- 1Department of Basic Psychological Processes and Their Development, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain

- 2Department of Didactics and School Organization, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain

Some families identified as being at risk, including families of immigrant origin, demonstrate a lower degree of participation in school communities. This constitutes a major challenge for educational institutions. In this research, a case study including three public schools affected by school segregation was carried out. The aim was to analyze and disseminate teachers’ experiences and contributions around the question of family-school relationships, particularly measures they take to promote the participation of families in the daily life of schools. This included a particular focus on schools characterized by high degree of segregation and pupils with higher levels of social vulnerability. The study was carried out as a multi-local ethnographic project in three schools in the Basque Country, Spain, through participant observation, interviews, and focus groups with teachers, pupils, school leadership teams and psycho-pedagogical teams. The results obtained show that schools condition the participation of families, especially those most at risk, and that this has an impact on the socio-emotional development of children. They also highlight the importance of building communication and relationship channels between families and schools. In the current age of globalization, the need to create a network of collaborative and trusting relationships between families and teachers is more evident than ever. Only by these means can children be properly supported to achieve their maximum potential.

Introduction

The family and the school are the two principal spaces for socialization in contemporary education. In our society, the family is the basic unit of social organization and, therefore, a foundational socializing agent. As the root source of socialization, families are responsible for fostering coexistence and promoting healthy relationships based on communication and respect. This, in turn, protects the fundamental rights of the most vulnerable family members: children (Altarejos et al., 2005; López, 2008a). The establishment of secure and stable affective bonds and the satisfaction of children’s basic emotional needs in the family is fundamental to ensuring their well-being and promoting their healthy development (López, 2008b). The above directly influences the development of other personal characteristics including the social skills, attitudes and behaviors that shape their relationships with peers, teachers and the school (Moreno et al., 2009). Therefore, the family acts as a mediator in the relationships that children have with other institutions, their peers and society in general.

In order to satisfy their children’s fundamental needs and to protect them from real or imagined dangers, families rely on other social institutions. Through schools, the arena of socialization is expanded and the education and lessons received in the family are complemented. Relationships and learning, initially contained largely within the private sphere of the nucleus of primary coexistence, that is, the family, expand through school participation (Rebolledo and Elosu, 2009; Cambil and Romero, 2018). In this way, it is hoped that families overcome, as far as possible, the communication and relational difficulties of the people who compose them and establish relationships involving two-way interchange with their schools and neighborhoods (SiiS Fundación Eguía-Careaga Fundazioa, 2017).

Research over a period of decades has identified the participation of families in schools as essential for better educational practice and a contributing factor in students’ teaching-learning process (Rasbash et al., 2010; Epstein, 2011; Vigo and Soriano, 2015). Bolívar (2006), Escribano and Martínez (2016) and Simón and Barrios (2019) have argued that families should participate in school communities for a number of reasons. Their own knowledge of their children complements that of teachers; they are very invested in their children’s learning; they are involved in their children’s education throughout their schooling; they can positively influence the quality of educational support offered; and they can and should participate in decisions made by educational teams about their children. For all these reasons, families can contribute enormously in the design of school practices.

However, the role families play is conditioned by the sensitivity of schools to the diversity of the wider school community, including families’ needs, opinions and motivations, among other issues (Bryan and Henry, 2012; Valdés and Sánchez, 2016). Depending on the level of involvement required by a school, families can occupy a role ranging from the passive reception of information through to leadership in both the teaching-learning process and the organization and management (Ceballos and Saiz, 2021).

Thus, the practices of a school can facilitate family-school relationships, or promote the opposite. Some practices can inhibit relationships or be exclusionary in the way they generate and manage the relationship with certain families, particularly those belonging to disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, ethnic groups or other groups at risk of exclusion (Dovemark and Beach, 2014; Vigo et al., 2016; Vigo-Arrazola and Dieste-Gracia, 2020). Literature from diverse contexts (Lareau and Horvat, 1999; Horvat et al., 2003; McNamara et al., 2003; Arnaiz and Parrilla, 2019; Vigo-Arrazola and Dieste-Gracia, 2019) argues that families with more social and cultural capital tend to be more involved in school, while the participation of immigrant families tends to be lower than that of native families. This constitutes a significant challenge. Language difficulties, lack of time, a low educational level and cultural differences between the country of origin and the host country are often cited as causes of this low participation (Moreno, 2017). Ceballos and Saiz (2021) categorize different forms of family participation, which mainly depend on school policy. These are fictitious participation, in which the role of families is limited to receiving information from schools; symbolic participation, where families are informed and consulted, but they have little influence on school decision-making; partial participation, when a coalition is established between schools and families but participation is guided by the school and, finally, full participation, when schools and families are fully co-responsible, collaborating equally.

In the context of this complex reality, education professionals also share the perspective that families have a significant influence on scholastic performance and the probability that children will progress in their academic trajectories (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010). This impact is expressed in terms of primary effects, that is school results and the effect of social class on academic performance, and secondary effects, that is, the effect of social class on decision making processes which determine educational trajectories through the transmission of values and expectations about education that children internalize (Bernardi and Cebolla, 2014, p.4; Nusche, 2009). A number of international studies have observed that an economically unstable family environment influences both the level of academic expectations and the degree of initial educational inequality due to social origin (Laureau and Cox, 2011; Weininger et al., 2015; Cebolla-Boado et al., 2016). Along these lines, different authors engage with the question of cultural reproduction (Bourdieu and Passeron, 2021). For Cambil and Romero (2018), for example, psychological construction and individual identity are formed and different social roles that enable cultural reproduction are adopted from early childhood. Lahire (2008) notes that several indicators reoccur in research analyzing the reproduction of social class structures in school. These indicators include repetition rates, definitive exit from the school system, school failure, grades achieved and teachers’ evaluations, among others. School failure, among other consequences, can put the self-esteem of a student at risk and generate conflict with classmates, and can initiate a string of family and school conflicts, school absenteeism, etc. (Ararteko, 2011; Laureau and Cox, 2011; Texeira, 2016; Smith, 2019).

This article focuses on school segregation and participation in educational contexts and, more specifically, on family participation in three centers located in the Basque Country, Spain. In this study, the term school segregation refers to the unequal composition of schools and the environment in which they are located. This entails an unequal distribution of students in schools based on their personal or social characteristics (Bonal, 2018; Martínez and Ferrer, 2018; Murillo and Martínez-Garrido, 2018). This research is centered on the views of teachers who participated in this research. We present a detailed analysis of three public schools in which the student body includes a high proportion of immigrants (Rapley, 2014; Bisquerra, 2016). As well as being immigrants, the families participating in these schools have a high incidence of unemployment, and many receive financial support to cover school expenses including the purchase of teaching materials and the monthly school canteen fee.

Regarding the Gorard index, which is used to quantify school segregation in Spain, and taking into consideration only first-generation immigrant pupils, the Basque Country overall, together with Extremadura, is hypersegregated (more than 0.5 on the Gorard index; Murillo et al., 2017). Almost all other regions in Spain have a lower index and thus, while not limited to the Basque Country, school segregation is of particular concern here. It should also be noted that school segregation by socio-economic level in the Basque Country is also fairly unique. As highlighted by Murillo and Martínez-Garrido (2019), school segregation is very high for pupils from low socio-economic families, but only moderate for high socio-economic families. Alkorta and Shershneva (2021) have identified two factors as among the main causes of school segregation in the region. The first is the large proportion of students enrolled in private schools. The second is the separation of education into two linguistic streams, either Basque or Spanish. These streams are delivered in separate classes or separate institutions, creating a physical separation between students enrolled in each model. The overall outcome is that pupils of foreign origin and reduced economic status tend to be concentrated in specific public schools.

Consequently, it is of vital importance to build an education network based on collaboration and trusting relationships between all participating actors, in which families and teachers interact, with special attention focused on spaces that are stigmatized or subject to disadvantage (Ararteko, 2011; Santizo, 2011; Etxebarria and Sagastume, 2013; Carneros and Murillo, 2017; Vigo and Dieste, 2017).

School practices that contribute to recognizing family identity could help include disadvantaged groups and those at risk of marginalization (Vigo-Arrazola and Dieste-Gracia, 2019). However, at least as far as we are aware, there is little existing research on family participation in Spain and very little that goes into detail as to how this participation is managed (Vigo and Dieste, 2017). Therefore, in order to fill this gap in the literature, the aim of this paper is to analyze and disseminate how family-school relationships are seen from the perspective of teachers who promote the participation of families in the daily life of schools, placing an emphasis on schools characterized by a high degree of segregation and the overrepresentation of students characterized by higher levels of social vulnerability.

Materials and methods

In this qualitative research we used multi-local school ethnography (Marcus, 2001; Maturana and Garzón, 2015) in which three public schools affected by school segregation participated (Flick, 2018).

The particularity of educational ethnography is that it investigates the meanings present in social reality that emerge in schools through interpersonal relations (Cotán, 2020). Seen from this point of view, ethnography is an opportunity for teachers to reflect on their practices, their involvement and their situated and connected knowledge, thus facilitating their professional evolution. Questioning the beliefs implicit in their educational practice and becoming aware of their repercussions on student’s teaching-learning process contributes to their professional development (Vigo et al., 2016).

This study describes social phenomena related to the inclusion and exclusion of 150 children due to the social segregation experienced by their families. In addition, the different initiatives carried out in favor of inclusivity by the schools in collaboration with families were also assessed.

Context and participants

This paper focuses on teachers in three public schools in the Basque Country (Spain), including their practices and discourses in relation to the issues of segregation. The Basque Country is a Spanish autonomous community located in the north of Spain, bordering France. It has a total population of 2.16 million across three provinces, Álava, Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya. Vitoria-Gasteiz is the region’s second largest city and also the capital and seat of the main governmental institutions. The Basque Country has one of the most dynamic regional economies in Spain, which acts as an attractor for migrants.

Three public primary schools located in Vitoria Gasteiz were included in this research. These three schools were selected because the proportion of immigrants in the student body is very high. Apart from being migrants, the families involved in the schools’ community have higher levels of economic vulnerability. While the public education system in the Basque Country is free, on the basis of a needs-based assessment families can also be eligible for financial aid to cover school expenses including teaching materials and the monthly school canteen fee. The proportion of families receiving these benefits can thus serve as a proxy indicator of the economic wellbeing of a school community. In the three schools included in this research the proportion of families receiving financial aid was very high which suggests endemic economic hardship including low wages, irregular and precarious employment and unemployment. All three schools were located in peripheral, working-class neighborhoods, and were built in the seventies and eighties (Laureau and Cox, 2011, Chapter 6). The choice of informants was therefore intentional and not probabilistic (Otzen and Materola, 2017).

Finally, before starting the field work, several meetings were held with school management and teaching teams to explain the research goals and process. In these preliminary meetings, school staff reported that these centers had an established trajectory of responding to ethno-cultural diversity and were currently carrying out different inclusion projects. Thus, another factor in selecting these three specific schools was that their management and educational teams claimed to be engaging in systematic efforts to encourage the participation of families through their educational projects.

The collaborative and participatory nature of this research project favored the emergence of meanings related to the role played by families in the teaching-learning process (Flick, 2012).

Participants in this study included 3rd and 4th grade students from the 3 schools, as well as educational staff. More specifically, 150 primary school students aged 9–10 and 17 adults belonging to the management and teaching teams participated.

Research ethics

To ensure that the research was conducted ethically, the project was presented to the Human Ethics Research Committee, CEISH-UPV/EHU, BOPV32, 2/17/2014, code M10_209_134, where it received a favorable assessment.

Following approval by the committee, the 3 schools selected were informed about the objectives of the research. Once these schools confirmed their institutional support, informed consent was granted by participating staff and families (Denzin and Lincoln, 2017). The anonymity and confidentiality of both the individuals and the schools was preserved at all times (Gibbs, 2012).

Instruments and procedures for data collection

The research addressed here was carried out between October 2019 and December 2021. Data was gathered from a total of 90 sessions of participant observation across the three schools. In order to guarantee a wider base of observational data, in all three centers different spaces of a diverse nature were chosen, that is, more regulated spaces such as classrooms and less regulated spaces including the patio and the students’ lunchroom space. During this participant observation process observations were collected through field notes (Angrosino, 2012).

Apart from observation, 17 semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with staff from the school management and teaching teams. The objective of the interviews, carried out horizontally (Flick, 2014), was to more deeply understand teachers’ knowledge from their own perspectives (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2018) around the main questions of interest in this study. The interviews were audio recorded with prior consent.

Finally, two discussion groups were held with the people who had earlier participated in the individual interviews. The questions asked in both interviews and the discussion groups were related to the daily educational practices in the schools and the types of collaboration between the different agents involved in the teaching-learning process (teachers, families, external professionals, etc.).

Information analysis procedures

Once the field notes and interviews were transcribed, the data was analyzed from a hermeneutical perspective (Fuster, 2019). For the analysis of this information, the data obtained from both observation and interviews was examined and a thematic content analysis was carried out using inductive-deductive categorization strategies (Leon and Montero, 2015). The Nvivo-12 software package was used to facilitate the analysis of the categories obtained.

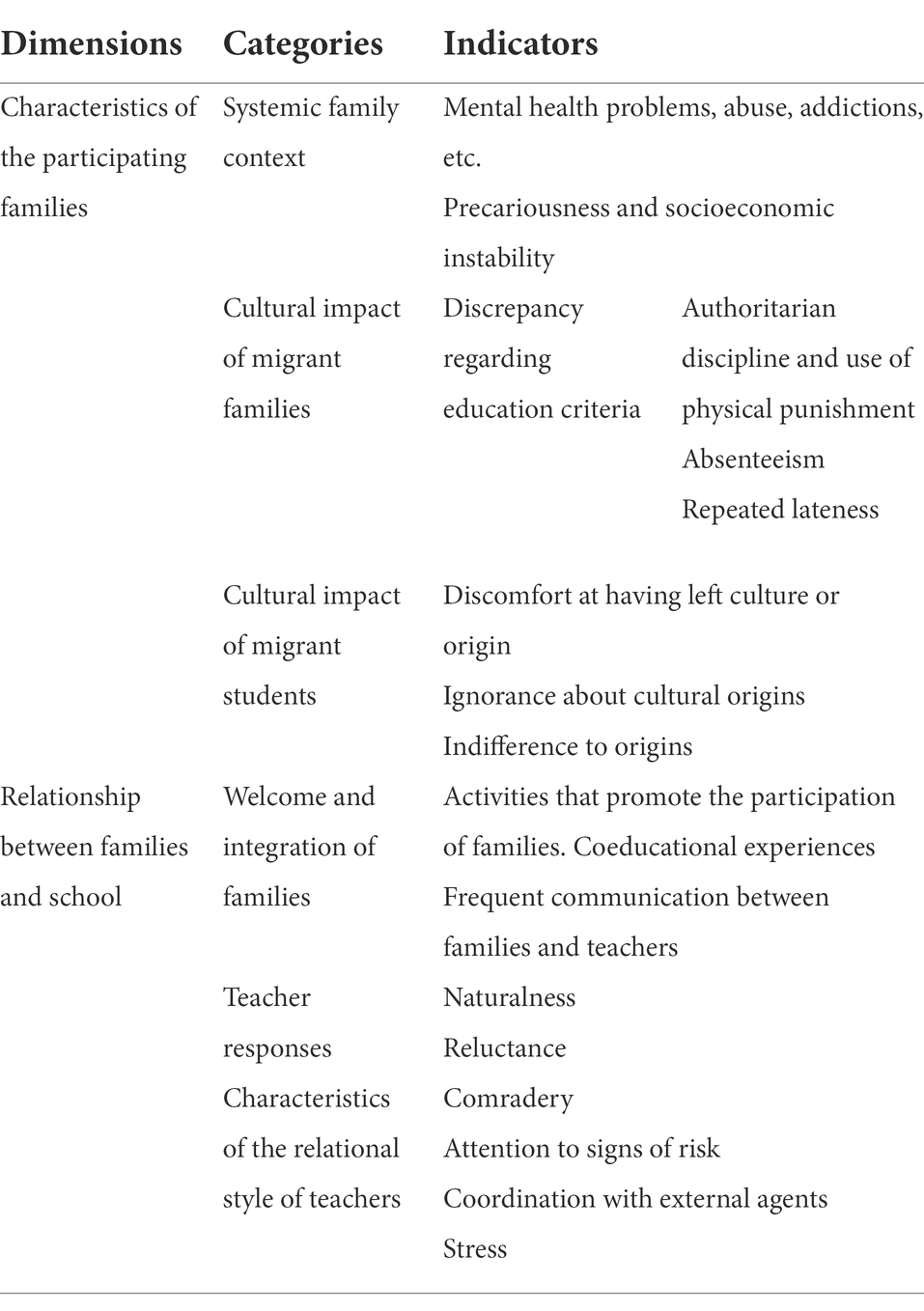

Subsequently, the information gathered in different categories was organized by subject matter into different groupings, called dimensions, as shown in Table 1. These dimensions in turn coincide with the thematic content used in the interviews and observations (Rapley, 2014).

Additionally, a system of identification codes was used. To preserve anonymity, despite the fact that the participating education professionals had different roles (principal, head of studies, consultant, tutor, support teacher, etc.), we decided to identify all participants as either teachers (T) or students (S). The three schools were identified as Center A (CA), Center B (CB) and Center C (CC). Finally, the different tools through which the information was obtained were differentiated: D (field diary); I (interview) and G (discussion group).

Finally, the triangulation of information became very important. This involved the cross-comparison of theory, material compiled through interviews, observations and reflection by the authors (Aguilar and Barroso, 2015; Denzin and Lincoln, 2017; Buetow, 2019).

Results

The two areas addressed focus first on teacher’s perception of their student’s families and, secondly, their perspectives on the relationship between these families and the school. More specifically, the first area includes issues related to the systemic context in which migrant families are situated and the impact they see this having on them and their children at a cultural level. The second area, the relationship between families and schools, encompasses issues related to the reception of families, the response of teaching staff to diversity and the characteristics of the relational style of the teaching staff.

Teachers’ perceptions of their student’s families

A significant proportion of the participating children came from dysfunctional households. Thus, the specific systemic context of these families was conditioned by indicators related to mental health problems, abuse, addictions, etc.

The tutor approached me and conveyed her concern for a student, Andrés. She explained “he does nothing.” She added that he had a tough situation at home: his mother was undergoing psychiatric treatment for depression. [T, CA, D]

In a quiet moment, the teacher gave me information about the class. She explained that two people had recently left and two new people, who were repeating the year, had just arrived: Ibrahim and one of the African girls, Johari. She explained that the girl’s mother had a restraining order against the father. She continued to give more information about the students. She told me about Henry. He was the second of three brothers and his mother attempted suicide when Henry was in preschool. [T, CB, D]

Relatedly, according to some of the people interviewed, the socioeconomic profile of the families in these schools was characterized by precariousness and socioeconomic instability. In general, the families with students enrolled in these schools faced economic difficulties. This can condition both educational styles and parenting models as well as children’s behavioral responses:

They are survivor families; they live one day at a time and they are just surviving. And that leaves its mark on their lifestyles and the educational style of each family. Their main concern is “what’s going to happen tomorrow?.” This also ends up being “school-bus school,” as they say. Today they live in this area, but Alokabide1 might allocate them a different flat and send them to Lakua or Bremen Street, so tomorrow they’ll be gone. Nobody handles uncertainty well, but if your life is already out of balance, uncertainty can sink you. In the end, the kids experience constant uncertainty at home and that doesn't help them. The reason isn’t that the families are… No, no… the reason is existential instability, that their lives in this society are in a fragile balance. [T, CC, G2]

It's the conditions, what surrounds them, it's very difficult. We have examples of single mothers who are at their absolute limit, that is, they do what they can, but it’s not easy. I think that at school the children are fine, they are taken care of, but the kids act out the fears that their families transmit to them in different ways. [T, CA, G1]

With respect to the existing ethnic-cultural diversity in these schools, some school staff pointed out the impact at a cultural level that both families and students experienced, especially immediately following their arrival. On some occasions, cultural elements of some families conflicted with the teaching and education criteria, value systems, discipline styles, etc. of the school.

In the school there is a large variety of families and also very different cultures. There are families from cultures that have very strict discipline at home, just like the discipline they used here in the '70s. For example, the Senegalese are very strict.… Punishment is used continually and the rules are very strict. The father above all is the one who has power at home, nobody stands against him. So, they come here, to a totally different context, they come into a society that is not governed by those norms. In class, for example, we try dialog, emotions… that they talk to each other, reason… But it is not always easy with the families. [T, CA, G1]

Moreover, some collectives involved in the different educational communities repeatedly had difficulties with some families because they used physical punishment with their children.

The tutor explained to me that Khaled was a student with serious behavioral problems. Today there was an internal meeting to assess the case. The student teacher told me with a surprised tone that Khaled's father was very severe and always punished his son very harshly by, for example, making him stand against the wall with his arms open for hours. [T, CC, D]

Some teachers stated that repression exercised in the home could produce adverse effects on children’s behavior, such as in the example below.

For example, with Nigerian families there is a problem. At school the children go haywire, Nigerian children react very strongly. However, when they are with their families, when we have a meeting with the family and the child, the children do not even move, they do not breathe in front of their family. [T, CA, I1]

As the principal of one center states in the following except, another problem was school absenteeism:

Last year we had a very serious problem. One child didn’t come to class for the whole year and I had to do an absenteeism report and in the end the case was taken to the Prosecutor's Office. All this gets passed on to Social Services; things are not isolated. When something like this happens, it's usually a much bigger issue. The boy's family asked if he could change to another school, because he had said he was being bullied here. (…). I said that if it was better for him, then I was in favor of the change. And, well, now he is in another school and it seems that he is doing well. I am very happy. I think the change was good for him. [T, CA, I1]

Another important issue was the repeated lateness of some students, which could, in the opinion of teachers, also be an indicator of another issue, such as family disorganization or lack of supervision by caregivers:

A new student, Aaron, joined the class late and asked in Spanish “Do we have a new teacher?” Nobody answered him. [S, CA, D]

Jasim joined the class late, but immediately started doing the activity. [S, CA, D]

Teacher’s perspectives on the relationship between families and schools

To promote truly inclusive education, the role played by schools is crucial, as schools are responsible for properly welcoming each family and respecting their idiosyncrasies.

We are the gateway to society for many families, many families have no other relationship with society than the one they have with us. So, we have to make sure that they feel comfortable here. After all, they are the future of our society. Nowadays, people here do not have children, and for society to move forward, families from other countries are necessary. And it’s also another opportunity to open doors, for them to get to know our culture, because if we don't, they probably won't have any other chance…. They should keep their culture, but we also have to maintain ours. [T, CA, I2]

Hence the importance that schools, and more especially learning communities, should place on their relationships with families by promoting activities that motivate their participation and involvement in the educational project. In these times in which a new school model is being constructed, more and more coeducational experiments are being carried out. In a large proportion of these projects, the participation of families is promoted, an issue that continues to be a challenge for these centers.

Our families have a an ISEC level2 that is even lower than it was seven years ago. The disadvantages families confront are becoming more and more marked. So, it is a continuous struggle that these families end up integrating into the school and the neighborhood. Yes, things are being achieved, families are increasingly participating in school activities. All this is thanks to the fact that there is a human team behind it, the commitment of the teachers is amazing, and goes far beyond just being a job. Otherwise… it would be impossible! [T, CC, G2]

One of the main purposes of these activities was to educate through the active participation of families and students, preparing them in turn to live in community under the principles and values of equality, respect for diversity, cooperation and justice (Saldaña, 2018).

Every year, at the first parents and teachers meeting, I invite them [parents] to come to my class, for example, to play an instrument from their country or to sing a song, or whatever. This year no one has volunteered. Other years there has been some participation and parents have come to class and we have done things: sing lullabies, play an instrument, a song from their country that they like a lot. To share, in the end it’s all about sharing and listening to different things because it is always enriching. [T, CB, I11]

To achieve this, frequent communication between teachers and families is essential in order to promote children’s socio-emotional development (Garreta-Bochaca, 2015). It was common, for example, for teachers to take advantage of non-teaching moments, such as recess and the lunch hour, to hold meetings with families.

The tutor told me that on Wednesdays she is usually on duty in the courtyard, but that day she had asked to change with another teacher to meet with a student’s parents. [T, CA, D]

During lunch time, they [the homeroom teacher] took the opportunity to meet a new student’s parents for the first time. [T, CA, D]

To contact the families, it was common for teachers to communicate through their students (sending written notes) or through ICT (e-mail, the school online platform, etc.). Sometimes the initiative could also come from families:

The tutor told [the students] that he would send a note to their parents by Gmail. Namir said “my mother doesn't have Gmail”. [S, CC, D]

The tutor gave them a note to take home: an invitation to tomorrow's assembly. [S, CC, D]

With respect to the teachers’ responses to the ethnic-cultural diversity of their students, this was taken on naturally, recognizing that it is a consequence of the changes in our society caused by globalization:

I think it’s a reflection of life, I don't think this diversity is characteristic only of this school. I think that diversity is characteristic of society and I’m not saying it’s negative. Most of these children were born here, what happens is that we still identify them as belonging to such and such a family because the family is from, I don't know what country, but most were born here, they were born in Vitoria. The families are from Africa, Nigeria, I also know that some are from Latin America, from Morocco, from Algeria, from Western Sahara. [T, CB, I3]

It is true that half are the children of migrants. This does not mean that these children weren’t born here. Most of them were born in Gasteiz, but the origin of their mothers and fathers or their cultural background is different. Most of all, we have [families] from Arab cultures and from Nigeria and then also from South America and from Burkina Faso, from Pakistan. But mostly, Arabs and Nigerians, apart from the Basques, are the most numerous. [T, CA, I2]

However, as reported in the interviews and discussion groups, for new staff members the initial reactions to this diversity were varied. This also depended on the prior experience and the origin of the individual teacher:

When I arrived, it was from another world. I came here straight from a school in a small town, where there were 17 children in a class that included two year-levels because the limit is 18. They were all blond, white. So, of course, I arrived here to a very different reality, which is Vitoria, where there were hardly any white people in class. It was weird, it was difficult for me to situate myself and I doubted if this was a place where I really should be. [T, CA, G1]

The first time I taught here I felt a bit uncomfortable because of the diversity. But over time I came to realize that despite the fact that one family is from Pakistan and another from Colombia, at a sociocultural or socioeconomic level they are very similar to each other, whether they have social integration problems or not. [T, CC, G2]

In general, in all three centers, commitment to the educational project, as well as the camaraderie among the teachers, were the main pillars that sustained the relationships established in the schools. It was common for teachers to take on roles and responsibilities that went beyond their job descriptions, prioritizing values such as camaraderie:

About the work environment with colleagues, I, for example, tell everyone in this school that I’ve never seen management put itself up here [above the teachers]. And I've been in a lot of schools that, well, management… “and that’s how it is because I say so and that's it” and I, for example, haven’t seen anything like that and that for me is at least one point in favor. Having the school leadership on your side. [T, CC, G2]

I chose this school because when I worked here as a relief teacher, I felt very welcome and, well, that left a big impression, a very positive impression on me and that's why I wanted to come to this school. I have felt very very welcomed, by my colleagues and by the last school leadership team. [T, CA, G1]

The teaching staff identified a constant necessity to respond urgently to the needs of their students. They noticed different signals that provided them with information about the well-being of their students in order to determine if alternative, more specialized approaches were necessary and, in the most serious cases, contacted Social Services for assistance:

The tutor told me that she was also worried about another student, Sonia. This girl had very noticeable dark circles around her eyes. She told me that tomorrow she had a meeting with the mother and added; “She has a Brigitte-esque style rage.” She also showed me some drawings she had on her desk drawn by Andrés. They were very aggressive drawings in which there were robots instead of people. [T, AC, D]

Ziad is still very serious and doesn't talk to anyone either. The tutor explained to me that it wasn’t the first time something had happened and that, on another occasion, the minor had accessed a page with pornographic content and that is why they [his classmates] made fun of him. She explained to me that teachers often checked everyone's browsing history, to know what they were searching for. [T, CC, D]

Schools frequently carried out work in ongoing coordination with external agents (Social Services, associations…) in order to be able to gather information that facilitated relationships with both students and families.

I think there are many behavioral problems, increasingly serious behaviors. Behind those behaviors… there is baggage. Those children have baggage and have suffered terribly. Yes, at the time we say: because this child, look what they did, they hit the teacher, they did this, but you see a child who is devastated. We follow up with them, with Social Services, with the families… Many of them are in supervised accommodation… [T, CA, I1]

We coordinate with external agents. If you belong to or have a relationship with an association or collective, the Afro-American or Gau Lacho Drom….3 Well, we also get in touch with them to see if the family situation is still ok or if something has changed. [T, CC, G2]

However, this alarming state of affairs generated discomfort and concern for teaching staff. Being fed up, fatigue and stress seemed to be the most frequent and sustained consequences over time. One of the direct repercussions of work overload and the bureaucratization of the system was stress:

We usually take a lot of work home. More than anything, we have a lot going on in our heads. I quite often talk to teachers who suffer from stress, who don’t sleep and I include myself among them. [T, CB, E11]

I talked briefly with the consultant and she explained to me that she was going to take some days off because she needed it. She talked about the stress she was under and added, “I just can't do everything I’m supposed to.” [T, CB, D]

Discussion and conclusions

This paper has analyzed and shared teachers’ perspectives on family-school relationships. In general terms, it contributes to the promotion of social justice in education, and schools which are genuinely for all (Echeita, 2018; Corres-Medrano et al., 2022). Specifically, by using an ethnographic research approach, we have sought to build knowledge through the participants by identifying and highlighting the practices and experiences of teachers that promote the participation of families.

As detailed in the emergent categories obtained, schools themselves condition the participation of families, especially more vulnerable families, to a significant degree, and this has repercussions on children’s socio-emotional development. In the three schools addressed in the study, teachers recognized that families had a lot to contribute to the teaching-learning process.

This study has focused on ways in which schools welcome new families. The existing literature (Nusche, 2009; Bernardi and Cebolla, 2014; Moreno, 2017; Arnaiz and Parrilla, 2019; Ceballos and Saiz, 2021, among others) argues that the participation of families in schools is a key element in teaching and learning processes and, consequently, in student’s socio-emotional development. Moreover, in the current era of globalization, the need to create educational networks based on collaborative and trusting relationships between all the actors participating in schools, where families, students and teachers interact, has become more evident than ever (Santizo, 2011; Carneros and Murillo, 2017).

We focused on three public schools affected by school segregation that, in order to manage the ethnic-cultural diversity of the families in their school communities and promote the social inclusion of all their students, demonstrated a special sensitivity to collaboration with families. As was shown in the interviews, schools were important as spaces that promoted interpersonal relationships, and this was contingent on a positive vision of ethical-cultural diversity. Participants provided information related to the importance of educational practices from an inclusive perspective. An essential prerequisite to guarantee a real inclusion of migrant children in a way that responds to their basic needs and rights is that their families feel welcomed by schools (Simón and Barrios, 2019). Teacher-family collaboration is therefore indispensable to support children to achieve their maximum potential (Martínez-Garrido and Murillo, 2016).

In the three schools analyzed, constructive relationships between families and school were considered very important and necessary. In this sense, the three participating schools all understood that carrying out educational projects demands that families participate in the initiatives. The work carried out by one of the centers, considered a learning community, stands out. In its educational project it also recognized the primary role of neighborhood associations, neighborhood social services, cultural and social groups, etc. It considered that including all the agents participating in the community was the true guarantee of a real inclusion of migrant children and their families.

Another issue that teachers recognized was that of their involvement, not only professionally but personally, in school projects. A political commitment by staff can promote relationships with families and their participation in the day-to-day running of the school, which in turn enriches the teaching process (Vigo and Deste, 2017).

Teachers’ contributions emphasized issues such as the need for training adapted to the specific needs of their schools and for a critical and reflective attitude about professional practice. This critical reflection on professional practice can form part of teachers’ professional development (Vigo et al., 2016).

As has been stated repeatedly in this work, the results show that the segregation characteristic of the participating schools does not favor the inclusion of migrant children or the participation of families. Despite good intentions and political will, today the concentration of the most socially vulnerable children in certain schools continues to occur, a fact that violates their right to participate on equal terms (Echeita and Ainscow, 2011; Messiou, 2019). For these reasons, it is necessary to take a step beyond schools and families. As one of participating centers also clearly identified, the results of this paper once again highlight the need to recognize the fundamental role of all the agents involved in the community to which a school belongs (Flecha and García-Yeste, 2004). For this reason, there is an urgent need to build channels of communication and relationships between the community, families and schools in order to guarantee the fulfillment of the rights of all children, but particularly migrant children (Etxebarria and Sagastume, 2013; Hernández-Hernández et al., 2021).

One of the main limitations of this study was due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, as not all the people who initially participated in the observation sessions and individual interviews participated in the discussion groups held later. During the second phase of the research, one of the schools declined the invitation to participate in focus groups, stating that staff were overwhelmed by the process of adaptation to post-pandemic reality. In addition, due to the passage of time and the instability characteristic of employment in public schools in the Basque Country, many people who participated in the initial phases of this research were no longer working at the centers involved in the research. The possible effects caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, especially on disadvantaged families, would be a valuable topic for further research.

On the other hand, while the research presented here is part of a larger school ethnography focused mainly on the impact of school segregation on the socio-emotional development of children at risk, the non-inclusion of families in this paper is another limitation that must be recognized. Not including families’ perspectives may have led to a certain bias in the interpretation of the results. Relatedly, not assessing the possible impact of language barriers on families’ participation must be considered another limitation. Therefore, with respect to future extension of this research, the perspectives of both families and schools should be taken into account. This would involve adapting to and taking into consideration the impact of linguistic barriers both in terms of analysis and at the practical level of conducting interviews.

In short, we believe that the contributions made by this paper form a useful basis for future projects aimed at teacher training to improve professional practice, especially for staff working in public schools with high levels of segregation. The results show that a great deal of work is still being done on how schools can welcome new students and their families in a way that favors the inclusion of more vulnerable students. However, they also show that responses made from an inclusive perspective are subject to individual idiosyncrasies and the particular educational project of each school. In other words, there does not seem to be a common position regarding the inclusion of families in the response of schools with an inclusive approach. Therefore, it is concluded that further changes must still be made in the educational system to promote academic success and guarantee the real social inclusion of all students and their families and in all schools (Ahad and Benton, 2018).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Ethics Research Committee, CEISH-UPV/EHU, BOPV32, 2/17/2014, code M10_209_134. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

IC-M was the primary author of the manuscript, conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft, preparation, project administration, and funding acquisition. IC-M and IS-G: methodology, investigation, and resources. IC-M, KS-E, and IF-V: writing—review and editing and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^An organism of the Basque Government that manages public housing in the Basque Country.

2. ^ISEC is the acronym for a socioeconomic and cultural indicator that brings together a variety of information from different sources about students’ family and social context, including their parents’ professions and level of education, family resources, etc.

3. ^Gau Lacho Drom is a Roma association in Vitoria-Gasteiz offering specialized services to its community.

References

Aguilar, S., and Barroso, J. (2015). La triangulación de datos como estrategia en investigación educativa [Data triangulation as a strategy in educational research]. Píxel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación 47, 73–88. doi: 10.12795/pixelbit.2015.i47.05

Ahad, A., and Benton, M. (2018). Mainstreaming 2.0. How Europe Education System Can Boost Migrant Inclusion, Integration Futures Working Group. Migration policy institute Europe. Cundinamarca, Colombia: Universidad de La Sabana.

Alkorta, E., and Shershneva, J. (2021). Perfiles del alumnado de origen extranjero en centros con elevada presencia de escolares inmigrantes en el País Vasco [profiles of students of foreign origin in schools with a high presence of immigrant students in the Basque Country]. Empiria, Revista de metodología de ciencias sociales 51, 15–43. doi: 10.5944/empiria.51.2021.30806

Altarejos, F., Bernal, A., and Rodríguez, A. (2005). La familia, escuela de sociabilidad [the family, school of sociability]. Educación y educadores 8, 173–185. Available at: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=83400813

Angrosino, M. (2012). Etnografía y observación participante en Investigación Cualitativa [Ethnography and Participant Observation in Qualitative Research]. Morata. Madrid, Spain.

Ararteko, (2011). Infancias vulnerables [Vulnerable Children] Ararteko Available at: https://www.ararteko.net

Arnaiz, P., and Parrilla, A. (2019). La inclusión educativa y social a debate, nota editorial [Educational and social inclusion under debate, editorial note]. Publicaciones 49, 7–17. doi: 10.30827/publicaciones.v49i3.11401

Bernardi, F., and Cebolla, H. (2014). Clase social de origen y rendimiento escolar Como predictores de las trayectorias educativas [Social class of origin and school performance as predictors of educational trajectories]. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 146, 3–22. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.146.3

Bisquerra, R. (2016). Metodología de la investigación educativa [Methodology of Educational Research]. Madrid, Spain La Muralla.

Bolívar, A. (2006). Familia y escuela: dos mundos llamados a trabajar en común [Family and school: two worlds called to work together]. Revista de Educación 339, 119–146. Available at: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/revista-de-educacion/numeros-revista-educacion/numeros-anteriores/2006/re339/re339-07.html

Bonal, X. (2018). La política educativa ante el reto de la segregación escolar en Cataluña [Educational Policy in the Face of the Challenge of School Segregation in Catalonia]. El Instituto Internacional del Planeamiento de la Educación, Unesco. Paris, France.

Bourdieu, P., and Passeron, J. C. (2021). Los herederos: los estudiantes y la cultura [Heirs: Students and Culture]. Clave Intelectual. Madrid, Spain.

Bryan, J., and Henry, L. (2012). A model for building school–family–community partnerships: principles and process. J. Counseling Dev. 90, 408–420. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00052.x

Buetow, S. (2019). Apophenia, unconscious bias and reflexivity in nursing qualitative research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 89, 8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.013

Cambil, M. E., and Romero, G. (2018). “Los entornos socioculturales de referencia en la Educación Infantil: familia y escuela [The sociocultural reference environments in early childhood education: family and school],” in Entorno, sociedad y cultura en Educación Infantil. Fundamentos, propuestas y aplicaciones. eds. A. Bonilla and Y. Y. Guasch (Madrid,Spain Pirámide), 117–134.

Carneros, S., and Murillo, F. J. (2017). Aportaciones de las escuelas alternativas a la justicia social y ambiental: autoconcepto, autoestima y respeto [Contributions of alternative schools to social and environmental justice: self-concept, self-esteem and respect]. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 15.3, 129–150. doi: 10.15366/reice2017.15.3.007

Ceballos, N., and Saiz, Á. (2021). Un proyecto educativo común: la relación familia y escuela. Revisión de investigaciones y normativas [A common educational project: the relationship between family and school. Review of research and regulations]. Educatio siglo XXI 39, 305–326. doi: 10.6018/educatio.469301

Cebolla-Boado, H., Radl, J., and Salazar, L. (2016). Educational disadvantage in a changing economic context. Afduam 20, 279–304. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/681250

Corres-Medrano, I., Aristizabal, P., and Ozerinjauregi, N. (2022). La autoridad en la era inclusiva: un estudio de Caso con niños y niñas de educación primaria [Authority in the inclusive era: a case study with primary school children]. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 97, 225–242. doi: 10.47553/rifop.v97i36.1.87584

Cotán, A. (2020). El método etnográfico como construcción de conocimiento: un análisis descriptivo sobre su uso y conceptualización en ciencias sociales [The ethnographic method as knowledge construction: a descriptive analysis of its use and conceptualization in social sciences]. Márgenes, Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Málaga 1, 83–103. doi: 10.24310/mgnmar.v1i1.7241

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2017). Manual de investigación cualitativa. El arte y la práctica de la interpretación, la evaluación y la presentación [Handbook of Qualitative Research. The Art and Practice of Interpretation, Evaluation, and Presentation]. vol. V Gedisa. Barcelona, Spain.

Dovemark, M., and Beach, D. (2014). Academic work on a Back-burner: habituating students in the upper-secondary school towards marginality and a life in the Precariat. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 19, 583–594. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2014.961676

Echeita, G. (2018). Educación para la inclusión o educación sin exclusiones [Education for Inclusion or Education Without Exclusión]. Narcea. Madrid, Spain

Echeita, G., and Ainscow, M. (2011). La educación inclusiva como derecho. Marco de referencia y pautas de acción para el desarrollo de una revolución pendiente [Inclusive education as a right. Framework of reference and action guidelines for the development of a pending revolution]. Tejuelo 12, 26–46. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/661330

Epstein, J. L. (2011). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools. Boulder, Colorado, United States: Westview Press.

Escribano, A., and Martínez, A. (2016). Inclusión educativa y profesorado inclusivo. Aprender juntos Para aprender a vivir juntos [Educational Inclusion and Inclusive Teachers. Learning Together to Learn to Live Together]. Narcea. Madrid, Spain.

Etxebarria, F., and Sagastume, N. (2013). La percepción de los tutores sobre la implicación educativa de las familias inmigrantes en la comunidad autónoma del País Vasco [the perception of tutors on the educational involvement of immigrant families in the autonomous Community of the Basque Country]. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado REOP 24, 43–62. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.24.num.3.2013.11244

Flecha, A., and García-Yeste, C. (2004). James P. comer: los niños y niñas trabajarán hasta donde tú esperes que lo hagan [James P. comer: children will work as hard as you expect them to]. Cuadernos de pedagogía 341, 86–89. Available at: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/artpub/2004/164121/cuaped_a2004m12n341p86.pdf

Flick, U. (2012). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa [Introduction to Qualitative Research]. Morata. Madrid, Spain.

Flick, U. (2014). El diseño de la Investigación cualitativa [The Design of Qualitative Research]. Morata. Madrid, Spain.

Fuster, D. E. (2019). Investigación cualitativa: Método fenomenológico hermenéutico [Qualitative research: phenomenological hermeneutic method]. Propósitos y representaciones 7, 201–229. doi: 10.20511/pyr2019.v7n1.267

Garreta-Bochaca, J. (2015). La comunicación familia-escuela en Educación Infantil y Primaria [Family-school communication in kindergarten and primary education]. Revista de Sociología de la Educación-RASE 8, 71–85. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4993813.pdf

Gibbs, G. (2012). El análisis de datos cualitativos en Investigación cualitativa [The Analysis of Qualitative Data in Qualitative Research]. Morata. Madrid, Spain

Hernández-Hernández, F., Sancho-Gil, J. M., and Arroyo-González, M. J. (2021). The importance and necessity of researching emigration and its relationship with school education. Culture Educa. 33, 585–596. doi: 10.1080/11356405.2021.1987070

Horvat, E. M., Weininger, E. B., and Lareau, A. (2003). From social ties to social capital: class differences in the relations between schools and parent networks. Am. Educ. Res. Assoc. 40, 319–351. doi: 10.3102/00028312040002319

Lahire, B. (2008). “Un sociólogo en el aula: objetos en juego y modalidades [A sociologist in the classroom: objects in play and modalities],” in ¿Es la escuela el problema? Perspectivas socio-antropológicas de etnografía y educación [Is School the Problem? Socio-Anthropological Perspectives on Ethnography and Education]. eds. M. I. Jociles and A. Franzé (Madrid, Spain Trotta), 49–60.

Lareau, A., and Horvat, E. M. (1999). Moments of social inclusion and exclusion race, class, and cultural capital in family-school relationships. Sociol. Educ. 72, 37–53. doi: 10.2307/2673185

Laureau, A., and Cox, A. (2011). “Chapter six Social class and the transition to the adulthood,” in Social class and changing families in an unequal America, eds. M. J. Carlson and P. England. Redwood: Stanford University Press., 134–164

Leon, O. G., and Montero, I. (2015). Metodología de la investigación en psicología y educación [Research Methodology in Psychology and Education]. New York, New York, United States: McGraw-Hill.

López, F. (2008a). Familias convencionales: algunos criterios para la educación infantil [Conventional families: some criteria for early childhood education]. Padres y maestros 314, 26–29. Available at: https://revistas.comillas.edu/index.php/padresymaestros/article/view/1558

López, F. (2008b). Necesidades en la infancia y en la adolescencia: Respuesta familiar, escolar y social [Childhood and Adolescent Needs: Family, School and Social Response]. Madrid, Spain Pirámide.

Marcus, G. E. (2001). Etnografía en/del sistema mundo. El surgimiento de la etnografía multilocal [Ethnography in/of the world system. The emergence of multilocal ethnography]. Alteridades 11, 111–127. Available at: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=74702209

Martínez, L., and Ferrer, A. (2018). Mézclate conmigo. De la segregación socioeconómica a la educación inclusiva [Mingle with me. From socioeconomic segregation to inclusive education]. Save the Children Spain.

Martínez-Garrido, C., and Murillo, F. J. (2016). Incidencia de la distribución del tiempo no lectivo de los docentes en Educación Primaria en el aprendizaje de sus estudiantes [Effect of the distribution of non-teaching time of primary school teachers on student learning]. RELIEVE 22:art. 1. doi: 10.7203/relieve.22.2.9433

Maturana, G. A., and Garzón, C. (2015). La etnografía en el ámbito educativo: una alternativa metodológica de investigación al servicio docente [Ethnography in the educational field: a methodological alternative for research to support teaching]. Revista Educación y Desarrollo Social 9, 192–205. doi: 10.18359/reds.954

McNamara, J. M., Houston, A. I., Barta, Z., and Osorno, J. L. (2003). Should young ever be better off with one parent than with two? Behavioral Ecology, 14, 301–310. doi: 10.1093/beheco/14.3.301

Messiou, K. (2019). The missing voices: students as a catalyst for promoting inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 23, 768–781. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1623326

Moreno, G. (2017). “La visión de personas expertas [The view of experts],” in La diversidad infantil y juvenil en la CAE. Las (mal) llamadas segundas generaciones [Child and youth diversity in the Basque Country. The (wrongly) called second generations]. eds. I. M. Fouassier, T. Arteta, M. J. Martín, and O. Ochoa de Aspuru (Bilbao, Basque Country, Spain Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco), 93–142.

Moreno, D., Estévez, E., Murgui, S., and Musitu, G. (2009). Relación entre el clima familiar y el clima escolar: el rol de la empatía, la actitud hacia la autoridad y la conducta violenta en la adolescencia [Relationship between family and school environments: the role of empathy, attitudes towards authority and violent behavior in adolescence]. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 9, 123–136. Available at: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56012876010

Murillo, J., and Martínez-Garrido, C. (2018). Magnitud de la segregación escolar por nivel socioeconómico en España y sus Comunidades Autónomas y comparación con los países de la Unión Europea [Magnitude of school segregation by socioeconomic level in Spain and its Autonomous Communities and comparison with European Union countries]. RASE. Revista de Sociología de la Educación 11, 37–58. doi: 10.7203/RASE.11.1.10129

Murillo, F. J., and Martínez-Garrido, C. (2019). Perfiles de segregación escolar por nivel socioeconómico en España y sus Comunidades Autónomas [School segregation profiles by socioeconomic level in Spain and its Autonomous Communities]. RELIEVE, Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa 25, 1–20. doi: 10.7203/relieve.25.1.12917

Murillo, F. J., Martínez-Garrido, C., and Belavi, G. (2017). Segregación escolar por origen nacional en España [School segregation by national origin in Spain]. OBETS. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 12, 395–423. doi: 10.14198/OBETS2017.12.2.04

Nusche, D. (2009). What works in migrant education? A review of evidence and policy options. OECD education working papers, 22.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2010). Overcoming Failure at School: Policies that Work. OECD Project Description OECD Publishing Available at: www.oecd.org/dataoecd/54/54/45171670.pdf.

Otzen, T., and Materola, C. (2017). Técnicas de muestreo sobre una población a estudio [Sampling techniques for a population study]. Int. J. Morphol. 35, 227–232. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022017000100037

Rapley, T. (2014). Los análisis de conversación, de discurso, y de documentos en Investigación Cualitativa [Conversation, discourse, and document analysis in qualitative research]. Morata Madrid, Spain.

Rasbash, J., Leckie, G., and Pillinger, R. (2010). Children's educational progress: partitioning family, school and area effects. J. R. Stat. Soc. A. Stat. Soc. 173, 657–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2010.00642.x

Rebolledo, M., and Elosu, N. (2009). Orientaciones Metodológicas. Proyecto de intervención coeducativa con el alumnado de educación infantil y primeros ciclos de primaria [Methodological orientations. Coeducational intervention project with students in kindergarten and early primary school]. Dirección General de la Mujer.

Saldaña, D. (2018). Reorganizar el patio de la escuela, un proceso colectivo para la transformación social [Reorganizing the schoolyard, a collective process for social transformation]. Hábitat y sociedad 11, 185–199. doi: 10.12795/HabitatySociedad.2018.i11.11

Santizo, C. (2011). Gobernanza y participación social en la escuela pública [Governance and social participation in public schools]. RMIE, Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa 16, 751–773. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/revista?codigo=2119

SiiS Fundación Eguía-Careaga Fundazioa (2017). Estudio diagnóstico de la situación de la infancia y la adolescencia en Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2017 [Diagnostic Study of the Situation of Children and Adolescents in Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2017]. Ayuntamiento de Vitoria-Gasteiz. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Basque Country, Spain.

Simón, C., and Barrios, A. (2019). Las familias en el corazón de la educación inclusiva [Families at the heart of inclusive education]. Aula abierta 48, 51–58. doi: 10.17811/rifie.48.1.2019.51-58

Smith, M. (2019). Las emociones de los estudiantes y su impacto en el aprendizaje. Aulas emocionalmente positives [Students' Emotions and Their Impact on Learning. Emotionally Positive Classrooms]. Narcea. Madrid, Spain

Texeira, A. A. C. (2016). The impact of class absenteeism on undergraduates’ academic performance: evidence from an elite economics school in Portugal. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 53, 230–242. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2014.937730

Valdés, A. A., and Sánchez, P. A. (2016). Las creencias de los docentes acerca de la participación familiar en la educación [Teachers' beliefs about family involvement in education]. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 18, 105–115. http://redie.uabc.mx/redie/article/view/1174

Vigo, M. B., and Dieste, B. (2017). Contradicciones en la educación inclusiva a través de un estudio multiescalar [Contradictions in inclusive education through a multiscale study]. Aula abierta 46, 25–32. doi: 10.17811/rifie.46.2017.25-32

Vigo, B., Dieste, B., and Thurston, A. (2016). Aportaciones de un estudio etnográfico sobre la participación de las familias a la formación crítica del profesorado en una escuela inclusiva [Contributions of an ethnographic study on family involvement to critical teacher training in an inclusive school]. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 19, 1–14. Available at: https://revistas.um.es/reifop/article/view/246341

Vigo, B., and Soriano, J. (2015). Family involvement in creative teaching practices for all in small rural schools. Ethnogr. Educ. 10, 325–339. doi: 10.1080/17457823.2015.1050044

Vigo-Arrazola, B., and Dieste-Gracia, B. (2019). Building virtual interaction spaces between family and school. Ethnogr. Educ. 14, 206–222. doi: 10.1080/17457823.2018.1431950

Vigo-Arrazola, B., and Dieste-Gracia, B. (2020). Identifying characteristics of parental involvement: aesthetic experiences and micro-politics of resistance in different schools through ethnographic investigations. Ethnogr. Educ. 15, 300–315. doi: 10.1080/17457823.2019.1698307

Keywords: family, school segregation, participation, inclusion, qualitative research

Citation: Corres-Medrano I, Santamaría-Goicuria I, Fernandez-Villanueva I and Smith-Etxeberria K (2022) The role of families in the response of inclusive schools: A case study from teacher’s perspectives. Front. Educ. 7:970857. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.970857

Edited by:

Juana M. Sancho-Gil, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Gina Kallis, University of Plymouth, United KingdomPaola Dusi, University of Verona, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Corres-Medrano, Santamaría-Goicuria, Fernandez-Villanueva and Smith-Etxeberria. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Irune Corres-Medrano, aXJ1bmUuY29ycmVzQGVodS5ldXM=

Irune Corres-Medrano

Irune Corres-Medrano Imanol Santamaría-Goicuria2

Imanol Santamaría-Goicuria2 Klara Smith-Etxeberria

Klara Smith-Etxeberria