- 1Department of Public Leadership and Social Enterprise, The Open University Business School, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom

- 2Department for Education, Vrije University Brussels, Brussels, Belgium

Trust in leadership is a key element in organizational effectiveness and the foundations of a successful school. However, this element of leadership is underexplored in terms of empirical work, concomitantly, distrusting school cultures have been identified as inhibitors of school improvement. This paper explores trust in leadership through a relationship-based perspective of trust, taking by taking the case of eight primary schools, in South Africa, to examine: Which factors positively influence trust in leadership of primary schools and which undermine it. The paper begins by conceptualizing trust and relational based trust in leadership before moving on to analyze trust in educational settings. It explores trust between leaders and staff and within staff member groups. From there the paper discusses the implications of the findings within the particular cultural context of South Africa. The paper concludes with a summary of factors detracting from and contributing to trust in leadership, and to what extent these align with relational trust in leadership and the construction of effective learning communities. In so doing, the paper raises awareness of the importance of trust in leadership in the context of South African Primary Education and how it can undermine leadership if not established throughout relationships in schools, offering insights for primary leaders working within the African context. It also questions the appropriateness of adopting a relational understanding of trust in distributed leadership in relation to this particular context.

1. Introduction

Over the last four decades, the idea of trust in leadership has gained currency, not only in terms of the literature on leadership itself but also in relation to the literature on followership and how the behavior of followers influences leadership. Studies across the public sector show that trust in leadership is crucially important for leader effectiveness and creativity (Boies et al., 2015), linking to positive job attitudes, organizational justice, and effectiveness (Dirks and Ferrin, 2002; Riley, 2013). However, despite this, comparatively little systematic effort has been made to apply emerging insights and empirical findings to leadership theory (Kramer, 2011). Leadership is a highly contested term, and so too is trust in leadership, as Fine and Holyfield emphasize arguing that trust in leadership is also the cultural concept that elicits, “a world of cultural meanings, emotional responses, and social relations” (Fine and Holyfield, 1996, p. 25). According to Hardin, trust in leadership should be conceptualized in terms of three elements: the properties and attributes of an individual truster; the attributes of a specific trustee (their trustworthiness); and the specific context or domain in which the trusting relationship was carried out (Hardin, 1992, p. 45).

The field of research on trust in leadership is complex with conflicting notions of how leadership can be conceptualized, how it differs from management, and to what extent it can be seen to be distributed, or evidenced at various levels within a school. Aligned with this, examining trust in leadership largely depends on the way that the writer conceptualizes leadership (Storey et al., 2016). The literature also reveals the primacy of context in exploring notions of trust. This is largely due to the way that trust is understood in different societies. For example, in the global north, we speak about corruption to encompass nepotism of all genres. But in many cultures, nepotistic practices are viewed as normal, or even key to ensuring that systems function effectively (see an extensive discussion on this in, Baxter, 2020). For these reasons and to focus on our literature review, we identify two key strands of literature that have emerged over the last 20 years, in relation to trust in leadership in the African context: the first, the character-based perspective, is premised on the idea that trust in leadership is based on perceptions of the leaders’ character and trustworthiness, by followers; and the second, the relational perspective, is conceptualized by Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer (2021) as consisting of five interconnected dimensions of trust, interpersonal, international, intersubjective, intellectual, and pragmatic. The character-based perspective is largely focused on the particular traits of the leader, and how they as an individual affect subordinates. Up to 2016, this concept of leadership was popular in post-apartheid South Africa. But latterly, due to a failure to improve educational outcomes, relational, distributed models of leadership are now argued to be more prevalent (Bush and Glover, 2016). The relational perspective has also been used effectively to understand how trust in leadership relates to organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): an individual’s commitment to an organization that contributes substantially to the creation of positive and affirming organizational identities, and a key element within well-functioning schools and organizations (Gregory, 2017).

Trust in school leadership has been an important area for research over the last 30 years, and is linked to a number of positive outcomes, including increased social capital in schools—teachers and pupils working together to maximize outcomes (Riley, 2013). In areas of high socio-economic deprivation, it is particularly important to achieve a functioning relationship between schools, parents, and communities—a factor that increases the democratic potential of education (Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer, 2021). Since then, it has been featured within several strands of research, including, for example, professional learning teacher effectiveness, organizational learning school capacity for change (Baxter and Cornforth, 2019), and teacher commitment to change (Niedlich et al., 2021). This research addresses a gap in empirical work, specifically linking relational trust in primary leadership, with successful learning outcomes, in the African context.

We begin the article with a discussion of the context in which it is set so that the reader can understand the unique nature of the South African context. We then move to conceptualizing leadership, trust, and finally, trust in education and school settings. The next section provides an overview of our methods and sample. In section three, we provide our findings according to the themes that arose during our extensive coding book development before moving on to the conclusions for this article (section “4. Conclusion”).

1.1. Context

Trust in school leadership does not take place in isolation, the political, social, and economic environments in which education systems are situated, are highly influential. South Africa’s education system is one of the most unequal in the world. Only the top 16% of South African grade three children are performing at the appropriate grade level, while the learning gap between the poorest 60% and the wealthiest 20% of students grows from grades 3 to 4 by the time they reach grade 9 (Spaull, 2013). Spaull (2013) talks about a dualist distribution of student performance with two differently functioning sub-systems. The lowest performing schools serve the majority of mainly black and colored students. Higher achieving schools are often those that historically served white children and produce educational achievement closer to the norms of other developed countries. There is a particular issue in relation to primary education, as other research has highlighted (Fleisch, 2008). For example, Fleisch (2008) discusses the lack of performance in reading and mathematics by the end of primary education, while Taylor et al. (2019) highlight the huge achievement gap that persists by stating that, “less than half of learners attending former Colored primary schools can read at grade level and only four children in a hundred in former DET (Department of Education and Training) schools are reading at the prescribed level.” (Taylor et al., 2019, p. 2). As this gap persists throughout the trajectory of learners, leading to a lack of skills in the workplace, as well as a detrimental influence on the social fabric of this society (Spaull and Pretorius, 2019), this article focuses on primary education. It is important to highlight that this situation is not unique to South Africa, as many reports indicate, for example, an OECD report on Equity and Quality in Education (2012) highlights, “reducing school failure strengthens individuals’ and societies’ capacities to respond to recession and contribute to economic growth and social wellbeing. This means that investing in high quality schooling and equal opportunities for all from the early years to at least the end of the upper secondary is the most profitable educational policy.”(OECD, 2012, p. 3). As there are several countries with considerable achievement gaps by the end of primary education, this research is significant for these countries too. In addition, despite possessing an abundance of natural resources and its recognition as one of the largest industrialized countries in Africa in both wealth and GDP, its high unemployment, inequality, and poverty rates lead to its classification as a developing country (Bakari, 2017).

The South African post-1994 education dispensation aimed to homogenize the education system by introducing reforms to improve learning outcomes across the country, such as a national curriculum for all schools and redistribution of resources in favor of schools in disadvantaged areas. To date, these policies have not had the desired effect, as inequalities remain high and the gap between rich and poor students is ever wider (Spaull and Taylor, 2014).

Lack of trust in leadership is a leitmotif throughout the literature as a barrier to substantive change in South Africa, and the continuing achievement gaps between poor and affluent students: for example, Heystek (2006) discusses the lack of trust between principals, teachers, governing bodies (SGBs), and the district, hampered by wider socio-economic problems; notably “the impact of HIV/AIDS, parental breakdown, poverty and disrespect of teachers; all factors that undermine trust in schools. There too, has been some discussion around exactly who leads, for example, many school principals have been incapable of leading due to lack of training, or lack of acceptance of their role, by the school community” (see Volmink et al., 2016 for more details). This lack of support, in some cases, has led to principals quitting, or leadership being taken on by school staff that does have the support of the community. Lack of trust has also been found, in some cases, to be due to the actions of strong teacher unions, which have historically resisted accountability-based reforms, such as inspection systems (Spaull and Taylor, 2014).

This article is part of a wider funded project examining the relationship among trust, accountability, and capacity to improve learning outcomes in South African primary education. The article looks to extend the existing research on trust in school leadership by taking the case of eight primary schools, four high-performing (HP) schools, and four low-performing (LP) schools to examine which factors positively influence trust in the leadership of primary schools in South Africa and which undermine it. It then continues by examining what the results of this small-scale article may mean for primary leadership internationally.

The article builds on extant literature on leadership and trust. We begin by highlighting our concept of leadership, before moving on to conceptualizing relational trust in relation to the trust literature. The article then continues with an explanation of our sample, methods, and findings. Finally, the implications of the findings and the limitations of the article are discussed.

1.2. Conceptualizing leadership

Leadership and trust have been successfully investigated by adopting a distributed view of leadership (Ring, 1996; Putnam et al., 2004; Mehdad and Iranpour, 2014; Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer, 2021), rather than adopting one of the myriad other concepts of the term (Grint, 2010). This is largely due to the recognition that to create a successful organization, trust needs to occur at all levels of leadership (Edwards-Groves et al., 2016; Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer, 2021). For example, there is no merit in staff trusting the head teacher of a school, if their trust and faith in the head of the department are absent (Branson et al., 2016).

Theories of distributed leadership in schools, prevalent since 2000, propose that rather than being a top-down activity, restricted to school senior leadership teams, leadership is distributed throughout the organization (Harris, 2003). Since then Harris, a key proponent of the concept (2016), has argued that the distributed view of leadership is not unproblematic. Harris indicates that it underestimates the ways that power operates in an organization and highlights the toxic effects of destructive leadership at all levels, arguing that distributed leadership can only thrive if it is set up and supported appropriately (Leithwood et al., 2007). This concept of leadership positions is an interactive process in which influence and agency are widely shared. Trust is key to the success of distributed leadership models, creating organizational cohesion and contributing to effective, mentally healthy workplaces (Braynion, 2004). In research that examines trust in distributed leadership, the relational concept of trust is most prevalent in the literature (Dietz and Den Hartog, 2006; Welter, 2012; Demirdoven et al., 2020). We discuss the reasons in our next section.

1.3. Conceptualizing trust

A large body of work aims to understand trust in (dyadic) interpersonal and intra-organizational relations, looking at economic transactions between buyer and supplier, or interactions between employer–employe, or regulator–regulatee. A common definition of trust across these studies is “a trustor’s willingness to take risk based on assessments of a trustee’s competence, benevolence and integrity” (Addison, 2015, p. 156) These three dimensions are further described by Oomsels and Bouckaert (2014, 2017):

• Competence: perceived ability or expectation that the other party has the competence to successfully complete its task.

• Benevolence: expectation that the other party cares about the trustor’s interests and needs.

• Integrity: expectation that the other party will act in a just and fair way [Oomsels and Bouckaert, 2017, p. 82–88 in Ehren et al. (2018)].

Six and Verhoest (2017) describe how a “trustor” will have an initial perception of someone else’s trustworthiness which will inform his/her decision to be vulnerable to the actions of that other person. Such initial perceptions are partly informed by “hearsay” and judgments of others, personal histories (“shadow of the past”), and tend to be more favorable toward members of one (sociocultural, organizational, and role) group (Kramer, 1999), and where there is an expectation of continued interaction (“shadow of the future”) (Poppo et al., 2008). Lewicki and Brinsfield (Lewicki and Brinsfield, 2015, p. 59), Lyon et al. (2015), and Le Gall and Langley (2015) emphasize that trust is not a single, unidimensional construct, but rather constitutes different.

-forms of trust (e.g., competence-based, motive-based, calculated, moralistic, and identity-based),

-antecedents of trust (elements fostering the creation of the trust; and institutional versus relational),

-elements (or modalities) enhancing trust (institutional versus relational), explaining how trust develops over time (the dynamics of trust), and how it is context-dependent and manifests itself at the individual, group, organizational, and societal levels.

Studies vary in conceptualizing trust as either a rational and calculated process or as the result of less explicit, routinized, intuitive, and habitual actions (Lyon et al., 2015, p. 8; Le Gall and Langley, 2015, p. 38). The first strand understands trust from an economic or sociological perspective, looking at behavior and purposeful decisions and choices available in a given context of alternatives. The second, psychological and psychosocial approach, considers trust to be the result of less explicit, routinized, intuitive, and habitual actions where trust constitutes a set of beliefs, emotions, intentions, and expectations (Ehren et al., 2018).

According to Lewicki and Brinsfield (2015, p. 46), trust can be positive or negative where research evidence indicates that trust and distrust are two different constructs (Lewicki and Brinsfield, 2015, p. 46): individuals in a relationship can hold both trusting and distrusting intentions and expectations toward another, based on different facets of their relationship. Next, we move to describe trust in education and school settings and the concept of relational trust.

1.4. Trust in education and school settings

1.4.1. Caveat

There is a wide body of literature that explores trust in relation to education [see the comprehensive literature review by Niedlich et al. (2021)]. As various authors highlight, it is key to understanding several factors within both schools and systems. As this particular study focuses on leadership, we have limited our literature review within this article, to conceptions that are particularly relevant to trust in leadership. For a wider and more comprehensive discussion of trust in education, see Ehren et al. (2018). In what follows, we offer a brief overview of trust in education internationally.

Studies on trust in education and school settings have conceptualized trust in many ways: as everyday relations between teachers, between a principal and teachers, between a school and the school’s community (e.g., parents), or as a structural characteristic of schools (Kochanek and Clifford, 2014). Bryk and Schneider (2003), for example, look at the specific roles people hold in schools and how trust grows as people share their understanding of role obligations, have basic regard for the dignity and work of others (respect), possess the competencies to carry out formal responsibilities of their role, act in ways consistent with beliefs about what is in the best interest of children (integrity), displaying intentions and behaviors that go beyond the formal requirements of the role (personal regard). They find that trustful relations among students, teachers, parents, and the wider school community are closely related to student outcomes (Bryk and Schneider, 2003).

Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (1998) on the other hand describe trust as a structural characteristic of schools, defining trust as an aspect of a school’s climate, or the social capital in the school. The two bodies of work are strongly related as “social capital (a structural feature of a school) emerges from ties between individuals and organizations, and the social relationships within an organization and surrounding the individuals of an organization,” (Ehren et al., 2018, p. 48). Through these ties, a shared understanding of norms and values is created, knowledge is shared, and habits are created which would inform the school’s culture and structure. This form of trusting relations has been termed relational trust. Often described as, “the glue that binds a professional learning community” (Cranston, 2011, p. 59). A professional learning community develops the types of relationships among staff, pupils, and parents, that support school improvement (Spillane and Louis, 2002). Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer (2021) highlight the complexity and delicacy of researching relational trust in schools. Their article argues that “research examining what constitutes the multi-facetedness of relational trust is under-theorized” (p. 262). Citing the work of Robbins (2016), they highlight that there is a need for social scientists to seek out “more nuanced empirical workings of the genesis” (Robbins, 2016). Their work specifically investigates relational trust in the case of middle managers and argues that there are five elements of relational trust, and these appear in Box 1 as follows.

Their work into trust and middle leadership advocate a practice-based approach to the phenomenon, analyzing the minutiae of relationships within the school context and revealing that principals’ “professional knowledge, expertise, and determination to nurture their teaching staffs as professional learning communities will fall flat if relational trust among faculty is absent.” (p. 70).

They too agree that context is a fundamental consideration within this, as historical and cultural factors influence power and agency within schools and the extent to which staff and leaders perceive their relative powers. However, this is not explicitly explored in their article.

Relational trust is often cited within the context of organizational citizenship research. Konovsky and Pugh tested a social exchange model of organizational citizenship behavior after which they concluded that 1. Procedural justice is central to the development of employee’ trust in their supervisors and 2. A trusted supervisor mediates the relationship between justice and organizational citizenship. They also found that this relationship becomes a metonymy of the employee’s relationship with the organization, coloring their perceptions of the organization as a whole (1994, p. 44). They argue that if the relationship is good then this mirrors the relationship of the employee with the organization as a whole. Organ’s (1988) research links to this in arguing that leaders’ perceived fairness leads to employee citizenship behaviors, such as returning favors or supporting colleagues, because there is a social exchange relationship that develops between employees and their leaders/managers: When leaders treat employees fairly, social exchange and the norm of reciprocity dictates that employees reciprocate.

Bryk and Schneider (2003) identified three trust behaviors in schools that led to productivity: organic, contractual, and relational. Organic is the friendships and professional relationships that spring up organically within a school; contractual is the individuals’ legal obligations within their role; and relational, which describes the extent to which there is consonance with respect to each group’s understanding of its and the other group’s expectations and obligations (Bryk and Schneider, 2003).

Konovsky and Pugh (1994) list a set of certain motives that characterize and provide the basis for relational contracts; they term these “macro motives”—sets of attributions that characterize people’s feelings and beliefs about the people with whom they will make the exchange, for example, teachers’ belief that the Head Teacher or parents are trustworthy (Goddard et al., 2001). Procedural fairness is important because it colors an employee’s commitment to the system. Because fair procedures demonstrate an organizations’ respect or a leader’s respect for the rights and dignity of individual employees (Goddard et al., 2001). Distributive justice, or the fairness of decision outcomes, is typically used as a metric for judging the fairness of transactions and encouraging employees to behave in ways that are not strictly mandated by employers (Rousseau and McLean Parks, 1993). Therefore, trust will “predict organizational citizenship behavior and mediate the relationship between procedural justice and citizenship behavior.” (Konovsky and Pugh, 1994. P. 659). Robinson’s work on trust and the psychological contract and psychological contract breach (Robinson, 1996) has been highly influential in the field of organizational and leadership work, as it focuses on the psychological contract as “an individual’s beliefs about the terms and conditions of a reciprocal exchange agreement between that person and another party” [Rousseau, 1989, in Robinson (1996), p. 575].

Practice-based approaches have moved the “gaze of leadership toward inquiry focused on the site-ontological practices of leading, which have placed relational trust as a central condition for understanding leading professional learning and change in schools” (Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer, 2021, p. 262). Thus, in relation to this article, we conceptualize trust in leadership as a relational process and trustworthiness based on expectations of leadership, combined with the processes that distributed leaders put in place, which encourage trust. In so doing, we are mindful that we are excluding a broad and influential swathe of literature that favors character-based perspectives. Where indications of this perspective emerge, we will consider whether follow-on research needs to consider this aspect, in relation to the phenomenon under scrutiny.

The findings of our literature review led us to consider that the particular context of South Africa was important to our article in relation to its history of apartheid and the effects that this has had on teaching and education more broadly. Next, we move on to describe our method and sample.

2. Materials and methods

The research was preceded by an extensive literature review (Ehren et al., 2018) which examines conceptualizations of trust. From this, we adopted a case paper approach within two provinces in South Africa. In so doing, we adopt the definition proposed by VanWynsberghe and Khan (2007, p. 80) that a case is: “A trans paradigmatic and transdisciplinary heuristic that involves the careful delineation of the phenomena for which evidence is being collected” [VanWynsberghe and Khan (2007), p. 80]. An extensive case paper report on each school was compiled using data from the documentary analysis and interview data (Ehren et al., 2020).

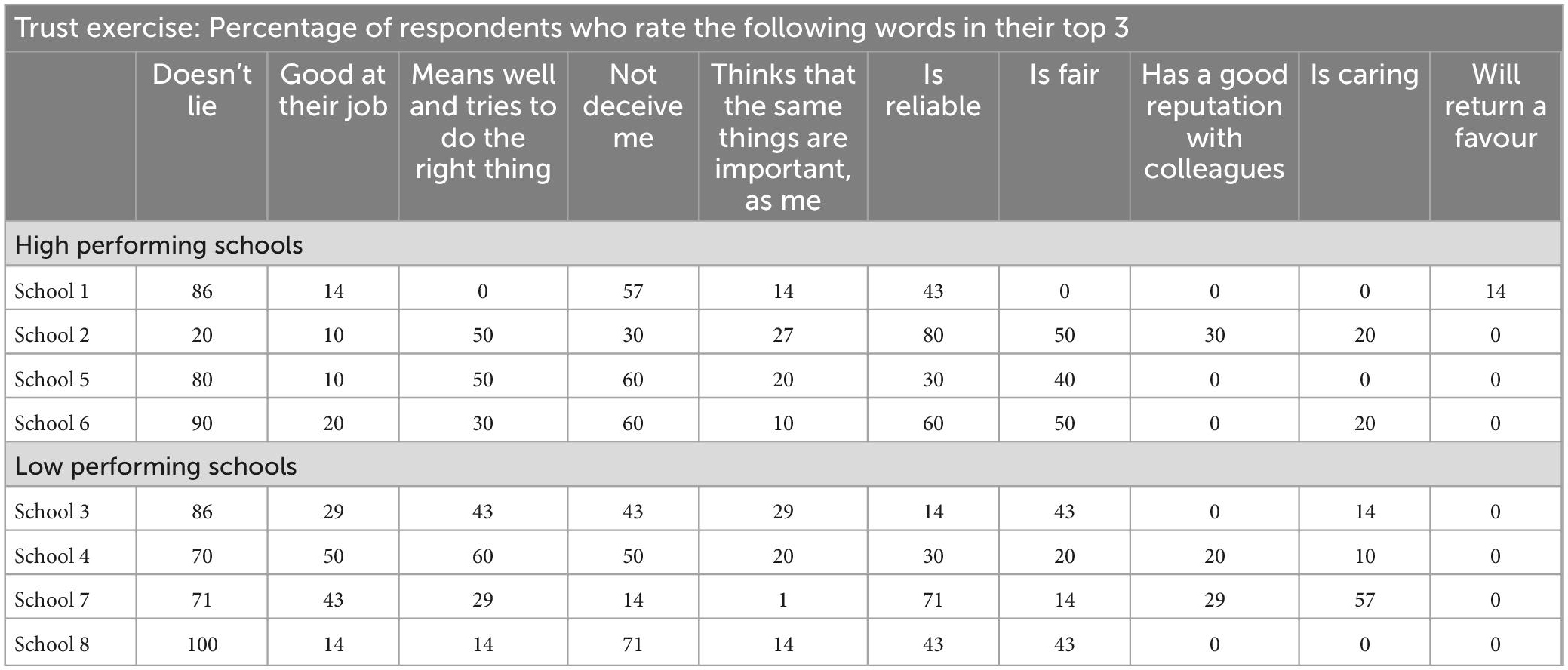

Our schools include respondents from differing cultural backgrounds. So, in line with Mayer et al.’s (1995) guidelines on examining trust in cross-cultural settings, we first administered a trust exercise in the four LP and four HP schools from Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces in South Africa. This was to gauge whether there were any cultural differences in the way in which the term is understood. The exercise revealed no differences in understanding of the word trust, in HP and LP schools (see Ehren et al., 2019 for further details). The grid showing results is located in Appendix 1. It was not within the scope of the study to examine differences between particular cultures, as this would have required a far larger sample. There are 11 officially recognized languages in South Africa along with a range of Khoisan languages. Therefore, our concern within this study was to examine whether trust is understood in the same way by the different cultures interviewed within it. We appreciate that this is a caveat of the study and point to it as an area for further research in our conclusions.

2.1. Sample of schools and respondents

We selected four high- and four low-performing schools from national datasets which included the following:

– the 2014 South African Annual National Assessments (ANAs) (DBESA, 2013),

– the 2014 Schools by Settlement Type,

– the 2017 South African Annual Snap Survey for Ordinary Schools (DBE, 2017), and

– the 2017 South African Schools Master list (DBE, 2017).

These datasets were tidied by removing any inconsistencies, standardizing common variables across the datasets, and merging the datasets into one set. Although the article is too small to draw any conclusions in relation to trust and learning outcomes, we felt that it would be an interesting exercise to see if there were any marked differences between the two types of schools as proved by the learning outcomes revealed in the four different datasets. We were advised to use these datasets as they form the backbone of school performance evaluation in South African basic education (see for details)1. The two provinces were selected in relation to their relative economic prosperity: Gauteng is the single largest contributor to South African GDP, yet has many poor-performing schools (de Clercq, 2014). KwaZulu-Natal is one of the largest provinces and has had considerable investment in a national initiative to improve schools—the NECT or National Education Collaboration Trust2 —in response to low attainment among learners in primary and secondary schools in the province (Grant and Hallman, 2008; Mthiyane et al., 2014).

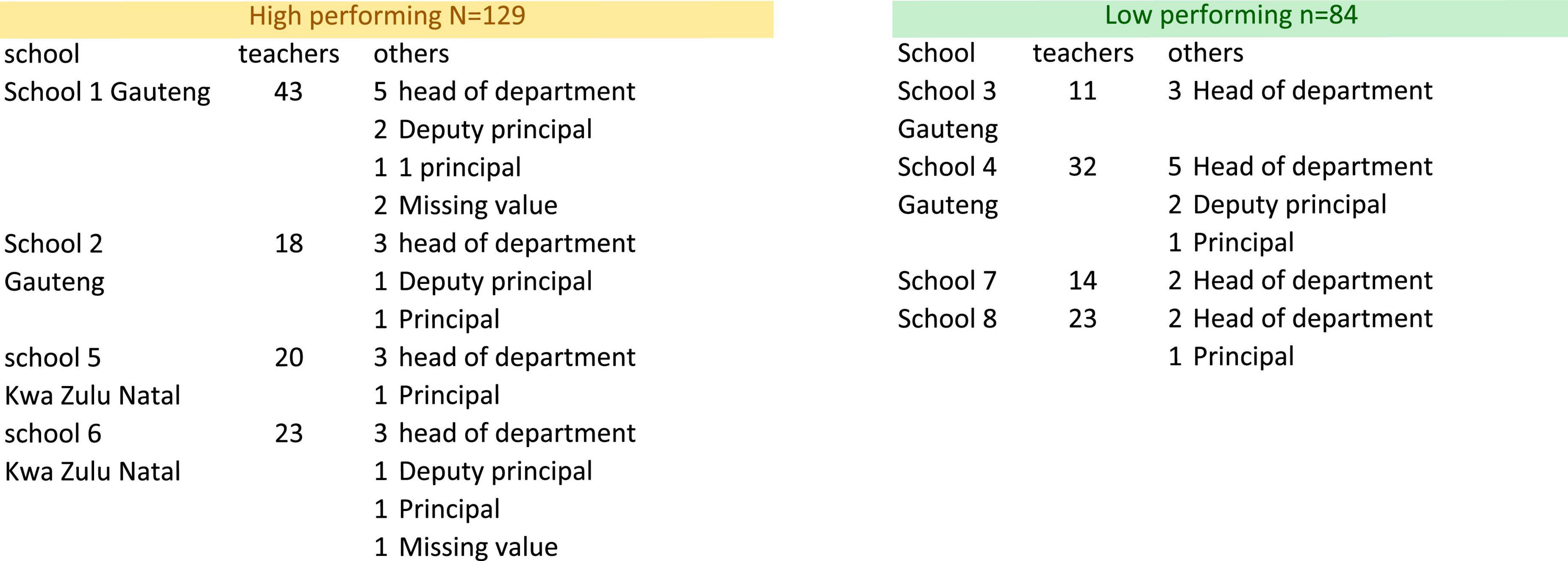

Figure 1 and Table 1 shows that eight schools participated in the article, four in the category LP and four in the category HP. The total number of respondents from the LP schools (N = 84) was smaller compared to the number of respondents (0 = 129) from the HP schools.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with teachers, heads of department, principals, assistant principals, and district officials-Circuit Managers, with oversight of many schools. Interviews were carried out by South African bilingual researchers from Jet Education Services Ltd., a school support and improvement agency based in Johannesburg: The agency has been trusted by SA educators since its early association with former President, Nelson Mandela, and recruiting interviewers within the country forms a key part of our capacity building mission. The research team created a code book from initial transcripts from the pilot project. These codes were then used to analyze the transcripts. The data were then used to write up case studies for each of the schools within the samples. The case studies also drew on additional data from the school, as listed in Appendix 2. Ethical approval was gained within both investigating universities.

A pilot project was carried out and evaluated to refine questions and ascertain which data would be needed to write up a case paper from each school (Ehren et al., 2020).

The data were analyzed as follows: the research team trial-coded one school each to ascertain codes; these codes were then used to create a codebook and the rest of the transcripts were coded. The data were then used to write up detailed case studies for the eight schools and were further analyzed according to the research questions.

2.2. Terms

Throughout the article, the term Senior leadership team (SLT) is used to refer to principals and deputy principals, where it is used to include governors which are highlighted in the text. Middle leaders or Heads of Department are referred to as HoDs.

3. Findings

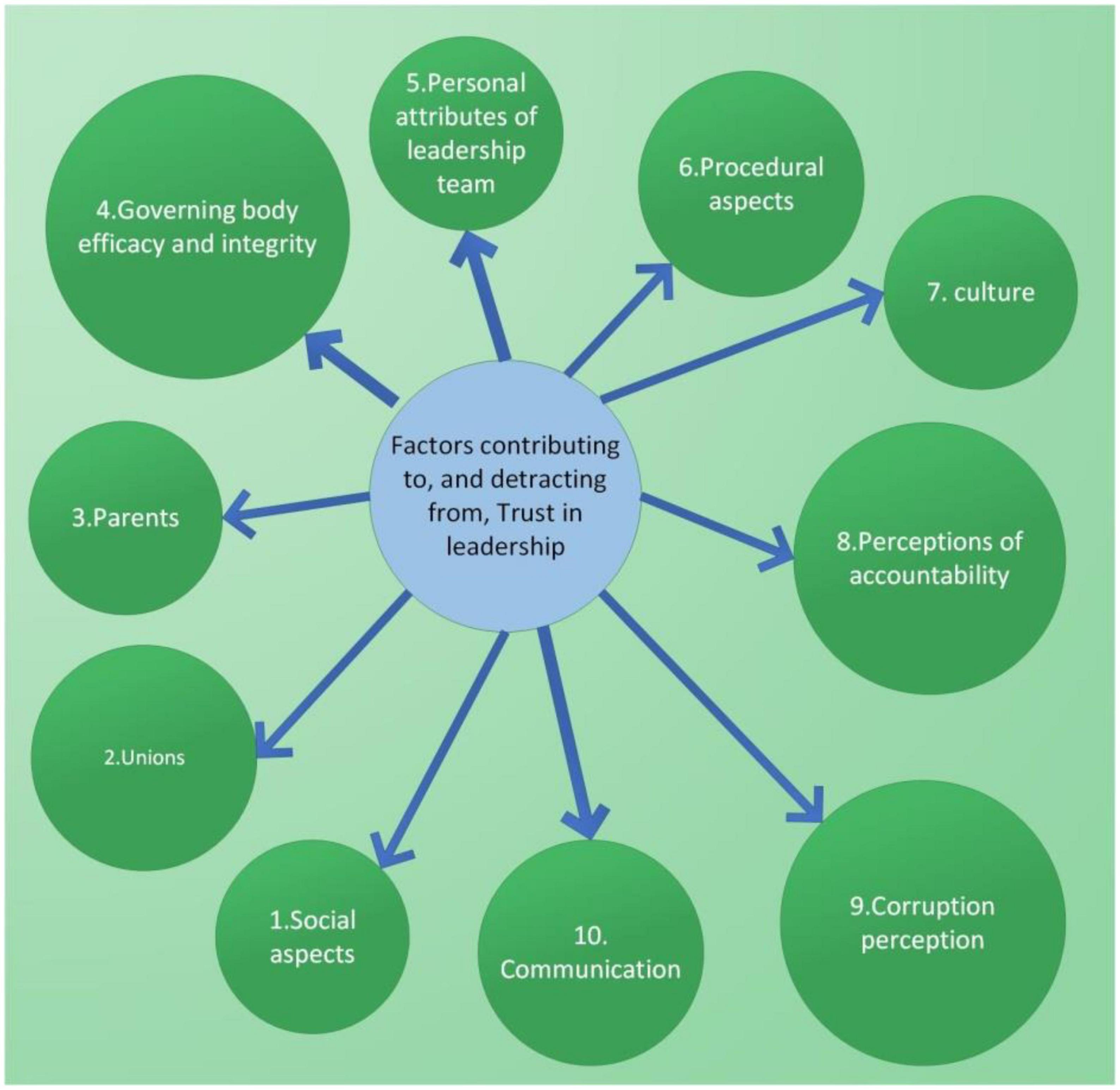

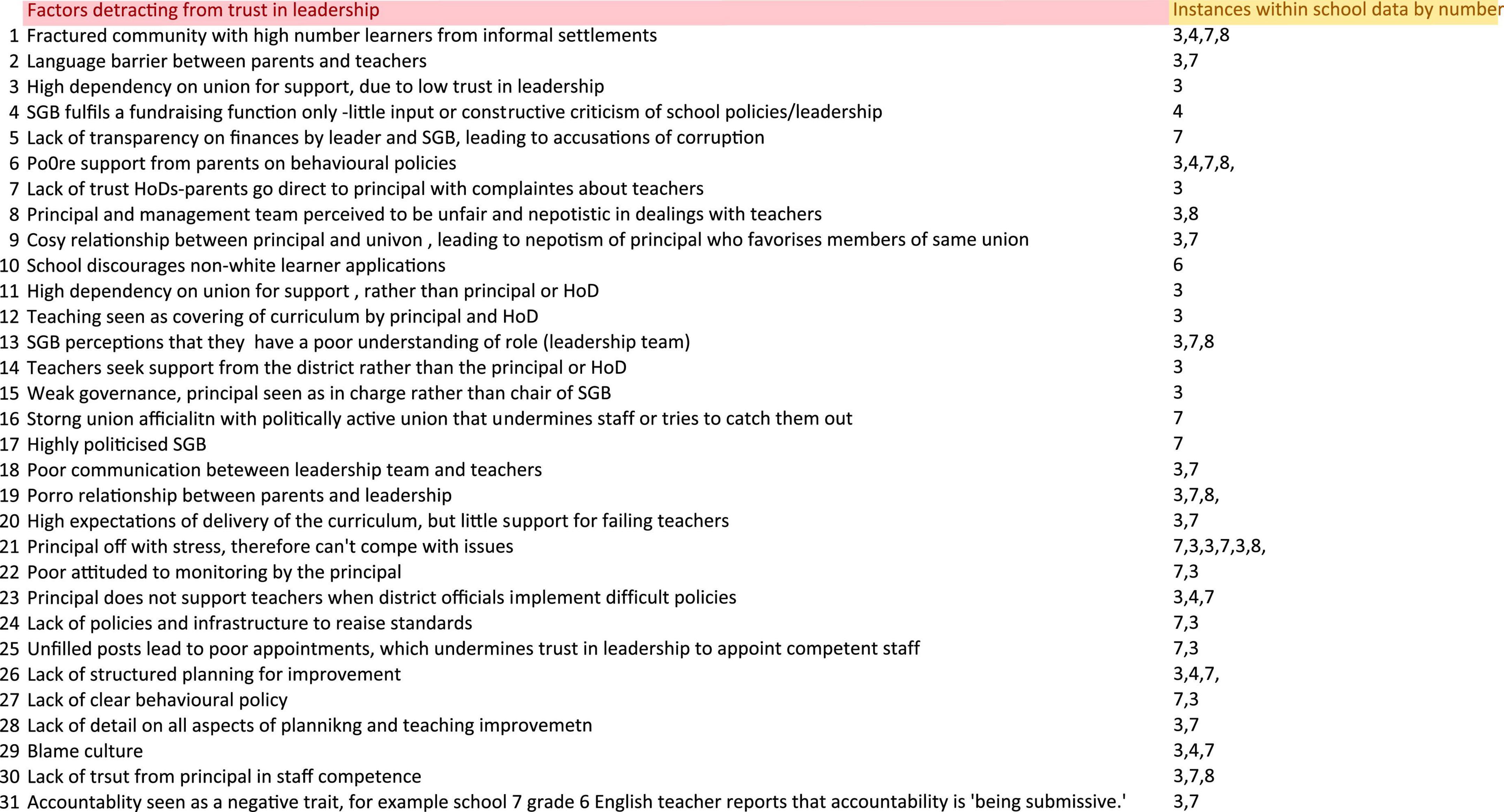

Findings were categorized according to 10 broad themes in Figure 2, which emerged from the literature review, from the five dimensions of trust identified by Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer (2021), and from an initial coded sample of six transcripts. This was used within the code book. The data were then analyzed according to factors contributing to trust in leadership and factors detracting from trust in leadership, in both HP and LP schools. Figure 2 illustrates the areas that emerged in relation to trust in leadership. A table of citations was constructed to illustrate the comments made under each heading (Figure 4).

3.1. Factors detracting from and contributing to trust in leadership

There were 31 key factors that appeared to detract from trust in leadership, which we categorized according to the 10 broad themes as shown in Figure 2, and these can be described as follows:

1. Social aspects: factors out of the control of the leadership, such as high levels of socioeconomic deprivation.

2. Unions: factors relating to union influence.

3. Parents: poor relationship of leadership, with parents.

4. Perceived abuses of governing body power, or inadequacies relating to perceived ineffectiveness.

5. Personal attributes of the leadership team: contributing to the leadership team as a whole seen to be weak or ineffective.

6. Procedural aspects: poor or lack of adequate procedures, for example, support for weak teachers.

7. Blame culture or powerlessness of staff to influence positive learner outcomes.

8. Perceived lack of accountability within the school.

9. Corruption perception: perceptions of corruption or malpractice within the school.

10. Communication: factors relating to the perceived communication within the school.

In the following discussion, we examine each theme in relation to the type of school and the category of respondent. We adopt the acronyms LP = low performing schools and HP = high performing schools.

3.2. Comparison by theme

3.2.1. Social aspects

Low performing schools cited far more examples of how social aspects contributed to a lack of trust in leadership. For example, all schools with poor learning outcomes talked about a fractured community with high numbers of pupils from informal settlements. This, they felt, detracted from trust in leadership because parents within informal settlements were often distrustful of education (having suffered from poor experiences themselves), as this circuit manager highlights:

Communities wanting to impose their own views, disregarding the procedures that must be followed(….) we have a school where, learners burnt the school down because of the issues of not teaching, things that could have been resolved.(..)they choose to burn the school down, and then, they don’t have a school….(District official school 6,3,4).

Another element that appeared as a leitmotif in HP schools was the homogeneity in the background between staff and principal or senior team. If staff and communities did not share the same cultural background as the principal, this was perceived as a negative element among those staff, but for those that did share this background, perceptual trust was strong. Several teachers remarked on the, “in groups” and “out groups,” caused by this, leading to factionalization, as this teacher reported, “It is ok if you are one (of them), but if you are not (from the same background), you are not in” (Teacher, LP school).

Another key element for the lack of trust between parents and school leadership was cited as being a language barrier. Some of the leadership teams spoke English or Afrikaans while their staff spoke another of South Africa’s languages, for example, Xhosa or Zulu. This appeared across schools regardless of their performance. It also appeared as a trust issue among communities and schools, as in the case of, for example, Xhosa-speaking parents and English-speaking staff. This manifested in some extreme examples: a grade 3 teacher (11 years) refers to a conflict in 2014 where the principal was “chased away” by staff and parents, stating, “tomorrow it may be me,” due to the fundamental levels of distrust between parents and the school as a whole, largely due to language and cultural issues. As the principal is often seen to set the tone for the relationship between parents and communities, this had a domino effect, pitting the school against the community. This domino effect, manifesting in a downward spiral of trust, has been highlighted in other research on trust (see, for example, Oomsels and Bouckaert, 2014). One teacher from an HP school indicated that the rejection of non-white learners was a cause of a lack of trust in leadership by the community, but only by non-white members of the community. In relation to white community members, respondents indicated this was seen to increase trust in leadership, again creating the sociological “in group, out group” phenomenon (Riek et al., 2006). This type of discrimination has been addressed in other cultures, for example, Japan, in relation to the Burakumin and the introduction of DOWA education. DOWA education implies a set of educational strategies for democratizing the whole society to attain true equality of opportunity for Burakumin and other oppressed populations. The objectives include (1) attaining parity in the level of educational achievement and rate of enrollment in secondary and higher education levels; (2) developing critical thinking and sound learning capacities for Buraku children; and (3) promoting community involvement in setting-up school agenda (Saito, 2003). For these issues to be addressed, they need to be recognized by all within the school. The covert discrimination described in our article would render this very difficult.

3.2.2. Unions: Factors relating to union influence

Many respondents spoke about unions, which, as our description of context describes earlier, have been the cause of some challenges in schools, with teachers identifying with a particular union, to such an extent that if that union calls a meeting during school time, teachers have been known to leave the school halfway through the school day (Volmink et al., 2016). Interestingly, in two LP schools, union influence was seen in a very positive light by teachers, largely because the leadership was so distrusted. In one school, the Principal and management team were perceived to be so unfair and nepotistic in dealings with teachers, that the union was seen to be vital in protecting them from what they saw as nepotism, one teacher remarking that they “show some favoritism to their friends, they are lenient to some, to others they are not.” (teacher school 3). However, another teacher argued that this favoritism was based on membership in the same union, with teachers talking about the “cozy” relationship between the head and members of the union (teacher 3), and that this was a cause of nepotism by the leadership. In one poor performing school, where there are two unions, one was seen as a negative force, undermining trust, and looking to police staff or “catch them out” as one teacher in school 7 explained: “They will come in [to the classroom] to see what you are doing, and report back to the district….you must keep up. [with the curriculum], or else.” (Teacher, school 7, LP). Classroom visits, by middle and senior leadership, were seen as a negative element of school life in two out of the three underperforming schools, as this teacher reports, “[you]just got that feeling like, that you were being checked up on. Here there is a just, you know you can just do the job because they trust you to do the job you know. Ja” (Teacher school 7, LP). This will be discussed under section 6 of the findings.

In some schools, however, union membership was seen as less important. For example, a recurrent perception in school 1 was that if you were driven by moral purpose (teaching and learning), then the union business was largely unimportant. This discourse appears to be driven from the top, with one teacher explaining that the principal wanted teachers to “just work,” rather than being part of a union. This juxtaposition of work as a moral purpose and union membership as a detractor from this is an interesting one in relation to trust in leadership, reflecting the importance of leadership in establishing the school culture. Teacher unions appeared to be key in offering development opportunities for teachers. These events seemed to build a positive climate of trust between teachers and unions, as this teacher in school 2 (HP) reports: “I love the SAOU, they have workshops and they really do want to improve the quality of Education really they do. Every day I look on my phone I’ve got emails from them, telling me about this and giving me information about that so it’s really nice.” (Teacher, school 2). This was often compared favorably with the education offered by the district managers, as this teacher explains: “The district is some when the district does something they have to because it’s their work, but There we go and there like 30 min late and they are an organized. It’s not always learning we don’t always learn; you understand, they are reading a slide to us and it’s not contributing actually to our education to our teaching ability, but the SAOUG they really put effort into helping us improve, with the district not always some of them is amazing, but it’s, it’s the person that is presenting the class for example that’s the difference, sometimes it’s just for them to do it, But for others it’s really a passion” (Teacher, school 2). Contrary to a number of reports that have been written on trust and teacher unions in South Africa, this small article did not yield evidence that the unions were leading teachers to neglect their duties to attend union meetings or participate in strikes, as indicated in the Volmink et al. (2016) report. However, it did appear that where leadership from both district and school was weak or absent, unions provided support and development that was missing from the school leadership teams. This led to a lot of trust manifestations between staff and unions, particularly in the three schools with poor learning outcomes. This does support findings by other studies (De Clercq, 2013; Zengele, 2013; Govender, 2015) that teacher unions fill a vacuum when school and or district leadership is poor. A union rep and teacher from school 8 (LP) report that they feel responsible when things go wrong.

“No my role here at school is to make sure that the school is functioning very, very well. So if there are issues for example there are educators who don’t come to school on time, I have to make sure that those educators they don’t do that. So I have to make sure that the principal did talk with them then the principal reported back to me that your SATU members are not doing well here at school I have to go to SATU and report that no some of the educators here at school they are not doing very well so what can we do to make sure that they make the principal and the school going forward doing well so that our school is at the higher level so that the functionality at school is going very, very well, because some of us.”

It is clear from this citation that there is a leadership vacuum at this school, one that the union is very happy to fill. In terms of the trust, this will undoubtedly undermine trust in leadership, even if that leadership has done little to merit being trusted. This in the long term is detrimental to the well-functioning of the school, as the literature on trust in leadership reflects (see Ehren et al., 2018).

4. Parents-factors relating to relationships with parents

As reported previously, social issues such as parental alcoholism, poor levels of education, or a cultural and/or ethnic background that differs from school staff and/or leadership lead to a lack of trust between parents and the school. Unsurprisingly, although social ills were discussed in relation to HP schools, LP schools appeared to suffer disproportionately with problems emanating from deprivation, inequality, and the transient nature of some communities (shanty towns). This is a very common problem in South Africa, as many individuals migrate from rural areas and also from other African countries (Mlambo, 2018). Migrants suffer a great deal from food poverty and schools/teachers often have to step into the breach, providing meals for learners (Oldewage-Theron et al., 2006). Food poverty is present in both HP and LP schools. In rural schools, the issue is particularly acute, and a good deal of teacher time is taken up with resolving issues relating to malnutrition. This inhibits learning and performance, according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1991; McGarry and Shackleton, 2009). However, this was not confined to LP schools. Teachers in HP schools reported that some of the parents of such learners often refused to have anything to do with supporting their child, leaving this entirely to the school, as this teacher from school 1 reports, “parents are also giving up, (saying) do it on your own (the school, without parental support); which I think is a challenge.” (Teacher school 1, HP). As parental support is key to good learning outcomes (Desforges and Abouchaar, 2003), it is unsurprising that the teacher’s frustration in cases where parental support is lacking leads to a lack of trust between parents and teachers and this was evident across the board.

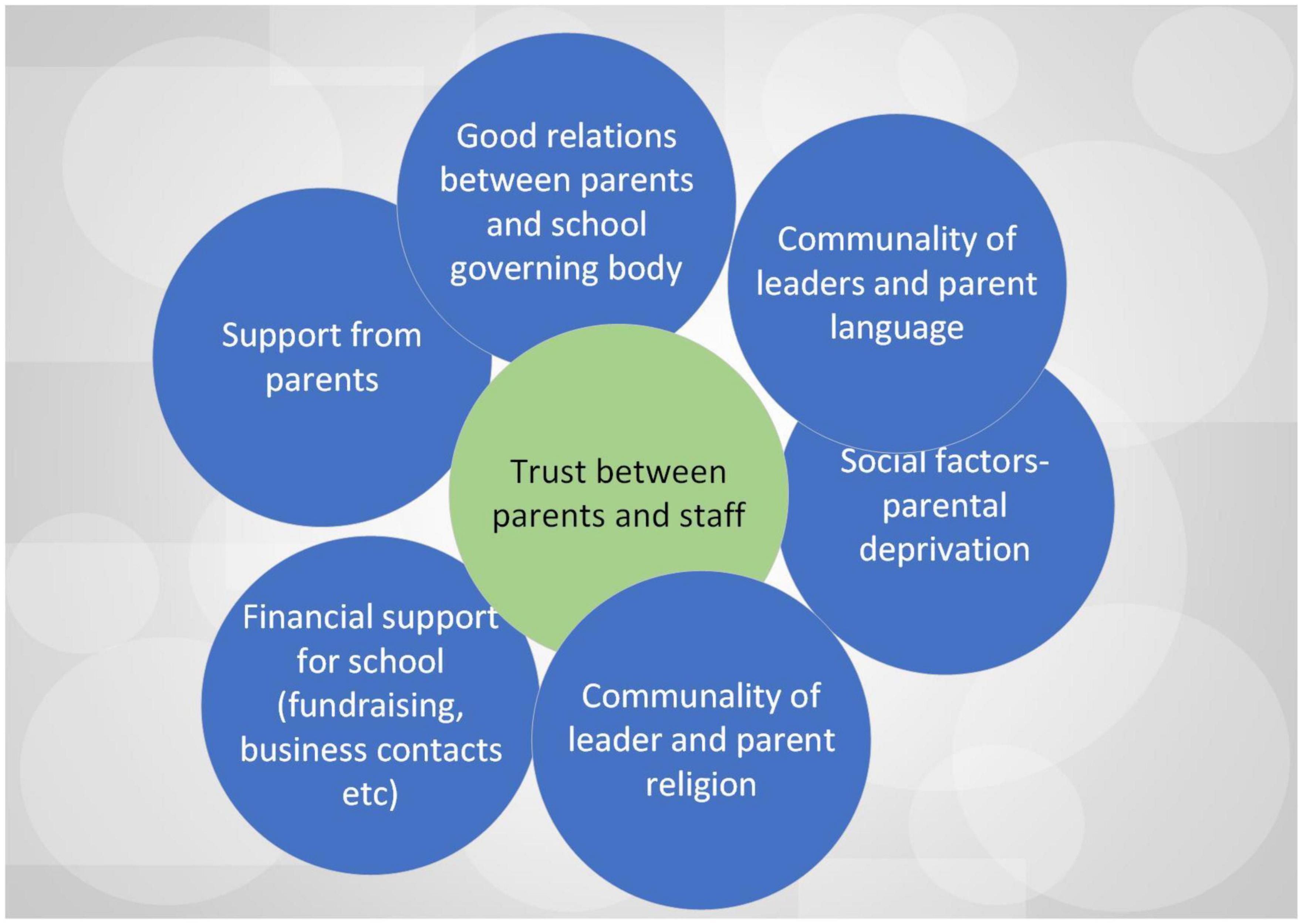

Across the eight schools, the findings from this section were linked strongly to several trust relationships, as indicated in Figure 3. As can be seen from the figure, governing bodies emerged as key factors in trusting and non-trusting relationships between school leadership and communities. We discuss this in what follows.

5. Governing body power and effectiveness and corruption and nepotism

School governing bodies, as mentioned earlier, are key to South Africa’s ideal of a democratic system of education (Van Wyk, 2004; Basson and Mestry, 2019). However, the literature on school governing in South Africa reflects the complexities of operationalizing this ideal (Basson and Mestry, 2019; Karlsson et al., 2020; Zuze and Juan, 2020). For example, although governing bodies are democratically elected, very often (as is the case in England too), those who have the most influence and economic power are elected. This is either for financial reasons or because they exert other types of influence in the community; for example, religious or cultural leadership (Buys et al., 2020).

In relation to our sample, in four schools (HP 2 and 6; and LP 3 and 8), participants stated that one reason to trust the leadership was the regular reporting of the principal to SGB. This is a core function of the executive/governance relationship. But, in this sample, there was no indication of whether this reporting was accurate and/or fair. Research in other contexts illustrates that this is a challenging area for boards in all contexts (Baxter, 2018; Baxter and John, 2021). However, it is concerning that there seemed to be a lack of awareness that this could be a difficult area, and that there is both support and challenge inherent within the role of the governor. Similarly, although in schools, 6, 4, and 7 participants indicated that frequent reporting of the SGB to parents instilled confidence in leadership, there is no indication of what was reported, and whether the criticism was invited. A key strength of a good governing body (Heystek, 2006) is that they are clear about its role and its function within it.

This sample revealed that in both HP and LP schools, the function of the SGB is seen as a supporting role, rather than as a critical friend, for example, a teacher in school 2 states, “Seeking new opportunities to make it easier for us, uhm in terms of giving us data projectors and they step into our classroom and see what needs to be done, my door is broken so I need a new door, they always support you, they don’t always support you like oh Loua (pseudonym) you a great teacher, I love what you do but the small things that you do like fixing your door, giving you a new floor, that’s the support they can give us to make the circumstances a bit easier and a bit nice for us to teach.” In school 8 (LP), the GB clearly do not understand their role, viewing it largely as a ceremonial one as this SGB member and teacher states, “Yes they’ve (SGB and leadership) (a) good relationship because even when we get these farewells and the parents meetings, they’re always there.” (teacher school 8-LP). Most concerningly, in school 8, The Chair of Governors and another teacher in the same school indicated that parents were largely passive, and even though they did not trust the SGB, “They never oppose them.” (Teacher 8). There were considerable issues in the LP schools (7, 8, and 4), in relation to SGB power, as this circuit manager explains, “people think if you belong to a political party, you have an entitlement to belong to a governing body of a school. Because you look at school as a place that have resources you can tap and use for yourself.” (Circuit Manager school speaking about schools 7 and 8 LP and 1 and 4 LP). This type of nepotism is certainly not restricted to the South African Context, as other studies from Africa and the US have shown (Metz, 2009, 2022; Buka et al., 2017). However, the power wielded by school governors in the South African context has been a cause for concern for some time, and it is precisely the amount of power combined with a lack of accountability of some school boards that presents the greatest problem for trust relations. As the literature illustrates, and as we have written elsewhere (Ehren and Baxter, 2021), a perceptual lack of integrity within the governing body, combined with their considerable amount of power, is a concerning dynamic for a public and democratically orientated education system (Ehren and Baxter, 2021).

Overall, it appeared across the board in both LP and HP schools, that the SGB was at best tolerated, for fundraising and associated functions, and at worst, seen as a detractor from the trust. This was largely due to perceptions of nepotism, mismanagement of funds, and poor understanding of the role. This teacher in an LP school explains how parents react to the SGB: “They say (the parents), Some of them (SGB) are bad, if they see a new car. “You bought a car with our money.” You are SGB. We know how things they are.” (4). One teacher in the same school described the Chair of governors as little more than the “principal’s puppet.” This element of the article relies on a code of moral conduct among governors, so that the perception of the communities may change accordingly. Although there may be few examples of outright corruption among governors, the very term “corruption” is contested (see, for example, Baxter, 2020, p. 78). In addition, there are hierarchies at play here, that is also at play in many successful school systems: it is impossible to eradicate hierarchies such as wealth, community influence, or innate prestige granted by individuals’ position in their community, see, for example, Ehren (2021) work on this in The Netherlands. In relation to schools, there is evidence that head teachers can mediate this type of hierarchy, depending on their level of leadership and political skills (Beauchamp and Vardaman, 2015).

6. Perceived attributes of the leadership team and culture of the school

Although this article adopts a relational and distributed view of leadership and trust, the perceived attributes of the senior leadership team were clearly influential, and this category saw the most substantial differences between LP and HP schools. In HP schools, principals were seen as reliable and invested in the aims of the school, supporting teachers, HoDs, and deputies. This appeared as a leitmotif throughout the data, infusing relations between deputies/HoDs and teachers. In two HP schools and one LP school, staff reported that the leadership was responsive to feedback and created a culture in which mistakes were seen as learning events. This in turn creates a culture of trust, as this teacher reports. In addition to this, staff in school 6 (HP) reported that leaders gave a background to decisions and why they were implemented; there were regular meetings between leadership teams and staff; and principals had an “open door policy.” Discretion in leaders was seen as a key factor in building trust in schools 2 and 6 (HP) and 3 and 4 (LP), and teaching was seen predominantly as the emotional and spiritual care of the pupil in both HP and LP schools. This conflated with trust in 80% of the data, with individuals whose caring manifests in their everyday work, leaders and teachers alike, were trusted. Even if their results in terms of learning outcomes were poor, their work was seen as valuable in socio-emotional terms instead. Personal attributes of leaders tended to be conflated with the culture of the school: where these were seen as positive, then the school culture was also perceived to be positive, even when operating in challenging contexts; however, the converse also seems to apply. Lack of trust in leadership in one LP school (3) led the teachers to seek support directly from the district officials, rather than HoDs or the head. Equally, the high dependency on unions for support, in school 3, indicated the high level of distrust in leadership and HoDs from teachers. In school 3 (L = P), the principal was off with stress and this immediately appeared to teachers that the principal cannot cope. While in school 6, a teacher reports, “the staff and management is also very, very important because often it, it, it feels like management are making all the decisions and teachers actually aren’t consulted or even let know.”

In the three HP schools, leaders described their strategies for creating a trusting culture, as this Principal in school 1 describes it’s…what I normally do in the morning when the bell goes, I go with the staff and I see to it that they are all in class. If there’s any problems they can come to me. Then I go to the school. Go from class to class. You know look, you know see the children in the class. And the same applies to the senior phase. If they come to me, I will not discuss anything they discuss with me with anybody else. Unless it’s something that involves other people, which will be people in the school. Or unless it’s against the law. Illegal things that they…then I need to involve other people as well.

They were also able to give tangible examples of how the trusting relationship works, as the same Principal reports:

But I haven’t had any…I had one incident and it was so hilarious. So absolutely hilarious. The traffic department came here and they said to me they would like to see one of the ladies. I said, “ok, why?” She’s got numerous outstanding fines. So I said “ok, did you bring your cuffs or did you bring cable ties?” He said “yes, I’ve got my cuffs.” I said, “sit. Have a seat. I’ll arrange coffee.” And I called the lady. And it was actually during break time. I said to her please come here. And when she came into the door and she saw this guy, she bounced back. And she immediately came around and stood behind me. She said, “meneer help-help.” I said “why?” No he’s going to do something. I said “ok, let him talk.” And he said, “ma’am, you’ve got numerous outstanding fines.” And that was just an indication that she knew she could trust me. That’s why she came to my side. Are you with me. So ja, that’s… But nothing happened. It was all in great fun. I don’t put pressure on people. I don’t put pressure on people. I allow them to develop within themselves and I’m there to assist them if anything goes wrong.

However, middle management trust came across as key, both in restoring trust between teachers and leadership, in cases where it had broken down and also in creating a culture of trust. This Head of the Department talks about why trust between her and teachers is so important to successful learning:

I think it is important to be trust because if you are trusted you are able to be accountable for what you are doing. There is nothing worse than being distrusted if I can put it that way. But I think you also have to earn the trust, in order for someone to trust you and I think you earn it by showing on a regular basis that you are that you are trustworthy, that you do the right thing, you don’t just do what everybody else tells you to do. Sometimes, being trustworthy especially in the upper management level, means often you have to be quiet about things, until the upper management is ready to share it with the school. So, you have to learn to be quiet at times about certain things (Teacher school 6-LP).

High performing schools were found to have larger numbers of extra-curricular activities, both after and during school. These activities were thought by many teachers to promote trust within the school and also in relation to building better relationships with teachers. This factor has been explored elsewhere and found to hold in other societies and education systems, particularly in relation to race (Flanagan, 2003; Rhoden, 2017).

Communication and leadership style was thought to be very important, both at HoD and SLT levels, and two schools, both LP, reported issues with a lack of openness in relation to the SLT, as this teacher reports (LP 6), “movement within the school communication not being open enough and whose role it is to be played in the management area.” Communication is discussed along with procedural aspects in the section which follows.

7. Procedural aspects: Accountability and communication

Procedural aspects relating to trust, along with perceptions of accountability, featured very highly in respondent discussions as both a building block for trust in leadership and a detractor. Detractors featured very highly in LP schools with several criticisms on both aspects. Respondents mentioned that leaders who treated teaching as purely ‘curriculum coverage’ rather than the complex social/human activity that teachers believe it is (as illustrated by the data in this article, along with a considerable body of literature (see, for example, Florio-Ruane, 2002; Ehren et al., 2018), attracted very low trust, which also impacted on perceptions of their capability. In LP school 7, one teacher talks about an internal quality management system that only highlights failure but fails to be used as a means of teacher support. Teachers in LP school 3 reports that “the department (of education for the province) can sometimes make the school “unorganized,” particularly when they rush the implementation of new policy and don’t give schools “proper planning.” The principal will come in and say, “the Department will expect this by so and so” and teachers are just expected to follow up” (teacher 3 LP). A lack of policies and infrastructure was also highlighted by the district official who explained.

Teachers still have to deliver the curriculum and “everything has to be up to date.” Their requests for support go unanswered and they are left to fend for themselves. No improvements have been made after the school has “written to the department, we’ve written to the union, we’ve written to the community councilor, (in relation to school 6).

A lack of a behavioral policy was reported by schools 3, 4, and 7 (LP), and a lack of detail on all aspects of planning and teaching improvement by three other LP schools were reported. This, according to respondents (teacher, HoD, and GB member), led to teachers being suspicious of any interventions to improve teaching, and a complete lack of trust in the leadership to run the school. In such cases, some teachers (3 and 7) also reported ‘a blame culture’, because so many mistakes were being made. In three of the six LP schools, accountability was seen as a negative trait, for example, in school 7, the English teacher understands accountability as being “submissive.” The implication was that teachers did not have enough trust in leadership to challenge them and honestly report that problems were occurring, and why.

In two out of the four LP schools, teachers referred to many unfilled posts: this was placing additional pressure on existing staff and undermining trust in the leadership to adequately manage staff recruitment and training. In addition, there was some doubt as to the quality of appointees and the transparency of the appointment process by staff in LP schools (3 and 7). In contrast, HP schools reported that the fair and transparent appointment and promotions system helped staff to trust the school leadership. Monitoring in LP schools appears to be thought of as something of a tick-box activity, with teachers reporting that: “The principal only stops by when you need to be monitored and the paperwork needs to be finished.” (7). In contrast, the HP schools (1, 2, 3, and 6) reported a robust, internal process of accountability with conflicts dealt with through open discussion (2, 5, and 6), in which the HoD is, “supportive of teacher issues and familiar with teacher performance, through regular and supportive monitoring” (1,2,6).

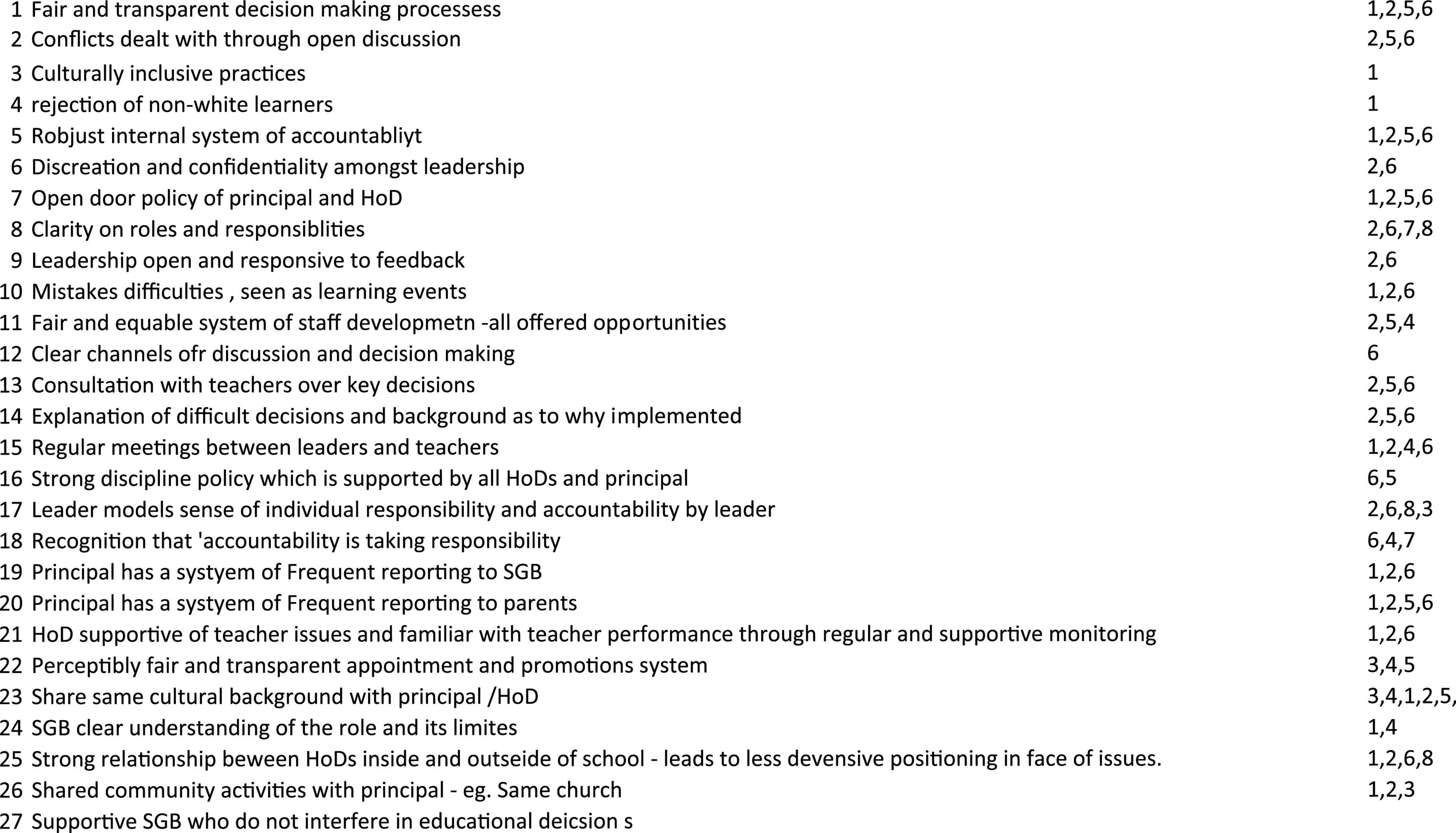

Although this is a very small sample of schools in a particular context, there were key factors that emerged both in promoting and detracting from trust in distributed leadership. They are summarized in Figures 4, 5. The implications of this article along with the conclusions are discussed in the next section.

8. Conclusion

This article set out to identify factors contributing to and detracting from trust in leadership in the context of South African primary schools. It identifies six key themes that emerge from the data, as being influential in exploring trust in leadership. In addition, it further identifies 31 key factors detracting from trust in leadership, and 29 factors contributing to it. Although it did not set out to be a comparison between high- and low-performing schools, choosing this sample did reveal some interesting differences and insights that can be taken forward in future research into the effects of trust and lack of it in leadership in primary schools in Africa. It also reveals the importance of contextual and historical elements, the antecedents of trust, mentioned earlier, that color presents attitudes to leadership.

In relation to the five aspects of relational trust outlined by Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer (2021), this research was successful in identifying four out of the five aspects, as listed below. There was not enough evidence to support or negate the intersubjective dimension of relational trust: ‘withness,’ consensus, and collegiality through shared language, a productive dialogic, sensemaking, problem-solving, activities, and community because they too were invested in the change agenda for their own teaching. A recommendation for future research would be to specifically investigate this particular element and its relationship to trust in leadership.

Edward-Groves’ Five elements of relational trust and where these were evidenced in the article.

| l. Interpersonal dimension | 2. Interactional dimension | 3. Intersubjective dimension | 4. Intellectual dimension | 5. Pragmatic dimension |

| HP & LPs | HP and l LP-s | No evidence o | HP & LP-s | HP and 1 LP |

Although there was evidence to support the other dimensions, the relationship between them and trust in senior leadership was not always evident, for example, where middle leaders demonstrated collegiality with teachers, this alone was not enough to make up for the lack of trust in senior leadership, nor was it influential enough to generate a culture of trust. The research indicated that only the senior leadership teams in this sample were influential enough to create a culture of trust. One in which distributed leadership and staff evidence trust in leadership. If this was absent, there was a tendency to (a) rely very heavily on a union for leadership and (b) over depend on other teachers for support, concomitantly undermining trust in leadership even further. Harris (2003) argument that distributed leadership is constrained by power relations within the school was supported in this article and evidenced by the hierarchical nature of the schools in our sample. Particularly low-performing schools where a dearth of basic management practices appeared to undermine the capacity to improve and also, to a certain extent, to exercise real leadership within the school. For example, the lack of effective internal accountability systems within three LP schools undermined the Head of the Department’s capacity to monitor, evaluate, and support staff. This led to a lack of trust in both HoD and stocktickerSLT. In LP schools, 7 and 8, a lack of trust in any activity labeled “accountability” also appeared to undermine any efforts to implement effective systems. In both low-performing schools, this was manifested by generalized distrust of professional dialogue, peer evaluation, and other processes linked to accountability. This was also noted in previous studies, such as Naicker and Mestry’s article, based on three Soweto primary schools (2011), which noted that “a shift from autocratic styles of leadership, hierarchical structures and non-participative decision making is needed if distributive leadership is to develop” (Naicker and Mestry, 2011, p. 12).

Our approach to trust in leadership as a purely relational function is problematic. While the article found policies and practices to be important in creating trust, these alone were not sufficient to create trust in leadership, particularly senior leadership. It also revealed that trust in leadership was not confined to the organization itself, but in the South African Context, it is heavily influenced by community and union relations too. This may not be the case in other contexts, which have more centralized systems of schooling and weaker unions, for example, England and the US, and would be a fruitful area for further research. In low-performing schools, the staff spoke much more about the personal traits of school leaders, again centered on their power in the community, but detrimentally. They were seen in terms of both negative understandings of accountability and fear of leaders’ power in the community. This led to a reluctance to speak out about problems and appeared to inhibit the formation of healthy communities of practice. This tends to support Bush and Glover (2014) in their assertions that while the academic discourse on leadership is changing, the realities of the SA context and culture act as constraints in relation to system-wide initiatives.

Although unions in many cases within this article appear to be doing good work in terms of staff development and support, thereby creating trust, there were also examples where they detracted from the leadership function, by compensating for weak leadership by over-intervention in operational matters.

The position of leaders in relation to their school or religious communities appears influential in lending credibility and trust to the SLT. In HP schools, leaders who appear to have credibility in those communities can build on this to implement processes and practices that encourage professional accountability and climates conducive to staff development. Improvement, with a continued conceptualization of leadership necessarily transformative, undermines the ideal of distributed leadership.

Lack of resources undermines trust in all of the contexts in which they occur. This was particularly evident in relation to school governing bodies, (SGBs) as leaders. Participants failed to see SGBs as leaders both in high- and low-performing schools, seeing them rather, as effective fundraisers or, in negative terms, as people who were often prone to misappropriate funds. SGB members seemed to lack understanding of their critical friend role, often deferring to principals, or seeing themselves as supportive “rubber stampers” for school leaders. In HP schools, this appeared not to detract from performance, but in LP schools, where SGBs were treated with suspicion and even dislike, this clearly contributed to a reduction in the capacity to lead and manage the school. Because SGB members were often influential in their local communities, this could result in an over-trusting attitude based on this, or a distrustful one; both equally harmful in relation to the actual leadership role of the SGB and its place at the heart of the SA democracy.

Since the abolition of apartheid, grassroots community control has been seen as the antithesis of state control (Sayed, 1999, P. 143); yet, this small project has shown that there is evidence that it still flourishes in some schools (Ngcobo, 2012) and highlights this in terms of the influence of ethnic identities and values, complicated by the fluidity of learner populations, especially in urban schools: This is compounded by migratory labor which brings rural values into sharp juxtaposition with the urban. Dealing with differing sub-cultures raises new challenges in terms of building trust in leadership, between schools and communities, and not least in handling tensions around differing values. We appreciate that while we attempt to consider different ethnicities in relation to their understanding of trust, we recognize that the article fails to consider the differing ethnicities in relation to both leadership and trust. This was out of scope in the funding we obtained to carry out the project on which this article is based and has been flagged for future research.

This research was based on the African context and located within eight schools revealing insights for schools more broadly. Although the sample is small, there is evidence that trust relations differ in HP and LP schools. However, the type of trust relations in HP schools aligns with findings from the literature on creating communities of education practice, while in LP schools, the trust relations often helped staff to bond in the face of poor leadership, accountability procedures, and organization (in some cases, they also appeared to create some forms of communities of professional practice too). Although some of these relationships may not directly enhance formal learning outcomes, in this article, they do seem to aid a form of collegiality and thus aid retention of staff and may help to mitigate absenteeism, a perennial problem in South African Primary education (Spaull and Kotze, 2015). They also appear to be emotionally supportive of teachers who are working in very demanding circumstances. The importance of these emotional support networks, aligned with the caring role of teachers for pupils living in the most adverse and challenging circumstances, would be a fruitful area for further research, particularly in relation to how far these supportive relationships also aid the creation of professional communities of practice.

While South Africa is contextually unique, the findings, particularly in relation to the development of internal accountability, the support of local communities, and the influence of unions can be used to investigate relational trust in education in other African countries, particularly in relation to the creation of citizenship behaviors in schools, which in turn contribute to social capital. In addition, schools themselves should be aware of the six key aspects identified in this article, as being key to trust in leadership at all levels, as well as being mindful of the 31 detractors (Figure 4) and contributors to trust (Figure 5) in this particular educational setting.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of restrictions related to country requirements. Requests to access the datasets can be made via the following website: https://www.jet.org.za.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Open University Ethics Committee/the Institute of Education Ethics Committee/the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This funding was received from the ESRC–Grant number: ES/P0058882. The payment for the APC is being provided by the Open University Library.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the UKRI (formerly DfID) grant number: ES/P005888/1 for the project and the collaboration with JET South Africa as project partner.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Addison, S. J. (2015). Using scenarios as part of a concurrent mixed methods design handbook of research methods on trust. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bakari, S. (2017). Why is South Africa still a developing country?. Munich: University Library of Munich. doi: 10.9756/IAJE/V5I2/1810012

Basson, P., and Mestry, R. (2019). Collaboration between school management teams and governing bodies in effectively managing public primary school finances. S. Afr. J. Educ. 39, 1–14.

Baxter, J. (2018). Schemes of delegation as governance tools: The case of multi academy trusts in education under reveiw. London: Sage.

Baxter, J. (2020). “Distrusting contexts and cultures and capacity for system level improvement,” in Trust, Accountablility and capacity in education system reform, eds M. C. M. Ehren and J. Baxer (London: Routledge), 78–102. doi: 10.4324/9780429344855-4

Baxter, J. A., and Cornforth, C. (2019). Governing collaborations: How boards engage with their communities in multi-academy trusts in England. Pub. Manag. Rev. 2, 1–23.

Baxter, J., and John, A. (2021). Strategy as learning in multi-academy trusts in England: Strategic thinking in action. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 41, 290–310. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1863777

Beauchamp, E. R., and Vardaman, J. M. Jr. (2015). Japanese education since 1945: A documentary study. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315703176

Boies, K., Fiset, J., and Gill, H. (2015). Communication and trust are key: Unlocking the relationship between leadership and team performance and creativity. Leadersh. Q. 26, 1080–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.07.007

Branson, C. M., Franken, M., and Penney, D. (2016). Middle leadership in higher education: A relational analysis. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 44, 128–145. doi: 10.1177/1741143214558575

Braynion, P. (2004). Power and leadership. J. Health Organ. Manag. 18, 447–463. doi: 10.1108/14777260410570009

Bryk, A. S., and Schneider, B. (2003). Trust in schools: A core resource for school reform. Educ. Leader. 60, 40–45.

Buka, A. M., Matiwane-Mcengwa, N. F., and Molepo, M. (2017). Sustaining good management practices in public schools: Decolonising principals’ minds for effective schools. Perspect. Educ. 35, 99–111. doi: 10.18820/2519593X/pie.v35i2.8

Bush, T., and Glover, D. (2014). Leadership development and learner outcomes: Evidence from South Africa. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Prac. 27:3.

Bush, T., and Glover, D. (2016). School leadership and management in South Africa. Int. J. Educa. Manag. 30, 211–231. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-07-2014-0101

Buys, M., du Plessis, P., and Mestry, R. (2020). The resourcefulness of school governing bodies in fundraising: Implications for the provision of quality education. South Afr. J. Educ. 40:2042. doi: 10.15700/saje.v40n4a2042

Cranston, J. (2011). Relational trust: The glue that binds a professional learning community. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 57, 59–72.

DBE (2017). Department of basic education annual report 2016/17, Vol. 14. Pretoria: South Africa Department of Basic Education.

DBESA (2013). Report on the annual national assessment of 2013. Pretoria: Department for Basic Education.

De Clercq, F. (2013). Professionalism in South African education: The challenges of developing teacher professional knowledge, practice, identity and voice. J. Educ. 57, 31–54.

de Clercq, F. (2014). Improving teachers’ practice in poorly performing primary schools: The trial of the GPLMS intervention in Gauteng. Educ. Chang. 18, 303–318. doi: 10.1080/16823206.2014.919234

Demirdoven, B., Cubuk, E. B. S., and Karkin, N. (2020). Establishing relational trust in e-participation: A systematic literature review to propose a model. Paper presented at the proceedings of the 13th international conference on theory and practice of electronic governance, New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. doi: 10.1145/3428502.3428549

Desforges, C., and Abouchaar, A. (2003). The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievement and adjustment: A literature review, Vol. 433. London: DfES.

Dietz, G., and Den Hartog, D. N. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Pers. Rev. 35, 557–588. doi: 10.1108/00483480610682299

Dirks, K. T., and Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 87:611. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611

Edwards-Groves, C., and Grootenboer, P. (2021). Conceptualising five dimensions of relational trust: Implications for middle leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 41, 260–283. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2021.1915761

Edwards-Groves, C., Grootenboer, P., and Ronnerman, K. (2016). Facilitating a culture of relational trust in school-based action research: Recognising the role of middle leaders. Educ. Action Res. 24, 369–386. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2015.1131175

Ehren, M. (2021). “Inner group trust and school autonomy in a segregated school system; parental self-segregation in the Netherlands,” in Trust, Accountability and capacity in education system reform, Vol. 1, eds M. Ehren Baxter (London: Routledge).

Ehren, M. C. M., and Baxter, J. (eds). (2021). Trust, accountability, and capacity in education system reform. Global perspectives in comparative education. London: Routledge.

Ehren, M., Baxter, J., and Paterson, A. (2018). Trust, capacity and accountability as conditions for education system improvement. South Africa: Jet Services.

Ehren, M., Paterson, A., and Baxter, J. (2020). Accountability, capacity and trust to improve learning outcomes in South Africa. Comparative case paper report. Johannesburg: JET Education South Africa JET Education South Africa.

Ehren, M. C. M., Paterson, A., Baxter, J., Taylor, N., and Chonco, N. (2019). Accountability and trust: two sides of the same coin? Paper presented at the RISE - research on improving systems of education center for global development, Washington, DC.

Fine, G. A., and Holyfield, L. (1996). Secrecy, trust, and dangerous leisure: Generating group cohesion in voluntary organizations. Soc. Psychol. Quarter. 14, 22–38.

Flanagan, C. (2003). Trust, identity, and civic hope. Appl. Dev. Sci. 7, 165–171. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_7

Fleisch, B. (2008). Primary education in crisis: Why South African schoolchildren underachieve in reading and mathematics. Claremont, CA: Juta and Company Ltd.

Florio-Ruane, S. (2002). More light: An argument for complexity in studies of teaching and teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 53, 205–215. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053003003

Goddard, R. D., Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, W. K. (2001). A multilevel examination of the distribution and effects of teacher trust in students and parents in urban elementary schools. Elem. Sch. J. 102, 3–17. doi: 10.1086/499690

Govender, L. (2015). Teacher unions’ participation in policy making: A South African case paper. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 45, 184–205. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2013.841467