95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 02 March 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1024054

This article is part of the Research Topic Transforming Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan African Countries Towards the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4 by 2030: New Opportunities, Challenges, Problems and Prospects View all 7 articles

Introduction: South Africa embraced the move to inclusive education after the political transformation in 1994 by partaking in and subscribing to the international Education for All (EFA) drive initiated in 1990 at the Jomtien World Conference on Education for All, which declared that all children, youth and adults should receive a basic education. Furthermore, the Salamanca Statement of 1994 the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) of 2006 and the Sustainable Development Goal 4 are internationally regarded as the most important influence on the transformation of education systems to become more inclusive and consequently continue to have an important influence on education policies and practices in South Africa. The key policy driving inclusive education in South Africa is Education White Paper 6 (EWP6). EWP6 affirms that teachers play a central role in implementing an inclusive education system. Therefore, training is emphasized as a key strategy to enable educators to become more inclusive in their teaching practices. The focus of this article is on Initial Teacher Education (ITE) for inclusion. Influenced by international developments to transform ITE programmes and the national endorsement of inclusive education the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) embarked on a project called the Teaching and Learning Capacity Development Improvement Project (TLCDIP). The project reported on in this article was one facet of the TLCDIP and focused specifically on teacher education for inclusion in the Foundation (Reception to Grade 3) and Intermediate Phases (Grade 4 to 6) of the Baccalaureus Educationis (B Ed) programme.

Methods: The primary research aim was: To explore the perceptions of final year students and their lecturers in ITE programmes regarding the preparation of pre-service teachers for teaching in inclusive and diverse learning environments. A qualitative research approach was employed to gain in-depth and rich data. Purposive sampling was used including final year students and their lecturers. Open questionnaires and group interviews were employed as data generation strategies.

Results: An inductive thematic analysis showed that the following themes were identified by the participants as critical to be considered in the development and implementation of ITE programmes: Understanding inclusive education, which is also linked to knowledge; the disconnect between theory and practice, the lack of knowledge and practical experience regarding inclusive teaching strategies and how inclusion is addressed in the B Ed curriculum.

South Africa embraced the move to inclusive education by partaking in and subscribing to the international Education for All (EFA) drive initiated in 1990 at the Jomtien World Conference on Education for All, which declared that all children, youth and adults should receive a basic education (UNDO, UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank, 1990). Furthermore, the Salamanca Statement of 1994 (UNESCO, 1994) is internationally regarded as the most important influence on the transformation of education systems to become more inclusive. This statement was also endorsed and used as an integral foundation for the development of inclusive education policies in South Africa. In essence the Salamanca Statement asserted that: “Regular schools with [an] inclusive orientation are the most effective means of combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all; moreover, they provide an effective education to the majority of children and improve the efficiency and ultimately the cost-effectiveness of the entire education system (UNESCO, 1994, p. 9). Other significant inducements toward inclusive education in South Africa include the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) of 2006, which was accepted in 2007, and the Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4). Article 24 of the CRPD requires countries to ‘ensure an inclusive education system at all levels’ (United Nations, 2006, p. 16). SDG4 affirms that inclusive and equitable quality education must be ensured and lifelong learning opportunities for all must be promoted (Department Statistics South Africa, 2019).

In addition to integrating the abovementioned international movements to transform the South African education system it was also necessary to operationalize the South African constitution (RSA, 1996), which requires that education must address diversity and apply inclusivity. Education White Paper 6 (EWP6; DoE, 2001) on Special Needs Education: Building an inclusive education and training system, was accepted in 2001 and consequently inclusive education was officially endorsed by the South African government. The goal of EWP6, is in accordance with the SDG4 principle, and emphasizes that education for all must be promoted and the development of inclusive and supportive centers of learning should be enabled to ensure that all learners participate actively in the education process so that they could develop and extend their potential and participate as equal members of society (DoE, 2001, p. 5). EWP6 also affirm that teachers play a central role in implementing an inclusive education system. Training therefore is seen as a key strategy to enable educators to become inclusive teachers and competent in recognizing and addressing barriers to learning, as well as in accommodating diverse learning needs.

The focus of this article is on Initial Teacher Education (ITE) for inclusion. Influenced by international developments to transfrom ITE programes and the national endorsement of inclusive education the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) embarked on a project called the Teaching and Learning Capacity Development Improvement Project (TLCDIP), which was funded by the European Union (EU). Four universities were purposefully approached by VVOB South Africa (Flemish association for development in education), an EU partner in this project, to be part of the research. The request was to specifically focus on teacher education for inclusion in the Foundation and Intermediate Phases.

Before describing the research, it is firstly important to clarify the key concepts of inclusive education and ITE as it was applied for the study reported in this article.

Essentially, inclusive education implies that learners with diverse learning needs are present in one classroom. Learners from different backgrounds, ethnicity, languages, religions, sexual orientations, races, gender and dis/abilities thus attend the same school and should not be excluded or discrimated against in any way, emphasizing a social approach to inclusion (Slee and Allan, 2001; Ainscow, 2016; UN, 2016). Social exclusion often perseveres as a consequence of discriminatory attitudes and responses to diversity in race, social class, ethnicity, religion, gender, and (dis)ability (Vitello and Mithaug, 1998). A social approach to inclusive education therefore encompasses the belief that education is a basic human right and the foundation for a more just society (Ainscow, 2014; Nel, 2018). This requires transforming and enabling communities, systems and structures (such as schools and Higher Education Institutions) to recognize diversity, promote participation for all and address barriers to learning (United Nations, 2016). Thus, attitudes, policies and practices should not prevent any learner from participating, or experiencing success and a feeling that they belong. Instead, it is about identifying and addressing exclusionary pressures and harnessing the resources needed to provide the support that learners require (Slee, 2019a,b).

Teacher education is a major determinant of teachers’ willingness and ability to teach inclusively. There seems to be three core considerations for ITE, namely outcomes, content and form.

Outcomes refer to the inclusive education competencies expected of beginner teachers. Loreman (2010), p. 129 offers a synthesis of the “essential skills, knowledge and attributes for inclusive teachers identified in the literature.” These are identified in seven areas, which he phrases as “outcomes” for pre-service teachers. The seven areas are:

• Respect for diversity and an understanding of inclusion;

• Engaging in inclusive instructional planning;

• Instructing in ways conducive to inclusion;

• Engaging in meaningful assessment;

• Fostering a positive social climate;

• Collaboration with stakeholders, and.

• Engaging in lifelong learning.

In addition, the European Agency for the Development of Special Needs Education (EADSNE, 2012) describes the competences of inclusive teachers, by suggesting four core values, each with subsections of areas of competence. These are:

(a) Valuing Learner Diversity–learner difference is considered as a resource and an asset to education.

The areas of competence within this core value relate to:

• Conceptions of inclusive education;

• The teacher’s view of learner difference.

(b) Supporting All Learners–teachers have high expectations for all learners’ achievements.

The areas of competence within this core value relate to:

• Promoting the academic, practical, social and emotional learning of all learners;

• Effective teaching approaches in heterogeneous classes.

(c) Working With Others – collaboration and teamwork are essential approaches for all teachers.

The areas of competence within this core value relate to:

• Working with parents and families;

• Working with a range of other educational professionals.

(d) Personal Professional Development–teaching is a learning activity and teachers take responsibility for their lifelong learning.

The areas of competence within this core value relate to:

• Teachers as reflective practitioners.

• Initial teacher education as a foundation for ongoing professional learning and development.

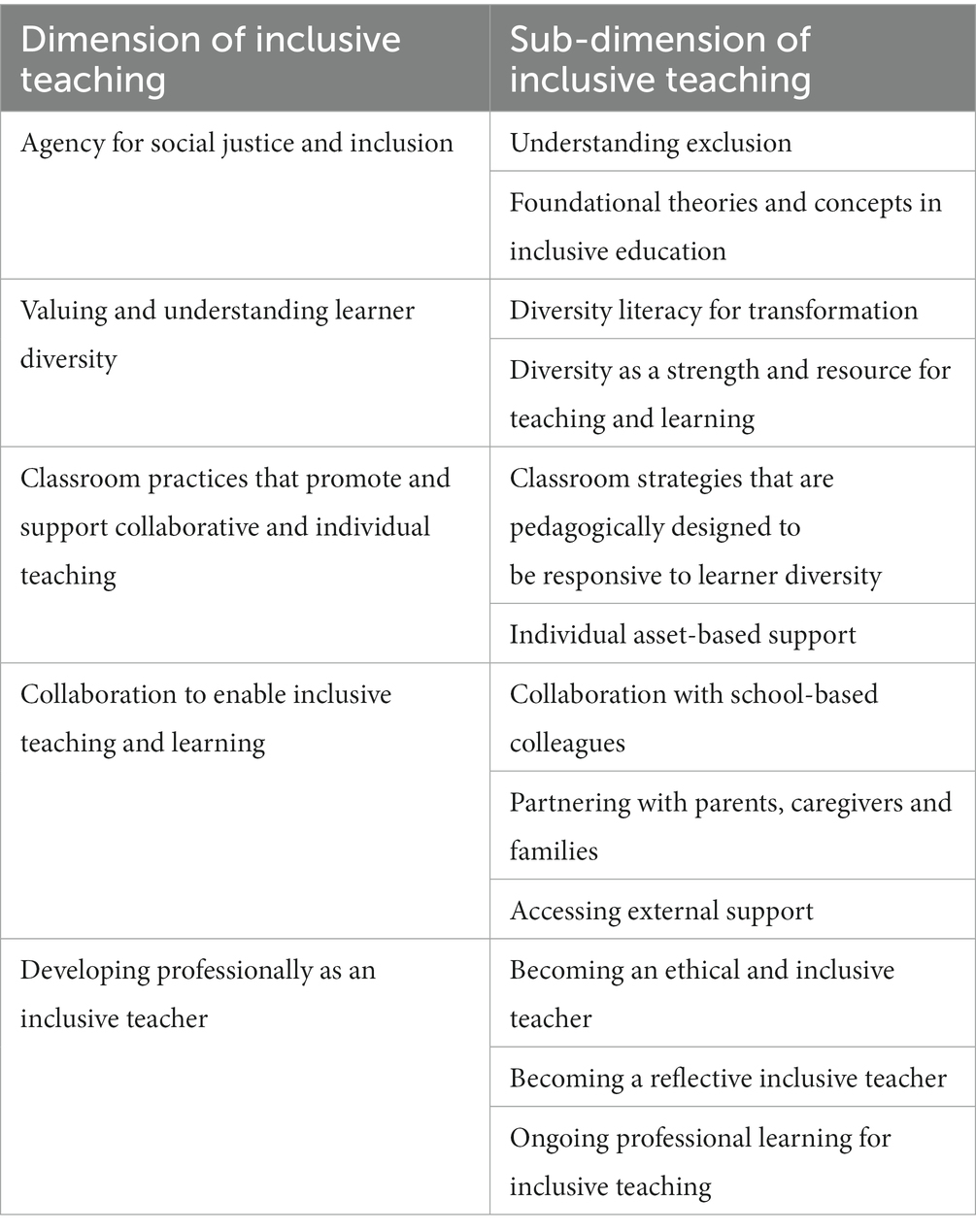

Drawing on these and other international examples, a South African team tasked by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) developed a set of knowledge and practice standards for inclusive teaching for beginner teachers, which are being introduced to HEIs for integration into their B.Ed programes. This schema identifies five dimensions of inclusive teaching, each with two or three sub-dimensions, which are further described as standards. The dimensions and sub-dimensions are (Table 1):

Table 1. Dimensions and sub-dimensions of inclusive teaching (Source: DHET, 2017).

It is clear from these three examples that the expected outcomes from initial teacher education for inclusion are: that teachers understand and value learner diversity and inclusive education; that they can implement classroom and teaching practices that enable effective learning for all; that they are prepared to, and are equipped for collaboration with families, other teachers, specialist personnel, NGOs and other stakeholders; and that they appreciate the value of ongoing professional learning.

The content of courses/modules in inclusive education in initial teacher education should mediate the aforementioned development of competences. However, internationally there is a debate about what should be included in ITE courses. Research has identified possible topics, including an inclusive pedagogy (e.g., Spratt and Florian, 2015; Maher et al., 2022); equity consciousness and literacy (e.g., Bukko and Liu, 2021); learner diversity (e.g., Forlin and Chambers, 2011; Sharma and Sokal, 2015; Spratt and Florian, 2015; Stunell, 2021); knowledge about disability categories relevant to teaching (e.g., Swain et al., 2012; McKenzie et al., 2020); debates about the medical and social models of disability (e.g., Engelbrecht, 2019); universal design of learning (e.g., Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2022); differentiation through instructional and curricular adaptations and modifications (e.g., D’Intino and Wang, 2021; Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021); various types of cooperative learning and peer teaching (e.g., Klang et al., 2020; Tullis and Goldstone, 2020); co-teaching (e.g., Pizana, 2022); behavior management (Karhu et al., 2019); learner support (Nel et al., 2022); collaborative models and practices (Bentley-Williams et al., 2017); and relevant ideologies, policy and legal frameworks (Waitoller and Thorius, 2015; Essex et al., 2021; De Beco, 2022; Heng et al., 2022). Walton and Rusznyak (2017) argue that content choice is usually driven by either the needs of in-service practitioners, various policy imperatives, or the authority of the field in which the knowledge is produced (or a combination of these). If the knowledge of the field drives content selection, these authors found that content will reflect inclusive education as an issue of learners and their diversity, as an issue of teachers and teaching competence, or as an issue of schools and society.

Lecturers have to navigate three tensions or dilemmas in working with this content (EADSNE, 2010; Walton and Rusznyak, 2020; Rusznyak and Walton, 2021). The first is to work between conceptual generality and contextual specificity. This means finding ways in which to introduce pre-service teachers to the abstract, theoretical knowledge of the field, to the debates and contestations within the field, and to the general principles of inclusive practice; but also to give them contextually specific and practical skills. This balance is generally found in some combination of fieldwork (practicum or work experience) in schools and coursework in higher education. Ensuring that knowledge for inclusive teaching is systematically built across these domains is not easy (EADSNE, 2010). Pre-service teachers are often left to develop their own links between their learning and the teaching practicum (Walton and Rusznyak, 2020; Rusznyak and Walton, 2021). The second tension is between inclusive education as a broad concern that responds to all children vulnerable to marginalization, recognizing intersectionality and common exclusionary pressures – and inclusive education as a specific focus on the most marginalized children–namely those with disabilities (UNESCO, 2018). The third tension relates to ways of balancing pedagogical responses to learner similarities, and to learner differences. On the one hand, a focus on the assumption of classroom diversity would promote access to learning for all through inclusive pedagogy, reducing barriers to learning and participation, and universal design for learning and collaborative practices. On the other hand, a focus on diversity that makes a difference would target high incidence disabilities and learning difficulties, and present evidence-based interventions for individual support.

The form of teacher education for inclusive education seems to pivot on two main approaches: discrete presence or curriculum infusion (Florian and Camedda, 2020; Lehtomäki et al., 2020). If inclusive education has a discrete presence in pre-service teacher education curricula, then it is visible by name in courses or modules or sections. It “becomes an explicit object of study for pre-service teachers, providing an opportunity for the systematic development of concepts” (Walton and Rusznyak, 2017, p. 233). However, such stand-alone courses can lead to inclusive education being seen as an additional rather than a core part of the everyday work that teachers do (Westbrook and Croft, 2015). There is the very real possibility that the ‘ideological screens’ (Bernstein, 2000) of lecturers could lead to particular (problematic) interpretations of inclusive education being privileged. The alternative is to infuse inclusive education into the overall pre-service teacher education curriculum. In this model, “… inclusion forms part of the discursive language and practices of teaching staff” (O’Neill et al., 2009, p. 592). This approach relies on the knowledge different lecturers have of inclusive education and on high levels of collaboration between lecturers. To achieve this, individual and focused courses on inclusive education need to be strengthened, and all subject specific as well as methodology/didactics lecturers will need to learn about the principles and practices of inclusive education, and be willing to infuse these into their content and assessment. A blend of both these approaches seems the most workable approach (Miškolci et al., 2021).

In the next section the study will be contextualized from an international perspective and then the South African setting will be provided, leading to the research aim.

As evident from the introduction, inclusive education has been accepted internationally to ensure that all children receive a formal school education. This required higher education institutions (HEI) to transform their ITE programes. The preparation of student teachers regarding the pedagogy (i.e., an inclusive pedagogy; e.g., Spratt and Florian, 2015) and different teaching strategies (e.g., Universal Design of Learning and differentation; e.g., D’Intino and Wang, 2021; Scott et al., 2022) to be applied in an inclusive classroom is emerging as a focal topic for research. However, it appears that many countries (including South Africa) continue to deem it important to investigate student teachers’ attitudes, perceptions and beliefs toward inclusive education and specifically the inclusion of learners with disabilities. The reason for this could be that it is vital to understand and know how inclusive education is viewed in order to reform and structure initial teacher education (Florian, 2012). Over decades research has shown that determining attitudes, perceptions and beliefs of student teachers is a complex endeavor as there are intricate personal (e.g., experiences, knowledge, training and level of self-efficacy) and contextual (local, national and global) influences (such as political–ideological– and historical backgrounds, socio-economic circumstances and education system structures) that could have an impact on these views. For example, limited educational resources (i.e., human, support, as well as teaching and learning equipment and material) and inadequate training could have an influence on how the practicality of inclusive education is perceived (Nagase et al., 2020; Kunz et al., 2021; Parey, 2021). How an education system is structured (i.e., full inclusion, or mainstream and special education) also seem to have an impact on how positively or negatively the viability of inclusive education is viewed (Nel, 2018; Friesen and Cunning, 2020). In the contexts (especially South Africa) where there is an emphasis on human rights and social justice there is a general belief that inclusive education is the right thing to do, but practical challenges limit the successful implementation thereof (Mdikana et al., 2007; Savolainen et al., 2012; Ainscow, 2014; Nel, 2018; Adigun, 2021; Ismailos et al., 2022). Regarding the transformation of initial teacher education programes, international studies by Pantić and Florian (2015), Florian and Camedda (2020), Lehtomäki et al. (2020) as well as Miškolci et al. (2021) found that ITE programes generally have two main approaches. One is where content knowledge about difference and diversity is added to existing programes through additional courses and the other involves the infusing of inclusive knowledge into existing courses (cf. 2). However, Florian and Camedda (2020), p. 5 argue that both these approaches are insufficient to improve inclusive practices in schools. The reason being that “in addition to being theoretically incompatible, the content is usually decontextualised from the broader pedagogical and curriculum knowledge.”

Policy development in South Africa determining ITE programes had an important impact on this research and led to the research aim.

The policy that initially guided ITE programes after democratization was the Norms and Standards for Educators (NSE) (DoE, 2000). The NSE was introduced before the inception of EWP6 and consequently did not specifically require that ITE programes address inclusive education. However, it was implicitly required as the prerequisite competences indicated knowledge and skills in dealing with diversity, barriers to learning, as well as learning support. In 2006 the Higher Education Quality Committee (HEQC) of the Council on Higher Education (CHE) released the criteria and minimum standards for a national review on the Bachelor of Education (B.Ed) (the focus of this research). One of the aspects which was evaluated was whether the B Ed programes included the promotion and development of dispositions and competences of ITE students to organize learning among a diverse range of learners in diverse contexts (CHE, 2006). In 2011 a policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) was introduced and a revised edition (replacing the 2011 policy) in 2015 (DHET, 2015). The MRTEQ distinctly specifies that inclusive education should be regarded as an important feature of both general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) and specialized pedagogical content knowledge (SPCK). Furthermore, the policy requires that all “B.Ed graduates must be knowledgeable about inclusive education and skilled in identifying and addressing barriers to learning, as well as in curriculum differentiation to address the needs of individual learners within a grade” (DHET, 2015, p. 25). Moreover, it is emphasized that newly qualified teachers must understand diversity in the South African context in order to teach in a manner that includes all learners (p. 64). It is consequently evident that inclusive education should have been addressed in some form in all B.Ed degrees after the ratification of EWP6, not only as a stand-alone module or course, but essentially infused into the whole curriculum. The reason for this is twofold in that inclusivity is a fundamental principle of the constitution RSA (1996), and that South African classrooms consist of learners with diverse learning needs which require that all teachers are enabled to conceptualize and apply an instilled inclusive approach to their teaching. During the HEQC review and the introduction of the MRTEQ, Higher Education Institutions had to revisit and revise their B.Ed curricula.

The group of researchers involved in this project was very much part of these revisions at their institutions in either one of the processes or both. A common realization, when we were brought together to conduct this research, was that being involved in the adaptation and development of new B.Ed curricula made us aware that the concept and implication of inclusive education were not always fully understood by lecturers and student teachers. As this was not researched before in the South African HEI environment as a research group, we agreed to explore lecturers and students’ perceptions in order to inform the transformation of ITE programes. It was important for us to explore perceptions as we wanted to attempt to understand individuals’ (i.e., lecturers and students) opinions, judgment and understanding of the topic under investigation (Munhall, 2008) in order to make apt and relevant recommendations Thus, the primary research aim was: To explore the perceptions of lecturers and students in ITE programes regarding the preparation of pre-service teachers for teaching in inclusive and diverse learning environments.

In the next section the research methodology will be explained.

At the beginning of this research project several meetings were held between the participating researchers to deliberate on the conceptualisation, design and time line. Throughout the 3 year project regular reflective sessions were convened to discuss the progress. In addition, presentations on the advancement of the project were made annually at symposiums focusing on teacher education for inclusion. These symposiums were organized by the participating universities and were an integral part of the overall project in cooperation with VVOB South Africa – education for development and the EU. As the attendees of these symposiums included lecturers, researchers, departmental officials, teachers, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) the feedback during these symposiums was an important item during the reflective sessions.

Since inclusive education is primarily about increasing social justice (Messiou, 2017) this collaborative research project was situated within a transformative paradigm (Mertens, 2009). The transformative paradigm prioritizes issues of social justice and human rights with particular focus on marginalized groups. This paradigm was particularly well suited to this research project which holds a research objective of improving initial teacher education for inclusion in South Africa and in so doing contributing to the social justice and transformation agenda of the country. During the whole research process, from the initial discussions to the interpretation of the findings the researchers recognized that knowledge is socially and historically located within a complex cultural context (Mertens, 2009). Thus, we emphasized that we needed to be aware of our own historical and cultural contexts, as well as respect those of the participants.

A qualitative research approach was employed to gain in-depth and rich data (Creswell and Creswell, 2018).

The participating universities are South African universities from different provinces in the country. Three of them are historically advantaged, urban universities and one is a previously disadvantaged, rural university. All of the participating universities offer B.Ed programes namely Foundation Phase, Intermediate Phase and Senior/FET Phase as full time contact degrees.

All the researchers were active members of B.Ed curriculum development, as well as the lecturing of modules on inclusive education, at their institutions. Thus, their knowledge and experience for this research project were relevant and valuable. The project had a lead coordinator, but each university had a principal researcher who were responsible for managing the data generation at their sites. However, all researchers were involved in their perspective universities’ data generation. The data analysis and interpretation were done as a collective group.

Purposive sampling was used. All Foundation and Intermediate Phase lecturers teaching subject methodologies namely, life skills, social sciences, mathematics and languages were selected to participate in individual interviews. All Foundation and Intermediate Phase fourth year B.Ed students, in the same subject methodologies as the lecturers were selected. Fourth year students were decided on as it was deemed that they already have 3 years of theoretical background and practical teaching experience and could therefore add better insight. All the students were invited to complete an open questionnaire. For the student group interviews every fifth student on the class lists were selected. If this student did not want to partake the next student on the list was invited. In addition, all students who indicated that they want to participate in the interviews were also included. Every group consisted of four to six students which were grouped according to their consequent descending number on the class list. In some instances, students were only two in a group as they indicated they felt more comfortable with this arrangement.

The following codes will be used for the universities:

(1) Participating University A–PUA.

(2) Participating University B–PUB.

(3) Participating University C–PUC.

(4) Participating University D–PUD.

The range of lecturers are between 31 to 65 years old, with only one younger than 30 years. The experience of lecturer participants is from 11 and more years. Only 8 participants had between 0 and 10 years. Based on these years of experience it can be assumed that they could have good insight into what is expected of initial teacher education.

Table 2 presents the different phase methodologies that the lecturer participants were teaching two years prior, as well as during, the research study.

It must be mentioned that the Intermediate and Senior Phase was a combined phase when this research was conducted at one of the universities.

Table 3 represent the number of students studying in the different phases:

The senior phase is included in this table as the two phases were presented as one phase at one university.

After the project was approved by all the relevant institutions’ scientific and ethics structures data was collected.

All selected lecturers were invited via email by the different researchers to a meeting where the scope and purpose of the research was explained to them. Thereafter they were requested to sign informed consent forms if they agreed to participate in the research.

With regard to the students an arrangement was made with lecturers who teach generic modules to use a few minutes of lecture time to explain the research to the students, whereafter voluntary students signed the informed consent forms. A convenient time was then agreed upon to complete the questionnaire in one session. Some students also completed the questionnaire in their own time and brougt it back to the relevant researchers. During another class the researchers again explained the group interview process and voluntary students were then requested to write their names on a time roster. They also added their email addresses in order for the researchers to contact them if needed. The researchers’ contact details were also given to them in case they needed more information. It was clearly indicated by the researchers that the names of the students who are participating in the group interviews could not be guaranteed confidentiality, but that in the reporting of the results anonimity will be ensured.

Table 4 presents the interview questions and the probes that were used:

There was a 48% (N = 31 out of 64) response rate of the lecturer individual interviews.

An open-ended self-structured and self-administered questionnaire with fourth year B.Ed students at three universities were conducted. This questionnaire required a response to a scenario developed with an expert international colleague to ascertain their preparedness to teach in inclusive classrooms. The response rate of the student questionnaires are illustrated in Table 5.

Focus group interviews were conducted across participating universities. The response rate is indicated Table 6.

Question cards were designed to explore issues concerning diversity; teaching and classroom practices; and schools and the education system. These question cards were placed faced down on a table with each group member taking a turn to pick a card. All focus group members then responded to the selected question card until the topic was exhausted before a new card was selected.

The questions are depicted in Table 7:

The research project took into consideration credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability to ensure research rigor (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). Informed consent, with a detailed description of the research and what is expected of participants, was obtained from all participants. Voluntary participation was emphasized and helped guarantee credibility. Interviews were transcribed verbatim to ensure accuracy. Transferability was ensured by eliciting thick descriptions of all aspects related to the methodology, data generation and interpretation. Dependability was ensured by participating universities cross checking the application of the methodology, the collection, transcription and interpretation of data. This was done to moderate procedures, as well as the outcome of the study. An audit trail ensured confirmability as a transparent explanation of all stages taken from the beginning of the study until the report of findings was completed. A crystallization approach which comprises using various data generation methods was also used.

All participating universities experienced challenges in administering the fourth year student questionnaires due to contextual factors which included protest action in the country at the time the questionnaires were to be administered. At some universities this resulted in low numbers of students attending lectures and being available to complete questionnaires. One participating university decided to delay the administration of questionnaires at the end of the specific year and rather re-administer the questionnaires at the start of the next year which resulted in two cohorts of students completing the questionnaire–some at the end of their fourth year and other at the beginning of their fourth year.

Time constraints also challenged the completion of individual interviews with lecturers and students and this portion of the data generation also took more time than was originally intended. Moreover, a large number of students simply indicated that they are not interested in participating in the research. Despite these challenges saturated and rich data was successfully collected and yielded sufficient information that contributed to the overall findings.

One university applied for ethics approval for the research project as a whole. This ethics approval was then used to inform the other three universities’ ethics application to gain gate keeper approval. Thus, formal ethics procedures were followed to obtain an ethics protocol number for conducting the research at each of the four participating universities. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. Confidentiality was addressed by not requiring lecturers or fourth year students to indicate their names or the name of the institution on the questionnaire responses. Pseudonyms were used in the write up of all findings and in transcriptions of interviews. In focus group interviews it is not possible to ensure complete confidentiality and thus participants in focus group interviews were asked to sign a confidentiality document in which they agreed not to talk about the contributions of other group members. Anonymity was ensured by designing questionnaires that did not request any personal information. In writing up findings the use of descriptors that could lead `to identification of participants was avoided. All raw data was kept secured and electronic data shared electronically across sites was password protected.

Thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was used to classify, explore and disclose ideas from all qualitative data collected. Raw data from the open questionnaires and interview transcripts was coded and codes grouped into categories. The data of the lecturers and pre-service teachers were collated as similar themes and categories were identified in their data sets. This allowed for the emergence of overall themes which was identified across all qualitative data sets. Verbatim quotes are added to the different subcategories to substantiate the findings. These quotes are representative of statements made by a wide range of participants.

The following codes are used to indicate if the statement was made by a lecturer or a student:

L = Lecturer.

S–Student.

The themes and categories are depicted in the Table 8.

Three principles which are regarded as central in an inclusive education system (Booth, 2011; Nel, 2013; Ainscow, 2016; Walton, 2016; Slee, 2019a,b; Akabor and Phasha, 2022; Felder, 2022) namely participation, human rights and diversity have been asserted by the participants as important themes in understanding inclusive education. An important aspect linked to participation, which was asserted by a particular lecturer, was that teachers need to understand the barriers that could prevent learners from active participation in the learning process and is reflected in the following quote: A good understanding of inclusive education will enable teachers to understand that there are barriers that prevent learners from active participation in the learning process (L). As a rule, human rights and diversity were consistently emphasized by lecturers and students. For example: It is a system of education that acknowledges and recognizes diversity in a classroom/school. It is based on human right principles, advancing equality as the Constitution reminds of the rights that every child has to education, irrespective of his/her ability (L). Furthermore, within the theme of diversity, it appears that the principle of including everyone is regarded as central by the participants and is best represented by the following quote: All children, regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, linguistic or other conditions, including ‘disabled’ and children from other disadvantaged or marginalized areas or groups have the right to equal quality education, hence they have to be taught in the same classroom as all other children (L). In addition, developing the child holistically in terms of race, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, cognitive abilities and learning styles (S) has also been affirmed as a key feature of diversity.

Contrary to the above view that inclusive education was about including every child in the same classroom the continuous mentioning of special education needs and an assertion of not being trained for these children were evident in both the lecturer and student responses. Tony Booth (as quoted by Slee, 2019a,b, p. 3) calls this conceptual flabbiness when there is a persistence of indulging in the ableist language of special education needs. The following quotes demonstrate the aforementioned theme:

I feel that I was not adequately prepared to deal with those specific incidences of special needs instruction (S).

For my personal perspective I would not know what to do or how to deal with children like that or how to even begin addressing that barriers or to remediate them. I require a lot more in-depth knowledge that I was not adequately prepared for (S).

…I think it uhm takes a special person…not everyone can drop to the level of the child, not everone is prepared to do this, I realised (translated from Afrikaans)… (L).

In the same trend participants reported a negative attitude in the teacher community in that the inclusion of learners with special needs/disabilities in mainstream classrooms continues to be regarded as challenging. This is evident in the following quotes:

The negative attitudes of some host teachers towards inclusion which is based on a lack of knowledge, skills and proper training. Thus, they see the inclusive teaching of learners, especially in ordinary public schools as a major challenge (L).

There is the misconception that learners with disabilities should only be taught in special schools – this mind set should change – we need to shift away from stereotyping learners in terms of disabilities (L).

Yes teachers give up on learners, for example one host teacher said – this child is just waiting to be transferred to a special school – don’t waste your time with him (S).

The theme focusing on the knowledge of inclusion centralized on three sub-themes, namely policies, barriers to learning and teaching inclusively.

Translating policies at a theoretical level into practice requires a massive effort (Naicker, 2000). This is reflected in the findings as lecturer participants seem to know about relevant policies that guide inclusive education in South Africa, including the South African Constitution, in particular the Bill of Rights (Chapter 2), SASA [South African Schools Act], and White Paper 6. However, it was emphasized that especially White Paper 6, which is the primary guiding policy on inclusive education in South Africa, is just about theory with very little practice. It was furthermore affirmed that lectures generally have no in-depth knowledge and a proper understanding of this framework [Salamanca Framework and Inclusive education] in relation to Inclusive Education (L). They added that their own tertiary training was more focussed on their subject content.

Student participants in general asserted that they struggle with using policy documents correctly and effectively. They affirmed that they specifically require more knowledge and skills with the correct organizational and administrative procedures to follow in the process of providing support and accommodating diversity in the inclusive classroom.

Being able to deal with barriers to learning which could cause a breakdown in learning is an integral skill of teaching inclusively (Nel et al., 2022). Overall it appears that both lecturer and student participants understand that dealing with barriers to learning is an important aspect of inclusive education:

Teachers are faced with learners with different abilities, personalities, behaviours, learning styles, disabilities, etc. in their classrooms and schools. It is therefore important for teachers to know how to deal with these learners – that is to include them all in the daily classroom programme (L).

It is important for us as future teachers to be able to examining and transform our practice so that we can in an effective way try to eradicate barriers to learning (S).

Being able to teach inclusively seems to be regarded as modeling inclusiveness and being aware of different categories of learners, but also focusing on specific problems. This is evident in the following quotes:

Our lecturing, assessment, classroom management, etc. has to model inclusiveness. Students will then be able to demonstrate the same. The use of cooperative learning strategies where learners learn from one another, supporting one another and participate in group activities is highly emphasised (L).

I make them aware of different categories of learners within a classroom setting, different barriers to learning and how to firstly identify these barriers to learning. Once they are aware of these barriers, they need to adapt their teaching strategies and teaching styles and in so doing enable learners to overcome these barriers (L).

The knowledge we have obtained is very broad in general. I would’ve appreciated it if our course focussed more on specific problems. We know how to use modelling and scaffolding and code switching but I still would not feel equipped enough to help each learner achieve well (S).

Noticeable in the themes of barriers to learning and teaching inclusively is the seemingly predominant mention of children with specific problems or with different abilities, personalities, behaviors, learning styles, disabilities, etc. and no referral is made to extrinsic barriers to learning, such as systemic-, pedagogical-, social-, and environmental factors that could also result in learning breakdown (Nel et al., 2022). This supports the notion identified by other research that the medical model, where the focus is primarily on the deficit-within-the-child, is still largely in practice (Engelbrecht, 2019).

The persistent disconnect between knowledge and practice has been reported on by a plethora of research studies (e.g., Wrenn and Wrenn, 2009; Walton, 2016; Yin, 2019; Essex et al., 2021; Rusznyak and Walton, 2021). In this research lecturer participants suggested that they felt their own knowledge and lack of training were not sufficient and is not specialized enough to adequately prepare future educators for the inclusive classroom. A further quote confirm:

No, my existing knowledge on inclusive education is totally inadequate – there is firstly a need to identify learners with pedagogical barriers and to adapt teaching strategies accordingly. This is not possible without proper training, guidance and support (L).

The same feeling is emphasized by the student participants:

We are not trained at all, teacher training programmes mainly focus on equipping students with theoretical knowledge on teaching strategies for ordinary mainstream classrooms. We are therefore compelled to only use the knowledge and skills for mainstream classrooms when exposed to inclusive settings (S).

Inclusive education as it stands now is posing challenges as teachers have not been prepared during their training on how to handle the inclusive education classroom (S).

In addition to the belief that there is a lack of knowledge a lack in practical experience has also been reported. In general, it appears as if student participants believe that the curriculum at tertiary level is of strong value to their knowledge and approach to teaching, although lack the teaching and mastering of practical skills needed for inclusive school settings. This belief is affirmed by several assertions by the participants, especially the students, for example:

You see everything is still too theoretical, knowing White Paper 6 and the Constitution from A to Z will only allow you to have a lot of theoretical information on Inclusive Education. The problem lies with the actual teaching process – that is how to apply the content of these documents in our classrooms and lecture sessions and I must say I think we fail in this regard (L).

White Paper 6 is basically my only source of information, however, none of these documents actually touch on practical aspects – for example on how to teach and how to create an inclusive environment in schools and classrooms and are really not very helpful (L).

It is difficult to apply the theory in the classroom, it does not always work (S) (Translated from Afrikaans)

Within the theme of teaching strategies differentiation which is learner-centered as an important teaching strategy was referred to throughout by all participants. Walton and Rusznyak (2020) affirm that developing competences with regard to differentiation in beginner teachers can in a way begin to cumulatively build knowledge-based inclusive teaching practices. The following quotes represent the assertions of the participants:

Differentiate your teaching strategies for example it is important to plan your lesson in such a way to accommodate all learners in your class. This is possible if you cater for visual, practical, auditory, visually impaired and even gifted learners (S)

We must not only cater for the teaching of these learners but also use different assessment strategies when we assess them – think of role play, presentations, assignments – I mean do not only use tests for assessing them (L)

From my first year, the subjects were specified for young children. Many practical subjects like ECD [Early Childhood Development], writing subjects and practical usages. Things I learned about children are that they are all different, with different learning styles and success is reachable, not all same level or time (S)

Learner-centred lessons are important and should be tailored in such a way to cater for and to suit different abilities, learning styles and learner interests (S).

These strategies include peer assessment; teacher assessment; and the use of different assessment tools, for example rubrics, checklists, memoranda, etc. Assessment methods include tests, oral presentations, role play, etc. (S).

In the last few decades two main approaches to addressing differences in an inclusive education system in Initial Teacher Education seem to have appeared (Florian and Camedda, 2020). One focuses on adding content knowledge about inclusive education to programes through additional courses, while the other endeavor to ‘infuse’ or embed it into existing courses (Forlin, 2010; Florian and Camedda, 2020). However, Florian and Camedda (2020) argue that both these approaches are currently lacking to improve inclusive practices in schools. The reason they give is that a theoretical incompatibility remains while the content is decontextualised from the broader pedagogical and curriculum knowledge that pre-service teachers have to learn and be able to apply in the classroom.

Participants in this research reported that the B.Ed curriculum employs an additional model. It seems that B Ed curriculums comprise of one or two standalone modules dealing with the content of inclusive education and that there is no formal content based on inclusive education in most of the modules (subject specific). Teacher educator participants also affirmed that there were specific modules in the B.Ed course that dealt with the specifics of inclusive education and that it was not their main responsibility to teach. The subsequent quotes further affirm the additional model:

In subject field. No not at all. There is no mention of inclusive education or how we must accommodate these children. Even not in my module.not my module outcomes address inclusive education… it is not pertinently mentioned (L)

… So they have learned about inclusive education but it doesn’t always translate into all the other modules (L).

Besides having inclusive education only taught in stand-alone modules the lecturer participants complained about curriculum completion pressure which does not give them time to prepare students to teach inclusively. This is reflected in the following statement:

Time constraints (not enough contact time created on time tables) is the main factor hindering us from preparing pre-service teachers to teach inclusively. We feel pressurised to cover the module content and little time is left for discussions, practical examples and capacity building (L).

The findings presented in the previous section point to teacher education for inclusion as a complex endeavor. It appears as if the successful preparation of teachers for teaching in inclusive and diverse learning environments can be divided into a number of dynamic, imbricated and mutually constituting ‘systems’ which are discussed below.

The first system that emerges from the findings is the knowledge base of inclusive education. It is evident from the findings that there are different emphases and nuances of understanding of inclusive education among lecturers. While most are positive about the value of inclusivity, there seems to be considerable variation in what is regarded as the knowledge required for effective inclusive teaching. Issues here include the relative merit of theoretical and practical knowledge, the extent to which inclusive education is similar to or separate from special education, and the relative weight that should be given to general pedagogical strategies (like cooperative learning and differentiation) and individual support based on ‘categories of learners’. Debates in the wider field of inclusive education internationally and in South Africa about its definition, scope and practice (Messiou, 2017; Walton, 2017; Nel, 2018; Engelbrecht, 2019; Slee, 2019a,b) have resulted in an opaque, even unstable knowledge base, which seem to create uncertainty among lecturers and in turn impacts the teacher education curriculum.

Various institutions impact initial teacher education for inclusion. Each can be conceptualized as a system in its own right, constituted by a complex network of practices and relationships. One such system is the Higher Education Institution. Here it must be noted that teacher education for inclusion is impacted by the particular configurations of the institution, including how courses and modules are constituted, time constraints and class sizes, and opportunities for learning classroom-based skills. These are, in turn, influenced by developments in the South African higher education system which regulates teacher education and has, over the years of the study, mandated changes to teacher education curricula (see introduction). At an even broader level, we can identify the national and supranational inclusive education policy regime that impacts teacher education. The awareness among participants of the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action, the South African Schools Act and Constitution as foundational documents for inclusive education in South Africa, together with frequent mentions of EWP6 is important to note. While these policies and laws might suggest a fixed point in the knowledge base in contrast to the claim in 9.1 above, they are, in fact, seen as ‘impractical’ by participants and rely on effective organizational structures for implementation.

Another system that emerges in the research is the schooling system where pre-service teachers conduct their field experience. Many teacher educator participants in this study confirm that many classrooms do not support learning for inclusive teaching, and may, in fact, undermine it. This is consistent with research elsewhere in the world that finds inclusive principles not enacted in schools, and inclusive teaching not always expected of teachers (e.g., Srivastava et al., 2015; Robinson, 2017; Carrington et al., 2022).

Lecturers themselves tend to be overlooked in the literature on teacher education for inclusion, and the findings presented in this research draw attention to them individually and collectively as a ‘system’ that needs consideration. The findings show some lecturers who seem confident with their subject matter and see their role as ‘modeling’ inclusive teaching through all aspects of pedagogy and assessment. Mostly, though, lecturers are less confident in their ability to prepare pre-service teachers for inclusive classrooms. They express ‘inadequate’ knowledge of inclusive teaching and identify a lack of guidance and support for their task. In doing so, these lecturers reflect international concerns about the lack of professional development opportunities for lecturers, especially in times of policy change (Czerniawski, 2018; Subban et al., 2022; Larios and Zetlin, 2023). It is a concern that the teacher educator participants in this study made scant reference to their colleagues and the potential for collaborative professional learning for inclusive education. The only reference was to specific ‘lecturer professional development workshops’ at two HEIs, despite the growing body of international literature that talks of workplace professional learning in communities of practice.

Opfer and Pedder (2011) assert that students themselves constitute systems which reflect their own identities, experiences and predispositions. The findings show that pre-service teachers are eager to learn to be inclusive in their practice, although many reflect prevalent societal deficit approaches to those not deemed ‘normal’. Pre-service teachers expect their university education to provide them with practical skills to support diverse learners in the classroom. The pre-service teachers who participated in this study believe that they have not been given ‘practical tips’ and that theory does not readily translate into classroom practice. We see this complaint reflected in broader concerns about university based pre-service teacher education, where a disconnect between coursework and field experience is identified as a central problem (Lancaster and Bain, 2021).

Pre-service teacher education for inclusion in South Africa is a complex system, constituted by a number of interrelated and dynamic sub-systems and serves as both warning and direction for the way forward.

The warning is that addressing the challenge of successful preparation of teachers for inclusive classrooms will not be possible if all the efforts are directed toward improvement in one system. In this regard, the research team is reminded of a conversation in a plenary session of one of the project symposia. A school principal told the floor that she could not expect to advance inclusive education at school level until the universities started delivering beginner teachers who were able to teach inclusively. The riposte from a university teacher educator was that universities could not expect to deliver beginner teachers able to teach inclusively until schools offered field experience opportunities that modeled inclusive practices. The interconnection of systems was clear here, and illustrates that addressing the problem will require interventions across constituent systems.

The very interconnectedness of systems offers hope and a way forward. Complexity science shows that change in one system will impact other systems, and that can be used to bring about overall change (Hager and Beckett, 2022). As we present recommendations from the project in the following section, we are not suggesting one or another would solve the problem, but rather that incremental changes across all systems could be expected to have a cumulative positive effect.

Findings from this study support the following recommendations:

• Research in the field of inclusive education needs to be strengthened in South Africa to extend and deepen the knowledge base to inform teacher education curricula.

• Curricula need to be critically reviewed to ensure that beginner teachers learn both theoretically informed and contextually relevant pedagogical practices suited to inclusive classrooms. As well as having dedicated modules on aspects of inclusive education, ITE should embed inclusive ways of teaching in all methodology subjects to enhance students’ knowledge, skills, practices and understanding of inclusive education.

• Higher Education Institutions should recognize their role in either enabling or constraining the development of inclusive teaching competence in pre-service teachers. This research points to the importance of institutional commitment to inclusive education and concomitant action appropriate in each context. This may include revisiting courses, timeframes and timetables, and fieldwork opportunities that extend beyond ordinary schools.

• Lecturers need time and opportunities for professional learning for inclusive education. Workshops may be valuable in this regard, but the international literature suggests that collaborative learning in communities of practice may be more efficacious.

• Schools need to accelerate their progress toward being more inclusive in order to provide contexts where pre-service teachers can observe good inclusive teaching and practice newly learned skills. It is important that the messages that pre-service teachers receive at university about respect for diversity and promoting a values orientated, transformative approach in the classroom are not undermined by their experience in schools.

• Pre-service teachers should be given opportunities to critically interrogate their assumptions about difference, disability, and how schools and schooling may be complicit in marginalization and exclusion. Their eagerness to teach effectively to benefit diverse learners should be harnessed through creative opportunities to expand their knowledge and skills.

It is clear that understanding and the practicing of inclusive education does not happen automatically with HEIs taking an approach of only offering stand-alone modules on inclusive education. Pre-service teachers express that they want to understand how the principles of inclusive education translate into practice in their teaching context. This needs to be demonstrated by subject specialists who understand inclusive education sufficiently well that they can model inclusive pedagogy, assessment and classroom management. Given that lecturers express a lack of knowledge about inclusive education, professional learning opportunities need to be prioritized for this infusion to be realized.

While a number of pre-service teachers who participated in our study show willingness to teach diverse learners, they are mostly not confident that they have the requisite skills to do so. Lack of practical experience on how to teach in inclusive settings, coupled with what is seen as too much focus on theory and superficial exposure to White Paper 6, are viewed as drawbacks in preparing pre-service teachers for inclusive classrooms. The narratives pre-service teachers receive is that disability and learning difficulties are the defining issues in inclusive education. This detracts from a holistic view of learners as having intersectional identities and an acknowledgement of other differences (language, culture, sexuality etc.) that may impact learning. The lack of capacity, negative attitudes and prejudice among host teachers adversely impact on the guidance and support given to pre-service teachers during work-integrated learning.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

This study involved human participants and were approved by the relevant ethics’ committees of the participating universities. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MN was the project leader and main author writing 80% of the article. JH wrote 20% of the article. TB, CB, NP, GA, and SM contributed to the editing of the article. All the authors were involved in the research conceptualization and data collection.

The South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) embarked on a project called the Teaching and Learning Capacity Development Improvement Project (TLCDIP), which was funded by the European Union (EU).

We would like to thank the European Union (EU) for the generous funding given and VVOB South Africa who managed the project. We also appreciate the support provided by the management structures of the participating universities, i.e. North-West University, University of Witwatersrand, University of Fort Hare, University of the Free State and the Central University of Technology. We would also like to thank the research assistants Anne-Marie DeNysschen, Nicolaas Louw, and Yolande Korkie.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adigun, O. T. (2021). Inclusive education among pre-service teachers from Nigeria and South Africa: A comparative cross-sectional study. Cogent Educ. 8:1930491. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2021.1930491

Ainscow, M. (2014). “Struggling for equity in education: the legacy of Salamanca” in Inclusive education: Twenty Years after Salamanca. eds. F. Kiuppis and R. S. Hausstatter (New York: Peter Lang), 41–56.

Ainscow, M. (2016). “Introduction: the collective will to make it happen” in Struggles for Equity in Education: The Selected Works of Mel Ainscow. ed. M. Ainscow (London: Routledge), 1–18.

Akabor, S., and Phasha, N. (2022). Where is Ubuntu in competitive South African schools? An inclusive education perspective. Int. J. Incl. Educ., 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2022.2127491

Bentley-Williams, R., Grima-Farrell, C., Long, J., and Laws, C. (2017). Collaborative partnership: developing pre-service teachers as inclusive practitioners to support students with disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 64, 270–282. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2016.1199851

Booth, T. (2011). The name of the rose: inclusive values into action in teacher education. Prospects 41, 303–318. doi: 10.1007/s11125-011-9200-z

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. J. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bukko, D., and Liu, K. (2021). Equity consciousness and equity literacy. Front. Educ. 6:586708. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.586708

Carrington, S., Lassig, C., Maia-Pike, L., Mann, G., Mavropoulou, S., and Saggers, B. (2022). Societal, systemic, school and family drivers for and barriers to inclusive education. Aust. J. Educ. 66, 251–264. doi: 10.1177/00049441221125282

CHE. (2006). Higher Education Quality Committee. National Review of the Bachelor of Education. Council on Higher Education. Available at: http://www.che.ac.za. (Accessed on November 8, 2019).

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D.. (2018). Research Design–Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approach. 5th. United States: Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

D’Intino, J. S., and Wang, L. (2021). Differentiated instruction: A review of teacher education practices for Canadian pre-service elementary school teachers. J. Educ. Teach. 47, 668–681. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2021.1951603

De Beco, G. (2022). The right to ‘inclusive’ education. Mod. Law Rev. 85, 1329–1356. doi: 10.1111/1468-2230.12742

Department Statistics South Africa. (2019). Sustainable Development Goals: Country Report 2019. Available at: https://www.statssa.gov.za/MDG/SDGs_Country_Report_2019_South_Africa.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2022).

DHET. (2015). Revised Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications. Department of Higher Education and Training. Available at: www.gpwonline.co.za. (Accessed on November 8, 2019).

DHET. (2017). Knowledge and Practice Standards for Inclusive Teaching. Available at: https://www.jet.org.za/clearinghouse/projects/primted/standards/inclusive-educationstandards/teaching-standards-for-inclusive-teaching-for-beginner-teachers-20170830.pptx/view. (Accessed on November 8, 2019).

DoE. (2000). Norms and Standards for Educators. Government Gazette. Pretoria: Department of Education.

DoE. (2001). Education White Paper 6: Special Needs Education. Building an Inclusive Education and Training System. Pretoria: Department of Education.

EADSNE. (2010). Teacher Education for Inclusion: International Literature Review. European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. Available at: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/te4i-international-literature-review_TE4I-Literature-Review.pdf. (Accessed on November 8, 2019).

EADSNE. (2012). Teacher Education for Inclusion: Profile of Inclusive Teachers. European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. Available at: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/te4i-profile-of-inclusive-teachers_Profile-of-Inclusive-Teachers-EN.pdf. (Accessed on November 8, 2019).

Engelbrecht, P. (2019). The implementation of inclusive education: international expectations and South African realities. Tydskrif Geesteswetenskappe 59, 530–544. doi: 10.17159/2224-7912/2019/v59n4a5

Essex, J., Alexiadou, N., and Zwozdiak-Myers, P. (2021). Understanding inclusion in teacher education–a view from student teachers in England. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 1425–1442. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1614232

Felder, F. (2022). The Ethics of Inclusive Education. Presenting a New Theoretical Framework. London: Routledge.

Florian, L. (2012). Preparing teachers to work in inclusive classrooms: key lessons for the professional development of teacher educators from Scotland’s inclusive practice project. J. Teach. Educ. 63, 275–285. doi: 10.1177/0022487112447112

Florian, L., and Camedda, D. (2020). Enhancing teacher education for inclusion. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 4–8. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1707579

Forlin, C. (2010). Teacher education reform for enhancing teachers’ preparedness for inclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 14, 649–653. doi: 10.1080/13603111003778353

Forlin, C., and Chambers, D. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: increasing knowledge but raising concerns. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 17–32. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850

Friesen, D. C., and Cunning, D. (2020). Making explicit pre-service teachers’ implicit beliefs about inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 1494–1508. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1543730

Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., and Vantieghem, W. (2021). Exploring pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices about two inclusive frameworks: universal Design for Learning and differentiated instruction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 107:103503. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103503

Hager, P., and Beckett, D. (2022). Refurbishing learning via complexity theory: Introduction. Educ. Philos. Theory. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2022.2105696

Heng, L., Quinlivan, K., and Du Plessis, R. (2022). Deconstructing initial teacher education: a critical approach. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 609–621. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1708982

Ismailos, L., Gallagher, T., Bennett, S., and Li, X. (2022). Pre-service and in-service teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy beliefs with regards to inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 175–191. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1642402

Karhu, A., Närhi, V., and Savolainen, H. (2019). Check in–check out intervention for supporting pupils’ behaviour: effectiveness and feasibility in Finnish schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 136–146. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1452144

Klang, N., Olsson, I., Wilder, J., Lindqvist, G., Fohlin, N., and Nilholm, C. (2020). A cooperative learning intervention to promote social inclusion in heterogeneous classrooms. Front. Psychol. 11:586489. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586489

Kunz, A., Luder, R., and Kassis, W. (2021). Beliefs and attitudes toward inclusion of student teachers and their contact with people with disabilities. Front. in Educ. 6:650236. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.650236

Lancaster, J., and Bain, A. (2021). Do judgements about pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy covary with their capacity to design and deliver evidence-based practice? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 827–842. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1579873

Larios, R. J., and Zetlin, A. (2023). Challenges to preparing teachers to instruct all students in inclusive classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 121:103945. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103945

Lehtomäki, E., Posti-Ahokas, H., Beltrán, A., Shaw, C., Edjah, H., Juma, S., et al. (2020). Teacher Education for Inclusion: Five Countries Across Three Continents. Background Paper Prepared for the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report on Inclusion and Education. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373804 (Accessed September 3, 2022).

Loreman, T. (2010). Essential inclusive education-related outcomes for Alberta preservice teachers. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 56, 124–142. doi: 10.11575/ajer.v56i2.55394

Maher, A. J., Thomson, A., Parkinson, S., Hunt, S., and Burrows, A. (2022). Learning about ‘inclusive’ pedagogies through a special school placement. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 27, 261–275. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2021.1873933

McKenzie, J., Kelly, J., Moodley, T., and Stofile, S. (2020). Reconceptualising teacher education for teachers of learners with severe to profound disabilities. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 27, 205–220. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1837266

Mdikana, A., Ntshangase, S., and Mayekiso, T. (2007). Pre-service educators’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 22, 125–134.

Messiou, K. (2017). Research in the field of inclusive education: time for a rethink? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 21, 146–159. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1223184

Miškolci, J., Magnússon, G., and Nilholm, C. (2021). Complexities of preparing teachers for inclusive education: case-study of a university in Sweden. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 562–576. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1776983

Munhall, P. L. (2008). “Perception” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. ed. L. M. Given (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage)

Nagase, K., Tsunoda, K., and Fujita, K. (2020). The effect of teachers’ attitudes and teacher efficacy for inclusive education on emotional distress in primary school teachers in Japan. Front. Educ. 5:570988. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.570988

Naicker, S. M. (2000). From apartheid education to inclusive Education: The challenges of transformation. International education summit: For a Democratic Society at Wayne State University Detroit, Michigan U.S.A., June 26–28, 2000. Available at: http://www.wholeschooling.net/WS/WSPress/FromAparthiedtoInclEduc.pdf From Aparthied to Incl Educ.pdf (wholeschooling.net)

Nel, M. (2013). “Understanding inclusion” in Embracing Diversity through Multi-Level Teaching. eds. A. Engelbrecht and H. Swanepoel (JUTA: Cape Town)

Nel, M. (2018). Inclusive Education: All about Humanity and yet… Inaugural Lecture Presented on 14 September 2018 at North-West University South Africa. Inclusive education: all about Humanity and Yet… /Mirna Nel. Available at: nwu.ac.za (Accessed September 3, 2022).

Nel, M., Nel, N. M., and Hugo, A. (2022). “Inclusive education: an introduction” in Learner Support in a Diverse Classroom. eds. M. Nel, N. M. Nel, and M. Malindi. 3rd ed (Pretoria: Van Schaik), 3–40.

O’Neill, J., Bourke, R., and Kearney, A. (2009). Discourses of inclusion in initial teacher education: unravelling a New Zealand ‘number eight wire’ knot. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.00

Opfer, V. D., and Pedder, D. (2011). Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 376–407. doi: 10.3102/0034654311413609

Pantić, N., and Florian, L. (2015). Developing teachers as agents of inclusion and social justice. Educ. Inq. 6. doi: 10.3402/edui.v6.27311

Parey, B. (2021). Exploring positive and negative teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion of children with disabilities in schools in Trinidad: implications for teacher education. Int. J. Incl. Educ., 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1902004

Pizana, R. F. (2022). Collective efficacy and co-teaching relationships in inclusive classrooms. Int. J. Multidiscip. 3, 1812–1825. doi: 10.11594/ijmaber.03.09.22

Robinson, D. (2017). Effective inclusive teacher education for special educational needs and disabilities: some more thoughts on the way forward. Teach. Teach. Educ. 61, 164–178. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.09.007

Rusznyak, L., and Walton, E.. (2021). Inclusive Education in South African Initial Teacher Education Programmes. Knowledge and Practice Standards for Inclusive Education in Teacher Education Project. Report for the Teaching and Learning Development Capacity Improvement Programme which is being Implemented through a Partnership between the Department of Higher Education and Training and the European Union.

Savolainen, S., Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., and Malinen, O.-P. (2012). Understanding teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy in inclusive education: implications for preservice and in-service teacher education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 27, 51–68. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2011.613603

Scott, L. R., Bruno, L., Gokita, T., and Thoma, C. A. (2022). Teacher candidates’ abilities to develop universal design for learning and universal design for transition lesson plans. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 333–347. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1651910

Sharma, U., and Sokal, L. (2015). The impact of a teacher education course on pre-service teachers’ beliefs about inclusion: an international comparison. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 15, 276–284. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12043

Slee, R. (2019a). Belonging in an age of exclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 23, 909–922. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1602366

Slee, R., and Allan, J. (2001). Excluding the included: A reconsideration of inclusive education. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 11, 173–192. doi: 10.1080/09620210100200073

Spratt, J., and Florian, L. (2015). Inclusive pedagogy: from learning to action. Supporting each individual in the context of ‘everybody’. Teach. Teach. Educ. 49, 89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.006

Srivastava, M., De Boer, A., and Pijl, S. J. (2015). Inclusive education in developing countries: a closer look at its implementation in the last 10 years. Educ. Rev. 67, 179–195. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.847061

Stunell, K. (2021). Supporting student-teachers in the multicultural classroom. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 44, 217–233. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1758660

Subban, P., Woodcock, S., Sharma, U., and May, F. (2022). Student experiences of inclusive education in secondary schools: A systematic review of the literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 119:103853. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103853

Swain, K. D., Nordness, P. D., and Leader-Janssen, E. M. (2012). Changes in preservice teacher attitudes toward inclusion. Prev. Sch. Fail. 56, 75–81. doi: 10.1080/1045988X.2011.565386

Tullis, J. G., and Goldstone, R. L. (2020). Why does peer instruction benefit student learning? Cogn. Res. 5, 15–12. doi: 10.1186/s41235-020-00218-5

UN. (2016). General Comment No. 4 (2016) on the Right to Inclusive Education. Available at: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRPD/C/GC/4&Lang=en.

UNDO, UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank. (1990). World Conference on Education for all Meeting Basic Learning needs in Jomtien, Thailand. New York: UNICEF House. Available at: https://bice.org/app/uploads/2014/10/unesco_world_declaration_on_education_for_all_jomtien_thailand.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2022).

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Salamanca, Spain, 7–10 June. Available at: http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

UNESCO. (2018). Concept Note for the Global Education Monitoring Report on Inclusion. Paris: United Nations Education Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265329. (Accessed September 3, 2022).

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Available at: http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2022).

United Nations. (2016). General Comment No. 4 on the Right to Inclusive Education, Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no-4-article-24-right-inclusive (Accessed September 3, 2022).

Vitello, S. J., and Mithaug, D. E. (Eds.). (1998). Inclusive Schooling: National and International Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Waitoller, F. R., and Thorius, K. K. (2015). Playing hopscotch in inclusive education reform: examining promises and limitations of policy and practice in the US. Support Learn. 30, 23–41. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12076

Walton, E. (2017). Inclusive education in initial teacher education in South Africa: practical or professional knowledge? J. Educ. 67, 101–128. doi: 10.17159/2520-9868/i67a05