- Humanities Department, Language Education for Refugees and Migrants (L.R.M), Hellenic Open University, Patras, Greece

Since 2015, Greece has seen a large influx of refugees, resulting in increased needs for accommodation and education provision. As most newcomers come in family units, innovative educational measures were established to assist schooling and inclusion for refugee children. Schools provide opportunities to young refugee communities for initiating connections and maintaining friendships with local native peers. However, segregated accommodation structures, such as large, remote Refugee Hospitality Centers, can hinder this process. A small-scale study was conducted at Skaramagas refugee camp in the outskirts of Athens, to investigate the number and type of friendships formed by adolescent refugees, including friendships with refugees/migrants from other countries, as well as native peers. Certain sociological factors, such as age, sex, country of origin, school attendance and duration of stay in Greece, were examined. The study was conducted through semi-constructed interviews with 21 adolescent students at the Refugee Hospitality Center, all of whom attended onsite non-formal language classes, although only half attended formal education outside the camp. The results indicate the positive impact of school attendance on relational inclusion and widening friendship circles. Children attending local formal schools were more likely to widen their friendship circles and form friendships with native peers than children who only attended non-formal classes inside the camp. Girls appear to have fewer friendships than boys, ethnicity and age do not seem to provide any significant differentiation, whereas duration of stay in Greece does not seem to affect socialization patterns directly. This study examines the patterns of friendship formation among newly arrived refugee adolescents and highlights the impact of schooling on relational inclusion, even at highly segregated accommodation structures, such as remote refugee camps.

Introduction

Since 2015, Greece became a main reception country for large numbers of refugees through the Mediterranean route. Most of these refugee populations did not aim Greece to be their final destination country, but only a temporary transit point through their journey to another European country (Kuschminder, 2018:3). However, many refugees and migrants end up staying in Greece longer than expected or, eventually, settle in Greece permanently (UNICEF, 2017, p. 11). In 2020, over 44,000 refugee children lived in Greece (UNICEF, 2021, p. 3). Facing severe obstacles regarding their psychological and social well-being, including the formation of peer friendships. These children should be included and empowered as active individuals who are able to speak for themselves and create their own futures (Gornik, 2020, p. 536).

Skaramagas refugee camp was chosen as a representative structure to investigate refugee children’s social lives and friendship patterns. One of the largest camps in mainland Greece, it operated at the outskirts of Pireaus port, at a remote former dock area, from 2016 until 2021. In 2020, Skaramagas refugee camp hosted from 2,000 to 3,200 refugee families during its operation, mostly from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and African countries (Palaiologou et al., 2021, p. 320), with 40% of its population estimated under 18 years old. Since the beginning of its operation in 2016, a formal education scheme was established by the Ministry of Education to meet refugee children’s educational needs. The scheme was implemented in two routes: (1) The Reception Class route, with refugee children attending morning mainstream schools, with 15 h per week segregated Greek language classes and 17 h per week mixed mainstream classes on other academic subjects. (2) The Structures for the Welcoming and Education of Refugees route: One-year preparatory, wholly segregated, afternoon classes were formed for refugee children aged 4 to 15 years, with no knowledge of Greek language. The Structures for the Welcoming and Education of Refugees resulted as an emergency measure, especially at the peak of refugee influxes, lasting one school year at most, after which, refugee children moved onto a morning mainstream Reception Class (Palaiologou et al., 2021, pp. 323–324).

Formal school attendance was found to have a positive impact for refugee children at Skaramagas refugee camp, in terms of their psychosocial well-being and mental health (Fasaraki, 2020, p. 88). The purpose of this study is to investigate more specifically the friendship patterns of the camp’s refugee children and the impact of formal school attendance regarding the formation of multicultural friendships and the promotion of relational inclusion. The study’s goal was to approach children’s lived experiences and social life stories, through the perspective of children’s understanding. Researchers performed general interviews on key issues affecting children’s lives, with some key questions on relational history, such as “Have you made new friends?”, “What countries are they from?”, “What do you like to do with your friends?”, “Have you been to school by bus, outside the camp, where there are also children from Greece?”, “How did you find it?”, “Which people in particular will you turn to for help when you need something at the camp?.” The sample of interviewed children was chosen from non-formal education classes running onsite at Skaramagas camp by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and municipal authorities. All non-formal educational programs at camp had been granted approval by the Ministry of Education (SIRIUS Watch, 2018, p. 11).

Materials and methods

The research intended to investigate refugee teenagers’ socialization patterns with peers from the same country, different countries of origin and local native peers and how their socialization changes by age, sex, country of origin, duration of stay in Greece and formal education attendance. The sample of participants interviewed for this purpose consisted of pre-adolescent and early to middle adolescent children (ages normally corresponding to secondary education), all inhabitants at Skaramagas refugee camp. This age range was chosen in order to ensure that they could answer the research questions in a meaningful and reliable way. The sample (N) consisted of 21 children, 14 girls and 7 boys. The countries of origin were Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and their ages varied between 10 and 17 years old. Children had been in Greece between 7 and 72 months. During the interviews, children were approached as creative participants in the narration of their life stories and experiences. The interviewees were welcomed in a culturally appropriate way and explanations were given about the research’s nature and purpose, in a simplified language they could understand. These explanations were necessary so that they did not feel threatened that any information gathered would in any way be used against them. The research team avoided any ‘guiding’ hints that would bias their answers. Researchers adapted their approach, whenever necessary, to respect children’s privacy, developmental level, fluency, and psychological condition. Interviewees were given enough time to express themselves, knowing they could stop participating at any moment without explanations or they could ask for more information about the research. Confidentiality was maintained and a code number was used for each interviewee during the data collection/organization process, as well as the results’ presentation phase, in order to protect children’s identities. A mixed-methods framework was used, with both qualitative and quantitative data: certain sociological indicators were examined, in order to understand how refugee teenagers perceived their transition to a social life within their new linguistic-cultural environment.

A significant amount of time and effort were dedicated to planning and preparation of data collection, as access to refugees hosted in Refugee Hospitality Centers is controlled by government authorities and the interviewers’ team requested official permission to conduct research. The aims, objectives and methods of the research project were approved, as well as the results’ use for the amelioration of refugees’ condition. Children, as minors, are not legally authorized to consent, therefore, parental permission was asked. The research team applied the “do no harm” principles in interviews, so that children would not feel uncomfortable or pressed for answers. Discretion and sensitivity were used, so that the interview proceeded like a free-flowing discussion, without causing children psychological stress. The semi-structured interviews had a duration of 7–16 min and were assisted by translators, provided by NGOs operating onsite. The interviews’ audio files were transcribed verbatim using a transcription service. Open questions, empathetic rephrasing, warmth, light humor and explanation of the research’s goals helped interviewees relax and trust the interview process. Some older children had prior experience with being interviewed, which facilitated the process further. The number of interview participants was small, so a full statistical analysis was not possible. Additionally, as child participants are often not used to talking about themselves and/or give answers that they think would please the interviewers, this means that the outcomes were indicative, but nevertheless notable, particularly regarding the role of schooling in establishing friendships and relational integration within the local community.

Finally, the research interviews were conducted by the Hellenic Open University’s research team between July and September 2020 during six separate visits at Skaramagas Refugee Hospitality Centre (on the 16th, 23rd, 27th, 29th of July 2020, 1st and 15th of September 2020). Prior to the interviews, several preparatory visits were conducted from August 2019 until November 2019 to investigate the field dynamics, establish cooperative liaisons with the camp’s staff and build a climate of trust with the students through observation of non-formal classes and contribution to class creative activities. Unfortunately, there was a gap between November 2019 and May 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting closures. The research team resumed its work with the interviewee population immediately after the pandemic restrictions ended and recapitulated the preparation work with the target population during May–June 2020. The project was implemented in the frame of the HORIZON Project MICREATE, coordinated by the Science and Research Center, KOPER in Slovenia.

Results

Formation of friendships with peers, with whom they share common interests, ideals and recreational activities is key to teenagers’ psychological well-being. It is expected that during this development period (early adolescence between ages 10 and 14 and middle adolescence between 15 and 17), adolescents are intensely interested in peer relations and crystallize their choice of casual friends and best friends. Although, many friendships may be transient and temporary, they form an important pillar in children’s psycho-emotional development. Lack of friendships during adolescence contributes to depression, withdrawal, low motivation and low self-esteem and it is important to understand the factors contributing or hindering socialization for refugee children at Skaramagas camp. During the interviews, children’s social lives were investigated. Generally, participants spoke easily about their socialization, with only two exceptions of children who did not give much information. A clear picture emerged, that friendships with native children were not common and on one occasion, negative (“Children at Greek school looked at us weird”). It was investigated how refugee children’s friendships varied with country of origin, duration of stay in Greece and gender. Specific question about socialization with local children were asked “Do you have any friends here in Greece?,” followed by other clarifying questions, such as “Did you make any new friends in Greece?,” “Do you have any Greek friends?,” “Do you like/play with Greek children at school?.” All friendships are expected to have been formed in Greece, as refugees come in family units or family fragments, so they create their social circle from the start, when they arrive at camp.

Friendships patterns and country of origin

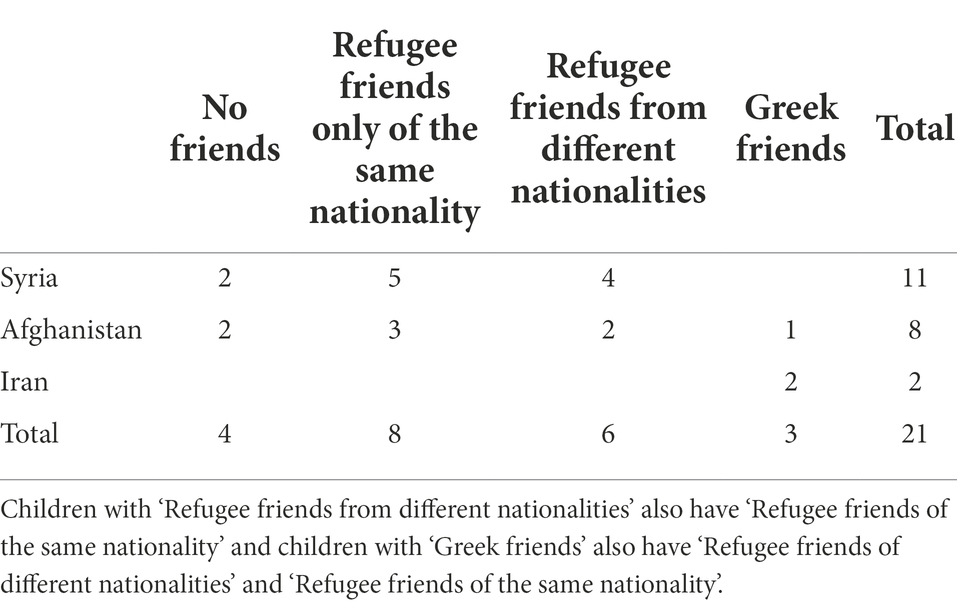

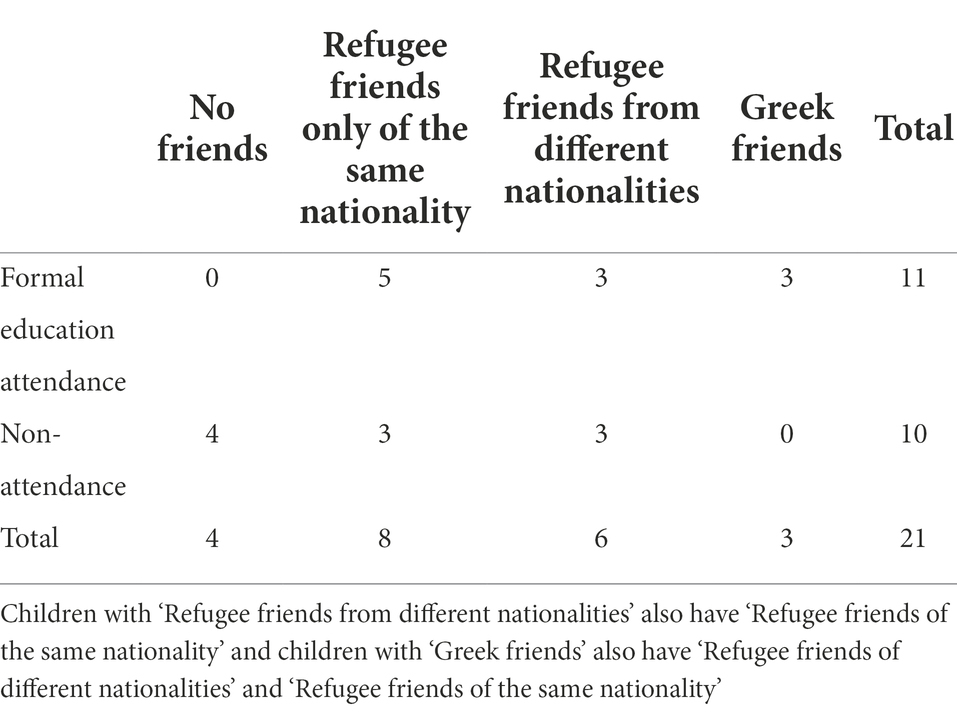

Table 1 presents four categories of friendship patterns, positioned as an increasingly wider social circle. Interviewed children report: (a) having no friends, (b) having only refugee friends from the same nationality as their own, (c) having refugee friends from different refugee nationalities, (d) having Greek children as friends. In all Tables, category (d) includes (b) and (c), meaning that, children with Greek friends also have refugee friends from the same or other nationalities, and category (c) includes (b), meaning that children with refugee friends from other nationalities also have refugee friends from the same nationality. Therefore, in all Tables, the columns represent a gradual expansion of socialization patterns from ‘no friends’ to friends from increasingly different backgrounds.

Unsurprisingly, most interviewees reported having friends either from the same nationality or from other refugee nationalities hosted at camp, the site where refugee children spend most of their day and do most of their past-time activities. The camp is geographically isolated and remote from the urban environment, so it is difficult for children to socialize outside the camp. One child reported “I know Greek children from school, and I wish we could play together, but they live very far’. Another child said “We know Greek children from school, but we cannot have fun with them.” There is a worrying number of children (4 out of 21) who reported having no friends and remained silent without any further clarifications. Syrian children appeared to have no Greek friends and seemed to prefer friends from the same nationality. This may relate to the length of their stay in Greece (Syrian refugees tend to be relocated to other European countries faster than Afghan refugees), their attendance of Greek formal education (Syrian teenagers are less involved in Greek formal education and Greek language learning than their Afghan peers) and their general lack of investment in Greece as a country of destination.

Participants seemed to prioritize and value friendship. An Iranian boy with many friends from different nationalities stated about his friends: “I made a big map and I was like putting some sticks on the countries they were coming from.” 4 out of 21 participants stated that one of their key expectations when they came to Greece was ‘to find friends’, as shown in the following interview with an 11-year old Afghan boy:

Researcher: “What do you think children from other countries want to have when they come to a foreign country, e.g., Greece?”

Interviewee: “A normal house, friends, toys and go to school… I have many friends in Greece and I want to stay but not in the camp. I want a real house.”

A girl stated that her happiest moment since coming to Greece was when “I went to school and made new friends” and another girl that her favorite activity was “playing with my friends.”

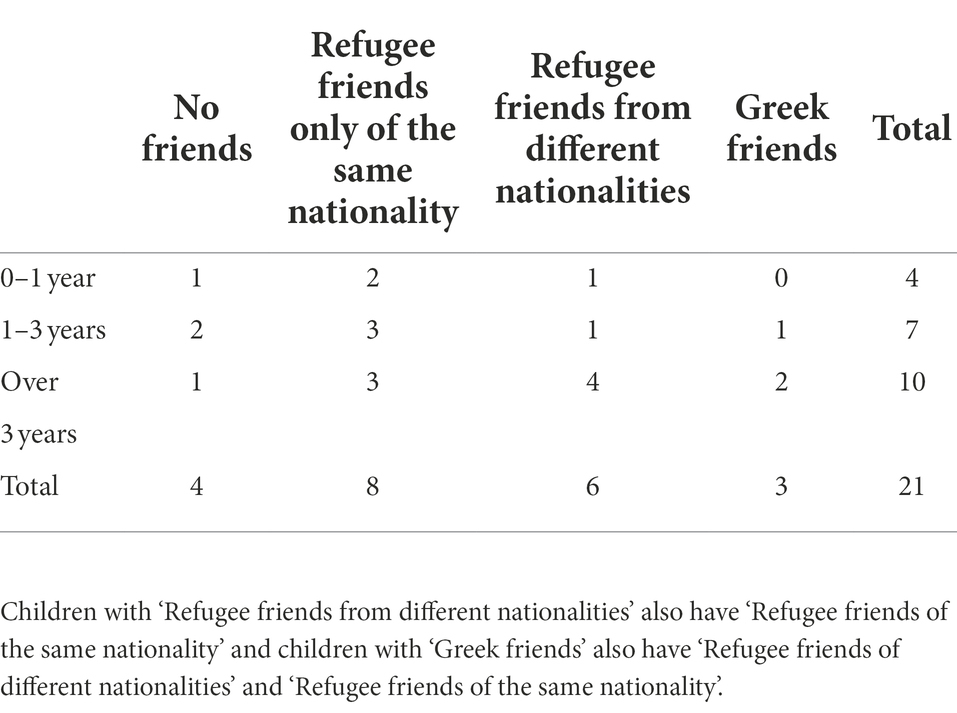

Friendship patterns and duration of stay in Greece

The next factor investigated was the duration of stay in Greece and whether it influenced the formation of friendships for teenagers. Most children interviewed have been in Greece for more than a year, sufficient time to form friendships at camp and at school, provided students attended. Table 2 results show that there is little differentiation depending on length of stay, as there are children with no friends, even after living 3 years at camp. So, duration of stay does not seem to be a determining factor. It must be noted that arrival in Greece was reported as the happiest moment in most children’s journeys from their country of origin (Prekate and Palaiologou, 2022, p. 13). Most children experienced severe difficulties during the journey and reported that they were very relieved to have arrived and that one of the main expectations refugee children had upon arrival was “to find friends”. Not being able to make friends after 1, 2, or 3 years at camp must have been a grave disappointment for the children concerned.

Friendship differences among boys and girls

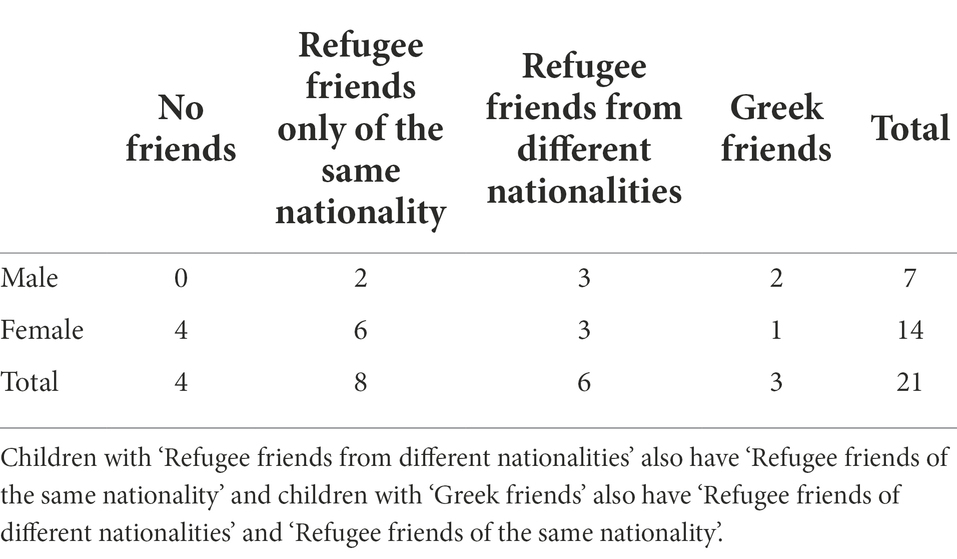

According to the principles of gender mainstreaming (Brauner and Frauenberger, 2014, p. 5), all data in research must be analyzed and presented by gender, therefore it was a research priority, to differentiate our findings among boys and girls (in this research since we refer to children, we specify gender as female and male only). These differences are confirmed in Table 3: girls appear to be monopolizing the category of having ‘No friends’ and form the participant majority of having ‘Refugee friends only from the same nationality’. Girls outnumber boy interviewees, yet they are more boys having Greek friends than girls. These differences seem to reflect the culturally sensitive gender stereotype that girls are more reserved regarding socialization, whereas boys seem to be more outgoing and confident in liaising with children from other socio-linguistic backgrounds, including Greek children. The findings shed light on stereotypic associations that seem salient with respect to the relational choices of our interviewees. Nearly half the girls report having friends only from the same nationality, often ‘one female friend’, who may be a neighbor at camp or a classmate at onsite non-formal classes. An Afghan girl characteristically noted that “My friends only come from Afghanistan and when we are together, we only read or study.” Another 16-year old Afghan girl, reported that she has only one female friend with whom the only joint activity was “to read together.” A 13-year old Afghan girl said in her interview “We do not spend that many hours with friends but the time that we spend together the most we talk about the lessons or classes.” An older Afghan girl, when asked about friends and what they do together, stated that her friends are only Afghan, but “since we are all from family members, our relatives, when I meet my friend, I think that what we all like to do and give us good feeling is just to speak, to talk.” The teenage girl emphasized to the researcher her origin (“I am from family”) and the activity with friends (“we talk”), probably declaring an acceptable social profile within the socio-cultural context for her age and gender.

Boys on the other hand reported a wider circle of friends from all over the camp. As one Afghan boy stated: “I have Afghan, Syrian, Congolese friends.” A refugee camp is a very closed community, despite its size, and this relational context may affect social perceptions and choices, so that teenage girls are confined to a more restricted social role, with past-time activities that are more home-based and conventional. An intermediate factor regarding girls’ socialization is girls’ participation in education. All four children who report having ‘no friends’ are girls that do not attend formal education.

Friendship patterns and age

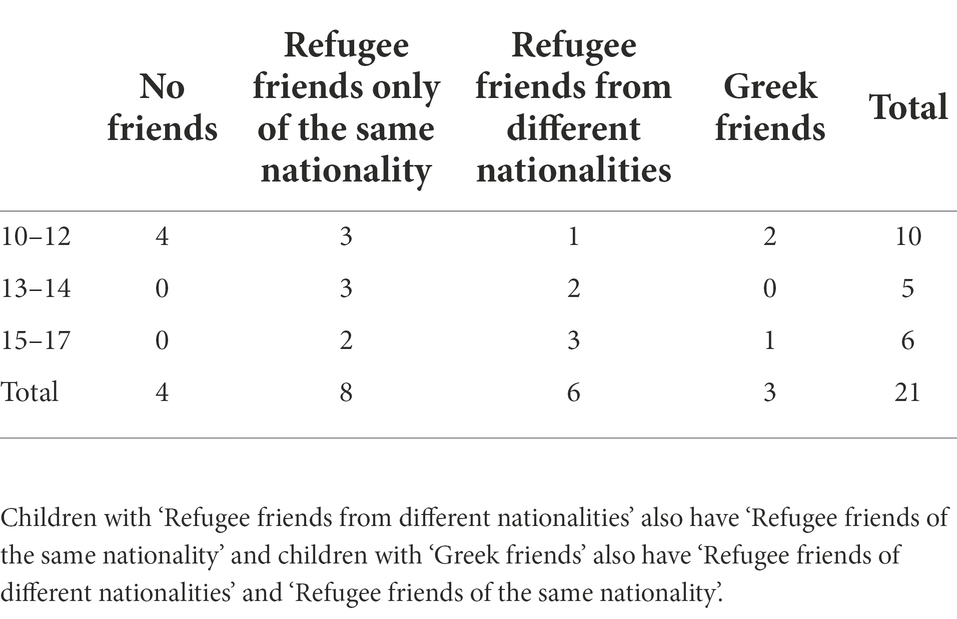

Table 4 presents the age variation, but, as the sample is small, the results in this case are inconclusive. The only notable finding is that it is only the youngest category (10–12 years old) that report having ‘No friends’, even though these children (all girls) had been in Greece for a long time. As age does not seem to produce definite differentiation, formal school attendance is the next factor investigated.

Friendship patterns and school attendance

Unsurprisingly, all children who have Greek friends attend Greek formal school, as this is the only place that refugee camp children are likely to meet Greek peers. At the other end, all children who report having ‘No friends’, do not attend formal education. This significant result, shown in Table 5 is consistent with the fact that during the school process, refugee children are exposed to increased interactions with Greek children, but also refugee children of other nationalities (for example, in the bus, in class, during breaks, during educational trips and sports events etc.). Schooling is the process through which inclusive socialization is more likely to develop and children not attending school seem to be at higher risk of isolation. On the other hand, the issue of xenophobia in Greek schools was also mentioned. One Syrian boy reported that he attended a local formal school but dropped out due to bullying from other students (but he added “They were not Greek”). Two children did not reply to the question if they liked their Greek classmates, although all other children reported that they did. The above results reflect the value of schooling in providing socialization opportunities and mixed interaction among refugee and local communities. It is important to bear in mind that there were ethnic tensions among different refugee communities at camp, especially during periods when hostilities flared in their countries of origin. Some of these tensions were reflected in refugee children’s relations. Half of the participants did not attend formal education, missing out on important years, but it should be noted that the study was carried out during the pandemic, which further hindered access of refugee camp children to formal education (Prekate and Palaiologou, 2021, p. 5).

Apart from the number or type of friendships, it is important to add a final note regarding the quality of these friendships. To the question “Who would you turn for help if you had problems?,” only two teenagers replied: “My friends,” even though adolescence is a period in children’s lives when they form alliances with their peers. Most children replied “My family,” or “DRC employees” or did not reply at all. ‘DRC’ is an abbreviation for Danish Refugee Council, the camp’s administration NGO, but it is unlikely that children would resort directly to its employees for help, as interventions were only applied in communication with the parents. It is possible therefore, that interviewees’ answers were biased in an effort to appease the researchers, whom they saw as ‘authorities’. Another interesting indicator is the type of activities shared with their friends. To the question, “What activities do you do when you are together with your friends?,” one interviewee replied “Talk.” Almost all interviewees replied “Play,” “Do sport” or “Study together.” To look further into the quality of these friendships, level of trust and impact on psychosocial health, more research is required (Table 5).

Interviewees’ comments raised further complications regarding childhood friendships among refugees, issues not normally found in mainstream population. For example, a 13-year old Syrian girl reported that she had made a friend at camp, but her friend was soon relocated in Germany. Most families stay at camp only temporarily and this type of secondary ‘loss’ is something all children learned to live with, as shown in the following interview with a 15-year old Syrian girl:

Researcher: “How do you make new friends? And if yes, what countries are they from?”

Interviewee: “Most of them they traveled. So we have only those two. Um, there was some goods, some Syrians, some, one child. I had one Afghan, but most of them they traveled.”

Relocation to another European country is the primary aim for most families at camp, but the way it happens can also affect beneficiaries’ relationships:

Researcher: “Can you describe us how you spend your day here, in the camp?”

Interviewee: “It’s not that good. I do not hang out that much because people in the community, if I needed the day most of the people are in here, they look more for travel and I do not and I do not try and put them in order to avoid that, I would have to stay away from them. So in that case, I do not hang out that much in the camp. But I do have great friends. I go skateboarding with, I playing football with them. I have more fun with them, with them.”

The above excerpt is from the interview with a 16-year old boy who implied that some people in his community at camp could be thinking of leaving Greece (for another European country) through non-standard, non-official routes, something he wished not to be involved in. Self-protection from traffickers or other networks, affected the socialization choices of teenagers and their families.

Limitations of the interviews study

The sample of 21 students was taken from students attending non-formal English language classes at camp, provided by the administrating NGO Danish Refugee Council for the camp’s beneficiaries. Even though almost all children living at camp attended such classes, even if irregularly, there was still a small, yet unknown, number of children who never registered for formal or non-formal classes. This population was largely inaccessible for research purposes. Further research would be required to investigate the profile of this population (for example, income and socioeconomic status in country of origin) and the reasons behind school drop-out. Some of the reasons that have been suggested are: expectation for relocation, language difficulties, children helping parents with sibling care/housework, stress and trauma. Another issue that required more research concerned the reasons why 8 out of 11 children attending formal school did not have Greek friends. One obvious explanation is the physical remoteness and geographical isolation of the camp, but more thorough research, perhaps involving parents and teachers, could investigate other factors, such as lack of access, linguistic barriers, cultural barriers, xenophobia, lack of inclusion culture at school and in the community, the role of camp accommodation status in stigmatization of refugee children etc. Another point which could improve the rigor of the study could be the inclusion of a control group for comparison, for example, other refugee students living in rented apartments (rather than camps), native students, other minority students (such as Roma). It would also be interesting to examine the correlation between refugees’ Greek language speaking skills and socialization with Greek students, as these two factors appear to feed each other and are both related with inclusion in mainstream education.

Discussion

Adolescence is the period when young people develop a network of peer friendships, which is central to their sense of well-being and self-esteem. Although some children demonstrated intercultural flexibility and openness to creating new friendships from many different nationalities, most children in the study of Skaramagas Refugee Hospitality Center were limited to friendships from their own national/linguistic background or remained isolated. The insights gained from this study provide empirical confirmation that children from disadvantaged socio-economical background, such as refugees, can be deprived socially. Also, formal mainstream education attendance is a necessary condition for building friendships with local communities, but it is not sufficient: specific interventions need to be established to create an inclusive school environment.

Regarding relational differences between boys and girls, schooling assumes a complicated role, both as a cause and a consequence of social interaction (or lack thereof). According to an Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) report, refugee girls’ attendance rates of secondary school lags to refugee boys’ rates, by nearly 10 percentile units (INEE, 2021, p. 15). Cultural restrictions may prevent girls’ participation in formal education classes, especially during adolescence and pre-adolescence. Some good practices in emergency education for refugees recommend girls-only learning spaces, as girls need to have a safe space where they can participate freely without fear of being judged or bullied by boys. Making schools more accessible to girls would help them enhance their social life and establish new patterns of relating, participation and self-affirmation. Furthermore, school interactions involve fellow-students, teachers, school-staff, but also other social institutions, such as museums, environmental awareness centers, examination centers etc., so integration is encouraged in multiple ways. Girls’ poor social lives are one of the side-effects of lacking gender perspectives in education policy making. Gender mainstreaming in education means taking into account gender differences in all phases of defining, planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating policies (EIGE, 2022). For example, hosting refugee families in remote, isolated camps, with no easy access to schools through public transport, prevents teenage girls from attending local high schools, even if cultural inhibitions about mixed classes are overcome. Incorporating gender-responsive interventions, facilitates participation, and socialization influences, individual and community development, while respecting cultural norms, values and behaviors (Šaras and Perez-Felkner, 2018, p. 1). There are additional cultural differences, which in praxis, might be an obstacle for specific gender populations, in this study, female teenagers, to participate at education outside the camp setting: for example, if young women wished to attend formal evening high school (as they are often busy with sibling caring during the day), there would need to be special provisions for their safe transportation to and from school and baby-sitting facilities at camp. According to the socio-cultural approach, such provisions and processes offer opportunities for the individual and collective development of all minorities. Denying such opportunities from girls and young women prolongs divisions and leaves intergenerational transition of such divisions unchallenged.

According to the intersectional approach, other forms of inequality interact with gender differences to result in social isolation (Adaptation Fund, 2022, p. 9). In this context, socialization patterns may be influenced in complicated ways not only by students’ gender, but by ethnicity, socio-economic status (asylum seekers temporarily hosted in a refugee camp), age (pre-adolescent girls versus late adolescent girls), ethnic subgroup cultural norms (for example, Kurdish Syrian girls have different dress codes than Arab Syrian girls), positioning in a household (oldest daughter in a motherless household, undertaking the caring of younger siblings versus younger daughters in a household with both parents), prior socio-economic status in country of origin etc. There were other categories intersecting with the above, including refugee students with learning difficulties and disabilities, but this is an area largely under-researched. Socio-cultural barriers in school enrolment should also be considered through the lens of parental views. If parents undervalue education (for all their children or girls in particular) this will prevent children from accessing the main pathway towards integration (UNESCO, 2007). Teachers, school authorities, and local children’s parents also hold distinct views about children’s friendships, appreciating (or not) diversity. An intersectional approach in research could provide more accurate insights, creating more equitable provisions.

The extent of isolation that some of the interviewed children experienced is worth investigating further, with possible explanations including trauma, community tensions at camp, racism/xenophobia at school, shyness, lack of social or linguistic skills etc. Even though eight out of 11 children attending formal education expressed very positive comments about their relations with Greek classmates, two comments showed that xenophobia does exist. It has been found that negative socialized behaviors, values and biases against refugees, constructed through social norms and contexts, hinder positive intercultural social interaction among refugee/migrant children and native children (Blair, 2020, p. 2). Racist bullying is one way in which such negative biases are expressed in a school context and of key concern to refugee students (Aspinwall et al., 2003, p. 19). As (Samara et al., 2019, p. 4) support, even though friendships are very important for refugee children, they often face difficulties in their initiation and quality.

It may therefore be the case that specific interventions need to be implemented in schools to facilitate and encourage the formation of intercultural friendships. Some school authorities, for example, have concluded on certain good practices, such as organizing a warm welcome at school for refugees, valuing refugee/migrant students in class, assigning a peer/buddy to each refugee child (Candappa et al., 2007, p. 42), while humanitarian organizations routinely use team-building activities to strengthen friendships among refugee children (IMPR, 2015). The newly introduced ‘Skills Workshops’ in Greek formal education also aim at facilitating a safe and friendly school environment, through the development of empathy, conflict-resolution capacities, cooperation, diversity skills. These workshops are not specifically targeted for refugees but involve many activities that allow all students to share personal information with their peers, get to know each other, express their views/feelings/ stories, all of which are building stones to bonding (Gornik and Sedmak, 2021, p. 111).

Appropriate multi-level interventions by educational professionals, school systems and policymakers, should provide relational inclusion activities and practical opportunities for children to socialize. Education affects multiple aspects of children’s lives and this study highlights the significance of education as global care (Sancho Gil, 2018, p. 105). Schooling allows children to develop their thinking, feeling and acting beyond the narrow norms of their cultural barriers, including the way they relate to others. All refugee children should have this opportunity and schools should invest time and energy to acquire a better understanding of the unique educational and behavioral needs of refugee children, especially children at remotely secluded refugee camps. Psycho-social education activities could help prepare the ground for inclusion and team bonding, challenge stereotypes, develop empathy and acceptance. These activities can contribute to a welcoming atmosphere for refugee children and facilitate connection skills for refugee and native children alike. With increasing flows of refugee children, it is becoming more and more important to transform formal educational systems in host countries to friendly environments for the inclusion of all children.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: All data are registered at the official portal of SODANET The Methodological Protocol was approved by the Relevant Committee of Research and Ethics at HOU. RELEVANT LINK: https://doi.org/10.17903/FK2/JAB51L Research Data on Migration and the Refugee Crisis LINK TO THE COLLECTION: https://sodanet.gr/data-services/infographics/migration.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Committee of Research and Ethics at Hellenic Open University (HOU). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was implemented in the frame of the HORIZON 2020 Project MICREATE (Migrant Children and Communities in a Transforming Europe), Coordinator Science and Research Center, KOPER in Slovenia, funded by the European Union under grant agreement No 822664.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank for their assistance Maria Nioutsikou, Skaramagas’ Refugee Hospitality Center administrator, Grigoris Dosios, facilitator and volunteer teacher with Chaidari Municipality, Maria Andreakou, Danish Refugee Council Education Programs Coordinator, as well as Nikos Tampas, Marina Dramouska and Angeliki Ntokou, researchers who conducted the field interviews (data collection), Eirini Kyriazi and Marina Sounoglou who were involved at the transcription process, as well as all professionals who supported the research preparatory work at camp.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adaptation Fund (2022). A study on intersectional approaches to gender mainstreaming in adaptation-Relevant intervention. AFB/B.37-38/Inf.1,17 February 2022. Available at: https://www.adaptation-fund.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/AF-Final-Version_clean16Feb2022.pdf (Accessed October 4, 2022).

Aspinwall, T., Crowley, A., and Larkins, C. (2003). Save the children: listen up! Children and young people talk about their rights in education. Available at: http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/3706/1/Listen-Up-rights-in-Education.pdf (Accessed June 28, 2022).

Blair, M. (2020). The role of reflexive thought in the achievement of intercultural competence. Intercult. Educ. 31, 330–344. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2020.1728093

Brauner, R., and Frauenberger, S. (2014). Gender-Sensitive Statistics: Making Life’s Realities Visible. Vilnius, Lithuania: European Institute for Gender Equality.

Candappa, M., Ahmad, M., Balata, M., Dekhinet, R., and Gocmen, D. (2007). Education and Schooling for Asylum Seeking and Refugee Students in Scotland: An Explanatory Study. Scottish Government Social Research 2007. London, United Kingdom: Institute of Education, University of London. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/198224/0052995.pdf ( webarchive.org.uk) (Accessed June 29, 2022).

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (2022). What is gender mainstreaming. Available at: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/what-is-gender-mainstreaming (Accessed October 24, 2022).

Fasaraki, A. (2020). Skaramagas hospitality center: a case study for education of refugees in the year 2016–2017. Dissertation/Master Thesis. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Available at: https://pergamos.lib.uoa.gr/uoa/dl/frontend/file/lib/default/data/2898770/theFile (Accessed June 27, 2022).

Gornik, B. (2020). The principles of child-centered migrant integration policy. Ann. Ser. historia et sociologia 30, 531–542. doi: 10.19233/ASHS.2020.35

Gornik, B., and Sedmak, M. (2021). “The child-Centred approach to the integration of migrant children: the MiCREATE project” in Migrant Children’s Integration and Education in Europe: Approaches, Methodologies and Policies. eds. M. Sedmak, F. Hernandez-Hernandez, J. Sancho-Gil, and B. Gornik (Barcelona, Spain: Octaedro), 99–118.

Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) (2021). Mind the gap: The state of girls’ education in crisis and conflict. Report on 10 June 2021. Available at: https://inee.org/resources/mind-gap-state-girls-education-crisis-and-conflict?utm_source=INEE+email+lists&utm_campaign=8be3bbb24e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_10_08_10_35_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_710662b6ab-8be3bbb24e-25791567 (Accessed October 5, 2022).

International Middle East Peace Research Project (2015). Improving friendship between refugee children. http://imprhumanitarian.org/en/improving-friendship-refugee-children/ (Accessed June 29, 2022).

Kuschminder, K. (2018). Deciding which road to take: insights into how migrants and refugees in Greece plan onward movement. MPI Europe Policy Brief, Issue No 10. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/MigrantDecisionmakingGreece-Final.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2022).

Palaiologou, N., Kameas, A., Prekate, V., and Liontou, M. (2021). “Refugee hospitality Centre in Athens as s case study: good and not-so-good practices” in Migrant Children’s Integration and Education in Europe: Approaches, Methodologies and Policies. eds. M. Sedmak, F. Hernandez-Hernandez, J. Sancho-Gil, and B. Gornik (Barcelona, Spain: Octaedro), 319–331.

Prekate, V., and Palaiologou, N. (2021). Policies for immigration and refugee education on the lens during COVID-19 times. in 2nd International Interdisciplinary Scientific Conference. (In)equality. Faces of Modern Europe. Available at: https://www.micreate.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Policies-for-immigration-and-refugee-education-on-the-lens-during-COVID-19-times-.pdf (Accessed June 29, 2022).

Prekate, V., and Palaiologou, N. (2022). Refugee students’ psychosocial well-being: The case of Skaramagas refugee hospitality Centre. At multicultural education in an age of uncertainty: Diversity and equity in education. International Online Conference by KAME (Korean Association for Multicultural Education), 19–21. Submitted for publication in Multicultural Education Review 2022.

Samara, M., El, Asam, Khadaroo, A., and Hammuda, S. (2019). Examining the psychological well-being of refugee children and the role of friendship and bullying. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 301–329. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12282

Sancho Gil, J. M. (2018). “Without education there is no social justice” in Políticas públicas para la equidad social. eds. P. Rivera-Vargas, J. Muñoz-Saavedra, R. Morales-Olivares, and S. Butendieck-Hijerra (Santiago de Chile, Chile: Coleccion Politicas Publicas, Universidad de Santiago de Chile), 103–112.

Šaras, E.D, and Perez-Felkner, L. (2018). Sociological perspectives on socialization. Oxford Bibliographies, 28August 2018.

Sirius Watch (2018). Role of non-formal education in migrant children inclusion: links with school. Synthesis report. Available at: https://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/SIRIUS-Watch_Full-report-1.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2022).

UNESCO. UNICEF (2007). A human rights-based approach to education. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/619078 (Accessed Novemebr 10, 2022).

UNICEF (2017). Children on the move in Italy and Greece: Report, June 2017. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/201710/REACH_ITA_GRC_Report_Children_on_the_Move_in_Italy_and_Greece_June_2017.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2022).

UNICEF (2021). Refugee and migrant response in Europe: Humanitarian situation report, No 38 (reporting period: 1 January to 31 December 2020). Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNICEF%20Refugee%20and%20Migrant%20Crisis%20in%20Europe%20Humanitarian%20Situation%20Report%20No%2038%20-%2031%20December%202020.pdf (Accessed June 20, 2022).

Keywords: gender differences, child friendship, refugee inclusion, multicultural friendships, refugee socialization

Citation: Palaiologou N and Prekate V (2023) Child friendship patterns at a refugee center in Greece. Front. Educ. 7:982573. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.982573

Edited by:

Juana M. Sancho-Gil, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Caroll Dewar Hermann, North West University, South AfricaMaria Peix, Barcelona Provincial Council, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Prekate and Palaiologou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Viktoria Prekate, dnByZWthdGVAZ21haWwuY29t; Nektaria Palaiologou, bmVrcGFsYWlvbG9nb3VAZWFwLmdy

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Nektaria Palaiologou*†

Nektaria Palaiologou*† Viktoria Prekate

Viktoria Prekate