- Department of Special Education, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

Introduction: Children and adolescents with intellectual disability (ID) and high levels of autistic traits often attend special needs classrooms where they spend a lot of time with other students who demonstrate diverse impairments and competencies. Research in typical development shows that classmates and the classroom composition in terms of specific classmate competencies can have a strong impact on individual social development. In this context, classmates’ social skills are of particular interest, as they are associated with successful social interaction and the ability to establish and maintain social relationships. Based on these associations, the present study investigated whether the levels of autistic traits and social skills in children and adolescents with ID and high levels of autistic traits are influenced by their classmates’ levels of social skills.

Methods: A longitudinal design was used, with the first measurement point at the beginning of the school year and the second at the end of the school year. School staff members provided information on 330 students with ID and high levels of autistic traits (20.6% girls; mean age 10.17 years, SD = 3.74) who were schooled in 142 classrooms across 16 Swiss special needs schools.

Results: Results showed that students’ individual levels of autistic traits and social skills at T2 were not predicted by the classroom level of social skills at T1 when controlling for individual levels of autistic traits, individual levels of social skills, gender, age, and general levels of functioning at T1.

Discussion: Considering the present findings, perspectives for further research and support of children and adolescents with ID and high levels of autistic traits within the classroom context are discussed.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by difficulties in social communication and social interaction and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which are associated with impairments in multiple domains of social development. ASD is a persistent condition that generally lasts throughout a person’s life. However, the quantitative and qualitative manifestation of autistic traits can change over time, which in some cases may result in individuals no longer fulfilling the diagnostic criteria as they grow older (Seltzer et al., 2004; Woodman et al., 2015). This developmental change in individual autistic traits can be predicted by individual characteristics, such as verbal and cognitive abilities (Seltzer et al., 2004; McGovern and Sigman, 2005; Shattuck et al., 2007), and environmental factors, such as family characteristics (Greenberg et al., 2006; Shattuck et al., 2007; Woodman et al., 2015).

In terms of social communication and social interaction, individuals with ASD show difficulties with a broad range of social skills (Matson and Wilkins, 2007). These difficulties may noticeably emerge when individuals with ASD go to school, where they need social skills to adequately interact with their peers. However, the social skill development of individuals with ASD can improve over time, for example, through peer-based interventions (DiSalvo and Oswald, 2002; Williams White et al., 2007).

A contextual factor in the development of autistic traits and social skills that has received less attention is the naturalistic influence of peers. In typical development, there is ample evidence that peers impact students’ behavioral development (Brown et al., 2008; Müller and Zurbriggen, 2016) through mechanisms such as imitation, social reinforcement, and adaptation to peer norms (Bandura and Walters, 1963; Brown et al., 2008; Akers, 2009). In the school context, peers include the students’ classmates (Müller and Zurbriggen, 2016). Thus, school is an important environment for children and adolescents to meet peers, build social relationships, and facilitate social learning. In Switzerland, where this study was conducted, many students with ASD attend special needs schools for students with intellectual disability (ID) where they are grouped into classes with peers who have different types of disabilities and competencies (Eckert, 2015).

Students with ID and high levels of autistic traits, who are often schooled in special needs classrooms, tend to be at risk for less advantageous outcomes (see, e.g., Matson and Shoemaker, 2009). Thus, it is important to study how children and adolescents with ID and high levels of autistic traits may benefit from their classmates’ skills. In this regard, the social skills of classmates could be particularly important, as they are associated with successful social interaction and the ability to establish and maintain social relationships (Nangle et al., 2020). There are numerous definitions of social skills in the existing literature. In this study, social skills are defined as the skills needed to behave competently in a specific social situation (Harrison and Oakland, 2015; Grover et al., 2020). Knowing more about the influence of classmates’ social skills on individual autistic traits and social skills can promote a better understanding of the development of students with high levels of autistic traits and illuminate new avenues for classroom interventions to support them.

Autistic traits and ID

Autistic traits are assumed to be continuously distributed in the general population, from individuals with almost no autistic traits to individuals with very high levels of autistic traits, which lead to an ASD diagnosis (de Groot and de van Strien, 2017). Prevalence rates of ASD have increased in recent years. At the same time, there is relatively high variability in prevalence estimates across the world (Chiarotti and Venerosi, 2020). Recent research suggests that in the general population, approximately 1 in 44 children are diagnosed with ASD (Maenner et al., 2021). About 33 to 70% of individuals with ASD also have an intellectual disability (Ritvo et al., 1989; Fombonne, 2005; Charman et al., 2011; Knopf, 2020), which is defined by intellectual and adaptive functioning that is about two standard deviations below the general population (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Prevalence studies have shown widely varying results for ASD incidence in persons with ID, ranging from about 8% to 40%, depending on diagnostic criteria, sampling procedures, and measurement instruments used (see, e.g., La Malfa et al., 2004; de Bildt et al., 2005; Tonnsen et al., 2016). At the same time, some individuals with ID exhibit autistic-like behavior without having an ASD diagnosis. For example, many individuals with ID show repetitive behavior (Kästel et al., 2021) or difficulties with social interactions and social skills (Leffert and Siperstein, 2002; Guralnick, 2006; Sukhodolsky and Butter, 2007). However, there is consensus that individuals with ID have an increased likelihood of also receiving an ASD diagnosis (see, e.g., Tonnsen et al., 2016). Additionally, more severe forms of ID seem to be associated with a greater likelihood of being diagnosed with ASD (Vig and Jedrysek, 1999).

Despite the overlap between the two conditions, a review by Matson and Shoemaker (2009) showed that individuals with both ASD and ID differ behaviorally from individuals with ID or ASD alone. For example, their adaptive behavior may differ. Thus, the authors concluded that these groups have different needs. Regarding social skills, a study by Syriopoulou-Delli et al. (2016) suggested that children with ASD and ID have lower social skill levels compared to children with only ASD. These findings may also be relevant to consider in terms of social interaction and peer influence processes. For example, children and adolescents with ID and ASD may need specific support in their school environments to benefit from their peers.

Internationally, many children and adolescents with ID are still schooled outside regular schools (e.g., special needs schools; Norwich, 2008; Bundesamt für Statistik, 2019). Also, children and adolescents with ASD are still largely educated in special needs settings, especially when their ASD is associated with an ID (Harris and Handleman, 2000; Dolev et al., 2014). In Switzerland, about 25% of all kindergarten students with an ASD diagnosis attend special needs schools. These rates increase to about 57% for primary school students with ASD and approximately 73% among upper secondary school students with ASD (Eckert, 2015). Since children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits experience limited social relationships in their spare time (Shattuck et al., 2011; Ratcliff et al., 2018), their classmates may be especially important to their socialization.

General susceptibility to social and peer influence in individuals with high levels of autistic traits

While peer influence in typically developing children and adolescents is well investigated, very little is known about peer influence in individuals with high levels of autistic traits. Some of the characteristics associated with ASD may suggest that individuals with high levels of autistic traits are less susceptible to social and peer influence. Generally, students with ASD experience difficulties in their peer relationships (Cresswell et al., 2019) that can lead to individuals with ASD having fewer peer interactions than typically developing individuals (Petry, 2018). Hence, children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits may experience fewer situations in which peer influence occurs. In addition, within social interactions, children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits may be less influenced by their peers. The tendency for individuals with ASD to experience problems with recognizing emotions and the intentions of others (Nuske et al., 2013) may result in difficulties with (correctly) recognizing and categorizing peers’ behavior, which is essential to peer influence, according to Bandura’s social learning theory (Bandura, 2007). In addition, people with ASD often show a natural preference for details, which in some cases may result in a greater focus on the details of an environment rather than on the global picture (Happé and Frith, 2006). In social situations, this tendency could lead children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits to focus on the actions of a specific peer, for example, without considering the presence and reactions of other peers. Hence, some peer influence mechanisms, such as social reinforcement in groups, may not occur in the same way as in typical development.

These assumptions are partly supported by studies investigating social influence in individuals with ASD. For example, children with ASD were found to conform less to the opinion of others compared to typically developing children (Yafai et al., 2014). In addition, Izuma et al. (2011) found that adults with ASD did not change their donation behavior in the presence of an observer in a game-like experiment that involved donating money, in contrast to non-autistic participants.

In an experimental study, van Hoorn et al. (2017) investigated the influence of peer feedback on prosocial behavior. Under different conditions, 144 male adolescents with and without ASD played a computer-based common public goods game in which they had to decide whether to keep tokens for themselves (selfish behavior) or donate them to their group (prosocial behavior). In one condition, peers commented on these decisions by rating them with likes. Results showed that within the total sample, higher levels of autistic traits and higher intelligence were associated with less sensitivity to antisocial peer feedback (i.e., peers praised selfish behavior, but not prosocial behavior). In line with these findings, Verrier et al. (2020) investigated the conformity of adolescents with and without ASD in peer pressure situations using a vignette approach. They found that higher levels of autistic traits were associated with less peer conformity (Verrier et al., 2020).

However, several studies have contradicted the above findings, instead indicating that individuals with ASD are susceptible to social and peer influence. Using Asch’s line judgment task (Asch, 1956), Bowler and Worley (1994) investigated social conformity in eight adults with ASD. Results showed no overall differences in conformity between the ASD group and non-autistic comparison groups. Lazzaro et al. (2019) confirmed these results. In a verbal memory task, they did not find differences in conformity between young adults with ASD and those without. Further, in their experiment, van Hoorn et al. (2017) found that male adolescents with and without ASD were sensitive to peer feedback on their own prosocial behavior (i.e., prosocial donation of tokens).

Only two studies were found that examined peer influence on autistic traits. A study by Nenniger and Müller (2020) investigated teacher-perceived peer influence among students with ASD in a special needs school attended only by students with ASD and low adaptive functioning. Teacher reports on 23 students with ASD showed that autistic behavior was influenced by peers, although not very often and with varying degrees of influence across subtypes of autistic behavior. Furthermore, in a longitudinal study using the same data set as the present study, Nenniger et al. (2021) examined whether the development of autistic traits in students with ID and high levels of such characteristics is influenced by the level of autistic traits among their preferred peers at school. Results showed that girls were susceptible to peer influence on autistic traits but boys were not (Nenniger et al., 2021).

To my knowledge, the influence of peers on social skills has only been addressed in peer-based intervention studies. DiSalvo and Oswald (2002) reviewed research on peer-mediated interventions designed to promote social skills in children with ASD. While the reviewed intervention studies offer important evidence about how peers can effectively promote social skills through peer-mediated interventions, they do not provide information about naturally occurring socialization processes in classrooms.

In summary, study results on peer influence susceptibility in individuals with ASD are limited and sometimes contradictory. Only two studies were found that investigated peer influence on autistic traits in a naturalistic school context. Neither of these studies explicitly examined the influence of classmates. In addition, to my knowledge, no study has yet examined naturally occurring influence of classmates on social skills in children and adolescents with high autistic traits and ID.

The influence of classmates’ social skills

Peer influence occurs within different relation types (Juvonen and Galván, 2008; Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011). According to Kindermann (2016), one type of peer groups consists of all members of the classroom, who can be considered as important developmental agents. Although there is a lack of research regarding classmates’ influence on autistic traits and social skills among students in special needs classrooms, there are both theoretical and empirical sets of knowledge that serve as a basis for further assumptions. For example, Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) ecological system theory identified the classroom context, which includes the classmates, as an important factor influencing the development of an individual. Also, Bandura and Walters (1963) emphasized the power of peers in the social learning theory. According to this theory, children and adolescents learn new behavior through the observation and imitation of (peer) models or adapt already learned behavior due to responses from their environment (e.g., reward or punishment; Bandura, 2007). In this context, social norms also play an important role regarding peer influence. Descriptive norms (i.e., what most others do; e.g., the average behavioral level in a group) can impact individual behavior (Cialdini et al., 1991). For example, an individual may adapt their own behavior to the behavioral level of a group to fit in (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004).

In typical development, there is ample evidence that those within involuntary peer groups (e.g., classmates) influence each other and become more similar over time (socialization; Juvonen and Galván, 2008). For example, studies have shown that more prosocial behavior among classmates is associated with less individual antisocial behavior over time (Henry and Chan, 2010; Hofmann and Müller, 2018). This example shows that desirable behavioral norms among classmates can reduce challenging individual behavior. In addition, individuals may also profit from their classmates’ skills in terms of desirable behavioral outcomes. A study by Finch et al. (2019) showed, for example, that higher average levels of classmates’ executive functions were linked to increased growth of students’ individual executive functions, at least when considering reaction times for executive function tasks.

Based on these findings, it is assumed that individual levels of autistic traits and social skills may be influenced by classmates’ average level of social skills. This study defines social skills as those needed to behave competently in a specific social situation (Harrison and Oakland, 2015; Grover et al., 2020). Accordingly, the term encompasses a wide range of skills, including, for example, prosocial skills like helping or praising others and skills such as saying thank you or expressing emotions (Harrison and Oakland, 2015). Since social skills are related to positive peer interactions and the ability to build and maintain social relationships (Nangle et al., 2020), students with ID and high levels of autistic traits may benefit in two ways from high social skill levels among their classmates. First, they may have better and more numerous social interactions and develop more relationships with highly socially skilled classmates, which may generally increase opportunities for peer influence. Second, in classrooms with high levels of social skills, they have more opportunities to observe peer models showing such skills and possibly adjust their own behavior accordingly. Such observation and adjustment may go along with positive developmental outcomes and contribute to a change in autistic trait and social skill exhibition in students with ID and high levels of autistic traits. However, these assumptions have yet to be investigated.

The current study

This study aims to investigate the influence of classmates’ social skills on autistic trait and social skill development in students with high levels of autistic traits and ID in special needs classrooms using a longitudinal research design with two measurement points (T1: August–October 2018, T2: April–June 2019) to examine two research questions. These research questions extend from earlier findings by Nenniger et al. (2021) that focused on the influence of preferred peers at school on autistic traits.

First, it was investigated whether the levels of autistic traits of students with ID and high levels of autistic traits—hereafter referred to as target students—are influenced by their classmates’ social skill levels. It was expected that higher classroom levels of social skills at T1 would predict lower individual levels of autistic traits among target students at T2 (Hypothesis 1). To test this hypothesis, a classic peer influence research procedure was used by predicting individual levels of autistic traits at T2 based on the classroom level of social skills at T1, controlling for individual levels of autistic traits at T1 (Kindermann and Gest, 2009). In addition, I controlled for gender and age, as these two variables are known to impact individual peer influence susceptibility for some behavior types in typical development (see, e.g., Erickson et al., 2000; Steinberg and Monahan, 2007; Conway et al., 2011). In addition, to generalize the findings on peer influence independently of students’ general functioning, I also controlled for levels of general functioning.

Second, it was examined whether the classroom level of social skills at T1 would predict target students’ individual social skills levels at T2. Based on the theoretical and empirical considerations described above, it was expected that higher classroom levels of social skills at T1 would predict higher individual levels of social skills among target students at T2 when controlling for target students’ individual levels of social skills at T1 (Hypothesis 2). To test this second hypothesis, the same procedure as described above was applied.

Materials and methods

Participants

I used data from a longitudinal research project (KomPeers) in the German-speaking part of Switzerland with measurements at the beginning and end of the school year (T1: August–October 2018, T2: April–June 2019). Data were collected from 179 classrooms across 16 special needs schools for students with ID (Müller et al., 2020). In Switzerland, these schools can only be attended by students with a clinical diagnosis of ID, which is usually based on ICD-10 criteria including an IQ < 70 and a clinical rating of adaptive behavior (World Health Organization, 2019). Hence, all participants had intellectual functioning within the range of an ID. On average, special needs schools had 80.05 students per school (SD = 23.64, range = 28–121) and 6.64 students per classroom (SD = 1.72, range = 4–15).

For the present research questions, data from a subsample of 330 target students with ID and high levels of autistic traits (above the autism cut-off score of the instrument used; see below) were analyzed. 203 school staff members provided information on these 330 target students. At T1, 83% of the staff members were female participants and the mean age was 45.52 (SD = 11.32). In terms of training levels, 45.4% were special needs teachers; others had other teacher training or were therapists, social workers, pedagogical staff, or long-term trainees. At the beginning of the study, these members reported knowing the target students for an average of 12.57 months (SD = 13.28). Each staff member reported on M = 1.60 target students (SD = 0.97, range 1–6). In 79.4% of the cases, the reports for the same student were filled out by the same staff member at T1 and T2.

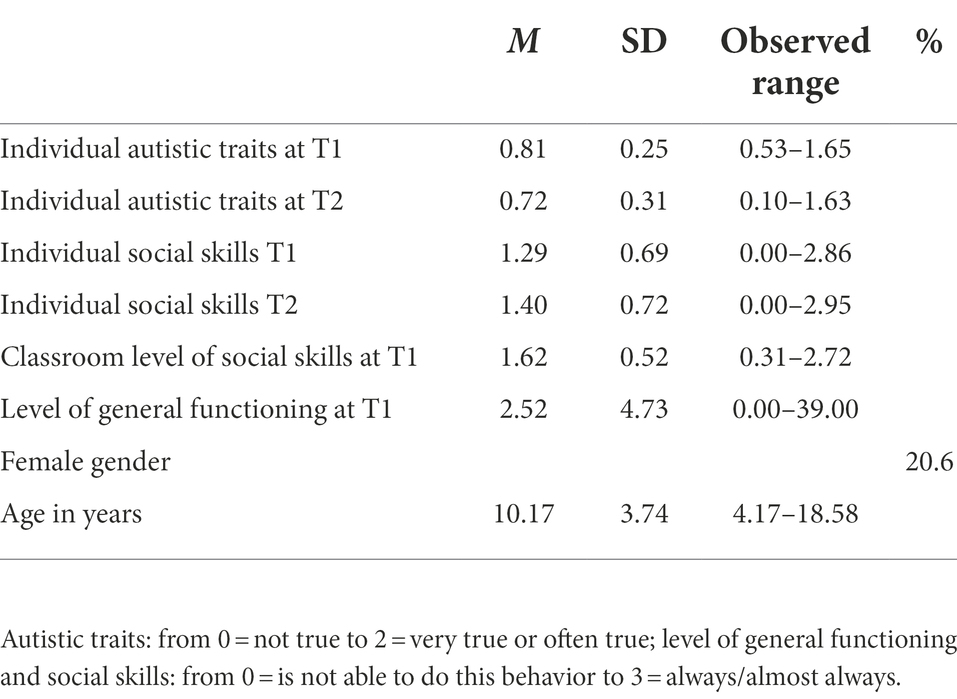

Target students were schooled in 144 classrooms across 16 special needs schools. They were on average 10.71 years old (SD = 3.74, range = 4.17–18.58), and 20.6% were female. Descriptive information on the demographics, individual levels of autistic traits, and levels of general functioning among target students is displayed in Table 1 (see also Nenniger et al., 2021).

Measures

Individual autistic traits

To assess students’ autistic trait levels at T1 and T2, the German version of the Developmental Behavior Checklist Teacher Form (DBC-T) was used (Brereton et al., 2002; Einfeld and Tonge, 2002; Einfeld et al., 2007). The DBC-T is a 94-item checklist to assess a broad spectrum of behaviors in children and adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). The instrument provides a score for six subscales (disruptive behavior, self-absorbed behaviors, communication disturbance, anxiety, social relating, and a category with a set of remaining items termed “others”), as well as a score for total problem behavior. The instrument’s norms are based on an Australian sample of 640 children and adolescents aged 4 to 18 years old who have an ID (IQ < 50).

Part of the DBC can be used as a screening instrument for ASD. The Autism Screening Algorithm (DBC-ASA) includes 29 items and was evaluated in a sample of 180 autistic and non-autistic or typically developing children and adolescents matched for gender, age, and IQ level (Brereton et al., 2002). Evaluations of the DBC-ASA showed differentiation between those with and without ASD. The revised Autism Screening Algorithm (DBC-ASAR1) by Steinhausen and Winkler Metzke (2004) resulted from an evaluation of the DBC-ASA in a German-speaking sample of 84 individuals with ASD and 84 participants with ID matched by gender, age, and disability level (assessed with a four-item disability rating). The DBC-ASAR1 consists of 40 items (e.g., avoids eye contact, aloof, in his/her own world, does not respond to others’ feelings, upset over changes in routine/environment, repeats same word/phrase), shows a very good internal consistency (α = 0.93, α = 0.81 in the present data set), and obtained the best cut-off score at 21, resulting in a sensitivity of 0.85 and a specificity of 0.61. This cut-off score was used to identify the 330 target students with high levels of autistic traits. For statistical analyses, the mean of all DBC-ASAR1 item scores was used to determine the individual level of autistic traits of each target student, with higher values indicating higher levels of autistic traits.

Individual level of social skills

Social skills were measured at T1 and T2 using the “social” subscale of the German version of the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-3 (ABAS-3; Harrison and Oakland, 2015; Bienstein et al., 2018). This instrument is based on the original U.S. version (Harrison and Oakland, 2015) and consists of 174 items rated on a scale from 0 = is not able to 3 = always/almost always. The items are distributed across nine subscales, which are calculated in various combinations to form a conceptual score (Communication, Functional Academics, Self-Direction), a social score (Leisure, Social), and a practical score (Self-Care, School Living, Community Use, Health and Safety), as well as an overall General Adaptive Composite. The ABAS-3 norms are based on a sample of 1,896 persons from the general U.S. population. The instrument has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability (Harrison and Oakland, 2015).

The “social” ABAS-3 subscale includes 22 items and assesses skills needed for interacting socially and getting along with others, such as seeking friendships with peers, offering help to classmates or teachers, and showing compassion (Harrison and Oakland, 2015). The internal consistency in the current study was α = 0.95. For statistical analyses, the mean of all item scores for the “social” subscale was used to determine the individual level of social skills of each target student, with higher values indicating higher levels of social skills.

Classroom level of social skills

Following a procedure often used for investigating classroom contextual effects on future individual outcomes (Marsh et al., 2012), the classroom level of social skills in this study was obtained by calculating the mean of all students’ social skill mean scores within a class at T1. Hence, each student in the same class had the same context score for social skills. Higher values indicated more social skills.

Demographics

A staff member reported on students’ gender (male or female) and age in months.

Level of general functioning

In this study, the adaptive behavior scores of students were compared to the ABAS-3 reference norm from the general U.S. population (Harrison and Oakland, 2015) to estimate students’ individual levels of general functioning. The adaptive behavior was assessed with the German version of the ABAS-3 for teachers (Bienstein et al., 2018). For the analyses at hand, the percentile rank of the overall score of adaptive functioning was used (in the present data α = 0.99) to indicate the level of functioning relative to age. Higher values mean less impairment.

Procedure

The Institutional Research Commission of the Department of Special Education of the University of Fribourg reviewed and accepted the KomPeers research project in terms of the scientific and ethical procedures. School headmasters were informed about the study through written correspondence and personal meetings. Also, parents received a letter written using plain language principles and translated into the nine most frequently used languages in Switzerland with information about the study and a guarantee of anonymity. The letter underscored that no medical diagnoses would be assessed, participation was voluntary, and parents could decline their child’s participation. School staff were also informed about the study and could refuse to participate. To ensure complete anonymity, a coding system was used for data collection and analysis. Hence, the researcher never had access to names of staff members, students, or parents.

Statistical analyses

In the preliminary analyses, I first provided information about descriptive statistics for the main variables. I then looked at the correlations of these variables to examine the strength of their relationships (Table 2).

For the main analyses and to test the hypotheses, a nested data structure was considered (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). School personnel served as raters, and in some cases, more than one staff member per classroom gave information about students’ competencies. Hence, data on individual students are nested within raters (M = 1.60 students per rater, range = 1–6). Sometimes, there was more than one rater in a classroom. Hence, raters were nested within classrooms (M = 1.41 raters per classroom, range = 1–4). Due to raters’ specific answer patterns, scores reported by the same raters are likely more similar to one another than to scores reported by different raters. Relative to raters from other classrooms, raters within the same classroom are likely more similar, as raters in the same classroom have the same classroom context. Consequently, I estimated multilevel models with three levels (Level 1: students; Level 2: raters; Level 3: classrooms) to avoid biased results. The software Mplus 8.4, which accounts for unbalanced data due to missing values by applying full information maximum likelihood estimation, was used (Muthén and Muthén, 2017).

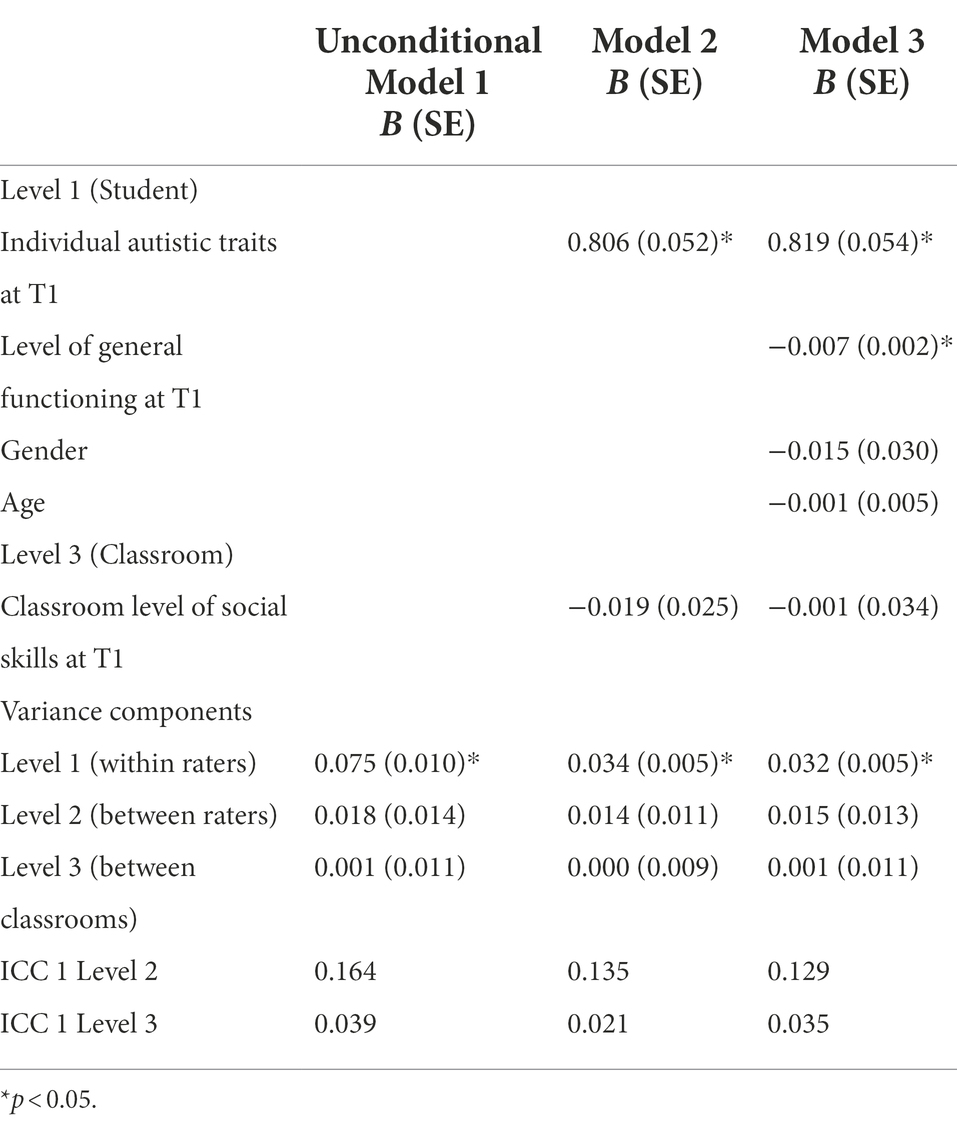

To test the effect of the classroom levels of social skills on target students’ individual levels of autistic traits, variables were added stepwise into the model. To determine variances and intraclass correlations, I first estimated an unconditional model (Table 3: Model 1). Second, I predicted the individual autistic trait levels of target students at T2 using the classroom level of social skills at T1, controlling for individual levels of autistic traits at T1 (Table 3: Model 2). To test Hypothesis 1, I again predicted the individual levels of autistic traits of target students at T2 by the classroom level of social skills, this time controlling for target students’ average individual level of autistic traits, level of general functioning, gender, and age (Table 3: Model 3).

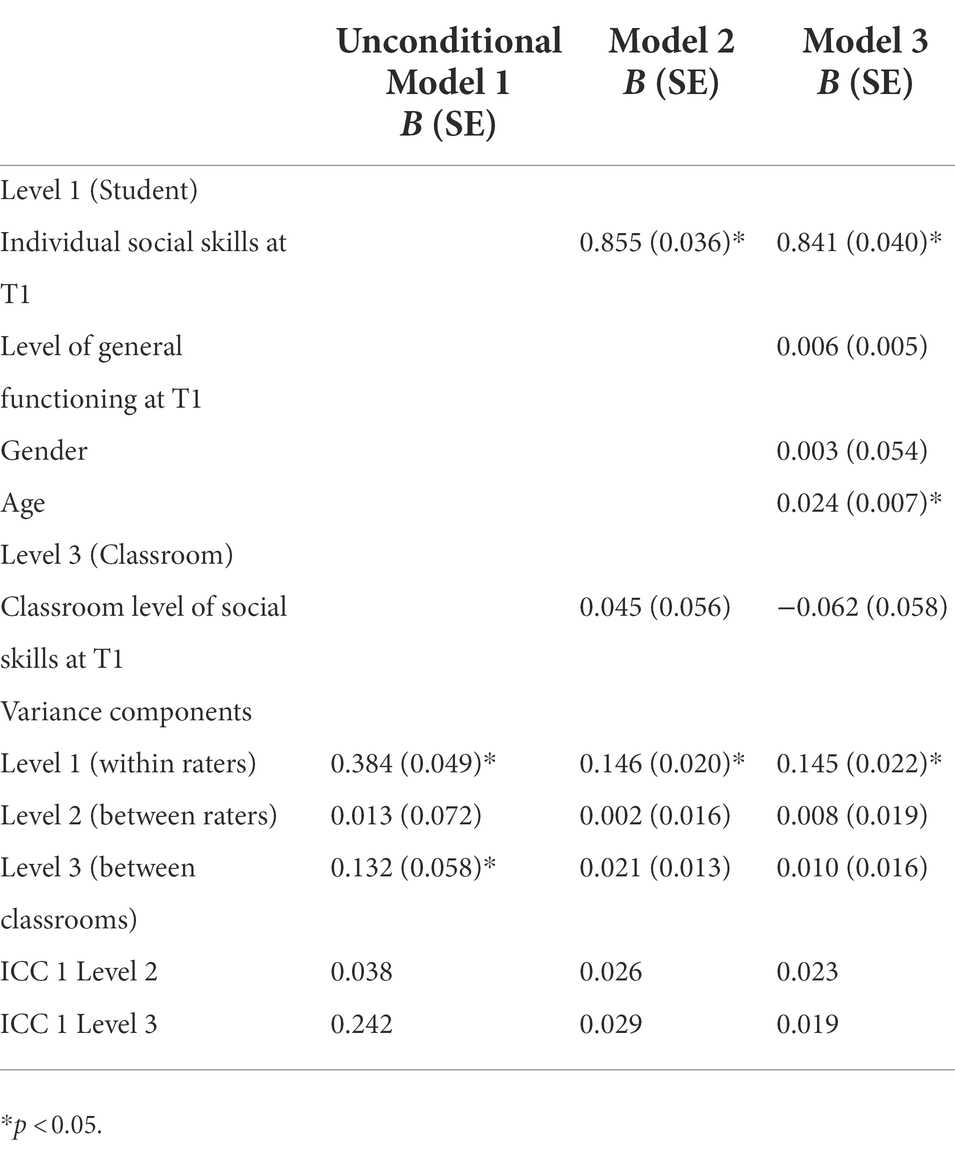

To calculate the classroom effect of social skills on target students’ individual social skill levels, the same stepwise procedure was followed (Table 4: Models 1 and 2). To test Hypothesis 2, I predicted target students’ individual levels of social skills at T2 by the classroom level of social skills at T1, controlling for individual levels of social skills at T1, levels of general functioning, gender, and age (Table 4: Model 3).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the main study variables. At T1, the average individual level of autistic traits among the target students was 0.81 (SD = 0.25, range = 0.53–1.65), and at T2 it was 0.72 (SD = 0.31, range = 0.10–1.63). A dependent sample t-test showed that this decrease in autistic traits was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The average individual level of social skills increased from 1.29 (SD = 0.69, range = 0.00–2.86) at T1 to 1.40 (SD = 0.72, range = 0.00–2.95) at T2. This increase was statistically significant (p < 0.001), as determined through a dependent sample t-test. In addition, target students showed very low levels of general functioning, with an average percentile rank of 2.52 (SD = 4.73, range = 0.00–39.00). The average classroom level of socials skills among target students at T1 was 1.62 (SD = 0.52, range = 0.31–2.72).

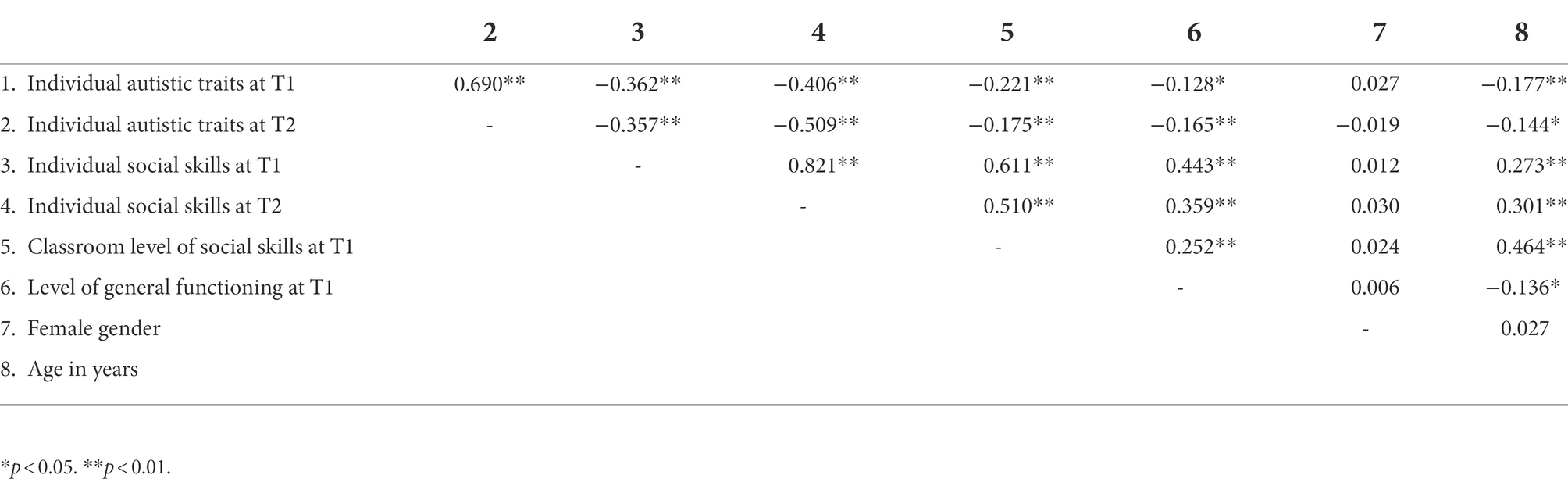

The correlations between the study variables used in the main analyses are displayed in Table 2. More individual autistic traits at T1 were strongly correlated with more individual autistic traits at T2 [r (312) = 0.690, p < 0.001], and more individual social skills at T1 were strongly correlated with more social skills at T2 [r (312) = 0.821, p < 0.001]. Negative correlations were found between individual autistic traits at T1 and individual social skills at both timepoints [T1: r (326) = −0.362, p < 0.001; T2: r (314) = −0.406, p < 0.001], indicating that more individual autistic traits at T1 were associated with fewer social skills at T1 and T2. Also, more individual autistic traits at T2 were correlated with fewer social skills at T1 [r (310) = −0.357, p < 0.001] and T2 [r (309) = −0.509, p < 0.001]. While negative correlations were found between the classroom level of social skills at T1 and individual autistic traits at T1 and T2, strong positive associations were found between the classroom level of social skills at T1 and individual social skill levels at T1 and T2. These findings indicate that when more social skills were exhibited in a classroom at T1, fewer individual autistic traits at T1 [r (328) = −0.221, p < 0.001] and T2 [r (312) = −0.175, p = 0.002] and more individual social skills at T1 [r (326) = 0.611, p < 0.001] and T2 [r (314) = 0.510, p < 0.001] were shown. Furthermore, small negative correlations between the individual level of general functioning and the individual measures of autistic traits [T1: r (291) = −0.128, p = 0.029; T2: r (278) = −0.165, p = 0.006] and moderate positive correlations between the individual level of general functioning and the individual measures of social skills [T1: r (291) = 0.443, p < 0.001; T2: r (280) = 0.359, p < 0.001] were found. These findings mean that the higher students’ average general functioning level was, the lower the average level of individual autistic traits but the higher the average level of individual social skills. A higher level of individual general functioning was also associated with a higher classroom level of social skills [r (291) = 0.252, p < 0.001]. Gender was not correlated with any other variable. Older students were reported to show fewer autistic traits at T1 [r (319) = −0.177, p = 0.001] and T2 [r (305) = −0.144, p = 0.011] and more individual social skills at T1 [r (317) = 0.273, p < 0.001] and T2 [r (307) = 0.301, p < 0.001]. Also, a positive correlation between age and the classroom level of social skills at T1 was found, indicating that the older students were, the higher the social skill level in their classroom [r (319) = 0.464, p < 0.001]. In contrast, the older the students were, the lower the reported level of general functioning relative to age [r (291) = −0.136, p = 0.020].

Main analyses

Table 3 displays the results of the main analyses for the classroom effect of social skills on individual levels of autistic traits. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in the unconditional model was 0.164 for Level 2 and 0.039 for Level 3, indicating that 16.4% of the variance in individual autistic traits was due to differences between the raters and 3.9% was due to differences between the classrooms.

The first hypothesis stated that more social skills in a classroom at T1 would predict fewer individual autistic traits among target students at T2. Model 2, shown in Table 3, indicated that the classroom level of social skills at T1 had no significant effect on future individual autistic traits at T2 (p = 0.445) when controlling for individual autistic traits at T1. This result indicates that individual autistic traits levels at T2 were not predicted by classroom levels of social skills at T1. When students’ levels of general functioning, gender, and age were added as controls to the model (Model 3), this effect remained non-significant (p = 0.968). Hence, the first hypothesis was rejected.

In terms of control variables, I found that individual autistic traits at T1 had a significant effect on individual autistic traits at T2 (B = 0.819, SE = 0.054, p < 0.001), indicating that more autistic traits at the beginning of the school year predicted more autistic traits at the end of the school year. In addition, a greater level of general functioning at T1 predicted a lower level of individual autistic traits at T2 (B = −0.007, SE = 0.002, p = 0.001). No significant effects of the other control variables (gender and age) were found.

Table 4 shows the results of the main analyses for the classroom effect of social skills on individual levels of social skills. The ICC in the unconditional model was 0.038 for Level 2 and 0.242 for Level 3, indicating that 3.8% of the variance in individual social skills was due to differences between the raters and 24.2% was due to differences between the classrooms.

In Hypothesis 2, it was expected that a higher classroom level of social skills at T1 would predict higher individual levels of social skills among target students at T2. The results, presented in Table 4, showed no effect of the classroom level of social skills at T1 on individual social skills at T2 when controlling for individual social skills at T1 (p = 0.421). This finding suggests that individual social skills levels at T2 were not predicted by the classroom levels of social skills at T1. This result remained non-significant when the control variables were added in Model 3 (p = 0.289). Hence, the second hypothesis was rejected.

Regarding the control variables, individual social skills at T1 were found to affect individual social skills at T2 (B = 0.841, SE = 0.040 p < 0.001). This finding indicates that more social skills at the beginning of the school year predicted more social skills at the end of the school year. Furthermore, a higher age at T1 predicted more social skills at T2 (B = 0.024, SE = 0.007, p = 0.001). No significant effects of the other control variables (gender and level of general functioning) were found.

Discussion

This study aimed to extend the knowledge regarding peer influence on autistic traits and social skills in children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits and ID. Therefore, the influences of all classmates’ levels of social skills (i.e., classroom context) on the development of individual autistic traits and social skills were investigated. The results revealed no evidence that children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits and ID are influenced by the average level of social skills in special needs classrooms.

To better understand these main results, the findings from the preliminary analyses should be considered first. These results showed that individual autistic traits of children and adolescents decreased over time. This finding is in line with studies showing that the levels of autistic traits in individuals with ASD can change over time (Seltzer et al., 2004; Woodman et al., 2015), with many individuals who have ASD showing fewer autistic traits as they grow older (McGovern and Sigman, 2005; Shattuck et al., 2007). Yet, autistic traits decreased less in individuals with lower general functioning levels, which aligns with other studies showing that individuals in this group have less advantageous outcomes (Seltzer et al., 2004; Shattuck et al., 2007). Furthermore, individuals in classrooms with norms tied to higher social skills exhibited fewer autistic traits. At the same time, students’ individual social skills increased over the school year. This result is consistent with the assumption that students’ social skills improve with age and that the social skills of students with ASD can be increased (DiSalvo and Oswald, 2002; Williams White et al., 2007; Nangle et al., 2020). In addition, students showed more social skills in classrooms with higher social skill levels. Both sets of findings suggest that the level of social skills in an environment may be related to individual autistic traits and social skills (without taking into account the multilevel structure).

The first hypothesis, which postulated that the classroom level of social skills influences the development of individual autistic traits, was not confirmed. This reduced susceptibility to peer influence in individuals with high levels autistic traits and ID is not consistent with findings from typical development showing that positive classroom norms influence individual behavior development (Henry and Chan, 2010; Hofmann and Müller, 2018). Furthermore, this finding partly contradicts the results from Nenniger et al. (2021), who found that girls’ autistic traits are influenced by their peers. On the other hand, this finding corresponds with many studies showing that individuals with high levels of autistic traits are less sensitive to social or peer influence (Izuma et al., 2011; Yafai et al., 2014; van Hoorn et al., 2017; Verrier et al., 2020).

Second, I hypothesized that higher classroom levels of social skills at the beginning of the school year would be related to an increase in individual social skills at the end of the school year. This assumption was not confirmed by the present data. This finding is at odds with studies on typical development, which show that for many behavioral domains, future individual behavior can be predicted by earlier mean classroom behavior when controlling for earlier individual behavior in regular classrooms (e.g., Müller and Zurbriggen, 2016). However, this result is again in line with studies showing that individuals with high levels of autistic traits are less influenced by others (Izuma et al., 2011; Yafai et al., 2014; van Hoorn et al., 2017; Verrier et al., 2020).

One explanation for these results may relate to the characteristics of students with high levels of autistic traits and ID. For example, difficulties in social interaction and communication and low levels of general functioning may impede important mechanisms that underlie peer influence, such as observational learning and social reinforcement. Another explanation may pertain to the general stability of the average levels of autistic traits and social skills. The results showed strong associations between the levels of autistic traits at the beginning and the end of the school year and between the levels of social skills at these two timepoints. Although it is known that the exhibition of autistic traits and social skills can change over time (DiSalvo and Oswald, 2002; Seltzer et al., 2004; Williams White et al., 2007; Woodman et al., 2015), changes in these characteristics due to peer behavior may not become apparent within a short period of time.

Implications

Although no peer effects could be identified in this study, the results provide important indications for theoretical and practical implications. Generally, individual factors, such as past autistic trait levels, social skill levels, and the level of general functioning, may play a more important role in the development of autistic traits and social skills than do contextual factors like the behavior of classmates. Even though the findings of the investigated sample contrast with the knowledge regarding typical development, in which the peer context is a strong predictor of individual behavior (see, e.g., Brown et al., 2008; Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011), they are probably not entirely surprising, since there is evidence that ASD depends on genetics and other pre-, peri-and neonatal biological factors (see, e.g., Ratajczak, 2011) that appear to strongly influence individual autistic trait and social skill exhibition and development. In addition, an ASD diagnosis usually persists throughout a person’s life, although the expression of autistic traits may change over time (Seltzer et al., 2004). However, earlier studies have shown that for girls, autistic traits do not necessarily remain unaffected by preferred peers (Nenniger et al., 2021). The composition of the peer group may be of importance regarding peer influence for individuals with high levels of autistic traits. For example, it could be that children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits are not influenced by the peers who surround them most of the time, like their classmates, but are affected by those who are particularly salient for them, such as friends or preferred peers. Furthermore, it is possible that other individuals, such as teachers, have a stronger influence on autistic traits and social skills than do peers. These assumptions could not be tested in this study and should be investigated in future research.

Although no classroom effect on individual autistic traits and social skills in children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits and ID was found in this study, this result does not necessarily mean that this group is completely unaffected by their classmates. Indeed, it may be that other behaviors, such as deviant behavior or academic achievement, are influenced by classmates. Furthermore, the investigated group may need specific support in the natural classroom context to benefit from their classmates’ competencies. Hence, it remains an open question whether the autistic traits and social skills of children and adolescents are influenced when support is provided in the classroom. Professionals, including teachers, may play an important role in this process by helping to create structured social contexts (see, e.g., Farmer et al., 2018). Furthermore, they may help recognize and interpret social cues or positive social behaviors of peers by providing verbal prompts or translating social situations (see, e.g., Camargo et al., 2014).

Overall, more research is needed to better understand the development of autistic traits and social skills in children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits and ID regarding the peer context and to develop new perspectives on support and intervention for these individuals.

Limitations and future research directions

This study provided new insights into peer influence on autistic traits and social skills, focusing on classroom effects in special needs schools. Strengths of this longitudinal study were the relatively large sample size of children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits and ID and the high participation rates. These factors allowed the researcher to gather reliable information on a group of individuals who is often underrepresented in research and has a heightened risk for negative outcomes (see, e.g., Matson and Shoemaker, 2009).

However, the present study also had some limitations. First, I investigated a specific group of children and adolescents attending special needs schools. Although I controlled for individual autistic traits and general functioning levels, the results cannot be generalized to children and adolescents with high levels of autistic traits who are within the normal range of general functioning, as these students may have developed strategies to cope with social difficulties (see, e.g., Mandy, 2019). In addition, the results are relevant for children and adolescents attending special needs classrooms but not for those attending other types of classrooms (e.g., inclusive classrooms), where, for example, the competencies of classmates and the class sizes are not comparable to special needs settings. Second, to obtain a large sample size and high participations rates, I relied on school staff reports. Although staff reports are considered reliable and valid for assessing a wide range of behaviors (see, e.g., Einfeld and Tonge, 1995; Constantino and Gruber, 2005; Goodman, 2005), further research should attempt to include self-reports also. Third, due to the use of anonymous data, I had no information on students’ clinical diagnoses of ASD, and I therefore had to rely on an autism screening algorithm. Future studies would benefit from gathering more information about students’ reliable clinical diagnoses. Fourth, this study investigated classmates’ influence on two behavioral domains: the overall levels of autistic traits and social skills. To draw more precise conclusions, it would be interesting to see whether only particular aspects of autistic traits, such as repetitive behavior or communicative features, are influenced by peers.

In conclusion, this study aimed to increase the understanding of individual and contextual factors that influence the development of autistic traits and social skills in children and adolescents with ID and high levels of autistic traits. As peer influence research regarding individuals with high levels of autistic traits is just beginning, the findings should serve as a starting point and stimulate further research on the socialization of this population to help provide appropriate support in the peer context.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Research Commission of the Department of Special Education of the University of Fribourg. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

GN collected part of the data used, conducted all analyses, and wrote this paper.

Funding

This research was supported by grant SNF-172773 from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akers, R. L. (2009). Social Learning and Social Structure: A General Theory of Crime and Deviance (2nd.). Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Edn.). Philadelphia, PA: American Psychiatric Association.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. a minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 70, 1–70. doi: 10.1037/h0093718

Bandura, A. (ed.). (2007). Psychological Modeling: Conflicting Theories. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Bandura, A., and Walters, R. H. (1963). Social Learning and Personality Development. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Bienstein, P., Döpfner, M., and Sinzig, J. (2018). “Fragebogen zu den Alltagskompetenzen: ABAS-3,” in Deutsche Evaluationsfassung [Adaptive Behavior Assessment System: ABAS-3. German Evaluation Version] (Dortmund, Germany: Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, Technical University Dortmund).

Bowler, D. M., and Worley, K. (1994). Susceptibility to social influence in adults with Asperger's syndrome: a research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 35, 689–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01214.x

Brechwald, W. A., and Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: a decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J. Res. Adolesc. 21, 166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x

Brereton, A. V., Tonge, B. J., Mackinnon, A. J., and Einfeld, S. L. (2002). Screening young people for autism with the developmental behavior checklist. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 41, 1369–1375. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00019

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). “Ecological models of human development,” in International Encyclopedia of Education. eds. T. Husten and T. N. Postlethwaite. 3rd Edn. (Oxford: Elsevier), 1643–1647.

Brown, B. B., Bakken, J. P., Ameringer, S. W., and Mahon, S. D. (2008). “A comprehensive conceptualization of the peer influence process in adolescence,” in Understanding Peer Influence in Children and Adolescents. eds. M. J. Prinstein and K. A. Dodge (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 17–44.

Bundesamt für Statistik. (2019). Satistik der Sonderpädagogik [special education statistics]. Neuenburg: Bundesamt für Statistik.

Camargo, S. P. H., Rispoli, M., Ganz, J., Hong, E. R., Davis, H., and Mason, R. (2014). A review of the quality of behaviorally-based intervention research to improve social interaction skills of children with ASD in inclusive settings. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 2096–2116. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2060-7

Charman, T., Pickles, A., Simonoff, E., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., and Baird, G. (2011). Iq in children with autism spectrum disorders: data from the special needs and autism project (SNAP). Psychol. Med. 41, 619–627. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000991

Chiarotti, F., and Venerosi, A. (2020). Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders: a review of worldwide prevalence estimates since 2014. Brain Sci. 10:274. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10050274

Cialdini, R. B., and Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 591–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., and Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: a theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 24, 201–234. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5

Constantino, J. N., and Gruber, C. P. (2005). Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Conway, C. C., Rancourt, D., Adelman, C. B., Burk, W. J., and Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Depression socialization within friendship groups at the transition to adolescence: the roles of gender and group centrality as moderators of peer influence. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 120, 857–867. doi: 10.1037/a0024779

Cresswell, L., Hinch, R., and Cage, E. (2019). The experiences of peer relationships amongst autistic adolescents: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 61, 45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.01.003

de Bildt, A., Sytema, S., Kraijer, D., and Minderaa, R. (2005). Prevalence of pervasive developmental disorders in children and adolescents with mental retardation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46, 275–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00346.x

de Groot, K., and de van Strien, J. W. (2017). Evidence for a broad autism phenotype. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 1, 129–140. doi: 10.1007/s41252-017-0021-9

DiSalvo, C. A., and Oswald, D. P. (2002). Peer-mediated interventions to increase the social interaction of children with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 17, 198–207. doi: 10.1177/10883576020170040201

Dolev, S., Oppenheim, D., Koren-Karie, N., and Yirmiya, N. (2014). Early attachment and maternal insightfulness predict educational placement of children with autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 8, 958–967. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.04.012

Eckert, A. (2015). Autismus-Spektrum-Störungen in der Schweiz: Lebenssituation und fachliche Begleitung [Autism spectrum disorder in Switzerland: Life situation and professional support]. Bern, Switzerland: SZH/CSPS.

Einfeld, S. L., and Tonge, B. J. (1995). The developmental behavior checklist: the development and validation of an instrument to assess behavioral and emotional disturbance in children and adolescents with mental retardation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 25, 81–104. doi: 10.1007/BF02178498

Einfeld, S. L., and Tonge, B. J. (2002). Manual for the Developmental Behaviour Checklist (DBC) (2nd). Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales and Monash University.

Einfeld, S. L., Tonge, B. J., and Steinhausen, H.-C. (2007). VFE: Verhaltensfragebogen bei Entwicklungsstörungen [DBC: Developmental Behavior Checklist]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Erickson, K. G., Crosnoe, R., and Dornbusch, S. M. (2000). A social process model of adolescent deviance: combining social control and differential association perspectives. J. Youth Adolesc. 29, 395–425. doi: 10.1023/A:1005163724952

Farmer, T. W., Dawes, M., Hamm, J. V., Lee, D., Mehtaji, M., Hoffman, A. S., et al. (2018). Classroom social dynamics management: why the invisible hand of the teacher matters for special education. Remedial Spec. Educ. 39, 177–192. doi: 10.1177/0741932517718359

Finch, J. E., Garcia, E. B., Sulik, M. J., and Obradović, J. (2019). Peers matter: links between classmates’ and individual students’ executive functions in elementary school. AERA Open 5:233285841982943. doi: 10.1177/2332858419829438

Fombonne, E. (2005). Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66, 3–8.

Goodman, R. (2005). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire: T4-17. Available at: https://www.sdqinfo.org/py/sdqinfo/b3.py?language=Englishqz.

Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., Hong, J., and Orsmond, G. I. (2006). Bidirectional effects of expressed emotion and behavior problems and symptoms in adolescents and adults with autism. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 111, 229–249. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[229:BEOEEA]2.0.CO;2

Grover, R. L., Nangle, D. W., Buffie, M., and Andrews, L. A. (2020). “Defining social skills,” in Social Skills Across the Life Span: Theory, Assessment, and Intervention. eds. D. Nangle, C. Erdley, and R. Schwartz-Mette (London: Elsevier Academic Press), 3–24.

Guralnick, M. J. (2006). Peer relationships and the mental health of young children with intellectual delays. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 3, 49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00052.x

Happé, F., and Frith, U. (2006). The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 36, 5–25. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0

Harris, S. L., and Handleman, J. S. (2000). Age and IQ at intake as predictors of placement for young children with autism: a four-to six-year follow-up. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 30, 137–142. doi: 10.1023/a:1005459606120

Harrison, P. L., and Oakland, T. (2015). ABAS-3: Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (3rd Edn.). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Henry, D., and Chan, W. Y. (2010). Cross-sectional and longitudinal effects of sixth-grade setting-level norms for nonviolent problem solving on aggression and associated attitudes. J. Community Psychol. 38, 1007–1022. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20411

Hofmann, V., and Müller, C. M. (2018). Avoiding antisocial behavior among adolescents: the positive influence of classmates' prosocial behavior. J. Adolesc. 68, 136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.07.013

Izuma, K., Matsumoto, K., Camerer, C. F., and Adolphs, R. (2011). Insensitivity to social reputation in autism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 17302–17307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107038108

Juvonen, J., and Galván, A. (2008). “Peer influence in involuntary social groups: lessons from research on bullying,” in Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. eds. M. J. Prinstein and K. A. Dodge (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 225–244.

Kästel, I. S., Vllasaliu, L., Wellnitz, S., Cholemkery, H., Freitag, C. M., and Bast, N. (2021). Repetitive behavior in children and adolescents: psychometric properties of the German version of the repetitive behavior scale-revised. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 1224–1237. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04588-z

Kindermann, T. A. (2016). “Peer group influences on students' academic motivation” in Handbook of Social Influences in School Contexts: Social-Emotional, Motivation, and Cognitive Outcomes. eds. K. R. Wentzel and G. B. Ramani (London, United Kingdom: Routledge), 31–47.

Kindermann, T. A., and Gest, S. D. (2009). “Assessment of the peer group: identifying naturally occuring social networks and capturing their effects,” in Social, Emotional, and Personality Development in Context. Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. eds. K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, and B. Laursen (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 100–117.

Knopf, A. (2020). Autism prevalence increases from 1 in 60 to 1 in 54: CDC. Brown Univ. Child Adolesc. Behav. Lett. 36:4. doi: 10.1002/cbl.30470

La Malfa, G., Lassi, S., Bertelli, M., Salvini, R., and Placidi, G. F. (2004). Autism and intellectual disability: a study of prevalence on a sample of the Italian population. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 48, 262–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00567.x

Lazzaro, S. C., Weidinger, L., Cooper, R. A., Baron-Cohen, S., Moutsiana, C., and Sharot, T. (2019). Social conformity in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 1304–1315. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3809-1

Leffert, J. S., and Siperstein, G. N. (2002). Social cognition: a key to understanding adaptive behavior in individuals with mild mental retardation. Int. Rev. Res. Mental Retard. 25, 135–181. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7750(02)80008-8

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., et al. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism Spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 70, 1–16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1

Mandy, W. (2019). Social camouflaging in autism: is it time to lose the mask? Autism 23, 1879–1881. doi: 10.1177/1362361319878559

Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Nagengast, B., Trautwein, U., Morin, A. J. S., Abduljabbar, A. S., et al. (2012). Classroom climate and contextual effects: conceptual and methodological issues in the evaluation of group-level effects. Educ. Psychol. 47, 106–124. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2012.670488

Matson, J. L., and Shoemaker, M. (2009). Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 30, 1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.06.003

Matson, J. L., and Wilkins, J. (2007). A critical review of assessment targets and methods for social skills excesses and deficits for children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 1, 28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2006.07.003

McGovern, C. W., and Sigman, M. (2005). Continuity and change from early childhood to adolescence in autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46, 401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00361.x

Müller, C. M., Amstad, M., Begert, T., Egger, S., Nenniger, G., Schoop-Kasteler, N., et al. (2020). Die Schülerschaft an Schulen für Kinder und Jugendliche mit einer geistigen Behinderung-Hintergrundmerkmale, Alltagskompetenzen und Verhaltensprobleme [Student characteristics in special needs schools for children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities – Demographics, adaptive and problem behaviors]. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 4, 347–368. doi: 10.25656/01:21615

Müller, C. M., and Zurbriggen, C. (2016). An overview of classroom composition research on social-emotional outcomes: introduction to the special issue. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. 15, 163–184. doi: 10.1891/1945-8959.15.2.163

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus User's Guide (8th Edn.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nangle, D., Erdley, C., and Schwartz-Mette, R. (Eds.) (2020). Social Skills Across the Life Span: Theory, Assessment, and Intervention, London: Elsevier Academic Press.

Nenniger, G., Hofmann, V., and Müller, C. M. (2021). Gender differences in peer influence on autistic traits in special needs schools - evidence from staff reports. Front. Psychol. 12:718726. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.718726

Nenniger, G., and Müller, C. M. (2020). Do peers influence autistic behaviours? First insights from observations made by teachers. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 657–670. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1783799

Norwich, B. (2008). Dilemmas of difference, inclusion and disability: international perspectives on placement. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 23, 287–304. doi: 10.1080/08856250802387166

Nuske, H. J., Vivanti, G., and Dissanayake, C. (2013). Are emotion impairments unique to, universal, or specific in autism spectrum disorder? A comprehensive review. Cogn. Emot. 27, 1042–1061. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.762900

Petry, K. (2018). The relationship between class attitudes towards peers with a disability and peer acceptance, friendships and peer interactions of students with a disability in regular secondary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 254–268. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1424782

Ratajczak, H. V. (2011). Theoretical aspects of autism: causes - a review. J. Immunotoxicol. 8, 68–79. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2010.545086

Ratcliff, K., Hong, I., and Hilton, C. (2018). Leisure participation patterns for school age youth with autism spectrum disorders: findings from the 2016 National Survey of Children's health. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 3783–3793. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3643-5

Raudenbush, S. W., and Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ritvo, E. R., Freeman, B. J., Pingree, C., Mason-Brothers, A., Jorde, L., Jenson, W. R., et al. (1989). The UCLA-University of Utah epidemiologic survey of autism: prevalence. Am. J. Psychiatry 146, 194–199. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.2.194

Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Abbeduto, L., and Greenberg, J. S. (2004). Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 10, 234–247. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20038

Shattuck, P. T., Orsmond, G. I., Wagner, M., and Cooper, B. P. (2011). Participation in social activities among adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One 6:e27176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027176

Shattuck, P. T., Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., Orsmond, G. I., Bolt, D., Kring, S., et al. (2007). Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescents and adults with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 1735–1747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0307-7

Steinberg, L., and Monahan, K. C. (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Dev. Psychol. 43, 1531–1543. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531

Steinhausen, H.-C., and Winkler Metzke, C. (2004). Differentiating the behavioural profile in autism and mental retardation and testing of a screener. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 13, 214–220. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-0400-4

Sukhodolsky, D. G., and Butter, E. M. (2007). “Social skills training for children with intellectual disabilities,” in Issues on Clinical Child Psychology. Handbook of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. eds. J. W. Jacobson, J. A. Mulick, and J. Rojahn (Boston, MA: Springer), 601–618.

Syriopoulou-Delli, C. K., Agaliotis, I., and Papaefstathiou, E. (2016). Social skills characteristics of students with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 64, 35–44. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2016.1219101

Tonnsen, B. L., Boan, A. D., Bradley, C. C., Charles, J., Cohen, A., and Carpenter, L. A. (2016). Prevalence of autism apectrum disorders among children with intellectual disability. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 121, 487–500. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-121.6.487

van Hoorn, J., van Dijk, E., Crone, E. A., Stockmann, L., and Rieffe, C. (2017). Peers influence prosocial behavior in adolescent males with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 2225–2237. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3143-z

Verrier, D., Halton, S., and Robinson, M. (2020). Autistic traits, adolescence, and anti-social peer pressure. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 8, 131–138. doi: 10.5114/cipp.2020.94317

Vig, S., and Jedrysek, E. (1999). Autistic features in young children with significant cognitive impairment: autism or mental retardation? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 235–248. doi: 10.1023/A:1023084106559

Williams White, S., Keonig, K., and Scahill, L. (2007). Social skills development in children with autism spectrum disorders: a review of the intervention research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 1858–1868. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0320-x

Woodman, A. C., Smith, L. E., Greenberg, J. S., and Mailick, M. R. (2015). Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescence and adulthood: the role of positive family processes. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 111–126. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2199-2

World Health Organization. (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Keywords: autistic traits, intellectual disability, peer influence, classroom context, special education, social skills

Citation: Nenniger G (2022) Classroom influence—Do students with high autistic traits benefit from their classmates’ social skills? Front. Educ. 7:971775. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.971775

Edited by:

Gregor Ross Maxwell, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, NorwayReviewed by:

Stian Orm, Innlandet Hospital Trust, NorwayAnders Dechsling, Østfold University College, Norway

Copyright © 2022 Nenniger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gina Nenniger, Z2luYS5uZW5uaWdlckB1bmlmci5jaA==

†ORCID: Gina Nenniger, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4044-8902

Gina Nenniger

Gina Nenniger