- 1Migration Health Division, International Organization for Migration, Amman, Jordan

- 2Faculty of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Occupational Medicine, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

- 3School of Health and Related Research, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom

- 4School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, Institute of Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- 5Krefting Research Center, Institute of Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- 6Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Biotechnology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria

- 7Department of Community Health Nursing, Princess Muna College of Nursing, Mutah University, Amman, Jordan

- 8Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Department of Community Health, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

- 9Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Taiz University, Taiz, Yemen

- 10School of Health and Environmental Studies, Hamdan Bin Mohammed Smart University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- 11Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan

- 12Faculty of Medicine, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

- 13International Medical Corps, Amman, Jordan

- 14Department of Computer Science, King Abdullah II School for Information Technology, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

The current study aimed at exploring university students’ perspectives on the emergency distance education strategy that was implemented during the COVID-19 crisis in Jordan, one of the countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Utilizing a qualitative design supported by Moore’s theory of transactional distance, a total of 17 semi-structured interviews were conducted with university students of various study levels and disciplines. Data were inductively analyzed using thematic analysis as suggested by Braun and Clarke. Seven themes have emerged, including, (i) students’ psychological response to the sudden transition in educational process, (ii) students’ digital preparedness, equality, and digital communication, (iii) students’ and teachers’ technical competencies and technostress, (iv) student–student and student–teacher interpersonal communication, (v) quality and quantity of learning materials, (vi) students’ assignments, examinations, and non-reliable evaluation methods, and (vii) opportunities with positive impact of distance learning. The study findings provide evidence that the sudden transition from traditional on-campus to online distance education was significantly challenging in many aspects and was not a pleasant experience for many participants. Various factors under the jurisdiction of academic institutions and decision-makers are considered main contributing factors to the students’ educational experiences amid the pandemic crisis. Therefore, better planning and more sustainable utilization of educational resources have paramount importance in providing a high-quality education. Additionally, more dedicated efforts in terms of equitable, reliable, and credible evaluation systems should be considered in Jordan’s distance education strategy.

Introduction

It has been over two years since the greatest global disruption of education due to the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) crisis. Most campuses of various educational institutes were closed and switched to online distance education mode, starting a new era in educational history (Barakat et al., 2022; Ellakany et al., 2022; Mohammed et al., 2022). Developed countries were more prepared for the unprecedented transition in many terms, such as quality of internet services, technical competencies of instructors, and the experience in online education during the pre-pandemic era. On the other hand, developing countries were less prepared and faced more challenges in implementing the new teaching model due to unreliable technical infrastructure and financial costs (El Said, 2021; Barakat et al., 2022).

Many studies tried to capture the perspective of students and instructors toward the online experience aiming to improve the learning deliverables and increase the outcomes through comparing distance online education versus face-to-face education in developed countries (El Said, 2021). While the entire world switched to online distance education during the pandemic crisis, few studies tried to capture the impact of this switch on students and teachers in developing nations. The studies mainly focused on the students’ attitude toward online learning, especially for students with practical courses. Students’ feedback and experience were mixed between positive and negative. Many students commented on the instructors’ ability to provide online lessons and use technology to provide the best educational outcome (Hussein et al., 2020; Khalil et al., 2020). Many teachers have limited technological skills resulting in difficulties in providing virtual aids to present the lectures; thus, affecting the teaching quality. Also, some students expressed that they are on-campus learners and online lessons are not a fit for them (Al-Balas et al., 2020; Hussein et al., 2020; Khalil et al., 2020; Suliman et al., 2021). When it was related to practical courses, such as in engineering, medicine, and nursing, many students reported dissatisfaction as they believed they lost the chance to learn essential skills for their future careers (Sindiani et al., 2020; Ibrahim et al., 2021; Suliman et al., 2021).

Additionally, many studies in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) highlighted a worsening in the psychological wellbeing of students due to lockdown, study load, and concerns about the future and career, which resulted in lower energy and higher distraction while attending virtual courses (Al-Tammemi et al., 2020; Hussein et al., 2020; Alsoud and Harasis, 2021; Fawaz and Samaha, 2021; Suliman et al., 2021). Moreover, many students experienced more homework and assignments than in face-to-face education, assuming that students have more time to study due to the lockdown resulting in fewer achievements and more anxiety (Hussein et al., 2020). The level of satisfaction toward distance online education was found to be related to having previous experience in online learning. In contrast, students without former experience may need some time to adapt to the new learning model (Sindiani et al., 2020). Considering the pandemic crisis, students may perceive that online education is safer than the traditional face-to-face one; however, this can be particularly applicable to pandemic or conflict scenarios, and not for ordinary life (Hussein et al., 2020).

Even with the global race in digitalization and distance education within the past decades, many developing countries of limited resources seem struggling to keep up with the global pace. Arab countries were not an exception to be severely afflicted by the pandemic and its consequences on education, health, economy, and social life (Al Nsour et al., 2020; Akour et al., 2021a; Khatatbeh et al., 2021b; Undp., 2021; El Abiddine et al., 2022). In light of the previously described challenges and considering that most studies about online distance education in the Arab region were of a quantitative nature, the present study aimed at exploring the university students’ perspectives on the emergency remote education that started in response to the COVID-19 crisis using a qualitative approach to gain an in-depth understanding of the lived experiences amongst students.

Materials and methods

Study setting and population

Our study was conducted in Jordan, one of the Arab countries located in the WHO EMR with a total population of 11.2 million (Department of Statistics., 2020). Jordan is classified as a middle-income country according to the World Bank. The official spoken language in the country is Arabic. The study population comprised students who were officially enrolled in a study program at any of the public or private universities in the academic year 2019/2020 or 2020/2021 (the academic year usually starts in September and ends in June with some minor variations between public and private universities in the country). The implementation of emergency distance education in Jordan has started in the middle of March 2020.

Study design and theoretical framework

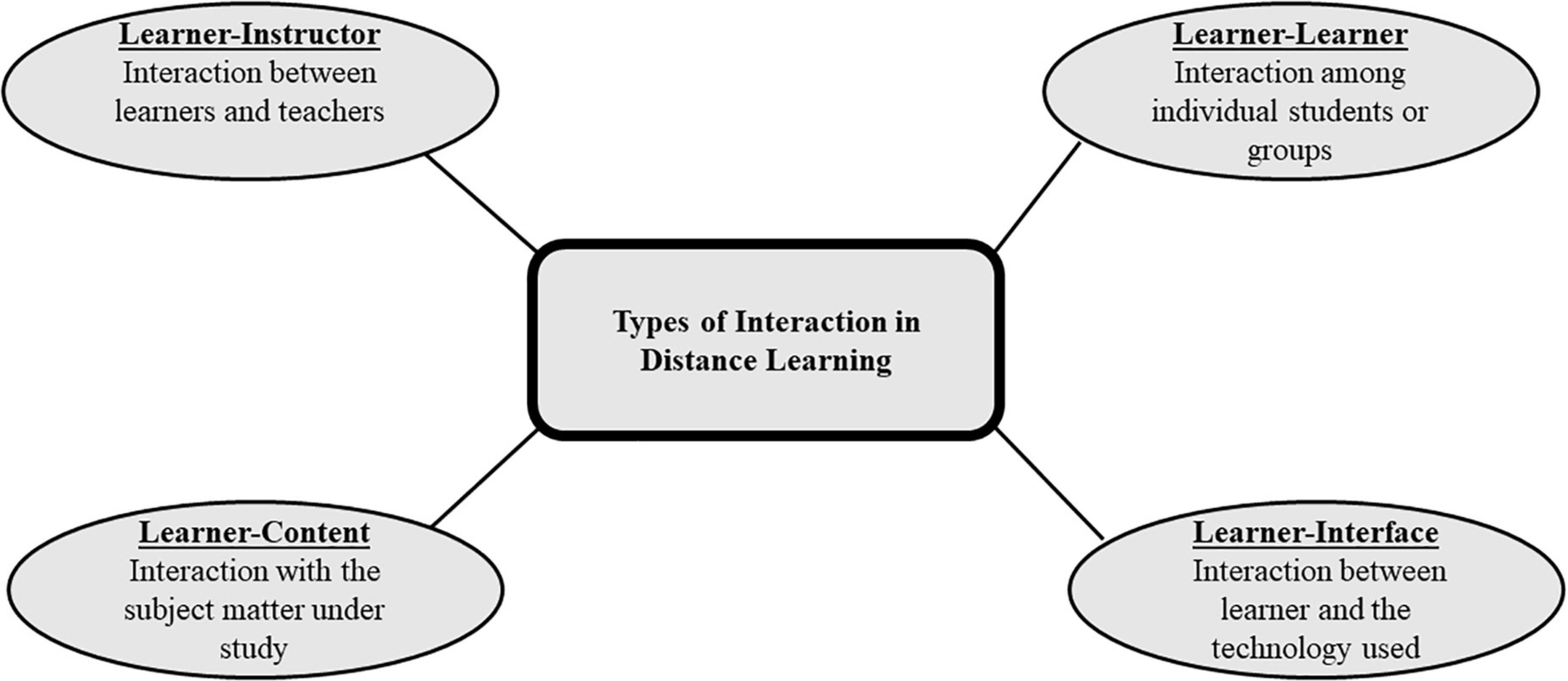

An exploratory qualitative design with a framework based on Moore’s theory of transactional distance was employed in the current study. Utilizing a qualitative approach was agreed on to get an in-depth understanding of the university students’ lived experiences and opinions during the unprecedented transition from traditional on-campus education to distance education during the nationwide lockdown in Jordan. Additionally, the authors adopted the theory of transactional distance as a theoretical model to facilitate a more systematic exploration of the students’ experiences. This theory was originated in the 1970s by Moore (2018). Transactional distance is defined as “the physical distance that leads to a communications gap, a psychological space of potential misunderstandings between the behaviors of instructors and those of the learners” (Moore and Kearsley, 1996; Chen, 2001). In 1989, Moore pointed to three domains of interactions that present in distance learning, including learner-instructor interaction, learner-learner interaction, and learner-content interaction (Moore, 1989). Later in the 1990s, Hillman, Wills, and Gunawardena had taken Moore’s theory into a more advanced step by adding a fourth domain of interaction that is, learner-interface interaction, considering the interaction that occurs between students and technology in the telecommunication era (Chen, 2001). Accordingly, we adopted the four domains for a more systematic approach in addressing our study objectives. Figure 1 illustrates more details about the four domains of the above-mentioned interactions.

Figure 1. The four types of interactions that occur in distance learning. Moore’s theory of transactional distance was adopted as a framework in our qualitative approach.

Sampling

Students were purposively recruited with maximum variation sampling to capture a diverse and wide spectrum of views and lived experiences relating to online distance education. A web-based advertisement that described the nature and objectives of the study along with eligibility criteria was disseminated to student groups on Facebook ®. University students in Jordan created these groups as a tool for general and academic communication. Students aged 18 years and above, and who experienced the COVID-19 enforced distance education from various Jordanian universities, study programs, and study levels were encouraged to enroll in the study. Students who declared their interest to participate were asked to fill out a brief online questionnaire that collected basic sociodemographic data (age, gender, residence region, and contact details) and educational profile (public or private university, study program, and study level). Additionally, the online questionnaire included a written informed consent regarding voluntary participation, interviews recording, and consent to publish quotes.

Data collection: semi-structured interviews

A total of 17 semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with students in the period of September–December 2020. To facilitate data collection, an interview guide which was created by the authors based on the four constructs of Moore’s theory of transactional distance was utilized (Supplementary Appendix 1). The interview guide was further inspired by the students’ reactions and comments on various social media platforms during the implementation of distance learning.

Given the unfolding situation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated control measures, to limit physical contact with students due to the pandemic, and to eliminate any geographical boundaries aiming to reach participants from different Jordanian governorates, the interviews were conducted using voice over internet protocol (VoIP) via Zoom ® videoconferencing platform.

The interviews were conducted at a suitable time that was determined by each student based on the student’s availability and daily schedule. All interviews were conducted in Arabic (the national language of Jordan), and verbal consent was obtained from all students at the beginning of each interview as a pre-requisite for starting the recording process (along with the written consent provided in the online questionnaire).

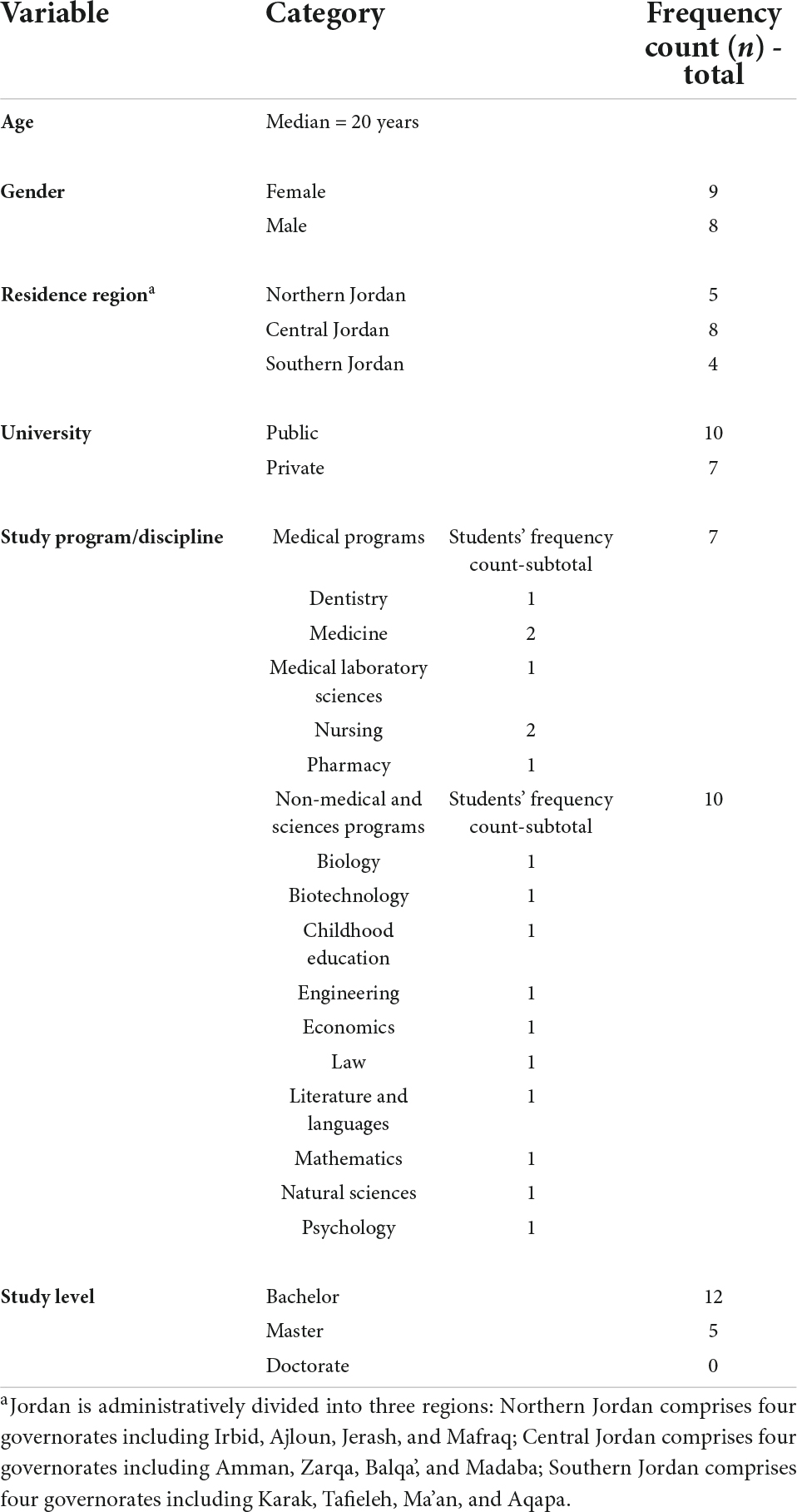

Various probing techniques were employed to encourage the students to explicitly express their opinions, stories, and experiences. The researchers closed the interview by asking the students whether they wanted to add any further information. The average duration of an interview was around 38 min, and the sampling process continued until data saturation was achieved. No incentives or rewards were provided upon participation. Students who agreed to participate in the study came from various educational backgrounds and study programs including both medical programs (i.e., Medicine, Pharmacy, Dentistry, Medical Laboratory Sciences, Nursing), which involve both theoretical and practical sessions, as well as non-medical programs related to arts and humanities, engineering, and sciences (i.e., Law, Literature and Languages, Engineering, Natural Sciences, Childhood Education, Mathematics, Biology, Biotechnology, Psychology, Economics). Many of the non-medical programs have also theoretical and practical sessions (e.g., Biology, Biotechnology, Engineering, Natural sciences). Additionally, during the pandemic crisis and the transition to distance education at the time of conducting the current study, all the courses were delivered virtually as synchronous and/or non-synchronous sessions, due to the complete closure of all higher education campuses in the country. The characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Data management and analysis

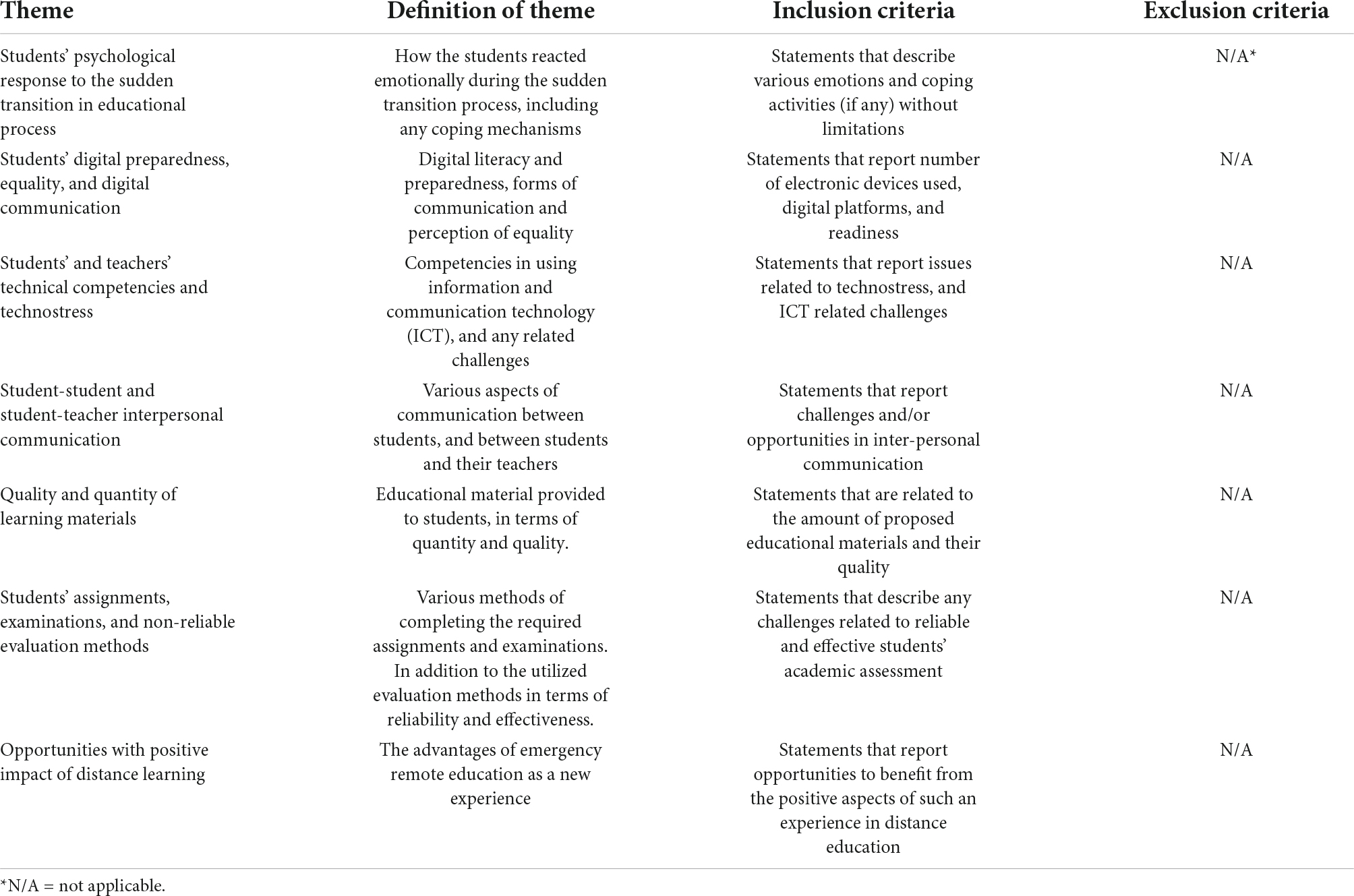

The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim (in Arabic) by three researchers who have prior experience in qualitative research. Then, transcripts were analyzed inductively using thematic analysis as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006). This involved familiarization with the transcribed data, assigning preliminary codes, merging codes into themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and lastly reporting themes. Data coding and analysis were conducted by the same researchers who conducted the interviews. Discrepancies in coding were discussed by the team and resolved by reaching a consensus. For reporting purposes, selected quotes were translated into English by two bilingual translators using translation and back-translation technique. Moreover, we adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). Table 2 describes the coding scheme of the implemented analysis.

Study rigor and trustworthiness

Despite that replicability is not a characteristic of qualitative research, unlike in the quantitative one, various techniques have been discussed in the literature to enhance the trustworthiness of qualitative research findings and methodology (Lincoln et al., 1985). Accordingly, and for ensuring the rigor and trustworthiness of the present qualitative study, Lincoln and Guba (1985) criteria were adopted, and this involves credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability. Peer-debriefing, using quotations, prolonged engagement with participants as well as the explicit statement about confidentiality, all were utilized to establish credibility. Also, peer-debriefing between researchers who conducted and analyzed the interviews was used to enhance dependability, and confirmability. Additionally, enhancing transferability was sought through the detailed description of the study context and participants, justifying the sampling strategy as well as describing data collection procedure and analysis.

Ethical considerations

The ethical approval for conducting our study was obtained from the institutional review board of the Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Jordan with a reference number (IRB# 310/2020/19). Also, all study procedures were conducted conforming to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The recorded interviews as well as the transcripts were encrypted with a password and kept securely. Moreover, written, and verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants regarding voluntary participation, recording the interviews, and consent to publish quotes.

Results

Seven themes have emerged from the transcribed data of the 17 interviews as the following:

Theme one: Students’ psychological response to the sudden transition in educational process

Students during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis were put in a new educational experience during the enforcement of emergency online education and the closure of higher academic institutions in Jordan. This unprecedented transition in the educational system has forced most students to have various emotional responses. When students were asked to recall how they felt when receiving the news about the implementation of online distance education, they described various feelings. Their feelings were attributed to many reasons as well.

A pharmacy student said:

“I just felt happy when I knew that the university will be closed, and all our classes will be delivered virtually…I no longer need to spend more time and money on public transportation. I will have more time to study too”

Also, another student who studies at the faculty of language studies expressed being happy due to shifting to online education. The student perceived this as a precautionary measure against COVID-19 and unnecessary interpersonal interactions:

“It was great news when I heard that I will not attend on-campus classes because this will reduce face to face communication; thus, avoiding the exposure to the coronavirus”

However, an engineering student expressed mixed feelings when receiving the news about closing universities:

“…I had a mixed feeling surrounded by fear, anxiety, and some sort of happiness at the same time…I felt that I will be going through an uncertain academic journey”

On the contrary, a group of students expressed more negative feelings toward the emergency transition in the educational process. This was mostly attributed to the affection of the usual learning process, especially regarding practical sessions. A student who studies nursing said:

“An unexpected situation…I was supposed to attend the hospital for my practical training…I felt anxious at that time…”

Additionally, a student who attends a medical laboratory sciences program stated:

“I thought it was good news at the beginning, but with time and all of a sudden, I realized I was not well prepared for the transition”

Moreover, a student who attends medical school said:

“It was shocking to hear that! I did not know what will happen to my practical sessions in the hospital. I am about to graduate, and this is a very critical period in my academic journey… I am very stressed”

Theme two: Students’ digital preparedness, equality, and digital communication

The transition to distance education was an unprecedented decision. Students have to prepare and equip themselves with digital equipment to meet the requirements of attending their virtual classes. However, this was not easy for many of them. A student who studies psychology said:

“I bought a new headset and camera to facilitate the communication and learning experience during my virtual classes…”

Also, another student from the faculty of sciences expressed difficulty in preparation for distance education:

“Our family has three students at university, and we have only one laptop. You cannot imagine how it feels when we have an overlapping lecture schedule! Using smartphones for virtual classes is not always friendly. this is not suitable”

Having digital equipment, and other required accessories for online education was a challenge for students who suffer from financial constraints. A student who studies economics said:

“I used to have my laptop, tablet, and smartphone. same as my other siblings in the family…However, many students cannot afford to have all or some of these…governmental support to vulnerable students was not sufficient…This is unfair”

Moreover, students were forced to rely solely on digital communication during distance education, and this has forced them to experience an increase in their usage level of virtual platforms. A medical student expressed the following:

“I started to be more committed to using my electronic devices during distance education. checking various learning platforms, my email, and many academic groups on social media to be able of managing the required studying duties and assignments…”

Theme three: Students’ and teachers’ technical competencies and technostress

As the process of transition to distance education was unplanned and enforced due to the pandemic situation, many challenges were expected to be faced. One of these challenges was related to technical aspects. The students have used various online platforms such as Microsoft Teams ®, Zoom ®, and Moodle ® to attend their virtual classes, submit assignments, and set for examinations. Most participants expressed that these online utilities were friendly and easy to use, while other students pointed to various challenges. Some of which were the lack of high-quality internet services in certain geographical areas, some platforms need sufficient digital skills to be used, non-sufficient technological competencies of many teachers, and non-sufficient digital resources/machines (e.g., laptop, desktop, etc.), especially when having many members who attend online distance education in the same family.

A biology student said:

“I regularly use the online platforms provided by my university. these platforms are easy to use considering having a sufficient level of digital literacy”

Also, another student from the faculty of dentistry added the following:

“I am very comfortable with using online platforms, I can mute my microphone and turnoff my camera when no necessary interaction is needed”

On the other hand, many students expressed that they experienced unfriendly situations when the internet suddenly disconnects, and this might have severe impacts, especially during online exams. A student who attends an early childhood education program said:

“This is not right. How could I maintain smooth progress in my learning while being stressed about internet connectivity issues! I heard about a student who failed the exam due to a sudden interruption in the internet connection…”

Moreover, a mathematics student expressed difficulty in attending virtual classes. This was partially attributed to the level of digital skills of some teachers:

“Some virtual platforms have a non-friendly user interface that needs high digital skills…Also, some teachers do not know how to use these platforms…they need some training to improve their technical competencies…”

Also, many students have faced difficulties in attending their classes due to the heavy burden on the internet services in the country. An engineering student said:

“Imagine when hundreds of thousands of students from various universities in Jordan attend virtual classes at the same time during midday… a huge load on the internet service providers and the losing side is us, the students”

Theme four: Student-student and student-teacher interpersonal communication

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a paradigm shift concerning interpersonal communication in the entire world. Due to various confinement and control measures, people including students were forced to maintain physical distancing and to limit face-to-face social interaction. University students were not an exception. Students have used virtual platforms to interact with their peers and teachers during the closure of universities in Jordan. However, this was not a smooth transition, and many students reported interpersonal communication challenges. A medical student said:

“Oh my God, communicating with teachers is becoming more difficult. I feel lost due to being enrolled in many virtual groups for various classes…On-campus classes are more suitable”

Additionally, another student from the biotechnology program has expressed the following:

“…Some teachers responded very late to my emails, while in the university campus I was going to the teacher during office hours for most of my inquiries…”

Some students have also described major impacts on communication with their colleagues. A psychology student said:

“I experienced a better communication with people during on-campus education…at the university, I have more engagement with my colleagues and teachers. Now in distance education…not enough activities or socialization…this is boring…”

Most of the interviewed students referred to a problem related to misuse of learning platforms by some students. A student who attends an engineering program shared the following:

“…This is not funny at all! While the transition to distance education is a critical stage amidst the pandemic, some students perceive virtual classes as a place for fun and jokes…Some students were intentionally too noisy with their unmuted microphones…students should take distance education more seriously”

On the contrary, some students have more positive experiences with virtual communication. A nursing student said:

“…I believe that some teachers have provided some sort of support regarding distance education. They tried to make student-teacher communication easier. They created groups on social media platforms to communicate with us regarding our study materials”

Theme five: Quality and quantity of learning materials

In this theme, students have disclosed various opinions regarding the quality and quantity of the educational materials provided to them during remote online education. A medical student said:

“Sometimes I felt overwhelmed with the number of educational materials provided. The professors try to increase the lectures load in terms of content, believing that students have more time to study during the lockdown…this was different compared to what I experienced in the university campus”

Also, an engineering student has had trouble in remote experimental sessions:

“The presentations and study materials were somehow not sufficient especially for my practical sessions”

Additionally, another student in medical laboratory sciences said:

“Most lectures were provided as a PowerPoint presentation or PDF with good visualization. However, some study materials were more advanced than what is supposed to be received during on-campus education…I do not understand the reason behind this”

On the contrary, some students felt that the study materials provided during remote online education were sufficient. An English literature student said:

“In my opinion and experience, I feel that the quantity and quality of the study materials provided to me were the same as during on-campus education…this is good enough to me”

Theme six: Students’ assignments, examinations, and non-reliable evaluation methods

In this theme, most of the interviewed students described the evaluation methods and examinations in distance education to be non-reliable. A law student said:

“Cheating is a remark of distance education in our country…students can cheat in all remotely conducted exams as there is no reliable method to monitor students’ activities during distance examinations”

Another student from the faculty of medicine said:

“Students are calling each other to solve online exams…how is this supposed to be a quality education?!”

As cheating in online exams was described as a remark of online distance education in Jordan, some students experienced a high degree of difficulties in other evaluation methods such as assignments. An engineering student said:

“Too many lectures and assignments. I must submit many assignments every week…teachers have realized that many students cheat during remotely conducted online exams, thus, they tried to push the students to prepare more assignments as a better and more reliable evaluation method. I believe this is not working well too”

Additionally, a nursing student said:

“Students are getting high end-semester grades during online distance education compared to on-campus education and examinations. This warns of a severe deficiency in the credibility and reliability of distance examination methods…a big failure in the monitoring system too”

Theme seven: Opportunities with positive impact of distance learning

Despite the tough transition to online distance education, many students have seen various opportunities that positively impacted their academic journey. A medical student said:

“I feel that I have a better engagement with my studies. Now, I have more time to study than that when I had to go to the university campus”

Another student from the faculty of language studies described online education as a flexible learning opportunity:

“Learning during online distance education is more comfortable…even timing of lectures is flexible too”

Moreover, it seems that the transition to online education has enhanced the learning skills and abilities of some students. A student from the faculty of sciences said:

“Online education has enhanced my searching skills including using scientific websites in preparing my assignments…I feel that this experience has improved my self-learning skills and abilities”

Furthermore, a law student expressed the following:

“During online distance education, I feel more comfortable as I can dress more comfortably compared to university dressing. Also, I realize that my facial skin is becoming healthier as I am currently avoiding hot weather during my supposed on-campus summer classes…no more on-campus attendance during summer…this is perfect for me”

Discussion

The COVID-19 has overwhelmed many countries due to its high contagiousness and rapid spread as well as the control measures that most countries were forced to implement to mitigate or retard the spread of this disease (Al-Tammemi, 2020; Wendelboe et al., 2020). This global pandemic has not only resulted in biological or psychological harm, but also in dramatic changes that severely afflicted many sectors and industries globally, including healthcare provision, economy, social life, travel, and education (Al-Tammemi, 2020; Akour et al., 2021a,b; Aljaberi et al., 2021; Alrawashdeh et al., 2021; Fares et al., 2021; Folayan et al., 2021a,b; Garbóczy et al., 2021; Khatatbeh et al., 2021a,c; Ramadan et al., 2021).

According to the United Nations (UN), the COVID-19 pandemic has created the most prominent global disruption in education. Nearly, 1.6 billion learners in more than 190 countries have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The closures of educational institutes have affected around 94% of the world’s student population with more visible impacts in low- and middle-income countries (United Nations., 2020). Jordan was amongst the first countries in the Arab region to implement strict confinement measures in all sectors to control the spread of COVID-19 in the country (Al-Tammemi, 2020; Khatatbeh, 2020, 2021; Al-Tammemi et al., 2021). In the middle of March 2020, all universities were closed as a part of the pandemic response strategy in Jordan. Although there was no preparedness plan for the unprecedented transition to online distance education, the Jordanian government has invested extensive efforts through various ministries to make this emergency academic transition effective and efficient.

Nevertheless, the higher education system in Jordan has an unpleasant history regarding online distance education, and even the equivalency process for many external distance/online degrees was and still is a significant challenge (Akour et al., 2020). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the distance education strategy was not one of the priorities of the Jordanian higher education sector with around 25% or less of university courses were delivered remotely. Therefore, the abrupt transition from traditional face-to-face education to distance education in the Jordanian higher education institutions has created a new challenge for the students as well as the teachers. Our study found that the university students in Jordan have faced many impactful experiences while transiting from on-campus education to online distance one. Many of these experiences have negatively impacted the students similar to what was reported in prior quantitative studies in the country (Akour et al., 2020; Al-Balas et al., 2020; Al-Tammemi et al., 2020). Additionally, the literature shows more negative feedback within developing countries and the Arab region. The sudden switch to online distance education highlighted that this part of the world is not yet ready for this switch.

The overall aim of the current study was to get in-depth view about the lived experiences of university students in Jordan during the emergency academic transition to online learning amid the pandemic crisis. Presenting the voices and feelings of the students using their own words is expected to have a major impact on tackling the strengths and weaknesses of the implemented online education strategy in the country. Consequently, tackling various factors that impacted the students’ lived experiences has paramount importance to enhance the current education strategy, by implementing improvements and creating opportunities for a more quality education.

As many students in our study stressed the points related to digital preparedness, equity, and technical challenges, their lived experiences were found to be consistent with what has been reported in previous studies. Some studies provided an insight into the additional inequalities introduced by the online education system. Most of the reported disadvantages included the financial ability to purchase the needed equipment, such as laptops or desktop computers, high-speed internet, or other tools (Al-Balas et al., 2020; Alsoud and Harasis, 2021; Ibrahim et al., 2021). Moreover, the ability to afford a separate and quiet place to study and attend lectures is related to many factors, such as the number of members in the household, home size, and socio-economic status; thus, providing rich students with more privilege (Alsoud and Harasis, 2021; Ibrahim et al., 2021). The former factors also introduce rural-urban inequality as rural areas tend to be more crowded, with smaller houses and with lower access to the needed equipment and technological infrastructures (Alsoud and Harasis, 2021; Ibrahim et al., 2021).

The current study has many strengths which are shaped in the following facts (i) Implementing a qualitative approach which helped to gain a comprehensive understanding of the students’ lived experiences and opinions, (ii) using a previously published theoretical model to support the framework of our qualitative approach, (iii) employing a maximum variation sampling to capture diversity in the students’ opinions, (iv) using various techniques as suggested by Lincoln and Guba (1985); Nowell et al. (2017) to ensure the trustworthiness of qualitative approach, and lastly (v) following the COREQ.

Nevertheless, some limitations need to be acknowledged, including that the interview data represent self-reported states, thus, recall bias should be considered, and participants’ body language could not be fully observed due to using a videoconferencing platform to conduct the interviews. Additionally, taking into consideration the nature of qualitative research, the results cannot be generalized to all students/target population, and due to conducting this research in a stressful period amidst the COVID-19 crisis, the students’ answer might have been influenced by the psychological and socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic. Moreover, the small sample size – despite reaching data saturation, is considered one of the limitations in the current study. Lastly, as the study was advertised on social media, this may have resulted in missing the voices of students who were not regularly active on such platforms; thus, missing the advertisement.

The ongoing evolution in educational technology is significantly impacting learning resources, learning processes, and the academic performance and achievement of students (López-Belmonte et al., 2021). Taking into consideration the findings of the current study, many implications and recommendations can be drawn to support effective and efficient transition from traditional on-campus learning to distance or even hybrid learning technology. Some of which are: establishing clear policy and strategies to enhance a smooth implementation of distance learning in Jordanian universities, maintaining equality and quality education, targeting the weakness points provided by the students (e.g., poor internet connection, insufficient practical sessions/materials, etc.) with more realistic solutions based on piloted projects in distance learning, effective engagement of faculty staff in various trainings related to improvement of their technological competences. Additionally, decision-makers of the education sector in Jordan are advised to consider the psychological and socioeconomic factors of students in future policies and decisions regarding university education during a crisis or an emergency event. More dedicated efforts in terms of fair, reliable, and credible evaluation and monitoring systems should be also considered in such policies.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed a significant burden on university students in Jordan. The sudden transition to online distance education was challenging for most participants in our study. Although the degree of resilience and coping in crisis is inherently different between students, various entities under the jurisdiction of academic institutions and decision-makers are considered main contributing factors to the students’ lived experiences amid the pandemic crisis. The battle against COVID-19 has been already exhaustive in terms of efforts and resources, therefore, better planning and more sustainable utilization of educational resources have paramount importance in contexts with limited resources.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Jordan with a reference number (IRB# 310/2020/19). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AA-T and HF: conceptualization and methodology. AA-T: supervision and writing—original draft preparation. AA-T, MK, and MB: data collection and data analysis. RN, CJ, DA, HA-M, MA, and HF: literature review. AA-T, RN, CJ, DA, MA, MK, MB, HA-M, and HF: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to provide their extreme thanks and appreciation to all study participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.960660/full#supplementary-material

References

Al-Balas, M., Al-Balas, H. I., Jaber, H. M., Obeidat, K., Al-Balas, H., Aborajooh, E. A., et al. (2020). Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 20:341. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02257-4

Al-Tammemi, A. B. (2020). The Battle Against COVID-19 in Jordan?: An Early Overview of the Jordanian Experience. Front Public Heal. 8:188. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00188

Al-Tammemi, A. B., Akour, A., and Alfalah, L. (2020). Is It Just About Physical Health? An Online Cross-Sectional Study Exploring the Psychological Distress Among University Students in Jordan in the Midst of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 11:562213. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562213

Al-Tammemi, A. B., Tarhini, Z., and Akour, A. (2021). A swaying between successive pandemic waves and pandemic fatigue: Where does Jordan stand? Ann Med Surg. 65, 102298. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102298

Al Nsour, M., Bashier, H., Al Serouri, A., Malik, E., Khader, Y., Saeed, K., et al. (2020). The Role of the Global Health Development/Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Network and the Eastern Mediterranean Field Epidemiology Training Programs in Preparedness for COVID-19. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 6, e18503. doi: 10.2196/18503

Aljaberi, M. A., Alareqe, N. A., Qasem, M. A., Alsalahi, A., Noman, S., Al-Tammemi, A., et al. (2021). Rasch Modeling and Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Usability of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) During the COVID-19 Pandemic. SSRN Prepr.

Akour, A., Al-Tammemi, A. B., Barakat, M., Kanj, R., Fakhouri, H. N., Malkawi, A., et al. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Emergency Distance Teaching on the Psychological Status of University Teachers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Jordan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 103, 2391–2399. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0877

Akour, A., AlMuhaissen, S. A., Nusair, M. B., Al-Tammemi, A. B., Mahmoud, N. N., Jalouqa, S., et al. (2021a). The untold story of the COVID-19 pandemic: perceptions and views towards social stigma and bullying in the shadow of COVID-19 illness in Jordan. SN Soc Sci. 1, 240. doi: 10.1007/s43545-021-00252-0

Akour, A., Elayeh, E., Tubeileh, R., Hammad, A., Ya’Acoub, R., and Al-Tammemi, A. B. (2021b). Role of community pharmacists in medication management during COVID-19 lockdown. Pathog Glob Health. 115, 168–177. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2021.1884806

Alrawashdeh, H. M., Al-Tammemi, A. B., Alzawahreh, M. K., Al-Tamimi, A., Elkholy, M., Al Sarireh, F., et al. (2021). Occupational Burnout and Job Satisfaction Among Physicians in Times of COVID-19 Crisis: A Convergent Parallel Mixed-Method Study. BMC Public Health. 21:811. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10897-4

Alsoud, A. R., and Harasis, A. A. (2021). The impact of covid-19 pandemic on student’s e-learning experience in Jordan. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res. 16, 1404–1414. doi: 10.3390/jtaer16050079

Barakat, M., Farha, R. A., Muflih, S., Al-Tammemi, A. B., Othman, B., Allozi, Y., et al. (2022). The era of E-learning from the perspectives of Jordanian medical students: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 8, e09928. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09928

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Qualitative Research in Psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.993405

Chen, Y.-J. (2001). Dimensions of transactional distance in the world wide web learning environment: a factor analysis. Br J Educ Technol. 32, 459–470. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00213

Department of Statistics. (2020). Jordan. Population Count. Available online at: http://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/ (accessed September 9, 2022).

El Abiddine, F. Z., Aljaberi, M. A., Gadelrab, H. F., Lin, C. Y., and Muhammed, A. (2022). Mediated effects of insomnia in the association between problematic social media use and subjective well-being among university students during COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Epidemiol. 100030. doi: 10.1016/j.sleepe.2022.100030

El Said, G. R. (2021). How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Higher Education Learning Experience? An Empirical Investigation of Learners’ Academic Performance at a University in a Developing Country. Adv Human-Computer Interact 2021, 6649524. doi: 10.1155/2021/6649524

Ellakany, P., Zuñiga, R. A. A., El Tantawi, M., Brown, B., Aly, N. M., Ezechi, O., et al. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student’ sleep patterns, sexual activity, screen use, and food intake: A global survey. PLoS One. 17:e0262617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262617

Fares, Z. E. A., Al-Tammemi, A. B., Gadelrab, H. F., Lin, C.-Y., Aljaberi, M. A., Alhuwailah, A., et al. (2021). Arabic COVID-19 Psychological Distress Scale: development and initial validation. BMJ Open. 11, e046006. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046006

Fawaz, M., and Samaha, A. (2021). E-learning: Depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology among Lebanese university students during COVID-19 quarantine. Nurs Forum. 56, 52–57. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12521

Folayan, M. O., Ibigbami, O., Brown, B., El Tantawi, M., Uzochukwu, B., Ezechi, O. C., et al. (2021a). Differences in COVID-19 Preventive Behavior and Food Insecurity by HIV Status in Nigeria. AIDS Behav. *vP. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03433-3

Folayan, M. O., Ibigbami, O., El Tantawi, M., Brown, B., Aly, N. M., Ezechi, O., et al. (2021b). Factors Associated with Financial Security, Food Security and Quality of Daily Lives of Residents in Nigeria during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 7925. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157925

Garbóczy, S., Szemán-Nagy, A., Ahmad, M. S., Harsányi, S., Ocsenás, D., Rekenyi, V., et al. (2021). Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 9:53. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00560-3

Hussein, E., Daoud, S., Alrabaiah, H., and Badawi, R. (2020). Exploring undergraduate students’ attitudes towards emergency online learning during COVID-19: A case from the UAE. Child Youth Serv Rev. 119, 105699. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105699

Ibrahim, A. F., Attia, A. S., Bataineh, A. M., and Ali, H. H. (2021). Evaluation of the online teaching of architectural design and basic design courses case study: College of Architecture at JUST, Jordan. Ain Shams Eng J. 12, 2345–2353. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2020.10.006

Khalil, R., Mansour, A. E., Fadda, W. A., Almisnid, K., Aldamegh, M., Al-Nafeesah, A., et al. (2020). The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 20:285. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z

Khatatbeh, M. (2020). Efficacy of Nationwide Curfew to Encounter Spread of COVID-19: A Case From Jordan. Frontiers in Public Health 8:394. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00394

Khatatbeh, M. (2021). The Battle Against COVID-19 in Jordan: From Extreme Victory to Extreme Burden. Front Public Heal. 8:634022. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.634022

Khatatbeh, M., Al-Maqableh, H. O., Albalas, S., Al Ajlouni, S., A’aqoulah, A., Khatatbeh, H., et al. (2021b). Attitudes and Commitment Towards Precautionary Measures Against COVID-19 amongst the Jordanian Population: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Survey. Front Public Heal. 9:745149. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.745149

Khatatbeh, M., Alhalaiqa, F., Khasawneh, A., Al-Tammemi, A. B., Khatatbeh, H., Alhassoun, S., et al. (2021a). The Experiences of Nurses and Physicians Caring for COVID-19 Patients: Findings from an Exploratory Phenomenological Study in a High Case-Load Country. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 9002. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179002

Khatatbeh, M., Khasawneh, A., Hussein, H., Altahat, O., and Alhalaiqa, F. (2021c). Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Among the General Population in Jordan. Front Psychiatry. 12:618993. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.618993

Lincoln, Y. S., Guba, E. G., and Pilotta, J. J. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Int J Intercult Relations. 9, 438–439.

López-Belmonte, J., Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J., Pozo-Sánchez, S., and Marín-Marín, J.-A. (2021). Co-word analysis and academic performance from the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology in Web of Science. Australas J Educ Technol 37, 119–140. doi: 10.14742/ajet.6940

Mohammed, L. A., Aljaberi, M. A., Amidi, A., Abdulsalam, R., Lin, C.-Y., Hamat, R. A., et al. (2022). Exploring factors affecting graduate students’ satisfaction toward e-learning in the era of the COVID-19 crisis. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 12, 1121–1142. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe12080079

Moore, M. G. (2018). “The Theory of Transactional Distance,” in Handbook of Distance Education, (Milton Park: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315296135-4

Moore, M. G., and Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance Education: A Systems View of Online Learning. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int J Qual Methods 16, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

Ramadan, M., Hasan, Z., Saleh, T., Jaradat, M., Al-hazaimeh, M., Bani Hani, O., et al. (2021). Beyond knowledge: Evaluating the practices and precautionary measures towards COVID-19 amongst medical doctors in Jordan. Int J Clin Pract. 75, e14122. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14122

Sindiani, A. M., Obeidat, N., Alshdaifat, E., Elsalem, L., Alwani, M. M., Rawashdeh, H., et al. (2020). Distance education during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study among medical students in North of Jordan. Ann Med Surg. 59, 186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.09.036

Suliman, W. A., Abu-Moghli, F. A., Khalaf, I., Zumot, A. F., and Nabolsi, M. (2021). Experiences of nursing students under the unprecedented abrupt online learning format forced by the national curfew due to COVID-19: A qualitative research study. Nurse Educ Today. 100, 104829. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104829

Undp. (2021). Arab countries respond to COVID-19: Heightening Preparedness Integrated Multi-sectoral Responses Planning for Rapid Recovery. Available online at: https://www.arabstates.undp.org/content/rbas/en/home/coronavirus.html (accessed on October 3, 2021).

United Nations. (2020). Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. Available online at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf (accessed on July 10, 2021).

Keywords: digital preparedness, Jordan, COVID-19, qualitative, distance education, Moore’s theory, transactional distance

Citation: Al-Tammemi AB, Nheili R, Jibuaku CH, Al Tamimi D, Aljaberi MA, Khatatbeh M, Barakat M, Al-Maqableh HO and Fakhouri HN (2022) A qualitative exploration of university students’ perspectives on distance education in Jordan: An application of Moore’s theory of transactional distance. Front. Educ. 7:960660. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.960660

Received: 03 June 2022; Accepted: 02 September 2022;

Published: 26 September 2022.

Edited by:

Carmen Llorente Cejudo, University of Seville, SpainReviewed by:

Antonio José Moreno Guerrero, University of Granada, SpainAsmaa Sharif, Tanta University, Egypt

Copyright © 2022 Al-Tammemi, Nheili, Jibuaku, Al Tamimi, Aljaberi, Khatatbeh, Barakat, Al-Maqableh and Fakhouri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ala’a B. Al-Tammemi, ZHIuYWxhYXRhbWltaUB5YWhvby5jb20=; orcid/0000-0003-0862-0186

Ala’a B. Al-Tammemi

Ala’a B. Al-Tammemi Rana Nheili

Rana Nheili Chiamaka H. Jibuaku4,5,6

Chiamaka H. Jibuaku4,5,6 Musheer A. Aljaberi

Musheer A. Aljaberi Moawiah Khatatbeh

Moawiah Khatatbeh Muna Barakat

Muna Barakat Hussam N. Fakhouri

Hussam N. Fakhouri