- 1Department of Education and Sports Science, Faculty of Arts and Education, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 2Centre for Studies of Educational Practice, Faculty of Education, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Hamar, Norway

Blended learning environments have become increasingly common during the past few years, and frequent access to digital technologies has influenced many areas of learning and classroom interaction. This paper investigates teacher-pupil and pupil-pupil communication and collaboration practices in a leading-edge Norwegian primary school. In this small-scale case study, seven teachers were interviewed individually and in their respective grade level teams, and two grade levels were observed for a 4-week period to find out how teachers in technology-rich classrooms utilize and consider the role of digital technologies in everyday communication and collaborative processes. Teachers’ overall perception in this study was that digital technologies are useful in communication and collaboration and thus, digital elements were frequently incorporated in their everyday classroom practices. However, the results also imply that while blended learning environments have opened new avenues for collaboration and communication happening parallel in physical and digital learning arenas, there is a lot of variation in how teachers guide their pupils in collaboration and communication and how digital technologies are utilized in such contexts. Particularly the comparison between proactive and reactive approaches to instruction regarding communication and collaboration indicates that explicit guidance in such processes can have a positive influence on the pupils’ group dynamics and effectiveness. Meanwhile, some of the benefits of supporting the act of collaboration and communication among pupils in a blended learning environment remained unexploited.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a growing interest in research investigating online communication and collaboration. However, as technology has become increasingly accessible in the majority of Norwegian classrooms, shifting between physical and digital learning spaces, as well as working parallel in both, has become rather common. This kind of approach is often referred to as blended learning or blended teaching (Nemiro, 2021; Yang et al., 2022). The purpose of this article is to investigate teachers’ perceptions and practices in relation to computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) and communication in technology-rich classroom settings, in which pupils and teachers share the physical learning arena and use digital technologies as a natural part of their daily teaching and learning processes. A perspective common to CSCL and communication research is investigating the advantages and challenges information and communication technologies (ICT) bring to ordinary schools, where the digital dimensions are rarely systematically prioritized and worked on (Sung et al., 2016; Blau et al., 2020; Midtlund et al., 2021; Nemiro, 2021). The sample for this study consists of teachers working in a leading-edge (Schofield, 1995) primary school, where staff training and access to a variety of educational technologies have been prioritized significantly over the past years. Therefore, these teachers have the competence and resources to utilize technology in innovative and creative ways to support the aims of the newly reformed national curriculum. Due to these circumstances, their perceptions can be considered highly valuable when reflecting on previous studies and specifically the challenges raised in them. This article discusses how these primary school teachers facilitate communication and collaborative learning in blended learning environments with the help of digital technologies.

Literature review

When examining and discussing communication and collaboration in technology-rich classrooms, several concepts of relevance intertwine. Communication and collaboration are some of the so-called 21st century competencies. The influence of digital technologies in communication has been significant in our society in general, and schools are no exception. This has presented new ways for collaboration as well, as digital competence and access to a variety of digital technologies can enhance and transform interaction between teachers and pupils in many ways. CSCL allows pupils to operate in physical and digital learning spaces simultaneously, which brings us to the concept of blended learning–an approach that integrates many elements of digital technologies with more traditional face-to-face learning.

Communication and collaboration in the 21st century

Communication as a concept has gained various definitions over time. At its simplest, communication can mean the process of interaction (Farrell, 2009, p. 5). Some common principles of communication are useful when framing the concept in a classroom context in particular (Farrell, 2009): communication is context-dependent, involves mutual influence (awareness, acting, and reacting), consists of verbal and non-verbal messages, and is in a constant change. During the recent decade, one of the most significant changes has been the increase of digital technologies in classrooms and rapid changes in digital advancements (Ferrari, 2013). When referring to 21st century competences, communication and collaboration are almost without exception mentioned as central skills, together with ICT-related competences, regardless of the study or framework (Voogt and Roblin, 2012; Mishra and Mehta, 2017; Redecker, 2017; van Laar et al., 2017; van de Oudeweetering and Voogt, 2018). Previous research and policy documents consider new approaches and opportunities to communication and collaboration as some of the definite advantages of educational technologies (Voogt and Roblin, 2012; Jewitt et al., 2016; van de Oudeweetering and Voogt, 2018). Such findings have also been echoed in other policy documents and research, such as the Norwegian national curriculum (Norwegian National Directorate of Education and Training, 2021), and Professional Digital Framework for Teachers (Kelentrić et al., 2017; Blau et al., 2020; Nemiro, 2021). While some of the relevant educational research from recent years investigates and highlights the potential of online communication and collaboration in particular, the opportunities are certainly not limited to interacting from distance. In many contemporary classrooms, teachers and pupils shift frequently and effortlessly between digital and physical learning arenas and communicate parallel in both. Employing digital technologies in everyday learning has been found to spark playful learning, increase motivation and engagement, and enhance pupil interest (Bebell and Kay, 2010; Hur and Oh, 2012; Harper and Milman, 2016; Gouseti et al., 2020), and therefore offers many exciting opportunities for improved communication and collaboration practices.

However, utilizing digital technologies in pupil interaction in a way that contributes toward developing communication and collaboration skills can be challenging. In fact, the speedy development of digital technologies and new demands for teachers facilitating learning with the help of digital technologies requires constant professional development and other commitments from teachers’ professional community (Blikstad-Balas and Klette, 2020; Johler et al., 2022). Many teachers lack the competence and resources in terms of educational technologies and thus, the potential of digital technologies often remains untapped (Krumsvik et al., 2016; Blikstad-Balas and Klette, 2020). It is still common that the development of more innovative and smooth communication and collaboration practices is dependent on a few enthusiastic staff members (Gouseti et al., 2020), so-called front runners (Rogers, 1995), meaning that potential best practices often remain local and short-term. Teachers can also struggle to see the opportunities and advantages of using digital technologies for collaboration and communication when all pupils and teachers are gathered in the same physical space (Midtlund et al., 2021). Such issues lead to significant variations in how digital technologies are utilized in classrooms, differing from school to school and even from teacher to teacher (Krumsvik et al., 2016; Fjørtoft et al., 2019; Moltudal et al., 2019). Developing pupils’ communication and collaboration skills in a rapidly digitalised and developing world is not only necessary but a prerequisite for becoming a citizen who participates and contributes to a society. Therefore, it seems important to learn more about the influence and potential of digital technologies in pupil-pupil and teacher-pupil interaction. Nevertheless, it is common that rather than explicitly teaching efficient collaboration and communication strategies with the help of digital technologies, teachers instead just “let” collaboration happen. The focus tends to be on the digital products, rather than the process of communication and collaboration itself (Midtlund et al., 2021).

Collaborative learning

Collective aspects of learning have a central role in socio-cultural learning theories (Vygotsky, 1978) and collaborative working methods in education have gained significant footing in 21st century curricula. Collaboration can be understood simply as active engagement and interaction within a group of people, with the aim of achieving a common goal (Nokes-Malach et al., 2015) but the wide spectrum of definitions, interpretations, and implications of collaborative learning in 21st century curricula has led to few systematically integrated and assessed collaborative practices (van de Oudeweetering and Voogt, 2018). In their synthesis investigating the advantages and disadvantages of collaborative learning, Nokes-Malach et al. (2015) found reports of many cognitive advantages in collaborative learning. For example, increasing working memory resources (Kirschner et al., 2009), incorporation of complementary knowledge and error-correction (Johansson et al., 2005), and supporting relearning through re-exposure and retrieval (Roediger and Karpicke, 2006; Rajaram and Pereira-Pasarin, 2010) have all been found beneficial to learning. From a social learning perspective, observational learning (Craig et al., 2009), negotiating multiple perspectives (Kuhn and Crowell, 2011), construction of common ground (Nokes-Malach et al., 2012), and increased engagement (Johnson and Johnson, 1985) have been considered some of the benefits of a collective learning approach. However, group work and other collaborative working methods are not a default recipe for success, as research also finds that the method has its disadvantages. Fear of being negatively evaluated by peers can hinder one from voicing and developing their ideas (Mullen, 1987) and “freeloaders” expecting the rest of the group to do the work are not uncommon phenomena in collaboration (Karau and Williams, 1994; Le et al., 2018). Different ways of organizing and retrieving knowledge can disturb cognitive processes (Kirschner et al., 2009; Nokes-Malach et al., 2012) and having to wait for one’s turn to speak, negotiate next steps, and give or receive help have generally been found challenging without explicit instruction and guidance regarding collaboration (Diehl and Stroebe, 1988; Le et al., 2018).

While a variety of approaches for effective development of collaborative skills can be identified, previous research shares the view that collaborative skills do not spontaneously develop merely by working in teams, but that they must be consistently and explicitly cultivated (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995). Tammi and Rajala (2018) suggest incorporating deliberative communication as a part of classroom communication and collaboration routines. In their research, they found that having explicit focus on discourse that allows participants to think, listen, discuss, and criticize different viewpoints and arguments in a respectful and constructive manner led to more participation and learning of negotiation skills, while exploring the social, collective, and cognitive aspects of classroom interaction. Previous findings also indicate that such an approach works already in early primary school age, when collaboration is mediated through structured discourse (Chen et al., 2015). Sjølie et al. (2021) highlight the importance of task design with an explicit focus on skills relating to collaboration and reflection as learning goals. This requires a safe learning environment where a teacher can facilitate different aspects of interaction. As collaboration skills consist of many different dimensions, such as cognitive, social, communicative, and motivational (Meier and Spada, 2008; Diziol and Rummel, 2010), Deiglmayr and Spada (2010) suggest deciding in advance which element(s) to focus on, instead of solely having collaboration in general as a learning goal. Nemiro (2021) found that assigning different roles to pupils and discussing collaborative behaviors and conflict resolution approaches explicitly can be effective strategies in focusing on developing pupils’ collaboration skills.

Computer-supported collaborative learning

When digital technologies are used in collaborative learning processes, the term CSCL is often applied. Such learning situations are characterized by not having to choose between face-to-face approach or online encounters but being able to take advantage of both approaches simultaneously (Yang et al., 2022). For instance, in a collaborative project, face-to-face discussions may be supplemented with interactive whiteboards, wikis, and other types of digital communication tools that support and expand face-to-face communication and collaboration practices (Vaughan et al., 2013). Additionally, Roschelle (2021) suggests that employing digital technologies to automate and assist in some of the routine aspects of the work helps raise awareness of the key concepts and other valuable aspects during the process of collaboration. A common characteristic of a CSCL approach is the notion that the whole collective process of meaning-making and problem solving is of critical interest, rather than only the final learning outcomes (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995; Koschmann, 2001; Stahl et al., 2014). Using digital technologies, for example robotics, in collective meaning-making processes has been found useful in rehearsing competences needed for effective collaboration (Del-Moral-Pérez et al., 2019; Sung et al., 2022). However, much of the research about CSCL still tends to rely on conventional learning outcomes, rather than constructing an understanding about negotiation, collaborative knowledge building, and dialog (Stahl, 2015). Previous studies report that pupils are often unable to regulate their collective learning processes when left on their own with digital devices, and that productive social interaction for a common goal requires a thorough and careful design and application of CSCL (Koschmann, 2001; Järvelä and Hadwin, 2013).

Blended learning

Blended learning and blended teaching refer to an approach that takes advantage of opportunities to utilize digital and traditional learning materials, methods and environments simultaneously (Deschacht and Goeman, 2015). Further framings vary, but in their synthesis of different definitions of blended teaching and learning, Yang et al. (2022) define the following four dimensions as central elements of blended learning:

(1) Combines online and traditional learning

(2) Mixture of learning modes–teacher-led and pupil-led–that occasionally also merge

(3) Learning environment: not only digital or physical but a combination

(4) Combines several teaching methods to develop a variety of pupil skills

Furthermore, blended learning environments are often characterized by flexibility and personalization of the learning experience, highlighting pupils’ own initiative and opportunities to influence their learning path (Pulham and Graham, 2018). Blended learning also tends to embrace the principles of mastery-based learning, allowing pupils to pace their learning to fit their own tempo. Grouping pupils for projects, discussions, or short-term activities is another common setting for using blended learning, while opportunities for collaborative learning approaches are rare in typical online learning (Pulham and Graham, 2018; Graham et al., 2019).

Norwegian context

Norwegian schools and curricula are no exception to promoting education in terms of collaborative working methods. The Norwegian national curriculum expects teachers to employ collaborative working methods in their classrooms at all levels of schooling. This highlights how such an approach can foster and promote creativity and versatility for pupils of all ages, as well as teach them to listen to others and voice their own insights in a constructive way (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019). Digital technologies offer significant contributions toward communication and collaborative learning practices, and teachers are expected to incorporate opportunities for interaction in digital arenas in their teaching (Kelentrić et al., 2017). This requires extensive digital competence from teachers, who must keep themselves up to date with the advances of digital technologies and the new opportunities they offer for the teachers and their pupils (Johler et al., 2022). It is worth noting that employing digital elements for communication and collaboration does not necessarily mean that the interaction happens solely in a digital space. Indeed, digitally competent teachers can incorporate collaborative learning methods and digital elements in learning activities that take place in the same physical space (Vaughan et al., 2013; Pulham and Graham, 2018; Yang et al., 2022). This article delves into the potential and challenges presented in such contexts, as well as other aspects that invite blended learning approaches for collaborative learning and communication in technology-rich classrooms.

Method and analysis

Design and sample

The aim of this study was to investigate collaboration and communication practices in blended learning environments. As the focus lies on exploring the potential, possibilities, and inherent pitfalls of digital technologies in classroom interaction, rather than describing the current state of affairs in an average school, the main principles of purposeful sampling (Bryman, 2016) were applied when selecting informants for this case study. Teachers in one Norwegian primary school were chosen to be studied in this research project. The school they were employed at can be defined as a leading-edge school (Schofield, 1995) due to its significant investments in training teachers in professional digital competence and educational technologies since it was founded several years ago. For instance, each classroom is equipped with a projector and a personal device for all pupils and teachers. The school also has a wide array of other types of digital technologies available, such as a podcast studio, green screen technology, and a variety of robotic technologies and miniature computers. It was also of interest to find a primary school to study, as digitalization is a newer phenomenon in primary schools. This is also why much of previous research within the theme focuses on secondary and tertiary education. At the time when this study was carried out, all informants worked at this leading-edge school. Seven teachers participated in interviews and observation, and 20 teachers submitted their survey answers. The data presented in this article is drawn from a larger case study, investigating the influence of digital technologies in teacher’s role and pedagogical practices in general. The study is defined as an intrinsic case study (Stake, 1995), due to the substantial interest in this specific case and what can be learned from these particular teachers.

Instruments

To find out how teachers perceive the influence of digital technologies in terms of collaboration and communication in blended learning environments, seven teachers in a Norwegian leading-edge school were interviewed individually, thereafter observed over a 4-week period, and finally interviewed in focus groups in their respective grade level teams (grade 1 teachers together and grade 5 teachers together), before executing a whole-school survey. The survey was implemented after a tentative analysis of interview and observation data, in order to validate findings deduced from qualitative data, as well as to gain additional and more collective data from teachers of all grade levels (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015; Bryman, 2016).

Individual interviews

To start off the project, seven teachers working in grades 1 and 5 were interviewed individually. The length of the interviews ranged from 35 to 45 min. A semi-structured interview design (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015; Bryman, 2016) was chosen, as it enabled a flexible and abductive dialog between the interviewer and the interviewees (Appendix 1). This allowed the interviewees to answer the questions, as well as share their views of other related topics regarding technology-rich classrooms, in order to assist in constructing a holistic, in-depth understanding of their perceptions. With the help of results from the individual interviews, it was possible to learn about the competence of the teachers being observed, as well as get acquainted with their beliefs, approaches and practices regarding communication and collaboration in their technology-rich classrooms.

Observation

The main source of data for this article is the data collected during the observed lessons, mainly in grades 1 and 5. During a period with a duration of 4 weeks, 56 lessons were observed, each lesson lasting 63 min on average. The type of observation practice applied in this study was predominantly non-participant (Creswell and Guetterman, 2021) but over the weeks, as the observer, pupils, and teachers grew more acquainted, the pupils began to try to involve the observer in their activities. While engaging in a more intense dialog with a small group of pupils could offer a more in-depth understanding of a series of approaches and processes, the trade-off was that the observer’s attention was focused on a small group of pupils, and thus, the rest of the events in the classroom could not be recorded. A combination of both practices could, however, offer an overview and comprehensive information about certain approaches and processes (Bryman, 2016) and was therefore applied especially when observing repeated lessons (same lesson plan taught to two or three different groups of pupils). A common but somewhat challenging aspect of observation as a data collection strategy is that recording what is happening in a classroom often requires simultaneous interpretation at some level (Stake, 1995; Bryman, 2016). To address this challenge, a semi-structured observation guide (Appendix 2) was developed using national policy documents [e.g., Norwegian national curriculum and PDC Framework by Kelentrić et al. (2017)] and recent results from relevant research and 21st century competence frameworks (e.g., Voogt and Roblin, 2012; van Laar et al., 2017; van de Oudeweetering and Voogt, 2018) to frame the contents of the lessons in different categories. Using the categories to record observations and note questions and tentative interpretations made the otherwise seemingly unstructured observation situation more organized and orderly and was later also applied in the analysis of the data. Furthermore, in intrinsic case studies that engage with new a phenomenon, it is often advantageous to develop tentative interpretations of the data early on, to get a more comprehensive understanding of what is happening and to be able to adapt the data collection process, should the need arise (Stake, 1995). This principle was applied when having completed the individual interviews and observation period and preparing for the focus group interviews with each grade level team.

Focus group interviews

In this study, focus group interviews offered an opportunity to discuss the individual interview results, observations, and questions that arose during the observations. The questions in the focus group interview guides (Appendix 3) were based on recorded observations during lessons and brief discussions with the participating teachers during and between lessons. This step of the cumulative data collection process was considered necessary in order to confirm or abandon tentative interpretations to avoid misconceptions and thus, increase the validity and reliability of the results. Focus group interviews also offered a more collective view on the topics at hand (Bryman, 2016; Creswell and Guetterman, 2021).

Survey

The final step of the data collection process, the survey (Appendix 4), was administered after a tentative analysis of interview and observation data. Its function was two-fold: first, to collect more representative data to confirm or refute the interpretations and conclusions from the other data (Maxwell, 2010) and second, to find new perspectives and dimensions in the existing data (Hesse-Biber et al., 2015). The survey was sent to all teachers working in the school in question, and all teachers who were in-service at the time of the survey submitted their answers. The survey consisted of 56 questions regarding the teachers’ beliefs, experiences, and practices, of which 14 were open-ended and 42 multiple-choice questions.

Analysis

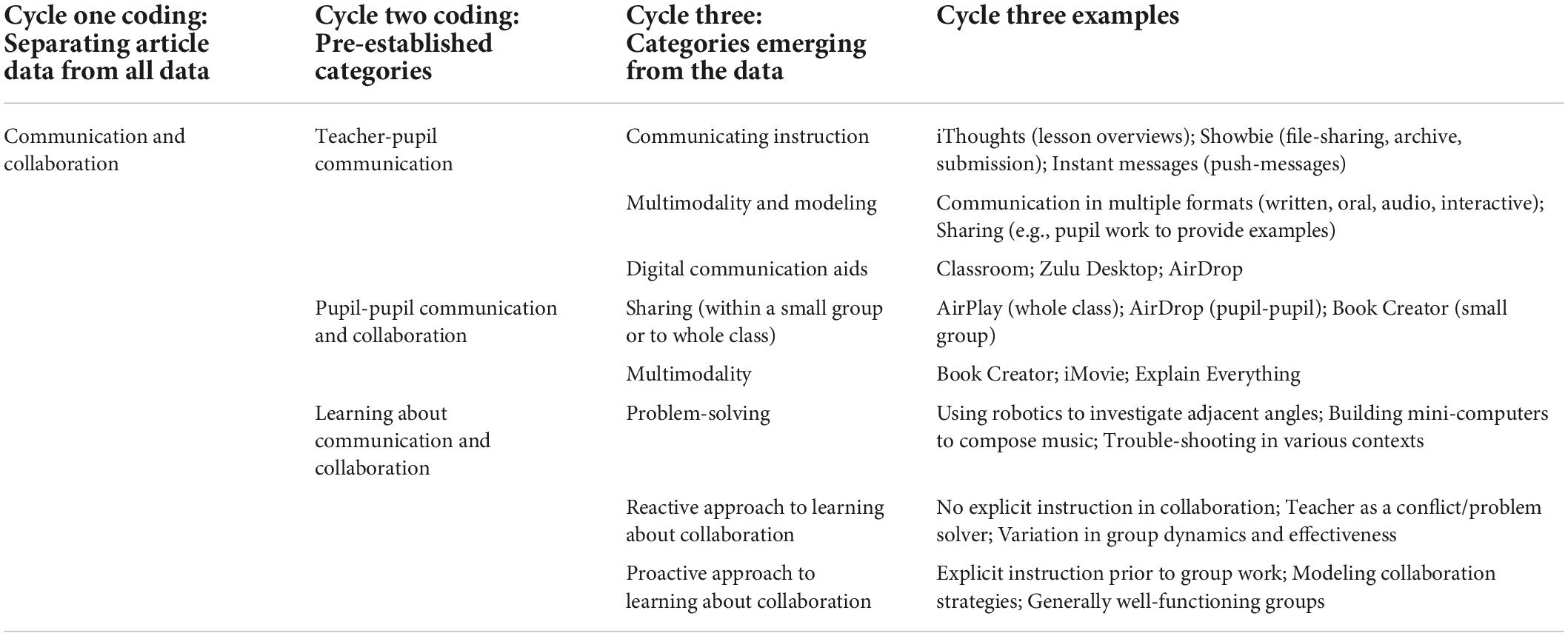

All data was coded following the main principles of a thematic analysis (Bryman, 2016; Creswell and Guetterman, 2021). Coding was divided in three cycles (Saldaña, 2021): first to separate relevant data from other data collected in this case study; second, to code the data according to pre-established categories based on relevant research, frameworks, and policy documents mentioned above; and third, to establish new categories that emerged from the data itself. The cycles are presented in Table 1.

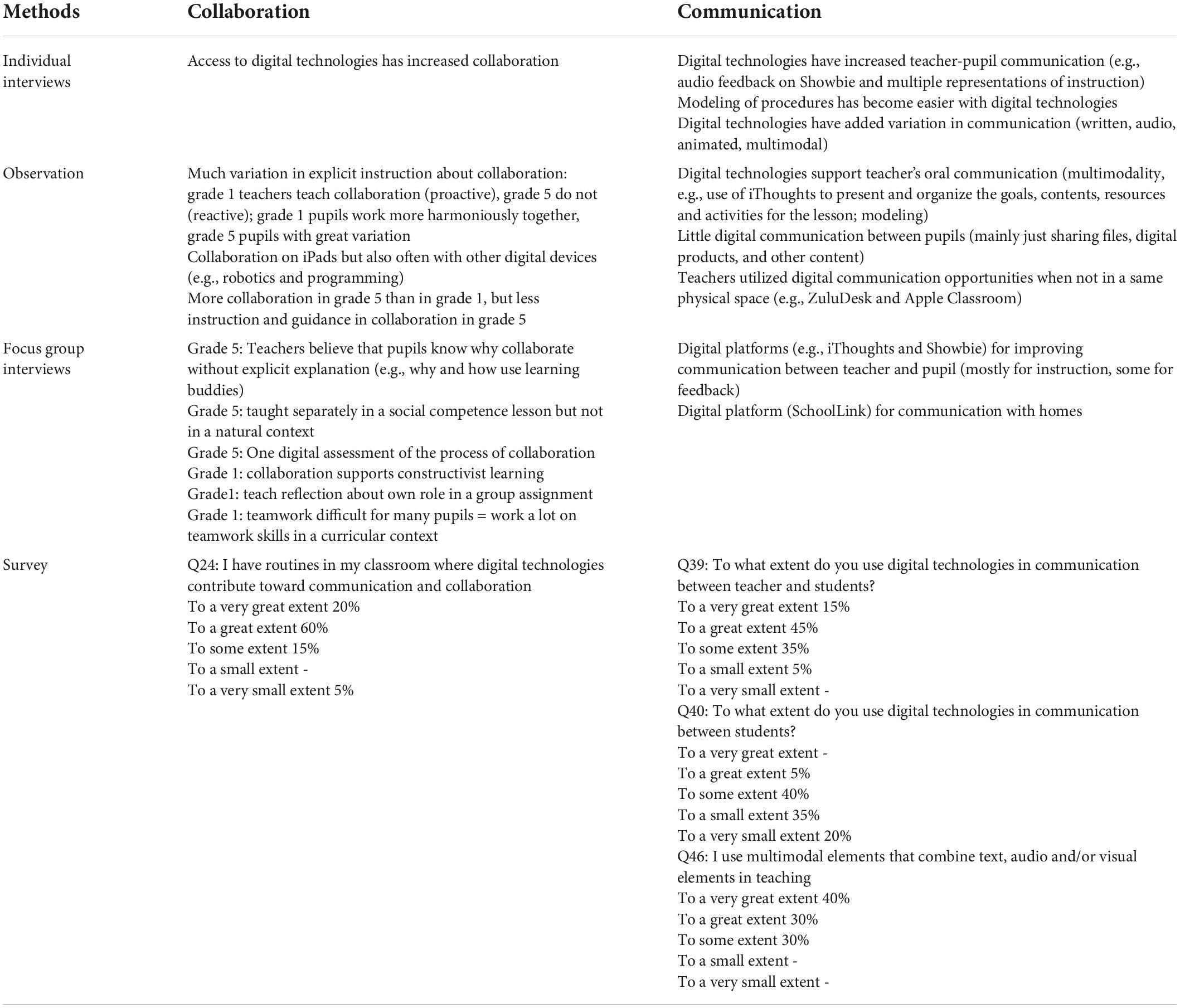

Interview and survey data were collected in a digital format and then organized and analyzed using mainly NVivo. The observation sheets were filled in manually and contained a lot of data, among others questions, ponderings, tentative interpretations and details, which is a common aspect of unstructured observation (Creswell and Guetterman, 2021). These observation sheets were coded manually and supplemented with research notes and reflections during the analysis. Tentative analysis of the data began early in the data collection process, allowing for a cumulative process during which previously collected data guided the following steps of data collection. This abductive process built on the abovementioned policy documents, frameworks and research. Once all data had been gathered and analyzed, an overview of the results was organized in a table format (Table 2).

Results and discussion

Overview of the results

Overall, the teachers’ perceptions of the influence of digital technologies in terms of collaboration and communication were generally positive. They found that digital technologies had increased teacher-pupil communication and collaborative learning among pupils. The results indicate that digital technologies support communication and collaboration in these blended learning environments mainly in three ways: digital technologies were used as a direct tool for communication, digital technologies were used as a mediator in collaborative activities and learning processes, and digital technologies were used to collectively create digital products.

Communication in a blended learning environment

In the survey, 80% of the teachers reported having routines where digital technologies contribute toward communication and collaboration to a great or a very great extent. 15% had implemented such routines to some extent, and 5% to a very small extent. In terms of teacher-pupil communication, the most common way of employing digital technologies in communication was teachers communicating instruction and feedback to pupils. Showbie was used for this purpose in 17/56 observed lessons, and iThoughts in 38/56 lessons. Most often these platforms supported teachers’ oral instruction, but in grade 5 they were occasionally used as the sole source of instruction when returning to a previously introduced topic. Teachers found these platforms particularly useful because of their accessibility and many opportunities for communicating with their pupils in writing, recorded audio files, and multimodal representations. They noted that this led to more versatile communication between teachers and pupils. In fact, all teachers in this school took advantage of multimodal features in classroom communication: 70 % of them to a great or very great extent, and 30% to some extent. Using multimodal elements in classroom communication can have many advantages, as it offers multiple avenues for the same message, allowing pupils to better understand instruction and also express themselves in various ways (Jewitt et al., 2016). Teachers could also use applications to send push-messages to pupils’ screens while not sharing a physical space, for example, when pupils were allowed to work in the hallway or library. Finally, teachers found that digital technologies allowed them to model a variety of practices to their pupils more frequently and ergonomically than what would have been possible without access to projectors and screens.

Teachers reported that digital technologies were rarely used for communication among pupils during instruction time: only 5% used it for this purpose to a great or very great extent. 55% of the teachers employed digital technologies for pupil-pupil communication to a small or very small extent. Understandably, when sharing the physical learning space, simply talking to each other can often be the easiest and most powerful means of communication. However, as pointed out by Deschacht and Goeman (2015) and Yang et al. (2022), the basic principles of blended learning in technology-rich classrooms give us the freedom to combine digital and non-digital means of communication. While having a verbal dialog in person can certainly be considered a sensible choice of communication in a classroom, interactive platforms and tools can support this communication (Stahl, 2015; Roschelle, 2021). Furthermore, digital technologies can bring new dimensions to the traditional dialog and help pupils organize and negotiate their views more efficiently (Vaughan et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2022). The scarcity of examples in this study, which took place in a leading-edge school, implies that understanding how digital technologies have influenced and can further influence communication is something that may require more awareness and discussion. Blended learning environments and CSCL certainly do not exclude face-to-face communication but rather highlight the potential advantages of digital technologies in elevating such dialog and discourse.

Collective learning activities with computer-supported collaborative learning

While digital technologies were rarely used for direct communication among pupils in the observed classrooms, using technology in collaborative assignments was far more common. In such cases, the role of digital technologies was often being the main learning activity, during which pupils worked together in collective meaning-making and solving a mutual problem (Stahl, 2015). In grade 1, for instance, a collaborative project about algorithmic thinking and programming was carried out to teach the pupils some basic skills about coding, but simultaneously, collaboration was an obvious learning goal. After being introduced to the basic principles of coding unplugged, the pupils used robotics to practice what they had learned. Prior to the activity, the teacher modeled good collaborative practices with some of the pupils, in order to demonstrate turn-taking and negotiation strategies. Bluebots were employed in collective learning activities to rehearse problem-solving, storytelling and spelling in various ways, and pupils also got to experiment with them rather freely in pairs or small groups before setting to a task. Building communication and collaboration skills through digital technologies in general, and robotics in particular, has been found beneficial in developing different roles in teams, rehearsing effective communication and conflict-resolution strategies, sharing between students, and relationships between pupils and teachers (Del-Moral-Pérez et al., 2019; Nemiro, 2021; Sung et al., 2022). The grade 1 teachers in this study seemed to employ digital technologies rather successfully, in order to teach and reinforce the abovementioned competences by having an explicit focus on specific areas of communication and collaboration throughout the collective processes, much like in the recommendations of for example Deiglmayr and Spada (2010) and Järvelä and Hadwin (2013).

In examples from grade 5, pupils for instance explored the relationship between adjacent angles by coding and experimenting with robots (Sphero Balls), and composed music using miniature computers (micro:bit). In the Sphero lesson, pupils worked either in pairs or teams of three, and coded Shero balls to explore and experiment in mapping out properties of adjacent angles. When making music in groups with micro:bit, pupils initially used sensors and other components of micro:bit to first assemble miniature computers, and then experimented with coding in order to compose their own melodies, as well as some simple versions of popular musical pieces. In their Norwegian classes, traditional book reports were replaced with podcasts during the observed unit. The podcasts were prepared, recorded, and evaluated in groups of 3–4 pupils, and as this was the first time the students were working at the podcast studio, teachers assisted them rather much with the practical aspects of it.

During all these projects it was evident that the teachers’ choice to use of a variety of educational technologies in an exploratory way sparked motivation, engagement and pupil-initiative, which is in line with previous research findings (Bebell and Kay, 2010; Hur and Oh, 2012; Del-Moral-Pérez et al., 2019). While the pupils were not explicitly guided in negotiation and other forms of communication in grade 5, such an approach highlighted the role of digital technologies as a mediator (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995). Pupils worked toward solutions through experimentation by trying out a variety of ideas and adapting their interpretations as they proceeded. From a learning perspective, reflection and meta-discussions about the process can be considered crucial (Deiglmayr and Spada, 2010; Mishra and Mehta, 2017; Sjølie et al., 2021), and while some discussions were definitely happening during the negotiations, teachers prompted few initiatives to boost these elements. During these lessons, teachers set the framings, helped with practical aspects, and interfered when needed, but the learning activities were mainly pupil-led. This allowed the pupils to choose and combine a variety of skills, which Pulham and Graham (2018) and Yang et al. (2022) find as some of the defining factors in blended learning. However, while digital technologies mediated collaboration, pupils’ collective processes were rather unstructured and varied greatly from group to group. One can ask if more proactive teacher involvement, and guidance in the act of collaboration in grade 5 could have increased the impact and thus, lead to more effective collaboration processes.

Computer-supported collaborative learning in creating digital products

While innovative, exploratory, and fabrication-focused aspects of educational technologies are often highlighted, an important part of creating something new is the ability to have some mastery of foundational knowledge first (Mishra and Mehta, 2017). During the observation period, also more traditional collaborative projects–among more contemporary approaches–were carried out particularly in grade 5, with a less explorative approach and more conventional reproduction of knowledge involved. In such projects, the pupils were often given a topic and access to the Internet in general or specified digital resources, to find relevant information about their topic. At the end, they created a digital product, such as a digital poster or video clip, in groups of 2–4 pupils, in order to demonstrate their learning. In some assignments, the teachers introduced a variety of presentation opportunities, for example green screen technology, to stimulate curiosity and motivation, as well as to demonstrate learning and presenting in alternative ways that take advantage of multimodality. In general, the teachers were very supportive of multimodal elements in pupils’ work, which has been suggested to guide meaning-making through communicating in a variety of ways (Jewitt et al., 2016). However, many of the pupil demonstrations of multimodality in joint efforts were rather monotonous and repetitive, despite the frequent use of multimodality and collaborative digital platforms by both pupils and teachers. For example, Book Creator was used on several occasions for creating digital products collectively, but nevertheless, the pupils had a tendency to use a recurring formula of putting together text, an audio sample, and matching images. Little experimenting and creativity was observed regarding how a group of pupils could utilize the platform to make a different type of a multimodal product or how the platform could contribute to the act of collaboration itself.

When creating a digital representation of their learning, pupils can benefit from effective communication strategies, in order to produce informative–and perhaps even creative–products in a given time frame. However, the teachers rarely spent instruction time on proposing strategies for improving communication amongst the pupils before setting to a task or while working on the digital products, as suggested for example by Tammi and Rajala (2018), Nemiro (2021), and Sjølie et al. (2021). From a technology-specific perspective, the pupils had some difficulties deciding whose device to use for certain steps of the project, as well as in taking advantage of the potential opportunities digital technologies enable in blended learning situations, such as using digital technologies assisting in communication and utilizing the opportunities they offer specifically in collaboration (Deschacht and Goeman, 2015; Roschelle, 2021; Yang et al., 2022). In the light of previous research findings, this is not surprising, as leaving pupils alone on their devices in has been found somewhat counterproductive (Koschmann, 2001; Järvelä and Hadwin, 2013). One can speculate that more focus on for example negotiation and conflict-resolution strategies (Nokes-Malach et al., 2012; Tammi and Rajala, 2018) could have enriched the final product, as well as allowed pupils to communicate and develop their ideas, questions and criticism to other pupils and teachers in a more constructive and effective manner. However, the approach often chosen in grade 5 allowed the pupils to use a variety of skills that allowed them to highlight their strengths and have a lot of influence in the final product, which Pulham and Graham (2018) and Yang et al. (2022) consider as some of the main characteristics of blended learning. At the same time, Roschelle and Teasley (1995), Koschmann (2001), and Stahl et al. (2014) find that often too much emphasis in CSCL-related learning activities is placed on the product and too little on the process of collaboration itself. One could perhaps conclude that while on the way, the full potential of digital technologies was not exploited in this context.

How to learn to collaborate

In the teacher interviews and survey, teachers found that digital technologies did not only increase the amount of collaboration but also streamlined the process through the ease of sharing and finding different ways to work and present results. However, the approach to collaboration varied greatly between the two observed grade levels, and occasionally also among teachers working at the same grade level. While grade 1 teachers generally taught explicitly and repeatedly how to work collaboratively in context with other curricular activities, in line with the recommendations of for example Roschelle and Teasley (1995), Tammi and Rajala (2018), and Sjølie et al. (2021), grade 5 teachers had a more implicit approach to teaching collaboration. In grade 1, before the pupils were divided into pairs or groups, teachers discussed roles, negotiation strategies, and problem-solving approaches with them. Teachers were conscientious about the role technology played in the collective learning activity and occasionally exemplified how collaboration might look in the task at hand. Following in the footsteps of Roschelle and Teasley (1995), grade 1 teachers had explicit focus on how to achieve new understandings in technology-rich learning environments, instead of solely focusing on what was learned, and the approach to teaching competencies crucial for collaboration was overall proactive.

“We really work a lot on collaboration. Collaboration is very difficult for many.— It would never work out to just send first grade pupils off to work together.”

(Teacher A, grade 1, focus group interview)

In grade 5, the teachers’ approach was generally more reactive: once pupils were presented with a task, they were commonly sent to work in their respective groups without discussing the act of collaboration explicitly. When asked about this approach during the focus group interviews, grade 5 teachers stated that the choice to assign collaborative learning activities is always pedagogically grounded and that the pupils are aware of the assessment criteria, which also includes expectations for group work. However, instead of explicitly teaching collaboration skills–such as negotiation strategies, roles or how to resolve conflicts (Nokes-Malach et al., 2012; Stahl et al., 2014)–grade 5 teachers mentioned specific learning activities with the aim of improving collaboration skills. These activities had been introduced during a separate social competence class and were not taught in the context of other curricular topics, nor did they feature digital technologies per se. The teachers described for example a problem-solving assignment that involved building with Legos and a brain-storming assignment regarding types of cars, which pupils worked on in small groups. Different approaches to these tasks were discussed after the performances, which can be a valuable source for learning when deliberated (Tammi and Rajala, 2018). However, while teachers talked about the aims and learning activities related to developing collaboration skills, they could not exemplify how pupils were guided in these tasks to improve their collaboration in general and CSCL in particular. The teachers assumed that by 5th grade, the pupils would already be familiar with the basic principles of collaboration and thus, implicit learning would be an appropriate approach. Therefore, they did not prioritize communication and collaboration skills during instruction time.

“Last year, in programming, when we began… we talked about why you work in pairs, they learned that. And they needed to know that only one of them should not have the iPad and do all the work.— So we talked about it, if they get it. I think that even though they did not explicitly discuss it [recently] they already know why they’re always in teams of two or three when they program.”

(Teacher M, grade 5, focus group interview)

One could perhaps compare communication and collaboration skills to learning how to read and write: the job is not done once the child decodes texts and puts letters together into words, and words together into sentences. The skills need to be refined, adapted, and developed further in a variety of contexts throughout the years to come. Learning how to improve and foster communication and collaboration skills requires lifelong training and development, particularly in a world where rapidly developing digital technologies continuously require adaptation (Ferrari, 2013). In CSCL, it is important to focus on the design and structure of the learning activities, to ensure that the pupils benefit from the chosen collective learning approach in terms of all learning goals (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995; Järvelä and Hadwin, 2013).

The two opposite models of teaching collaboration from the same school give us an interesting source of comparison between reactive and proactive strategies, or explicit and implicit learning approaches. One can consider to what extent the advantages of collective learning (Roediger and Karpicke, 2006; Kirschner et al., 2009; Rajaram and Pereira-Pasarin, 2010; Kuhn and Crowell, 2011; Nokes-Malach et al., 2012; Le et al., 2018) can be achieved when pupils are not explicitly guided in the process of communication and collaboration during their assignment. As found in many previous studies (e.g., Järvelä and Hadwin, 2013; Midtlund et al., 2021), also some of the teachers in this study had a tendency to just let collaboration happen, instead of guiding their pupils proactively in the process, which can be particularly tricky in technology-rich environments. It appeared that this common approach led to less constructive and versatile negotiations and increased conflicts and other issues within groups. Contrastingly, a proactive approach in grade 1 with an explicit focus on collaboration skills appeared to have many advantages: generally, the pupils contributed rather evenly, they listened to each other, negotiated solutions constructively, and had fewer conflicts than pupils in grade 5. In grade 5, pupils more frequently required a teacher to interfere to resolve a dispute, redirect the group, or prompt an individual to participate more actively. Some groups did not express a need for teacher assistance, but it did not necessarily mean that they could not have benefitted from it. This was evident for example in some of the rather pedestrian representations of knowledge in contexts that allowed a lot more innovative approach to the task. These results echo the findings of previous research from conventional and technology-rich classrooms (Järvelä and Hadwin, 2013; Stahl et al., 2014; Le et al., 2018; Midtlund et al., 2021; Nemiro, 2021). Naturally, the pupils’ age may be a contributing factor, as grade 1 pupils were still rather new to a school environment and had many basic skills yet to learn. Nevertheless, revisiting the main principles of collaboration frequently and ear-marking instruction time to learn about different aspects of collaboration and communication proactively in context with other curricular activities seemed to lead to smoother and more effective collaborative practices among pupils. This also allowed teachers to spend more time guiding all pupils in their assignments, rather than “putting out fires” in the more dysfunctional groups.

Concluding remarks

To sum up the findings, three aspects of this study could be highlighted. Firstly, teachers find that digitalization has increased collaboration in their classrooms and offer new avenues for communication that fall into the category of blended learning. While some of the use of digital technologies focused on employing digital technologies to improve communication (Roschelle, 2021; Yang et al., 2022)–for instance with multimodality and sharing opportunities–some of the contents were more directly focused on developing digital competencies or using digital technologies as a mediator, for instance, in robotics and programming (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995; Nemiro, 2021; Yang et al., 2022). Teachers used these opportunities frequently in their unit and lesson plans and encouraged collaboration among pupils. However, the results in this study indicate that as pupils become familiar with new digital collaboration opportunities, they should be actively and systematically guided in developing their competences using these new avenues. Expecting that pupils have the ability to transfer communication and collaboration strategies and skills to new digital platforms in a way that adds value to collective learning aspects may be too optimistic. For instance, while multimodality certainly offers exciting opportunities for pupil interaction, the presence of many somewhat monotonous demonstrations of collaboration using tools that allowed multimodality during the observation period implies that how to use these tools for the purpose of communication and collaboration should gain greater focus in classrooms.

Secondly, when using digital technologies for communication and collaboration, development and advantages of blended learning can also be found in smaller units, but more attention needs to be paid on cohesive assemblages in particular. Blended learning in technology-rich classrooms does not rule out face-to-face communication, use of pencil and paper, or other more conventional means of communicating. However, digital aspects in combination with the above-mentioned elements have potential in making communication more efficient and highlight new elements in the process of communication and collaboration (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995; Vaughan et al., 2013; Roschelle, 2021; Yang et al., 2022). At the same time, digital technologies can be used as collaboration mediators in learning activities (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995) or prompt pupil-led learning where pupils can demonstrate a variety of skills in collectively created digital products (Pulham and Graham, 2018; Yang et al., 2022). However, it seems that picking out one or two benchmarks from the list of characteristics that define blended learning and CSCL is not enough. When too much focus is laid on merely using ICT as a mediator or creating collective digital products, development of other aspects of CSCL and blended learning tends to remain vague. Learning activities and units should be designed as cohesive ensembles where many of the defining factors build on each other and eventually merge. This kind of a constructive process would demonstrate the true potential of CSCL and blended learning environments.

Thirdly, as in other collaborative practices, in collaboration with digital technologies collaboration itself should be an explicit learning goal and not just something (hopefully) happening on the side. Incorporating 21st century competences with digital dimensions in curriculums is known to be a difficult task (Voogt and Roblin, 2012; Krumsvik et al., 2016), and the variation among teachers and between grade levels in this study indicates that such challenges can exist also in classrooms led by digitally competent teachers. It is worth noting that the differences in pedagogical choices in first and fifth grade level approaches are not directly comparable, as grade 5 pupils already have many years of school behind them, while grade 1 pupils are only starting to learn the various competences required in school. Nevertheless, the results of this study, combined with findings from previous research, strongly indicate that in technology-rich classrooms, it is important to avoid relying solely on implicit learning when discussing 21st century competences, such as communication and collaboration. Instead, teachers should develop clear designs, goals, and criteria for them in lesson and unit plans in a way that accommodates also for more explicit instruction (Voogt and Roblin, 2012; van de Oudeweetering and Voogt, 2018). Grade 1 unit on programming, for instance, exemplifies a design of how such elements can be implemented in existing curricula. It is equally necessary to systematically develop and refine skills once learned in lower grades throughout different grade levels, to make sure that the pupils get frequent opportunities to expand and reconstruct their knowledge and skills in terms of 21st century competences. Doing this in context with other curricula could help pupils develop transferability of these competences in interdisciplinary environments.

Limitations and further research

As in all research, also this study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. The purposely selected and small sample, together with the qualitative nature of this case study, naturally sets limitations to the application and external validity of these findings. Acknowledging also the well-known challenges of case study approach, such as possible researcher bias and lack of systematized procedures, the aspects of rigor have been carefully considered and addressed with a comprehensive and flexible data collection process and using triangulation in analysis (Stake, 1995; Merriam and Tisdell, 2015; Bryman, 2016). Being an intrinsic case study, the aim was not to produce results for their generalizability but to learn from this specific case, and as such, the study fulfilled its purpose.

All in all, as operating in physical and digital learning environments parallel is becoming increasingly common, it is important to study, discuss, and innovate around communication and collaboration possibilities, challenges, and pitfalls, both in general and from a technology perspective in particular. The results presented in this paper contribute toward this discourse and invite further research–also from pupils’ perspective–about the influence of digital technologies on communication and collaboration practices in increasingly common blended learning contexts in all levels of education.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available in its original language upon request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Norwegian Centre for Research Data. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Stavanger.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.980445/full#supplementary-material

References

Bebell, D., and Kay, R. (2010). One to one computing: a summary of the quantitative results from the berkshire wireless learning initiative. J. Technol. Learn. Assess. 9:60.

Blau, I., Shamir-Inbal, T., and Hadad, S. (2020). Digital collaborative learning in elementary and middle schools as a function of individualistic and collectivistic culture: the role of ICT coordinators’ leadership experience, students’ collaboration skills, and sustainability. J. Comp. Assisted Learn. 36, 672–687. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12436

Blikstad-Balas, M., and Klette, K. (2020). Still a long way to go: narrow and transmissive use of technology in the classroom. Nordic J. Digital Literacy 15, 55–68. doi: 10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2020-01-05

Chen, B., Scardamalia, M., and Bereiter, C. (2015). Advancing knowledge-building discourse through judgments of promising ideas. Int. J. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learn. 10, 345–366. doi: 10.1007/s11412-015-9225-z

Craig, S. D., Chi, M. T. H., and VanLehn, K. (2009). Improving classroom learning by collaboratively observing human tutoring videos while problem solving. J. Educ. Psychol. 101:779. doi: 10.1037/a0016601

Creswell, J. W., and Guetterman, T. C. (2021). Educational Research. Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 6th Edn. Essex: Pearson.

Deiglmayr, A., and Spada, H. (2010). Developing adaptive collaboration support: the example of an effective training for collaborative inferences. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 22, 103–113. doi: 10.1007/s10648-010-9119-6

Del-Moral-Pérez, M. E., Villalustre-Martínez, L., Neira-Piñeiro, M., and del, R. (2019). Teachers’ perception about the contribution of collaborative creation of digital storytelling to the communicative and digital competence in primary education schoolchildren. Comp. Assisted Lang. Learn. 32, 342–365. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2018.1517094

Deschacht, N., and Goeman, K. (2015). The effect of blended learning on course persistence and performance of adult learners: a difference-in-differences analysis. Comp. Educ. 87, 83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.020

Diehl, M., and Stroebe, W. (1988). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: toward the solution of a riddle. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 53:497. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.497

Diziol, D., and Rummel, N. (2010). “How to design support for collaborative e-learning: a framework of relevant dimensions,” in E-collaborative Knowledge Construction, ed. B. Ertl (Pennsylvania, PA: IGI Global).

Farrell, T. S. C. (2009). Talking, Listening, and Teaching: A Guide to Classroom Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin press.

Ferrari, A. (2013). DIGCOMP: A Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe. Luxembourg: European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for Prospective Technological Studies.

Fjørtoft, S. O., Thun, S., and Buvik, M. P. (2019). Monitor 2019. En Deskriptiv Kartlegging av Digital Tilstand i Norske Skoler og Barnehager. Trondheim: SINTEF.

Gouseti, A., Abbott, D., Burden, K., and Jeffrey, S. (2020). Adopting the use of a legacy digital artefact in formal educational settings: opportunities and challenges. Technol. Pedagogy Educ. 29, 613–629. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2020.1822435

Graham, C. R., Borup, J., Pulham, E., and Larsen, R. (2019). K–12 blended teaching readiness: model and instrument development. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 51, 239–258. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2019.1586601

Harper, B., and Milman, N. B. (2016). One-to-One technology in K–12 classrooms: a review of the literature from 2004 through 2014. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 48, 129–142. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2016.1146564

Hesse-Biber, S., Rodriguez, D., and Frost, N. A. (2015). “A qualitatively driven approach to multimethod and mixed methods research,” in The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry, eds S. N. Hesse-Biber and R. B. Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.547773

Hur, J. W., and Oh, J. (2012). Learning, engagement, and technology: middle school students’ three-year experience in pervasive technology environments in South Korea. J. Educ. Comp. Res. 46, 295–312.

Järvelä, S., and Hadwin, A. F. (2013). New frontiers: regulating learning in CSCL. Educ. Psychol. 48, 25–39. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2012.748006

Johansson, N. O., Andersson, J., and Rönnberg, J. (2005). Compensating strategies in collaborative remembering in very old couples. Scand. J. Psychol. 46, 349–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2005.00465.x

Johler, M., Krumsvik, R. J., Bugge, H. E., and Helgevold, N. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of their role and classroom management practices in a technology rich primary school classroom. Front. Educ. 7:841385. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.841385

Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R. T. (1985). “The internal dynamics of cooperative learning groups,” in Learning to Cooperate, Cooperating to Learn, eds R. Slavin, S. Sharan, S. Kagan, R. Hertz-Lazarowitz, C. Webb, and R. Schmuck (Berlin: Springer), 103–124. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-3650-9_4

Karau, S. J., and Williams, K. D. (1994). Social loafing: a meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 65:681. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.681

Kelentrić, M., Helland, K., and Arstorp, A.-T. (2017). Professional Digital Competence Framework for Teachers. Norway: The Norwegian Centre for ICT in Education.

Kirschner, F., Paas, F., and Kirschner, P. A. (2009). A cognitive load approach to collaborative learning: united brains for complex tasks. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 21, 31–42. doi: 10.1007/s10648-008-9095-2

Koschmann, T. (2001). “Revisiting the paradigms of instructional technology. meeting at the crossroads,” in Proceedings of the 18th Annual Conference of the Australian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education, (Carbondale, IL).

Krumsvik, R. J., Jones, L. Ø, Øfstegaard, M., and Eikeland, O. J. (2016). Upper secondary school teachers’ digital competence: analysed by demographic, personal and professional characteristics. Nordic J. Digital Literacy 11, 143–164.

Kuhn, D., and Crowell, A. (2011). Dialogic argumentation as a vehicle for developing young adolescents’ thinking. Psychol. Sci. 22, 545–552. doi: 10.1177/0956797611402512

Le, H., Janssen, J., and Wubbels, T. (2018). Collaborative learning practices: teacher and student perceived obstacles to effective student collaboration. Cambridge J. Educ. 48, 103–122.

Meier, A., and Spada, H. (2008). “Promoting the drawing of inferences in collaboration: insights from two experimental studies,” in Proceedings of the 8th International Conference for the Learning Sciences – ICLS 2008, (Utrecht). doi: 10.11124/01938924-200907030-00001

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Midtlund, A., Instefjord, E. J., and Lazareva, A. (2021). Digital communication and collaboration in lower secondary school. Nordic J. Digital Literacy 16, 65–76.

Ministry of Education and Research (2019). Core Curriculum – Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education. New Delhi: Ministry of Education and Research.

Mishra, P., and Mehta, R. (2017). What we educators get wrong about 21st-century learning: results of a survey. J. Digital Learn. Teacher Educ. 33, 6–19. doi: 10.1080/21532974.2016.1242392

Moltudal, S., Krumsvik, R. J., Jones, Eikeland, O.-J., and Johnson, B. (2019). The relationship between teachers’ perceived classroom management abilities and their professional digital competence: experiences from upper secondary classrooms. a qualitative driven mixed method study. Designs Learn. 11, 80–98. doi: 10.16993/dfl.128

Mullen, B. (1987). “Self-Attention theory: the effects of group composition on the individual,” in Theories of Group Behavior, eds B. Mullen and G. R. Goethals (Berlin: Springer), 125–146. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4634-3_7

Nemiro, J. E. (2021). Building collaboration skills in 4th- to 6th-grade students through robotics. J. Res. Childhood Educ. 35, 351–372.

Nokes-Malach, T. J., Meade, M. L., and Morrow, D. G. (2012). The effect of expertise on collaborative problem solving. Think. Reason. 18, 32–58. doi: 10.1080/13546783.2011.642206

Nokes-Malach, T. J., Richey, J. E., and Gadgil, S. (2015). When is it better to learn together? insights from research on collaborative learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 27, 645–656. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9312-8

Norwegian National Directorate of Education and Training (2021). Norwegian National Curriculum: Rammeverk for Grunnleggende Ferdigheter. Oslo: Norwegian National Directorate of Education and Training.

Pulham, E., and Graham, C. R. (2018). Comparing K-12 online and blended teaching competencies: a literature review. Distance Educ. 39, 411–432. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2018.1476840

Rajaram, S., and Pereira-Pasarin, L. P. (2010). Collaborative memory: cognitive research and theory. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 649–663. doi: 10.1177/1745691610388763

Redecker, C. (2017). European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators. Luxembourg: European Commission.

Roediger, H. L., and Karpicke, J. D. (2006). The power of testing memory: basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 181–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x

Rogers, E. M. (1995). “Diffusion of innovations,” in An integrated approach to communication theory and research, 4th Edn. ed. E. M. Rogers (New York, NY: Free Press), 432–448. doi: 10.4324/9780203887011-36

Roschelle, J., and Teasley, S. D. (1995). “The construction of shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving,” in Computer Supported Collaborative Learning, ed. C. O’Malley (Berlin: Springer), 69–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85098-1_5

Roschelle, J. (2021). “Intelligence augmentation for collaborative learning,” in Adaptive instructional systems. Design and evaluation, eds R. A. Sottilare and J. Schwarz (Berlin: Springer Nature), 254–264.

Saldaña, J. (2021). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage Publications.

Schofield, J. W. (1995). Computers and Classroom Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511571268

Sjølie, E., Strømme, A., and Boks-Vlemmix, J. (2021). Team-skills training and real-time facilitation as a means for developing student teachers’ learning of collaboration. Teach. Teacher Educ. 107:103477. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103477

Stahl, G. (2015). A decade of CSCL. Int. J. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learn. 10, 337–344. doi: 10.1007/s11412-015-9222-2

Stahl, G., Ludvigsen, S., Law, N., and Cress, U. (2014). CSCL artifacts. Int. J. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learn. 9, 237–245. doi: 10.1007/s11412-014-9200-0

Sung, Y.-T., Chang, K.-E., and Liu, T.-C. (2016). The effects of integrating mobile devices with teaching and learning on students’ learning performance: a meta-analysis and research synthesis. Comp. Educ. 94, 252–275. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.008

Sung, W., Ahn, J., and Black, J. B. (2022). Elementary students’ performance and perceptions of robot coding and debugging: Embodied approach in practice. J. Res. Childhood Educ. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2022.2045399

Tammi, T., and Rajala, A. (2018). Deliberative communication in elementary classroom meetings: ground rules, pupils’ concerns, and democratic participation. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 62, 617–630. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2016.1261042

van de Oudeweetering, K., and Voogt, J. (2018). Teachers’ conceptualization and enactment of twenty-first century competences: exploring dimensions for new curricula. Curriculum J. 29, 116–133.

van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van Dijk, J. A. G. M., and de Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: a systematic literature review. Comp. Hum. Behav. 72, 577–588. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.010

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., and Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry. Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press.

Voogt, J., and Roblin, N. P. (2012). A comparative analysis of international frameworks for 21 st century competences: implications for national curriculum policies. J. Curriculum Stud. 44, 299–321. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2012.668938

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Keywords: communication, collaboration, blended learning, digital technologies, CSCL, education

Citation: Johler M (2022) Collaboration and communication in blended learning environments. Front. Educ. 7:980445. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.980445

Received: 28 June 2022; Accepted: 24 August 2022;

Published: 06 October 2022.

Edited by:

Mohammed A. Al-Sharafi, University of Technology Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Zaleha Abdullah, University of Technology Malaysia, MalaysiaDorian Gorgan, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Copyright © 2022 Johler. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Minttu Johler, bWludHR1LmpvaGxlckBpbm4ubm8=

Minttu Johler

Minttu Johler