- Department of Educational Psychology, Leadership, and Counseling, College of Education, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States

Crisis leadership in higher education has received scholarly attention before COVID-19, yet found itself even more in the focus of global leadership research since 2020. This article employs the theoretical framework of Feminist Educational Leadership (FEL) to better understand the crisis leadership of five women university presidents from three different continents and five different countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through content analysis, the researchers identified themes related to the four components of FEL (concerns for social justice and equity for all stakeholders, empowerment of all stakeholders, establishment of a sentiment of caring, and fighting existing injustices) in the presidents’ qualitative interviews for a larger project on university presidential leadership during COVID-19. The findings show that women university presidents employ FEL in order to successfully lead their institutions through crises.

Introduction

“Something might be interesting to look at if there were differences in women presidents and male presidents. Because I do think we are expected– have different expectations of the women presidents. But we have a group of women presidents that are in fact much more held accountable for students’ mental health issues than some of our male colleagues that keep coming up, right?” (President Mediterranean).

The metaphor of the opportunity within every crisis may be overused at this point, yet it cannot be denied that COVID-19 has provided and continues to provide a never-before seen opportunity to examine educational leadership in various national and global contexts (Marshall J. et al., 2020). The literary corpus on university presidents as leaders during COVID-19 is small, but growing with some studies focusing on specific national backgrounds (Dumulescu and Muţiu, 2021; Schiffecker et al., 2022), others on general leadership mechanics (Fernandez and Shaw, 2020; Strielkowski and Wang, 2020; Antonopoulou et al., 2021; McNaughtan et al., 2022) or specific areas within presidential leadership that have become relevant during a global pandemic. For example, the transition to online learning (Almaiah et al., 2020; Basilaia et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2020; Wrighton and Lawrence, 2020) and crisis communication (Hussain, 2014; Gigliotti, 2019; McNaughtan and McNaughtan, 2019; Thelen and Robinson, 2019).

COVID-19 has without a doubt affected all areas of modern life, university leadership being just one example of people having to adjust to what is often referred to as an ever changing “new normal” (Raghavan et al., 2021, p. 1). With most existent literature on university presidents’ leadership during COVID-19 either focusing on men or remaining gender-neutral, some of the nuances that occur for women presidents who engage with leadership in different contexts are missed (McNaughtan et al., 2022). A novel crisis like this has put the understanding of what constitutes good leaders under extreme scrutiny. Political, economic and other world leaders are being compared against each other and it is the women leaders that seem to be continuously outperforming their male colleagues (Taub, 2020). With women still being highly underrepresented, not only but also, in educational leadership roles, ambivalence toward women is often reflected in organizational practices, and also in the underlying structures (Ely and Rhode, 2010). This ambivalence creates leadership environments where “Women who conform to traditional feminine stereotypes are often liked but not respected” and “women who adopt more masculine traits are often respected but not liked” (p. 385).

Women university presidents, especially women of color, globally remain underrepresented compared to their white, male counterparts (Townsend, 2020). Even when in leadership positions, women HEI leaders still find themselves in what is a traditionally male-dominated environment (Thompson-Adams, 2012; Parker, 2015) in which they face a multitude of challenges. Rather than assigning female or male connotations to certain leadership traits, women’s leadership needs to be explored in its entirety through a feminist lens. By employing the theoretical lens of Feminist Educational Leadership (FEL) to an examination of the ways in which women university presidents in different national contexts navigate a global crisis and successfully lead their institutions, important insights into the importance and practice of equity, social justice, and empowerment of all stakeholders can be gained. The research question guiding this study is hence: How does the crisis leadership of women university presidents during the COVID-19 pandemic reflect characteristics of feminist educational leadership?

Literature review

While first media mentions of a novel and particularly transmittable virus started circulating around the globe at the end of 2019 (World Health Organization, 2020; Taylor, 2021), it wasn’t until 2020 that HEIs in Asia, Europe and the United States started taking measures to protect their campus communities and “flatten the curve” (Marsicano et al., 2020). Some of those measures included the cancelation of face-to-face classes, evacuations of campus buildings and facilities, as well as a general hold on all in-person events (Spradley, 2020). HEIs and their leadership relied mainly on information from contagious disease experts and directives from leaders around the world, as they found themselves faced with an equally unpreceded and unpredictable crisis (Chronicle of Higher Education [CHE], 2020; New York Times [NYT], 2020; International Association of Universities [IAU], 2021; Smalley, 2021). With the world struggling to respond to the surge in COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and COVID-related deaths, the United States simultaneously found itself amidst a long-brewing escalation of racial unrests and a call for racial equity. HEIs around the world, with the presidents as the heads of the administrative leadership, carried the intellectual and moral responsibility of responding to these crises (Griggs and Thouin, 2021). In this study, we frame our analyses using the existent literature focusing on leadership in crisis generally, Women’s leadership in higher education during crisis, and the Feminist Educational Leadership Framework.

Leadership during crisis

Competent and efficient leadership constitutes a crucial element of successful crisis leadership, no matter what crisis is faced. COVID-19, however, presented leadership around the globe with never-before-seen challenges and restrictions of a global pandemic that significantly changed the ways in which humans act and interact in their personal and professional environments (Bellis et al., 2022). When a novel crisis like this shifts leadership priorities, leadership, too, has to change and adapt to what has been referred to as the constantly evolving “new normal.” In higher education, this includes for example a shift from a focus on recruitment and fundraising efforts to a focus on support and safety of the campus communities as well as institutional survival (McNaughtan et al., 2022). The Pulse surveys initiated in April of 2020 by the U.S. American Council on Education (ACE) provided monthly overviews of “presidents” insights and experiences with COVID-19 in the United States and its effects on their institutions and the larger higher education landscape” (American Council on Education [ACE], 2020, p.1). The results painted a highly volatile picture: University presidents had to switch between priorities and quickly adapt to new conditions. The International Association of University Presidents (IAUP) paints a more international picture in their International Association of University Presidents (IAUP) (2020). With representation from HEI leadership from all five continents, the survey highlights the shifting priorities at the onset of the pandemic and the reliance on government officials in both the health and education sectors. Two surveys sent out by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) echoed this constant flux of priorities and contexts. The initial focus on “hunker[ing] down” and “weather[ing] the storm” by laying off administrative staff, implementing hiring freezes, and reexamining operational processes to identify efficiencies” (American Association of Colleges and Universities [AAC&U], 2020, p.3) was later replaced by a “a palpable shift in the national consciousness with regard to racial discrimination” (American Association of Colleges and Universities [AAC&U], 2020, p.5). This consciousness of racial inequities and its repercussions found itself reflected in the global discourse (Walker et al., 2021). The need for leaders that possess the traits of sensitivity and empathy increases in times of complex crises that include racial and socio-political components (Tevis, 2021). This in combination with a much needed evolution of both the role and style of effective crisis leadership (McNaughtan et al., 2019) paves the way for research to closer examine women’s leadership during crises.

Women’s leadership in global higher education

Leadership as a social practice does not exist independently from socio-economic and cultural environments, sparking a scholarly interest in the ways leaders around the world guide their communities in these dynamic contexts (Sperandio, 2010). Scholars have identified leadership and its practices as embedded in, and specific to cultural contexts (Hofstede, 2001; Branzei, 2002; Dorfman and House, 2004; Shah, 2021). For example, “[w]omen in leadership may face multiple barriers in societies that portray leadership as a male-dominated sphere” (Shah, 2021, p. 1). Women’s leadership in particular has moved in the focus of comparative research, as movements of gender equality remain a goal rather than a lived reality. Women leaders have often been pointed out to have positive effects on the organizations they lead (Noland et al., 2016; Zhou, 2020). However, existent scholarly literature is still heavily North America-centric and fails to include other national contexts like Asian higher education (Maheshwari et al., 2021). This “somewhat patchy” (Shepherd, 2017, p. 83) state of the literature on women’s leadership in the field of higher education is in itself potentially indicative of a problem that needs to be addressed (Morley, 2013).

Gender inequalities in leadership in various professional fields have been pointed out by scholars in many different national contexts (Xiang et al., 2017; Burkinshaw et al., 2018; Maheshwari et al., 2021). While women lead in terms of degree attainment and educational achievements (Fitzgerald, 2013), this does not translate into equally high percentages in leadership roles post-graduation. The problem is arguably not a lack in women’s talent, but rather a failure to acknowledge and maximize it (Shepherd, 2017). Shepherd (2017) presents a potential three-fold reason for this shortcoming based on their study on the appointment of women leaders at United Kingdom HEIs. Women tend to be less geographically mobile, are faced with HEIs as conservative and risk-avoidant organizations, and are disadvantaged by tendencies of homosociability (Northouse, 2021). Traditional gender roles, while slowly changing in some countries, still tie women closer to the household and family life in many societies around the world (Farre and Ortega, 2021). This results in women still being less mobile in their career choices and range of attainable positions. Additionally, HEIs, in their attempt to reduce the risk of selecting a non-ideal candidate, often rely on their past experience, which often is a white, male leader (Shepherd, 2017). Homosociability, finally, refers to groups’ tendency to lean toward keeping homogenous members (and leaders), which results in a disadvantage for women leaders who diverge from the leadership norm (Coleman, 2012).

According to an article published by Times Higher Education based on World University Rankings data collected in 2021, the percentage of worldwide top-ranked HEIs lead by women is at an all-time high with 20% (Times Higher Education, 2020). While this number is promising, the article also points out that a continuous increase of women in higher education leadership is far from guaranteed. Rankings editor at Times Higher Education Ellie Bothwell states that “the pace of change has to improve” (para. 11). This rings especially true since higher education’s leadership choices can influence society as a whole and take important steps toward gender equality (Teague, 2015).

With research on university presidential leadership throughout the COVID-19 pandemic still emerging, women presidents in particular represent a blind spot in the literary corpus with very few studies specifically looking at the ways women presidents lead their campus communities through this global crisis. This is particularly pressing as women tend to be hit the hardest during times of crises, given their disproportional childcare and household responsibilities in addition to often full time work commitments (Northouse, 2021). Reed and Disbrow (2020) found in their exploratory study of risk mitigation messages from United States women university presidents that the women campus leaders showed “a respect for shared governance and collaboration,” helping “to distribute responsibility and accountability” (p. 16). Being vulnerable and authentic, qualities having been identified as crucial in creating organization trust (Brown, 2005), were displayed by the women presidents throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Other studies examining women’s leadership in times of crisis have highlighted that women may be better suited to lead through various crises (Eagly and Heilman, 2016; Gedro et al., 2020). What this successful female educational leadership during crises could look like, however, remains vastly unexplored.

Feminist educational leadership framework

The theoretical framework informing this study is Feminist Educational Leadership (FEL) which allows for an examination of leadership in educational contexts through a feminist lens. Contemporary educational leadership has been examined through various critical feminist lenses, highlighting the role of feminist theories to better understand change and the need for social justice in the field of education (Fuller, 2021; Wilkinson, 2021). Blackmore (2013) talks about the need for “refocusing the feminist gaze away from numerical representation of women in leadership to the social relations of gender and power locally, nationally and internationally” (p. 139). Rather than merely count the women in leadership positions, critical feminist perspectives dive deeper in the analysis and understanding of how women lead, providing valuable insights not only into women’s leadership, but leadership in general. Assuming or looking for gender-related traits and styles of leadership is a slippery slope (Northouse, 2021) and makes research vulnerable to the pitfalls of bias and stereotypes. Hence, FEL is not based on a gendered understanding of leadership, but rather analyses leadership as a social practice through a feminist lens. Barton (2006) emphasizes that “feminist educational leadership includes, but goes beyond, being woman centered and embraces a wider political agenda that is anti-racist as well as anti-sexist” (para. 11). Seeing how FEL is embedded not only in gender, but more broadly in issues around social justice, it lends itself as a useful lens through which to examine the ways in which women university presidents around the world lead their institutions through unpreceded crises.

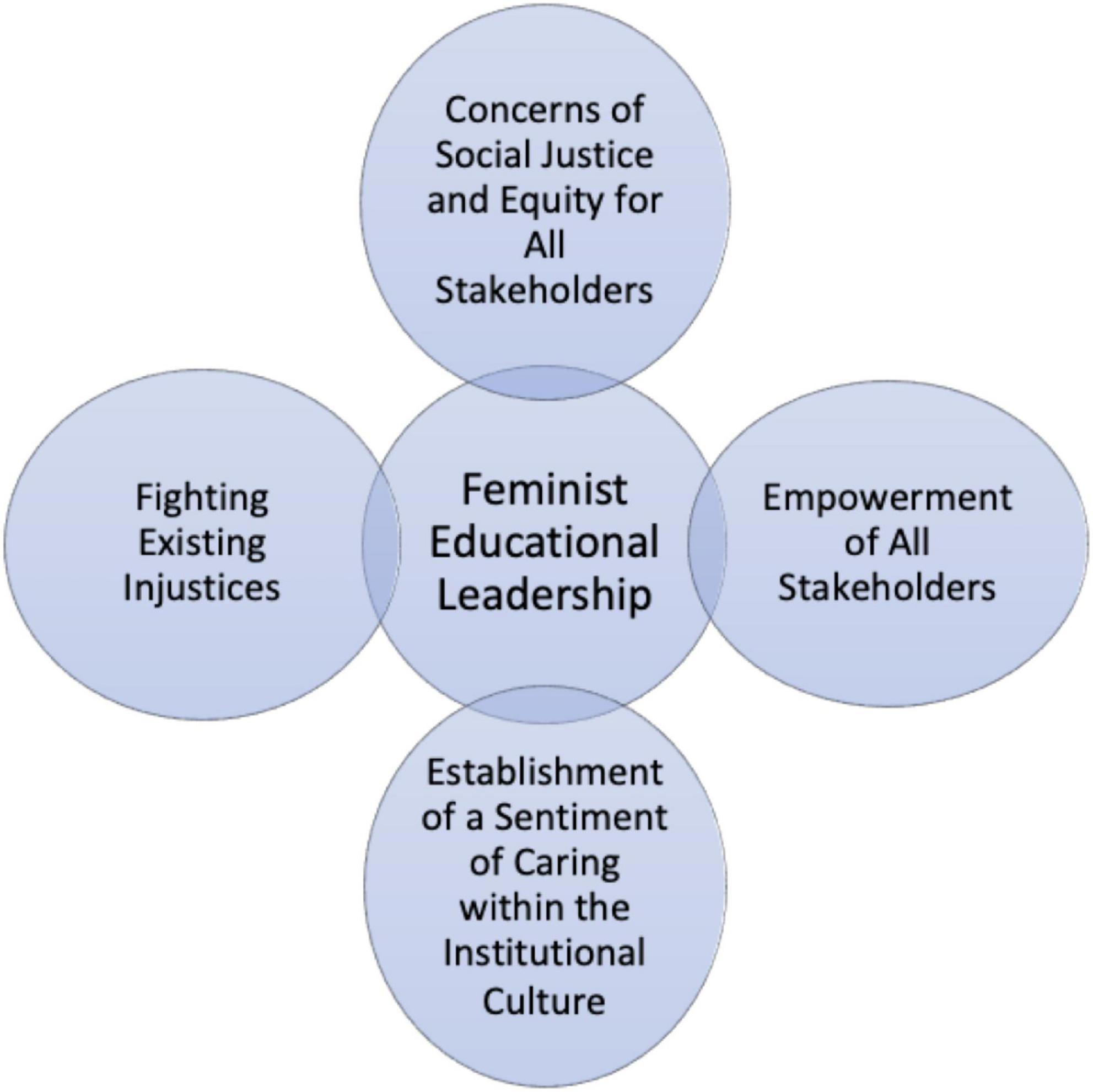

Strachan (1999a) conducted interviews with 13 secondary school principals in New Zealand, allowing the author to identify four defining aspects of feminist educational leadership. The theoretical framework of FEL merging the four aspects will guide this study’s data analysis. The following Figure 1 illustrates those four aspects or main components of FEL as identified by Strachan (1999a,b).

Figure 1. Feminist educational leadership. Visualized from Strachan (1999a,b).

Concerns of social justice and equity for all stakeholders

This element of FEL is based on the great responsibility HEIs and their leadership bear when it comes to promoting democracy, equity, and social justice both in and outside of the context of crises (Shultz and Viczko, 2016; Harkavy et al., 2020; Pearson and Reddy, 2021). Presidents as the heads of institutional leadership are expected to represent the institution’s values and ideals in their communication, actions, and overall leadership (Liu et al., 2020; Coates et al., 2021). At the same time, their leadership spans like an umbrella over the HEI in its totality, including all stakeholders and their wants and needs. Crises like the global COVID-19 pandemic and rising concerns for social justice and equity add responsibility to HEI leaders’ metaphorical plates, making an understanding of those concerns an essential aspect of successful leadership.

The focus on social justice and equity echoed in FEL has been pointed out to “encompass a wider emancipatory agenda, including issues of race, class, sexuality and differing abilities” (Strachan, 1999b, p. 121) rather than being limited to the feminist space. With feminism having been critiqued to have a blind spot for non-gender related marginalities like for example economic status and race (Ortega, 2006; Alexander-Floyd, 2010; Moon and Holling, 2020), FEL takes a conscious step toward acknowledging the need for social justice and equity for all stakeholders. The overarching concept of inclusive leadership as an emphasis on the shared identity of all stakeholders as part of the organization (Northouse, 2021) is expanded upon in FEL by adding an emphasized awareness of the different positionalities of the stakeholders when it comes to issues of access and equity.

Fighting existing injustices

Northouse (2021) describes the transformational approach to leadership as a form of leadership that focuses on how “leaders can initiate, develop, and carry out significant changes in organizations” (p. 201). Inherent to the concept of transformational leadership is the desire to eliminate inequalities in one’s organization and the actions to bring this desire to practical implementation. Identifying and challenging any hegemonic practices supporting and sustaining inequalities is not only on the agenda of feminism (Matthews, 1996; Strachan, 1999b), but also an important aspect of higher education leadership (Dorfman, 2005; Marshall C. et al., 2020; Samier, 2021). Afterall, “counter-hegemonic (i.e., emancipatory) work is educational work” (Strachan, 1999b, p. 122) and constitutes an important aspect of educational leadership. FEL does not limit itself no issues exclusively around gender and sex related discrimination but rather employs the critical feminist lens to uncover and fight social injustices in whatever area they appear.

Empowerment of all stakeholders

The role educational leadership plays in empowering various stakeholders has been discussed in the literature (Taysum and Arar, 2018; Longmuir, 2020; Wanjiku et al., 2020) and rings true for leadership during and outside of crises. Inclusive empowerment with the goal of achieving equitable conditions (Doten-Snitker et al., 2021) has moved into the focus of leadership studies and the call for social justice across disciplines. Leaders as sources of empowerment and mentorship not only hold benefits to the stakeholders, but ultimately have been proven to increase organizational performance (Peyton and Ross, 2022). The concept of emancipatory leadership as the stepping back of the leaders in decision-making processes and a power shift from leaders to the stakeholders has been identified as useful in the field of education (Corson, 2000; Grundy, 2017). FEL is inherently emancipatory (Strachan, 1999b), containing both critical reflection and the enactment of change.

Establishment of a sentiment of caring within the institutional culture

For a long time the concept of care and caring has been associated with a barrier and challenge for women entering leadership spaces that were perceived to be male dominated (Acker, 2012; Burkinshaw, 2015). Whether caring meant increased family responsibilities or a tendency to be more emotional, women in leadership positions were often forced to prove their competency as leaders by “not caring as much” (Grummell et al., 2009). Recently, however, the cultivation of a culture of care that supports all stakeholders and provides an environment that encourages growth, well-being, and security even in turbulent times has been promoted in higher education (Kezar, 2014; Nugroho et al., 2021).

The FEL framework is especially suitable for the analysis of women’s presidential leadership during crises because it centers around beliefs, values, and attitudes of women leaders (Glazer, 1991) without reducing women’s leadership to those abstract concepts. Critical issues around race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, and many more are encompassed in this theoretical approach, making it inherently “anti-racist as well as anti-sexist” (Strachan, 1999a, p. 310). While other feminist theories often remain “stuck” on the theoretical level, FEL embraces the practical application as direct reflection in leadership practices (Blackmore, 1996). Instead of ascribing leadership traits to specific gender categories, FEL aims at trying to encapsulate how gendered leadership experiences have been shaped by a variety of -isms while at the same time striving to effect positive change (Clover et al., 2017).

Materials and methods

The sample for this study is a subsample of a larger project focused on an international comparison of presidential leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the larger project we interviewed presidents to better understand the experiences of leaders in higher education from across the world as they engaged in a shared crisis, COVID-19. All presidents were from a large national university and were one of, if not the main decision maker for their institution. We employed a purposeful sampling technique where each member of our research team identified national universities from one to three countries resulting in an initial list of 85 university presidents in 15 different countries.

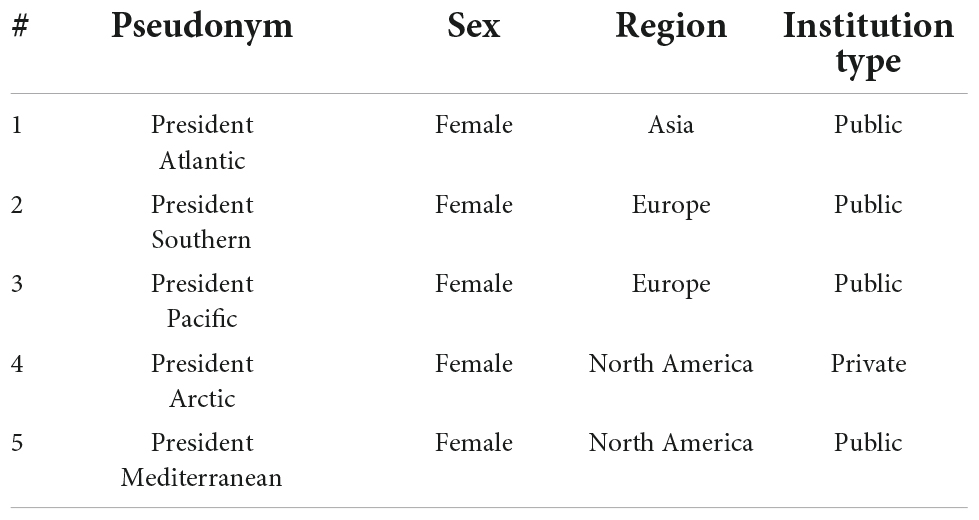

From the initial list 15 presidents accepted the invitation to be interviewed via Zoom following the advice of McClure and McNaughtan (2021). Presidents were from 8 different countries with 1 to 36 years of past experience in the presidency. Of the 15 total respondents, 5 were women and they are the sample for this study. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants, their pseudonyms, institutional region as well as the institution type.

Data analysis

The overarching project did not focus on questions related to gender, so an analytical approach that accounts for that was needed. We employed a comparative case study method to allow for “flexibility to incorporate multiple perspectives, data collection tools, and interpretive strategies” (Blanco Ramírez, 2016, p. 19). This approach allowed us to dissect and discern the perspectives of the presidents beyond their surface meaning and helped us to have “an in-depth analysis of a case” which was critical when we employed FEL (Creswell and Creswell, 2017, p. 14), even when considering different cultural contexts.

We coded the interviews for this study utilizing a content analysis approach which was selected because of its focus on understanding respondents’ perspectives in a naturalistic, or context driven paradigm (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005; Klenke, 2016). Given that some interviews were conducted in the president’s native tongue and others in English, the research team each reviewed the transcripts of presidents whose native language was not English to ensure accuracy of translation. The coding process employed was Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) three-step approach to coding qualitative data: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. During the open coding phase, we focused on the larger project centered on the presidents’ role and experience leading during COVID-19. Following the initial coding, we engaged in axial coding where we sought to discern how the presidents’ responses were connected to the FEL framework which resulted in a higher level of thought (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Saturation was reached during the final phase of coding and the research team identified the most salient quotes to highlight the experiences of the presidents.

Findings

The emergent themes from the interviews provided insights into the ways in which women university leaders employed elements of FEL in order to successfully guide their institutions through crises. The presidents’ perspectives aligned with the four tenets of the FEL, which is why the findings are divided into four sections, following Strachan’s (1999a,b) framework of FEL.

Concerns of social justice and equity

All five presidents brought up their desire to establish social justice and an equitable environment on their campuses and beyond. President Arctic from a North American HEI put her role into perspective when pointing out the multiple areas of social responsibility HEI leaders carry: “I have to think a lot about the triple things. The pandemics, the social reckoning, and the economic uncertainties of the world.” President Mediterranean, also from a North American HEI, specifically mentioned their concern about racist tendencies toward specifically Chinese international students throughout COVID-19 as well as the impact the pandemic has on students’ mental health and wellbeing. When asked about particular struggles they have experienced international students having in their communities, President Mediterranean stated.

One would be racism. In particular, as international students, particularly in a closed society like we have right now where everyone is afraid with COVID-19 and in particular Chinese students [inaudible]. So access, mental health, challenges with isolation, I think are issues. And loneliness, they may not be able to go home or have gatherings of international students together.

Given that some students and staff had less challenges than others, the topic of remote learning and work came up as an issue of equity. President Pacific pointed out that she was concerned about equitable work and study conditions that enable every campus member to work in an environment that they feel safe in and that promotes their professional success, stating “[t]hat too is a social responsibility we have.” This sentiment was echoed by President Mediterranean, who identified the flexible working conditions as “an equalizer”:

I hope we’ll be a lot more accepting of flexible working condition with a combination of home and in the office. We’ve realized that this has been an equalizer also. We have multiple campuses. We have a campus in England, and so we can have a meeting where nobody has to travel, right? And everyone is on Zoom. So everyone is an equal player rather than having some people remote and some people in the room. We know that we can- - I think there’ll be a lot more meetings conducted like this as we go forward.

Besides concerns for social justice and equity in their institutions and beyond, the presidents also showed an active involvement in and desire to remove existing injustices.

Fighting existing injustices

The fight against existing inequities and injustices in their institutions was highlighted by all presidents to be an important part of their leadership and a personal concern. President Atlantic, for example, stated “We were leading the changes,” referring to COVID-related measures enabling all campus members to have access to safe work and study conditions. Injustices against international students throughout the pandemic constituted an important area of presidential concern and involvement. When talking about making sure internationals have access to all lectures despite regulations limiting the international students population to in-person only classes, President Pacific stated:

Previously, all those online lectures would not have been possible for internationals, but now we see that there was something that had to be done to support them. We grant them sort of a preliminary study permit and also trust them that they actually study actively. Being there in person has to take a back seat at the moment, also for internationals.

Ensuring equitable conditions for both domestic and international students as well as removing barriers standing in the way of this goal was not only a matter of institutional policy and lenience for the presidents, it was in fact very personal. President Southern described in detail how she personally made sure to alleviate the financial burden for international students who suffered from the lack of work opportunities and social networks:

Because many international students need to earn a little money while they are here. And where can they do that? Of course, mainly in restaurants in the service industry basically everything that had to be shut down because of COVID-19. That of course caused a lot of problems and worries for international students. I personally started a project to collect money to be able to help international students so they can bridge this difficult time where they cannot make any money.

This personal involvement and sense of responsibility for making change happen appeared as a defining feature of the educational leadership as perceived by the presidents themselves. President Atlantic elaborated on the ways in which she makes sure to keep herself accountable and on her toes when it comes to fighting injustices and effecting change:

I think you keep yourself very agile and alert if you wish to any trivial changes. Because for any new thing, every little changes sends a signal. Sends a signal either for your innovative idea to test, which may be the next feasible decision, or it alerts you to come up with the more sort of comprehensive precautionary [inaudible] which I learned from the process.

In their strive for a more just and equitable campus community, however, the interviewed presidents never lost sight of the importance of empathy and a general sentiment of care in their leadership.

Establishment of a sentiment of caring

Leading their institutions and their members through crises “takes clear leadership, clear statements, and you have to comfort people, calm people” (President Southern). Besides taking action and effecting change, the presidents all emphasized the importance of the care and empathy they all showed for their communities. President Mediterranean, for example, made sure to keep up personal lines of communication and a sense of proximity even when the campuses remained empty during the height of the pandemic “because I worry about them [the students]”:

Personally, if I get an email from a parent or student, I respond. I personally respond because the stories are heartbreaking. It is so tough for students to be learning online. And the group that is really struggling in our campus is our first-year engineering students. They are finding it really tough. I think just the content and the pedagogy has been really hard. So I think we’ve done surveys. We have to pay attention. We have to support them. We have full responsibility as if they were on campus during the global crisis.

The importance of personal contact and a connection with the students was also mentioned by President Southern. She particularly emphasized the vulnerability of young people and the responsibility she felt for ensuring they don’t fall through the metaphorical cracks of a too impersonal crisis management:

So, I was very happy that we managed to at least give them 2 weeks of face-to-face instruction. And it hurt my soul that we then had to go back to online only. We have to take care of the young people. Not everyone copes well with online instruction. And if we don’t pay attention, we will lose many people. People that under normal circumstances would have done just fine.

The care the presidents showcased throughout the pandemic extended into the surrounding communities, reaffirming the HEIs’ central roles in their communities and the presidents’ role not only as campus, but community leaders. President Mediterranean elaborated on the ways in which she felt connected to and responsible for her communities and stated:

We cared about them. We were listening to them. We were getting out to the communities (…). So it was really important that as the leader, I was visible there. Because they’re part of the university. And there’s all kinds of research stations all over the province, which is part, again, of the university that I had to visit and make sure that people knew that they were thought of and cared about in a time of crisis.

The care the presidents showed both their on and off campus communities also included an active element of involving them in the decision-making process. President Arctic described how she cared for and involved various campus members in the crisis management process:

So whenever I meet someone, whether it be a parent, a faculty, or a staff or a student, I’m saying, “Tell me your thoughts on COVID-19. Should we open? Should we close? How have you been experiencing it?” I have ways to get to those conversations. And so it was a lot of informal and formal mechanisms. We just surveyed to ask students what they wanted. But I don’t know what your other interviewers are experiencing, but there are no right answers. There’s some people who want to be on campus. There’s some people who think the university should be shut down.

Care and involvement in presidential leadership created the desire in the campus leaders to empower all stakeholders, equipping them with the necessary tools and skills to not only survive during crises but thrive throughout it.

Empowerment of all stakeholders

The formation of empowered crisis management teams to support the campus leaders throughout the pandemic was deemed crucial by all presidents. President Southern stated that she built those teams “with the idea of participation in mind. So, I wanted there to be students, I wanted there to be employees, I wanted all stakeholders of the university involved in some shape or form” and that [t]here also needs to be a certain level of trust between all the stakeholders and a certain level of connectedness.”

Empowering the various stakeholders of the campus community by trusting them to make informed decisions and remaining connected even during remote work conditions seemed to be a presidential priority. President Atlantic echoed this sentiment, stating that one “should be always sensitive to different stakeholders in this community.” Empowerment could also be established through positive affirmation and acknowledgment of good work, as mentioned by President Mediterranean, who said “that was really important for me, as a stabilizer and also as a promoter, to keep people positive and aware of the amazing work they were doing in a time of crisis.”

Discussion

The results of this study illustrate how the FEL framework can be found in the ways women HEI presidents around the world lead their institutions through crises. All four elements of FEL were reflected in the interviews with the individual presidents, bringing attention to the importance of social justice for all stakeholders throughout crises, an active attempt to increase said justice and equity in the campus communities, establishing a sentiment of caring, and the continued empowerment of the stakeholders. The presidents acknowledged the value of and need for creating a socially just campus environment for all stakeholders throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and were often “motivated by equity” (Strachan, 1999a, p. 310) in their crisis leadership. This motivation, however, did not remain a purely idealistic longing for more equitable conditions, but was realized in concrete actions by the campus leaders in order to “experience how things might be different” (Strachan, 1999b, p. 122). The presidents showed that they truly cared about and for their campus communities and all stakeholders involved. Following Strachan’s (1999b) understanding of caring as a means “to address the needs that arose out of being oppressed and repressed; so caring could be liberatory” (p. 123), the presidents who cared also made it a point to empower their stakeholders and “eliminate institutional domination” (p. 123).

While leadership and its’ practice is always embedded in and influenced by specific social and cultural contexts (Hofstede, 2001; Branzei, 2002; Dorfman and House, 2004; Shah, 2021), the results indicated that despite their different environments, the women presidents all incorporated elements of FEL in their leadership throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Complex and novel crises like the one caused by COVID-19 demand increased sensitivity and empathy from leaders (Tevis, 2021), making FEL as the combination of sentiments of caring, empowerment, and applied social justice particularly suitable for these types of crises. Although the sample size of five interviewed women presidents may seem small, the strength of the findings is amplified by the fact that the interviews were not initially structured to produce elements of FEL in the respective presidents’ responses. Being a subsample of a bigger sample for studies around presidential leadership during COVID-19, the five women presidents showcased FEL in the way they guided their institutions. A number of policy implications and opportunities for future research can be tied to these insights.

Policy implications and future research

Employing FEL to understand how women university presidents lead during crises provides valuable insights into the ways in which women in leadership positions leverage their power and impact to improve the conditions for all stakeholders of their institutions. Women leaders don’t need to emphasize or hide their gender identities, instead they excel in the ways in which their leadership benefits the greater good and effects positive change that encompasses institutional as well as national borders.

Seeing how women HEI leaders in this study employed FEL to successfully lead their institutions through crises emphasizes the importance of equity-oriented leadership, both in and outside of crises. Educational leadership needs to be focused on equity among its stakeholders (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2014) in order to fulfill its call for social justice in the realm of education and beyond. Additionally, this study supports the call for purposeful inclusion of women in all senior teams to provide perspective. In order to respond to the growing demands for more equitable, empowering, and socially just forms of leadership, women need to be included not as mere gender statistics, but rather as capable leaders that bring potentially different lenses to the metaphorical or actual round tables of leadership teams.

Future research in the area of crisis leadership should deepen our understanding of how women can increase their access to high-level leadership positions within higher education as well as investigate further the specific leadership dynamics that render them successful in their roles. The focus needs to be placed on women at all levels of higher education in order to get a better understanding of the leadership dynamics within and between those levels. Another potential avenue for future research is the development of more focused studies on specific decisions HEI presidents make in relation to FEL as well as the inclusion of non-4 year institutions like United States community colleges.

Conclusion

The positive effect of women’s leadership (Noland et al., 2016; Zhou, 2020) and their arguable better suitedness compared to their male counterparts as leaders through crises (Eagly and Heilman, 2016; Gedro et al., 2020) could potentially be partly due to FEL as a component of women’s leadership styles. Overall, this study’s results echo the strengths identified in the scarce existent research on women presidents in times of crises, such as collaboration, mutual empowerment, and responsibility for the wellbeing of the campus community (Shepherd, 2017; Reed and Disbrow, 2020). Given the need for new ways to think about and conceptualize crisis leadership (McNaughtan et al., 2019), FEL provides a useful lens through which both women and men in leadership roles can evaluate their leadership practices and priorities.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the IRB Texas Tech University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SS took the lead in this project and performed the first cycle of coding as well as the manuscript draft. JM had a supervisory role, performed second cycle coding, and proof-read the manuscript. Both authors were involved in data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acker, S. (2012). Chairing and caring: Gendered dimensions of leadership in academe. Gender Educ. 24, 411–428. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2011.628927

Alexander-Floyd, N. G. (2010). Critical race Black feminism: A “jurisprudence of resistance” and the transformation of the academy. Signs 35, 810–820. doi: 10.1086/651036

Almaiah, M. A., Al-Khasawneh, A., and Althunibat, A. (2020). Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Inform. Technol. 25, 5261–5280. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y

American Association of Colleges and Universities [AAC&U] (2020). Responding to the Ongoing COVID-19 Crisis and to Calls for Racial Justice: A Survey of College and University Presidents. Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges and University.

American Council on Education [ACE] (2020). College and University Presidents Respond to COVID-19: April 2020 Survey. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., and Beligiannis, G. N. (2021). Transformational leadership and digital skills in higher education institutes: during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg. Sci. J. 5, 1–15. doi: 10.28991/esj-2021-01252

Barton, T. (2006). Feminist leadership: Building nurturing academic communities. Adv. Women’s Leadersh. Online J. 22, 1–8.

Basilaia, G., Dgebuadze, M., Kantaria, M., and Chokhonelidze, G. (2020). Replacing the classic learning form at universities as an immediate response to the COVID-19 virus infection in Georgia. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 8, 101–108. doi: 10.22214/ijraset.2020.3021

Bellis, P., Trabucchi, D., Buganza, T., and Verganti, R. (2022). How do human relationships change in the digital environment after COVID-19 pandemic? The road towards agility. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 25. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-02-2022-0093

Blackmore, J. (2013). A feminist critical perspective on educational leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 16, 139–154. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2012.754057

Blackmore, J. (1996). “‘Breaking the silence’: feminist contributions to educational administration and policy,” in International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration. Kluwer International Handbooks of Education, eds K. Leithwood, J. Chapman, D. Corson, P. Hallinger, and A. Hart (Dordrecht: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-1573-2_29

Blanco Ramírez, G. (2016). Many choices, one destination: Multimodal university brand construction in an urban public transportation system. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 29, 186–204. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2015.1023233

Branzei, O. (2002). Cultural explanations of individual preferences for influence tactics in cross cultural encounters. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2, 203–218. doi: 10.1177/1470595802002002873

Brown, T. M. (2005). Mentorship and the female college president. Sex Roles 52, 659–666. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-3733-7

Burkinshaw, P., Cahill, J., and Ford, J. (2018). Empirical evidence illuminating gendered regimes in UK higher education: developing a new conceptual framework. Educ. Sci. 8:81. doi: 10.3390/educsci8020081

Burkinshaw, P. (2015). Higher Education, Leadership and Women Vice Chancellors: Fitting in to Communities of Practice of Masculinities. Berlin: Springer. doi: 10.1057/9781137444042

Chronicle of Higher Education [CHE] (2020). Here’s Our List of Colleges Reopening Models. Washington, DC: Chronicle of Higher Education.

Cheng, S. Y., Wang, C. J., Shen, A. C. T., and Chang, S. C. (2020). How to safely reopen colleges and universities during COVID-19: experiences from Taiwan. Ann. Internal Med. 173, 638–641. doi: 10.7326/M20-2927

Clover, D. E., Etmanski, C., and Reimer, R. (2017). Gendering collaboration: Adult education in feminist leadership. New Direct. Adult Cont. Educ. 156, 21–31. doi: 10.1002/ace.20247

Coates, H., Xie, Z., and Wen, W. (2021). Global University President Leadership: Insights on Higher Education Futures. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003248286

Coleman, M. (2012). Leadership and diversity. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 40, 592–609. doi: 10.1177/1741143212451174

Corson, D. (2000). Emancipatory leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 3, 93–120. doi: 10.1080/136031200292768

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dorfman, D. (2005). Educational leadership as resistance. J. Curr. Pedagogy 2, 157–172. doi: 10.1080/15505170.2005.10411564

Dorfman, P. W., and House, R. J. (2004). Cultural influences on organizational leadership: Literature review, theoretical rationale, and GLOBE project goals. Cult. Leadersh. Organ. 62, 51–73.

Doten-Snitker, K., Margherio, C., Litzler, E., Ingram, E., and Williams, J. (2021). Developing a shared vision for change: Moving toward inclusive empowerment. Res. Higher Educ. 62, 206–229. doi: 10.1007/s11162-020-09594-9

Dumulescu, D., and Muţiu, A. I. (2021). Academic Leadership in the Time of COVID-19- Experiences and Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 12:648344. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648344

Eagly, A. H., and Heilman, M. E. (2016). Gender and leadership: Introduction to the special issue. Leadersh. Q. 27, 349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.04.002

Ely, R. F., and Rhode, D. L. (2010). “Women and leadership: Defining the challenges,” in Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice, eds N. Nohria and R. Khurana (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press), 377–410.

Farre, L., and Ortega, F. (2021). Family Ties, Geographic Mobility and the Gender Gap in Academic Aspirations. IZA Discussion Paper No. 14561. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3892589 (accessed August 23, 2022).

Fernandez, A. A., and Shaw, G. P. (2020). Academic leadership in a time of crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19. J. Leadersh. Stud. 14, 39–45. doi: 10.1002/jls.21684

Gedro, J., Allain, N. M., De-Souza, D., Dodson, L., and Mawn, M. V. (2020). Flattening the learning curve of leadership development: reflections of five women higher education leaders during the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 23, 395–405. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2020.1779911

Gigliotti, R. A. (2019). Crisis Leadership in Higher Education: Theory and Practice. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvscxrr0

Grundy, S. (2017). “Educational leadership as emancipatory praxis,” in Gender Matters in Educational Administration and Policy, eds J. Blackmore and J. Kenway (Abingdon: Routledge), 165–177. doi: 10.4324/9781315175089-13

Fitzgerald, T. (2013). Women Leaders in Higher Education: Shattering the Myths. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203491515

Fuller, K. (2021). Feminist Perspectives on Contemporary Educational Leadership. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780367855635

Glazer, J. S. (1991). Feminism and professionalism in teaching and educational administration. Educ. Admin. Q. 27, 321–342. doi: 10.1177/0013161X91027003005

Griggs, M., and Thouin, C. (2021). Presidential influence: How a university president handles crisis and cultivates campus culture for an online learning community. J. Cases Educ. Leadersh. 25, 96–108. doi: 10.1177/15554589211035155

Grummell, B., Devine, D., and Lynch, K. (2009). The care-less manager: Gender, care and new managerialism in higher education. Gender Educ. 21, 191–208. doi: 10.1080/09540250802392273

Harkavy, I., Bergan, S., Gallagher, T., and van’t Land, H. (2020). “Universities must help shape the post-Covid-19 world,” in Higher Education’s Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic, eds S Bergan, T. Gallagher, I. Harkavy, R. Munck, and H. van’t Land (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing).

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Hussain, S. B. (2014). Crisis communication at higher education institutions in South Africa: A public relations perspective. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 6, 144–151. doi: 10.22610/jebs.v6i2.477

International Association of Universities [IAU] (2021). COVID-19: Higher Education Challenges and Responses. Paris: International Association of Universities.

International Association of University Presidents (IAUP) (2020). Leadership Responses to COVID-19: A Global Survey of College and University Leadership. Available online at: https://www.iaup.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IAUP-Survey-2020-ExecutiveSummary.pdf (accessed August 23, 2022).

Ishimaru, A. M., and Galloway, M. K. (2014). Beyond individual effectiveness: Conceptualizing organizational leadership for equity. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 13, 93–146. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2014.890733

Kezar, A. (2014). “Women’s contributions to higher education leadership and the road ahead,” in Women and Leadership in Higher Education, eds K. A. Longman and S. R. Madsen (Charlotte Mecklenburg County, NC: IAP Information Age Publishing).

Klenke, K. (2016). “Qualitative research as method,” in Qualitative Research in the Study of Leadership, eds S. S. Martin and J. R. Wallace (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited). doi: 10.1108/9781785606502

Liu, L., Hong, X., Wen, W., Xie, Z., and Coates, H. (2020). Global university president leadership characteristics and dynamics. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 2036–2044. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1823639

Longmuir, F. (2020). Exploring intersections of educational leadership, educational change and student empowerment. Lead. Manag. 26, 46–53.

Maheshwari, G., Nayak, R., and Ngyyen, T. (2021). Review of research for two decades for women leadership in higher education around the world and in Vietnam: a comparative analysis. Gender Manag. 36, 640–658. doi: 10.1108/GM-04-2020-0137

Marshall, J., Roache, D., and Moody-Marshall, R. (2020). Crisis leadership: A critical examination of educational leadership in higher education in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Stud. Educ. Admin. 48, 30–37.

Marshall, C., Taylor Bullock, R., and Goodhand, M. (2020). “Social justice leadership and navigating systems of inequity in educational spaces,” in Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education, ed. R. Papa (Cham: Springer Cham). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14625-2_76

Marsicano, C. R., Barnshaw, J., and Letukas, L. (2020). Crisis and change: How COVID-19 exacerbated institutional inequality and how institutions are responding. New Direct. Inst. Res. 18, 7–30. doi: 10.1002/ir.20344

Matthews, E. N. (1996). “Women in educational administration: Views of equity,” in Women Leading in Education, eds D. Dunlap and P. Schmuck (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press).

McClure, K., and McNaughtan, J. (2021). Proximity to power: The challenges and strategies of interviewing elites in higher education research. Qual. Rep. 26, 974–992. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4615

McNaughtan, J., Garcia, H., Schiffecker, S., Norris, K., Jackson, G., Eicke, D., et al. (2022). Surfing for an answer: understanding how institutions of higher education in the United States utilized websites in response to COVID-19. J. Comparat. Int. Higher Educ. 14, 111–129.

McNaughtan, J., Louis, S., García, H. A., and McNaughtan, E. D. (2019). An institutional North Star: the role of values in presidential communication and decision-making. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 41, 153–171. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2019.1568848

McNaughtan, J., and McNaughtan, E. D. (2019). Engaging election contention: Understanding why presidents engage with contentious issues. High. Educ. Q. 73, 198–217. doi: 10.1111/hequ.12190

Moon, D. G., and Holling, M. A. (2020). “White supremacy in heels”:(white) feminism, white supremacy, and discursive violence. Commun. Crit. 17, 253–260. doi: 10.1080/14791420.2020.1770819

Morley, L. (2013). The rules of the game: Women and the leaderist turn in higher education. Gender Educ. 25, 116–131. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2012.740888

Noland, M., Moran, T., and Kotschwar, B. R. (2016). Is Gender Diversity Profitable? Evidence From A Global Survey. (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper), 16–3.

Nugroho, I., Paramita, N., Mengistie, B. T., and Krupskyi, O. P. (2021). Higher education leadership and uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Socioecon. Dev. 4, 1–7. doi: 10.31328/jsed.v4i1.2274

New York Times [NYT] (2020). Tracking the Coronavirus at U.S. Colleges and Universities. Eighth Avenue, NY: New York Times.

Ortega, M. (2006). Being lovingly, knowingly ignorant: White feminism and women of color. Hypatia 21, 56–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2006.tb01113.x

Parker, P. (2015). The historical role of women in higher education. Admin. Issues J. Educ. Pract. Res. 5, 3–14. doi: 10.5929/2015.5.1.1

Pearson, W., and Reddy, V. (2021). “Social justice and education in the twenty-first century,” in Social Justice and Education in the 21st Century, eds W. Pearson and V. Reddy (Cham: Springer), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-65417-7_1

Peyton, G. L., and Ross, D. B. (2022). “Servant and shepherd leadership in higher education: Empowerment and mentorship,” in Key Factors and Use Cases of Servant Leadership Driving Organizational Performance, ed. P. Maria (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 272–292. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-8820-8.ch011

Raghavan, A., Demircioglu, M. A., and Orazgaliyev, S. (2021). COVID-19 and the new normal of organizations and employees: an overview. Sustainability 13, 1–19. doi: 10.3390/su132111942

Reed, C. J., and Disbrow, L. M. (2020). Remotely risky? an exploratory study of COVID-19 risk- mitigation messaging of female presidents at research-intensive universities. SoJo J. 6, 3–20.

Samier, E. A. (2021). “Critical and postcolonial approaches to educational administration curriculum and pedagogy,” in Internationalisation of Educational Administration and Leadership Curriculum, eds E. A. Samier, E. S. Elkaleh, and W. Hammad (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited). doi: 10.1108/9781839098642

Schiffecker, S., McNaughtan, J., Castiello, S., Garcia, H., and Li, X. (2022). Leading the many, considering the few - university presidents’ perspectives on international students during COVID-19. J. Comparat. Int. Higher Educ. 14, 13–28.

Shah, S. (2021). Navigating gender stereotypes as educational leaders: An ecological approach. Manag. Educ. doi: 10.1177/08920206211021845

Shepherd, S. (2017). Why are there so few female leaders in higher education: A case of structure or agency? Manag. Educ. 31, 82–87. doi: 10.1177/0892020617696631

Shultz, L., and Viczko, M. (2016). “Global social justice, democracy and leadership of higher education: An introduction,” in Assembling and Governing the Higher Education Institution, eds L. Shultz and M. Viczko (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 1–7. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-52261-0_1

Smalley, A. (2021). Higher Education Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Available online at: https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/higher-education-responses-to-coronavirus-covid-19.aspx (accessed August 23, 2022).

Sperandio, J. (2010). Modeling cultural context for aspiring women educational leaders. J. Educ. Admin. 48, 716–726. doi: 10.1108/09578231011079575

Spradley, R. T. (2020). Image restoration for university leaders’ public health COVID-19 response: a case study of Notre Dame. Int. Res. J. Public Health 4:47. doi: 10.28933/irjph-2020-10-0906

Strachan, J. (1999a). Feminist educational leadership: Locating the concepts in practice. Gender Educ. 11, 309–322. doi: 10.1080/09540259920609

Strachan, J. (1999b). Feminist educational leadership in a New Zealand neo-liberal context. J. Educ. Admin. 37, 121–138. doi: 10.1108/09578239910262962

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strielkowski, W., and Wang, J. (2020). “An introduction: COVID-19 pandemic and academic leadership,” in Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Social, Economic, and Academic Leadership (ICSEAL-6-2019), (Amsterdam: Atlantis Press), 1–4. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.200526.001

Taub, A. (2020). Why are Women-Led Nations Doing Better with COVID-19?. Eighth Avenue, NY: The New York Times.

Taylor, D. B. (2021). A Timeline of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Eighth Avenue, NY: The New York Times.

Taysum, A., and Arar, K. (eds) (2018). Turbulence, Empowerment and Marginalisation in International Education Governance Systems. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. doi: 10.1108/9781787546752

Teague, L. J. (2015). “Higher education plays critical role in society: More women leaders can make a difference,” in Proceedings of the Forum on Public Policy Online (Vol. 2015, No. 2), Oxford Round Table, Urbana, IL.

Tevis, T. (2021). “It’s a sea-change”: Understanding the role the racial and socio-political climate play on the role-shift of the American college presidency. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 29, 1–22. doi: 10.14507/epaa.29.5153

Thelen, P. D., and Robinson, K. L. (2019). Crisis communication in institutions of higher education: Richard Spencer at the University of Florida. Commun. Q. 67, 444–476. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2019.1616586

Thompson-Adams, A. (2012). The Lived Experiences of Female University Presidents in Texas: Stories From a Feminist Standpoint. [Texas State University-San Marcos]. Social Science Premium Collection (1651847944; ED550892). Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/lived-experiences-female-university-presidents/docview/1651847944/se-2?accountid=7098 (accessed August 23, 2022).

Times Higher Education (2020). Available online at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/academic/press-releases/women-lead-20-percent-worlds-top-universities-first-time (accessed August 23, 2022).

Townsend, C. V. (2020). Identity politics: Why African American women are missing in administrative leadership in public higher education. Educ. Admin. Leadersh. 49, 584–600. doi: 10.1177/1741143220935455

Walker, S., Strong, K., Wallace, D., Sriprakash, A., Tikly, L., and Soudien, C. (2021). Special issue: Black Lives Matter and global struggles for racial justice in education. Comp. Educ. Rev. 65, 196–198. doi: 10.1086/712760

Wanjiku, S. M., Karobia, A. W., and Karimi, J. (2020). Women in the Education sector: Monitoring and evaluation of women empowerment and educational leadership. Int. J. Educ. Learn. Syst. 5, 10–20.

Wilkinson, J. (2021). Educational Leadership Through a Practice Lens: Practice Matters. Berlin: Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-7629-1

World Health Organization (2020). Archived: WHO Timeline-Covid-19. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wrighton, M. S., and Lawrence, S. J. (2020). Reopening colleges and universities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Int. Med. 173, 664–665. doi: 10.7326/M20-4752

Xiang, X., Ingram, J., Cangemi, M. A., and EdD, J. (2017). Barriers contributing to under-representation of women in high-level decision-making roles across selected countries. Organ. Dev. J. 35, 91–106.

Keywords: higher education leadership, feminist educational leadership, COVID-19, university president, global university leadership

Citation: Schiffecker S and McNaughtan J (2022) Leading the way–Understanding women’s university leadership during crisis through a feminist educational leadership lens. Front. Educ. 7:982952. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.982952

Received: 30 June 2022; Accepted: 29 July 2022;

Published: 02 September 2022.

Edited by:

Elizabeth C. Reilly, California State University Channel Islands, United StatesReviewed by:

Khalida Parveen, Southwest University, ChinaReyes L. Quezada, University of San Diego, United States

Copyright © 2022 Schiffecker and McNaughtan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Schiffecker, c2FyYWguc2NoaWZmZWNrZXJAdHR1LmVkdQ==

Sarah Schiffecker

Sarah Schiffecker Jon McNaughtan

Jon McNaughtan