95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 23 February 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1058519

This article is part of the Research Topic The Quality of Life of Students and Teachers at School, College, High School and University View all 10 articles

Introduction: The emerging adult stage of life is a time of many positive changes, as well as stress and uncertainty. Certain psychological characteristics - such as emotional regulation, attachment style, or assertiveness – could help these adults thrive and maintain positive mental health. This study aimed to explore the influence of these variables on the well-being of emerging adults.

Methods: The sample included 360 French emerging adults, with a mean age of 21.3 years. Well-being was assessed with the Mental Health Continuum, emotional regulation with the Emotional Regulation Difficulties Scale, assertiveness with the Assertiveness Scale, and attachment styles with the Relationship Scales Questionnaire.

Results: Results showed that judgment toward one’s own emotional experience and shyness (as part of assertiveness) predicted emerging adults’ well-being. This study also highlighted the role of substance use and experiences of violence on emerging adults’ emotional regulation and well-being.

Discussion: Results support the importance of in-person and distance education and prevention to support emerging adults’ well-being, especially in higher education institutions and in times of the COVID pandemic.

Studies show that emerging adults face many daily stressors of psychological (personal problems, lack of emotional security) and social nature (financial problems, time management, and household chores; Martin-Krumm and Tarquinio, 2019). Many also experience pressure related to the transition to higher education, the development of professional activity, and the beginning of more stable intimate relationships (Arnett, 2016). Among students, assessed stress rates vary between 18 and 90%, depending on the country and the measurement instruments used (Zebdi et al., 2021, in Romo and Fouques, 2021). The French National Survey of Student Living Conditions (2016) showed that, among 15 to 25-year-olds, 60% of youth reported feeling stressed.

The well-being of emerging adults is therefore a societal issue. Moreover, understanding the well-being of emerging adults in France is important for various reasons. It can help researchers, policymakers, and practitioners better understand the challenges and opportunities faced by the next generation of the country and identify ways to support their positive development. Additionally, studying the well-being of emerging adults in France can inform the development of policies and interventions that support the well-being of emerging adults around the world, as many of the issues faced by French emerging adults may be close to those faced by young people in other countries (see “Discussion”). However, it is important to consider potential constraints, such as cultural, economic, and institutional barriers, that may affect the effectiveness of these interventions, as well as the need of the targeted population.

Several areas of daily functioning are concerned with well-being: physical, mental, social, financial, occupational, environmental, spiritual, and personal. Well-being can be defined as a subjective evaluation of life (Diener, 1984), in which feelings of satisfaction and balance are found, especially between positive and negative emotions. The individual feels fulfilled, secure, satisfied, in harmony, engaged, and focused on the existential challenges of life (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Keyes et al., 2002). Well-being would therefore imply positive emotions, engagement in life, satisfying interpersonal relationships, and feelings of meaning and achievement (Seligman, 2011).

Several factors can determine the well-being of emerging adults, especially that of students: support from family, and loved ones (Qi et al., 2020), resilience, self-efficacy, and mindfulness disposition (Harding et al., 2019). Other factors of well-being include optimism (Seligman, 1991), hope (Delas et al., 2015), positive emotions, the ability to find meaning (Seligman, 2011; Noemic, 2018), positive relationships, self-acceptance (Ryff, 1995), self-esteem, autonomy, and a sense of control (Bandura, 1997). Emotional regulation (Guassi Moreira et al., 2022), assertiveness (Sarkova et al., 2013), and attachment styles (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007) have also been considered variables influencing well-being, especially among youth. The effect of these three variables on emerging adults’ well-being will be the focus of the present study, as they seemed to have attracted less attention from researchers than the others listed above.

Emotion regulation is the adaptative influence one has on its own emotions and those of others, in various and changing situations (Gross, 1999; McRae and Gross, 2020). It supports better coping and well-being (Gross, 2014). It involves understanding and managing emotions through strategies for modulation and constructive expression (McRae and Gross, 2020).

The ability to regulate emotions influences stress and mental health at all ages (De France and Hollenstein, 2019), as well as the quality of life (Manju and Basavarajappa, 2017). Emotional regulation problems are associated with the development of various mental disorders (Gratz and Gunderson, 2006; Berking and Wupperman, 2012), such as depression (Hong et al., 2019), anxiety (O’Toole et al., 2019), borderline personality disorder, substance and social media abuse (White-Gosselin and Poulin, 2022), etc.

In adolescents, emotional dysregulation is also related to psychological inflexibility Cobos-Sánchez et al., 2020. In emerging adults, emotional dysregulation is associated with regular and heavy cannabis use, among other things (Brook et al., 2016). The ability to regulate emotions helps cope with stress and predicts fulfillment and positive mental health (Gross and Muñoz, 1995). In emerging adults, feeling able to regulate their emotions is associated with well-being (Guassi Moreira et al., 2022). Enhancing emotional regulation abilities is considered likely to psychologically improve the individual (McMain et al., 2010), reduce stress, and support mindfulness (Prakash et al., 2015). In the general population, emotional clarity, i.e., the ability to identify, understand and distinguish one’s emotions, is associated with emotion regulation (Vine and Aldao, 2014).

The attachment style may be considered an important variable to understand the well-being of a variety of age categories e.g., (see Platts et al., 2022, for a longitudinal study on attachment styles). As individuals from other age groups, the emerging adult is a social animal. Emerging adults interact with actors who make up their environment (peers, romantic relationships, families, colleagues, or teachers). Attachment theory describes beliefs and patterns in the way we relate to others. These develop from the positive and/or negative interactions of the child and the attachment to the caregiver (the parent or any other caregiver). The former transfers these experiences to the patterns of interpersonal relationships developed throughout their life (Bowlby, 1969; Fraley and Waller, 1998; Fraley and Shaver, 2021). Therefore, attachment styles are patterns of interpersonal relationships that tend to continue throughout life and have a significant impact on the individual’s personal (Bowlby, 1988) and professional functioning (Ronen and Zuroff, 2017). Moreover, attachment styles in adulthood are associated with intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, including personality traits, emotional capacities, emotional regulation, attitudes, beliefs, and expectations of others (Kobak and Sceery, 1988; Shaver and Brennan, 1992; Wearden et al., 2008; Fraley and Shaver, 2021).

To study attachment styles, individuals can be divided along a dual continuum of abandonment anxiety and proximity avoidance (Fraley and Waller, 1998). Abandonment anxiety refers to the representation of the self in a relationship. It is the degree to which the individual worries and broods about being abandoned or rejected. Proximity avoidance refers to one’s mental representation of the other. It manifests in discomfort with emotional intimacy and dependence in a relationship. The avoidant individual invests less in the relationship and values psychological and emotional independence. In Bartholomew’s model of adult attachment, there are four adult attachment styles: secure, preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing (Bartholomew, 1990, in Griffin and Bartholomew, 1994). These four styles also position according to the two dimensions previously described: (1) the secure attachment style (low anxiety and avoidance); (2) the insecure-anxious attachment style (high anxiety and low avoidance); (3) the insecure-avoidant attachment style (low anxiety and high avoidance); and (4) the insecure fearful attachment style (high anxiety and avoidance; Bowlby, 1958; Ainsworth and Bell, 1970).

The studies on the topic show that a secure attachment style is a predictor of better-perceived health, emotional regulation, and well-being than insecure styles (Bruno et al., 2018; Machado et al., 2019; Marrero-Quevedo et al., 2019; Fraley and Shaver, 2021; Moreira et al., 2021). The attachment styles also predict the quality of mental health. For example, Zhang et al. (2022) showed that insecure attachment style highly increased the risk of poor mental health. Therefore, this variable seems likely to be a determinant of well-being in emerging adults.

Assertiveness is about expressing ideas, opinions, feelings, and limits, confidently, while respecting those of others and considering the potential consequences of what was expressed. It includes both positive and negative expressions and aims at achieving personal, instrumental, or organizational goals (Pfafman, 2017). In a world that some authors call VUCA (Millar et al., 2018) for Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity, developing communication skills such as assertiveness seems necessary for emerging adults. It serves an adaptive aim. Assertiveness can be characterized by aspects such as confidence, respect, clarity of communication, self-control, and empathy (Pfafman, 2017).

Data collected from two independent samples of middle school students in an urban environment provided evidence that assertiveness significantly increased specific types of social relationships and predict psychological symptoms under stressful conditions (Elliott and Gramling, 1990). Several studies on assertiveness development programs have shown the positive impact of this variable on individuals’ stress (Tavakoli et al., 2009; Eslami et al., 2016; Noh and Kim, 2021). In addition, a study showed that in American students, an anxious or avoidant attachment style led to a lack of assertiveness (Ling, 2020). Therefore, attachment styles and assertiveness are related. As previously underlined, an insecure attachment style leads emerging adults to develop poorer perceived health, poorer emotional regulation, and lower well-being.

Attachment style is a rather stable variable difficult to modulate in the short term. However, by acting on the emotional regulation and assertiveness of emerging adults, it may be possible to support their well-being.

To summarize, several variables can impact emerging adults’ well-being, such as support from family and loved ones, resilience, self-efficacy, mindfulness disposition, optimism, hope, positive emotions, the ability to find meaning, positive relationships, self-acceptance, self-esteem, autonomy, and a sense of control. In particular, the present study focused on the effect of emotional regulation, assertiveness, and attachment style on the well-being of emerging adults. These variables may impact their well-being, as they face daily stressors of psychological and social nature, as well as pressure related to education, professional development, and intimate relationships.

Therefore, in this study, it was hypothesized that emerging adults’ well-being would be related to their emotional regulation, attachment style, and assertiveness, and would be predicted by these three variables. It was also assumed that emerging adults’ lack of emotional awareness and emotional clarity would be negatively related to their well-being. Moreover, it was hypothesized that a secure attachment style would lead to better well-being than insecure styles. Finally, it was assumed that emerging adults who regularly use cannabis would show stronger emotional dysregulation than those who use it occasionally or do not use it at all.

This exploratory study was conducted with 360 emerging adults aged 18–25, mainly in the Paris region and the Grand Est region of France. The recruitment period lasted 3 weeks, in February 2022. Table 1 presents the socio-demographic data of the participants (see “Tables”).

To summarize, most participants were in their very early adulthood (M = 21.2, SD = 2.2), with a majority of women (77.6%). A large proportion of the participants were students in a higher education institution (n = 300), particularly in the private field (n = 228). The sample of participants was randomly coming from three sources. The students at the higher education institution received oral information about the research during the welcoming week (September) and an email to solicit participation in February. The Grand Est participants received an email to solicit participation through a list of emerging adults formerly involved in the boy and girl scouts. Some of the participants also read the information on Internet forums dedicated to French emerging adults. Half had a part-time job (53.8%), and a quarter had a full-time job (25.2%). The parents were mostly executives or employees. A large proportion of the participants did not smoke cigarettes (72.8%), or cannabis (86.9%). Many participants believed that they had not been victims of violence or neglect (43.9%), but 32% thought they had been victims of psychological violence and 15.3% of sexual violence. Half of the participants perceived to have been moderately or strongly affected by the COVID pandemic (49.6%).

The initial research design used was quantitative and correlational. However, to ensure the fidelity and validity of the measures, the analyses have been extended to take into account the factorial dimension. There was one dependent variable: emerging adults’ well-being. The independent variables were emotional regulation, attachment style, and assertiveness. Using cluster analysis, we created three attachment groups (secure, anxious, and avoidant). There were 97 participants with an anxious attachment, 134 with an avoidant attachment, and 122 with a secure attachment. The socio-demographic data collected were gender, age, the institution of study, professional activity, socio-professional categories of parents, consumption (cigarettes, cannabis, alcohol, online money gambling, or video games), perceived abuse or neglect, and the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants completed the Mental Health Continuum–Abbreviated Questionnaire (CSM-QA). This assessment tool is easy to understand for researchers, and to insert in a long research form, reducing participants’ fatigue during the administration. The CSM-QA (short form) has three dimensions: emotional well-being (3 items: positive emotions, interest in life, satisfaction), psychological well-being (6 items: self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relationships, personal growth, autonomy, purpose in life), and social well-being [5 items: social contribution, social integration, social actualization, self-acceptance, social coherence (Orpana et al., 2017)].

The CSM-QA is a self-reported scale, of 14 items, rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 6, ranging from “every day” to “never.” Higher scores indicate a higher level of well-being. The French version was validated by 68.4% of respondents aged 15 and over, out of 25,113 Canadians asked to participate in a health survey (2012, Canadian Community Health Survey - Mental Health). It has good psychometric qualities. The emotional, psychological, and social well-being subscales have good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of α = 0.82 for the first two, and α = 0.77 for the social subscale (Orpana et al., 2017). The three-factor model also presented an acceptable fit across different samples. The psychological and emotional subscales of well-being significantly and positively correlated with life satisfaction (0.57) and perceived mental health (0.47), and negatively correlated with psychological distress, negative social interactions, and the WHO disability assessment scale. The social well-being subscale weakly correlated with related concepts, such as social dispositions and negative social interactions. The researchers underlined the weakness of the social subscale, as other studies have Petrillo et al. (2015).

Participants also completed the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) (Gratz and Roemer, 2004). This scale is one of the most widely used self-reported tools to assess emotion regulation strategies, especially in clinical practice (Gratz and Gunderson, 2006). It assesses difficulties in regulating emotions using 36 items and includes six subscales: non-acceptance of one’s emotional response, difficulty in adopting goal-oriented behaviors in a negative emotional context, lack of emotional awareness, difficulty in identifying one’s own emotions, difficulty in controlling oneself in a negative emotional context (impulsivity), difficulty implementing emotion regulation strategies in a negative emotional context (Gross, 2014). Each item is rated on a scale of 0 to 5, ranging from “rarely” to “seldom.” The scores obtained on the subscales can be added together to obtain an overall score. The higher the overall scale score, the more difficulties the subjects have in regulating their emotions. The French version of the scale, tested on 455 healthy students, has very good psychometric qualities, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient α = 0.92. The tool was validated with a student population similar to the one in the present study. The French version has strong compatibility with the English version, i.e., 94%. On a period of 9 weeks, the test–retest reliability was good, with the scores being highly correlated [0.88 (p < 0.01) (Dan-Glauser and Scherer, 2013].

Participants filled out the French version of the Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ, Griffin and Bartholomew, 1994; Wongpakaran et al., 2021; French version: Guédeney et al. 2010). This scale has 30 items and was developed from the Relationship Questionnaire, (RQ, 2) and the Adult Attachment Scale (AAS). Only 17 items are specific to the RSQ. Subjects answer to the items on a scale ranging from 1 “not at all like me” to 5 “completely like me.” Despite Bartholomew’s four adult attachment styles model, validation studies tend to suggest that the RSQ contains three factors (Griffin and Bartholomew, 1994). In their validation study with 136 adults, Guédeney et al. (2010) found a three-factor structure: Avoidance (7 items), Anxiety in the relationships (5 items), and Security (5 items). They uncovered Cronbach’s alpha coefficient between 0.60 < α < 0.69 for the factors, indicating an average consistency. More recently, Kpelly et al. (2020) also found a similar three-factor structure for a sample of 130 Togolese participants: Relationship safety, Avoidance, and Anxiety. However, the consistency was better, with the following Cronbach’s alpha coefficients: 0.81 for the Relationship safety factor, 0.77 for the Avoidance factor, and 0.69 for the Anxiety factor. The French version of the scale appeared to have quite good psychometric qualities. Therefore, the three-factor model seemed interesting, keeping in mind that its reliability may vary according to the sample used.

Participants filled out the French version of the Rathus assertiveness scale (RAS, Rathus, 1973; Bouvard et al., 1986). The questionnaire assessed the abilities for self-assertion across 30 social interactions. Seventeen items are reversed (1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 23, 24, 26, and 30). Each item is rated on a scale of 1 to 6, ranging from “very characteristic of me “to “very uncharacteristic “. The higher the total score, the more the subject experiences difficulties in self-assertion. The French version of the scale showed good psychometric qualities with 180 participants (125 suffering from psychopathology, and 55 in the control group), but the authors of the validation did not include the Cronbach alpha coefficient (Bouvard et al., 1986; see Table 2 for the characteristics of the measurement instruments). After one month, the test–retest score was high for the control group (r = 0.85; p < 0.01). Rathus (1973) initially showed that the scale had moderate to high test–retest reliability (r = 0.78; p < 0.01) and split-half reliability (r = 0.77; p < 0.01). Gustafson (1992) also found the English version of the scale reliable in a sample of 144 Swedish college students, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.82. Finally, Suzuki et al. (2007) uncovered that the scale was reliable for a sample of 989 Japanese novice nurses (Suzuki et al., 2007) with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.84.

An email was sent to solicit voluntary participation in the study. Announcements were also posted on social media. The measures were administered once. The participants completed the four measures through online mode, as well as a socio-demographic questionnaire.

Regarding the data analyses, correlations were made between the dimensions of well-being, emotion regulation, attachment style, and assertiveness. Multiple linear regressions were performed to better understand the weight of emotional regulation, attachment style, and assertiveness on the well-being of emerging adults. With the three attachment groups resulting from the cluster analysis, ANOVAs were performed to compare the means of attachment styles. Post-hoc ANOVAs were performed, considering some socio-demographic variables (level of professional activity, feeling of having been impacted or not by COVID, cigarette and cannabis consumption), as well as emotional regulation. We also performed an a posteriori comparison of our sample with a clinical sample regarding emotional regulation.

Of the 360 participants, 7 were not retained because of missing data on the scales. Therefore, 353 subjects were kept for the analysis of the results. The participants’ scores are described in Table 3.

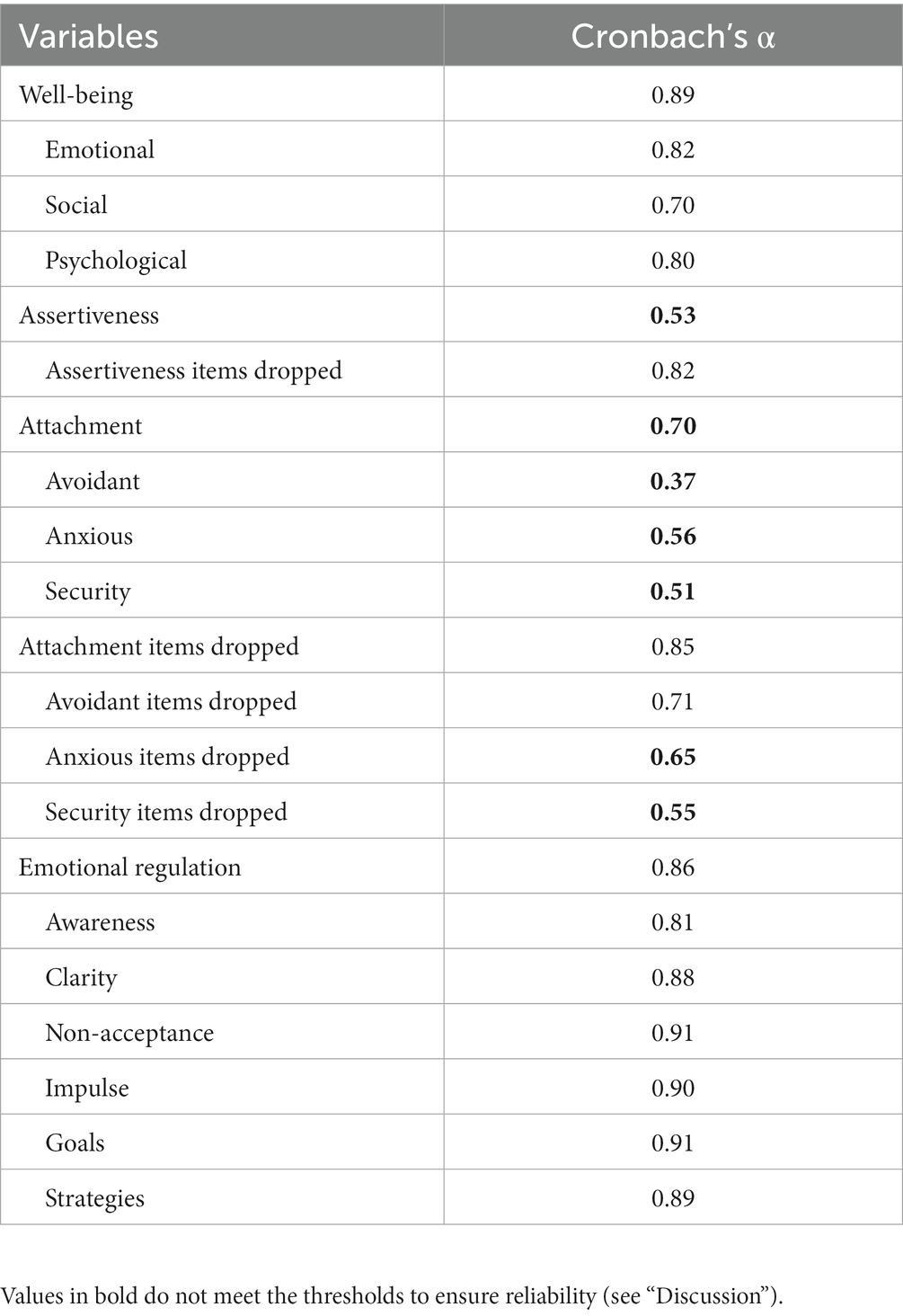

The statistical analyses were performed using the Jasp software. Given the sample size, it was possible to consider using parametric statistics. The Kurtosis and Skewness indices were between −2 and 2 for most variables. Therefore, they followed a normal distribution. It was then possible to produce parametric statistics, except for cannabis consumption. Fidelity analysis showed that three scales had good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.70 to 0.95 (well-being: α = 0.89; attachment: α = 0.70; emotional regulation: α = 0.86; Tavakol and Dennick, 2011).

However, the assertiveness scale and the attachment subscales had a Cronbach’s alpha of less than 0.70 (assertiveness: α = 0.53; avoidant attachment style: α = 0.37, anxious attachment style: α = 0.56; secure attachment style: α = 0.51), which signals low internal consistency and will be discussed later (see Table 4). Therefore, a procedure of dropped items was applied to both assertiveness (RAS) and attachment scales (RSQ). After the procedure, Cronbach’s alpha met the threshold with α = 0.82 for the RAS, α = 0.85 for the RSQ, and α = 0.71 for the avoidant attachment style (RSQ). For the anxious attachment style and the security in relationships, Cronbach’s alpha did not meet the threshold after the procedure (Table 4).

Table 4. Reliability analysis of the scales (well-being, assertiveness, attachment, and emotional regulation) before and after the items dropped procedure.

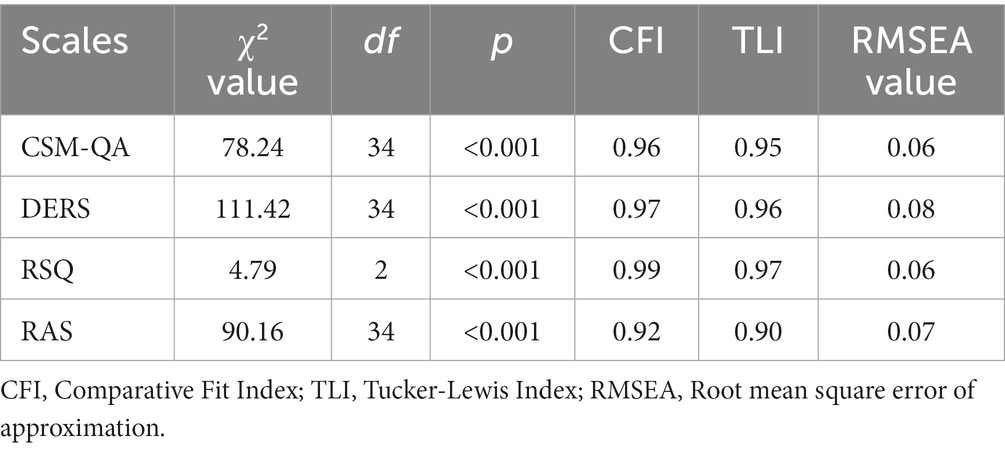

To ensure the validity of our scales, we conducted exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory (CFA) analyses. For the EFA, the number of factors was determined according to the Kaiser-Guttman criterion (E.I., eigenvalues greater than 1) and the elbow method (i.e., graphically, from the break inertia gain curve). Only factors accounting for at least 5% of the variance were retained. For the CFA, several statistics were used to assess the fit of a suggested factor structure to the collected data: the Khi2, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Expected values should be less than 0.06 for the RMSEA, and greater than 0.95 for the CFI/TLI to consider that the model fits the data (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Values close to the standards (e.g., RMSEA<0.10 or CFI/TLI >0.90) can still be accepted in light of the overall indices obtained (Kenny et al., 2015).

The CMS-QA seemed fairly reliable and valid to measure well-being. With an EFA analysis, we found that two factors only were measured in our sample: (1) the theme of psychological well-being, and (2) the social well-being, respectively accounting for 37 and 5% of the variance (p < 0.001). The item-reduced scale was fairly reliable and valid for our sample with this two-factor structure (Table 5).

Table 5. Confirmatory factor analysis (psychological and social well-being, self-criticism and concentration when faced with difficult emotions, shyness, and conflict avoidance, need for independence).

The DERS seemed fairly reliable and valid to measure emotional regulation. With an EFA analysis, we found that there were only two factors measured in our sample: (1) the theme of self-criticism, guilt, and shame in emotional situations, and (2) the difficulties concentrating on work/studies in emotional situations, respectively accounting for 34 and 11% of the variance. The item-reduced scale was fairly reliable and valid for our sample in this two-factor structure (Table 5).

Even though the assertiveness scale did not seem reliable for our sample, scientific literature exists about its reliability and validity. The scale is ancient but seemed more appropriate than other recent scales. We wanted to measure assertiveness in emerging adults and not connected constructs (such as social anxiety, e.g., Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale). With an EFA analysis, we found two factors measured in our sample: (1) the theme of shyness and hesitation in social interactions, and (2) the tendency to repress emotions to avoid conflicts, respectively accounting for 23 and 5% of the variance (p < 0.001). The item-reduced scale was fairly reliable and valid for our sample in this two-factor structure (Table 5).

The anxiety and security dimensions of the attachment style scales did not meet the threshold for consistency, even with the items dropped. The EFA and the CFA on the remaining items (avoidance) did not allow us to confirm that the item-reduced scale was reliable and valid for our sample (p = 0.09; Table 5).

The Kurtosis and Skewness of the new factors were tested and followed a normal distribution.

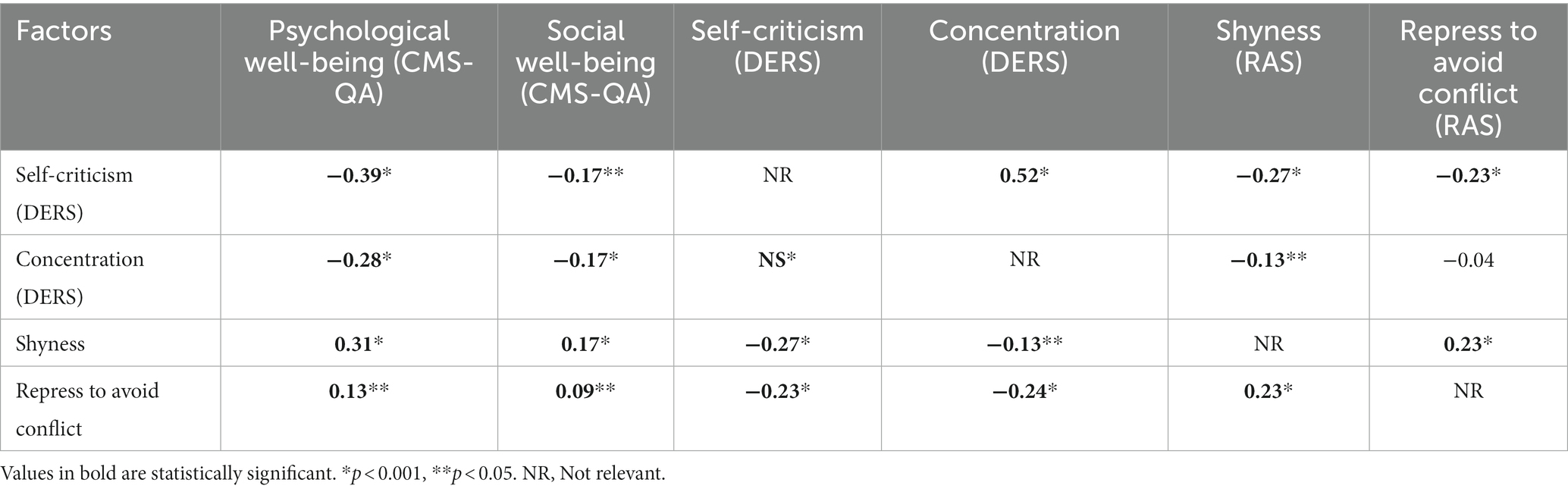

In this study, we supposed that emerging adults’ well-being would be related to their emotional regulation, attachment style, and assertiveness, and would be predicted by these three variables. The results showed that psychological well-being is negatively correlated with self-criticism when experiencing emotions (r = −0.39, p < 0.001), positively correlated with shyness (r = 0.31, p < 0.001), negatively correlated with difficulties concentrating when experiencing emotions (r = −0.28, p < 0.001), and positively correlated with repression of emotions to avoid conflicts (r = 0.14, p = 0.01; Table 6).

Table 6. Correlations and p values for well-being, self-criticism, concentration, shyness, and repressed emotions.

There was a moderate negative correlation between self-criticism and difficulties concentrating when experiencing emotions (r = −0.52, p < 0.001), as well as a moderate negative correlation between self-criticism when experiencing emotions and shyness (r = −0.27, p < 0.001), and repression of emotions to avoid conflict (r = −0.23, p < 0.001). Additionally, there was a moderate correlation between shyness and repression of emotions to avoid conflict (r = 0.23, p < 0.001), and a moderate negative correlation between shyness and self-criticism when experiencing emotions (r = −0.27, p < 0.001).

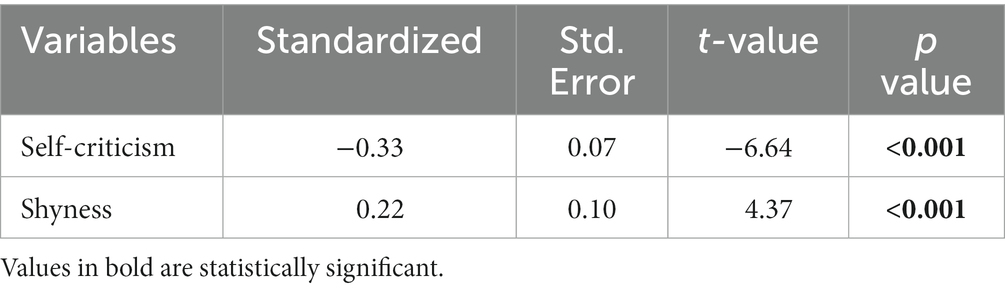

Linear regressions were performed to predict emerging adults’ psychological and social well-being. The results showed that self-criticism when experiencing emotions and shyness significantly predicted psychological well-being [F(2, 352) = 42.40, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.20]. The results also showed that self-criticism when experiencing emotions and shyness predicted social well-being [F(2, 352) = 39.60, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.05], and that difficulties concentrating when experiencing emotions and shyness predicted social well-being [F(2, 352) = 43.70, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.05] (Table 7).

Table 7. Linear regressions and p value for the impact of self-criticism when experiencing difficult emotions, and shyness on psychological well-being.

As it is well known, correlations are interesting to understand phenomena but do not allow to establish causality effects.

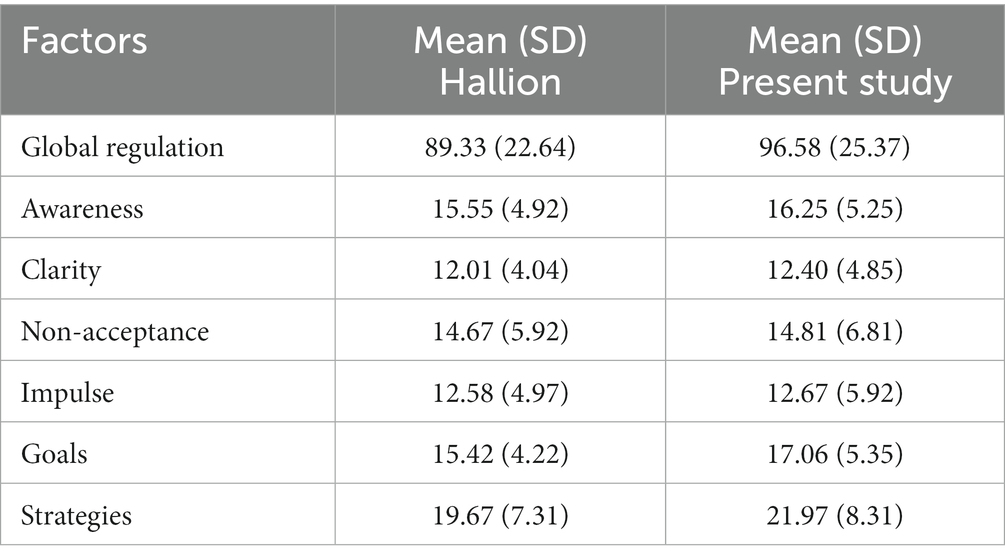

In this study, it was assumed that emerging adults’ lack of emotional awareness and emotional clarity would be negatively related to their well-being. Hallion et al. (2018) conducted a validation study of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) with adults suffering from emotional disorders. Compared to this clinical sample of 427 adults diagnosed with one or more DSM-5 disorders (Hallion et al., 2018), our sample of emerging adults had high emotional regulation scores, possibly signaling a dysregulation, as well as high scores for lack of emotional awareness, difficulty with goal orientation, and limited access to emotion regulation strategies (see Table 8). As the database of Hallion and colleagues’ research was not available, it was unfortunately not possible to compare the score of the two independent populations (the population of the present study and that of Hallion et al.) using Student’s t-tests.

Table 8. Means and standard deviations for each dimension of emotional regulation in the clinical sample (n = 427) and the present study (n = 360).

The study attempted to find a relationship between attachment style and well-being in emerging adults, but the results were inconclusive due to difficulty in measuring attachment styles in the specific sample.

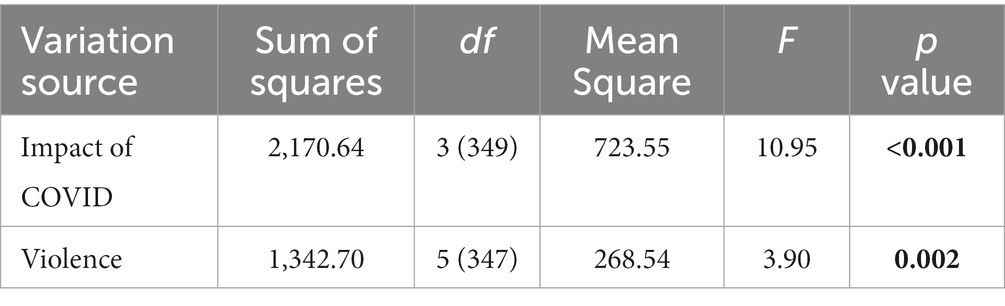

Because a significant number of participants reported working, being affected by COVID, smoking cigarettes or marijuana, or having experienced violence, we conducted ANOVAs on emotional regulation (with the two-factor structure) and these variables. The results showed no significant differences in emotional regulation scores based on employment status (p = 0.95), cigarette use (p = 0.27), or cannabis use (p = 0.26).

However, the study found that the emotion regulation of participants who reported being affected by COVID-19 significantly differed, at a 95% confidence interval, [F(3, 349) = 10.95, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.09] from those who were not (p = 0.01), or from those who felt slightly impacted (p = 0.04), with a moderate effect size1 (Table 9).

Table 9. Result of the analysis of variance (ANOVA), with self-criticism and difficulty concentrating when experiencing emotions as the dependent variable.

The study also found that the emotion regulation of participants who reported having undergone physical abuse significantly differed, at a 95% confidence interval, [F(5, 349) = 3.90, p = 0.002, η2p = 0.05] from those having experienced sexual violence (p = 0.003), or from those having experienced psychological (p = 0.02), with a moderate effect size.2

This study found that psychological well-being was negatively related to self-criticism and difficulty concentrating when experiencing emotions. Self-criticism and shyness together predicted 20% of emerging adults’ psychological well-being.

Compared to a clinical sample, the participants were emotionally dysregulated with a lack of emotional awareness, difficulty with goal-directedness in an emotional context, and limited access to emotion regulation strategies.

Additionally, the study found that emerging adults who felt highly impacted by COVID and those who experienced sexual or psychological violence had a stronger sense of emotional dysregulation compared to those who did not feel as impacted by COVID or who experienced physical violence.

This study used parametric statistics, allowing for solid conclusions to be drawn about a larger population. Important work has also been done to ensure that the scales were coherent and to identify what they measured in our sample. Thus, it can be assumed that the conclusions drawn can be relatively humble but robust.

This study suggested that self-criticism when experiencing emotions, and shyness may play a significant role in determining emerging adults’ well-being. More specifically, the variables explained a fifth of psychological well-being. Therefore, helping emerging adults develop a knowledge of their emotions, manage arousal and thoughts (Gross, 2014), influence their feelings, and modulate their expression (Gross, 1999) would be likely to foster the development of their well-being. The more emerging adults will be able to identify and regulate their emotions, the more they will probably be able to concentrate, feel accepting of themselves, and feel autonomous, fulfilled, and oriented in their life. The results of the current study are consistent with the study by Guassi Moreira et al. (2022), which showed that emerging adults felt more fulfilled when they sensed that they could regulate their emotions. The results of our study on emotional regulation and well-being thus align with American studies, suggesting that the interventions that we will suggest could potentially be extended to emerging adults in other locations around the world.

Also, helping emerging adults overcome shyness, gaining in confidence in social situations, and be able to express their opinions and feeling in front of others may sustain their well-being. Therefore, it may be possible, by emotional regulation, and assertiveness-building interventions, to strengthen emerging adults’ psychological well-being. But let us not forget there are many other variables contributing to understanding emerging adults’ well-being, such as support from loved ones, resiliency, optimism, positive emotions, self-efficacy, etc. It would be interesting to investigate how they interact with self-criticism when experiencing emotions, and with shyness to explain emerging adults’ well-being.

Shyness occurs during certain times of childhood and adolescence. It can also be a more durable personality characteristic. It is frequently associated with anxiety and stress (Crozier, 2001). It is often considered to hinder engagement in studies, and even promote avoidance of academic work and participation (Chen et al., 2018). However, in adverse situations, shyness may ironically be adaptative, in the sense that it allows one to avoid situations that are too stressful or avoid conflicts. This may be why we observed a moderate positive relationship between shyness and psychological well-being in emerging adults. For example, the COVID pandemic constituted a threat that people tried to avoid. As our study took place during COVID, adaptative avoidant behaviors of emerging adults may have contributed to successfully circumventing the threat.

This seems especially relevant considering that half of the participants in our sample felt dysregulated by the COVID pandemic. Our study provided information on predictors of well-being, but it also likely helped us capture the experience of emotional adversity of emerging adults during the COVID pandemic. In France and around the world, mental health issues increased among emerging adults since the COVID pandemic (Zerhouni et al., 2021), which was a lonely time for many emerging adults.

This study showed that psychological well-being was negatively associated with shyness and self-criticism in emotional situations. The less the emerging adults were shy, hesitating in social interaction, and judgmental about their subjective reactions, the more autonomous, fulfilled, life-oriented, and self-accepting they felt.

The comparison by the eye of our sample with a clinical sample of patients confirmed that participants in the present study had difficulty regulating their emotions, to goal-directedness in a negative emotional context, and had limited access to emotion regulation strategies. In our sample, emerging adults also appeared to lack emotional awareness and clarity (see Table 8), which seems consistent with the difficulties concentrating when experiencing emotions that we found as a predictor of psychological well-being.

Vine and Aldao (2014) showed the importance of clearly perceiving one’s emotions for being able to regulate them. Emotional clarity may be hindered by stress and relational problems. Moreover, this study showed that the more the emerging adults (mean age of 18.7 years) had the feeling that they could regulate their emotions and act on their emotions once upset, the more they felt autonomous, fulfilled, oriented in their life, and accepting of themselves. The study also showed that emotional clarity deficits were associated with mental health issues, such as depression, social anxiety, and alcohol abuse – psychological conditions that may hinder one’s capacity to find effective emotion regulation strategies. Therefore, suggesting intervention to support emotional regulation in emerging adults is also likely to enhance the prevention of mental health problems. Vine and Aldao (2014) even suggest that deficits in emotional clarity and emotional regulation may be transdiagnostic factors in psychopathology, as they are present in different mental disorders and are not specific to a single disorder.

The a posteriori results of the study showed that specific interventions could have been beneficial to the participants after the COVID pandemic to help them regulate their emotions. Especially for youth, the COVID pandemic led to stress and feeling of uncertainty due to lockdowns, social distancing, and student job loss. The isolation and lack of social support have also taken a toll on emerging adults’ well-being. Additionally, the pandemic disrupted access to education, healthcare, and other essential services, exacerbating existing inequalities and making it more difficult for youth to access the resources they need to maintain their well-being.

Additionally, we found a stronger subjective effect on the well-being of the participants of sexual and psychological violence compared to physical violence. Sexual violence can have a significant impact on an individual’s well-being because it can cause physical and emotional harm, feelings of shame, guilt, and powerlessness. It can also impair the sense of self-worth, the ability to trust others, to form healthy relationships, and to feel safe. It is also associated with risks of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The first research hypothesis was partially validated. Emerging adults’ well-being was associated with their self-criticism in emotional situations (a dimension of emotional regulation), and shyness (a dimension of assertiveness), and was predicted by these variables. The second hypothesis was partially validated: the difficulties concentrating when experiencing emotions (close to the lack of emotional clarity) were negatively related to well-being. The third hypothesis regarding well-being and attachment style was not validated. Finally, the results did not validate the fourth research hypothesis that emerging adults who regularly used cannabis had stronger emotional dysregulation than others.

The results of the study give the impression that remote education and prevention modules could have been offered during and after the COVID pandemic to help emerging adults regulate their emotions. Several in-person programs have been scientifically validated and positively impact emotional regulation and well-being. Some enhance psychological resources (Marais et al., 2018; Shankland et al., 2022, i.e., hope, optimism, resiliency, self-efficacy, and self-esteem), reduce depression, anxiety, substance abuse, stress (Hayes et al., 2006, i.e., psychological flexibility), or cognitive fusion, and experiential avoidance (Gagnon, 2018, i.e., mindfulness, MBSR). These programs could be adapted and validated for emerging adults, in person and remotely, in France, and other countries around the world. In addition, the need for education and prevention of the effects of violence on emerging adults’ emotional regulation appeared in our study, but also in other countries. The same programs as those mentioned above could be used, probably in several countries. Also, reducing the impacts of violence, especially sexual and psychological ones, should be addressed in higher education institutions.

McMain et al. (2010) think that it is possible to psychologically enhance people, by helping them improve their emotional regulation abilities. This study highlighted certain dimensions of emotional regulation that could be worked on with emerging adults, namely the judgment toward their own emotional experience and the ability to know to be aware and understand one’s emotions.

Mindfulness sessions could be used to strengthen emotional regulation, help develop the ability to observe and let go of inner states and outer events, develop concentration on goals when experiencing negative emotions (Kabat-Zinn, 2003), a better ability to feel engaged by information from the body and to notice subtle changes (Lefranc et al., 2020), and improve well-being (Orzech et al., 2009). For example, the ‘Mindful Emotional Intelligence Program’ was tested on 136 college students for 2 months and helped them regulate their emotions (Enríquez et al., 2017). Moreover, in a study conducted on emerging adults, mindfulness was associated with greater emotion differentiation and less emotional dysregulation and lability (Hill and Updergraff, 2012). Moreover, the ‘Mindfulness Based Coping with University Life’ can be used to help students develop psychosocial competencies like stress management, learning, communication, and relationships (Lynch et al., 2011).

Moreover, developing strategies to enhance cognitive reappraisal could help emerging adults manage arousal and influence their emotions. Cognitive reappraisal refers to identifying how rational one’s emotional response was and determining the accurate importance of a stressor. Studies have shown that cognitive reappraisal was positively correlated with well-being and negatively with psychological symptoms (Gross and John, 2003; Aldao et al., 2010). It also helped feel and express positive emotions, and reduce negative emotions (John and Gross, 2004). Also, ‘Brief Emotion Regulation Training’ (BERT) has been used to strengthen emotional regulation in emerging adults. It is a 5-week program inspired by Gross’ model. It was tested by Gatto et al. (2022) on 42 emerging adults. Important improvements in emotional regulation, psychological distress, and negative affectivity were shown. The program also exists in a brief electronic format, reducing the barriers of distance.

From a global health perspective also considering the development of remote tools, our college counselors’ colleagues may suggest the use of certain free access applications to students, especially the ones helping develop mindfulness, cognitive defusion, and psychological resources, but these may not be scientifically validated. Consequently, to ensure efficiency, we suggest that they complement this suggestion with scientifically based interventions. For instance, their institution may enter into agreements with the organizations broadcasting mindfulness, and emotional regulation training such as the one cited before. This way, they will be able to direct students to these resources.

The present study also showed the role of shyness in predicting emerging adults’ capacity to grow (psychological well-being). Therefore, it was assumed that there might be an interest in improving emerging adults’ self-confidence to strengthen their emotional regulation capacity and foster their well-being. Moreover, Lin et al. (2004) found an improvement in assertiveness, self-esteem, and interpersonal communication satisfaction after nursing and medical students attended eight 2 sessions of assertiveness training once a week.

The internal consistency of the subscales ‘anxious’ and ‘security’ of the attachment scale did not reach the thresholds to ensure that the attachment styles were well measured, even when items were dropped. It was therefore not possible to assess the effects of attachment styles on emerging adults’ well-being. In addition, the value of the standard deviation of each dimension of emotional regulation appeared to be high in comparison to the respective mean value. However, the validation study of Dan-Glauser and Scherer (2013), and our analysis of reliability showed the good psychometric qualities of the DERS scale (consistency and validity), including for our sample. Also, the exploratory and confirmatory factorial analysis showed the validity of the scale for measuring emotional regulation with two factors. Finally, it would have been interesting to look at the housing conditions (co-housing, living with parents, living alone, with a partner) of the participants to better understand the impact of the support received (or not received) on the variables studied.

Moreover, at the conceptual level, it sometimes seemed difficult to delineate emotional regulation from mindfulness. Perhaps, these concepts overlap and could gain by being replaced by the notion of reflexivity (Plantade-Gipch et al., 2021). Also, this study was conducted after the confinement related to the COVID decreed by the President of the French Republic in 2021. Since then, studies indicate increased distress among emerging adults (i.e., depression, anxiety; Zerhouni et al., 2021), which may have tended to increase certain results of this research, particularly in terms of difficulties in emotional regulation. Also, an important part of the participants in this study came from private higher education institutions, which could have had incidences on the results of the study. A better-balanced sample would be required. Finally, as all the scales were administered at the same time, in a transversal perspective, it would be delicate to infer causality relationships between the variables. It would be interesting to replicate the study with a longitudinal research plan.

The study highlighted the role of one’s judgment on emotional experience, and shyness, as predictors of emerging adults’ well-being, especially in times of the COVID pandemic. Self-criticism when experiencing emotions, and shyness, predicted 20% of emerging adults’ psychological well-being. The study also suggests that emerging adults who experienced high levels of impact from COVID-19 or reported experiencing sexual and psychological violence in their lives had higher levels of emotional dysregulation than those who did not experience those situations. Finally, the study seemed to show that emerging adults who had limited emotional awareness and clarity felt less psychological well-being.

The study has several limitations related, in particular, to measurement instruments, especially those assessing assertiveness, and attachment styles. However, the consistency analysis and the EFA and CFA analyses helped us maintain solid results. The lack of information on the housing conditions of the participants may have limited the ability to fully understand the impact of support on the studied variables. Given that there are interesting results in this study, several programs associated with developing mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal, and assertiveness-building interventions were explored to develop emerging adults’ well-being. It would be interesting to create an integrative program and assess it with emerging adults in further research. Emerging adults could then benefit from this validation, and eventually the use of this composite program, to foster their well-being, especially in higher education institutions.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the direction of Ecole de Psychologues Praticiens. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Reference values for the partial eta-square (η2p) are as follows: around 0.01: small effect size; around 0.06: moderate effect size; around 0.14 and above: large effect size.

2. ^Reference values for Kendall’s W are as follows: around 0.1: small effect size; around 0.3: moderate effect size; 0.5 and above: large effect size.

Ainsworth, M. D., and Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development 30, 217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., and Schweizer, S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 49–67. doi: 10.2307/1127388

Arnett, J. J. (2016). Does emerging adulthood theory apply across social classes? National data on a persistent question. Emerg. Adulthood 4, 227–235. doi: 10.1177/2167696815613000

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

Berking, M., and Wupperman, P. (2012). Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 25, 128–134. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503669

Bouvard, M., Cottraux, J., Mollard, E., Messy, P., and Defayolle, M. (1986). Validation et analyse factorielle de l’échelle d’affirmation de soi de Rathus. Psychologie Médicale 18, 759–763.

Bowlby, J. (1969). “Attachment and loss, Vol. 1” in Attachment. Attachment and Loss (New York: Basic Books)

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. New York: Basic Books.

Brook, J. S., Zhang, C., Leukefeld, C. G., and Brook, D. W. (2016). Marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: developmental trajectories and their outcomes. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 51, 1405–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1229-0

Bruno, J., Machado, J., Ferreira, Y., Munsch, L., Silès, J., Steinmetz, T., et al. (2018). Impact of attachment styles in the development of traumatic symptoms in French women victims of sexual violence. Theol. Sex. 28, e11–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2018.04.006

Chen, Y., Li, L., Wang, X., Li, Y., and Gao, F. (2018). Shyness and learning adjustment in senior high school students: mediating roles of goal orientation and academic help seeking. Front. Psychol. 9:1757. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01757

Cobos-Sánchez, L., Flujas-Contreras, J. M., and Gómez Becerra, I. (2020). Relation between psychological flexibility, emotional intelligence and emotion regulation in adolescence. Curr. Psychol. 41, 5434–5443. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01067-7

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Manhattan, NY: Harper & Row.

Dan-Glauser, E. S., and Scherer, K. R. (2013). The difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS). Factor structure and consistency of a French translation. Swiss. J. Psychol. 72, 5–11. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185/a000093

De France, K., and Hollenstein, T. (2019). Emotion regulation and relations to well-being across the lifespan. Dev. Psychol. 55, 1768–1774. doi: 10.1037/dev0000744

Delas, Y., Martin-Krumm, C., and Fenouillet, F. (2015). La théorie de l’espoir, une revue de questions. Psychol. Fr. 60, 237–262. doi: 10.1016/j.psfr.2014.11.002

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Elliott, T. R., and Gramling, S. E. (1990). Personal assertiveness and the effects of social support among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology 37, 427–436. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.37.4.427

Enríquez, H., Ramos, N., and Esparza, O. (2017). Impact on regulating student emotion of the mindful emotional intelligence program. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 17, 39–48.

Eslami, A. A., Rabiei, L., Afzali, S. M., Hamidizadeh, S., and Masoudi, R. (2016). The effectiveness of assertiveness training on the levels of stress, anxiety, and depression of high school students. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 18:e21096. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.21096

Fraley, R. C., and Shaver, P. R. (2021). “Attachment theory and its place in contemporary personality theory and research” in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. eds. O. John and R. W. Robins. 4th ed (New York: The Guilford Press), 642–666.

Fraley, R. C., and Waller, N. G. (1998). “Adult attachment patterns: a test of the typological model” in Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. eds. J. A. Simpson and W. S. Rholes (New York: The Guilford Press), 77–114.

Gagnon, C. (2018). Évaluation de l’efficacité du programme « Être étudiant en pleine conscience ». Doctoral thesis, Trois-Rivières: University of Quebec in Trois-Rivières.

Gatto, A. J., Elliott, T. J., Briganti, J. S., Stamper, M. J., Porter, N. D., Brown, A. M., et al. (2022). Development and feasibility of an online brief emotion regulation training (BERT) program for emerging adults. Front. Public Health 10, 1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.858370

Gratz, K. L., and Gunderson, J. G. (2006). Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav. Ther. 37, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002

Gratz, K. L., and Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Griffin, D. W., and Bartholomew, K. (1994). Models of the self and other: fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 430–445. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.430

Gross, J. J. (1999). Emotion regulation: past, present, future. Cognit. Emot. 13, 551–573. doi: 10.1080/026999399379186

Gross, J. J. (2014). “Emotion regulation: conceptual and empirical foundations” in Handbook of Emotion Regulation. ed. J. J. Gross. 2nd ed (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 3–20.

Gross, J. J., and Muñoz, R. F. (1995). Emotion regulation and mental health. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2, 151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1995.tb00036.x

Gross, J. J., and John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85, 348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Guassi Moreira, J. F., Sahi, R., Ninova, E., Parkinson, C., and Silvers, J. A. (2022). Performance and belief-based emotion regulation capacity and tendency: mapping links with cognitive flexibility and perceived stress. Emotion 22, 653–668. doi: 10.1037/emo0000768

Guédeney, N., Fermanian, J., and Bifulco, A. (2010). Construct validation study of the Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ) on an adult sample. L’Encéphale 36, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2008.12.006

Gustafson, R. (1992). A Swedish psychometric test of the Rathus assertiveness schedule. Psychol. Rep. 71, 479–482. doi: 10.2466/PR0.71.6.479-482

Hallion, L. S., Steinman, S. A., Tolin, D. F., and Diefenbach, G. J. (2018). Psychometric properties of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS) and its short forms in adults with emotional disorders. Front. Psychol. 9:539. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00539

Harding, T., Lopez, V., and Klainin-Yobas, P. (2019). Predictors of psychological well-being among higher education students. Psychology 10, 578–594. doi: 10.4236/psych.2019.104037

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., and Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes, and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Hill, C. L. M., and Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion 12, 81–90. doi: 10.1037/a0026355

Hong, L., Xiaoguang, Y., and Wang, C. (2019). Emotional regulation goals of young adults with depression inclination: an event-related potential study. Acta Psychol. Sin. 51, 637–647. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2019.00637

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

John, O.-P., and Gross, J.-J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: personality processes, individual differences, and life-span development. J. Pers. 72, 1301–1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 10, 144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., and McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 44, 486–507. doi: 10.1177/0049124114543236

Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., and Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: the empirical encounter of two traditions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 1007–1022. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007

Kobak, R., and Sceery, A. (1988). Attachment in late adolescence: working models, affect regulation, and representations of self and others. Child Dev. 59, 135–146. doi: 10.2307/1130395

Kpelly, E., Schauder, S., Masson, J., Moukouta, C. S., Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., and Bernoussi, A. (2020). Validation transculturelle du relationship scales questionnaire en français. Revue québécoise de psychologie 41, 61–81. doi: 10.7202/1070663ar

Lefranc, B., Martin-Krumm, C., Aufauvre-Poupon, C., Berthail, B., and Trousselard, M. (2020). Mindfulness, Interoception, and olfaction: a network approach, brain. Science 10:921. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10120921

Lin, Y.-R., Shiah, J.-S., Chang, Y.-C., Lai, T.-J., Wang, K.-Y., and Chou, K.-R. (2004). Evaluation of an assertiveness training program on nursing and medical students’ assertiveness, self-esteem, and interpersonal communication satisfaction. Nurse Educ. Today 24, 656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2004.09.004

Ling, J. (2020). Cross-Cultural Adult Attachment, Assertiveness, Self-Conscious Emotions, and Psychological Symptoms, Dissertation. Denton, TX: University of North Texas.

Lynch, S., Gander, M. L., Kohls, N., Kudielka, B., and Walach, H.. (2011). Mindfulness-based coping with university life: A non-randomized wait-list-controlled pilot evaluation. Stress and Health 27, 365–375. doi: 10.1002/smi.1382

Machado, J., Bruno, J., Rotonda, C., Siles, J., Steinmetz, T., Zambelli, C., et al. (2019). Partner attachment and the development of traumatic and anxious-depressive symptoms among university students. Theol. Sex. 29, e19–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2019.08.002

Manju, H. K., and Basavarajappa, D. (2017). Cognitive regulation of emotion and quality of life. J. Psychosoc. Res. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.25215/0401.136

Marais, G., Shankland, R., Haag, P., Fiault, R., and Juniper, B. (2018). A survey and a positive psychology intervention on French Ph.D. student well-being. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 13, 109–138. doi: 10.28945/3948

Marrero-Quevedo, R. J., Blanco-Hernández, P. J., and Hernández-Cabrera, J. A. (2019). Adult attachment and psychological well-being: the mediating role of personality. J. Adult Dev. 26, 41–56. doi: 10.1007/s10804-018-9297-x

Martin-Krumm, C., and Tarquinio, C. (2019). Psychologie Positive: État des savoirs, champs d’application et perspectives. Malakoff: Dunod.

McMain, S., Pos, A., and Iwakabe, S. (2010). Facilitating emotion regulation: general principles for psychotherapy. Psychother. Bullet. 45, 16–21.

Mikulincer, M., and Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. New York: The Guilford Press.

Millar, C. J. M., Groth, O., and Mahon, J. F. (2018). Management Innovation in a VUCA World: Challenges and Recommendations. California. Management Review 61. doi: 10.1177/0008125618805111

Moreira, P., Pedras, S., Silva, M., Moreira, M., and Oliveira, J. (2021). Personality, attachment, and well-being in adolescents: the independent effect of attachment after controlling for personality. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 1855–1888. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00299-5

Noemic, R. M. (2018). Character Strengths Interventions: A Field Guide for Practitioners. Newburyport, MA: Hogrefe Publishing.

Noh, G. O., and Kim, M. (2021). Effectiveness of assertiveness training, SBAR, and combined SBAR and assertiveness training for nursing students undergoing clinical training: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 103:104958. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104958

O’Toole, M. S., Renna, M. E., Mennin, D. S., and Fresco, D. M. (2019). Changes in decentering and reappraisal temporally precede symptom reduction during emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder with and without co-occurring depression. Behav. Ther. 50, 1042–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.12.005

Orpana, H., Vachon, J., Dykxhoor, J., and Jayaraman, G. (2017). Measuring positive mental health in Canada: construct validation of the mental health continuum-short form. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 37, 123–130. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.37.4.03f

Orzech, K. M., Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., and McKay, M. (2009). Intensive mindfulness training-related changes in cognitive and emotional experience. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 212–222. doi: 10.1080/17439760902819394

Petrillo, G., Capone, V., Caso, D., and Keyes, C. L. M. (2015). The mental health continuum–short form (MHC–SF) as a measure of well-being in the Italian context. Soc. Indic. Res. 121, 291–312. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0629-3

Pfafman, T. (2017). “Assertiveness” in Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. eds. V. Zeigler-Hill and T. K. Shackelford (New York: Springer Cham)

Plantade-Gipch, A., Drouin, M. S., and Blanchet, A. (2021). Can alliance-focused supervision help improve emotional involvement and collaboration between client and therapist? Europ. J. Psychother. Counsel. 23, 26–42. doi: 10.1080/13642537.2021.1881138

Prakash, R. S., Hussain, M. A., and Schirda, B. (2015). The role of emotion regulation and cognitive control in the association between mindfulness disposition and stress. Psychol. Aging 30, 160–171. doi: 10.1037/a0038544

Qi, M., Zhou, S. J., Guo, Z. C., Zhang, L. G., Min, H. J., Li, X. M., et al. (2020). The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 67, 514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.001

Rathus, S. A. (1973). A 30-item schedule for assessing assertive behavior. Behav. Ther. 4, 398–406. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(73)80120-0

Ronen, S., and Zuroff, D. C. (2017). How does secure attachment affect job performance and job promotion? The role of social-rank behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 100, 137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.006

Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 4, 99–104. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395

Sarkova, M., Bacikova-Sleskova, M., Orosava, O., Madarasova-Geckova, A., Katreniakova, Z., and Klein, D. (2013). Associations between assertiveness, psychological well-being, and self-esteem in adolescents. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 43, 147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816-2012.00988.x

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish a Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. Mumbai: Free Press.

Shankland, R., Gayet, C., and Richeux, N. (2022). La santé mentale des étudiants. Approches innovantes en prévention et dans l’accompagnement: un état des lieux. Îledefrance: Elsevier Masson.

Shaver, P. R., and Brennan, K. A. (1992). Attachment styles and the « big five » personality traits: their connections with each other and with romantic relationship outcomes. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 18, 536–545. doi: 10.1177/0146167292185003

Suzuki, E., Kanoya, Y., Katsuki, T., and Chifumi, S. (2007). Verification of reliability and validity of a Japanese version of the Rathus Assertiveness Schedule. Journal of Nursing Management, 15, 530–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00691.x

Tavakol, M., and Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Chronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Tavakoli, S., Lumley, M. A., Hijazi, A. M., Slavin-Spenny, O. M., and Parris, G. P. (2009). Effects of assertiveness training and expressive writing on acculturative stress in international students: a randomized trial. J. Couns. Psychol. 56, 590–596. doi: 10.1037/a0016634

The French National Survey of Student Living Conditions (2016). The French National Survey of Student Living Conditions. Available at: http://www.ove-national. education.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/La_sante_des_etudiants_CdV_2016.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2021).

Vine, V., and Aldao, A. (2014). Impaired emotional clarity and psychopathology: a Transdiagnostic deficit with symptom-specific pathways through emotion regulation. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 33, 319–342. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2014.33.4.319

Wearden, A., Peters, I., Berry, K., Barrowclough, C., and Liversidge, T. (2008). Adult attachment, parenting experiences, and core beliefs about self and others. Personal. Individ. Differ. 44, 1246–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.11.019

White-Gosselin, C.-É., and Poulin, F. (2022). Associations between young adults’ social media addiction, relationship quality with parents, and internalizing problems: a path analysis model. Canad. J. Behav. Sci., Advanced Online Publication. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000326

Wongpakaran, N., DeMaranville, J., and Wongpakaran, T. (2021). Validation of the relationships questionnaire (RQ) against the experience of close relationship-revised questionnaire in a clinical psychiatric sample. Healthcare 9:1174. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9091174

Zebdi, R., Mazé, C., and Saleh, D. (2021). “Focus sur le stress et les tracas quotidiens chez les étudiants: Un état des lieux dans le monde” in La santé mentale des étudiants: Comprendre et agir. eds. L. Romo and D. Fouques (Umeå: Umeå universitet), 39–59.

Zerhouni, O., Flaudias, V., Brousse, G., and Naassila, M. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on mental health in university students: a mini-review of the current literature. Rev. Neuropsychol. 13, 108–110. doi: 10.1684/nrp.2021.0664

Keywords: well-being, emerging adults, emotional regulation, assertiveness, attachment style

Citation: Plantade-Gipch A, Bruno J, Strub L, Bouvard M and Martin-Krumm C (2023) Emotional regulation, attachment style, and assertiveness as determinants of well-being in emerging adults. Front. Educ. 8:1058519. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1058519

Received: 30 September 2022; Accepted: 30 January 2023;

Published: 23 February 2023.

Edited by:

Sundaramoorthy Jeyavel, Central University of Punjab, IndiaReviewed by:

Mehmet Akif Karaman, American University of the Middle East, KuwaitCopyright © 2023 Plantade-Gipch, Bruno, Strub, Bouvard and Martin-Krumm. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anne Plantade-Gipch, ✉ YXBsYW50YWRlQHBzeWNoby1wcmF0LmZy

†ORCID: Anne Plantade-Gipch, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8695-7871

Julien Bruno, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8961-2633

Lionel Strub, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3513-8953

Martine Bouvard, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4306-9011

Charles Martin-Krumm, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6665-5566

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.