95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 23 February 2023

Sec. Assessment, Testing and Applied Measurement

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1049680

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights in Assessment, Testing, and Applied Measurement: 2022 View all 21 articles

Introduction: Testing and assessment tools evaluate students’ performance in a foreign language. Moreover, the ultimate goal of tests is to reinforce learning and motivate students. At the same time, instructors can gather information about learners’ current level of knowledge through assessment to revise and enhance their teaching. This study aimed to investigate the effect of Dynamic Assessment on Iranian English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners’ speaking skills by considering language learners’ cognitive styles (field dependence and field independence).

Methods: For this purpose, 60 Iranian intermediate-level EFL female learners were selected through convenience sampling from three language institutes with similar teaching methods in Shiraz, Iran. The current study has a quasi-experimental design since randomization was impossible. First, the authors used the Nelson Proficiency test and interview to determine the participants’ proficiency level and speaking ability, respectively. Next, they took the group embedded figures test (GEFT) to determine the participants’ type of cognitive style (field dependence or field independence). Next, the participants were randomly assigned to two experimental (FD and FI learners with the dynamic assessment) and two control groups. Paired and independent-sample t-test were applied to analyze the data.

Results and discussion: Results revealed that although dynamic assessment was effective for both experimental groups, the Field-dependent group with dynamic assessment outperformed the other. Thus, it can be concluded that in addition to the dynamic assessment, language learners’ cognitive style can also play a vital role in increasing the assessment effectiveness. This type of assessment attracts instructors’ attention to learners’ potential to help the language learners gradually improve their performance. In addition, language institutes can introduce this new way of assessment in their advertisements and attract more students, leading to higher income and publicity for them.

While the need for learning English among English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners increases globally, “there is a growing demand for standardized English language proficiency assessments as an objective measure to gauge each student’s level of English language development” (Wolf and Butler, 2017, p. 3). Direct or indirect assessment is a topic of research in different studies as it can facilitate teaching and learning (Khoram et al., 2020; Saritas Akyol and Karakaya, 2021; Susilawati et al., 2022; Yusuf and Fajari, 2022). To address the increased need for appropriate measurement, assessment professionals and educators proposed dynamic assessment (DA) as a supplement for standardized testing, not a replacement for it (Lidz and Gindis, 2003). They believed that DA helps identify learners’ differences and use these differences to enhance teaching. In this regard, DA emerged as a reaction to the traditional or static tests, which considers language learning as the outcome of the interaction between learners and instructors and considers teaching a part of the assessment. In contrast, there is no attempt to change the examinee’s performance in the static assessment.

Assessing the language learners’ abilities in second language evaluation has undergone different changes and development in the form, type, structure, and objectives behind. Consequently, testing an EFL learner’s proficiency in speaking has been the primary concern of teachers who want to build practical criteria that can accurately assess oral reproduction because the evaluation is mostly subjective and many aspects of speaking such as pronunciation, pitch, tone, stress, intonation, sentence structures, and many other factors should be considered, so it is very important to have a practical, standard, and valid assessment procedure. Luoma (2004) believes that creating an instrument to evaluate concepts of accuracy and fluency and the learner’s mastery of a spoken language’s sound system and speech features is a difficult task. Test validation is another concern of the test developers to see if it serves as a reliable indicator of the level of student acquisition. And the other challenge is how to elaborate and describe pronunciation and its relevant standards (Luoma, 2004).

Hence, testing is needed to accompany teaching since it enables the teachers to change their teaching methods effectively to help different groups of students or individuals learn from their weaknesses by providing the details of their performances after the test (Heaton, 1989). Looking at different eras of language teaching in the past revealed that the emergence of each new approach and method in language teaching was followed by the appearance of a different language testing (Birjandi and Najafi Sarem, 2012). In addition, theorists and language teaching methodologists have developed language testing models, each appropriate for one language teaching model existing at a particular time.

Traditionally, the assessment was considered a way to gather information about learners’ current level of knowledge. For this reason, researchers have called such assessments static assessments, which dominated language testing for many years (Heaton, 1989; Teo, 2012). Indeed, these static assessments aimed to determine if the learners have met expected achievement or not which is reflected in summative and formative assessment. Summative assessment measures how much a learner has learned after completion of the instruction while formative assessment measures how a learner is learning during instruction which is closer to dynamic assessment. Yet, the limitation of static assessment was that it might not stimulate learners to become independent knowledge constructors and problem solvers. Testing and teaching interact in DA to make learning successful. In traditional testing, examiners cannot intervene in the testing process, whereas, in DA, examiners are actively engaged in intervention and improvement of the examinees’ cognitive outcome. According to Poehner (2008), instructors combine assessment and teaching as a single activity in DA. In contrast, they are distinguished from each other in traditional testing as different activities. He continued that in DA, the teacher tries to help language learners to complete a learning task.

On the other hand, Poehner (2005) believes that DA rejects the idea that any relation or interaction between examiners and examinees may negatively affect the reliability of the assessment. He claimed that DA assessment disregards the learners’ performance in completing a specific task and tries to identify how much and what assistance the learners need. Moreover, according to holistic diagnostic feedback intervention, providing individualized feedback to the learners needs the instructor’s expertise and skills. An experienced instructor in this issue can illicit and understand the students’ weak points and strong points through examination, so the examination is not just for identification of achievement level; most importantly, it is used to provide better learning for the students. For this reason, intervention between examiner and examinee (learners and teachers) contributes to the adjustment of the learners’ cognitive and metacognitive processes. And the students’ self-regulation and motivation will be enhanced through feedback-driven strategies and skills (Von der Boom and Jang, 2018). The Sociocultural Theory of the Russian psychologist Vygotsky (1978), who initially proposed and formalized the approach as the zone of proximal development (ZPD), supports DA. Vygotsky (1978) stated that assessment, apart from revealing what led to the learners’ poor performance, should provide solutions to remove problems and enhance the performance. According to ZPD, a more knowledgeable person can enhance the student’s learning by guiding them through a task slightly higher than his/her ability level. So, whatever the student becomes more competent, the teacher gradually stops helping until the student can perform the task independently and completely.

Accordingly, when learners interact with others with higher knowledge and expertise, their learning will be positively influenced. ZPD confirms what people can do with the help of a more knowledgeable person is much more than what they can do individually. Dynamic assessment is a blend of instruction and assessment that coincide in an educational setting. Instructors, who use DA assessment in classrooms, try to support and help the learners by asking questions and providing hints or prompts as mediation. Mediation refers to the assistance provided by the instructor to help the learners find the answer and learn simultaneously (Malmeer and Zoghi, 2014). The instructors’ interaction with learners is called reciprocity. Thus, reciprocity and mediation as two crucial elements in DA can show the learners’ progress and development in a specific area (Poehner and Lantolf, 2005).

As a recent approach, researchers have been interested in figuring out the effectiveness of DA on different language skills, especially speaking skills, which is the most significant one for EFL learners in communication with foreigners. However, in reality, many EFL learners are worried about their problems in oral production, and they always ask their instructors to help them improve their speaking skills (Rahmawati and Ertin, 2014).

However, besides the type of assessments, other factors can also fluctuate the effectiveness of this new approach, such as cognitive styles. Hence, it is acceptable to take into account field independence and field dependence cognitive styles while investigating the effectiveness of DA on EFL learners’ speaking skill development as justified in the next paragraph. There are different studies which focused on learning styles, including visual, auditory, read/write, and kinesthetic and questioned their effectiveness in teaching and learning (Rohrer and Pashler, 2012; Newton and Salvi, 2020); however, some other studies showed them effective (Dunn and Dunn, 1993; Bates, 1994; Cassidy and Eachus, 2000; Birzer, 2003; Dunn and Griggs, 2004; Cassidy, 2010), so there are challenges and controversies in this issue which necessitates further evaluation as they claimed that learning styles are culture- and context-specific. Moreover, the current study is going to shed light on the effectiveness of another aspect of learning styles which is FD/FI rather than the traditional and early classification of the learning styles.

Field dependence/independence are among the learning styles that may enhance students’ learning power and foster intellectual growth. The field-dependence/independence cognitive properties have continuously drawn researchers’ attention. In the mid-70s, many researchers concluded that field-dependence/independence might have a crucial role in second/foreign language learning (Tucker et al., 1976). FI individuals tend to view the world objectively and make decisions based on an internal synthesis of relevant factors. FI learners are independent thinkers who focus on details separate from the context. These learners are characterized by their analytical approach and abilities to problem-solving.

On the other hand, FD learners focus on the overall meaning and the whole field. They are more relational, and they need more external reinforcements to keep them motivated. FI learners prefer formal learning contexts that respond to their competitive learning style (Witkin and Goodenough, 1981), while field-dependent learners, who are socially oriented and readily distracted, learn from the environments based on their experiences. As a result, they are less competitive compared with field-independent learners (Wooldridge, 1995).

Considering the EFL context, many Iranian EFL teachers have mentioned that many students are active and try to speak in their classrooms. However, their performance on the test cannot show their actual ability and vice versa. Therefore, it is vital to integrate testing and teaching and not judge the learners based on one round of performance. Consequently, it is crucial to create practical tests for EFL learners since they learn something from the test. Thus, dynamic assessment as an innovative type of assessment for EFL learners can be beneficial as it involves both assessment and instruction.

Some researchers have studied only the field-dependent and field-independent cognitive styles and tried to explore if the participants of their studies were field-dependent or field- independent (Cárdenas-Claros, 2005; Chapelle and Fraiser, 2009; Motahari and Norouzi, 2015; Mahevelati, 2019). Although the researchers have conducted several studies to show the contributive effect of dynamic assessment and even FD/FI on EFL learners’ speaking skills, there is still room to highlight the learners’ cognitive styles. Thus, the present study is designed to investigate the effect of dynamic assessment on EFL field-dependent and field-independent learners’ speaking skill development. Moreover, some studies found FD and FI as effective to be considered in teaching and learning and some other studies found them ineffective. That is why the current study is going to evaluate and consider if they are found effective and make changes in the findings in our academic setting as FD and FI are context-specific and are officially called contextual factors (Kolb, 2015). As dynamic assessment is an interactive assessment which involves both teacher and learner, so the teachers’ awareness of the learners’ learning styles, here FD/FI, might play a role in teaching, learning, and assessment procedure. The primary purpose of this study is to examine the impact of dynamic assessment on EFL field-dependent and field-independent learners’ speaking skills. Thus, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

1. Does dynamic assessment affect EFL field-dependent learners’ speaking skills development?

2. Does dynamic assessment affect EFL field independent learners’ speaking skills development?

3. Does dynamic assessment affect the development of EFL learners’ speaking skills differently based on EFL learners’ cognitive styles?

Dynamic assessment deals with identification of the individual differences and their implications in instruction and assessment. Dynamic assessment emphasizes on the processes rather than learning products. This type of assessment reflects what Vygotsky (1978) stated, “it is only in movement that a body shows what it is” (Gauvain, 2001, p. 35). For example, moving pictures imply different meanings and understandings compared to still pictures. DA has both psychoeducational and sociocultural importance; therefore, it emerged when product-oriented and static assessment failed to provide satisfactory results, along with the demand for culture-bound instruments which can consider contextual differences, such as socioeconomic, educational, and individual differences in language acquisition (Lidz, 1987; Haywood and Tzuriel, 1992; Lidz and Elliott, 2000).

Therefore, this study follows the theoretical framework proposed by Vygotsky (1978), whose sociocultural theory emphasizes the role of social interaction. ZPD has been considered as a guide for interaction in second language classrooms (Davin, 2013) and it refers to the difference between “individuals’ actual ability and their potential for performing a task with assistance of a more capable individual.” In another word, what people can do with the help of a more knowledgeable person is much more than what they can do individually.

To date, multitudes of studies have been conducted to assess and explore the efficiency of DA on different aspects of language learning. Among the four language major skills, it seems speaking and oral productions of learners and components effective in speaking as vocabulary, in particular, have somehow received due empirical attention (Hayran, 2020; Uni, 2022). But Researchers such as O’Sullivan (2000), Poehner (2005), Hill and Sabet (2009), Davin (2013), Rahmawati and Ertin (2014), Karim and Haq (2014), Ahmadi Safa et al. (2016), Ebadi and Asakereh (2017), Hidri (2018), Minakova (2019), Safdari and Fathi (2020) have focused on the application of DA on learners’ speaking abilities. However, the present study finds room to address the effect of dynamic assessment on EFL field-dependent and field-independent learners’ speaking skill development, that is considering one more factor which might affect speaking and its assessment.

Hill and Sabet (2009) found that DA can enhance language learners’ speaking skills while being an optimal means to assess the development of speaking skills. However, Ebadi and Asakereh (2017) argued that they overlooked learners’ reciprocity and mediational patterns. These patterns are effective in obtaining reliable results. These studies show why the topic is challenging and should be investigated in different contexts.

Ableeva (2010) examined the impact of dynamic and traditional assessment on students’ French listening skills. She concluded that DA, “due to its reliance on mediated dialogue, illuminates the sources of poor performance that are usually hidden during traditional assessments, which are non-dynamic in nature” (Ableeva, 2010, p. iv). Furthermore, she pointed out that DA can detect which areas learners need further improvement. However, this study, similar to most other studies, did not consider cognitive styles and field dependence, and field independence. Thus, the current study tried to cover the ignored aspects.

Teo (2012) examined the impact of dynamic assessment on Taiwanese EFL learners’ reading skills. He applied DA to assess Taiwanese EFL college students’ reading skills and taught them via mediation. His study indicated that suitable dynamic assessment procedures were beneficial in promoting learners’ reading skills. However, this study just focused on reading skills, so there is no information about its effect on speaking skills as a productive skill in which many students have significant problems. That is why, the current study focused on speaking skills.

Malmeer and Zoghi (2014) attempted to determine the effect of dynamic assessment on Iranian EFL learners’ grammar performance. They had 80 students as participants assigned into two groups of 40 (teenagers and adults). The results showed a significant difference between the pretest and posttest mean scores of the grammar test. Their study confirmed that adult EFL learners outperformed teenage EFL learners. As grammar is not taught directly anymore, it would be more effective to focus on the effect of assessment on different skills through which grammar is also used and practiced in future studies. That is why the current research focused on the impact of assessment on speaking skills.

Hidri (2014) initially examined the traditional assessment of listening skills prevalent among sixty Tunisian university EFL students. He argued that the current static assessment suffers from limitations and therefore proposed DA in that educational context to explore the relevance and effect of DA on the views of both the test-takers and raters. His study maintained that the tertiary learners could learn better when they join others in learning activities, which helps them overcome the test items’ difficulty. He concluded that assessing the learners in a dynamic progress test can help “locate the areas of weaknesses in the language program or in the learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategies” (p. 15). This study also did not consider cognitive styles, field dependence, and field independence affecting the learners’ performance.

Constant Leung pointed out two approaches to DA: interventionist and interactionist. He maintained that “Interventionist DA tends to involve quantifiable preprogrammed assistance and is oriented toward quantifiable psychometric measurement” (Leung, 2007, p. 260). In this approach, standardized interventions can measure learners’ or groups of learners’ ability in using “predetermined guidance, feedback, and support.” Interactionist DA, however, “eschews measurement and is interested in the qualitative assessment of a person’s learning potential” (p. 261).

Ahmadi Safa et al. (2016) investigated the influence of interventionist DA, interactionist DA, and non-DA on Iranian English language learners’ speaking skills. They explored that interactionist DA improved the learners’ speaking skills compared to interventionist DA and non-DA. However, Ebadi and Asakereh (2017) claimed that quantitative studies could not thoroughly reveal the learners’ cognitive styles. They believed that qualitative studies best show learners’ cognitive development via interpretation. To fill this gap, the current study focused on quasi-experimental design instead of qualitative approach.

Hidri (2018) examined the progress of the speaking skills of the EFL students of Persian Gulf countries. First, he argued that many teachers are constrained in class since male and female learners cannot communicate and interact due to sex segregation. Next, book designers consider the sociocultural context of Arabian countries in developing textbooks, and many daily conversations and topics are omitted as inappropriate materials according to Arabic traditions and religion. Although this study investigated speaking skills similar to the current study, it focused on cultural constraints and did not consider field dependence and independence. So, the current study covered this ignored aspect.

Siwathaworn and Wudthayagorn (2018) explored the impact of DA on Thai EFL university students who were found to be low proficient in speaking English. Their results showed that DA had promising potential and helped learners improve their speaking skills significantly in different ways. This study and similar studies act as the basis of hypotheses in the current study which point to the positive effects of dynamic assessment on speaking skills.

O’Sullivan (2000) has identified physical/physiological, psychological, and experiential characteristics as three factors affecting language learners’ speaking test performance. The first group comprises unique measurements for examinees’ physical illness or disabilities. Second, test takers’ interests, emotional stage, motivation, and learning strategies. Finally, the third factor includes extrinsic impacts like former education, examination preparedness, examination experience, and communication experience. Siwathaworn and Wudthayagorn (2018) believed that DA could advocate all three sets of characteristics, and this is the reason why DA can assist learners in improving their speaking skills through speaking tests. This study fully supports the design of the current study. Thus the present study seeks to see if the dynamic assessment can affect learners’ speaking skills, as highlighted by Siwathaworn and Wudhayagorn.

The present study employed a quasi-experimental design with a non-dynamic pretest and posttest design. After conducting the pretest, the participants took the group embedded figures test (GEFT) to be designated as Field Dependent or Field Independent learners. Next, they were randomly assigned to two experimental and two control groups. Finally, a posttest was given to the learners in the last session lasting 15 min.

The study participants included Persian intermediate-level EFL female learners from 3 language institutes (Parsian language institute, Goftar language institute, and Boostan language institute) in Shiraz. Randomization requires much time and financial support; that is why it was not feasible. Instead, the participants were selected through convenience sampling and then homogenized using the Nelson language Proficiency Test (Brown et al., 1993). To ensure homogeneity of the participants, the authors selected 60 participants, equally distributed between three institutes, among 120 test-takers whose score was one standard deviation below and one standard deviation above the mean, as the study samples. A standard deviation close to zero indicates that data points are close to the mean, whereas a high or low standard deviation indicates data points are respectively above or below the mean. That is why the scores having 1 SD above and below the mean were chosen to ensure the selection of intermediate learners and high and low scores were excluded. The participants’ age range was 19–32 years. Fifteen learners were undergraduate students at university, 10 were high school students, and 7 had diploma. Moreover, those who had extremely high or low scores were excluded. Then, they were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups. The researchers decided to work on the intermediate level due to two reasons. First, based on their experience, most language learners concerned about finding a way to improve their speaking skills had intermediate levels. Second, more intermediate language learners were available in the institutes where the researchers decided to carry out their study.

The Top-Notch 3A student book (Saslow and Ascher, 2015) was used as the course material. Some researchers evaluated the Top-Notch series (Rezaiee et al., 2012; Alemi and Mesbah, 2013; Davari and Moini, 2016). They found that the series provides many interactions opportunities for EFL learners accompanied by positive and unbiased visual images. Many institutes in Shiraz, Iran, used this book as it consists of conversations and vocabularies which are practical for people who want to learn how to communicate with foreigners.

First, the Nelson 350A Language Proficiency test (Fowler and Coe, 1976) was administered to the students to specify their level of proficiency and ensure the homogeneity of the sample. This test has a 50-item multiple-choice section with one close comprehension passage along with vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation sections. It is a highly valid test whose validity and reliability have been estimated several times by Iranian researchers (Shahivand and Pazhakh, 2012). Next, the researchers applied the IELTS speaking skills test and rating scale to measure the students’ speaking skill level at the beginning and end of the semester. It has three phases which last for 15 min. The first phase includes short questions and answers to make the candidate comfortable and familiar with the candidate. In the second phase, the candidate speaks on a specific topic for 2–3 min, and in the third phase, a two-way discussion about the subject between candidate and interviewer happens. The rating scale covers fluency, coherence, lexical resources, and pronunciation. Different researchers checked the validity and reliability of the test (Karim and Haq, 2014). Then, the authors administered the group embedded figures test (GEFT) developed by Witkin et al. (1971) to classify the participants into Field dependent and Field Independent learners. It has strong validity and reliability (Witkin et al., 1971). Pearson correlation coefficient (test-retest method) showed acceptable reliability for this test (r = 0.82). Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha also showed a reliability coefficient of 0.87 which is quite acceptable.

The GEFT has three parts. The first part has seven items, and every one of the following two parts has nine questions. Part one is just for practice, so the number of simple figures correctly selected in parts two and three determines a participant’s total score. Part one has a 2-min time limit followed by a 5-min time limit for parts two and three. Participants are to trace the simple figure embedded in the complex one. Raw scores range from 0 to 18, upper than 11.4 are identified as FI and the lower 11.4 as FD (Witkin et al., 1971).

The participants presented a short talk (10–15 min) to determine their speaking skills according to the IELTS speaking test rating scale. Considering IELTS speaking test rating scale, all 60 students had a band score of around three, so all 60 students were identified as homogenous in terms of their speaking skills and were included in the study.

Subsequently, these 60 students sat for the GEFT to find out which type of cognitive style each one owned. According to the GEFT scores, the students were divided into field-dependent and field-independent groups. Later, the researchers divided the participants into different experimental and control groups randomly. As dynamic assessment needs careful attention and is more practical for a small number of participants, 60 participants were divided into two experimental and two control groups. In addition, each experimental and control group involving 15 students was divided into classes of five students. Three of the classes were run by the dynamic assessment on Field dependent learners, while another three classes were run using the dynamic assessment on Field Independent learners, another three classes used the conventional method, communicative language teaching (CLT), on Field Dependent learners, and the last three classes used the conventional method (CLT) with Field Independent learners.

Then, the teachers applied DA for 12 sessions (12 weeks) providing the students with flexible mediation in a dialogue between the teacher and the learner. Each session lasted for 90 min. However, the control group students received traditional and communicative language teaching, although the learners were divided into field-dependent and field-independent control groups. They received the same material. CLT provides the students with real student-student and student-teacher communication, but the teacher will not provide feedback as it is done in dynamic assessment.

In the end, the participants took a non-dynamic posttest to see the effect of the treatment sessions on them. The pre and posttests were codified based on the IELTS rating scale to measure the students’ speaking skills. To ensure the reliability of the scores, the authors asked two raters to score the participants’ speaking skills to measure the inter-rater reliability to avoid the subjectivity of scoring as much as possible.

The collected data through non-dynamic interviews were analyzed using SPSS software version 18. First, to understand whether there exists a significant difference between the Field dependent and Field independent groups, the authors ran an independent t-test as we have just one dependent variable and one independent one. Subsequently, the authors ran one independent t-test between each experimental group and its control group to ensure the effectiveness of the treatment. Finally, Pearson Correlation analysis was carried out in pre and posttest between the two raters’ scores to ensure the reliability of their given scores.

Pearson Correlation analysis showed agreement between two raters in pre-test (r = 0.82, sig. = 0.000) and post-test (r = 0.84, sig. = 000) in speaking skills test. So the rating of the scorer is considered reliable and acceptable.

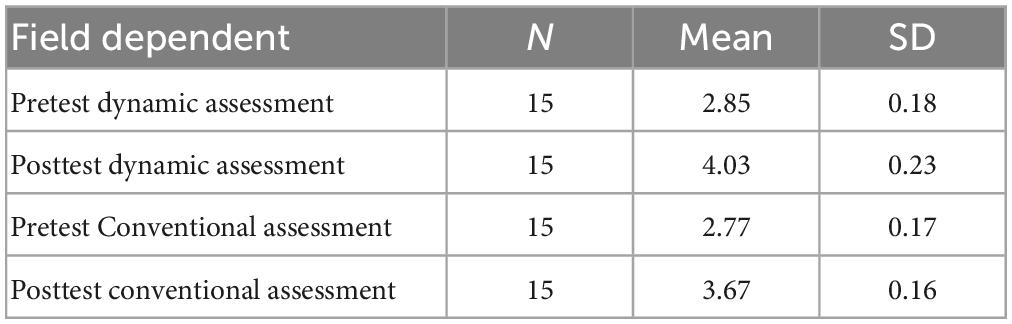

The following table shows descriptive statistics for the students’ performance in pretest and posttests in both dynamic and conventional assessment groups.

To answer the first question, pretest mean scores of both groups were analyzed to ensure the groups homogeneity in terms of speaking skills before treatment. As indicated in Table 1, the pretest mean score of the experimental group (M = 2.85, SD = 0.18) was slightly higher than the control group (M = 2.77, SD = 0.17) in which conventional assessment was conducted. An independent sample t-test was conducted to see if this difference is statistically significant. The results (t = 4.37, sig. = 0.102, p > 0.05) showed that this difference was not significant. It shows there was no significant difference between the two groups before treatment in terms of their speaking skills. When ensured about the homogeneity of the participants in both groups, the authors analyzed the post-test mean scores.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for pretest and posttest mean scores of Field Dependent learners with dynamic assessment and conventional assessment.

According to Table 1, Field dependent learners in the experimental group that received dynamic assessment (M = 4.03, SD = 0.23) outperformed Field Dependent learners in the control group that received conventional assessment (M = 3.67, SD = 0.16). To ensure this finding is statistically significant, the authors ran an independent sample t-test. Based on the results (t = 5.50, sig. = 0.000, Cohen’s d = 0.88), the difference between the mean scores of Field dependent learners who received dynamic and conventional assessment was significant (P < 0.05) with a large effect size and a statistical power of 95% calculated through Statistical Analysis System (SAS). In other words, Field Dependent learners with dynamic assessment significantly outperformed those who received a conventional assessment, which can lead the researchers to claim that the development of learners’ speaking skills in the experimental group was due to the treatment.

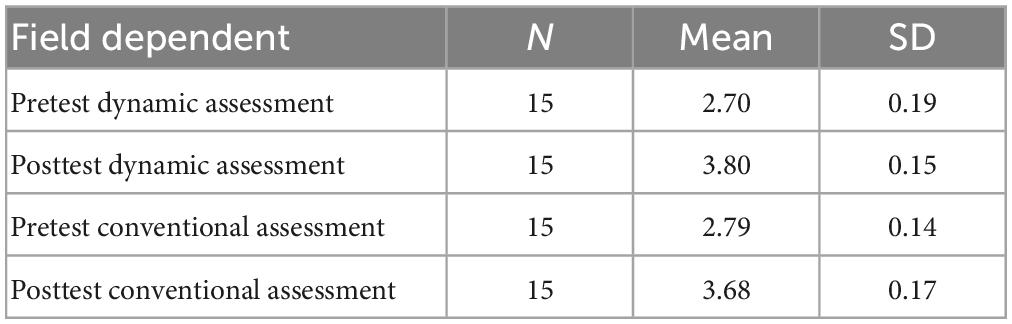

First, the difference between pretest mean scores of field-independent learners with dynamic assessment and conventional assessment was evaluated using an independent sample t-test to ensure homogeneity of both groups before treatment.

According to Table 2, although the pretest mean score of the field-independent learners in the conventional assessment group (M = 2.79, SD = 0.14) was slightly higher than those in the dynamic assessment group (M = 2.70, SD = 0.19) before treatment, independent sample t-test did not show this difference as significant (t = 2.61, sig. = 0.109, P > 0.05). So, it can be concluded that both groups were homogenous, having similar speaking skills before treatment.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for pretest and posttest mean scores of Field Independent learners with dynamic and conventional assessment.

Comparing posttest scores in Table 3 shows that Field Independent learners in the experimental group who received dynamic assessment (M = 3.80, SD = 0.15) outperformed the Field-independent learners in the control group that received conventional assessment (M = 3.68, SD = 0.17). To ensure this finding is statistically significant, the authors ran an independent sample t-test. The results (t = 2.14, sig. = 0.04, Cohen’s d = 0.83) illustrated that Field Independent learners with dynamic assessment significantly outperformed the control group that received conventional assessment on the posttest (P < 0.05), which can be seen as a piece of evidence for confirming this issue that the development of learners in the experimental group was due to the treatment. Large effect size and a statistical power of 92% calculated through statistical analysis system (SAS) confirmed the results.

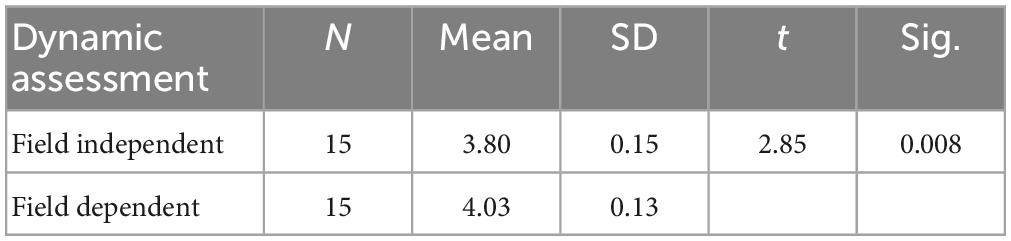

Table 3. Descriptive and independent sample t-test for posttest mean scores of field independent and field dependent learners with dynamic assessment.

As Table 3 illustrates, there was a difference in the posttest scores for Field Dependent learners (M = 4.03, SD = 0.13) and Field Independent learners who received dynamic assessment (M = 3.80, SD = 0.15). Field-dependent learners outperformed Field-independent learners. An independent sample t-test was applied to test if this finding is significant. According to the results, the Field-dependent learners with dynamic assessment treatment significantly outperformed the Field- independent learners with dynamic assessment (t = 2.85, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.90) with a large effect size and a statistical power of 88% calculated through SAS. These results suggest that although dynamic assessment is generally an effective way to help students improve their speaking performance, it is more beneficial for Field-dependent learners.

This study investigated the effectiveness of dynamic assessment on Iranian EFL Field Dependent and Field Independent intermediate learners’ speaking skills development. The two experimental instructional settings involved dynamic assessment for EFL Field Dependent learners and EFL Field independent learners separately. The first research question aimed to clarify whether the dynamic assessment is practical for improving field-dependent EFL learners’ speaking skills. Results revealed the effectiveness of dynamic assessment on Persian EFL Field Dependent learners’ speaking performance. Therefore, the answer to the first question was affirmative, leading to the efficiency of dynamic assessment on Persian EFL Field Dependent learners’ speaking skill improvement.

The second research question was to determine if the dynamic assessment can help EFL intermediate learners with field independence cognitive style improve their speaking skills. The results obtained from their pretest and posttest illustrated the usefulness of dynamic assessment on Persian EFL Field Independent learners’ speaking performance. Therefore, the answer to the second question was also affirmative, indicating the effectiveness of dynamic assessment on Persian EFL Field Independent learners’ speaking skill improvement.

These findings align with Siwathaworn and Wudthayagorn (2018), who claimed that dynamic assessment affects tertiary EFL students’ speaking skills. They tried to help the students improve their speaking skills in the elicitation limitation test task, where they were encouraged to repeat sentences. The results showed the positive effect of DA on the students’ speaking skills. However, Davin and Donato (2013) criticized that only selected learners will find an opportunity to react actively to teacher mediation when DA is practiced in the classroom, so this method “limits the cognitive engagement of a majority of students in benefiting from the teacher’s mediation.” They further pointed out that “due to time constraints and the large number of students in a classroom, classroom DA alone is effective for those students who actively participate, but it is not sufficient to promote and monitor the language development of every student in a classroom” (p. 6).

Minakova (2019) carried out an experimental study to determine the impact of DA in language development through standardized test preparation. Despite the growing consensus on the fruitfulness of DA, she highlights an important limitation in her study, as “it does not offer solutions for teachers who work with large groups of students. The mediation program implemented in the present study was based on the individual meetings with the mediator, and its outcomes are more relevant to private IELTS tutors” (p. 206).

Another researcher, Teo (2012), also revealed the usefulness of dynamic assessment on Taiwanese EFL learners’ reading skills. In another study, Poehner (2008) assessed the speaking skills of advanced French undergraduate learners. The results of his research agreed with this study which refers to the effectiveness of the dynamic assessment. His findings indicated that mediation, one of the significant parts of dynamic assessment, helped the learners better comprehend two tenses of imparfait and passé compose in French.

Ableeva (2010) was also another researcher who illustrated the effectiveness of the dynamic assessment. This researcher investigated the L2 listening comprehension ability of French university learners. These findings corroborate the results of many previous studies that confirmed the effectiveness of dynamic assessment in various instructional contexts (Lantolf and Poehner, 2011; Shrestha and Coffin, 2012; Teo, 2012; Nazari and Mansouri, 2014; Sadighi et al., 2018; Safdari and Fathi, 2020).

Finally, the findings revealed that dynamic assessment was more beneficial for Field Dependent learners, although Field-independent learners were not detached from the effectiveness of this treatment. Rassaei (2014) and Hoffman (1997) believe that this is because Field-dependent learners generally need guidance and assistance from the instructor and intend to interact with people. Furthermore, they add that field-dependent individuals take a holistic approach while under the influence of their surrounding context. In other words, Field-dependent learners are more successful in situations that need social sensitivity and empathizing with others. Consequently, dynamic assessment through interaction can be beneficial for them.

Furthermore, dynamic assessment in the mediation form of interaction provides a situation where the mediating agent, like the teacher, engages in a task with a learner and offers as much mediation as required to support the learner’s performance in an activity (Davin, 2013).

The results are aligned with the studies done by Rassaei, 2014, Niroomand and Rostampour, 2014, and Wapner and Demick (2014). They claimed that the degree of the effectiveness of different treatments on second language learners’ performance depends on their different cognitive learning styles (field dependence and field independence). So, these studies show that this learning styles as FD/FI still matters and should be considered to see if they affect the performance. Generally, depending on the situation and the kind of treatment, in some studies, Field-independent learners outperform field-dependent learners or vice versa. Therefore, in this study, as the dynamic assessment was more interaction and the teachers acted like assistants for language learners, Field-dependent learners with dynamic assessment treatment outperformed the other group. Therefore, the leaning style, in this study FD/FI should be controlled and considered in EFL in the future at least in the academic setting where the current study was conducted.

The findings of this study can benefit foreign language teachers, testers, and learners since foreign language teachers and testers will become aware of the effectiveness of a new way of assessment called dynamic assessment, which involves both assessment and instruction simultaneously. Thus, it can be beneficial in language teaching and help the learners improve their speaking skills. Moreover, the instructors and testers will notice whether EFL learners’ cognitive styles interfere with dynamic assessment’s effect on their speaking skills. New suggestions can be proposed with this method for improving the EFL learners’ speaking skills.

The reported results in this study maintain several implications to provide more effective teaching and learning perceptions. The results can make EFL teachers aware of dynamic assessment that involves instruction and assessment simultaneously. In other words, the instructors offer assistance to students while assessing them simultaneously. The teachers gain a clearer understanding of the language learners’ future by paying attention to language learners’ responses to the mediations.

Indeed, teachers become familiar with the benefits of dynamic assessment on EFL learners’ performance. This type of assessment attracts their attention to learners’ potential and leads them to help the language learners gradually improve their performance. On the other hand, language learners figure out their potential development and promote their language skills. In addition, language institutes can introduce this new way of assessment in their advertisements and attract more students, leading to higher income and publicity for them.

Minakova’s (2019) study corroborates both present and past studies, and she argues that her findings have crucial implications for educators. She furthers that “providing mediation during assessment allows them to uncover learners’ latent abilities instead of simply documenting their current achievements. In other words, DA explores how one’s performance is modifiable and what kind of mediation is needed to promote development within the learners’ ZPD” (p. 186). To sum up, the current study showed the effect of dynamic assessment in developing the learners’ speaking skills. Moreover, it showed that learners cognitive learning styles affect their performance when using dynamic assessment so cognitive styles as a type of individual difference among learners should be considered.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Both authors declared to have equally contributed in writing the manuscript and read and approved the final version of submitted manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

DA, dynamic assessment; EFL, English as a Foreign Language; GEFT, Group Embedded Figures Test; FD, field dependence; FI, field independence; ZDP, zone of proximal development; IELTS, International English Language Testing System; CLT, communicative language teaching; SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

Ableeva, R. (2010). Dynamic assessment of listening comprehension in second language learning, Ph.D. thesis. State College, PA: The Pennsylvania State University.

Ahmadi Safa, M., Donyaei, S., and Malek Mohamadi, R. (2016). An investigation into the effect of interactionist versus interventionist models of dynamic assessment on Iranian EFL learners’ speaking skill proficiency. J. Teach. English Lang. 9, 153–172.

Alemi, M., and Mesbah, Z. (2013). Textbook evaluation based on the ACTFL standards: The case of top notch series. Iran. EFL J. 9, 162–179.

Bates, T. (1994). Career development for higher flyer. Manag. Dev. Rev. 7, 20–24. doi: 10.1108/09622519410771763

Birjandi, P., and Najafi Sarem, S. (2012). Dynamic assessment: An evolution of the current trends in language assessment and testing. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2, 747–753. doi: 10.4304/tpls.2.4.747-753

Birzer, M. L. (2003). The theory of andragogy applied to police training. Policing 26, 29–42. doi: 10.1108/13639510310460288

Brown, J. A., Fishco, V. V., and Hanna, G. (1993). Nelson-Denny reading test: Manual for scoring and interpretation, forms G & H. Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Cárdenas-Claros, M. (2005). Field dependence/field independence: How do students perform in CALL based listening activities? Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

Cassidy, S. (2010). Learning styles: An overview of theories, models, and measures. Educ. Psychol. 24, 419–444. doi: 10.1080/0144341042000228834

Cassidy, S., and Eachus, P. (2000). Learning style, academic belief systems, self-report student proficiency and academic achievement in higher education. Educ. Psychol. 20, 307–322. doi: 10.1080/713663740

Chapelle, C., and Fraiser, T. (2009). Individual learner differences in call: The field independence/dependence (FID) construct. CALICO J. 26, 246–266. doi: 10.1558/cj.v26i2.246-266

Davari, S., and Moini, M. R. (2016). The representation of social actors in top notch textbook series: A critical discourse analysis perspective. Int. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 4, 69–82.

Davin, K. J. (2013). Integration of dynamic assessment and instructional conversations to promote development and improve assessment in language classroom. Lang. Teach. Res. 17, 1–38. doi: 10.1177/1362168813482934

Davin, K. J., and Donato, R. (2013). Student collaboration and teacher-directed classroom dynamic assessment: A complementary pairing. Foreign Lang. Ann. 46, 5–22. doi: 10.1111/flan.12012

Dunn, R., and Dunn, K. (1993). Teaching secondary students through their individual learning styles: Practical approach for grades 7-12. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Dunn, R., and Griggs, S. A. (Eds.) (2004). Synthesis of the Dunn and Dunn learning-style model research: Who, what, when, where, and so what? New York, NY: St. John’s University’s Center for the Study of Learning and Teaching Styles.

Ebadi, S., and Asakereh, A. (2017). Developing EFL learners’ speaking skills through dynamic assessment: A case of a beginner and an advanced learner. Cogent Educ. 4:1419796. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2017.1419796

Hayran, Z. (2020). Examining the speaking self-efficacy of pre-service teachers concerning different variables. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 90, 1–18. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2020.90.1

Haywood, H. C., and Tzuriel, D. (1992). Interactive assessment. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4392-2

Heaton, J. B. (1989). Writing English language test: Longman handbooks for language teachers. London: Longman Inc.

Hidri, S. (2014). Developing and evaluating a dynamic assessment of listening comprehension in an EFL context. Lang. Test. Asia 4:4. doi: 10.1186/2229-0443-4-4

Hidri, S. (2018). “Assessing spoken language ability: A many-facet Rasch analysis,” in Revisiting the assessment of second language abilities: From theory to practice, ed. S. Hidri (Midtown Manhattan, NY: Springer International Publishing), 23–48. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62884-4

Hill, K., and Sabet, M. (2009). Dynamic speaking assessments. TESOL Q. 43, 537–545. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00251.x

Hoffman, S. (1997). Field Dependence/Independence in second language acquisition and implications for educators and instructional designers. Foreign Lang. Ann. 30, 222–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.1997.tb02344.x

Karim, S., and Haq, N. (2014). An assessment of IELTS speaking test. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 3, 152–157.

Khoram, A., Bazvand, A. D., and Sarhad, J. S. (2020). Error feedback in second language speaking: Investigating the impact of modalities of error feedback on intermediate EFL students’ speaking ability. Eurasian J. Appl. Linguist. 6, 63–80. doi: 10.32601/ejal.710205

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, 2nd Edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Lantolf, J. P., and Poehner, M. E. (2011). Dynamic assessment in the classroom: Vygostkian praxis for L2 development. Lang. Teach. Res. 15, 11–33. doi: 10.1177/1362168810383328

Leung, C. (2007). Dynamic assessment: Assessment for and as teaching? Lang. Assess. Q. 4, 257–278. doi: 10.1080/15434300701481127

Lidz, C. S. (1987). “Historical perspectives,” in Dynamic assessment: An interactional approach to evaluating learning potential, ed. C. S. Lidz (New York, NY: Guilford), 3–34.

Lidz, C. S., and Elliott, J. (Eds.) (2000). Dynamic assessment: Prevailing models and applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Lidz, C. S., and Gindis, B. (2003). “Dynamic assessment of the evolving cognitive functions in children,” in Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context, eds A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev, and S. M. Miller (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511840975.007

Mahevelati, E. (2019). Field-dependent/independent cognitive style preferences of EFL learners in an implicit learning task from information processing perspective: A qualitative investigation. Int. J. Res. Stud. Lang. Learn. 8, 39–60. doi: 10.5861/ijrsll.2019.3009

Malmeer, E., and Zoghi, M. (2014). Dynamic assessment of grammar with different age groups. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 14, 1707–1713.

Minakova, V. (2019). Dynamic assessment of IELTS speaking: A learning-oriented approach to test preparation. Lang. Sociocult. Theory 6, 184–212. doi: 10.1558/lst.36658

Motahari, M. S., and Norouzi, M. (2015). The difference between field independent and field dependent cognitive styles regarding translation quality. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 5, 1799–2591. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0511.23

Nazari, B., and Mansouri, S. (2014). Dynamic assessment versus static assessment: A study of reading comprehension ability in Iranian EFL learners. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 10, 134–156.

Newton, P. M., and Salvi, A. (2020). How common is belief in the learning styles neuromyth, and does it matter? A pragmatic systematic review. Front. Educ. 5:602451. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.602451

Niroomand, S. M., and Rostampour, M. (2014). The impact of field dependence/independence cognitive styles and gender differences on lexical knowledge: The case of Iranian academic EFL learners. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 4, 2173–2179. doi: 10.4304/tpls.4.10.2173-2179

O’Sullivan, B. (2000). Towards a model of performance in oral language testing. Reading: University of Reading.

Poehner, M. E. (2005). Dynamic assessment of oral proficiency among advanced L2 learners of French. State College, PA: The Pennsylvania State University.

Poehner, M. E. (2008). Dynamic assessment: A Vygostkian approach to understanding and promoting second language development. Berlin: Springer.

Poehner, M. E., and Lantolf, J. P. (2005). Dynamic assessment in the language classroom. Lang. Teach. Res. 9, 233–265. doi: 10.1191/1362168805lr166oa

Rahmawati, Y., and Ertin, E. (2014). Developing assessment for speaking. Indones. J. English Educ. 1, 199–210. doi: 10.15408/ijee.v1i2.1345

Rassaei, E. (2014). Recasts, field dependence/independence cognitive style, and L2 development. Lang. Teach. Res. 19, 1–21. doi: 10.1177/1362168814541713

Rezaiee, A. A., Kouhpaeenejad, M. H., and Mohammadi, A. (2012). Iranian EFL learners’ perspectives on new interchange series and top-notch series: A comparative study. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 70, 827–840. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.128

Rohrer, D., and Pashler, H. (2012). Learning styles: Where’s the evidence? Med. Educ. 46, 634–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04273.x

Sadighi, F., Jamasbi, F., and Ramezani, S. (2018). The impact of using dynamic assessment on Iranian’s writing literacy. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 8, 1246–1251. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0809.21

Safdari, M., and Fathi, J. (2020). Investigating the role of dynamic assessment on speaking accuracy and fluency of pre-intermediate EFL learners. Cogent Educ. 7:1818924. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2020.1818924

Saritas Akyol, S., and Karakaya, I. (2021). Investigating the consistency between students’ and teachers’ ratings for the assessment of problem-solving skills with many-facet rasch measurement model. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 91, 281–300. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2021.91.13

Shahivand, Z., and Pazhakh, A. (2012). The effects of test facets on the construct validity of tests in Irania EFL students. High. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2, 16–20.

Shrestha, P., and Coffin, C. (2012). Dynamic assessment, tutor mediation and academic writing development. Assess. Writ. 17, 55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2011.11.003

Siwathaworn, P., and Wudthayagorn, J. (2018). The impact of dynamic assessment on tertiary EFL students’ speaking skills. Asian J. Appl. Linguist. 5, 142–155.

Susilawati, E., Lubis, H., Kesuma, S., and Pratama, I. (2022). Antecedents of student character in higher education: The role of the automated short essay scoring (ASES) digital technology-based assessment model. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 98, 203–220.

Teo, A. K. (2012). Effects of dynamic assessment on college EFL learners’ reading skill. J. Asia TEFL 9, 57–94.

Tucker, G., Hamayan, E., and Genesee, F. H. (1976). Affective, cognitive and social factors in second language acquisition. Can. Modern Lang. Rev. 32, 214–226.

Uni, K. (2022). Benefits of Arabic vocabulary for teaching Malay to Persian-speaking university students. Eurasian J. Appl. Linguist. 8, 133–142.

Von der Boom, E. H., and Jang, E. E. (2018). The effects of holistic diagnostic feedback intervention on improving struggling readers’ reading skills. J. Teach. Learn. 12, 54–69. doi: 10.22329/jtl.v12i2.5105

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wapner, S., and Demick, J. (2014). Field dependence-independence: Bio-psycho-social factors across the life span. New York, NY: Psychology Press. doi: 10.4324/9781315807218

Witkin, H. A., and Goodenough, D. R. (1981). Cognitive styles: Essence and origin. New York, NY: International University Press.

Witkin, H. A., Oltman, P., Raskin, E., and Karp, S. (1971). A manual for the embedded figures test. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Wolf, M. K., and Butler, Y. G. (2017). English language proficiency assessments for young learners. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315674391-1

Wooldridge, B. (1995). “Increasing the effectiveness of university/college instruction: Integrating the result s of learning style research into course design and delivery,” in The importance of learning styles: Understanding the implications for learning, course design, and education, eds R. R. Sims and S. J. Sims (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 49–67.

Keywords: dynamic assessment, field-dependent learners, field-independent learners, speaking skill, EFL

Citation: Kafipour R and Khoshnood A (2023) Effect of feedback through dynamic assessment on EFL field-dependent and field-independent learners’ speaking skill development. Front. Educ. 8:1049680. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1049680

Received: 20 September 2022; Accepted: 09 February 2023;

Published: 23 February 2023.

Edited by:

Gavin T. L. Brown, The University of Auckland, New ZealandReviewed by:

Zhe Li, Osaka University, JapanCopyright © 2023 Kafipour and Khoshnood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ali Khoshnood,  YS5raG9zaG5vb2RAcG51LmFjLmly

YS5raG9zaG5vb2RAcG51LmFjLmly

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.