- Center for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Introduction: Diversity is considered central to the capacity of higher education institutions to thrive in an increasingly diverse society. Accordingly, diversity policies are developed and initiated to benefit students from diverse backgrounds. However, little is known about how students themselves assess these diversity policies (student voice).

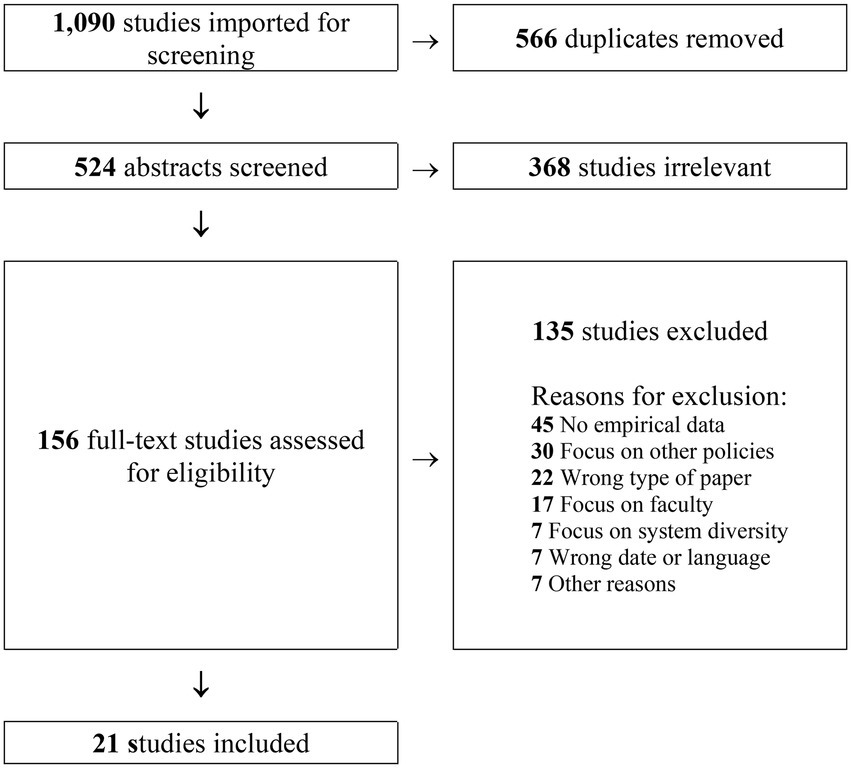

Methods: The systematic review described in this paper hence seeks to provide an overview of empirical evidence on student voice of diversity policies in higher education, looking thereby at corresponding studies published between 2000 and 2020. Of the 1,090 studies identified in the screening process, 21 were included in the final analysis.

Results: Two thematic strands emerged in the thematic analysis: diversity policies aiming at opening access to higher education and the representation of student voice.

Discussion: The review concludes with specific policy and research recommendations in this field.

1. Introduction

Diversity is considered central to the capacity of higher education institutions to thrive in diverse societies (Garces, 2014). Higher education institutions across the globe can be viewed as sites of diversity and social mixing, which endeavor to maximize the former and increase educational opportunities for all students (Plotner and Marschall, 2014). In recent years, researchers and policymakers have shown keen interest in the rates and conditions in which diverse student groups participate in higher education. Equal opportunities and social justice for all students that enable them to participate in higher education regardless of their background is a fundamental principle of higher education policymaking (Bastedo and Gumport, 2003).

Diversity is understood as a conceptual framework, which describes and connects dimensions such as socio-economic status, gender, sexuality, disability, or ethnicity in such a way that it reveals the complexity of experiencing social inequalities in everyday student life. Higher education institutions face diversity on an enhanced level since the opening of the sector for diverse and non-traditional students, demographic change as well as and the call for more social action on the tertiary level (e.g., access for refugee students). Diversity dimensions may lead to inequalities in access and inequalities of experience for diverse students. Diversity in this study is understood in its plurality of inequalities from the students’ perspectives, since a single dimension of diversity might lead to a simplification of lived student realities (intersectionality; Crenshaw, 1989; Byrne, 2006). Higher education institutions have, in response, developed diversity policies, which shape diversity management and institutional practice on campus (Arce-Trigatti and Anderson, 2019). Equal opportunities for all students require diversity policies, which guarantee affordable access and equal participation for diverse student populations (Bastedo and Gumport, 2003). Klein (2016) argues that measures derived from diversity policies can be relatively narrow in their scope and tend to focus only on certain identity characteristics of students, such as a migration background and ethnicity, rather than intersectional dimensions of diversity such as overlaps in ethnicity and social class, disability, or sexual orientation. Policy processes are criticized for their disconnect between planning and action or the distance between theory and practice (Iverson, 2012). Students have oftentimes in the history of higher education protested against a lack of inclusion, racism, discrimination, or the lack of action and structural transformation for diversity in higher education (Singh Sandhu et al., 2022). Recent policy processes like the Bologna process may support such structural transformation by, for example, establishing the objective of realizing “the societal aspiration that the student body entering, participating in and completing higher education at all levels should reflect the diversity of our populations” (London Communiqué, 2007, p. 5). Hence, social diversification of higher education is an explicit goal in some parts of the world, such as in Europe, as a consequence of the Bologna process (Goastellec, 2012).

Extensive research has been conducted on the educational benefits of diversity (e.g., Milem et al., 2005; Hurtado, 2007) and on strategies and policies intended to transform institutional culture (e.g., Valverde and Castenell, 1998). Studies also underline the significance of public policy in increasing access for diverse groups (Horn and Flores, 2003). However, a large proportion of empirical studies in this field fail to give students a voice (e.g., Zimdars, 2010; Haapakoski and Pashby, 2017)—a fact also criticized by applied critical race theorists (Knaus, 2009). A number of them focus on faculty perspectives or key informants on how diversity policies affect students, without actually asking students themselves (e.g., Garces and Cogburn, 2015; Schmaling et al., 2015; Cox, 2017; Casado Pérez, 2019). Some make use of document/policy analysis to explore the effects of diversity policies on students: King (2009), for example, reviews programs in the United States that promote access for underrepresented students, stating that until 2009 “no programs targeted students from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds with disabilities, nor did any studies question college access programs’ neglect to target or measure outcomes for minority students with disabilities.” (King, 2009, 1). Tamtik and Guenter (2019) in turn study how diversity was defined in 50 strategic Canadian higher education documents. They report five institutional strategies for enhanced diversity: political commitment, student recruitment, programmatic supports, research and scholarship, and institutional climate. Nielsen (2014) investigates diversity policies with a specific focus on gender equality by exploring related documents from six Scandinavian universities to find out how and why Danish, Norwegian and Swedish universities achieve different effects in this regard. However, and despite their impressive designs and discoveries, none of these studies gives diverse students a voice.

2. Conceptual framework

To gain a deeper understanding of diversity policy, we need to understand how it is experienced by those directly affected by it. In other words, we need to direct our “attention to the experiences of those who are living under the conditions imposed by policy” (Shaw, 2004, p. 70). Consequently, a critical review would give voice to those affected by diversity policy.

The conceptual background of this study is that of “student voice,” which as a concept has been discussed in higher education research since the 1990s (Cook-Sather, 2006). It consists of two dimensions: (1) student representation (Matthews and Dollinger, 2022) or representative democracy (Stadelmann-Steffen and Freitag, 2011)—a form of student voice, which is typically associated with university governance through representation. Student representation means that one student speaks on behalf of the others (e.g., in policymaking processes). The second dimension is (2) student partnership (Matthews and Dollinger, 2022) or direct democracy (Stadelmann-Steffen and Freitag, 2011)—a form of student voice, which is usually related to the field of teaching and learning. In this dimension active collaboration of students with staff or educators is promoted. The concept of student voice captures a range of activities that strive to re-position students in higher education practice and policy reforms, while the term “voice” signals having a legitimate perspective and opinion, being present, taking part or having an active role in decision making or policy development in higher education (Cook-Sather, 2006). Diversity policies should primarily benefit students from diverse backgrounds, the group for which they were developed and initiated in the first place (Brooks, 2020). However, student perspectives on whether diversity policy matters to them and how it impacts their biographies as students, are often missing in the academic discourse (Singh Sandhu et al., 2022). To the best of my knowledge, no systematic reviews have as yet focused on the accounts of students on diversity policies. Those for whom the diversity policies were developed and initiated (e.g., students with low socio-economic status, students with disabilities, LGBTQ students, etc.) should also be the ones who assess their effects and outcomes. While campus diversity has received considerable attention in recent years, “very little has been done to document these initiatives or assess their impact on the higher education system.” (Cross, 2004, p. 388).

This study thus follows three objectives, to gain a deeper understanding of student voice in diversity policies, to understand how such policy is experienced by those who are directly affected by it, and to present a systematic review which provides an overview of empirical evidence depicting student voice in diversity policies in higher education. The following research questions guided my research in this regard: In which form is student voice (re)presented in studies of diversity policies in higher education? How can this evidence base be described? A possible answer to this question may then inform new practice in higher education policy.

3. Methodology

For the purposes of this research, I conducted a systematic review of empirical studies giving students a voice about diversity policies employed by higher education institutions. A systematic review is a systematically conducted literature review which answers a specific question by applying a replicable search strategy and then includes or excludes studies based on explicit criteria (Gough et al., 2012). The procedure I used to search for, select and analyze studies in this context is described in more detail below.

3.1. Procedure

The literature search was divided into two stages: a database search and a search in individual journals. Journals for the latter were chosen partly as a result of the database search and partly independently because they were thematically fitting (higher education).

3.1.1. Database search

The database search was conducted in three different databases: EBSCO, JSTOR, and SCOPUS. The keyword-based search included the following keywords: higher education, universit*, effect*, divers* polic*, gender polic*, disabilit* polic*, migration* polic*, lgbt* polic*, queer polic*, refugee* polic*, and student*. The application of the search chains in all three databases sustained 883 articles (prior to removal of duplicates).

3.1.2. Journal search

Following the database search, a list of those journals that most frequently published articles on diversity in higher education was compiled. Journals with three or more articles identified in the database search were chosen for an individual journal search. These were: Higher Education, Social Service Review, Social Politics, Higher Education Policy, Journal of Social Policy, Journal of Higher Education in Africa, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, Political Research Quarterly, International Review of Sociology, The Journal of Higher Education, Gender based Violence in University Communities, Policy Futures in Education, Gender and Education, Journal of Disability Policy Studies, Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, Studies in Higher Education, Journal for Multicultural Education, Multicultural Learning and Teaching, Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, and Diversity in Higher Education. The journal search was conducted by applying the search chains used in the database search to every article title in each journal issue between 2000 and 2020. Those articles found relevant in the journal search were collated with the articles from the database search, producing a total of 1,090 articles before removal of duplicates (566).

3.2. Selection of studies

3.2.1. Inclusion criteria

After the search process, 524 articles were assumed fit for abstract screening. This next step provided further clarification on which articles met the inclusion criteria for consideration in the full-text screening. To be included, an article had to meet the following criteria:

• Studies which are relevant to the topic.

• Studies that contain empirical research including student voice (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed method designs).

• Studies were published within the period of the last 20 years (2000–2020).

• Studies were published in a scientific journal.

• Studies address at least one student identity characteristic at the core of the study (e.g., gender, disability, and ethnicity).

• Publication language is English.

• Study focuses on the student perspective (not staff or faculty).

The Covidence systematic review management software1 was then used to determine whether an abstract met the title and abstract screening criteria to decide if it would be included for further investigation or excluded from the study. After title and abstract screening, 368 of the 524 studies were considered irrelevant.

3.2.2. Data extraction

The extraction of adequate full texts was done by two independent reviewers specifying “include” or “exclude” in the Covidence systematic review management and indicating the reason for exclusion (e.g., no empirical data, focus on policies other than diversity policies). Conflicts in selection were eliminated by reaching a consensus between the first and the second reviewer on the adequacy of the studies. The 156 full-text studies assessed for eligibility in the systematic review were then subjected to the final data extraction step, namely a full-text review, in which a total of 21 articles were identified as appropriate for the final analysis (Figure 1).

3.3. Analysis of studies

The analysis regarding the research questions [In which form is student voice (re)presented in studies of diversity policies in higher education? How can this evidence base be described?] was led by inductive coding from the extracted studies (Saldaña, 2013). Two themes emerged from the inductive coding: (1) diversity policies aiming at opening access to higher education for diverse students and (2) student voice on diversity policies within higher education. In the first theme, three subcategories emerged: (1) relieving entry exams for diverse students, (2) setting up scholarship systems for diverse students, and (3) creating (permanent) division in enrolment and admission processes. According to Plotner and Marschall (2014), access to higher education means participant eligibility and admission to higher education. King (2009) concurs with this definition and also views access as admission but also argues that it means physical entrance into higher education institutions and access to and acquisition of new forms of social and cultural capital. In the second theme, four subcategories emerged: (1) student representation, (2) student partnership, (3) lecturer support and institutional support, and (4) positive and negative accounts.

4. Findings

4.1. Study characteristics

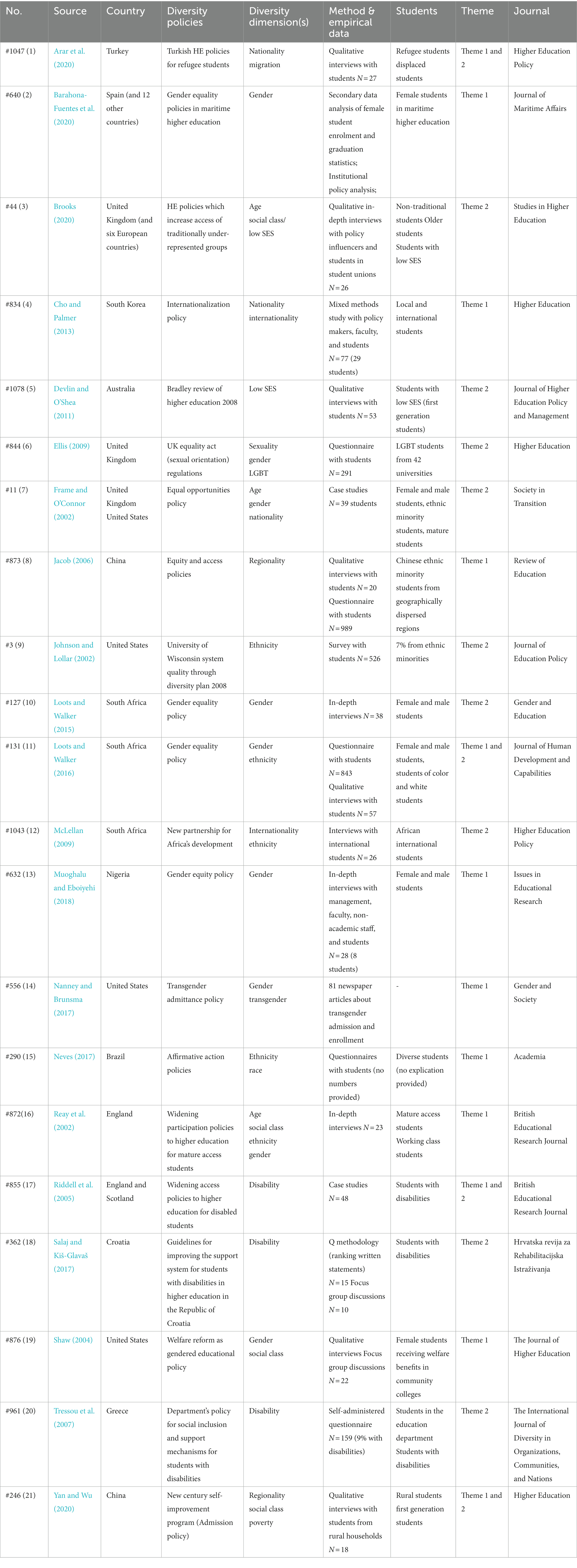

A total of 21 studies were considered eligible and analyzed with regard to the research questions (see Table 1). The selected studies vary greatly in terms of their characteristics and specifications. The geographical placement covers six continents: Africa (Nigeria, South Africa), Asia (China, Turkey, and South Korea), Europe (Croatia, Scotland, Spain, and the United Kingdom), Australia and Oceania (Australia), North America (United States), and South America (Brazil). Two studies compared diversity policies across two countries (England/Scotland and United Kingdom/United States). There were no studies from the Middle East or Eastern Europe. The publication dates were evenly distributed in the given time period: 11 of the studies were published between 2011 and 2020 and 10 between 2000 and 2010.

Of the 21 studies, 11 used a purely qualitative research approach to represent student voice, five adopted a purely quantitative design, and three combined both empirical approaches (mixed-method studies). The remaining two papers used other (creative) methodologies (Q methodology and newspaper analysis). The overall research methods included qualitative interviews, focus group discussions, surveys, questionnaires, case studies, and creative methodologies.

Three of the studies employed a wider empirical sample comprised not only of student voice but also the opinions of lecturers, policy influencers, administrative staff, and other stakeholders (Cho and Palmer, 2013; Muoghalu and Eboiyehi, 2018; Brooks, 2020). All the other studies only made use of student data. From a methodological perspective, the sample sizes in the qualitative designs varied between 18 interviews in the smallest sample and 57 interviews in the largest sample. In the quantitative studies, the variation lay between 159 students completing a survey in the smallest sample to 989 students in the largest sample. In essence, the qualitative designs encompass rather large sample sizes for qualitative studies (a mean of 31 interviews per study), while the quantitative studies seem to incorporate fairly low sample sizes (an average of 561 students).

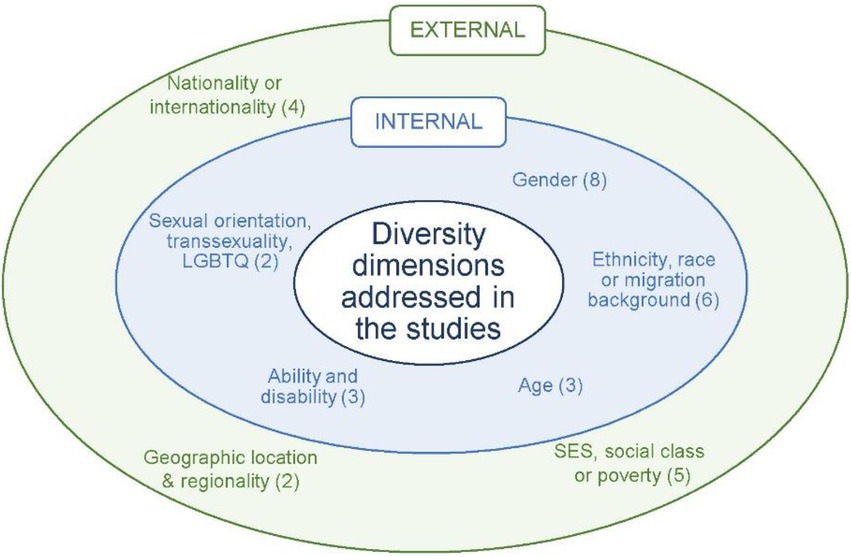

The focus of the diversity dimensions addressed in the extracted studies is broad as can be seen in the adapted diversity wheel below (see Figure 2). It is composed of concentric circles visualizing the intersections between internal and external dimensions. The internal circle of the wheel contains those diversity identity characteristics or dimensions which are hard to change: eight of the studies addressed gender, six investigated student ethnicity, race or migration background, three focused on age, three on ability and disability, and two on sexual orientation, transsexuality, and LGBTQ. The external circle contains those diversity dimensions which are generally changeable: five of the studies addressed socio-economic status (SES), social class or poverty of students, four looked at nationality or internationality, and two focused on the geographic location of students or regionality. While nine studies addressed only one single diversity dimension, the remainder addressed two, three, or four dimensions, thus acknowledging the intersectionality of diversity. Religion and spirituality did not play a role in any of the studies.

Figure 2. Diversity dimensions in the extracted studies (more than one dimension per study possible).

The diversity policies that formed the basis of the extracted studies also varied greatly. In China, for example, the government recently implemented a series of special admission policies for diverse (e.g., rural) student groups (Yan and Wu, 2020). University admission policy in Greece determines that each department must allocate 3% of places to students with disabilities (Tressou et al., 2007), while in the United Kingdom almost all universities have a Disability Statement and respective arrangements in place for students with disabilities (Tinklin et al., 2004).

In terms of the two themes identified in the systematic review, 12 studies focused on theme 1 (opening access to higher education for diverse students), 13 focused on theme 2 (student voice on diversity policies within higher education), while four studies addressed both these themes.

4.2. Diversity policies aiming at opening access to higher education

Within the first theme (Studies #1, 2, 4, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, and 21), studies of diversity policies were included which aimed at opening access to higher education for diverse students, such as the enrolment of Syrian refugee students in Turkey (Arar et al., 2020), minority student enrolment other than Han in China (James, 2006), easier access for Afro-Brazilian and low-income students in Brazil (Neves, 2017), or access of working-class students to higher education (Reay et al., 2002). A good example of such policies in theme 1 are diversity policies for transgender women in a study in the United States by Nanney and Brunsma (2017). Undergraduate students in a women’s college must be legally documented as female at the time of admission. However, since gender as an identity characteristic as fluid and constantly reconstructed, this policy does not adhere to the realities of transgender students. Enrolment and admission processes and policies remain the domain of individual universities and are not regulated at national level. This also applies to diversity policies for refugee students (Arar et al., 2020) and to transgender policies. According to Nanney and Brunsma (2017), only nine women’s colleges in the United States have adopted transgender policies to regulate student admissions. Without an effective gender policy, the gender gap for female students in technical subjects may persist (Barahona-Fuentes et al., 2020) and continue to reproduce inequality. Barahona-Fuentes et al. (2020) measured the effects of institutional gender policies in maritime higher education. Although the results of these policies show a slight increase in female student enrolment at bachelor level and a stabilization of the falling tendency at master and doctoral level, the authors conclude that these effects cannot be ascribed to the gender policies but “to other circumstances such as demographic factors” (p. 152). Studies dedicated specifically to the gender dimension aimed at opening access for female student enrolment in technical subjects (Barahona-Fuentes et al., 2020), female student enrolment in patriarchal systems (Muoghalu and Eboiyehi, 2018), and the enrolment of female students receiving welfare benefits (Shaw, 2004).

In the first theme, three subcategories emerged: 4.2.1 relieving entry exams for diverse students, 4.2.2 setting up scholarship systems for diverse students, and 4.2.3 creating (permanent) division in enrolment and admission processes.

4.2.1. Relieving entry exams for diverse students

Several of the extracted studies found effects in relieving entry exam requirements for diverse students. Refugee students have been exempted from entry exams and tuition fees in Turkey (Arar et al., 2020). In Brazil, some universities have adopted affirmative actions in the form of bonus points in admission exams for diverse student groups, in particular students of color and native-Brazilian students (Neves, 2017). In his study in China, Jacob comes to the conclusion that minority students from geographically dispersed regions across the country need more assistance in preparing for the national college entrance examination and that reform potential has now become visible (Jacob, 2006).

4.2.2. Setting up scholarship systems for diverse students

The need for scholarships is ambivalent in the included studies: Four studies contain information about the assignment of scholarships for diverse students: Arar et al. (2020) note that 5,000 scholarships were allocated to refugee students, while Muoghalu and Eboiyehi (2018) report on scholarship schemes for female students which had led to an increasing number of women going to university. However, since the scholarships were later terminated, no sustainable practice was established for female students. The study of Muoghalu and Eboiyehi (2018) clearly state the ineffectiveness of the gender diversity policy that is in place in Nigeria. Their study showed a slight increase in female undergraduate enrolment but a decrease in female postgraduate enrolment in the 10 years after the implementation of a gender diversity policy (Muoghalu and Eboiyehi, 2018), thus suggesting “that the policy has not met the specific objective of achieving 60:40 male:female ratios in undergraduate and postgraduate student enrolment.” (p. 990). The students who participated in this study reported that they were the only females in their classes or cohorts and felt no impact whatsoever of the gender diversity policy on their student lives: “Nobody is feeling the impact of the policy” (p. 1,002). McLellan (2009) detects a similar low impact, namely a policy disconnection for African international students who study in South Africa. In contrast, only around one tenth of minority students in Jacob’s study expressed major concerns about financing their higher education and needing a scholarship (Jacob, 2006), while Shaw (2004) explored the role of scholarships for female students receiving welfare benefits in community colleges in the United States and found that logistics, child support and childcare are among others the most important barriers to access to higher education for this group.

4.2.3. Creating division in enrolment and admission processes

Many of the current studies regarding this theme of opening access agree that diversity policies in this area create division or dichotomy (e.g., between male and female students or national and international students), which according to student data in the studies continues to persist during one’s studies. This is the case in China for example, where ethnic minority students and students from rural regions remain disadvantaged in accessing higher education. Therefore, their entry exams are relieved, which is a widespread fact among Chinese students. Chinese students reported that the student population is divided into the categories of urban and rural students, fully aware of the differences made during admissions, thus creating permanent division within the student body, which persists during studying (Jacob, 2006). For Brazil, for example, Neves (2017) reports a similar dichotomy in the student population: between non-quota and quota students (students of color from public schools). Also in this case, students are fully aware of the differences made for students of color, and the differences lead to a sustained dichotomy between “us” and “them” among students. Neves (2017) in turn detected a tendency to reduce the differences between white students and students of color in Brazil after the implementation of the diversity policy, although the effect was not large, and most of the students who participated in the survey were resistant to quota policies for students of color but in favor of them for disabled students.

4.3. Student voice on diversity policies within higher education

Within the second theme, (Studies #1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 17, 18, 20, and 21), studies of diversity policies were included which gave students a voice in four subcategories emerged: 4.3.1 student representation, 4.3.2 student partnership, 4.3.3 lecturer support and institutional support, and 4.3.4 positive and negative accounts.

4.3.1. Student representation

In the extracted studies of theme 2, student representation (Matthews and Dollinger, 2022) had different dimensions: securing one’s rights, student advocacy, student voice in policy, and student representation in the curriculum. Student representation serves the purpose of securing one’s rights within a certain group and advocating one’s rights by contributing to change in higher education policymaking, although for example students with disabilities did not believe they had sufficient power for influencing change in all cases (Salaj and Kiš-Glavaš, 2017). Since individual students voiced their concern to secure their own rights, they stressed the need for collective and representative democracy in student associations. The study from Croatia revealed three different forms of student voice in the implementation of policy: silent and passive voice (students without interest in student representation), influential voice (students who advocate rights and are motivated to influence others), and isolated voice (students who lost motivation for action; Salaj and Kiš-Glavaš, 2017). Brooks (2020) argues that student representation can only be made stronger by giving those who work on diversity and equality within the university a stronger institutional voice. Lastly, students voiced their concern about diversity being represented in study programs or curricula. Less than one fifth of students thought that diversity was covered well in their study program curriculum (Ellis, 2009). The female students in Loots and Walker’s study reported that women were not equally represented in pedagogical and curricular content, which thus led to them having no voice in classroom practices (Loots and Walker, 2015). Devlin and O’Shea (2011) additionally conclude that diversity policies outside the curriculum are likely to have no impact on students, in particular those with low SES who are short of time and do not spend time on campus. Ellis (2009) concludes that universities neglect their duties of ensuring diversity and equality for LGBT students. In particular, they fail to actively implement and enforce diversity and non-discrimination policies and ensure adequate representation of LGBT perspectives in associations or marketing.

4.3.2. Student partnership

The analysis revealed different dimensions of student partnership (Matthews and Dollinger, 2022) among peer students and with lecturers: student participation in student associations (Johnson and Lollar, 2002), engaging with lecturers as partners (Loots and Walker, 2015), having small groups or study partners as a form of partnership (Devlin and O’Shea, 2011), student partnerships between African students (McLellan, 2009), and facilitating learning partnerships between dominant and excluded student groups (Tressou et al., 2007). Student participation was further described as a necessity of specific groups as a massification effect of higher education (Brooks, 2020).

4.3.3. Lecturer support and institutional support

Lecturers and students were largely unaware of existing diversity policies (Riddell et al., 2005). Tressou et al. (2007) studied the effects of a policy for social inclusion and the respective support mechanisms for students with disabilities in Greece. They surveyed students with and without disabilities about their personal experiences with exclusion and their assessments of the policy and found that 40% of the students were in fact unaware of social inclusion policies and support mechanisms for students with disabilities at the department in question. One reason for this is that the department’s curricular and policy objectives have not been effectively communicated and students still rely on common knowledge. In this case, students recommended organizing more programs and events to raise awareness, improve existing substructures in the department and enhance interaction between minority and majority student populations. Furthermore, all students who participated in the study by Riddell et al. (2005) experienced difficulties in persuading lecturers in their departments to adjust teaching and assessment practices to accommodate their needs as students with disabilities.

Institutional support also comprises assistance in entering buildings, securing accommodation, and all forms of student aid services, which are especially relevant for students with disabilities. However, students with disabilities from Croatia (Salaj and Kiš-Glavaš, 2017) reported that universities do not invest enough effort into developing different models of support that make it easier for them to study. They also believed that they did not have a strong representation as a student group in influencing diversity policies for disabled students. Refugee students in the study Arar et al. (2020) reported that there was no specific diversity policy which recognized their needs. They reported that language barriers, financial issues and lack of guidance were key challenges in higher education, pointing out that there was no institutionalized support system to guide them inside and outside the campus (Arar et al., 2020). Older students named diversity policies, which allow access to childcare, as a necessity of institutional support to complete their studies. Students on welfare benefits, which are by trend older, also face these barriers when studying. They reported a need for childcare as an essential form of institutional support (Shaw, 2004). However, institutional support (e.g., induction phases, online learning facilities or library services, and childcare) is the only category of analysis, which is likely to have an impact on all student groups independent of their individual identity characteristics as it affects all students alike regardless of their study program or course (Devlin and O’Shea, 2011).

4.3.4. Positive and negative accounts

Studies documented positive student voice, e.g., becoming more culturally aware and accepting of racially and culturally different student identities due to diversity policy on campus (Johnson and Lollar, 2002). 75% of the students of ethnic minority in the United States in Johnson and Lollar’s study felt that they had become more culturally aware and accepting of racially and culturally different peers since entering college. They reported a high impact of diversity policies and having learned much about racial and ethnic diversity when being exposed to it during their studies. Students in the study by Brooks (2020) reported a positive image of age diversity in the student population after access policies in higher education had been changed to allow greater age diversity in the student body. Frame and O’Connor (2002) identified further positive experiences and benefits of getting acquainted with diversity while studying: students assessed diversity policy as beneficial for their future careers.

Negative student voice included LGBT students having been victims of homophobic harassment (Ellis, 2009) or African international students being the victims of crimes or xenophobia (McLellan, 2009). One fourth of the LGBT students in the study Ellis (2009) reported having been the victim of homophobic harassment or discrimination on campus at least once during their studies although diversity policies were in place. Most of these incidents occurred in public spaces on campus outside class among students without teaching staff being present. African international students in the study of McLellan (2009) expressed fear of being the victim of crime or xenophobia and had experienced a negative climate toward foreigners and diversity in general: they had regular contact to other international students but not to local students, which led to exclusion. In addition, students expressed concerns, worries and fears about working with peer students different to themselves in terms of age, ethnicity, social class, or language, noting, for example, that they would expect to receive poorer grades when working in a small group with non-English students (Frame and O’Connor, 2002). Female students conveyed experiences of sexual harassment by male peers on campus, however, the aim of diversity policies should be making student feel safe and promoting bodily integrity on campus and in class (Loots and Walker, 2015).

5. Discussion

In general, the number of published studies reporting on students’ perceptions of diversity policies in higher education empirically from their own perspective is low. Those for whom diversity policies were developed and initiated (e.g., students with low SES, students with disabilities, and LGBTQ students) should be the ones who rate their respective effects and outcomes. Unfortunately, a large proportion of the empirical studies identified in the screening process failed to give students a voice and were therefore excluded (e.g., Garces and Cogburn, 2015; Cox, 2017). Indeed, a number of studies have been published which focus on faculty perspectives or explore the opinions of members of faculty (sometimes in key positions) regarding the effect of diversity policies on students, yet do not ask the students themselves.

In terms of geographical reach, the included publications are well distributed between the continents, although there is a lack of studies from Eastern Europe and the Middle East, where diversity policies for the student body might not play a (political or cultural) role in higher education institutions. However, one noteworthy study from Afghanistan was identified in the systematic search process, despite not meeting our inclusion criteria (Hayward and Karim, 2019). The authors of this study report on the enforcement of the Higher Education Gender Strategy that was formally introduced in Afghanistan in 2016 but do not, however, present any data which indicates change after the implementation of this policy. The review described in this article only included (empirical) studies that followed high methodological standards (highly ranked and peer reviewed journals), focused specifically on one or more dimensions of diversity (e.g., gender, SES, ethnicity, and disability), evaluated a specific diversity policy or gave students a voice (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies). This decision was made to allow a more reliable judgment of the perception of diversity policies by students based on empirical data. When reviewing diversity policies in higher education, it becomes evident that the students in the 21 extracted studies reach different conclusions regarding their effects. In other words, the students do not speak in a unanimous voice.

Regarding the overall results of the systematic review with respect to the research questions, both dimensions of student voice (student representation and student partnership, Matthews and Dollinger, 2022) were found to play a role in the extracted studies. Student partnerships were described in two dimensions of lecturer support and partnerships among students. This shows that student biographies and their respective experiences with diversity policy cannot be reduced to the individual (subject-orientation). Their single experiences are also structured as collective experiences in the context of higher education together with peer students and lecturers (context-orientation). Student’s accounts of diversity policies must therefore be interpreted as a relation between subject and context—the collective conditions for diversity, such as structures, institutional rules, hierarchies, or diversity policies: “As with all education policy, despite the superficial noisy welter of innovation, at a deeper, more impenetrable level, certain structures remain much more resistant to change.” (Reay et al., 2002, 17). The context—here in the form of diversity policies—shapes the subject.

In addition, evidence was found for diversity policies to open access for certain students through scholarships or entry relief support. Opening access is in line with the London Communiqué, which calls for the creation of “more flexible learning pathways into and within higher education” for non-traditional student groups (London Communiqué, 2007, p. 5). However, inequalities in access to higher education “endure despite the many access initiatives and policies” (Reay et al., 2002, 17). Only four of the studies examined actually connected the themes of opening access and student voice. Since these remain a minority, it can be assumed that “enhancing access does not necessarily mean widening participation” (Tressou et al., 2007, p. 260), especially because categories established during admission processes tend to remain meaningful during one’s studies.

The review revealed positive and negative accounts of students, who assess the effects of diversity policies on campus or in class. Listening to the ways in which diverse student groups actually describe their experiences with diversity policies can help higher education researchers and policymakers to develop a more nuanced understanding of how these policies function for their target groups (Shaw, 2004). Policymakers need to make sure that diversity policies do not become “trees without fruit”—barren due to their inability to resonate within the student body (and faculty). Accordingly, I would like to summarize the following recommendations for policymakers identified in the analyzed studies:

• Guarantee funding for the implementation of diversity policies for all students affected but especially for working-class students, students with low SES or first generation students (Reay et al., 2002; Muoghalu and Eboiyehi, 2018).

• Accept refugee students as international students using the descriptor “international students” instead of “foreign students” in order to foster anti-stigmatization (McLellan, 2009; Arar et al., 2020).

• Advance female enrolment policies in technical fields (Barahona-Fuentes et al., 2020).

• Ensure specific support for students from rural areas in entry exams (Jacob, 2006).

• Adopt inclusive transgender policies in admission processes by abandoning the notion of who cannot attend a women’s college (who is not a woman) following biology-based and legal-based criteria and making conscious choices in policies on inclusive forms of gender identity following identity-based criteria (Nanney and Brunsma, 2017).

Institutions must build and coordinate support services for diverse student groups (King, 2009) depending on the specific context in which a diversity policy has created division (e.g., between male and female students, national and international students, or rural and urban students). This should include individually focused support such as financial aid for rural students or disability resource services, peer group support aimed at strengthening interpersonal peer relationships between diverse groups and improved institutional quality such as training or curriculum development. Recommendations in this regard are as follows:

• Relieving admissions to university is a key objective of diversity policies, however, only if these policies do not create more differences than they are hoping to overcome. It is recommended, therefore, to desist from policies with a single focus (e.g., gender), which would reproduce existing inequalities (Loots and Walker, 2015), but to focus on intersectional policies which create positive discrimination for different student groups alike without maintaining difference while they study.

• A permanent division of the student body needs to be avoided on policy and practice level. Given the majority of—for example ethnic minority—student groups in China, Jacob (2006) recommends not reinforcing given identities by diversity policies (such as being a student from rural China) but stimulating new ones. Differences and tensions between student groups, e.g., between quota and non-quota students in Brazil (Neves, 2017), are reinforced by the lack of social acceptance of the policies. The quota policies change minority students’ access to higher education, their social identity, but the social acceptance of diversity on campus takes longer. Therefore, resistance and acceptance of diversity policies in different student groups need to be studied in the future.

• Enhance knowledge and skills of staff members to better meet the needs of diverse student groups (Devlin and O’Shea, 2011). Most unawareness can be explained through negative mental constructs or attitudes of students or staff members being unaware of the needs of diverse student groups, a resistance to behavior change, non-effective diversity trainings and non-effective communication of policies (Moreu et al., 2021).

• Evaluate existing interventions in order to improve practices and substructures, which enhance the interaction between minority and majority student populations. There is mixed evidence of the effects of diversity practices which aim to reduce prejudice and discrimination (Noon, 2018). The question remains open, how the readiness for behavior change can be enhanced in staff members, especially those who attend mandatory diversity trainings.

• Pay more attention to how diversity is managed within the classroom setting as well as on campus (Ellis, 2009).

• View diversity education and training as part of the curriculum, no matter which study program (Devlin and O’Shea, 2011; Loots and Walker, 2015).

• Address male and majority students in activities to raise awareness for diversity policies; female students and minorities are more likely to assign importance to diversity and racial understanding and thus also more likely to desire a diverse and inclusive campus (Johnson and Lollar, 2002).

• Support diverse students in founding or joining student associations which represent their interests (McLellan, 2009). Diverse students themselves should be given a louder voice in representative functions to raise awareness for their needs (student voice and student representation).

The current review should also be read with several limitations in mind. Despite the systematic review process, it is possible that some relevant publications might have been overlooked due to the keywords used or the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Non-English language articles, dissertations, or book chapters, which might have revealed further evidence in this matter, were likewise ruled out. This traditional publication bias is a frequently reported limitation in systematic reviews (Zee and Koomen, 2016). The timeframe was also limited to only publications issued between 2000 and 2020. Moreover, since studies on diversity policies in specific higher education institutions around the globe might be aimed at an internal audience (e.g., higher education management or diversity officers), it can be expected that some of them will have been conducted solely for internal purposes and never intended for an international audience or academic publication. While some studies did initially report on diversity policies, a deeper read revealed that they did not focus on a specific such policy: diversity policies were the framework of the study but not the topic of analysis. Studies which focused on financing policies for student admissions (which contribute in general but not directly to diversity in higher education) were ruled out, as were quality assurance policies with no focus on diversity in higher education. Within the review process, many studies were found that focused on the prevention of violence in American universities (sexual harassment policies, etc.) but did not specifically tackle diversity. Studies with a focus on system diversity (in contrast to individual or group diversity) were also ruled out (e.g., diversity of study programs, systemic diversity, and programmatic diversity; Piché and Jones, 2016). It should also be noted that systematic reviews are rare in the field of diversity policy. One explanation for this might be that the policies studied are specific to a given institution or context and therefore difficult to generalize. Furthermore, since the student body has become extremely diverse in recent years, studies reviewing the effects of diversity policies now address a broad range of target groups, making it difficult to compare such policies for different student groups (e.g., first-generation, LGBTQ, or female students of color), who all face different challenges in accessing and participating in higher education. As a result, the studies available do not target the same policies or the same student groups. Consequently, while the findings presented here provide an initial window into the overall body of research on the effects of diversity policies identified during this systematic search, further research is required to provide deeper insight into the assessments of these effects by students and faculty.

6. Conclusion

This review provides a systematic insight into the students’ perceptions of diversity policies in higher education. Unfortunately, most of the available studies in this field do not seem to build effectively on one another. For this reason, a next valuable step would be to conduct a discourse analysis to identify key researchers and their messages within this field of research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Marta Cristina Azaola and Adalberto Aguirre Jr for their contribution to the study, in particular for being the independent reviewers during the search and screening process of this systematic review.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Arar, K., Kondakci, Y., Kasikci, S. K., and Erberk, E. (2020). Higher education policy for displaced people: implications of Turkey’s higher education policy for Syrian migrants. High Educ. Pol. 33, 265–285. doi: 10.1057/s41307-020-00181-2

Arce-Trigatti, A., and Anderson, A. (2019). Shortchanging complexity: discourse, distortions, and diversity policy in the age of neoliberalism. Educ. Policy Analy. Arch. 27, 1–24. doi: 10.14507/epaa.27.4268

Barahona-Fuentes, C., Castells-Sanabra, M., Ordás, S., and Torralbo, J. (2020). Female figures in maritime education and training institutions between 2009 and 2018: analysing possible impacts of gender policies. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 19, 143–158. doi: 10.1007/s13437-019-00190-y

Bastedo, M. N., and Gumport, P. J. (2003). Access to what? Mission differentiation and academic stratification in U.S. public higher education. High. Educ. 46, 341–359. doi: 10.1023/A:1025374011204

Brooks, R. (2020). Diversity and the European higher education student: policy influencers’ narratives of difference. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 1507–1518. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1564263

Byrne, B. (2006). White Lives. The Interplay of ‘Race’, Class and Gender in Everyday Life. (London and New York: Routledge).

Casado Pérez, J. F. (2019). Everyday resistance strategies by minoritized faculty. J. Divers. High. Educ. 12, 170–179. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000090

Cho, Y. P., and Palmer, J. D. (2013). Stakeholders’ views of South Korea’s higher education internationalization policy. High. Educ. 65, 291–308. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9544-1

Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, Presence, and Power: “Student Voice” in Educational Research and Reform. Curriculum Inquiry 36, 359–390.

Cox, N. (2017). Enacting disability policy through unseen support: the everyday use of disability classifications by university administrators. J. Educ. Policy 32, 542–563. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2017.1303750

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chicago Legal Forum 140, 139–167.

Cross, M. (2004). Institutionalising campus diversity in South African higher education: Review of diversity scholarship and diversity education. Higher Education 47, 387–410.

Devlin, M., and O’Shea, H. (2011). Directions for Australian higher education institutional policy and practice in supporting students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 33, 529–535. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2011.605227

Ellis, S. J. (2009). Diversity and inclusivity at university: a survey of the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) students in the UK. High. Educ. 57, 723–739. doi: 10.1007/s10734-008-9172-y

Frame, P., and O’Connor, J. (2002). From the “high ground” of policy to “the swamp” of professional practice: the challenge of diversity in teaching labour studies. S. Afr. Rev. Sociol. 33, 278–292. doi: 10.1080/21528586.2002.10419066

Garces, L. M. (2014). Aligning diversity, quality, and equity: the implications of legal and public policy developments for promoting racial diversity in graduate studies. Am. J. Educ. 120, 457–480. doi: 10.1086/676909

Garces, L. M., and Cogburn, C. D. (2015). Beyond declines in student body diversity: how campus-level administrators understand a prohibition on race-conscious postsecondary admissions policies. Am. Educ. Res. J. 52, 828–860. doi: 10.3102/0002831215594878

Goastellec, G. (2012). The Europeanisation of the measurement of diversity in education: a soft instrument of public policy. Glob. Soc. Educ. 10, 493–506. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2012.735152

Gough, D., Oliver, S., and Thomas, J. (2012). An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. (Los Angeles: Sage)

Haapakoski, J., and Pashby, K. (2017). Implications for equity and diversity of increasing international student numbers in European universities: policies and practice in four national contexts. Policy Futures Educ. 15, 360–379. doi: 10.1177/1478210317715794

Hayward, F. M., and Karim, R. (2019). The struggle for higher education gender equity policy in Afghanistan: obstacles, challenges and achievements. Educ. Policy Analy. Arch. 27, 1–25. doi: 10.14507/epaa.27.3036

Horn, C. L., and Flores, S. M. (2003). Percent Plans in College Admissions: A Comparative Analysis of Three States’ Experiences. (Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University).

Hurtado, S. (2007). Linking diversity with the educational and civic missions of higher education. Rev. High. Educ. 30, 185–196. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2006.0070

Iverson, S. V. (2012). Constructing outsiders: the discursive framing of access in university diversity policies. Rev. High. Educ. 35, 149–177. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2012.0013

Jacob, W. J. (2006). Social justice in Chinese higher education: regional issues of equity and access. Rev. Educ. 1, 149–169. doi: 10.1007/sl1159-005-5613-3

James, W. J. (2006). Social Justice in Chinese Higher Education: Regional Issues of Equity and Access. Review of Education 1, 149–169.

Johnson, S. M., and Lollar, X. L. (2002). Diversity policy in higher education: the impact of college students’ exposure to diversity on cultural awareness and political participation. J. Educ. Policy 17, 305–320. doi: 10.1080/02680930210127577

King, K. A. (2009). A Review of Programs That Promote Higher Education Access for Underrepresented Students. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 2, 1–15.

Klein, U. (2016). Gender equality and diversity politics in higher education: conflicts, challenges and requirements for collaboration. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 54, 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2015.06.017.

Knaus, C. B. (2009). Shut up and listen: applied critical race theory in the classroom. Race Ethn. Educ. 12, 133–154. doi: 10.1080/13613320902995426

London Communiqué (2007). Towards the European higher education area: Responding to challenges in a globalised world. European Commission.

Loots, S., and Walker, M. (2015). Shaping a gender equality policy in higher education: which human capabilities matter? Gend. Educ. 27, 361–375. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2015.1045458

Loots, S., and Walker, M. (2016). A capabilities-based gender equality policy for higher education: conceptual and methodological considerations. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 17, 260–277. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2015.1076777

Matthews, K. E., and Dollinger, M. (2022). Student Voice in Higher Education: The Importance of Distinguishing Student Representation and Student Partnership. Higher Education. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00851-7

McLellan, C. E. (2009). Cooperative policies and African international students: do policy spirits match experiences? High Educ. Pol. 22, 283–302. doi: 10.1057/hep.2009.11

Milem, J. F., Chang, M. J., and Antonio, A. L. (2005). Making Diversity Work on Campus: A Research-Based Perspective. (Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities)

Moreu, G., Isenberg, N., and Brauer, M. (2021). How to promote diversity and inclusion in educational settings: behavior change, climate surveys, and effective pro-diversity initiatives. Front. Educ. 6:668250. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.668250

Muoghalu, C. O., and Eboiyehi, F. A. (2018). Assessing Obafemi Awolowo University’s gender equity policy: Nigeria’s under-representation of women persists. Issues Educ. Res. 28, 990–1008.

Nanney, M., and Brunsma, D. (2017). Moving beyond cis-terhood: determining gender through transgender admittance policies at U.S. Women’s colleges. Gend. Soc. 31, 145–170. doi: 10.1177/0891243217690100

Neves, P. S. C. (2017). Universities, inequalities and public policy: a brief discussion of affirmative action in higher education in Brazil. Acad. Ther. 10, 79–108.

Nielsen, M. W. (2014). Justifications of gender equality in academia: comparing gender equality policies of six Scandinavian universities. Nordic J. Feminist Gender Res. 22, 187–203. doi: 10.1080/08038740.2014.905490

Noon, M. (2018). Pointless diversity training: unconscious bias, new racism and agency. Work Employ. Soc. 32, 198–209. doi: 10.1177/0950017017719841

Piché, P. G., and Jones, G. A. (2016). Institutional diversity in Ontario’s university sector: a policy debate analysis. Can. J. High. Educ. 46, 1–17. doi: 10.47678/cjhe.v46i3.188008

Plotner, A. J., and Marschall, K. J. (2014). Navigating university policies to support postsecondary education programs for students with intellectual disabilities. J. Disab. Policy Stud. 25, 48–58. doi: 10.1177/1044207313514609

Reay, D., Ball, S., and David, M. (2002). It’s taking me a long time but I’ll get there in the end’: mature students on access courses and higher education choice. Br. Educ. Res. J. 28, 5–19. doi: 10.1080/01411920120109711

Riddell, S., Tinklin, T., and Wilson, A. (2005). New labour, social justice and disabled students in higher education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 31, 623–643. doi: 10.1080/01411920500240775

Salaj, I., and Kiš-Glavaš, L. (2017). Perceptions of students with disabilities regarding their role in the implementation of education policy: a Q method study. Hrvatska Revija za Rehabilitacijska Istraživanja 53, 47–62.

Schmaling, K. B., Trevino, A. Y., Lind, J. R., Blume, A. W., and Baker, D. L. (2015). Diversity statements: how faculty applicants address diversity. J. Divers. High. Educ. 8, 213–224. doi: 10.1037/a0038549

Shaw, K. M. (2004). Using feminist critical policy analysis in the realm of higher education. J. High. Educ. 75, 56–79. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2004.11778896

Singh Sandhu, H., Chen, R., and Wong, A. (2022). Faculty diversity matters: a scoping review of student perspectives in North America. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 26, 130–139.

Stadelmann-Steffen, I., and Freitag, M. (2011). Making Civil Society Work: Models of Democracy and Their Impact on Civic Engagement. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 40, 526–551.

Tamtik, M., and Guenter, M. (2019). Policy analysis of equity, diversity and inclusion strategies in Canadian universities—how far have we come? Can. J. High. Educ. 49, 41–56. doi: 10.7202/1066634ar

Tinklin, T., Riddell, S., and Wilson, A. (2004). Policy and provision for disabled students in higher education in Scotland and England: the current state of play. Stud. High. Educ. 29, 637–657. doi: 10.1080/0307507042000261599

Tressou, E., Mitakidou, S., and Karagianni, P. (2007). The diversity in the university: students’ ideas on disability issues. Int. J. Diver. Organ, Commun. Nat. 7, 259–266. doi: 10.18848/1447-9532/CGP/v07i04/39418

Valverde, L. A., and Castenell, L. A. (1998). The Multicultural Campus: Strategies For Transforming Higher Education. (London: AltaMira Press).

Yan, K., and Wu, L. (2020). The adjustment concerns of rural students enrolled through special admission policy in elite universities in China. High. Educ. 80, 215–235. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00475-4

Zee, M., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: a synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 981–1015. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626801

Keywords: diversity, diversity policies, higher education, student voice, systematic review

Citation: Resch K (2023) Student voice in higher education diversity policies: A systematic review. Front. Educ. 8:1039578. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1039578

Edited by:

Kay Fuller, University of Nottingham, United KingdomReviewed by:

Marta Cristina Azaola, University of Southampton, United KingdomAdalberto Aguirre Jr, University of California, Riverside, United States

Copyright © 2023 Resch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katharina Resch, ✉ a2F0aGFyaW5hLnJlc2NoQHVuaXZpZS5hYy5hdA==

Katharina Resch

Katharina Resch