- 1School of Foreign Languages, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China

- 2School of Foreign Languages, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

- 3School of Foreign Languages, Tianjin University of Commerce, Tianjin, China

Based on 601 articles on feminist translation theory published in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) in the last 20 years from 2002 to 2021, this article draws a scientific knowledge map and makes a visual analysis of the research articles on feminist translation theory in China using CiteSpace as a visual tool. It was found that (1) both the cooperation between researchers and between research institutions in the domain of feminist translation research in China was not strong; (2) the focus of feminist translation research in China is mainly on feminism, feminist translation theory, feminist translation, and translation; (3) according to the map of the time zone and keywords mutation, feminist translation research in China is constantly moving toward a decline after fast development.

1. Introduction

As the Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI) program became very popular in China, increasingly more scholars started to study translation theory (Wang et al., 2022). Feminist translation is one of the important theories in this field, which has attracted much attention in recent years. On this note, to gain insights into how feminist translation research in China will evolve going forward, we explored feminist translation research in China by using CiteSpace.

In the 1960s and 1970s, with the advent of women's liberation in Europe and the United States, feminist literary criticism and cultural feminism theories were developed. In the 1980s, influenced by the feminist movement and the “cultural turn” in translation studies, feminist translation theory emerged in the West. Feminist translation theory sees women as having and needing to deploy the agency and the power to change texts, create texts, select texts that are of use and interest to them, and decline to work on texts that are detrimental to women's interests and lives. Feminists call for the use of language to pursue gender equality and use translation to resist such statements as “Translations are like women: ugly if they are faithful, and unfaithful if they are beautiful,” which shows language sexism in a patriarchal society (Simon, 1996, p. 39).

Representative figures of feminist translation theory include Sherry Simon and Barbara Godard et al., and representative works include Simon's (1996) book Gender in Translation: Cultural Identity and the Politics of Transformation and Godard's (1990) article “Theorizing feminist discourse/translation,” the former of which marked the birth of western feminist translation theory (Hu et al., 2013). In the West, feminist translation theory has flourished over the development of the past several decades.

In the 1980s, Professor Zhu Hong introduced feminist translation theory to China, but the theory did not attract much attention in the field of translation until the 1990s. Later, Liao (2002) published the article “Rewriting Myths: Feminism and Translation Studies” in the Journal of Foreign Languages and Literature, which was regarded as the beginning of Chinese feminist translation studies. Till now, feminist translation theory research has had a history of 20 years in China, and it is necessary to review how it was developed, which can not only help us explore its frontiers in China nowadays but also forecast its future research trends.

2. Method

This study intends to answer the following questions: (1) Which research teams or researchers are engaged in feminist translation research in China and what is their research status? (2) What are the hot spots of feminist translation research in China? (3) What are the main problems or bottlenecks of Chinese feminist translation research? and (4) What is the future direction of feminist translation research in China?

All the articles retrieved are from the academic journal in CNKI. In the collection of data, “feminist translation” was decided as the subject, and the retrieval time was from 2002 to 2021 (the deadline is 10 June 2021). The language was set to Chinese. Non-research articles, such as book reviews and calls for articles, as well as articles not related to the topic, were manually deleted. Finally, 601 valid articles were retrieved, and each article includes key information such as the author's name, institution, article's keywords, title, abstract, and publication year.

The “export/references” tool of CNKI was used to export the data of 601 articles in the format of Refworks, and the exported document was named Download_XXX. The data were imported into CiteSpace and then converted by the Data function in CiteSpace. After creating a new project, a series of tables and graphs were generated by CiteSpace to analyze the development of feminist translation research in China.

3. Results and analysis

3.1. Overall development of feminist translation research in China

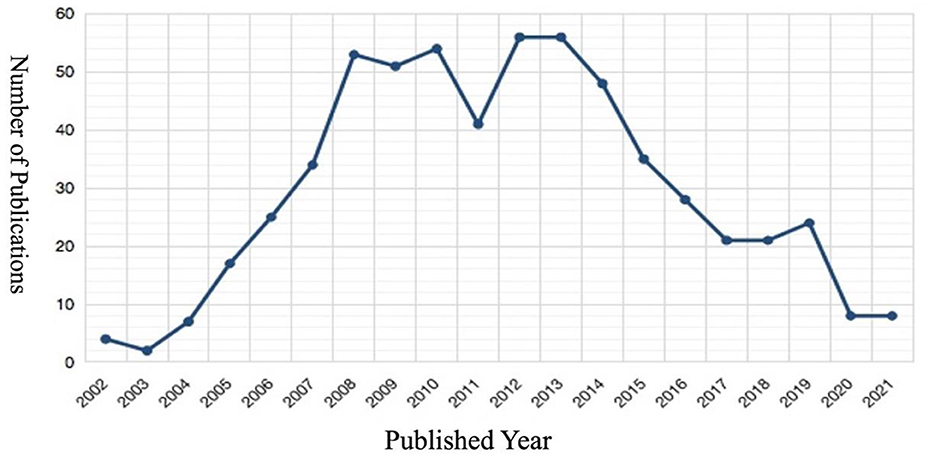

If the academic field is regarded as an industry, this diagram can be analyzed using four stages of the industry life cycle (formation, growth, maturity, and decline) and the tipping points (He and Luo, 2020). As indicated in Figure 1, 2002 can be viewed as the formation period of Chinese feminist translation theory with only four articles published; 2003–2008 can be regarded as its growth period, and at that time, the number of publications increased rapidly. In 2008, the number of published articles in this field reached more than 50, four times that of 2004, which shows the fast development of feminist translation theory in China. The period from 2009 to 2013 can be seen as a mature one. Although the number of published articles declined in 2011, the number (about 40) was relatively large compared with that of other periods. In 2013, the number of published articles peaked at nearly 60 articles. This stage can be regarded as the most critical period for the development and prosperity of Chinese feminist translation theory.

Later, the period between 2014 and 2021 witnessed a sharp decline in the number of articles published in this field. Although the number of articles published in 2018–2019 has increased, the number is not large compared with that of the mature period. Influenced by time (only 6 months of data), the number of published articles is <10. According to the trend in Figure 1, it is expected that the number of published articles in 2021 will be no more than that in 2020.

As shown in Figure 1, although Chinese feminist translation research has gradually developed in the past two decades, the number of articles published in this field has never exceeded 60 per year. It can be seen that the voice of feminist translation theory in China is much weaker than other translation theories in China (Yang L., 2007).

3.2. Analysis of knowledge map of research institutions

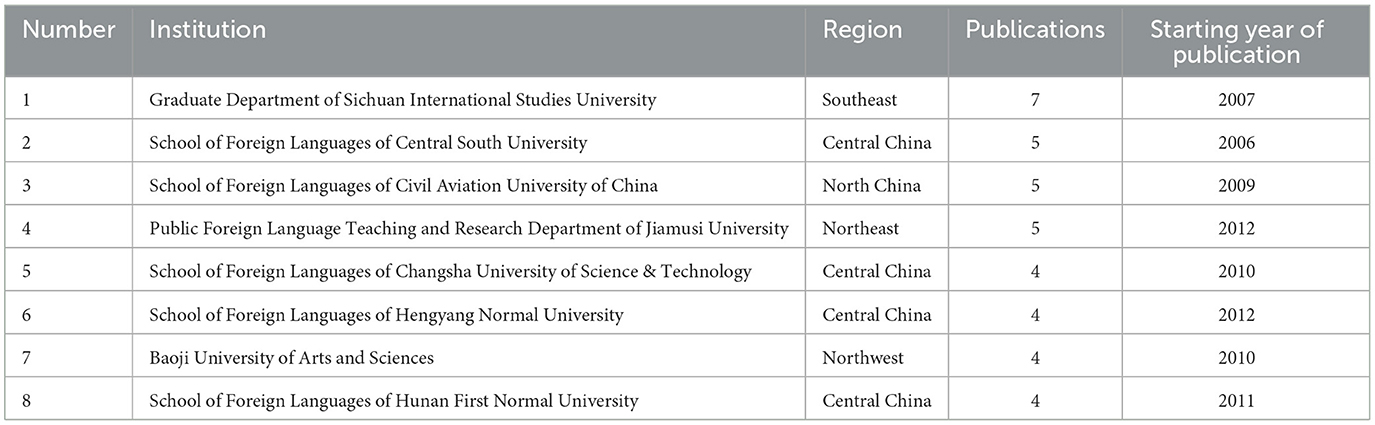

The map of Chinese high-yield institutions in feminist translation research generated by CiteSpace is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Bibliometric analysis of research institutions of feminist translation research in China from 2002 to 2021.

In Figure 2, a circle (hereinafter referred to as a node) represents a research institution. The larger the node is, the more articles that were published by the institution. The connection between the nodes represents the cooperation between the institutions. The thickness of the connection is proportional to the volume of cooperative publications between the institutions. According to Figure 2, eight main institutions in China have been committed to the research on feminist translation. This is because all articles analyzed by CiteSpace are in Chinese, and the map is in Chinese as well. Therefore, detailed information on these large nodes is shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, foreign language institutions, especially the Sichuan University of Foreign Languages (now renamed Sichuan International Studies University), have made great achievements in research on feminist translation theory in China. This is because Liao, who is regarded as the first to introduce feminist translation theory into China, once taught at this university. Non-foreign language institutions, however, such as the School of Foreign Languages of Central South University, the School of Foreign Languages of the Civil Aviation University of China, and the Public Foreign Language Teaching and Research Department of Jiamusi University, have also contributed to the development of feminist translation theory in China.

Judging from the starting year and the number of articles published by the research institutions, the School of Foreign Languages of Central South University was the first to make achievements in the field of feminist translation theory, but the number of published articles was not large. Later, the School of Foreign Languages of the Civil Aviation University of China, the Public Foreign Language Teaching and Research Department of Jiamusi University, and the School of Foreign Languages of Changsha University of Science and Technology began to publish articles in the field of feminist translation, making feminist translation theory more popular in China. The Graduate Department of Sichuan International Studies University is currently the institution with the largest number of publications in this field.

Judging from the extent of cooperation between these institutions shown in Figure 2, the cooperation among various research institutions was not close. This may be caused by the fact that feminist translation studies is still a relatively new subject in China.

3.3. Analysis of knowledge map of researchers

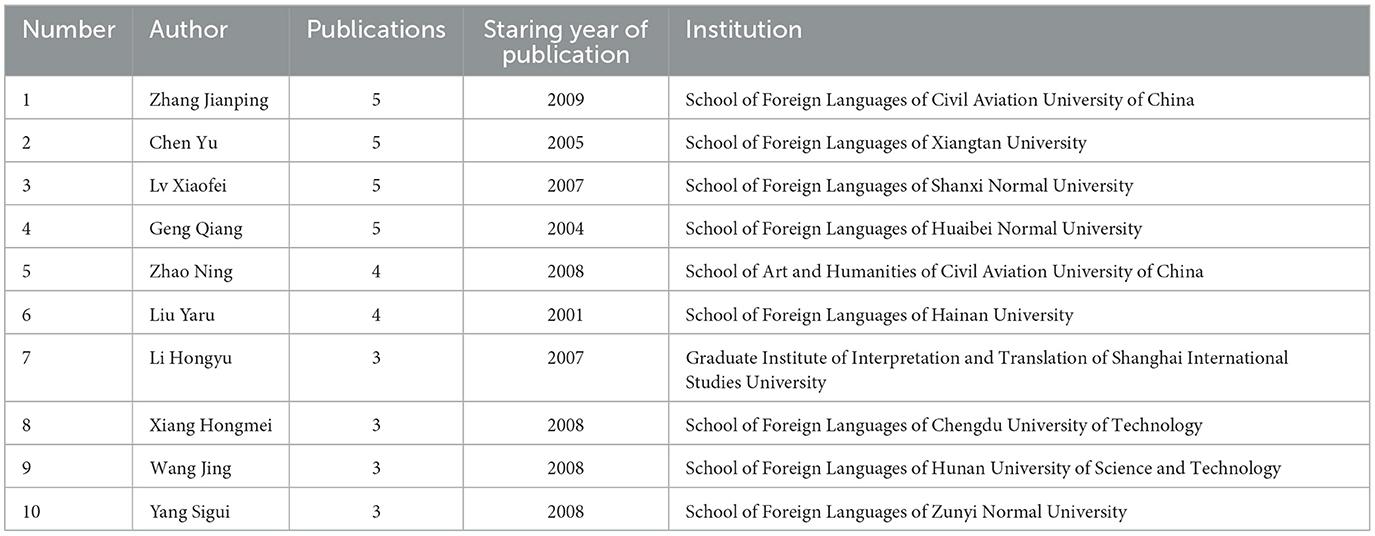

Researchers play a crucial role in promoting the development of a discipline. The analysis of researchers will help to understand the cooperative relationship between researchers in the same field and find the right approach to promote the sustainable development of a field (Liu and Chang, 2018). The map of researchers in the field of feminist translation research generated by CiteSpace is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Bibliometric analysis of researchers of feminist translation research in China from 2002 to 2021.

As depicted in Figure 3, the most prolific authors in the field of feminist translation studies in China include “张建萍” (Zhang Jianping), “耿强” (Geng Qiang), “吕晓菲” (Lv Xiaofei), “李红玉” (Li Hongyu), and others. However, the cooperation between these scholars needs to be strengthened. Only a few groups of scholars, such as “赵宁” (Zhao Ning) and “张建萍” (Zhang Jianping), “穆雷” (Mu Lei) and “李红玉” (Li Hongyu), and “李奕” (Li Yi) and “戴日新” (Dai Rixin), have close relationships. To better study these authors and their published articles, the information on the top 10 authors is shown in Table 2.

From Table 2, 刘亚儒 (Liu) was the first to study feminist translation theory in China among the top 10 prolific authors. But the number of Liu's articles in this field is relatively few compared with that of 陈钰 (Chen Yu) and 张建萍 (Zhang Jianping), who have worked on feminist translation theory since 2005 and 2009, respectively, and published five related articles so far. In addition, 吕晓菲 (Lv Xiaofei), 赵宁 (Zhao Ning), 耿强 (Geng Qiang), and other researchers have also paid attention to feminist translation theory in the 2010s, expanding the influence of feminist translation theory in China. However, the number of articles in this field was relatively small, and even the most prolific scholars only published five related articles, which is not conducive to the progress of this discipline in China.

3.4. Analysis of research hotspots

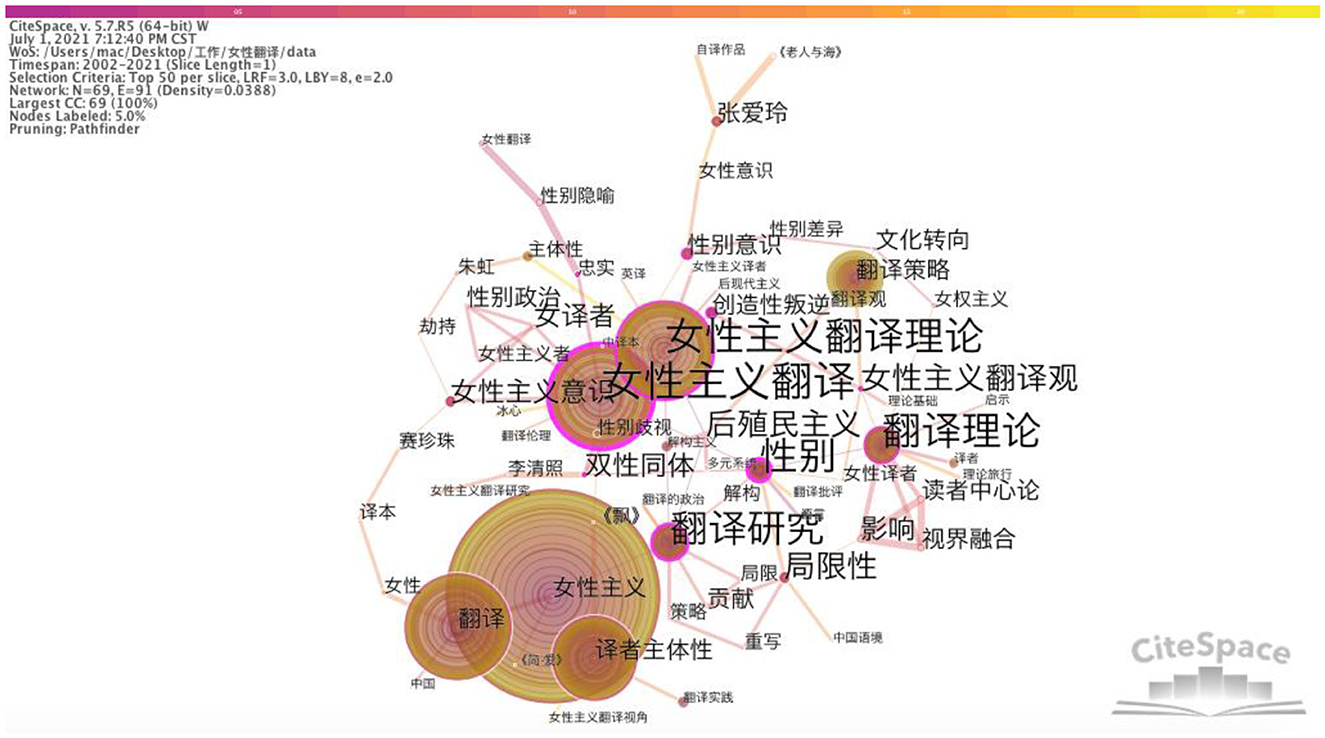

Keywords represent the core content of the article. If a keyword appears repeatedly in a research field, it must be a hotspot in this field (Feng et al., 2014). The higher the recurrence frequency of a keyword is, the hotter the research on it is (Liu and Chang, 2018). The clustering relationship of keywords is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Network of keywords from publications on feminist translation research in China (2002–2021).

As shown in Figure 4, the nodes are composed of rings of different colors. Each ring corresponds to the time when the keyword appears. Moreover, the color represents time, which can be seen at the top of Figure 4. The thickness of the ring is proportional to the frequency of the keyword appearing in the corresponding time zone. The connection between nodes represents their co-occurrence relationship. The thicker the connection is, the closer the co-occurrence relationship is. The lines between the nodes are in different colors, which correspond to the time divisions when the keywords first co-occur.

Figure 4 shows that “女性主义” (feminism), “女性主义翻译理论” (feminist translation theory), and “女性主义翻译” (feminist translation) were the key topics in Chinese feminist translation research in the past two decades. “Feminism” is the largest node, and the other two nodes are also more prominent than other keywords. The color of the ring, from red in the core to yellow in the outer ring, indicates that the research on these three topics has always been hot from 2002 to 2021. The connections of different nodes are extremely complex, which shows that the research on feminist translation is relatively mature and has formed a huge network. In addition, the emergence of small nodes such as “Gone with the Wind,” “Jane Eyre,” “The Old Man and the Sea,” and “Secret Garden” indicates that feminist translation research in China began to combine studies with practical research at that time.

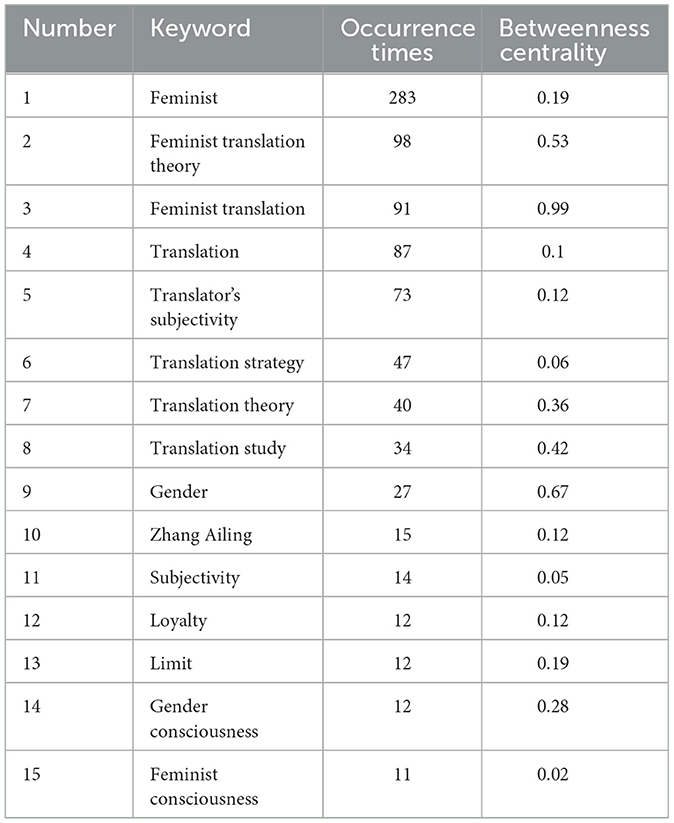

According to the information generated by CiteSpace, the top 15 keywords are extracted, and their betweenness centrality is listed in Table 3.

Betweenness centrality is an index reflecting the importance of keywords in the scientific knowledge map (Zhang, 2016). As depicted in Table 3, these keywords can be divided into three categories according to their nature, namely, research on feminist translation theory, research on gender, and research on the works about feminist translation. Many keywords belong to the category of feminist translation theory, which indicates that Chinese feminist translation research is still concentrated on the theory. But breakthroughs were also made in translation practice and criticism. Among them, the keyword “Zhang Ailing” appears more frequently, which shows that relevant scholars paid great attention to Zhang Ailing when conducting empirical research on feminist translation. In addition, the keywords of “gender” and “limitation” also appear frequently. It has brought new insights into Chinese feminist translation research and promoted the development of feminist translation research in China.

3.5. Analysis of time zone view

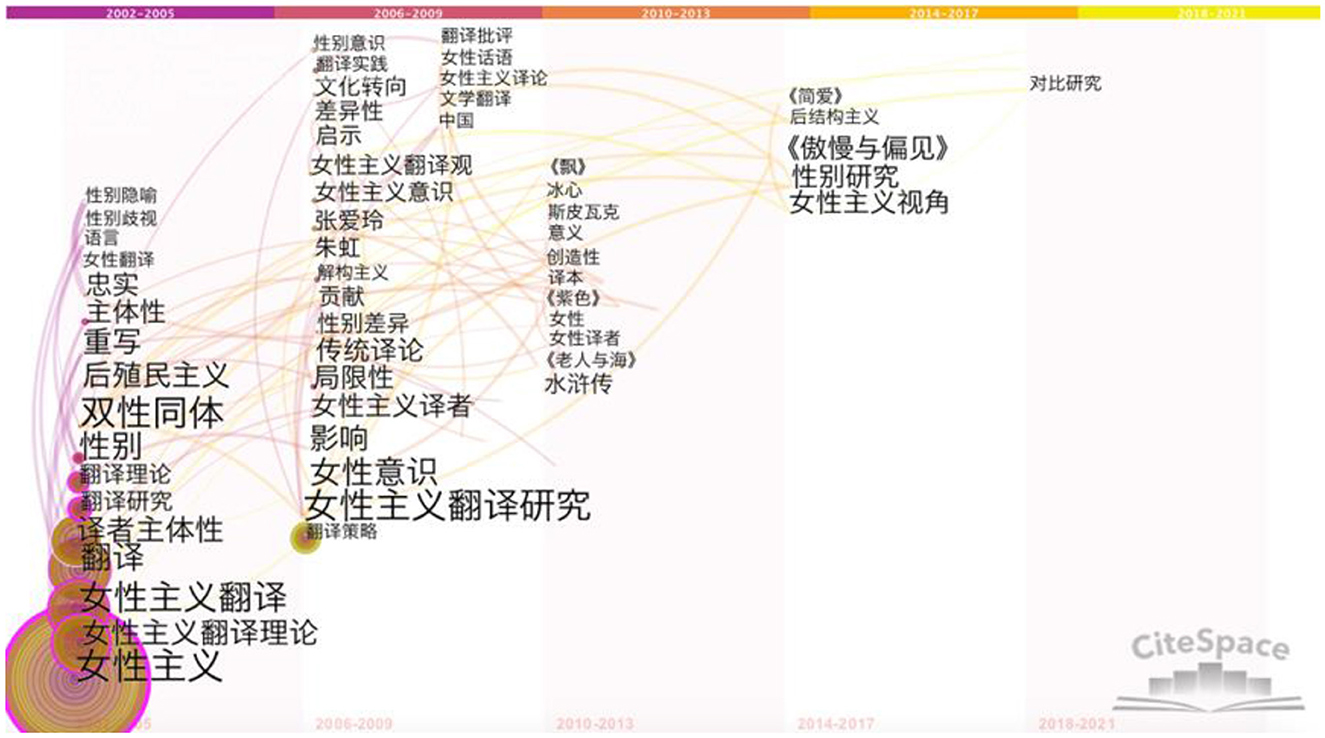

After the research data were imported into CiteSpace with 4 years as a time division, the top 30 keywords in each time division were selected, and then a time zone co-occurrence map of Chinese feminism research was generated. Figure 5 presents more details.

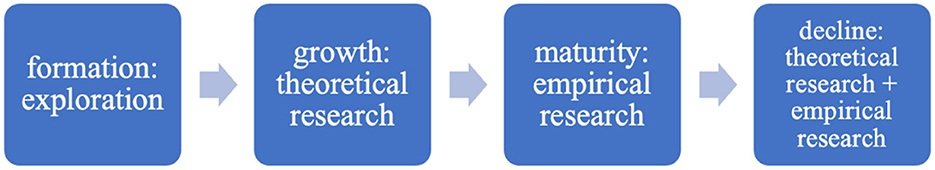

In general, the time zone map depicts the different hot topics of Chinese feminist translation research in different periods, but as time progresses, the nodes in the time zone map gradually become smaller. In addition, the density of hot topics keeps shrinking, and the degree of connection between hotspots is also constantly declining. Given the four stages of the development of feminist translation studies in China in the past 20 years, namely formation (2002), growth (2003–2008), maturity (2009–2013), and decline (2014–2021), the time zone characteristics of the development of Chinese feminist translation research are shown in Figure 6.

During the formation period, researchers in this field were devoted to exploring how to develop feminist translation research in China. Their priority was to have a preliminary understanding of foreign feminism, feminist translation, and related theories, laying a foundation for the further development of feminist translation research in China in the future.

The research hotspots in the growing period mainly concentrated on the theory. Scholars began to introduce feminist translation theory to China from different perspectives. Especially, in 2004, the fourth issue of Chinese Translators Journal launched a research column on “Feminist Translation Studies,” which attracted many scholars to conduct research in this field (Yang L., 2007). For example, Ge (2003) published “The Essence of Feminist Translation,” which expounded on the origin of feminist translation theory from the perspective of cultural criticism and pointed out that feminism's understanding of translation is a macro concern and partial. Liu (2004) also discussed the influence of feminism on translation. Jiang (2004) interpreted the influence of structuralism, postcolonialism, and cultural studies on feminism translation in the article “The Influence of Feminism on Translation Theory.” However, at this time, research is limited to the in-depth interpretation of feminist translation theory, which cannot ensure the long-term prosperity of feminist translation research in China.

In the mature period, researchers in the field of feminist translation in China mainly focused on empirical research. Scholars started to analyze novels from the perspective of feminist translation theory and reveal the translator's feminist consciousness in the translation process, which is of great significance for enriching Chinese feminist translation research. For example, Chen and Chen (2005) discussed translation strategies and methods that highlight female discourse by comparing Mr. Wu Junxie's and Ms. Zhu Qingying's translations of Jane Eyre. Yang X. (2007) explored how feminism influences translators' style by comparing the pronunciation, words, and sentences of three English versions of “The Song of Burial Flowers” (translated by Yang Xianyi and Dai Naidie, Hawkes, and Xu Yuanchong, respectively). Dang (2012) selected the Chinese translations of Pride and Prejudice by Lei Limei and Sun Zhili, respectively, and compared the strategies adopted by the two translators. Dang found that when it comes to literary works, the feminist consciousness of the translator will exert a significant impact on the style of the translation.

During the decline period, the popularity of Chinese feminist translation research dropped sharply, with only a few articles published, and these articles still focused on theoretical analysis and empirical research. No new progress was made, which shows that Chinese feminist translation research has waned.

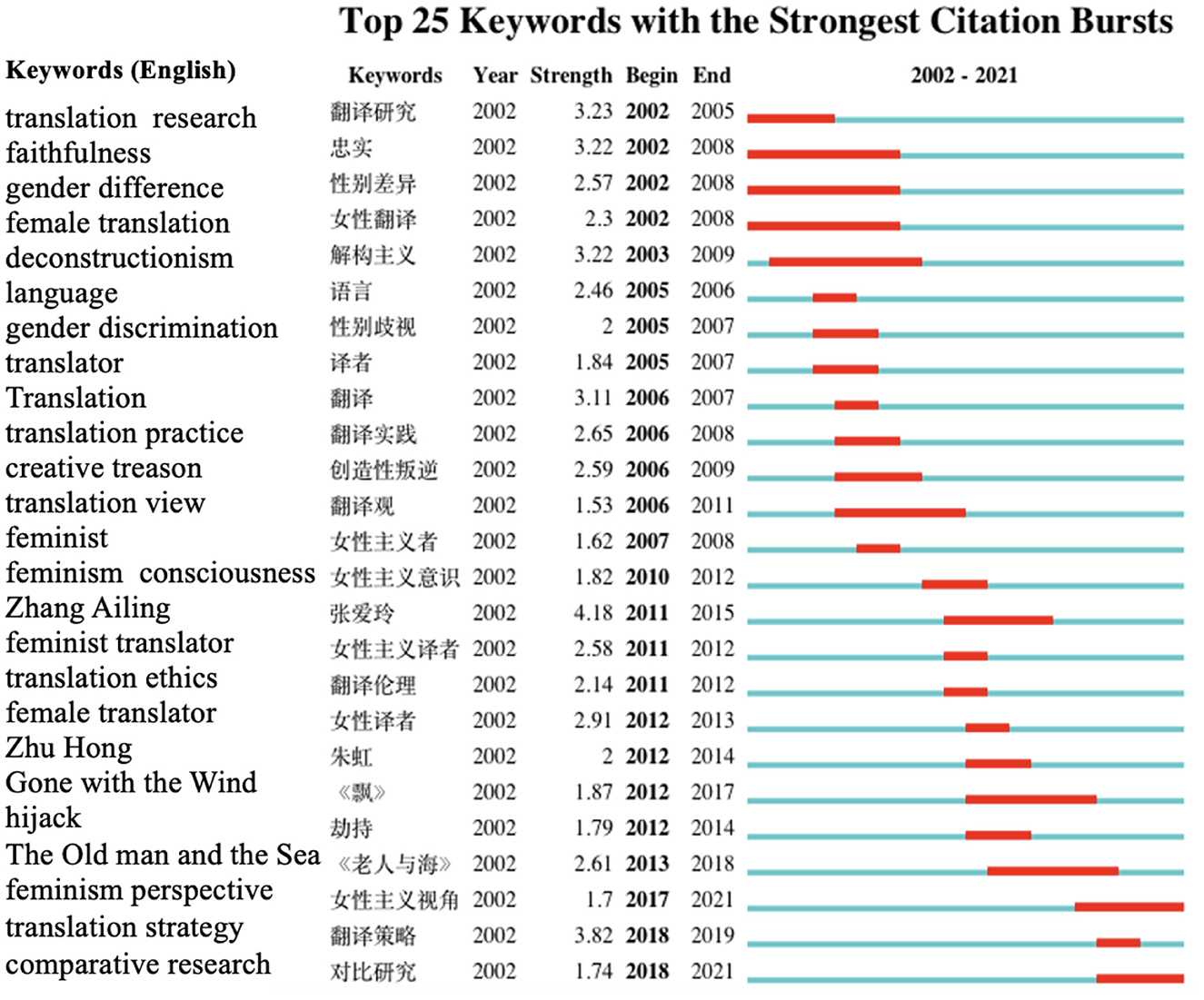

3.6. Analysis of frontier research

The “mutation detection calculation” of CiteSpace can detect the sudden increase in research interest and accurately reflect the latest trends in a certain research field (Li, 2014). The keywords mutation chart of Chinese feminist translation research in the past 20 years is shown in Figure 7. Since CiteSpace's “keywords mutation chart” is arranged from top to bottom according to the mutation start time, the research topics closer to the bottom in Figure 7 are more cutting-edge.

Figure 7 shows that the keywords with the highest mutation intensity in 2002 were “faithfulness,” “gender difference,” “female translation,” and “translation research,” and the keywords with the highest mutation intensity in 2018 were “translation strategy” and “comparative research.” After 2018, the mutation intensity of keywords in the field of feminist translation research is relatively small, which indicates that Chinese feminist translation research has been relatively unpopular in the past 3 years. Judging from the mutation period of each keyword, “faithfulness,” “gender difference,” “female translation,” and “translation research” are the first to mutate. The mutation of “translation research” ended in 2005, and that of “fidelity,” “gender difference,” and “female translation” ended in 2008. Other keywords that began to mutate between 2002 and 2007, such as “deconstructionism,” “language,” and “translation,” also ended their mutation around 2008. Before 2008, the research on feminist translation theory was a hotspot in the Chinese translation field as feminist translation had just been introduced into China. The focus of research in this period was to conduct a thorough and comprehensive analysis and interpretation of feminist translation theory. In 2011, the keywords with the highest mutation intensity were “Zhang Ailing,” “feminist translator,” and “translation theory.” But, the mutation of “feminist translators” ended in 2012, which indicates that the research on female translators in China was short-lived. However, the mutation of “Zhang Ailing” and “The Old Man and the Sea” lasted for 5 and 6 years, respectively, demonstrating that Chinese feminist translation research during this period was dominated by empirical research. As shown in Figure 7, the mutation of the last keyword, “comparative research,” started in 2018 and ended in 2021, showing that feminist translation researchers began to compare feminist translation theory with other theories. The mutation period of “comparative research” is longer, but the mutation intensity is smaller, which means that feminist translation research in China did not grow into a towering tree in recent years.

4. Conclusion

Using the bibliometric tool CiteSpace, this article systematically analyzes the research institutions, researchers, research hotspots, research trends, and research frontiers in Chinese feminist translation research from 2002 to 2021. This article clarifies the research institutions, researchers, hotspots, and frontiers of feminist translation research in China to a certain extent and draws the following conclusions: (1) Feminist translation research in China can be divided into four periods: formation, growth, maturity, and decline; (2) Research institutions such as Sichuan International Studies University, Central South University, and the Civil Aviation University of China have contributed greatly to the development of feminist translation theory in China. Researchers such as Zhang Jianping, Geng Qiang, Lv Xiaofei, and Li Hongyu also made tremendous contributions to this field. The collaboration between Chinese researchers and institutions in this field is not close, which poses a challenge to the sustainable development of feminist translation studies; (3) During the past two decades, the focus of Chinese feminist translation research has changed from theoretical research to empirical studies, and now both are priorities of researchers; (4) In recent years, no great progress has been made in feminist translation research in China.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

FS and HL contributed to the overall design, organization, and logic of the manuscript as well as data analysis and manuscript writing. XW and SW were responsible for data collection and language polishing. All authors contributed to the drafting and proofreading of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Chen, Y., and Chen, L. (2005). Feminist rewriting of the discourse — with a comparative study on the two translation versions of Jane Eyre. J. Shanxi Normal Univ. (Social Science Edition). 6, 126–129. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7F1IFNsBV5UuoBmI0jipJDG9ysALmkM-4JbVLnHnxzAspTY9QkN8mfzmK6OmetMhT&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Dang, Q. (2012). A comparative study of feminist consciousness in the Chinese translation of Pride and Prejudice. J. Shanxi Normal Univ. (Social Science Edition). 39, 111–113. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7fm4X_1ttJAl_I1Kwj8mwkSGDeSCLqS4_r7TQp2kNfF1dT0wQekGGZcYHjHidhuLQ&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Feng, J., Wang, K., and Liu, X. (2014). Emerging trends in translation studies (1993–2012): a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Technol. Enhanc. Foreign Lang. 155, 11–20. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5795.2014.01.002

Ge, X. (2003). The essence of feminist translation. Foreign Lang. Res. 6, 35–38. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7ZCYsl4RS_3itrdH_Kup2rajKz3GMMhLTFwjdIX-Ju-YrGdYFhu6aV-98Vfk7rIYa&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Godard, B. (1990). “Theorizing feminist discourse/translation,” in Translation, History and Culture, eds S. Bassnett and A. Lefevere (London: Pinter), 87–96.

He, C., and Luo, H. (2020). An analysis of the dynamics of domestic corpus translation studies (1993–2020). Chin. Sci. Technol. Transl. J. 33, 17–20. doi: 10.16024/j.cnki.issn1002-0489.2020.04.006

Hu, Z., Hu, X, and Li, E. (2013). Reception of feminist translation theory in China. Academics. 3, 152–160. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7xAZywCwkEEL30uAMF2xhaml-0RqhU2lnPOI7ZAWzevaKXcJyIj8dD5RHdxpXYPaF&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Jiang, X. (2004). Feminism's influence on translation theory. Chin. Transl. J. 4, 12–17. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7eeyE9jLkqq8WozgpwjpPnrG3aoTre4YQmq4WLhJjrFblIge0yVJQ4S-PEbkswhMG&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Li, H. (2014). Visual analysis of hot spots and frontiers of international translation studies. Chin. Transl. J. 35, 21–26. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7M8Tu7YZds89qd5hlDKZXafOMVR8vODzSjDlUK7-pE8p2a_yvJaum_9Byrh4Znx8s&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Liao, Q. (2002). Re-write the myths: feminism and translation studies. Foreign Lang. Lit. 2, 106–109. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7lwLRIsgSA99kA6–UXMkeAPlF55qs39MFQkULmLdvfsaXT1iC_ZCu9Tm–W5zE9p&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Liu, G., and Chang, F. (2018). Analysis of translation studies in domestic corpora based on citespace. J. Henan Normal Univ. (Social Science Edition). 46, 111–120. doi: 10.16366/j.cnki.1000-2367.2018.06.018

Liu, J. (2004). Towards an east-west discourse on feminist translation studies. Chin. Transl. J. 4, 5–11. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7eeyE9jLkqq8WozgpwjpPnrG3aoTre4YQ5l5DTa1AO9SV7oM9WgMN3IbXPoWE8y-p&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Simon, S. (1996). Gender in Translation: Culture and Identity and the Politics of Transmission. London: Routledge.

Wang, X., Sun, F., Wang, Q., and Li, X. (2022). Motivation and affordance: a study of graduate students majoring in translation in China. Front. Educ. 7, 1010889. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1010889

Yang, L. (2007). A study of feminist translation in the chinese context. Foreign Lang. Teach. 6, 60–63. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7aLpFYbsPrqEzN9oiPRIo4yt_Aw3wSPjiQtlQvGqRXDMgrFvOGzHqg29TisdVx1gJ&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Yang, X. (2007). Translators' feminist consciousness and the english translating of Zang Hua Ci. J. Shanghai Univ. (Social Science Edition). 1, 125–130. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7aLpFYbsPrqHiLsuOFV21dCgmY5dL_7h7qMcbn5n8nK98QKjsVxKTsmVMb589wKS&uniplatform=NZKPT&src=copy

Keywords: Chinese feminist translation research, visual analysis, CiteSpace, research hotspots, research trends

Citation: Sun F, Wang X, Li H and Wang S (2023) Visualization analysis of feminist translation research in China (2002–2021) based on CiteSpace. Front. Educ. 8:1015455. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1015455

Received: 09 August 2022; Accepted: 08 February 2023;

Published: 06 March 2023.

Edited by:

Hassan Ahdi, Global Institute for Research Education & Scholarship, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Gang Zhao, East China Normal University, ChinaLuise Von Flotow, University of Ottawa, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Sun, Wang, Li and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongbin Li, eGxpaGJAdGp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Fei Sun

Fei Sun Xiaochen Wang

Xiaochen Wang Hongbin Li

Hongbin Li Siying Wang

Siying Wang