- 1Department of Economics Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Universitas Tanjungpura, Pontianak, Indonesia

- 2Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia

Critical thinking is necessary for students because it empowers them to solve problems, especially during the learning stage and in real-life situations within society. Based on this fact, the present study proposes a citizenship project model that aims to enhance the Elementary School Teacher Education Study Program by emphasizing critical thinking among students during the teaching of Civic Education at universities in Indonesia. The research is of the experimental quasi-research type, which comprises two classes: an experimental class and a control class. Both the classes were conducted to compare the effectiveness of the proposed citizenship project learning model. The statistical package for the social sciences was used for data analysis. To attain the required results on the implementation of the citizenship project learning model, there were several stages, including problem identification, problem formulation, information gathering, documenting the process, showcasing the results, and reflective analysis of the model implementation process. The results have revealed a significant improvement in the critical thinking abilities of the students in the experimental class category compared to the control-class category. Thus, it is concluded that the adoption of a citizenship project learning model is appropriate for critical thinking skills' improvement of students taking up citizenship education study programs at universities.

Introduction

The development of critical thinking skills is very essential for every student of higher education today (Kwangmuang et al., 2021). Globally, it has been found that 85% of teachers entail a belief that today's students have limited critical thinking abilities, mostly at the time of entry to university (Jimenez et al., 2021). This development is coupled with the fact that, the world of present is facing rapid transformation in technology and scientific knowledge (Kraus et al., 2021), something that is affecting people from all walks of life, including eroding their love for nationalism and affecting their attachment to nationalistic values (Smith, 1983). This situation is also worsened by the existing learning models on citizenship (Maitles, 2022), which are said to have not fully assisted students in developing critical thinking skills, thereby leading to difficulties in reasoning with the mindset of mature citizenry. This in turn affects their communication skills and leads to difficulties in responding to social phenomena that take place in society (Castellano et al., 2017).

Because of the importance of critical thinking in solving problems related to students' learning, critical thinking cannot be separated from educational institutions (Kim and Choi, 2018), especially from institutions of higher education (Collier and Morgan, 2008), which are empowered to address challenges related to human resource development through the implementation of teaching and learning content. This development in turn influences students' change in mindset toward a positive direction by bringing about a change in their attitudes (Sapriya, 2008). For this reason, when citizenship education is included in the realm of higher education it needs to contribute to the development of critical thinking skills as one of the compulsory subjects being taught to each student at any university in Indonesia, with the aim of achieving a 2045 Golden Indonesia (Malihah, 2015). The main concern of such an educational course would be to create students who are able to instill a sense of nationalism and patriotism, as well as inculcate a sense of responsibility as future citizens who are competitive, intelligent, independent, and are able to defend their homeland, nation, and state (Dirwan, 2018). Based on the above reasons, this paper focuses on the development of the critical thinking ability of student teachers by the lecturers of citizenship education by using a project-based citizenship learning model.

The concept of developing such critical thinking skills has paved the way for designing a Project Citizen model, which has been named a project-based citizenship learning model. This model has a twofold objective. Because it not only emphasizes the development of abilities in the form of mastery of skills alone, but more importantly, it emphasizes being critical in views and at decision-making, intellectually, and in character thinking (CCE, 1998; Budimansyah, 2009; Nusarastriya et al., 2013; Falade et al., 2015; Adha et al., 2018) presented in practice through daily activities. To prepare students to realize the mastery of skills, such as critical thinking skills, positive mentality, and independent personality, a project-based citizenship learning model (Adha et al., 2018) serves as an appropriate problem-based instructional treatment that can lead students to hone their critical thinking skills (Brookfield, 2018).

The project citizen learning model is a strategy and art in the learning process to meet the learning objectives, especially students' critical thinking skills (Susilawati, 2017). The Project Citizen model can develop students' abilities in terms of knowledge, skills, and civic character, as well as shape their democratic attitudes, and hence moral values (Ching Te Lin et al., 2022). In addition, it can encourage student participation as citizens who are trained and prepared to learn to solve problems, both in the educational realms and government circles, as well as in society and family (CCE, 1998; Budimansyah, 2009; Lukitoaji, 2017). The Project Citizen model can also encourage students acquire skillset such as intentional development through change. In fact, people can actively become involved in these changes, which may effectively take place on an ongoing basis (Dharma and Siregar, 2015).

Therefore, the project citizenship model in Civic Education learning must be implemented because it is a major contributor to advancing students' critical thinking skills. This model works in such a way that it attracts or calls students to participate in dealing with social problems within a democratic and constitutional way of thinking in society through a Project Citizen-based learning process (Budimansyah, 2009; Fry and Bentahar, 2013).

This research was conducted at Khairun Ternate University, a state university founded within the Province of North Maluku, Indonesia. Being one of the most favored universities in the region, its leadership ensures that the institution become a center of critical thinking and knowledge development, one of the soft skills required for national growth and development by shaping students and citizenship education students as future leaders. This study sought 1. To determine whether project-based citizenship education lectures can lead to improvement in critical thinking skills among students; 2. To examine students' critical thinking ability before taking up the study of Citizenship Education, we used a project-based citizenship learning model; and 3. To understand the difference in critical thinking ability between students who were taught using the project-based citizenship learning model and those who were taught using conventional models.

Basing on the above-mentioned aspects, this study sought to address and fill the gaps in students' thinking abilities, by sharpening their ways of looking at the varying citizenship challenges faced in the country. The author(s) implemented a project-based learning conceptual model, as it entailed the required aspects in improving students' thinking competences.

Literature review

Citizenship education as a compulsory subject at university

The inclusion of subjects pertaining to Citizenship Education at all levels of education is required to sharpen and transform students into responsible stakeholders in nation building (Gaynor, 2010; Kawalilak and Groen, 2019) of any given country. In Indonesia, Citizenship Education has of recent times attracted the attention of everyone by leading to varying discussions and policies (Marsudi and Sunarso, 2019) on the program and steps for its implementation as a course or subject that promotes democratic values and shapes citizens into responsible persons who think positively and decide wisely.

Citizenship Education is also basically a vehicle for educating citizens to become democratic citizens (Hahn, 1999). The implementation of this type of education program is carried out by carefully designing the material to be delivered from the curriculum so that it can be applied, assessed, and updated for the purposes of the community (Callahan and Obenchain, 2013). This educational effort is believed to be an integral part of the process of transforming society in all aspects of life, whether social, political, economic, cultural, or spiritual.

By law, Citizenship Education is compulsory because it is enshrined in the Indonesian Constitution. According to Law No. 20 of 2003 on the National Education System (Nurdin, 2015), Citizenship Education explicitly refers to the task of education, whereby it should be able to determine the potential of students and be able to change their morals and character for the better (Raihani, 2014). The law explicitly states that the task of education is to improve the behavior of educated people. Changes in behavior and character have the potential to advance the nation and the state at large. Therefore, education must aim to develop the potential for students to become faithful and obedient servants of God, be healthy, knowledgeable, and competent. These abilities must meet three domains: knowledge, affective, and psychomotor abilities.

Philosophical basis for citizenship education

Every science has a philosophical foundation as a scientific root that can be used as the basis of knowledge (Ginzburg, 1934). Likewise, Citizenship Education too has its own foundation, ontologically, epistemologically, and axiologically (Uljens and Ylimaki, 2017). As it is known that Citizenship Education (Civics) developed from the civic concept with a lexical basis based on the word used in ancient Rome, namely, Civicus (Cresshore, 1986; Winataputra, 2001). At that time, Civicus had the meaning of citizens. This term has been adapted especially in Indonesia as a concept called “Citizenship Education.”

Citizenship Education has developed both scientifically and in curricular form, hence, it touches on the broader aspects of sociocultural activities with the nature and various kinds of studies and dimensions (Cresshore, 1986). Furthermore, the epistemological study of Citizenship Education focuses on the topic of “citizenship transmission,” the essence of the first social science study to obtain knowledge believed to be a tradition of self-evident truth. When drawn into learning, Citizenship Education lies at the core of social studies learning (Anderson et al., 1997), which includes studies of scientific disciplines both in practice and concepts called “social studies” (Barr et al., 1978; Soemantri, 2011). As a cross-disciplinary study, Citizenship Education is substantially driven by various types of scholarships, including political, social, and humanities. Although integrated into various studies, Citizenship Education can be held in the school sector, universities, and communities (Winataputra, 2001).

From the description given above, it can be interpreted that the inclusion of Citizenship Education as a scientific area of specialization determines the study of what, how, and for what knowledge is constructed. We have long recognized terms in the study of Educational Philosophy, which include perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, and reconstructionism (Brameld, 1955). The four terms of Educational Philosophy are related to Citizenship Education, among which philosophically Civic Education (Civics) is based on the concept of “reconstructed philosophy of education” which has a suitability to fulfill scholarship in terms of “perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, reconstructionism” (Winataputra, 2001). The philosophy of essentialism looks at educational needs, which is the result of a proof that has been tested and experienced. The foundation is taken through an eclectic state that is philosophically centered on sophisticated knowledge (ideas) and reality (real).

The linkage between these educational philosophies makes this philosophical view sociopolitical in line with the Indonesian human conception, which is still an ideal–conceptual profile that must be realized and fought for continuously (Winataputra and Budimansyah, 2007). Citizenship Education is expected to have an effect on three roles, namely; first, in the role of a curriculum that has a planned concept for educational institutions, both legally at the level of the education unit and outside of official activities; second, having an engagement plan to play an active role in the community in the context of social and cultural interaction; and third, having a role in the treasures of scientific knowledge, both in the sector of concept studies, academic ideas, and studies that have certain objects, systems, and methods for science. Such a role when examined has aspects, namely, the first aspect, the most important aspect is the academic subject as content that brings changes from their learning experience, for example, the standard content of Citizenship Education subjects, which determine scientific studies and determine the development of the study; the second aspect, in terms of scientific studies carried out including classroom action research, so that teachers will always reflect in every lesson they do (Winataputra, 2001).

Critical thinking skills' development through citizenship education

As it is known, critical thinking in solving problems and finding solutions is indispensable to the learning of Civic Education for students as prospective teachers (Ige, 2019). Moreover, at this time, digital students are challenged with a lot of information that can trap them in the flow of incorrect information (hoax); therefore, students must be critical and selective to the information available. To break down the problem of students' critical thinking ability, certainly not apart from educational institutions, especially college institutions, which are the right institutions to address this challenge, namely applying learning through content and touching the realm of thinking skills (Sapriya, 2008; Aboutorabi, 2015; Borden and Holthaus, 2018; Japar, 2018).

One of the supports in critical thinking is hunting assumptions, which is one of the indicators of critical thinking ability in the Brookfield assumption. Critical thinking explores alternatives to decisions, actions, and practices from views mastered in a variety of contexts, as well as engaging in experience and information (Brookfield, 2012). In this case, students are required to master critical thinking, namely, hunting assumptions, checking assumptions, seeing things from different viewpoints, and taking informed actions (Brookfield et al., 2019). These four aspects help them by serving as the bases for critical thinking in a learning process that focuses on uncovering and examining assumptions, exploring alternative perspectives, and taking information-based actions as a result (Brookfield, 2019). Critical thinking is best experienced as a social learning process, which is important to the learning of Civic Education, which is oriented toward society. This critical thinking ability is also necessary for students to participate in political and community life (Banks, 1985; Sapriya, 2008; Budimansyah and Karim, 2009; Setiawan, 2009; Wahab, 2011; Brookfield, 2012). At this critical thinking stage, students can think more systematically and critically, and have high sensitivity to cultural differences, as well as local, national, and global perspectives, with a future orientation (Kalidjernih, 2009; Shaw, 2014; Lilley et al., 2017). One approach can be implemented through education, by honing critical thinking skills during the learning process, to gain a high learning experience to face social problems from various aspects (Raiyn and Tilchin, 2017; Alkhateeb and Milhem, 2020).

From the various opinions given above, the ability to think critically of hunting assumptions is needed in the course of the Civic Education field covering many topics and problems (Cohen, 2010). The implementation of a Project Citizen-based learning model as one of the powerful ways to build an understanding in Civic Education aims to provide learning that focuses on the ability of students to solve problems, so that this provision can benefit them while facing and solving various problems of life.

These abilities are manifested not only in the form of mastery of skills, but more importantly, also by the ability to think critically, mentally, and characteristically (CCE, 1998; Budimansyah, 2009; Nusarastriya et al., 2013; Falade et al., 2015; Adha et al., 2018). To prepare students to realize the mastery of skills, critical thinking skills, and mental and independent character, the Project Citizen learning model is a problem-based instructional treatment that can lead students to cultivate their critical thinking skills.

The Project Citizen learning model is a strategy and art in the learning process so as to meet the learning objectives that need to be achieved, particularly as regards the critical thinking skills of students (Susilawati, 2017). This is because the Project Citizen model is able to develop the knowledge, proficiency, and character of democratic civic that allows and encourages the participation of students as democratic citizens. The said model can also help in dealing with problems that can be learned and trained according to the situation of self-condition of the environment faced by anyone, as many things are learned in terms of education, government, society, and family (CCE, 1998; Budimansyah, 2009; Warren et al., 2013; Lukitoaji, 2017; Bentahar and O'Brien, 2019). The Project Citizen model is also able to encourage the development of change in an intentional manner, so that actively and effectively, the change occurs continuously (Dharma and Siregar, 2015; Marzuki and Basariah, 2017). Therefore, it is important to apply the Project Citizen model to the learning of Civic Education as a major contribution to advancing students' critical thinking skills. This is because the learning model of Project Citizen invites students to participate in dealing with social problems in democracies and constitutional ways of thinking in the community through a learning process based on the project citizenship (Budimansyah, 2009; Anker et al., 2010; Fry and Bentahar, 2013; Romlah and Syobar, 2021).

Thus, the learning model of citizen project lecturers and students can reflect on the studies they found during the course of their studies. The study was conducted by each group that was formed at the beginning of the meeting. Finally, lecturers and students hold joint discussions in the classroom by presenting data and information to create alternative solutions to the urgent problems they had to solve.

Methodology

In this study, a quasi-experimental research method was used. A quasi-experimental research approach is mostly referred to as nonrandomized, pre-post-test intervening research design (Harris et al., 200), which is used across fields of study. In the case of this study, the researchers used control groups and experimental groups but did not randomly segregate (non-random assignment) the participants into the two groups (Creswell, 2017).

In this study, researchers want to see and learn more about the new learning model; therefore, they use two different classes, namely control and experimentation, to compare the classes that use project citizens (experimental) with classes that use the old method (Sukmadinata, 2005). From both classes, researchers can compare the effectiveness of the experimental class learning model with that of the control class model. In addition, researchers will also observe how the results of both experiment and control classes reached high values. The researchers' approach is quantitative. This approach was determined by the researchers because it aimed to statistically test and compare both control and experimental classes. Furthermore, this approach emphasized testing to see an average comparison of the two groups that were statistically the same at the beginning of treatment.

Object and area of the study

This study was conducted at Khairun University in North Maluku Province, Indonesia. The research subjects were undergraduate students of the Elementary School Teacher Education Program and were basically those attending Civic Education courses as their major field of study. The research population comprised of all elementary school teacher Education Study Program students in Semester III totaling 100 of them, consisting of two classes, experimental classes and control classes. Each class consisted of 50 student teachers. The experimental classes of 42 females and 8 male students were experimented with a project-based citizenship learning model. In the control class, there were 44 female students and 6 male students using a conventional learning approach.

Data collection techniques

Data collection comes in various forms (Gray and Bounegru, 2019), which can be either qualitative or quantitative data, comprised of either structured or unstructured data collection instruments or tools (Pitcher et al., 2022). Data in its raw form may have no meaning, but due to the setting up of research targets, most research data are given meaning through interpretation by the authors, just like how the authors used with this study.

This means that data collection can be carried out with the help of written tests (Silvia and Cotter, 2021). So in regard to this research too, the data were obtained through written tests, because this is a way the research chose so as to determine the critical thinking abilities of students, for both the experimental and control classes, before or after the treatment, with the method that had been chosen. This test was administered to students in the form of a detailed questionnaire. The question instrument used in the implementation of this research was a written test sheet that was formulated previously through the validation process by the validator. The hypothesis in this study is H0: there is no difference in hunting assumption ability between the experimental and control classes. H1: There are significant differences in hunting assumption ability between control-class experiments.

Normality test

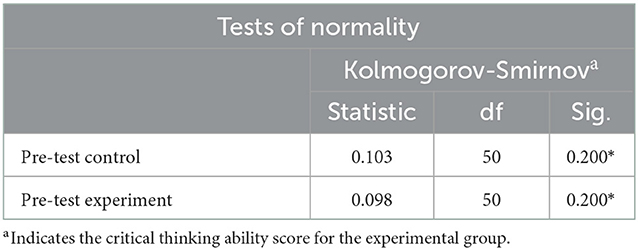

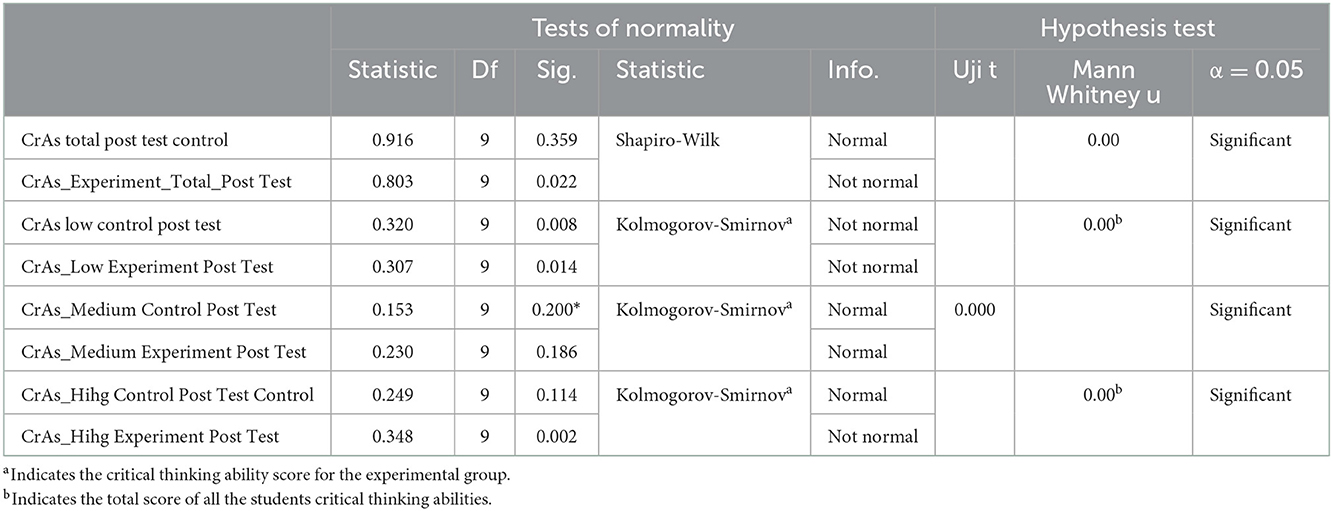

Parametric statistical analyses were used to compare the average experimental and control classes. In the early stages of the test, a prerequisite test was conducted using a normality test, with the following results:

Based on Table 1, the Sig. = 0.200 in the experiment, where G is the group. = 0.200 in the control group. The score is Sig. = 0.200 > 0.05 in both groups. Thus, it can be concluded that normally distributed data displayed a level of significance of = 0.05. A homogeneity test was also performed. = 0.344. This score is >0.05, indicating that the data are homogeneous. After conducting a prerequisite test, a t-test was performed on the Sig results. (2-tailed) = 0.259, with a significance level of a = 0.05.

The score indicates that there are no significant differences between the experimental and control groups, so both groups are eligible to be subject to research. The average similarity between two groups is a measure of the effectiveness of a citizen's project-learning model. There was a significant difference at the final measurement after the intervention.

Results

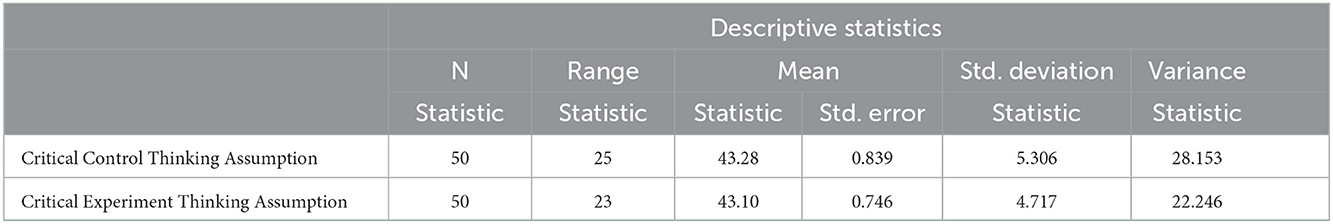

The findings and discussion are the answers to the formulation of the problem, which is the main focus of this study. This section presents the results of this study. Before implementing the lecture process of learning using the project-based citizenship model, the students were first given an initial trial test to establish the extent of their ability to think critically. Based on the initial proficiency tests conducted, the students' ability to think critically revealed no limitations in ability. The results of the students' initial ability tests are illustrated in Table 2.

From the exposure in Table 2, the basic ability score of critical thinking for both the control class and experimentation descriptively obtained an average similarity that is not much different from the ability of early critical thinking of the students.

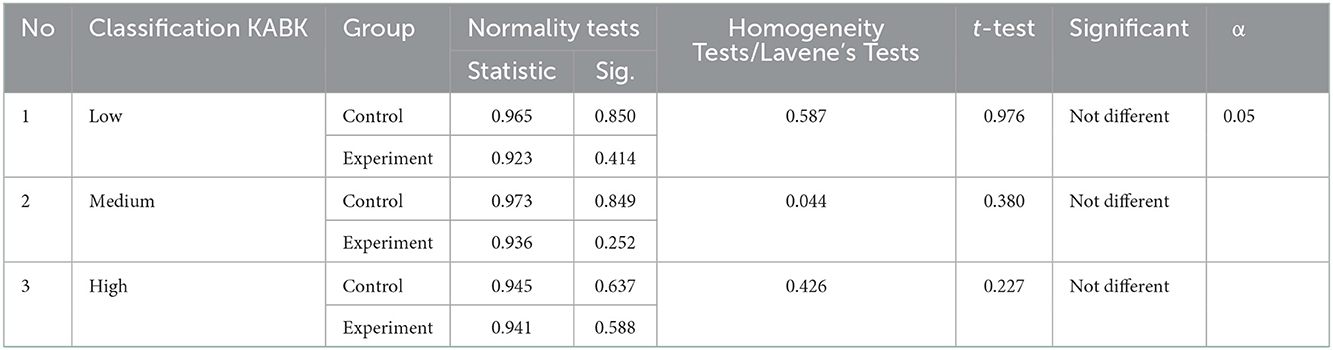

Furthermore, the initial ability to hunt assumptions students also conducted different tests in experimental and control classes using the static test. This was done to determine the difference in students' initial critical thinking ability based on the classification of low, medium, and high categories. The test results are listed in Table 3.

The results of the category wise classification test in Table 3 indicate that the initial ability to display critical thinking skills in the experimental and control classes did not show significant differences. This is illustrated in the classification of the ability based on low, medium, and high categories, which also show no significant differences.

Therefore, it is necessary to implement a learning model that can maximize the ability to think critically by the students, that is: through the Citizen Project model. The Citizen Project model was implemented during the 10 meetings. Step-by-step, learning is underway to implement the learning model. The implementation of this Citizen Project learning model achieved the criteria and gained success in the ability to hunt assumptions for students. This can be seen in the tables that describe in general the classification of the low, medium, and high categories. This exposure resulted from the implementation of the learning model project. An explanation citing the success of the citizenship project-based learning is presented in the following table.

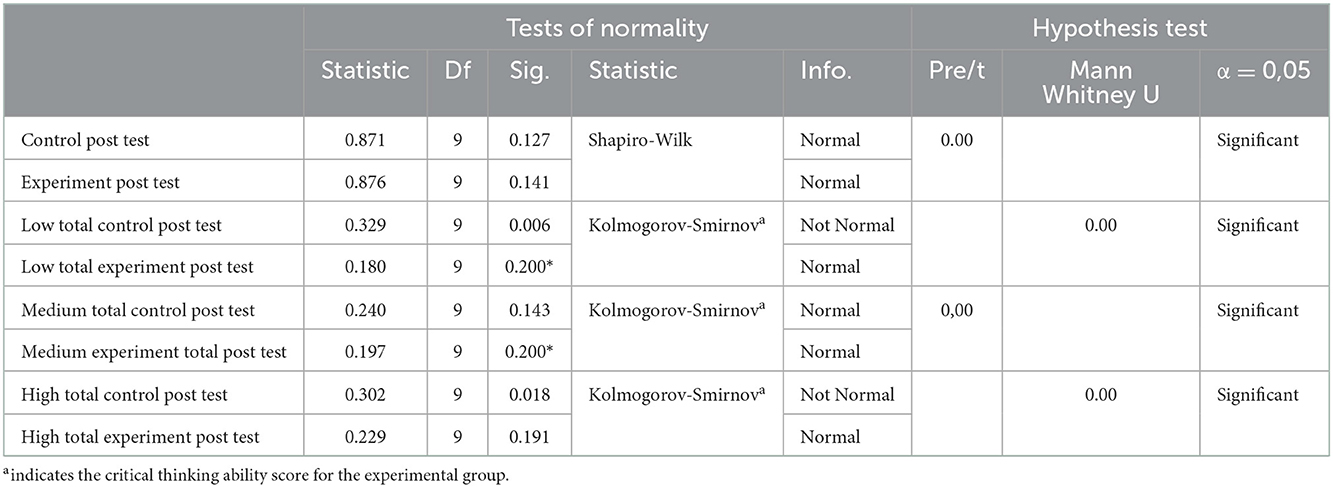

Based on the normality test in Table 4, it can be seen that the total score of overall hunting assumptions of students in both class control and class normal distributed experiments can be calculated and then a t-test conducted. The t-test results showed a sig. (2-tailed) = 0.00 at =0.05, which means that Ha1 is received. Thus, it can be concluded that there are significant differences in critical thinking abilities between the control classes and the experiments.

Then, based on the normality tests in low-category students, the total hunting assumptions were scored in a normally distributed experimental class. However, if the control class is not normally distributed, then a t-test cannot be done for the Mann–Whitney U test. The Mann–Whitney U test results obtained were sig. =0.00 at = 0.05, which means that the Ha1 is received. Thus, it can be concluded that there is a significant difference in the hunting assumption ability of low-category students between experimental and control classes.

Then, for students in the moderate category based on the normality test given in the table, the total score of the hunting assumption's ability of moderate-category students either in the control group or in the normally distributed experimental group is calculated, and then a t-test conducted. The t-test results had a large score. (2-tailed) = 0.00 at =0.05, which means the Ha1 is received. Thus, it can be concluded that there are significant differences in hunting assumption capability in general for students in the moderate categories between the control classes and experiments.

For students in the high category based on the normality test for high-category students, the total hunting assumption's ability score in the normal distribution experiment class was reached but in the normal distribution control class, the t-test could not be performed for the Mann–Whitney U test. The Mann–Whitney U test results obtained were sig. =0.00 at = 0.05, which means that the Ha1 is received. Thus, it can be concluded that there is a significant difference in the hunting assumption ability of high-category students between experimental and control classes.

There are also differences in the ability of students to hunt assumptions after the implementation of the Citizen Project model learning in the low, medium, and high categories. The results are outlined in Table 5.

Based on the normality test in Table 5, we can see the total score of the critical thinking ability of all students in the normally distributed control group. However, if the experimental group is not normally distributed, then a t-test cannot be performed to test the Mann–Whitney U test results which were obtained as sig. =0.00 at = 0.05, which means that H1 is received. Thus, it can be concluded that there was a significant difference in the ability of students' critical thinking between the experimental and control classes.

Then, based on the normality test on the ability of thinking critically among the students in the low category if the total critical thinking skills' ability score in the experimental class and control is not normally distributed, then t-test cannot be conducted to test the results of the Mann–Whitney U test in both the control and experimental classes. The Mann–Whitney U test results obtained were sig. = 0.00 at = 0.05, which means that H1 is received.

Thus, it can be concluded that there was a significant difference in the ability of thinking critically among students in the low category between the experimental and control classes. Then, for the ability of critical thinking, students in the moderate category based on the normality test mentioned in the table can be seen to reach the total score of student critical thinking ability in both class control and class normally distributed experiments. The t-test results had a large score. (2-tailed) = 0.00 at = 0.05 which means that H1 is received.

Thus, it can be concluded that there are significant differences in the ability of critical thinking of the students in the moderate category between the control classes and experiments.

For high-category students, based on normality tests on the ability of critical thinking of the students in the high-category score, the total critical thinking ability is normally distributed, in control classes. However, if the experimental class is not normally distributed, then a t-test cannot be performed to test the Mann–Whitney U test results obtained. = 0.00 at = 0.05, which means that H1 is received.

Thus, it can be concluded that there was a significant difference in students' critical thinking abilities in the high category between the experimental and control classes. To perceive the difference in the development of hunting assumption's ability to conduct an analysis of pre-test and post-test scores, the analysis included the examination of the magnitude of N-Gain in each class, both control and experimentation. The analysis was conducted on both categories based on initial ability.

Based on the table, we can see the difference in improved hunting assumptions between the control classes and experiments that are reviewed from the initial ability. If we analyze the groups based on indicators of critical thinking ability, we can see that in the control group, the improvement of critical thinking skills' ability is almost entirely in the low category, both in the subclass based on the initial ability and on the ability to critical thinking that students are in a low category.

In the experimental class, hunting assumptions increased in the moderate category. There was no increase in the low category, and it was placed in the ability to critical thinking of students. An increase in high-category critical thinking was also not seen. Furthermore, if we analyze the ability to critical thinking based on the initial ability, it can be seen that the control class shows an increase in the ability to critical thinking in the low category. In the experimental class, although the increase was not classified as high, in all classes, critical thinking showed an increase in the moderate category in the experimental class, which was significantly higher compared to the control class on improved critical thinking ability.

Discussion

The ability to think critically by the students has an important element in assuming, identifying thinking critical skills, comparing critical thinking abilities based on students' opinions, and performing actions and movements to change old habits by promoting the application of new habits properly (Brookfield, 2012). A study on the ability to think critically is intended to give students an understanding of building hypotheses or assumptions, seeing from data and facts to be identified, tracing figures and experts to compare, and making movements as a form of application of student work as their ability to critical thinking present day required life skill (Brookfield, 2018; Gonzalez et al., 2022). Thus, the citizen project learning model is suitable for improving students' critical thinking skills through six learning steps. The six steps were identifying problems, formulating or selecting problems, collecting information or data, creating portfolio file documents, displaying studies, and reflecting on the findings discussed together (Budimansyah, 2009; Dewey, 2021). The project citizen learning model is based on strategy “inquiry learning, discovery learning, problem-solving learning, research-oriented learning” (learning through research, learning to find/disclose, learning problem-solving, and learning-based research).

This model is packaged by Dewey, who is called a project citizen. This model is appropriate when applied to Citizenship Education to increase students' awareness and thinking ability, as well as to build smart and good citizen characters (Budimansyah, 2008; Rafzan et al., 2020). Thus, through the process of learning the citizen project model, lectures have combined theoretical and practical studies that allow the readiness of students with their groups to undergo a mature process. In particular, Civic Education courses have a wide scope of studies, with a project citizen learning model able to train students to improve critical thinking skills, especially critical thinking hunting assumptions.

Project citizen-based learning in Civic Education courses to improve critical thinking skills and sharpens the argumentative way of reasoning among students, hence making them obtain good results. The results of the analysis of the influence of learning on the ability to critical thinking based on the learning model of project citizenship learning conclude that: the ability of students to think critically in the experimental class, in general, differs significantly compared to the control class; the ability to think critically of students in the low category in experimental class among students differed significantly compared to the control class; the critical thinking ability of students with moderate categories in experimental class differed significantly compared to the control class; and lastly, the critical thinking ability of students in the high category in experimental class was significantly higher compared to the control class.

Based on the statistical analysis of critical thinking assumptions' ability, it can be concluded that the understanding of the student's capacity to think critically through experimental classes, using project citizen-based learning models to ensure students learn from low to medium, and attain high critical thinking skills has been enhanced by learning steps that lead them to be more active and productive in understanding information and critical opinions. This means that there is uniformity in the acquisition of value in understanding students' opinion through critical arguments, which indicate that the citizen's project model can improve the critical thinking ability of students, gauged through exchange of opinions.

From the description given above, it appears that the learning model of a project-based citizenship education model has a significant impact on students' development of the critical thinking skills' ability. This is because the implementation of citizenship-based project learning provides learning steps based on experience. Such an experience can help students develop their knowledge, skills, and skills (civic knowledge, civic skills, and civic disposition) (Fry and Bentahar, 2013; Fajri et al., 2018).

Conclusively, a project-based citizenship learning model, as a social learning model, has been found to be effective in developing critical thinking skills that impact on all students' competencies. Competency is the ability of students to conduct a given task independently based on the citizenship-based project learning model applied in the course of Civic Education to enhance students' abilities in problem-solving from concept to real-life realization stage (Medina-Jerez et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2017; Yusof et al., 2019). In other words, the project-based model used in this research is expected to contribute to improved students' reasoning capacity while at school and in a real-life situation.

The result is in accordance with Brookfield's (2012, 2018) opinion about the aims and objectives of the student's critical thinking ability, who states that social problems could be solved by making decisions based on hypotheses and critical thinking. Based on a deeper analysis and investigation of the research findings and discussion, the application of the project-based citizenship learning model in the Civics Education course was able to create an effective learning atmosphere in sharpening students' critical thinking skills and motivating them to be good and responsible human beings. This statement is in line with the objectives of the Civic Education course, which emphasizes the process of creating students who are intelligent, have good character and required morals in society (Banks, 1985; Branson, 1994; Budimansyah and Suryadi, 2008; Budimansyah, 2009; Setiawan, 2009). Thus, the results of the study confirmed that the project-based citizenship learning model is not only a proof of the evidence of the improvement in students' critical thinking skills, but the study also notes that the learning model can as well be effective in helping students develop reasoning abilities and good critical thinking abilities which may also help them in solving various issues within society.

Conclusion

Facilitating the growth of critical thinking abilities of a student leads to critical reasoning, hence encouraging productive discussions, which in turn leads to acceptable criticisms and an open exchange of ideas among students to be easily understood, including those ideas based on assumptions and hypotheses. Based on the exposure of the results and discussion of research on the ability to hunt assumptions, students who were engaged in a project-based citizenship learning model obtained better scores for their critical thinking abilities. This implies that such students experience an improvement in their hunting assumption ability compared to students studying through conventional learning. Assembling a project citizen learning model in Civic Education courses can improve students' ability to hunt assumptions. Thus, it can be concluded that Civic Education courses with the application of the learning model project-based citizenship learning model can improve students' critical thinking skills.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by University Administration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aboutorabi, R. (2015). Heidegger, education, nation and race. Policy Fut. Educat. 13, 415–423. doi: 10.1177/1478210315571219

Adha, M. M., Yanzi, H., and Nurmalisa, Y. (2018). The improvement of student intelectual and participatory skill through project citizen model in civic education classroom. Int. J. Pedago. Soc. Stud. 3, 39–50.

Alkhateeb, M. A., and Milhem, O. A. Q. B. (2020). Student's concepts of and approaches to learning and the relationships between them. Cakrawala Pendidikan 39, 620–632. doi: 10.21831/cp.v39i3.33277

Anderson, C., Avery, P. G., Pederson, P. V., Smith, E. S., and Sullivan, J. L. (1997). Divergent perspectives on citizenship education: A Q-method study and survey of social studies teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 34, 333–364. doi: 10.3102/00028312034002333

Anker, A. E., Feeley, T. H., and Kim, H. (2010). Examining the attitude-behavior relationship in prosocial donation domains. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 40, 1293–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00619.x

Banks, J. A. (1985). Teaching Strategies for The Social Studies. Inquiry, Valuing, and Decision-Making. Longman.

Barr, R. D., Barth, J. L., and Shermis, S. S. (1978). The Nature of The Social Studies. Palm Spring: An ETS Pablication.

Bentahar, A., and O'Brien, J. L. (2019). Raising students' awareness of social justice through civic literacy. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 10, 193–218.

Borden, V. M. H., and Holthaus, G. C. (2018). Accounting for student success: academic and stakeholder perspectives that have shaped the discourse on student success in the United States. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 7, 150–173. doi: 10.1163/22125868-12340094

Brameld, T. (1955). Philosophies of Education in Cultural Perspective. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Branson, M. S. (1994). What Does Research on Political Attitudes and Behavior Tell us about the Need for Improving Education for Democracy? A paper delivered to The International Conference on Education for Democracy Serra Retreat, Malibu, California, USA. Available online at: https://www.civiced.org/papers/attitudes.html

Brookfield, S. D. (2012). Teaching for Critical Thinking Tools and Techniques to Help Students Question Their Assumptions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. D. (2018). Race, Teaching Racism, How to Help Students Unmask and Challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Brookfield, S. D. (ed). (2019). Teaching Race: How to Help Students Unmask and Challenge Racism. Jossey-Bass. p. 338.

Brookfield, S. D., Rudolph, J., and Yeo, E. (2019). The power of critical teaching. An interview with Professor Stephen D. Brookfield. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2, 76–90. doi: 10.37074/jalt.2019.2.2.11

Budimansyah, D. (2009). Inovasi Pembelajaran Project Citizen Portofolio. Program Stidi Pedidikan Kewarganegaraan, Sekolah Pascasarjana (Bandung). Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia Jl. Setiabudhi No. 299. Bandung: SPS; UPI.

Budimansyah, D., and Karim, S. (2009). PKn dan Masyarakat Multikultural. Program Studi Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia. Bandung: Aksara Press.

Budimansyah, D., and Suryadi, K. (2008). PKn dan Masyarakat Multikultural. Bandung: UPI Program Studi Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan. Bandung: Prodi PKn SPs UPI.

Callahan, R. M., and Obenchain, K. M. (2013). Bridging worlds in the social studies classroom:teachers' practices and latino immigrant youths' civic and political development. Sociol. Stud. Child. Youth 16, 97–123. doi: 10.1108/S1537-4661(2013)0000016009

Castellano, J. F., Lightle, S., and Baker, B. (2017). A Strategy for Teaching Critical Thinking: The Sellmore Case. Accounting Faculty Publications. Available online at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/acc_fac_pub/73 (accessed October 20, 2022).

Ching Te Lin, C. T., Wang, L. Y., Yang, C. C., Anggara, A. A., and Chen, K. W. (2022). Personality traits and purchase motivation, purchase intention among fitness club members in taiwan: moderating role of emotional sensitivity. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. 20, 80–95. doi: 10.57239/PJLSS-2022-20.1.0010

Cohen, A. (2010). Canadian social studies 44(1) Cohen 17 a theoretical model of four conceptions of civic education. Can. Soc. Stud. 4, 17–28.

Collier, P. J., and Morgan, D. L. (2008). “Is that paper really due today?”: differences in first-generation and traditional college students' understandings of faculty expectations. Higher Educ. 55, 425–446. doi: 10.1007/s10734-007-9065-5

Creswell, J. W. (2017). Research Design, Approach, Method, Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed (Edisi Ke 4). Learning Library. New York, NY: Sage Publications.

Dewey, J. (2021). “The Influence of Darwinism on Philosophy: (1909),” in America's Public Philosopher: Essays on Social Justice, Economics, Education, and the Future of Democracy, eds E. T. Weber (Columbia University Press), 237–248.

Dharma, S., and Siregar, R. (2015). Internalisasi Karakter melalui Model Project Citizen pada Pembelajaran Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan. Jupiis: Jurnal Pendidikan Ilmu-Ilmu Sosial. doi: 10.24114/jupiis.v6i2.2293

Dirwan, A. (2018). Improving nationalism through civic education among indonesian students (July 31, 2018). OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Develop. 11, 43–58.

Fajri, M., Marfu'ah, N., and Artanti, L. O. (2018). Aktivitas Antifungi Daun Ketepeng Cina (Cassia Alata L.) Fraksi Etanol, N- heksan dan Kloroform Terhadap Jamur Microsporium canis. Pharmasipha 2, 1–8. doi: 10.21111/pharmasipha.v2i1.2134

Falade, D., Adedayo, A., and Adeniyi, B. (2015). Civic education in nigeria's one hundred years of existence: problems and prospects. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 6, 113.

Fry, S. W., and Bentahar, A. (2013). Student attitudes towards and impressions of project citizen. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 4, 1–23. Available online at: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1120&context=cifs_facpubs

Gaynor, N. (2010). Between citizenship and clientship: the politics of participatory governance in Malawi. J. South. Afr. Stud. 36, 801–816. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2010.527637

Ginzburg, B. (1934). Probability and the philosophical foundations of scientific knowledge. Philos. Rev. 43, 258–278. doi: 10.2307/2179702

Gonzalez, H. C., Hsiao, E.-L., Dees, D. C., Noviello, S. R., and Gerber, B. L. (2022). Promoting critical thinking through an evidence-based skills fair intervention. J. Res. Innov. Teachi. Learn. 15, 41–54. doi: 10.1108/JRIT-08-2020-0041

Gray, J., and Bounegru, L. (2019). “What a difference a dataset makes: Data journalism and/as data activism,” in Data in Society: Challenging Statistics in an Age of Globalisation, 1st Edn, eds J. Evans, S. Ruane, and H. Southall (Bristol University Press), 365–374. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvmd84wn.42

Hahn, C. L. (1999). Citizenship education: an empirical study of policy, practices and outcomes. Oxford Rev. Educ. 25, 231–250. doi: 10.1080/030549899104233

Ige, O. (2019). Using action learning, concept-mapping, and value clarification to improve students' attainment in ict concepts in social studies: the case of rural learning ecologies. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 10, 301–322. doi: 10.21125/inted.2018.0260

Japar, M. (2018). The improvement of Indonesia students ‘engagement in civic education through case-based learning'. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 9, 27–44.

Jimenez, J. M., Lopez, M., Castro, M. J., Martin-Gil, B., Cao, M. J., and Fernandez-Castro, M. (2021). Development of critical thinking skills of undergraduate students throughout the 4 years of nursing degree at a public university in Spain: a descriptive study. BMJ Open 11, e049950. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049950

Kalidjernih, F. K. (2009). Globalisasi dan Kewarganegaraan. Acta Civicus Jurnal Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan. 2.

Kawalilak, C., and Groen, J. (2019). Dialogue and reflection-perspectives from two adult educators. Reflect. Pract. 20, 777–789. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2019.168596

Kim, M., and Choi, D. (2018). Development of youth digital citizenship scale and implication for educational setting. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 21, 155–171.

Kraus, S., Jones, P., Kailer, N., Weinmann, A., Chaparro-Banegas, N., and Roig-Tierno, N. (2021). Digital transformation: an overview of the current state of the art of research. SAGE Open. doi: 10.1177/21582440211047576

Kwangmuang, P., Jarutkamolpong, S., Sangboonraung, W., and Daungtod, S. (2021). The development of learning innovation to enhance higher order thinking skills for students in Thailand junior high schools. Heliyon 7, e07309. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07309

Lilley, K., Barker, M., and Harris, N. (2017). The global citizen conceptualized: accommodating ambiguity. J. Stud. Int. Edu. 21, 6–21. doi: 10.1177/1028315316637354

Lukitoaji, B. D. (2017). Pembinaan Civic Disposition Melalui Model Pembelajaran Project Citizen Dalam Mata Kuliah Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan 2 Untuk Menumbuhkan Nilai Moral Mahasiswa Prodi Pgsd Fkip Upy. Jurnal Moral Kemasyarakatan. doi: 10.21067/jmk.v2i2.2172

Maitles, H. (2022). What Type of Citizenship Education; What Type of Citizen? Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/what-type-citizenship-education-what-type-citizen (accessed January 15, 2022).

Malihah, E. (2015). An ideal Indonesian in an increasingly competitive world: Personal character and values required to realise a projected 2045 Golden Indonesia. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 14, 148–156. doi: 10.1177/2047173415597143

Marsudi, K., and Sunarso, S. (2019). Contents analysis of the pancasila education and citizenship students' book for high school curriculum 2013. KnE Social Sci. 3, 447–459. doi: 10.18502/kss.v3i17.4670

Marzuki and Basariah. (2017). The influence of problem-based learning and project citizen model in the civic education learning on student's critical thinking ability and self discipline. Cakrawala Pendidikan 3, 43.

Medina-Jerez, W., Bryant, C., and Green, C. (2010). Project citizen: students practice democratic principles while conducting community projects. Sci. Scope. 33, 71–75. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43184007

Mitchell, N., Triska, M., Liberatore, A., Ashcroft, L., Weatherill, R., and Longnecker, N. (2017). Benefits and challenges of incorporating citizen science into university education. PLoS ONE 12, e0186285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186285

Nurdin, E. S. (2015). The policies on civic education in developing national character in Indonesia. Int. Educ. Stud. doi: 10.5539/ies.v8n8p199

Nusarastriya, Y. H., Sapriya, W., and Budimansyah, D. (2013). Pengembangan berpikir kritis dalam pembelajaran pendidikan kewarganegaraan menggunakan project citizen. Jurnal Cakrawala Pendidikan 3, 444–449. doi: 10.21831/cp.v3i3.1631

Pitcher, B. D., Ravid, D. M., Mancarella, P. J., and Behrend, T. S. (2022). Social learning dynamics influence performance and career self-efficacy in career-oriented educational virtual environments. PLoS ONE. 17, e0273788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273788

Rafzan, R., Lazzavietamsi, F. A., and Ito, A. I. (2020). Civic competence pembelajaran pendidikan kewarganegaraan di SMA Negeri 2 Sungai Penuh. Jurnal Rontal Keilmuan PKn 6, 1–2.

Raihani (2014). Creating a culture of religious tolerance in an Indonesian school. South East Asia Res. 22, 541–560. doi: 10.5367/sear.2014.0234

Raiyn, J., and Tilchin, O. (2017). A model for assessing the development of hot skills in students. Am. J. Educ. Res. 5, 184–188. doi: 10.12691/education-5-2-12

Romlah, O. Y., and Syobar, K. (2021). Project citizen model to develop student's pro-social awareness. Jurnal Civics 18, 127–137. doi: 10.21831/jc.v18i1.37982

Setiawan, D. (2009). Paradigama pendidikan kewarganegaraan demokratis di Era Global. Acta Civicus. 2.

Shaw, R. D. (2014). How critical is critical thinking? Music Edu. J. 101, 65–70. doi: 10.1177/0027432114544376

Silvia, P. J., and Cotter, K. N. (2021). “Designing self-report surveys,” in Researching Daily Life: A Guide to Experience Sampling and Daily Diary Methods, eds P. J. Silvia and K. N. Cotter (American Psychological Association), 35–51. doi: 10.1037/0000236-003

Smith, A. D. (1983). Nationalism and classical social theory. Br. J. Sociol. 34, 19–38. doi: 10.2307/590606

Soemantri, B. (2011). “The Making of Innovative Human Resources”: Makalah Seminar” dalam rangka dies natalis UKSW ke 55.

Susilawati, E. (2017). “Modeling learning strategy for students with competitive behavior and its impact on civic education learning achievement,” in Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICELTICs), 841–848. Available online at: http://www.jurnal.unsyiah.ac.id

Uljens, M., and Ylimaki, R. M. (2017). “Non-affirmative theory of education as a foundation for curriculum studies, didaktik and educational leadership,” in Bridging Educational Leadership, Curriculum Theory and Didaktik. Educational Governance Research, Vol. 5, eds M. Uljens and R. Ylimaki (Cham: Springer).

Wahab, A. A. (2011). Politik Pendidikan dan Pendidikan Politik: Model Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan Indonesia Menuju Warganegara Global, Pidato Pengukuhan Guru. Bandung: Alfabeta.

Warren, S. J., Wakefield, J. S., and Mills, L. A. (2013). “Learning and teaching as communicative actions: Transmedia storytelling,” in Cutting-Edge Technologies in Higher Education, Vol. 6 (Emerald Group Publishing Limited).

Winataputra, U. S. (2001). Jati diri Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan Sebagai Wahana Sistemik Pendidikan Demokrasi (Suatu Kajian Konseptual dan Konteks Pendidikan IPS). Disertasi (tidak dipublikasikan). Bandung: Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia.

Winataputra, U. S., and Budimansyah, D. (2007). Civic Education: Konteks Landasan, Bahan Ajar, dan Kultur Kelas. Bandung: Sekolah Pascasarjana.

Keywords: citizenship education, citizenship learning project model, critical thinking skills, elementary education, teacher preparation, university curriculum, university education

Citation: Witarsa and Muhammad S (2023) Critical thinking as a necessity for social science students capacity development: How it can be strengthened through project based learning at university. Front. Educ. 7:983292. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.983292

Received: 01 July 2022; Accepted: 26 September 2022;

Published: 09 January 2023.

Edited by:

Meryem Yilmaz Soylu, Georgia Institute of Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Milan Kubiatko, J. E. Purkyne University, CzechiaDasim Budimansyah Syah, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Indonesia

Copyright © 2023 Witarsa and Muhammad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Syahril Muhammad,  c3N5YWhyaWxtNEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

c3N5YWhyaWxtNEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Witarsa1

Witarsa1 Syahril Muhammad

Syahril Muhammad