94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 23 February 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1056630

This article is part of the Research TopicTransforming Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan African Countries Towards the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4 by 2030: New Opportunities, Challenges, Problems and ProspectsView all 7 articles

We cannot overemphasize the importance of education in creating sustainable societies. Persons with disabilities continue to lag in education, which affects their employment and income and overall well-being. Education is necessary for persons with disabilities to break out of the cycle of poverty as recognized by both the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Sustainable Development Goals. Ghana developed an inclusive education policy in 2015 with an overarching goal of fostering equitable access to education for all children. The critical question is what to teach. The B.Ed. Curriculum in 2018 was written to reform education and the school curriculum. But how prepared are student teachers at Colleges of Education in Ghana. Using the curriculum to promote inclusive education? In this paper, we use the social model of disability, anchored on the Sustainable Development Goals, to examine the preparedness of student teachers in meeting the needs of learners with diverse learning needs.

Education has long been recognized as a global priority. For years, governments and other national and international stakeholders have focused their attention on making sure that all children can attend school, and they have backed up that commitment with reforms (Barrett et al., 2019). The Jophus Anamuah-Mensah Educational Reform report (2007) presented the structure of education in Ghana to consist of two to three years of nursery school, six compulsory years of primary school, three compulsory years of junior high school and another three years of senior high school. At the end senior high school (12th grade) students get to attend universities and other tertiary education institutions. The first 9 years constitute basic education and are free and compulsory.

According to the Colleges of Education Act of 2012, Act 847, the process of preparing teachers in Ghana to teach at the basic school level takes place at the College of Education (CoE). Presently, there are 48 Colleges of Education (CoE) in Ghana, up from 38 in 2014 (Buabeng et al., 2019) and in the 2018/2019 academic year, all Colleges of Education in Ghana were upgraded to University Colleges status to offer a four-year Bachelor of Education degree (Kokutse, 2018). Prior to the 2018/2019 academic year, the Colleges of Education awarded diploma qualifications, while the universities awarded Bachelor of Education degrees and Post Graduate Diploma in Education PGDE/certificates in education. Previously, the University of Cape Coast and University of Education, Winneba, had the traditional mandate to prepare teachers to teach at various educational levels including the basic school level (Buabeng et al., 2019). But now, the University for Development Studies (UDS) and the University of Ghana, and other private universities have programs in teacher education (Newman, 2013; Ministry of Education, 2018a). In Ghana, there is one common educational curriculum run by the Colleges of Education. Buabeng et al. (2019) explains that while the CoE provides a yearlong school-based teaching practice in addition to a semester-long campus-based peer teaching, their colleagues offering education degrees in the University of Cape Coast (UCC) engage in a semester-long school-based teaching experience.

Senior High School Education in Ghana, from September 2017 became free (Tamanja and Pajibo, 2019). But the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) program was introduced in 1995 as part of efforts to fulfill UNESCO’s mission of free universal education for all by 2015 (Akyeampong, 2009). The FCUBE concentrated on enhancing the standard of instruction and learning, expanding educational access, and promoting the involvement of all school-age children, including the formation of local educational organizations to facilitate effective management of education (Agbenyega et al., 2005).

In 2015, Ghana developed an inclusive education policy with an overarching goal of fostering equitable access to education for all children. Inclusive education places emphasis on all aspects of education, including the pedagogy, school culture and environments that promote inclusion. The critical question is what to teach? Instruction has always been the decision of what to teach (curriculum) and how to teach (methods, materials, and activities). To achieve inclusive education, a curriculum reform is fundamental to achieve the necessary improvements in the quality of new teachers. Consistent with achieving improvement in the quality of teachers, the B.Ed. Curriculum in 2018, was written to reform education and the school curriculum. But how prepared are student teachers at Colleges of Education using the curriculum to promote inclusive education? In this paper, we use the social model of disability and anchored on the Sustainable Development Goals, to examine the preparedness of student teachers in meeting the needs of learners with diverse learning needs. Student teachers according to the Ministry of Education National (2018b) are individuals admitted to the Colleges of Education professionally trained and prepared to impart knowledge at the basic education levels.

Education has long been recognized as a global priority. For years, governments and other national and international stakeholders have focused their attention on making sure that all children can attend school, and they have backed up that commitment with funding. Persons with disabilities constitute about 15% of the world population, with about 80% of them living in countries of the global south, including Ghana (World Health Organization, 2011). Although the 2021 Ghana Population and Housing Census reports, that persons with disabilities in Ghana constitute about 8% (2,098,138) of the country’s population of 30,832,019 (Ghana Statistical Service, 2012), other reports show otherwise. The 2012 Human Rights Watch report indicates that over 5 million persons with disabilities live in Ghana (United States Department of States, 2017). The 5 million figure collaborates with the World Health Organization’s estimates that disability affects 15–20% of every country’s population (World Health Organization, 2018). The estimated number of persons with disabilities could be underestimated due the multiple layers of issues surrounding disability data collection, including attitudinal issues, disability definition, access to persons with disabilities, mode of reporting disability, that is, self-reporting (people may not report disability, especially those that are not very visible) some of which are concealed from public view due to stigma. The number of persons with disabilities is likely to grow as incidences such as chronic ailments, falls, injuries, conflicts, accidents, and aging continue to occur (Howard and Rhule, 2021; World Health Organization, 2021).

In 1994, UNESCO organized a World Conference on Special Needs Education in Salamanca, Spain (United Nations Educational, Scientific and cultural organization [UNESCO], 1994). The outcome of the conference called for students with disabilities to be educated within an inclusive education system. Consistent with Ghana’s commitment to ensuring that all children are given the opportunity to exercise their rights through inclusive education, it ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Article 6 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and the Dakar Framework for Action. Article 8 of the CRPD outlines measures that states parties could adopt to ensure that persons with disabilities are able to access education, including vocational training and lifelong learning. The SDG 4 aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” (United Nations [UN], 2015).

In in view of the above, there has been a rising awareness and activism for the inclusion of students with disabilities in regular mainstream classrooms, but the reality in many underdeveloped nations including Ghana is still a gloomy picture (Adera and Asimeng-Boahene, 2011). In fact, persons with disabilities still face challenges accessing education. The World Health Organization’s report on disabilities indicates that students with disabilities continue to have lower academic achievement than their peers without disabilities (World Health Organization, 2011). The education of students with disabilities is affected by attitudinal, pedagogical, institutional, informational, and environmental accessibility barriers (World Health Organization, 2011; Nakua et al., 2017; Braun and Naami, 2021). In a similar vein, the Government of Ghana has identified several factors that prevent persons with disabilities from attending school, including the general public’s negative perception of people with disabilities, physical obstacles, the lack of adequate facilities for assessments, and a rigid curriculum, inadequate planning by regular teachers for students with special needs (Government of Ghana, 2003).

In response to the challenges confronting the education of students with disabilities in Ghana, stakeholders have made concerted efforts in the education sector to embrace the ideals of inclusive education. In 2015, a policy on inclusive education was developed and adopted by the country toward fulfilling the aspirations of the 1992 constitution, which guarantees education as a fundamental human right. The overarching goal of the Inclusive Education (IE) policy is to ensure that schools identify children with different learning needs and adopt appropriate curricula that will meet their learning requirements (Ofori, 2018).

The policy defines inclusion in its broadest sense as ensuring access and learning for all children: especially those disadvantaged from linguistic, ethnic, gender, geographic or religious minority, from an economically impoverished background as well as children with special needs including those with disabilities. The policy (2015, p. 6) defines a child with special educational needs [SEN] as: “a child with disability, namely, visual, hearing, locomotor, and intellectual impairments.” But the policy extends the concept SEN to cover those who are failing in school, for a wide variety of reasons that are known to be barriers to a child’s optimal progress in learning and development.

Inclusion in the policy sets out to create an education system that is responsive to learner diversity and to ensure that all learners have the best possible opportunities to learn. One of the major features of the policy is that it adheres to universal design for learning. The principle of universal design in the policy offers learners multiple means of representation, expression, engagement, motivation and tapping into learners’ interest. The policy sets an agenda of child friendly schools, which implies schools in Ghana ought to look out for children; that is child-seeking and again they should focus attention on children; that is, schools should be child-centered. The policy also highlights a flexible curriculum in which schools: owe a responsibility to teach all children, exhibit no discrimination, utilize early intervention practices, ensure children’s participation, involve NGO’s, agencies, parents, and government, develop positive attitudes, conduct monitoring and evaluation, have a policy on Persons with Disabilities, and develop assessment practices.

The inclusive education policy acknowledges that: all children can learn irrespective of differences in age, gender, ethnicity, language, and disability. It further states that all children have the right to access basic education and that the education system should be dynamic to adapt to the needs of children. The Inclusive Policy also sets out to facilitate and enable education structures, systems, and methodologies to meet the needs of all children; and it is a good attempt to promote an inclusive society.

The inclusive policy of Ghana envisions the curriculum to be functional and consider the child’s cultural background, family/community resources, values, interests, aspirations, future goals, and opportunities. The policy further envisions professional development of teachers in pedagogical skills that meets the needs of children with special needs using child-centered approaches. The policy emphasizes that the curriculum should stress three key principles: Setting suitable learning targets, responding to pupil’s diverse needs, and overcoming barriers to learning for individuals and groups of pupils. The Policy further requires a multi-disciplinary assessment procedure at all levels of education to meet the needs of all pupils/students. In addition, alternative assessment procedures are seriously encouraged in all educational institutions to respond to the diverse needs of all learners.

The National Teacher Education Curriculum Framework (NTECF) sets out the four pillars and cross-cutting issues for the initial training of all teachers at the pre-tertiary level (Ministry of Education National, 2017). The Curriculum Framework consistent with the National Teachers’ Standards, NTC (2018), envisages to prepare new teachers to become effective, engaging, and inspirational in order to improve learning outcomes particularly at the basic school level. The Curriculum Framework is aimed at preparing competent teachers, and against which all Teacher Education Curricula, including the 4-year Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.), can be reviewed.

Teacher education training for basic and secondary schools are undertaken by initial teacher education institutions. The Colleges of Education award diploma qualifications, while the universities awards Bachelor of Education degrees and PGDE/certificates in education. Until recently, only the University of Cape Coast and University of Education, Winneba, offered university-level training but now the University for Development Studies (UDS) and the University of Ghana, as well as other private universities have programs in teacher education. The B.Ed. curriculum is used by Colleges of Education and other Universities offering education programs, as it was collaboratively produced by four teacher education universities with senior members of Colleges of Education (Ministry of Education National, 2017). The Curriculum Framework provides for teachers at the Universities offering Education and the Colleges of Education.

In 2012, Burnett and Felsman (2012) signaled the debate on post Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and pointed out the need to incorporate the SDGs in education, particularly in educational institutions. This view has gained currency among several scholars (Adams et al., 2018; Leal Filho et al., 2019; Stein et al., 2019). Tertiary institutions such as universities, Colleges of Education and nursing training institutions have been recognized as drivers toward achieving the SDGs particularly, SDG 4, considering the formative roles they play in molding the future of young people in countries (Machado and Davim, 2022). As Neubauer and Calame (2017) argues, the SDGs ought to be recognized as a unique opportunity to strengthen and intensify the dynamics of sustainability in higher education institutions all over the world. Without the commitment and involvement of tertiary institutions and in the case of training institutions such as Colleges of Education, perhaps the SDGs 4 may not be sustainably attained.

As noted by Calles (2020) the process of truly integrating the SDGs in tertiary institutions is sine qua non. Therefore, it is very important to assess how student teachers at the Colleges of Education in Ghana are integrating inclusive education consistent with SDG 4. This paper is framed on a case study methodology within the context of utilizing the social model of disability to examine the curricula of Colleges of Education in Ghana by investigating whether the student teacher is prepared enough to promote inclusive education.

In this paper, we used two analytical perspectives, the SDGs Goal 4 and the social model of disability, to understand whether or not student teachers are adequately prepared to deliver inclusive education in Ghana. The SDGs 4 set out to achieve inclusion and equality in education whilst the social model of disability provides us with the opportunity to identify barriers to inclusion and how to address them.

As part of the global community’s efforts to address social problems collectively, post the Millennium Development Goals era, the Sustainable Development Goals were birthed in 2015 (United Nations [UN], 2015). Goal four of the SDGs calls for inclusive and equitable quality education for all (Johnstone et al., 2020). Particularly, the target 4.5 calls for the elimination of gender disparities and inequities in education, specifically highlighting the need to ensure access to education for persons with disabilities. Target 4.a calls for the upgrading of educational facilities so that they are child-and disability-sensitive and to promote inclusive learning environments (United Nations [UN], 2015). One of the profound characteristics of the SDGS is the fact that all the goals are interconnected. The achievement of one goal leads to achieving another goal (Bentzen, 2015; United Nations Communications Groups [UNCG], 2017; United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2021).

UNESCO’s formulation of the Global Education Cooperation Mechanism (GCM) is at the heart of the interconnectedness and intersectional efforts on SDG 4. The GCM is built on the back of the 2015 Incheon Declaration and Education 2030 Framework for Action, which envisages a cooperation, monitoring and evaluation mechanism which has the Global Education Meeting (GEM) as the pivot of action (Mundial, Grupo Banco, and UNICEF, 2016). They contend that the GCM at best, is an ecosystem that consists of all global education actors that participates in the Global Education Meeting and have agreed to work cooperatively in support of SDG 4. The Global Education Meeting therefore involves joint platforms and initiatives developed by those global education actors in pursuit of SDG 4. The GCM is a global tool for education and a global multi-stakeholder mechanism for education in the 2030 Agenda, with the governance mechanism for the GCM, being the High-Level Steering Committee (HLSC) that is mandated to take strategic decisions and action for education (2022–2023 members). UNESCO organizes the Global Education Meetings in partnership with all global education actors toward achieving SDG 4 (Fontdevila and Grek, 2020). One of the key roles of the HLSC is to ensure the systematic alignment of approaches for education-related targets within the wider United Nations SDG structure. The HLSC therefore engages with the wider United Nations SDG structure at global and regional levels (Chaturvedi, 2021). In Ghana, a considerable milestone has been the integration of the SDGs into the medium-term development of Ghana. The government has found the SDGs to align with the current national vision of Ghana Beyond Aid, a long-term economic and social transformation strategy for national development (Republic of Ghana, 2019).

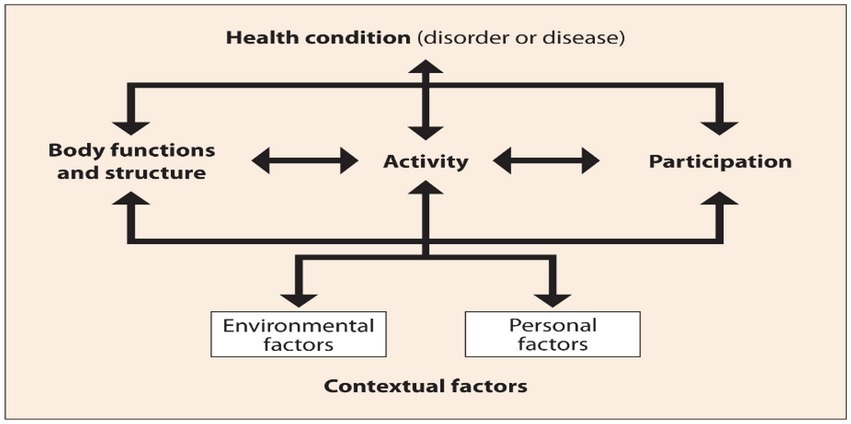

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides a comprehensive framework to describe health and health-related issues including disability. Disability under this framework is seen as an interface between body functioning, health conditions and contextual factors (World Health Organization, 2007). The ICF helps our understanding of the functioning of people with different disorders and their level of participation in activities as well as how contextual factors could facilitate or impact negatively on functioning. Figure 1 gives a pictorial illustration of how a particular health condition/disorder could affect the body functioning, activity and participation. The lower part of the diagram further illustrates the impact of contextual factors such as environmental (e.g., social, physical, transportation, and information barriers) and personal factors (e.g., education, gender, social background, and profession). For example, ICF combines both the social and the medical models of disability.

Figure 1. Interaction between the Components of ICF (World Health Organization, 2007).

The Social Model of Disability was proposed by advocates of the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) in 1976 (Shakespeare and Watson, 2010) which was later given credence to the works of scholars such as Oliver (1990), Oliver and Barnes (1998), Finkelstein (1980, 1988), Barnes (1991), and Shakespeare and Watson (2010). The proponents of the Social Model of Disability acknowledge that impairment could pose a limit to the functioning of persons with disabilities. However, they posit that persons with disabilities are disabled more by their environment and other processes than their perceived impairments (Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation [UPIAS], 1976). Examples of the disabling environment are societal structures, values, culture, environmental constructs (Geffen, 2013), inadequate access to healthcare, transportation, physical and institutional barriers (Barnes and Mercer, 2005; Naami, 2014). The social model stresses the removal of barriers to foster the inclusion of persons with disabilities in mainstream society (Shakespeare and Watson, 2010; Naami, 2014).

Applying the SDGs Goal 4 as an analytical tool inclusion and equality issues in the training of student teachers. The ICF and social model of disability, on the other hand, helped us identify barriers that could inhibit access of persons with disabilities to inclusive education in Ghana at the systemic (teaching training colleges) and unit (classrooms) levels and to identify what could be done to address issues at these levels.

A case study design was employed for this study. A case study design is a qualitative research approach which focuses on a detailed exploration of a phenomenon within its content. According to Yin (1981), p. 98, the decision to utilize a case study arises when “an empirical inquiry must examine a contemporary phenomenon in its real-life context especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”. We use a case study design when the researcher seeks to answer the “how” and “why” Questions and could be exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory (Yin, 1994).

There are two major case study designs: single-case study designs and multiple-case study designs. Yin emphasized that a single-case design could be selected because of its “criticalness, extremeness, typicalness, revelatory power, or longitudinal possibility” (Yin, 1994). We employed a single-case exploratory study design to deepen our understanding of the preparedness of Ghanaian student teachers to implement inclusive education in one of the Colleges of Education in Ghana. Colleges of Education are the settings where teachers are trained to develop required skills for effective inclusive education.

One College of Education in the southern sector of Ghana was the site for the study. The data sources were a face-to-face in-depth interview with the Quality Assurance Officer of the case and one site observation by the researchers. The interview with the key informant was done in English, conducted in the participants office, and lasted for an hour. See Appendix A for details of the interview guide. The site observation was taken to audit the accessibility of the physical environment.

We also reviewed the Four-Year Bachelor of Education degree curriculum (Developed by the University of Ghana), student reflective journal and the daily portfolio sheet. In year one, student teachers are required to do classroom observations to enhance their learning. During this period, they are required to keep a portfolio for the documentation of their field experience activities. Two forms, student reflective journal and daily portfolio sheet comprise of the portfolio, which is usually returned to their tutors for grading. The forms and the student handbooks were published by the government of Ghana under the Transformative Teacher Education and Learning (T-TELL), School Partnership Program with support from the British government.

SDGs Goal 4-Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (specifically, targets: 4.5, 4.6, 4.8), and the social model of disability guided the review.

We evaluated the four learning outcomes under the equity and inclusivity of the cross-cutting pillar. These outcomes were:

• Year one: awareness of self and learners as unique individuals

• Year two: teachers’ values and attitudes impacting on pupils’ learning, how diversity impacts on learning

• Year three: being a team member, co-teaching, and co-planning, planning for individualized instruction

• Year four: teaching all learners; learners, school, and community

The multiple data collection sources allowed data triangulations, increased rigor, and credibility of the study as well as a deeper and holistic understanding of the phenomenon (Yin, 2009). Data analysis was done by first transcribing the audiotaped interview into word format, then both inductive and deductive approaches were used for coding, pattern development, matching and building themes and subthemes. Both researchers independently coded the data to enhance the credibility of the study. We met to discuss and merged emerging codes and themes and subthemes. The components of the learning outcomes we analyzed in the light of the SDGs Goal 4 targets 4.5, 4.6, and 4.8 and the social model of disability (See Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

Awareness of oneself is vital to bracketing biases and prejudices against vulnerable populations, including persons with disabilities. For persons with disabilities, self-awareness is even more important given the socio-cultural and religious beliefs and practices that marginalize and discriminate against them and the resultant negative attitudes, stigma, discrimination, and exclusion and of persons with disabilities in all spheres of life (Kassah et al., 2012; Adjei et al., 2013; Dugbartey and Barimah, 2013; Naami, 2019).

The curriculum of the Colleges of Education in Ghana emphasis on the need for student teachers to reflect on their own beliefs and biases to enhance acceptance and conscientious efforts toward accommodating learners with disabilities to increase their inclusion. However, disability is not mentioned in the four learning outcomes of the equity and inclusivity of the cross-cutting pillar and their targets. The SDGs Goal 4.5 explicitly mentions persons with disabilities.

By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations.

This assertion is also emphasized in Article 24 of the CRPD. It is important that persons with disabilities are explicitly mentioned in targets and indicators to ensure that their needs are adequately addressed. It is noteworthy that disability is listed on the observation checklist and reflective journals of student teachers as part of their preparedness on the equity and inclusivity outcome.

We asked our key informant about how they teach students to self-reflect. See response below:

Whatever course that they take, we have components of misconceptions. For example, in math, when you are teaching math, you will let them know that these and that are some of the misconceptions. So, when they go out, they will observe the teacher to see if they are exhibiting these qualities.

We wanted to know more about how the student teacher is taught to reflect on disability. So, we probed further and the narrative was:

Yes, for example, so when you go to the school, we want you to try and see if you can find a child with special needs. Once you find one, you do your possible best to know the causes of the disability or how the person is being helped throughout his or her stay in the school…We specifically ask them to identify a child with the disability and even how the facilities and resources in the school support the child.

Obviously, we did not get adequate information about how the student teacher is prepared on the equity and inclusivity outcome.

In year two, the student teachers are required by the curriculum to imbibe knowledge on values and attitudes that has the potential of impacting learning. The student teacher is also expected by the curriculum to recognize what makes him/her an “inclusive teacher.” The observation checklist requires student teachers to identify traits of professionalism of their mentor teachers compared with theirs. Although this is a good attempt, it does not adequately address the end goal of being an inclusive teacher. Disability inclusiveness requires care and proper planning, but that is not emphasized in the curriculum of Colleges of Education in Ghana.

The teacher in the observation checklist can indicate that he/she is an inclusive teacher but prejudices and discrimination against persons with disabilities could cloud their self-consciousness about persons with disabilities. Attitudinal barriers are cited as major barriers to the inclusion of persons with disabilities in all spheres of life in Ghana (Kassah et al., 2012; Adjei et al., 2013; Dugbartey and Barimah, 2013; Naami, 2014). The observation checklist and reflective journals do not make enough room for student teachers to self-reflect on disability, which could be a barrier to the education of persons with various forms of disabilities. Thus, there should be more exercises to enable the student teachers to strengthen their reflection on disability to improve acceptance of persons with disabilities.

Also, the B.Ed. curriculum tasks student teachers to “Identify school and student characteristics that act as barriers to learning.” However, this statement is problematic as it is a wrong premise to understand barriers to learning for learners with disabilities. The proponents of the social model of disability contest that a student’s personal characteristics such as having an impairment is not the major impediment to learning, but barriers created by schools and society (World Health Organization, 2011; Nakua et al., 2017; Braun and Naami, 2021). Rather, impairment should be considered to enable provision of suitable accommodation for learners with disabilities. Assuming there is a learner with a mobility disability who uses a wheelchair in a school, will his/her characteristic of having an impairment be considered the barrier or some known access barriers such as storey building without elevators and staircase without accessible ramps? Of course, the known architectural barriers are the impediments as postulated by the social model of disabilities.

Further, the student teachers in year three are tasked to “identify learners who struggle to overcome barriers.” The student reflective journal and the observation checklists identify barriers to learning. The findings relating to the equity and inclusivity cross-cutting pillar of the curriculum is that emphasis is placed more on gender rather than disability inclusion. For example, in observing how a lesson is taught in week three of the student teacher observation checklist, the students are asked to identify “How many girls and boys were called by the teacher to answer questions in class?” and “How did the teacher react to boys and girls differently if their responses to a question was not right?” These two questions run through most of the weeks’ classroom observation. Although the students are also asked to find out if there were students with learning needs in the classroom, and whether the teacher provided support and the kind of support provided. We suggest that questions on disability are directly asked. For example, “Did the teacher ask learners with disabilities questions, and how did the teacher react to their responses?” This will help identify the teacher’s perceptions, including biases and prejudices against learners with disabilities.

It is worth mentioning that the student observation checklist listed a section on students with special needs. But the section seems to relate more to learners with learning difficulties. In fact, the entire Colleges of Education in Ghana curriculum seems to focus on students with learning difficulties. But the curriculum does not adequately address other categories of learners with disabilities who may require other forms of support as stated in the inclusive education policy. The policy (Ministry of Education, 2015: p. 6) defines a child with special educational needs [SEN] as: “a child with disability, namely, visual, hearing, locomotor, and intellectual impairments.” Throughout the curriculum and other auxiliary documents, there are phrases and statements such as “How much time was spent helping this student?” “Did the teacher spend time helping them” “Did the student(s) with learning needs successfully complete the activities/tasks assigned in the lesson?” These questions amply testify that the focus of curriculum and other auxiliary documents are on learners with learning difficulties to the neglect of other categories of disabilities.

It must be noted that, although the student observation checklist contains some items on disability, the students were not required, in their reflective journals, to reflect on leaners with disabilities, their learning needs, and how they could be addressed to increase participation. Unlike gender which was given much attention and detailed reflection in the Colleges of Education curriculum. For example, in week five the learning activity for student teachers requires “Observation of how socio-economic, cultural and linguistic backgrounds influence the way learners (a boy and a girl) learn.” The statement above does not recognize disability as one of the backgrounds that influences learning. It further does not recognize learners with disabilities as a targeted category for student reflection. The student teacher is required to reflect on seven questions listed under this theme but none of them captures disability. Ironically, the final question suggests the above reflections would have been helpful to increase disability sensitivity and inclusion. That the student teacher reflection is aimed at increasing their disability sensitivity and inclusion is fallacious.

The Curriculum College of Education in Ghana also recognizes effective class management as sine qua non for classroom participation. Thus, there are questions regarding participation on the student teacher checklist which states that: “Did the teacher encourage students to actively participate in the lesson? If so, what were some of the teacher’s actions that seemed to promote or not promote participation?” These questions aim at understanding how the teacher manages the classroom environment. However, it is equally important to find out whether what the teacher does promotes participation or alienates others. Oftentimes we incautiously do things that exclude persons with disabilities in group settings. It could be an ice breaker or other warming up exercises that could exclude learners with disabilities. For instance, some Ghanaian teachers utilize proverbs and stories to contextualize their messages and some of these are negative toward persons with disabilities and teachers unconsciously make their statements without knowing that they are hurting some learners in the classroom. Similarly, it is common for teachers to use illustrative examples on the board or PowerPoint slides and ask students to see even though they have students with visual impairments. This has the potential of influencing the learning experience of such students in the classroom. And since the student teachers are required to “Recognize how the teacher is a key influence on a learner’s self-esteem and, as a consequence, their learning potential,” there is the need for student teachers to be grounded in disability awareness to understand persons with disabilities, their issues and needs and how best they could be helped.

The SDGs target 4.8 outlines the need to build and upgrade educational facilities that are disability sensitive. The curriculum of Colleges of Education in Ghana rightly states the need to identify barriers to learning and working with stakeholders to address these barriers, which is also listed in the student reflective journals. Given that persons with disabilities have been marginalized in all spheres of life, including their families and caregivers (Naami, 2019), conscientious efforts must be made to ensure that persons with disabilities/organizations of persons with disabilities or individuals/organizations that have the capacity to represent them are at the decision-making table to ensure that their needs are adequately addressed (Agyire-Tettey et al., 2019).

The student teacher in the first week of the supported teacher school placement are required to reflect on the school environment. They are supposed to identify school facilities (e.g., football field, toilet, office space, tennis court, buildings etc.), but not the accessibility of these facilities. The key informant the affirmed that students are required to identify school facilities:

When they go to the schools, they have to know the history of the partner schools and the facilities that are in the schools that will support teaching and learning. They also observe some of the qualities of the classroom teacher.

However, when we prob. further about the omission of an important aspect of school facilities, which is accessibility, from the student reflective portfolio, he made these remarks:

I am very happy you brought this up. So, it’s good that you are bringing some of these things out. As the quality assurance officer of this particular institution, these are some of the questions I ask my coordinators. Yes, this is what we want the students to know.

He further made a remark, which we also observed on a visit to that College of Education. He noted that: “For example, go to the new schools, yes, we are building nice laboratories, but they are not accessible for learners and student teachers with disabilities.” From our observation, the entire school environment was not accessible. There were storey buildings with no elevators, most of the entrances to the buildings were inhibited with steps and not ramps. Other building facilities were ramped, but the ramps were not accessible. All these barriers could inhibit access of persons with disabilities in the school and impact on their learning. The barriers also do not allow of first-hand experiences of inclusive education.

Also, emphasis was place more on the classroom environment, which is good. Access of the surroundings of the classroom and school facilities should be target for reflection given that inaccessible school environment affects learning outcomes (Moriña and Morgado, 2018; Braun and Naami, 2021). The school and its environment must be safe and accessible for all learners. In addition, the curriculum requires student teachers to find out if there are other learning resources apart from computer(s). In their observation checklist, it is important that the students also identify whether what they identify are accessible to all learners particularly, persons with disabilities. For example, in some schools at the kindergarten level televisions are used to aid teaching. How do learners with visual and hearing impairment benefit from these forms of learning if resources do not have features of alternative formats (subtitles/captions, narrations) for these learners? So, the student teacher could identify a television as a resource for learning, but their reflection report does not create room for them to report on whether the resource is beneficial to learners with disabilities.

In this paper, we have examined the preparedness of student teachers in Colleges of Education in Ghana in respect of the curriculum being delivered toward achieving inclusive education. Our analytical tools, social model of disability and the SDGs goal 4 were synergistic, which allowed for comparative analysis. We established that the curriculum and auxiliary teaching materials do not adequately address leaners with disabilities and their needs. The school environment, the classroom, lessons, class management and assessment are all limited regarding inclusivity of learners with disabilities.

We conclude that the student teacher has not been given enough opportunity to reflect on their values, beliefs, biases, and attitudes toward learners with disabilities to develop appreciation of learners with disabilities and to be sensitive toward them. We, therefore, recommend the need for student teachers to be grounded in disability issues in order to understand learners with diverse disabilities, their unique needs and how best they could help them. Disability should clearly be mentioned in the curriculum and the learning outcomes of the equity and inclusivity cross-cutting pillar and their targets as well as auxiliary materials of Colleges of Educations in Ghana. To achieve inclusive education, it is imperative that conscientious efforts are made to ensure that disability is mainstream, alongside other vulnerability/diversity variables, such as gender.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

AN managed the project, including research planning, methodology, the design of the research instruments, fieldwork, data analysis, writing of results and assembled, wrote, and edited the first draft of the manuscript. KM contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, wrote the introduction section and assisted with the formulation, and editing of the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1056630/full#supplementary-material

Adams, R., Martin, S., and Boom, K. (2018). University culture and sustainability: designing and implementing an enabling framework. J. Clean. Prod. 171, 434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.032

Adera, B. A., and Asimeng-Boahene, L. (2011). The perils and promises of inclusive education in Ghana. J. Int. Assoc. Spec. Educ. 12, 28–32.

Adjei, P., Akpalu, A., Laryea, R., Nkromah, K., Sottie, C., Ohene, S., et al. (2013). Beliefs on epilepsy in Northern Ghana. Epilepsy Behav. 29, 316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.07.034

Agbenyega, J. S., Deppeler, J., and Harvey, D. (2005). Attitudes towards inclusive education in africa scale (ATIAS): an instrument to measure teachers' attitudes towards inclusive education for students with disabilities. J. Res. Dev. Educ. 5, 1–15.

Agyire-Tettey, E. E., Naami, A., Wissenbach, L., and Schädler, J. (2019). Challenges of Inclusion: Local Support Systems and Social Service Arrangements for Persons with Disabilities in Suhum, Ghana: Baseline Study Report.

Akyeampong, K. (2009). Revisiting free compulsory universal basic education (FCUBE) in Ghana. Comp. Educ. 45, 175–195. doi: 10.1080/03050060902920534

Barnes, C. (1991). Disabled People in Britain and Discrimination: A Case for Anti-Discrimination Legislation. London: Hurst Co.

Barnes, C., and Mercer, G. (2005). The Social Model of Disability: Europe and the Majority World. Leeds: Disability Press.

Barrett, P., Treves, A., Shmis, T., and Ambasz, D. (2019). The Impact of School Infrastructure on Learning: A Synthesis of the Evidence, Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

Bentzen, L. (2015). The importance of the SDGs. Available at: https://www.ntu.eu/news-archive/the-importance-of-the-sustainable-development-goals/ (Accessed May 3, 2022).

Braun, A. M. B., and Naami, A. (2021). Access to higher education in Ghana: examining experiences through the lens of students with mobility disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 68, 95–115. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2019.1651833

Buabeng, I., Ntow, F. D., and Otami, C. D. (2019). Teacher Education in Ghana: Policies and Practices. J. Curr. Teach. 9, 86–95. doi: 10.5430/jct.v9n1p86

Burnett, N., and Felsman, C. (2012). Post-2015 Education MDGs. London: Results for Development Institute en Overseas Development Institute.

Calles, C. (2020). ODS y educación superior. Una mirada desde la función de investigación. Revista Educación Superior y Sociedad (ESS) 32, 167–201. doi: 10.54674/ess.v32i2.288

Chaturvedi, S. (2021). Evolving Indian strategy on SDGs and scope for regional cooperation. South and South-West Asia Development Papers, 21–01.

Dugbartey, A. T., and Barimah, K. B. (2013). Traditional beliefs and knowledge base about epilepsy among university students in Ghana. Ethn. Dis. 23, 1–5.

Finkelstein, V. (1988). To deny or not to deny disability. Physiotherapy 74, 650–652. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(10)62916-1

Fontdevila, C., and Grek, S. (2020). “The construction of SDG4: reconciling democratic imperatives and technocratic expertise in the making of global education data?” in World Yearbook of Education 2021. eds. S. Grek, C. Maroy, and A. Verger (Milton Park: Routledge), 43–58.

Geffen, R. (2013). The Equality Act 2010 and the Social Model of Disability. London: Chartered Society of Physiotherapy London.

Ghana Statistical Service. (2012). “2010 Population and Housing Census: Summary Report of Final Results ”. Accra: Sakoa Press Ltd, Accra, Ghana.

Government of Ghana. (2003). “Policies, targets, and strategies” Education Strategic Plan 2003–2015 May. Vol. 1. Ghana: Ministry of Education. Available at: http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Ghana/Ghana%20Education%20Strategic%20Plan.pdf (Accessed July 28, 2022).

Howard, H. A., and Rhule, A. B. (2021). Socioeconomic factors hindering access to healthcare by persons with disabilities in the Ahanta west municipality, Ghana. Disabil. CBR Inclus. Dev. 32:69. doi: 10.47985/dcidj.419

Johnstone, C. J., Schuelka, M. J., and Swadek, G. (2020). “Quality education for all? The promises and limitations of the SDG framework for inclusive education and students with disabilities” in Grading Goal Four. ed. A. Wulff (Leiden: Brill), 96–115.

Kassah, A. K., Kassah, L. L., and Agbota, T. K. (2012). Abuse of disabled children in Ghana. Disabil. Soc. 27, 689–701. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.673079

Kokutse, F. (2018). University-Level Upgrade for Teacher-Training Colleges. London: University World News, The Global Window on Higher Education.

Leal Filho, W., Shiel, C., Paço, A., Mifsud, M., Ávila, L. V., Brandli, L. L., et al. (2019). Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Produc. 232, 285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.309

Machado, C., and Davim, J. P. (2022). Higher Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Ministry of Education. (2015). “Inclusive education policy.” Available at: http://www.voiceghana.org/downloads/MoE_IE_Policy_Final_Draft1.pdf (Accessed November 25, 2022)

Ministry of Education. (2018a). The National Teacher Education Curriculum Framework, (NTECF): The Essential Elements of Initial Teacher Education. Ghana: Ghana Assembly Press.

Ministry of Education. (2018b). National Teachers’ Standards Guidelines for Ghana: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike. Available at: www.t-tel.org/hub.html

Ministry of Education National (2017). Teachers’ Standards for Ghana: Guidelines. Published by the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike International. Available at: www.t-tel.org/hub.html (Accessed June 30, 2022).

Moriña, A., and Morgado, B. (2018). University surroundings and infrastructures that are accessible and inclusive for all: listening to students with disabilities. J. Furth. High. Edu. 42, 13–23.

Mundial, Grupo Banco, and UNICEF. (2016). "Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Lifelong Learning for All, UNICEF.

Naami, A. (2014). Breaking the barriers: Ghanaians’ perspectives about the social model. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 25, 21–39.

Naami, A. (2019). Access barriers encountered by persons with mobility disabilities in Accra, Ghana. J. Soc. Incl. 10, 70–86. doi: 10.36251/josi.149

Nakua, E., Yarfi, C., and Ashigbi, E. (2017). Wheelchair accessibility to public buildings in the Kumasi metropolis, Ghana. Afr. J. Disabil. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v6i0.341

Neubauer, C., and Calame, M. (2017). Global pressing problems and the sustainable development goals. High. Educ. World 6:81.

Newman, E. K. (2013). The upgrading of teacher training institutions to colleges of education: Issues and prospects. Afr. J. Teach. Educ. 3. doi: 10.21083/ajote.v3i2.2728

Ofori, E. A. (2018). Challenges and opportunities for inclusive education in Ghana. Unpublished thesis submitted to the University of Iceland.

Oliver, M., and Barnes, C. (1998). Social Policy and Disabled People: From Exclusion to Inclusion. Harlow: Longman.

Republic of Ghana (2019). Ghana’s 2019 SDGs Budget Report. Available at: https://mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/news/Ghana-SDGs-Budget-Report-July-2019.pdf

Shakespeare, T., and Watson, N. (2010). “Beyond models: understanding the complexity of disabled people’s lives” in New Directions in the Sociology of Chronic and Disabling Conditions. eds. G. Scambler and S. Scambler (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 57–76.

Stein, S., de Oliveira Andreotti, V., and Suša, R. (2019). Beyond 2015′, within the modern/colonial global imaginary? Global development and higher education. Crit. Stud. Educ. 60, 281–301. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2016.1247737

Tamanja, E., and Pajibo, E. (2019). Ghana’S free senior high school policy: evidence and insight from data. Edulearn19 Proc. 1, 7837–7846. doi: 10.21125/edulearn.2019.1906

Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation [UPIAS] (1976). Fundamental Principles of Disability. London: UPIAS.

United Nations [UN]. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (Accessed July 29, 2022)

United Nations Communications Groups [UNCG] (2017). SDGs in Ghana; why they matter and how we can help. Available at: http://UNCT-GH-SDGs-in-Ghana-Avocacy-Messages-2017%20(5).pdf (Accessed August 4, 2022).

United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], (2021). Ghana, our work on SDGs in Ghana. Available at: https://ghana.un.org/en/about/about-the-un (Accessed August 10, 2022).

United Nations Educational, Scientific and cultural organization [UNESCO]. (1994). World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Paris: UNESCO.

United States Department of States. (2017). Ghana 2012 human rights report. Available at: https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/204336.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2022).

World Health Organization. (2007). International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth Version: ICF-CY. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2011). World report on disability online. Available at: http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf (Accessed June 17, 2017)

World Health Organization. (2018). Disability and health: Fact sheet. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs352/en/ (Accessed May 15, 2022).

Yin, R. K. (1981). The case study as a serious research strategy. Knowledge 3, 97–114. doi: 10.1177/107554708100300106

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2nd Edn. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Keywords: Ghana, inclusive education, persons with disabilities, student teacher, teacher preparedness

Citation: Naami A and Mort KS-T (2023) Inclusive education in Ghana: How prepared are the teachers? Front. Educ. 8:1056630. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1056630

Received: 29 September 2022; Accepted: 16 January 2023;

Published: 23 February 2023.

Edited by:

William Nketsia, Western Sydney University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Gottfried Biewer, University of Vienna, AustriaCopyright © 2023 Naami and Mort. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Augustina Naami, ✉ YW5hYW1pQHVnLmVkdS5naA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.