95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 28 September 2022

Sec. Digital Learning Innovations

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.965659

This article is part of the Research Topic Digital Learning Innovations in Education in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic View all 17 articles

The COVID-19 pandemic forced most educational institutions in the US to quickly transfer to emergency remote teaching, finding many instructors and students unprepared. This study explored university students’ perspectives in a composition course during the emergency period and proposes guidance on designing a “student-friendly” online learning environment. This study examines the students’ concerns about and challenges with emergency remote teaching, the course’s benefits during the online learning period, and students’ recommendations for improvement. The research was conducted in seven sections of a multimodal composition course at a large, Midwestern university. Participants responded to a virtual discussion board at the beginning of online instruction and a survey after online instruction. Qualitative analysis of responses—guided by the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework—showed that the participants expressed challenges with staying motivated, completing coursework, and feeling socially disconnected from instructors and classmates. Benefits expressed by the participants included increased flexibility in their schedules, improved time management skills, and increased virtual communication with instructors. This study highlights suggestions that can guide the design of composition courses and pedagogical practices for emergency remote teaching in the future.

Writing skills are considered crucial for academic success for college students regardless of their discipline due to the fact that students are evaluated through writing in almost every type of college course (Conley, 2007). Therefore, many colleges and universities offer writing support through mandatory composition courses. These courses aim to bridge the gap between learners’ writing skills acquired in secondary school and the skills required to succeed at the college level and beyond. The writing skills that students gain through these courses are also highly important for employment after graduation (e.g., Kassim and Ali, 2010; Pandey and Pandey, 2014; Weldy et al., 2014). At the authors’ institution and many others, these mandatory composition classes have historically been offered in a face-to-face classroom context, with only a few sections, if any, being offered in an online format each semester. Regular in-class peer review workshops (Jensen, 2016), small group activities (Hunzer, 2014), and student-instructor conferences (Patthey-Chavez and Ferris, 1997) are staples of this type of composition class, which made the switch to online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic a dramatic transition. When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in March of 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020), most educational institutions in the United States were forced to quickly transfer to online courses (Crawford et al., 2020), finding many instructors and students unprepared. Research on online learning before the COVID-19 pandemic that explored students’ perceptions did not find any significant difference between students’ progress in online and conventional versions of writing courses (e.g., Mehlenbacher et al., 2000), and research has differed with regard to the effectiveness of online learning for college courses in general (cf. Phipps and Merisotis, 1999; Johnson et al., 2000). When taking online courses was a choice, not a mandate, online courses were rated lower than face-to-face courses and the students showed a preference for face-to-face courses (Lowenthal et al., 2015). Possible reasons for this included the perception of not having “a real or a human teacher” and the importance of social presence in online courses (Tichavsky et al., 2015, p. 6).

However, with the sudden outbreaks of COVID-19, a shift to online learning became inevitable globally. Online instruction in a regular situation is quite different from online instruction during emergency periods: Whereas regular online instruction is designed to be delivered virtually, online instruction during emergency periods must be developed quickly to provide students with temporary access to course content that would otherwise be presented face-to-face. This study provides an insight into students’ experiences with the transition to emergency remote teaching in an introductory writing course. Students’ feedback provides valuable data to guide us toward better course designs—particularly those focused on learner-centered education—and improved student engagement in future online courses.

This article will begin with a review of relevant literature. It will then describe the methodology used, present the findings, and provide a discussion and recommendations based on them. Finally, this article draws conclusions about the implications of this study.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) defines distance education as “education that uses one or more technologies to deliver instruction to students who are separated from the instructor and to support regular and substantive interaction between the students and the instructor synchronously or asynchronously” (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2020, p. 307). According to the NCES, approximately 34% of all undergraduate students in the United States participated in at least one distance education course in fall 2018, compared to only 8% of undergraduate students in 2000. Additionally, 14% of undergraduates were enrolled exclusively in distance education, which has increased from 2% in 2000 (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2011, 2020). Clearly, online education has grown significantly in the last two decades, especially as US institutions are experiencing increasingly high enrollment numbers and must look for new ways to economically meet the increasing demand for higher education (Tichavsky et al., 2015). As Daymont et al. (2011) pointed out, online education alleviates the strain on the amount of physical space required for classes on campus and provides schedule accommodations for students.

Despite the clear economical and practical benefits of online learning, several past studies discovered that students still reportedly favored face-to-face classes over online (e.g., Diebel and Gow, 2009; Delaney et al., 2010; Tichavsky et al., 2015), with the most prominent reasons being a preference for the teacher’s presence in class and challenges with self-regulated learning (Tichavsky et al., 2015). Tichavsky et al. (2015) further sought to investigate this phenomenon by looking into whether students’ preferences were based on preconceived perceptions of online learning or their actual experiences with it. They found that one primary pattern that emerged to explain students’ aversion to online learning was that students perceived online learning as an independent form of learning and one that lacked interaction with peers and instructors. Kaur and Joordens (2021) provided guidelines to make online learning more effective. In their literature review, the authors discussed the most significant factors that contributed to the success of online learning. Amongst other items, satisfaction and motivation of the students appear in the list of 16 factors.

Relatedly, Ritthipruek (2018) argued that the digital-native students of today’s classrooms benefit from elaborate technology-based learning environments to stay engaged and interested in classroom material. However, Ritthipruek (2018) also found that students expressed that they learned best with a blend of different modes of learning, including worksheets, game-based practice, and multimedia. Therefore, they recommended a blended learning model to increase student performance and maintain learner engagement.

Tichavsky et al.’s (2015) and Ritthipruek’s (2018) studies both reflect some of the main ideas of learner-centered education (LCE)—the idea that teaching should focus on the individual needs of learners (Badjadi, 2020). Past research has indicated that implementing LCE methods can be challenging for instructors (e.g., Bai and González, 2019). Despite these challenges in implementation, LCE has been shown to motivate students, develop their communication skills, and stimulate personal growth (Villacís and Camacho, 2017; Ahmed and Dakhiel, 2019; Van Viegen and Russell, 2019). Therefore, it is worth considering how instructors can effectively design their courses to support the ideas of LCE, especially in the context of increasingly common online education.

Remote learning, online learning, and emergency remote teaching carry different meanings and requirements. The phrase remote learning has been used to emphasize the geographically flexible aspect of education whereas with online learning, the use of technology is emphasized in the learning process (Moore et al., 2011). Emergency remote teaching (ERT), on the other hand, has a temporary nature resulting from an emergency situation (Barbour et al., 2020). While there is a considerable amount of planning and organization behind online and remote teaching (Hodges et al., 2020), in an emergency situation, the same amount of planning and organization might not be achieved. As educational institutions react to crises, they must develop ways to provide students with temporary access to education that would otherwise be presented face-to-face. ERT has been defined as “a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate delivery mode due to crisis circumstances” (Hodges et al., 2020). Whereas traditional online learning is a preference, where the student exercises their right to choose between face-to-face and in-person education, ERT is a forced situation in which choice is taken away from the students and other stakeholders. ERT has already been shown to have negatively impacted several aspects of students’ educational experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Sarikaya (2021) found low levels of student motivation for writing, which was attributed to a lack of access to the technological tools to support timely feedback. Reduced student concentration (Shim and Lee, 2020) and disengagement due to assignment design (Ismailov and Ono, 2021) have also been reported during the period of ERT due to COVID-19.

During periods of ERT, a shift in focus from the course content to providing support for students during these challenging times might be more helpful (Bozkurt and Sharma, 2020), as that is what the students will remember from the course. Bozkurt and Sharma (2020) note that during periods of ERT, students often are told to simply watch lectures, but they suggest that it is more important to focus on building a community for the students to have meaningful interactions. One way that many instructors may create these meaningful interactions online is by implementing discussion boards. As Wikle and West (2019) suggest, discussion boards may evoke that sense of community that students seek at this time, but instructors should keep in mind that depending on the topic’s difficulty, it may not facilitate learning.

Though it is important to focus on supporting students, faculty needs in this situation must also be considered. Most instructors who went online during the COVID-19 pandemic had no online teaching experience (Johnson et al., 2020; Trust and Whalen, 2020). Hodges et al. (2020) note, “The rapid approach necessary for ERT may diminish the quality of the courses delivered” as substantial planning and preparation is required to develop a quality online course. Therefore, instructors experiencing ERT need support, including resources to improve their classroom practices from home. However, when asked what assistance administrators and faculty needed during the shift to ERT, the most common response was support for students (Johnson et al., 2020). Therefore, it appears that the needs of the students were the number one priority when classes shifted online, reflecting a focus on LCE. Some previous studies have investigated the ways in which instructors have prioritized LCE even when temporarily shifting classes online during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, researchers have studied student-centered interactions in online English-as-a-second-language classrooms (Bamidele, 2021), graduate veterinary programs (Gonçalves and Capucha, 2020), and lab-based learning in STEM disciplines (West et al., 2021) during COVID-19. Few studies, if any, have proposed guidelines for LCE in online undergraduate composition courses or investigated students’ perceptions of such courses during emergency periods. The present study aims to fill this gap. Schools, teachers, and even the educational technology (EdTech) industry are learning from this shift to ERT (Williamson et al., 2020), and the adjustments made will have long-term implications for the future of education.

To effectively assess course design concerning LCE and ERT, it is necessary to consider a framework that can be used as a guide for evaluation. The Community of Inquiry (CoI) is one such framework that has been used as a “guide to educators for the optimal use of computer conferencing as a medium to facilitate an educational transaction” (Garrison et al., 1999, p. 87). CoI has been defined as an educational framework in which learners experience social, teaching, and cognitive presence through scientific inquiry. Garrison (2009) describes social presence as participants’ sense of belonging to the community they are in and their communication with this community in meaningful and deliberate ways. Social presence should also include open communication, group cohesion, and affective expression. Teaching presence involves designing and implementing the course, facilitating discourse among students, and directly instructing students. Finally, according to Garrison (2007), cognitive presence is related to learners’ understanding of the course and what is required, and it is achieved through events that trigger learning, exploration of ideas, integration and connection of ideas, and the application of new ideas.

The use of CoI in a learning environment signifies a purposeful and supportive collaboration between the teacher and the students, and thereby knowledge is constructed in a trusted environment (Garrison, 2006). Past research confirms this, with results indicating that students who feel a sense of belonging and are content with the course are more successful (Akyol and Garrison, 2008; Morris, 2010). The sense of belonging in online courses seems to be achieved through discussion boards as a way to communicate and interact with other learners in the course and the teacher (Morris, 2010). According to Morris (2010), this kind of interaction increased the involvement of the individual learners in the course, which in turn increased their success.

Many researchers have used the CoI framework, and so far, it has been shown that it is a useful theoretical framework and a suitable tool to investigate and design online learning experiences (Akyol and Garrison, 2008). Nonetheless, online learning experiences might differ from online learning in emergency situations, such as the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. How students perceive social, teaching, and cognitive presence through scientific inquiry during these extenuating circumstances in a university level writing course is yet to be explored. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the students’ concerns about and challenges with emergency remote teaching, the course’s benefits during the online learning period, and students’ recommendations for improvement through the lens of the CoI framework to provide suggestions and insights for the design of future courses.

This study explores students’ perceptions of a composition course during the emergency remote period and proposes guidance on designing a learner-centered online education environment. This study examines the students’ concerns, challenges, perceived benefits, and recommendations for improvement.

While coping with a global crisis, this quick transition to online learning found many students unprepared and unfamiliar with online learning. Thus, the researchers strongly believe that exploring students’ perceptions is of the utmost importance and will provide support in similar emergency situations in the future. This study may also contribute to understanding features of learning environments that influence engagement—including physical, social, and technological contexts—and serve as general guidance for the design of online composition courses.

The present study was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the students’ concerns and challenges with online learning in a writing course during COVID-19?

RQ2: What are the benefits of online learning in a writing course during COVID-19?

RQ3: What are the students’ preferences and recommendations for improvement?

Participants were undergraduate students enrolled in an introductory, multimodal composition course at a large, Midwestern university in the U.S. This course is mandatory for most undergraduate students at the university and is considered sophomore-level (year two). Students from seven sections of this course were selected to participate in the present study via convenience sampling, as the researchers were teaching these sections at the time of the shift to ERT. The curriculum and class schedule of all sections were guided by Canvas modules created by the course coordinators, meaning that all seven sections were almost identical in course structure and design, with only minor differences when instructors chose to modify small assignments. Each section had approximately the same number of students (n = 20–24). This course served as an interesting example of a class that originally met in person but had to quickly transition to emergency remote teaching utilizing asynchronous communication after the ninth week of the Spring 2020 semester.

While most participants were native English speakers, a few were international students with first languages including Spanish, French, Italian, Chinese, and Swahili. Participants’ gender and age information was collected to be reported in aggregate following an established convention in linguistics research. A discussion board post was completed by 104 students during the first week of online instruction, and a Qualtrics survey was completed during the semester’s final week. The discussion board prompt can be seen in Figure 1. Although biodata were not available for participants who only completed the discussion board post, the average age of the 29 (16 male, 13 female) participants who completed the Qualtrics survey was 20 years old, and these data are believed to be representative of the larger group of participants as well due to the course’s nature as a mandatory sophomore-level class. Of the 29 students who completed the Qualtrics survey, 34% (n = 10) responded that they had taken an online course before, and 55% (n = 16) responded that they had not (three participants did not answer this question). Discussion board posts were anonymized prior to data analysis. The Qualtrics data were collected anonymously. This study was reviewed and considered exempt by the university’s institutional review board.

This study used a qualitative method for data collection and analysis. Two forms of data collection were designed to achieve this study’s goals.

First, participants responded to an online discussion board at the beginning of the online instruction period. This discussion board was designed to gauge student concerns and provide an opportunity for instructors to answer students’ questions about online coursework at the beginning of the emergency remote teaching period. Two prompts were included in these discussion board posts: (1) What questions or concerns do you have about online learning? and (2) What do you anticipate will be your biggest challenge for completing the coursework? It should be noted that this method of data collection was utilized in six of the seven sections; one instructor chose to omit this from their class curriculum.

Second, participants from all seven sections responded to a Qualtrics survey consisting of questions designed in an anonymous survey format to elicit honest responses about areas in which the course and instructors could improve. The Qualtrics survey was prepared by the authors and validated through a feedback loop among the authors and peer reviewers (graduate students in applied linguistics). The survey was sent to participants through an announcement on the course’s learning management system. This announcement explained the general purpose of the study and informed participants that participation was voluntary and answers would be anonymous. The survey was split into three sections for participants’ convenience. The first five questions comprised the first section and were created to gather the participants’ biodata, first languages, instructor, and experience with online coursework. The second section consisted of five open-ended questions designed to elicit answers to the research questions. The final section consisted of 10 Likert-scale questions to elicit participants’ attitudes about the emergency remote teaching period. The participants were given the choice to select from five options (strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree), as well as to explain their answers after their Likert-scale responses. The full Qualtrics survey can be found in Supplementary Appendix A.

Informed by the CoI model (Garrison et al., 1999), responses to open-ended questions in the discussion board and Qualtrics responses were manually coded by the four researchers using an open and axial coding process (Berg, 2004). During an initial round of open coding, all four researchers independently coded a small sample (20%) using the CoI model to establish a general understanding of the existing CoI themes and to check for inter-coder reliability. After the open coding process, the researchers met remotely and discussed the disagreements in coding until an agreement was reached. The researchers then completed axial coding to develop a coding guide consisting of themes, sub-themes, and examples. Certain examples did not fit in any of the existing categories on the CoI, so a fourth category was developed for technological responses labeled “Other.” After the categories and expectations were clear, to ensure the reliability of the researchers’ manual coding, all open-ended Qualtrics questions were coded independently by two of the researchers. Inter-annotator reliability was assessed using Krippendorff’s alpha (Krippendorff, 2007), yielding α = 0.858 (high reliability). For the discussion board responses, a random sample of 20% of the open-ended responses was annotated by a second researcher, yielding α = 0.865 (high reliability). Likert-scale results were analyzed utilizing simple descriptive statistics.

This section presents the findings pertaining to the three research questions. The first research question addressed the concerns students had and the challenges students faced regarding the transition to ERT. The second question addressed students’ perceived benefits after completing the ERT period. The final question addressed students’ preferences and recommendations for future writing classes during periods of ERT. Themes in student responses are sorted into the three main elements of the CoI framework (cognitive, social, and teaching) as identified through the data analysis process described above. Likert-scale responses from the Qualtrics survey are discussed alongside relevant thematic findings, and a summary of these responses can be found in Supplementary Appendix B.

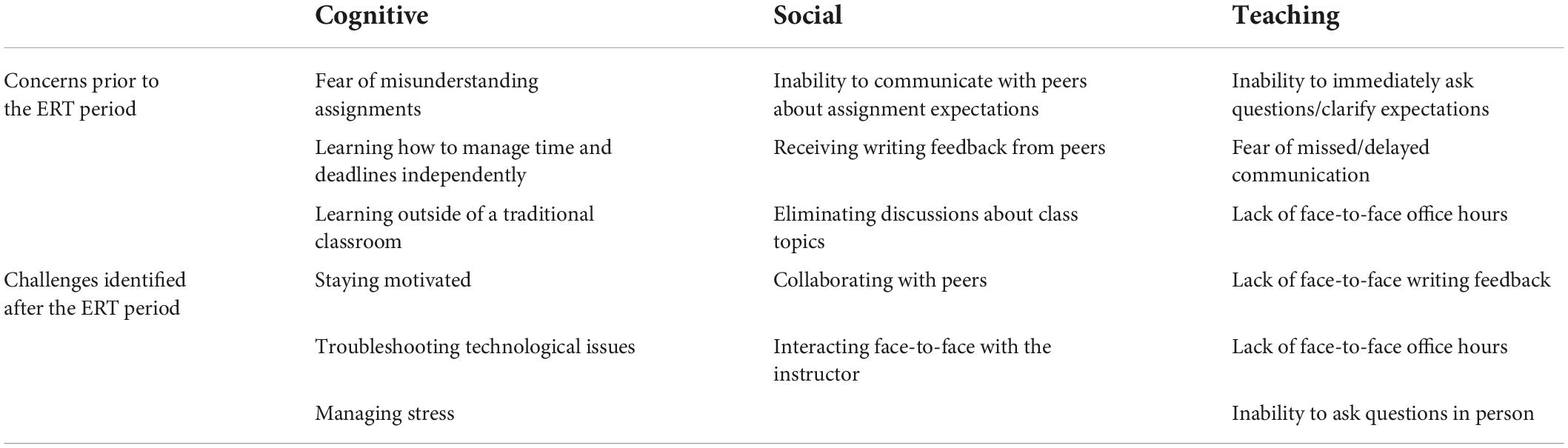

Table 1 presents an overview of the concerns identified by students in the discussion board posts prior to ERT and the challenges identified by students in the Qualtrics survey after the ERT period.

Table 1. Concerns and challenges identified by students prior to and during the emergency remote teaching (ERT) period.

As shown in Table 1, the discussion board themes emerging at the beginning of online instruction included being worried about understanding assignments, staying on top of assignments, and learning online instead of in the traditional classroom. One student expressed their cognitive concern when they said, “My biggest concern would be misunderstanding the directions of an assignment. I don’t want to do an assignment completely wrong because of a misunderstanding and then get points off for that reason only.” Another student stated their cognitive concern when they posted, “I have concerns about actually learning online, rather than from a [sic] in-person classroom.” Other students shared this sentiment about learning differently online than in person. This expresses a similar theme among many students’ posts.

When asked about cognitive challenges, an overwhelming amount of responses indicated that deadlines and keeping track of assignments would be challenging in the online environment, especially regarding time management. One student expressed these cognitive challenges when they said the following:

“I’m concerned for the time management involved with online classes (i.e., the new assignments we have instead of doing them in class, trying to balance the various formats of all my classes, and making sure I pace myself correctly, etc.) and how that will impact writing essays.”

Another challenge seen repeatedly in the responses was the idea of staying motivated as the classes moved online and students moved from the campus environment to home. This can be seen in one student’s response: “I’ve got plenty of time, but finding the motivation when I’m stuck in here might be a problem.” These challenges were also indicated at the end of the course.

After the move online and completing the course, the students stressed the absence of motivation and problems with technology. Before the transition, students were worried about misunderstanding the assignments. The Qualtrics survey revealed that some of the students did experience confusion about expectations of them with the transition online. An overall cognitive concern in the Qualtrics survey included stress about the transition: 48% of the students agreed with the statement, “I was stressed about the transition to online coursework.” When the transition to online first started, the students were worried about time management and deadlines. When given the statement “I spent more time learning and working for this class online compared to in-person,” 40% of the students agreed with it.

At the beginning of online instruction, students were also concerned with the lack of a social aspect in an online class. This includes group work and communicating with their peers to better understand assignments and receive writing feedback. One student mentioned the following:

“I am concerned about getting help/asking questions about my work. What I liked about this class was the ability to ask questions and get help from peers in person. So I am concerned about the switch to online and how I will ask questions.”

Students were unsure how to communicate with their peers and have the same interactions as they did in class. This student exemplified this notion when saying the following:

“I think it will definitely be difficult to communicate with others in the class and have discussions about our topics as well as getting in-person feedback. Unfortunately, responses won’t be as in-depth.”

Students enjoyed group work and found it helpful, making them concerned that they might lack that aspect in the transition online. One student stated, “The peer/group work aspect of the class has always been helpful, so I am worried about how things will go when that isn’t an option.”

In the Qualtrics survey distributed after instruction ended, lack of social presence was mentioned by the students. When asked what was challenging about the course, one student mentioned a challenge was “Not having other student [sic] to collaborate with easily.” Along with interaction with fellow students, a few participants also discussed the lack of in-person interaction with the professors. In the challenges prompt, there were answers such as “Not having the opportunity to meet with professors in person” and “Not having a physical person to ask for help or being able to go to an ‘office hour.”’ These concerns tie into some of the teaching concerns that the students had regarding communication.

At the beginning of online instruction, an overwhelming concern was the clarity of the assignments and being able to understand what the instructor was looking for. Students were also concerned about the deadlines and large amounts of tasks. These two concerns were combined into one comment on the help forum when a student stated:

“I think my biggest challenge will be understanding the work and the expectations for our assignments. I am also worried about meeting all the deadlines and completing my work in time.”

Another student expressed concern about clarity when they wrote: “I am concerned about getting help with essays. Usually, we have examples in class and can ask questions then and there to clarify.” In other words, prior to receiving online instruction, this student was concerned that they would not be able to immediately ask questions to an instructor if they wanted to clarify something in the course content due to the course’s asynchronous structure. Similarly, some students were worried about communication with the teacher. This involved being unable to ask questions in class and being concerned about general communication with the instructor. One student mentioned:

“My biggest concern would be the communication aspect. I know [the teacher] is very diligent when answering emails to students, but sometimes an email can be skipped over by accident.”

These concerns carried on throughout their time in the online course and were also reported in the Qualtrics survey.

After instruction, students also indicated some challenges related to the teaching aspect of the course. These were mostly the same concerns as before instruction. Students mentioned “Not having the opportunity to meet with professors in person,” “Not being able to ask questions in person,” and “No [in-]person feedback on writing” as some challenges they faced. When given the statement “I was frustrated with the way my English 250 instructor handled the switch to online coursework,” 32% of the students agreed. Though there were many challenges and concerns from the students, there were also some benefits to online learning.

Table 2 presents an overview of students’ perceived cognitive, social, and teaching benefits of the ERT period.

Some students brought up the flexibility and possibility of rewatching videos as an important benefit of online learning. One student stated, “I liked the flexible schedule and freedom. I could rewatch videos if I missed something.” This flexibility is relevant for the students because rewatching videos shows how they are trying to resolve ambiguities in understanding. While in-person or synchronous teaching does not allow the student to listen to the lecture again, students pointed out that with the recorded videos, they had the opportunity to clarify missing information. Along the same lines, a few students stated that the quick transition to online learning forced them to be self-organized to keep up with coursework; as one student commented, “[My] time-management skills definitely are stronger.” The students did not have frequent in-person reminders from the instructors or communication with their classmates, so they needed to be responsible for their own time management and self-paced learning. A few of them pointed out that this has increased their ability to organize their time.

Other benefits included acquiring new computer skills: as one student stated, “It helped me learn many different things that are in computer [sic] such as studio recording.” It is important to note that 92% of the students stated they felt well equipped with the technology and internet access that facilitated their work. Many of the oral presentations had to be performed virtually, and due to the asynchronous nature of the course, the students had to learn screen recording tools to create their project presentations. A few students found this beneficial for the development of their cognitive skills. Finally, students discussed that removing some unnecessary work “helped with lack of motivation.” Therefore, perhaps keeping a minimal number of smaller assignments would provide less cognitive effort on behalf of the students, allowing them to focus on the major assignments.

Most participants (80%) expressed that their instructors helped them succeed in the transition to online coursework and that they felt well-prepared to complete the final writing assignment with the materials provided to them online. Interestingly, 32% reported frustration with how the course was handled, but their answers also indicated that instructional management was crucial for their success. Having clear and easy-to-follow expectations on a weekly basis was one of the things students appreciated the most. As one student stated, “[The instructor] made the transition very easy by clearly telling us her expectations week after week and made sure we knew when things were due.” The instructors sent out weekly announcements summarizing the main points and deadlines for the following week. According to the students’ comments, this was one of the biggest strengths and benefits of these online courses.

Another important benefit that emerged from the data was having a supportive instructor who is available for virtual communication and who provides feedback on the smaller assignments. It is no surprise that increased communication allows support and guidance for the students. For example, one student stated, “My teacher was fantastic with communication and answering questions.” Hence, students found the teacher’s (virtual) presence an important factor for success. Additionally, as some students stated, getting feedback from the instructor, whether spoken or written, is one of the most relevant ways to keep the students on the right track in remote learning. Interestingly, some students enjoyed the asynchronous teaching flexibility and independence. It appeared that the students enjoyed the schedule flexibility but also needed direct support from the instructor, either via quick email responses, virtual availability, or feedback to guide their work.

Even though social benefits were more difficult to observe during emergency situations like this, the students brought up a few advantages of this experience. For example, one student stated they were “less distracted from social life” which allowed them more time to focus on studying. Having almost no opportunities to socialize due to the lockdown in March and April amid COVID-19 may have forced some of them to stay at home and use their time to study. On another note, a few other students suggested having more time for themselves as another benefit of online learning. One student commented that they had been able to sleep in, and another stated that they were able to enjoy “mindless self-indulgence.” Many courses transferred to an asynchronous format which likely allowed the students to have more flexible schedules.

Table 3 presents a summary of students’ preferences and recommendations for future ERT situations upon the completion of the course.

Interestingly, all of the responses regarding preferences and recommendations that referred to students’ cognitive capabilities expressed that the online portion of the course was reasonable and effective. For example, one student expressed the following: “Honestly, despite the technical difficulties, online learning is really effective for me, and I wouldn’t change anything.” This response demonstrates that the student successfully integrated their online learning experience with their cognitive abilities.

Similarly, another student who expressed no desire for changes to the online course structure explained that the online course allowed them greater flexibility in the ways they completed coursework: “[Online coursework] allowed me to listen to videos more than once and pause videos, as well as be able to do work whenever it fits into my schedule.” As in the previous example, this student successfully connected ideas and created solutions, an indicator of the sub-category “integration” in their cognitive presence.

One of the main social recommendations was to incorporate synchronous video sessions to allow for more personal interactions between the instructor and the students. Some students expressed feeling a lack of communication with the purely asynchronous online format, so this recommendation stemmed from their desire to incorporate a more social form of communication into the course. One student specifically recommended “having online meetings for occasional class discussions,” indicating that they desired a class-wide, interactive discussion rather than simply watching the instructor in asynchronous video format.

Other students felt that their social needs were well addressed by how their professors communicated with them during the period of emergency remote teaching. For example, one student stated the following:

“My professor’s availability online was outstanding, Bravo Zulu.1 Any concerns I had were met with understanding and worked through to help me keep going. Without the ability to communicate with my professor I may have completely withdrawn from attendance.”

In this case, this student’s preference for online instruction included frequent online meetings and emails which catered to their social needs. In their view, the social interaction with the instructor kept them from withdrawing from the course.

Finally, some students expressed a desire for additional peer-review sessions with their classmates. Whereas each instructor set up peer-review sessions differently when classes were in-person, they all used a built-in peer-review tool in Canvas during the period of emergency remote teaching. Unlike in-class peer-review sessions, this tool did not allow for much social interaction between the reviewer and the reviewee. The reviewer merely left comments on the reviewee’s draft, and there was not an opportunity for students to discuss recommendations or changes to be made as they did in person. Therefore, the call for more peer-review sessions likely stemmed from students’ desires to collaborate with each other as they had been doing throughout the semester in person.

In addition to the social aspect, the majority of students’ recommendations for teaching involved ideas about the course’s instructional management. Providing an opportunity for weekly synchronous video sessions was discussed above as a social recommendation, but it also falls into the category of teaching and instructional management since teachers must coordinate these synchronous sessions and integrate them into the instruction of the course. In fact, 44% of the students in the Qualtrics survey expressed that they would learn better if the class had real-time lectures instead of recorded videos. One student phrased this recommendation as follows: “Offer an online ‘in-class’ option, i.e., a Zoom call or similar software that can be used to simulate a real classroom that is optional or is recorded for students to watch.” In this response, the student expressed a desire for a “real classroom” experience that could be made possible with a synchronous video session, but they also recommended recording these sessions and making them optional. Recording video sessions for students to watch later (i.e., asynchronously) is one way to continue the benefits of asynchronous teaching (expressed in RQ2 above) while also ensuring that all coursework is accessible for students: Those who do not have a reliable internet connection at home or those who must take on additional responsibilities due to the pandemic may not be able to attend the synchronous session, but a recording allows them to view what they missed during that time.

When this course moved online for ERT, the instructors had to quickly reimagine the in-class activities that they had planned. Many of these activities were restructured as low-point assignments or discussion board posts on Canvas. A few student recommendations referred to these low-point assignments as “busy work,” and many responses called for a reduced number of these assignments. For example, one student called for “less mandatory discussion questions/drafts, [and] fewer assignments but more demanding ones.” For this student, the online discussion forums were not necessarily cognitively demanding, but they may have overwhelmed them simply by the increased number of assignments on their to-do list. Therefore, the recommendation that emerged from these responses was to reduce the number of low-point assignments that replaced in-class activities while putting more emphasis on high-point major assignments.

This section presents a discussion of the findings along with suggestions offered that can be used to guide the design of composition courses and pedagogical practices during situations of emergency. College composition courses are historically significant at US universities as the most-required course in higher education (Crowley and Hawhee, 1999). Although Crank (2012) asserts that it is a challenge to help freshmen with improving their writing skills, over the course of students’ college life, their writing skills are believed to be improved through the writing courses that they take (Oppenheimer et al., 2017). However, it is important to note that writing proficiency has been found to be context-bound and dependent on general writing skills (Oppenheimer et al., 2017). In this study, the recommendations provided will be context-specific, focusing on the emergency remote teaching situation so that future courses are better informed about what measures to take when designing a writing course during another emergency situation.

The present study examined students in a required university composition class who were forced to quickly move online for a period of ERT. The students in this study listed misunderstanding of the instructions, difficulty keeping track of deadlines, a lack of motivation, and technological challenges as the leading cognitive concerns. Online learning entails more autonomy on the part of the student since there is no physical space to attend to and no instructor to report to face-to-face. Therefore, it is up to the student to take charge of their learning, follow the syllabus, and find ways to solve learning problems resulting from the lack of traditional, face-to-face education. Similar to the students in this study, the students in Borkotoky and Borah’s (2021) study suffered from similar cognitive challenges, where they experienced a lack of motivation and concentration and fatigue from the online classes during the ERT period. The students also reported difficulties accessing the internet to complete their assignments. One cognitive challenge the students did not report experiencing in this study is boredom from online learning, which was expressed by the students in Almansour and Al-Ahdal’s (2020) study. The findings revealed that this boredom resulted from a lack of classroom interaction, which is typical of in-person learning. Several other studies also reported student boredom during ERT (e.g., Irawan et al., 2020; Derakhshan et al., 2021). This cognitive challenge might stem from a long-standing tradition of in-person education the students were familiar with prior to the ERT period. However, it might also be related to the other factors that need further exploration. Consequently, the fact that the students in this study did not raise boredom as a concern or a challenge for their online writing course is an important finding that emerged implicitly from the research.

Some additional aspects of the COVID-19 ERT period align with previous findings from online learning research. Students in this course reported being concerned about the social aspect of the in-person course and discussed that they needed a “physical person” to talk to, similar to Tichavsky et al. (2015). They also expressed the need for synchronous video sessions, indicating the need for teaching presence to facilitate cognitive presence, or as Garrison et al. (2010) suggest, “to encourage active discourse and knowledge construction” (p. 93). Moreover, one particularly important type of skill acquisition that occurred during the emergency remote teaching period was related to technological literacy. Bourelle et al. (2017) assert that to promote multimodal literacy, online writing classes should teach technology and incorporate multimodal assignments and appropriate scaffolding tools. In this study, 92% of students expressed that they felt well equipped to succeed in the course with the technology they had access to at the beginning of the online period, yet several students expressed that a major benefit of the online period was being able to hone their computer skills even more (e.g., learning how to use Canvas studio recording tools for asynchronous presentations).

On the other hand, certain aspects were unique to the emergency period. Students who signed up for an in-person class were forced to quickly transition to an online learning course. According to Garrison et al. (2010), “high levels of social presence with accompanying high degrees of commitment and participation are necessary for the development of higher-order thinking skills and collaborative work” (p. 94). Thus, it is important to note that for the students in this study, the degree of commitment might have differed from that of a regular, online environment where the students chose to receive online education. The lockdown, the fear of virus transmission, and financial insecurity might have caused stress and discomfort for some students. On the other hand, bearing in mind that students’ lives tend to be busy with studying and socializing, it appeared that some students enjoyed their “time off” when they could stay and work from the comfort of their homes. In terms of course design, to facilitate the cognitive load, the weekly announcements and clearly stated deadlines were considered a major strength of the course showing the need for a structured, simple, and easy-to-follow approach. Finally, by the end of the semester, a majority of the participants expressed that their instructors helped them succeed with online coursework. This demonstrates the relationship between students’ cognitive concerns and teachers’ roles in alleviating undue stress.

Amid all the challenges and unexpected benefits of this emergency remote teaching period, recommendations that may be informative for creating a positive, learner-centered online teaching environment were developed. These recommendations are based on the findings of this study, and they address the overlapping components of the CoI framework by prioritizing setting climate, supporting discourse, and selecting content to improve students’ experiences with ERT (Garrison et al., 1999). Below these recommendations for facilitating a learner-centered approach to teaching during emergency periods are summarized.

1. The first recommendation is that instructors incorporate optional synchronous video sessions to allow for a more personal interaction (assisting with students’ social needs) between the instructor and the students, along with uploading a recording of these sessions to the class’s learning management system to ensure accessibility for the entire class.

2. The next recommendation is to increase communication channels with students, including frequently communicating structured, clear, and easy-to-follow expectations. Whereas some students will get by with a weekly email update of class requirements, it was found that others will rely on open video conferencing hours (for instance, on Zoom, Microsoft Teams, or other video conferencing systems) where they can both express themselves and work through their struggles with their instructor.

3. Furthermore, instructors are encouraged to provide opportunities for student collaboration. During periods of ERT, some students may live alone with very little social interaction. Class activities—such as collaborative peer review sessions, synchronous work time on Google Docs, or websites such as Perusall (Kohnke and Har, 2022)—can serve as an opportunity to facilitate students’ social needs while also improving their learning experience. This recommendation also addresses students’ expressed concern about receiving less writing feedback from their peers and instructor during the ERT period.

4. The final recommendation is for teachers to reduce unnecessary tasks for students whenever possible. While it may seem like a good idea to provide a variety of low-stakes assignments and activities for students to complete in lieu of in-person class time, these extra assignments may be an overwhelming burden for students who are still figuring out how to manage their lives during an emergency situation. Focus on designing major assignments around the most important learning outcomes of the course instead, and encourage students’ development of time management skills by sticking to a reliable schedule for posting this important course content.

These recommendations come together to address all aspects of the CoI framework by acknowledging social, cognitive, and teaching components of managing a virtual classroom environment. It is believed that these recommendations will improve students’ and teachers’ educational experiences with online writing courses during emergency periods.

“Writing may be by far the single academic skill most closely associated with college success” (Conley, 2007, p. 5) due to its cross-disciplinary importance in college courses. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to maintain the quality of writing courses even during unprecedented times to support the college students not only during their time in college but also after graduation when they are looking for employment. The aim of the present study was to explore students’ perceptions in a university writing course during an emergency period and propose guidance on designing a learner-centered online education environment for emergency situations. This study investigated students’ perceptions of ERT during the period of lockdown due to COVID-19 in 2020. Students shared their concerns, challenges, and perceived benefits and preferences regarding ERT in this university writing course. The CoI framework provided an overview of all these components through cognitive, social, and teaching presence lenses.

A few limitations were present in this study. First, the scope of this study was limited due to the unexpected nature of the emergency remote teaching period. Only four instructors (seven sections) in one university department were included in this study, limiting the generalizability of these results. Future studies should draw from a larger pool of students and classes to produce more generalizable results. Additionally, because this study relied on discussion board posts and survey responses, students’ responses were brief and may not reflect the full depth of their perspectives. Future research should engage students in semi-structured interviews to capture their perceptions of ERT more fully and contribute to the design of learner-centered online classrooms.

Despite its limitations, this study presented a way to explore students’ perceptions of ERT through the lenses of the CoI framework. Results showed that while students encountered challenges, such as lack of motivation and feeling a social disconnect, they also found a few benefits, such as increased schedule flexibility, and improved time-management skills. This study presented recommendations that can be used as a guide for facilitating online teaching, especially in university writing courses, during emergency periods.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB), Iowa State University. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

AG led the conception of this study. All authors contributed equally to designing the study, coding portions of the data, writing the first draft of the manuscript, contributed to manuscript revision, and read and approved the submitted version.

The open access publication fees for this article were covered by the Iowa State University Library.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.965659/full#supplementary-material

Ahmed, S. A., and Dakhiel, M. A. (2019). Effectiveness of learner-centered teaching in modifying attitude towards EFL and developing academic self-motivation among the 12th grade students. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12, 139–148. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n4p139

Akyol, Z., and Garrison, D. R. (2008). The development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: Understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. J. Asynchr. Learn. Netw. 12, 3–22. doi: 10.24059/olj.v12i3.66

Almansour, M. I., and Al-Ahdal, A. A. M. H. (2020). University education in KSA in COVID times: Status, challenges and prospects. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Change 14, 971–984.

Badjadi, N. E. I. (2020). Learner-Centered English Language Teaching: Premises, Practices, and Prospects. IAFOR J. Educ. 8, 7–27. doi: 10.22492/ije.8.1.01

Bai, X., and González, O. R. G. (2019). A comparative study of teachers’ and students’ beliefs towards teacher-centered and learner-centered approaches in grade 12 English as a foreign language class at one governmental senior secondary school in Shaan’xi Province, China. Scholar 11, 37–44.

Barbour, M. K., LaBonte, R., Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., et al. (2020). Understanding pandemic pedagogy: Differences between emergency remote, remote, and online teaching. State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada. Halfmoon Bay, BC: Canadian eLearning Network.

Bamidele, A. (2021). “Student-Centered Interactions within an ESL Classroom using Online Breakout Room,” in Proceedings of the AUBH E-Learning Conference 2021: Innovative Learning & Teaching - Lessons from COVID-19, (Pearson). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3878774

Borkotoky, D. K., and Borah, G. (2021). The impact of online education on the university students of Assam in COVID times. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 14, 1028–1035.

Bourelle, T., Clark-Oates, A., and Bourelle, A. (2017). Designing online writing classes to promote multimodal literacies: five practices for course design. Commun. Design Q. 5, 80–88. doi: 10.1145/3090152.3090159

Bozkurt, A., and Sharma, R. C. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. Asian J. Dist. Educ. 15, 1,i–vi.

Conley, D. T. (2007). Redefining college readiness. New York: Educational Policy Improvement Center.

Crank, V. (2012). From high school to college: Developing writing skills in the disciplines. WAC J. 23, 49–63.

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., and Glowatz, M. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. J. Appl. Teach. Learn. 3:1. doi: 10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

Crowley, S., and Hawhee, D. (1999). Ancient rhetorics for contemporary students. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2–19.

Daymont, T., Blau, G., and Campbell, D. (2011). Deciding between traditional and online formats: Exploring the role of learning advantages, flexibility, and compensatory adaptation. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 12, 156–175.

Delaney, J., Johnson, A. N., Johnson, T. D., and Treslan, D. L. (2010). “Students’ perceptions of effective teaching in higher education,” in 26th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning, (University of Wisconsin).

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, M., Mehdizadeh, M., and Pawlak, M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: sources and solutions. System 101:102556. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102556

Diebel, P. L., and Gow, L. R. (2009). A comparative study of traditional instruction and distance education formats: student characteristics and preferences. NACTA J. 53, 8–14.

Garrison, D. R. (2006). Online collaboration principles. J. Asynchr. Learn. Netw. 10, 25–34. doi: 10.24059/olj.v10i1.1768

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. J. Asynchr. Learn. Netw. 11, 61–72.

Garrison, D. R. ed (2009). “Communities of inquiry in online learning,” in Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, Second Edition, (IGI Global), 352–355. doi: 10.4018/978-1-60566-198-8.ch052

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Int. Higher Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., and Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. Int. High. Educ. 13, 31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.002

Gonçalves, E., and Capucha, L. (2020). Student-centered and ICT-enabled learning models in veterinarian programs: What changed with COVID-19? Educ. Sci. 10, 1–17.

Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., and Bond, M. A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Available online at: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning [accessed on 20 Jul, 2022]

Hunzer, K. M. (ed.) (2014). Collaborative learning and writing: Essays on using small groups in teaching English and composition. Delhi: McFarland.

Irawan, A. W., Dwisona, D., and Lestari, M. (2020). Psychological impacts of students on online learning during the pandemic COVID-19. KONSELI 7, 53–60.

Ismailov, M., and Ono, Y. (2021). Assignment design and its effects on Japanese college freshmen’s motivation in L2 emergency online courses: a qualitative study. Asia Pacif. Educ. Res. 30, 263–278.

Jensen, E. B. (2016). Peer-review writing workshops in college courses: Students’ perspectives about online and classroom based workshops. Soc. Sci. 5:72. doi: 10.3390/socsci5040072

Johnson, S. D., Aragon, S. R., and Shaik, N. (2000). Comparative analysis of learner satisfaction and learning outcomes in online and face-to-face learning environments. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 11, 29–49.

Johnson, N., Veletsianos, G., and Seaman, J. (2020). U.S. faculty and administrators’ experiences and approaches in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online Learn. 24, 6–21. doi: 10.24059/olj.v24i2.2285

Kassim, H., and Ali, F. (2010). English communicative events and skills needed at the workplace: Feedback from the industry. Engl. Specif. Purposes 29, 168–182. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Kaur, I., and Joordens, S. (2021). The factors that make an online learning experience powerful: Their roles and the relationships amongst them. Int. J. E Learn. 20, 271–293.

Kohnke, L., and Har, F. (2022). Perusall Encourages Critical Engagement with Reading Texts. RELC J. 2022:00336882221112166.

Lowenthal, P., Bauer, C., and Chen, K. Z. (2015). Student perceptions of online learning: An analysis of online course evaluations. Am. J. Dis. Educ. 29, 85–97. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2015.1023621

Mehlenbacher, B., Miller, C. R., Covington, D., and Larsen, J. S. (2000). Active and interactive learning online: A comparison of Web-based and conventional writing classes. IEEE Transac. Prof. Commun. 43, 166–184. doi: 10.1109/47.843644

Moore, J. L., Dickson-Deane, C., and Galyen, K. (2011). e-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? Int. High. Educ. 14, 129–135.

Morris, T. A. (2010). Exploring community college student perceptions of online learning. United States: Northcentral University.

National Center for Education Statistics [NCES] (2011). Learning at a Distance: Undergraduate Enrollment in Distance Education Courses and Degree Programs. Washingdon, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

National Center for Education Statistics [NCES]. (2020). The Condition of Education 2020. Washingdon, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2017). Bravo Zulu. Available online at: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/t/terminology-and-nomenclature/bravo-zulu.html [accessed on 25, Jul, 2022]

Oppenheimer, D., Zaromb, F., Pomerantz, J. R., Williams, J. C., and Park, Y. S. (2017). Improvement of writing skills during college: A multi-year cross-sectional and longitudinal study of undergraduate writing performance. Assess. Writ. 32, 12–27.

Pandey, M., and Pandey, P. (2014). Better English for better employment opportunities. Int. J. Multidiscip. Appr. Stud. 1, 93–100.

Patthey-Chavez, G. G., and Ferris, D. R. (1997). Writing conferences and the weaving of multi-voiced texts in college composition. Res. Teach. Engl. 31, 51–90.

Phipps, R., and Merisotis, J. (1999). What’s the Difference? A review of contemporary research on the effectiveness of distance learning in higher education. Washington, DC: Institute for Higher Education Policy.

Ritthipruek, J. (2018). “All on screen: The effects of digitized learning activities on increasing learner interest and engagement in EFL classroom,” in Proceedings of The Asian Conference on Education. (Washingdon, DC: National Center for Education Statistics).

Sarikaya, İ (2021). Teaching writing in emergency distance education: the case of primary school teachers: Teaching writing in emergency distance education. Int. J. Curricul. Instruct. 13, 1923–1945.

Shim, T. E., and Lee, S. Y. (2020). College students’ experience of emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 119:105578.

Tichavsky, L. P., Hunt, A. N., Driscoll, A., and Jicha, K. (2015). “It’s just nice having a real teacher”: Student perceptions of online versus face-to-face instruction. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 9:2. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2015.090202

Trust, T., and Whalen, J. (2020). Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 28, 189–199.

Van Viegen, S., and Russell, B. (2019). More than language—Evaluating a Canadian university EAP bridging program. TESL Canad. J. 36, 97–120. doi: 10.18806/tesl.v36i1.1304

Villacís, W. G. V., and Camacho, C. S. H. (2017). Learner-centered instruction: An approach to develop the speaking skill in English. Rev. Publ. 12, 379–389.

Weldy, T., Maes, J., and Harris, J. (2014). Process and practice: Improving writing ability, confidence in writing, and awareness of writing skills’ importance. J. Innov. Educ. Strateg. 3, 12–26. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12762

West, R. E., Sansom, R., Nielson, J., Wright, G., Turley, R. S., Jensen, J., et al. (2021). Ideas for supporting student-centered stem learning through remote labs: a response. Educ. Technol. Res. Devel. 69, 263–268. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09905-y

Wikle, J. S., and West, R. E. (2019). An analysis of discussion forum participation and student learning outcomes. Int. J. E Learn. 18, 205–228.

Williamson, B., Eynon, R., and Potter, J. (2020). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learn. Med. Technol. 45, 107–114. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2020.1761641

Keywords: emergency remote teaching, education during COVID-19, student perspectives, Community of Inquiry (COI), learner-centered online education

Citation: Guskaroska A, Dux Speltz E, Zawadzki Z and Kurt Ş (2022) Students’ perceptions of emergency remote teaching in a writing course during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 7:965659. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.965659

Received: 10 June 2022; Accepted: 05 September 2022;

Published: 28 September 2022.

Edited by:

Lucas Kohnke, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Eric Ho, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Guskaroska, Dux Speltz, Zawadzki and Kurt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zoë Zawadzki, emF3YWR6a2lAaWFzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.