- Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism, Prince of Songkla University, Phuket, Thailand

The educational sector has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the forced adaptation to online classes and students' lack of interaction and experience in practical classes. Because the hospitality and tourism industries require professional operations between guests and employees, this may cause concern among students who had to adapt to online classes during the pandemic about whether they have sufficient competencies to be recruited into the workplace. However, the internship benefits higher education institutions, industries, and students by examining the sufficiency of students' competencies in the workplace. Thus, this study aimed to determine the competencies of online learners that influence satisfaction in the employability of the hospitality and tourism industries post-COVID-19. The logistic regression models were established to predict the likelihood of competencies toward each satisfaction attribute. The empirical results showed that among five recruitment attributes, the competencies provided a predictor likelihood on three attributes: foundation, employability, and adaptability, while it had no likelihood on knowledge. The collaboration attribute reported the insignificant regression model. Moreover, only internship experience provided a significant result for the adaptive attribute. Moreover, the discussion and practical implications were provided in this study.

Introduction

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic in March 2020, it has impacted many sectors. Regarding public health protection, the educational sector was forced to develop more adaptable teaching methods to mitigate the effects, such as online learning (Schlesselman, 2020). The adaptation of emergency remote teaching (ERT) was one of the solutions used by educational institutes to maintain instructional continuity. However, this caused negative effects on students, such as a lack of socialization and peer interaction (Fuchs, 2021a), the impacts of technology on physical and mental health, a lack of time management, and a balance between life and education (Maqableh and Alia, 2021). In particular, the first-year students demonstrated lower satisfaction with ERT than the higher-year students, who are familiar with the use of technology in education (Fuchs, 2021b). In addition, online learning creates problems for students regarding distraction and reduced focus, psychological issues, and management issues (Maqableh and Alia, 2021).

Since the universities were looking for e-learning tools to facilitate the online environment for practical classes and laboratory experiences (Van Nuland et al., 2020), these can jeopardize university education's long-term practicality (Muftahu, 2020). In their study, Xhelili et al. (2021) found that students were less likely to succeed with online learning than in a traditional classroom setting due to their lack of experience with technology. When it comes to adapting online teaching approaches to help students deal with stressful situations, online learning has presented difficulties for universities just as much as it does for students (Barbour et al., 2020). Fuchs (2021b) suggested in his study that the ERT should be further carried out to increase the preparedness and quality of future teaching methods.

Since March 2020, students have been participating in online or hybrid classes. Regarding the limitations of online teaching methods, students need to acquire sufficient experience in operation-based learning and training. However, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be abating since the restrictions were lifted; tourists have started traveling, and businesses have resumed. Therefore, the students that learned theoretical and practical skills via online teaching became a part of the industries as employees or interns. Industries expect students to acquire sufficient theoretical knowledge and practical skills in educational institutes for working capability.

The hospitality and tourism industries are mainly operation-based and require adequate hands-on experience and practical skills. Therefore, these industries expect students to achieve practical skills rather than theoretical knowledge. Therefore, the situation would lead to a problem from both industrial and academic perspectives. From the industry perspective, it would be unclear whether the students taught via online learning have sufficient capability and skills to work. Further, from the academic perspective, this would be an assessment of the capability to adapt online teaching methods, which could solve the dilemma of the continuity of online learning.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine the competencies of online learners that influence satisfaction in the employability of the hospitality and tourism industries post-COVID-19. A questionnaire survey was used to better understand employers' perspectives on the efficiency of working interns who were forced to experience ERT and online classes since 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Phuket, Thailand, was the subject of this study because it was an important tourist destination that generated 20% of the country's tourism revenue before the pandemic (Economics Tourism, 2019). Moreover, 94% of the gross provincial product (GPP) relied on the service sector, including the hospitality and tourism businesses Office of the National Economic Social Development Council. (2019). Since the launch of the “Phuket Sandbox Model” in July 2021 Royal Thai Embassy. (2021), the Phuket tourism industry has been in a recovery phase, as indicated by the increasing number of tourists, the improvement in the employment rate, and the decreasing number of job seekers (Chuenniran, 2022).

Literature review

Internship research

Internships are valuable for integrating classroom-based learning with actual industrial operations, commonly found in the hospitality and tourism curriculum, to promote the learning experience (Robinson et al., 2016). Throughout the program, a learner gains knowledge, skills, and value from direct on-the-job experience that reflects on working. The internship's focus has been highly appreciated by higher education institutions (HEIs), companies, and students since it produces mutually beneficial outcomes for all three parties. The internship can prepare graduates for direct employment in the industries.

An internship offers HEIs a way to connect classroom learning with practical work experience (Stansbie et al., 2016) and allows students to become more familiar with the workplace (Ruhanen et al., 2013). From the industry's perspective, a well-educated and skilled workforce contributes to market success. The industry is aware of the advantages of having an effective internship (Lam and Ching, 2007), such as motivated and inexpensive staff (Divine et al., 2008; Verney et al., 2009), a cost-effective provisional period before recruiting (Szadvari, 2008), and improving the graduates' employability skills to meet the requirements of the industry (Yang et al., 2015). For students, internships provide an opportunity to understand the labor market and develop relationships with the industry (Marinakou and Giousmpasoglou, 2013). Students also gain insights into their careers before making decisions (Wang et al., 2014) and may be offered full-time employment after the internship (Collins, 2002).

Chen et al. (2018) stated that all parties involved in the internship process, including HEIs, employers, and students, achieved positive benefits from an effective internship program. However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, the competencies of hospitality and tourism students may be affected by online classes that need more practical skills. Finally, this would make employer satisfaction with employment different from the period before the pandemic. Following this, we examined the expected competencies in the hospitality and tourism industries, employer satisfaction with the recruitment opportunity, and the factors influencing internship evaluation.

Competencies in the hospitality and tourism industries

Students' employability is the utmost priority of HEIs, as it is seen as the qualities of a graduate equipped with sufficient skills to remain in employment in the industries (Asonitou, 2015). Employability represents a multi-dimensional construct, and several researchers encountered several challenges. However, Harvey (2001) summarized that employability consists of five elements: job type, timing, attributes of recruitment, continuing education, and employability skills. Misra and Mishra (2011) expanded the elements to include soft skills such as willingness, attitude, motivation, and flexibility. The internship programs improve the student's skills toward employability, such as communication, interaction, morality, critical thinking, problem-solving capabilities, adaptability, flexibility (Blackwell et al., 2001), emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, reflection, and life experience (Pool and Sewell, 2007). Moreover, many academics have defined what is meant by “competency” in the context of the workplace; for example, Finch et al. (2013) identified 17 such abilities, while Moolman and Wilkinson (2014) tallied up 90.

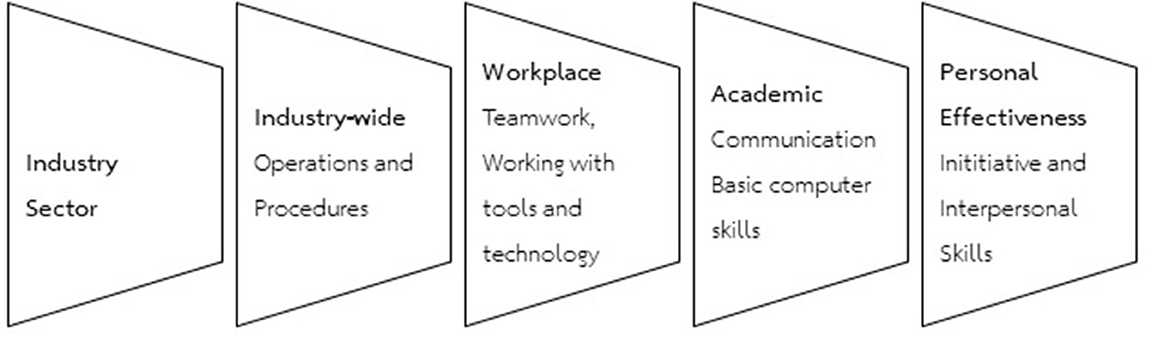

Wang and Tsai (2014) examined the above competency models and found two components to employability: general and specific skills. The specific skills are the professional capabilities applicable to industries, and some research suggests that it is useful to focus on professional industry skills. Regarding the professional competencies in the hospitality and tourism industries, a comprehensive competency model for the hospitality, tourism, and events industries has been developed by the Employment and Training Administration (ETA) and the National Travel and Tourism Office of the Department of Commerce (Employment Training Administration., 2017). As shown in Figure 1, the model suggests a range of competencies, from generic to specific, in terms of knowledge, skills, and abilities in the hospitality and tourism industries.

Figure 1. Hospitality and Tourism Competencies summarised from the ETA model (Employment Training Administration., 2017).

Unlike other industries, the hospitality and tourism industries require both professional and soft skills. Soft skills are important, as are other skills, to support customer satisfaction, which is the pinnacle of success in customer-centric businesses. The soft skills required in the hospitality and tourism industries include the interaction between employees and guests, customer service, networking, communication, flexibility, language, commitment, can-do attitude, multitasking, and cultural awareness (Giannotti, n.d.). Moreover, the industries expect graduates to be equipped with the essential operational competencies and personal skills such as working in a team, motivation, problem-solving (Jacob et al., 2006), time management, communication, and teamwork (Maelah et al., 2012). Chen et al. (2018) found that some general competencies, such as leadership, teamwork, and language skills, did not significantly improve after the internship.

Employer satisfaction with the employment

At the end of the internship, students are evaluated on whether they demonstrated sufficient competencies and performance to attain employer satisfaction. Employer satisfaction with internships helps to effectively forecast the increase in post-graduation employment, and the satisfaction is related to how well the educational institution prepares the students for their actual work in the industries.

Completing internships effectively increases students' opportunities to get employment since employers prefer graduates with some work experience. The experiences gained from internships can support the managerial competencies needed to prepare a graduate to enter the hospitality workforce (Jack et al., 2017). Ring et al. (2008) indicated that internships could provide prominent training for students to develop their competencies, thus increasing their chances of getting a job. Successful internship programs depend on the mutual understanding of three stakeholders: HEIs, employers, and students. Chen et al. (2018) found that students' satisfaction with educational institutions and self-commitment influence employability, but the satisfaction of students with employers has no effect. However, this omits the factors that affect the satisfaction of employers, and there is room for researchers to identify these factors.

Employer satisfaction with internships can be measured broadly. However, this research adopted the employer satisfaction survey (ESS), covering the expected criteria of employers. The ESS was developed by the Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) and funded by the Department of Education, Skills, and Employment of the Australian Government (Quality Indicators for Learning Teaching., 2021). The ESS has been used in Australian higher education institutions in several fields of study to determine the quality of the institutions in the preparation of graduates to enter the workforce. The surveys on the internship programs contributed to both universities in terms of the continuous improvement of course structures and students in terms of the opportunities for potential advancement and requested jobs. The ESS includes five graduate attribute domains, which are (1) foundation skills, such as general literacy, numeracy, and communication skills, (2) adaptive skills, such as the ability to adapt and apply skills and knowledge, (3) collaborative skills such as teamwork and interpersonal skills, (4) technical skills such as the application of professional and technical knowledge, and (5) employability skills such as the ability to perform and innovate in the workplace.

Factors influencing the working performance

Gender diversity impacts human behaviors such as thinking styles, knowledge, skills, and values, causing different cognitive skills and, therefore, significant effects on firm performance (Kilduff et al., 2000). Biologically, men are more rational, independent, decisive, and aggressive, and women are more gentle, interpersonal, and sensitive. Moreover, in terms of working behavior, men are more task-oriented, dominant, and hierarchical, while women are more people-oriented, interpersonal, and democratic (Eagly and Carli, 2003). Moreover, gender provides a significant difference in company performance, which has been widely examined in studies such as looking at both antecedents and outcomes of job satisfaction (Rutherford et al., 2014) and investigating emotional exhaustion (Hui et al., 2022). An internship experience is another factor that influences the working performance of the interns because experiences can be a part of an effective learning style (Kolb, 1984). People with experience in the working atmosphere would acquire the knowledge relevant to the job in terms of familiarity, characteristics, proper processes, and procedures. As a result, the experience can support managing similar tasks and situations in the future.

The conceptual framework

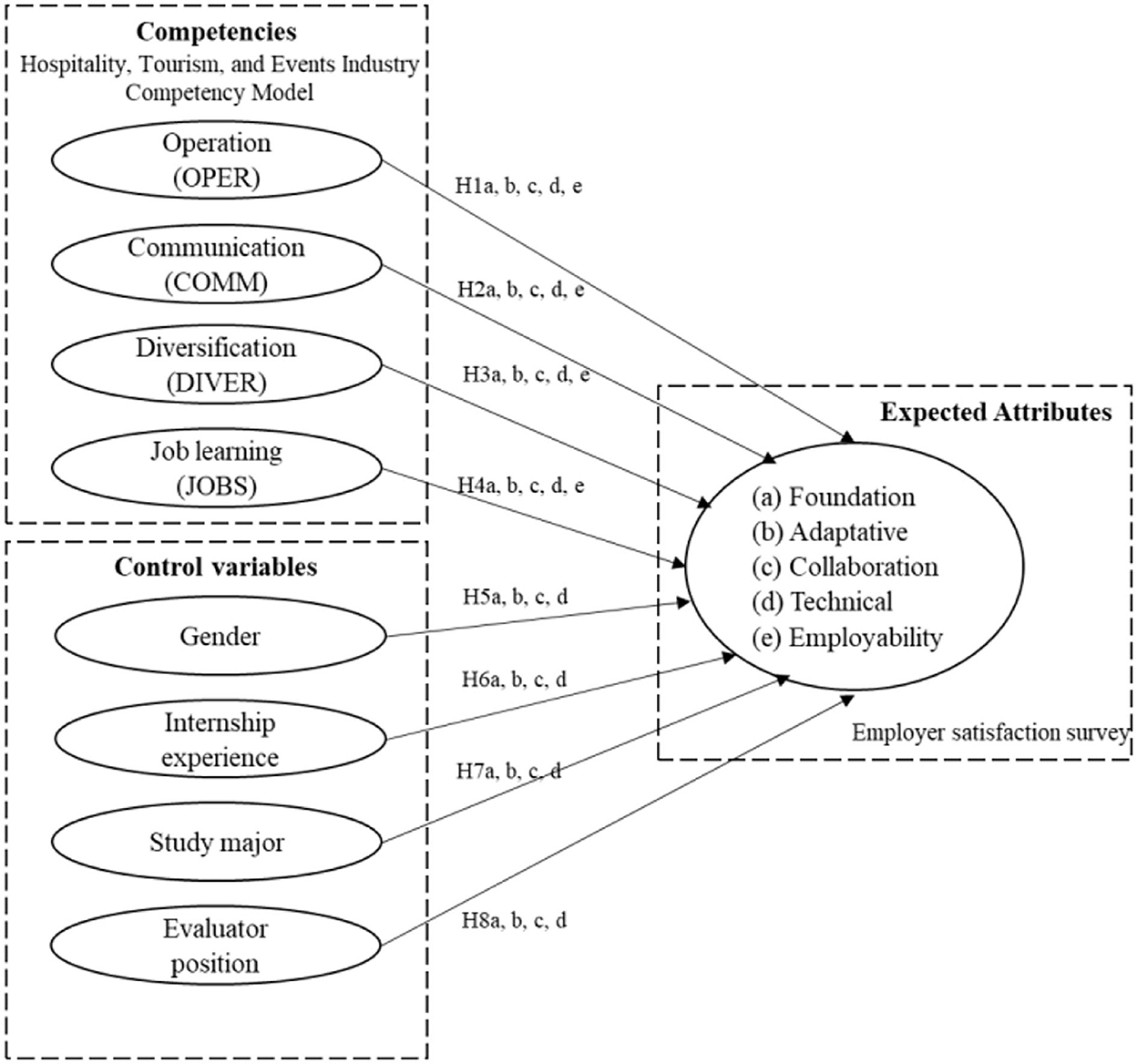

As can be seen in Figure 2, this research establishes the conceptual framework based on the Hospitality, Tourism, and Events Industry Competency Model (Employment Training Administration., 2017), which includes four competencies. The industry-wide competency is represented by sufficient operational skills (OPER). Workplace competency is represented by working in a diversified environment in the tourism industry (DIVER). Academic competency refers to using communication skills in the workplace (COMM). Last, personal effectiveness competency refers to the ability to learn from jobs (JOBS).

This research adopted the ESS (Quality Indicators for Learning Teaching., 2021) to measure satisfaction in five different attributes: (1) foundational skills, such as general literacy, numeracy, and communication skills, (2) adaptive skills, such as the ability to adapt and apply skills and knowledge, (3) collaborative skills such as teamwork and interpersonal skills, (4) technical skills such as the application of professional and technical knowledge, and (5) employability skills such as the ability to perform and innovate in the workplace.

Regarding the satisfaction theory (Oliver, 1980), satisfaction can be reached by comparing perceived and actual performance. When the actual performance exceeds the perception, satisfaction is achieved. To gauge employer satisfaction with internships, if the students perform their competencies beyond the expectations of employers, satisfaction could exist. However, as there are many required competencies in the hospitality and tourism industries and many attributes that cause employer satisfaction, this study argues that identifying the students' competencies will influence the satisfaction of employers post-COVID-19. At the same time, the demographic factors of students, such as gender, internship experience, evaluator position, and study major, are examined in the context of employer satisfaction. Therefore, based on the research objectives, the following hypotheses have been outlined:

H1: Operation competency significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

H2: Communication competency significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

H3: Diversification competency significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

H4: Job learning competency significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

H5: Gender significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

H6: Internship experience significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

H7: Study major significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

H8: Evaluator position significantly influences employers' expected attributes.

Methodology

Data collection

The research was established as an explanatory study using hypothesis testing with a mono-quantitative approach. Data were collected through a questionnaire survey in the hospitality and tourism businesses where undergraduate students of the Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism at Prince of Songkla University in Phuket, Thailand, applied for internships from January to May 2022.

Since March 2020, these students have been participating in the hybrid classroom as online learners forced them to adapt to emergency remote teaching. They were allowed to freely choose the internship sites in the hospitality and tourism industries. The data collection was carried out between April and May 2022 as one of the requirements for internship evaluation from the supervisors and/or department managers who closely monitored the interns.

The questionnaire was designed by the authors and approved by the internship committee of the faculty. The main purpose of the questionnaire was to use it as an evaluation at the end of the internship programs by the employers. The employers were asked to evaluate students undertaking an internship at their sites. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: categorical questions asking demographic profiles, 5-point-Likert-scale questions requesting the level of agreement on the performed competencies, and dichotomous questions asking which satisfaction attributes were reached to be employed. The students were asked to download the questionnaire from the learning management system and upload the completed questionnaire anonymously to protect the respondents' identities.

Sample profiles

Two hundred sixty-nine respondents participated in the survey, but 25 were removed because of missing data, and two were removed because they stated that they did not recruit interns. Finally, there were 242 respondents left from the survey. As shown in Figure 3, 38.8% (n = 94) of the respondents were department managers, and 61.2% (n = 148) were supervisors. Of the students, 25.2% (n = 61) of them were men and 74.8% (n = 181) were women. Moreover, 47.1% (n = 114) of students had no experience in the internship, and 52.9% (n = 128) participated in their second internship. Lastly, 55.8% (n = 135) of students were in the tourism major, and 44.2% (n = 107) were in the hospitality major.

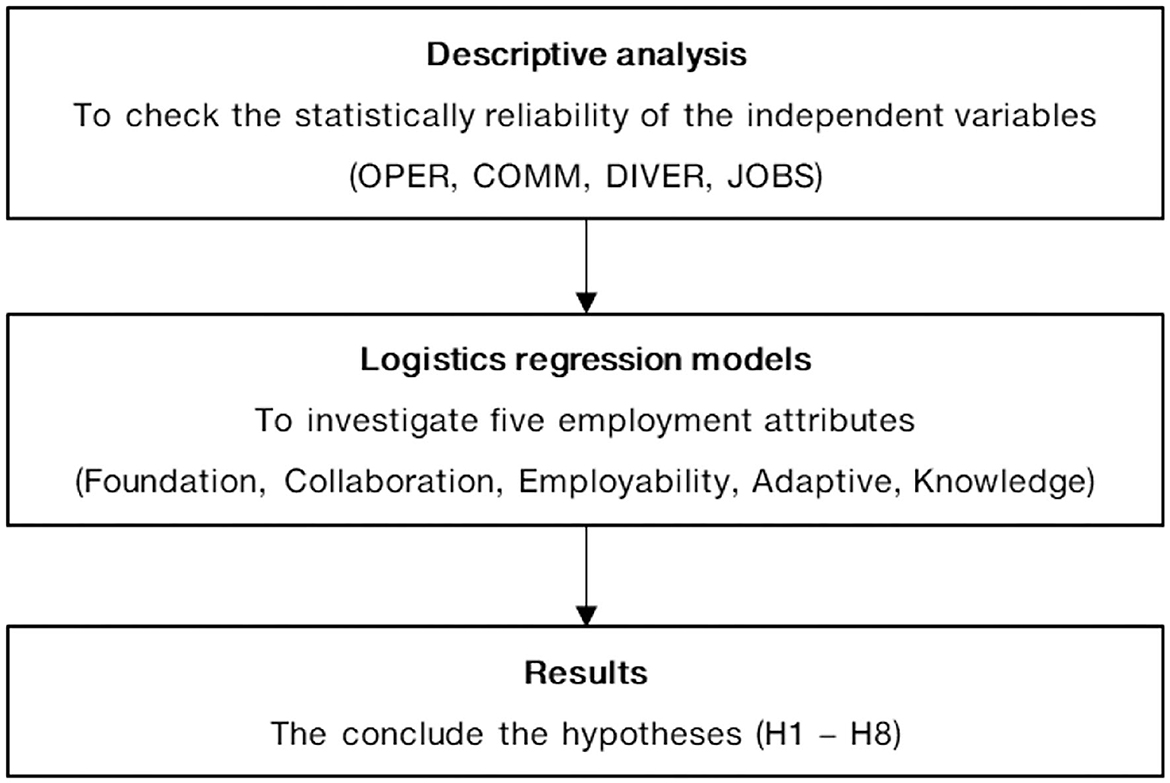

Data analysis

As can be seen in Figure 4, this study sets the analytical framework into two steps. First, descriptive analysis was used to test the statistical reliability of the independent variables (OPER, COMM, DIVER, and JOBS). Second, direct logistic regressions were performed to assess the significance of the influential factors on the required attributes of the industry post-crisis. Five attributes—foundation, adaptability, collaboration, knowledge, and employability—were tested separately in five logistic regression models. Each model contained eight independent variables, including four competencies (OPER, COMM, DIVER, and JOBS) and four control variables, including gender, internship experience, study major, and the evaluator's position.

Findings and discussion

Descriptive analysis

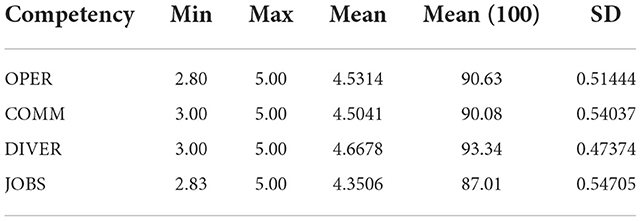

Using the IPM SPSS software, all 5-point Likert questions relevant to each independent variable presented a Cronbach's alpha of higher than 0.7 as follows: 0.879 (OPER), 0.882 (COMM), 0.894 (DIVER), and 0.877 (JOBS), indicating the questions combined in the scale were internally consistent in their measurement (Saunders et al., 2019). As can be seen in Table 1, all competencies reported a high mean value. Three variables reported a score of more than 90, while job learning skills (JOBS) reported the lowest score of 87 out of 100.

Logistic regression models

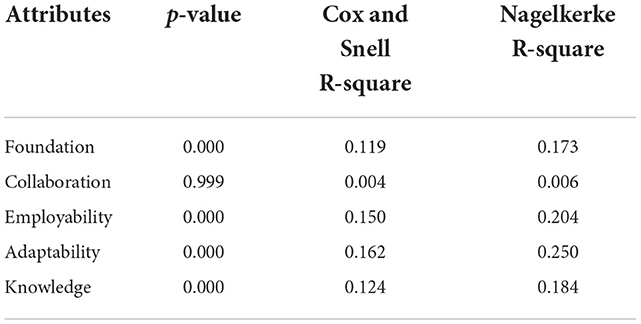

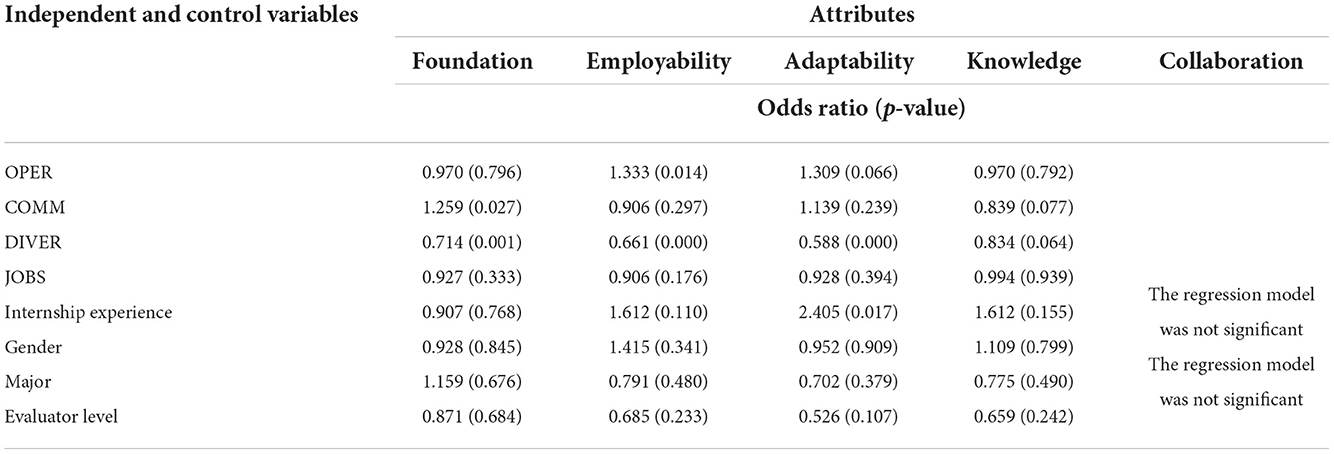

Five logistic regression models were performed and reported in Table 2. Four models (foundation, employability, adaptive, and knowledge) reported that the full model containing all predictors was statistically significant, indicating that the models were able to distinguish between respondents who considered and who did not consider the independent variables for each recruitment attribute. However, the collaboration model provided non-statistical significance, which indicated that the independent variables could not predict the likelihood of the attribute.

The foundation model explained between 11.9% (Cox & Snell R-Square) and 17.3% (Nagelkerke R-Square) of the variance and correctly classified 74.8% of cases. The employability model explained between 15.0 and 20.4% of the variance and correctly classified 71.9% of cases. Further, the adaptability model explained between 16.2 and 25.0% of the variance and correctly classified 81.8% of cases. Lastly, the knowledge model explained between 12.4 and 18.4% of the variance and correctly classified 78.9% of cases.

As seen in Table 3, the foundation model presented only two independent variables that made a unique statistically significant contribution to the model: COMM (p = 0.027, odds ratio of 1.259) and DIVER (p = 0.001, odds ratio of 0.714). This indicated that the communication competency was more likely considered 1.25 times for the attribute. The odds ratio of 0.714 for diversification competency indicates that the skills were likely to improve the consideration of personality in job recruitment.

Next, the employability model presented only two independent variables that made a unique statistically significant contribution to the model: OPER (p = 0.014, odds ratio of 1.333) and DIVER (p = 000, odds ratio of 0.661). This indicated that the operation competency was more likely considered 1.33 times for the attribute. The odds ratio of 0.661 for diversification competency indicates that the skill inversely affected this attribute in job recruitment. Next, the adaptability model presented an independent variable that made a unique statistically significant contribution (DIVER: p = 000, an odd ratio of 0.588). This indicates that skill also inversely affected this attribute in job recruitment. Also, a control variable provided the statistical significance (Internship experience: p = 0.017, odds ratio of 2.405), indicating that the strongest likelihood of this attribute was internship experience. Last, the knowledge model presented showed that none of the variables contributed statistically significantly to the model.

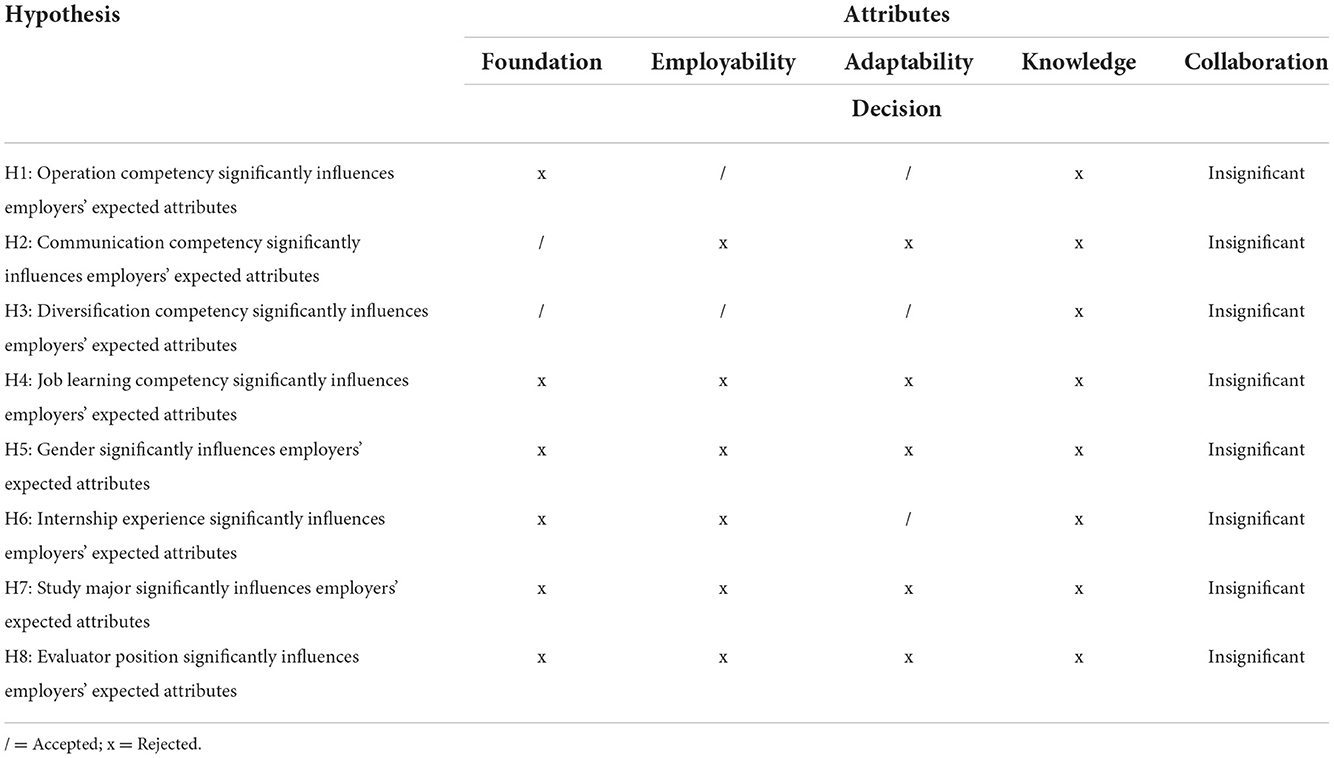

Therefore, the hypothesis results are reported in Table 4. The H1 hypothesis was accepted only in two attributes, which indicates that the operation's competency influences only employability and adaptability attributes expected by the employers. Furthermore, communication competency (H2) significantly influences the foundation attribute. The diversification competency (H3) influences three attributes, foundation, employability, and adaptability, in the inverse direction as the odds ratio is less than one. The job-learning competency (H4) reported no influence on the employers' expected attributes.

In terms of the control variables, only internship experience (H6) was accepted, which indicates that the internship experience influences the adaptability attribute. Other control variables (H5, H7, and H8) reported no influence on the employers' expected attributes.

Discussion and implication

Employee performance is crucial to improving labor-intensive industries such as hospitality and tourism. The industries expect competent graduates who have been equipped with both knowledge and sufficient practical skills. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic forced HEIs to adopt the online learning mechanism. Therefore, this challenge raised the question of whether the industries would satisfy online learners' competencies for their employment. The result of this study reflects that the online learners' competencies met the requirements of the industries. Three levels of competency, which are operational skills (OPER), diversification in workplaces (DIVER), and communication skills (COMM), received a score of more than 90%, while job learning (JOBS) received a slightly lower score of 87%. From the educational institutions' points of view, the students have sufficiently acquired both specific and general competencies from the online classes. The diversification skills received the highest score, implying that students learned this skill from the class and also self-adapted it to their personalities. However, HEIs may adopt a new mechanism to support online classes to balance the learning experience, especially in communication skills. Since the nature of the hospitality and tourism curriculum requires students' hands-on practical classes throughout their studies, educational institutions should be concerned that the results of operational and job-related competencies may differ between face-to-face and online classes. However, it is suggested that educational institutions still need to integrate internships into the curriculum, even though the classes are conducted online. The internship can help students gain job-learning skills that may be lacking during online classes. Moreover, from the industry's point of view, the results showed that the employees were satisfied with the fact that the online learners were equipped with competencies and skill sets that were sufficiently developed from the online courses during the pandemic, especially diversification skills.

As a practical implication, the HEIs can take advantage of the digital transformation approach to become a modern learning space for all. This could help not only students but also teachers to improve their digital literacy and the improvement of institutions' operational performances. Some courses should be offered online by the HEIs. This would provide an option for students who would like to study online. Courses could be designed to meet the mutual needs of learners and industries, such as business model canvas and other business-related courses. Providing this service can enhance revenue generation, customer segments, and the reputation of the HEIs.

In terms of employability, diversification competency is the most significant influential factor, as the logistic models provided a predictor likelihood for three employment satisfaction attributes: foundation, employability, and adaptability. However, job learning competency is the least significant factor as it was not a predictor of satisfaction. This implies that, during the internship, the employers looked at the student's work behaviors rather than their operational skills. Moreover, the knowledge attribute reported no likelihood of any competencies, which suggested that the competencies would not reflect the required knowledge for employment. Since companies care more about the adaptability and dynamics of their employees in the post-crisis period than they do about their knowledge and skills, HEIs should educate their students with these qualities.

Moreover, regarding the logistic regression models, gender, study major, and evaluator position did not influence any attribute toward the recruitment decision. However, the industry prefers experienced interns as the internship experience provides a likelihood of the adaptive attribute. This confirms that the HEIs and students could realize the importance of integrating work experience during their studies. Supported by the learning experience (Kolb, 1984), the experienced students may better understand organizational norms at the workplace, while the first-time interns need more time to blend into the organization. However, in contrast to the previous study (Kilduff et al., 2000), the student gender does not affect the acquired competencies from the online or hybrid classes.

Finally, this study contributes to the theoretical advancements of students' competencies in the recruitment opportunity post-COVID-19 pandemic, especially in a destination with a high intensity of hospitality and tourism industries. The results provided evidence of changes in employers' perceptions and requirements of graduates with hospitality and tourism degrees. Personal behaviors are more vital in recruitment opportunities than knowledge and skills acquired from educational institutions.

Conclusion and limitation

The concern about the efficiency of students who encountered online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of the required competencies by the hospitality and tourism industries has been brought into this research. The research objective was to determine how online learners' competencies influence employers' satisfaction with employment post-COVID-19. The empirical results showed that diversification competency plays the most significant role in influencing three employer satisfaction attributes toward employment: foundation, employability, and adaptability. Operation competency influences employability and adaptability, while communication influences only the foundation attribute; job-learning competency does not influence any attributes. Moreover, only the internship experience significantly influences only one satisfaction attribute, adaptability, while other control variables do not. Moreover, this study provides insight into the expected competencies in the post-pandemic hospitality and tourism industries. HEIs and students should realize that industries recruit graduates based on behaviors rather than knowledge and skills acquired from institutions.

However, this study has limitations that require further study. First, the scope of the study was grounded in a mass-tourist destination during the economic rebound period from the pandemic. In places with fewer tourists, results may differ. Further, future research is expected to investigate the significance of the relationship between competencies and employability by conducting a qualitative approach to augment the results based on this study to analyze employers' perceptions, expectations, and preferences on employment post-pandemic. Finally, since one satisfaction attribute, collaboration, yielded insignificant models, future research is required to confirm this phenomenon.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies were approved by the internship committee of the Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism, Prince of Songkla University. The study was exempted from the ethical approval as it used data from the student evaluation at the end of the internship programs.

Author contributions

KS: the conception of the work, drafting and revising the work critically for important intellectual content, the analysis, and interpretation of data for the work, and providing approval for publication of the content. CW: the acquisition and data preparation, drafting and revising the questionnaire, and agree to be accountable for ensuring that questions related to the integrity of any part of the work are appropriate. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism, Prince of Songkla University supported this research project under the Research Fund.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Asonitou, S. (2015). Employability skills in higher education and the case of Greece. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 175, 283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1202

Barbour, M. K., LaBonte, R., Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., et al. (2020). Understanding pandemic pedagogy: Differences between emergency remote, remote, and online teaching. State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada. 1–24.

Blackwell, A., Bowes, L. L, Harvey, A. H., and Knight, P. (2001). Transforming work experience in higher education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 27, 269–285. doi: 10.1080/01411920120048304

Chen, T. L., Shen, C. C., and Gosling, M. (2018). Does employability increase with internship satisfaction? Enhanced employability and internship satisfaction in a hospitality program. J. Hospit. Leisure Sport Tour. Educ. 22, 88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2018.04.001

Chuenniran, A. (2022). Phuket Sandbox' bags B66bn. Retrieved from Bangkok Post. Available online at: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2315882/phuket-sandbox-bags-b66bn (accessed May 26, 2022).

Collins, A. (2002). Gateway to the real world, industrial training: Dilemmas and problems. Tour. Manag. 23, 93–96. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00058-9

Divine, R., Miller, R., Wilson, J. H., and Linrud, J. (2008). Key philosophical decisions to consider when designing an internship program. J. Manag. Market. Res. 12, 1–8. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237506884

Eagly, A., and Carli, L. (2003). Finding gender advantage and disadvantage: Systematic research integration is the solution. Leadership Quart. 14, 851–859. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.003

Economics Tourism and Sports Division. (2019). Revenue from Tourists. Bangkok: Ministry of Tourism and Sports.

Employment Training Administration. (2017). Hospitality, Tourism, and Events Competency Model. Retrieved from CareerOneStop. Available online at: https://www.careeronestop.org/CompetencyModel/competency-models/pyramid-download.aspx?industry=hospitality (accessed July 5, 2022).

Finch, D., Hamilton, L., Baldwin, R., and Zehner, M. (2013). An exploratory study of factors affecting undergraduate employability. Educ. Train. 55, 681–704. doi: 10.1108/ET-07-2012-0077

Fuchs, K. (2021a). Advances in Tourism Education: A Qualitative Inquiry about Emergency Remote Teaching in Higher Education. J. Environ. Manag. Tourism 12, 538–543. doi: 10.14505//jemt.v12.2(50).23

Fuchs, K. (2021b). Emergency remote teaching during COVID-19: A comparison of student perception. Educ. Quart. Rev. 593–599. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/wgf9q

Giannotti, F. (n.d.). Top 10 hospitality tourism soft skills. Retrieved from EHL Insights. Available online at: https://hospitalityinsights.ehl.edu/top-10-soft-skills-hospitality-tourism (accessed July 5 2022).

Harvey, L. (2001). Defining and measuring employability. Quality Higher Educ. 7, 97–109. doi: 10.1080/13538320120059990

Hui, Q., Yao, C., Li, M., and You, X. (2022). Upward social comparison sensitivity on teachers' emotional exhaustion: A moderated moderation model of self-esteem and gender. J. Affect. Disor. 299, 568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.081

Jack, K., Stansbie, P., and Sciarini, M. (2017). An examination of the role played by internships in nurturing management competencies in Hospitality and Tourism Management (HTM) students. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 17, 17–33. doi: 10.1080/15313220.2016.1268946

Jacob, S., Huui, L. M., and Ing, S. (2006). “Employer satisfaction with graduate skills - a case study from malaysian business enterprises,” in International Conference on Business and Information (BAI 2006), Singapore.

Kilduff, M., Angelmar, R., and Mehra, A. (2000). Top management-team diversity and firm performance: Examining the role of cognitions. Organizat. Sci. 11, 21–34. doi: 10.1287/orsc.11.1.21.12569

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (Vol 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lam, T., and Ching, L. (2007). An exploratory study of an internship program: The case of Hong Kong students. Int. J. Hospit. Manage. 26, 336–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.01.001

Maelah, R., Aman, A., Mohamed, Z., and Ramli, R. (2012). Enhancing soft skills of accounting undergraduates through industrial training. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 59, 541–549. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.312

Maqableh, M., and Alia, M. (2021). Evaluation online learning of undergraduate students under lockdown amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: The online learning experience and students' satisfaction. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 128, 106160. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106160

Marinakou, E., and Giousmpasoglou, C. (2013). An investigation of student satisfaction from hospitality internship programs in Greece. J. Tour. Hospit. Manag. 1, 103–112. doi: 10.5614/ajht.2013.12.1.04

Misra, R., and Mishra, P. (2011). Employability skills: The conceptual framework and scale development. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 46, 650–660. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23070486

Moolman, H., and Wilkinson, A. (2014). Essential generic attributes for enhancing the employability of hospitality management graduates. Turizam: znanstveno-stručni časopis 62, 257–276. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287322825

Muftahu, M. (2020). Higher education and covid-19 pandemic: Matters arising and the challenges of sustaining academic programs in developing African universities. Int. J. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 417–423. doi: 10.24331/ijere.776470

Office of the National Economic Social Development Council. (2019). Gross Regional and Provincial Product Chain Volume Measure 2019 Edition. Bangkok: Office of the National Economic Social Development Council. Available online at: https://www.nesdc.go.th/nesdb_en/ewt_w3c/ewt_dl_link.php?filename=national_accountandnid=4317 (accesed May 22, 2022).

Oliver, R. (1980). “Theoretical bases of consumer satisfaction research: review, critique, and future direction,” in Theoretical Development in Marketing, eds. C. Lamb, and P. Dunne (Chicago: American Marketing Association), 203–210.

Pool, L., and Sewell, P. (2007). The key to employability: Developing a practical model of graduate employability. Educ. Train. 49, 277–289. doi: 10.1108/00400910710754435

Quality Indicators for Learning Teaching. (2021). Employer Satisfaction Survey. Retrieved from Quality Indicators for Learning Teaching. Available online at: https://www.qilt.edu.au/surveys/employer-satisfaction-survey-(ess) (accessed July 5, 2022).

Ring, A., Dickinger, A., and Wöber, K. (2008). Designing the ideal undergraduate program in tourism: Expectations from industry and educators. J. Travel Res. 48, 106–121. doi: 10.1177/0047287508328789

Robinson, R., Ruhanen, L., and Breakey, N. (2016). Tourism and hospitality internships: Influences on student career aspirations. Curr. Issues Tour. 19, 513–527. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1020772

Royal Thai Embassy. (2021). Phuket Sandbox. Available online at: https://thaiembdc.org/, https://thaiembdc.org/phuketsandbox/ (accessed November 28, 2021).

Ruhanen, L., Robinson, R., and Breakey, N. (2013). A foreign assignment: Internships and international students. J. Hospit. Tour. Manage. 20, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2013.05.005

Rutherford, B. N. W, Marshall, G., and Park, J. (2014). The moderating effects of gender and inside versus outside sales role in multifaceted job satisfaction. J. Business Res. 67, 1850–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.12.004

Saunders, M. N., Lewis, P., and Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students (8 ed.). UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Schlesselman, L. S. (2020). Perspective from a Teaching and Learning Center during Emergency Remote Teaching. Am. J. Pharmac. Educ. 84, ajpe8142. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8142

Stansbie, P., Nash, R., and Chang, S. (2016). Linking internships and classroom learning: A case study examination of hospitality and tourism management students. J. Hospit. Leisure Sport Tour. Educ. 19, 19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2016.07.001

Szadvari, L. (2008). “Management buy-in: The most crucial component of successful internship programs,” in NACE Journal.

Van Nuland, S. E., Hall, E., and Langley, N. R. (2020). STEM crisis teaching: Curriculum design with e-learning tools. FASEB BioAdv. 2, 631–637. doi: 10.1096/fba.2020-00049

Verney, T. P., Holoviak, S. J., and Winter, A. S. (2009). Enhancing the reliability of internship evaluations. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 9, 1–12. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266334834

Wang, Y. F., Chiang, M. H., and Lee, Y. J. (2014). The relationships amongst the intern anxiety, internship outcomes, and career commitment of hospitality college students. J. Hospit. Leisure Sport Tour. Educ. 15, 86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2014.06.005

Wang, Y. F., and Tsai, C. T. (2014). Employability of hospitality graduates: Student and industry perspectives. J. Hospit. Tour. Educ. 26, 125–135. doi: 10.1080/10963758.2014.935221

Xhelili, P., Ibrahimi, E., Rruci, E., and Sheme, K. (2021). Adaptation and perception of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic by Albanian university students. Int. J. Stud. Educ. 3, 103–111. doi: 10.46328/ijonse.49

Keywords: online learning, COVID-19, Phuket, tourism competency, employability, hospitality and tourism education, internship, higher education

Citation: Sincharoenkul K and Witthayasirikul C (2022) Can online learners obtain sufficient competencies in the hospitality and tourism industries? Front. Educ. 7:996377. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.996377

Received: 17 July 2022; Accepted: 31 October 2022;

Published: 02 December 2022.

Edited by:

Nattavud Pimpa, Mahidol University, ThailandReviewed by:

Mawardi - Mawardi, Padang State University, IndonesiaSoolakshna Lukea Bhiwajee, University of Technology, Mauritius, Mauritius

Copyright © 2022 Sincharoenkul and Witthayasirikul. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kris Sincharoenkul, a3Jpcy5zJiN4MDAwNDA7cGh1a2V0LnBzdS5hYy50aA==; Chotima Witthayasirikul, Y2hvdGltYS53JiN4MDAwNDA7cGh1a2V0LnBzdS5hYy50aA==

Kris Sincharoenkul

Kris Sincharoenkul Chotima Witthayasirikul

Chotima Witthayasirikul