Introduction

As educationalists, purporting to inspire those we teach, Hook (2003, p. 21) asks us to “move beyond the restricted confines of a familiar social order”. If we can do this on a regular basis, we become accustomed to occupying different standpoints, challenging norms and allow our angle of vision to adjust and deepen (Hook, 2003; Addison and Burgess, 2020; Ogier and Tutchell, 2021). Stevens and Martell (2019) suggest that this is how we start to disrupt and shape our teaching practice to become more contemporaneous with a gender transformative society (Stromquist, 2015). A critical and “disruptive” review of practice demands a conscious revision of curriculums, publications, and resources within our teaching (National Society for Education in Art and Design, 2021) in response to contemporary societal awareness and an issue-based educational agenda (Li, 2018). Gender responsive education (Gibbs, 2021) is an approach that inclusively identifies and addresses the needs and standpoints of all. As Hooks (2003) recognizes, entering into something that is not familiar, new and different, can positively dislocate our teaching habits. Dislocated awareness (Addison, 2007) enables educators, particularly teachers entering the profession, to develop a conscious awareness toward gender identity to “transform stereotypes, attitudes, norms and practices” (Gibbs, 2021, p. 6) by challenging power relations, rethinking norms and raising critical consciousness (Hall, 2010).

A patriarchal knowledge base

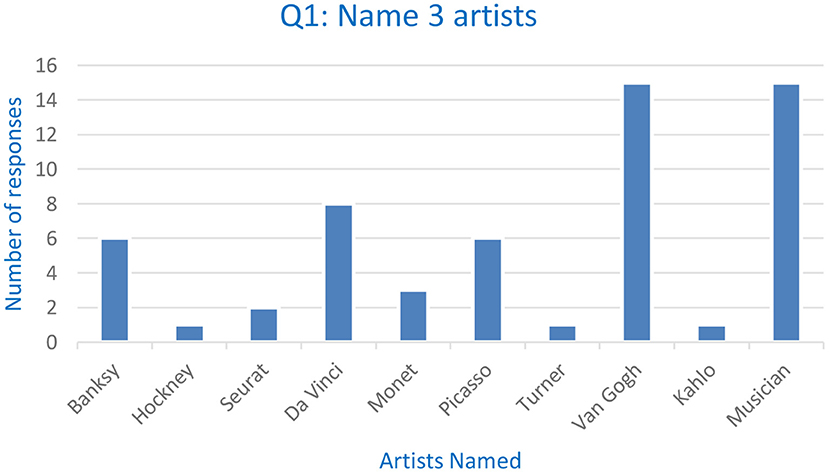

ITT art educators at an institution in the south of England have long noticed that undergraduates have a good recall of male artists, but rarely refer to female artists in part one of their studies (Ching, 2015). To test that this hypothesis was correct, in November 2021 twenty-two students on a 3-year undergraduate teacher training course, were asked to write names of three artists they knew. Out of fifty-eight artists identified, thirty-five were dead, white and male, with only one female artist mentioned; Frida Kahlo (see Figure 1). Interestingly, fifteen responses interpreted musicians as artists. The majority cited Banksy, Da Vinci and Van Gogh. Such is the art appreciation knowledge base that many trainee teacher students possess because this is what they were exposed to during their own art education or through popular culture (Smith and Dawes, 2014). As qualified teachers enter school, unless otherwise enlightened, art appreciation that is diverse, culturally aware and gender representational of today's society, will remain untouched (Ching, 2015). Similarly, the same group of twenty-two students were asked

to name three authors. In contrast, these students were able to complete the task and the balance between female and male authors listed was very close. This contrasts greatly with the results from the list of artists, with thirty-two female authors and thirty-four male authors listed, showing an equal distribution between authors of classic, modern, fiction and non-fiction writing, aimed a range of age-groups. In summary, this activity suggests that the students have a greater working knowledge of authors than artists.

Challenging the canon with confident awareness

The so-called “greats”, the male canons of the art world, remain entrenched in an ethnocentric school curriculum (Harris and Clarke, 2011) and, as such, lessons in art continue to rely on the familiar “founding fathers” of classical twentieth century art practice; Matisse, Picasso, Kandinsky, Van Gogh (Battista, 2015, p. 12). There exists a “mismatch between what pupils are taught and their lived experience” (Harris and Clarke, 2011, p. 160) and a curriculum which is continually reproduced and replicated year after year irrelevant of the wider social world of the children and their demographic (Bullen and Kenway, 2005). The education of art in schools mirrors a curriculum that continues to stereotype what society recognizes as an artist, “white, preferably middle class, and above all, male.” (Longman Saltz, 2017, p. 3).

Stevens and Martell (2019) discuss making resolute the intention to train emergent teachers about gender equitable practices in the classroom where the curriculum and all those named within it reflect the class of children being taught (Coates, 2009; Sanders and Gubes Vaz, 2014). The curriculum taught is meant to resonate, expand on and develop the existence and discoveries of everyday life, then it is the duty of educators to actively deconstruct what remains staid, stereotypical and archaic (Grumet and Stone, 2000). By supporting this area of practice, the development of gender sensitive and responsive classrooms can be facilitated (Nind et al., 2012; Gibbs, 2021) to challenge the “male-default setting” of the primary school (Hames, 2016, p. 14).

The canon of literature has long protected the legacy of male-generated material which still influences lists today (Marsh, 2004). However, some writers of classic children's literature forged ahead to challenge and subvert stereotypes “of racial, class or gender superiority” (Stephens, 1992, p. 51). For example, in the ground-breaking Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Carroll played with Victorian values and their accepted representations of feminine and masculine behaviors; leading Alice to question her own identity through multiple representations of her physical appearance and to make sense of her isolation in a world that she did not fit, or understand (Sparrman, 2020).

Similarly, fairy tales have continually undergone transformations from their original form because they are a perfect vehicle for re-telling to suit a changing, more modern audience, raising awareness of social justice through a liberal feminist lens (Earles, 2017). Modern readers no longer expect princesses to wait passively for rescue, they rescue themselves, they are resilient and brave (Marshall, 2004). While role reversal tropes have succeeded in raising the profile of strong independent female characters, it remains that this is often at the expense of the traditional male hero (Reynolds, 2011). This approach can be criticized for leading the reader further down a rabbit hole in seeking to understand gender balance (Marshall, 2004). While this is certainly an improvement to earlier iterations of gender idealized characters, it does not go far enough in disrupting dominant discourses around social justice, as discussed by DePalma “… pedagogy of representation is much easier to conceptualize and describe than a pedagogy that seeks to trouble the existing social order” (2016, p. 837).

Developing a diverse curriculum toward a gender responsive education

If we avoid using our subjects to help define and explore identity (Buchanan et al., 2020), we are ultimately making schools less accepting, less safe (Hsieh and Meng-Jung, 2021) and archaically stereotypical for all children who live in a more forward thinking 21st century (Wolfgang, 2020). Reddy (2018) questions the value of the current teaching canon by asking “how can [educators] contribute to a society that is non-racial, non-sexist, and non-discriminatory, where all people can recognize each other's differences… [and] how do we embrace our diverse classrooms?” (2018, p. 165). Harris et al. (2022) additionally purport that “Power structures in schools may still emphasize heterosexuality and gender-conformity as a desirable norm.” Harris et al. (2022, p. 155). Reddy goes on to posit the view that attempts to plug the gap by providing short bursts of teaching around an issue, such as gender equality, is ineffective toward developing long-term attitudinal change in students. Instead, Reddy, as DePalma (2016) inferred, favors a complete shake-up of the curriculum to deeply embed the intersectionality of such bias and additionally address the:

“[h]idden curriculum… [which] refers to a side effect of education [where] lessons that are learned but not openly intended, such as the transmission of norms, values, and beliefs conveyed in the classroom and the social environment of the campus [or school]” (Reddy, 2018, p. 163).

Diversifying the curriculum through cultural agency has been discussed across decades and is now a key focus in educational institutions (Brookfield, 2007). The narrative of dominant gender is being subverted to a much greater extent in 2021, through the gathering pace of movements raising awareness of inequalities in marginalized groups, such as Stonewall, Black Lives Matter and the MeToo movement.

Peabody's approach to curriculum design demonstrates one way that awareness can be achieved (2021). Taking the traditional Grimm's Tales, Peabody embraces folk tales in an “inter-cultural way” (2021, p. 88). Peabody introduces folk tales from distinct cultures alongside these more familiar re-tellings, to develop a rich discourse between students about a shared history of storytelling (Sparrman, 2020). This enables students to engage with alternative perspectives that focus through a situational lens, such as “cultural nationalism, but with quite different implications due to systems of power and oppression that emerge at the intersection of folklore and colonization” (Peabody, 2021, p. 88). Influenced by key writers (Zipes, 2014; Thibodeaux, 2017), Peabody demonstrates that by incorporating diversity within classroom settings, we can be agents of change and not follow “the danger of a single story” (Adichie, 2009).

Gender responsive approach: Empowering a sense of self

Identity as a construct (Berger and Luckmann, 1984; Foucault, 1984; Addison, 2012), and societal expectations of gendered behaviors and responsibilities are unconsciously reinforced in our culture (Gibbs, 2021). For example, we are given colors assigned at birth to represent who we are; blue for a boy and pink for a girl; boys are stronger, girls are weaker, and so on (Hames, 2016). This serves to perpetuate the myth that if one does not identify with the “norm” one is seen as being “other” or marginal (Green-Barteet and Coste, 2019).

By adopting a queer hypothesis, gender binaries can be replaced with gender neutral signifiers, such as using value free descriptions, which may prevent “potentially damaging beliefs such as… rigid gender stereotypes” (Kneeskern and Reeder, 2020, p. 1472). This is noticeable in children's literature, where there is an attempt to develop books that include characters who are gender neutral but remain described as non-normative (Green-Barteet and Coste, 2019). The picture book Perfectly Norman, by Percival (2017), offers young readers a story about a boy described as “always been normal” (2017, p. 4). From the start, the audience are left to decide what “normal” means and how it might be measured. The character progresses to a fictional non-normative state, which is finally accepted by others around him. An ambition of the writer may have been to offer young children, and possibly their adult reader, an opportunity to learn about equality through an illustrated book, which that mirrors the text and adds meaning (Gamble, 2013), but Percival does not wholly master the gender neutral, value free paradigm as suggested by Anderson (2014).

However, this is more successfully achieved in Julián is a Mermaid by Love (2018), which follows a young child inspired to fulfill a wish to take part in the Mermaid Parade. Encouraged by Julián's grandmother, Julián is free to explore identity through the clothing, jewelry, and make-up of Julián's choosing. This book is value free and a good model of social justice. It should be remembered that these early reading experiences support children in making sense of the world around them to become critical thinkers (Iser, 1972; Rosenblatt, 1994; Reynolds, 2011).

Addison (2005, p. 29) advocates art and design education as an impactful disjunction and “a sort of ‘other' within the logocentric curriculum,... [to] challenge the normalizing function of schooling and provide a space for difference.” The process of self-exploration within the social and interactive space of classroom provides a locus for identity and sense of self (Addison, 2007, 2012). Queer orientations through the practice of art can help young people see the possibilities beyond the binary (Morabito, 2022) and develop “the expressive means to give voice to their feelings and come to some understanding of self” (Addison, 2005, p. 20).

New transformative educational resources are available which challenge traditional gendered materials in art teaching (Hoekstra, 2015). The “Beyond the Binary” exhibition (2021–2022) at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, UK, for example, worked with artists and artist educators to explore the global diversity of sexual and gender identities in education (Beyond the Binary, 2021–2022). The exhibition offered alternative understandings of contemporary artists who use their practice to question gender norms (Jarvis, 2011). Gibbs (2021) affirms the need to train teachers in how to use materials (art and literature) and promote gender equality in their teaching practice, to foster an environment that embraces children's sense of self-discovery and so feel confident about their identity (Ashburn, 2007). Visual culture (Doyle and Jones, 2006, p. 614) “in all its multiplicity and variety” accomplishes extension and redefinition of our expanding and redefining our thinking about identity.

Conclusion

In summary, the past affects the present which in turn affects the future (Stevens and Martell, 2019). Using students' interests and demographic as a contemporaneous starting point for teaching about gender equity is time well spent (Stevens and Martell, 2019). Whether discussing art and literature or any other curriculum subject, our task, as tutors, should be to invoke in our students a collaborative courage and a collective conscious-raising for change (Mindel, 2018). Hopper (2001), writing about the female artist, proposed that:

As informed and reflective practitioners, such teachers will be able to introduce the important and thought-provoking work of women artists and provide future generations not only with reflections on essentially female experiences but also with women as artists and role models' (2002, p. 318).

Taking this view as inspiration, by advocating a more heterogeneous outlook in students' art or English lessons, it follows that we can foster a richer enculturing of art and literature in their schools (Stromquist, 2014). Reviewing practice through the lens of representation, old and new, across the gender-identity spectrum to “promote the principles of diversity” (Adam, 2021, p. 1), is key to raising confidence in our students. A culture that explores and liberates unchartered territories and collective agency (Stromquist, 2015) can interpolate new beginnings and provide a locus for our emerging, young and inspirational art and English teachers (Zwirn, 2006; Addison, 2007). In this way, educationalists will become their own confident conscious-aware agents of change and gender transformative education will become embedded in their practice (Gibbs, 2021). Equally, and importantly, concurrent with the recommendations from the UK Feminista and NEU study (2019) an increase in agential instructor confidence will enable students to draw from a wider, richer and equitable resource base going forward that reflects a changing educational society (NEU, 2019).

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adam, H. (2021). When authenticity goes missing: how monocultural children's literature is silencing the voices and contributing to invisibility of children from minority backgrounds. Educ. Sci. 11, 32. doi: 10.3390/educsci11010032

Addison, N. (2005). Expressing the not-said: art and design and the formation of sexual identities. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 24, 20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2005.00420.x

Addison, N. (2007). Identity politics and the queering of art education: inclusion and the confessional route to salvation. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 26, 10–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2007.00505.x

Addison, N. (2012). Fallen angel: making a space for queer identities in schools. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 16, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.655492

Addison, N., and Burgess, L. (2020). Debates in Art and Design Education, 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Adichie, C. N. (2009). The Danger of a Single Story. TED: Ideas worth Spreading. Available online at: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The danger of a single story | TED Talk (accessed May 21, 2022).

Anderson, L. (2014). Are the kids all right? The representation of LGBTQ characters in children's and young adult literature, by B. J. Epstein (review). Child. Literat. Assoc. Q. 39, 449–451. doi: 10.1353/chq.2014.0051

Ashburn, L. (2007). Photography in pink classrooms. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 26, 31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2007.00507.x

Battista, K. (2015). New critical positions: disrupting a white feminist canon. Third Text 29, 397–412. doi: 10.1080/09528822.2016.1169636

Berger, P. L., and Luckmann, T. (1984). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York, NY: Pelican.

Brookfield, S. (2007). Diversifying curriculum as the practice of repressive tolerance. Teach. High. Educ. 12, 557–568. doi: 10.1080/13562510701595085

Buchanan, L. B., Tschida, C., Bellows, E., and Shear, S. B. (2020). Positioning children's literature to confront the persistent avoidance of LGBTQ topics among elementary preservice teachers. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 44, 169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jssr.2019.01.006

Bullen, E., and Kenway, J. (2005). Bourdieu, subculture capital and risky girlhood. Theory Res. Educ. 3, 47–61. doi: 10.1177/1477878505049834

Ching, C. (2015). Teaching contemporary art in primary schools. Athens J. Human. Arts 2, 95–110. doi: 10.30958/ajha.2-2-3

Coates, S. (2009). “The child's conception of gender,” in Identity, Gender, and Sexuality: 150 years After Freud. 2nd Edn., eds P. Fonagy, R. Krause, and M. Leuzinger-Bohleber (London: Karnac Books).

DePalma, R. (2016). Gay penguins, sissy ducklings … and beyond? Exploring gender and sexuality diversity through children's literature'. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 37, 828–845. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2014.936712

Doyle, J., and Jones, A. (2006). Introduction: new feminist theories of visual culture. Signs 31, 607–615. doi: 10.1086/499288

Earles, J. (2017). Reading gender: a feminist, queer approach to children's literature and children's discursive agency. Gend. Educ. 29, 369–388. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2016.1156062

Foucault, M. (1984). “Sex, power, and the politics of identity. interview by Bob Gallagher and Andrew Wilson,” in Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, ed P. Rabinow (London: Allen Lane), 164–73.

Gamble, N. (2013). Exploring Children's Literature: Reading With Pleasure and Purpose. 3rd Edn. London: Sage.

Gibbs, M. (2021). Gender Transformative Education: Reimagining Education for a More Just and Inclusive World. New York, NY: United Nations Children's Fund

Green-Barteet, M., and Coste, J. (2019). Non-normative bodies, queer identities: marginalizing queer girls in YA dystopian literature. Girlhood Stud. 12, 82–97. doi: 10.3167/ghs.2019.120108

Grumet, M., and Stone, L. (2000). Feminism and curriculum: getting our act together. J. Curric. Stud. 32, 183–197. doi: 10.1080/002202700182709

Hall, J. (2010). Making Art, teaching Art, learning art: exploring the concept of the artist teacher. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 29, 103–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2010.01636.x

Hames, H. (2016). ‘Before I realized they were all women… I expected it to be more about materials': art, gender and tacit subjectivity. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 35, 20. doi: 10.1111/jade.12043

Harris, R., and Clarke, G. (2011). Embracing diversity in the history curriculum: a study of the challenges facing trainee teachers'. Camb. J. Educ. 41, 159–175. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2011.572863

Harris, R., Wilson-Daily, A. E., and Fuller, G. (2022). ‘I just want to feel like I'm part of everyone else': how schools unintentionally contribute to the isolation of students who identify as LGBT+. Camb. J. Educ. 52, 155–173. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2021.1965091

Hoekstra, M. (2015). The problematic nature of the artist teacher concept and implications for pedagogical practice. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 34, 349–357. doi: 10.1111/jade.12090

Hopper, G. (2001). Women in art: the last taboo. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 20, 311–319. doi: 10.1111/1468-5949.00280

Hsieh, K., and Meng-Jung, Y. (2021). Deconstructing dichotomies: lesson on queering the (mis)representations of LGBTQ+ in preservice art teacher education. Stud. Art Educ. 62, 370–392. doi: 10.1080/00393541.2021.1975490

Iser, W. (1972). The reading process: a phenomenological approach. New Lit. Hist. 3, 279–299. doi: 10.2307/468316

Jarvis, M. (2011). What teachers can learn from the practice of artists. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 30, 307–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8070.2011.01694.x

Kneeskern, E. E., and Reeder, P. A. (2020). Examining the impact of fiction literature on children's gender stereotypes. Curr. Psychol. 41, 1472–1485. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00686-4

Li, D. (2018). Using issues-based art education to facilitate middle school students' learning in racial issues. Inter. J. Edu. Art. 19.

Longman Saltz, J. (2017). Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?' Linda Nochlin Didn't Just Ask the Un-Askable, She Forced the Art World to Give a Better Answer. Available online at: https://www.vulture.com/2017/10/art-history-can-be-divided-before-linda-nochlin-and-after.html

Marsh, J. (2004). The primary canon: a critical review. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 52, 249–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2004.00266.x

Marshall, E. (2004). Stripping for the wolf: rethinking representations of gender in children's literature. Read. Res. Q. 39, 256–270. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.39.3.1

Mindel, C. (2018). Exploring, developing, facilitating individual practice while learning to become a teacher of art, craft and design. Int. J. Art Design Educ. 37, 177–186. doi: 10.1111/jade.12098

Morabito, J. P. (2022). Weaving beyond the binary. Text. Cloth Cult. 20:1–15. doi: 10.1080/14759756.2022.2046365

National Society for Education in Art Design. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nsead.org/.

NEU (2019). It's Just Everywhere – Sexism in Schools. Available online at: https://neu.org.uk/advice/its-just-everywhere-sexism-schools (accessed July 18, 2022).

Nind, M., Boorman, G., and Clarke, G. (2012). Creating spaces to belong: listening to the voice of girls with behavioral, emotional and social difficulties through digital visual and narrative methods. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 16, 643–656. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2010.495790

Ogier, S., and Tutchell, S. (2021). Teaching the Arts in the Primary Curriculum. London: Learning Matters.

Peabody, S. (2021). Decolonizing folklore? Diversifying the fairy tale curriculum. Die Unterrichtspraxis 54, 88–102. doi: 10.1111/tger.12156

Reddy, S. (2018). Diversifying the higher-education curriculum: queering the design and pedagogy. J. Femin. Stud. Rel. 34, 161–169. doi: 10.2979/jfemistudreli.34.1.25

Reynolds, K. (2011). Children's Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1994). The Reader, the Text, the poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Sanders, J. H. III., and Gubes Vaz, T. (2014). Dialogue on queering arts education across the Americas. Studi. Art Educ. 55, 328–341. doi: 10.1080/00393541.2014.11518941

Sparrman, A. (2020). Through the looking-glass: alice and child studies multiple. Childhood 27, 8–24. doi: 10.1177/0907568219885382

Stevens, K. M., and Martell, C. C. (2019). Feminist social studies teachers: the role of teachers' backgrounds and beliefs in shaping gender-equitable practices. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 43, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jssr.2018.02.002

Stromquist, N. P. (2014). Freire, literacy and emancipatory gender learning. Int. Rev. Educ. 60, 545–558. doi: 10.1007/s11159-014-9424-2

Stromquist, N. P. (2015). Women's empowerment and education: linking knowledge transformative action. Eur. J. Educ. 50, 307–324. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12137

Thibodeaux, T. (2017). Tatar, Maria. The classic fairy tales: texts, criticism. Child. Literat. Assoc. Q. 42, 361–363. doi: 10.1353/chq.2017.0038

Zipes, J. (2014). “Introduction: Rediscovering the original tales of the Brothers Grimm,” in The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, ed J. Zipes (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), xix–xliii.

Keywords: gender, identity, equality, literature, art, education, conscious awareness

Citation: Tutchell S and Sharp S (2022) Gendered identity: Reminders of equality through art and fiction. Front. Educ. 7:983760. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.983760

Received: 01 July 2022; Accepted: 26 August 2022;

Published: 11 November 2022.

Edited by:

David Bueno, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Jason DeHart, Appalachian State University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Tutchell and Sharp. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suzy Tutchell, cy50dXRjaGVsbEByZWFkaW5nLmFjLnVr; Stephanie Sharp, cy5zaGFycEByZWFkaW5nLmFjLnVr

Suzy Tutchell

Suzy Tutchell Stephanie Sharp

Stephanie Sharp