmRyZXcuY211LmVkdQ==

Hazem Kawafha1

Hazem Kawafha1 Khaled Al Masaeed

Khaled Al Masaeed