- School of Educational Sciences, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

School- and teacher-related contextual factors are those that often influence the quality of social-emotional learning (SEL) program implementation, which in turn has an impact on student outcomes. The current paper was interested in (1) Which teacher- and school-related contextual factors have been operationalized in articles that focus on the relationship between implementation quality indicators 200 and contextual factors in SEL program implementation in schools? (2) Which contextual factors would demonstrate the highest frequency of statistically significant relationships with SEL program implementation quality indicators and could therefore be more essential for ensuring the program outcomes? Determining the more significant contextual factors would allow for more focused and better-informed teacher professional development for supporting students’ social and emotional skills, it can also be useful for hypothesis development for quasi- experimental research designs of SEL program implementation on the school level. A systematic literature search was conducted in seven electronic databases and resulted in an initial sample of 1,281 records and additional journal and citation sampling of 19 additional records. 20 articles met the final inclusion criteria for the study (19 quantitative and one mixed methods). Inductive content analysis and quantitative analysis were employed to map the variables and estimate the relative frequency of statistically significant relationships across studies. Four categories of contextual factors were revealed: program support, school, teacher, and student categories. The results of the study reveal the diversity in contextual factors studied across SEL program implantation quality and bolster the relevance of program support factors (modeling activities during coaching and teacher–coach working relationship) for ensuring implementation quality. A link between teacher burnout and program dosage was revealed. Student factors emerged as a separate contextual level in school, with special attention to student baseline self-regulation that may influence SEL program implementation quality.

1. Introduction

The purpose of general education, in addition to cultivating learners’ cognitive and academic skills, is to facilitate social change, and therefore, children’s social, emotional, and character development has become increasingly more emphasized and intertwined with compulsory education (Jones and Bouffard, 2012; Kochenderfer-Ladd and Ladd, 2016; Elias, 2019). Social and emotional learning (SEL) refers to the process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions (Weissberg et al., 2015). SEL serves as an interdisciplinary field that aligns areas for educators, researchers, and policymakers that address students’ capacities to coordinate cognition, affect, and behavior, as well as navigate daily challenges and succeed in life, career, and college (Osher et al., 2016). International policymakers have emphasized the importance of social and emotional skill development to assure students’ readiness as future citizens in a world characterized by more turbulence and uncertainty (OECD, 2021a,b).

Studies, where peer and teacher report measures have been used, indicate that children, when starting school, may not demonstrate the basic skills needed for effective collaboration, emotional, and behavioral control, and could be at risk of educational failure (Rabiner et al., 2016; Suntheimer and Wolf, 2020). The risk factors include lower socio-economic background, being younger or male (Zakszeski et al., 2020), having weaker executive functioning skills (Suntheimer and Wolf, 2020), or prior experiences of peer rejection (Ladd, 2006). Furthermore, there is evidence that if not offered assistance, problematic behavior tends to cumulate toward more aggression in adolescence (Appleyard et al., 2005), which can in turn impact other learners through negative peer influence and stress contagion, and lead to distress in the learning environment (Burgess et al., 2018). Social emotional skill support, however, can be highly beneficial to those at risk of externalizing problems (Jones et al., 2011; Calhoun et al., 2020; Streimann et al., 2020).

Coherent with the findings that social-emotional (SE) and intellectual development are intertwined (Cantor et al., 2019), the integration of evidence-based programs to support SE skill development (e.g., SEL interventions) within the academic curriculum has been shown to contribute toward both: decreasing problematic behaviors, such as disruptions or aggressive behavior in the classroom; and enhancing students’ academic achievement (Durlak et al., 2011; Oberle et al., 2014; Corcoran et al., 2017). SEL interventions can therefore be quite crucial in preventing educational segregation or developmental disadvantage in today’s educational context. Sustainably coordinated efforts on the school level that promote a safe and cooperative environment and support the practice of SEL competences in everyday situations benefit all children and make schools optimal contexts for SE learning (SEL) (Zins et al., 2004; Jones and Bouffard, 2012).

Earlier research shows that the success of an SEL program, specifically the impact it has on student outcomes, is dependent on its implementation process (Durlak and DuPre, 2008; Cook et al., 2018; Humphrey et al., 2018), the quality of which is affected by different contextual factors, such as positive work climate or teacher predisposition (Kam et al., 2003; Durlak and DuPre, 2008). In other words, the implementation of a school-based SEL program is a process that is situated in the school context, which in turn influences the program outcomes students may obtain, through supporting or hindering that process. Therefore, looking at the qualities of the implementation process has been emphasized as a crucial research area (Durlak and DuPre, 2008; Durlak, 2015), as this makes the benefits of the programs available to students.

Despite copious research published during the past few years on SEL program implementation, there is no consensus on which contextual factors are most essential, or to which areas the highest degree of effort should be directed, in order to ensure the most supportive quality context for SEL program implementation in the school. Although related reviews have been done before (e.g., Dusenbury et al., 2003; Durlak and DuPre, 2008), to the best knowledge of the authors, none have solely concentrated on programs that support SE skills at school. The current article employs a systematic literature review process to synthesize school-based research on SEL program implementation that specifically looks at interactions between SEL program implementation quality indicators and teacher- and school-related contextual factors. The aim of the current literature review is to map the diversity in school-based contextual factors that have been explored in relation to SEL program implementation quality and to clarify, which of them may have proven more consistently significant for implementation quality in schools. The analysis was guided by the following research questions:

(1) Which teacher- and school-related contextual factors have been operationalized in articles that focus on the relationship between implementation quality indicators and contextual factors in SEL program implementation in schools?

(2) Which contextual factors demonstrate the highest frequency of statistically significant relationships with SEL program implementation quality indicators and could therefore be more essential for ensuring the program outcomes?

In the next section, we first offer a brief overview of how the quality of SEL program implementation has been defined in previous research and shortly discuss the complexities in defining implementation quality. Afterward, we will give an overview of the systematic literature review process and data analysis. In the last paragraph of the article, we discuss the main findings and present possible future research avenues.

2. Conceptualizing the quality of SEL program implementation and its context

Domitrovich et al. (2008) have defined implementation quality as “the discrepancy between what is planned and what is actually delivered”; measures of implementation therefore also indicate high or low implementation quality in the school context (Dusenbury et al., 2003). Osher et al. (2016) also indicated that procedural fidelity to the original program design and core features is mostly reported as synonymous with implementation quality. Different aspects of the implementation process have been differentiated (Dane and Schneider, 1998; Berkel et al., 2011; Durlak, 2016), and those have been sometimes described similarly but named somewhat differently or vice versa—similar labels may have been used for different levels of the construct. For example, in implementation science “fidelity” is used as an umbrella term for implementation quality, and “adherence” is used to indicate a measure of delivering program components (e.g., Century et al., 2010; Proctor et al., 2011), whereas in other areas, such as SEL program implementation, for example, fidelity is used synonymously with adherence (Durlak, 2016). This notion is known as the “jingle-jangle fallacy” (Jones et al., 2019)—the lack of clarity in the program implementation vocabulary is an issue often pointed out in this context (Dane and Schneider, 1998; Century et al., 2010; Proctor et al., 2011; Cook et al., 2019). Of the aspects distinguished in implementation research, the critical ones (Dane and Schneider, 1998; Century et al., 2010) are:

(1) adherence/fidelity—the degree to which the major components of the program have been faithfully delivered

(2) exposure/dosage—the amount of program delivered

(3) quality of delivery—the qualitative aspects of program delivery: how well or in which manner the program is carried out; and

(4) participant responsiveness—the manner in which the program engages its participants (Dane and Schneider, 1998; Durlak, 2016).

Berkel et al. (2011) and Durlak (2016) also point to adaptation as an outcome measure of program implementation; the authors of this article, however, have not come across this quality indicator in SEL studies that look at implementation as an outcome. The implementation aspects most commonly studied in SEL program implementation are adherence/fidelity and exposure/dosage1 (Durlak, 2016). In the current article, the implementation quality is treated synonymously with the four implementation process indicators listed above, as those are commonly reported in SEL program research that treats implementation as an outcome.

In addition to seeing program implementation quality as equivalent to its process characteristics, several accounts suggest the contextual dimension as a constituent part of implementation quality (Osher et al., 2016). Some conceptual models have been introduced to systematize variables that influence the implementation of SEL interventions. Durlak and DuPre (2008), for example, based their model on an extensive literature review and interactive systems framework (ISF) approach and compiled a list of 23 contextual variables on 5 levels of implementation (community; provider e.g., teacher; organizational capacity; prevention support system (such as training and coaching); and the program itself with its fit to the implementation context). The most comprehensive level in this model is the organizational context—which is divided into three subcategories: general factors, specific practices, and staffing considerations. Domitrovich et al. (2008), on the other hand, have suggested a three-level ecological framework for high-quality implementation of programs in schools that places implementation quality in the nested ecosystem of individual, school, and macro-level factors. The individual level holds teacher psychological and professional characteristics and attitudes, the school level holds both the organizational climate and culture, as well as the classroom climate; and the macrosystem refers to policies and partnerships on a larger scale. In this model, coaching and training are seen as inherent to the program implementation process itself and not as a separate contextual layer. Durlak and DuPre (2008) posit that their framework might overlook some factors, and when compared to Domitrovich et al. (2008) they do not include any student-related factors. In comparison, Domitrovich et al. (2008) place classroom climate and school culture on the same level, despite evidence that classroom climate is a nested level in the school context that can vary considerably within one school (e.g., Marsh et al., 2012). In sum, both—aspects of the implementation process, and the contextual factors that support them—are part of understanding the quality of the implementation process, for creating the conditions where students reap the greatest benefit.

Looking at the two decades of SEL program implementation research from the perspective of contextual influences may allow for drawing more systematic conclusions over time. There is a growing body of research looking at the more focused pieces of the puzzle, concentrating, for example, on a few aspects of the school ecology and looking for statistically significant predictors of implementation quality indicators among contextual factors (for example, perceived school organizational health or teacher burnout; e.g., Ransford et al., 2009; Musci et al., 2019). The current article, thus, contributes to the theoretical development which attempts to illuminate the structure and dynamics of the contextual factors that can support or hinder quality SEL program implementation.

Determining the more significant contextual factors would also allow for more focused and better-informed teacher professional development for supporting students’ SE skills, both in terms of inservice and preservice training and support, as well as teacher coaching. It would allow for informed consultation by teachers and school personnel toward the more effective implementation of SEL programs. It can be additionally useful for hypothesis development for quasi-experimental research designs of SEL program implementation on the school level, to ascertain whether or not the more pronounced characteristics have indeed a more distinct role to play in SEL program implementation in practical life, enabling more supportive outcomes for students, and explain SEL program implementation process quality in more detail.

3. Methods

For this study, a systematic literature review process was conducted, to identify the significant relationships between SEL program implementation indicators and teacher- and school-related contextual factors within empirical journal articles that focus specifically on those relationships.

3.1. Procedure for searching, identifying, and selecting articles

The search process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement protocol (Moher et al., 2009). The EBSCOhost Web2 databases were used for the search, which is the search engine with the highest volume of meta-data (over 70,000 journals, which is higher than the Web of Science or Scopus). This database was selected to avoid duplication in the search procedure due to a short supply of allocated human resources. In the following sections, an overview of the search procedure and analysis is offered.

In the first step, a list of databases was included for the search: Academic Search Complete, APA PsycArticles, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), ERIC, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, MasterFILE Premier, MasterFILE Reference eBook Collection, MEDLINE, and Teacher Reference Center. For the purpose of retrieving the highest number of relevant research articles, the following criteria were set for the EBSCO search: (1) apply related words, (2) apply equivalent subjects, (3) peer reviewed, (4) published between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2021, and (5) English as publication language. Altogether 29 preliminary test searches were conducted prior to the final search on 28 April 28, 2021, in order to find the combination of search terms that would result in the highest concentration of relevant articles for the study. After several pilot searches with various topic-related search terms, resulting in either a too-narrow or a too-widespread result, it was decided to add the specific names of the recognized SEL programs (as reported by Jones et al., 2017) to the search, to find more relevant articles (counting on the parameters of related words and equivalent subjects to direct to all the relevant results). The final search strategy was carried out in the combination of the following search terms: SE OR socio-emotional OR social and emotional OR sel OR social competence OR character OR behavior OR behavior OR intervention AND teacher* OR school* AND implementation quality OR implementation variable*. The search term program was excluded during the test search phase for producing too wide a range of results in heavily dispersed topics from policymaking to engineering, and substituted with the search term intervention which is a frequent term used for SEL programs. The search term behavior was added as whole school positive behavior intervention support is sometimes considered relative to SEL (e.g., Elias, 2019), and its primary level or Tier 1 activities are hard to differentiate from SEL, as they focus on teaching all students the skills for self-regulation and social success (Walker et al., 1996). The final database search on 28 April 2021, resulted in 1,883 articles. After removing duplicates, 1,281 articles remained for abstract level screening (Figure 1).

3.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The included 1,281 articles were first screened on the title and abstract level. The inclusion criterion for first level screening was: the article was about SEL programs carried out in schools, in grades 1–12. Two independent researchers assessed 10% of the articles (n = 130) independently on the scale of yes/no/maybe, the interrater reliability, Cohen’s k was, 70 (substantial) across all labels and, 93 (excellent) between yes and no. The differences in agreements were discussed thoroughly, all occurring differences were discussed until unanimous consent was reached. Due to a high interrater agreement regarding yes/no, articles falling under both, yes and maybe were included in the second round of screening (Figure 1). The excluded articles were either not related to school or education; were about different educational topics (formative assessment, quality management); reported research about a different type of intervention (directed to specific educational needs, e.g., autism, learning disability, or mental health or toward other specific skills, reading, writing, physical activity, nutrition or sexual behavior); they were overall targeting a different age group (preschool or university) or different type of non-school-related SEL program (parenting). After the abstract and title-level screening, 76 articles were included for text level screening. Journal and reference sampling was carried out throughout May 2021 and additionally, in October 2022. As prevention science has been identified as the framework that drives the SEL field (Jones et al., 2019), all numbers of Prevention Science were screened. Similarly, all 2000–2022 issues of the Journal of School Psychology were screened. From the additional sampling types, 18 extra articles were found for screening (Figure 1).

In the second round of screening, the full texts of 94 articles were screened, 4 inclusion criteria were (1) the articles were about an evidence-based SEL approach that was applied in the school on the school level- or classroom level in grades 1–12; (2) the evidence-based SEL approach specifically included teaching SE skills to students; (3) the article was looking at the relation of some SEL program implementation indicator and some school or teacher related contextual variable, and directly aimed at determining the relationship between the two, and (4) the article reported empirical research. It must be noted that in different frameworks understandings of what an SEL program is may somewhat vary (Osher et al., 2016) and we, thus, specify what we see as the essential components of an SEL program. In the context of the current article, the SEL program is seen as a program that (a) teaches and actively practices SE skills (Zins et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2017) through (b) either kernel- or curriculum-oriented activities (Elias, 2019).

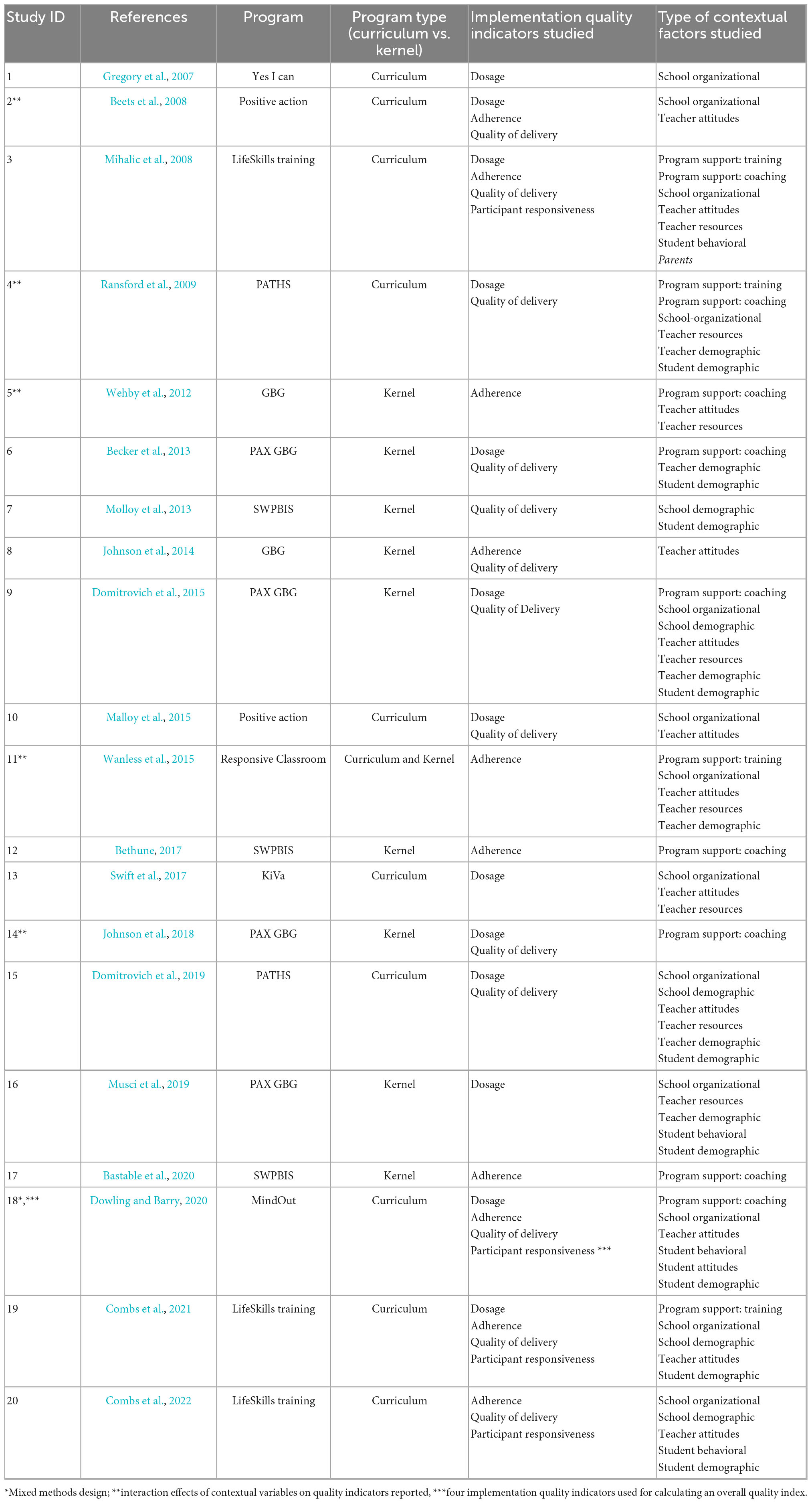

Again, two experts screened 30 full-text articles separately (with the percentages of disagreement ranging from 6.7 to 20 for the inclusion criteria) and discussed any occurring differences until a unanimous understanding was reached. The remainder of the articles was screened by the first author of the study, with the second coder double-checking all results, all emerging questions were solved in dialogue until a unanimous decision was reached. In the final sample, 20 articles were included (Figure 1). The articles excluded in this phase either (1) reported the implementation process as related to the outcomes of evidence based SEL programs, (but not contextual factors on implementation variables); (2) focused on: (a) a program that supported teachers’ classroom management skills [but not teaching SE skills to students]; (b) sustaining or measuring quality of program implementation; (c) early childhood SEL program implementation (but had not become evident during title and abstract screening); (d) individual, not classroom- or school-level skill support, like individual behavior intervention; (e) reported a wide array of prevention programs (including tardiness and truancy, substance abuse, risky sexual behavior) and were thus too wide for the SEL scope; (f) reported wider school-wide change, including support systems and school policies, not only SEL support; (g) were theoretical in nature; (h) were addressing teachers’ beliefs of SEL as such, (i) reported relationships only between different quality indicators; (j) one article had been published in a journal listed as predatory (and was, thus, excluded). An overview of the articles included in the sample is presented in Table 1.

Altogether 20 articles remained in the sample after the screening, of which 19 were quantitative, and 1 used a mixed design. The program most frequently studied was the PAX3 version of the Good Behavior Game (GBG, four times), followed by Tier 1 of the school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports (SWPBIS), and LifeSkills Training (reported 3 times); GBG, Promoting Alternative THinking Strategies (PATHS), and Positive Action were reported two times.

Dosage and quality of delivery were operationalized as implementation quality indicators in 13 studies, and adherence in 10 studies (refer to Table 1). Participant responsiveness was operationalized in 4 studies only. In one Dowling and Barry (2020, study 18), the study which used a mixed design, the four quality indicators (adherence, dosage, quality of delivery, and participant responsiveness) were combined into an index after quantitative assessment across implementers; interviews were then carried out and the content of the interviews compared across high and low quality implementers. The authors explained the use of an index score of four kinds of variables as “to measure implementation across multiple dimensions.” The remainder of the 19 articles looked at the relationships with contextual factors and implementation quality indicators separately, and no index score was used. The rationale for using the specific implementation quality indicators was not usually offered, even if several quality indicators were assessed. For example, Mihalic et al. (2008, study 3) operationalized four implementation quality indicators (adherence, dosage, quality of delivery, and participant responsiveness) but did not provide an additional rationale for including all 4, except for referencing them as “primary elements of implementation fidelity.” Ransford et al. (2009, study 4), for example, studied dosage and quality of delivery and referenced them simply as “two common measures of program fidelity.” Johnson et al. (2018, study 14) stood out by explaining their choice of dosage and quality of delivery variables as structurally more relevant to the contextual factor studied (program support: coaching). In general, the provision of an explanation for the choice of implementation quality indicators was fairly uncommon.

3.3. Data analysis

In the first step, a detailed coding manual for the selected articles was created, based on Cooper’s (2017) guidelines, coding was done on six separate coding sheets, which included (1) study characteristics such as purpose and research questions, study type, design, and analytic strategy, program studied, type of SEL program (curriculum or kernel), study setting and year of data collection, (2) participant and sample characteristics, (3) contextual variable name and operationalization, data collection, and measurement, including psychometric properties, (4) implementation quality indicator name and operationalization, data collection, and measurement, including psychometric properties, (5) direct interactions between contextual and implementation quality indicators, and (6) interaction effects between different contextual variables (where provided). In this step, four articles (20%) were coded by two coders and discussed in detail until a unanimous decision was met, thus establishing inter-rater reliability. Data from the remainder of the articles were coded by the first author of the study and afterward carefully double-checked by the second coder.

In the second step, after reviewing all articles, one single post hoc datasheet was formed with (a) the authors’ rationale for including the contextual variables, (b) all contextual variable characteristics, (c) every relationship of the contextual variable with the implementation quality indicator, (d) the authors’ interpretation of the relevance of the results, (e) rationale for further research and (f) descriptions of study limitations. This analysis sheet was compiled by the first author of the study and afterward thoroughly double-checked by the second coder.

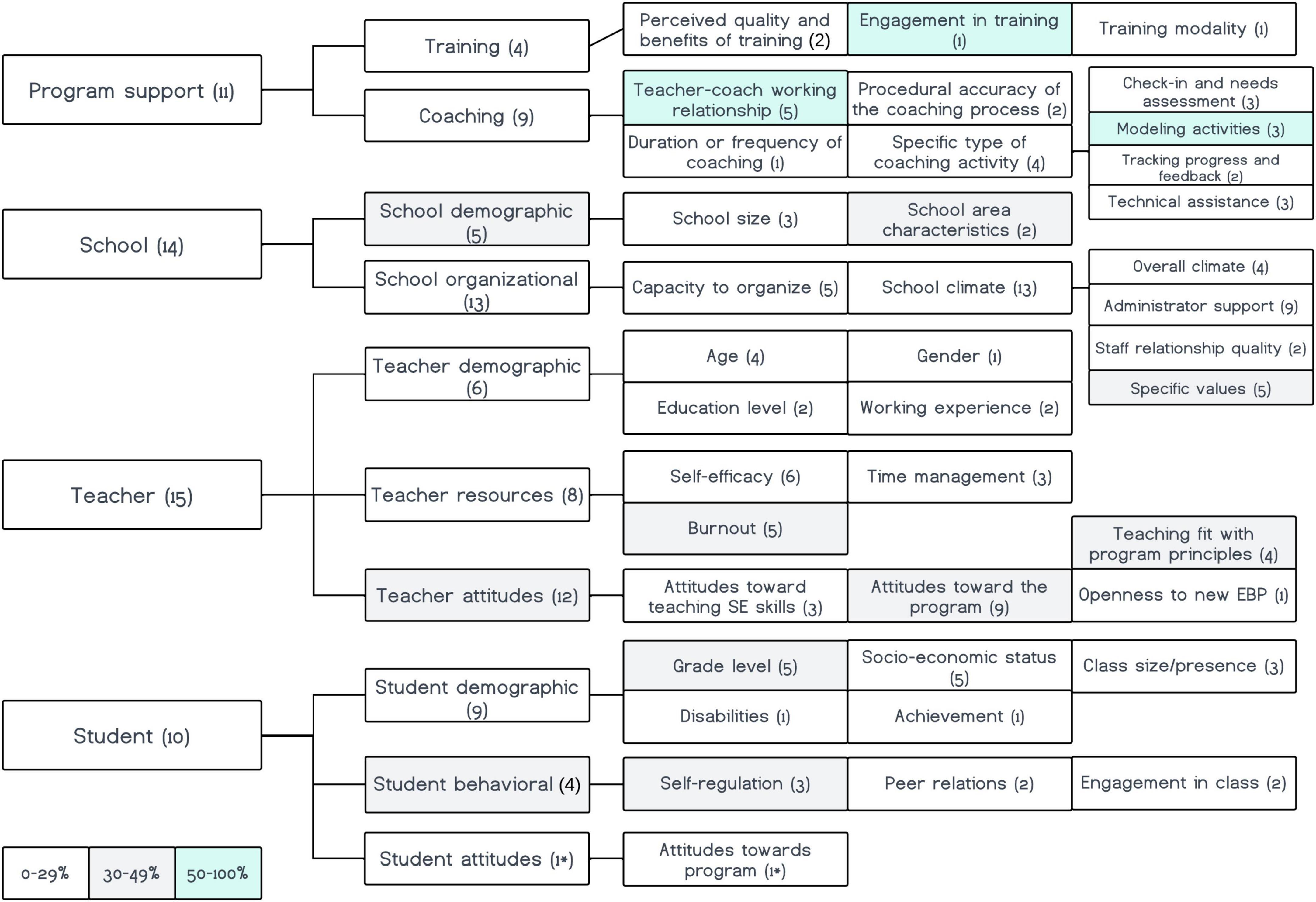

In the third step, the inductive content analysis procedure (Vears and Gillam, 2022) was employed for all the contextual variables to be grouped into categories based on similarity. Four main categories of contextual factors emerged: program support (i.e., training and coaching), school, teacher, and student categories, with 2–3 subcategories for each that further withheld subcategories, based on similarity. The coding result of categories and subcategories can be seen in Figure 2. In one study, one parental support related single item was coded as a contextual variable, but as it did not yield any statistically significant effect on any implementation quality indicator, it was excluded from further analysis. All coded category and subcategory labels were then linked with the contextual variables in the post hoc datasheet. Relations in the mixed methods study were additionally coded if reported as particularly characteristic to the low (n = 12) or high quality implementation group (n = 8). Similarities between the two quality groups in the mixed methods study were not coded, due to their non-differential nature.

Figure 2. Results of the thematic coding process: an overview of school-related contextual factors, four category levels. The figure in brackets indicates the number of articles this factor was explored in. *Category variables only emerged in study 18 (Dowling and Barry, 2020) and are, therefore, not present in Table 2. Color codes indicate the frequency of the statistically significant relationships from tested relationships in the quantitative studies (N = 19).

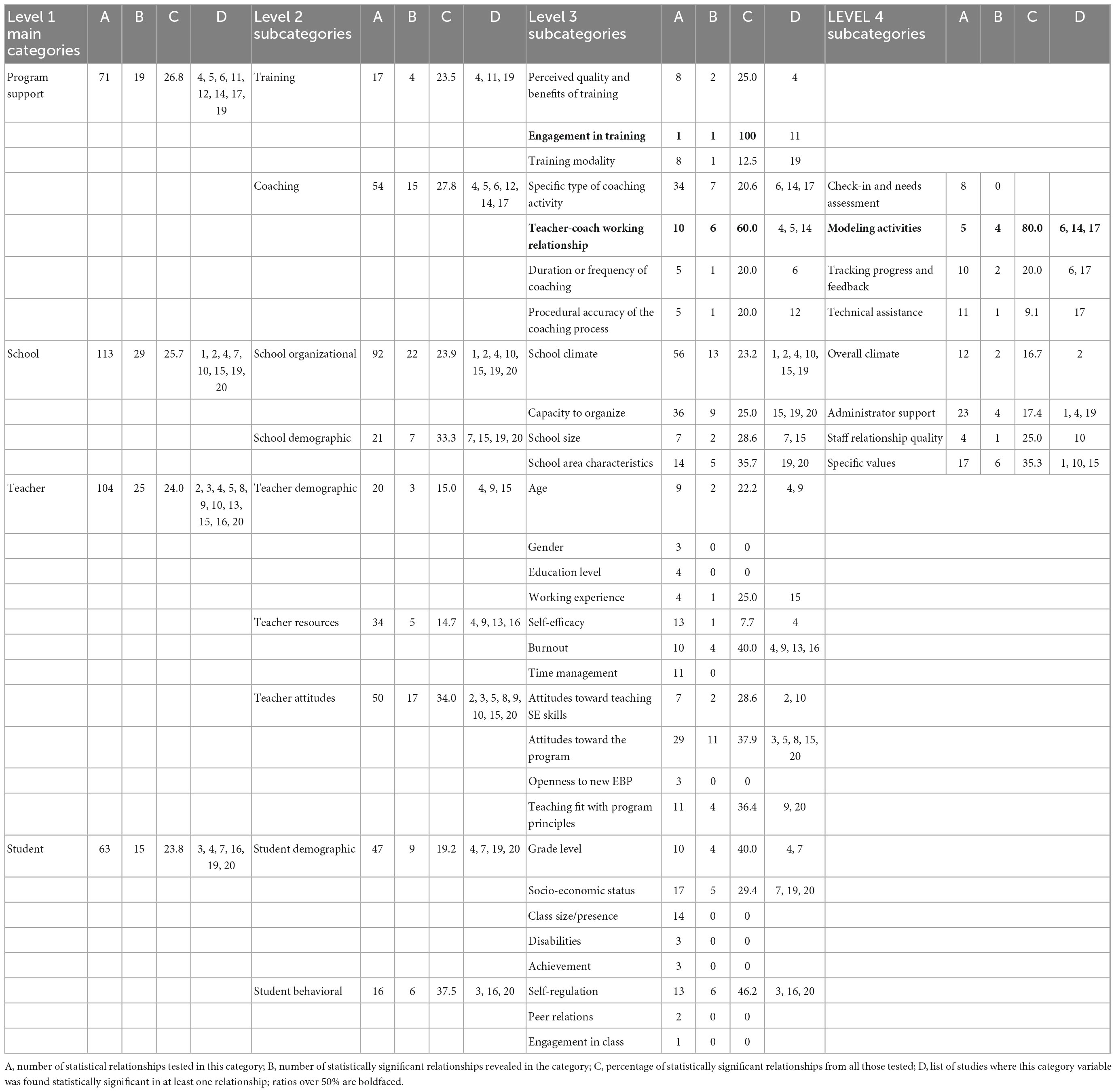

In the fourth step, in order to ascertain, which contextual factors would demonstrate the highest relative frequency of statistical significance toward SEL program implementation quality indicators, a quantitative approach was undertaken. Frequency ratios of statistically significant relationships were calculated across all quantitative articles (n = 19). Altogether 355 relationships were tested in the 19 quantitative articles and around a quarter (83) of these relationships were statistically significant (p < 0.05 or smaller). The largest number of tested relationships was present in the school category (113), followed by the teacher (104), program support (71), and student categories (63) (refer to Table 2). As an illustrating example, in Ransford et al. (2009, study 4), among other contextual variables, two different indicators of teacher resources (self-efficacy and burnout) were both studied for their relationships with dosage and quality of delivery, the latter both measured through two different indicators, which altogether presented 8 relationships tested, of which two turned out to be statistically significant in the study. Studies looked at a different number of relationships, ranging from 1 (study 12) to 51 (studies 9 and 20), and the frequency of statistically significant relations from those tested, ranged from 6 (study 9) to 100% (studies 2, 7, and 12). The results of the relationship significance ratio calculations are presented in Table 2. Relationships with all four outcome variables of implementation quality (adherence, dosage, quality of delivery, and participant responsiveness) were studied in the context of all four categories of contextual factors, no implementation quality indicator appeared more frequently studied across any category of contextual factors.

Table 2. Proportion of statistically significant relationships between contextual factors and implementation quality indicators by category (quantitative articles, N = 19).

4. Results

4.1. Categories of contextual factors

In the process of the thematic coding that was carried out for identifying unifying categories among the contextual variables, four main categories of contextual variables were revealed (refer to Figure 2): program support (i.e., training and coaching), school, teacher, and student category contextual variables. The different categories were present rather equally in articles, teacher category variables were looked at in 15 studies, school variables in 14, and program support variables in 11 articles. Student category factors were considered in the least number of articles (10). Four studies (1, 8, 12, and 14) looked at contextual variables in just one main category (e.g., school), whereas five studies (3, 4, 9, 18, and 19) handled background predictors in all four. The four main categories (level 1) were divided into smaller subcategories into three additional levels, revealing a diverse array of contextual variables tested (follow the subdivision of categories on the four subcategory levels both in Figure 2 and in Table 2).

On level two, teacher-related factors were diversely coded into three subcategories: teacher demographics (six articles), teacher resources (eight articles), and teacher attitudes (12 articles). The demographics subcategory included factors of age (four articles), gender (one article), education level (two articles), and working experience (two articles) on level three. Teacher resources were divided on level three into such psychological resources as (a) self-efficacy (six studies), (b) burnout (five studies), and (c) time management (three articles). Teacher attitudes, in turn, were assessed either toward teaching SE skills (three studies), toward the specific SEL program implemented (nine studies), teaching fit with the program principles (four articles), or openness to employing a new evidence-based practice (EBP, 1 study).

The program support factors were coded into two subcategories on level two: coaching (nine articles) and training (four articles). Training variables on level 3 looked at perceived benefits of training (two articles), teacher engagement during training (one article), and training modality (online vs. face to face, one article). Coaching variables on level three were related to either (a) coach-teacher working relationship (teacher self-report, five articles), (b) the duration or frequency of coaching (one article), (c) the procedural accuracy of coaching as to abide by a certain coaching protocol (two articles), and (d) the specific type of coaching activity applied by the coach (four articles). The specific coaching activities on level four included: a) check-in and needs assessment (three articles), modeling program activities (three articles), tracking progress and feedback (two articles), and technical assistance (three articles).

School factors were coded into two categories on level two: school-organizational (13 articles) and school demographic (five articles), which again were further split into smaller subcategories of thematically grouped variables on level three. In the school demographic factors subcategory, there were two types of variables—school size (number of students, three articles), and school area characteristics, such as rural/suburban or the number of schools engaged in the SEL program implementation in the area (two articles). School organizational factors were coded into two different aspects: school climate indicators (13 articles), and the capacity to organize, which included factors related to providing facilities, materials, or cooperation structures for SEL program implementation in the school (five articles). Within the school climate category, four subcategories were distinguished on level four: (a) general school organizational climate (measured by the overall score of different organizational climate subscales, four articles); or more specific subscales of organizational culture, such as (b) administrative support and/or leadership (nine articles), (c) staff relationship quality (two articles), or (d) the level of particular organizational values such as openness to innovation, support, and respect, perceived collective responsibility, participatory decision-making, or school-wide support for SEL (five studies).

Students were the least frequently studied category and three level 2 subcategories here were student demographic, student behavioral, and student attitudes (the latter was only addressed in one article, Study 18). The demographics subcategory was coded into (a) grade level (five articles), (b) socio-economic status (five articles), (c) class size or presence in class (three articles), (d) percentage of students with disability (one article), and (e) percentage of students proficient in state achievement tests (one article). The student behavioral subcategory was coded into self-regulation (three articles), peer relations (two articles), and engagement in class (two articles).

In response to the first research question, we found that articles most frequently looked at school climate indicators (13 articles), including measures of perceived administrator support (nine articles); teacher attitudes toward the program implemented (nine articles); and teacher self-efficacy (six articles). Overall, a dispersed picture of diverse types of contextual factors emerges from Figure 2, as many kinds of contextual factors only surfaced in one article (such as the duration and frequency of coaching, engagement in training, or openness to new EBP).

4.2. Contextual factors demonstrating the highest frequency of statistical significance

The second research question was interested in which contextual factors would demonstrate the highest frequency of statistically significant relationships with SEL program implementation quality indicators. The relative frequency of statistically significant relationships across all four main categories was somewhat similar, ranging from 23.8% in the student category to 26.8% in the program support category (refer to Table 2). The proportion of statistically significant relationships found, however, varied greatly within the subcategories. Throughout most categories a statistically significant result was present between 0 and 29% of the time (Figure 2), indicating that these types of contextual factors showed more arbitrary statistical significance across several studies.

In 10 categories, the frequency of statistically significant relationships from those tested, ranged between 30 and 49% (marked with gray in Figure 2), indicating a somewhat more consistent tendency for statistical significance across studies. Only three subcategories stood out across studies by displaying a ratio of 50% or higher in the tested vs. statistically significant relationships, all of which emerged from the program support category (marked with light blue in Figure 2). Column D in Table 2 lists studies where a significant relationship was found between that category of contextual factor and an implementation quality indicator; articles that tested, yet failed to find a statistically significant relationship in that category were excluded from Table 2.

Within the program support category, both, training and coaching appear to be significant contextual factors for implementation quality. Training-related contextual variables were not copiously operationalized in the studies. Of special interest was the observer-rated teacher engagement in training, which was the only contextual variable of seven in Wanless et al. (2015, study 11), that yielded any statistical significance toward their single implementation quality indicator of interest (adherence). Coaching-related factors were assessed more frequently. In the specific type of coaching activity category, four different subcategories were distinguished, where only one type of activity was frequently statistically significant toward quality implementation indicators. In all three studies that looked at specific coaching activities’ influence on implementation quality indicators (studies 6, 14, and 17) modeling program-specific activities (i.e., demonstrating how to implement the program practices) was the specific activity that yielded a consistent relationship with implementation quality indicators (statistically significant in 80% of the tested relationships, refer to Table 2). Furthermore, in the mixed methods study, the low-quality implementers’ group was distinctive from the high-quality implementers by suggesting that an external person would deliver the lessons altogether. The teacher-coach working relationship was measured with a single item in study 4 and with a variant of a teacher-coach alliance scale in three studies (5, 9, and 14), all collected as teacher self-report of the working relationship and its benefits with the coach. Throughout articles, this was tested through 10 quantitative relationships in four studies and found statistically significant in six relationships in three articles (p < 0.01), this makes the teacher-coach working relationship the second more consistent variable in the coaching subcategory, as connected to implementation quality indicators. Additionally, in Dowling and Barry (2020, study 18), high quality implementers expressed more openness to implementation support.

Factors in the school category mostly indicated a modest number of statistically significant relationships. School climate was the most common contextual variable category (explored in 13 articles). Despite its popularity, especially by exploring the influence of perceived administrator support on implementation quality (nine studies) the school organizational climate variables, just as demographic variables did not indicate any consistent statistical significance toward implementation quality indicators.

In the teacher category, no types of variables yielded statistically significant relationships across 50% of the tested relationships. Teacher resources were a rather frequent target of inquiry, altogether 34 quantitative relationships were assessed, of which only five were found statistically significant. Teacher self-efficacy indicators, which are often suggested as relevant contextual factors for implementation quality, were statistically significant in only 7.7% of the relationships tested. Teacher burnout (as measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory, Maslach et al., 1996) however, was found to be negatively related to dosage (and not to other implementation quality indicators) in four studies (4, 9, 13, and 16), which sets the relative frequency of statistical significance to 66.7% for relationships tested only between teacher burnout and dosage. This was the only regularity in the current sample where some type of contextual variable would be systematically connected to only one kind of implementation quality indicator.

In the student category, similarly, no types of variables were statistically significant more than 50% of the tested relationships. Student-related factors were primarily assessed as demographic factors (nine articles). Student self-regulation was assessed as a contextual factor for implementation quality in three quantitative articles (studies 3, 16, and 20) and showed the most promise (statistically significant in 46.2% of the tested relationships). More specifically, in Mihalic et al. (2008, study 3) observer-rated quality of student behavior in class predicted adherence and quality of delivery; and in Musci et al. (2019, study 16) observer-rated aggressive behavior in class was negatively related to program dosage. In Combs et al. (2022, study 20) observer-rated student misbehavior negatively predicted all three of their implementation quality indicators (p < 0.001). Additionally, Dowling and Barry (2020, study 18) was the only article in the sample where both teachers and students were included as informants (via interviews) and where student attitudes about the program had a chance to surface, as well as were revealed as distinctive of the quality of program implementation. For example, students in the high implementer group listed more personal benefits of the program, claimed more frequently to have enjoyed the learning experience and could offer more specific examples of SEL benefits to them. Students in the low quality group reported negative program experiences more frequently and could bring less concrete examples of SEL benefits to themselves.

Five articles (studies 2, 4, 5, 11, and 14) viewed the interaction effects of contextual factors on implementation quality indicators. In four of them, interaction effects between variables in different contextual categories were revealed. The type of interaction effect, which was similarly revealed throughout two studies, appeared in the context of perceived burnout and coach-teacher working relationship. Both in Wehby et al. (2012, study 5) and Ransford et al. (2009, study 4), a strong coach—teacher working relationship was seen to reduce the impact of teacher burnout on implementation quality indicators.

5. Discussion

A systematic literature process with a final sample of 20 articles, was carried out to map, what kind of teacher- and school-related contextual factors have been studied in relation to SEL implementation quality indicators; as well as, to see whether any of those contextual factors showed more consistent statistical significance across the articles in the sample.

The current study offers confirmation that different levels of contextual variables are relevant to ensuring implementation quality and further supports an ecological understanding of implementation quality context. Based on the articles in the current sample, four different categories of contextual variables were exposed: student, teacher, school, and program support categories, which, in turn, were divided into quite heterogeneous subcategories into three sublevels (demographic, attitudinal, behavioral, etc., refer to Figure 2 and Table 2), revealing the diversity in contextual factors studied across SEL program implementation quality. It is important to note that all four broader contextual categories also emerged in the mixed methods study (Dowling and Barry, 2020, study 18) where they surfaced through qualitative interviews, not variables operationalized beforehand.

The category of program support factors was the only one in the current study where more consistent statistically significant contextual factors were revealed; and which, based on the current analysis, may thus prove more essential for ensuring the program outcomes for students. The contextual factor with the highest frequency of statistical significance (80%) across articles, was a single kind of coaching activity: modeling program activities to teachers, revealed in studies looking at coaching activities for implementing GBG (Becker et al., 2013, study 6), PAX GBG (Johnson et al., 2018, study 14) and SWPBIS (Bastable et al., 2020, study 17). Modeling has previously been shown as something that supports teacher self-efficacy, especially during the beginning phases of the profession (Bandura, 1977; Johnson, 2010), and can thus be seen as supportive for teachers in adopting new practices. Second, teacher self-report of the working relationship and its benefits with the coach proved more consistently significant (in 60% of the tested relationships in the sample) for ensuring implementation quality for PATHS (Ransford et al., 2009, study 4), GBG (Wehby et al., 2012, study 5), and PAX GBG (Johnson et al., 2018, study 14). It is noteworthy that none of the “procedural” qualities (procedural accuracy of the process, progress feedback, check-in, or time spent coaching) managed this. Study 5 describes the role of the coach as the link between teachers and project staff, offering feedback and assistance and providing program materials; study 15 describes coaching in more collaborative and tailored terms in supporting teachers’ program implementation skill development. Study 4 does not offer a description of the coaching principles applied in implementation. Studies 5 and 14 used a teacher-coach alliance scale (10 and 23 items, respectively), whereas study 4 managed to obtain statistically significant results through the use of a single item. “Overall, how useful was the consultation time with your PATHS coordinator.” Issues of measuring the transactional nature of the coach-teacher working relationship have been discussed in Johnson et al. (2016); study 4, however, indicates, that this contextual factor may also be captured by a single item. The positive impact of coaching on program implementation quality is not a large surprise, as coaching has been shown as an efficient measure for teacher professional development and desired classroom impact (Kraft et al., 2018); the current study, suggests an emphasis on the cooperative or relational aspect of this working alliance, as opposed to its technical aspects. However, as coaching is also costly and the benefits may be short-lived after the program implementation coaching phase had ended (Pas et al., 2022)—the question about longer-term student benefits through quality of teacher implementation practice remains.

A frequently significant relationship between teacher burnout and dosage (and no other implementation quality indicators) was revealed in the current article, suggesting a more systematic pattern between the exhaustion of psychological resources and the amount of program delivered. Additionally, it was shown in studies 4 and 5 that a quality coach-teacher working relationship had the potential to reduce the effects of teacher burnout on program implementation. Research by Ghasemi (2021, 2022) has shown that individual motivational and empowering interventions (similar to coaching) can effectively reduce teachers’ burnout levels. Even though among high-coping teachers, the effects of burnout on everyday practice may not be detrimental, burnout combined with the effects of teacher stress has an evident impact on student outcomes (Herman et al., 2018)—thus coaching in the form of teacher support may also alleviate the risks teacher burnout presents to classroom practice.

The student self-regulation subcategory did not pass the 50% frequency mark in statistical significance (it stayed at 46.2%), but showed potential, as it was statistically significant in all three studies that addressed it. It must be added that In Combs et al. (2021, study 19), a “capacity to organize” indicator4 was measured with a checklist of observer-rated technical and organizational difficulties (e.g., lack of materials, poor facilities), which also included a student disruptive behavior item. This composite factor was predictive of three implementation quality indicators on the teacher level, but the contribution of the observed misbehavior to that effect can only be hypothesized. In their second similar study, Combs et al. (2022, study 20) assessed all observer-rated technical and behavioral difficulty factors as separate contextual variables, and both, capacity to organize and student self-regulation factors were statistically significant contextual predictors in the study (especially, again, on the teacher-, as opposed to the school district level). This might also suggest a hidden effect of observed student self-regulation in study 19. We, thus, suggest that student baseline self-regulation deserves additional attention as a contextual factor in implementation quality research. Musci et al. (2019) pointed out that too few studies had considered the students’ behavioral influences on program implementation by teachers and suggested that there could be a “tipping point” where negative student behavior could present a challenge to implementation. Farmer et al. (2016) have pointed to “correlated constraints” as the network of synergistic associations between individual and social factors in group functioning; which makes specific student contingencies in the classroom and their interaction also an important contextual factor for program implementation, and these should be looked at in further research.

In the current study, some levels of school ecology that have been previously regarded as relevant for ensuring program implementation quality did not prove as consistently significant as might have been anticipated (such as a teacher or school level contextual factors). As an example, the school organizational climate was the most common level 2 background factor category in the current sample (13 articles), assessed with general organization culture measures, as well as more specific assessments of organizational values or administrator support (both generally and to program implementation), that did not yield any consistently significant results. It can be seen that the school (Domitrovich et al., 2008) and organizational capacity (Durlak and DuPre, 2008) levels in previous models also contain a dispersed array of organization-related factors (from organizational norms to ways of decision making) to influence implementation quality. The tradition of including organizational variables can be traced to the ISF which sees different organizational characteristics play an active role in the program implementation process (Wandersman et al., 2008). Despite the undisputed importance of such hygiene factors for school daily life, the current article could not confirm the consistent relevance of those factors for SEL program implementation quality across studies.

On the contrary, the program support category was revealed as a more consistently convincing contextual layer for supporting the quality implementation of SEL programs, in the current study. Even though teachers are frequently referred to as central players in program implementation (e.g., Brackett et al., 2012; Schonert-Reichl, 2017), based on the current study, the quality of program implementation may rely less heavily on teachers’ demographic characteristics, attitudes, or personal resources, and more on something that happens in the “zone” of their professional development. Coaching has a long history of being viewed as an essential part of teacher professional development, that enables the transfer of acquired skills and knowledge into practice (Joyce and Showers, 1981). In Domitrovich et al. (2008) support system is seen as more inherent to the intervention and its implementation process. It may be worth considering treating program support through training and coaching as a separate contextual layer of teacher professional development, designed to induce the desired change in teacher everyday practice.

Furthermore, there is an additional contextual category that has not been suggested explicitly in previous theoretical models and has also been included more infrequently in previous research—the student level. The relative scarcity of studies examining student-level contextual factors could be explained by the tradition of evidence-based programming, where students’ behavior has rather been seen as a result, not the context of program implementation. Students, however, bring baseline behavioral qualities to the interaction that may impact the implementation process. Students’ behavioral factors that are nested in classrooms could also be regarded on the individual level in the school ecology, to interact with the teacher level, who in turn is influenced by the professional development (program support). Tolan et al. (2020) provide support for this idea, as in their integration trial of GBG and My Teaching Partner™ interventions, an effect on student outcomes was observed in the interaction of student behavior, teacher personal resources, and professional development variables.

5.1. Study limitations

There were also several limitations to the study. The first limitation was the relatively small number of articles in the study that remained in the sample after screening. The second limitation is that the current article is affected by both: publication and journal bias. First, only journal articles were considered for the sample, and only Prevention Science and Journal of School Psychology were sampled separately. This could indicate that some relevant information may still have remained unexposed for the sample, also it is possible, that research that concentrates implicitly on the contextual factors’ influence on SEL program implementation is still relatively limited to this day. Third, we see that there is unclarity in SEL program terminology: programs may be called universal prevention programs or classroom management programs in different contexts, which may or may not include teaching and practice of SEL skills. This terminological unclarity may have contributed to the failure to include all relevant articles for the sample. In comparison to an overview of 20 articles, the current study only offers an initial map of the contextual factors and their relevance to implementation quality, several contextual factors were only assessed in just one article and more confirmation would be needed for the relevance of such factors across studies. One such factor was teacher engagement in training that predicted implementation quality. Even though this was a convincing contextual factor in Wanless et al. (2015, study 11), more studies would be needed to confirm the relevance of this factor across studies. The fourth limitation is that it was decided not to carry out any additional quality appraisal of the articles in the sample and that publication in peer-reviewed journals was considered a sufficient benchmark for research quality. It was, however, noticed that many indicators in the frame of the same study may have been assessed with varying degrees of quality (e.g., self-reported single item with low variance, as opposed to observer ratings with high interrater agreement), which could account for the nature of some statistical relationships reported in the sample and should be considered in more detail in further studies. The jingle-jangle fallacy could be seen as one limitation for interpreting the results of this articles, Dane and Schneider (1998) have pointed out that “inconsistencies in the conceptualization of fidelity reduce interpretability of studies.” However, implementation quality indicators have been proposed to be considerably interconnected (Beets et al., 2008; Berkel et al., 2011) and inferences were generally not made, based on the type of implementation variable measured, in the current article.

5.2. Implications of the study

The current article offers an overview, a more organized road map of studies looking into the contextual factors of program implementation which support students’ SE skill development in school, and as such, it presents an original contribution in the context of SEL program implementation research and discussion. The analytical frame of the study has suggested four broad contextual categories to support or hinder quality SEL implementation, as such, contributing to the theoretical development of the field. The results of the current study bolster the relevance of program support factors for implementation quality and reveal a link between teacher burnout and program dosage. Based on the current analysis, student factors emerge as a separate contextual level in school, with special attention to student baseline self-regulation that may influence SEL program implementation quality. Scientists interested in practical research assuring quality contexts or SEL implementation can utilize this knowledge as a navigation tool toward more or less promising avenues for program implementation support.

The current study suggests an emphasis on teacher professional development and support in SEL program implementation, concurring with Cook et al. (2019) emphasis on educator support in the guidelines for effective school-based implementation. Despite many SEL programs providing coaching during initial implementation (e.g., Hershfeldt et al., 2012; Becker et al., 2013), these effects may not be sustained over time (Pas et al., 2022). Longer term coaching initiatives may be considered internally for schools, such as peer coaching or professional learning communities (Timperley et al., 2007; Cook et al., 2019; Elias, 2019). Effective coaching partnerships require teachers to have skills like the reflection of professional practice, which may receive little attention in initial teacher training (Pas et al., 2014) or be learned and practiced in a dubious manner (Marcos et al., 2011). Initial teacher education should, thus, find efficient ways of promoting teacher reflective practice and inquiry mindset (Muijs et al., 2014) so that teachers would already be more equipped with those skills when incorporating new evidence-based practices into their work.

Studying SEL implementation is a tortuous area of study, therefore, such issues as the intricateness of implementation research (Durlak, 2015), the need for theoretical integrity (Jones et al., 2019), or measurement challenges (McKown, 2019) have been previously discussed. Further research is needed that examines both individual and organizational factors on different ecological levels (e.g., teacher, school, and school district), that impact implementation as an outcome (e.g., Domitrovich et al., 2019; Combs et al., 2022). However, research should also address, what accounts for the discrepancies of such findings across different studies and SEL implementation contexts: could they be accounted to the different programs implemented, differing conceptualization and operationalization of implementation quality indicators, or, instead, varying ways of operationalizing or assessing contextual factors. Based on the current study, we would also like to support the further application of mixed methods research on the field, as it may allow for additional contextual factors (such as student attitudes in Dowling and Barry, 2020) to surface, which could have been underrepresented in some previous multi-level models that often guide quantitative research.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

TU was responsible for the systematic literature review process and the analysis and recruiting a second expert as the second rater. KP-V performed the literature review and analysis. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the EEA Financial Mechanism 2014–2021 and Higher Education in Baltic Research Programme (36.1-3.4/289).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Further in this paper referenced simply as “adherence” and “dosage”.

- ^ http://www.ebscohost.com

- ^ The PAX Good Behavior Game (PAX GBG) is a manualized version of the Good Behavior Game (GBG) that applies additional kernels and cues in comparison with the original GBG.

- ^ The only mixed contextual indicator in the sample. This was coded as “capacity to organize” due to the nature of the large majority of items in the observer list.

References

Appleyard, K., Egeland, B., van Dulmen, M. H. M., and Sroufe, L. A. (2005). When more is not better: the role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 46, 235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bastable, E., Massar, M. M., and McIntosh, K. (2020). A Survey of Team Members’ Perceptions of Coaching Activities Related to Tier I SWPBIS Implementation. J. Pos. Beh. Inter. 22, 51–61. doi: 10.1177/1098300719861566

Becker, K. D., Bradshaw, C. P., Domitrovich, C., and Ialongo, N. S. (2013). Coaching Teachers to Improve Implementation of the Good Behavior Game. Adm. Policy Ment Health 40, 482–493. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0482-8

Beets, M. W., Flay, B. R., Vuchinich, S., Acock, A. C., Li, K.-K., and Allred, C. (2008). School Climate and Teachers’ Beliefs and Attitudes Associated with Implementation of the Positive Action Program: a Diffusion of Innovations Model. Prev. Sci. 9, 264–275. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0100-2

Berkel, C., Mauricio, A. M., Schoenefelder, E., and Sandler, I. N. (2011). Putting the Pieces Together: an Integrated Model of program Implementation. Prev. Sci. 12, 23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1

Bethune, K. S. (2017). Effects of Coaching on Teachers’ Implementation of Tier I School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support Strategies. J. Pos. Beh. Inter. 19, 131–142. doi: 10.1177/1098300716680095

Brackett, M. A., Reyes, M. R., Rivers, S. E., Elbertson, N. A., and Salovey, P. (2012). Assessing Teachers’ Beliefs about Social and Emotional Learning. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 30, 219–236. doi: 10.1177/0734282911424879

Burgess, L. G., Riddell, P. M., Fancourt, A., and Murayama, K. (2018). Contagion Within Education: a Motivational Perspective. Mind Brain Educ. 12, 164–174. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12178

Calhoun, B., Williams, J., Greenberg, M., Domitrovich, C., Russell, M. A., and Fishbein, D. H. (2020). Social Emotional Learning Program Boosts Early Social and Behavioral Skills in Low-Income Urban Children. Front. Psychol. 11:561196. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.561196

Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., and Rose, T. (2019). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: how children learn and develop in context. Appl. Dev. Sci. 23, 307–337. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649

Century, J., Rudnick, M., and Freeman, C. (2010). A Framework for Measuring Fidelity of Implementation: a Foundation for Shared Language and Accumulation of Knowledge. Am. J. Eval. 31, 199–218. doi: 10.1177/1098214010366173

Combs, K. M., Buckley, P. R., Lain, M. A., Drewelow, K. M., Urano, G., and Kerns, S. E. U. (2022). Influence of Classroom-Level Factors on Implementation Fidelity During Scale-up of Evidence-Based Interventions. Prev. Sci. 23, 969–981. doi: 10.1007/s11121-022-01375-3

Combs, K. M., Drewelow, K. M., Habesland, M. S., Lain, M. A., and Buddey, P. R. (2021). Does Training Modality Predict Fidelity of an Evidence-based Intervention Delivered in Schools? Prev. Sci. 22, 928–938. doi: 10.1007/s11121-021-01227-6

Cook, C. R., Low, S., Buntain-Ricklefs, J., Whitaker, K., Pullmann, M. D., and Lally, J. (2018). Evaluation of Second Step on Early Elementary Students’ Academic Outcomes: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Sch. Psychol. Q. 33, 561–572. doi: 10.1037/spq0000233

Cook, C. R., Lyon, A. R., Locke, J., Waltz, T., and Powell, B. J. (2019). Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice. Prev. Sci. 20, 914–935.

Cooper, H. (2017). Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. A Step-by-Step Approach Fifth Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications INC. doi: 10.4135/9781071878644

Corcoran, R. P., Cheung, A. C. K., Kim, E., and Xie, C. (2017). Effective universal school-based social and emotional learning programs for improving academic achievement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Educ. Res. Rev. 25, 56–72. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2017.12.001

Dane, A. V., and Schneider, B. H. (1998). Program Integrity in Primary and Early Secondary Prevention: are Implementation Effects out of Control? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 18, 23–45. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00043-3

Domitrovich, C. E., Bradshaw, C. P., Poduska, J. M., Hoagwood, K., Buckley, J. A., Olin, S., et al. (2008). Maximizing the Implementation Quality of Evidence-Based Preventive Interventions in Schools: a Conceptual Framework. Adv. Sch. Ment Health Promot. 1, 6–28. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2008.9715730

Domitrovich, C. E., Pas, E. T., Bradshaw, C. P., Becker, K. D., Keperling, J. P., Embry, D. D., et al. (2015). Individual and School Organizational Factors that Influence Implementation of the PAX Good Behavior Game Intervention. Prev. Sci. 16, 1064–1074. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0557-8

Domitrovich, C. E., Yibing, L., Mathis, E. T., and Greenberg, M. (2019). Individual and organizational factors associated with teacher self-reported implementation of the PATHS curriculum. J. Sch. Psychol. 76, 168–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.07.015

Dowling, K., and Barry, M. M. (2020). Evaluating the Implementation Quality of a Social and Emotional Learning Program: a Mixed Methods Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3249–3265. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093249

Durlak, J. A. (2015). Studying Program Implementation Is Not Easy but It Is Essential. Prev. Sci. 16, 1123–1127. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0606-3

Durlak, J. A. (2016). Programme implementation in social and emotional learning: basic issues and research findings. Cambridge J. Educ. 46, 333–345. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2016.1142504

Durlak, J. A., and DuPre, E. (2008). Implementation Matters: a Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Dusenbury, L., Brannigan, R., Falco, M., and Hansen, W. B. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ. Res. 18, 237–256. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.237

Elias, M. J. (2019). What If the Doors of Every Schoolhouse Opened to Social-Emotional Learning Tomorrow: reflections on How to Feasibly Scale Up High-Quality SEL. Educ. Psychol. 54, 233–245. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1636655

Farmer, T. W., Dawes, M., Alexander, Q., and Brooks, D. S. (2016). “Challenges Associated with Applications and Interventions: correlated Constraints, Shadow of Synchrony, and Teacher/Institutional Factors that Impact Social Change,” in Handbook of Social Influences in School Contexts. Social-Emotional, Motivation, and Cognitive Outcomes, eds K. R. Wentzel and G. B. Ramani (New York, NY: Routledge), 435–449.

Ghasemi, F. (2021). EFL teachers’ burnout and individual psychology: the effect of an empowering program and cognitive restructuring techniques. Curr. Psychol. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01368-5 [Epub ahead of print].

Ghasemi, F. (2022). An Adlerian-Based Empowering Intervention Program with Burned-Out Teachers. J. Educ. 202, 355–364. doi: 10.1177/0022057421998331

Gregory, A., Henry, D. B., and Schoeny, M. E. (2007). School Climate and Implementation of a Preventive Intervention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 40, 250–260. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9142-z

Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J., and Reinke, W. M. (2018). Teacher Stress, Burnout, Self-Efficacy, and Coping and Associated Student Outcomes. J. Pos. Beh. Inter. 20, 90–100. doi: 10.1177/1098300717732066

Hershfeldt, P. A., Pell, K., Sechrest, R., Pas, E. T., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2012). Lessons Learned Coaching Teachers in Behavior Management: the PBISplus Coaching Model. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 22, 280–299. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2012.731293

Humphrey, N., Barlow, A., and Lendrum, A. (2018). Quality Matters: implementation Moderates Student Outcomes in the PATHS Curriculum. Prev. Sci. 19, 197–208. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0802-4

Johnson, D. (2010). Learning to Teach: the Influence of a University-School Partnership Project on Pre- Service Elementary Efficacy for Literacy Instruction Teachers’. Read. Horizon. 50, 23–48.

Johnson, L. A., Wehby, J. H., Symons, F. J., Moore, T. C., Maggin, D. M., and Sutherland, K. S. (2014). An Analysis of Preference Relative to Teacher Implementation of Intervention. J. Spec. Educ. 48, 214–224. doi: 10.1177/0022466913475872

Johnson, S. R., Pas, E. T., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2016). Understanding and Measuring Coach-Teacher Alliance: a Glimpse Inside the Black Box. Prev. Sci. 17, 439–449. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0633-8

Johnson, S. R., Pas, E. T., Bradshaw, C. P., and Ialongo, N. S. (2018). Promoting Teachers’ Implementation of Classroom-Based Prevention Programming Through Coaching: the Mediating Role of the Coach-Teacher Relationship. Adm. Policy Ment Health 54, 404–416. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0832-z

Jones, S. M., and Bouffard, S. M. (2012). Social and emotional learning in schools: from programs to strategies. Soc. Policy Rep. 26, 3–22. doi: 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2012.tb00073.x

Jones, S. M., Brown, J. L., and Aber, J. L. (2011). The longitudinal impact of a universal school-based social-emotional and literacy intervention: an experiment in translational developmental research. Child Dev. 28, 533–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01560.x

Jones, S. M., Brush, K. E., Bailey, R., Brion-Meisels, G., McIntyre, J., Kahn, J., et al. (2017). Navigating SEL from the Inside out: Looking Inside & Across 25 Leading SEL Programs: A Practical Resource For Schools And Ost Providers. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation.

Jones, S. M., McGarrah, W., and Kahn, J. (2019). Social and Emotional Learning: a Principled Science of Human Development in Context. Educ. Psychol. 54, 129–143. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1625776

Joyce, B. R., and Showers, B. (1981). Transfer of Training: the Contribution of “Coaching”. J. Educ. 163, 163–172. doi: 10.1177/002205748116300208

Kam, C.-M., Greenberg, M., and Walls, C. T. (2003). Examining the Role of Implementation Quality in School-Based Prevention Using the PATHS Curriculum. Prev. Sci. 4, 55–63. doi: 10.1023/A:1021786811186

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., and Ladd, G. W. (2016). “Integrating academic and social-emotional learning in classroom interactions” in: handbook of Social Influences,” in School Contexts. Social-Emotional, Motivation, and Cognitive Outcomes, eds K. R. Wentzel and G. B. Ramani (New York, NY: Routledge), 361–378.

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., and Hogan, D. (2018). The Effect of Teacher Coaching on Instruction and Achievement: a Meta-Analysis of the Causal Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 88, 547–588. doi: 10.3102/0034654318759268

Ladd, G. W. (2006). Peer Rejection, Aggressive or Withdrawn Behavior, and Psychological Maladjustment from Ages 5 to 12: an Examination of Four Predictive Models. Child Dev. 77, 822–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00905.x

Malloy, M., Acock, A., DuBois, D. L., Vuchinich, S., Silverthorn, N., Ji, P., et al. (2015). Teachers’ Perceptions of School Organizational Climate as Predictors of Dosage and Quality of Implementation of a Social-Emotional and Character Development Program. Prev. Sci. 16, 1086–1095. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0534-7

Marcos, J. M., Sanchez, E., and Tillema, H. H. (2011). Promoting teacher reflection: what is said to be done. J. Educ. Teach. 37, 21–36. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2011.538269

Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Nagengast, B., Trautwein, U., Morin, A. J. S., Abduljabbar, A. S., et al. (2012). Classroom Climate and Contextual Effects: conceptual and Methodological Issues in the Evaluation of Group-Level Effects. Educ. Psychol. 47, 106–124. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2012.670488

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., and Schwab, R. E. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd Edn. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

McKown, C. (2019). Challenges and Opportunities in the Applied Assessment of Student Social and Emotional Learning. Educ. Psychol. 54, 205–221. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1614446

Mihalic, S. F., Fagan, A. A., and Argamaso, S. (2008). Implementing the LifeSkills drug prevention program: factors related to implementation fidelity. Implement. Sci. 3:5. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-5

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G., and The Prisma Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, 1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Molloy, L. E., Moore, J. E., Trail, J., Van Epps, J. J., and Hopfer, S. (2013). Understanding Real-World Implementation Quality and “Active Ingredients” of PBIS. Prev. Sci. 14, 593–605. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0343-9

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., and Earl, L. (2014). State of the art – teacher effectiveness and professional learning. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 25, 231–256. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2014.885451

Musci, R. J., Pas, E. T., Bettencourt, A. F., Masyn, K. E., Ialongo, N. S., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2019). How do collective student behavior and other classroom contextual factors relate to teachers’ implementation of an evidence-based intervention? A multilevel structural equation model. Dev. Psychopathol. 31, 1827–1835. doi: 10.1017/S095457941900097X

Oberle, E., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Hertzman, C., and Zumbo, B. D. (2014). Social-emotional competences make the grade: predicting academic success in early adolescence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 35, 138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2014.02.004

OECD (2021a). Beyond academic learning: First results from the survey of social and emotional skills. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2021b). Building the future of education. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/education/future-of-education-brochure.pdf

Osher, D., Kidron, Y., Brackett, M., Dymnicki, A., Jones, S., and Weissberg, R. P. (2016). Chapter 17. Advancing the Science and Practices of Social and Emotional Learning: looking Back and Moving Forward. Rev. Educ. Res. 40, 644–681. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16673595

Pas, E. T., Bradshaw, C. P., and Cash, A. H. (2014). “Coaching Classroom-Based Preventive Interventions,” in Handbook of School Mental Health. Research, Training, Practice and Policy, eds M. D. Weist, N. A. Lever, C. P. Bradshaw, and J. S. Owens (New York, NY: Springer), 255–268. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7624-5_19

Pas, E. T., Kaihoi, C. A., Debnam, K. J., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2022). Is it more effective or efficient to coach teachers in pairs or individually? A comparison of teacher and student outcomes and coaching costs. J. Sch. Psychol. 92, 346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2022.03.004

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., et al. (2011). Outcomes for Implementation Research: conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm. Policy Ment Health 38, 65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

Rabiner, D. L., Godwin, J., and Dodge, K. A. (2016). Predicting Academic Achievement and Attainment: the Contribution of Early Academic Skills, Attention Difficulties, and Social Competence. Sch. Psych. Rev. 45, 250–267. doi: 10.17105/SPR45-2.250-267

Ransford, C. R., Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Small, M., and Jacobson, L. (2009). The Role of Teachers’ Psychological Experiences and Perceptions of Curriculum Supports on the Implementation of a Social and Emotional Learning Curriculum. Sch. Psych. Rev. 38, 510–532.

Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and Emotional Learning and Teachers. Future Child 27, 137–155. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0007

Streimann, K., Selart, A., and Trummal, A. (2020). Effectiveness of a Universal, Classroom-Based Preventive Intervention (PAX GBG) in Estonia: a Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Prev. Sci. 21, 234–244. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-01050-0

Suntheimer, N. M., and Wolf, S. (2020). Cumulative risk, teacher-child closeness, executive function and early academic skills in kindergarten children. J. Sch. Psychol. 78, 23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.005

Swift, L. E., Hubbard, J. A., Bookhout, M. K., Grassetti, S. N., Smith, M. A., and Morrow, M. T. (2017). Teacher factors contributing to dosage of the KiVa anti-bullying program. J. Sch. Psychol. 65, 102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.07.005

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., and Fung, I. (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development. Bet Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. New Zealand: Iterative Best Evidence Synthesis Programme.

Tolan, P., Molloy Elreda, L., Bradshaw, C. P., Downer, J. T., and Ialongo, N. (2020). Randomized trial testing the integration of the Good Behavior Game and My Teaching Partner™: the moderating role of distress among new teachers on student outcomes. J. Sch. Psychol. 78, 75–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.12.002